Submitted:

16 January 2024

Posted:

17 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

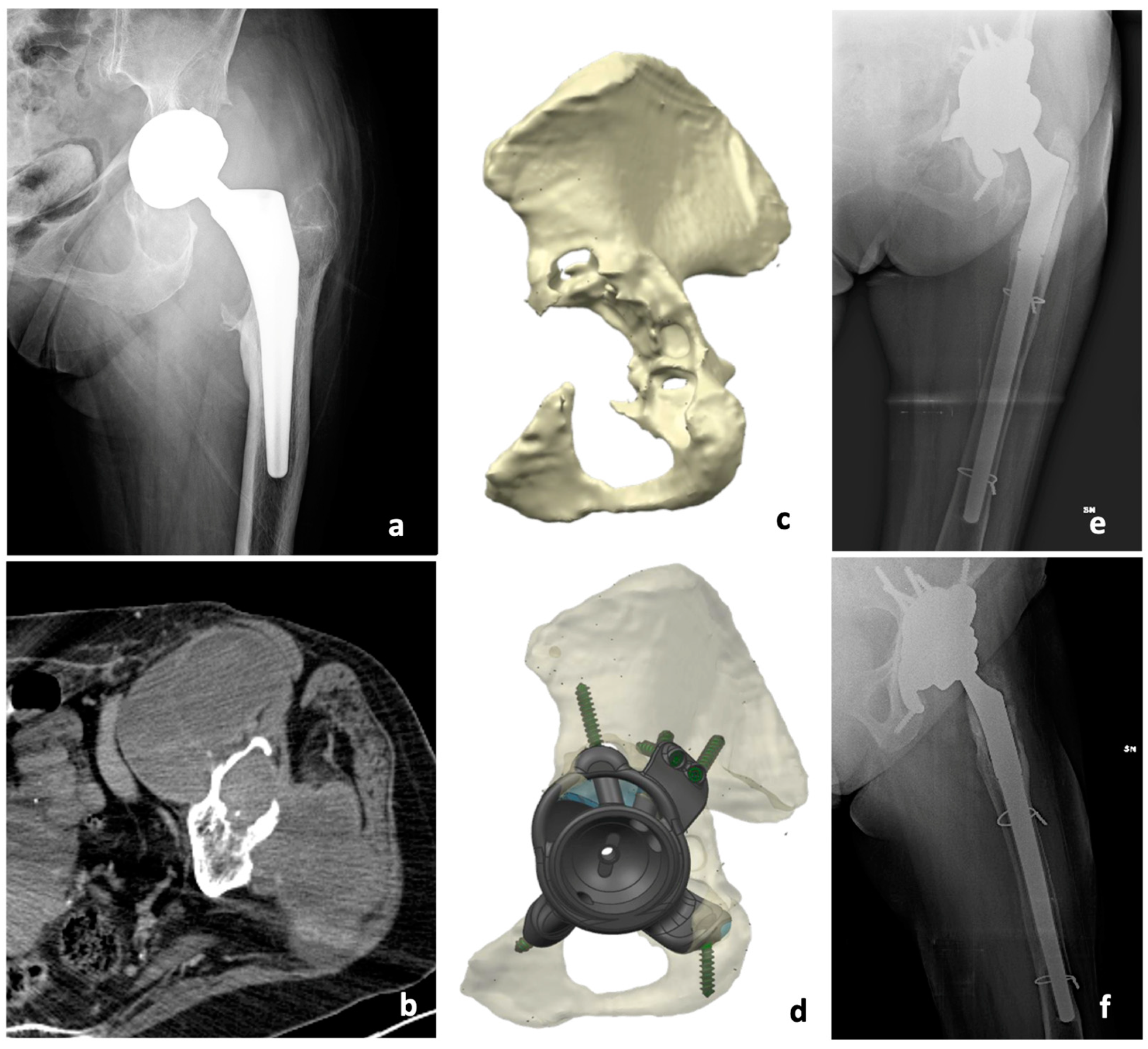

2.4. Imaging

2.5. Biopsy

2.6. Histology

2.7. Surgical Procedure

2.8. Post-Operative Protocol of Both Procedures

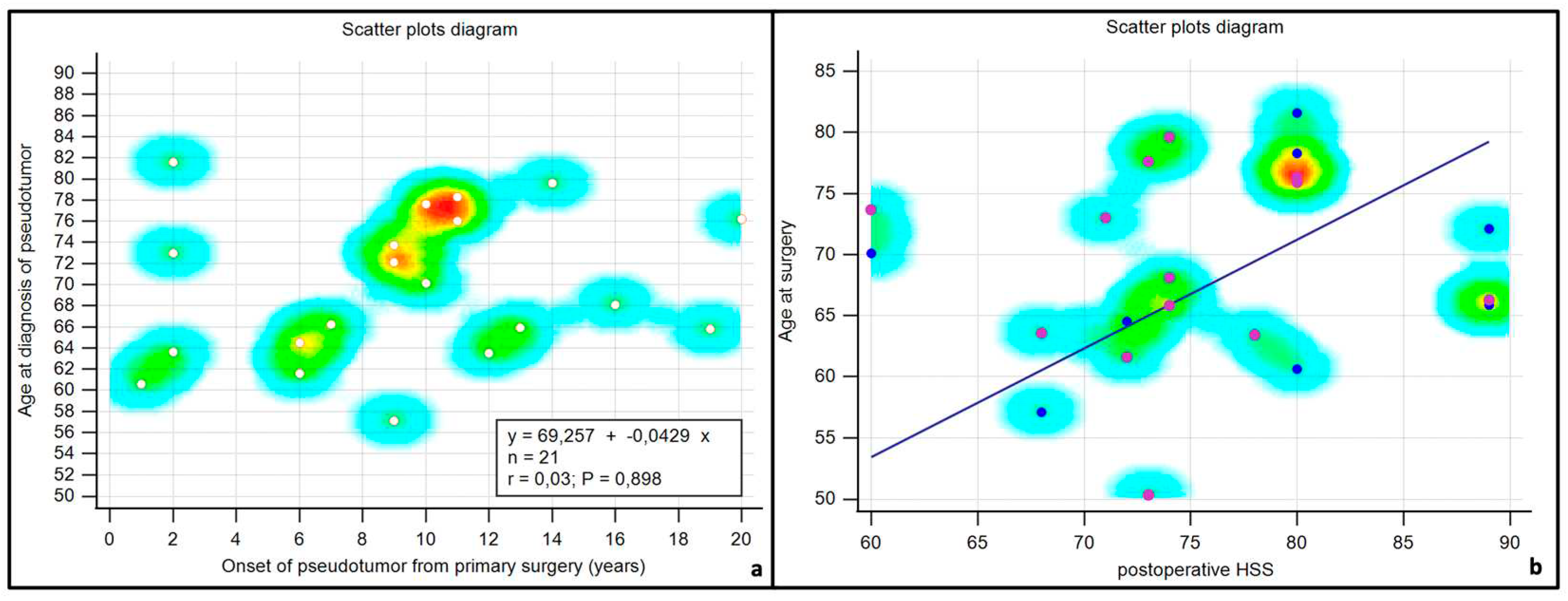

2.9. Clinical and radiographic evaluation

2.10. Complication

2.11. Statistical Analysis

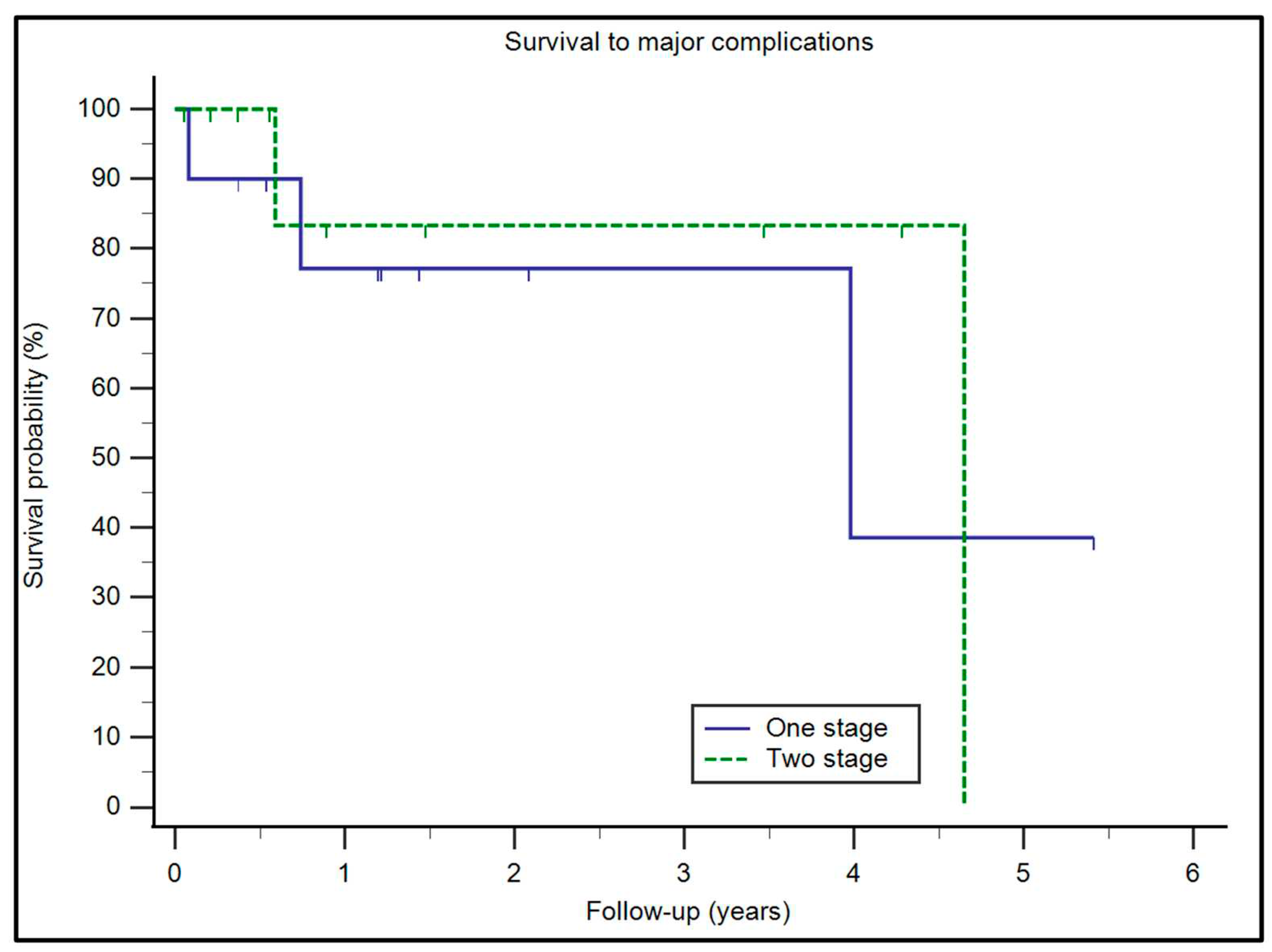

3. Results

3.1. Patients Data

3.2. Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grote, C.W.; Cowan, P.C.; Anderson, D.W.; Templeton, K.J. Pseudotumor from Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty Causing Unilateral Leg Edema: Case Presentation and Literature Review. BioResearch Open Access 2018, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradit Kremers, H.; Larson, D.R.; Crowson, C.S.; Kremers, W.K.; Washington, R.E.; Steiner, C.A.; Jiranek, W.A.; Berry, D.J. Prevalence of Total Hip and Knee Replacement in the United States: J. Bone Jt. Surg.-Am. Vol. 2015, 97, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.; Ong, K.; Lau, E.; Mowat, F.; Halpern, M. Projections of Primary and Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030: J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2007, 89, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Arora, G.N.C.; Datta, B. Bearing Surfaces in Hip Replacement - Evolution and Likely Future. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2014, 70, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mp, B.; Ck, L. Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty: Patient Evaluation and Treatment. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzuoli, A.; Berizzi, A.; Crimì, A.; Belluzzi, E.; Frigo, A.C.; Conti, G.D.; Nicolli, A.; Trevisan, A.; Biz, C.; Ruggieri, P. Metal Ion Release, Clinical and Radiological Outcomes in Large Diameter Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty at Long-Term Follow-Up. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2020, 10, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.L.; Morrison, J.J. Hip Arthroplasty Pseudotumors: Pathogenesis, Imaging, and Clinical Decision Making. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, P.; Shimmin, A.; Walter, L.; Solomon, M. Metal Sensitivity as a Cause of Groin Pain in Metal-on-Metal Hip Resurfacing. J. Arthroplasty 2008, 23, 1080–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lt, K.; D, G.; Tm, S.; Jg, M.; De, A.; Ss, W.; Mp, B. Association Between Pseudotumor Formation and Patient Factors in Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty Population. J. Arthroplasty 2018, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filer, J.L.; Berstock, J.; Hughes-Roberts, Y.; Foote, J.; Sandhu, H. Haemorrhagic Pseudotumour Following Metal-on-Metal Hip Replacement. Cureus 2021, 13, e15541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, K.F.; Ding, K.; Stoner, J.A.; Teague, D.C.; Yousuf, K.M. Incidence of Pseudotumor and Acute Lymphocytic Vasculitis Associated Lesion (ALVAL) Reactions in Metal-On-Metal Hip Articulations: A Meta-Analysis. J. Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, Y.M.; Meyers, A.J.; Giordani, M.; Meehan, J.P. Pseudotumor in Ceramic-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty. Arthroplasty Today 2017, 3, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, A.; Trovarelli, G.; Berizzi, A.; Pala, E.; Breda, A.; Ruggieri, P. Three-Dimension-Printed Custom-Made Prosthetic Reconstructions: From Revision Surgery to Oncologic Reconstructions. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A, A.; D, K.; G, T.; A, S.; A, B.; P, R. Analysis of Principles Inspiring Design of Three-Dimensional-Printed Custom-Made Prostheses in Two Referral Centres. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrych, D.; Angelini, A.; Bohatyrewicz, A.; Ruggieri, P. 3D Printing for Patient-Specific Implants in Musculoskeletal Oncology. EFORT Open Rev. 2023, 8, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggieri, P.; Cerchiaro, M.; Angelini, A. Multidisciplinary Approach in Patients with Metastatic Fractures and Oligometastases. Injury 2023, 54, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottino, U.; Dettoni, F.; Risitano, S.; Marmotti, A.; Rossi, R. Two-Stage Treatment of a Large Pelvic Cystic Pseudotumor in a Metal-On-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty. Joints 2017, 5, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padulo, J.; Oliva, F.; Frizziero, A.; Maffulli, N. Muscle, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic Principles and Recommendations in Clinical and Field Science Research. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013, 3, 250–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hauptfleisch, J.; Pandit, H.; Grammatopoulos, G.; Gill, H.S.; Murray, D.W.; Ostlere, S. A MRI Classification of Periprosthetic Soft Tissue Masses (Pseudotumours) Associated with Metal-on-Metal Resurfacing Hip Arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol. 2012, 41, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, M.B.; Taljanovic, M.S.; Stubbs, A.Y.; Graham, A.R.; Holden, D.A.; Hunter, T.B.; Rogers, L.F. Imaging of Musculoskeletal Soft Tissue Infections. Skeletal Radiol. 2010, 39, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, A.; Reuven, A.; Zukor, D.J.; Antoniou, J. Adverse Soft-Tissue Reactions around Non-Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty - a Systematic Review of the Literature. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2011, 69 Suppl 1, S47-51. [Google Scholar]

