Submitted:

30 December 2023

Posted:

17 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Impact of Blockchain and Sustainability

2.2. Sustainability and Blockchain in the Pharmaceutical Industry

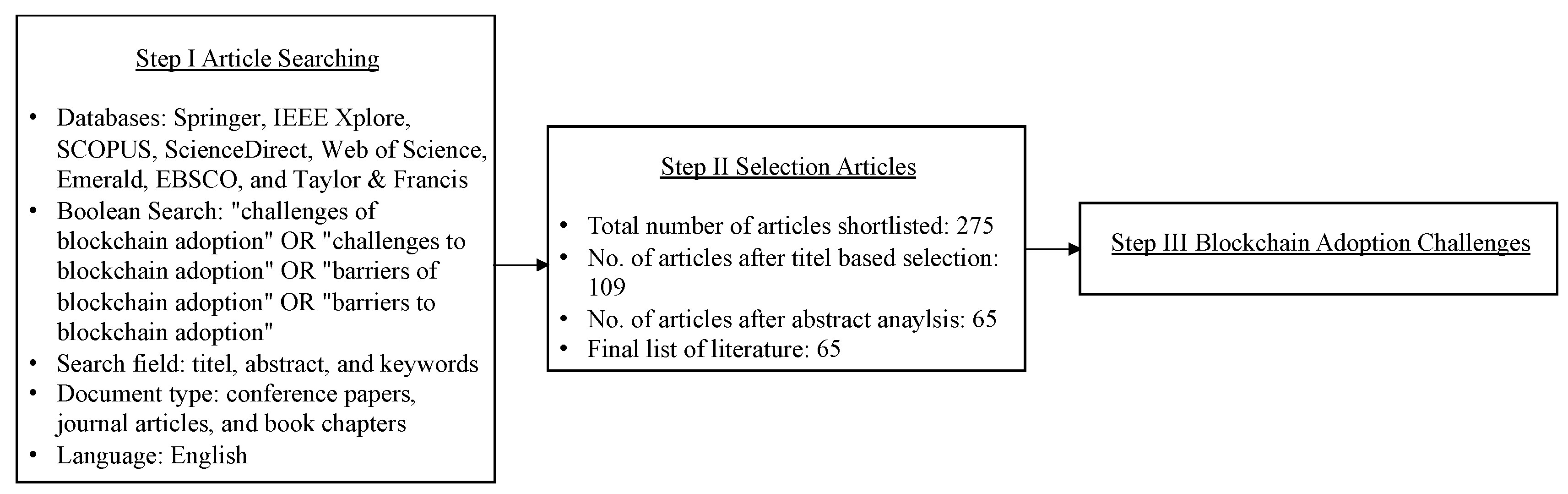

2.3. Literature Review

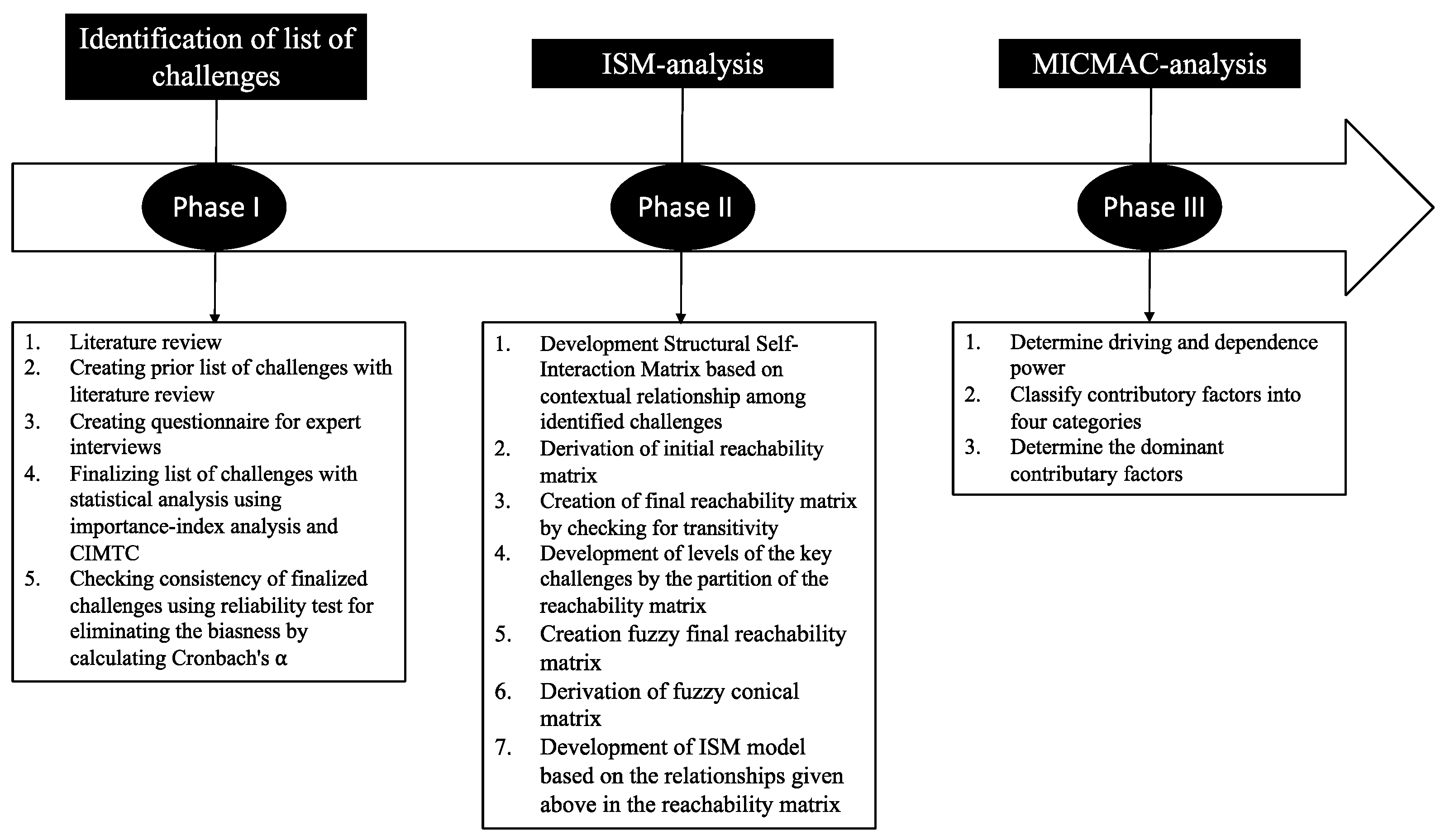

3. Methodology

3.1. ISM-Analysis

- Identification of the challenges of the concerned approach

- Establishment of a contextual relationship among challenges through expert survey.

- Creation of Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM) based on the contextual relationships between variable pairs.

- Development of reachability matrix from the SSIM and check for transitivity.

- Partition of the final reachability Matrix into different levels.

- Creation of fuzzy conical matrix.

- Development of FISM model based on the relationships given above in the reachability matrix [62,63].

