Submitted:

23 January 2024

Posted:

24 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The deep network for hyperspectral anomaly detection lacks a clear learning direction and merely relies on assumption of high reconstruction errors to identify anomalies which fails to meet the requirements of diverse hyperspectral anomaly detection scenarios. It is urgent for us to develop a method that gives interpretation for the learning approach of hyperspectral anomaly detection deep network and provides guidance for its training phase.

- (2)

- The current state-of-the-art methods of hyperspectral anomaly detection primarily relies on spectral reconstruction with pixel-level for deep learning-based methods, which inappropriately comes to terms with the spatial structure of HSI and interferes the deep network's ability to learn any spatial features. In the reality, spatial information plays a crucial role in hyperspectral anomaly detection. The lack of spatial structure analysis brings limitations for the detection performance of certain existing approaches.

- (3)

- The background of HSI is inherently multivariate and complex. However, most traditional and deep learning-based methods still assume multivariate normal distribution for the hyperspectral background. This assumption does not always hold true for real-world complex background of HSI which causes existing algorithms inadequate for adapting to such scenes. Then, applications of these hyperspectral anomaly detection methods are mostly limited to simple scenarios.

- (1)

- A novel fully convolutional auto-encoder is proposed to make full use of spatial information to assist hyperspectral anomaly detection task to achieve joint anomaly detection process with spatial structure.

- (2)

- A novel module for extracting prior knowledge which combines the DBSCAN and connected component analysis clustering is designed to guide deep network learning by extracting background and anomaly samples. This ensures that the proposed deep network has a clear learning direction. Additionally, the induction of triplet loss helps separating the distance between background and anomaly. Hence, it enhances the separability between background and anomaly.

- (3)

- To overcome the limitations of assuming specific distribution for the background and achieve more accurate reconstruction for the pure background, we propose a latent feature adversarial consistency network. This network aims to learn the true distribution of the real background and employs an adversarial consistency enhancement loss to strengthen the constraints for reconstructing a purer background.

2. Proposed Method

2.1. Overview

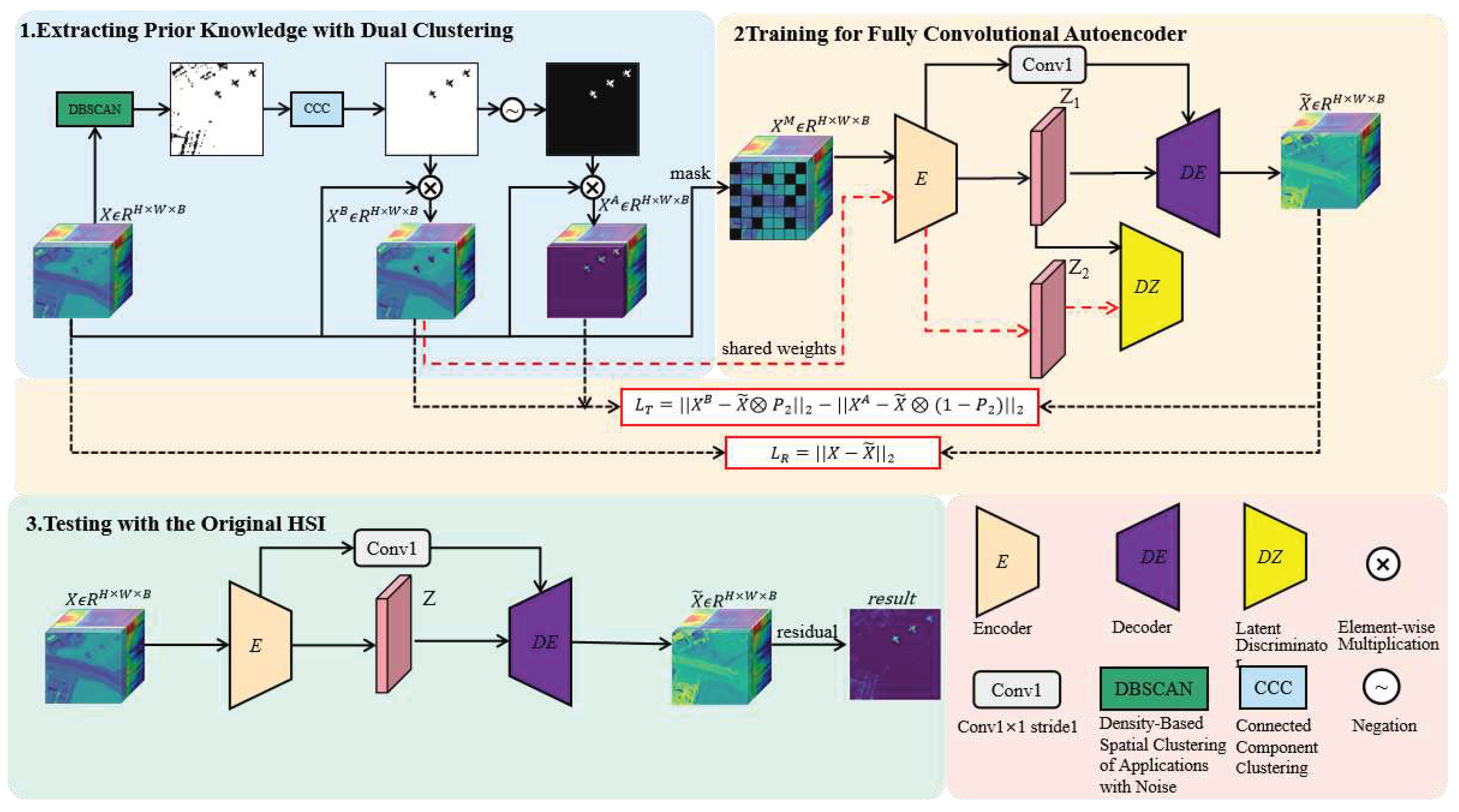

- (1)

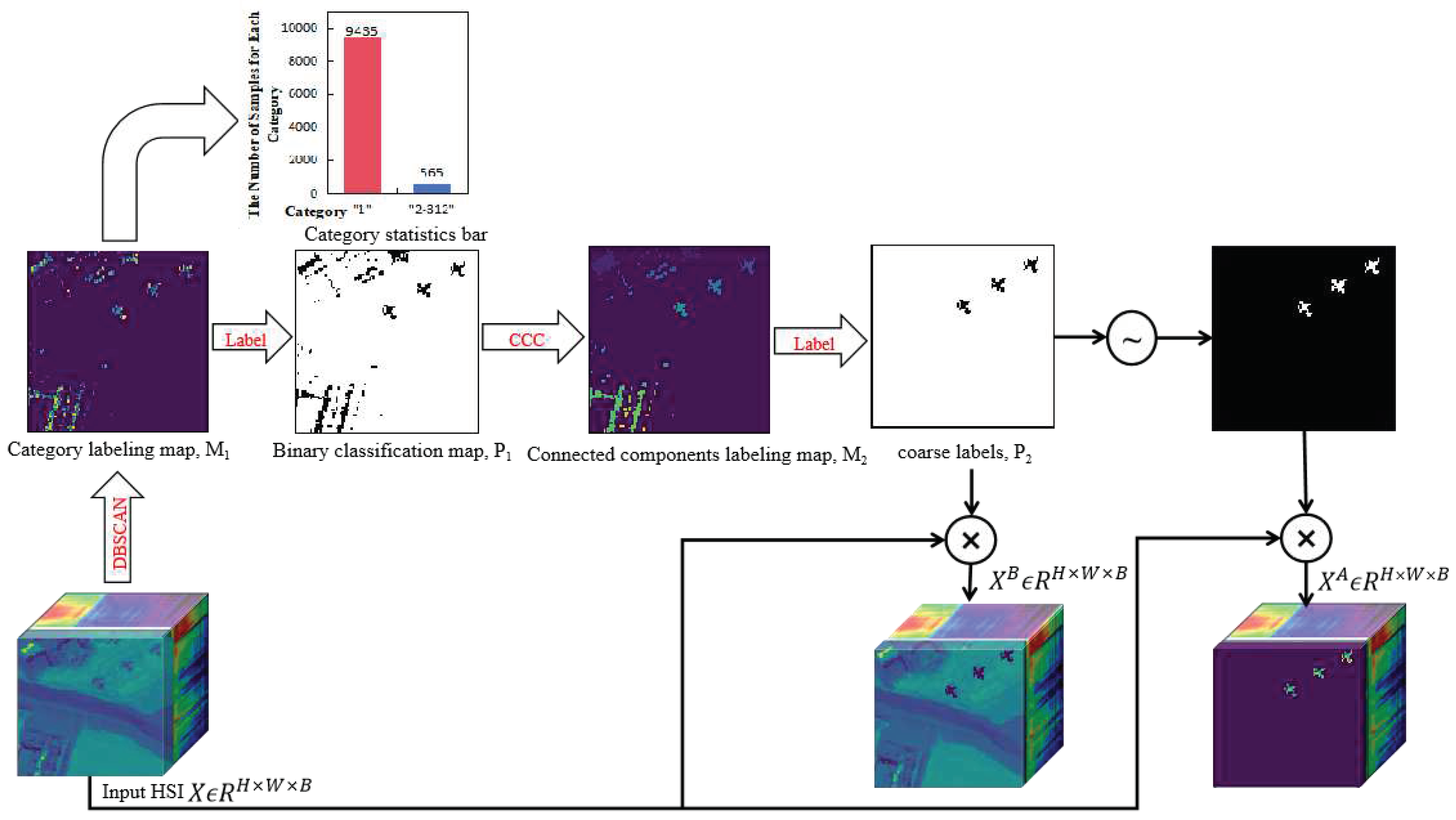

- Extracting Prior Knowledge with Dual Clustering: the purpose of Dual Clustering is to obtain coarse labels for supervised network learning and provide the network with a clear learning direction to enhance its performance. Dual clustering (i.e. unsupervised DBSCAN and connected domain analysis clustering) techniques are employed to cluster the HSI from spectral domain to spatial domain which yields preliminary separation results between background and anomaly regions. Subsequently, prior samples representing background and anomaly regions are obtained through this processing which effectively purifies the supervision information provided to the deep network by conveying more background-related information as well as anomaly-related information. These anomaly features are then utilized to suppress anomaly generation while the background features contribute towards reconstructing most of the background.

