1. Introduction

To manufacture a product, effective and efficient utilization of technical personnel, physical resources, and information is crucial (Chang, 2005; Sharon et al., 2011). The responsibility for this crucial task is generally assigned to engineering management (Savage et al., 2019). Engineering management is a diverse field that combines the principles of engineering, business administration, and management to plan, design, organize, supervise, and lead technical projects, teams, and organizations. It applies engineering and management principles to ensure that engineering projects are completed on time, within budget, and to the required quality standards. The responsibilities of an engineering manager include coordinating and collaborating with different stakeholders involved in a project, such as engineers, clients, vendors, and regulatory bodies, while managing people, resources, and risk. Engineering management encompasses a broad range of topics, including technology management, quality control, project management, cost analysis, design, procurement, construction, commissioning, project control, quality assurance/quality control, project service, and more. Ultimately, engineering management aims to effectively and efficiently utilize technical personnel, physical resources, and information to produce products or services that meet an organization's goals and objectives (Lannes, 2001; Farr et al., 2001; Daughton, 2017; Savage et al., 2019).

The resource allocation, decision-making processes, and the overall organizational strategy are handled by manufacturing management to ensure effective operations (Womack and Jones, 2003; Chang, 2005; Jacobs et al., 2011). In this regard, manufacturing management can significantly impact engineering management (Ahmad et al., 2017).

Based on the provided definition, manufacturing management refers to the planning, coordination, and control of the production process to ensure that goods are produced efficiently, on time, and to the required quality standards. It involves managing the resources and activities involved in the manufacturing process, including people, materials, equipment, and information. (Stevenson, 2019).

Inefficient manufacturing management can lead to suboptimal use of resources, delays in production schedules, and reduced productivity, negatively impacting engineering management. On the other hand, by implementing effective manufacturing management systems, organizations can optimize resource allocation and streamline decision-making processes. This can result in improved production processes and increased efficiency in utilizing technical personnel and physical resources. (Chase et al., 1998; Jacobs et al., 2004; Slack et al., 2010; Egilmez et al., 2018).

Often, manufacturing environments may experience various rapid and sudden changes, a lot of uncertainty, unforeseen risks, unpredictable events, and/or uncontrollable fluctuations (Mollajan et al., 2023). Considering that manufacturing management assumes the role of overseeing resource allocation, decision-making processes, and the overarching organizational strategy, it is crucial that the manufacturing management is capable enough of identifying, analyzing, and mitigating potential risks that may arise during the production process. This includes risks related to equipment failure, supply chain disruptions, safety hazards, quality issues, and other factors that may impact the production process or product quality (Pallagst et al., 2013; Selviaridis et al., 2014; Egilmez et al., 2018).

The poor design of manufacturing processes can significantly contribute to the occurrence and propagation of operational risks (Rahmani and Thomson, 2011; Mollajan et al., 2021; Mollajan et al., 2022). A poorly designed manufacturing process architecture lacks alignment with good design principles, leading to complexity, low modularity, inefficient resource allocation, and limited flexibility. This deficiency increases the risk of errors, defects, and safety hazards, while hindering adaptation to evolving requirements and unforeseen challenges. Inefficient processes drive up production costs, waste materials, and introduce more errors. They also impede problem identification and resolution, resulting in delays and complications. Poor process design also limits visibility and hampers process improvement over time (Rahmani and Thomson, 2011). On the other hand, A well-designed manufacturing process architecture offers benefits to manufacturing and engineering management. It facilitates bottleneck detection and improvement identification, supported by comprehensive documentation and efficient communication channels. Real-time monitoring enables prompt issue detection and resolution, enhancing overall efficiency (Cheng et al., 2012). Effective design is crucial in minimizing the likelihood of operational risks and their potential impact on manufacturing processes (Mollajan et al., 2023).

The design of manufacturing processes has a cascading effect on engineering management in addition to manufacturing management. In fact, design and management of manufacturing processes have a significant impact on engineering management. Engineering teams bear the responsibility of designing, implementing, and improving these processes, which necessitates specific skills and expertise aligned with the complexity and level of automation employed. Furthermore, the effectiveness of engineering management systems, including quality control and continuous improvement programs, relies on the underlying architecture of manufacturing. Therefore, the design of manufacturing processes architecture falls within the scope of engineering management responsibilities, offering an opportunity for them to make a substantial impact.

Achieving a well-designed architecture for manufacturing processes is crucial, and manufacturing management plays a pivotal role in contributing to engineering management. One of the most effective and critical ways in which manufacturing management can make this contribution is by actively participating in the design phase of a product. By involving manufacturing experts from the outset, potential production and assembly challenges can be identified and addressed proactively, resulting in an optimized manufacturing process. This collaborative approach ensures the development of an efficient and streamlined process, ultimately leading to the creation of high-quality products.

2. Design of Robust Architecture for Manufacturing Processes

When it comes to manufacturing processes, particularly in the face of environmental disturbances, the significance of robustness cannot be overstated. A robust design for manufacturing processes is key to ensuring that a manufacturing process can withstand, adapt to, and recover from any unforeseen disruptions that may arise.