- Liow, M.H.L.; Kwon, Y.-M. Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty: Risk Factors for Pseudotumours and Clinical Systematic Evaluation. Int. Orthop. 2017, 41, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willert, H.-G.; Buchhorn, G.H.; Fayyazi, A.; Flury, R.; Windler, M.; Köster, G.; Lohmann, C.H. Metal-on-Metal Bearings and Hypersensitivity in Patients with Artificial Hip Joints. A Clinical and Histomorphological Study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2005, 87, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Li, H.; Huang, X.; Jie, S.; Zhu, W.; Pan, J.; Wu, X.; Mao, X. Both Acetabular and Femoral Reconstructions With Impaction Bone Grafting in Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty: Case Series and Literature Review. Arthroplasty Today 2023, 24, 101160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomed, N.N.; Arndt, D.C.; McGrory, B.J.; Harris, W.H. The Harris Hip Score: Comparison of Patient Self-Report with Surgeon Assessment. J. Arthroplasty 2001, 16, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, E.; Henderson, E.R.; Calabrò, T.; Angelini, A.; Abati, C.N.; Trovarelli, G.; Ruggieri, P. Survival of Current Production Tumor Endoprostheses: Complications, Functional Results, and a Comparative Statistical Analysis. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 108, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, E.R.; Groundland, J.S.; Pala, E.; Dennis, J.A.; Wooten, R.; Cheong, D.; Windhager, R.; Kotz, R.I.; Mercuri, M.; Funovics, P.T.; et al. Failure Mode Classification for Tumor Endoprostheses: Retrospective Review of Five Institutions and a Literature Review. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2011, 93, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958, 53, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogenis, A.F.; Rimondi, E.; Rossi, G.; Calabrò, T.; Ruggieri, P. CT-Guided Biopsy for Musculoskeletal Lesions. Orthopedics 2013, 36, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelini, A.; Biz, C.; Cerchiaro, M.; Longhi, V.; Ruggieri, P. Malignant Bone and Soft Tissue Lesions of the Foot. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, M.; Iino, T.; Sudo, A. Immune Response in Adverse Reactions to Metal Debris Following Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, L.G.; Shon, W.Y.; Clarke, I.C.; Moon, J.-G.; Mukund, P.; Kim, S.-M. Pseudotumor and Subsequent Implant Loosening as a Complication of Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty with Ceramic-on-Metal Bearing: A Case Report. Hip Pelvis 2018, 30, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, G.H.; Brockett, C.; Breckon, A.; van der Jagt, D.; Williams, S.; Hardaker, C.; Fisher, J.; Schepers, A. Ceramic-on-Metal Bearings in Total Hip Replacement: Whole Blood Metal Ion Levels and Analysis of Retrieved Components. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2009, 91, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer-Ertl, W.; Friesenbichler, J.; Liegl-Atzwanger, B.; Kuerzl, G.; Windhager, R.; Leithner, A. Noninflammatory Pseudotumor Simulating Venous Thrombosis after Metal-on-Metal Hip Resurfacing. Orthopedics 2011, 34, e678-681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, D.J.; Wood, S.N.; Chick, C.M.; Lewis, P.; Rashid, M.H.; Evans, A.R. Common Femoral Vein Thrombosis Caused by a Metal-on-Metal Hip Arthroplasty-Related Pseudotumor. J. Arthroplasty 2012, 27, 1581.e9–1581.