- (2)

- Training for Fully Convolutional Auto-Encoder: the prior background and anomaly samples extracted in the first stage are used as training data for fully convolutional auto-encoder model training. During the training phase, the original hyperspectral information is inputted into a fully convolutional deep network using a mask strategy while an adversarial consistency network is employed to learn the true background distribution and suppress anomaly generation. Finally, with leveraging self-supervision learning as a foundation, the whole deep network is guided to learn by incorporating the triplet loss and adversarial consistency loss. Additionally, spatial and spectral joint attention mechanism is brought in both the encoder and decoder stages to enable adaptive learning for spatial and spectral focus.

- (3)

- Testing with the Original Hyperspectral Imagery: the parameters of the proposed deep network are fixed, and the original hyperspectral imagery is fed into the trained network for reconstructing the expected background for hyperspectral imagery. At this stage, the deep network only consists of an encoder and a decoder. The reconstruction error serves as the final detection result of the proposed hyperspectral anomaly detection method.

2.2. Extracting Prior Knowledge with Dual Clustering

2.3. Training for Fully Convolutional Auto-Encoder

2.3.1. Data Augmentation

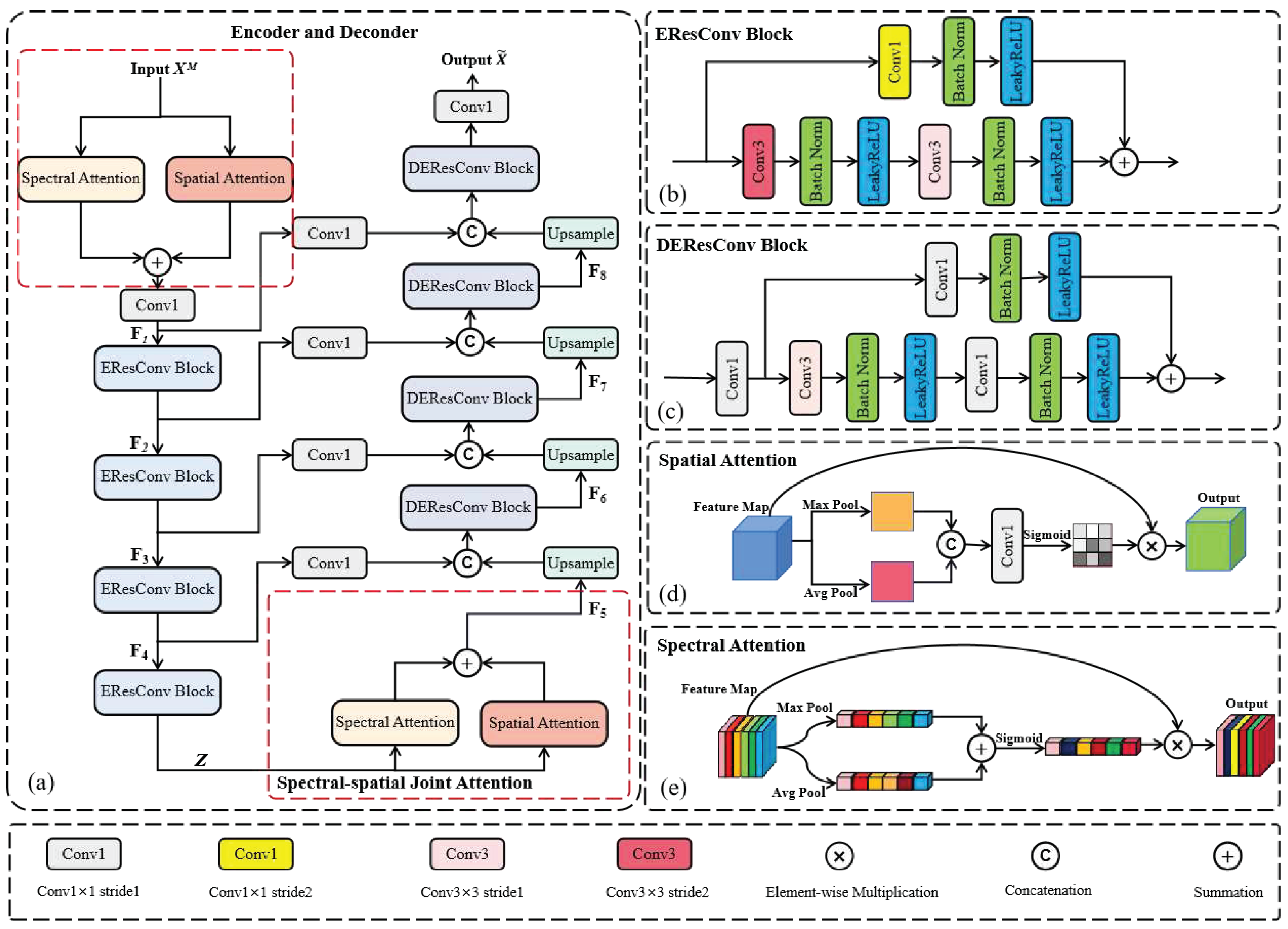

2.3.2. Network Architecture

- (1)

- Fully Convolutional Auto-Encoder (FCAE): previous deep learning-based hyperspectral anomaly detection methods, such as GAED [40], employ fully connected layers for pixel-wise self-supervised learning of HSI on the spectral dimension. However, these methods result in the degradation of spatial structure within HSI which leads to a significant loss of spatial information and underutilization of the spatial characteristics of original HSI. Additionally, dealing with input hyperspectral image with pixel by pixel mode prevents the deep network from capturing spectral correlations between adjacent pixels which results in isolated features and limited information acquisition. A straightforward improvement can be observed in Auto-AD [43], in which convolutional auto-encoder (CAE) are utilized for self-supervised learning of the HSI cube. By incorporating convolution operations, pooling operations, and sampling operations into AE architecture, CAE not only extracts spatial features effectively but also enhances spectral feature correlation.

- (2)

