1. Introduction:

Spontaneous Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH) bears profound implications for public health, given its association with a high mortality rate and significant long-term morbidity. As a clinical entity accounting for 10-15% of all strokes, ICH is burdened with a sobering 40-59% mortality rate within the first month following the event, much of which occurs in the first 48 hours.(1, 2)

In the case of morbidity, the primary determinants of the outcome include:

The size of the intracerebral hemorrhage.(3)

The patient's degree of consciousness upon arrival.

The existence or extent of intraventricular bleeding.

Those conjugated with the location of the involved area affect the severity of disabilities and sequels following the incident.(2) According to reports, the percentage of patients who have survived but will regain their functionality is less than 40%.(4)

These grave statistics not only reflect the critical nature of the condition but also the imperative for medical science to forge new paths in treatment and management.

Conventionally, the treatment of spontaneous ICH has been largely supportive, centered on the containment of hematoma expansion, the maintenance of cerebral perfusion, and the prevention of secondary complications.(5) Surgical intervention, an option for select cases, has grappled with inconsistent results in improving patient outcomes.(6, 7) Therefore, it has led to a quest for new pharmacological therapies aimed at mitigating the pathophysiological processes that govern secondary brain injury (8, 9).

Amid this backdrop, deferoxamine emerged as a beacon of hope. Individuals who suffer from ICH are at increased risk of experiencing secondary brain injury due to iron overload (10), an ion known for its oxidative stress properties that increase ferroptosis and autophagy within neural cells. This problem occurs as a result of hemoglobin breakdown within the intracranial bleed and the release of blood components, including hem, iron, and thrombin(11).

Deferoxamine, an FDA-approved pharmaceutical agent for the treatment of iron overload, exhibits the capacity to form a complex with iron ions through a process known as chelation. This can detoxify the brain environment and potentially decrease the oxidative damage that contributes to secondary brain damage(12). Besides its chelation activities, it has been proposed that deferoxamine independently has neuroprotective properties, including anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-apoptotic effects(13).

Supporting this proposition, several in vivo and in vitro as well as animal model studies have been published in reputable scientific journals, which have shown that deferoxamine reduces brain edema and improves neurological functions post-ICH, providing the impetus for consideration of its application in human medicine (1, 14-19). Despite the limited number of human clinical trials on this matter, there is growing optimism due to clinical trial reports such as the i-DEF trial. This trial suggested safety and hinted at therapeutic efficacy in humans, which is promising for the diffusion of this potential therapy from "bench to bedside." (16, 19, 20).

Our investigative stance is that, through the administration of deferoxamine, we may witness a diminution in the post-ICH perihematomal edema and restraint of hematoma expansion evidenced by imaging modalities. Concomitantly, we expect enhancements in neurological function as determined by recognized clinical scoring systems (specifically GCS and GOS), thereby delivering support to our hypothesis that deferoxamine's iron-chelating prowess and other neuroprotective features can translate into tangible clinical benefits so it can be applied in routine medical practice. Our study is reported in accordance with CONSORT guidelines in reporting clinical trial results.

2. Methods

We employed a prospective parallel-cohort design with a 1:1 test-control ratio to investigate the aforementioned parameters.

Subjects of the study were randomly selected through a convenience sampling technique among patients admitted with spontaneous ICH diagnosis in Tabriz University hospitals.

The inclusion criteria for this study consisted of the following:

Patients over 22 years of age

Confirmed spontaneous ICH by CT scan

Possibility of initiation of therapy within 18 hours of symptom onset

Being vitally stable

Granting informed consent to be included in the study

Our study employed a set of exclusion criteria, which are outlined as follows:

Hypersensitivity to deferoxamine

Serum creatinine over 2 mg/dl

The necessity of blood transfusion or hemoglobin less than 9 g/dl upon admission

An INR greater than 1.5

Patients with ICH secondary to brain aneurysmal rupture

Patients with a GCS of less than 6

Thalassemia patients

Patients with dysregulated iron diseases

Patients with a history of hepatorenal disorders

Consumption of iron supplements

History of stroke in the past three months

Patients under treatment with anticoagulant injections

Patients with nervous system disease and disabilities, e.g., parkinsonism and multiple sclerosis

2.1. Sample Size

The sample size, as a surrogate for the larger population under study, must adhere stringently to statistical criteria to enable the generalization of the study results to the population as a whole. Thus, in our study, to achieve a power of at least 90% with a significance level of 0.05, we used the following formula to determine the appropriate sample size.