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, A.D.; Huk, O.L.; Pelmus, M. Metallosis-Induced Iliopsoas Bursal Cyst Causing Venous Obstruction and Lower-Limb Swelling after Metal-on-Metal THA. Orthopedics 2012, 35, e1811-1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.R.; Galbraith, J.G.; Harty, J.A.; Gul, R. Inflammatory Pseudotumor Causing Deep Vein Thrombosis after Metal-on-Metal Hip Resurfacing Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 197.e9-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakita, K.; Shibanuma, N.; Tei, K.; Nishiyama, T.; Kuroda, R.; Kurosaka, M. Leg Edema Due to a Mass in the Pelvis after a Large-Diameter Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 197.e1-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hamid, H.; Miles, J.; Carrington, R.W.J.; Hart, A.; Loh, A.; Skinner, J.A. Combined Vascular and Orthopaedic Approach for a Pseudotumor Causing Deep Vein Thrombosis after Metal-on-Metal Hip Resurfacing Arthroplasty. Case Rep. Orthop. 2015, 2015, 926263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ey, C.; Jl, M.; Jr, V.H.; S, S.; T, W.; A, G.; Cb, C. Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty: Do Symptoms Correlate with MR Imaging Findings? Radiology 2012, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosker, B.H.; Ettema, H.B.; Boomsma, M.F.; Kollen, B.J.; Maas, M.; Verheyen, C.C.P.M. High Incidence of Pseudotumour Formation after Large-Diameter Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Replacement: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2012, 94, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeekes, C.; Schouten, B.J.M.; Nix, M.; Ongkiehong, B.F.; Wolterbeek, R.; van der Wal, B.C.H.; Nelissen, R.G.H.H. Pseudotumor in Metal-on-Metal Hip Arthroplasty: A Comparison Study of Three Grading Systems with MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2018, 47, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-K.; Kim, Y.; Hwang, K.-T.; Yang, J.-H.; Ryu, J.-A.; Kim, Y.-H. Prevalence and Natural Course of Pseudotumours after Small-Head Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Minimum 18-Year Follow-up Study of a Previous Report. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101-B, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, G.M.; Learmonth, I.D.; Case, C.P. A Systematic Comparison of the Actual, Potential, and Theoretical Health Effects of Cobalt and Chromium Exposures from Industry and Surgical Implants. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2008, 38, 645–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, A.J.; Muirhead-Allwood, S.; Porter, M.; Matthies, A.; Ilo, K.; Maggiore, P.; Underwood, R.; Cann, P.; Cobb, J.; Skinner, J.A. Which Factors Determine the Wear Rate of Large-Diameter Metal-on-Metal Hip Replacements? Multivariate Analysis of Two Hundred and Seventy-Six Components. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2013, 95, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagoo, N.S.; Sharma, R.; Johnson, C.S.; Stephenson, K.; Aya, K.L. Pseudotumor in the Setting of Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasty. Cureus 2020, 12, e8255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco Rodríguez, R.; García Fontán, E.M.; Blanco Ramos, M.; Juaneda Magdalena Benavides, L.; Otero Lozano, D.; Moldes Rodriguez, M.; Cañizares Carretero, M.A. Inflammatory Pseudotumor and Myofibroblastic Inflammatory Tumor. Diagnostic Criteria and Prognostic Differences. Cirugia Espanola 2021, S0009-739X(21)00112-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, A.; Tiengo, C.; Sonda, R.; Berizzi, A.; Bassetto, F.; Ruggieri, P. One-Stage Soft Tissue Reconstruction Following Sarcoma Excision: A Personalized Multidisciplinary Approach Called “Orthoplasty. ” J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, A.; Piazza, M.; Pagliarini, E.; Trovarelli, G.; Spertino, A.; Ruggieri, P. The Orthopedic-Vascular Multidisciplinary Approach Improves Patient Safety in Surgery for Musculoskeletal Tumors: A Large-Volume Center Experience. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-H.; Chuang, C.-C.; Huang, C.-C.; Jung, S.-M.; Lee, C.-C. Diagnosis and Treatment of Inflammatory Pseudotumor with Lower Cranial Nerve Neuropathy by Endoscopic Endonasal Approach: A Systematic Review. Diagn. Basel Switz. 2022, 12, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Patients (n=21) |