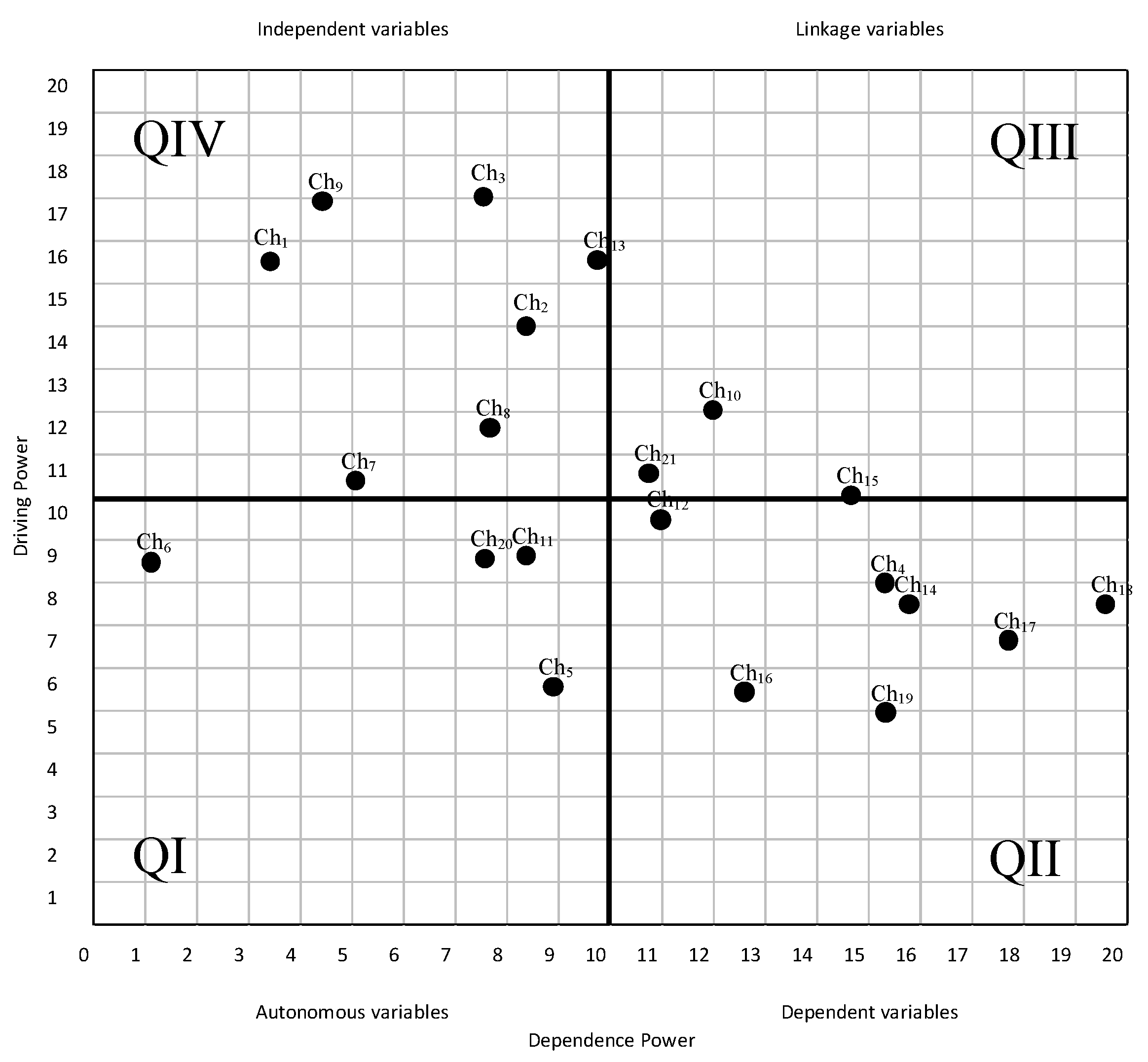

3.2. MICMAC-Analysis

4. Research and Data Analysis

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Data Analysis Using Statistical Tools

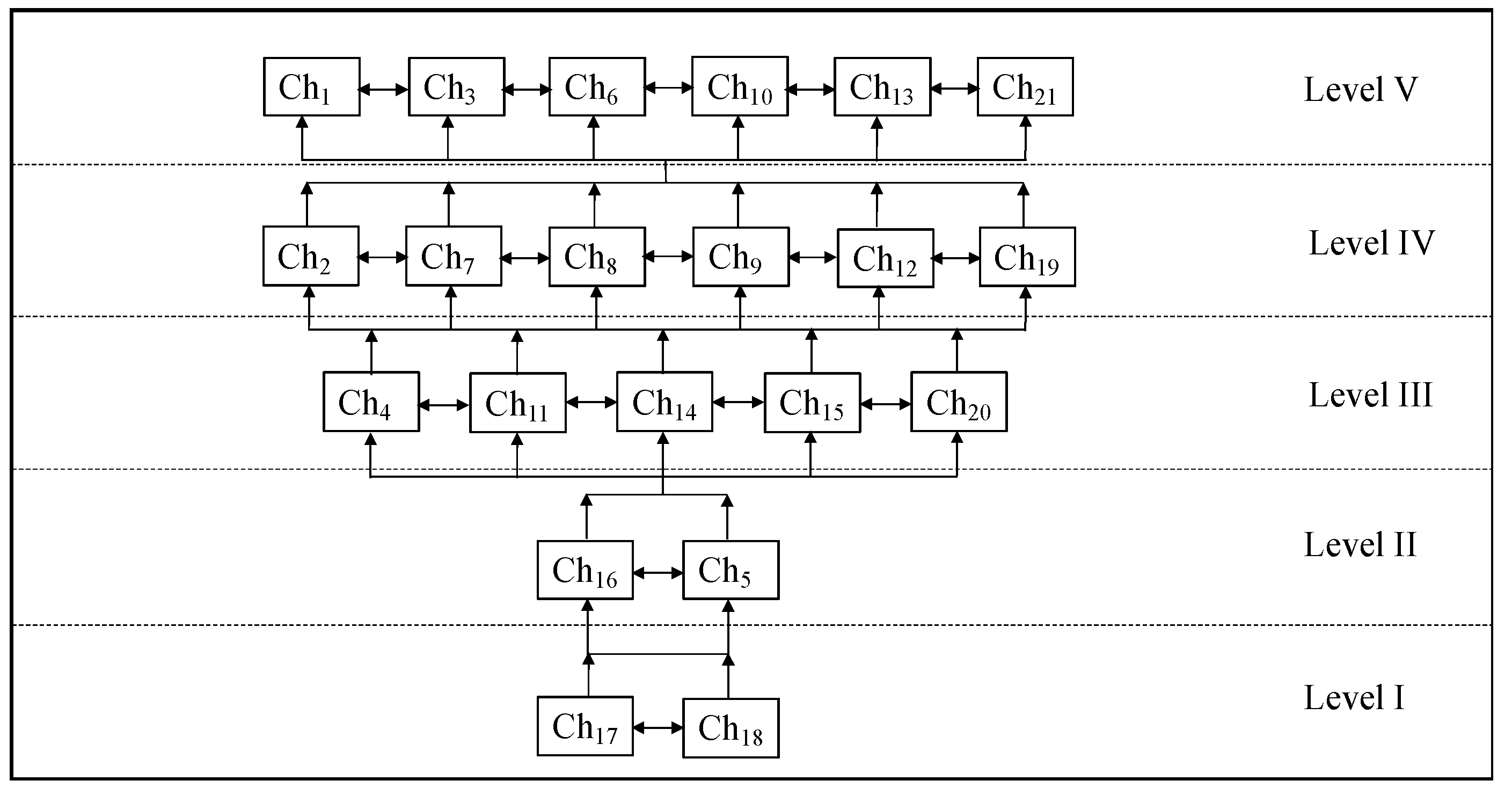

4.3. FISM-Analysis

4.3.1. Creation of Structural Self-Interaction Matrix

- V is used if challenge “i” influences or reaches challenge “j”;

- A is used if challenge “j” reaches challenge “i”;

- X is used if challenge “i” and challenge “j” influence each other and

- O is used if both challenges are unrelated (Palaniappan, Vinodh and Ranganathan, 2020).