Al-Refaie (2011) contributed to the understanding and modeling of robustness, highlighting the need for comprehensive methodologies that consider the various factors influencing performance. Koc et al. (2011) conducted a study on process parameter variation in worm hydroforming, aiming to optimize quality, robustness, and capability. They employed response surface analysis with a Box-Behnken design to optimize parameters and evaluate process capability using univariate indices such as Cp and Cpk. However, the study did not consider the interrelationships among response variables and noise variables, indicating the need to account for these factors in robustness assessments. The challenges associated with noise variables in robustness studies were highlighted by Mevik et al. (2001) and Robinson, Borror, and Myers (2004). Their work emphasized the limitations of certain designs, such as BBD, in effectively accounting for noise variables, which are crucial for studying robustness.

Scholz-Reiter et al. (2011) suggested improving robustness by enhancing production capacities through resource utilization optimization. They explore how optimizing resource utilization can contribute to robustness in production systems. Karimi and Djokoto (2012) also discussed the topic of robust stability analysis, further emphasizing the importance of accounting for uncertainties and disturbances in manufacturing processes. Kusumoto et al. (2012), they also discuss robust management in manufacturing systems, focusing on product and process robustness. They emphasize the importance of state-space analysis and structured analysis tools in achieving robustness. Alem and Morabito (2012) implement a robust optimization scheduling approach in furniture manufacturing. Their study surpasses deterministic worst-case methods in most situations, demonstrating the effectiveness of robust optimization techniques in improving robustness in manufacturing processes. Meyer et al. (2013) conducted research to analyze the influence of capacity adjustments on the performance robustness of different operational key figures in manufacturing systems. Their study investigated the trade-off between the robustness of operational performance and cost-efficiency, emphasizing the importance of systems being able to withstand fluctuations and disturbances to maintain high performance and profitability. Mondal et al. (2013) focused on the measurement and modeling of robustness in serial multi-stage manufacturing processes. They employed sensitivity analysis and sensitivity matrices to evaluate and measure the robustness of these processes. The authors highlighted the complexities and interactions present in multi-stage processes, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive understanding of robustness measurement. However, they acknowledged that their methods were more suitable for large batch production scenarios and may not be effective in situations such as one-kilogram production. Additionally, Mondal (2013) introduced a modeling approach that incorporated input-output and in-process parameters to assess and model process robustness in manufacturing systems. They demonstrated the application of their approach through a numerical example involving a two-stage worm gear manufacturing process. Malmström et al. (2013) explored the relationship between resource constraints and robustness in smaller companies. Their findings contribute to understanding the challenges faced by these companies in achieving and maintaining high levels of robustness. Montgomery (2013) emphasized the importance of interaction effects and noise variables in achieving robustness in design and manufacturing. He highlighted the need to understand their impact and efficiently incorporate them in experiments. Montgomery also discussed the relationship between process capability and robustness, emphasizing the need for further modeling and understanding. These insights contribute to the understanding of robust design and process robustness. Xiong et al. (2013) conducted research on evaluating the robustness of production systems. They introduced indicators related to material variances, free capacity, and the overlap between slack periods and machine failure. Their studies explored the system's ability to handle disruptions and maintain smooth operations. Additionally, they focused on evaluating robustness in a flexible job shop problem using the concept of float time. Their research provided valuable insights into the impact of machine and tool breakdowns on the robustness of production systems. Becker et al. (2013) defined MS robustness as the ratio of feasible operations with disruptions of a specific machine to the total feasible operations without disruptions. The specific details or context of their research are not mentioned in the text. Sharda and Banerjee (2013) presented a mathematical optimization model for designing a robust manufacturing system (MS). Their model incorporated factors such as processing times, equipment failure and repairs, and product demand to improve performance in the face of uncertainties. The model aimed to minimize makespan, mean work-in-progress (WIP), and the number of machines, considering these uncertainties during the design process. Mondal et al. (2014) critically reviewed robust approaches for measuring and modeling process robustness in product and manufacturing processes. This research contributed to understanding the effectiveness of existing methodologies and techniques in assessing and modeling process robustness. Taguchi's concept of process robustness emphasized designing processes less sensitive to variations and disruptions for consistent performance. Stricker and Lanza (2014) conducted research that supports the importance of robustness in production systems. They utilized the Value-at-Risk (VaR) measure as an indicator of robustness and explored its implications in uncertain environments. Their work contributes to the understanding of robustness and its role in the success of production systems. Bebera and Becker (2014) focused on exploring the relationship between the topological characteristics and dynamic behavior in manufacturing networks. They highlighted the importance of the network's static structure, represented by its topology, and the material flow within the network in influencing factors such as performance and robustness. Varas et al. (2014) contributed to the field of robust optimization by demonstrating its benefits in reducing variability and uncertainty in production schedules. Their work specifically focused on a sawmill scenario, highlighting the effectiveness of robust optimization strategies. Benderbal et al. (2015) emphasized the significance of technical disruptions in production systems. They analyzed the impact of these disruptions on system robustness and focus on optimizing schedules and designs. Tian et al. (2015) introduced sensitivity analysis to analyze the effects of machining parameters in the electrical discharge machining process. Their research focused on understanding the sensitivity of these parameters and their impact on the overall process. Putnik et al. (2015) studied the impact of system size and network structure on the robustness of production networks under changing demand. They defined robustness as the ratio of production rate with perturbations to production rate without perturbations, exploring the relationship between system characteristics and robustness. Their research assessed robustness in manufacturing systems, without specifying the approach or measure used. Benderbal et al. (2015) explored robustness in a reconfigurable production system using an average-based measure that quantified potential delays from machine failure. Their study highlighted various approaches to measuring robustness, including time span, float time, and average-based measures, providing insights into the system's ability to handle variations and disruptions. Stricker et al. (2015), their work reinforces the notion that high robustness is associated with costs. They provide insights into the trade-off between robustness and cost considerations in manufacturing systems. Giannetti and Ransing (2016) improved output quality in the steel foundry industry using tolerance synthesis to assess process robustness. Their robustness indicator, a likelihood ratio, compared the likelihood of achieving the expected output using modified input parameter regions. Validation of their methodology demonstrated its potential in improving output quality. Zhao et al. (2016) investigated the performance evaluation of the axial ventilator in the turbofan engine lubrication system. Their study aimed to assess the sensitivity of the ventilator's performance to different factors. Meyer (2016) examined the role of redundancy in achieving robustness in manufacturing system performance. The study derived specific definitions of robustness and redundancy for the manufacturing context and explored indicators such as nestedness and elementary flux modes. Analysis of different manufacturing system configurations revealed a significant correlation between redundancy and robustness. These findings emphasized the potential of incorporating robustness in the design of manufacturing systems. Boorla and Howard (2016) contribute to the discussion of robust management in manufacturing systems. They highlight the significance of robustness measures and analysis in ensuring the resilience of products and manufacturing processes. Sakhaii et al. (2016) further contribute to the topic of technical disruptions in production systems. Their research explores the optimization of system characteristics and the impact of these disruptions. Moslemi et al. (2017) focus on modeling robustness in multistage manufacturing systems, introducing process capability as a surrogate measure of robustness. They utilize response surfaces and a robust coefficient estimation method to analyze quality characteristics. The results demonstrate the superiority of the robust multistage process and highlight the relationship between robustness and capability in multistage manufacturing. This research contributes to understanding robustness in multistage processes and the use of robustness indices as surrogates. Zeng and Yen (2017), their work focuses on the impact of global value chains on production systems. They highlight how optimizing costs in these chains can increase vulnerability to factors like geo-political disputes and transportation issues, further emphasizing the need for robustness.

