Submitted:

12 January 2024

Posted:

15 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

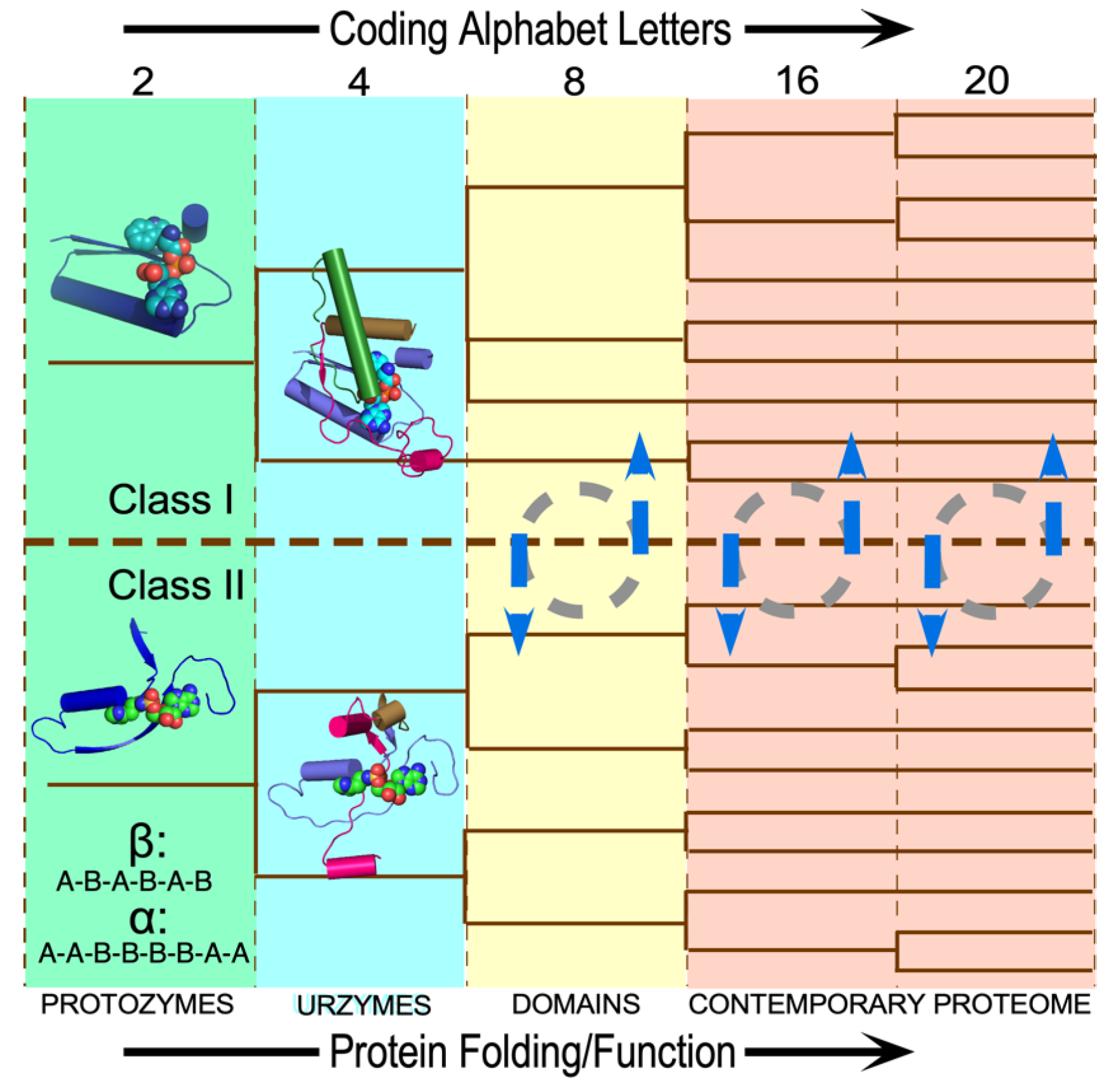

2. Creating the first bit of genetic information

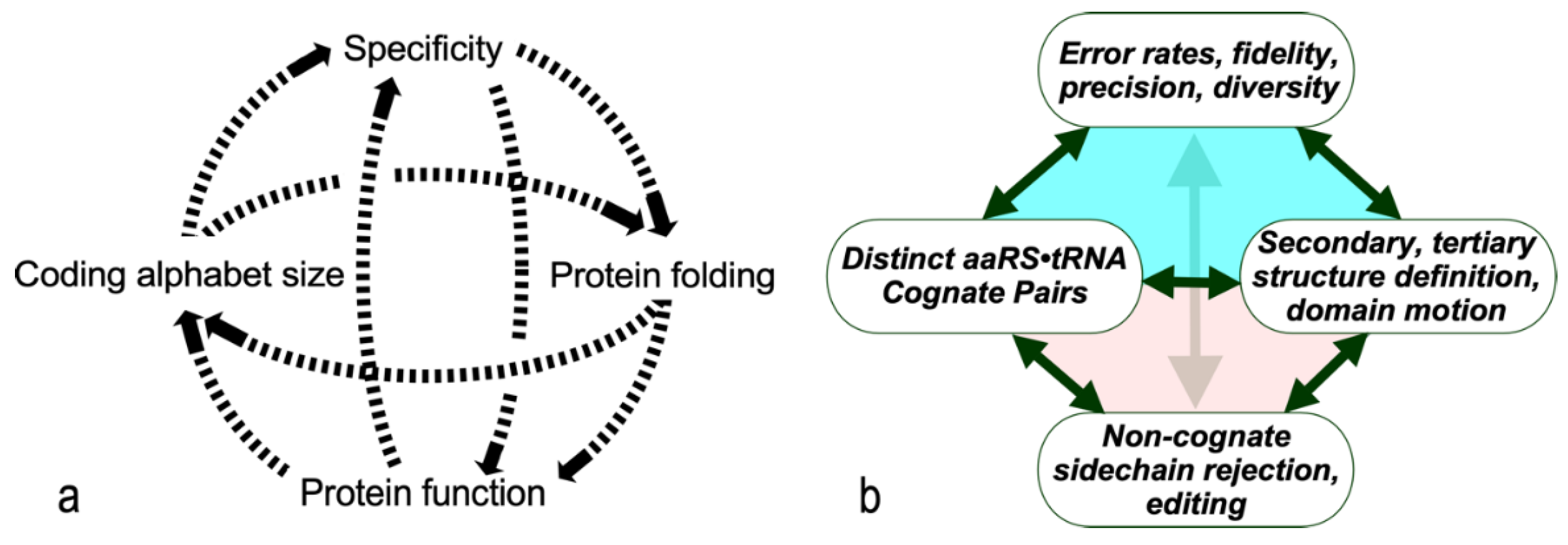

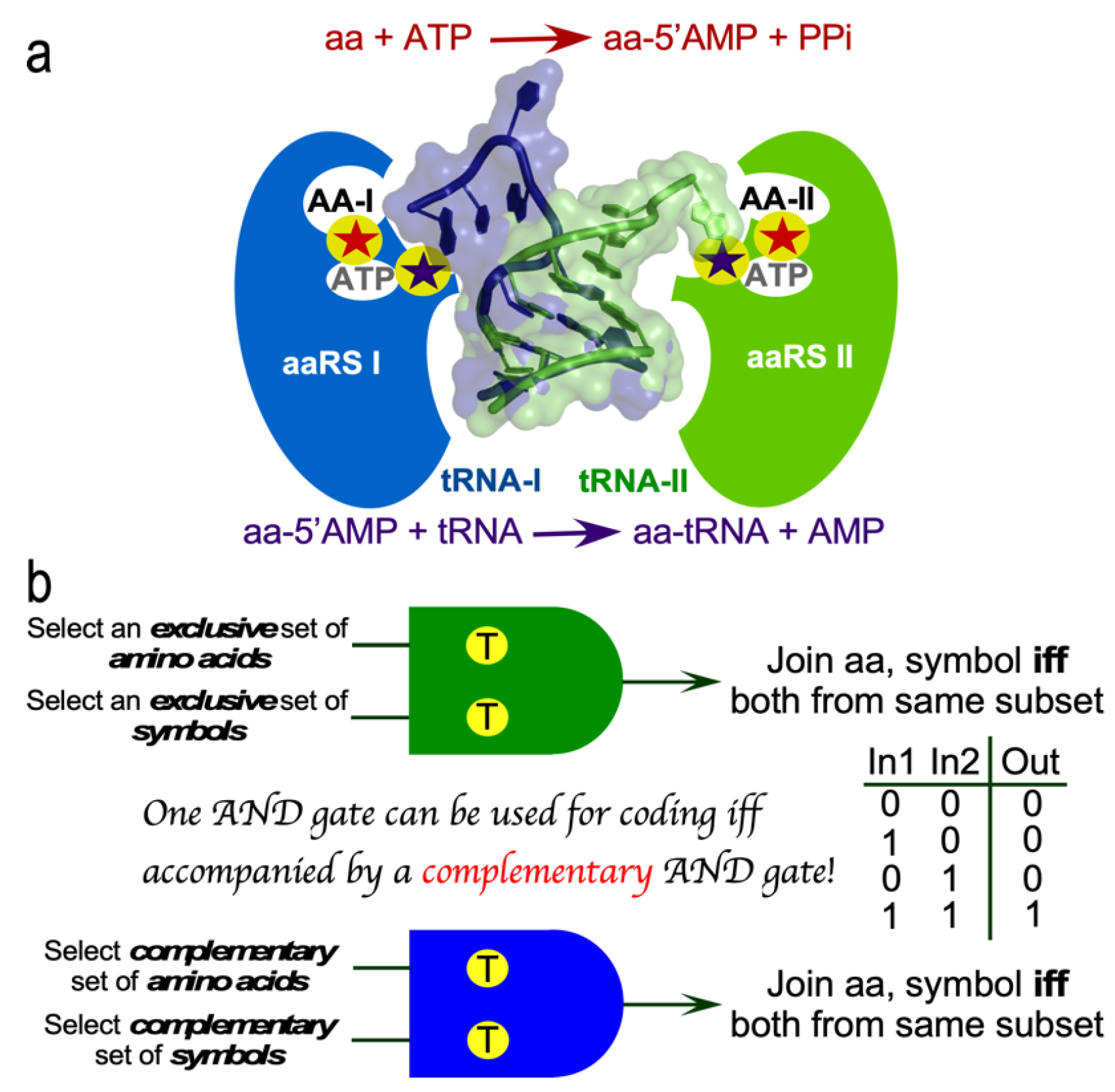

2.1. AARS/tRNA cognate pairs function as mutually exclusive molecular AND gates.

2.2. Bidirectional genetic coding projected duality into the proteome,

