1. Introduction

We know intimately the term "atom" which

comes from ancient Greek and means "uncuttable" or translated as

"indivisible." In the early 19th century, the scientist John Dalton

introduced the modern definition of an atom to characterize chemical elements.

It was discovered that Dalton's atoms are not actually indivisible about a

century later. An atom consists of three basic types of subatomic particles:

electrons, protons, and neutrons, which occupy the tiny space in an atom.

Protons and neutrons form the nucleus that contains most of an atom's mass.

Electrons are the lightest charged particles in nature and revolve around the

nucleus of an atom. An electron is seemingly indivisible yet. Until today, we

have not split an electron into two or more smaller particles. We only make the

positive and negative electron annihilation. A free neutron is unstable,

decaying into a proton, electron, and neutrino. However, a free proton is

stable, and is composed of two up quarks and one down quark in the modern Standard

Model. Furthermore, whether a quark can be cut into smaller parts or whether

the matter is infinitely divisible.

This paper tries to answer the above questions from

a different perspective. What will happen when light or electromagnetic,

gravity waves and other waves make up the primary particles that constitute the

fundamental elements of matter? The assumptions are derived then:

Light or electromagnetic waves, weak interaction, gravity, and strong interaction are independent waves without rest masses. But their structures are different.

Light and gravity can be described by the wave equation with the field strength Ê and speed c.

- c

Weak

and strong interaction can be described by the 4-dimensional Laplace equation

with field strength Ê' and speed c'.

- d

According to the unified electro-weak theory, light and weak interaction have the same speed cL with spin number +1 or –1.

- e

Gravity and strong interaction have the same speed cG without spin, and cG is constant in a vacuum.

- f

The primary particles, which are electrons, electron neutrinos, and dark neutrinos in this paper, are made by the above four types of waves.

2. The Formation of Primary Particles

To suppose that the birth of primary particles may

divide into the following two parts:

The

light and weak interaction couple together (hereafter referred to as the E-W

couple) when they have the same spin number and the second-order partial

derivatives of their fields with respect to time

are

equal. The gravity and strong interaction couple together too (hereafter referred

to as the G-S couple) when the second-order partial derivatives of their fields

with respect to time

are

equal. So we have

and

Where

Êe,

Êw,

ÊG, and

ÊS are electric, weak

interaction, gravitational, and strong interaction fields.

The E-W couple has no spin. The original spins of the coupled waves convert the electric or weak charge property.

It

makes a primary particle when the two coupled waves attract each other and

shrink to a tiny sphere. One E-W couple and one G-S couple produce an electron

or a positron whose charge property depends on the original spin

of the E-W couple. The dark

neutrinos are composed of two G-S couples. Two E-W couples with different

original spin compress themselves into an electron neutrino. But they cannot

attract each other with the same original spin.

Further, we assume that each field around the

primary particle is time-independent and spherically symmetrical. Thus, in the

spherical coordinate system, we have the uniform Laplace equation for the above

equations (3), (4)

whose general solution is

where Aj and Bj

are constants, are associated Legendre polynomials, j and k

are integers, j = 0, 1, 2, 3, …, k ≤ j, and j is

called the degree of associated Legendre polynomials.

3. The Fields and Binding-Energy

We can now derive the electric, gravitational, weak

interaction, and strong interaction fields Ê based on equation (6) and

existing physical laws and data.

It is reasonable that equation (6) can be

transformed into a pair of conjugate solutions.

Clearly, there is

where the subscripts

a and

b denote electric, gravitational, weak interaction, or strong interaction.

The field Ê may be split into the macroscopic item and the quantum factors , . The degree of associated Legendre polynomials j rules properties of the field Ê because it is not only an exponent of r in the macroscopic item but also impacts forms of the quantum factors.

Compared equation (7) to Gauss's law of electrostatics and Newton's law of gravity, the electric field

Êe is

and the gravitational field

ÊG is

where '–' means attractive interaction, and '+' means repulsive interaction, as usual in this paper,

is the mathematical electric charge, and

is the mathematical mass or the gravitational charge.

Weak interaction has an intensity of a similar magnitude to the electromagnetic force at very short distances (around 10

-18 meters), but this starts to decrease exponentially with increasing distance. Its effective range is about 10

-17 to 10

-16 meters

[1, 2, 3]. All of the above can help us to determine weak interaction field

Êw from equation (7).

