1. Introduction

According to the recent report released by World Health Organization in 2023, tuberculosis (TB) is the second leading cause of death from a single infective agent (after SARS CoV-2), accounting for more than 10 million cases and around 1,3 million death in the world in 2022 [

1]. To stop the global TB epidemic, in 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) defined the “End TB Strategy”, underlining the need to develop diagnostic methods, as well as improve treatment and prevention strategies, to ensure an earlier and correct diagnosis [

2]. Worldwide TB has different epidemiology: low and middle-income countries, such as sub-Saharan African and South-East Asian regions, are affected with the highest rates of infection (“high burden countries”); conversely high-income countries show lower incidence (“low burden countries”). In high burden TB countries, which accounted for 88% of cases worldwide, TB is still a common disease, often undiagnosed for lack of diagnostic tool. On the other hand, in low burden TB countries (e.g. Italy accounting for 4000 cases in 2020), the diagnostic tools are available but the poor incidence leads to misdiagnosis and delay in treatment and contact tracing [

3]. Pulmonary tuberculosis frequently manifests parenchymal cavitation in 40-87% of cases. Cavitations are detectable in most relapses and treatment failures, most cases of multi-drug resistance (MDR) and nearly all cases of extensively drug-resistant TB [

4,

5]. Patients with lung cavitations are contagious and have a bacterial load greater than subjects without cavitations [

5,

6]. Computed Tomography (CT) is the gold standard of imaging diagnosis of TB, because of its higher sensitivity than chest x-ray (CXR) in the detection and characterization of pulmonary findings [

7,

8]. However, both CT and CXR have several disadvantages. The main limitations are represented by ionizing radiation exposure, poor access to high-quality radiologic equipment, limited access in rural areas and prohibitive costs for patients’ diagnosis. Nowadays, lung ultrasound (LUS) is considered a valid tool in the diagnosis of many lung pathologies and is mainly a safe, portable and cost-effective imaging modality [

9,

10,

11,

12]. With LUS it is possible to identify an interstitial syndrome characterized by a smooth thickening of the interlobular septa (represented as an increase of the B-lines) and areas of partial alveolar fillings, the so-called “white lung” corresponding to the ground glass opacities that can be highlighted in Computed Tomography [

9,

10]. Moreover, is it possible to detect alveolar consolidations as area of hepatization with a dynamic air-bronchogram or area of atelectasis or pneumonia in patients with a static air-bronchogram [

8,

11]. We previously described the role of LUS in pulmonary TB in the work “Lung ultrasound (LUS) in pulmonary tuberculosis: correlation with chest Computed Tomography and X-ray findings” [

11]. We analyzed a population of patients with clinical/radiological/epidemiological suspicion of pulmonary TB who made access to the Emergency Department of our hospital between September 2017 and February 2020. Overall LUS sensitivity in detecting TB was 80%, greater for micronodules (82%) and nodules (95%), lower for consolidation with air bronchogram (72%) and cavitations (33%). Among the 82 patients enrolled, 48 presented cavitations at Computed Tomography (42 TB patients and 6 non-TB patients), with lower identification by X-ray and LUS [

11].

Based on the findings of our previous study, the present work aims to evaluate the potential of lung ultrasound in recognizing lung cavitations, compared with chest computed tomography and chest x-ray, to describe its main characteristics and diagnostic accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Patients selection

This prospective monocentric study was conducted in the period between September 2017 and February 2020 in our Florentine University Hospital. All patients were admitted with a clinical, radiological and epidemiological suspicion of pulmonary TB. They all performed LUS examinations within three days after the admission. Both chest CXR and CT exams were performed at admission to the Radiology Emergency Department in the same institute

