1. Introduction

The increasing occurrence of metastatic tumors in the adrenal glands, originating from various types of cancers such as lung, breast, colorectal, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and melanoma, presents substantial challenges in the field of oncology [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Studies indicate that adrenal metastatic presence can be as high as 27% in patients with widespread cancer [

5,

6].

While the efficacy of direct adrenal interventions is yet to be established through randomized studies, the role of surgical resection, particularly for isolated adrenal metastases, has gained recognition in observational studies. [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]

However, surgical procedures like adrenalectomy are often hampered by individual health concerns and the intricacies of the operations, resulting in prolonged hospital admissions [

1,

2,

3,

4].

In contrast, Computed Tomography (CT)-guided methods such as radiofrequency and microwave ablation have demonstrated encouraging one-year survival rates without local recurrence, ranging from 70.5% to 82% in the treatment of adrenal metastases [

1,

2,

3].

CT-guided cryoablation of AMs, a more recent development, offers several benefits including clear visualization of the treated area, minimized discomfort, and expedited recovery, and promising results in recent studies, although its ultimate efficacy is still under evaluation [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the retrospective nature of the study.

The study involved 12 patients who received 13 CT-guided cryoablation procedures for AMs from January 2016 to December 2020.

Eligibility criteria included patients unsuitable for surgery, tumor size ≤5 cm, controlled or absent extra-adrenal tumors, and life expectancy ≥3 months. Exclusion criteria were adrenal vein invasion, significant coagulation disorders, active infections, or bleeding (

Table 1).

