Submitted:

12 January 2024

Posted:

12 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

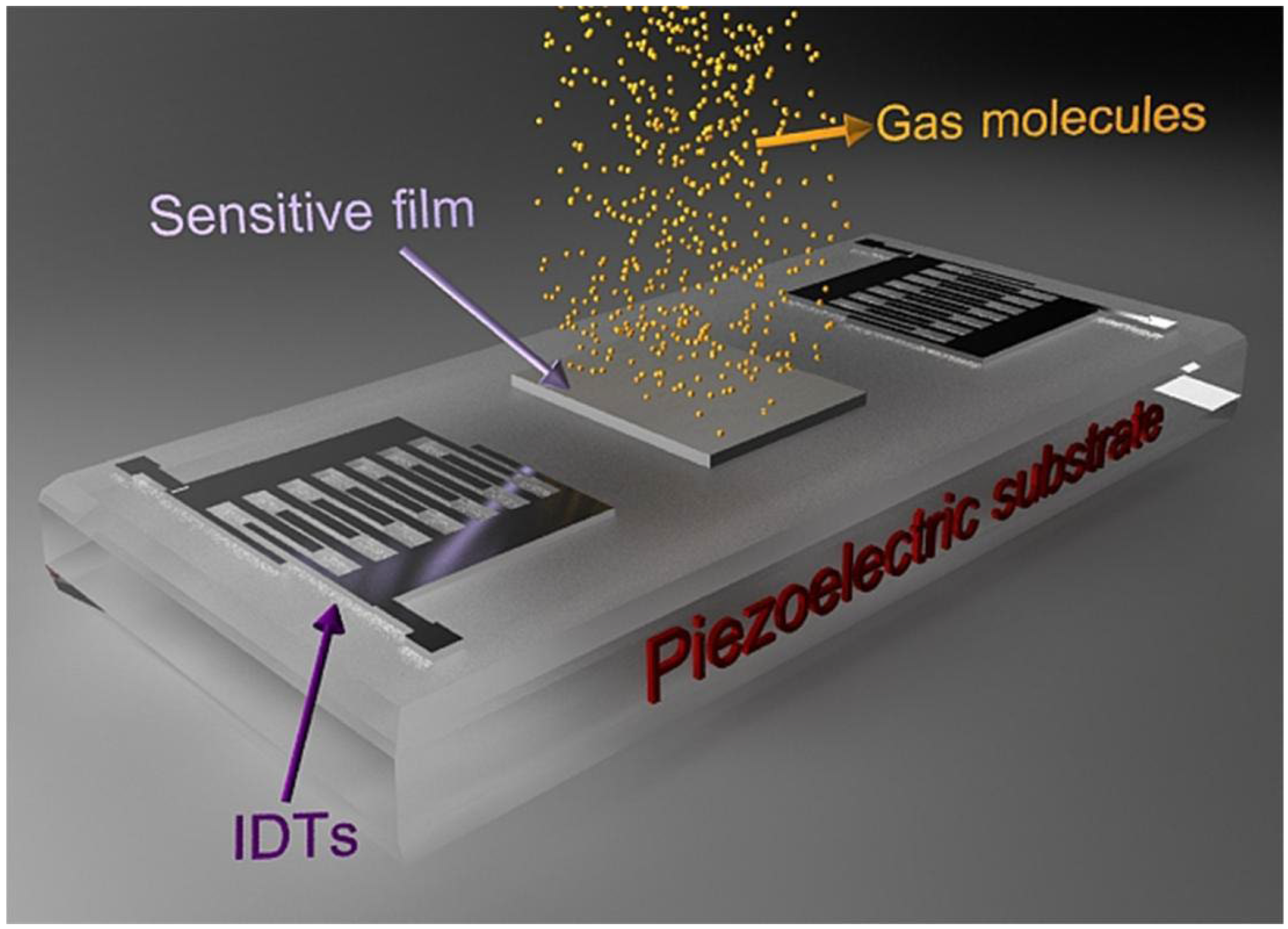

1.1. The Fundamental Concepts of SAW Sensors

1.2. Sulphur-Containing Hazardous Gas Species

1.2.1. Sulfur-Containing Chemical Agents

1.2.2. Sulfur-Containing Harmful Gas

2. Sensitive Functional Materials of Sulfur-Containing Agents and Their Simulants

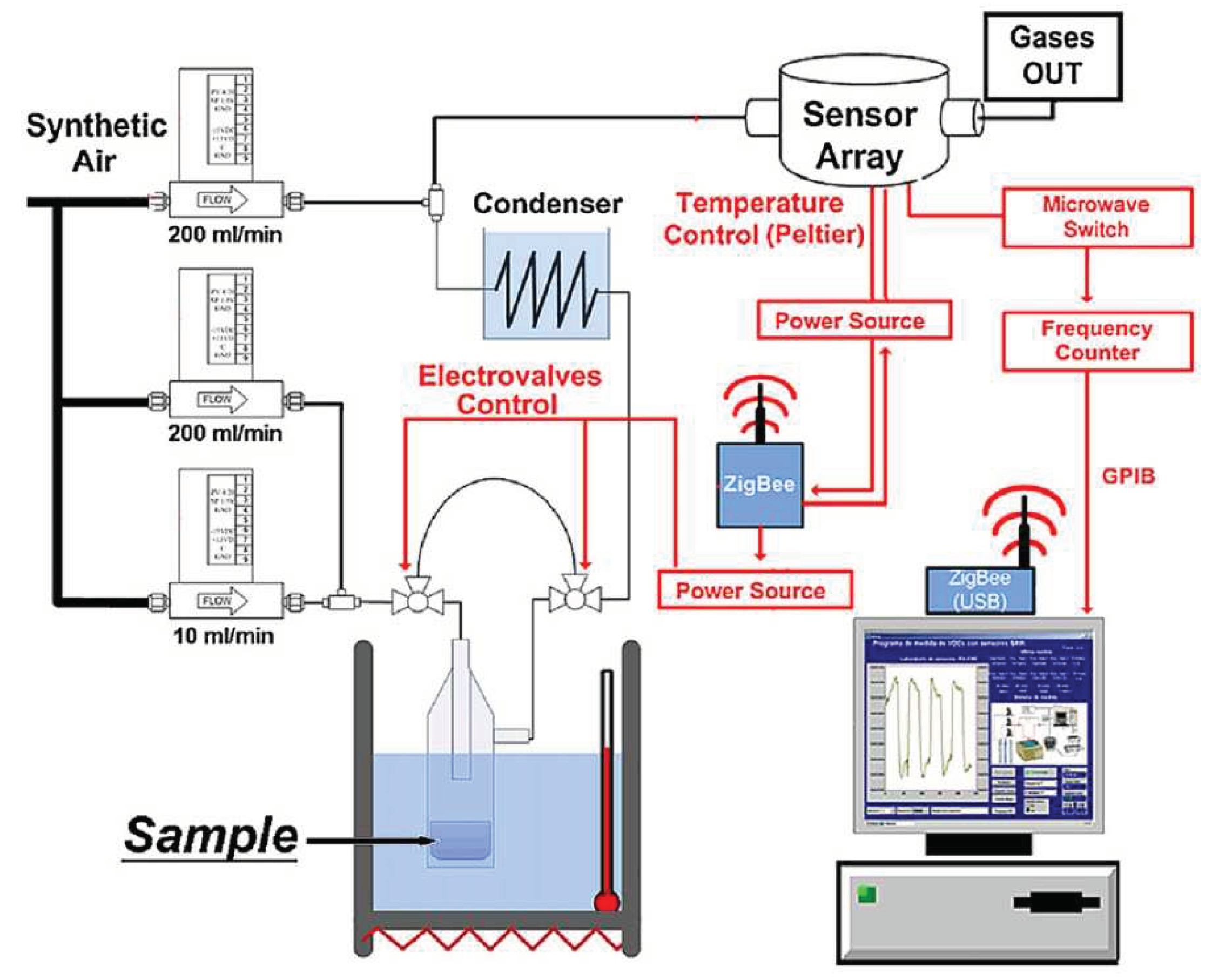

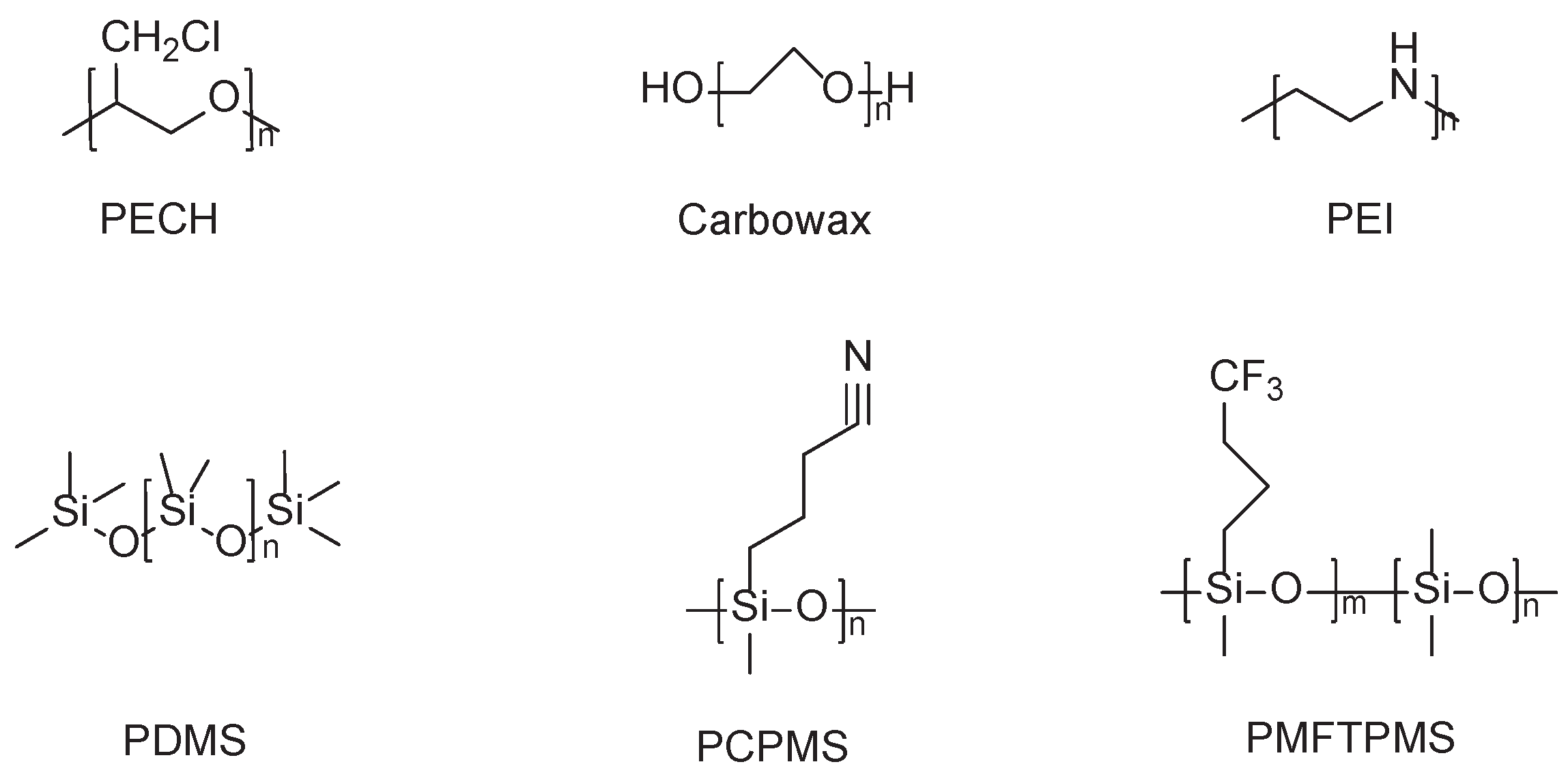

2.1. Polymer

2.2. Organic Small Molecule

2.3. Other kinds of sensitive materials

3. Sensitive Functional Materials of Sulfur-Containing Harmful Gases

3.1. Sensitive Functional Materials for SO2 Detection

3.2. Sensitive Functional Materials for H2S Detection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rayleigh, L. On waves propagated along the plane surface of an elastic solid. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 1885; s1-17(1), 4-11. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.M.; Voltmer, F.W. Direct piezoelectric coupling to surface elastic waves. Applied Physics Letters 1965, 7(12), 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohltjen, H.; Dessy, R. Surface acoustic wave probe for chemical analysis. I. Introduction and instrument description Analytical Chemistry 1979, 51(9), 1458–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Wohltjen, H.; Dessy, R. Surface acoustic wave probes for chemical analysis. II. Gas chromatography detector. Analytical Chemistry 1979, 51(9), 1465–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohltjen, H.; Dessy, R. Surface acoustic wave probes for chemical analysis. III. Thermomechanical polymer analyzer. Analytical Chemistry 1979, 51(9), 1470–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cao, B.; et al. Effects