2.2. TB diagnosis and Imaging

The diagnosis of pulmonary TB was based on clinical findings (dyspnea, fever, weight loss, persistent cough), computed tomography and chest X-ray scan images suggestive of pulmonary TB and bacteriological confirmation. Depending on clinical features, we collected sputum, broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL), pleural liquid or trans bronchial biopsy (TBNA) for microbiological analysis. All CT scans were obtained using a multidetector 128-slice CT (Brilliance 128 iCT SP, Philips Medical System). Patients were scanned in a supine position with cranio-caudal acquisition and suspended breath. Technical parameters were: slice thickness 1 mm, reconstruction filter B70 lung, KV 120, DoseRight-Index 19, Pitch 1,4. All chest X-ray scans were obtained as digital radiographs in the X-Ray room (Digital Diagnost 4.1.x, Philips Medical System) or with the same portable X-Ray unit (FDR Go PLUS-Fujifilm, Italia). Only a small number of patients were scanned with two projections (postero-anterior PA and later lateral); most were scanned in a supine position with an antero-posterior (AP) projection, so we decided not to evaluate the lateral view for all patients. An echographic examination was performed by a thoracic expert radiologist, blinded about the patient’s radiological examinations and clinical status. The exam was conducted using an ESAOTE model (MyLab Class C Advance) with a 5 - 3.5 MHz convex probe, or 7.5 MHz linear probe. Patients were examined both in a seated and in a supine position. Examinations were performed by taking longitudinal scans starting anteriorly from the parasternal zone and posteriorly from the paravertebral/posterior axillary lines to analyze every intercostal space. The examination of lung apexes was performed by applying the probe vertically between the clavicle and the trapezius muscle anteriorly. The whole surface of the chest was thus analyzed. The radiologist filled out a predefined form where the localization of the cavitations was outlined. Each marker was localized apical, middle or inferior, anterior or posterior, left and right with the same approach as explained in our previous work [

11]. At CXR we weren’t able to evaluate anterior and posterior regions with only AP or PA projections, so we localized CXR without considering Anterior and Posterior.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA/MP (version 14 STATA Corp. College Station, TX). Epidemiological, clinical and demographic features were analyzed by adequate descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were expressed with median and interquartile range, categorical variables as proportions. Differences between groups were assayed using the Wilcoxon Ranks Test or Chi Square Test. The diagnostic accuracy of cavitations’ detection was assessed and sensitivity of LUS and CXR versus CT (gold standard) was calculated.

3. Results

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (ref. CEAVC 14816). Eighty-two patients with suspicion of pulmonary TB were enrolled in this study (51 males, 31 females; median age 48 years old). In 58 patients, laboratory examinations confirmed the diagnosis of pulmonary TB with a disease prevalence of 71%. Epidemiological and anamnestic features of the patients in the study are shown in

Table 1 (

Table 1); instead differential diagnosis in non – pulmonary TB cases are described in

Table 2 (

Table 2).

Chest CT showed pathological cavitations in 38/82 patients (46.3%), of which 32/58 with pulmonary TB (55.2%) and 6/24 non-TB (25%); 11 of 32 pulmonary TB patients (34.3%) showed cavitations in multiple areas, the six non-tuberculous patients show cavitation in a single area (Upper Anterior, Upper Posterior, Middle Anterior, Middle Posterior, Inferior Anterior, Inferior Posterior, all to the right and left respectively) (Table 3). LUS showed pathological cavitations in only 15/82 patients (18.3%), of which 11/58 with pulmonary TB (19%) and 4/24 non-tuberculous (16.7%); only 1 pulmonary TB patient (7%) showed cavitations in multiple areas. Chest X-Ray showed pathological cavitations in 27/82 patients (33%), of which 23/58 with pulmonary TB (40%) and 4/24 non-tuberculous (16.7%); only 3 of 32 pulmonary TB patients (9.4%) showed cavitations in multiple areas, (Upper, Middle, Inferior all to the right and left respectively, without evaluation of anterior or posterior in the AP evaluation only). Non-TB patients with cavitations have bacterial pneumonia as a definitive diagnosis in 3 cases, in 2 cases a lung tumor and in one case an atypical mycobacteriosis. One of the patients with positive CXR did not report cavitation in the area corresponding to the CT scan and therefore was considered a false positive. Considering CT as the gold standard of reference, we obtain the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV)for LUS and CXR. These characteristics for LUS are: sensitivity 39.5%, specificity 100%, PPV 100%, NPV 65.7%. Instead for CXR are: sensitivity 68.4%, specificity 97.8% PPV 96.3%, NPV 78.2%.

