5.1. Development of ANFIS model

The ANFIS model shown and described below was developed in the Python programming language, in the PyCharm 2023.2.1 editor. (Community Edition, Jet Brains) which is open user access.

ANFIS systems represent a synergy of artificial neural networks and fuzzy logic (fuzzy inference system). The advantage of these systems is reflected in the combination of using their positive features, namely the ability to learn with artificial neural networks and the use of expert knowledge with fuzzy logic.

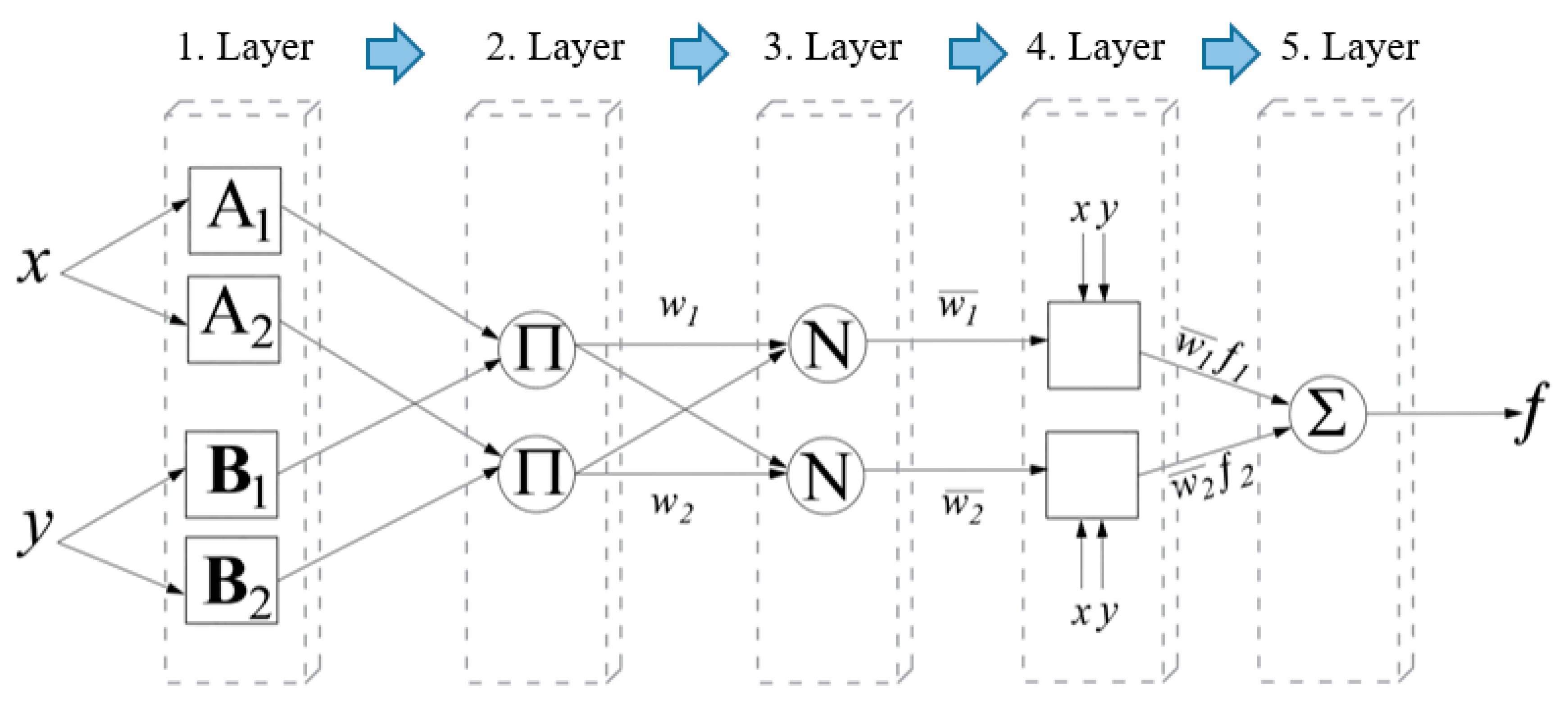

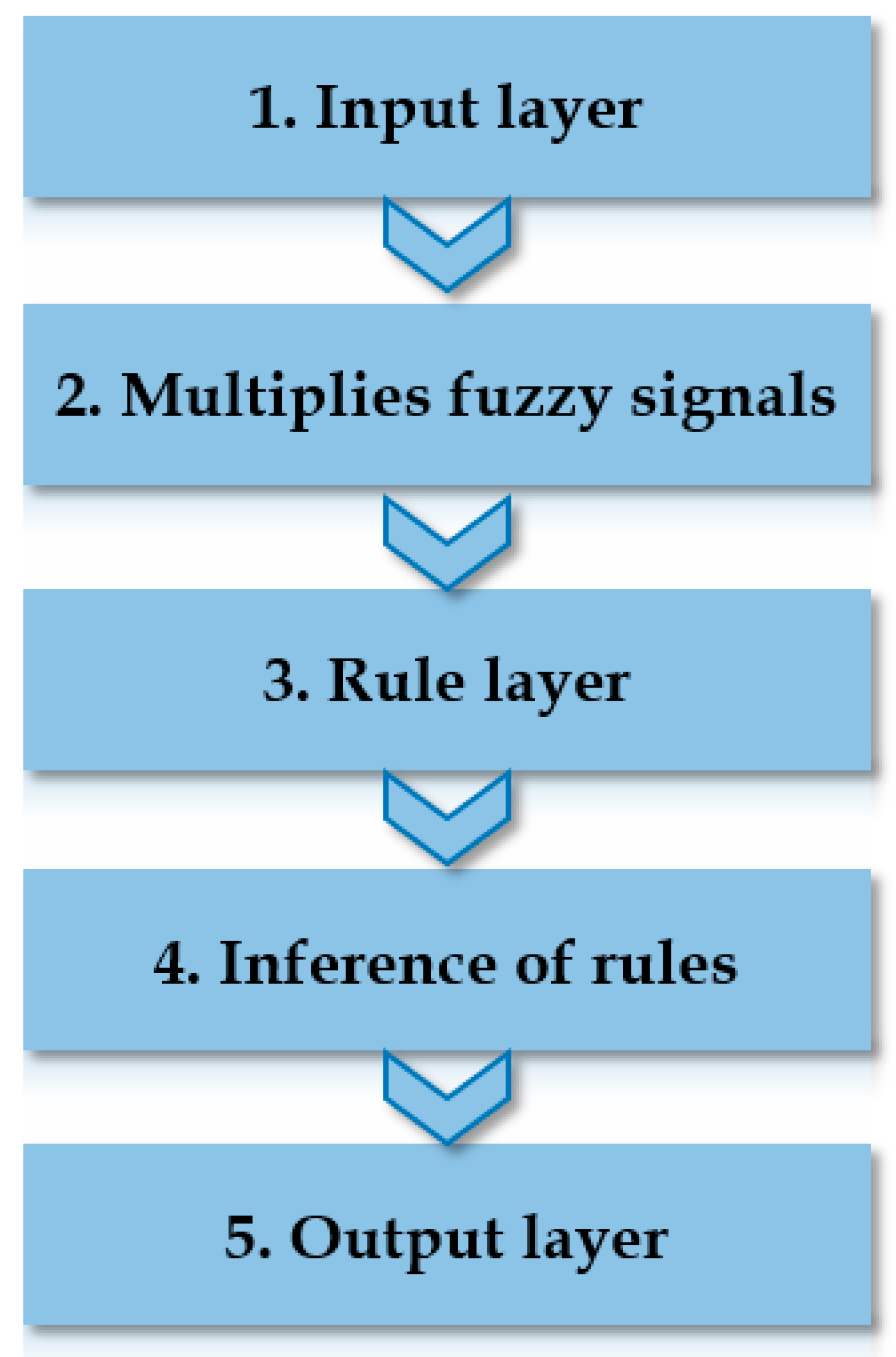

The structure of the ANFIS system is similar to the structure of artificial neural networks, where based on the input-output set of data, a corresponding fuzzy inference system is formed and the parameters of the membership functions that transform the input data are calculated. The general structure of the ANFIS model consists of five layers (

Figure 3). Below is a brief description of the layers.