of temperature and humidity on the performance of a PECH polymer coated SAW sensor. RSC Adv. 2020, 10(31), 18099–18106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.G.; Alder, J.F. Surface acoustic wave sensors for atmospheric gas monitoring. A review. Analyst 1989, 114(9), 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.Q.; Zhu, W.Z. Surface acoustic wave sensor and its application. Sensor World. 1996, 2(8), 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.Q.; Xia, G.Q. 158MHz Surface Acoustic Wave Fixed-Delay Line on GaAs. Chinese Journal of Semiconductors. 2000, 021(001), 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, D.; Banerjee, S. Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW) Sensors: Physics, Materials, and Applications. Sensors. 2022, 22(3), 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.B.; Xiang, J.J.; Feng, Q.H.; et al. Binary Channel SAW Mustard Gas Sensor Based on PdPc0.3PANI0.7 Hybrid Sensitive Film. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Harbin, China, 8–12 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Cai, H.; et al. Surface acoustic wave devices for sensor applications. Journal of Semiconductors. 2016, 37(2), 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhu, C.; Ju, Y.; et al. A novel dual track SAW gas sensor using three-IDT and two-MSC. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2009, 9(12), 2010–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Z.; Zuo, B.L.; Ma, J.Y.; et al. Detecting Mustard Gas Using High Q-value SAW Resonator Gas Sensors; In Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Piezoelectricity, Acoustic Waves and Device Applications, Nanjing, China 05-08 December 2008.