|---|---|

| Age (at surgery) | 69 range (50-82) |

Sex

|

8 13 |

Tribology

|

7 11 2 1 |

| Time to revision | 10 (yrs) range (1-20) |

Prostheses

|

6 7 7 |

Reconstruction

|

10 10 1 |

Comorbidities

|

4 12 2 3 2 9 |

| Patients | Previous revision surgery | PAPROSKY classification ACETABULAR | PAPROSKY classification FEMUR | Pseudotumor SIZE (Axial-Lateral) cms | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (V.G.) | yes | I | IV | 8 x10 | One-stage |

| 2 (A.B.) | no | I | II | 2X2 | One-stage |

| 3 (G.I.) | no | II | I | 4x6 | One-stage |

| 4 (L.C.) | no | II | I | 5x6 | One-stage |

| 5 (M.F.) | yes | I | I | 5x5 | One-stage |

| 6 (L.P.) | no | III | III | 10x9 | Two-stage |

| 7 (L.V.) | yes | III | I | 10x7 | Two-stage |

| 8 (E.S.) | no | III | III | 9x10 | Two-stage |

| 9 (GB.M.) | yes | I | I | 6x7 | Excision only |

| 10 (A.I.) | yes | II | III | 12x15 | Two-stage |

| 11 (KM.V.) | yes | III | IV | 11x20 | One-stage |

| 12 (MA.M.) | no | II | II | 5x5 | One-stage |

| 13 (M.P.) | no | II | II | 10x17 | Two-stage |

| 14 (MG.G.) | yes | III | I | 10x9 | Two-stage |

| 15 (Z.L.) | no | I | III | 7x10 | Two-stage |

| 16(D.G.) | no | II | III | 7x10 | Two-stage |

| 17(F.S.) | no | II | I | 9x6 | One-stage |

| 18(A.F.) | no | II | II | 7x7 | Two-stage |

| 19(M.D.) | yes | III | I | 9x9 | Two-stage |

| 20(G.C.) | no | II | I | 5x8 | One-stage |

| 21(G.L.) | no | II | I | 9x10 | One-stage |

| Patient | HHS preoperative | HHS postoperative | Improvement HHS | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (V.G.) | 41 | 89 | 48 | |

| 2 (A.B.) | 45 | 60 | 15 | |

| 3 (G.I.) | 33 | 74 | 41 | |

| 4 (L.C.) | 25 | 71 | 46 | |

| 5 (M.F.) | 32 | 72 | 40 | |

| 6 (L.P.) | 42 | 80 | 38 | |

| 7 (L.V.) | 39 | 72 | 33 | |

| 8 (E.S.) | 42 | 74 | 32 | |

| 9 (GB.M.) | 43 | 80 | 37 | |

| 10 (A.I.) | 18 | 68 | 50 | |

| 11 (KM.V.) | 36 | 73 | 37 | |

| 12 (MA.M.) | 29 | 78 | 49 | |

| 13 (M.P.) | 27 | 73 | 46 | |

| 14 (MG.G.) | 36 | 80 | 44 | |

| 15 (Z.L.) | 25 | 60 | 35 | |

| 16(D.G.) | 25 | 68 | 43 | |

| 17(F.S.) | 33 | 74 | 41 | |

| 18(A.F.) | 36 | 80 | 44 | |

| 19(M.D.) | 41 | 89 | 48 | |

| 20(G.C.) | 41 | 89 | 48 | |

| 21(G.L.) | 39 | 80 | 41 | |

| Mean | 35 | 75 | 41 | P<0.0001 |

| Patient | Surgery | Tribology | Complications (according to Henderson) | Minor | Major |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (V.G.) | One-stage | MoP | IV | Deep infection | |

| 2 (A.B.) | One-stage | MoM | |||

| 3 (G.I.) | One-stage | MoP | |||

| 4 (L.C.) | One-stage | MoP | |||

| 5 (M.F.) | One-stage | MoP | |||

| 6 (L.P.) | Two-stage | MoP | |||

| 7 (L.V.) | Two-stage | MoP | IV | Deep infection | |

| 8 (E.S.) | Two-stage | MoM | |||

| 9 (GB.M.) | Excision only | MoP | |||

| 10 (A.I.) | Two-stage | MoP | I | Superficial infection | Death at 3 months |

| 11 (KM.V.) | One-stage | MoM | IV | Deep infection | |

| 12 (MA.M.) | One-stage | MoM | Death at 1 year | ||

| 13 (M.P.) | Two-stage | MoM | |||

| 14 (MG.G.) | Two-stage | CoP | |||

| 15 (Z.L.) | Two-stage | MoM | |||

| 16(D.G.) | Two-stage | MoM | I | Superficial infection | |

| 17(F.S.) | One-stage | MoP | |||

| 18(A.F.) | Two-stage | MoP | |||

| 19(M.D.) | Two-stage | MoP | I | Femoral nerve injury, sensosy deficit | |

| 20(G.C.) | One-stage | CoC | |||

| 21(G.L.) | One-stage | CoC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).