In the first layer, the input data is transformed into a system of appropriate fuzzy sets. Accordingly, the output data of the first layer is determined by:

where

is the input argument of the first layer, and

is the membership function of the corresponding linguistic variable

.

The second layer of the ANFIS model combines the output arguments of the different variables of the previous layer. The output data is determined by:

where

and

are two different variables.

The next layer includes the process of normalization of the values obtained in the second layer. The normalization process is carried out as follows:

The next layer is a layer that combines normalized values from the previous layer and first-order polynomials:

where

,

and

are the parameters of the fourth layer model.

In the last layer, the normalized values of the previous layer are added using the following formula:

In

Figure 4. the general architecture of the ANFIS model described in the previous part is shown.

Training of a neuro-fuzzy system is best done by applying a back-propagation process that uses the

as the error function, which is defined by:

where

,

,…,

are actual values, and

,…,

are values predicted by the ANFIS model.

When the input membership function parameters are set, the output from the ANFIS model is calculated as follows:

Using

and

, the following equality is obtained:

The process of training, i.e., model training, is based on the determination of parameter values, adjusted according to the training data. Back-propagation method is the basic way of training the system. This algorithm tries to minimize the error between the network and the desired output.

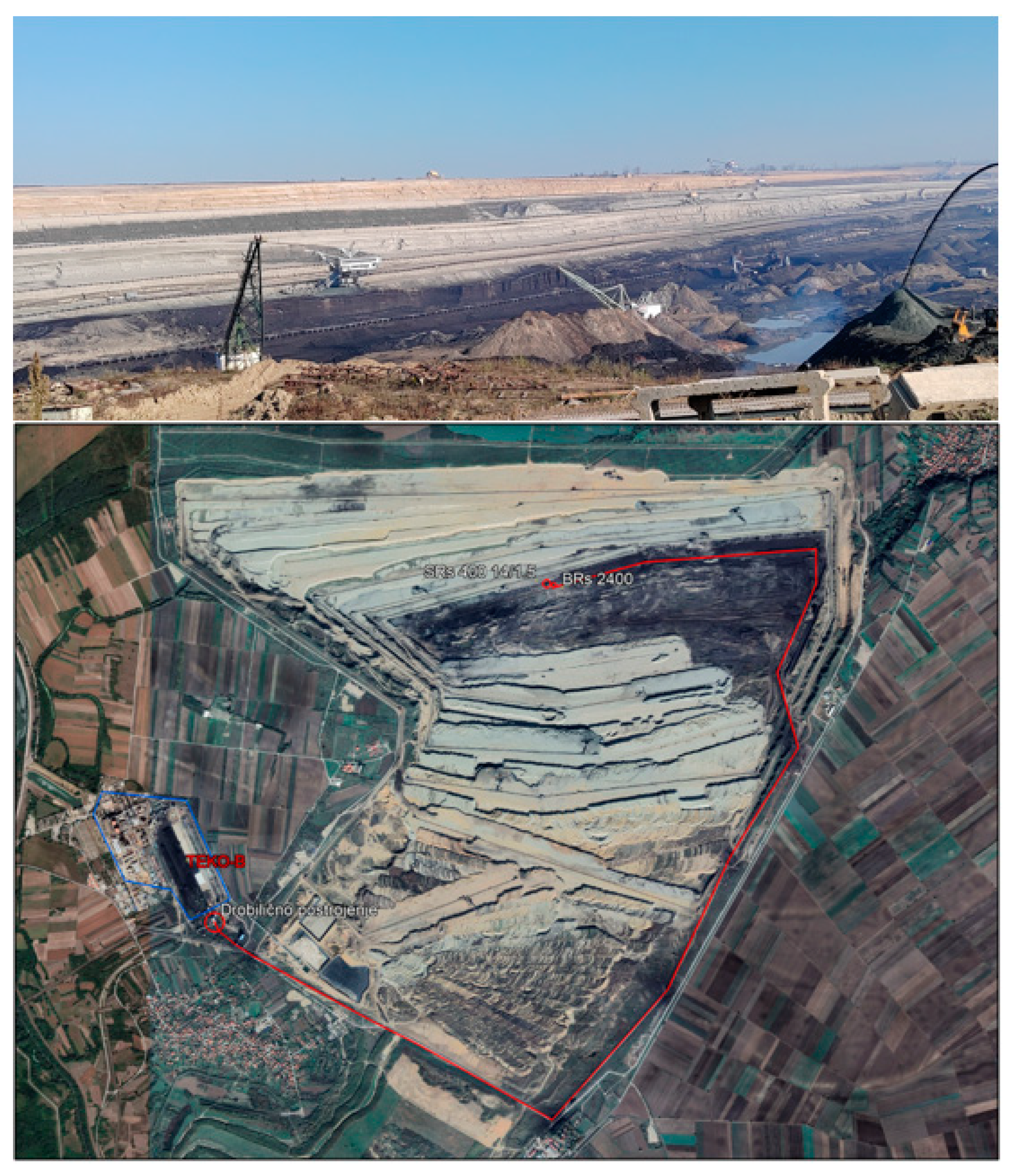

The determination of the availability of continuous systems and its partial indicators was processed through the results obtained through questionnaires related to the expert assessment of partial indicators of availability and to historical data on downtime and work, which include the time period from 2016 to 2019.