4.3.2. Creation of Reachability Matrix

- for (i, j) entry, if it is A in SSIM, then corresponding (i, j) entry in reachability matrix becomes “1” and ( j, i) becomes “0”;

- for (i, j) entry, if it is B in SSIM, then corresponding (i, j) entry in reachability matrix becomes “0” and ( j, i) becomes “1”;

- for (i, j) entry, if it is C in SSIM, then corresponding (i, j) entry in reachability matrix becomes “1” and ( j, i) becomes “1” and

- for (i, j) entry, if it is D in SSIM, then corresponding (i, j) entry in reachability matrix becomes “0” and ( j, i) becomes “0” [127].

4.3.3. Partition of the Final Reachability Matrix into Different Levels

4.3.4. Development of Fuzzy Conical Matrix

4.3.5. Creation of FISM Model Fuzzy Conical Matrix

4.4. MICMAC Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Academic Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusion and Limitations

6.1. Conclusion

6.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ulrich, P.; Metzger, J. Sustainability reporting: The way to standardized reporting according to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive in Germany. Corporate governance: Theory and practicexs 2022, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, H.; Dencik, J.; Marshall, A. Making the responsibility for practicing sustainability a company-wide strategic priority. Strategy & Leadership 2022, 50, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.K.; Ashimwe, O.; Buertey, S.; Kim, S.-Y. The value relevance of sustainability reporting: does assurance and the type of assurer matter? Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2022, 13, 858–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFPIA, 2019. The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures. Key Data. https://www.efpia. eu/media/412931/the-pharmaceutical-industry-in-figures-2019.pdf. (Accessed: 18/11/2023).

- Shashi, M. The Sustainability Strategies in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain: A Qualitative Research. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology 2022, 11, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, P.N.; Wang, F. The Impact of Multinational Enterprises on Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction: Research Framework. International Business & Management 2017, 33, 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Malerba, F.; Orsenigo, L. The evolution of the pharmaceutical industry. Business History 2015, 57, 664–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.I.; Popesko, B. Contemporary challenges in the European pharmaceutical industry: a systematic literature review. Measuring Business Excellence 2023, 27, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Caputo, A.; Corvino, A.; Venturelli, A. Management research and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs): A bibliometric investigation and systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 276, 124033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliakoff, M.; Licence, P.; George, M.W. UN sustainable development goals: How can sustainable/green chemistry contribute? By doing things differently. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistr 2018, 13, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashi, M.; Gossett, K. Exploring Strategies to Leveraging the Blockchain in Pharmaceutical Supply Chains. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews 2022, 9, 284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, M.; Habib, S.; Hussain, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Qamar, A.; Masood, T.; Sultan, M., Muhammad, M.; Imran, S.; Hasan, M.; Akthar, M. S.; Ayub, H. M. U.; Salman, C. A. Blockchain Adoption for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Economic, Environmental, and Social Perspectives Citation. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Fraga-Lamas, P.; Fernández-Caramés, T. M. Leveraging Blockchain for Sustainability and Open Innovation: A Cyber-Resilient Approach toward EU Green Deal and UN Sustainable Development Goals. Computer Security Threats 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, J.; Ruan, G.; Jiang, P.; Xu, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, C. Blockchain-empowered sustainable manufacturing and product lifecycle management in industry 4.0: A survey. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 132, 110112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toufaily, E.; Zalan, T.; Dhaou, S.B. A framework of blockchain technology adoption: an investigation of challenges and expected value. Information and Management 2021, 58, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X.; Cheng, K.; Chen, Y.; Swartz, K. Blockchain and sustainability: An overview of challenges and main drivers of adoption. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Technology Management, Operations and Decisions (ICTMOD), Marrakech, Morocco. 2021; 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Wamba, S.F. Blockchain adoption challenges in supply chain: An empirical investigation of the main drivers in India and the USA. International Journal of Information Management 2019, 46, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Ayodele, J.O.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. A review of challenges and opportunities of blockchain adoption for operational excellence in the UK automotive industry. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing 2021, 14, 7–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Dutta, K. (2017). Blockchain: The perfect data protection tool. International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control (I2C2), Coimbatore, India, 2017, 1-3.

- Francisco, K.; Swanson, D. The supply chain has no clothes: Technology adoption of blockchain for supply chain transparency. Logistics 2018, 2, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Sarkis, J.; Shen, L. Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management. International Journal of Production Research 2019, 57, 2117–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Sarkis, J. A supply chain transparency and sustainability technology appraisal model for blockchain technology. International Journal of Production Research 2019, 58, 2142–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Li, H. The Effect of Blockchain Technology on Supply Chain Sustainability Performances. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Singh, R.K.; Mishra, R. Application of blockchain technology for sustainability development in agricultural supply chain: justification framework. Operations Management Research 2022, 15, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Mubarik, M.S.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Gupta, H.; Zaman, S.I.; Mubarik, M. Blockchain technologies as enablers of supply chain mapping for sustainable supply chains. Business Strategy and the Environment 2022, 31, 3742–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Management Reviews 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, J.; Gerard, M. Accelerating the theory and practice of sustainability- oriented innovation. MIT Sloan Research Paper 2015, 5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. Blockchain’s roles in meeting key supply chain management objectives. International Journal of Information Management 2018, 39, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Mukhuty, S.; Kumar, V.; Kazancoglu, Y. Blockchain technology and the circular economy: Implications for sustainability and social responsibility. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 293, 126130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, N.; Ormiston, J. Blockchain as a sustainability-oriented innovation?: Opportunities for and resistance to Blockchain technology as a driver of sustainability in global food supply chains. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 175, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Shishodia, A.; Kamble, S.S. Blockchain Technology for Enhancing Sustainability in Agricultural Supply Chains. Operations and Supply Chain Management in the Food Industry 2022, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, D.; Shahriar, H.; Zhang, C. Security requirement prototyping with hyperledger composer for drug supply chain: a blockchain application. ICCSP '19: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Cryptography. Security and Privacy, New York, USA, 2019, 158-163.

- Fernando, E.; Meyliana and Surjandy. Success Factor of Implementation Blockchain Technology in Pharmaceutical Industry: A Literature Review. 2019 6th International Conference on Information Technology, Computer and Electrical Engineering (ICITACEE), Semarang, Indonesia, 2019, 1-5.

- Clauson, K.A.; Crouch, R.D.; Breeden, E.A.; Salata, N. Blockchain in Pharmaceutical Research and the Pharmaceutical Value Chain. Blockchain in Life Sciences 2022, 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Pesic, S.; Ellahham, S. Blockchain for drug traceability: Architectures and open challenges. Health Informatics Journal 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryatov, S.; Borodinov, A. Blockchain technology in the pharmaceutical supply chain: Researching a business model based on hyperledger fabric. Information Technology and Nanotechnology 2019, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products. World Health Organization 2017 (Accessed: 20/11/2023).

