1. Introduction

Radiotherapy is an important treatment for head and neck tumors. However, during the treatment, the temporal bone and its accessory structures are often difficult to avoid exposure to ionizing radiation, resulting in damage to auditory pathways [

1,

2] including conductive hearing loss (such as otitis media, ossicular chain necrosis, etc.) and sensorineural hearing loss, which is manifested as delayed, progressive and irreversible hearing loss, often with high-frequency hearing loss as the first [

3]. In an open-label, phase 2, randomized trial of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, radiation-induced sensorineural hearing loss (RISNHL) occurred in 38% of patients after radiotherapy [

4]. Research on children who suffered head-and-neck tumors confirms that the onset of high-frequency hearing loss will be accelerated by platinum-based chemotherapy if mean cochlea radiation doses are > 20 Gy. Patients develop a rapid onset of lower-frequency hearing loss after early high-dose radiation (> 30 Gy) exposure regardless of platinum exposure, and this RISNHL continues to increase in incidence over time [

5]. Even though the timing and degree of ototoxicity after radiotherapy varies clinically, and the correlation between ototoxicity and ionizing radiation dose remains unclear, it is of particular interest to study the pathogenesis of RISNHL.

Changes in inner ear morphology and auditory pathways after ionizing radiation are widely recognized to be related to tissue absorption dose and exposure time. Currently, the oxidative stress-apoptosis theory is the prevailing view to explain the dysfunction and death of auditory-related cells in the inner ear and RISNHL. Ionizing radiation directly causes DNA damage, including double-strand breaks, and produces large amounts of oxygen radicals. The unusually high concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within tissues result in metabolic dysregulation and structural/functional alterations [

6]. Meanwhile, ionizing radiation disrupts vascular permeability [

7] and causes dysfunction of cochlear lymphatic circulation [

8]. Temporary dysfunction of cochlear microcirculation may indirectly affect sensory epithelium function and survival. In the cochlear radiation model, disruption of the stria vascularis (SV) and loss of the outer hair cells (OHCs) in mice are verified to be attributed to ROS-related increases in the 4-HNE level and DNA damage-related increases in the level of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. The modulation of ROS by antioxidants in C57BL/6 mice reduced radiation-induced inner ear damage and hearing loss [

9,

10]. It is also reported that the cochlear ribbon synapse is very sensitive to ionizing radiation, and this pathological change can occur in the acute phase after irradiation [

11]. Radiation-induced tissue cell death is confirmed with the generation of ROS and the consequent activation of caspase, inflammation, apoptosis [

12], and/or necrosis [

13]. The biological functions of the body's immune system are diverse. In the past, the inner ear was wrongly thought to be an immunologically exempt organ because of the blood-labyrinth barrier in the inner ear. However, in recent years, it has been found that the activation and aggregation of inner ear macrophages are closely related to hair cell survival and hearing function in noise-induced deafness [

14] and gjb2 hereditary deafness models [

15]. They demonstrated that the death of cochlear hair cells or neurons due to external stimulation is often accompanied by macrophage aggregation and local inflammation. Macrophages can remove necrotic cells and activate an immune inflammatory response in the inner ear, which affects the function of inner ear hair cells. However, evidence has shown that macrophage overactivation and macrophage-associated immune inflammatory response may be a bidirectional process [

16], and the specific contribution of this response to auditory cell function is not well defined. More importantly, the role of post-radiation changes in cochlear immune cells and inflammatory mediators remains unclear, and in particular, the role of cochlear macrophage-related immune inflammatory responses in radiation-induced ear injury remains to be elucidated.

In this study, we first model sensorineural hearing loss induced by high doses of radiation. We then looked at the effects of ionizing radiation on auditory-related cells and macrophages in the inner ear of mice and detected changes in circulation and cochlear inflammatory mediators in mouse immune cells in the short-term after high-dose radiation to elucidate the pathogenesis of RISNHL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

In this study, 8-week-old male Cx3cr1

GFP/+ heterozygous mice were bred in-house on a CBA/j background. The GFP gene replaces one allele of CX3CR1, a fractalkine receptor. Cx3cr1 is expressed in macrophages, monocytes, microglia, NK cells, and related cells [

14]. As a result, Cx3cr1

GFP/+ mice can express GFP in all macrophages, facilitating the tracking of the number and location of macrophages in the interior. Auditory brainstem response (ABR) tests were performed on all mice before the experiment to ensure they have quite a good hearing function. All the mice were bred in the SPF Animal Room of the Laboratory Animal Center of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The operator holds the Laboratory Animal Professional Technical Examination certificate.

2.2. Radiation Exposure

Mice were anesthetized by Zoletil 50(30 mg/kg, Virbac, Fronce) and Xylazine (10 mg/kg, LGM Pharma, America) through intraperitoneal injection. The irradiation field was adjusted to 8 cm ×40 cm covering the cranial of several mice. The source axis distance to the shaft was 100 cm and the thickness of the lead block was 10 cm [

17]. Mice were irradiated with a single dose of 30 Gy by 6-MV X-rays (600 MU min−1, Trilogy System Linear Accelerator, Varian Medical Systems) [

17].

2.3. Auditory Brainstem Response

After being deeply anesthetized, the mice were placed in a thermostatic blanket to maintain body temperature during the measurement. There were three electrode pins to be placed, the reference electrode was inserted under the skin of the mastoid of the test ear (reversed electrode), the recording electrode was inserted under the skin of the median cranial top of the mouse (simultaneous electrode), and the common electrode was inserted under the skin of the mastoid of the opposite ear (grounded). The computer's TDT system is turned on to generate the stimulus sound, which is amplified by the device and transmitted to a speaker and then to the ear, where the evoked potential is transmitted to a signal processor in the computer for superposition processing. The stimuli were short pure tones at 4 kHz, 8 kHz, 12 kHz, 16 kHz, 20 kHz, 24 kHz, 28 kHz, and 32 kHz with a repetition rate of 10 per second, a scan time of 10 ms, and a superposition of 512 times. The sound intensity of the test starts at 90dB SPL and gradually decreases by 5dB SPL after approaching the threshold value, which is represented by the sound intensity of the ABR II wave in the brainstem potential wave group that can be recognized by the naked eye [

18].

2.4. Blood Sample and Cochlear Acquisition

Under anesthesia following the ABR test, the eyeballs of the mice were quickly removed and we obtained blood from the retroorbital venous plexus. The blood is collected into a glass tube pre-filled with anticoagulant until the bleeding stops. The mice were then killed by cervical dislocations, with the cochlea carefully detached from the temporal bone and placed in pre-cooled, fresh 4% paraformaldehyde. The circular and oval windows of the cochlea were opened under a microscope, and the cochlea was rinsed with an infusion of paraformaldehyde with a needle to make the cochlea white. The cochlea was placed in 4% paraformaldehyde in a refrigerator at 4℃ overnight.

2.5. Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) Staining

The cochlear section was immersed in PBS solution for 10 min for OCT removal, 3 min for hematoxylin, and washed with tap water for 30 seconds. Dip in 1% ethanol for 2s, dye in eosin for 4min, dip in 95% ethanol for 2min, dip in anhydrous ethanol for 2min, clear with xylene for 10min, then seal with neutral glue.