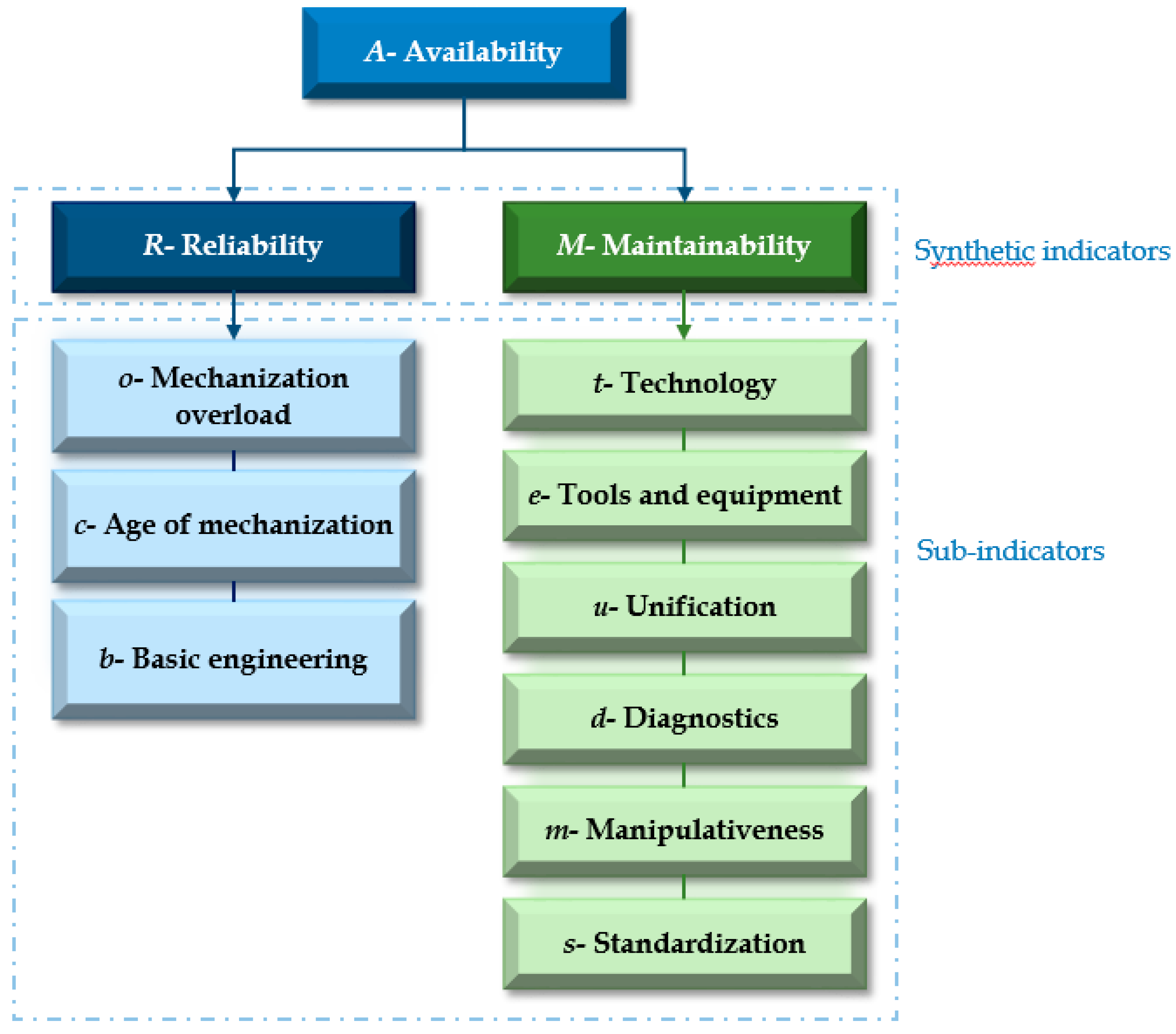

The availability of the ECC system is a function of the appropriate factors, which are most often divided into two groups - partial indicators, reliability and maintainability. These partial indicators (synthetic indicators) are further a function of a larger number of independent parameters (sub-indicators) that are considered as variables in this ANFIS model.

Figure 5.

Presentation of partial availability indicators [

5] (synthetic indicators, sub-indicators).

Figure 5.

Presentation of partial availability indicators [

5] (synthetic indicators, sub-indicators).

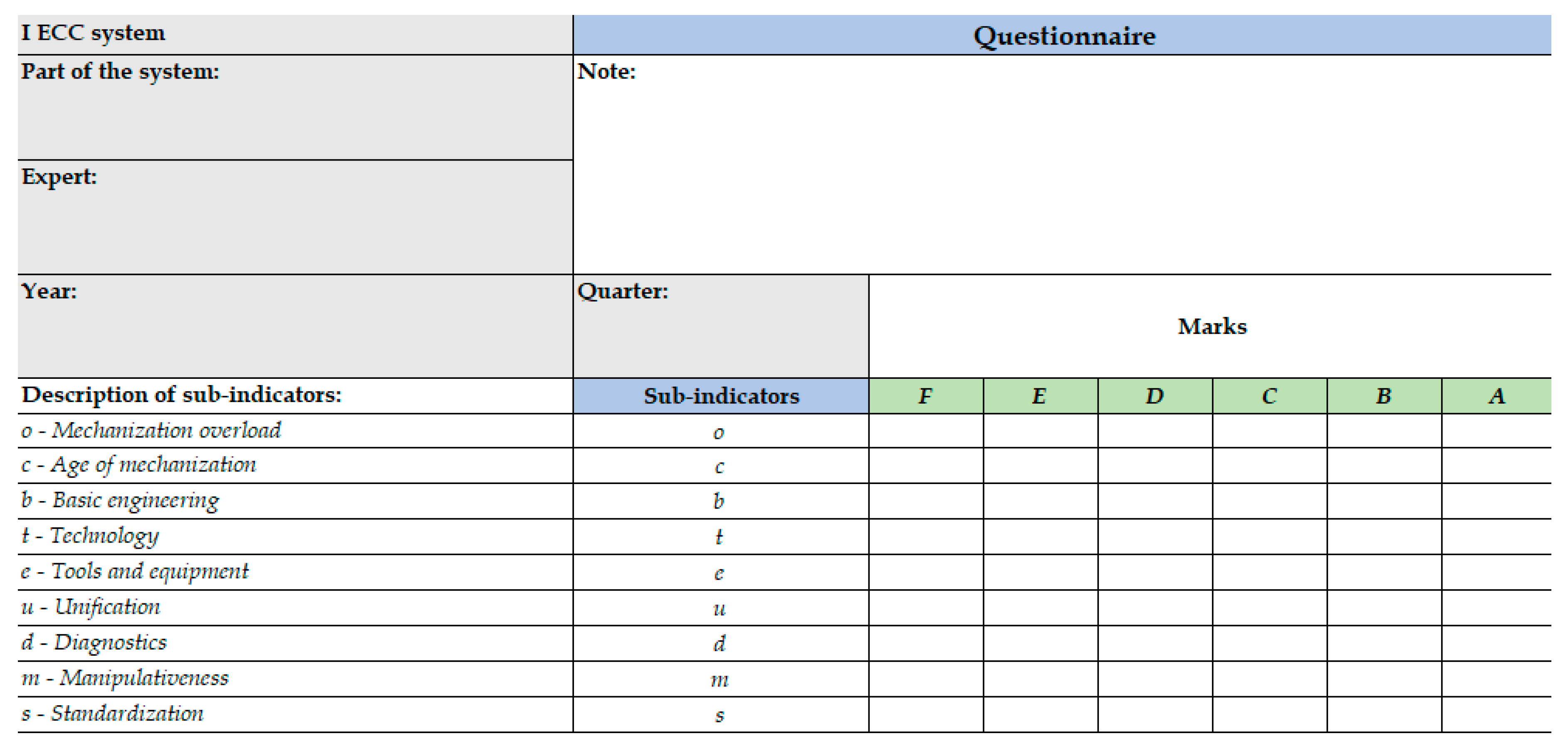

Within this model, availability decomposes into partial sub-indicators that are assessed by expert assessment, in the form of a questionnaire. Each part of the I ECC system (bucket wheel excavator, beltwagon, belt conveyors and crushing plant) is evaluated.

In the expert assessment, 10 experts from the field of continuous systems in surface exploitation were surveyed, who provided estimates for the sub-indicators of availability in a certain quarter and covering the period from 2016 to 2019 for each part of the ECC system. Data from 2016-2018 were used to train the ANFIS model (480 data - training data set), while data from 2019 (160 data - test data set) were used to test the obtained model. The experts were offered grades in the questionnaire ranging from

(the worst grade) to

(the best grade). The layout of the questionnaire is shown in

Figure 6, with the fact that in this questionnaire the expert is required to make assessments at the quarterly level in a predetermined period of time for each part I of the ECC system. The scores obtained in this way were used as input data of this model.

Before creating the model, a database was created related to the duration of mechanical, electrical and other failures of the ECC system over a period of 4 years (2016, 2017, 2018, 2019). Data from this database is used to determine historical availability on a quarterly basis, and as such is used as output data of the ANFIS model. Availability per quarter was calculated based on the formula (1.).

In

Table 1. part of the database is shown. The data was taken from the Electric Power Company of Serbia and contained information about downtimes on the specific system in the specified time period.

Based on the available data, the availability of the system was determined quarterly and the obtained values are shown in

Table 2.

The resulting ANFIS model received the survey results for all 9 partial sub-indicators for each part of the I ECC system as input parameters, while the output represented the corresponding availability in the quarter to which the survey results refer, which was obtained based on historical data taken from the Electric Power Company of Serbia.

In the first step of the model, fuzzification was performed, which represents the transformation of partial indicator scores, using membership functions, into the corresponding -scale for =10. Predefined fuzzy sets are not used for probability functions, but membership functions are used instead, the parameters of which are estimated within the model training process. The membership functions used are Bell-shaped membership function, Gaussian membership function and Sigmoid membership function.