2.3. AARS protozymes are amino-acid activating catalysts that can be coded by a bidirectional gene.

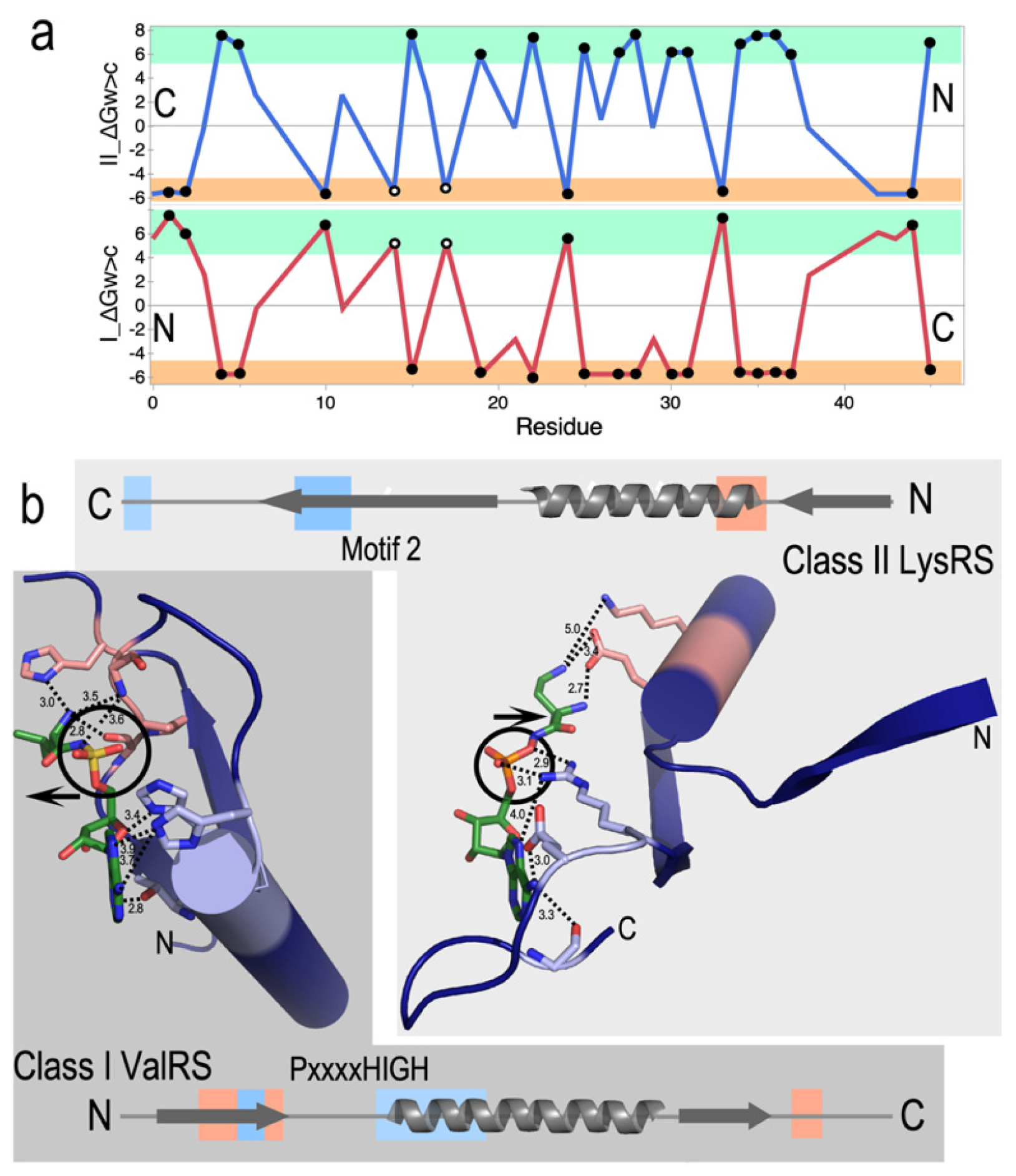

2.4. The inverse complementarity of nucleic acid base-pairing duality projects deeply into the proteome.

2.5. The projected duality creates rudimentary nanomachinery for chemical free energy transduction.

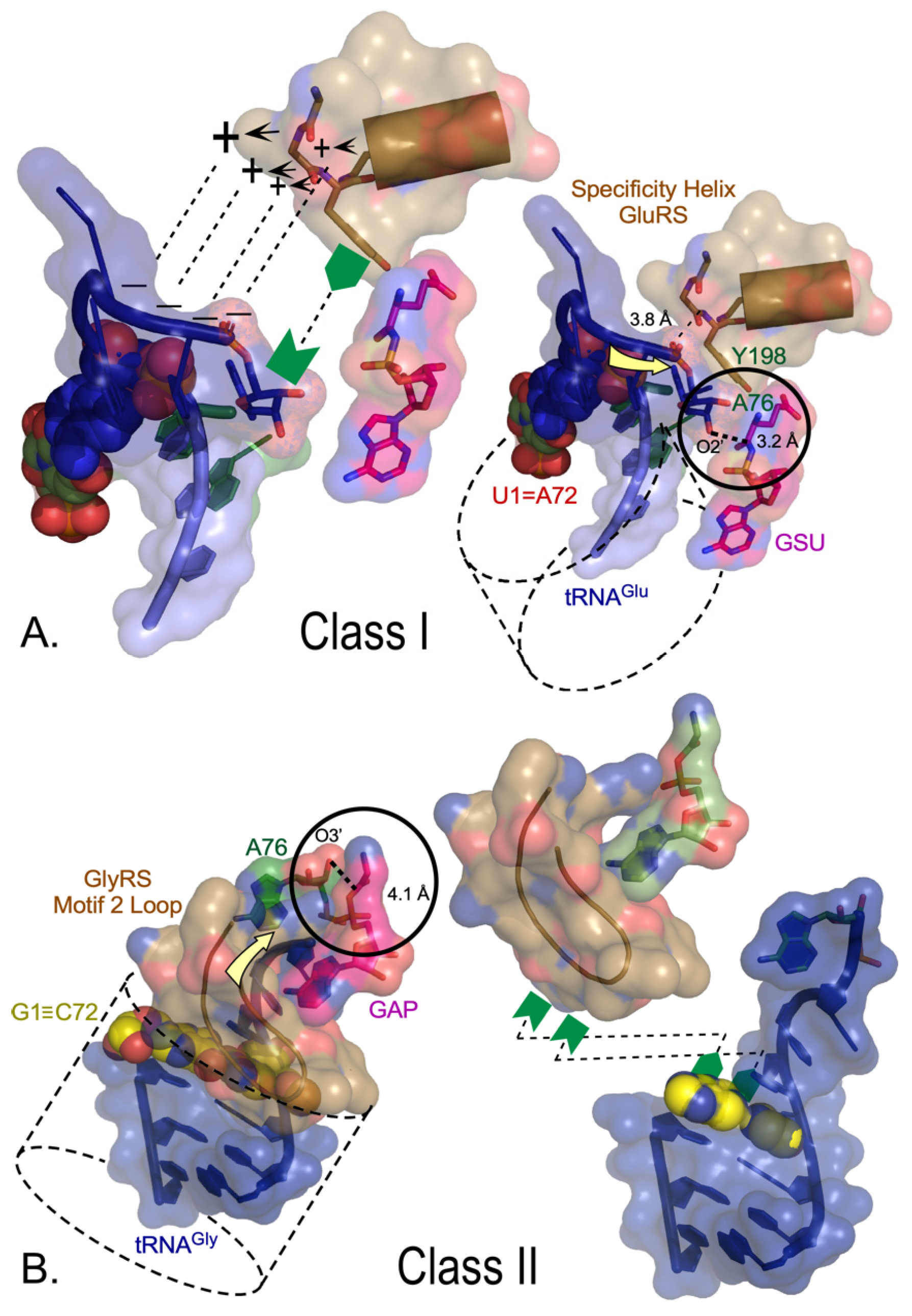

