Submitted:

18 January 2024

Posted:

19 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Foundation Engineering in the Permafrost Regions of Northern Canada

2.1. Existing Guides to Foundation Practice in Canadian Permafrost

2.2. Thermosyphon Method

2.3. Spread Footings

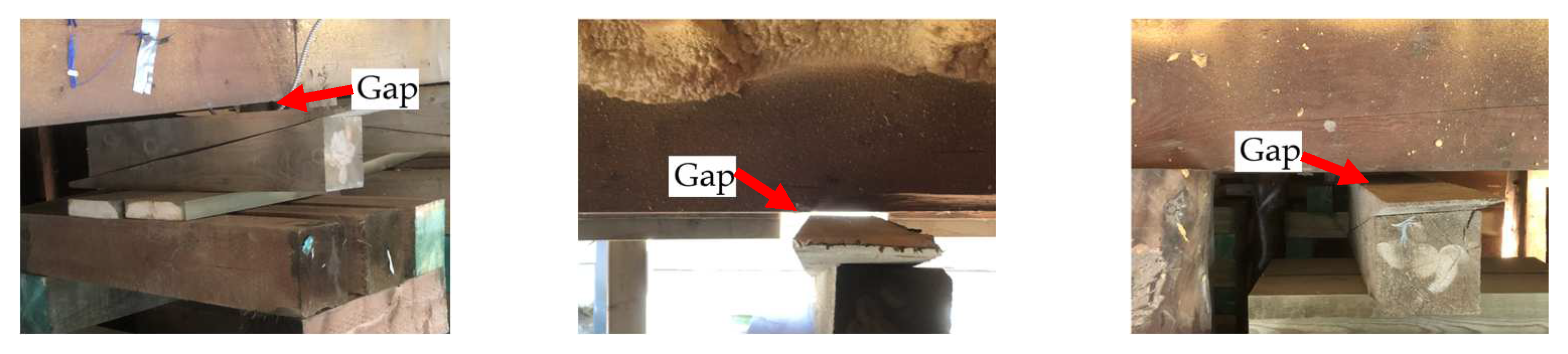

2.4. Wood Blocking Method

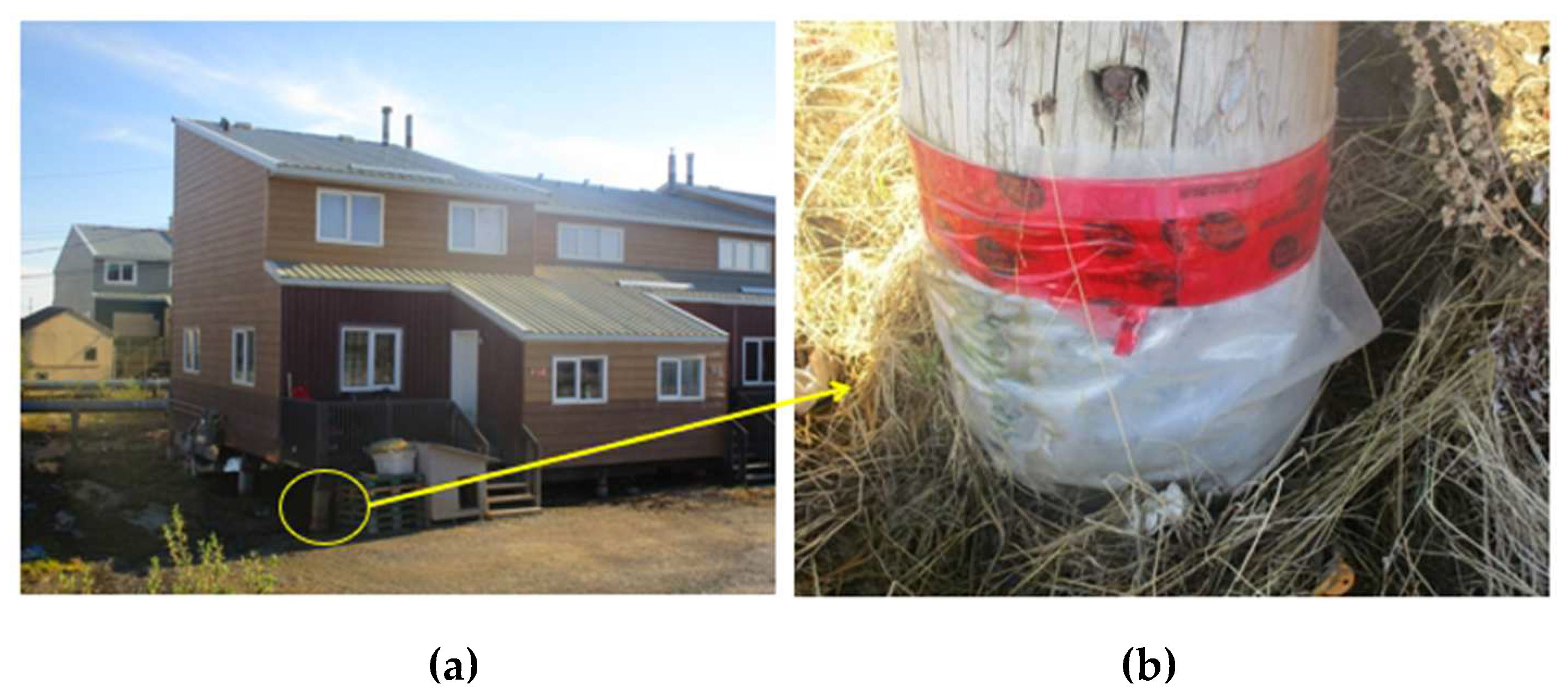

2.5. Jack Pads

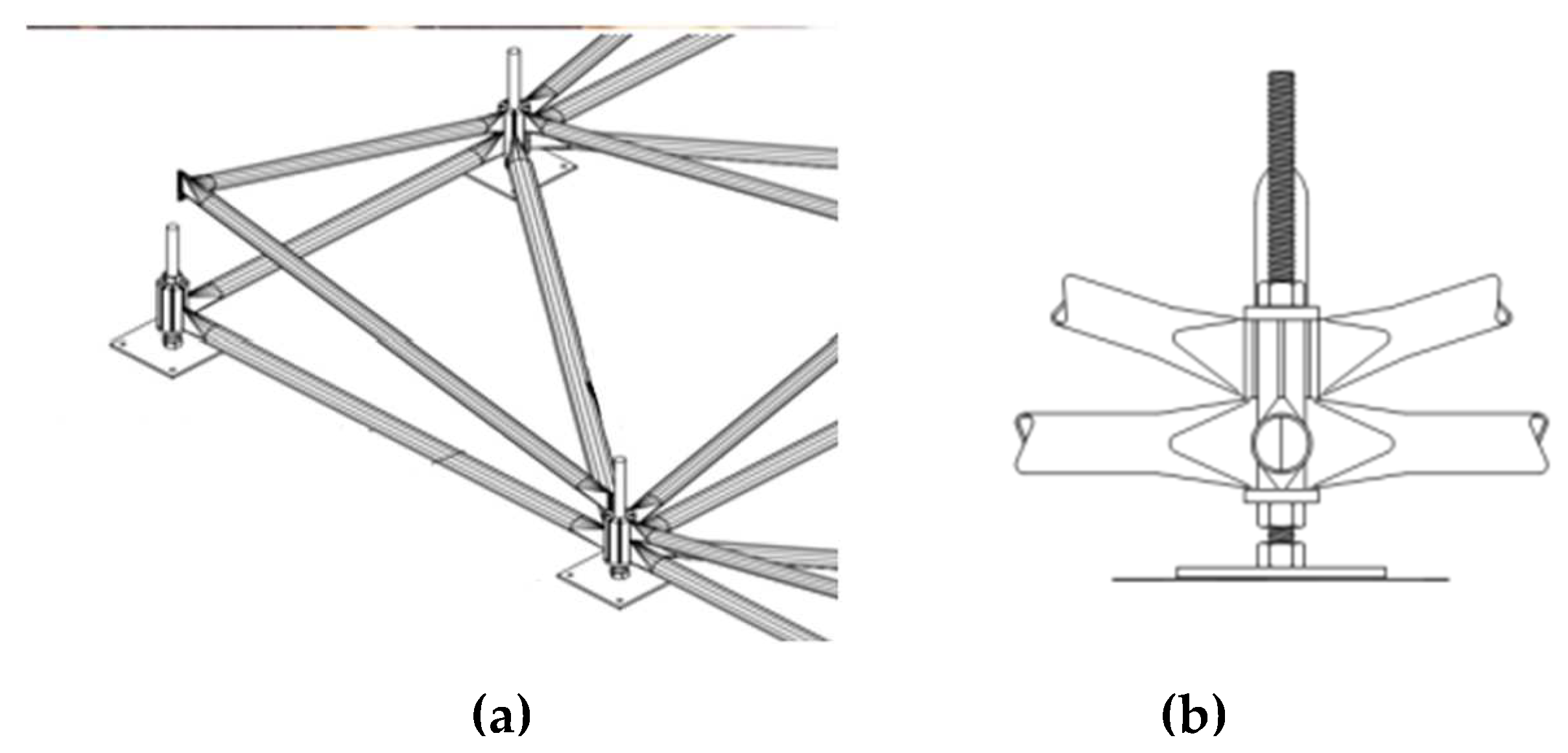

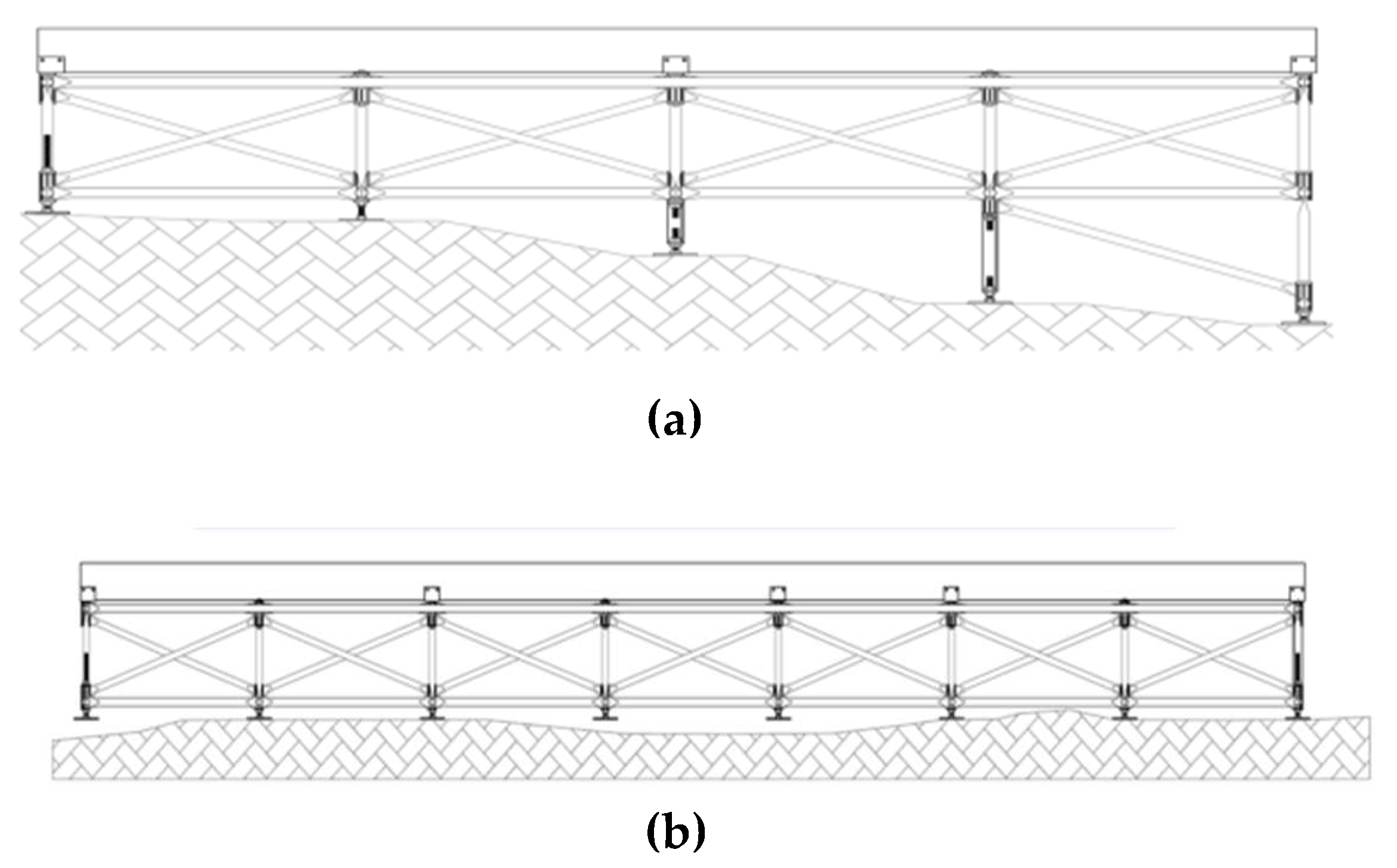

2.6. Space Frame System

2.7. Timber Piles

2.8. Steel Pipe Piles

2.9. Screw Piles

3. Findings from Interviewing Arctic Foundations Professionals

3.1. Interview questions and response

- What is the major concern regarding foundations in permafrost?

- 2.

- What are the challenges regarding logistics in the construction of a foundation in permafrost?

- 3.

- What are common techniques used to reduce the frost-heave effect?

- 4.

- What is the efficacy of convection systems such as thermopiles?

- 5.

- What are the common foundations for residential constructions?

- 6.

- What is the difference in cost between shallow foundations and pile foundations for residential constructions?

- 7.

- Do all foundations in permafrost need to be designed by geotechnical engineers?

- 8.

- Can screw piles be a good choice for residential construction?

- 9.

- Other comments made by the interviewees.