Êw is so supposed to equal to

where

is the mathematical weak charge,

Rcw is the critical radius of weak interaction, and

m is an integer greater than 1.

The strong force is a short-range interaction (around 10

-15 meters) similar to the weak force. But its range is more complex than the weak force. At distances comparable to the diameter of a proton, it is approximately 100 times as strong as the electromagnetic force. At smaller distances, however, it becomes weaker. In particle physics, this effect is known as asymptotic freedom

[4, 5, 6]. Moreover, it is supposed that the fields of the four fundamental forces have a unified form in a very tiny range. Hence equation (6) can be translated into the strong interaction field

ÊS

where

is the mathematical strong charge,

RcS1 and

RcS2 are the 1

st and 2

nd critical radius of the strong interaction, and

n is an integer greater than 1.

Further, it is assumed that RcS1 << Rcw < RcS2 and m ≠ n.

Now we turn to determine the energy. The energy density of wave equation (1) is given by

, and the equations (1) and (2) are Lorentz invariance. So we hope the equation of energy is Lorentz invariance, too, and let the binding-energy

Ea-b of the four fields be

Note that

and

are independent of time, and there are

and

When we use light as a measurement medium to determine the energy as usual, we can translate equation (14) into the spherical coordinate system with the optical medium, which is

where

R is the radius at which two fields begin to interact with each other.

The general energy expression can be calculated when equation (7) is substituted into equation (17).

Based on equation (18) and associated with equations (10) to (13), we first compute the self-binding-energy of the four fields. The self-binding-energy of the four fields

Ee-e,

EG-G,

Ew-w, and

ES-S are

and

The binding-energy of the four fields, such as

Ee-G,

Ee-w,

Ee-S, etc. are

and

For the convenience of subsequent calculations, we require the results of our defined energy to be consistent with those of the conventional physical method. Compared equations (19) and (20) to electric and gravitational potential energy formulas, it can easily find that the relations of mathematical electric charge

ê and mathematical mass

to electric charge

q and mass

m are

and

where

k is the Coulomb constant, and

G is the gravitational constant.

4. The Structures of Primary Particles

A primary particle looks like a tiny spheroidal balloon with two envelopes (

Figure 1). Each of them is made by an E-W couple or a G-S couple. The envelopes can characterize as:

The whole biding-energy of the coupled waves concentrates on the envelopes.

The macroscopic items of combined field strengths of the two coupled waves are equal on the envelopes. Outside the envelopes, the coupled waves become two independent static fields. But there are no fields inside the envelopes.

The size of the envelopes, which means the size of a primary particle, too, depends on the critical radius of weak or strong interaction.

The two envelopes have the same inherent frequency νin, although this is not mathematically required.

The degree of associated Legendre polynomials j is the same on the two envelopes.

Behaviors of the two envelopes obey the Self-Conjugate Mechanism, which requires that one occupies the surface of and the other must take up , or they are conjugate to each other.

Hence, the biding-energy of a primary particle

Epri can be generally described as

based on equation (17)

Epri is clearly equivalent to the rest mass.

Evidently, the total energy of a primary particle comprises the biding-energy or the rest mass and the energy in static fields.

4.1. An Electron Neutrino

An electron neutrino is composed of two E-W couples with different original spin. In order to explore its structure, these assumptions should be adopted:

Its radius re_ν is equal to the critical radius of weak interaction Rcw.

The charges in equations (10) and (12) are equal and minimal for an electron neutrino, which means when and are the mathematical electric charge and the mathematical weak charge of an electron neutrino.

Integrating equations (10), (12), and the above characters, we have two field equations on envelopes of an electron neutrino

ÊE, e_ν

where '–' only indicates that two E-W couples are attracted to each other on the envelopes.

Based on equation (31) and associated equations (19), (21), and (24), we can easily compute the biding-energy of an electron neutrino

Ee_ν.

Combining the envelopes' characters b. with equations (10), (12), and (32), the fields around an electron neutrino

Êe_ν can be directly written as

4.2. Dark Neutrinos

Two G-S couples make a dark neutrino. However, the strong interaction field has two critical radii, so there are two types of dark neutrinos, and they are named Dark I and Dark II. Similar to

Section 4.1, it is assumed that:

The sizes of Dark I and II are equal to the 1st and 2nd critical radius of strong interaction.