2.6. Immunofluorescence Staining

After the fixed cochlea was decalcified in 10% EDTA solution for 24 hours, for frozen sections, the cochlea was dehydrated with 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose solutions for 1 hour, respectively, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) overnight at 4 °C. A section of the medial axis of the cochlea with a thickness of 10 mm was removed for subsequent experiments. For basilar membrane placement, each cochlea was carefully dissected in 0.01 M of frozen PBS. Cochlear sections or basement membrane products were incubated in a blocking solution (10% Donkey serum plus 0.1% Triton X-100) at room temperature for 1 hour. The samples were then incubated with rabbit anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (1:200 dilution, M048-3, MBL, Beijing, China) or anti-Neurofilament Heavy Chain antibody (1:500 dilution, AB5539, Sigma-Aldrich, America) at 4℃ overnight. The samples were washed 3 times in 0.01 M PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, and then stained with Alexa Fluor 647 Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (1:200 dilution, ANT032, Antgene, China) or Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey Anti-Chicken IgY (1:200 dilution, A78948, Thermo Fisher Scientific, America) for 2 hours. DAPI (C1005, Beyotime Biotechnology) and phalloidin (0.05 mg/ml, P5282, Sigma-Aldrich) were used for nuclear and F-actin staining. Images were obtained using laser scanning confocal microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Macrophages were visualized using GFP immunostaining.

2.7. Cell Count

The basal membrane was scanned and 3D reconstructed under a 10× mirror. The ImageJ software was used to take 1.5 mm lengths at the top, transition, and bottom, respectively. The region between the inner hair cells and the third exclusive hair cell is the sensory-sensitive neuroepithelial region.

2.8. RNA Preparation and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RT-qPCR detected transcriptional expression levels of the following genes: TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2, CCL3, and CCL4. After killing the animal, the connective tissue around the cochlea was carefully removed from the ice. One cochlea was used as a sample and six biological replications were performed for each experimental condition. Total RNA was extracted from collected tissues using FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit V2 (Vazyme. Nanjing, China). Reverse transcription was performed using HiScript III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme. Nanjing, China). RT-qPCR was performed on the Roche LightCycler 480 instrument using the SYBR green PCR technique. Each group's relative gene expression data were analyzed by standard method 2-△ct. RT-qPCR uses the following primers:

GAPDH Forward GCCAAGTATGATGACATCAAGAAGG

GAPDH Reverse GCTGTAGCCGTATTCATTGTCATAC

IL-1β Forward GAAATGCCACCTTTTGACAGTG

IL-1β Reverse TGGATGCTCTCATCAGGACAG

IL-6 Forward AATTTCCTCTGGTCTTCTGGAGTAC

IL-6 Reverse GACTCCAGCTTATCTGTTAGGAGAG

TNFα Forward CAGGCGGTGCCTATGTCTC

TNFα Reverse CGATCACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAG

CCL3 Forward GCAACCAAGTCTTCTCAGCG

CCL3 ReverseTCTCTTAGTCAGGAAAATGACACC

CCL4 Forward TGTGCAAACCTAACCCCGAG

CCL4 ReverseGGGTCAGAGCCCATTGGTG

CCL2 Forward TAAAAACCTGGATCGGAACCAAA

CCL2 ReverseGCATTAGCTTCAGATTTACGGGT

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All values in the figures were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For three or more groups, we first performed an ANOVA analysis. For a P value < 0.05, we then used t-tests to compare pairs of subgroups. We compared the data between groups using an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The high dose of irradiation caused a dramatic reduction of macrophages in the inner ear. Traditionally, the inner ear has been wrongly recognized as an “immune privileged” organ due to the blood-labyrinth barrier. Our previous studies have confirmed that macrophages exist in stria vascularis, basilar membrane, and SGN, and perivascular resident macrophages in the stria vascularis are essential for the integrity of the blood-labyrinth barrier and cochlear internal environment [

21]. Cochlear macrophages are the primary immune cells in the cochlea and play an important role in maintaining homeostasis in the immune microenvironment of the inner ear. The migration and activity of macrophages show complicated changes after cochlear injury, including noise [

14], toxins, ototoxic antibiotics, or viral infection. Regulation of macrophage-mediated immune response may be a therapeutic approach to various trauma-induced hearing loss [

15,

21,

22]. Macrophages have been found to increase and aggregate in the sensory epithelial damaged area both in the noise-induced hearing loss [

23] model and connexin26 deficiency hearing loss model [

15]. However, we first find that cochlear macrophages are significantly reduced in our radiation-induced hearing loss model. This result is consistent with some previous in-vitro studies, which have reported little in animal models of local radiation. The proliferation of bone marrow-derived macrophages can be almost complete inhibition within 72 hours after 10 Gy γ-radiation through direct DNA damage and caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis mechanism [

24]. Researchers also suggested that ionizing radiation promotes macrophage polarization patterns toward a proinflammatory M1-like phenotype [

25,

26]. Our experiment also observed radiation caused bone marrow suppression [

27] in mice, which is characterized by the rapid decrease of white blood cells, platelets, lymphocytes, and intermediate cells in circulation. Therefore, we speculate that high-dose irradiation not only kills the cochlea macrophages but also blocks the chemotactic recruitment of circulating macrophages to the inner ear. Radiation-induced activation of macrophages produces damaging bystander signals [

24,

26]. It is known that M1 macrophages can secrete cytotoxic pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α. M2 macrophages promote to repair the damaged tissue through the expression of anti-inflammatory factors, including Arginase-1, CD206, and IL-4RA [

28]. Low-dose irradiation generally promotes macrophage polarization toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, while high-dose irradiation is more likely to augment the pro-inflammatory properties of macrophages and promote the expression of various pro-inflammatory genes (IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2, and TNF-α) [

26,

29]. In vivo, irradiation enhanced the M1-like features of macrophages from CBA/Caj mice [

30]. Cranial radiotherapy-mediated bystander effect, neuroinflammation, and immune cell infiltration are dependent on macrophage-associated immune response [

31]. Our experiment shows that high-dose radiation of CBA/Caj mice cranial led to immune microenvironment disturbance of the inner ear, as shown by rapid up-regulation of inner ear IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL2 on the first day after radiation. As the number of macrophages decreases, the expression of inflammatory factors also decreases in a time-dependent manner. We speculate here that the bystander effect induced by high doses of irradiation, including changes in SGN cell and neurofilament expression, may be mediated by activation of the M1-like proinflammatory response.