Zhang et al. (2017), their research primarily focuses on ensuring robustness in manufacturing systems through technology control. They address the importance of technological advancements and control mechanisms in achieving robustness. Himmiche et al. (2018) conducted a study on the impact of disturbances and uncertainties on meeting deadlines in a production system. They evaluated various machine capacity plans and assessed the likelihood of meeting deadlines under these conditions. Additionally, their research focused on addressing technical disruptions, such as machine and tool breakdowns, and optimizing system characteristics to enhance robustness. Efthymiou et al. (2018) explore robustness in the aerospace domain, applying their metric in a supplier flow workshop. Their approach quantifies capability and enhances controllability across scenarios using likelihood-based indicators. The case study showcases the practical application of their approach, providing valuable insights into production system robustness in the aerospace industry. Pagone et al. (2019) focused on the association between high robustness and costs. They contribute to the understanding of the economic implications of achieving and maintaining robustness in manufacturing operations.

Frederico et al. (2020) addressed the challenges posed by digitization in production systems. They highlight the need for rapid adaptation to new technologies, business models, and competitors, underscoring the importance of robustness in these dynamic environments. Martín et al. (2020) illustrated the benefits of a robust optimization approach in achieving high robustness at lower costs in an automotive supplier context. Their study compared the performance of the robust optimization approach with heuristic planning approaches for production schedules, emphasizing the cost-effectiveness of the robust optimization strategy.

Hyder et al. (2021) tackled uncertainty and sustainability in cloud manufacturing, exploring tools and proposing a Collaborative Cloud Service Platform (CCSP) to enhance supplier-customer-manufacturer relations while considering robustness and sustainability in service composition. Stockmann et al. (2021) emphasized a holistic approach to assess robustness in production systems, considering tradeoffs between performance, resource requirements, and output. Their methodology evaluated robustness from an input-throughput-output perspective, connecting it with adjacent capabilities for a comprehensive understanding of production system robustness. Liang and Li (2022) explored cooperation uncertainty's impact on robustness in manufacturing service systems (MSS). They proposed a methodology treating MSS as a network of service subsystems to identify critical paths and standardize cooperation mechanisms for enhanced robustness.