Dark I and II have the same mathematical mass and mathematical strong charge.

The mathematical mass and the mathematical strong charge are equal, i.e., . is minimal.

Replicating the process of the previous section, we have the fields of a Dark I on the envelopes

ÊE, D_νI

where '–' only means that two G-S couples are attracted to each other on the envelopes.

Based on equation (31) and associated equations (20), (22), and (27), we can compute the biding-energy of a Dark I

ED_νI

To get the fields of a Dark II on the envelopes

ÊE, D_νII and the biding-energy of a Dark II

ED_νII, we imitate the last process and have

and

Following the computations of the particle external field in the previous section, we can obtain the fields around a Dark I

ÊD_νI

and the fields around a Dark II

ÊD_νII

Comparing equations (36) with (38) reveals that, as far as measurements, namely energy, are concerned, there is little difference between Dark I and Dark II. However, their volumes are significant differences in the microscopic domain. There should only be Dark IIs in most cases following the principle of energy minimization.

4.3. An Electron or A Positron

Electrons and positrons have the same structure. We will not distinguish significantly between electrons and positrons during the subsequent descriptions and computations. One E-W couple and one G-S couple attract each other to form an electron or a positron, so its structure is the most complex in primary particles. Following the assumptions about dark neutrinos, it is supposed that:

The radius of an electron re equals the critical radius of weak interaction Rcw, although there are three critical radii for weak and strong interactions.

The mathematical electric charge and the mathematical weak charge are equal, i.e., .

The mathematical strong charge are minimal, which means .

Referring to the way we did in the previous sections, we can obtain the field of an electron on the envelopes

ÊE, e and the biding-energy of an electron

Ee.

and

According to the previous assumptions

RcS1 <<

Rcw <

RcS2,

, and

, we have

and

Now we directly give the result for fields around an electron

Êe.

Next, the examination of equations (41) and (42) reveals that the 2

nd critical radius of strong interaction

RcS2 should be the geometric characterization parameter of a G-S envelope rather than the 1

st critical radius of strong interaction

RcS1. It is further assumed that

Rcw and

RcS2 are proportional to the wavelengths of the E-W and the G-S couple, respectively, i.e.,

,

. Thus, we can directly write with the envelopes characters d.

which shows that the gravity speed

cG is faster than the light speed

cL when the above equation compares with equation (42).