- Niforos, M. Beyond Fintech: Leveraging Blockchain for More Sustainable and Inclusive Supply Chains. International Finance Corporation (IFC) EM Compass Note 2017, 43, 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.D. Improving the Transparency of the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain through the Adoption of Quick Response (QR) Code, Internet of Things (IoT), and Blockchain Technology: One Result: Ending the Opioid Crisis. Pittsburgh Journal of Technology Law and Policy 2018, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Burstall, R. Blockchain, IP and the pharma industry—how distributed ledger technologies can help secure the pharma supply chain. Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice 2018, 13, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, M.; Runfola, A.; Guercini, S. Pharmaceutical industry riding the wave of sustainability: Review and opportunities for future research. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 261, 121204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratyusha, K.; Gaikwad, N.M.; Phatak, A.; Chaudhari, P. D. Review on: Waste material management in pharmaceutical industry. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research 2012, 16, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kontopanou, M.; Tsoulfas, G.; Dasaklis, T.; Nikolaos, R. A review of sustainability concerns in the use of blockchain technology: Evidence from the agri-food and the pharmaceutical sectors. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Kembro, J.; Wieland, A. A new paradigm for systematic literature reviews in supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management 2017, 53, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C.; Hilletofth, P.; Eriksson, D. Critical operations capabilities for competitive manufacturing: a systematic review. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2017, 117, 801–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzstein, A.; Hartmann, E.; Benton, W.C.; Hohenstein, N. A systematic assessment of supplier selection literature – state-of-the- art and future scope. International Journal of Production Economics 2016, 182, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwa, N.R.; Sangwan, K.S. Leanness assessment of organizational performance: a systematic literature review. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2018, 29, 768–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, R.; Cowell J., M. Approaches for Improving Literature Review Methods. The Journal of School Nursing 2014, 30, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadge, A.; Weiß, M.; Caldwell, N.D.; Wilding, R. Managing cyber risk in supply chains: a review and research agenda. Supply Chain Management 2020, 25, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Jaradat, A.; Kulakli, A.; Abuhalimeh, A. A Comparative Study: Blockchain Technology Utilization Benefits, Challenges and Functionalities. IEEE Access 2019, 9, 12730–12749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooque, M.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y. Barriers to circular food supply chains in China. Supply Chain. Management: An International Journal 2019, 24, 677–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S. K.; Luthra, S.; Mishra, N.; Singh, A.; Rana, N.P.; Dora, M.; Dwivedi, Y. Barriers to effective circular supply chain management in a developing country context. Production Planning & Control 2018, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, H.-M.; Lin, C.-K.; Chen, D.-R.; Chen, Y.-S. Evolving MCDM applications using hybrid expert-based ISM and DEMATEL models: An example of sustainable ecotourism. Science World Journal 2013, 751728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumrit, D.; Anuntavoranich, P. Using DEMATEL Method to Analyze the Causal Relations on Technological Innovation Capability Evaluation Factors in Thai Technology-Based Firms. International Transaction Journal of Engineering. Management, & Applied Sciences & Technologies 2012, 4, 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, G.-H.; Chiang, C.-H.; Li, C.-W. Evaluating intertwined effects in e-learning programs: A novel hybrid MCDM model based on factor analysis and DEMATEL. Expert Systems with Applications 2007, 32, 1028–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Sharma, R. Analysis of the driving and dependence power of barriers to adopt industry 40 in Indian manufacturing industry. Computers in Industry 2018, 101, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Pokharel, S.; Kumar, P.S. A hybrid approach using ISM and fuzzy TOPSIS for the selection of reverse logistics provider. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2009, 54, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Kumar, D.T.; Diabat, A. Risks assessment in thermal power plants using ISM methodology. Annals of Operations Research 2019, 279, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenradee, P.; Dangton, R. Implementation sequence of engineering and management techniques for enhancing the effectiveness of production and inventory control system. International Journal of Production Research 2000, 38, 2689–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Qin, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y. Assessing contributory factors in potential systemic accidents using AcciMap and integrated fuzzy ISM - MICMAC approach. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 2018, 68, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Singh, A.R.; Raut, R.D.; Govindarajan, U.H. Blockchain technology adoption barriers in the Indian agricultural supply chain: an integrated approach. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2020, 161, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Sharma, R. Modeling the blockchain enabled traceability in agriculture supply chain. International Journal of Information Management 2020, 52, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandage, R.V.; Mantha, S.S.; Rane, S.B. Strategy development using TOWS matrix for international project risk management based on prioritization of risk categories. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2019, 12, 1003–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, T.; Shankar, R.; Suhaib, M. An ISM approach for modelling the enablers of flexible manufacturing system: the case for India. International Journal of Production Research 2008, 46, 6883–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailash; Saha, K.; Goyal, S. Benchmarking of internal supply chain management: factors analysis and ranking using ISM approach and MICMAC analysis. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management 2019, 27, 394–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabaharan, R.; Shanmugapriya, S. dentification of Critical Barriers in Implementing Lean Construction Practices in Indian Construction Industry. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology - Transactions of Civil Engineering 2023, 47, 1233–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjahan, M.; Wang, J.; Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Iqbal, M.; Ismail, M. Establishing a corporate social responsibility implementation model for promoting sustainability in the food sector: a hybrid approach of expert mining and ISM–MICMAC. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabat, A.; Govindan, K. An analysis of the drivers affecting the implementation of green supply chain management. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2011, 55, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, D.L. Analysis of challenges for blockchain adoption within the Indian public sector: an interpretive structural modelling approach. Information Technology & People 2022, 35, 548–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebi, I.G.; Masoomi, B.; Ghorbani, S. Expert oriented approach for analyzing the blockchain adoption barriers in humanitarian supply chain. Technology in Society 2020, 63, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, A.; Amuda, H.O.; Ajani, Y.A. Relevance of blockchain technology and the management of libraries and archives in the 4IR. Digital Library Perspectives 2022, 38, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wakefield, R.; Lyu, S.; Jayasuriya, S.; Han, F.; Yi, X.; Yang, X.; Amarasinghe, G.; Chen, S. Public and private blockchain in construction business process and information integration. Automation in Construction 2020, 118, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Gupta, R. Analysis of barriers to implement blockchain in industry and service sectors. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2019, 136, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhizadeh, M.; Saberi, S.; Sarkis, J. Blockchain technology and the sustainable supply chain: theoretically exploring adoption barriers. International Journal of Production Economics 2021, 231, 107–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yeo, W.M. Supply chain finance: what are the challenges in the adoption of blockchain technology? Journal of Digital Economy 2022, 1, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhu, J. Blockchain for smart manufacturing systems: a survey. Chinese Management Studies 2022, 16, 1224–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostern, N.; Holotiuk, F.; Moormann, J. Organizations’ Approaches to Blockchain: A Critical Realist Perspective. Information & Management 2021, 59, 103552. [Google Scholar]