Exhibit 1 presents a comprehensive overview of the significant aspects of the present study, in comparison to the relevant studies found in the literature. The table showcases the diverse range of studies in the literature, which primarily concentrate on various aspects such as developing mathematical/statistical methods, presenting informative process capability indices, incorporating robust design principles, introducing useful robustness measures, and considering the complexity of interrelationships among manufacturing processes to tackle the issue of robustness in manufacturing process structure. Additionally, a select few of these studies also approach the problem from systems engineering perspective, specifically addressing the concept of system architecture. To achieve such robustness, a system engineering approach is adopted in the present study. This approach recognizes that all activities involved in forming the manufacturing process should be viewed as an integrated system, working together harmoniously to enhance its robustness. It is worth noting that within this category of studies, only a limited number of works propose modularization as an effective approach for achieving robustness in manufacturing processes.

Exhibit 1 provides an overview of studies that utilize the Axiomatic Design (AD) theory to modularize the system architecture and contribute to the design of robust manufacturing processes. However, the literature review reveals that the focus has mainly been on the allocated architecture of the system, neglecting the significance of the process architecture in system robustness. According to the AD theory (Suh 2001), the physical components of the system, which are part of the physical architecture, are influenced by a set of process variables (such as men, machines, methods, and materials) belonging to the process architecture. Therefore, this study emphasizes the importance of considering modularity in the process architecture, as it indirectly supports modularity in the allocated architecture. In other words, examining the modularity of the process domain architecture is crucial for the effective allocation of components within the physical system. The literature currently lacks a clear understanding of how modularization of manufacturing processes architecture can effectively enhance the robustness of the system architecture while minimizing system complexity. This gap emphasizes the need for a mathematical model that elucidates the relationship between manufacturing processes architecture robustness and system architecture modularization. Such a model would provide valuable support to systems engineers in designing robust manufacturing processes architecture.

The purpose of this study is to address this significant gap in the literature and develop a mathematical model that precisely defines the proposed approach. By clarifying the relationship between manufacturing processes architecture and system architecture through modularization, the model aims to facilitate the creation of a robust characteristic in the manufacturing processes architecture while ensuring controlled system complexity.

To modularize the system architecture and consider the identified modules more effectively, this study employs the DSM methodology.

The paper is organized as follows: The introduction provides an overview of the study.

Section 2 discusses the robust architecture for manufacturing processes, including a literature review and identification of research gaps.

Section 3 presents background materials related to the topic. In

Section 4, the research method and mathematical model development are described, specifically focusing on the relationship between "modularity" and the property of "robustness of manufacturing processes."

Section 5 offers a case study that applies the robustness analysis method to manufacturing processes in Barez Industrial Group, an Iranian company. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by discussing the conclusions drawn from the robustness analysis method and providing practical recommendations.

Exhibit 1.

Features of the present research comparing with the relevant researches.

Exhibit 1.

Features of the present research comparing with the relevant researches.

| Features |

|---|

| |

Development of a Statistical/Mathematical Optimization Model |

Process Capability Indices Consideration |

Utilization of Robust Design Principle |

Utilization of Response Surface Methodology |

Development of Measurement of Robustness |

Complexity of Interrelationship in Manufacturing Processes |

Consideration of Manufacturing Processes Architecture |

Modularization of Manufacturing Processes Architecture |

| This Research |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

| Al-Refaie (2011) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Koc et al. (2011) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Mevik et al. (2001) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Robinson, Borror, and Myers (2004) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Nourelfath (2011) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Scholz-Reiter et al. (2011) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Karimi and Djokoto (2012) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Kusumoto et al. (2012) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Alem and Morabito (2012) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Meyer et al. (2013) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Mondal et al. (2013) |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Malmström et al. (2013) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Montgomery (2013) |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Mondal et al. (2013) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Becker et al. (2013) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Sharda and Banerjee (2013) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Xiong et al. (2013) |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Mondal et al. (2014) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Stricker and Lanza (2014) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Bebera and Becker (2014) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Varas et al. (2014) |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Benderbal et al. (2015) |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Tian et al. (2015) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Putnik et al. (2015) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Benderbal et al. (2015) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Stricker et al. (2015) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Giannetti and Ransing (2016) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Zhao et al. (2016) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Meyer (2016) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Boorla and Howard (2016) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Sakhaii et al. (2016) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Moslemi et al. (2017) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Zeng and Yen (2017) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Zhang et al. (2017) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Himmiche et al. (2018) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Efthymiou et al. (2018) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Pagone et al. (2019) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Frederico et al. (2020) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Martín et al. (2020) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Hyder et al. (2021) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Stockmann et al. (2021) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

| Liang and Li (2022) |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

3. Background Material

3.1. Robustness

There is a wide variety of definitions for robustness. According to Carlson and Doyle (2002), robustness is “the maintenance of some desired system characteristic despite fluctuations in the behavior of its component parts or its environment”. Fricke and Schulz (2005) define robustness as “a system’s ability to be insensitive towards changing environments. Robust systems deliver their intended functionality under varying operating conditions without being changed”. We use the definition by Barber and Salido (2011): robustness is the ability of a system to withstand stress, pressure, perturbations, unpredictable changes or variability in its operating environment without loss of functionality.

