Submitted:

15 January 2024

Posted:

16 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

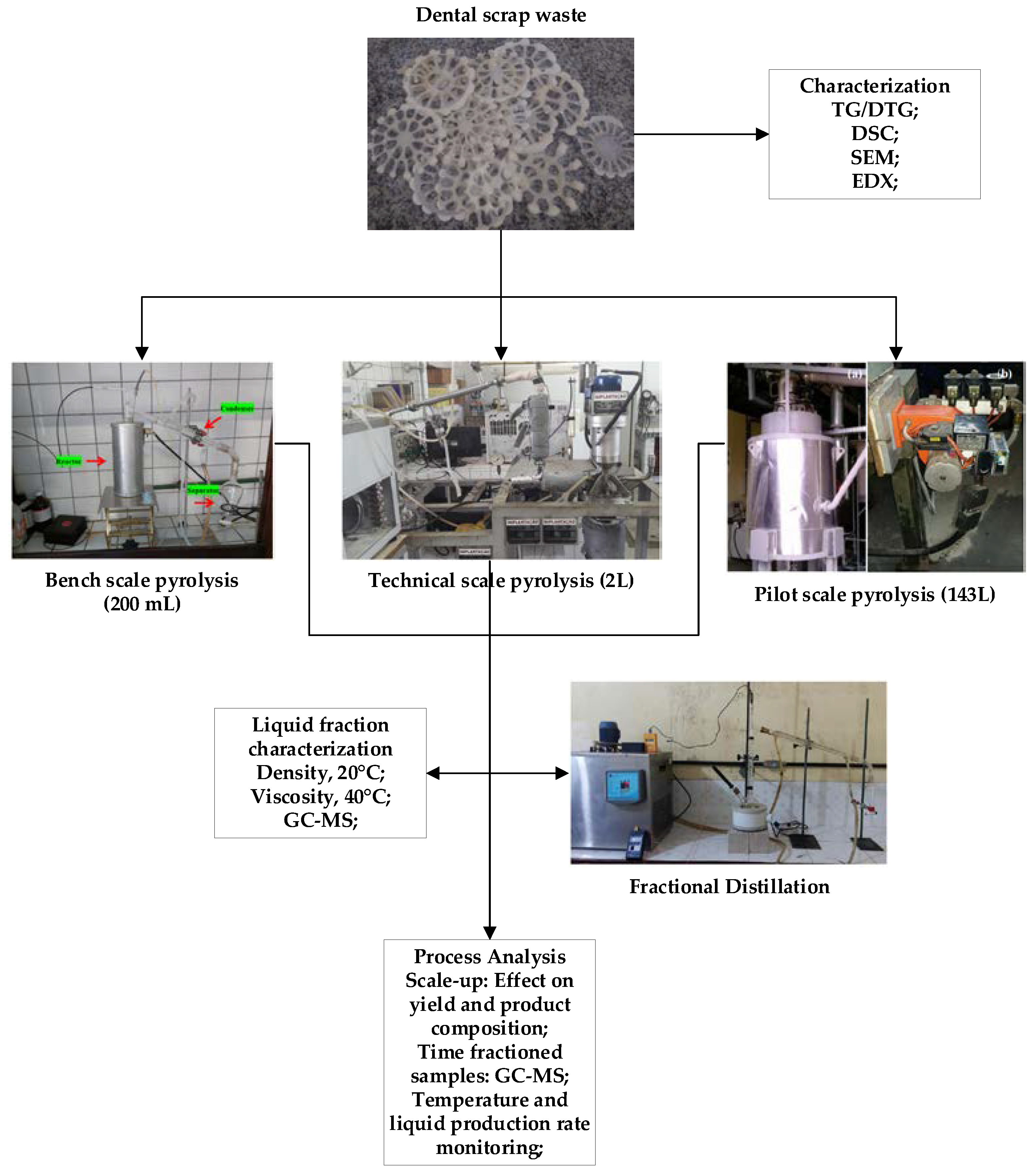

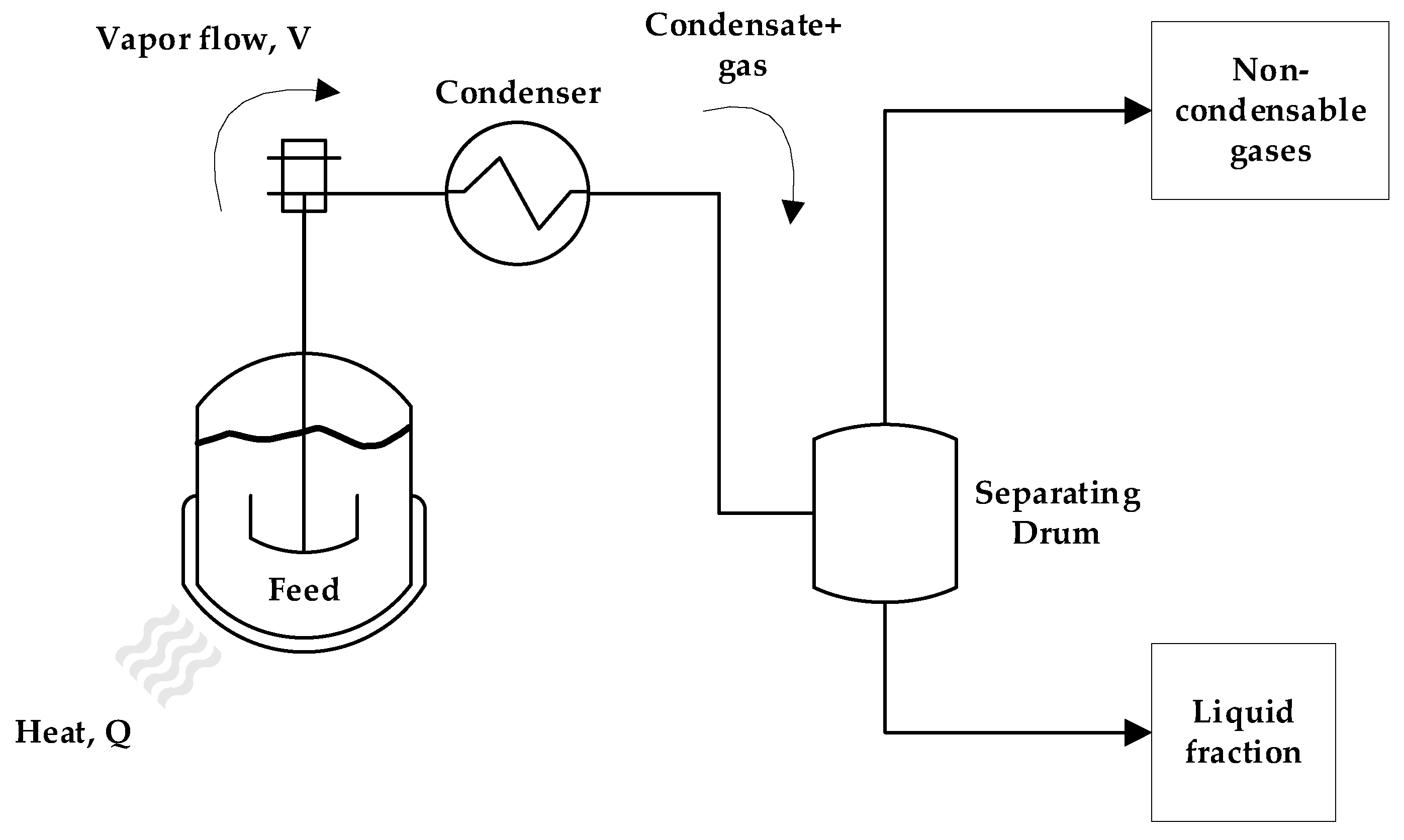

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

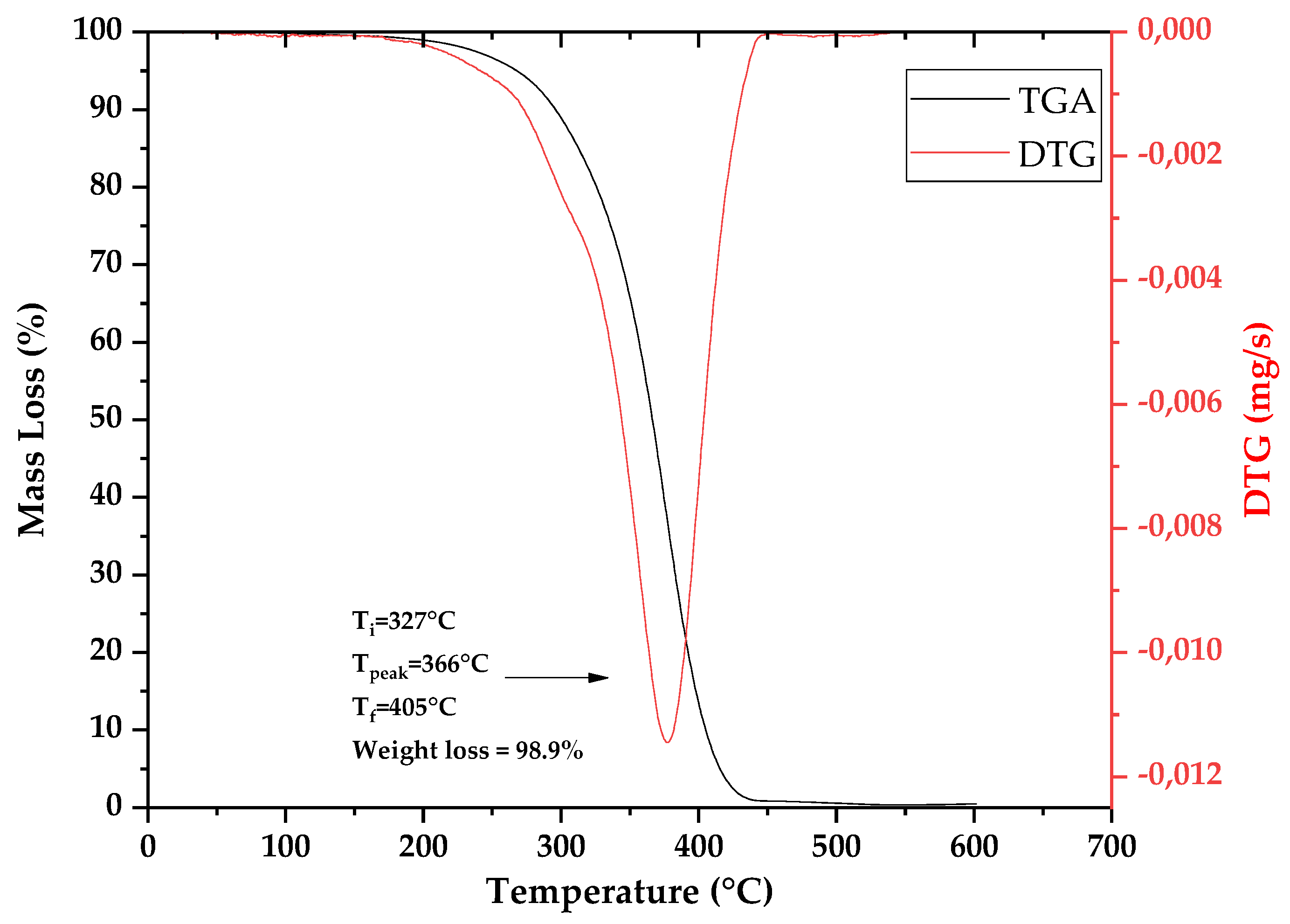

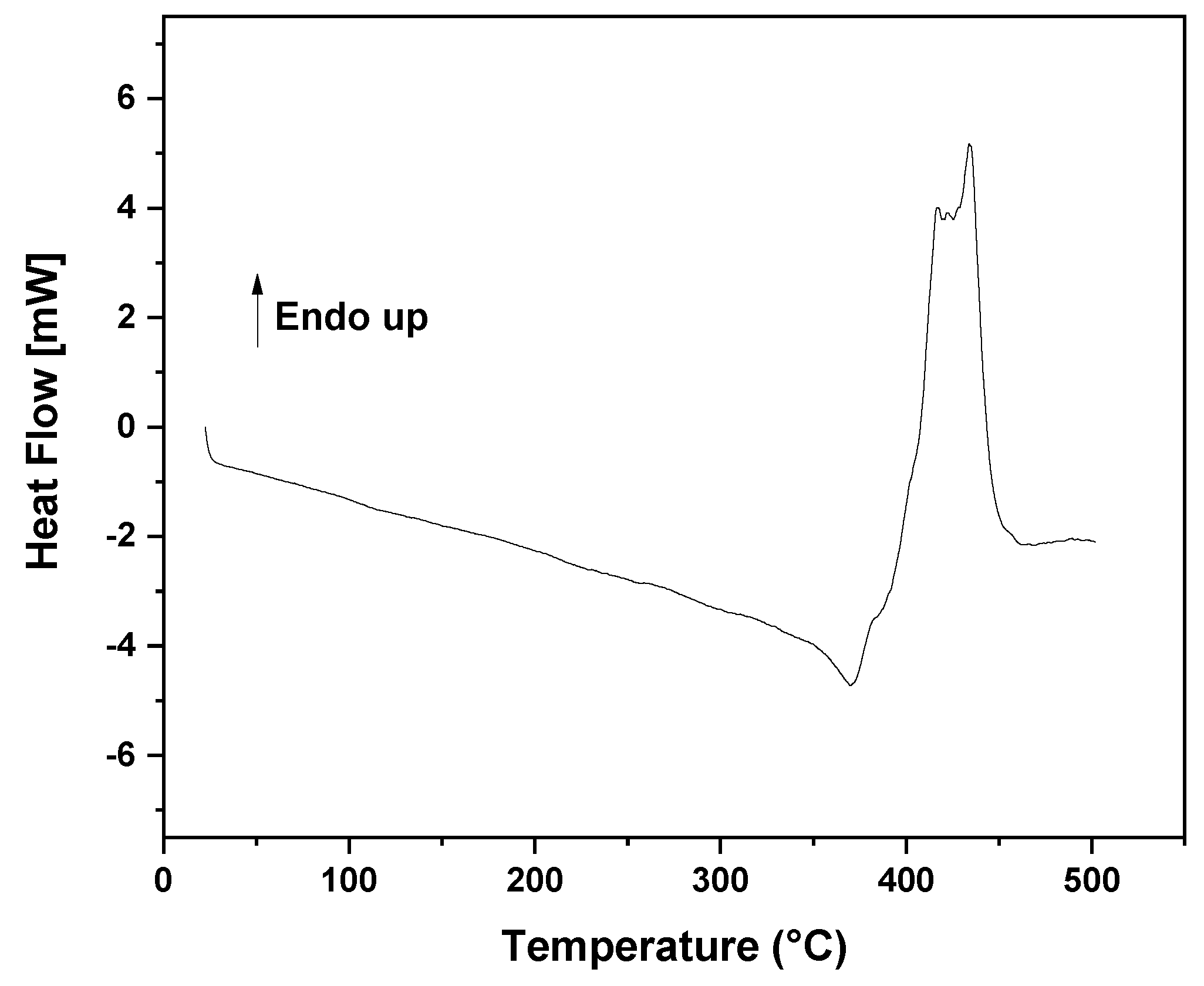

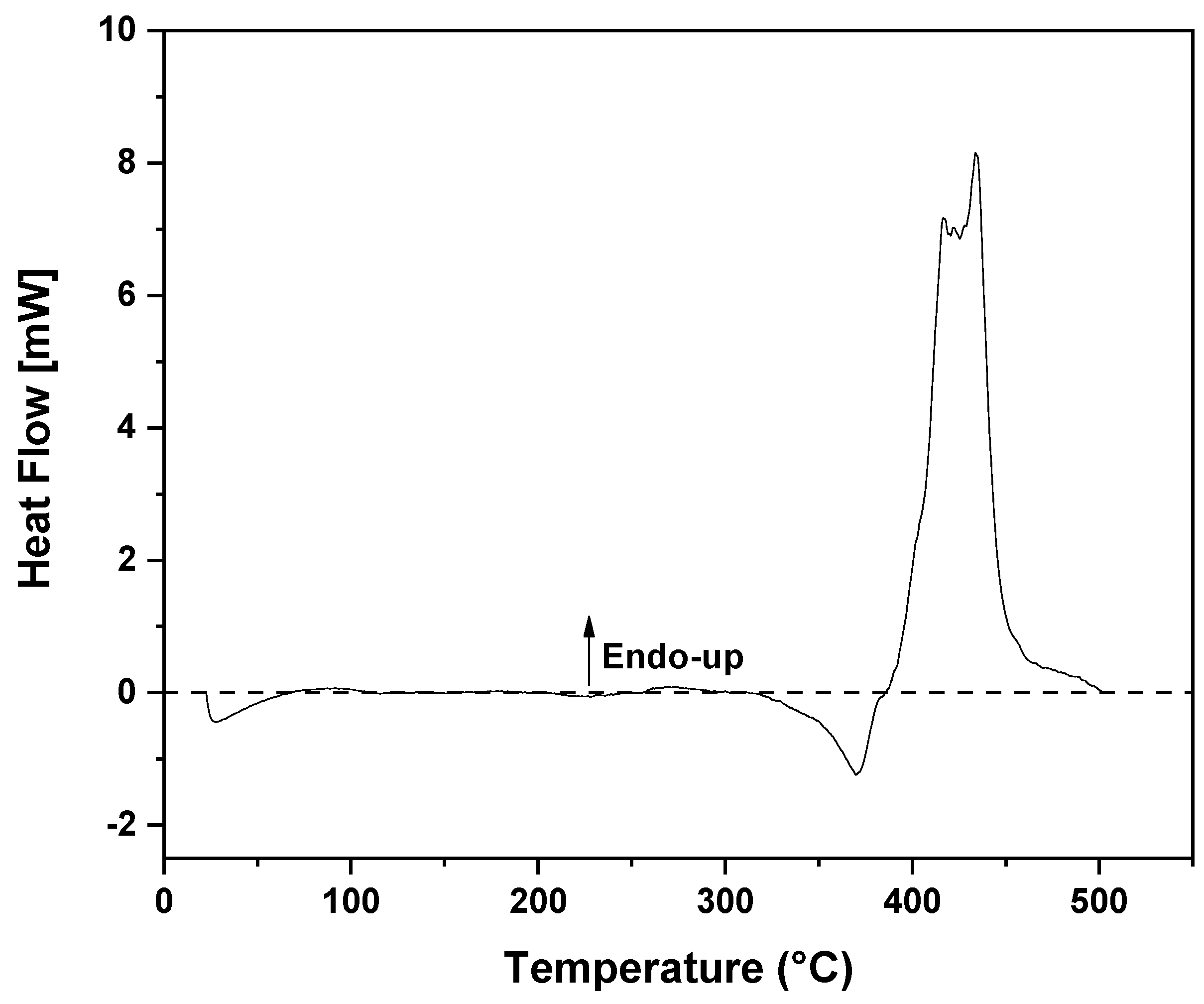

3.1. Thermal Decomposition and Characterization of PMMA Dental Scraps (PMMAW)

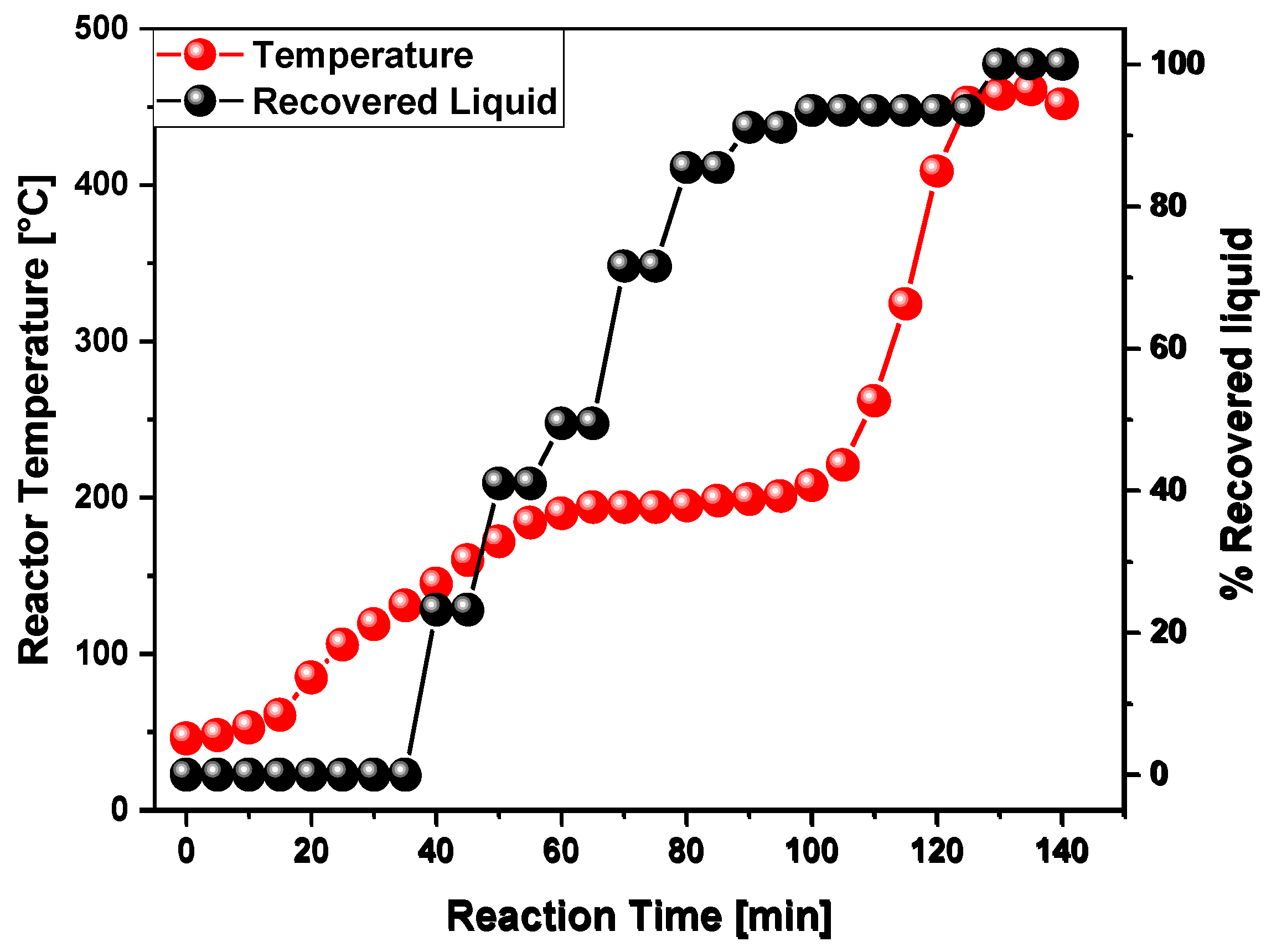

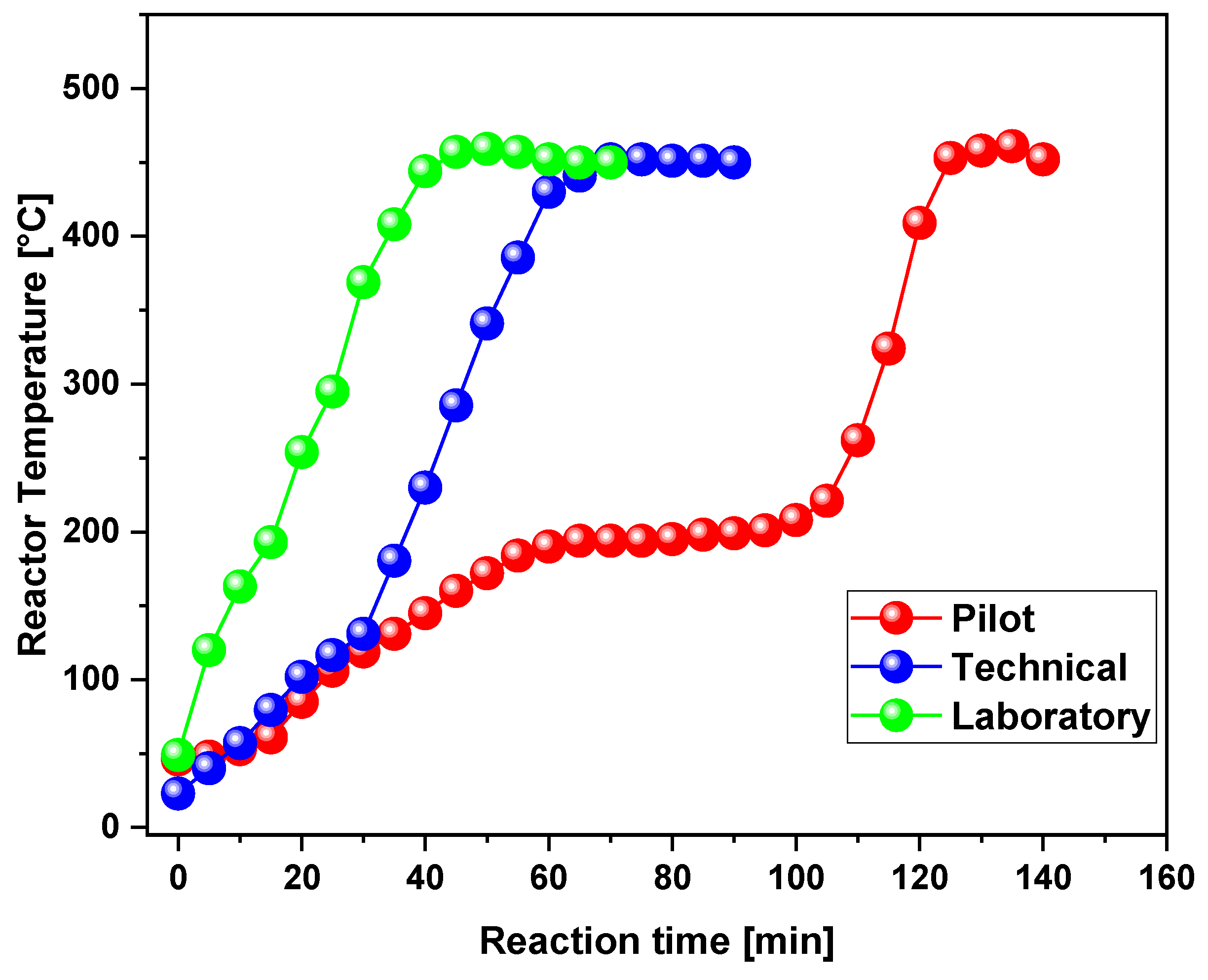

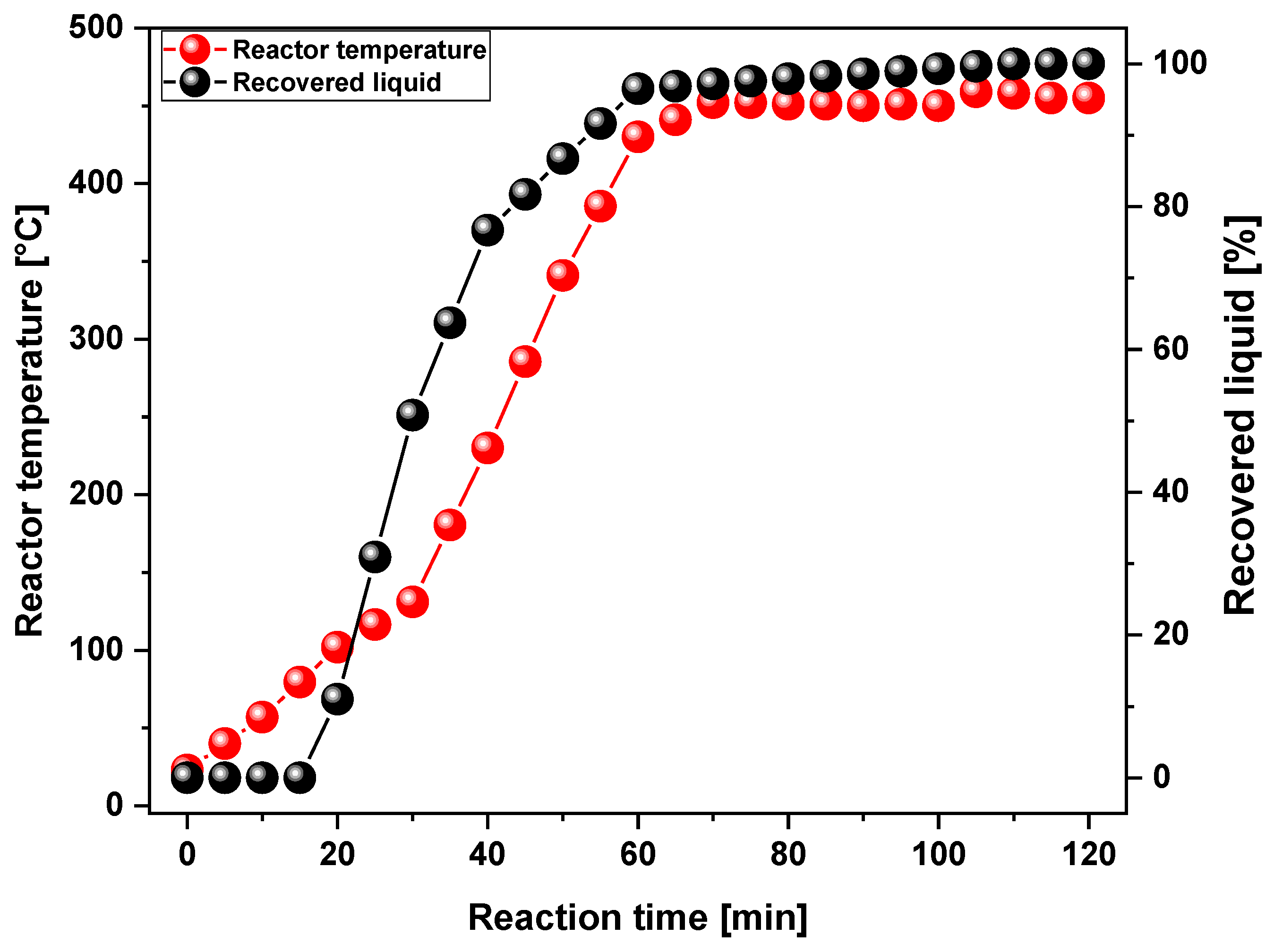

3.2. Process Analysis

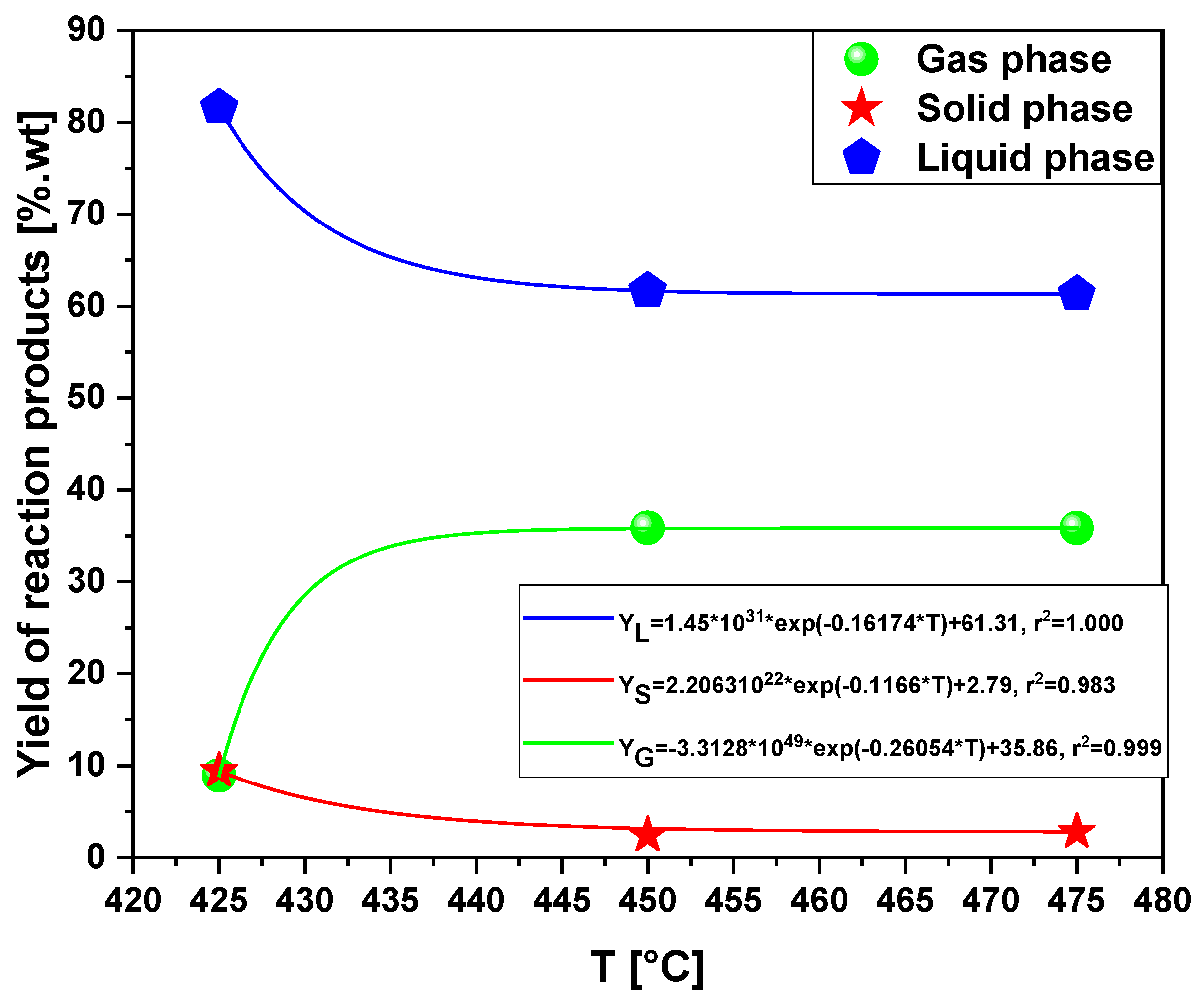

3.2.1. Scaling-Up Effect on the Yield of Products

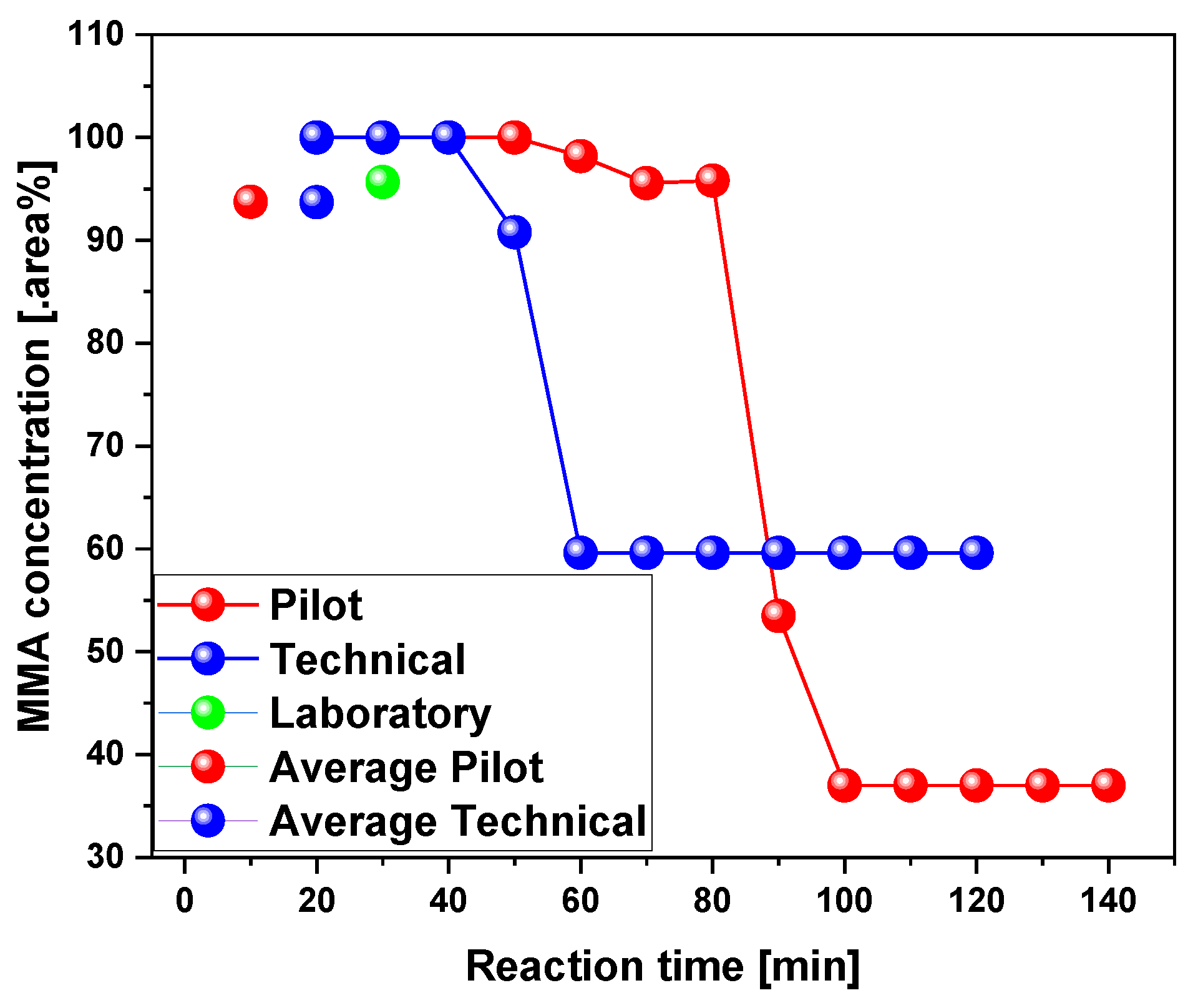

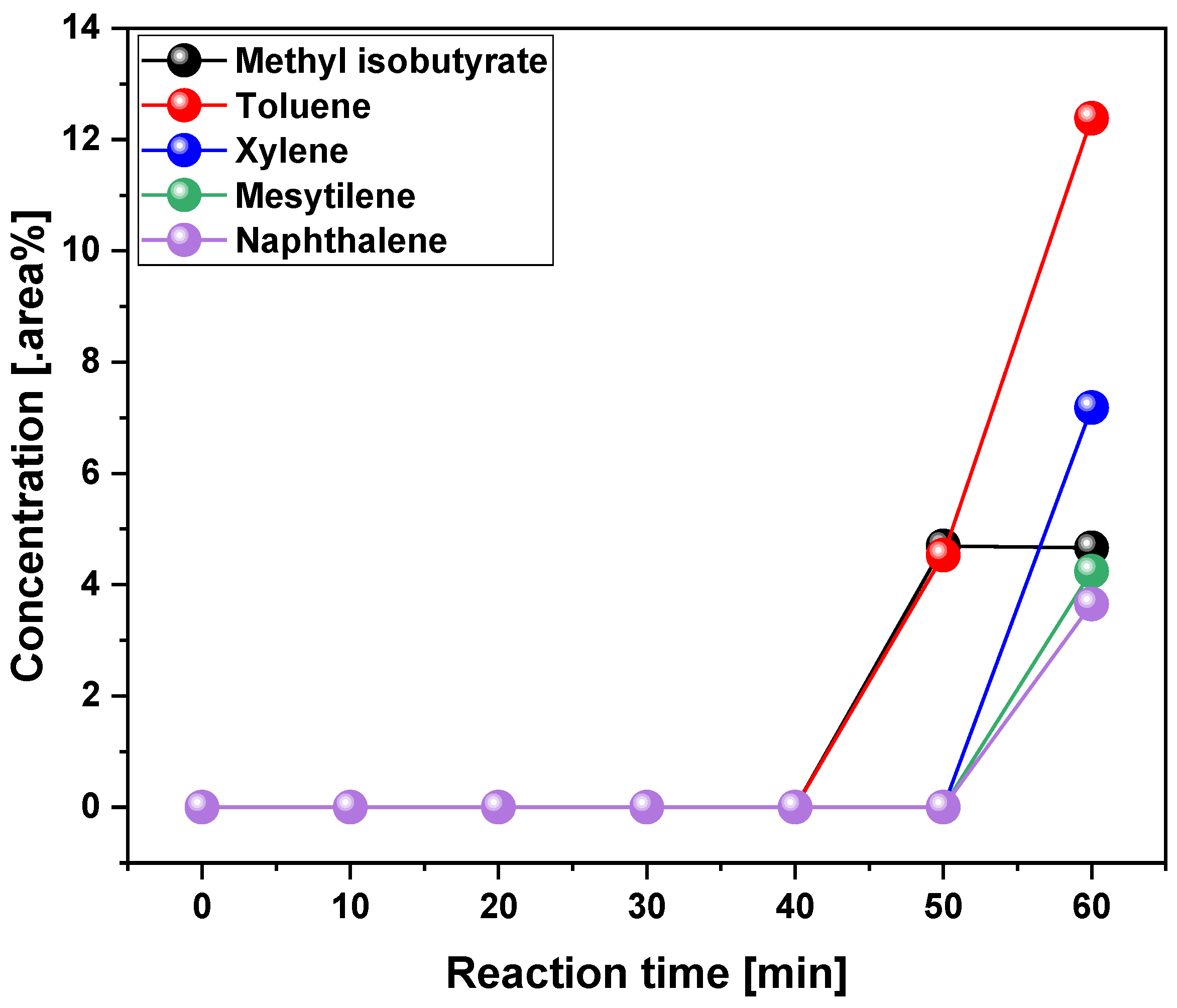

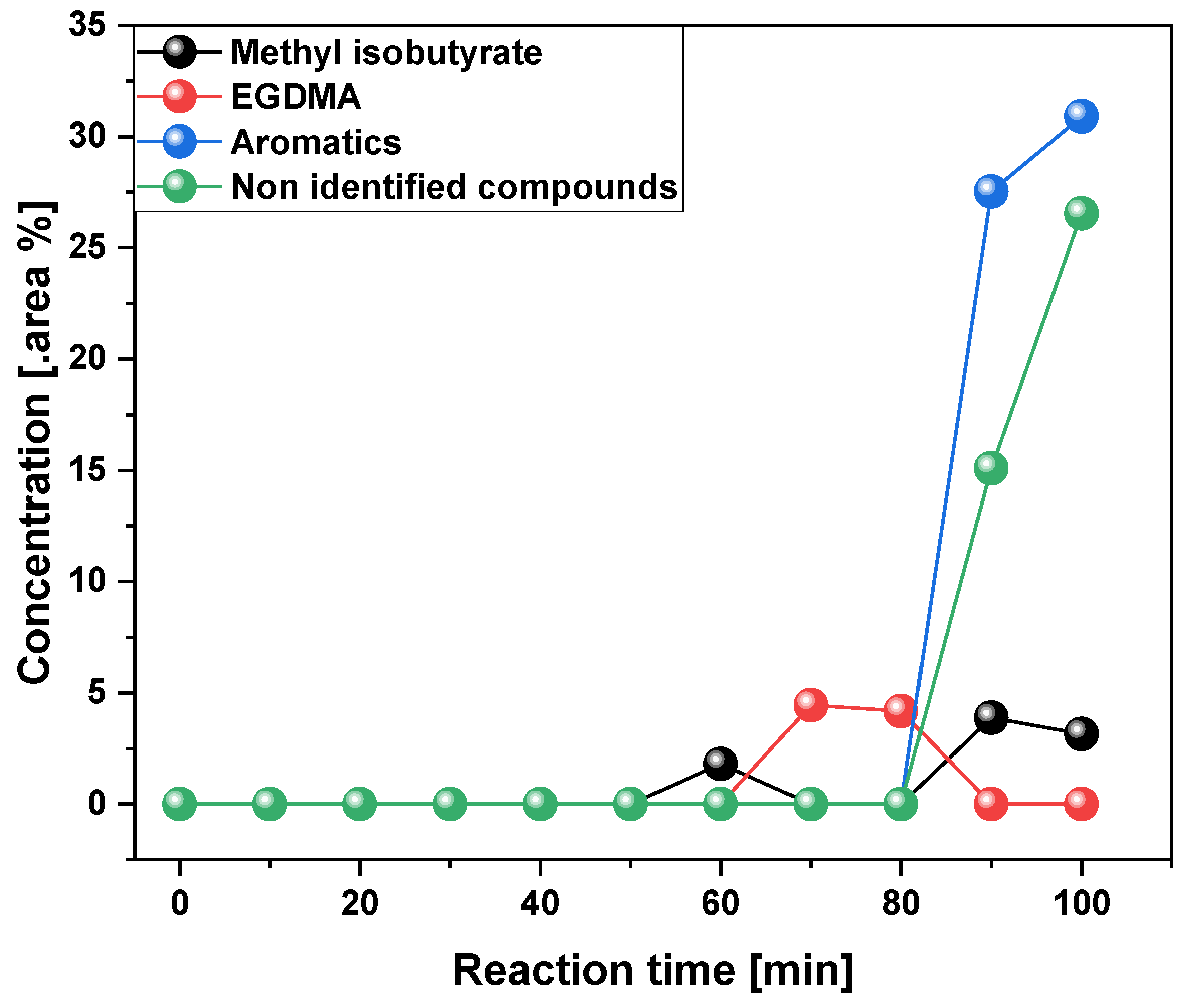

3.2.2. Scaling-Up Effect in Chemical Composition of Liquid Phase

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, L.; Zhou, N.; Lv, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cobb, K.; Chen, P.; Lei, H.; Ruan, R. Pyrolysis Technology for Plastic Waste Recycling: A State-of-the-Art Review. Prog Energy Combust Sci 2022, 93, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Karim, K.J.B.A.; Buang, N.A. A Review of the Properties and Applications of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA). Polymer Reviews 2015, 55, 678–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, R.Q.; Byron, R.T.; Osborne, P.B.; West, K.P. PMMA: An Essential Material in Medicine and Dentistry. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2005, 15, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozum, N.; Safgonul Unal, E.; Altan-Yaycioglu, R.; Gucukoglu, A.; Ozgun, C. Visual Performance of Acrylic and PMMA Intraocular Lenses. Eye (Lond) 2003, 17, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spasojevic, P.; Zrilic, M.; Panic, V.; Stamenkovic, D.; Seslija, S.; Velickovic, S. The Mechanical Properties of a Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Denture Base Material Modified with Dimethyl Itaconate and Di-n-Butyl Itaconate. Int J Polym Sci 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigault, J.; Halle, A. ter; Baudrimont, M.; Pascal, P.Y.; Gauffre, F.; Phi, T.L.; El Hadri, H.; Grassl, B.; Reynaud, S. Current Opinion: What Is a Nanoplastic? Environmental Pollution 2018, 235, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Lehmann, A. Microplastic in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Science (1979) 2020, 368, 1430–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatih Demirbas, M. Biorefineries for Biofuel Upgrading: A Critical Review. Appl Energy 2009, 86, S151–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

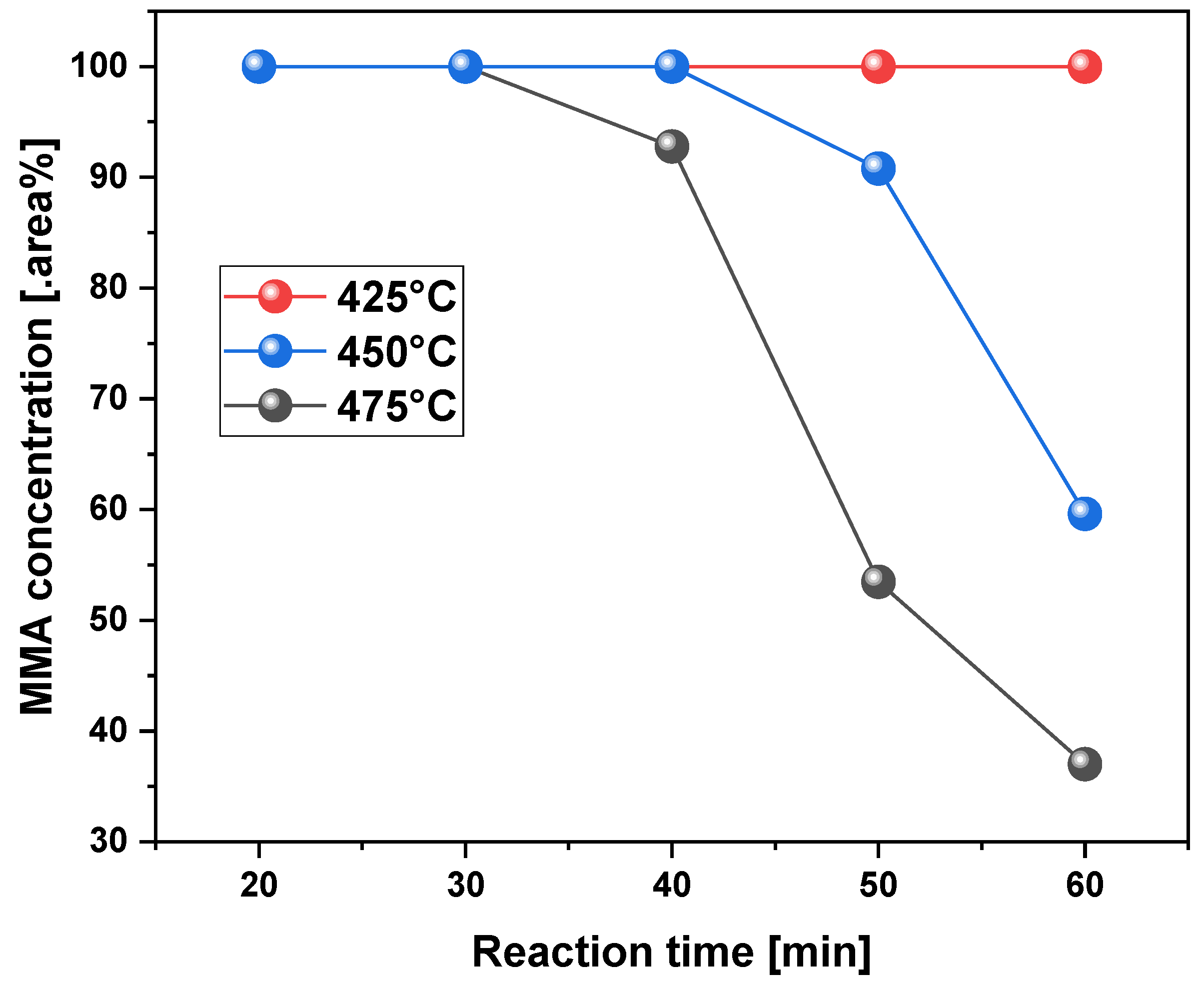

- Dos Santos, P.B.; da Silva Ribeiro, H.J.; Ferreira, A.C.; Ferreira, C.C.; Bernar, L.P.; da Costa Assunção, F.P.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Santos, M.C.; Duvoisin, S.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Process Analysis of PMMA-Based Dental Resins Residues Depolymerization: Optimization of Reaction Time and Temperature. Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 91 2021, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, W.; Predel, M.; Sadiki, A. Feedstock Recycling of Polymers by Pyrolysis in a Fluidised Bed. Polym Degrad Stab 2004, 85, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, W.; Franck, J. Monomer Recovery by Pyrolysis of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA). J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 1991, 19, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KAMINSKY, W. Recycling of Polymers by Pyrolysis. Le Journal de Physique IV 1993, 03, C7-1543–C7-1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisawa, H.; Brill, T.B. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Flash Pyrolysis of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA). Combust Flame 1997, 109, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, W.; Eger, C. Pyrolysis of Filled PMMA for Monomer Recovery. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2001, 58–59, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolders, K.; Baeyens, J. Thermal Degradation of PMMA in Fluidised Beds. Waste Manag 2004, 24, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.S.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J.S. Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Polymers: Kinetics and Recovery of Monomers Using a Fluidized Bed Reactor. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2008, 81, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilias, D.S. Chemical Recycling of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) by Pyrolysis. Potential Use of the Liquid Fraction as a Raw Material for the Reproduction of the Polymer. Eur Polym J 2007, 43, 2564–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.; Artetxe, M.; Amutio, M.; Elordi, G.; Aguado, R.; Olazar, M.; Bilbao, J. Recycling Poly-(Methyl Methacrylate) by Pyrolysis in a Conical Spouted Bed Reactor. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification 2010, 49, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, E.; Olah, M.; Ronkay, F.; Miskolczi, N.; Blazso, M. Characterization of the Liquid Product Recovered through Pyrolysis of PMMA–ABS Waste. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2011, 92, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braido, R.S.; Borges, L.E.P.; Pinto, J.C. Chemical Recycling of Crosslinked Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) and Characterization of Polymers Produced with the Recycled Monomer. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2018, 132, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.R.; Li, S.F.; Chow, W.K. Review on Chemical Reactions of Burning Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) PMMA. 2002, 20, 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T.; Kashiwagi, T.; Brown, J.E. Thermal and Oxidative Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate): Weight Loss. Macromolecules 1985, 18, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manring, L.E. Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). 2. Vinyl-Terminated Polymer. A. Rev. Plast. Mod 1969, 19, 1515. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.D.; Vyazovkin, S.; Wight, C.A. Kinetic Study of Stabilizing Effect of Oxygen on Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1999, 103, 8087–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.H.; Chen, C.Y. The Effect of End Groups on the Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). Polym Degrad Stab 2003, 82, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriol, M.; Gentilhomme, A.; Cochez, M.; Oget, N.; Mieloszynski, J.L. Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA): Modelling of DTG and TG Curves. Polym Degrad Stab 2003, 79, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Kaneko, T.; Hou, D.; Nakada, M. Kinetics of Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Studied with the Assistance of the Fractional Conversion at the Maximum Reaction Rate. Polym Degrad Stab 2004, 84, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motaung, T.E.; Luyt, A.S.; Bondioli, F.; Messori, M.; Saladino, M.L.; Spinella, A.; Nasillo, G.; Caponetti, E. PMMA–Titania Nanocomposites: Properties and Thermal Degradation Behaviour. Polym Degrad Stab 2012, 97, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateh, T.; Richard, F.; Rogaume, T.; Joseph, P. Experimental and Modelling Studies on the Kinetics and Mechanisms of Thermal Degradation of Polymethyl Methacrylate in Nitrogen and Air. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2016, 120, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Van Hees, P.; Andersson, B. Pyrolysis Modeling of PVC and PMMA Using a Distributed Reactivity Model. Polym Degrad Stab 2016, 129, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Pan, Y.; Yao, J.; Wang, X.; Pan, F.; Jiang, J. Mechanisms and Kinetics Studies on the Thermal Decomposition of Micron Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) and Polystyrene. J Loss Prev Process Ind 2016, 40, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, B.J.; Hay, J.N. The Kinetics and Mechanisms of the Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Studied by Thermal Analysis-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Polymer (Guildf) 2001, 42, 4825–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlem, S.; Aslan-Gürel, E.; Rossi, R.M.; Hacaloglu, J. Thermal Degradation of Poly(Isobornyl Acrylate) and Its Copolymer with Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) via Pyrolysis Mass Spectrometry. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2013, 100, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özlem-Gundogdu, S.; Gurel, E.A.; Hacaloglu, J. Pyrolysis of of Poly(Methy Methacrylate) Copolymers. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2015, 113, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manring, L.E. Thermal Degradation of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). 4. Random Side-Group Scissiont. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 3304–3309. [Google Scholar]