2.6. The projected duality constrains substrate recognition by AARS urzymes, dividing amino acids and tRNA acceptor stems into parallel groups.

3. Phylogenetics

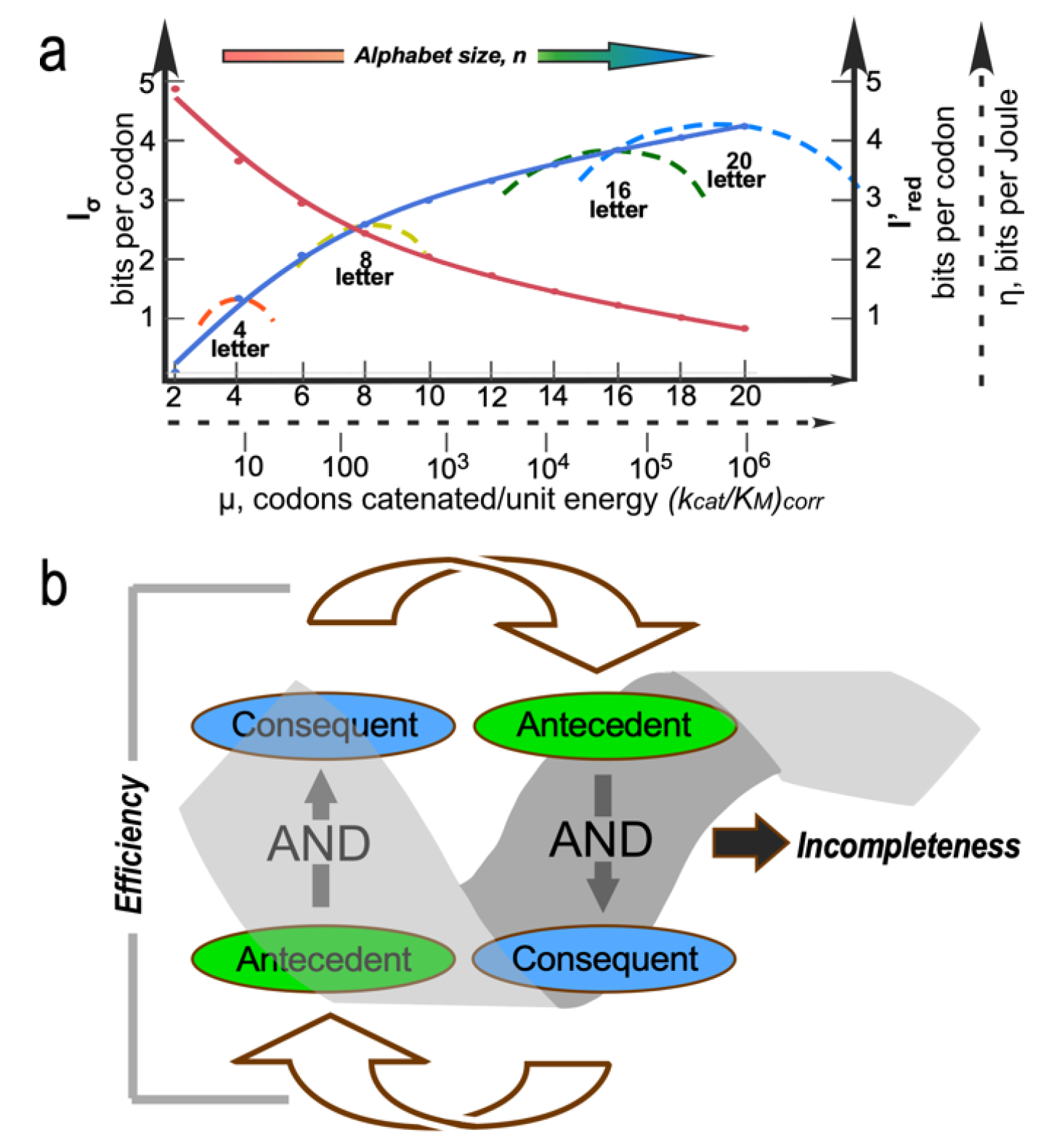

4. Constraints: impedance matching and reciprocally-coupled gating

5. Experimental Challenges

5.1. Validating the role of bidirectional coding

- How many bits (pairs of coding letters) were necessary to make bidirectional gene products sufficiently specific to achieve reflexivity? Experimental validation of reflexivity refers to designing bidirectional genes for Class I and II AARS precursors capable of experimentally discriminating between appropriate subsets of amino acids and tRNAs well enough to implement the corresponding alphabet, forming a self-consistent alphabet and set of implementing genes.