3.2. Axiomatic Design (AD) Theory

The Axiomatic Design (AD) Theory is a coherent framework rooted in techniques and logical thought processes, aimed at conducting design activities in a systematic and scientific manner (Suh, 1990). The primary elements employed within AD encompass 'Domains', 'Mapping and Zigzagging', the 'Independence (First) Axiom', and the 'Information (Second) Axiom'.

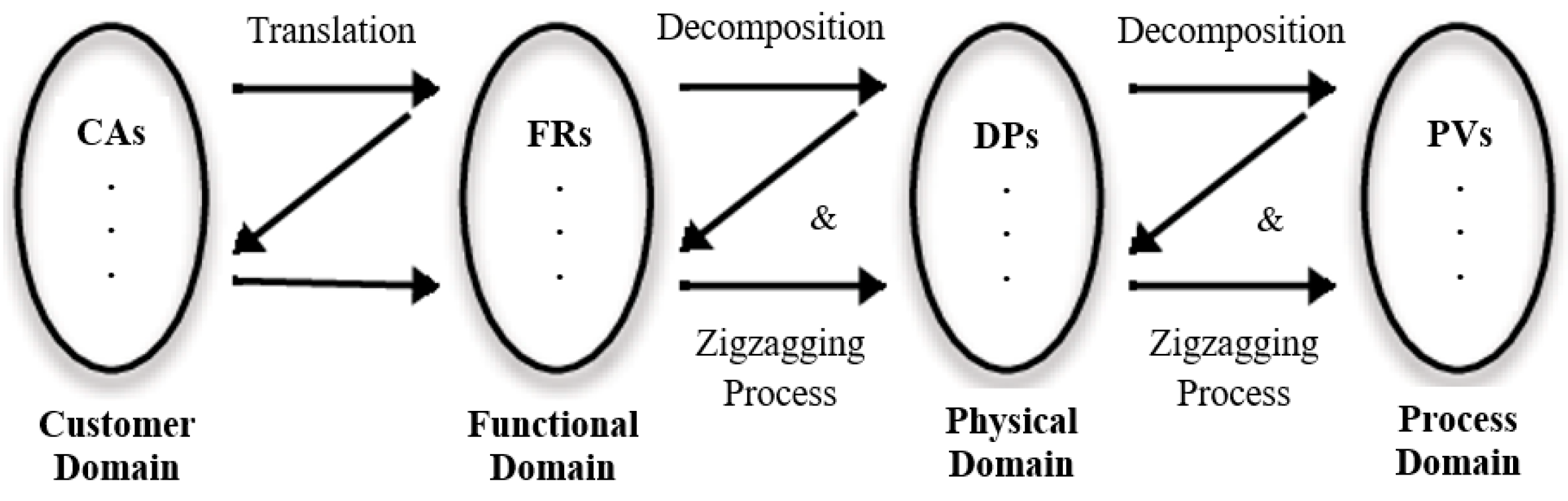

The Axiomatic Design (AD) method is a well-structured approach established to guide design activities across four distinct design domains: the 'Customer Domain', the 'Functional Requirements (FRs) Domain', the 'Physical or Design Parameters (DPs) Domain', and the 'Process Variables (PVs) Domain' (as depicted in

Exhibit 2). The customer domain encapsulates customer attributes (CAs). These attributes' elements need to be transformed into functional requirements (FRs) and constraints (Cs) within the functional domain. To fulfil these FRs, design parameters (DPs) are established within the physical domain. Ultimately, to bring the system into production, process variables (PVs) are defined within the process domain. The design process operates as a dynamic interplay between two adjacent domains, cascading in a top-to-bottom manner, commencing at the system level and progressively delving into sublevels of finer detail until a comprehensive representation of the system of interest emerges. The linkage between two contiguous domains is aptly named the 'zigzagging' process, achieved by methodically breaking down the system into smaller design components (as illustrated in

Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2.

Design domains in Axiomatic Design (AD) theory

Exhibit 2.

Design domains in Axiomatic Design (AD) theory

The AD theory offers two design axioms for gauging the quality of solutions and provides guidance on how to assess and choose from various alternatives (Suh, 2001).

Independence Axiom: Preserve the autonomy of the FRs (DPs). This axiom emphasizes that each FR (DP) should maintain its autonomy. Therefore, system designers face a pivotal challenge in disassembling intricate systems into subsystems characterized by independent FRs (DPs).

Information Axiom: Minimize the informational complexity of a design. This axiom asserts that among designs adhering to the Independence Axiom, the one with the lowest informational complexity is regarded as the optimal design choice. The informational complexity associated with a particular FR (DP) quantifies the likelihood of achieving a given FR (DP) successfully (Suh, 2001).

In allocation between functional and physical domains, the informational complexity of a design with a single FR and DP can be expressed as the logarithm of the reciprocal of the probability of system success in fulfilling the FR (P, Equation 1);

Where ‘I’ denotes the information content, measured in bits (logarithm to base 2), and signifies the extent of effort needed to accomplish the given FR.