3.2. Summary of Interview

4. Design Manual and Case Study of Screw Piles and Steel Pipe Piles in Residential Foundations.

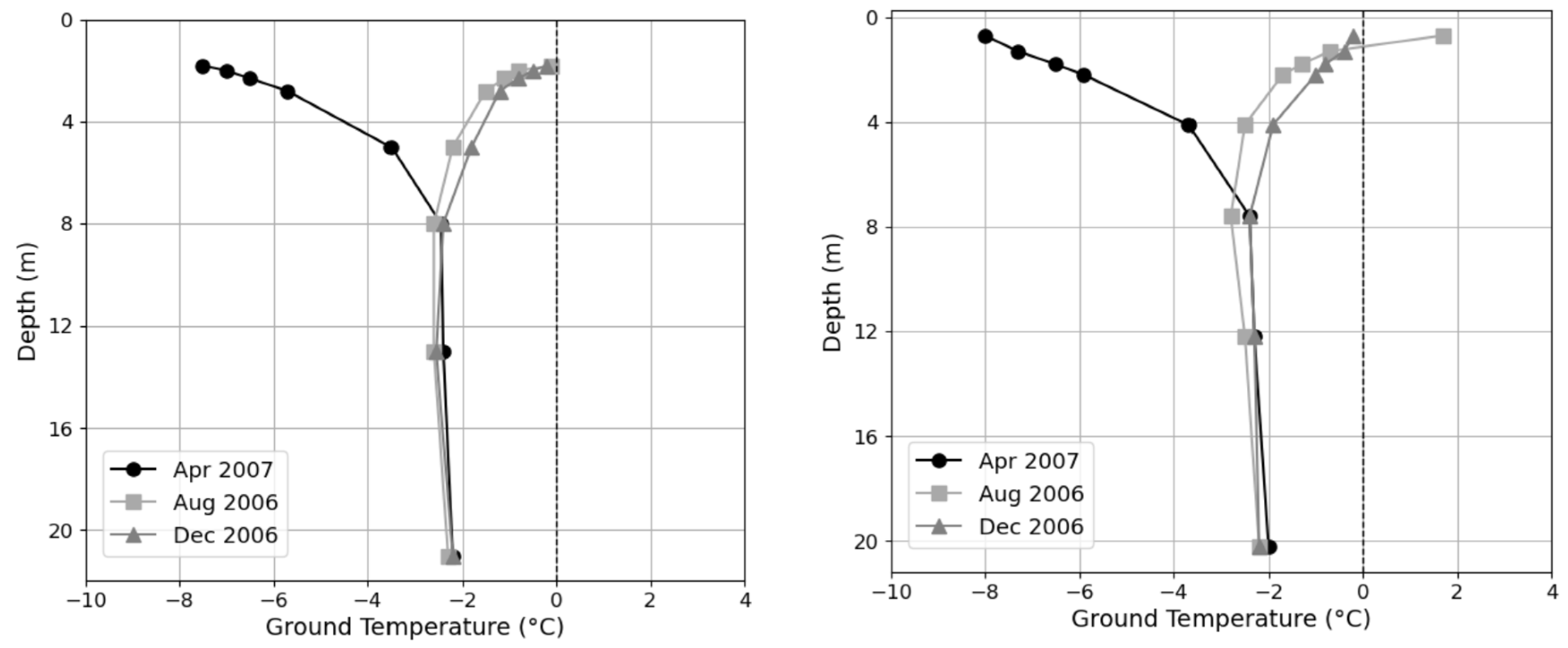

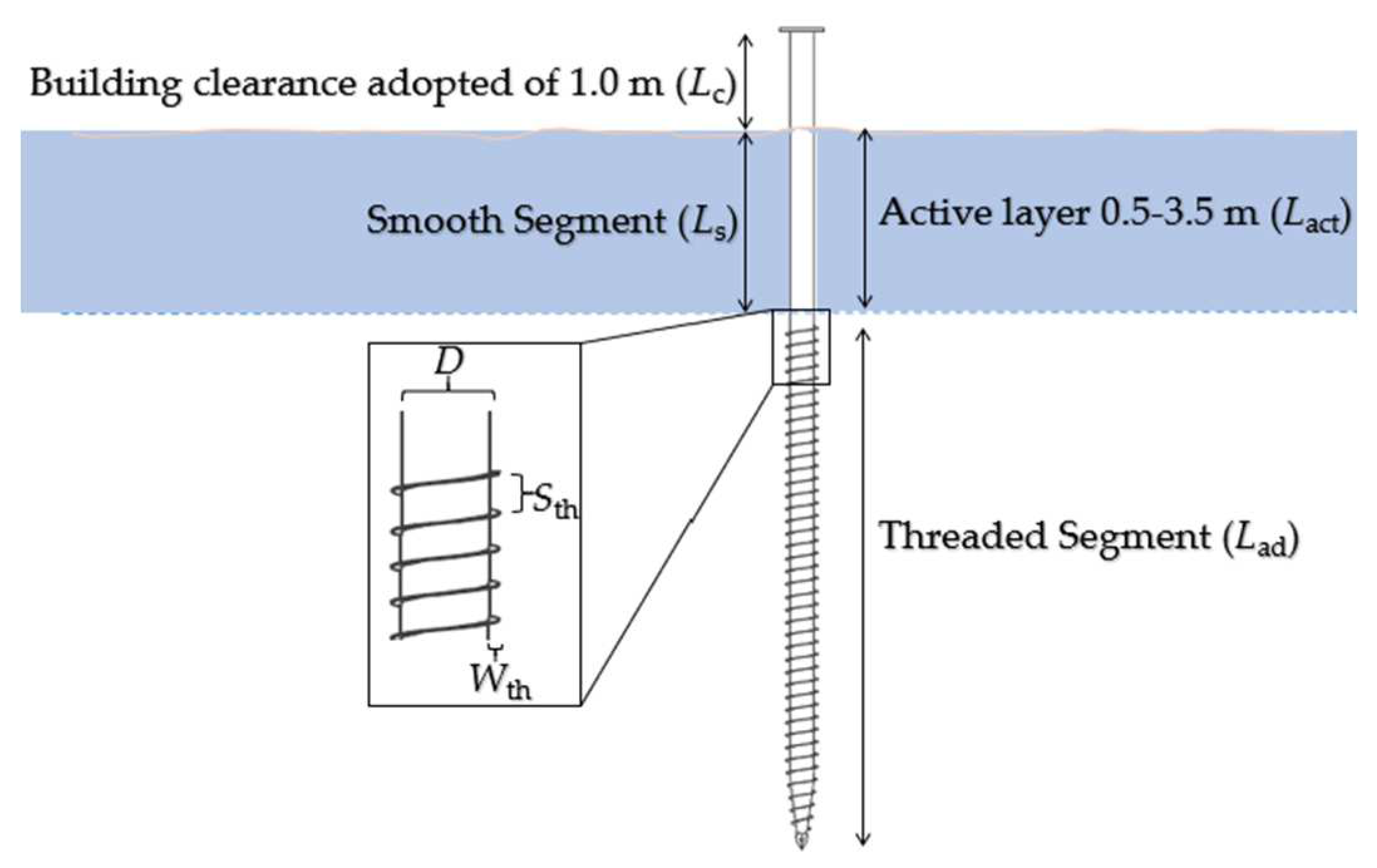

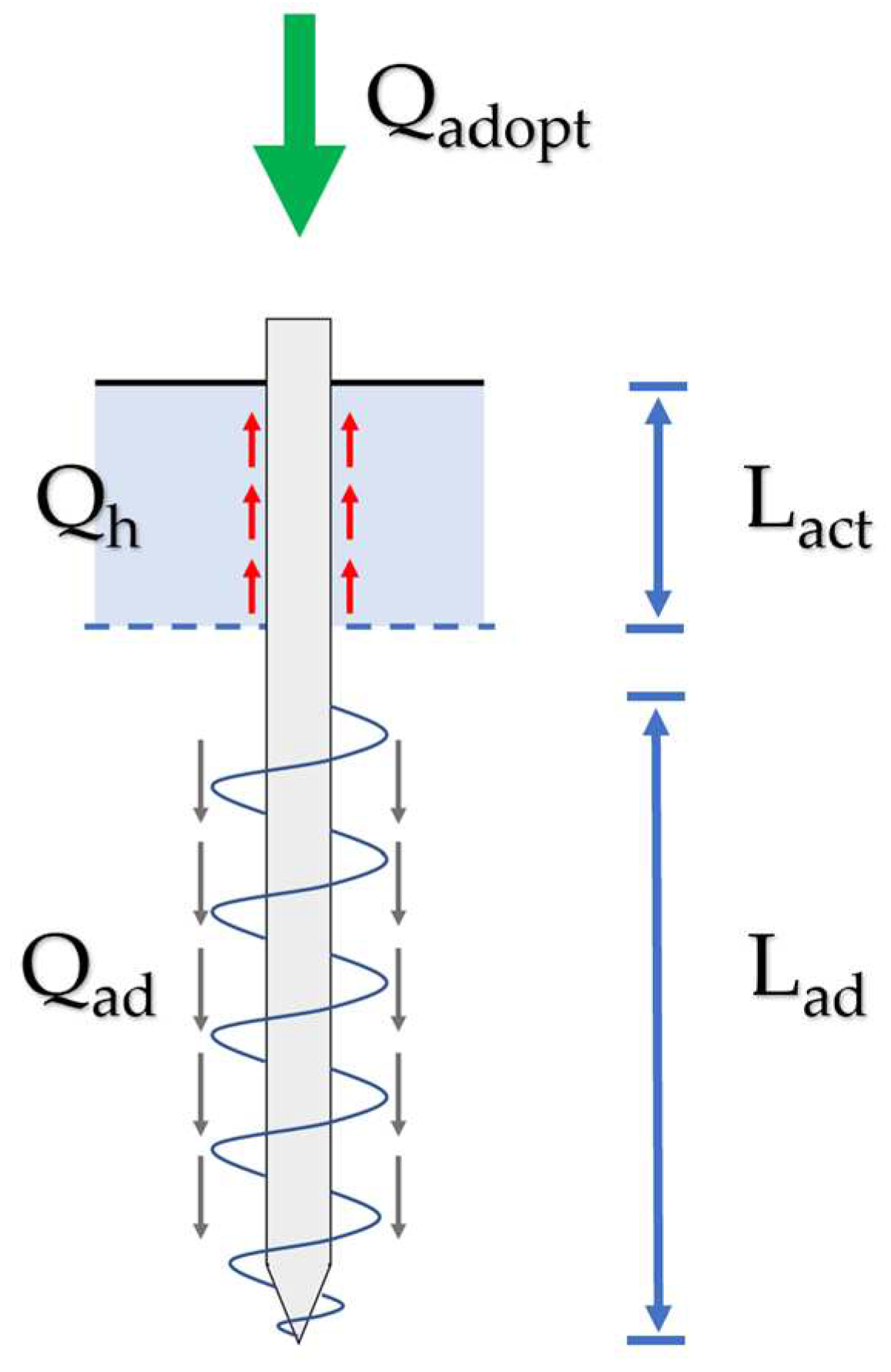

4.1. Loads, permafrost conditions, and piles

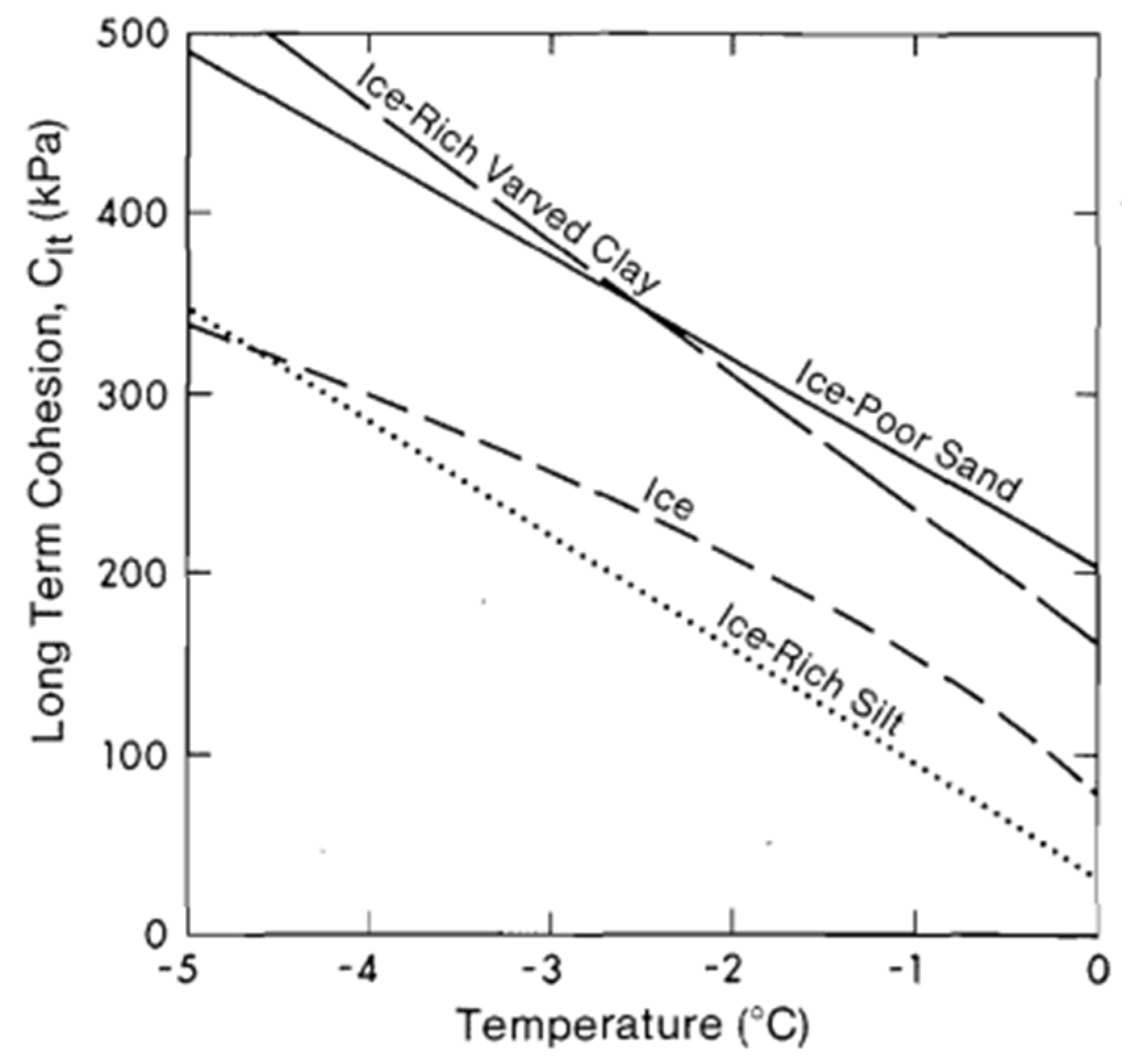

4.2. Design Criterion for Long-Term Adfreeze Strength

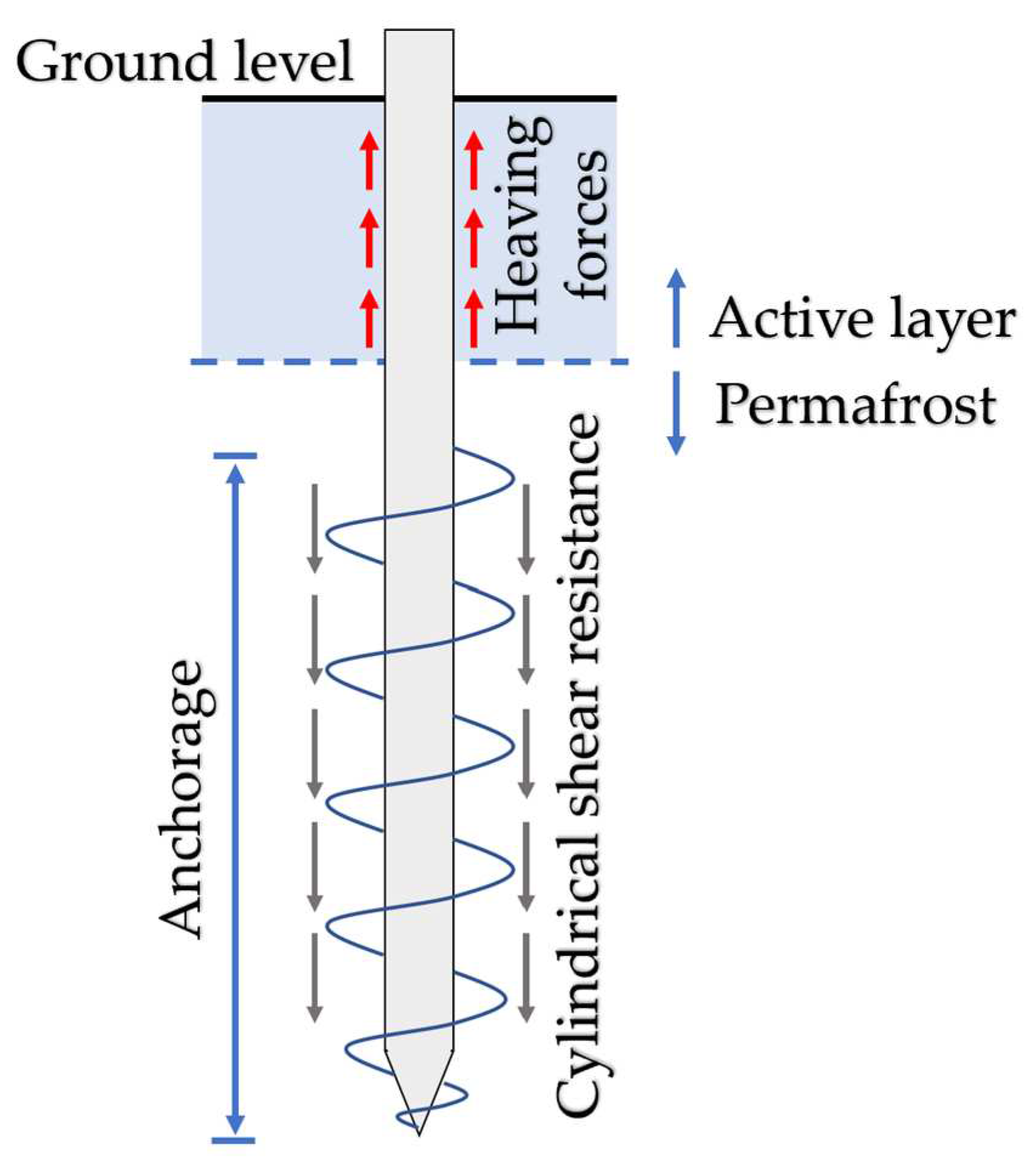

4.3. Design Criterion for Frost Heave

4.4. Design Criterion for Long-Term Creep Settlement

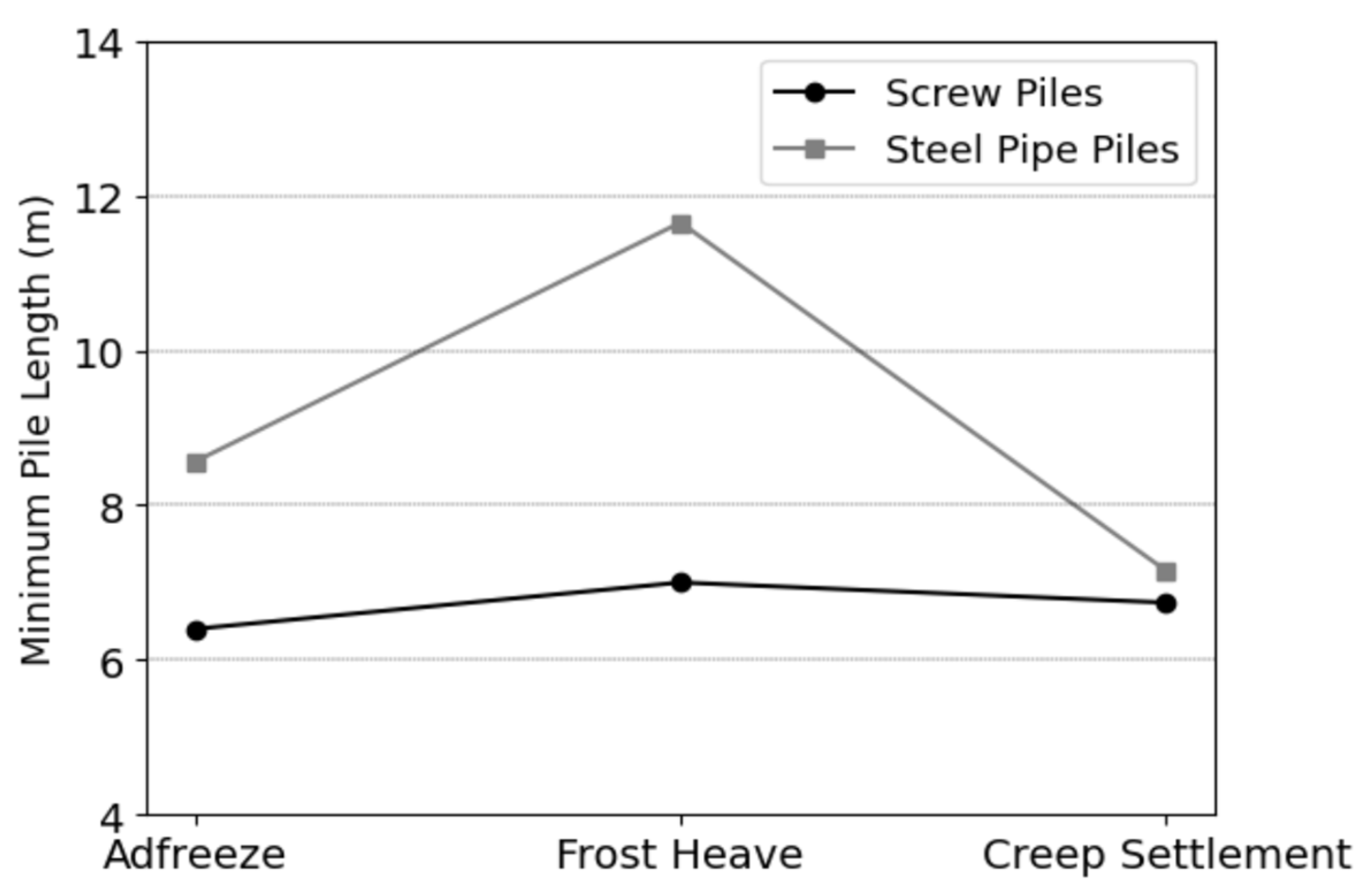

4.5. Results

6. Conclusions

- Various methods are being researched for maintaining soil integrity in both shallow foundations and piles. For example, anti-adhesion coatings can be used to protect piles and columns and reduce frost heave. While these methods show promise in theory, there are still relatively few studies that show their efficiency with actual foundations.