- 2.

- Is a bidirectional urzyme gene feasible? Naïve analysis of the modular patchwork of Class I and II urzymes (see Figure 4A in [27]) has not resulted in an antiparallel alignment Class I and II urzyme sequences compatible with continuous bidirectional coding of their respective three-dimensional structures; likely that analysis cannot be used to constrain protein design programs as hoped. Recently, a more suitable, alternatively threaded antiparallel alignment emerged. That alignment, also consistent with the high resolution modularity [19], may provide a template for bidirectionally coded urzymes. However, we have yet to test it.

- 3.

- What limitations of bidirectional coding forced its breakdown by providing new functionality? The CP1 insertion at the C-terminus of the protozyme interrupted all extant Class I urzymes, definitively ending bidirectional coding. Eventually, CP1 significantly enhanced amino acid specificity, but only when complemented by the anticodon-binding domain [81,82]. Simultaneous acquisition of both domains seems unlikely, so one might expect a more decisive selective advantage for so significant a modular acquisition. The LeuAC urzyme converts substantial amounts of ATP to ADP in single turnover experiments [38]. If comparable analysis of the intact catalytic domain reduced ADP production, that would suggest that CP1 initially increased the efficiency of free energy transduction. Modular deconstruction of Class II AARS should also shed new light.

- 4.

- Can AARS urzymes acylation of TΨC-minihelices confirm details of the operational code? Acylation of minihelices partially substantiated the “single-domain” model for the origin of coding [12]. Evidence that AARS urzymes catalyze acylation of full-length tRNAs [30] further strengthened that model. Recently we showed that minihelixLeu is an even better substrate for LeuAC than tRNALeu [40]. That can now enable a detailed test of the operational code.

- 5.

- Can AARS protozymes catalyze tRNA acylation? Polypeptide catalysis of aminoacylation must have appeared sometime between the ancestral bidirectional protozyme gene and the emergence of urzymes. Structures illustrated in Figure 4 are quite sophisticated, even though far simpler than contemporary AARS. As AARS protozymes likely exemplify earlier ancestral catalytic polymers, it may be notable that the motif 2 loop Class II protozymes contains much of the tRNA binding site [53] whereas the Class I tRNA binding site is formed largely by a helix present only in the urzyme. That asymmetry, suggesting that Class II AARS preceded Class I AARS, raises the profound objection that functional polypeptides must have depended minimally at least on a binary code. Ribozymes similar to the flexizyme family [103,104] might have accelerated acyl transfer from aminoacyl-5’AMP produced by Class I protozymes to proto-tRNAs, assuring provision of aminoacylated RNAs for templated protein synthesis. That would have required an ad hoc mechanism to discriminate between two types of tRNA.

5.2. Beyond genetic coding.

- (i)

- We can infer sequence/structure relationships from variations in both naturally occurring and designed sequence databases.

- (ii)

- Bioinformatic tools reducing tertiary structures to lower dimensions—conformational angles [φ, ψ]; residue transfer free energies (ΔGvapor>chx, ΔGwater>chx) [20,106,107]; TetraDA one-dimensional strings derived from Delaunay tesselation [108]; SNAPP scoring [89,90]—provide alternative multidimensional windows into structural and evolutionary determinants.

- (iii)

- The highly sensitive Malachite Green assay for phosphates generated on amino acid activation [32] affords a five-fold increase in the rate at which assays can be performed on variants of this gene.

- (iv)

- Artificial intelligence has improved both protein design [87] and structure prediction[88], creating a dynamic virtual feedback loop capable of sampling substantially larger regions of the protein sequence space expected for early nodes in AARS speciation. Pruning those sequence distributions virtually, before committing to experimental construction, expression, and testing will greatly enhance the experimental tools described above.

6. Did creating the genetic code require new physics?

Funding

Competing interest statement

Data availability

Acknowledgments

References

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Rodriguez, L.; Jimenez-Rodriguez, M.; Gonzalez-Rivera, K.; Williams, T.; Li, L.; Weinreb, V.; Chandrasekaran, S.N.; Collier, M.; Ambroggio, X.; Kuhlman, B.; et al. Functional Class I and II Amino Acid Activating Enzymes Can Be Coded by Opposite Strands of the Same Gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 19710–19725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, F.H.C. Central Dogma of Molecular Biology. Nature 1970, 227, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, F.H.C. The Origin of the Genetic Code. J. Mol. Biol. 1968, 38, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, F.H.C. Codon-Anticodon Pairing: The Wobble Hypothesis. J. Mol. Biol. 1966, 19, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.W., Jr.; Nirenberg, M.W. Degeneracy in the amino acid code. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Nucleic Acids and Protein Synthesis 1966, 119, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trupin, J.S.; Rottman, F.M.; Brimacome, R.; Leder, P.; Bernfield, M.R.; Nirenberg, M. RNA Codewords and Protein Synthesis, VI. On the Nucleotide Sequences of Degenerate Codeword Sets for Isoleucine, Tyrosine, Asparagine, and Lysine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1965; 53, 807–811. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, P.; Ofengand, E.J. An Enzymatic Mechanism for Linking Amino Acids to RNA. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1958, 44, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoagland, M.B.; E. B. Keller; Zamecnik., P.C. Enzymatic Carboxyl Activation of Amino Acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1956, 21, 345–358.