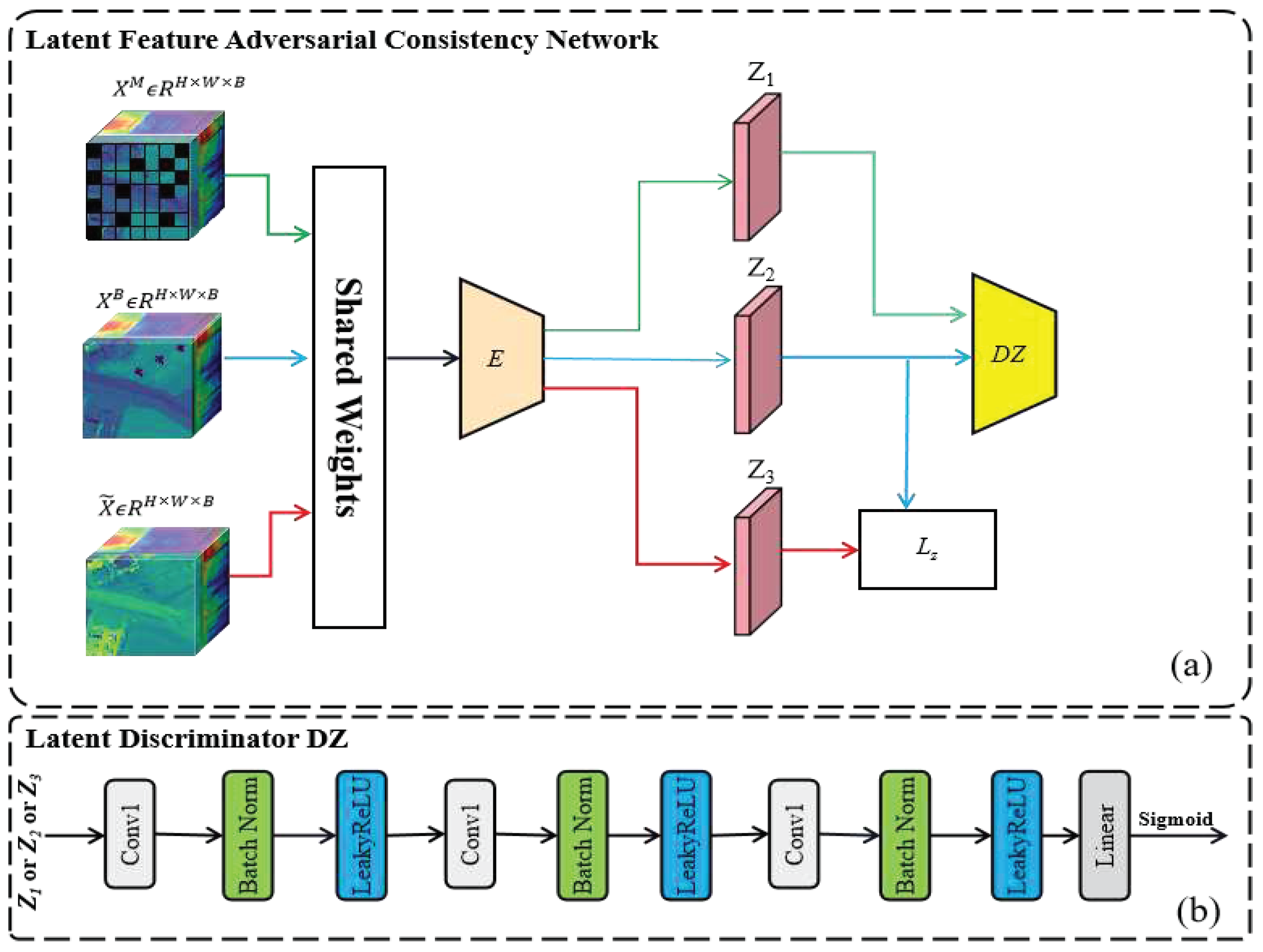

- Latent Feature Adversarial Consistency Network (LFACN): the latent feature adversarial consistency network, as illustrated in Figure 4(a), comprises an encoder and a discriminator for the latent features. The input samples and the prior background samples are respectively mapped to latent features and through an encoder with shared weights. In order to ensure that the latent features of the background exhibit similar distributions, we employ a latent feature discriminator to oppose the encoder which makes the latent feature of the input hyperspectral image as closely resembled as possible to the latent feature in adversarial situations. This approach directly learns the true distribution of the background. All the inputs can be effectively mapped to similar background latent features. Thereby, it enables accurate decoding of their corresponding pure background. And the latent feature which is obtained by mapping the reconstructed background through the encoder could also exhibit more similarity to the latent feature of the prior background samples . However, due to the deep network's inability to guarantee this point, a latent feature consistency loss is employed in order to strengthen the constraint.

2.3.3. Learning Procedure

2.4. Testing with the Original HSI

| Algorithm 1 Algorithm Flow Diagram of FCAE-DCAC |

|

Input: the original HSI Parameters: epoch, learning rate , (eps, mints), D, , and Output: final detection result. Stage 1: Extracting Prior Knowledge with Dual Clustering Obtain the prior anomaly samples , the prior background sample and the coarse label by (Eq. 1-3) Stage 2: Training for Fully Convolutional Auto-Encoder Acquire training samples by (Eq. 4) Initialize the network with random weights for each epoch do: FCAE update: , by Latent Feature Adversarial Consistency Network update: , by back-propagate and to change , , end Stage 3: Testing with the Original HSI Obtain the reconstructed HSI using the Original HSI as input by (Eq. 12) Calculate the degree of anomaly for each pixel in by (Eq. 13) |