- Okorie, O.; Russell, J.; Jin, Y.; Turner, C.; Wang, Y.; Charnley, F. Removing Barriers to Blockchain use in Circular Food Supply Chains: Practitioner Views on Achieving Operational Effectiveness. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 2022, 5, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoub, I.Y.; Hassoun, M.; Trentesaux, D. Blockchain adoption for SMEs: opportunities and challenges. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.; Narayanan, A.; Zhuang, J. Blockchain in humanitarian operations management: A review of research and practice. Socio-Economic Planning Science 2022, 80, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.; Ghadge, A.; Bourlakis, M. Evidence-driven model for implementing Blockchain in food supply chains. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2022, 26, 568–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Gholamreza, D.; Saeed Reza, M.; Patrick, M.; Farzad, P.R. Investigating the barriers to the adoption of blockchain technology in sustainable construction projects. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 403, 136840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, I.; Neuhofer, I.; Dogru, T.; Oztel, A.; Searcy, C.; Yorulmaz, A. Improving sustainability in the tourism industry through blockchain technology: Challenges and opportunities. Tourism Management 2022, 92, 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Kumar, S.; Narkhede, B.E. Barriers to blockchain adoption for supply chain finance: the case of Indian SMEs. Electronic Commerce Research 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, A.; Macchion, L. Drivers, barriers and supply chain variables influencing the adoption of the blockchain to support traceability along fashion supply chains. Operations Management Research 2022, 15, 1470–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Agrawal, D.; Paul, S.K. Modeling the blockchain readiness challenges for product recovery system. Annals of Operations Research 2023, 327, 493–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, M.M.; Wamba, S.F.; De Bourmont, M.; Telles, R. Blockchain adoption in operations and supply chain management: empirical evidence from an emerging economy. International Journal of Production Research 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Mishra, R.; Gupta, S.; Mukherjee, A. Blockchain applications for secured and resilient supply chains: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2023, 175, 108854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, N. Blockchain challenges in adoption. Managerial Finance 2020, 46, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Arash, K.N.; Heidary, M.; Nosrati-Abargooee, S.; Mina, H. Prioritizing adoption barriers of platforms based on blockchain technology from balanced scorecard perspectives in healthcare industry: a structural approach. International Journal of Production Research 2021, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.; Vargas, S. Barriers Affecting Higher Education Institutions’ Adoption of Blockchain Technology: A Qualitative Study. Informatics 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Yan, J. Processes, benefits, and challenges for adoption of blockchain technologies in food supply chains: a thematic analysis. Information Systems and e-Business Management 2021, 19, 909–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.S.B.B.; Thakur, V. The factors obstructing the blockchain adoption in supply chain finance: a hybrid fuzzy DELPHI-AHP-DEMATEL approach. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Rani, P. Evaluate the barriers of blockchain technology adoption in sustainable supply chain management in the manufacturing sector using a novel Pythagorean fuzzy-CRITIC-CoCoSo approach. Operations Management Research 2022, 15, 725–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdellah, A.; Zekhnini, K.; Anass, C.; Garza-Reyes, J.; Bandrana, A.; Elbaz, J. Blockchain Technology for Viable Circular Digital Supply Chains: An Integrated Approach for Evaluating the Implementation Barriers. Benchmarking An International Journal 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann-Lohmer, J.; Lasch, R. Blockchain in operations management and manufacturing: Potential and barriers. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 148, 106789. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, S.; Chen, S-L.; Shu-Ling Chen, P.; Du, Y. Blockchain adoption in container shipping: An empirical study on barriers, approaches, and recommendations. Marine Policy 2023, 155, 105724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmarski, A. Blockchain Adoption in Academia: Promises and Challenges. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology. Market, and Complexity 2020, 6, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Mathivathanan, D.; Mathiyazhagan, K.; Rana, N.; Khorana, S.; Dwivedi, Y. Barriers to the adoption of blockchain technology in business supply chains: a total interpretive structural modelling (TISM) approach. International Journal of Production Research 2021, 59, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Dwivedi, Y.; Misra, S.; Rana, N. Conjoint Analysis of Blockchain Adoption Challenges in Government. Journal of Computer Information Systems 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. Blockchain Adoption in Life Sciences Organizations: Socio-organizational Barriers and Adoption Strategies. Blockchain in Life Sciences. Blockchain Technologies 2022, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, E. The missing piece: the link between blockchain and public policy design. Policy Design and Practice 2023, 6, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tatge, L.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y. Blockchain applications in the supply chain management in German automotive industry. Production Planning & Control 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, I.; Abolhasan, M.; Abbas, H.; Ni, W. Blockchain’s adoption in IoT: The challenges, and a way forward. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2019, 125, 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Shoaib, M.; Adebayo, T.; Irfan, M. A strategic roadmap to overcome blockchain technology barriers for sustainable construction: A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2023, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheb, T.; Mamaghani, F.H. Exploring the barriers and organizational values of blockchain adoption in the banking industry”. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 2021, 32, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, G.; Surucu-Balci, E. Blockchain adoption in the maritime supply chain: Examining barriers and salient stakeholders in containerized international trade. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2021, 156, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Viktorovich, D.A.; Sahu, A.K.; Sahu, A.K. Barriers to adoption of blockchain technology in green supply chain management. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing 2021, 14, 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S. Barriers to blockchain adoption in health-care industry: an Indian perspective. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing 2021, 14, 134–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli, G.; Zardini, A.; Rossignoli, C. Blockchain adoption in the fashion sustainable supply chain: Pragmatically addressing barriers. Journal of Organizational Change Management 2021, 34, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.S.; Chandani, A. Challenges of blockchain application in the financial sector: a qualitative study. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanka, A.; Muhammad, I.; Huang, I.; Cheung, R. A survey of breakthrough in blockchain technology: Adoptions, applications, challenges and future research. Computer Communications 2021, 169, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghode, D.J.; Yadav, V.; Jain, R.; Soni, G. Blockchain adoption in the supply chain: an appraisal on challenges. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2021, 32, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naef, S.; Wagner, S.; Saur, C. Blockchain and network governance: learning from applications in the supply chain sector. Production Planning & Control 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.B. Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 2005, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, R.M. A note on aggregating opinions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 1978, 21, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.K.; Chen, Y.S.; Chuang, H.M. Improving project risk management by a hybrid MCDM model combining DEMATEL with DANP and VIKOR methods—an example of cloud CRM. Frontier Computing 2016, 375, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Jia, J.; Ding, J.; Shang, S.; Jiang, S. Interpretive Structural Model Based Factor Analysis of BIM Adoption in Chinese Construction Organizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Parekh, H.; Joshi, S. Modeling the internet of things adoption barriers in food retail supply chains. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2019, 48, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadi, N.; Van Gelder, P.; Strozzi, F. An ism modeling of barriers for blockchain/distributed ledger technology adoption in supply chains towards cybersecurity. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Singh, S.P. An integrated fuzzy-ANP and fuzzy-ISM approach using blockchain for sustainable supply chain. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 2021, 34, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sangwan, K.S. Employee involvement and training in environmentally conscious manufacturing implementation for Indian manufacturing industry”. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Selangor, 2014, 1317-1321.

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). NJ: Pearson Education International. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Hu, X. Research on Risk Influencing Factors of Logistics Information Ecosystem Based on Interpretive Structural Modeling. EBIMCS '21: Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on E-Business, Information Management and Computer Science, 254–260.