- Eriani, G.; Delarue, M.; Poch, O.; Gangloff, J.; Moras, D. Partition of tRNA synthetases into two classes based on mutually exclusive sets of sequence motifs. Nature 1990, 347, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas de Pouplana, L.; Schimmel, P. Two Classes of tRNA Synthetases Suggested by Sterically Compatible Dockings on tRNA Acceptor Stem. Cell 2001, 104, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, P.; Giegé, R.; Moras, D.; Yokoyama, S. An operational RNA code for amino acids and possible relationship to genetic code. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 8763–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, S.N.; Ohno, S. Two Types of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases Could be Originally Encoded by Complementary Strands of the Same Nucleic Acid. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 1995, 25, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wills, P.R. The Roots of Genetic Coding in Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Duality. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2021, 90, 349–373. [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr; Wills, P.R. Interdependence, Reflexivity, Fidelity, and Impedance Matching, and the Evolution of Genetic Coding. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018, 35, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wills, P.R. Autocatalysis, information, and coding. BioSystems 2001, 50, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieselt-Struwe, K.; Wills, P.R. The Emergence of Genetic Coding in Physical Systems. J. theor. Biol. 1997, 187, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, G.P.; Andam, C.P.; Alm, E.J.; Gogarten, J.P. Molecular Evolution of Aminoacyl tRNA Synthetase Proteins in the Early History of Life. Orig Life Evol Biosph 2011, 41, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Popinga, A.; Bouckaert, R.; Wills, P.R. Multidimensional Phylogenetic Metrics Identify Class I Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Evolutionary Mosaicity and Inter-modular Coupling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wolfenden, R. Acceptor-stem and anticodon bases embed amino acid chemistry into tRNA. RNA Biology 2016, 13, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriani, G.; Delarue, M.; Poch, O.; Gangloff, J.; Moras, D. Partition of tRNA Synthetases into Two Classes Based on Mutually Exclusive Sets of Sequence Motifs. Nature 1990, 347, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, S.; Berthet-Colominas, C.; Hartlein, M.; Nassar, N.; Leberman, R. A second class of synthetase structure revealed by X-ray analysis of Escherichia coli seryl-tRNA synthetase at 2.5 A. Nature 1990, 347, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, M.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Boeglin, M.; Poterszman, A.; Mitschler, A.; Podjarny, A.; Rees, B.; Thierry, J.C.; Moras, D. Class II Aminoacyl Transfer RNA Synthetases: Crystal Structure of Yeast Aspartyl-tRNA Synthetase Complexed with tRNAAsp. Science 1991, 252, 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.W., Jr. Cognition Mechanism and Evolutionary Relationships in Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Annual Review of Biochemistry 1993, 62, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusack, S. Evolutionary Implications. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 1994, 1, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.; Bouckaert, R.; Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wills, P. Enzymic recognition of amino acids drove the evolution of primordial genetic codes. Nucleic Acids Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, Y.; Li, L.; Kim, A.; Erdogan, O.; Weinreb, V.; Butterfoss, G.; Kuhlman, B.; Carter, C.W., Jr. A Minimal TrpRS Catalytic Domain Supports Sense/Antisense Ancestry of Class I and II Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Mol Cell 2007, 25, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, Y.; Kuhlman, B.; Butterfoss, G.L.; Hu, H.; Weinreb, V.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase Urzyme: a model to recapitulate molecular evolution and investigate intramolecular complementation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 38590–38601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Weinreb, V.; Francklyn, C.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Histidyl-tRNA Synthetase Urzymes: Class I and II Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Urzymes have Comparable Catalytic Activities for Cognate Amino Acid Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10387–10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Francklyn, C.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Aminoacylating Urzymes Challenge the RNA World Hypothesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26856–26863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Li, L.; Weinreb, V.; Collier, M.; Gonzales-Rivera, K.; Jimenez-Rodriguez, M.; Erdogan, O.; Chandrasekharan, S.N. The Rodin-Ohno Hypothesis That Two Enzyme Superfamilies Descended from One Ancestral Gene: An Unlikely Scenario for the Origins of Translation That Will Not Be Dismissed. Biology Direct 2014, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, K.; Suganuma, N.; Takano, H.; Sugita, Y.; Shoji, T.; Minobe, A.; Yamaki, N.; Otsuka, R.; Mutsuro-Aoki, H.; Umehara, T. , et al. Amino acid activation analysis of primitive aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases encoded by both strands of a single gene using the malachite green assay. BioSystems 2021, 208, 104481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr. Coding of Class I and II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology: Protein Reviews 2017, 18, 103–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr. What RNA World? Why a Peptide/RNA Partnership Merits Renewed Experimental Attention. Life 2015, 5, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.W., Jr. Urzymology: Experimental Access to a Key Transition in the Appearance of Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 30213–30220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, S.N.; Yardimci, G.; Erdogan, O.; Roach, J.M.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Statistical Evaluation of the Rodin-Ohno Hypothesis: Sense/Antisense Coding of Ancestral Class I and II Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 1588–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.Q.; Hobson, J.J.; Carter, C.W.J. Domain Acquisition by Class I Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Urzymes Coordinated the Catalytic Functions of HVGH and KMSKS Motifs. TBD 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, J.J.; Li, Z.; Carter, C.W., Jr. A leucyl-tRNA synthetase urzyme: authenticity of tRNA Synthetase urzyme catalytic activities and production of a non-canonical product. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, S.K.; Betts, L.; Tang, G.Q.; Douglas, J.; Wills, P.R.; Bouckeart, R.; Carter, C.W., Jr. . Genomic databases furnish a spontaneous example of a functional Class II Glycyl-tRNA synthetase urzyme. In Preparation 2024.

- Tang, G.Q.; Carter, C.W., Jr. The LeuAC Urzyme Catalyzes Aminoacylation of tRNALeu Minihelix Using Leucine and ATP. In preparation 2023.

- Zull, J.E.; Smith, S.K. Is genetic code redundancy related to retention of structural information in both DNA strands? TIBS 1990, 15, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opuu, V.; Silvert, M.; Simonson, T. Computational design of fully overlapping coding schemes for protein pairs and triplets. Scientific REPORTS 2017, 7, 15873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr. Simultaneous codon usage, the origin of the proteome, and the emergence of de-novo proteins. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2021, 68, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.W., Jr. How did the proteome emerge from pre-biotic chemistry? In Pre-Biotic Chemistry and Life's Origin, Fiore, M., Ed. The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2022; pp. 317-346.