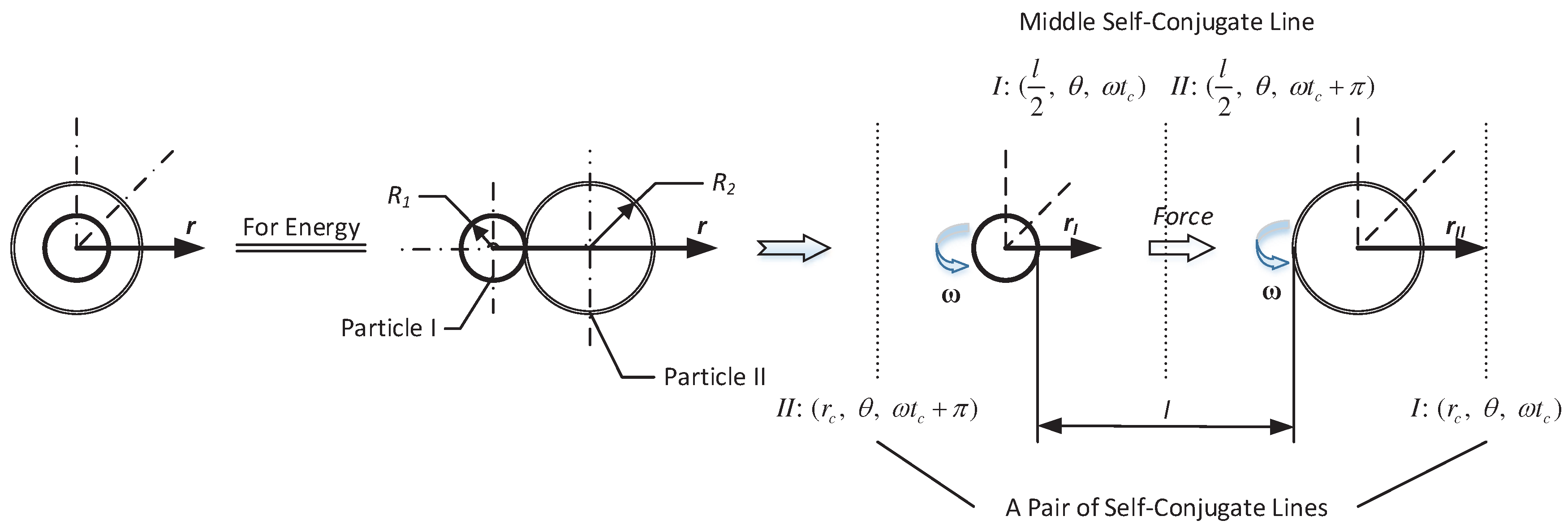

5. The Interactions Between Two Primary Particles

Imagine that two static primary particles are initially rested on each other and then separated by a repulsive force for a distance of

l. Particles I and II have the potential and kinetic energy in the separated state (

Figure 2). At the initial state, particles I and II are equivalent in that they share a common center of the sphere (

Figure 2) because there are no fields in envelopes of primary particles.

Based on the law of conservation of energy, the initial energy of particles I and II is equal to the sum of the potential energy and kinetic energy (including magnetic energy for electrons) after their separation. Therefore, referring to equation (17), the potential energy of the two primary particles

can be defined as

where

and

are the external fields of primary particles I and II,

l is the distance between the two particles (

Figure 2),

Rc is the larger of the two particles’ radii, and

converts to kinetic energy (including magnetic energy for electrons).

Equation (47) must still hold certainly when two primary particles move in the opposite mode of

Figure 2, i.e., two rested on each other particles are attracted at the initial distance

l and approach each other until they come together. It is therefore assumed that the Self-Conjugate Mechanism remains between two interacting primary particles. According to existing physics knowledge, the Self-Conjugate Mechanism makes two sets of fields around one particle conjugate to two sets of fields around another depending on the rotation of two particles. In other words, two particles have achieved the Self-Conjugate after they rotate one cycle with angular velocity

ω. There are Self-Conjugate lines in pairs that are further presumed at

for particle I and

for particle II in their respective spherical coordinate systems, i.e., these lines are in the opposite position while

rI =

rII =

r,

θI =

θII =

θ (Refer to

Figure 2). So when we take the

rI-coordinate system of the particle I as a reference (Refer to

Figure 2), in equation (47), the item

, and the item

where

tc is the time of conjugation of two primary particles, and

η = 0, 1, 2, ……,

η. Hence, equation (47) still holds, just with a minus sign difference. Here, the minus sign only indicates that energy is gathering in this process, contrary to equation (47). Later, we continue to use equation (47) without distinguishing whether the energy is spreading or gathering in the motion of two primary particles.

Thus we can follow the results from the previous chapters when there is the potential energy between two primary particles, and the distance of

l remains constant. There are only two conjugate forms between the two particles because each of the two particles comprises two coupled waves. Hence, equation (47) can be translated into

where the subscripts

a to

d, and

w to

z denote electric, gravitational, weak interaction, or strong interaction.

According to Newtonian mechanics, the work done is the same as the potential energy when primary particles I and II move relative to each other. Reversing the Newtonian mechanics definition of work, i.e.,

, the force between two primary particles

is therefore

Two Self-Conjugate primary particles have no initial phase difference in zenith and azimuthal angle under the requirements of the assumption of Self-Conjugation lines. From equation (48), they have potential energy or force when they rotate in the same direction, while they have zero potential energy or rest when they do in opposite directions. Therefore, the force mode has two forms, all right-handed or up rotation and all left-handed or down rotation, which shows each primary particle has spin values of .

5.1. Two Particles of the Same Type

Start by computing the interaction between two electron neutrinos. Combining equations (19), (21), and (49), we have the potential energy

Ee_ν^e_ν

Since two equations (34) have attractive and repulsive states under the Self-Conjugate Mechanism, from equation (50), the force of two electron neutrinos

Fe_ν^e_ν is

where the sign '–' or '+' depends on the Self-Conjugate forms between two electron neutrinos, and the "–" or "+" should be random.