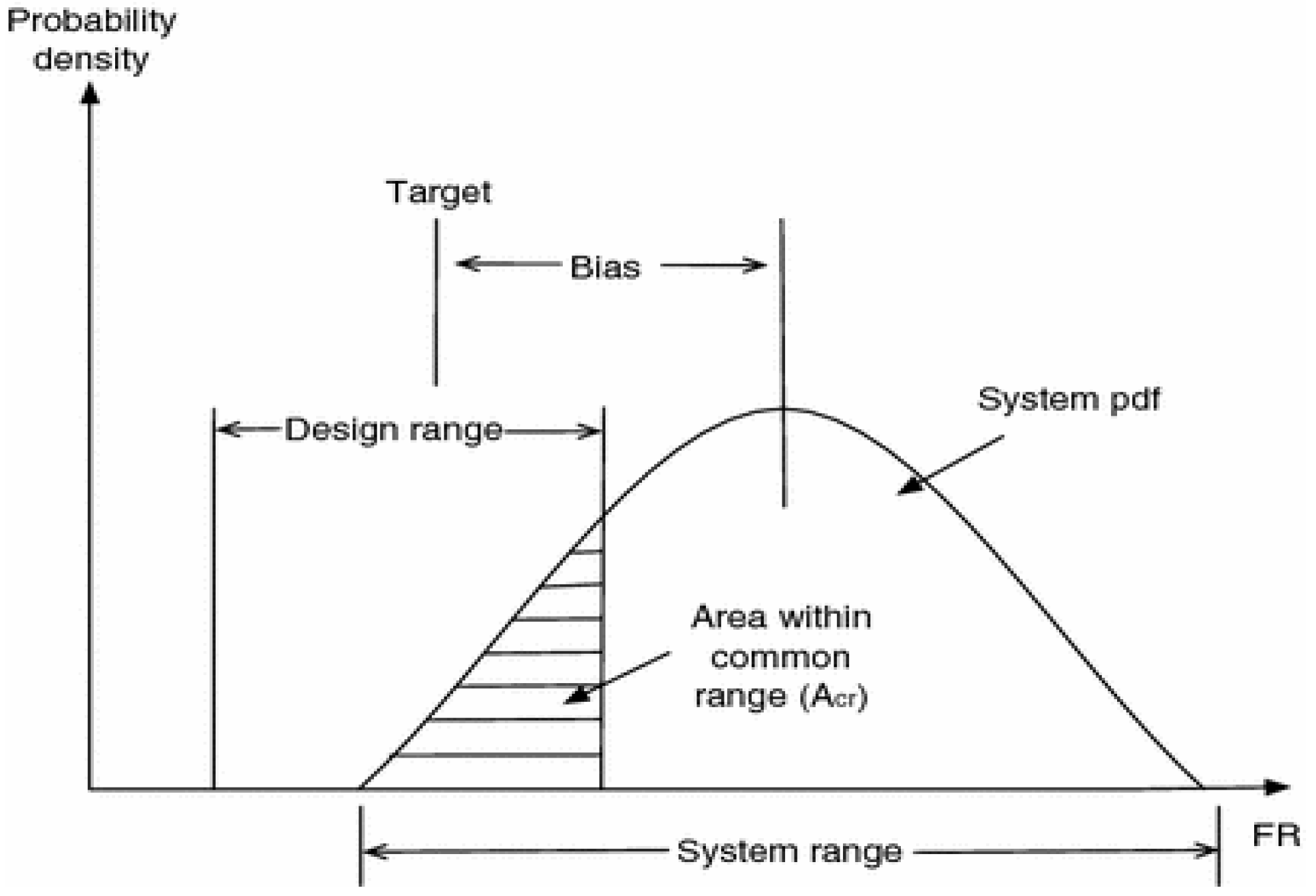

With the assumption of a uniform probability density function (pdf), the information content ‘I’ can be formulated as depicted in Equation (2);

The system range's extent is represented as SR, calculated from the probability density function of the FR. In essence, the SR of a particular FR signifies the performance range, PR, linked with the FR in question. The shared range's size, CR, constitutes the segment of the earlier mentioned area within the design range, DR, as illustrated in Exhibit 3. The DR defines the admissible scope linked to the relevant FR.

In the context of an uncoupled design involving n FRs (DPs), the aggregate information is formulated according to Equation (3);

where ‘Pi’ represents the probability of FRi (DPi) being fulfilled by DPi (PVi).

Exhibit 3.

Probability of success in fulfilling a functional requirement (FR).

Exhibit 3.

Probability of success in fulfilling a functional requirement (FR).