- Mullen, G.P.; Vaughn, J.B., Jr.; Mildvan, A.S. Sequential Proton NMR Resonance Assignments, Circular Dichroism, and Structural Properties of a 50-Residue Substrate-Binding Peptide from DNA Polymerase I. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 301, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, W.-J.; Abeygunawardana, C.; Pedersen, P.L.; Mildvan, A.S. Two-Dimensional NMR, Circular Dichroism, and Fluorescence Studies of PP-50, a Synthetic ATP-Binding Peptide from the b-Subunit of Mitochondrial ATP Synthase. Biochem. 1992, 31, 7915–7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, W.-J.; Abeygunawardana, C.; Gittis, A.G.; Pedersen, P.L.; Mildvan, A.S. Solution Structure and Function in Trifluoroethanol of PP-50, an ATP-Binding Peptide from F1ATPase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992, 319, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, D.C.; Byler, D.M.; Sisu, H.; Brown, E.M.; Kuby, S., A.; Mildvan, A.S. Solution Structure of the 45-Residue MgATP-Binding Peptide of Adenylate Kinase As Examined by 2-D NMR, FTIR, and CD Spectroscopy. Biochem. 1988, 27, 3588–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, D.C.; Kuby, S., A.; Mildvan, A.S. NMR Studies of the MgATP Binding Site of Adenylate Kinase and of a 45-Residue Peptide Fragment of the Enzyme. Biochem. 1985, 24, 4680–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.; Krautwurst, S.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Leberecht, C.; Bittrich, S.; Labudde, D.; Schroeder, M. The structural basis of the genetic code: amino acid recognition by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 12647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, F.; Bittrich, S.; Salentin, S.; Leberecht, C.; Haupt, V.J.; Krautwurst, S.; Schroeder, M.; Labudde, D. Backbone Brackets and Arginine Tweezers delineate Class I and Class II aminoacyl tRNA synthetases. PLoS Comput Biol 2018, 14, e1006101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr; Wills, P.R. Class I and II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase tRNA groove discrimination created the first synthetase•tRNA cognate pairs and was therefore essential to the origin of genetic coding. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wills, P.R. Hierarchical groove discrimination by Class I and II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases reveals a palimpsest of the operational RNA code in the tRNA acceptor-stem bases. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, 9667–9683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wills, P.R. Experimental Solutions to Problems Defining the Origin of Codon-Directed Protein Synthesis. BioSystems 2019, 183, 103979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizza MughalI; Caetano-Anollés, G. MANET 3.0: Hierarchy and modularity in evolving metabolic networks. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0224201. [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Aziz, M.F.; Mughal, F.M.; Gräter, F.; Koç, I.; Caetano-Anollés, K.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Emergence of Hierarchical Modularity in Evolving Networks Uncovered by Phylogenomic Analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics 2019, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Nasir, A.; Kim, K.M.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Rooting Phylogenies and the Tree of Life While Minimizing Ad Hoc and Auxiliary Assumptions. Evolutionary Bioinformatics 2018, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koç, I.; Caetano-Anollés, G. The natural history of molecular functions inferred from an extensive phylogenomic analysis of gene ontology data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano-Anollés, D.; Caetano-Anollés, G. Piecemeal Buildup of the Genetic Code, Ribosomes, and Genomes from Primordial tRNA Building Blocks. Life 2016, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, M.F.; Caetano-Anollés, K.; Caetano-Anollés, G. The early history and emergence of molecular functions and modular scale-free network behavior. Scientific Reports | 2016, 6, 25058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Wang, M.; Caetano-Anollés, D. Structural Phylogenomics Retrodicts the Origin of the Genetic Code and Uncovers the Evolutionary Impact of Protein Flexibility. Plos One 2013, 8, e72225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Novozhilov, A.S. Origin and Evolution of the Universal Genetic Code. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2017, 51, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, P.; Luthey-Schulten, Z. On the Evolution of Structure in Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 550–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohn, M.J.; Park, H.-S.; O’Donoghue, P.; Schnitzbauer, M.; Söll, D. Emergence of the universal genetic code imprinted in an RNA record. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18095–18100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Evolution of Life on Earth: tRNA, Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases and the Genetic Code. Life 2020, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibba, M.; Soll, D. Aminoacyl-tRNAs: setting the limits of the genetic code. Genes and Development 2004, 18, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woese, C.R.; Olsen, G.J.; Ibba, M.; Soll, D. Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases, the Genetic Code, and the Evolutionary Process. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 202–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caetano-Anollés, G.; Sun, F.-J. The natural history of transfer RNA and its interactions with the ribosome. Fronteirs in Genetics 2014, 5, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.R.; Lam, S.K. Self-organization, Natural Selection,and Evolution: Cellular Hardware and Genetic Software. BioScience 2010, 60, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füchslin, R.M.; McCaskill, J.S. Evolutionary self-organization of cell-free genetic coding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001, 98, 9185–9190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigen, M. Selforganization of Matter and the Evolution of Biological Macromolecules. Naturwissenschaften 1971, 58, 465–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.A. New standards for collecting and fitting steady state kinetic data. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, A.; Howorth, D.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E.; Hubbard, T.J.P.; Chothia, C.; Murzin, A.G. Data growth and its impact on the SCOP database: new developments. Nucl. Acids Res. 2008, 36, D419–D425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Ding, C.; Holbrook, S.R. Comparative mapping of sequence-based and structure-based protein domains. BMC Bioinformatics 2005, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson-Smith, V.; Kolaczkowski, B.; Thornton, J.W. Robustness of Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction to Phylogenetic Uncertainty. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 1988–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberles, D.A. Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, S.A.; Sassi, S.O.; Gaucher, E.A. Molecular Paleoscience: Systems Biology from the Past. Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology 2007, 75, 9–140. [Google Scholar]