4. Discussion

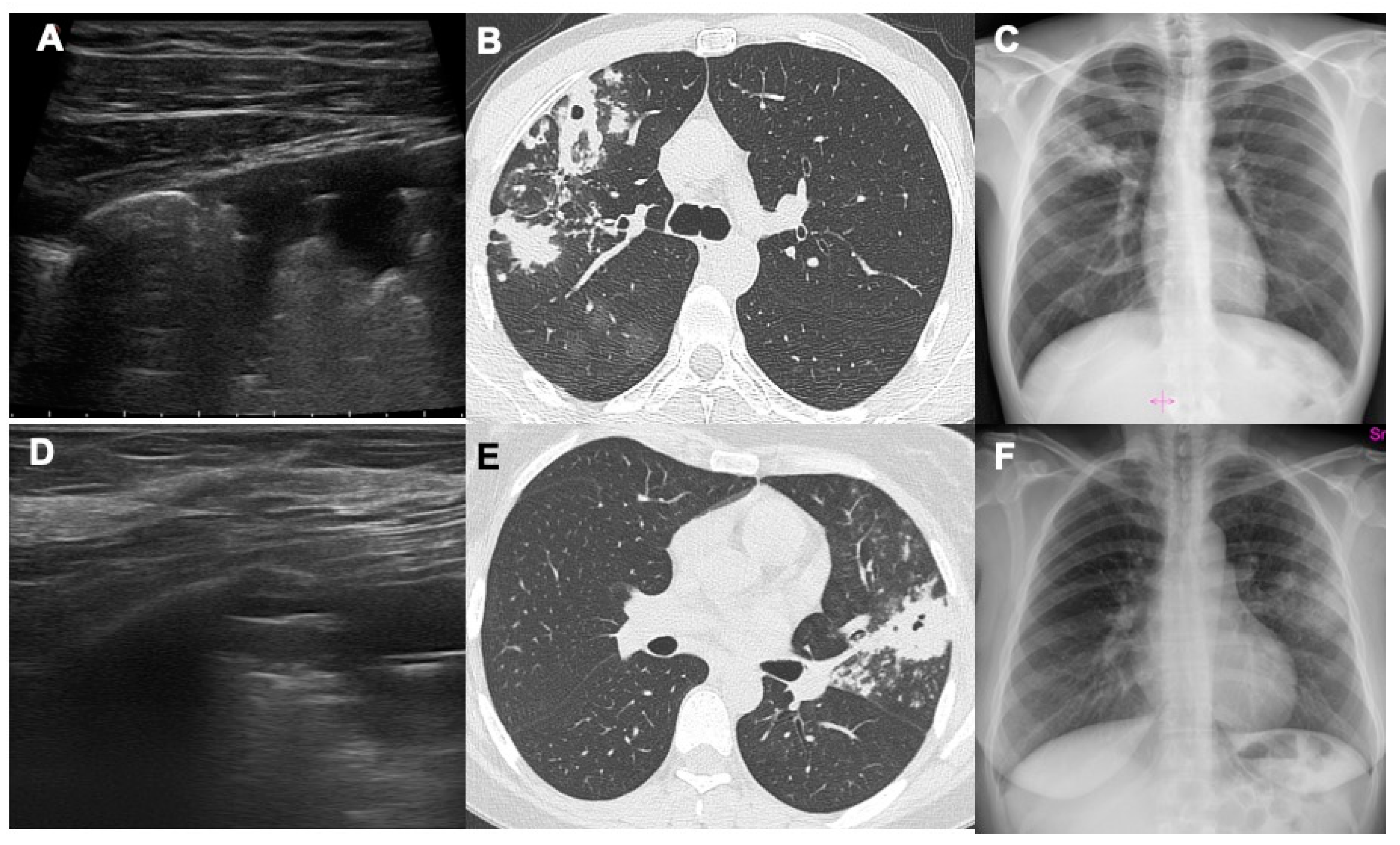

The results of this study show how lung ultrasound can detect air cavitations with relative confidence by highlighting a thin air crescent convex towards the pleural surface within a hypoechoic area of consolidation, easily distinguishable from the dynamic and static aerial bronchogram (