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, J.; Tang, H.; et al. Ultrahigh-frequency surface acoustic wave sensors with giant mass-loading effects on electrodes. ACS Sensors. 2020, 5(6), 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Sheikhi, M.H. Surface acoustic wave based H2S gas sensors incorporating sensitive layers of single wall carbon nanotubes decorated with Cu nanoparticles. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2014, 198, 134-141.

- Falconer, R.S. A versatile SAW-based sensor system for investigating gas-sensitive coatings. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 1995; 24, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

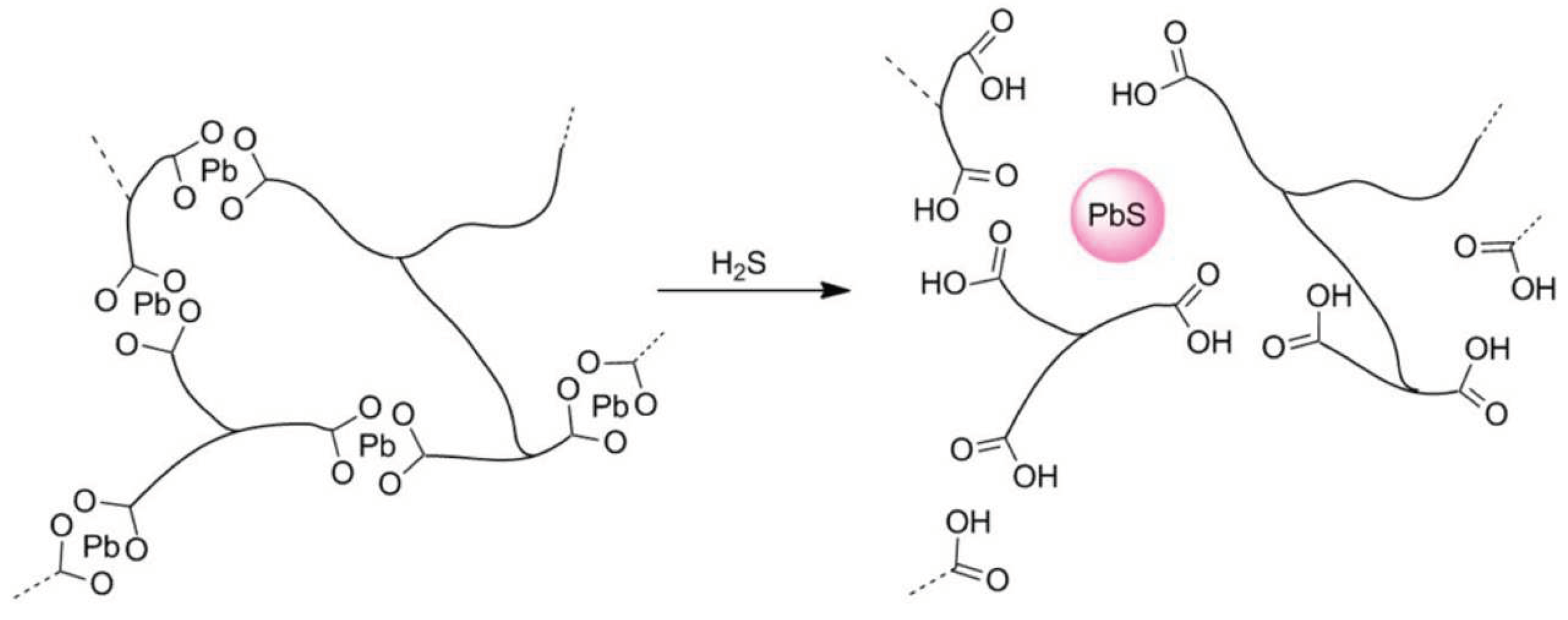

- Li, D.; Zu, X.; Ao, D.; et al. High humidity enhanced surface acoustic wave (SAW) H2S sensors based on sol–gel CuO films. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2019, 294, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Xue, M.J.; Zhang, Q.L.; et al. Prefluorescent probe capable of generating active sensing species in situ for detections of sulfur mustard and its simulant. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 371, 132555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, E.; Jin, A.; Noonan, K.; et al. Decontamination issues for chemical and biological warfare agents: How clean is clean enough? International Journal of Environmental Health Research. 2010, 11(2), 128–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Rana, H. Selective and sensitive chromogenic and fluorogenic detection of sulfur mustard in organic, aqueous and gaseous medium. RSC Advances. 2015, 5(112), 91946–91950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Hefazi, M. The pharmacology, toxicology, and medical treatment of sulphur mustard poisoning Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 2005, 19(3), 297-315.