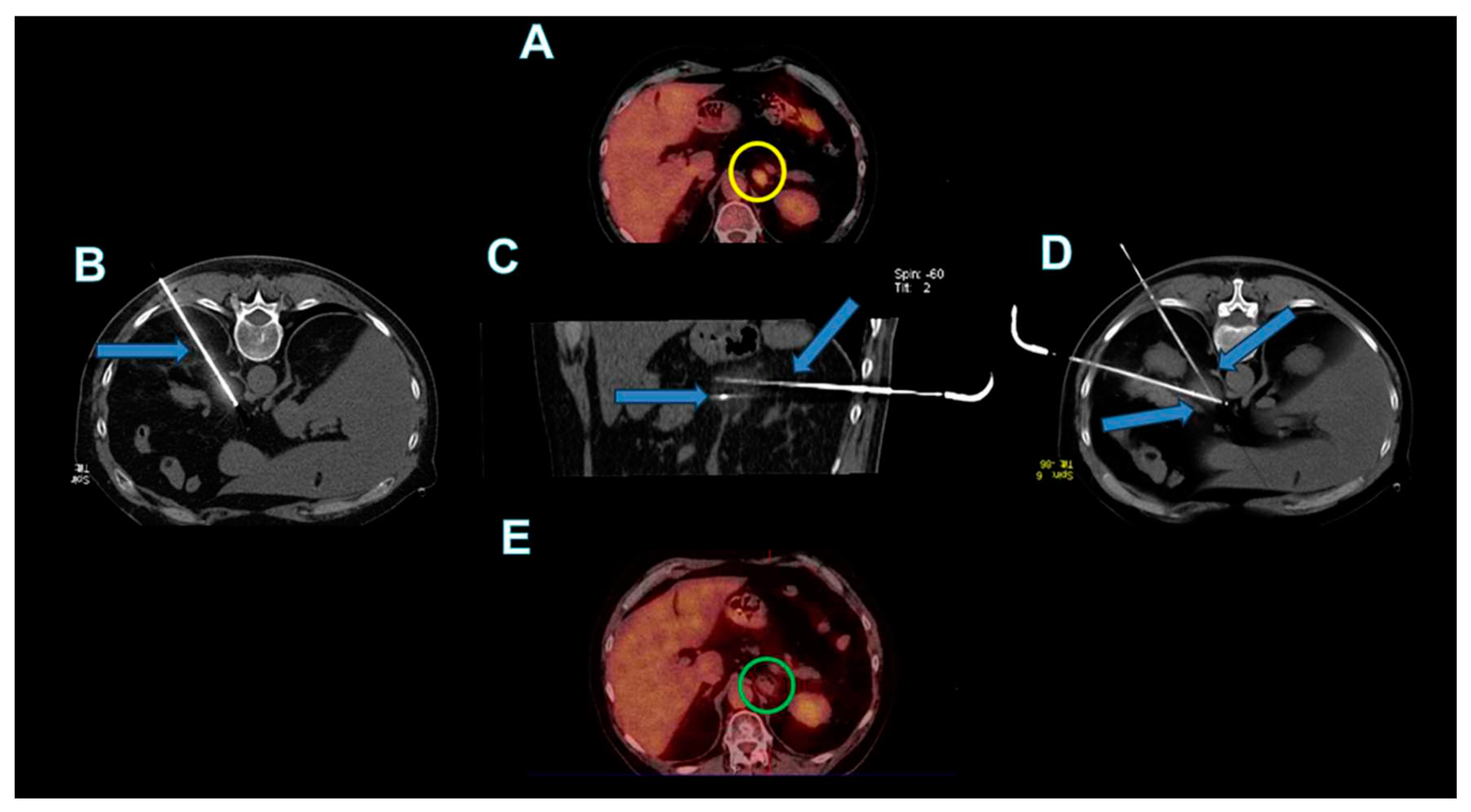

Diagnosis involved patient history, abdominal CT/Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and biopsy results, complemented by fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) for detecting extra-adrenal tumors.

The procedures were carried out by two expert interventional radiologists. Informed consent was secured from parents or guardians, and patients were briefed on possible complications. Prior to the procedure, the skin entry site was anesthetized using 1% Lidocaine, and patients received conscious sedation with Midazolam and Tramadol. The interventions utilized a multidetector CT system (SOMATOM go.Top 128, SIEMENS Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). An initial non-contrast CT scan was conducted to ascertain the morphological features of the lesion.

Following this, the cryoablation was carried out utilizing a cryoablation system (VISUAL ICE, Galil Medical-Boston Scientific, Arden Hills, MN, USA). This system was equipped with a single 17G insulated cryoprobe that could create ablation zones of varying diameters: IceSphere 1.5 (22 × 28 mm at −20 °C) and IceRod 1.5 (29 × 45 mm at −20 °C)(

Table 2).