Association equation (49) with equations (20), (22), (27), and (39), we can compute the potential energy between two Dark Is

ED_νI^D_νI

and the force between two Dark Is

FD_νI^D_νI

Duplicating the last process yields the potential energy between two Dark IIs

ED_νII^D_νII

and the force between two Dark IIs

FD_νII^D_νII

The potential energy between two electrons

Ee^e has two forms because an electron is composed of one E-W couple and one G-S couple. Same as electron neutrinos, the two forms should be random and rely on the Self-Conjugate forms between two electrons. Combining equations (19) to (28) and (49), we can compute the two forms of the potential energy. One is

Ee^eI when the two E-W couples are conjugate, and the two G-S couples are conjugate.

Another is

Ee^eII when the two E-W couples are conjugate to the two G-S couples.

Derivation of the last two equations can yield the forces between two electrons in both forms that are

and

plus

in equations (57) to (60).

Comparing equations (57) and (58), (59) and (60) shows that the potential energy and force between two electrons are very different in the two Self-Conjugate forms, with the smaller one close to zero.

5.2. Two Particles of the Different Type

Similar to the last section, this section still starts by computing the interaction of an electron neutrino with another primary particle. Combining equations (23) to (28), (49), and (50), the potential energy between an electron neutrino and a Dark I

Ee_ν^D_νI is

and the force between an electron neutrino and a Dark I

Fe_ν^D_νI is

plus

in above two equations.

Repeating the previous processes gives the potential energy between an electron neutrino and a Dark II

Ee_ν^D_νII

the force between an electron neutrino and a Dark I

Fe_ν^D_νII

the potential energy between an electron neutrino and an electron

Ee_ν^e

and the force between an electron neutrino and an electro

Fe_ν^e

where

,

, and

in equations (65) and (66), and the sign '–' or '+' randomizes in equation (66).

It is next computed that the potential energies and forces between the two types of dark neutrinos and between each of them and an electron. Based on equations (20), (22), (27), (49), and (50), the potential energy between a Dark I and a Dark II

ED_νI^D_νII is

and the force between a Dark I and a Dark II

FD_νI^D_νII is

Based on equations (23) to (28), (43), (49), and (50), the potential energy between a Dark I and an electron

ED_νI^e is

the force between a Dark I and an electron

FD_νI^e is

the potential energy between a Dark II and an electron

ED_νII^e is

and the force between a Dark II and an electron

FD_νII^e is

6. The Structure Values of Primary Particles

In this chapter, we attempt to import the existing physical data into the computational results of the previous chapters to obtain the structural values of primary particles. Nowadays, we are fully aware of the characteristics of electricity, such as the charge, the potential energy, and the field, at both macro and micro levels. We can be confident that the available measurements reflect the characteristics of the electric charge and no other factors. Thus, comparing equation (45) to Gauss's law of electrostatics and combined equation (29), it can be easily found that the relation of the mathematical electric charge

of an electron to an electron charge

qe in present physical data.