Using IF-THEN rules that are pre-defined, the synthetic indicator is determined based on the partial sub-indicators , , and the synthetic indicator is determined based on the partial sub-indicators , , , , , .

In the following, we will illustrate the determination of the synthesis indicator

using IF-THEN rules based on sub-indicators

,

,

. Let the IF-THEN rule be defined by IF

AND

AND

THEN

where i,j,k are in the set {

}, and

is in the set {

}. Then the fuzzy sets come together:

where

,

and

are the input values of grades

,

,

respectively for partial indicators

,

,

, assigns the value

. The fuzzy set corresponding to the rating

of the indicator

is the sum of all fuzzy sets assigned the value

. In a similar way, on the basis of sub-indicators

,

,

,

,

,

, the synthesis indicator

is calculated.

In the next step, using the IF-THEN rules, as described in the previous paragraph, the availability indicator

is determined by synthetic indicators

and

. Then, the Euclidean distance of the obtained fuzzy sets from the fuzzy sets assigned to the availability indicator

is determined based on the corresponding membership functions whose parameters we estimate within this ANFIS model. The distances

,

,

,

and

determined in this way can be joined by the normalized reciprocal values of the relative distances determined by:

These values represent belonging to the appropriate set of grades that determine the indicator of availability, i.e.,

Finally, the linguistic description is transformed into a numerical designation:

Dividing by 5 gives the predicted value of availability, which is compared with the realized value of availability calculated on a quarterly basis.

The IF-THEN rules used in this ANFIS model are shown in the following tables. So, for example, the values shown in the first type of this table are interpreted as follows:

If the partial sub-indicator is (the conditions of the working environment are such that the engaged equipment generally does not meet them) and if the partial sub-indicator is (write-off machine, very high level of failure) and if the partial sub-indicator is (underdeveloped basic engineering) then indicator is unreliable .

Table 3.

IF-THEN rules for determining the indicator - reliability

Table 3.

IF-THEN rules for determining the indicator - reliability

|

|

|

|

| F |

F |

F |

E |

| E |

E |

E |

D |

| D |

D |

D |

C |

| C |

C |

C |

B |

| B |

B |

B |

A |

| B |

C |

B |

A |

| C |

B |

C |

B |

| C |

B |

B |

A |

| B |

C |

D |

B |

| C |

C |

B |

B |

| D |

C |

D |

C |

| E |

B |

E |

C |

| C |

D |

B |

A |

| E |

E |

D |

D |

| C |

C |

A |

A |

| D |

C |

B |

B |

| B |

B |

A |

A |

| B |

C |

D |

B |

| A |

B |

A |

A |

| D |

B |

B |

A |

| D |

E |

A |

B |

| A |

C |

C |

A |

| A |

C |

D |

B |

| A |

B |

B |

A |

| A |

E |

D |

B |

| A |

B |

C |

A |

| B |

C |

E |

B |

| B |

D |

D |

B |

| B |

E |

E |

C |

| B |

B |

A |

A |

| A |

A |

A |

A |

| F |

E |

E |

D |

| F |

D |

D |

C |

| F |

C |

C |

B |

| F |

A |

A |

A |

| F |

E |

D |

D |

| E |

D |

C |

C |

| D |

C |

B |

B |

| C |

B |

A |

A |

Table 4.

IF-THEN rules for determining the indicator – maintainability

Table 4.

IF-THEN rules for determining the indicator – maintainability

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| F |

F |

F |

F |

F |

F |

E |

| E |

E |

E |

E |

E |

E |

D |

| D |

C |

C |

C |

B |

B |

B |

| D |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

B |

| D |

C |

A |

C |

B |

B |

A |

| C |

B |

B |

B |

C |

B |

A |

| B |

C |

B |

B |

B |

B |

A |

| B |

D |

D |

C |

C |

C |

B |

| C |

C |

D |

B |

B |

B |

B |

| D |

C |

D |

C |

D |

B |

B |

| E |

D |

C |

B |

B |

C |

B |

| C |

B |

B |

B |

B |

B |

A |

| B |

D |

C |

C |

B |

B |

B |

| C |

C |

B |

B |

D |

C |

B |

| B |

B |

B |

B |

B |

A |

A |

| B |

A |

C |

C |

C |

B |

A |

| C |

C |

B |

C |

B |

B |

A |

| C |

C |

C |

C |

B |

B |

B |

| C |

D |

C |

C |

D |

C |

B |

| C |

C |

B |

B |

C |

D |

B |

| C |

A |

B |

C |

D |

C |

B |

| B |

C |

D |

D |

D |

B |

B |

| D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

C |

| C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

B |

| B |

B |

B |

B |

B |

B |

A |

| A |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A |

| E |

E |

E |

D |

D |

D |

C |

| D |

D |

D |

C |

C |

C |

B |

| C |

C |

C |

B |

B |

B |

A |

| B |

B |

B |

A |

A |

A |

A |

| F |

E |

D |

C |

B |

A |

B |

| E |

E |

D |

C |

B |

A |

B |

| D |

E |

D |

C |

B |

A |

B |

| C |

E |

D |

C |

B |

A |

B |

| B |

E |

D |

C |

B |

A |

A |

| A |

E |

D |

C |

B |

A |

A |

Table 5.

IF-THEN rules for determining - availability

Table 5.