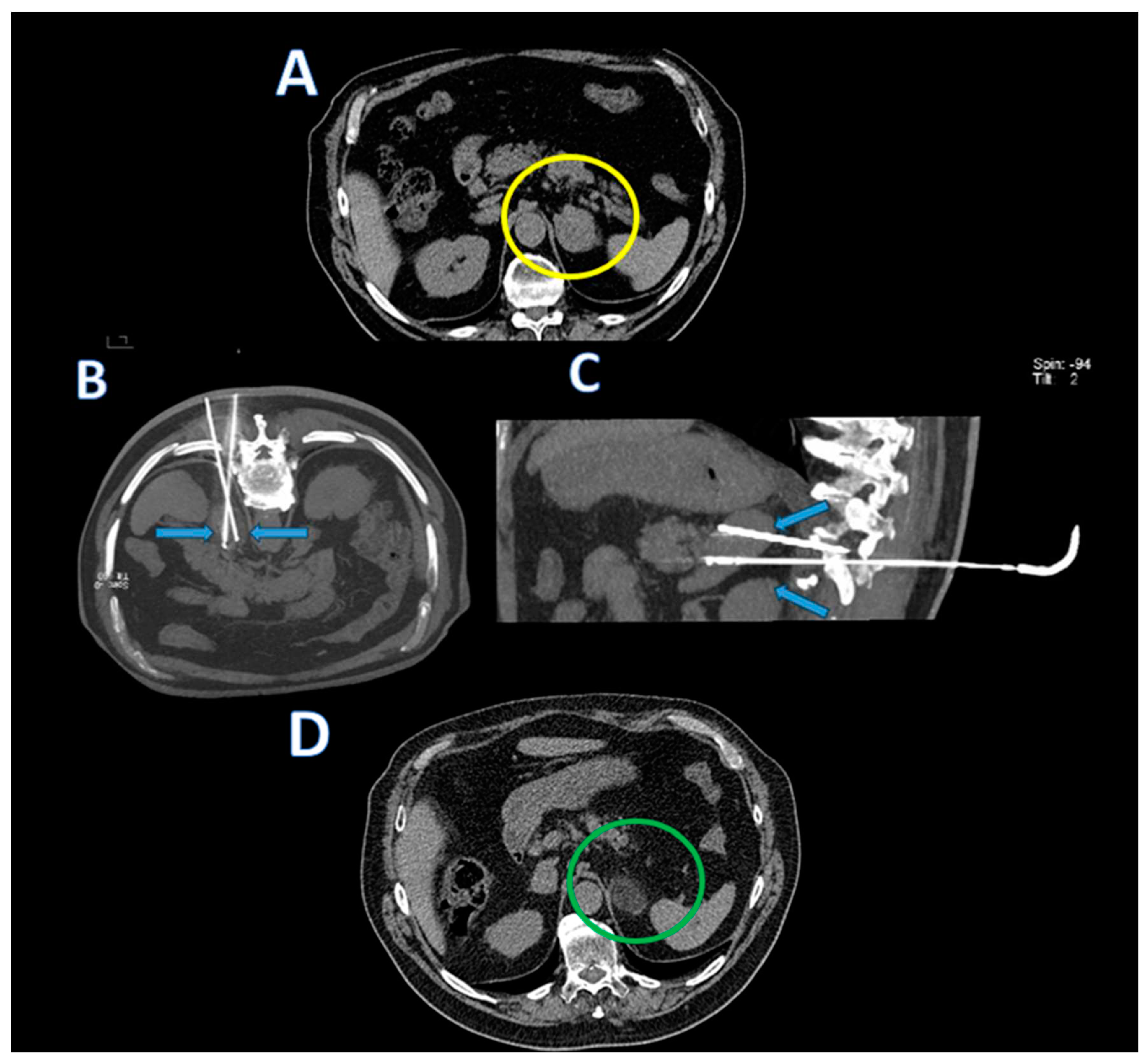

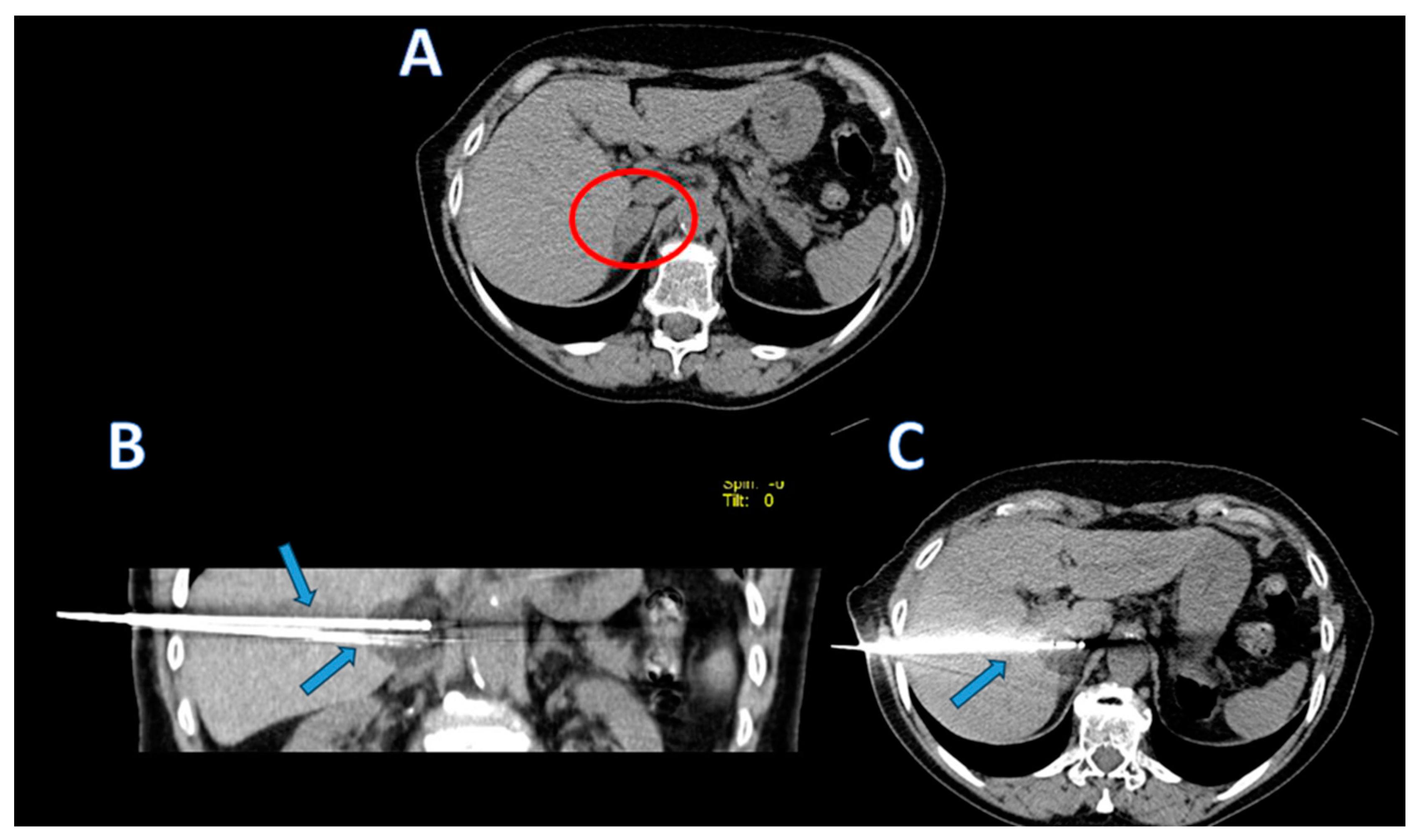

The cryoprobes were coaxially inserted into the adrenal lesions (as shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Scans during the procedure were taken to verify the placement and orientation of the instrument. The procedure involved a single 10-minute freezing cycle, followed by an 8-minute passive thawing phase. Freezing cycle was repeated twice. Post-freezing phase, non-contrast CT images were captured to evaluate the ice ball’s coverage and to identify any immediate complications.

After the end of the cryoablation procedures, abdominal CT images were acquired in all patients to detect early complications.

Patients were monitored during the first 24 h and then discharged one day after the procedure if there was no discomfort.

Regular physical and laboratory evaluations, comprising blood cell count analysis, adrenal hormone measurements, and tumor marker monitoring based on the histological characteristics of the primary tumor, were conducted monthly.

After adrenal cryoablation treatments and during the entire clinical and radiologic follow-up period, all the patients continued to receive their usual systemic therapies.

Regularly scheduled CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, both with and without contrast, were conducted for patients at intervals of 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-cryoablation, followed by biannual scans. The scanning protocols mirrored those used initially to evaluate the adrenal tumor lesions before the cryoablation.

Two months after the procedure, a complete disappearance of contrast enhancement in CT imaging was interpreted as a full response to the ablation treatment. By the sixth month, any alterations in contrast enhancement or size increases of the treated areas seen in CT scans were indicative of potential recurrence or progression of the disease. The schedule for these radiological evaluations was largely influenced by the understanding that early post-procedure CT scans (within the first 30 days) can show intense enhancement of the treated areas due to the inflammatory response triggered by the cryoablation process [

20].

Hormonal analysis, including adrenal hormone levels, was conducted to assess the treatment's impact on adrenal function.