- Stackhouse, J.; Presnell, S.R.; McGeehan, G.M.; Nambiar, K.P.; Benner, S.A. The Ribonuclease from an extinct bovid ruminant. FEBS Letters 1990, 262, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praetorius-Ibba, M.; Stange-Thomann, N.; Kitabatake, M.; Ali, K.; Söll, I.; Carter, C.W., Jr.; Ibba, M.; Söll, D. Ancient Adaptation of the Active Site of Tryptophanyl-tRNA Synthetase for Tryptophan Binding. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 13136–13143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, T.; Uter, N.; Nissan, T.A.; Perona, J.J. Amino Acid Discrimination by a class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase specified by negative determinants. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 328, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Full Implementation of the Genetic Code by Tryptophanyl-tRNA Synthetase Requires Intermodular Coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 34736–34745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, V.; Li, L.; Chandrasekaran, S.N.; Koehl, P.; Delarue, M.; Carter, C.W., Jr Enhanced Amino Acid Selection in Fully-Evolved Tryptophanyl-tRNA Synthetase, Relative to its Urzyme, Requires Domain Movement Sensed by the D1 Switch, a Remote, Dynamic Packing Motif J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 4367-4376. [CrossRef]

- Perona, J.J.; Gruic-Sovulj, I. Synthetic and Editing Mechanisms of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Topics in Current Chemistry 2014, 344, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, J.; Holland, B.R.; Sumner, J.G.; Nieselt, K.; Wills, P.R. The Ancient Operational Code is Embedded in the Amino Acid Substitution Matrix and aaRS Phylogenies. J. Mol. Evol. 2019, 88, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.C.; Minh, B.Q.; McShea, H.; Masel, J.; James, J.E.; Vinh, L.S. Dang, C.C.; Minh, B.Q.; McShea, H.; Masel, J.; James, J.E.; Vinh, L.S.; Robert Lanfear. nQMaker: Estimating Time Nonreversible Amino Acid Substitution Models. Syst. Biol. 2022, 71, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Vaughan, T.G.; Sottani, J.B.; Duchene, S.; Fourment, M.; Gavryushkina, A.; Heled, J.; Jones, G.; Kühnert, D.; De Maio, N., et al. BEAST 2.5: An Advanced Software Platform for Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis. PLoS Comput Biol 2019, 15, e1006650.

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; Wicky, B.I.M.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R.J.; Bethel, N., et al. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, , 49–56 (2022).

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropsha, A.; Carter, C.W.J.; Cammer, S.; Vaisman, I.I. Simplicial Neighborhood Analysis of Protein Packing (SNAPP): A Computational Geometry Approach to Studying Proteins. Methods in Enzymology 2003, 374, 509–544. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; LeFebvre, B.; Cammer, S.A.; Tropsha, A.; Edgell, M.H. Four-body potentials reveal protein-specific correlations to stability changes caused by hydrophobic core mutations. Journal of Molecular Biology 2001, 311, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zou, Q. Prediction of protein solubility based on sequence physicochemical patterns and distributed representation information with DeepSoluE. BMC Biology 2023, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, J.; Carter, C.W., Jr; Peter, R. Wills. HetMM: A Michaelis-Menten model for non-homogeneous enzyme mixtures. BioRxiv, 1101. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankov, D.N.; Finkelstein, A.V. Solution of Levinthal’s Paradox and a Physical Theory of Protein Folding Times. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dill, K.; Chan, H.S. From Levinthal to pathways to funnels. Nat. Str. Biol. 1997, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinthal, C. ARE THERE PATHWAYS FOR PROTEIN FOLDING ? Journal de Chimie Physique 1968, 65, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattenet, A.L.; Davidson, I.; Nijssen, S.; Schaus, P. Constraint Programming for an Efficient and Flexible Block Modeling Solver. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2020, 34, 13685–13688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, P.R.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Impedance matching and the choice between alternative pathways for the origin of genetic coding. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Andrés, L. Impedance Matching. Availabe online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/188313 (accessed on.

- Hofstadter, D.R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid; Basic Books, Inc: New York, 1979; p. 777. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wills, P.R. Reciprocally-coupled Gating: Strange Loops in Bioenergetics, Genetics, and Catalysis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.W., Jr. Escapement mechanisms: efficient free energy transduction by reciprocally-coupled gating. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2019, 88, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, Y.; Li, L.; Kim, A.; Weinreb, V.; Butterfoss, G.; Kuhlman, B.; Carter, C.W., Jr. A Minimal TrpRS Catalytic Domain Supports Sense/Antisense Ancestry of Class I and II Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases. Mol. Cell 2007, 25, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, N.; Yamagishi, Y.; Murakami, H.; Suga, H. A flexizyme that selectively charges amino acids activated by a water-friendly leaving group. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 3892–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Murakami, H.; Suga, H.; Ferre-D’Amare, A.R. Structural basis of specific tRNA aminoacylation by a small in vitro selected ribozyme. Nature 2008, 454, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buehner, M.; Ford, G.C.; Moras, D.; Olsen, K.W.; Rossmann, M.G. D-Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase: Three Dimensional Structure and Evolutionary Significance. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1973, 70, 3052–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Wolfenden, R. tRNA Acceptor-Stem and Anticodon Bases Form Independent Codes Related to Protein Folding. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112 7489-7494. [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, R.; Lewis, C.A.; Yuan, Y.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Temperature dependence of amino acid hydrophobicities. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7484–7488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, J.M.; Sharma, S.; Kapustina, M.; Carter, C.W., Jr. Structure alignment via Delaunay tetrahedralization. PROTEINS: Structure, Function and Bioinformatics 2005, 60, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. What every physicist should know about String Theory. Physics Today 2015, November, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).