IF-THEN rules for determining - availability

|

|

|

| D |

D |

D |

| D |

C |

C |

| D |

B |

C |

| D |

A |

B |

| C |

D |

C |

| B |

D |

C |

| C |

C |

C |

| B |

B |

B |

| A |

A |

A |

| E |

D |

D |

| C |

B |

B |

| B |

A |

A |

| C |

A |

B |

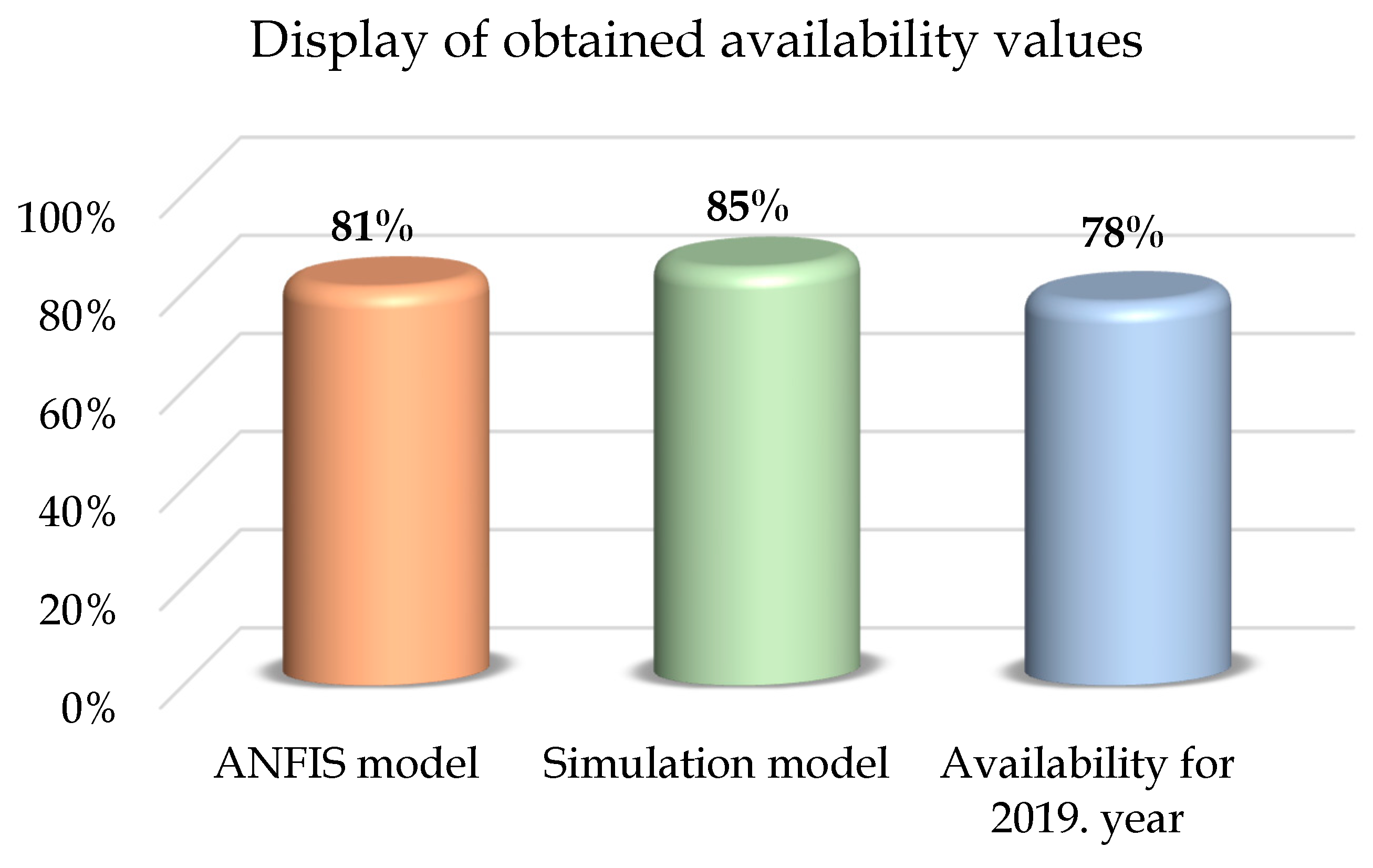

A summary of the considered models for predicting availability is given in

Table 6.

5.2. Development of Simulation model

During the creation of the simulation model, all failures were classified into one of three types of failure (mechanical, electrical, and others). As in the case of the ANFIS model, the simulation model was developed based on data from three years (2016., 2017. and 2018. year).

In

Table 7. experimental and theoretical frequencies of machine failures by intervals are given.

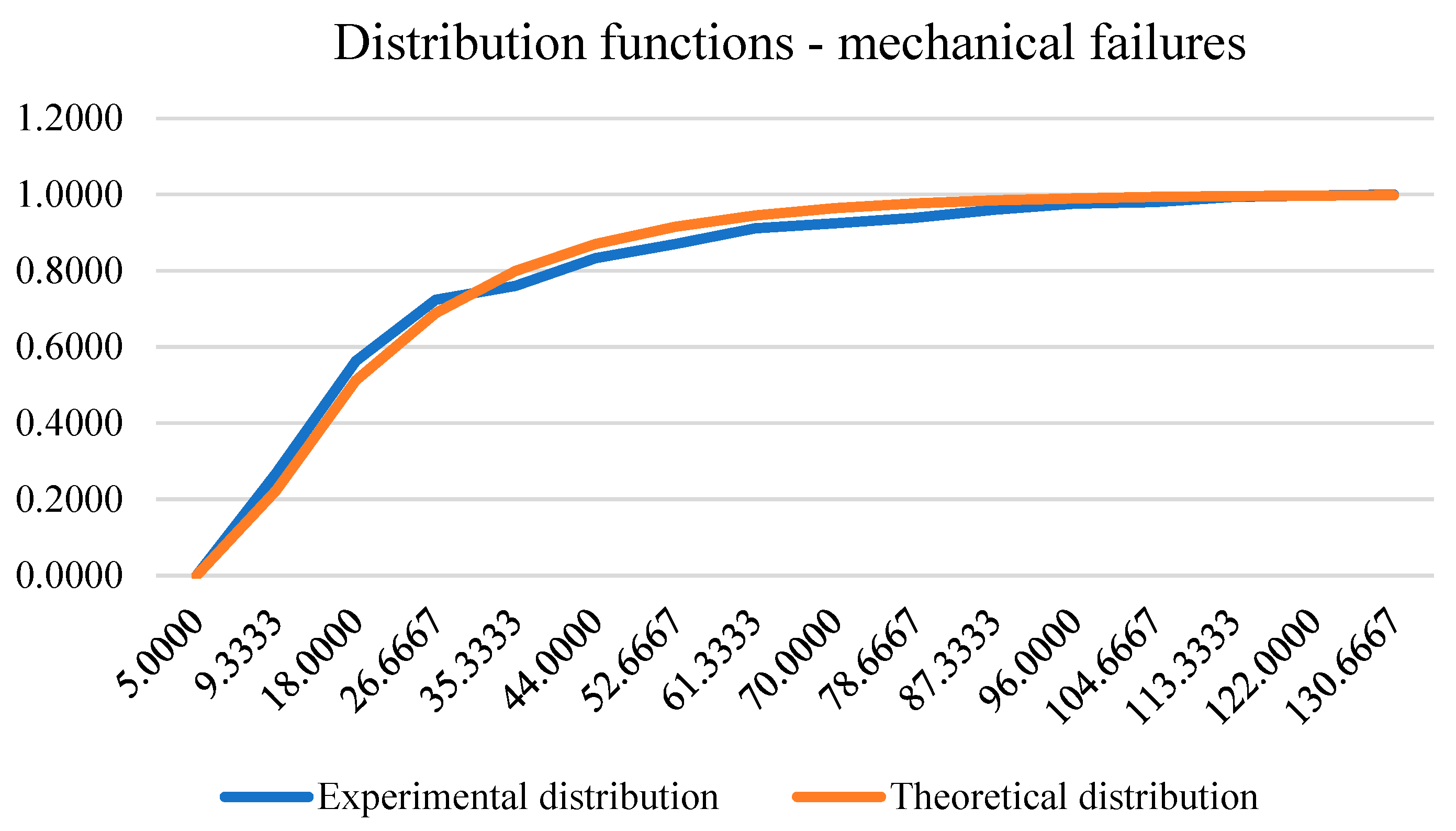

The distribution of mechanical failure times, which was considered in the 96 percentile of the data, conforms to the Weibull distribution with parameters

,

i

. More precisely, the empirical distribution function is determined by:

The number of mechanical failures on which this model was developed amounted to 1238 failures. The testing of the hypothesis about the distribution of data was performed with the help of the Kolmogornov-Smirnov test whose statistic value is equal to 1.7944, so with a significance level of 0.001 we cannot reject the null hypothesis that claims that the data are in accordance with the Weibull distribution. The following figure shows the experimental and theoretical function of the distribution of mechanical failures.

Figure 7.

Experimental and theoretical distribution function of mechanical failures.

Figure 7.

Experimental and theoretical distribution function of mechanical failures.