3. Experiments and Analysis

3.1. Data Description

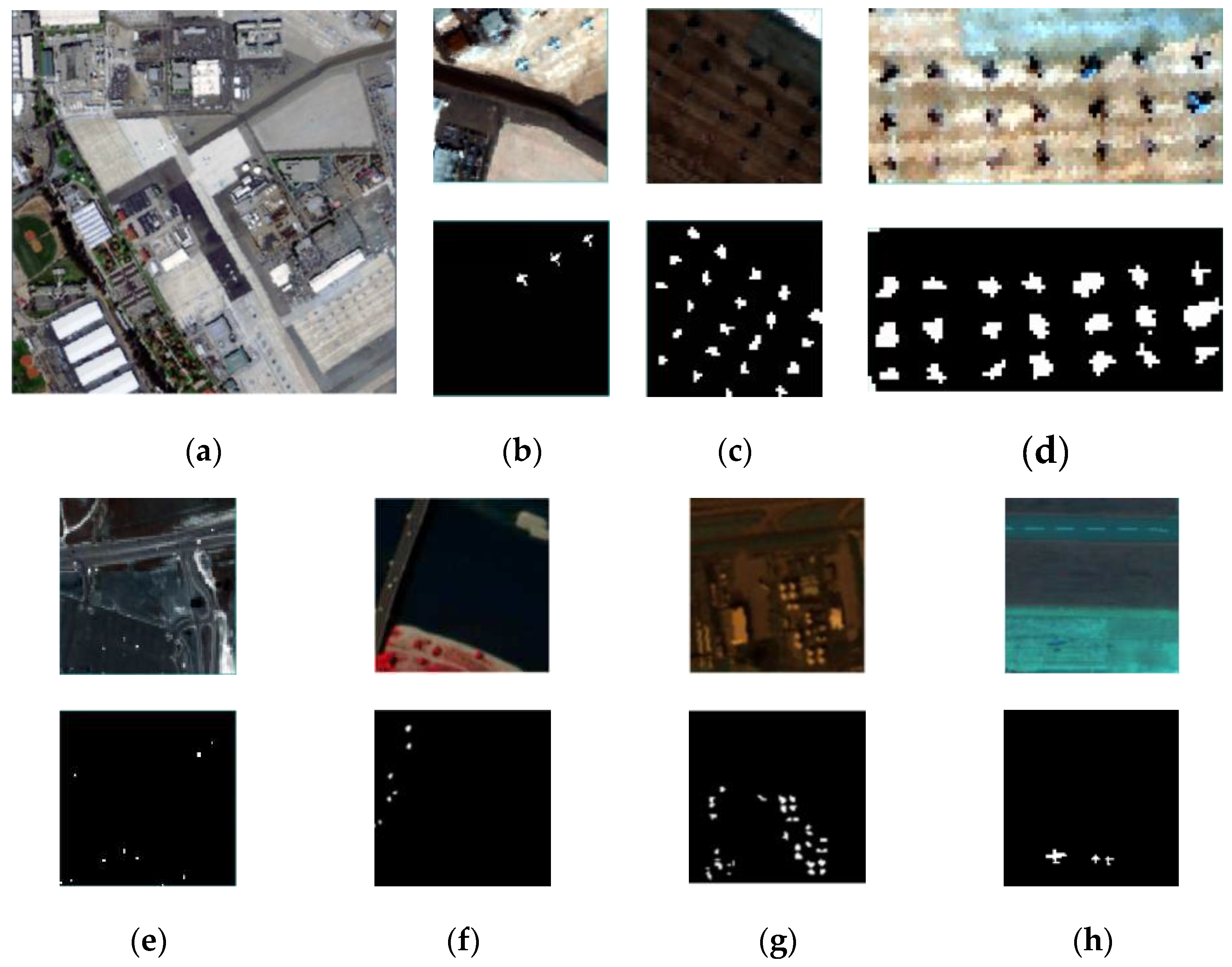

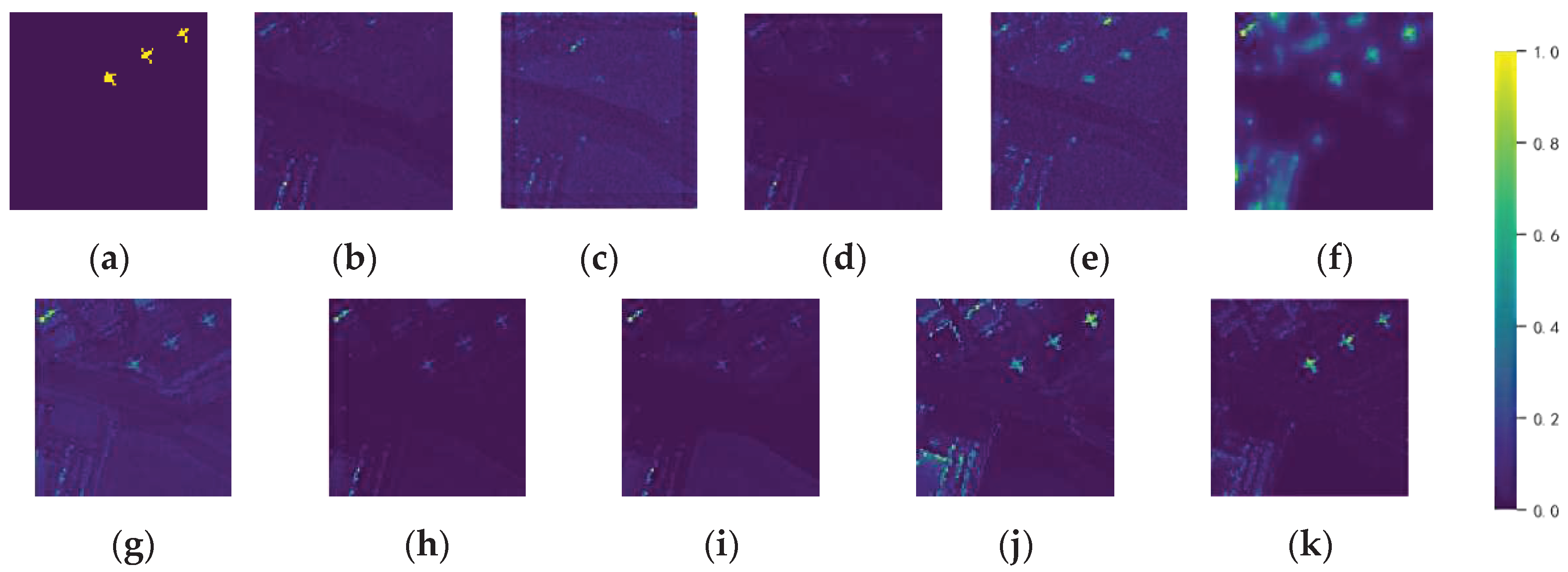

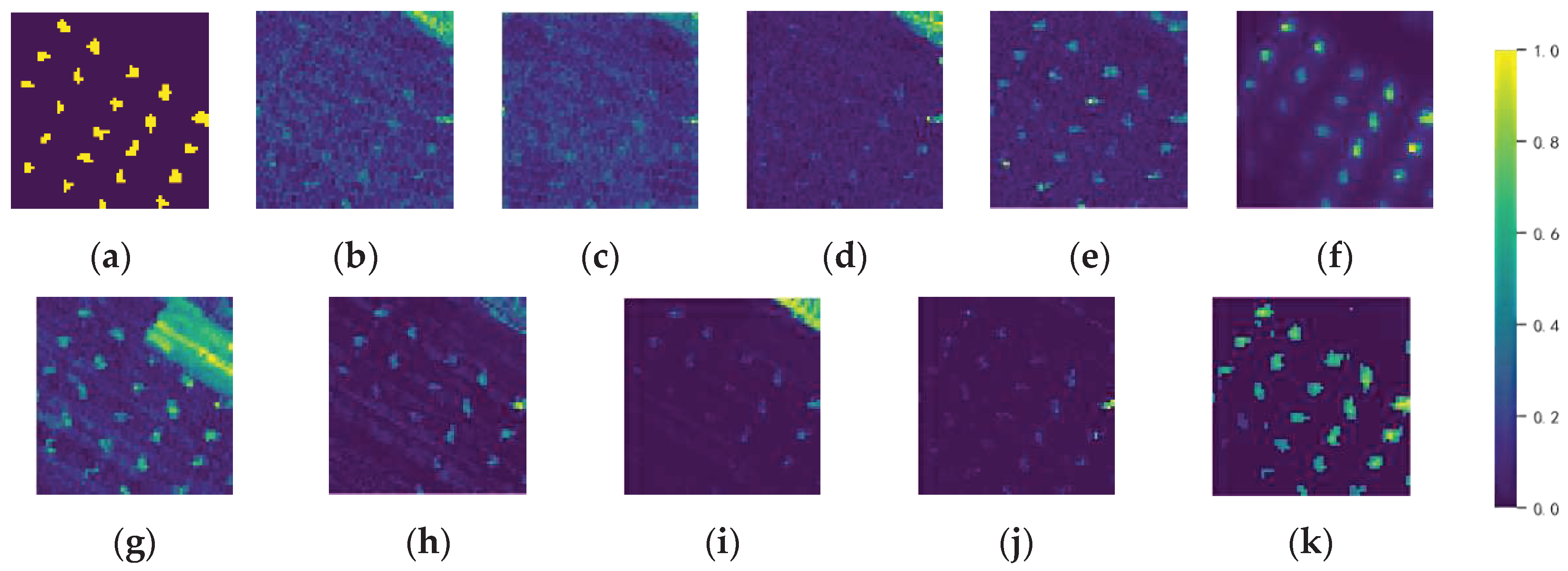

- (1)

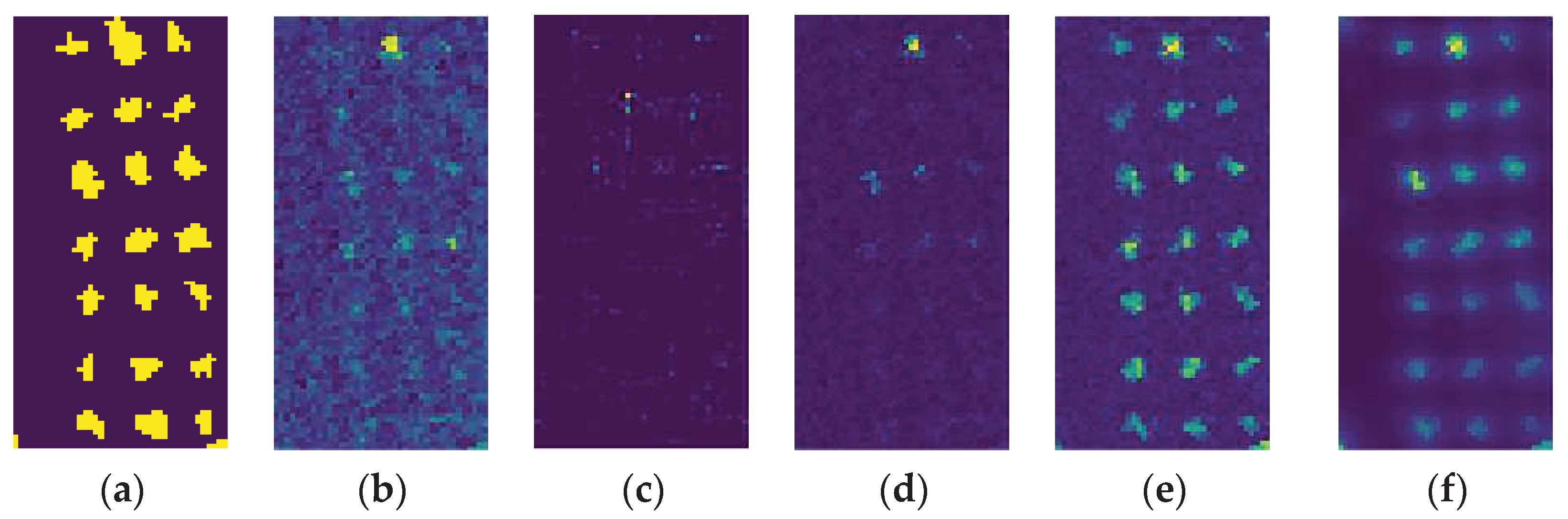

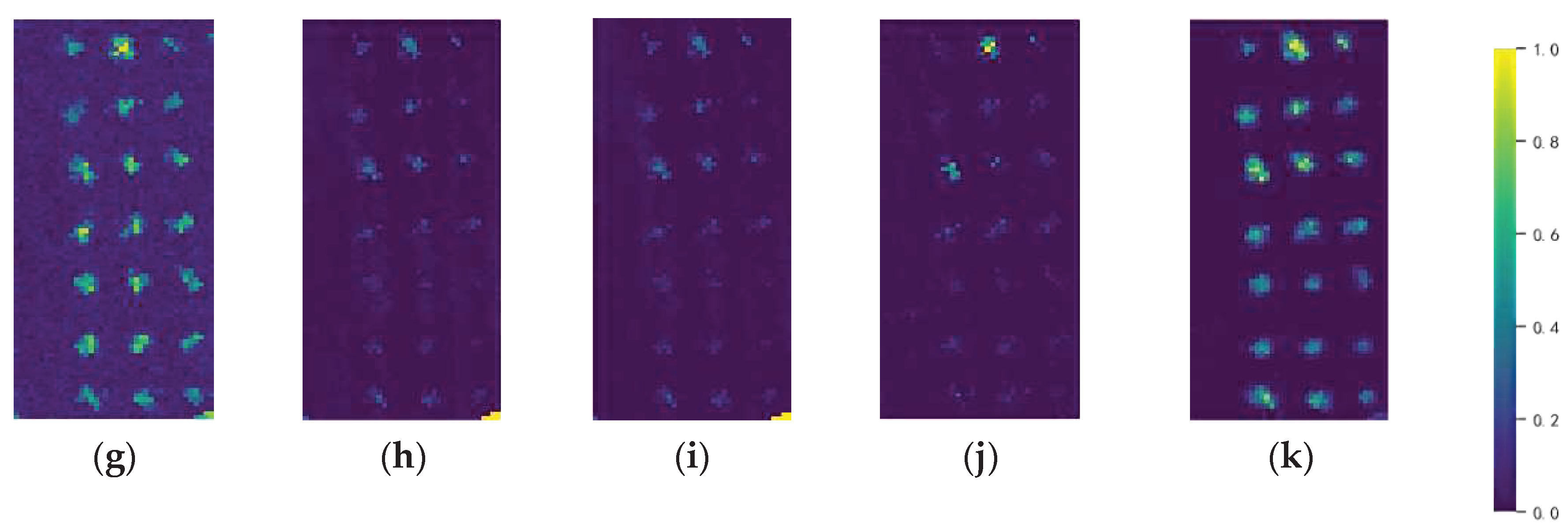

- San Diego Dataset: this dataset was acquired by the Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS) hyperspectral sensor over the San Diego airport area, CA, USA. The spatial resolution is 3.5 m. It’s original size was 400×400 as depicted in Figure 5(a). The image consists of a total of 224 spectral bands within the range of 370-2510 nm with 189 remained after excluding bands which were affected by water absorption and low signal-to-noise ratio. Within this dataset, three regions named San Diego-1, San Diego-2, and San Diego-3 were selected. Figure 5(b), Figure 5(c), and Figure 5(d) display the pseudocolor images and the ground-truth maps of these datasets. The image size of San Diego-1 is 100×100 and it contains three aircrafts with different sizes that are considered as anomaly targets. These anomaly targets are totally constituted with 58 pixels which account for 0.58% of the entire image. The image size of San Diego-2 is 60×60. Tarp, building and shadow are background land covers. Within this image, there are 22 densely distributed targets identified as anomalies. These anomaly targets are totally comprised with 214 pixels which account for 5.94% of the entire image. Similarly, the image size of San Diego-3 is 40×90 with tarp, building and shadow as background. In this image, there are 21 densely distributed targets identified as anomaly targets. These anomaly targets are totally comprised with 423 pixels which account for 11.75% of the entire image. It should be noted that the spectral curves of building in the upper right corner significantly differ from other background features in San Diego-2 image. Furthermore, the proportion occupied by this building is not as substantial as the other two types of background. Consequently, there are some challenges and difficulties in modeling and analyzing the background features in these datasets.