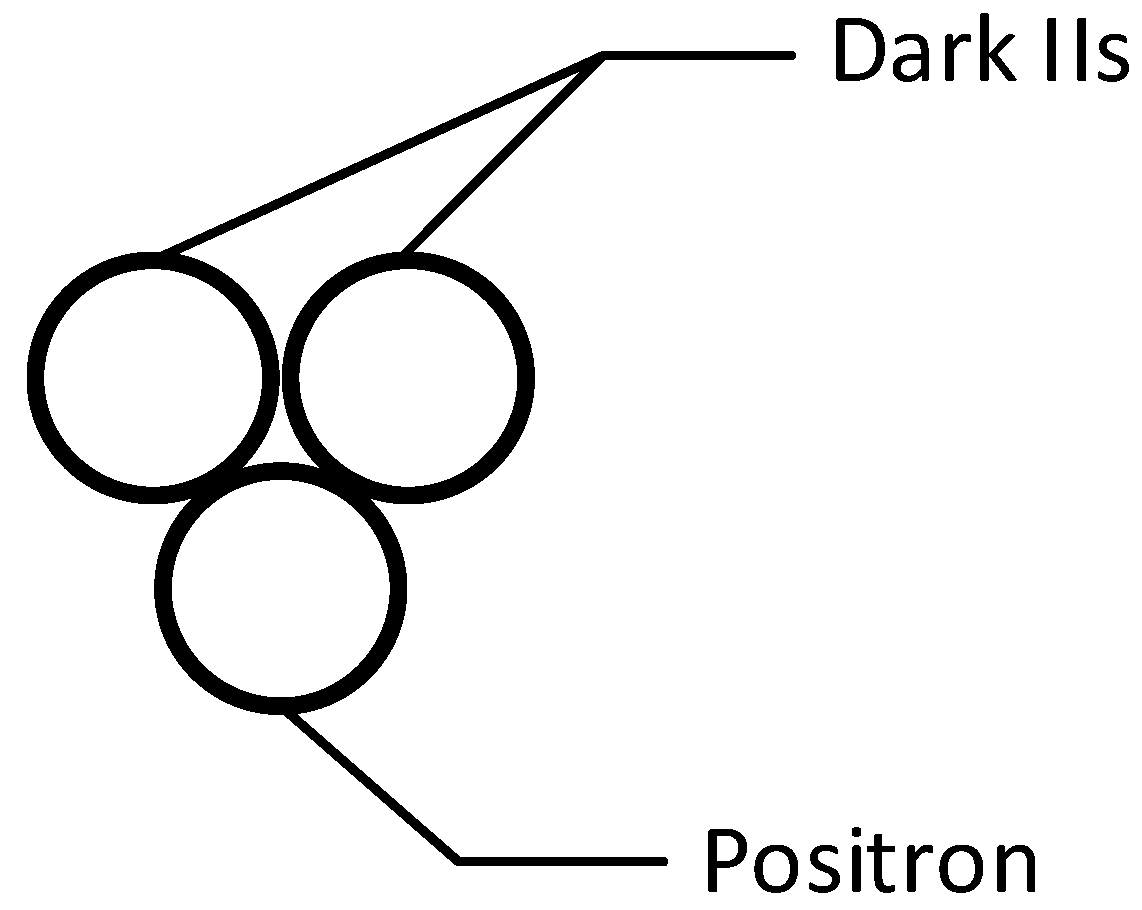

It is somewhat difficult to obtain the charges of gravity and the strong force because gravity is the weakest force in the four fundamental interactions, and the strong force is a short-range interaction. In the models of this paper, although the gravitational and inertial mass are different, it can be hypothesized that Newton's law of gravity is accurate to a large extent because only electron neutrinos in the model do not have gravitational waves and because electron neutrinos have much less biding-energy or rest mass. We focus on protons ---- stable, heavy subatomic particles ---- to explore these charges and start with the components of a proton. A combination of two attractive primary particles is easily separated by external action since there is no third particle to hold it back. However, the aggregation of multiple strongly attracted primary particles can cause the annihilation of these particles. Therefore, a combination of three high biding-energy, mutually attractive primary particles should be an extremely stable particle. Similar to the Quark model[

7], it is supposed that a proton is composed of two Dark IIs and one positron instead of two up quarks and one down quark and has the structure of

Figure 3 that will not delved into.

From equations (55), (56), (71), and (72), a proton might have the structure of

Figure 3, and the mutual distances between the three primary particles are small, i.e.,

, in a proton. It is further supposed that the kinetic energies of the three primary particles' mutual motion (including magnetic energy) are negligibly small compared to their binding-energies and potential energies. Hence, the energy of a proton

Ep equals

when equations (38), (55), and (71) are subsequently substituted in the above equation, and the energy of an electron

Ee is neglected in the above equation because

Ep is 1836 times

Ee (

Ep = 938MeV,

Ee = 0.511MeV)

[7, 8]. Furthermore,

can be obtained from equations (30) and (40), where

mp is the mass of a proton.

Next, by combing equations (43), (44), and (73) to (75), we have

that we can solve and yield

Evidently,

RcS1 is very small from the above equation. Hence

Since in the solution of

RcS1 from equation (76), we actually make

, i.e.,

, which can derive

from

and tell us that

RcS2 and

Rcw are almost equal. This computational procedure is not precise enough, so we use

in equation (76) to solve

RcS2

Based on equation (74) the biding-energy of a Dark II

ED_νII is

From equation (38), the biding-energy of a Dark I

ED_νI is

However, I have not found a way to calculate the energy of an electron neutrino Ee_ν, which also leads to an inability to determine the tiny difference between gravitational and inertial mass, especially when .