- Wattana, M.; Bey, T. Mustard gas or sulfur mustard: an old chemical agent as a new terrorist threat. Prehosp Disaster Med 2009, 24, 19–29; discussion 30-31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, S.; Chauhan, S.; D’cruz, R.; et al. Chemical warfare agents. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2008, 26(2), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matatagui, D.; Martí, J.; Fernández, M.J.; et al. Chemical warfare agents simulants detection with an optimized SAW sensor array. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2011, 154, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

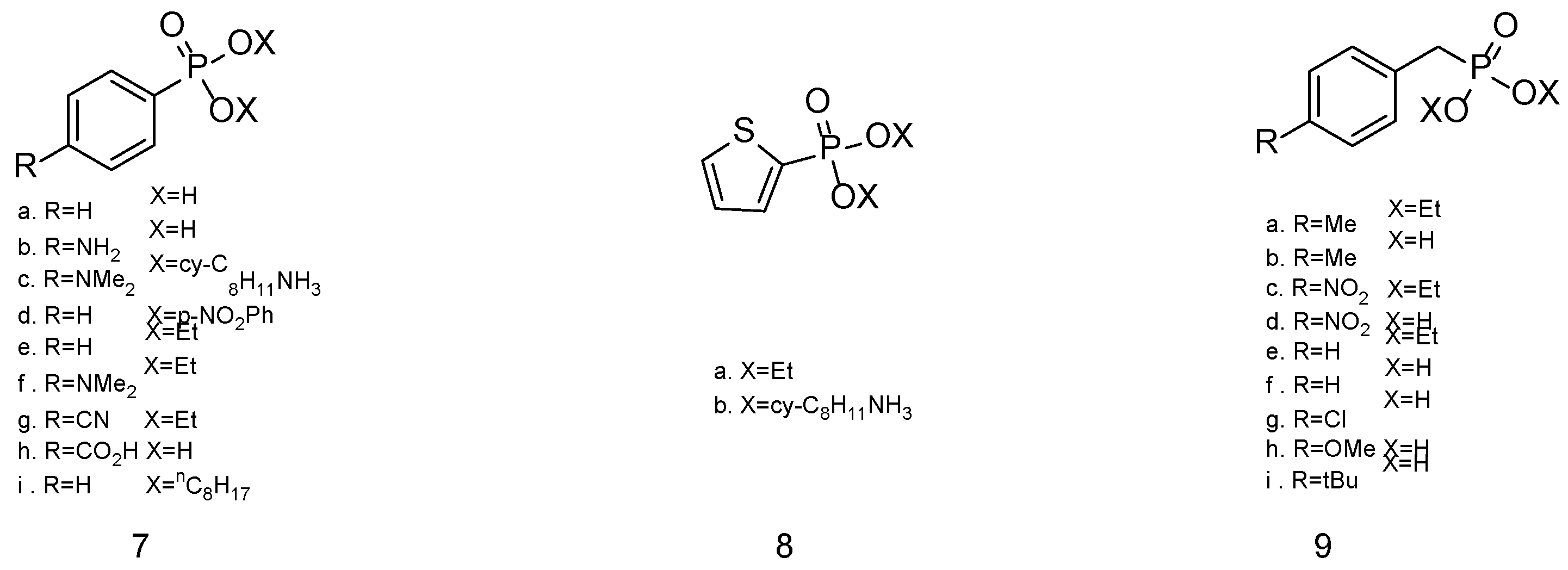

- Katritzky, A.R.; Savage, G.P.; Offerman, R.J.; et al. Synthesis of new microsensor coatings and their response to vapors-III Arylphosphonic acids, salts and esters. Talanta. 1990, 37(9), 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, V.B.; Singh, H.; Nimal, A.T.; et al. Oxide thin films (ZnO, TeO2, SnO2, and TiO2) based surface acoustic wave (SAW) E-nose for the detection of chemical warfare agents. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2013, 178, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhomick, P.C.; Rao, K.S. Sources And Effects of Hydrogen Sulfide. Journal of Applicable Chemistry. 2014, 3(3), 914–918. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, C.S.; Weir, A.; Rumbeiha, W.K. A comprehensive review of treatments for hydrogen sulfide poisoning: past, present, and future. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods. 2022, 33(3), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.M.; Yang, Y.W. Research progress on fluorescence detection technology of atmospheric pollutant sulfur dioxide Shanghai Chemical Industry. 2019, 44(04), 39-43.

- Khan, M.; Rao, M.; Li, Q. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Sensors for Detecting Toxic Gases: NO2, SO2 and H2S. Sensors 2019, 19(4), 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grate, J.W.; Rose-pehrsson, S.L.; Venezky, D.L.; et al. Smart sensor system for trace organophosphorus and organosulfur vapor detection employing a temperature-controlled array of surface acoustic wave sensors, automated sample preconcentration, and pattern recognition. Analytical Chemistry. 1993, 65(14), 1868–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.W.; Yu, J.H.; Pan, Y.; et al. Surface acoustic wave sensor detection of mustard gas with Poly(epichlorohydrin) coatings Chemical Sensors 2005, (01); 57-60.

- Liu, W.W.; Yu, J.H.; Pan, Y.; et al. The study of response character in the detection of HD by SAW-PECH sensor. Chemical Sensors. 2005, (04), 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.W.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, J.J.; et al. The adsorption study of SAW-PECH sensor to organosulfur agents. Chemical Sensors. 2006, (03), 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.W.; Yu, J.H.; Pan, Y.; et al. Studying on the and Application of SAW Technology in Detection of Organosulfur Chemical Warfare Agents. Piezoelectrics & Acoustooptics 2006, 01, 14–16+20. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Z.; Ma, J.Y.; Zuo, B.L.; et al. A Novel Toxic Gases Detection System Based on SAW Resonator Array and Probabilistic Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Electronic Measurement and Instruments, Xian, China, 16-18 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Matatagui, D.; Martí, J.; Fernánfez, M.J.; et al. Optimized design of a SAW sensor array for chemical warfare agents simulants detection. Procedia Chemistry. 2009, 1(1), 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matatagui, D.; Fontecha, J.; Fernandez, M.J.; et al. Array of Love-wave sensors based on quartz/Novolac to detect CWA simulants. Talanta. 2011, 85(3), 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matatagui, D.; Fernández, M.J.; Fontecha, J.; et al. Love-wave sensor array to detect, discriminate and classify chemical warfare agent simulants. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2012, 175, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; et al. Advances in Polymer-Coated Surface Acoustic Wave Gas Sensor; In Proceedings of the 2011 16th International Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference, 5-9 June 2011.