3.3. Design Structure Matrix (DSM) Methodology

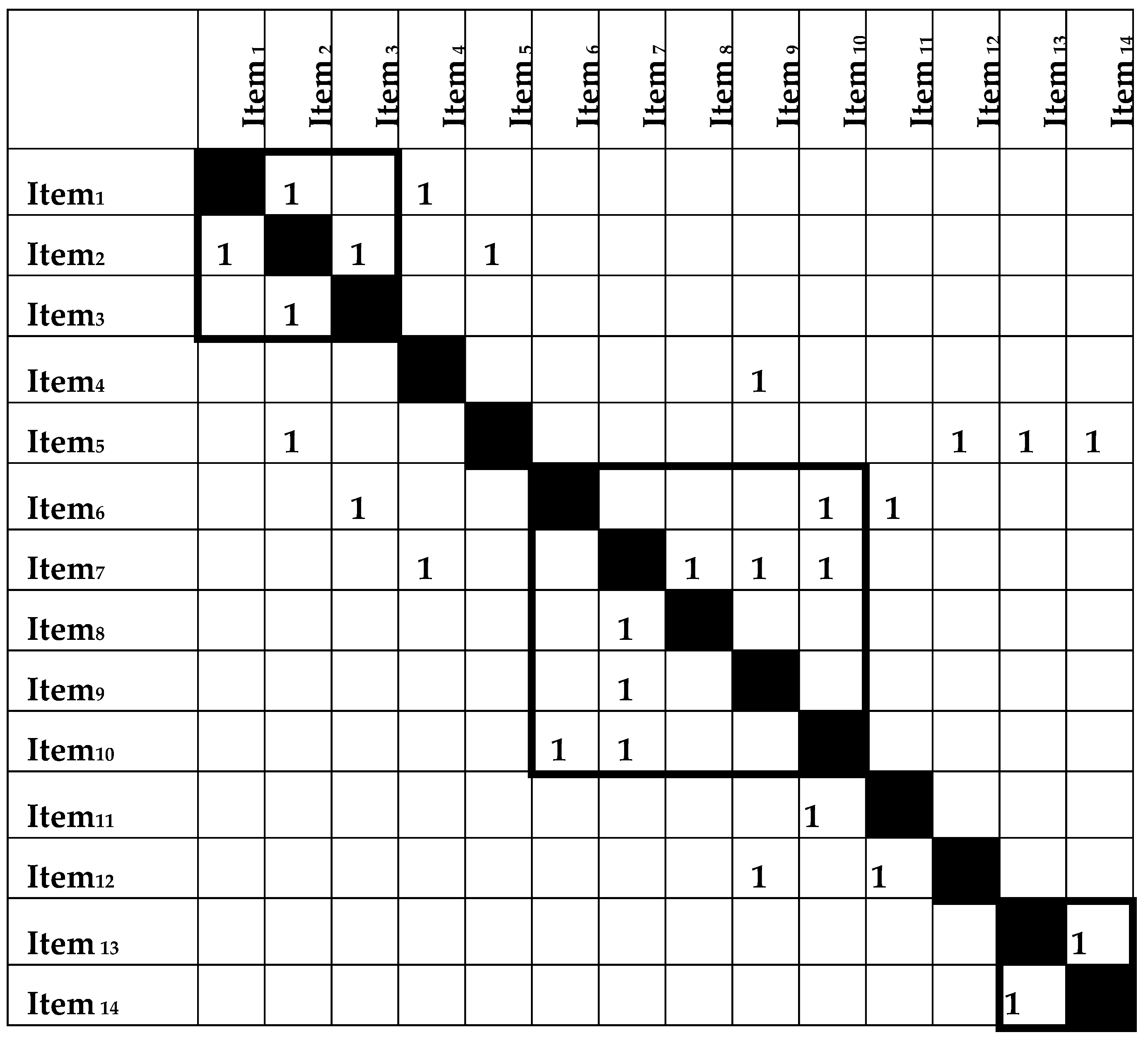

A Design Structure Matrix (DSM) stands as a potent method for illustrating intricate interdependencies among components within a system. Serving as a versatile and straightforward modelling tool, the DSM aids in the design, depiction, and management of systems. The DSM encapsulates a system's architecture by denoting interactions and dependencies among its elements. Forming a binary square matrix with m columns and rows, along with n non-zero elements, where m symbolizes the nodes and n signifies the directed connections linking them, the DSM captures the intrinsic structure. Within a set of m elements within a system, the corresponding DSM takes shape as an m×m matrix, wherein the system elements occupy row and column headings, following the same order. Precedence relationships manifest in the matrix's off-diagonal entries. In a binary DSM, the value of entry ij (column i, row j) is one (or marked by "X" or "●") when element j depends on element i (i.e., i feeds j), while otherwise, it remains zero (or left vacant). Sequentially aligning the elements as they appear in the DSM, marks below the diagonal denote forward information from element i to j, and those above the diagonal embody feedback information from element j to i.

Central to DSM analysis is the aspiration to minimize feedback loops, achieved by orchestrating the sequencing of processes/elements, thereby facilitating a lower-triangular DSM formation. The marks above the diagonal signify feedback couplings, contrasting with the sub-diagonal marks denoting feed-forward couplings. The above-diagonal markings connote iterative interactions, which should ideally be reduced as much as feasible. However, when feedback marks cannot be eliminated, the implicated elements can be categorized into iterative sub-cycles. In Exhibit 4, for example, items (1, 2, 3) and items (6, 7, 8, 9, 10) fall into two such iterative sub-cycles.