Ionizing radiation not only suppresses tumor cells but also causes radioactive damage to normal tissue. The causes of bystander cell damage are as follows: On the one hand, ionizing radiation can directly cause DNA damage and cell death. On the other hand, radiation can indirectly promote cell-cycle arrest, cell senescence, necrosis, or apoptosis through excessive oxidative stress and inflammation [

12,

32], which eventually leads to tissue microenvironment destruction and functional disorder [

33]. During the treatment of head and neck cancer, sensorineural hearing loss is one of the “radiation-induced bystander effects”. Ionizing radiation can indirectly damage auditory-associated cells and structures, resulting in auditory abnormalities and vestibular dysfunction. Previous studies have observed changes in inner ear structure and auditory function in the chronic phase after exposure to low to moderate-intensity radiation. Earlier in the 1970s, G M Thibadoux et al. serially assessed the hearing sensitivity of 61 children treated with 2,400 rads of cranial radiation, and the assessments of individual audiograms revealed that none of the children had any significant reductions in hearing levels at 3 years after exposure [

34]. Therefore, we speculate that low-dose radiation exposure has no significant effect on hearing. Pathological studies of the temporal bones of nuclear power plant workers exposed to 20 hours of high-dose radiation revealed mild degeneration of cochlear SGN cells and sensory hair cells after 7 months [

35]. D L Hoistad et al [

36] studied histopathologic slides of human temporal bones after a total of 60-70Gy doses of radiotherapy. Loss of inner and outer hair cells, reduction of SGN cells, and atrophy of stria vascularis were demonstrated in groups receiving cis-platinum, radiation, and combination compared to normal controls. As a result, high-dose radiation can contribute to otologic sequelae including SNHL, vascular changes, serous effusion, or fibrosis. Keilty, Dana, et al. put forward that the cumulative incidence of HL was 50% or greater at 5 years after RT if the mean cochlea dose was > 30 Gy. A mean cochlea dose of ≤ 30 Gy is suggested as a goal to reduce the risk of HL [

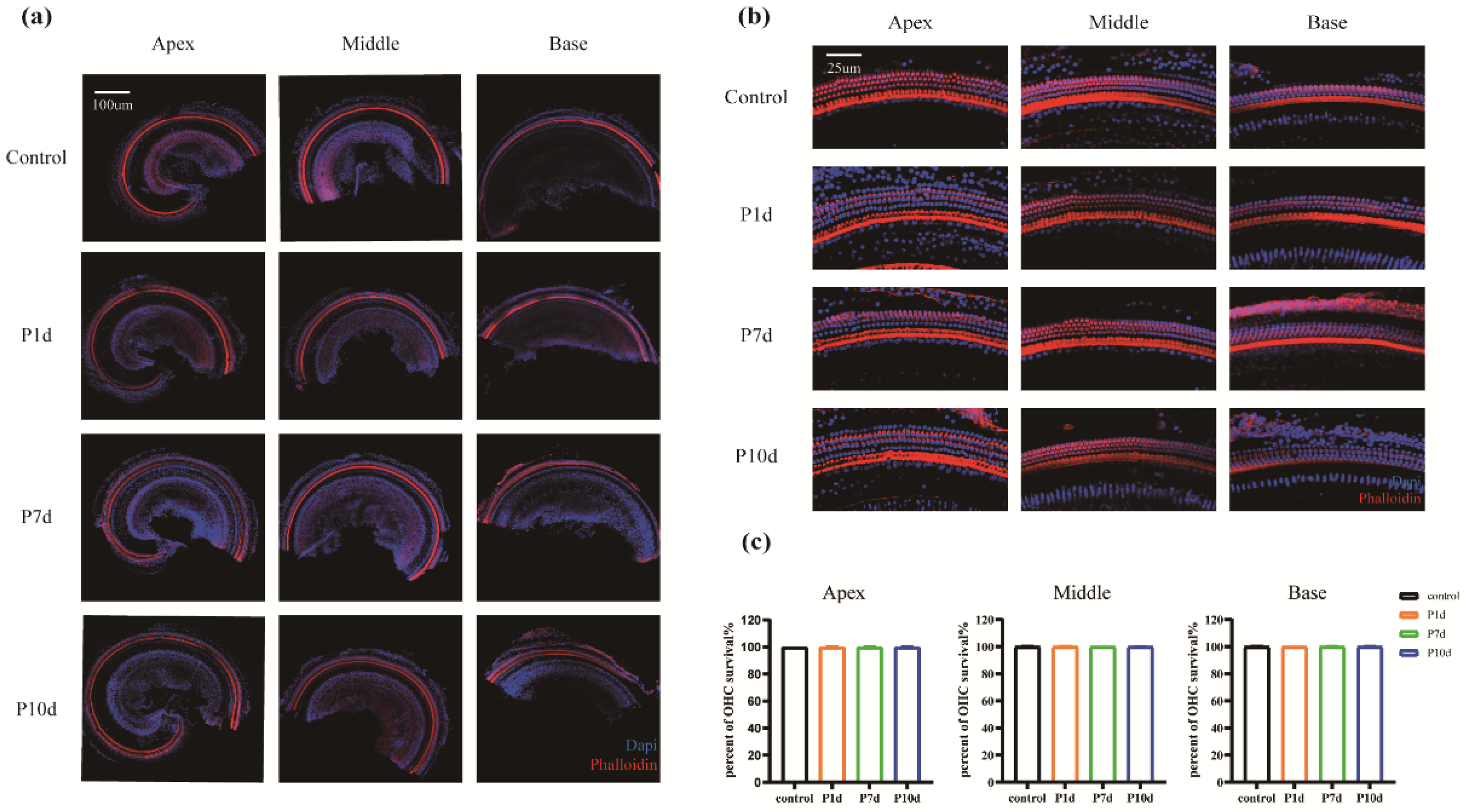

5]. In our model, there is no significant loss of basal membrane hair cells in mice after 30Gy X-ray exposure and no change in the ABR threshold during the first-week post-radiation. In the P10d group, the ABR threshold increases significantly for all tested frequencies, accompanied by a prolonged delay and a down-regulated amplitude of the ABR I wave. These results are at odds with many previous studies [

3,

5,

17,

37,

38] that have highlighted the loss of outer hair cells in mice after irradiation. They also proposed that the hair cell loss at the basilar membrane is significantly higher than at the apex. Correspondingly, hearing loss occurs preferentially in the high-frequency region and then slowly moves toward the low-frequency region. Cell cycle regulation is the most important determinant of ionizing radiation sensitivity, with cells being most radiosensitive in the G (2) -M phase. Sometimes, radiation-induced DNA damage initiates signals that can ultimately activate irreversible growth arrest that results in cell death (necrosis or apoptosis) [

39]. Cells with active proliferation and division (such as malignant tumor cell, stem cell) are mostly in the M phase of cell cycle, so they are very sensitive to radiation, which is the molecular biological principle of radiation therapy. On the contrary, terminally differentiated cells have lost the ability to divide so they are not sensitive to radiation, such as neuron, myocyte [

40]. Therefore, sensory hair cells of the mammalian inner ear, as highly differentiated mature cells, cannot divide [

41], so they are not sensitive to radiation. In our experiments, high-dose irradiation did not cause cochlear hair cell loss, in agreement with the above theory. Chronic hair cell loss caused by low/moderate-dose irradiation in some studies may be a manifestation of the "bystander effect". For example, Pyun, J.H. et al. [

42] confirmed that 20Gy-photon beams induced ABR threshold shift in rat and auditory neuromast loss in the zebrafish. They also found apoptosis and intracellular ROS production in cortico-derived cell lines. Further experiments have shown that blocking ROS production may protect auditory cells from radiation in vitro and in vivo. Similarly, severe damage to the cochlea and vestibule induced by radiation was alleviated by an anti-inflammatory drug, which was confirmed to down-regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory factor TNFαand upregulate the expression of anti-inflammatory factor IL-2 in the cochlea after radiation [

43]. Our study is limited to results obtained within 10 days after a single 30Gy X-ray cranial irradiation of 8-week-old CBA/caj mice. At the same time, the health of the mice deteriorated after high doses of irradiation. Some P10d individuals were too weak to tolerate anesthesia, at which point the ABR audiometry may not reflect the true function of the mouse's cochlea.