Figure 1). No false positive exams were seen in our study. The sensitivity of LUS in identifying cavitations turned out to be rather low as many cavitated consolidation do not reach the pleural surface or are located behind the scapula, a typical region of post-primary TB.

As previously done by other authors, we investigated patients with consolidation (myco-tuberculous, bacterial or neoplastic) of the tissues surrounding the cavitation which allowed to better highlight the crescent of air’s sickle within the hypoechoic consolidation [

13]. In patients without consolidation surrounding the air cavitation, it could appear difficult to distinguish the air in the cavitation from the air in the lung [

7,

14]. If computed tomography or CXR (which have a significantly higher sensitivity) are not available, an ultrasound bedside assessment of the pulmonary findings may be useful. Moreover, it is possible to carry out ultrasound monitoring and follow up of cavitations without ionizing radiation; in fact, through computed tomography and/or CXR we can understand which cavitations reach the pleural surface and could be visible by LUS exam and therefore which findings can be monitored by ultrasound itself [

8,

14,

15]. Cavitations are not pathognomonic of TB as they can also be found in patients with bacterial pneumonia, atypical mycobacteriosis, abscesses, septic emboli, aspergillosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, malignant tumor [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. With LUS we were able to identify lung air cavitations without a close relationship with dimensions (both large and small). Moreover, we found three essential prerequisites to identify cavitations: a large consolidated area in proximity, the area of consolidation should reach the pleural surface and the possibility to scan the pleural surface at this level. In fact, most of the cavitations that we were unable to evaluate by LUS were surrounded by small areas of parenchymal thickening that did not reach the pleura or were located at the upper or middle posterior regions because hidden by the scapula [