- (2)

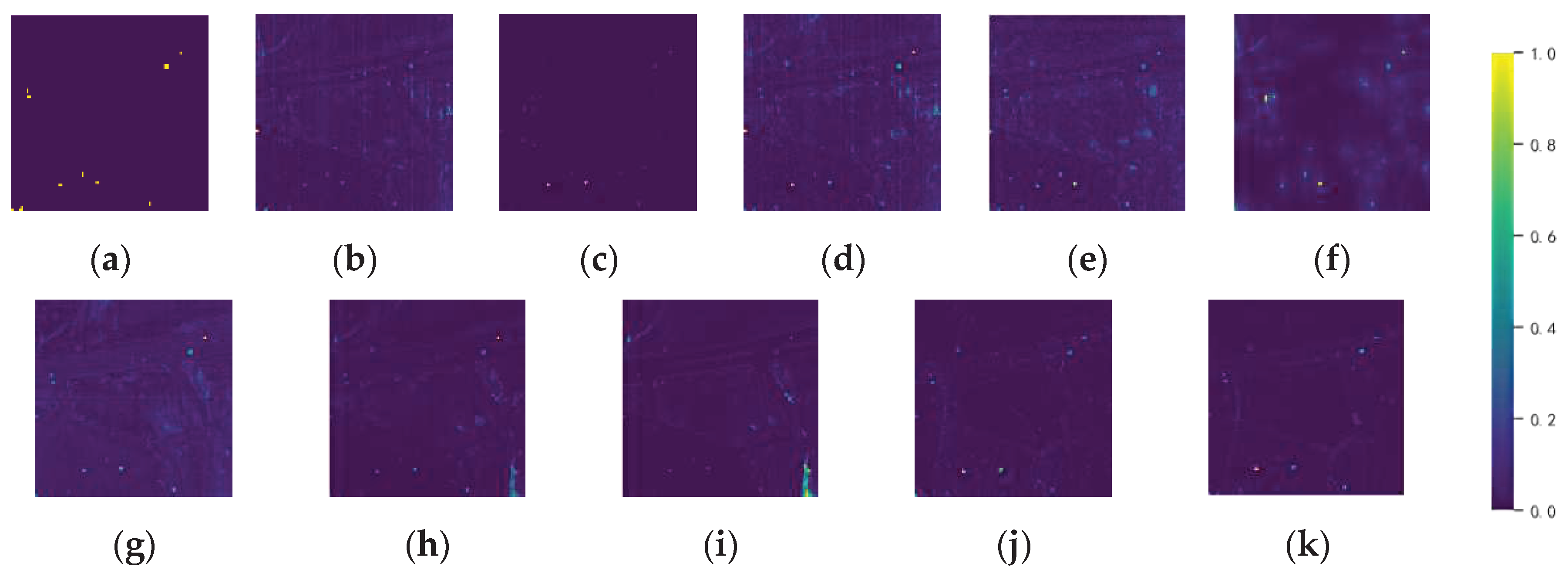

- Hyperspectral Digital Imagery Collection Experiment (HYDICE) Dataset: this dataset was acquired by the HYDICE sensor over a suburban residential area in Michigan, USA. The spatial resolution is 3 m, and the image size is 80×100. There are 210 spectral bands within the range of 400-2500 nm, with 175 remained after eliminating noise and water vapor absorption bands. This hyperspectral dataset includes background land covers such as parking lots, soil, water bodies, and roads. Figure 5(e) displays the pseudocolor image and the ground-truth map of this dataset. Ten vehicles are considered as anomaly targets and they are comprised of 17 pixels which account for 0.21% of the entire image.

- (3)

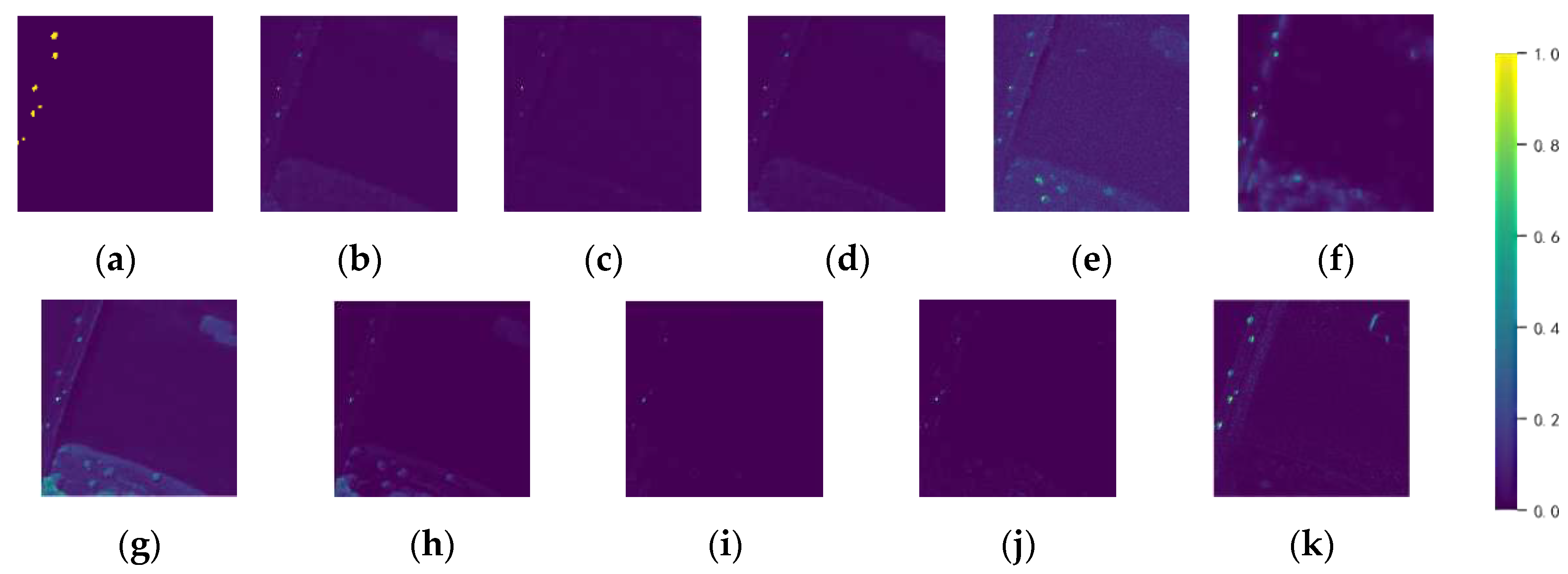

- Pavia Dataset: this dataset was acquired by the Reflective Optics System Imaging Spectrometer (ROSIS) in the center of Pavia, northern Italy. The spatial resolution is 1.3 m and the image size is 150×150. This dataset consists of 102 spectral bands within the range of 430-860 nm. Figure 5(f) displays the pseudocolor image and the ground-truth map of this dataset. The background land covers captured in this dataset include bridges, water bodies and bare soil, while the anomaly targets are vehicles on the bridge. These anomaly targets are comprised of totally 63 pixels which account 0.28% of the entire image.

- (4)