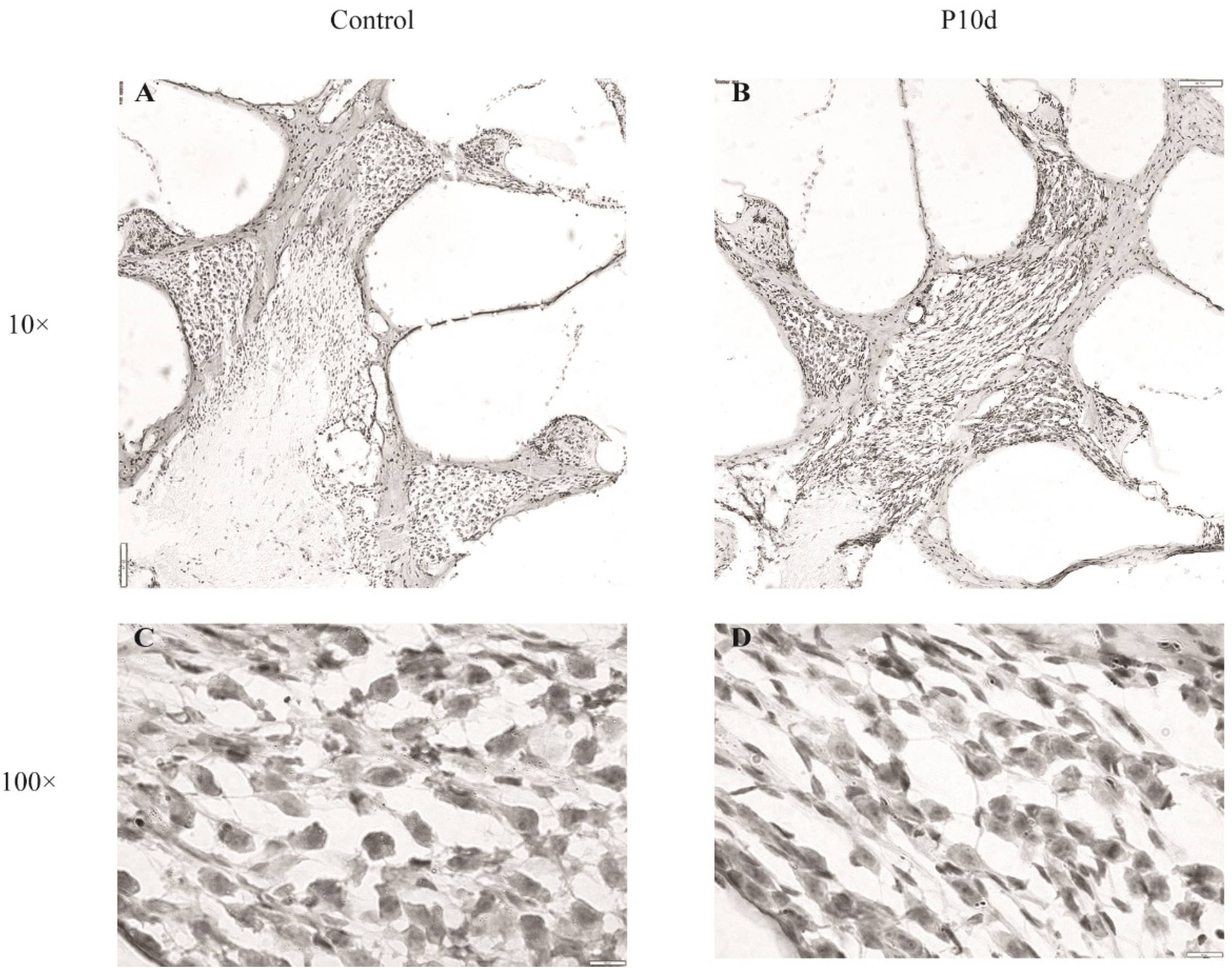

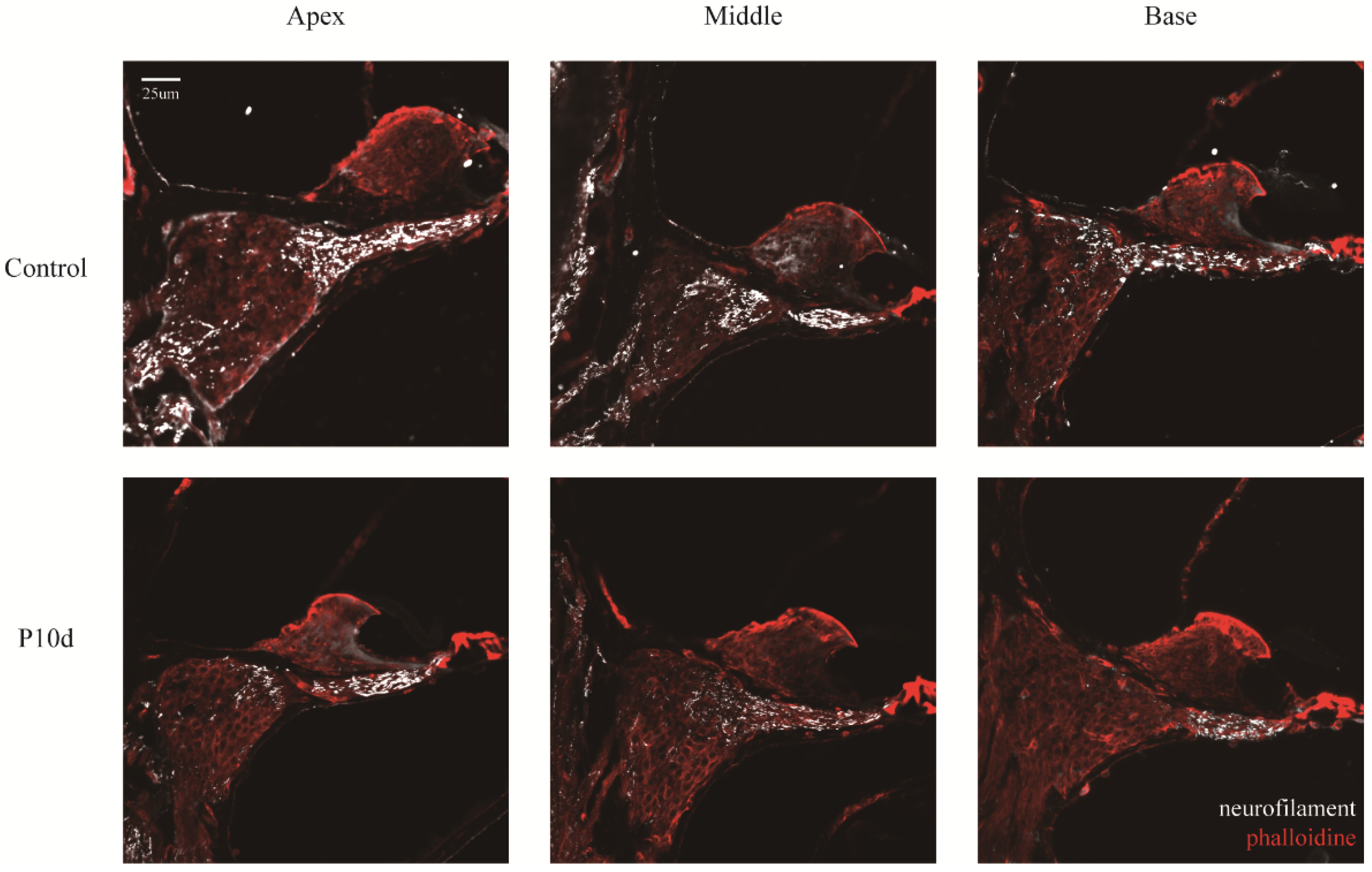

Our results suggest that acute RISNHL is not caused by cochlear hair cell death, but may be related to the morphological changes of cochlear SGN and nerve conduction disorders [

44]. These results are in agreement with a small number of previous studies. The study by Gasser Rutledge, K. L administered 10-60 Gy γ-ray radiation doses to the cranial of mice. They found significant ABR threshold shift occurred at all test frequencies in mice exposed to ≥ 20 Gy by 8 days post-irradiation, and the initial impact of radiation in the first-week post-exposure focuses on SGN cell bodies and peripheral projections. Neuronal density and extracellular matrix are dramatically reduced in the Rosenthal canal and spiral lamina. No differences were noted within the Gy group in the frequency or severity of pathology along the length of the cochlea. At the same time, hair cells, stria vascularis, and vasculature showed negligible changes [

45]. Liu, Z. et al. [

11] gave cobalt-60 rays at doses of 10 Gy or 20 Gy to mice heads, and they also verified no significant changes in the number of hair cells or the array for the treatments. The number and size of the pre-synaptic ribbons (labeled by anti-RIBEYE/CtBP2 antibody) and the expression of VGLUT-3 were downregulated by radiation, resulting in RISNHL. The acute RISNHL in our model may be induced by a potential impairment of the auditory conduction pathway after cranial irradiation. Studies have confirmed that ionizing radiation can directly damage nerve myelin, Schwann cells, and fibrin in short time [

46], leading to nerve microfilaments and microtubules aggregation, nerve fiber density reduction, nerve inner and outer membrane fibrosis, nerve axons and myelin degeneration or even necrosis[

47,

48,

49]. In our experiments, we hypothesize that SNHL in the short term of high-dose radiation may be associated with morphological changes in inner ear SGN cells and reduced neurofilament. Compared with the control group, the nuclei of the SGN were knotted and darker in color, and the whole cell was spindle-shaped in the mice exposed to the radiation. Atrophied cells have fewer organelles, especially the mitochondrial, leading to their ability to metabolize substances and respond to neuroendocrine stimuli downfall, and those atrophied cells will eventually die [

50]. In the traumatic brain injury model, the loss of brain parenchyma was secondary to progressively neuronal atrophy and eventually programmed cell death [

51]. Neurofilaments provide structural support to the highly asymmetric geometry of neurons and are essential for efficient neural conduction velocity. Neurofilaments in axons extensively interconnect with cytoskeletal elements, creating a regionally specialized network for material transport. Neurofilament subunits are also present in postsynaptic terminal buttons and may be involved in neurotransmission [

44]. In our study, the atrophy of SGN cells and the down-regulation of neurofilament expression induced by high-dose irradiation are likely to be the main histopathological causes of hearing loss. Radiotherapy can cause auditory neuropathy and Schwann cell death leading to impaired hearing function [

46]. Demyelination of the cochlea SGN (a precursor of neurodegeneration) is associated with impaired auditory neural synchrony [

22]. Therefore, based on the above results, high doses of cranial irradiation may also cause other types of impairments in the auditory nervous system, which needs to be investigated further.