All cryoablation sessions were successfully completed.

The CT scans executed following the procedures showcased the iceball's expansion, extending 1 cm past the tumor borders, establishing a safety margin. The tolerance level for all procedures was high and no complications associated with the procedure were observed. A group of 12 patients with AMs underwent cryoablation treatment. Each of these patients presented with a singular adrenal tumor. Prior to the cryoablation process, none of these individuals had undergone adrenal resection.

The primary technical success was achieved in 11 out of 12 patients, equating to a success rate of 91.7%. One patient exhibited residual tumor activity and thus required a subsequent round of cryoablation, leading to a secondary technical success rate of 100%.

Over a follow-up period ranging from 8 to 24 months (with a mean of 16.3 ± 5.1 months), six patients underwent additional systemic therapy post-cryoablation. In this subgroup, three patients had developed extra-adrenal tumors. Local tumor recurrence was observed in two patients (16.7%), occurring within a span of 6 to 20 months (median: 13 months). One patient was treated with another session of cryoablation due to local recurrence, without further local recurrences in subsequent CT scans.

Five patients demonstrated systemic progression, including two with renal cancer recurrence, two with NSCLC cancer recurrence and one developing multiples bone metastasis.

Five patients died during the study period, with causes of death including tumor progression (four cases) and heart failure (one case). The average overall survival duration was determined to be 26.4 ± 5.6 months (95% CI: 20.2–32.6).

3. Discussion

In recent advancements in oncological treatment, cryoablation has emerged as a distinguished technique for addressing AMs [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Our single-center study contributes valuable insights into the efficacy and safety of CT-guided cryoablation for AMs. With 12 patients undergoing 13 procedures, we recorded a primary success rate of 91.7% and a secondary success rate of 100%, noteworthy when juxtaposed with existing literature.

CT- guided cryoablation’s efficacy and safety are evidenced by high technical success rates, rivaling those of established ablation methods such as radiofrequency and microwave [

1,

2,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The key to cryoablation's effectiveness is its robust capacity for tumor tissue destruction, evidenced by significant primary complete ablation rates. Its utility extends to scenarios where initial treatments leave residual tumors, as follow-up cryoablations have proven efficacious in supplementary interventions [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Comparative studies reveal success rates for cryoablation, radiofrequency, and microwave ablation for AMs ranging from 70.5% to 82% [

1,

2,

3,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

In a meta-analysis by Simon Pan et al. (2021), the efficacy and safety of image-guided percutaneous thermal ablation for AMs were evaluated. The study revealed a 1-year local control rate of 80% and a 1-year overall survival rate of 77%. It found that severe adverse events post-ablation occurred in 16.1% of cases, while low-grade adverse events were reported in 32.6%. Intraprocedural hypertensive crises were experienced by 21.9% of patients, mostly manageable with antihypertensive medications [

19].

In a study by Wei Zhang et al., CT-guided cryoablation for AMs was evaluated for feasibility, local control, and survival. Including 31 patients, the primary and secondary technical success rates were 90.3% and 100%.

The study found a 19.4% local progression rate, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year local progression-free survival (LPFS) rates at 80.6%, 37.8%, and 18.4%. Systemic progression-free survival (SPFS) rates were similar. Overall survival rates were 83.9%, 45.0%, and 30.0% over the same periods [

16].

In 2021 Hussein D. Aoun et al. assessed the technical feasibility and safety of percutaneous cryoablation for AMs on 34 patients. The local recurrence rate of 10% over 1.8 years. Recurrence was higher in tumors larger than 3 cm. Major complications occurred in 5% of cases, with one directly linked to the procedure. Blood pressure increases were more significant in patients with residual adrenal tissue, but manageable, especially with pre-treatment using alpha blockade [

17].

Our study aligns with these benchmarks, underscoring cryoablation's clinical efficacy, particularly in achieving high primary complete ablation rates.

An added benefit of cryoablation is its reduced risk of major complications, such as hypertensive crises, often associated with thermal ablation methods.