- It is unlikely that any technique can keep the soil completely frozen; however, it can at least maintain its temperature as low as possible, both in winter and summer, reducing the effect of frost action and increasing the adfreeze bond capacity between the soil and the foundation. Among all methods, thermosyphons appear to be indispensable.

- For smaller constructions with lower loads and shallow active layers, footings, and jack pads may be the best option. However, for larger and more complex structures, screw piles, steel pipe piles, and space frame systems may be necessary.

- For piles in permafrost in northern Canada, the design should consider the adfreeze strength (axial stability), frost heave (axial serviceability), and long-term creep settlement (axial serviceability). The examples of designing screw piles and steel pipe piles showed that screw piles may require a length of 7 m and the steel pipe pile requires a length of 12 m.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, R.J.E. Permafrost in Canada: Its Influence on Northern Development (Heritage), 1st ed.; University of Toronto Press, 1970; ISBN 978-0-8020-1602-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shur, Y.; Goering, D. Climate Change and Foundations of Buildings in Permafrost Regions. In Permafrost Soils; 2009; Vol. 16, 251, 260, ISBN 978-3-540-69370-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Riseborough, D.W. Disequilibrium Response of Permafrost Thaw to Climate Warming in Canada over 1850–2100. Geophysical Research Letters 2008, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streletskiy, D.A.; Suter, L.J.; Shiklomanov, N.I.; Porfiriev, B.N.; Eliseev, D.O. Assessment of Climate Change Impacts on Buildings, Structures and Infrastructure in the Russian Regions on Permafrost. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 025003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G.H. Pile Construction in Permafrost. In Proceedings of the Proceedings: Permafrost International Conference; Lafayette, Indiana; 1963; pp. 477–480. [Google Scholar]