- Attri, R.; Dev, N.; Sharma, V. Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) Approach: An Overview. Research Journal of Management Sciences 2013, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Warfield, J.N. Toward Interpretation of Complex Structural Models". IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1974, 4, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Noorul Haq, A. Analysis of interactions of criteria and sub-criteria for the selection of supplier in the built-in-order supply chain environment. International Journal of Production Research 2007, 45, 3831–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, J.P.; Sushil; Vrat, P. Hierarchy and classification of program plan elements using interpretive structural modeling: A case study of energy conservation in the Indian cement industry. Systems Practice 1992, 5, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Raj, T. Modeling and analysis of FMS flexibility factors by TISM and fuzzy MICMAC. International Journal of Systems Assurance Engineering and Management 2015, 6, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, P.M.; Burgess, S.C. Introducing OEE as a measure of lean Six Sigma capability. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma 2010, 1, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chong, H.-Y.; Chi, M. Modelling the blockchain adoption barriers in the AEC industry. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023, 30, 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, S.; Pati, R.; Padhi, S. Market dynamics and reverse logistics for sustainability in the Indian Pharmaceuticals industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 208, 968–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papert, M.; Rimpler, P.; Pflaum, A. Enhancing supply chain visibility in a pharmaceutical supply chain: Solutions based on automatic identification technology. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2016, 46, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Challenge | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | High costs of blockchain investments | Organizations can incur significant costs, particularly during the initial adoption phase, as they may need to develop software, including encryption and tracking technologies, and invest in additional hardware to establish blockchain-based operating systems. Moreover, while current blockchain usage is free, as adoption increases, subscription fees might be introduced due to network saturation, like other technology adoption scenarios. | 70,71,72,73,15,74,75,18,77, 76,78,79,80,81,82,21,83,84, 8,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92, 93,94,95,96,97 |

| 2 | Lack of regulatory framework | If proper governmental regulations (data security and privacy laws) are not put in place,the widespread adoption of blockchain will remain hindered. | 15,62,18,77,98,76,78,99,89,93,79,80,81,100,83,8,101,,90,93,102,95,103,104,105,106 |

| 3 | Lack of management support | Effective support from senior management is essential for the successful implementation of any sustainability initiative. This is especially true for the adoption of technology, where organizational leadership plays a crucial role. | 75,78,89,107,108,21,84,8,101,106,109,90,91,92,110 |

| 4 | Lack of security | Issues related to security can lead to data vulnerabilities, hacking risks, loss of confidentiality, reputation damage, regulatory non-compliance, and reluctance to adopt the technology. These issues collectively can hinder the adoption of blockchain in business settings. | 111,70,112,73,15,75,18,77,78,99,89,93,79,105,113,100,21,103,83,84,8,101,85,87,106,114,91,92,95 |

| 5 | Difficulty in changing organizational culture | The adoption of blockchain technology results in the alteration or evolution of the existing organizational culture. Organizational culture encompasses norms related to work environment and suitable conduct within the organization. | 111,100,21,103,84,109,90 |

| 6 | Lack of standardization and homogeneity | Standardization has the potential to enhance efficiency, particularly through features like smart contracts, and it specifies transaction structures, validation, and security within the blockchain network. Without established standards, corporate hesitation is unlikely to diminish, and standardization can also break down technical silos, aligning with the blockchain's core aim of dismantling information silos and enabling horizontal integration. | 111,75,18,78,79,82,85,86,91,96,97 |

| 7 | Degree of immutability | Immutability can create challenges when it comes to data accuracy, regulatory compliance, and adaptability since once data is recorded in a blockchain, it cannot be easily altered or deleted. While this is a key feature for security and trust, it can be problematic if errors are made or if there's a need to update information. The immutability feature can also pose legal and regulatory challenges. | 111,70,75,80,21,8,89,114,91,92,93 |

| 8 | Lack of interoperability | Interoperability refers to the capability of different blockchain networks or systems to communicate and share data seamlessly. When interoperability is lacking, efficient data exchange between networks is prevented due to fragmented landscapes as well as a smooth transfer of assets and data across platforms is hindered. This siloed approach limits innovation, increases complexity, and can result in vendor lock-in since one may be dependent on a single blockchain platform. | 111,70,71,112,15,62,18,77,98,76,78,79,80,113,82,21,115,103,105,84,85,89,91,92,96 |

| 9 | Lack of resources | The complexity of blockchain may demand a significant investment of time and resources for companies to become proficient, while the expenses associated with hiring blockchain experts can be exceptionally steep due to high demand in the field. | 111,112,18,98,80,108,21,103,83,82,84,101,85,89,90,91,93 |

| 10 | Lack of governmental support and regulations | Despite the increasing number of countries considering initiatives to embrace Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) and blockchains, tangible support from governments - such as incentives to adopt blockchain or laws that concern data sharing -remains limited and uncertain at this juncture. | 111,75,18,77,98,103,99,93,79,80,108,113,100,82,21,103,104,83,107,84,101,85,87,89,91,92,93,97,110 |

| 11 | Lack of market acceptance | The market's uncertain stance on accepting the technology and its associated products acts as a deterrent for managers when contemplating the risk of such investments and leads to trust issues among the stakeholders | 111,15,17,75,18,99,89,93,107,80,108,21,82,8,85,86,88,106,90,91,92,102,95,96,24 |

| 12 | Lack of scalability | The restricted block size in blockchain technologies has led to scalability challenges, with Bitcoin's block size of 1MB allowing just 7 transactions per second. Scalability affects the ability to handle growing transactions, while slow speeds hinder real-time processing. These limitations can impede adoption in various sectors and discourage investment in blockchain projects. | 111,70,71,73,15,18,79,80,105,113,82,103,8,101,85,91,92,93 |

| 13 | Lack of maintenance and management | Without regular maintenance blockchain networks experience slower transaction speeds and reduced efficiency leading to performance degradation. Ignoring security updates exposes the blockchain to exploitation by malicious actors, compromising data security and can lead to compatibility issues with newer systems. Furthermore, inadequate management can introduce errors, eroding the trust in the immutability of blockchain data and result in unexpected downtime, disrupting operations. Leading to users losing trust in poorly maintained blockchains, impacting adoption. | 111,70,71,112,72,18,75,15,76,105 |

| 14 | Lack of technology expertise and skills | Without a solid grasp of blockchain's intricacies, there's a higher likelihood of poorly designed or executed blockchain projects, resulting in suboptimal outcomes leading to reluctance in adopting blockchain solutions due to perceived risks. Furthermore, organizations may struggle to formulate effective strategies around blockchain integration without a clear understanding of how the technology aligns with their goals, including employee training. | 111,70,71,112,72,15,75,18,98,76,79,108,113,81,100,82,21,103,83,107,80,8,101,85,89,109,91,92,94,95,97 |

| 15 | Lack of data privacy | Since blockchain transactions are recorded on a public database accessible to anyone, it generates a setting that gives rise to privacy concerns for this technology. | 70,112,73,15,75,18,77,98,78,80,105,108,113,81,100,82,21,103,83,79,84,85,90,114,91,92,95,96,24 |

| 16 | Lack of validation | Due to limited piloting, insufficient validation could impede the adoption and utilization of blockchain technology. | 70,71,108,82,21,115,83,105,89 |

| 17 | Costs of latency | Given the inherent structure of the architecture, which requires the synchronization of all blocks within the chain for any new additions, this process could be resource-intensive, particularly in the case of extensive blockchains. This computational demand might pose a potential hindrance to implementation | 70,18,79,80,101,85,93 |