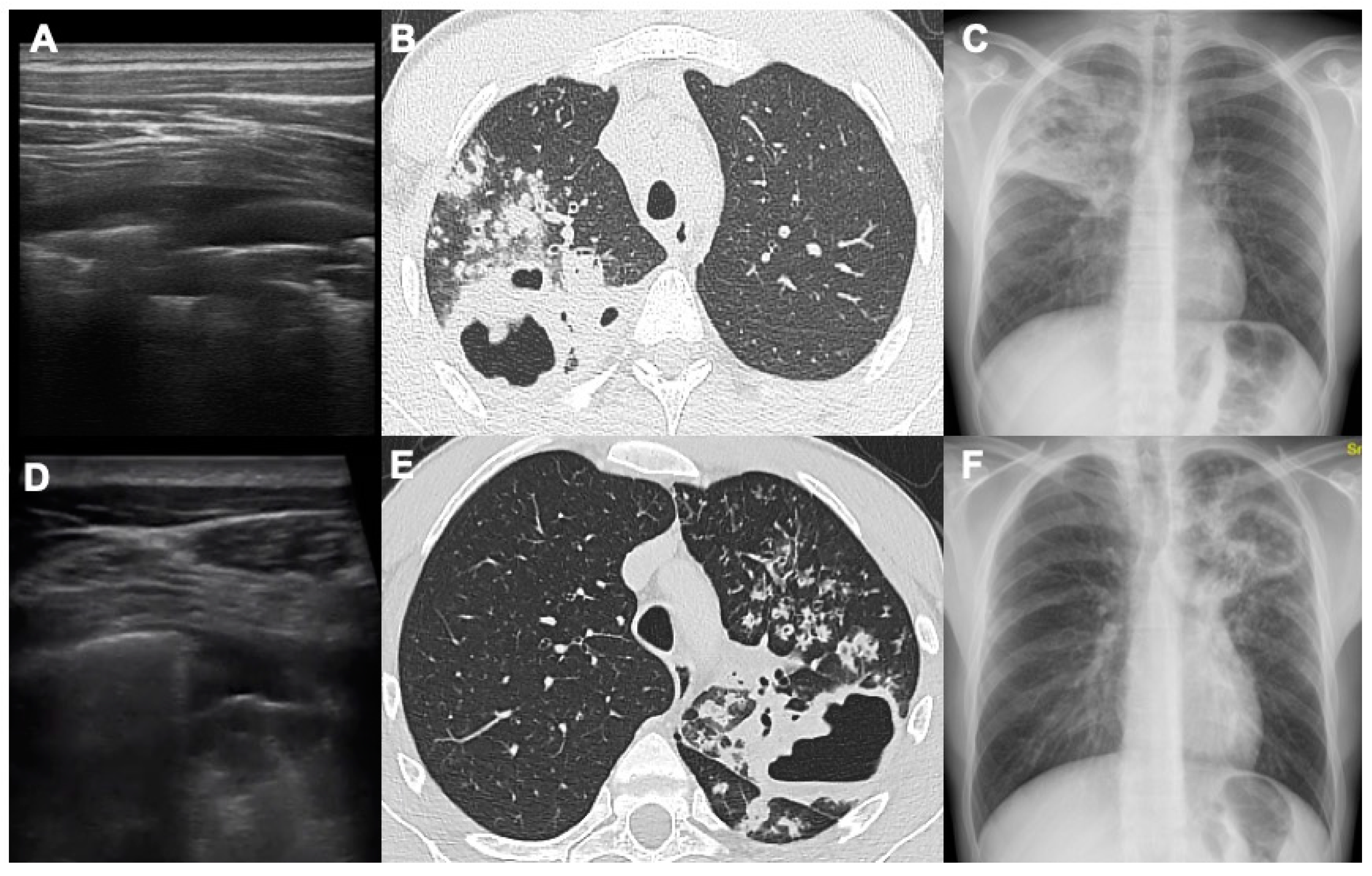

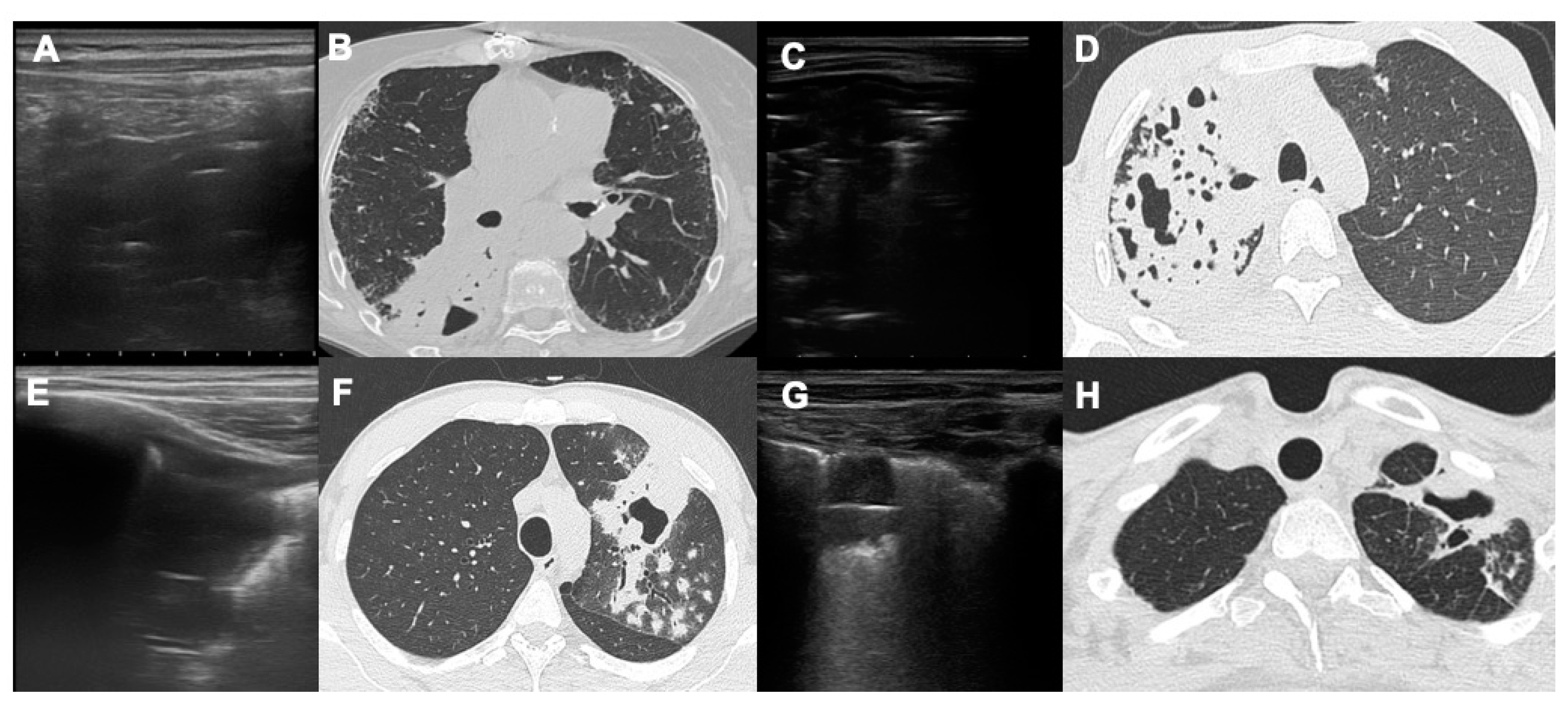

22]. With LUS it is possible to detect the presence of a thin crescent air with a slightly convex margin towards the pleural surface in the context of pulmonary consolidation (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Ultrasounds were able to penetrate in a consolidation, which is defined as lung“hepatization”. In the context of this consolidation two types of air bronchogram have been classically described, both characterized by the presence of hyperechoic air in the context of a hypoechoic consolidation [

22,

23]. The dynamic air bronchogram is determined by the presence of air moving through the patent bronchi of the consolidation; in this case the air is arranged in a branched manner within the consolidation, corresponding exactly to the bronchial branches and in the dynamic phase it is possible to see the movement of the air itself inside the bronchi. The static bronchogram, on the other hand, is characteristic of resorptive atelectasis and in a smaller number of cases of pneumonia; in this case we see numerous air bubbles that do not change over time in the context of densification. Compared to cavitations, the air of the static bronchogram is represented by a greater number of air bubbles that appear smaller, irregular and arranged at numerous levels of depth. In cavitations, on the other hand, we see a single large air interface which represents the outermost air surface of the cavitation [

22,

23]. One of the advantages of this technique is that lung ultrasound is a “dynamic exam”: it is possible to evaluate real-time movement of the pleural surface and even the air within the bronchi in the air- bronchogram, especially in the dynamic one [