- Qi, J.; Wen, Y.M.; Li, P. Study on the detection of blister agent mustard by surface acoustic wave technology. Journal of Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications(Natural Science Edition) 2017, 29, 494–499. [Google Scholar]

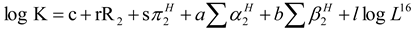

- Pan, Y.; Mu, N.; Liu, B.; et al. A novel surface acoustic wave sensor array based on wireless communication network. Sensors (Basel). 2018, 18(9), 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, G.; et al. Development of a SAW poly(epichlorohydrin) gas sensor for detection of harmful chemicals. Anal Methods. 2022, 14(16), 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcgill, R.A.; Nguyen, V.K.; Chung, R.; et al. The "NRL-SAWRHINO": a nose for toxic gases. Sens Actuator B-Chem 2000, 65, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matatagui, D.; Fernandez, M.J.; Fontecha, J.; et al. Characterization of an array of Love-wave gas sensors developed using electrospinning technique to deposit nanofibers as sensitive layers. Talanta. 2014, 120, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

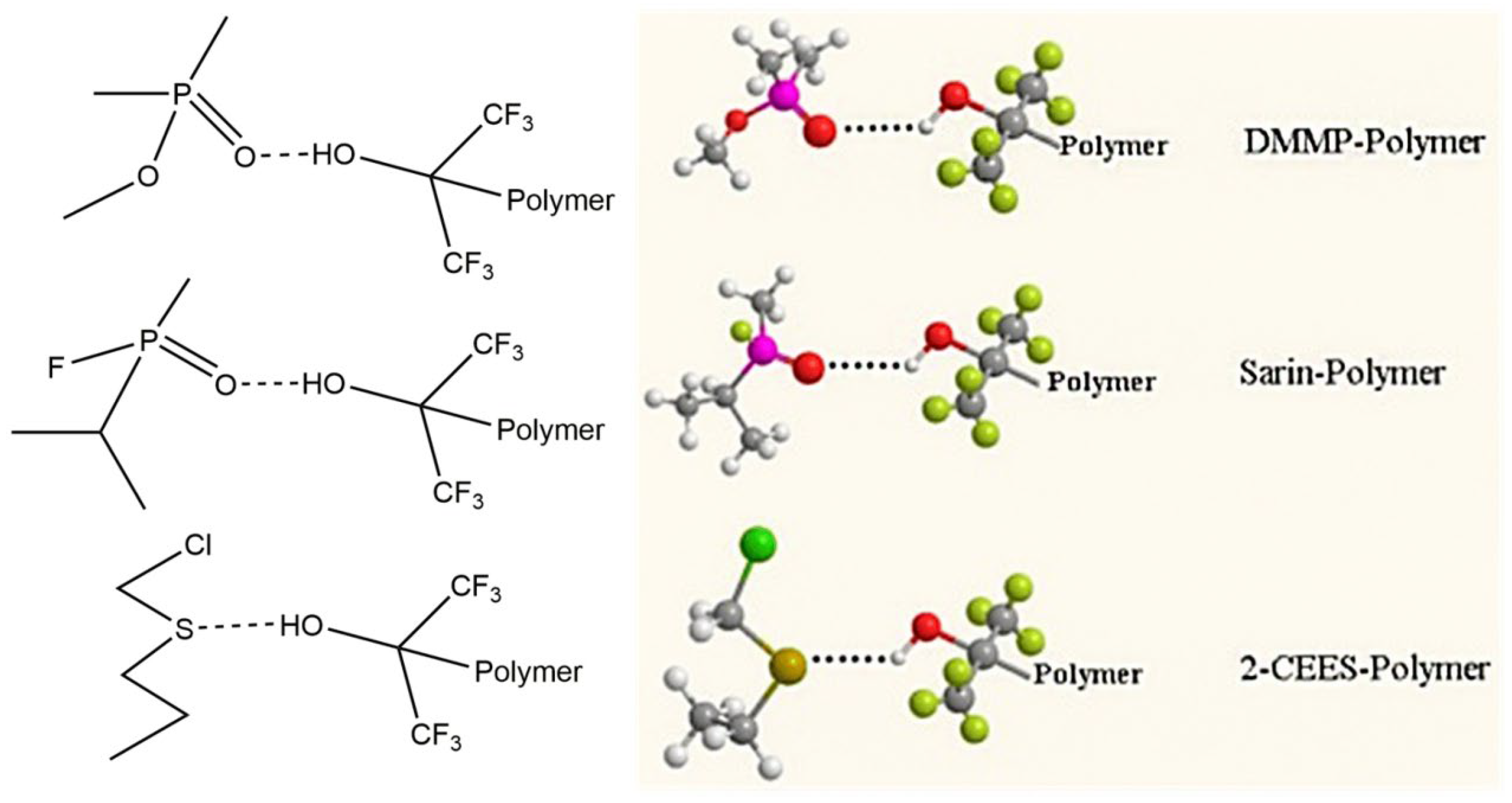

- Long, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; et al. The different sensitive behaviors of a hydrogen-bond acidic polymer-coated SAW sensor for chemical warfare agents and their simulants. Sensors (Basel). 2015, 15(8), 18302–18314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