With reference to this formula and taking into account a predicated 10% drop rate, our final sample size was 21 for each of the test and control groups.

2.2. Randomization

We utilized block permutation randomization to ensure the balance in the sample size by means of age, gender, etc. In this method, every patient was allocated an intervention or control group, and each of them received either deferoxamine or a placebo in addition to routine treatments. Each block consisted of 4 subjects, and for 42 subjects involved in this study, we would need 7 blocks. Then, we ran our blocks through random allocation software to allocate each subject to one of the groups.

2.3. Binding

In our study, only the specialist prescribing the drug was aware of the agent prescribed for the patient, while the clinician recording the result and the patients receiving the treatment were completely unaware of the type of treatment. Hence, our study can be categorized as double-blinded.

2.4. Interventions

For every patient who showed clinical manifestations of a stroke, a brain CT scan was conducted. If the CT scan revealed evidence of spontaneous ICH and the patient met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study, they were informed of the study and its potential benefits and risks. The study was explained thoroughly to ensure the patient fully understood the implications, and informed consent was obtained. If the patient was unable to provide consent due to a low level of consciousness, the next of kin was consulted to obtain informed consent.

After the patient was enrolled in the study, their vital signs, neurological examination, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) were evaluated and recorded. Hematoma volume and location were also recorded as a baseline for further evaluation.

After ensuring patient enrollment and carefully inspecting inclusion and exclusion criteria, patients were admitted to either the neurology or neurosurgery ward. Subsequently, a thorough examination of vital signs, GCS scoring, and neurologic condition was conducted. For patients who met the aforementioned criteria and exhibited symptoms for less than 18 hours, either a placebo or the first dose of deferoxamine was administered based on prior randomization.

According to previous studies, the patients who were assigned to the intervention group were subjected to a continuous infusion of deferoxamine at a rate of 7.5 mg/kg per hour for three days straight, with a maximum daily dosage of 6000 mg to avoid toxicity. On the other hand, the control group was given normal saline as a placebo. Throughout the treatment period, the patients were monitored closely for any changes in their blood pressure and vital signs. If there was a decrease of 20 mmHg in the systolic pressure or a decrease of 10 mmHg in the diastolic pressure, the administration of the drug was halted immediately. Any side effects that were observed during the treatment were recorded diligently for further evaluation.

Throughout the patient's hospitalization, a comprehensive evaluation of their clinical state was conducted daily. This involved a detailed neurological examination and constant monitoring of their GCS score. Moreover, in accordance with the ward's customary practice for stroke patients, a CT scan was carried out on the third and seventh day after admission. This was done to assess the intraparenchymal blood volume and determine the extent of edema surrounding the hematoma. All of these measurements were meticulously recorded.

In the event of any decrease in the GCS score or deterioration of the patient's clinical condition, an immediate CT scan was obtained, and the appropriate interventions were administered.

It is pertinent to mention that none of the participants were deprived of conventional treatment in line with the most reliable and credible guidelines available. The drug under investigation was included as an adjunct to conventional therapy.

The ABC/2 formula was used to measure the volume of the hematoma and the volume of edema peripheral to the hematoma.

In order to assess the efficacy of interventions, we conducted a weekly observation of the Glasgow Outcome Scale, Rankin Scale, and mortality statistics. This procedure was conducted over 30 days post-incident, with information gathered during hospitalization, post-discharge clinic visits, or via phone consultations. To evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions, we performed a weekly monitoring of the Glasgow Outcome Scale, (

Table 1) Rankin Scale, and mortality rates. This process was carried out for 30 days following the incident, with data collected during hospitalization, clinic visits following discharge, or through phone consultations.

During the first 7 days of admission, the Rankin scale was evaluated to ascertain the severity of the patient's disability. This scale ranges from 0, with no unusual neurological symptoms, to 5, which indicates morbid disability, and 6, which indicates death (

Table 2).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The compiled data were meticulously documented using IBM SPSSv.23. The results were presented using appropriate descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation. For examining qualitative variables, a chi-square test was employed. In contrast, for quantitative variables, a t-test was performed for comparative analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results:

3.1. Descriptive Results

The average age of the participants was 61.18±5.41 years. There were 28 males. Their initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score had a mean value of 8.12±1.24. The volume of bleeding was 21.29±5.96 milliliters. Most participants were using anticoagulant medication and had comorbidities, including diabetes, chronic hypertension, and smoking. The time interval between symptom onset and the initiation of medication was 9.59±3.62 hours.

Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the baseline participant information between the intervention and control groups.

Table 3 shows the demographic information of the study participants.

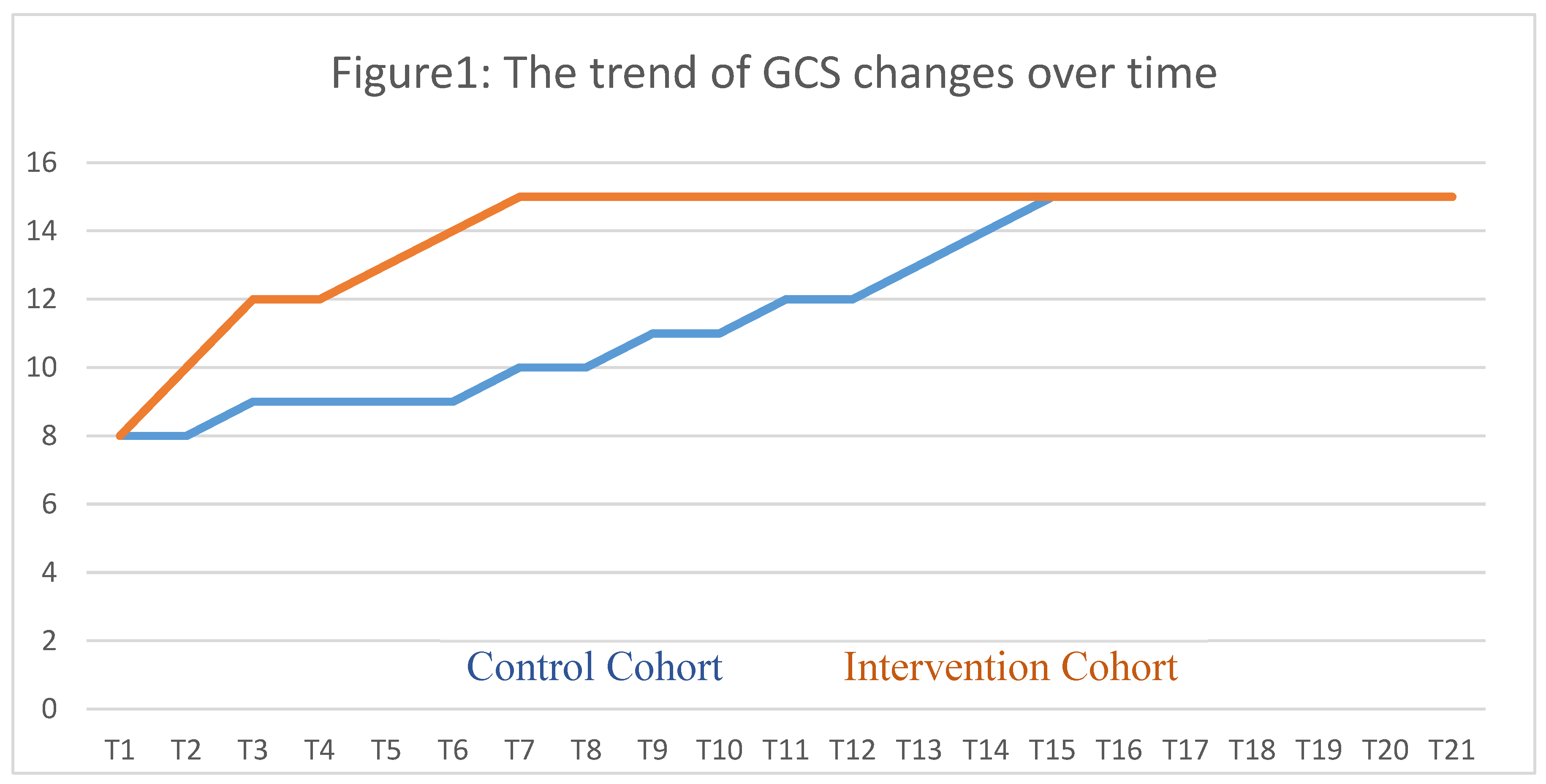

Throughout seven days following the intervention, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of patients was regularly measured and logged every eight hours. The intervention group exhibited a rapid improvement in GCS scores compared to the control group, whose improvement was significantly slower.