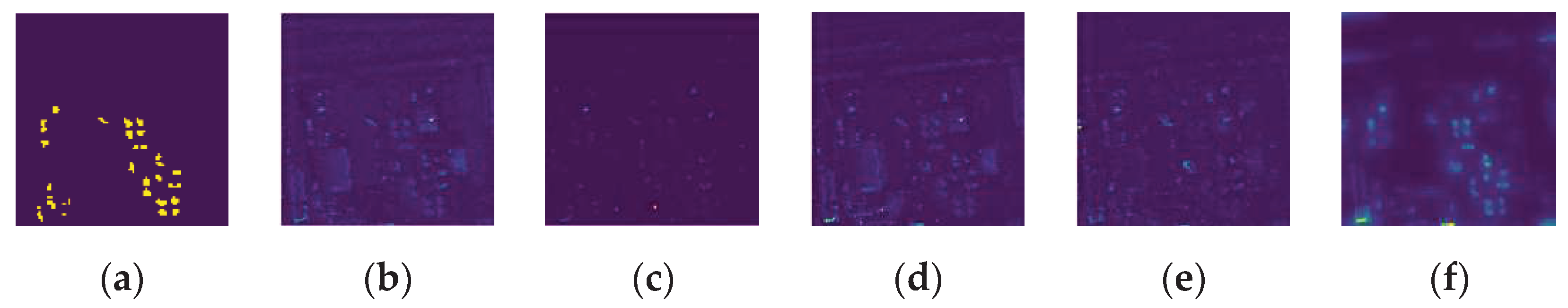

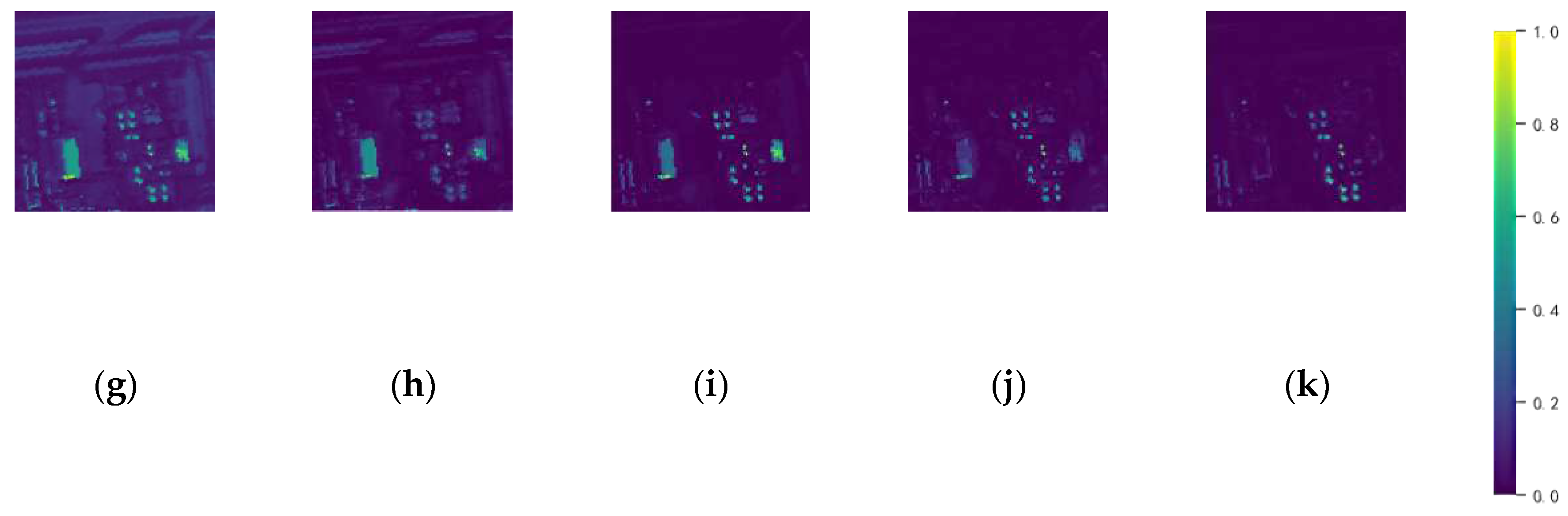

- Los Angeles-1 (LA-1) Dataset: this dataset was acquired by the AVIRIS sensor over the Los Angeles area. The spatial resolution is 7.5 m and the image size is 100×100. It encompasses a total of 205 spectral bands within the range of 430-860 nm. Figure 5(g) displays the pseudocolor image and the ground-truth map of this dataset. Notably, there are a few houses that are considered anomaly targets in these images which are comprised of a total of 232 pixels and accounting for 2.32% of the entire image.

- (5)

- Gulfport Dataset: this dataset was acquired by the AVIRIS sensor over Gulfport, Southern, MS, USA in 2010. The spatial resolution is 3.4 m and the image size is 100×100. After eliminating bands with low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), a total of 191 bands remained. The spectral coverage spans from 400 to 2500 nm. Figure 5(h) displays the pseudocolor image and the ground-truth map of this dataset. Three airplanes of various sizes are identified as anomaly targets which are comprised of a total of 60 pixels and account for 0.60% of the entire image.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