- Crory, F.E. Piling in Frozen Ground. Journal of the Technical Councils of ASCE 1982, 108, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Geotechnical, Society. Canadian Foundation Engineering Manual (CFEM), 5th ed.Canadian Science Publishing: Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Standards Association, (CSA). Moderating the Effects of Permafrost Degradation on Existing Building Foundations (No. CAN/CSA-S501-14); CSA Group: 2021; p. 55.

- Canadian Standards Association, (CSA). Design and Construction Considerations for Foundations in Permafrost Regions. No. CSA PLUS 4011.1:19; CSA Group, 2019; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau de Normalisation du Québec, (BNQ). Geotechnical Site Investigations for Building Foundations in Permafrost Zones (No. CAN/BNQ 2501-500/2017); National Standard of Canada: 2017; p. 104.

- Government of the Northwest, Territories. Good Building Practice for Northern Facilities, 4th ed.; Government of Northwest Territories, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Hoeve, E. Geotechnical Design of Thermopile Foundation for a Building in Inuvik.; GeoQuebec: Quebec, Québec, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A. Review of Thermosyphon Applications (No. ERDC/CRREL-TR-14-1); Engineer Research and Development Center, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory: 2014; pp. 1–37.

- McRoberts, E.C. Shallow Foundations in Cold Regions: Design. Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division 1982, 108, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, P.; Shur, Y. Seasonal Thermal Insulation to Mitigate Climate Change Impacts on Foundations in Permafrost Regions. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2016, 132, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, T. Design Manual for Stabilizing Foundations on Permafrost; Permafrost Technology Foundation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, G.H. Permafrost: Engineering Design and Construction; Wiley: 1981; ISBN 978-0-471-79918-4.