It can be determined that m > n since RcS2 ≈ Rcw and the effective range of the weak interaction is smaller than the one of strong interaction. I would suggest further that n = 3 and m = 5 because they seem to fit the current knowledge of strong and weak interactions, and 1, 3, 5 is a tiny, pretty odd series. Of course, exactly how many m, n can only be obtained experimentally.

The gravity speed

cG can easily get from equations (46) and (80)

In addition, the energy definition equations (14) and (17) reveal that regardless of the light speed

cL or the gravity speed

cG, there is an invariant that is the rest mass

m0. Therefore, we can obtain the relation of momentum and energy between

the two measurement media of light and gravitational

waves

from the relationship between momentum and energy

in Special Relativity . Equation (84) directly derives the relation of space-time between

the two measurement media

So the proper time τ is the same in all reference frames with the two measurement media.

7. Conclusions and Discussions

In this paper, field and energy equations for strong and weak interactions are derived based on a set of fundamental assumptions that are consistent with existing knowledge. With the help of these equations, the structures of the primary particles are established, and the interactions between two primary particles are analyzed. The characteristic parameters of the primary particles (

Table 1) are computed from the present physical data.

Moreover, we can derive the matrix when we rewrite the quantum factors in equations (32), (35), (37), and (41) as and multiply it by the Pauli matrix . has well-known results in quantum mechanics with eigenvalues of ±1 and eigenvectors of , , i.e., spin values . Thus the conclusions of this paper are compatible with existing physical-mathematical methods.

Furthermore, the interactive analysis reveals that:

The Self-Conjugation condition is that two primary particles have no initial phase difference in zenith and azimuthal angle. Two Self-Conjugation primary particles have potential energy or force when they rotate in the same direction. However, they have zero potential energy or rest when they spin in opposite directions. It is one of the foundations of the Pauli exclusion principle.

Dark Is have the asymptotic freedom characteristic, but following the principle of energy minimization, there should only be Dark IIs in most cases.

The force between two electrons has three values, one large, one small, and one zero.

Whether two electron neutrinos or an electron neutrino and an electron attract or repel each other is randomized. Because of this, electron neutrinos are a weak destabilizer in the nucleus, and even though the binding-energy of electron neutrinos is the smallest, no signs of neutrino destruction have been found so far.

Primary particles behave perfect tiny spheres in terms of energy and interactions, but they also look like uneven minuscule spheres in external fields. Which is the reality of a primary particle? Observation or mathematics? The answer should be that "the Moon is always there, doesn't matter we see it or not", however, the Moon is changed when we see it.

In the interactive analysis, the Self-Conjugate Mechanism plays a significant role in the microscopic domain. Consider the case when external actions cause a combination of two primary particles to rotate from the same to different directions until they are opposite and separated. So the two primary particles have the opposite direction of spin, or in other words, they entangle themselves after the separation. Evidently, the distance of quantum entanglement is finite, not infinite like currently believed, because the strength of fields around primary particles decreases with distance. The transmission speed of quantum entanglement is the speed of light or gravity. Einstein is right in this case.

In addition, the gravity speed cG is slightly larger than the light speed cL, and the rest mass m0, the proper time τ are the invariants with the two measurement media of light and gravity. Gravity might have similar quantum characteristics, such as . What are the quantum characteristics of weak and strong interactions?

It can be further hypothesized that a dark matter is formed when the positron in a proton is replaced by one Dark II. Therefore, the energy of a dark matter

Edm is

and the mathematical mass of a dark matter

is

from equations (38) and (55). Equations (86) and (87) remind us again that the difference between gravitational and inertial mass is almost negligible. Certainly, it is also reasonable to assume that a combination of three Dark IIs was annihilated by itself, and there are only free-state Dark IIs as dark matters in our cosmic, since no particle heavier than a proton is as stable as a proton. Or, are we listening to a concerto for solo, triple Dark IIs, and conventional matters in our universe today?

Let us imagine now what will happen when all primary particles in our universe will gather, be crushed, till be destroyed at a point. This consequence should be similar to electron annihilation. There will only be the four fundamental waves with vast high energy in our universe at that moment, namely the scene of the Big Bang.

It is worth noting that this paper cannot answer why positrons and negative protons are so rare in our universe, which means Dark IIs incarcerate only positrons.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).