This aspect positions cryoablation as a potentially more favorable option for specific patient groups. In our study, minor complications, primarily mild blood pressure increases, were effectively managed, without any reports of severe hypertensive crises.

However, the retrospective design of our study may have introduced selection bias, and its single-center nature, coupled with a small patient cohort, limits the generalizability of the findings. Consequently, multi-center randomized controlled trials are imperative for a deeper understanding and broader application of cryoablation in AM treatment.

4. Conclusions

CT-guided cryoablation is safe and effective in treating AMs, equating to other ablation techniques in terms of technical success, local tumor control, and the handling of complications.

These findings support its consideration as a practical alternative in oncological treatments, given its versatility in addressing various cancer types and its efficacy in both localized and systemic disease management.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Oncological Hospital A. Businco, AOBrotzu-Cagliari, Italy (protocol code 03/22 Cagliari, 14 January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from author, C.P. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hasegawa T, Yamakado K, Nakatsuka A; et al. Unresectable adrenal metastases: clinical outcomes of radiofrequency ablation. Radiology 2015, 277, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenk NE, Daye D, Tuncali K; et al. Local control and survival after image-guided percutaneous ablation of adrenal metastases. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018, 29, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong H, Wang Z, Liu Y. Efficacy and Safety of Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Ablation for Adrenal Metastases: A Meta-Analysis. J Ultrasound Med. 2023, 42, 1779–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moinzadeh A, Gill IS. Laparoscopic radical adrenalectomy for malignancy in 31 patients. J Urol 2005, 173, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong VE, D’Angelica M, Tang L; et al. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for isolated adrenal metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol 2007, 14, 3392–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams HL, Spiro R, Goldstein N. Metastases in carcinoma; analysis of 1000 autopsied cases. Cancer 1950, 3, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunjur A, Duong C, Ball D; et al. Surgical and ablative therapies for the management of adrenal ‘oligometastases:’ a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2014, 40, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth A, Persson F, Jansson S; et al. Prognostic factors for survival after surgery for adrenal metastasis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010, 36, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell GM, Carty SE, Armstrong MJ; et al. Outcome and prognostic factors after adrenalectomy for patients with distant adrenal metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol 2013, 11, 3491–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez BJ, Richards ML, Lohse CM; et al. Adrenalectomy improves outcomes of selected patients with metastatic carcinoma. World J Surg 2012, 36, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno P, de laQuintana Basarrate A, Musholt TJ; et al. Adrenalectomy for solid tumor metastases: results of a multicenter European study. Surgery 2013, 154, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang HJ, Littrup PJ, Goodrich DJ; et al. Percutaneous cryoablation of metastatic renal cell carcinoma for local tumor control: feasibility, outcomes, and estimated cost-effectiveness for palliation. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012, 23, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong G, Bai W, Dong Z; et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous cryoablation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma within Milan criteria. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0123065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun L, Zhang W, Liu H; et al. Computed tomography imagingguided percutaneous argon-helium cryoablation of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Initial experience in 32 patients. Cryobiology 2014, 69, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch BT, Atwell TD, Nichols DA; et al. Percutaneous image-guided adrenal cryoablation: procedural considerations and technical success. Radiology 2011, 258, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang W, Sun LJ, Xu J. Computed tomography-guided cryoablation for adrenal metastases: local control and survival. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e13885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun HD, Littrup PJ, Nahab B. Percutaneous cryoablation of adrenal metastases: technical feasibility and safety. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021, 46, 2805–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch BT, Atwell TD, Nichols DA. Percutaneous image-guided adrenal cryoablation: procedural considerations and technical success. Radiology 2011, 258, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan S, Baal JD, Chen WC. Image-Guided Percutaneous Ablation of Adrenal Metastases: A Meta-Analysis of Efficacy and Safety. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021, 32, 527–535.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage AA, Baust JM, Baust JG. Experimental cryosurgery investigations in vivo. Cryobiology 2009, 59, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).