We find that localized irradiation leads to inhibition of cochlear and systemic immune cells, but is accompanied by increased levels of local tissue inflammation. In addition to the explanation of the M1-like proinflammatory response induced by high-dose irradiation, the underlying mechanism of this phenomenon needs to be further explored. In addition, we consider morphological changes in nerve cells and nerve fibers in the inner ear of P10d mice as a possible indication of neurodegeneration or even SGN cell death. These could explain the lack of hair cell loss in RISNHL. After exposure to high doses of ionizing radiation, the number of basilar macrophages decreases in a time-dependent manner and the inflammatory mediators in the cochlea transiently increase. In the future, if we increase the penetration of circulating macrophages into the cochlea or stimulate M2 phenotypic polarization in the inner ear, can we attenuate radiation toxicity and become therapeutic targets for RISNHL prevention? Also, the relationship between spiral ganglion cells, nerve filaments, inner ear neural pathways, inner ear macrophages, and changes in inflammation levels and auditory function needs to be further explored. If we use a neuroprotective agent, is it beneficial to slow down the development of RIHNSL? Moreover, cochlear veins are important for the maintenance of inner ear lymphatic circulation and electrophysiological function [

52], but vascular endothelial cells are very sensitive to ionizing radiation [

53]. A recent study confirmed that radiation causes the cochlear stria vascularis to become less tightly connected. The damage of the blood-labyrinthine barrier and the enhancement of vascular permeability in turn increases the accumulation of cochlear ROS [

54] and eventually leads to RISNHL with significant loss of hair cells [

9]. In addition, perivascular resident macrophage-like melanocytes from the stria vascularis of mice are a crucial component in maintaining the integrity and function of the blood-labyrinth barrier. Thus, the role of the oxidative stress mechanism in the overwhelming M1-like proinflammatory response induced by high doses of radiation in our RISNHL model remains unknown. Whether radiation damages perivascular resident macrophage-like melanocytes in the stria vascularis and whether it causes perturbations in the microcirculation of the inner ear requires further exploration. Acute inner ear inflammation induced by injection of LPS into the tympanum of the middle ear is caused by targeted infiltration and activation of immune cells [

55]. The expression of proinflammatory factors in the pathological cochlea is increased, and the permeability of the blood-labyrinth barrier is enhanced, thus making it more sensitive to external toxic substances [

56]. The acute phase of hearing loss due to bacterial meningitis is partially reversible, and permanent hearing loss due to meningitis after 2 weeks is caused by disruption of the blood labyrinth barrier and SGN necrosis (not apoptosis) [

57]. We hypothesize that early regulation of cochlear immune cell infiltration may preserve hearing loss in acute deafness models.

Overall, this study is a suitable model for acute RISNHL, but observations of immune inflammation in the inner ear are limited due to radiation suppression of the immune system. The next step is to study the role of macrophage-related inflammatory response in regulating the auditory pathway (from sensorial epithelium to auditory cortex).