- Godiya, C.B.; Gabrielli, S.; Materazzi, S.; Pianesi, M.S.; Stefanini, N.; Marcantoni, E. Depolymerization of Waste Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Scraps and Purification of Depolymerized Products. J Environ Manage 2019, 231, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, V.; Vasile, C.; Brebu, M.; Popescu, G.L.; Moldovan, M.; Prejmerean, C.; Stǎnuleţ, L.; Trişcǎ-Rusu, C.; Cojocaru, I. The Characterization of Recycled PMMA. J Alloys Compd 2009, 483, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grause, G.; Predel, M.; Kaminsky, W. Monomer Recovery from Aluminium Hydroxide High Filled Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) in a Fluidized Bed Reactor. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2006, 75, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newborough, M.; Highgate, D.; Vaughan, P. Thermal Depolymerisation of Scrap Polymers. Appl Therm Eng 2002, 22, 1875–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Tsuji, T. POLY(METHYL METHACRYLATE) PYROLYSIS BY TWO FLUIDIZED BED PROCESS.

- Zeng, W.R.; Li, S.F.; Chow, W.K. Preliminary Studies on Burning Behavior of Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). 2002; 20, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xu, M. Kinetic and Volatile Products Study of Micron-Sized PMMA Waste Pyrolysis Using Thermogravimetry and Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis. Waste Management 2020, 113, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D. Pyrolysis Kinetics and Reaction Mechanism of Representative Non-Charring Polymer Waste with Micron Particle Size. Energy Convers Manag 2019, 198, 111923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayarama Krishna, J. V.; Srivatsa Kumar, S.; Korobeinichev, O.P.; Vinu, R. Detailed Kinetic Analysis of Slow and Fast Pyrolysis of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate)-Flame Retardant Mixtures. Thermochim Acta 2020, 687, 178545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsin, G. Assessing Thermal Behaviours of Cellulose and Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) during Co-Pyrolysis Based on an Unified Thermoanalytical Study. Bioresour Technol 2020, 300, 122700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobeinichev, O.P.; Paletsky; Gonchikzhapov, M.B.; Glaznev, R.K.; Gerasimov, I.E.; Naganovsky, Y.K.; Shundrina, I.K.; Snegirev, A.Y.; Vinu, R. Kinetics of Thermal Decomposition of PMMA at Different Heating Rates and in a Wide Temperature Range. Thermochim Acta 2019, 671, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, S.; Braido, R.S.; de Souza e Castro, N.L.; Brandão, A.L.T.; Schwaab, M.; Pinto, J.C. Modelling the Chemical Recycling of Crosslinked Poly (Methyl Methacrylate): Kinetics of Depolymerisation. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2019, 144, 104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, J.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, H.J.; Oh, S.C. Methyl Methacrylate (MMA) and Alumina Recovery from Waste Artificial Marble Powder Pyrolysis. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 2021, 23, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snegirev, A.Y.; Talalov, V.A.; Stepanov, V. V.; Korobeinichev, O.P.; Gerasimov, I.E.; Shmakov, A.G. Autocatalysis in Thermal Decomposition of Polymers. Polym Degrad Stab 2017, 137, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handawy, M.K.; Snegirev, A.Y.; Stepanov, V. V; Talalov, V.A. Kinetic Modeling and Analysis of Pyrolysis of Polymethyl Methacrylate Using Isoconversional Methods. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021, 1100, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Pan, R.; Li, Q. Thermal Degradation Characteristics, Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Micron-Sized PMMA in Oxygenous Atmosphere Using Thermogravimetry and Deconvolution Method Based on Gauss Function. J Loss Prev Process Ind 2021, 71, 104488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, W. Thermal Recycling of Polymers. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 1985, 8, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Zhou, R.; Miao, F. Experimental and Numerical Simulation Study of Typical Semi-Transparent Material Pyrolysis with in-Depth Radiation Based on Micro and Bench Scales. Energy 2022, 258, 124863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, D.M.; Lehrle, R.S. A New Approach for Measuring the Rate of Pyrolysis of Cross-Linked Polymers: Evaluation of Degradation Rate Constants for Cross-Linked PMMA. Polym Degrad Stab 1998, 62, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Costa, A.F.; Ferreira, C.C.; da Paz, S.P.A.; Santos, M.C.; Moreira, L.G.S.; Mendonça, N.M.; da Costa Assunção, F.P.; de Freitas, A.C.G.d.A.; Costa, R.M.R.; de Sousa Brandão, I.W.; et al. Catalytic Upgrading of Plastic Waste of Electric and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Pyrolysis Vapors over Si–Al Ash Pellets in a Two-Stage Reactor. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.C.; Bernar, L.P.; de Freitas Costa, A.F.; da Silva Ribeiro, H.J.; Santos, M.C.; Moraes, N.L.; Costa, Y.S.; Baia, A.C.F.; Mendonça, N.M.; da Mota, S.A.P.; et al. Improving Fuel Properties and Hydrocarbon Content from Residual Fat Pyrolysis Vapors over Activated Red Mud Pellets in Two-Stage Reactor: Optimization of Reaction Time and Catalyst Content. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Bernar, L.; Campos Ferreira, C.; Fernando de Freitas Costa, A.; Jorge da Silva Ribeiro, H.; Gomes dos Santos, W.; Martins Pereira, L.; Mathias Pereira, A.; Lobato Moraes, N.; Paula da Costa Assunção, F.; Alex Pereira da Mota, S.; et al. Catalytic Upgrading of Residual Fat Pyrolysis Vapors over Activated Carbon Pellets into Hydrocarbons-like Fuels in a Two-Stage Reactor: Analysis of Hydrocarbons Composition and Physical-Chemistry Properties. Energies 2022, Vol. 15, Page 4587 2022, 15, 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Mota, S.A.P.; Mancio, A.A.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; de Abreu, D.H.; da Silva, M.S.; dos Santos, W.G.; de Castro, D.A.R.; de Oliveira, R.M.; Araújo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Production of Green Diesel by Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Crude Palm Oil (Elaeis Guineensis Jacq) in a Pilot Plant. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2014, 110, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel Valdez, G.; Valois, F.; Bremer, S.; Bezerra, K.; Hamoy Guerreiro, L.; Santos, M.; Bernar, L.; Feio, W.; Moreira, L.; Mendonça, N.; et al. Improving the Bio-Oil Quality of Residual Biomass Pyrolysis by Chemical Activation: Effect of Alkalis and Acid Pre-Treatment. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha de Castro, D.; da Silva Ribeiro, H.; Hamoy Guerreiro, L.; Pinto Bernar, L.; Jonatan Bremer, S.; Costa Santo, M.; da Silva Almeida, H.; Duvoisin, S.; Pizarro Borges, L.; Teixeira Machado, N. Production of Fuel-Like Fractions by Fractional Distillation of Bio-Oil from Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Seeds Pyrolysis. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Almeida, H.; Corrêa, O.A.; Eid, J.G.; Ribeiro, H.J.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Pereira, M.S.; Pereira, L.M.; de Andrade Mâncio, A.; Santos, M.C.; da Silva Souza, J.A.; et al. Production of Biofuels by Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Scum from Grease Traps in Pilot Scale. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2016, 118, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Almeida, H.; Corrêa, O.A.; Ferreira, C.C.; Ribeiro, H.J.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Pereira, M.S.; de Andrade Mâncio, A.; Santos, M.C.; da Mota, S.A.P.; da Silva Souza, J.A.; et al. Diesel-like Hydrocarbon Fuels by Catalytic Cracking of Fat, Oils, and Grease (FOG) from Grease Traps. Journal of the Energy Institute 2017, 90, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Lourenço, R.M.; de Abreu, D.H.; Pereira, A.M.; de Castro, D.A.R.; Pereira, M.S.; Almeida, H.S.; Mâncio, A.A.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; da Mota, S.A.P.; et al. Gasoline-like Hydrocarbons by Catalytic Cracking of Soap Phase Residue of Neutralization Process of Palm Oil ( Elaeis Guineensis Jacq). J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2017, 71, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, A.; Lehrle, R.S.; Robb, J.C.; Sunderland, D. Polymethylmethacrylate Degradation—Kinetics and Mechanisms in the Temperature Range 340° to 460°C. Polymer (Guildf) 1967, 8, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Arun, S.; Upadhyaya, P.; Pugazhenthi, G. Properties of PMMA/Clay Nanocomposites Prepared Using Various Compatibilizers. International Journal of Mechanical and Materials Engineering 2015, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, R.; Zhao, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Zhuo, Y.; Chen, C. Investigation of Heat of Biomass Pyrolysis and Secondary Reactions by Simultaneous Thermogravimetry and Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Fuel 2014, 134, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, E.; Picken, S.J.; van Esch, J.H. Analysis of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Determining the Transition Temperatures, and Enthalpy and Heat Capacity Changes in Multicomponent Systems by Analytical Model Fitting. J Therm Anal Calorim 2023, 148, 12393–12409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseli, Y.; van Oijen, J.A.; de Goey, L.P.H. Modeling Biomass Particle Pyrolysis with Temperature-Dependent Heat of Reactions. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2011, 90, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlou, K.; Schneider, H.A. DSC and P-V-T Study of PVC/PMMA Blends. J Therm Anal Calorim 2000, 59, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poomalai, P.; Varghese, T.O. Thermomechanical Behaviour of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate)/Copoly(Ether-Ester) Blends. ISRN Materials Science 2011, 2011, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Shukla, P.; Gaur, M. Thermal Analysis of Polymer Blends and Double Layer by DSC. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2021, 29, S11–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, B.; Bednarski, H.; Jarka, P.; Janeczek, H.; Godzierz, M.; Tański, T. Thermal and Optical Properties of PMMA Films Reinforced with Nb2O5 Nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 22531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Ouyang, Q.; He, L.; Huang, Q. Optical and Thermal Properties of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) Bearing Phenyl and Adamantyl Substituents. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2022, 653, 130018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, H. Crosslinked Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) with Perfluorocyclobutyl Aryl Ether Moiety as Crosslinking Unit: Thermally Stable Polymer with High Glass Transition Temperature. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 1981–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Xie, Z.; Yin, Y.; Yi, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Y. Aging Behavior and Lifetime Prediction of PMMA under Tensile Stress and Liquid Scintillator Conditions. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 2019, 2, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chat, K.; Tu, W.; Beena Unni, A.; Adrjanowicz, K. Influence of Tacticity on the Glass-Transition Dynamics of Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA) under Elevated Pressure and Geometrical Nanoconfinement. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 8526–8537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreozzi, L.; Faetti, M.; Giordano, M.; Palazzuoli, D. Enthalpy Recovery in Low Molecular Weight PMMA. J Non Cryst Solids 2003, 332, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiola, G.J.; Chaudhari, D.M.; Stoliarov, S.I. Comparison of Pyrolysis Properties of Extruded and Cast Poly(Methyl Methacrylate). Fire Saf J 2021, 120, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; Lázaro, D.; Lázaro, M.; Alvear, D. Self-Heating Evaluation on Thermal Analysis of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) and Linear Low-Density Polyethylene (LLDPE). J Therm Anal Calorim 2022, 147, 10067–10081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-H.; Su, W.; Hu, S.-Y.; Huang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Chang, S.-C.; Shu, C.-M. Pyrolysis Characteristics and Kinetics of Polymethylmethacrylate-Based Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Battery. J Therm Anal Calorim 2022, 147, 12019–12032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.-Y.; Feng, X.-B.; Cao, J.-P.; Tang, W.; Wang, Z.-H.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, J.-P.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Wang, Y.-J.; Zhao, X.-Y. Catalytic Conversion of Coal and Biomass Volatiles: A Review. Energy & Fuels 2020, 34, 10307–10363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Wan, S.-W. China’s Motor Fuels from Tung Oil. Ind Eng Chem 1947, 39, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | PMMA type | Temp. (°C) | YLP (%) |