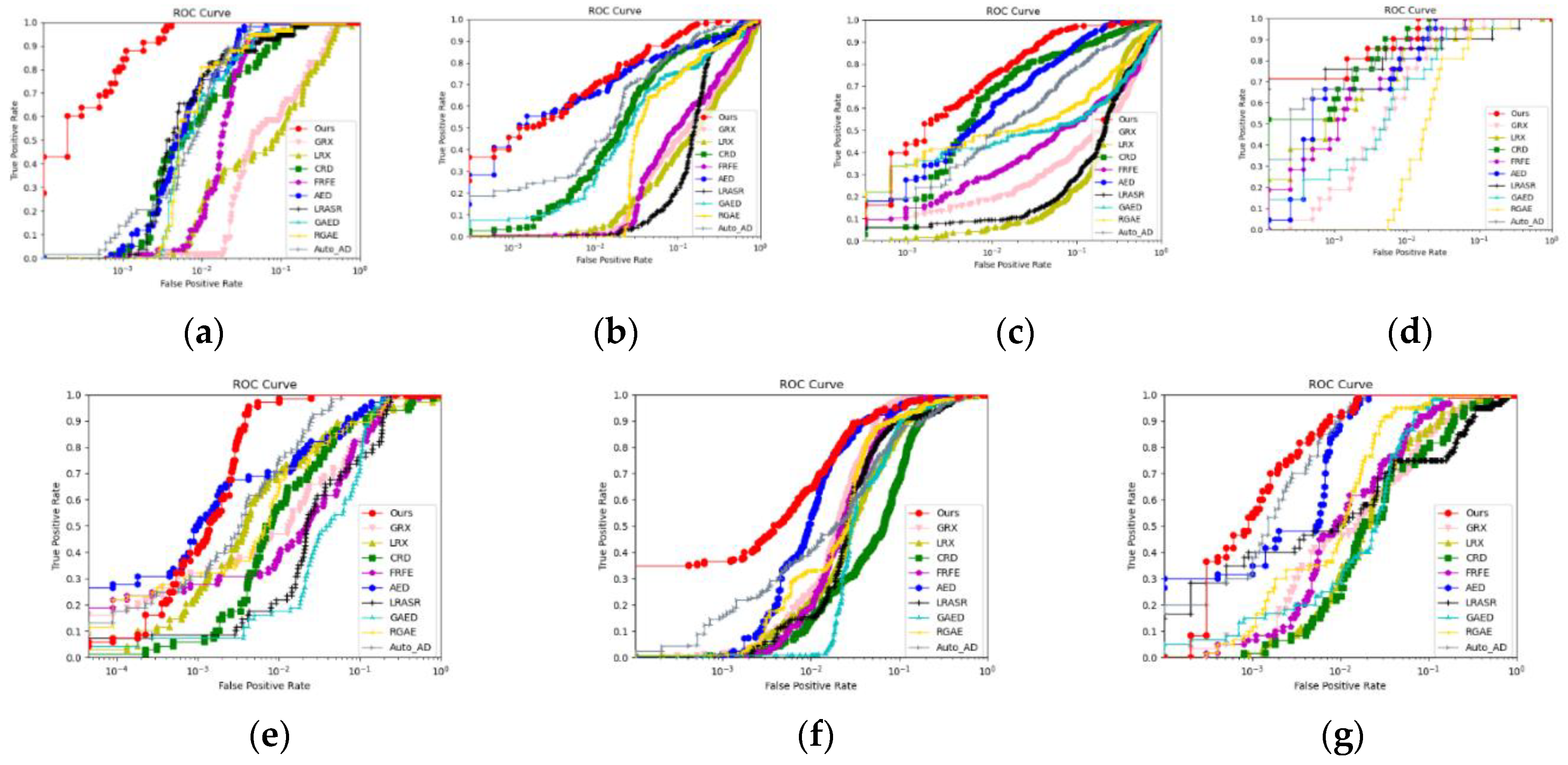

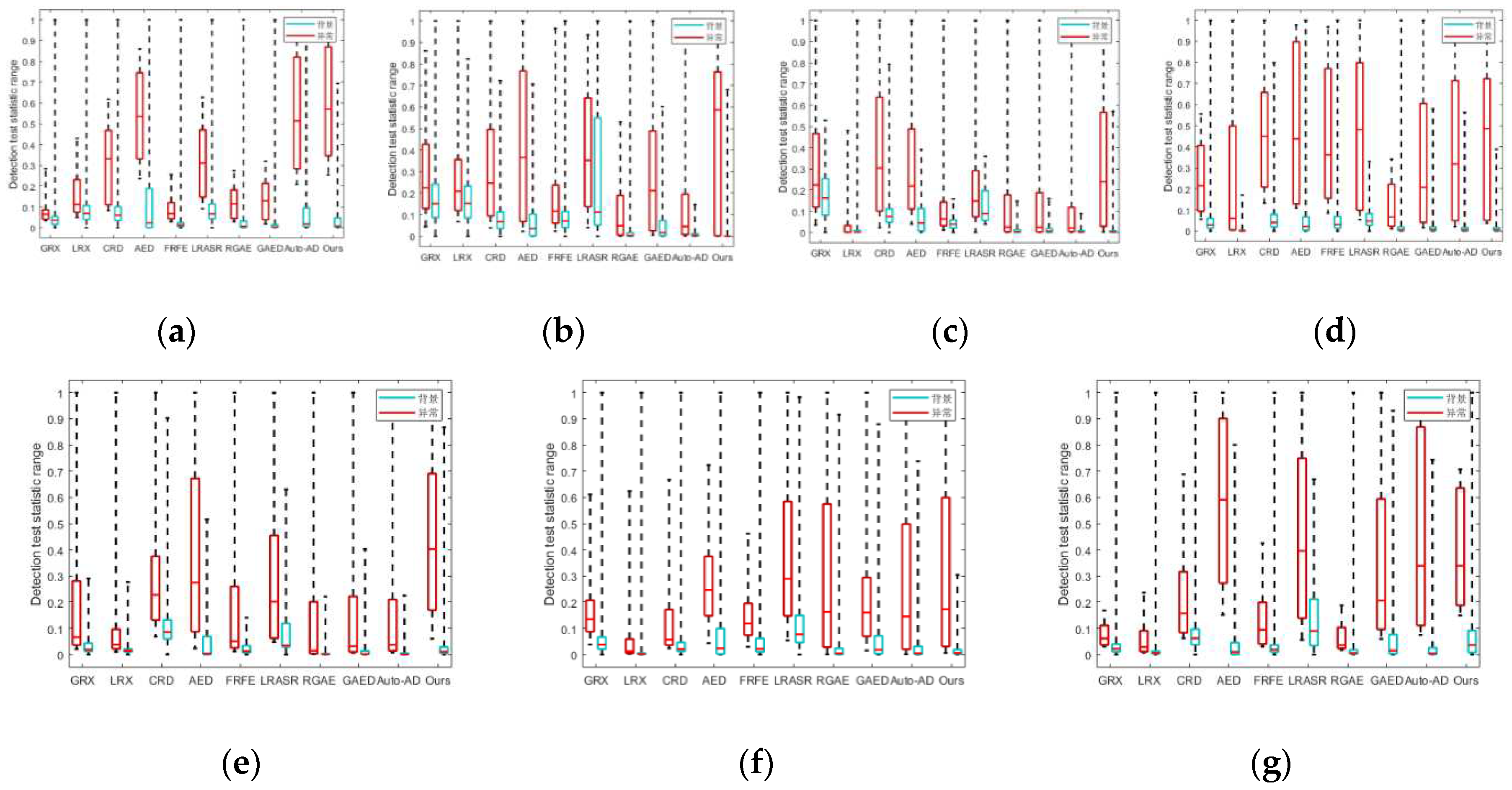

3.3. Detection Performance

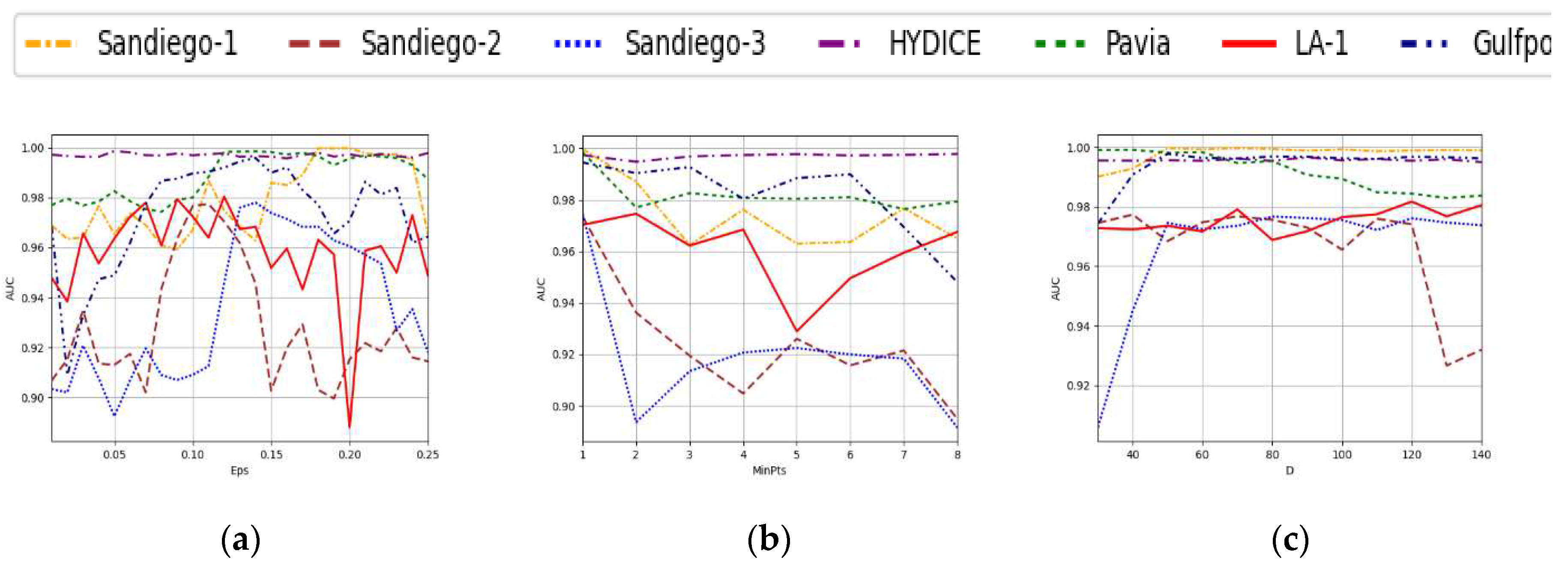

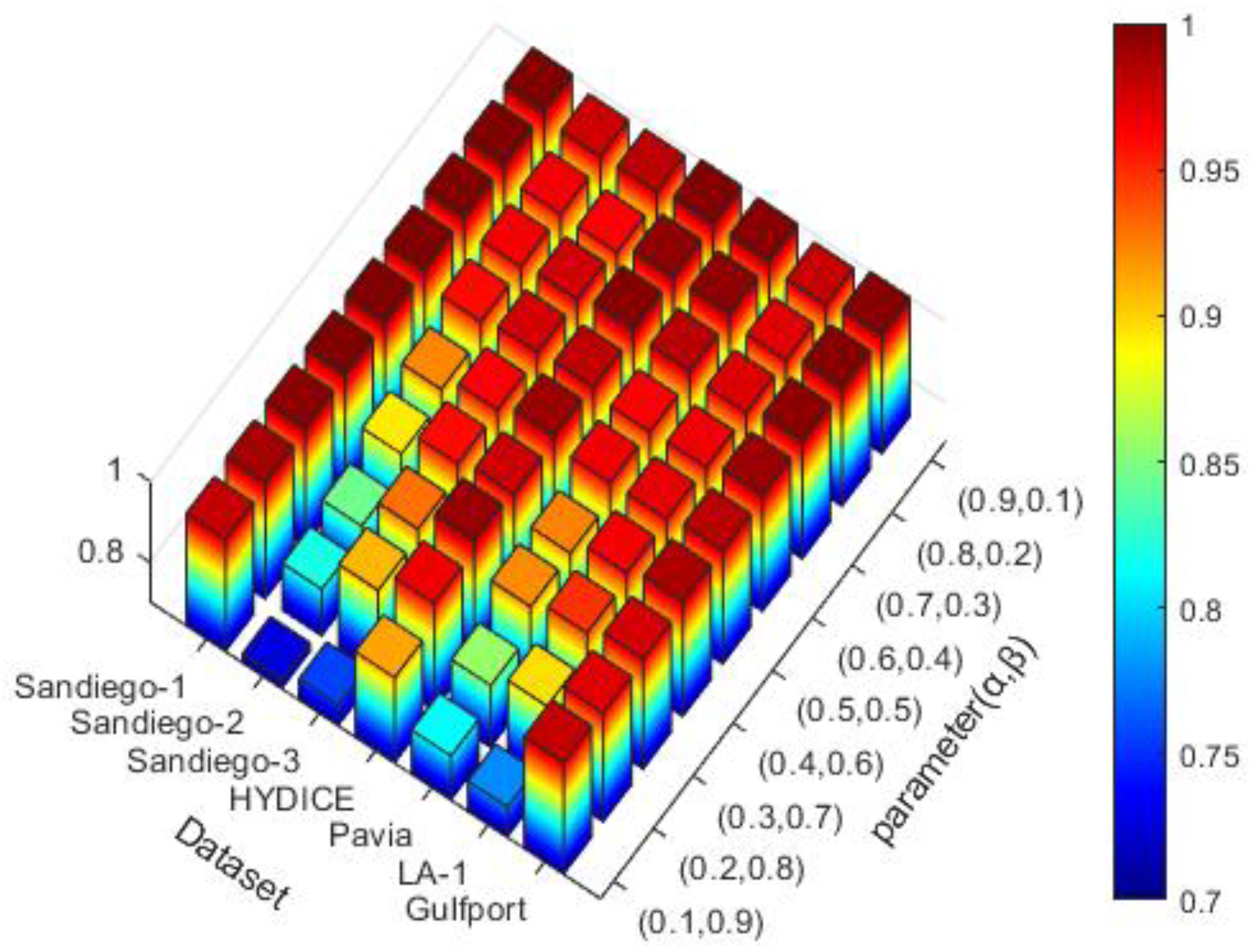

3.4. Parametric Analysis

3.5. Ablation Study

3.6. Comparison of Inference Times

4. Conclusions

References

- Su, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral anomaly detection: A survey. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2021, 10, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza Shah, N.; Maud, A.R.M.; Bhatti, F.A.; Ali, M.K.; Khurshid, K.; Maqsood, M.; Amin, M. Hyperspectral anomaly detection: a performance comparison of existing techniques. International Journal of Digital Earth 2022, 15, 2078–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-I. Hyperspectral anomaly detection: A dual theory of hyperspectral target detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioucas-Dias, J.M.; Plaza, A.; Camps-Valls, G.; Scheunders, P.; Nasrabadi, N.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral remote sensing data analysis and future challenges. IEEE Geoscience and remote sensing magazine 2013, 1, 6–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. Two-stream convolutional networks for hyperspectral target detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 59, 6907–6921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Meng, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, G.; Sun, W. Feature-Decision Level Collaborative Fusion Network for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Classification. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Marinelli, D.; Bruzzone, L.; Bovolo, F. A review of change detection in multitemporal hyperspectral images: Current techniques, applications, and challenges. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2019, 7, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolakis, D.; Truslow, E.; Pieper, M.; Cooley, T.; Brueggeman, M. Detection algorithms in hyperspectral imaging systems: An overview of practical algorithms. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2013, 31, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Sun, X.; Sun, X.; Zhuang, L.; Du, Q.; Zhang, B. Hyperspectral anomaly detection based on chessboard topology. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-I.; Chiang, S.-S. Anomaly detection and classification for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE transactions on geoscience and remote sensing 2002, 40, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiler, J.; Ziemann, A.; Matteoli, S.; Diani, M. Spectral variability of remotely sensed target materials: Causes, models, and strategies for mitigation and robust exploitation. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2019, 7, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Song, J.; Qin, H.; Tan, W.; Li, H.; Zhou, H. Visual attention and background subtraction with adaptive weight for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 14, 2270–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteoli, S.; Diani, M.; Theiler, J. An overview of background modeling for detection of targets and anomalies in hyperspectral remotely sensed imagery. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2014, 7, 2317–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, I.S.; Yu, X. Adaptive multiple-band CFAR detection of an optical pattern with unknown spectral distribution. IEEE transactions on acoustics, speech, and signal processing 1990, 38, 1760–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, J.M.; Garzon, E.M.; Garcia, I.; Plaza, A. Analysis and optimizations of global and local versions of the RX algorithm for anomaly detection in hyperspectral data. IEEE journal of selected topics in applied earth observations and remote sensing 2013, 6, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaum, A. Joint subspace detection of hyperspectral targets. In Proceedings of 2004 IEEE Aerospace Conference Proceedings (IEEE Cat. No. 04TH8720). [Google Scholar]