Figure 1 illustrates the significant differences in the GCS changes between the groups at all measured time points.

Table 4 presents the mean differences in the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) at baseline and on a daily basis post-intervention. The findings suggest that the intervention group had significantly more GCS changes than the control group in the first four days. However, there was no significant difference in the mean changes from the fourth day onwards.

Upon analyzing the hemorrhage volume on the third and seventh days, it was discovered that the intervention group exhibited significantly lower bleeding than the control group. Furthermore, the intervention group showed significantly lower levels of cerebral edema than the control group during both measured time points.

Table 5 presents a detailed comparison of the hemorrhage volume and cerebral edema at different measurement times between the two groups.

Based on the Rankin scale, disability status was assessed, revealing no significant differences in scores between the groups on the first and second days following the intervention. However, from the third to the seventh days, the intervention group showed significantly better scores than the control group. The comparison of Rankin scale results for both groups can be found in

Table 6.

Patients in the intervention group had a significantly shorter hospitalization duration of 5.62±1.29 days than the control group with 9.14±2.63 days (p=0.001). Additionally, the intervention group had a zero mortality rate at 30 days, whereas the control group had one deceased patient, and this difference was statistically significant (p=0.015). The intervention group also had fewer individuals requiring intubation during the intervention, with only one patient compared to four in the control group, and this difference was statistically significant (p=0.033).

4. Discussion

Our research has yielded valuable insights into the impact of deferoxamine on the treatment of spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH). Our findings demonstrate that administering deferoxamine is effective in enhancing early neurological outcomes in patients with non-traumatic ICH and notably improves radiological indicators compared to the control group. This observation is of utmost significance, as it opens the door to potential therapeutic interventions that may significantly alter the course of recovery following such a devastating event.

Comparing our findings with the existing literature, we see a noteworthy alignment. The efficacy of deferoxamine as a treatment modality in ICH is well-established within the scientific community. Selim et al. (21), Foster et al. (22), and the authors of the i-DEF trial (3) acknowledge the safety and tolerability of deferoxamine mesylate in patients suffering from acute ICH. Furthermore, Keep et al. (11) demonstrated the agent's ability to reduce brain edema, a critical factor in the recovery from ICH.

Deferoxamine has been posited to reduce cerebral edema by facilitating the reduction of free iron levels within the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) following ICH (14). This is a vital consideration, as elevated iron levels post-ICH have been strongly associated with secondary brain injury, as discussed earlier in this article.

Animal models, in particular, have been instrumental in demonstrating that deferoxamine may attenuate brain swelling and neurological deficits. Nakamura et al. (23) found that deferoxamine-induced attenuation of brain edema and neurological deficits were evident in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. This aligns with our findings regarding the improvements in early neurological outcomes.

However, while literature largely supports the use of deferoxamine, some counterarguments need to be acknowledged. There appears to be a concern regarding the optimal dosing and timing of deferoxamine administration, which could induce varying therapeutic outcomes. As detailed in the study protocol by Woo et al. (24), complexities involved in the balance between therapeutic and potentially harmful doses of deferoxamine must be taken into account. Additionally, the ethnic and racial variations in the presentation and severity of ICH, as outlined in the ERICH study (24), suggest that the response to treatment with deferoxamine might also vary across different patient demographics, posing a limitation to the generalization of results.

One of the most promising aspects noted in recent studies, consistent with our findings, is the potential of deferoxamine for improving recovery trajectories post-ICH. Foster et al. (22) conducted a post hoc analysis of the i-DEF Trial and concluded that deferoxamine may positively affect the trajectory of recovery after ICH. This evidence is congruent with the radiological improvements noted in our research.

Indeed, the literature presents a spectrum of results. The consensus tilts toward a positive effect of deferoxamine, yet the degree and consistency of its efficacy seem to vary. For instance, the phase 2 trial included in Lancet Neurology indicates a measured yet substantial optimism for deferoxamine use in an acute setting (3).