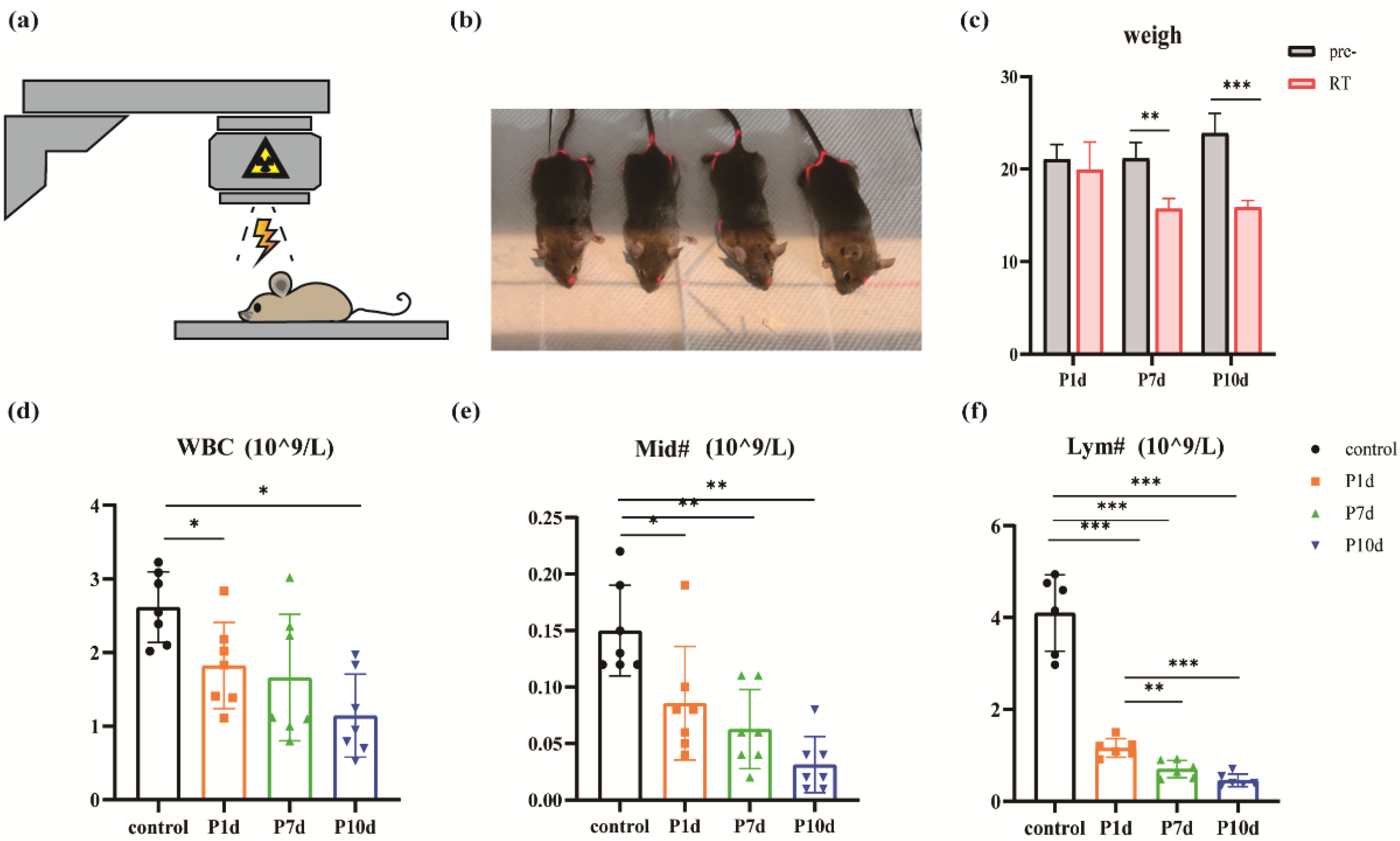

Figure 1.

Radiation model and peripheral immune cell changes in mice. (a)-(b) The exposure pattern of the mouse and the yellow light region is that of the irradiated region. (c) Significant weight loss after exposure to ionizing radiation (** p < 0.01) (*** p < 0.001). (d)-(f) Changes in white blood cell (WBC) count, the absolute value of lymphocytes (Lym#), and the absolute value of intermediate cell (Mid#) in peripheral blood of mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after radiation exposure. (n = 6 in each group).

Figure 1.

Radiation model and peripheral immune cell changes in mice. (a)-(b) The exposure pattern of the mouse and the yellow light region is that of the irradiated region. (c) Significant weight loss after exposure to ionizing radiation (** p < 0.01) (*** p < 0.001). (d)-(f) Changes in white blood cell (WBC) count, the absolute value of lymphocytes (Lym#), and the absolute value of intermediate cell (Mid#) in peripheral blood of mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after radiation exposure. (n = 6 in each group).