| 18 | Lack of collaboration and network establishment | Setting up a blockchain network system necessitates the participation and conviction of all involved parties that blockchain offers value to them. Moreover, achieving cooperation, communication, and coordination during the implementation process presents challenges. | 15,73,18,98,76,100,21,115,104,84,85,109,90,114,,91,102,24 |

| 19 | Lack of maturity | Computing processing power Blockchain is slow in operation.The restricted block size in blockchain technologies has led to scalability challenges, with Bitcoin's block size of 1MB allowing just 7 transactions per second. Scalability affects the ability to handle growing transactions, while slow speeds hinder real-time processing. These limitations can impede adoption in various sectors and discourage investment in blockchain projects. | 111,75,18,98,78,99,89,93,80,113,21,104,82,84,8,106,90,114,91,92,93,95 |

| 20 | Uncertain financial and environmental benefits | Blockchain mining consumes substantial energy for complex computations. Computers used for mining consume more energy than rewards. Expanding processor racks use energy comparable to lighting a megacity. Blockchain-based instruments' rising value attracts miners, yet increased rewards don't always lead to higher economic gains. Scalability issues worsen sustainability challenges. Proposed efficient hardware like Application Specific Integrated Circuits lags in large-scale production. | 81,100,82,103,83,99,79,84,8,90,95,74,18,89,92 |

| 21 | Lack of employee acceptance | Employee acceptance hinges on multiple factors. Performance Expectancy gauges if the system aids job performance. Social Influence considers others' views on system use. Facilitating Conditions assess support for system use. In supply chains, transparency involves how information is conveyed to stakeholders. These factors shape employee system acceptance. | 17,75,8,88,109,91,97 |

| 22 | Reluctance to change business processes | Due to the broad applicability of blockchain across extensive and varied networks involving numerous stakeholders, be they individuals or institutions, its integration demands a specific level of expertise, time, and human resources. This could potentially lead companies and network participants to be hesitant about altering their business processes. | 81,100,103,83,82,99,79,84,8,101,85,95 |

| 23 | Unclear responsibilities | While advocating for a decentralized database has its merits, there are instances where this kind of network can have drawbacks. Due to the distribution of data among participants in a blockchain, with equal footing depending on the permission type, the level of accountability among parties becomes ambiguous. | 81,99,95 |

| 24 | Lack of awareness | Customers' lack of awareness about blockchain and its diverse applications necessitates education on its features and implications for data ownership, access, and privacy. This education can boost blockchain adoption by companies and enhance the industry's social sustainability for customers. | 111,106,83,21,84,92,95 |

| No. | Gender | Highest education | Industry | Expert profile | Country | Experience in years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | MBA | IT | CIO | India | 23 |

| 2 | Male | Master | Pharma | Data Tech System Owner | Spain | 12 |

| 3 | Female | MBA | IT | Healtcare & Pharma Consultant | Switzerland | 11 |

| 4 | Male | PhD | IT | Director | United States | 15 |

| 5 | Male | MBA | IT | Supply Chain Expert | UK | 25 |

| 6 | Male | Master | Pharma | Managing Director | Luxembourg | 15 |

| 7 | Male | Master | Pharma | CEO | France | 11 |

| 8 | Female | MBA | Pharma | Data Privacy Senior Associate | Germany | 11 |

| 9 | Male | Master | IT | Blockchain Scientist | Germany | 10 |

| 10 | Male | MBA | IT | Supply Chain Expert | Germany | 20 |

| 11 | Male | PhD | IT | Chief Product Manager Life Sciences | Germany | 30 |

| 12 | Male | MBA | IT | Managing Director | India | 27 |

| 13 | Female | Master | IT | Business Process Consultant | Canada | 17 |

| 14 | Female | Professor | Academic | Professor | Italy | 30 |

| 15 | Female | MBA | IT | Managing Director | United States | 20 |

| 16 | Male | PhD | Pharma | Managing Director | Canada | 28 |

| 17 | Male | MBA | IT | Digital Supply Chain Manager | Turkey | 25 |

| 18 | Male | Professor | Academic | Associate Research Director | Singapore | 16 |

| No. | Challenge code | Challenges of blockchain adoption in the pharmaceutical industry | Mean | Standard Deviation | Importance Index | CIMTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ch1 | High costs of blockchain investments | 3.1111 | 1.2783 | 0.6222 | 0.5060 |

| 2 | Ch2 | Lack of regulatory framework | 3.6667 | 1.0847 | 0.7333 | 0.6601 |

| 3 | Ch3 | Lack of management support | 3.9444 | 1.0556 | 0.7889 | 0.5236 |

| 4 | Ch4 | Lack of security | 2.8889 | 1.4507 | 0.5778 | 0.7194 |

| 5 | Ch5 | Difficulty in changing organizational culture | 3.0556 | 1.3492 | 0.6111 | 0.2583 |

| 6 | Ch6 | Lack of standardization and homogenity | 3.1111 | 1.3235 | 0.7667 | 0.4913 |

| 7 | Ch7 | Degree of immutability | 3.6667 | 1.4142 | 0.6222 | 0.7945 |

| 8 | Ch8 | Lack of interoperability | 3.6111 | 1.0922 | 0.7444 | 0.6198 |

| 9 | Ch9 | Lack of resources | 4.000 | 1.3720 | 0.7111 | 0.8437 |

| 10 | Ch10 | Lack of governmental support and regulations | 3.3333 | 1.0290 | 0.7778 | 0.7332 |

| 11 | Ch11 | Lack of market acceptance | 3.0000 | 1.2367 | 0.6778 | 0.7307 |

| 12 | Ch12 | Lack of scalability | 3.2222 | 1.3086 | 0.5778 | 0.6181 |

| 13 | Ch13 | Lack of maintenance and management | 3.3333 | 1.3284 | 0.6444 | 0.7692 |

| 14 | Ch14 | Lack of technology expertise and skills | 3.1667 | 1.5811 | 0.7000 | 0.8541 |

| 15 | Ch15 | Lack of data privacy | 3.1667 | 1.2005 | 0.5889 | 0.4668 |

| 16 | Ch16 | Lack of validation | 2.8333 | 1.1504 | 0.6556 | 0.6219 |

| 17 | Ch17 | Costs of latency | 3.1667 | 1.2485 | 0.5778 | 0.6527 |

| 18 | Ch18 | Lack of collaboration and network establishment | 3.7222 | 1.3198 | 0.6667 | 0.6464 |

| 19 | Ch19 | Lack of maturity | 3.9444 | 0.9984 | 0.7222 | 0.1380 |

| 20 | Ch20 | Uncertain financial and enviromental benefits | 2.7220 | 1.1785 | 0.7556 | 0.2942 |

| 21 | Ch21 | Lack of employee acceptance | 3.1667 | 1.1504 | 0.5556 | 0.6152 |

| 22 | Ch22 | Reluctance to change business processes | 3.1667 | 1.0432 | 0.6667 | 0.8038 |

| 23 | Ch23 | Unclear responsibilities | 3.7222 | 0.9583 | 0.6333 | 0.4215 |

| 24 | Ch24 | Lack of awareness | 3.7222 | 1.2744 | 0.7222 | 0.4126 |

| No. | Challenge code | Challenges of blockchain adoption in the pharmaceutical industry |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ch1 | High costs of blockchain investments |