From the wealth of data reviewed, the majority seems to support the potential of deferoxamine in mitigating the consequences of spontaneous ICH, which mirrors the conclusions drawn from our investigation. However, it is crucial to address the challenges in terms of dosage and patient-specific factors, which may influence the success of this treatment, as well as potential side effects (25-27). Moreover, it is essential to monitor serious adverse events (SAEs) that might not be solely attributable to deferoxamine but could also be related to the normal evolution of stroke pathology, such as symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, early neurological worsening, and mortality (28). In addition, earlier trials, as reported by Selim et al. [

3], have noted specific adverse effects following deferoxamine administration, particularly at a dosage of 32 mg/kg/day. These effects, observed within 90 days of treatment onset, included anemia, erythema around the administration site, injection extravasation, hypotension, headache, and delirium tremens, occurring in all patients who received this high dosage (29).

Hence, despite the robust collection of data supporting the use of deferoxamine in spontaneous ICH, long-term investigations remain sparse. Our study, along with most available studies, shows promising results. Nevertheless, to recommend deferoxamine as a standard regimen for spontaneous ICH, the scientific community must engage in more extensive, long-term investigational studies. This will help better understand the optimal use of this drug and its long-term implications on patient's health and recovery. In conclusion, while the path forward is illuminated with encouraging findings, the declaration of deferoxamine as a definitive standard care treatment requires a deeper exploration of its long-term benefits and risks.

5. Conclusion

In this rigorous double-blinded randomized clinical trial, we observed that the administration of deferoxamine at a rate of 7.5 mg/kg per hour with a maximum daily dose of 6000 mg had a significant impact on the short-term radiological and neurological outcomes of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage. Thus, deferoxamine can be a promising therapeutic option for improving outcomes in patients with spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mohammad Shirani; Data curation, Fatemeh Jafari and Masoud SohrabiAsl; Formal analysis, Ebrahim Rafiei and Masoud SohrabiAsl; Investigation, Seyed Mohammad Mahdi Hashemi, Farhad Mirzaei, Ali Salami, Ebrahim Rafiei and Masoud SohrabiAsl; Methodology, Ali Meshkini; Project administration, Arad Iranmehr; Resources, Ali Meshkini; Supervision, Arad Iranmehr; Validation, Arad Iranmehr; Writing – original draft, Ebrahim Rafiei; Writing – review & editing, Arad Iranmehr.

Funding

The research reported in this article was not funded by any external sources. Therefore, there are no specific funding agencies that played a role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The work presented herein was conducted independently without financial support from any external entities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical considerations were taken into account throughout the study. Both the intervention and control groups received conventional treatment following the guidelines. The safety of the treatment administered to the test group was evaluated prior to the commencement of the study. The participants were provided with detailed information about the potential benefits and risks of the study, as well as their role and the study procedure. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Data gathering and analysis were conducted with permission from the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences Ethics and Research Committee (IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.142) and the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20190325043107N30). No additional financial burden or radiation exposure was imposed on the patients. Also, they were free to enter or exit the trial at any time.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- de Oliveira Manoel AL, Goffi A, Zampieri FG, Turkel-Parrella D, Duggal A, Marotta TR, et al. The critical care management of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage: a contemporary review. Crit Care. 2016, 20, 272. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togha, M.; Bakhtavar, K. Factors associated with in-hospital mortality following intracerebral hemorrhage: a three-year study in Tehran, Iran. BMC Neurology 2004, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy SB, Cho SM, Gupta A, Shoamanesh A, Navi BB, Avadhani R, et al. A Pooled Analysis of Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Lesions in Patients With Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1390-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasquez F, Chada D, Kellner CP, Majidi S, Sheth KN, Dams O'Connor K, et al. Abstract TP76: Lost To Follow Up As A Missed Opportunity In ICH Survivors. Stroke 2023, 54 (Suppl. 1), ATP76-ATP. [CrossRef]

- Veltkamp, R.; Purrucker, J. Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports 2017, 17, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelow, A.D.; Gregson, B.A.; Fernandes, H.M.; Murray, G.D.; Teasdale, G.M.; Hope, D.T.; et al. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Haemorrhage (STICH): a randomised trial. Lancet 2005, 365, 387–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelow, A.D.; Gregson, B.A.; Rowan, E.N.; Murray, G.D.; Gholkar, A.; Mitchell, P.M. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial lobar intracerebral haematomas (STICH II): a randomised trial. Lancet 2013, 382, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, T.K. Novel Pharmacologic Therapies in the Treatment of Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury: A Review. Journal of Neurotrauma 1993, 10, 215–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belur, P.K.; Chang, J.J.; He, S.; Emanuel, B.A.; Mack, W.J. Emerging experimental therapies for intracerebral hemorrhage: targeting mechanisms of secondary brain injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2013, 34, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbok R, Rass V, Kofler M, Talasz H, Schiefecker A, Gaasch M, et al. Intracerebral Iron Accumulation may be Associated with Secondary Brain Injury in Patients with Poor Grade Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2022, 36, 171-9. [CrossRef]