%MMA (.wt%) |

Reactor Type | Process Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | PMMA waste | 345-420 | 48.2-55.5 | 83-98 | Fixed bed | Pilot (143 L) |

| [10] | Filled PMMA | 450 | 82.4 | 57.9 | Fluidized bed | Lab (3 Kg/h) |

| [11] | PMMA waste | 490 | 92.1 | 91 | Fluidized bed | Lab (3 Kg/h) |

| [12] | PMMA waste | 450 | 98.6 | 97.2 | Fluidized bed | Lab (3 Kg/h) |

| [14] | Filled and pure PMMA | 450-480 | 94.7-96.2 (filled); 97.5-99.2 (pure) | 86.6-90.5 (filled); 93.7-98.4 (pure) | Fluidized bed | Lab (3 Kg/h) |

| [14] | Filled and pure PMMA | 450 | 92.9 (filled); 98.3 (pure) | 83.5 (filled); 96.7 (pure) | Fluidized bed | Pilot (16-34 Kg/h) |

| [15] | Pure PMMA | 450-590 | 57.3-98.5 | 95.8-98.7 | Fluidized bed | Lab (2g) |

| [16] | Pure and waste PMMA | 440-500 | 98.1-99.3 (pure); 96.8-98.4 (waste) | 96.3-97.4 (pure); 95.6-97.3 (waste) | Fluidized bed | Lab (1 Kg/h) |

| [17] | Pure and commercial PMMA | 450 | 99.3 (pure); 98.1 (commercial) | 99.0 (pure); 96.8 (commercial) | Fixed bed | Lab (1.5 g) |

| [18] | Commercial PMMA | 400-550 | 90.8-99.1 | 77.9-86.5 | Conical spouted bed | Lab (1.5 g/min) |

| [20] | Pure and waste PMMA | 250-450 | 9.0-85.0 | 82.2-99.9 | Fixed bed | Lab (30 g) |

| [20] | Waste PMMA | 400 | 66.3 | 76.4 | Fixed bed | Lab (2L) |

| [37] | Pure and waste PMMA | 450 | 90-97 | 90.0-94.8 | Fixed bed | Lab (20g) |

| [38] | Filled PMMA | 400-450 | 18-33 | 53-80 | Fluidized bed | Lab (3 Kg/h) |

| [40] | Pure PMMA | 400 | 95 | 95 | Fluidized bed | Pilot (14.4 Kg/h) |

| [40] | Pure PMMA | 400 | 95 | 94 | Fluidized bed | Industrial (300 Kg/h) |

| [48] | Filled PMMA | 300-500 | 35-97 | 5-88 | Fixed bed | Lab (50 g) |

| Reactor | i.d. (mm) | h (mm) | Volume (L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borossilicate glass | 30 | 150 | 0.1 |

| Technical | 85 | 355 | 2.0 |

| Pilot | 300 | 1800 | 143 |

| Process Conditions | Temperature [°C] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 450 | |||

| Laboratory | Semi-Pilot | Pilot | |

| Mass of feed [g] | 40.00 | 625.00 | 20000 |

| Reactor Volume [L] | 0.1 | 2.0 | 143 |

| Reactor load [Kg/L] | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.14 |

| Power Load [W/Kg] | 20000 | 5600 | 290-1740 |

| Reaction time [min] | 60 | 100 | 130 |

| Temperature of liquid condensation [ °C] | 230 | 109 | 113 |

| Final temperature [°C] | 450 | 455 | 458 |

| Mass of coke [g] | 0.29 | 15.11 | 1700 |

| Mass of liquid [g] | 38.31 | 384.70 | 11836.3 |

| Mass of gas [g] | 1.46 | 223.94 | 6463.7 |

| Yield of liquid [%] | 95.63 | 61.67 | 59.18 |

| Yield of coke [%] | 3.64 | 2.43 | 8.50 |

| Yield of gas [%] | 0.73 | 35.90 | 32.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).