In

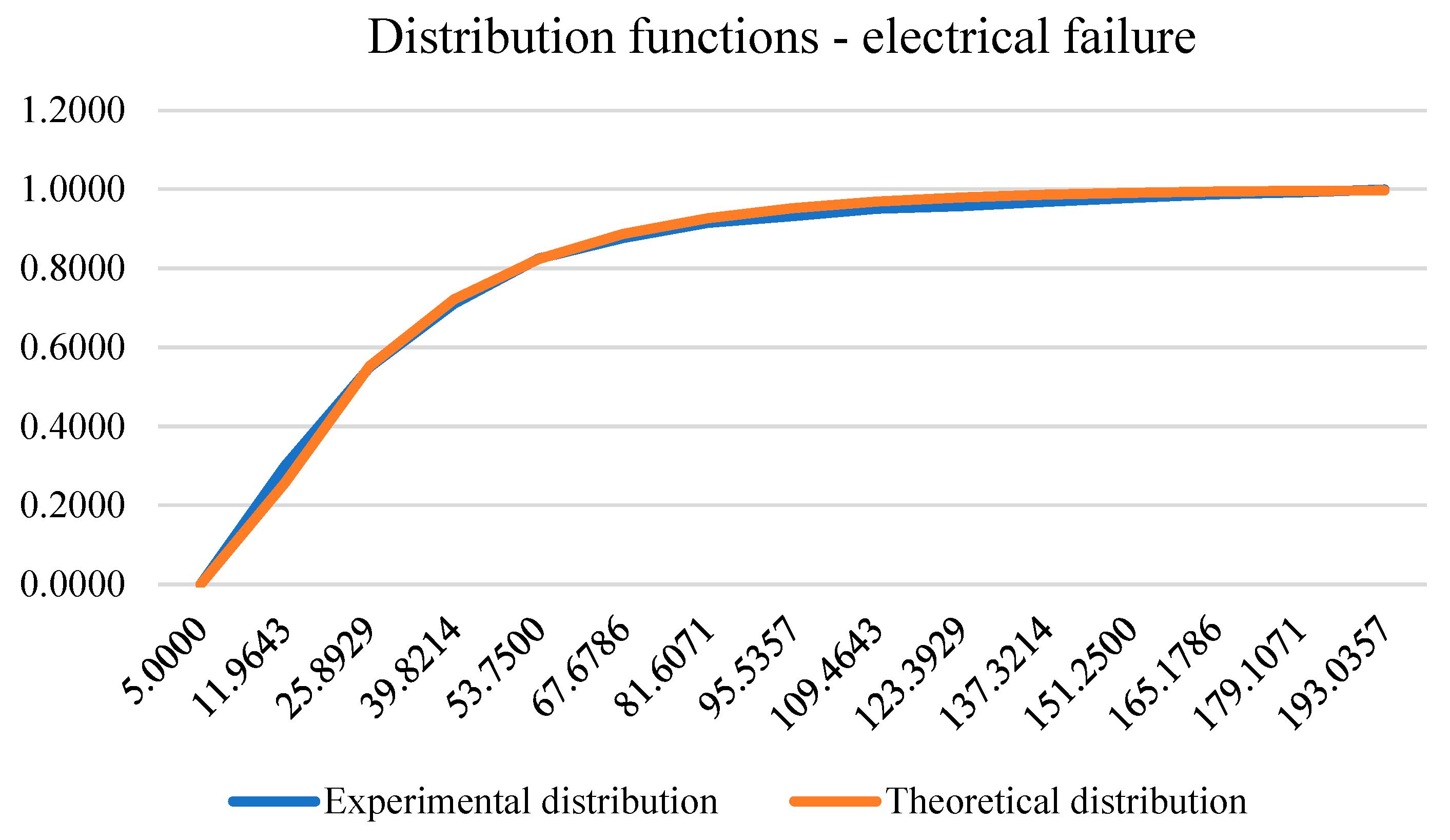

Table 8. experimental and theoretical frequencies of electrical failures by intervals are given.

The distribution of the duration of electrical failure, which was considered in the 98.5 percentile of the data, is in accordance with the Weibull distribution with parameters

,

and

. More precisely, the empirical distribution function is determined by:

The number of electrical failures on which this model was developed amounted to 908 failures. Testing of the hypothesis about data distribution was performed with the help of the Kolmogornov-Smirnov test whose statistic value is equal to 1.2804, so with a significance level of 0.05 we cannot reject the null hypothesis which claims that the data are in accordance with the Weibull distribution. The following figure shows the experimental and theoretical distribution function of electrical failure.

Figure 8.

Experimental and theoretical distribution function of electrical failure.

Figure 8.

Experimental and theoretical distribution function of electrical failure.

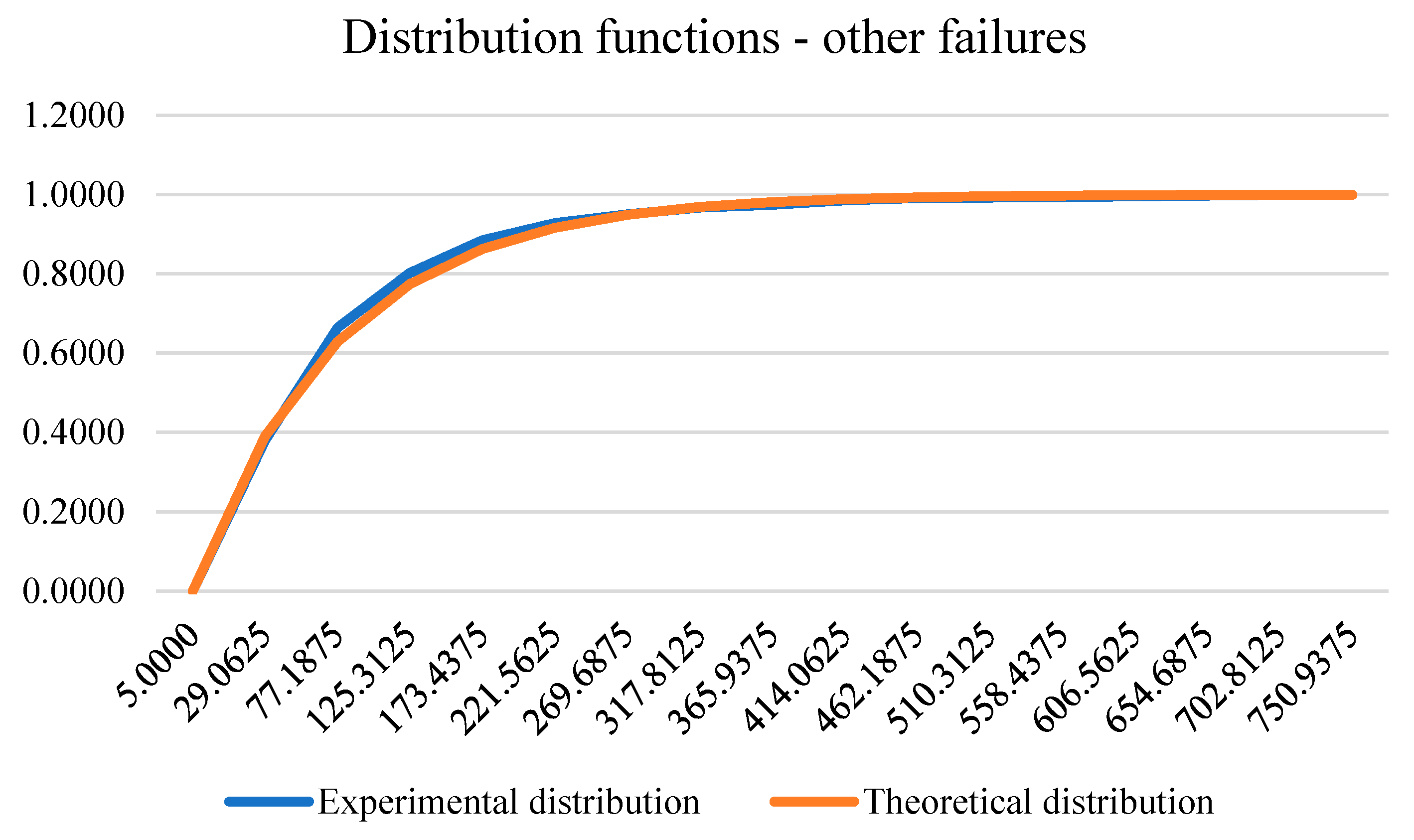

In

Table 9. experimental and theoretical frequencies of other failures by intervals are given.

Table 9.

Experimental and theoretical frequency of other failures by intervals.

Table 9.