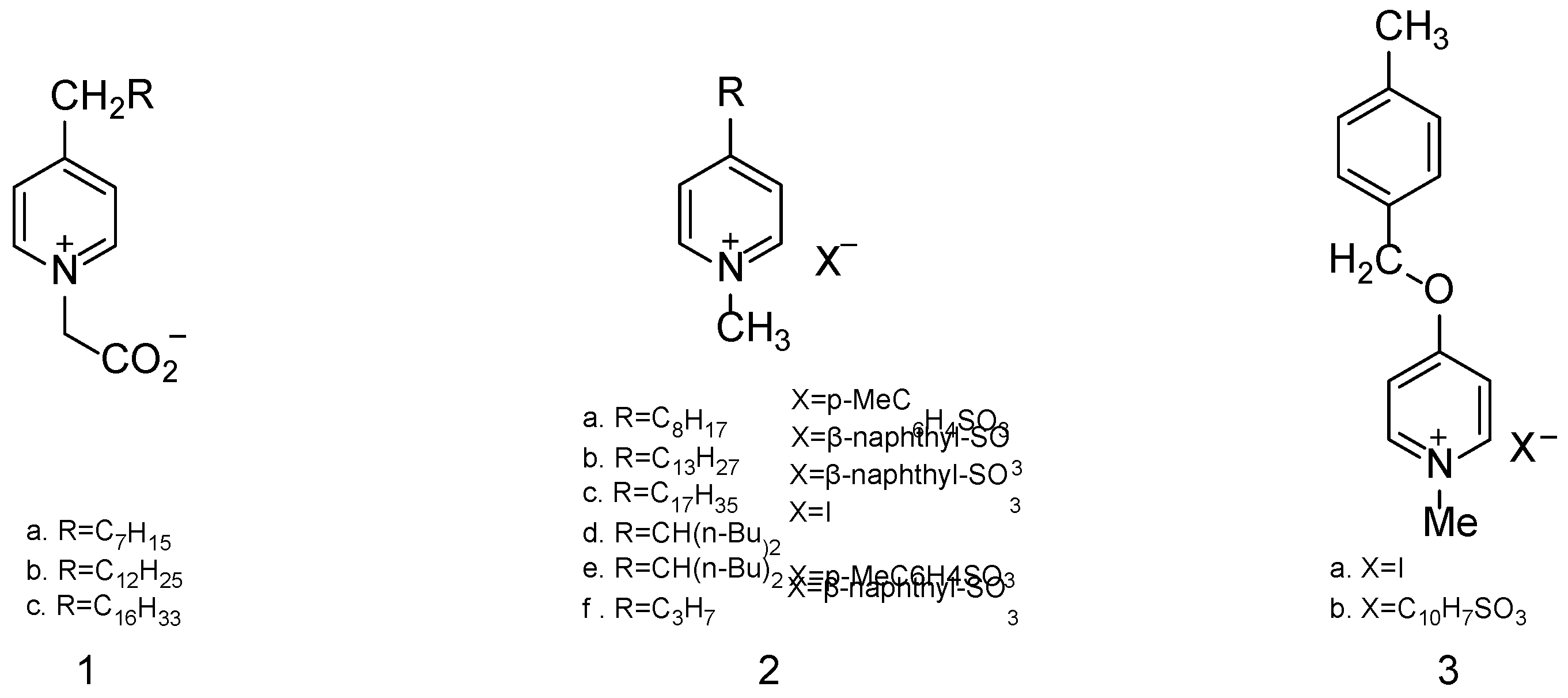

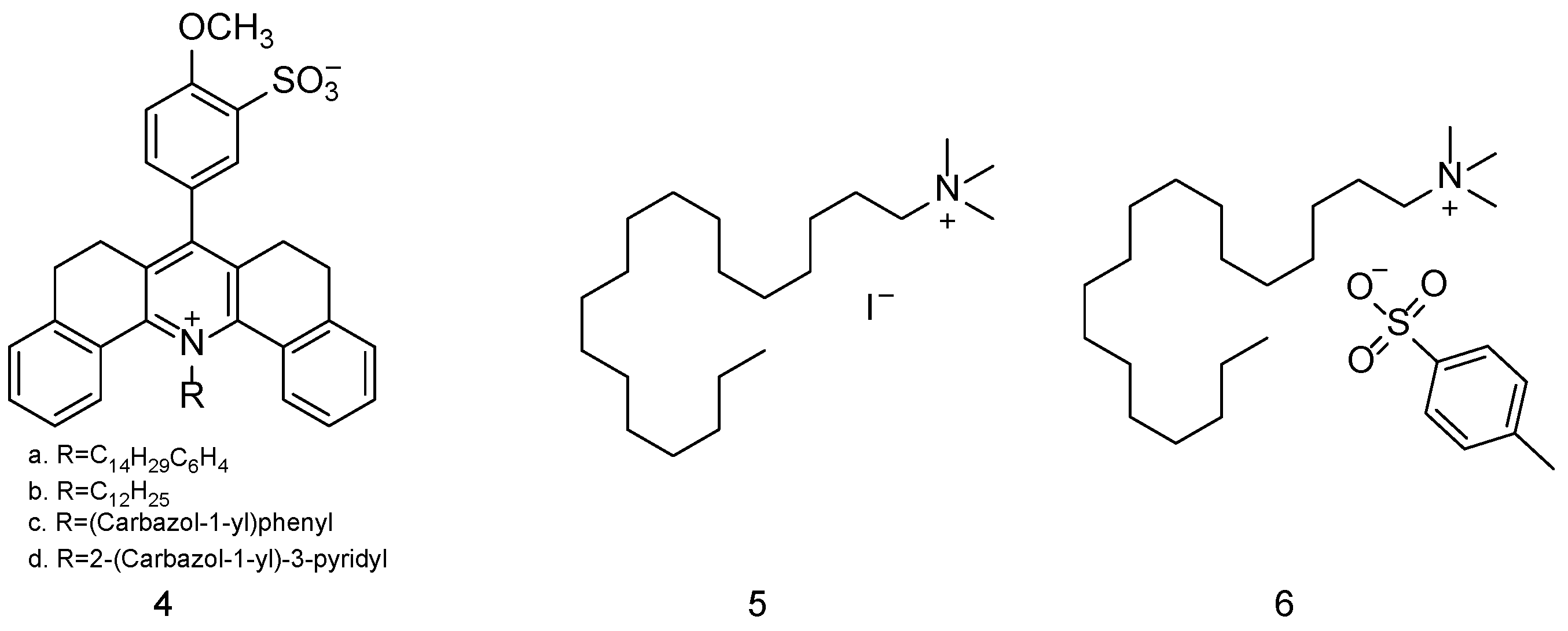

- Katritzky, A.R.; Offerman, R.J.; Wang, Z. Utilization of pyridinium salts as microsensor coatings. Langmuir. 1989, 5(4), 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katritzky, A.R.; Offerman, R.J.; Aurrecoechea, J.M.; et al. Synthesis and response of new microsensor coatings-II Acridinium betaines and anionic surfactants. Talanta. 1990, 37(9), 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