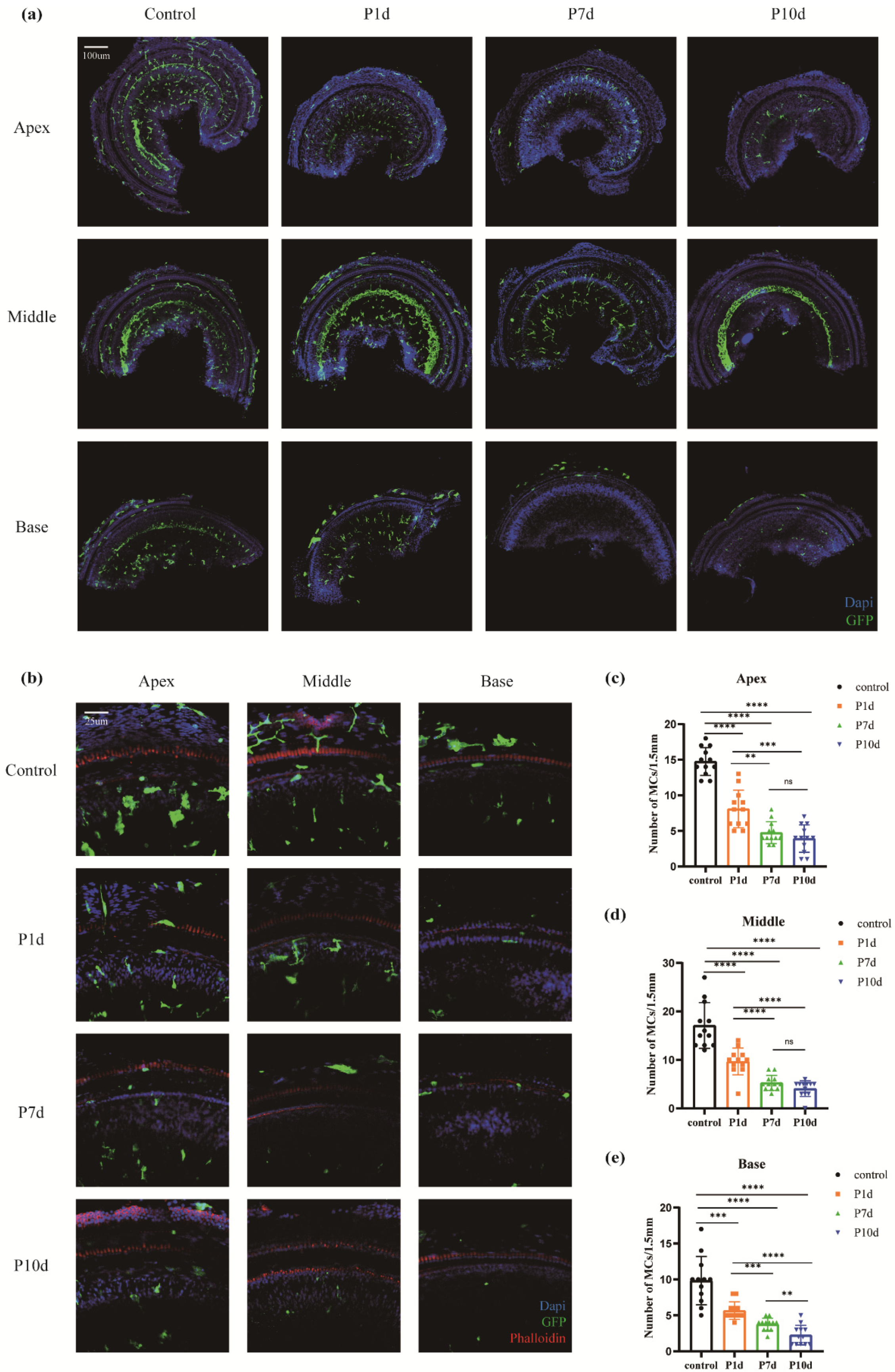

Figure 2.

Macrophages in the basement membrane region gradually decline after exposure to ionizing radiation. (a) Macrophages in the whole segment of the cochlear membranous labyrinth of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation under a 10-fold laser confocal microscope (blue DAPI, green GFP, scale 200um). (b) Representative pictures of macrophages at the top, middle, and bottom of the cochlear membrane labyrinth of mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (40×, scale 50um). (c)-(e) Macrophage counts in the parietal, middle, and basal basement membrane regions of the cochlear membrane of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (n = 6 in each group).

Figure 2.

Macrophages in the basement membrane region gradually decline after exposure to ionizing radiation. (a) Macrophages in the whole segment of the cochlear membranous labyrinth of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation under a 10-fold laser confocal microscope (blue DAPI, green GFP, scale 200um). (b) Representative pictures of macrophages at the top, middle, and bottom of the cochlear membrane labyrinth of mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (40×, scale 50um). (c)-(e) Macrophage counts in the parietal, middle, and basal basement membrane regions of the cochlear membrane of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (n = 6 in each group).

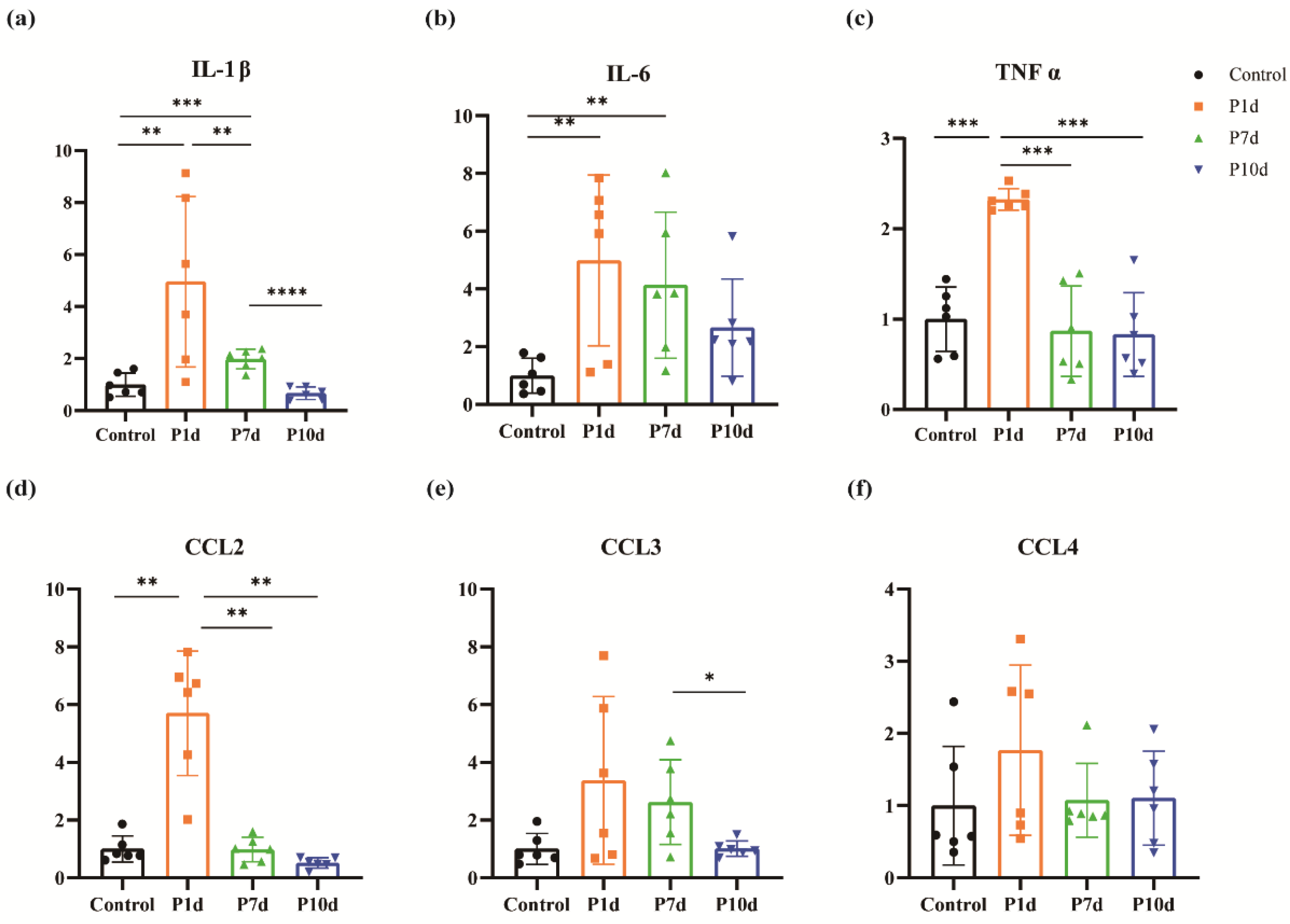

Figure 3.

Changes in inflammatory mediators in the inner ear following exposure to ionizing radiation. (a) Changes of IL-1β in the cochlea of mice in the control group and on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (b) Changes in IL-6 in the cochlea of mice in the control group and at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (c) Changes of TNFα in the cochlea of mice in the control group and on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (d) Changes in CCL2 in the cochlea of mice in the control group and on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (e) Changes in cochlear CCL3 at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in the control and study groups. (f) Changes in cochlear CCL4 at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in the control group and in the study groups. (n = 6 in each group).

Figure 3.

Changes in inflammatory mediators in the inner ear following exposure to ionizing radiation. (a) Changes of IL-1β in the cochlea of mice in the control group and on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (b) Changes in IL-6 in the cochlea of mice in the control group and at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (c) Changes of TNFα in the cochlea of mice in the control group and on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (d) Changes in CCL2 in the cochlea of mice in the control group and on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (e) Changes in cochlear CCL3 at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in the control and study groups. (f) Changes in cochlear CCL4 at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in the control group and in the study groups. (n = 6 in each group).