Experimental and theoretical frequency of other failures by intervals.

| No. |

The lower bound of the interval |

The upper bound of the interval |

Experimental pdf |

Experimental cdf |

Theoretical pdf |

Theoretical cdf |

KS test |

| 1 |

5 |

53 |

0.3803 |

0.3803 |

0.3910 |

0.3910 |

0.0107 |

| 2 |

53 |

101 |

0.2837 |

0.6640 |

0.2381 |

0.6291 |

0.0350 |

| 3 |

101 |

149 |

0.1384 |

0.8025 |

0.1450 |

0.7741 |

0.0284 |

| 4 |

149 |

198 |

0.0823 |

0.8847 |

0.0883 |

0.8624 |

0.0223 |

| 5 |

198 |

246 |

0.0433 |

0.9281 |

0.0538 |

0.9162 |

0.0119 |

| 6 |

246 |

294 |

0.0217 |

0.9498 |

0.0328 |

0.9490 |

0.0008 |

| 7 |

294 |

342 |

0.0172 |

0.9670 |

0.0200 |

0.9689 |

0.0019 |

| 8 |

342 |

390 |

0.0069 |

0.9739 |

0.0122 |

0.9811 |

0.0072 |

| 9 |

390 |

438 |

0.0113 |

0.9852 |

0.0074 |

0.9885 |

0.0032 |

| 10 |

438 |

486 |

0.0054 |

0.9906 |

0.0045 |

0.9930 |

0.0023 |

| 11 |

486 |

534 |

0.0015 |

0.9921 |

0.0027 |

0.9957 |

0.0036 |

| 12 |

534 |

583 |

0.0015 |

0.9936 |

0.0017 |

0.9974 |

0.0038 |

| 13 |

583 |

631 |

0.0015 |

0.9951 |

0.0010 |

0.9984 |

0.0033 |

| 14 |

631 |

679 |

0.0020 |

0.9970 |

0.0006 |

0.9990 |

0.0020 |

| 15 |

679 |

727 |

0.0020 |

0.9990 |

0.0004 |

0.9994 |

0.0004 |

| 16 |

727 |

775 |

0.0010 |

1.0000 |

0.0002 |

0.9996 |

0.0004 |

The distribution of the duration of other failures, which was considered in the 100 percentile of the data, is in accordance with the exponential distribution with parameters

,

. More precisely, the empirical distribution function is determined by:

The number of other failures on which this model was developed amounted to 2030 failures. The testing of the hypothesis about the data distribution was performed with the help of the Kolmogornov-Smirnov test whose value of the statistic is equal to 1.5761, so with a significance level of 0.01 we cannot reject the null hypothesis which claims that the data are in accordance with the exponential distribution. The following figure shows the experimental and theoretical distribution function of other failures.

Figure 9.

Experimental and theoretical distribution function of other failures.

Figure 9.

Experimental and theoretical distribution function of other failures.

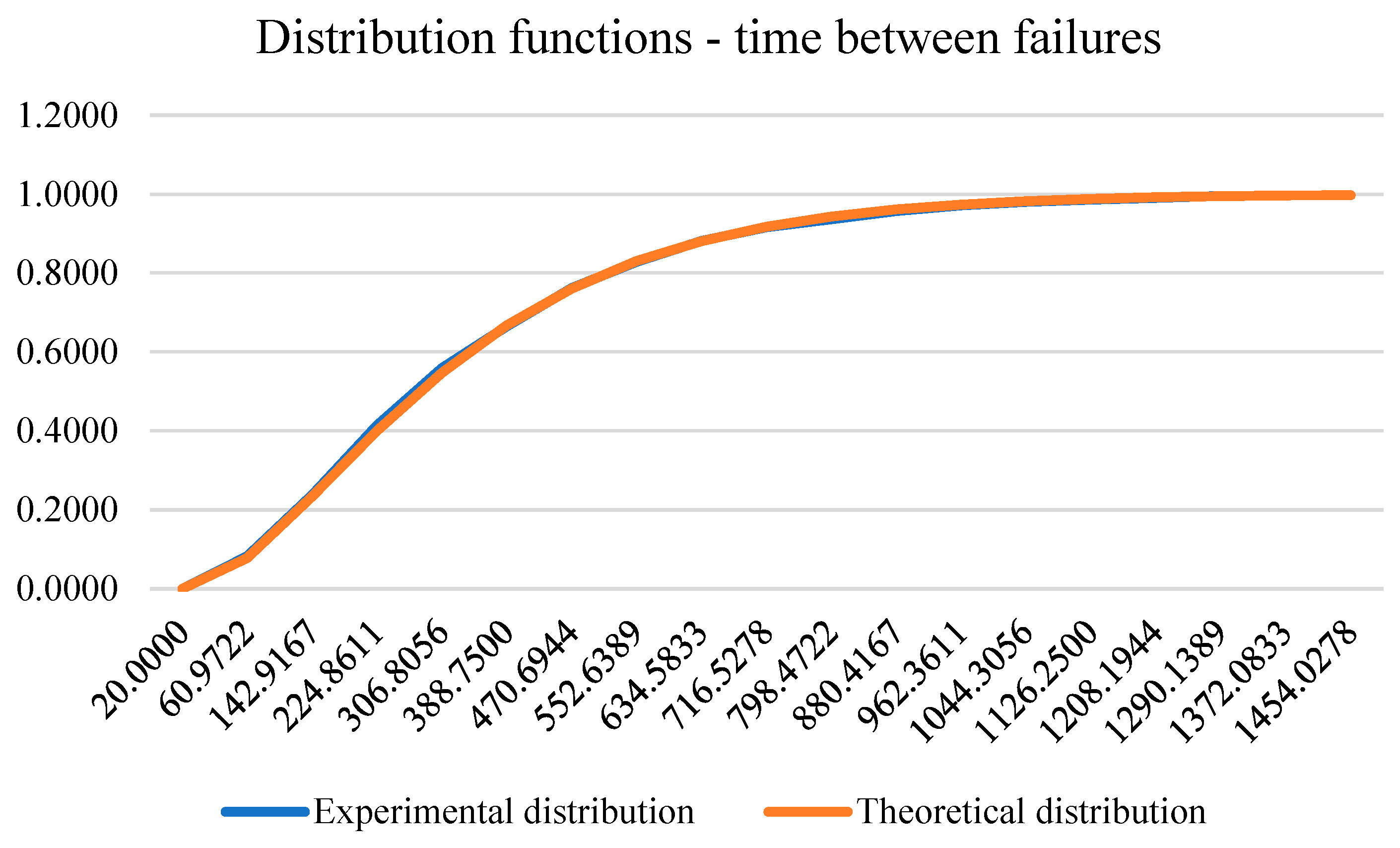

In

Table 10. the presentation of experimental and theoretical frequencies of duration between failures by intervals is given.

The distribution of the duration between failures, which was considered in the 95 percentile of the data, is in accordance with the Erlang distribution with parameters

,

and

. More precisely, the empirical distribution function is determined by:

The number of times between failures on which this model was developed was 5212. The testing of the hypothesis about the distribution of data was carried out with the help of the Kolmogornov-Smirnov test whose value of the statistic is equal to 1.0192, so with a significance level of 0.2 we cannot reject the null hypothesis that claims that are data in accordance with the Erlang distribution. The following figure shows the experimental and theoretical time distribution function between failures.

Figure 10.

Experimental and theoretical time distribution function between failures.

Figure 10.

Experimental and theoretical time distribution function between failures.