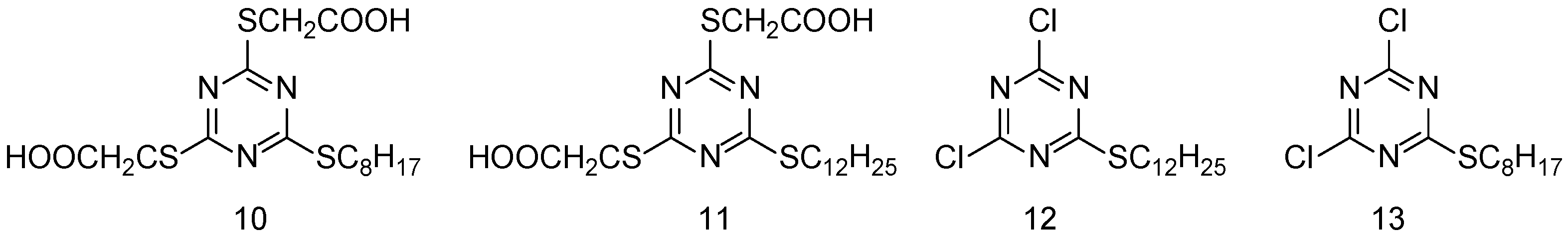

- Katritzky, A.R.; Lam, J.N.; Faid-Allah, H.M. Synthesis of new microsensor coatings and their response to test vapors 2,4,6-trisubstituted-1,3,5-triazine derivatives. Talanta. 1991, 38(5), 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayago, I.; Matatagui, D.; Fernandez, M.J.; et al. Graphene oxide as sensitive layer in Love-wave surface acoustic wave sensors for the detection of chemical warfare agent simulants. Talanta. 2016, 148, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahim, F.; Mainuddin, M.; Mittal, U.; et al. Novel SAW CWA detector using temperature programmed desorption. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2021, 21(5), 5914–5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Nimal, A.T.; Mittal, U.; et al. Effect of carrier gas on sensitivity of surface acoustic wave detector. Ieee Sensors Journal 2022, 22(9), 8394–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidl, A; Hartinger, R.; Roth, M.; et al. A new SO2 sensor system with SAW and IDC elements. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 1996, 34, 339–342. [CrossRef]

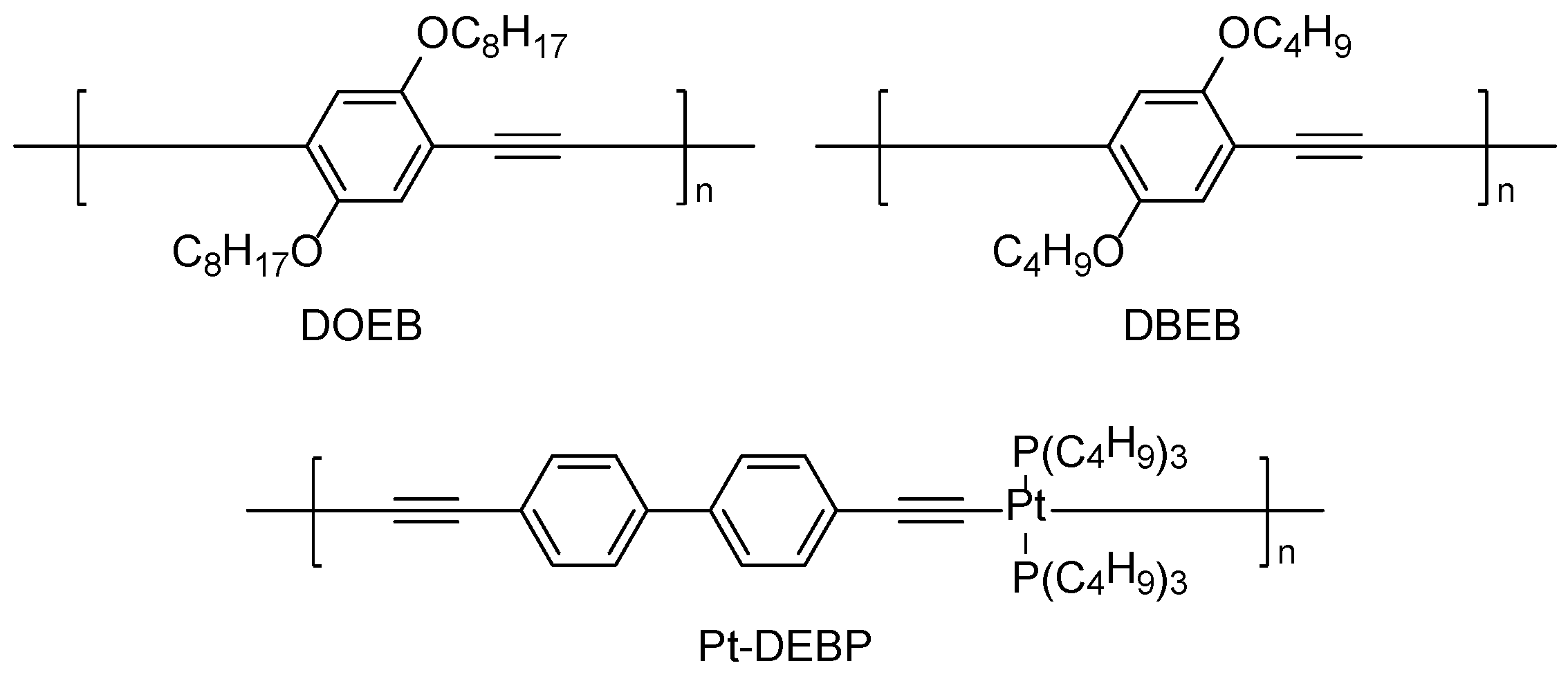

- Penza, M.; Cassano, G.; Sergi, A.; et al. SAW chemical sensing using poly-ynes and organometallic polymer films. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2001, 81, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubik, W.P.; Urbanczyk, M.; Maciak, E.; et al. Polyaniline thin films as a toxic gas sensors in SAW system*. Journal de Physique IV (Proceedings). 2005, 129, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.B.; Zhu, C.C.; Ju, Y.F.; et al. Experimental Study on SAW SO2 Sensor Based on Carbon Nanotube-polyanilin Films Piezoelectrics & Acoustooptics. 2009, 31(02), 157-160.