22]. It is known that LUS is a non-invasive and radiation-free approach, especially in young patients with suspected TB and it has a good sensitivity together with CXR, compared to computed tomography exam [

11]. As already affirmed in our previous work, it is known that LUS and CXR can detect different findings in a complementary way: LUS can detect even small lesions at the pleural interface such as tiny septal and pleural thickening, subpleural micronodules and consolidations and pleural effusions [

11]. On the other hand, CXR is a more panoramic and less sensitive exam in which small lesions appear more difficult to be identified [

24,

25,

26,

27]. It is known that CXR is more sensitive for consolidations, nodules and cavitations, especially alterations that does not reach the pleural surface and it has shown a much lower sensitivity than the CT (58%), however higher than the sensitivity demonstrated by LUS (33%) in our previous study [

11]. Our results define a sensitivity percentage for LUS of 39.5% and for CXR of 68.4%, compared with CT: it could be interesting the fact that combining the sensitivity of LUS and CXR we obtain a higher sensitivity value, that could be enough in identifying lung and pleural alterations that could be caused by pulmonary TB. Moreover, in our study LUS positive predictive value is 100%, meaning that once TB alterations are detected (with LUS, CT or CXR), LUS could be an optimal tool in the follow up of the peripheral lesions (such as cavitations) during antibiotic therapy.