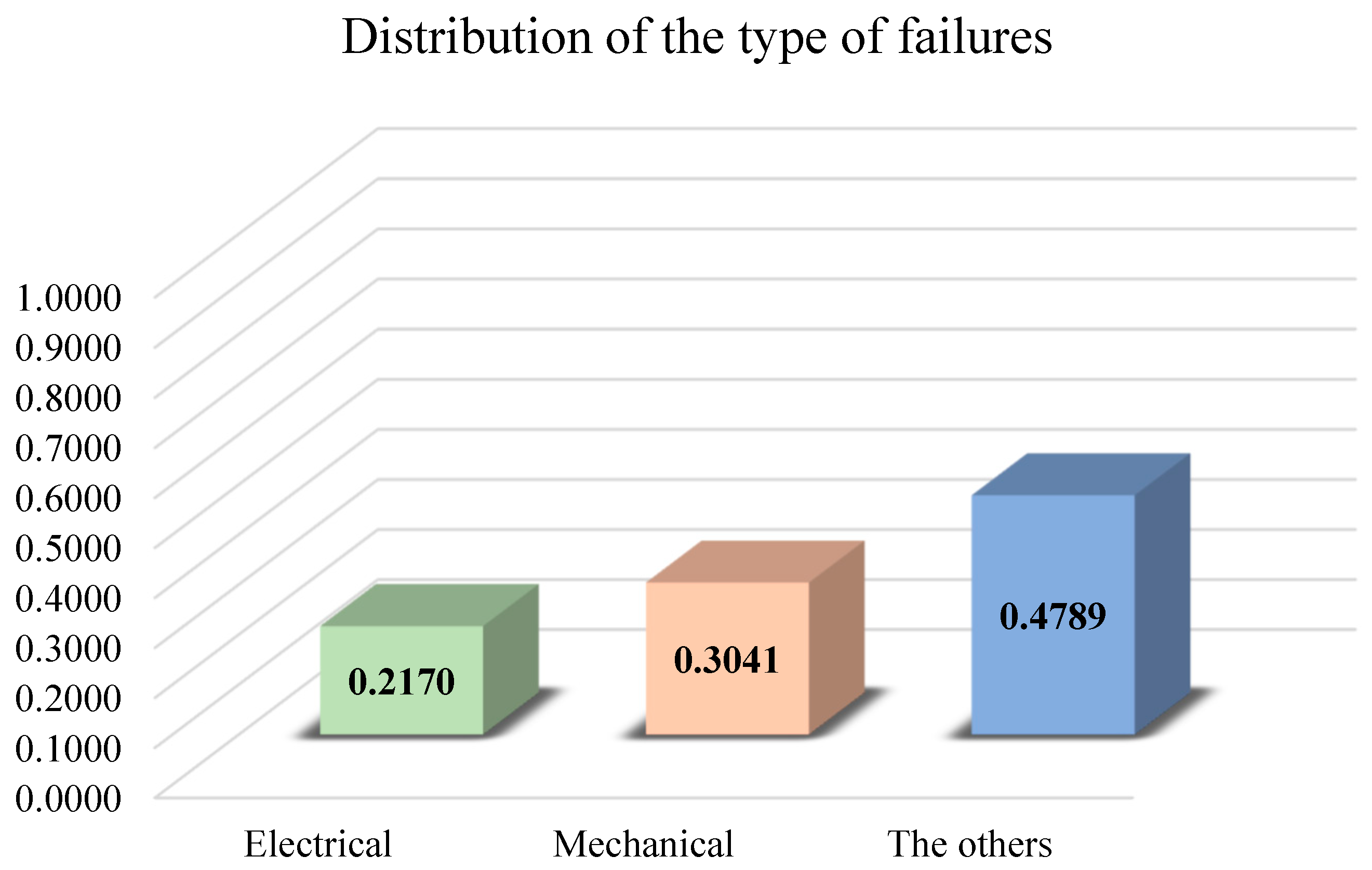

The following figure shows the frequency distributions of the considered failure types.

Figure 11.

Frequency distribution of the considered failure types.

Figure 11.

Frequency distribution of the considered failure types.

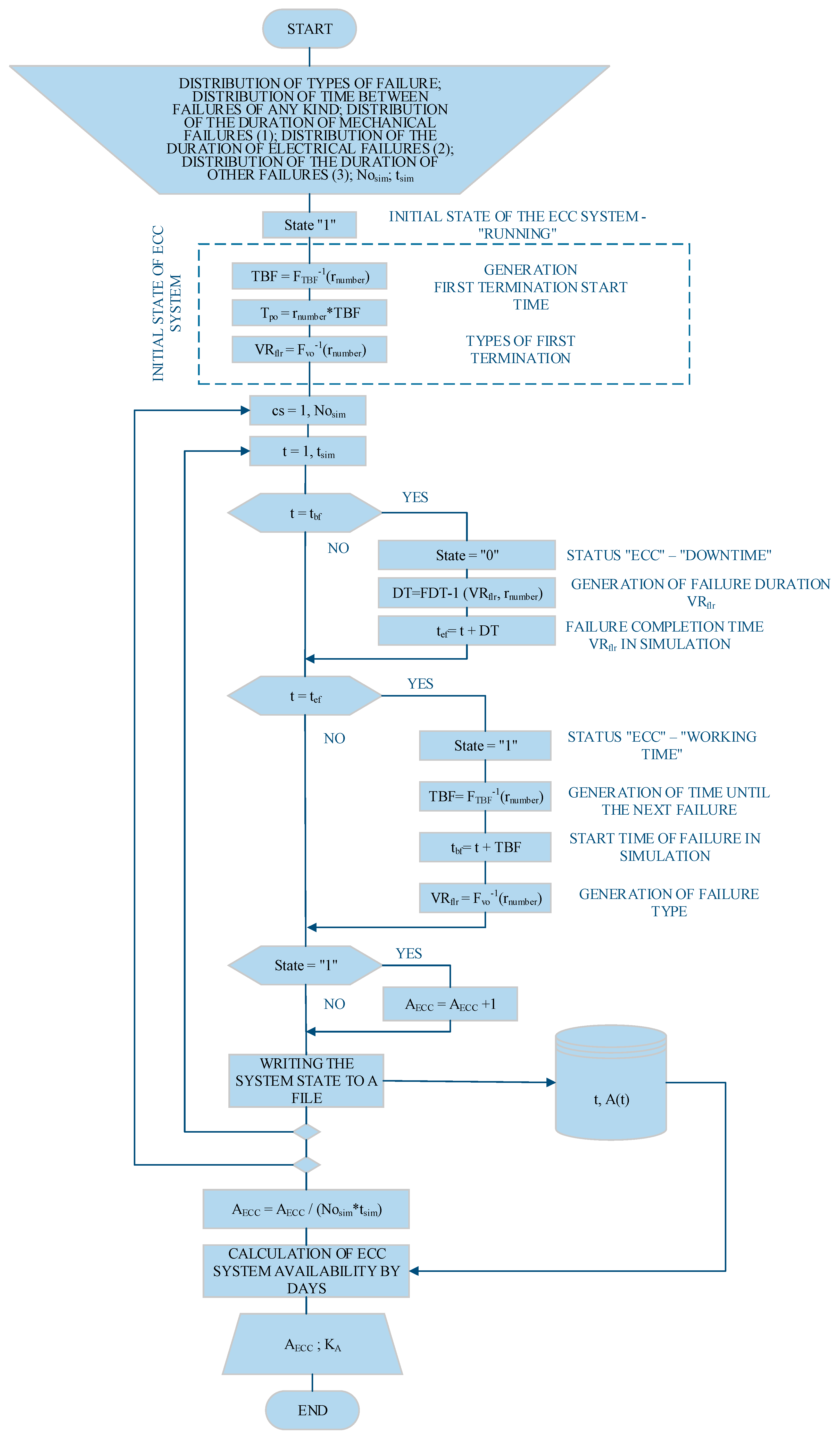

The simulation model, whose algorithm is shown in the following figure (

Figure 12), based on a randomly selected number from the distribution of the type of failure, generates a type of failure, and based on the next randomly selected number, the length of the failure of the selected type of failure is generated based on the distribution functions described above. Then, based on the new randomly selected number and the time-between-failure distribution function, the duration between failures is generated.

Glossary

tsim – duration of the simulation (s),

Nosim – number of simulations,

State – state ECC system: 1 – „working time“; 0 – „downtime“,

rnumber – random number generated by uniform distribution in the interval [0...1],

cs- current simulation,

tsim – simulation time,

TBF – time between failures (current),

DT – downtime failures (current),

tef – failure completion time (in simulation),

tbf – failure start time (in simulation),

VRflr – type of failure: 1 - mechanical; 2 – electrical; 3- other,

AECC – system availability - ECC,

A (t) – availability of the system at a given time t,

ka – stationary availability value.