| 2 | Ch2 | Lack of regulatory framework |

| 3 | Ch3 | Lack of management support |

| 4 | Ch4 | Lack of security |

| 5 | Ch5 | Lack of standardization and homogenity |

| 6 | Ch6 | Degree of immutability |

| 7 | Ch7 | Lack of interoperability |

| 8 | Ch8 | Lack of resources |

| 9 | Ch9 | Lack of governmental support and regulations |

| 10 | Ch10 | Lack of market acceptance |

| 11 | Ch11 | Lack of scalability |

| 12 | Ch12 | Lack of maintenance and management |

| 13 | Ch13 | Lack of technology expertise and skills |

| 14 | Ch14 | Lack of data privacy |

| 15 | Ch15 | Lack of validation |

| 16 | Ch16 | Costs of latency |

| 17 | Ch17 | Lack of collaboration and network establishment |

| 18 | Ch18 | Lack of employee acceptance |

| 19 | Ch19 | Reluctance to change business processes |

| 20 | Ch20 | Unclear responsibilities |

| 21 | Ch21 | Lack of awareness |

| Challenge code | Ch21 | Ch20 | Ch19 | Ch18 | Ch17 | Ch16 | Ch15 | Ch14 | Ch13 | Ch12 | Ch11 | Ch10 | Ch9 | Ch8 | Ch7 | Ch6 | Ch5 | Ch4 | Ch3 | Ch2 | Ch1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | V | O | V | O | V | V | V | V | V | A | V | V | O | A | V | O | V | V | V | V | X |

| Ch2 | A | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | A | V | O | O | X | V | V | A | V | V | A | X | |

| Ch3 | X | V | V | V | V | V | X | V | V | V | V | X | A | O | O | O | V | V | X | ||

| Ch4 | A | A | A | X | V | V | V | X | A | A | O | V | A | A | O | A | A | X | |||

| Ch5 | O | O | O | O | O | O | A | O | O | V | V | O | A | O | X | O | X | ||||

| Ch6 | O | O | O | V | O | O | O | V | O | O | O | V | O | O | O | X | |||||

| Ch7 | O | O | O | V | O | O | O | V | V | V | V | V | O | O | X | ||||||

| Ch8 | A | O | A | V | O | O | V | V | X | V | V | V | O | X | |||||||

| Ch9 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | X | V | V | V | X | X | ||||||||

| Ch10 | V | O | V | V | X | O | X | V | X | O | O | X | |||||||||

| Ch11 | O | O | V | V | V | V | V | V | A | V | X | ||||||||||

| Ch12 | O | A | V | X | V | V | V | V | A | X | |||||||||||

| Ch13 | V | V | V | X | V | V | X | V | X | ||||||||||||

| Ch14 | O | A | A | V | V | V | V | X | |||||||||||||

| Ch15 | V | V | V | X | X | V | X | ||||||||||||||

| Ch16 | V | A | V | V | V | X | |||||||||||||||

| Ch17 | X | A | V | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Ch18 | A | A | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Ch19 | A | A | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ch20 | A | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ch21 | X |

| Challenge code | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch4 | Ch5 | Ch6 | Ch7 | Ch8 | Ch9 | Ch10 | Ch11 | Ch12 | Ch13 | Ch14 | Ch15 | Ch16 | Ch17 | Ch18 | Ch19 | Ch20 | Ch21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1 |

| Ch2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ch3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1* | 1* | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 0 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* |

| Ch7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1* |

| Ch8 | 1 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 0 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1* | 0 |

| Ch9 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch10 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 |

| Ch11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1* |

| Ch12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1* |

| Ch13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1* |

| Ch15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ch17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ch18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch20 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 0 | 1* | 1* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ch21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1* | 1* | 0 | 1* | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch (Chi) | Reachability set | Antecedent set | Intersection | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 8, 9, 12, 18, 20 | 1, 18, 20 | V |

| Ch2 | 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 | 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 10, 13, 21 | 2, 9 | IV |

| Ch3 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 15, 21 | 3, 8, 10, 15, 21 | V |

| Ch4 | 4, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 4, 14, 18 | III |

| Ch5 | 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 | 5, 7, 8, 10, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18 | II |

| Ch6 | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 6, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20 ,21 | 6, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21 | V |

| Ch7 | 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21 | 5, 7, 8, 9, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21 | IV |

| Ch8 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21 | 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 13, 16, 17, 20 | IV |

| Ch9 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14 | 2, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14 | IV |

| Ch10 | 2, 3, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 20 | 3, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 20 | V |

| Ch11 | 6, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21 | 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 19, 20, 21 | 6, 10, 11, 20, 21 | III |

| Ch12 | 1, 4, 6, 10, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 6, 10, 12, 18, 21 | IV |

| Ch13 | 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 15, 18 | 5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 15, 18 | V |

| Ch14 | 4, 5, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21 | 4, 5, 9, 14, 21 | III |

| Ch15 | 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20 | 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 13, 15, 17, 18 | III |

| Ch16 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 20 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 16 | II |

| Ch17 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 15, 17, 18, 19, 21 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 15, 17, 18, 19, 21 | I |

| Ch18 | 1, 4, 5, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 19 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 4, 5, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 19 | I |

| Ch19 | 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 17, 18 19 | 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 6, 7, 18, 19 | IV |

| Ch20 | 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 | 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15, 20, 21 | 1, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 20 | III |

| Ch21 | 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 | 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 21 | 3, 6, 7, 11, 12, 14, 17, 21 | V |

| Possibility of reachbility | No. | Very low | Low | Medium | High | Very high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Challenge code | Ch1 | Ch2 | Ch3 | Ch4 | Ch5 | Ch6 | Ch7 | Ch8 | Ch9 | Ch10 | Ch11 | Ch12 | Ch13 | Ch14 | Ch15 | Ch16 | Ch17 | Ch18 | Ch19 | Ch20 | Ch21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 |

| Ch2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ch3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Ch7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Ch8 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Ch9 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch10 | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 |

| Ch11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Ch12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.3 |

| Ch13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Ch15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ch16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ch17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ch18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ch20 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ch21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Challenge code | Ch19 | Ch16 | Ch4 | Ch5 | Ch17 | Ch14 | Ch18 | Ch6 | Ch20 | Ch12 | Ch11 | Ch7 | Ch21 | Ch15 | Ch8 | Ch10 | Ch2 | Ch1 | Ch13 | Ch3 | Ch9 | Driving power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ch19 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Ch16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.4 |

| Ch4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Ch5 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5.6 |

| Ch17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 |

| Ch14 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7.5 |

| Ch18 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7.5 |

| Ch6 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.1 | 8.3 |

| Ch20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.6 |

| Ch12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.4 |

| Ch11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 9.7 |

| Ch7 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 10.3 |

| Ch21 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 10.7 |

| Ch15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Ch8 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 11.7 |

| Ch10 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Ch2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 |

| Ch1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15.5 |

| Ch13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15.5 |

| Ch3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 17 |

| Ch9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 17.9 |

| Dependence power | 15.2 | 12.6 | 15.3 | 8.9 | 17.6 | 15.8 | 19.6 | 1.1 | 7.6 | 10.9 | 8.2 | 5.1 | 10.7 | 14.6 | 7.6 | 12 | 8.3 | 3.4 | 9.8 | 7.5 | 4.3 | 215.2/215.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).