This work has some limitations: this is a monocentric study with a limited number of patients. It has to be remembered also that LUS does not identify the deepest lesions that do not reach the pleural surfaces and it is an operator-dependent technique, based on the experience of the medical doctor. Another limitation is the difficulty of making a confident radiological diagnosis in case of non-pulmonary TB in patients with similar clinical-radiological and epidemiological features: if needed, BAL or sputum analysis are fundamental in making a correct diagnosis [

28,

29]. On the other hand, our work underlines some LUS advantages widely useful for radiologists and clinicians: is widely available, is safer and cheaper compared to CT, and it can be easily performed in every hospital and health facility also in low-middle income countries [

30,

31]. Moreover, LUS does not require any patient transport because it is a bedside exam nor the presence of expensive CT scanners or dedicated technicians [

32,

33].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, LUS is a valid tool in identifying pulmonary TB lesions, such as cavitations, with a relative low sensitivity but a very high positive predictive value. Combining LUS with CXR allows improvement of global sensibility and this is crucial especially in high burden/low CT availability setting or if the patient is not suitable for CT itself. Radiologists have to remember that differential diagnosis between pulmonary TB and other lung diseases is difficult also with CT exam in some cases, but subpleural cavitations or other parenchymal alterations detected with LUS can be followed up without radiation exposure allowing a confident radiological disease’s monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., E.C. and D.C.; methodology, M.B.; validation, M.B., E.C. and V.M.; formal analysis, D.C.; investigation, D.C., F.G., I.C., F.R.; data curation, D.C., F.G., I.C., F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.; writing—review and editing, D.C., F.G.; project administration, M.B and V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee ofCareggi University Hospital (protocol code rif. CEAVC 14816).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083851 ISBN 978-92-4-008385-1.

- Harding, E. WHO global progress report on tuberculosis elimination. Lancet Respir Med 2020, 8(1):19. [CrossRef]

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tuberculosis-tb-by-country-rates-per-100000-people/who-estimates-of-tuberculosis-incidence-by-country-and-territory-2020-accessible-text-version.

- Yoder MA, Lamichane G, Bishai WR et al. Cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis: the holy grail of disease transmission. Curr Sci 2004, 86:74-81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24109518.

- Suttels V, Du Toit JD, Fiogbé AA et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for tuberculosis management in Sub-Saharan Africa: a balanced SWOT analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2022, 123:46-51. [CrossRef]

- Urbanowski ME, Ordonez AA, Ruiz-Bedoya CA et al. Cavitary tuberculosis: the gateway of disease transmission. Lancet InfectDis 2020, 20(6):e117-e128. [CrossRef]

- Jamal F, Hammer MM. Nontuberculous Mycobacterial infections. RadiolClin North Am 2022, 60(3):399-408.

- Chen RY, Yu X, Smith B et al. Radiological and functional evidence of the bronchial spread of tuberculosis: an observational analysis. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2(10):e518-e526. [CrossRef]

- Volpicelli, G. Point-of-care lung ultrasound. Praxis 2014, 103(12):711-716.