- Du, B.; Zhang, L. A discriminative metric learning based anomaly detection method. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2014, 52, 6844–6857. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Kernel RX-algorithm: A nonlinear anomaly detector for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2005, 43, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Kwan, C.; Ayhan, B.; Eismann, M.T. A novel cluster kernel RX algorithm for anomaly and change detection using hyperspectral images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2016, 54, 6497–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. A robust nonlinear hyperspectral anomaly detection approach. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2014, 7, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, B.; Ran, Q.; Gao, L.; Li, J.; Plaza, A. Weighted-RXD and linear filter-based RXD: Improving background statistics estimation for anomaly detection in hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2014, 7, 2351–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, W.; Li, H.-C.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral anomaly detection by fractional Fourier entropy. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2019, 12, 4920–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, Q. Collaborative representation for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on geoscience and remote sensing 2014, 53, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. A low-rank and sparse matrix decomposition-based Mahalanobis distance method for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2015, 54, 1376–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, W.; Guo, R.; Ayhan, B.; Kwan, C.; Vance, S.; Qi, H. Hyperspectral anomaly detection through spectral unmixing and dictionary-based low-rank decomposition. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2018, 56, 4391–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Plaza, A.; Wei, Z. Anomaly detection in hyperspectral images based on low-rank and sparse representation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2015, 54, 1990–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatsanos, N.P.; Katsaggelos, A.K. Methods for choosing the regularization parameter and estimating the noise variance in image restoration and their relation. IEEE Transactions on image processing 1992, 1, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Li, K.; Li, J.; Benediktsson, J.A. Hyperspectral anomaly detection with attribute and edge-preserving filters. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 55, 5600–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Lei, J. Structure tensor and guided filtering-based algorithm for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 4218–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Meng, X.; Shao, F.; Li, S. Supervised-unsupervised combined deep convolutional neural networks for high-fidelity pansharpening. Information Fusion 2023, 89, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Meng, X.; Chen, H.; Shao, F.; Sun, W. Dual-Task Interactive Learning for Unsupervised Spatio-Temporal-Spectral Fusion of Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xie, C.; Fan, Z.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, L.; Wei, X.; Hong, D.; Li, G.; Zeng, X. Hyperspectral anomaly detection using deep learning: A review. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, G.; Du, Q. Transferred deep learning for anomaly detection in hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2017, 14, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, W.; Qu, Y.; Gao, L.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, B. Transferable network with Siamese architecture for anomaly detection in hyperspectral images. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 106, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Song, J. Hyperspectral anomaly detection via convolutional neural network and low rank with density-based clustering. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2019, 12, 3637–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bati, E.; Çalışkan, A.; Koz, A.; Alatan, A.A. Hyperspectral anomaly detection method based on auto-encoder. Proceedings of Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XXI; pp. 220–226.

- Arisoy, S.; Nasrabadi, N.M.; Kayabol, K. GAN-based hyperspectral anomaly detection. Proceedings of 2020 28th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO); pp. 1891–1895.

- Racetin, I.; Krtalić, A. Systematic review of anomaly detection in hyperspectral remote sensing applications. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Du, Q. Discriminative reconstruction constrained generative adversarial network for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 4666–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Ali, S.; Jung, S.K.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral anomaly detection with guided autoencoder. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Ma, Y.; Mei, X.; Fan, F.; Huang, J.; Ma, J. Hyperspectral anomaly detection with robust graph autoencoders. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Vizziello, A.; Gamba, P. RSAAE: Residual Self-Attention-Based Autoencoder for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Y. Auto-AD: Autonomous hyperspectral anomaly detection network based on fully convolutional autoencoder. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhuang, L.; Gao, L.; Sun, X.; Huang, M.; Plaza, A. PDBSNet: Pixel-shuffle Down-sampling Blind-Spot Reconstruction Network for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, D.; Zhuang, L.; Sun, X.; Huang, M.; Plaza, A. BS 3 LNet: A new blind-spot self-supervised learning network for hyperspectral anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; pp. 16000–16009.

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Ling, Q.; Lin, Z.; An, W. You Only Train Once: Learning a General Anomaly Enhancement Network With Random Masks for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolakis, D.; Shaw, G. Detection algorithms for hyperspectral imaging applications. IEEE signal processing magazine 2002, 19, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, A.P. The use of the area under the ROC curve in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. Pattern recognition 1997, 30, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, C.; Hernández-Orallo, J.; Flach, P.A. A. A coherent interpretation of AUC as a measure of aggregated classification performance. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-11); pp. 657–664.

| Dataset | of Different Methods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRX | LRX | FRFE | CRD | AED | LRASR | GAED | RGAE | Auto-AD | Ours | |

| Sandiego-1 | 0.8736 | 0.8570 | 0.9787 | 0.9768 | 0.9900 | 0.9824 | 0.9861 | 0.9854 | 0.9895 | 0.9994 |

| Sandiego-2 | 0.7499 | 0.7211 | 0.7821 | 0.9290 | 0.9399 | 0.8065 | 0.8905 | 0.8819 | 0.9466 | 0.9773 |

| Sandiego-3 | 0.7125 | 0.7540 | 0.7694 | 0.9485 | 0.9659 | 0.7214 | 0.7811 | 0.8341 | 0.9163 | 0.9815 |

| HYDICE | 0.9857 | 0.9911 | 0.9933 | 0.9976 | 0.9951 | 0.9744 | 0.9843 | 0.9646 | 0.9951 | 0.9980 |

| Pavia | 0.9538 | 0.9525 | 0.9457 | 0.9510 | 0.9793 | 0.9380 | 0.9398 | 0.9688 | 0.9914 | 0.9979 |

| LA-1 | 0.9692 | 0.9492 | 0.9655 | 0.9229 | 0.9780 | 0.9440 | 0.9424 | 0.9569 | 0.9406 | 0.9808 |

| Gulfport | 0.9526 | 0.9532 | 0.9722 | 0.9342 | 0.9953 | 0.9120 | 0.9705 | 0.9842 | 0.9968 | 0.9975 |

| Average | 0.8853 | 0.8826 | 0.9153 | 0.9514 | 0.9777 | 0.8970 | 0.9278 | 0.9394 | 0.9680 | 0.9903 |

| Component | of different cases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandiego-1 | Sandiego-2 | Sandiego-3 | HYDICE | Pavia | LA-1 | Gulfport | |

| FCAE without SSJA | 0.9732 | 0.8785 | 0.8567 | 0.9887 | 0.9600 | 0.9168 | 0.9679 |

| FCAE | 0.9786 | 0.8864 | 0.8630 | 0.9920 | 0.9686 | 0.9229 | 0.9763 |

| FCAE+ | 0.9975 | 0.9221 | 0.9336 | 0.9961 | 0.9881 | 0.9669 | 0.9822 |

| FCAE++ LFACN | 0.9996 | 0.9763 | 0.9722 | 0.9979 | 0.9932 | 0.9791 | 0.9957 |

| Dataset | Inference Time of different detectors | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRX | LRX | FRFE | CRD | AED | LRASR | GAED | RGAE | Auto-AD | Ours | |

| Sandiego-1 | 0.2146 | 9.1735 | 9.8865 | 3.9145 | 0.2107 | 46.3339 | 0.0305 | 0.0335 | 0.0210 | 0.0390 |

| Sandiego-2 | 0.3168 | 25.6535 | 14.9289 | 5.0192 | 0.2456 | 57.3001 | 0.0394 | 0.0570 | 0.0275 | 0.0185 |

| Sandiego-3 | 0.0998 | 18.2074 | 5.4494 | 2.1902 | 0.1884 | 19.2353 | 0.0150 | 0.0157 | 0.0160 | 0.0210 |

| HYDICE | 0.2146 | 9.1735 | 9.8865 | 3.9145 | 0.2107 | 46.3339 | 0.0305 | 0.0335 | 0.0210 | 0.0235 |

| Pavia | 0.9823 | 16.8106 | 33.5833 | 5.3146 | 0.3625 | 61.1938 | 0.1072 | 0.0476 | 0.0305 | 0.0355 |

| LA-1 | 0.3173 | 14.2751 | 21.3859 | 5.3762 | 0.2242 | 72.0277 | 0.0345 | 0.0459 | 0.0240 | 0.0330 |

| Gulfport | 0.5988 | 13.7447 | 13.6096 | 5.0287 | 0.2652 | 63.4349 | 0.0620 | 0.0373 | 0.0220 | 0.0275 |

| Average | 0.3771 | 14.6755 | 14.9511 | 4.1165 | 0.2563 | 48.4835 | 0.0436 | 0.0366 | 0.0229 | 0.0283 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).