- Keep, R.F.; Zhou, N.; Xiang, J.; Andjelkovic, A.V.; Hua, Y.; Xi, G. Vascular disruption and blood–brain barrier dysfunction in intracerebral hemorrhage. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS 2014, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellotti, D.; Remelli, M. Deferoxamine B: A natural, excellent and versatile metal chelator. Molecules 2021, 26, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakshit, J.; Priyam, A.; Gowrishetty, K.K.; Mishra, S.; Bandyopadhyay, J. Iron chelator Deferoxamine protects human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y from 6-Hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis and autophagy dysfunction. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2020, 57, 126406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, S.; Hua, Y.; Keep, R.F.; Hoff, J.T.; Xi, G. Deferoxamine reduces CSF free iron levels following intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006, 96, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farr, A.C.; Xiong, M.P. Challenges and Opportunities of Deferoxamine Delivery for Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease, Parkinson's Disease, and Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Mol Pharm. 2021, 18, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim, M. Deferoxamine mesylate: a new hope for intracerebral hemorrhage: from bench to clinical trials. Stroke 2009, 40 (Suppl. 3), S90–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayani, P.N.; Bishop, M.C.; Black, K.; Zeltzer, P.M. Desferoxamine (DFO)—Mediated iron chelation: rationale for a novel approach to therapy for brain cancer. J Neurooncol. 2004, 67, 367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.A.; Kim, Y.A.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, K.E.; Kang, J.L.; Park, E.M. Iron released from reactive microglia by noggin improves myelin repair in the ischemic brain. Neuropharmacology, 2018; 133, 202–215. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.J.; He, H.Y.; Yang, A.L.; Zhou, H.J.; Wang, C.; Luo, J.K., et al.; et al. Efficacy of deferoxamine in animal models of intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review and stratified meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0127256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, M.I.A.; Sitanaya, S.N.; Hakim, A.H.W.; Ramli, Y. The Role of Iron-Chelating Therapy in Improving Neurological Outcome in Patients with Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Evidence-Based Case Report. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, M.; Yeatts, S.; Goldstein, J.N.; Gomes, J.; Greenberg, S.; Morgenstern, L.B.; et al. Safety and tolerability of deferoxamine mesylate in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2011, 42, 3067–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, L.; Robinson, L.; Yeatts, S.D.; Conwit, R.A.; Shehadah, A.; Lioutas, V.; Selim, M. Effect of Deferoxamine on Trajectory of Recovery After Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Post Hoc Analysis of the i-DEF Trial. Stroke 2022, 53, 2204–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Keep, R.F.; Hua, Y.; Schallert, T.; Hoff, J.T.; Xi, G. Deferoxamine-induced attenuation of brain edema and neurological deficits in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2004, 100, 672–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, D.; Rosand, J.; Kidwell, C.; McCauley, J.L.; Osborne, J.; Brown, M.W.; et al. The Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study protocol. Stroke 2013, 44, e120–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wei, R.; Khan, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Iron Neurotoxicity and Protection by Deferoxamine in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022, 15, 927334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, Y.R.; Wu, X.; Du, Z.Y.; Li, Z.Q.; et al. Effects of Deferoxamine Mesylate on Hematoma and Perihematoma Edema after Traumatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage. J Neurotrauma. 2017, 34, 2753–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, C.; Kong, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, G.; Gao, X. The clinical effect of deferoxamine mesylate on edema after intracerebral hemorrhage. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0122371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, M.; DeGregorio-Rocasolano, N.; Pérez de la Ossa, N.; Reverté, S.; Costa, J.; Giner, P.; et al. Targeting Pro-Oxidant Iron with Deferoxamine as a Treatment for Ischemic Stroke: Safety and Optimal Dose Selection in a Randomized Clinical Trial. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, M.; Foster, L.D.; Moy, C.S.; Xi, G.; Hill, M.D.; Morgenstern, L.B.; et al. Deferoxamine mesylate in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage (i-DEF): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 428–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).