- Nazerian P, Volpicelli G, Vanni S et al. Accuracy of lung ultrasound for the diagnosis of consolidations when compared to chest computed tomography. Am J Emerg Med 2015, 33(5):620-625. [CrossRef]

- Giannelli F, Cozzi D, Cavigli E et al. Lung ultrasound (LUS) in pulmonary tuberculosis: correlation with chest CT and X-ray findings. J Ultrasound 2022, 25(3):625-634. [CrossRef]

- Giordani MT, Heller T. Role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Eur J Intern Med 2019 66:27-28. [CrossRef]

- Montuori M, Casella F, Casazza G et al. Lung ultrasonography in pulmonary tuberculosis: a pilot study on diagnostic accuracy in a high-risk population. Eur J Intern Med 2019 66:29–34. [CrossRef]

- Busi Rizzi E, Schininà V, Palmieri F et al. Cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis HIV-related. Eur J Radiol 2004, 52(2):170-4. [CrossRef]

- Alshoabi SA, Almas KM, Aldofri SA et al. The diagnostic decriver: radiological pictorial review of tuberculosis. Diagnostics 2022, 12(2):306.

- Cardinale L, Parlatano D, Boccuzzi F et al. The imaging spectrum of pulmonary tuberculosis. Acta Radiol 2015, 56(5):557-64. [CrossRef]

- Cozzi D, Cavigli E, Moroni C et al. Ground-glass opacity (GGO): a review of the differential diagnosis in the era of COVID-19. Jpn J Radiol 2021, 39(8):721-732. [CrossRef]

- Cozzi D, Moroni C, Addeo G et al. Radiological patterns of lung involvement in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol ResPract 2018, 2018:5697846. [CrossRef]

- Holt MR, Chan ED. Chronic cavitary infections other than tuberculosis: clinical aspects. J Thorac Imaging 2018, 33(5):322-333.

- Ketai L, Currie BJ, Holt MR et al. Radiology of chronic cavitary infections. J Thorac Imaging 2018, 33(5):334-343. [CrossRef]

- Cozzi D, Bargagli E, Calabrò AG et al. Atypical HRCT manifestations of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Radiol Med 2018, 123(3):174-184. [CrossRef]

- Soldati G, Demi M, Smargiassi A et al. The role of ultrasound lung artifacts in the diagnosis of respiratory disease. Expert Rev Respir Med 2019, 13(2):163-172. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein DA, Lascols N, Meziere G et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of alveolar consolidation in the critically ill. Intensive CareMed 2004, 30: 276-281. [CrossRef]

- Amatya Y, Rupp J, Russel FM et al. Diagnostic use of lung ultrasound compared to chest radiograph for suspected pneumonia in a resource-limited setting. Int J Emerg Med 2018, 11:8. [CrossRef]

- Esayag Y, Nikitin I, Bar-Ziv J et al. Diagnostic value of chest radiographs in bedridden patients suspected of having pneumonia. Am J Med 2010, 123(1): 88e1-5. [CrossRef]

- Hagaman JT, Rouan GW, Shipley RT et al. Admission chest radiograph lacks sensitivity in the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med Sci 2009, 337(4):236-240. [CrossRef]

- Hayden GE, Wrenn K. Chest radiograph vs. computed tomography scan in the evaluation of pneumonia. J Emerg Med 2008, 36(3):266-270.

- Morello R, De Rose C, Ferrari V et al. Utility and limits of lung ultrasound in childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: lessons from a case series and literature review. J Clin Med 2022, 11(19):5714. [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli IL, Barros M, Pacini GS et al. Multiple cavitary lung lesions on CT: imaging findings to differentiate between malignant and benign etiologies. J Bras Pneumol 2019, 46(2):e20190024. [CrossRef]

- Heller T, Mtemang’ombe EA, Huson MA et al.Ultrasound for patients in a high HIV/tuberculosis prevalence setting: a needs assessment and review of focused applications for Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Infect Dis 2017, 56:229-236. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Chest radiography in tuberculosis detection. World Health Organization, Geneva 2016.

- Di Gennaro F, Pisani L, Veronese N et al. Potential Diagnostic properties of chest ultrasound in thoracic tuberculosis: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15(10):2235. [CrossRef]

- Cocco G, Boccatonda A, Rossi I et al. Early detection of pleuro-pulmonary tuberculosis by bedside lung ultrasound: a case report and review of literature. Clin Case Rep 2022, 10(7): e05739. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).