- Pruys, S. Pingos Growing under Inuvik’s Hospital Pose Costly Problem. Available online: https://cabinradio.ca/69485/news/beaufort-delta/pingos-growing-under-inuviks-hospital-pose-costly-problem/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Liu, C.; Anderson, R.; Gopie, N.; Deng, L. Field Performance of Wood Blocking Method for Remediating a Building in the Canadian Arctic. Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring 2022, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M. How Floor Repair of Inuvik’s “igloo Church” Could Offer Deeper Look into North’s Permafrost Available online:. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/inuvik-igloo-church-repair-learn-permafrost-north-1.6184155 (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Vangool, W.J. 2018. Mechanical Foundation System for New and Retrofit Construction. Building Tomorrow’s Society, (20): 1–9.; Building Tomorrow’s Society: Fredericton, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vangool, W.J. Foundations for Retrofit and New Construction in Permafrost, Discontinuous Permafrost, and Other Problem Soil Areas By.; ASCE American Society of Civil Engineers: Salt Lake City, Utah, 2015; pp. 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Nottingham, D.; Christopherson, A.B. Design Criteria for Driven Piles in Permafrost (No. AK-RD-83-19); Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities: Fairbanks, Alaska, 1983; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Aldaeef, A.A.; Rayhani, M.T. Interface Shear Strength Characteristics of Steel Piles in Frozen Clay under Varying Exposure Temperature. Soils and Foundations 2019, 59, 2110–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crory, F.E.; Reed, R.E. Measurement of Frost Heaving Forces on Piles (No. 145); Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory: 1965; p. 145.

- Zarling, J.P.; Haynes, F.D. Thermosiphon-Based Designs and Applications for Foundations Built on Permafrost; OnePetro, 29 May 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Yarmak, E. Permafrost Foundations Thermally Stabilized Using Thermosyphons.; 2015. 23 March.

- Wang, T.; Liu, J.; Tian, Y.; Lv, P. Frost Jacking Characteristics of Screw Piles by Model Testing. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2017, 138, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, J.; Luo, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Qi, W. Calculation for Frost Jacking Resistance of Single Helical Steel Piles in Cohesive Soils. Journal of Cold Regions Engineering 2021, 35, 06021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanigan, J.C.N.; Burn, C.R.; Kokelj, S.V. Ground Temperatures in Permafrost South of Treeline, Mackenzie Delta, Northwest Territories. Permafrost & Periglacial 2009, 20, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khidri, M.; Deng, L. Field Axial Loading Tests of Screw Micropiles in Sand. Can. Geotech. J. 2022, 59, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Khidri, M.; Deng, L. Field Loading Tests of Screw Micropiles under Axial Cyclic and Monotonic Loads. Acta Geotech. 2019, 14, 1843–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khidri, M.; Deng, L. Field Axial Cyclic Loading Tests of Screw Micropiles in Cohesionless Soil. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 2021, 143, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Sego, D.; Deng, L. Long-Term Axial Performance of Continuous-Flight Pile in Frozen Soil. Can. Geotech. J. 2023, 60, 1835–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Sego, D.; Deng, L. Short-Term Axial Loading of Continuous-Flight Pile Segment in Frozen Soil. Can. Geotech. J. 2023, 60, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.; Morgenstern, N. Pile Design in Permafrost. Canadian Geotechnical Journal 1981, 18, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialov, S.S. Rheological Properties and Bearing Capacity of Frozen Soils (Rheologicheskie Svoistva I Nesushchaia Sposobnost’ Merzlykh Gruntov) (No. Translation 74,219 PP); Terrestrial Sciences Center: Army /US, 1965; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Voitkovskii, K.F. The Mechanical Properties of Ice. Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian) (No. Trans. AMS-T-R391); American Meteorological Society, Office of Technical Services: US Department of Commerce, Washington, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, G.; Ladanyi, B. Field Tests of Grouted Rod Anchors in Permafrost. Can. Geotech. J. 1972, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, K.; Thorsten, R. Load Test Results — Large Diameter Helical Pipe Piles.; 2009; pp. 488–495. 10 March.

- Mohajerani, A.; Bosnjak, D.; Bromwich, D. Analysis and Design Methods of Screw Piles: A Review. Soils and Foundations 2016, 56, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, J.F.; McRoberts, E.C. A Design Approach for Pile Foundations in Permafrost. Can. Geotech. J. 1976, 13, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soils Depth | Temperature changes (oC) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From 1850s to the 1990s | From 1990s to the 2090s | |||

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | ||

| 0 m | 1.6 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 7.0 |

| 0.2 m | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 5.1 |

| 2 m | 1.0 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 4.6 |

| 10 m | 0.8 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 3.9 |

| 40 m | 0.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 |

| Parameters | Footings | Jack Pads | Space Frame System | Timber Piles | Steel Pipe Piles | Screw Piles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Installation Methods | Trench excavation, concrete pouring, backfilling, reinforced steel | Assembly of prefabricated components | Assembly of prefabricated components | Hammering or driving piles into the ground | Excavation, driving or vibrating piles into the ground, grouting. | Screwing piles into the ground |

| Use of Heavy Equipment | Low | None | Low | High | High | Moderate |

| Load Capacity | Low | Low | High | Moderate | High | High |

| Soil Disturbance | High | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Vulnerability to Freeze-Thaw Instability | High | Low | Low | High | Moderate | Low |

| Reliability and Longevity | Moderate | Moderate | High Potential | Low | High Potential | High Potential |

| Differential Movement Between Supports | High Potential | Moderate | Low | High Potential | Moderate | Moderate |

| Material Availability and Shipping | High | High | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Availability of Qualified Contractors | High | High | Low | High | High | High |

| Building Type | Residential | Residential | Residential and Commercial | Residential and Commercial | Residential and Commercial | Residential and Commercial |

| Pile type | Parameters | Criterion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adfreeze | Frost Heave | Creep Settlement | ||

| Screw Pile | Average τad or τ required (kPa) | 140 | 140 | 43.5 |

| FS | 2 | 1.5 | Not applicable | |

| Steel Pipe Pile | Average τad or τ required (kPa) | 84 | 84 | 47.2 |

| FS | 2 | 2 | Not applicable | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).