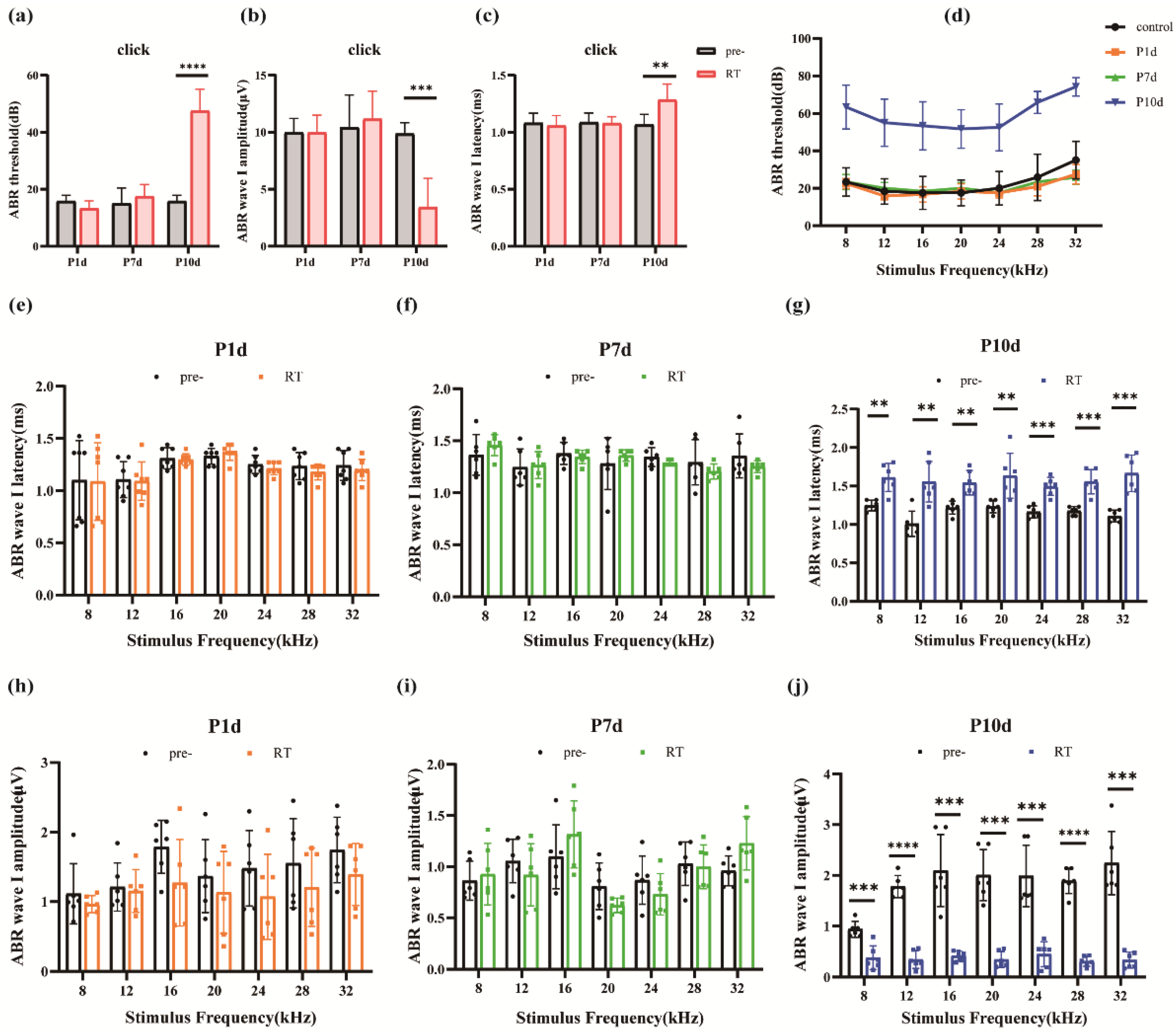

Figure 4.

Effects of ionizing radiation exposure on ABR hearing in mice. (a)-(c) Changes in click threshold, I-wave amplitude, and I-wave delay for mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (d) Variations of the ABR threshold at different frequencies in mice on days 1, 7, and 10 after irradiation. (e)-(g). Changes in the latency of the I-wave at different frequencies on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in mice. (h)-(j) I-wave amplitude variations at different frequencies on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in mice. (n = 6 in each group).

Figure 4.

Effects of ionizing radiation exposure on ABR hearing in mice. (a)-(c) Changes in click threshold, I-wave amplitude, and I-wave delay for mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation. (d) Variations of the ABR threshold at different frequencies in mice on days 1, 7, and 10 after irradiation. (e)-(g). Changes in the latency of the I-wave at different frequencies on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in mice. (h)-(j) I-wave amplitude variations at different frequencies on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation in mice. (n = 6 in each group).

Figure 5.

Ear hair cells were not damaged during the acute period of ionizing radiation. (a) Hair cells in all segments of the cochlear membranous labyrinth of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation under a 10-fold laser confocal microscope (blue DAPI, red phalloidin, scale 200um). (b) Representative pictures of the top, middle, and bottom hair cells of the cochlear membrane of mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (40×, scale 50um). (c)-(e) The survival rate of outer hair cells of the apex, middle, and base of the cochlear membrane of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (n = 6 in each group).

Figure 5.

Ear hair cells were not damaged during the acute period of ionizing radiation. (a) Hair cells in all segments of the cochlear membranous labyrinth of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation under a 10-fold laser confocal microscope (blue DAPI, red phalloidin, scale 200um). (b) Representative pictures of the top, middle, and bottom hair cells of the cochlear membrane of mice on day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (40×, scale 50um). (c)-(e) The survival rate of outer hair cells of the apex, middle, and base of the cochlear membrane of mice at day 1st, day 7th, and day 10th after irradiation (n = 6 in each group).

Figure 6.

HE staining of cochlear slices. (a) Cochlear of the control group under 10x objective view. (b) Cochlear from the P10d group under an objective view of 10x. (c) Cochlear spiral ganglion cells of the control group under an objective view of 100x. (d) Cochlear spiral ganglion cells of the P10d group under 100x objective view.

Figure 6.

HE staining of cochlear slices. (a) Cochlear of the control group under 10x objective view. (b) Cochlear from the P10d group under an objective view of 10x. (c) Cochlear spiral ganglion cells of the control group under an objective view of 100x. (d) Cochlear spiral ganglion cells of the P10d group under 100x objective view.

Figure 7.

Cochlear neurofilament immunofluorescence staining. Immunofluorescence labeling of neurofilament protein in cochlear spiral ganglion region of the control group and P10d group at 40 × magnification. White: neurofilament; Red: phalloidin.

Figure 7.

Cochlear neurofilament immunofluorescence staining. Immunofluorescence labeling of neurofilament protein in cochlear spiral ganglion region of the control group and P10d group at 40 × magnification. White: neurofilament; Red: phalloidin.