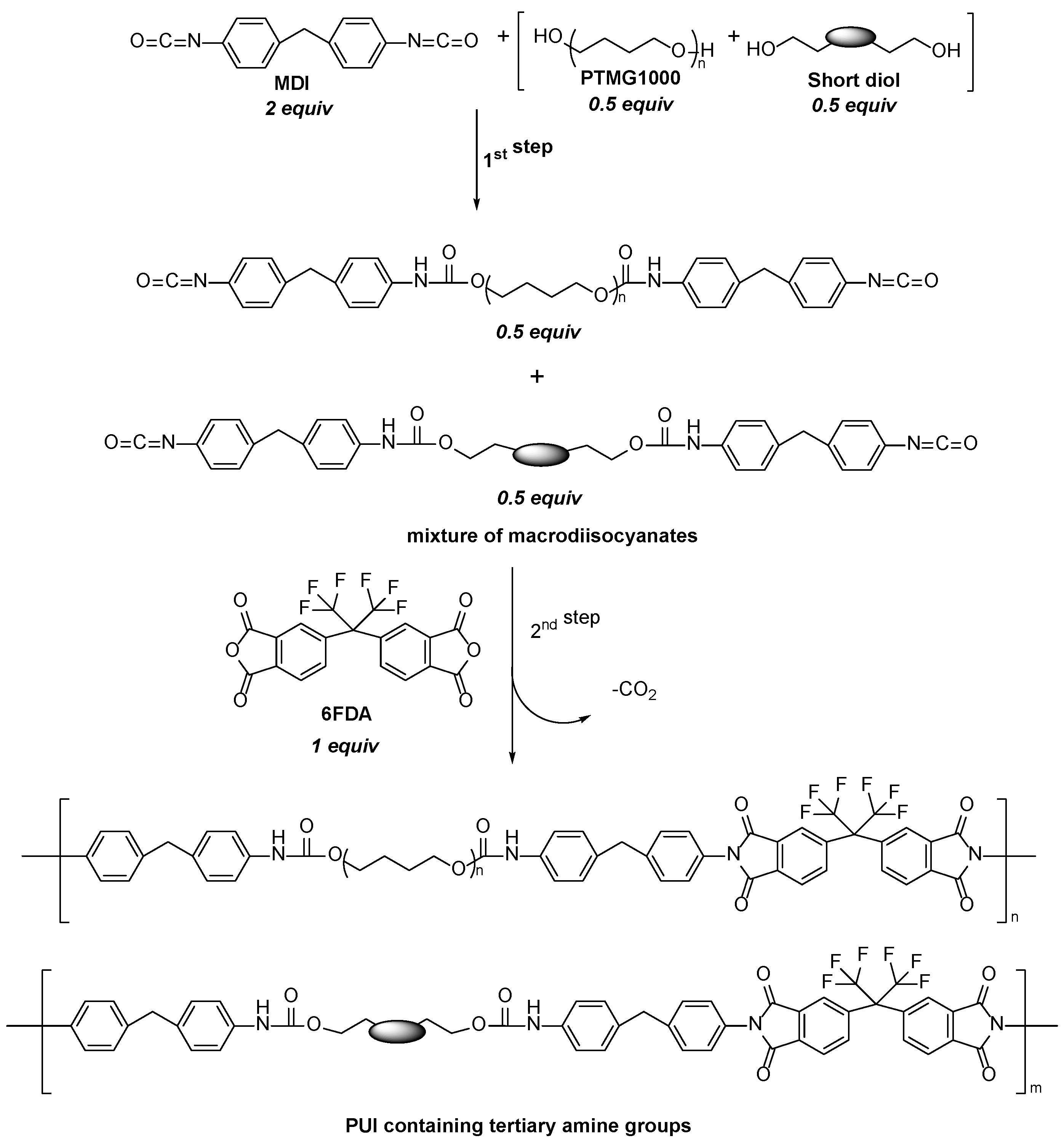

- Youssef, I.B.; Alem, H.; Sarry, F.; et al. Functional poly(urethane-imide)s containing Lewis bases for SO2 detection by Love surface acoustic wave gas micro-sensors. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2013, 185, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Zhu, C.; et al. AgNWs@SnO2/CuO nanocomposites for ultra-sensitive SO2 sensing based on surface acoustic wave with frequency-resistance dual-signal display. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2023, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kim, H.B.; Roh, Y.R.; et al. Development of a saw gas sensor for monitoring so2 gas. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 1998, 64, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A.; Poirier, M.; Riley, G.; et al. Gas detection using surface acoustic wave delay lines. Sensors and Actuators. 1983, 4, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Wang, W.; Pan, Y.; et al. Research on detection system of surface acoustic wave sensor array based on Internet of Things. Journal of Zhengzhou University (Engineering Science) 2016, 37, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rabus, D.; Friedt, J.M.; Arapan, L.; et al. Subsurface H(2)S detection by a surface acoustic wave passive wireless sensor interrogated with a ground penetrating radar. ACS Sens. 2020, 5(4), 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Che, J.; Cao, Q.; et al. Highly sensitive surface acoustic wave H2S gas sensor using electron-beam-evaporated CuO as sensitive layer. Sensors and Materials. 2023, 35(7), 2293–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Che, J.; Qiao, C.; et al. Highly porous Fe2O3-SiO2 layer for acoustic wave based H2S sensing: mass loading or elastic loading effects? Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 367, 132160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Enhanced sensitivity of a hydrogen sulfide sensor based on surface acoustic waves at room temperature. Sensors. 2018, 18(11), 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.L.; Zhang, Y.F.; Liang, Y.; et al. Design of surface acoustic wave sensor for rapid detection of hydrogen sulfide. Journal of Zhengzhou University (Engineering Science) 2019, 40, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Murakawa, Y.; Hara, M.; Oguchi, H.; et al. 5.4.5 A Hydrogen Sulfide Sensor Based on a Surface Acoustic Wave Resonator Combined with Ionic Liquid. 14th International Meeting on Chemical Sensors, Sendai, Japan, 20-23 May 2012.

- Murakawa, Y.; Hara, M.; Oguchi, H.; et al. Surface acoustic wave based sensors employing ionic liquid for hydrogen sulfide gas detection. Microsystem Technologies. 2013, 19(8), 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Simulant | Simulated chemical warfare agent (CWA) | Median lethal dose (LD50) inhaled (ppm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl methylphosphonate (DMMP) | Sarin (GB) | 18 | [25] |

| Dipropylene glycol monomethyl ether (DPGME) | Nitrogen mustard (HN) | 180 | [25] |

| Chloroethyl ethyl sulfide (CEES) | Distilled mustard (HD) | 140 | [26] |

| Dibutyl sulfide (DBS) | Distilled mustard (HD) | 140 | [27] |

| Chloroethyl phenyl sulfide (CEPS) | Distilled mustard (HD) | 140 | [27] |

| 1,5-Dichloropentane (DCP) | Distilled mustard (HD) | 140 | [25] |

| Dimethylacetamide (DMA) | Distilled mustard (HD) | 140 | [25] |

| 1,2-Dichloroethane (DCE) | Distilled mustard (HD) Soman (GD) |

140 6 |

[25] [25] |

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Phosgene (CG) | 800 | [25] |

| Polymer | Abbr. | Method | c | r | s | a | b | l | R | Std error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(epichlorohydrin) | PECH | SAW | -0.75 | 0.44 | 1.44 | 1.49 | 1.3 | 0.55 | 0.993 | 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).