Typically, the realization of this objective necessitates a two-step approach: partitioning and tearing (Eppinger and Browning, 2012; Huang et al., 2015), holds promise for achieving optimal results.

Exhibit 4.

Design Structure Matrix (DSM) illustrating the interconnections among elements within the system.

Exhibit 4.

Design Structure Matrix (DSM) illustrating the interconnections among elements within the system.

3.4. Modularity in System Architecture

Definition

The literature review underscores the wide array of definitions associated with the term 'Modularity' (Gershenson et al., 2003; Lameche et al., 2017). Generally, the definition of modularity emanates from the characterization of the constituent modules within a system. In essence, these definitions can primarily be categorized into two groups: 'Structural' definitions (These pertain to the relationships and interactions among the system components (Browning, 2001)). 'Architectural' definitions (These address the connections between system components and the functions established at a specific abstraction level within the functional domain (Stone et al., 2000), or through the relationships between models of physical and/or logical representations of systems (Faulconbridge and Ryan, 2014; Kruchten, 1995)). Regarding the notion of modularization within each of these classes, a comprehensive elucidation has been provided by Efatmaneshnik et al. (2018). In general, the process of modularization aims to maximize the dependency within modules while minimizing relations or interactions between modules (Baldwin and Clark, 2003; Gershenson et al., 2003).

3.5. Measures of Modularity for an Individual Architecture (Functional/Physical / Process Architecture)

Various modularity indices assess system architecture. Jung and Simpson (2017), Bonvoisin et al. (2016) reviewed many. Tools like modularity matrix (Dahmus et al., 2001), heuristics (Stone et al., 2000), DSM (Steward, 1981), axiomatic design (Suh, 2001), etc., identify modules. This study chooses DSM for module identification, considering its benefits.

To gauge modularity using the Design Structure Matrix (DSM) methodology, the literature offers a range of metrics (Yu, Yassine, and Goldberg, 2007; Hölttä-Otto and de Weck, 2007; Hölttä-Otto et al., 2012). The research emphasizes studying important interactions between element pairs. Among various modularity measures, focus is on those developed from interactions among the elements. Notably, five key metrics stand out: 'Grouping Capability Index (GCI)', 'Grouping Efficacy', 'Grouping Efficiency', 'Utilization Rate (U)', and 'Modularization Function' (Mikkola, 2006; Mikkola and Gassmann, 2003), which have been frequently utilized (Gupta, 2019; Al-Bashir et al., 2016).

Before proceeding to the measures, establishing notation is beneficial. Let N1 be the count of 1s in diagonal blocks, N2 be the count of 0s in diagonal blocks, N3 be the count of 0s in off-diagonal blocks, and N4 be the count of 1s in off-diagonal blocks. Moreover, N1+N2 indicates the total number of elements (0s and 1s) in diagonal blocks, and N3+N4 represents the total number of elements (0s and 1s) in off-diagonal blocks. The following section provides a detailed outline of the measures.

The Grouping Capability Index (GCI) signifies the capacity of a collection of interdependent entities to establish a module (Equation (4)).

- 2.

Grouping efficacy

Grouping efficacy, denoted as τ, quantifies the ability of a module or group to perform a task. It is contingent on the successful clustering of elements within a group. (Equation (5)).

- 3.

Grouping efficiency

Grouping efficiency, represented as η, serves as a measure of the fit quality for a modular solution within a module. A higher η value indicates a more suitable modular arrangement.

η (Equation (6)) symbolizes the relative capacity of components to form a module or group, as well as the compactness of a module.

and

are expressed by Equations (7) and (8), respectively.

Where, q is a weighting factor (0<q<1);

- 4.

Utilization rate

Utilization rate, denoted as U, indicates the extent to which components within a given system are dedicated to forming modules and how effectively they contribute to building modular systems (Equation (9)).

- 5.

Modularization Function

The Modularization Function, denoted as M(u), was initially developed by Mikkola and Gassmann (2003), and subsequently refined by Mikkola (2006).

Where ‘u’ signifies the count of distinctive elements/components encompassed within an architecture; "N" denotes the total number of standard and unique components, calculated as N = nSTD + u; 𝛿 represents the average intensity of coupling among elements/components and modules; "s" indicates the substitutability factor of unique elements/components within other systems. Additionally, there exists a relationship between 𝛿 (coupling intensity) and "k" (number of interfaces in a module), expressed as 𝛿∼ (𝑘/𝑛), where "n" represents the count of components in a module.

3.6. Measure of Modularity between Two Adjacent Domains

It is possible to determine a quantitative measure of independence for a given design matrix. Suh (2001) proposes two metrics of independence: reangularity, R, and semangularity, S. Reangularity evaluates the orthogonality between DPs and serves as a measure of interdependence.

The angle between the DP axes is denoted by θ (Equation 11). To provide additional clarity on the concept of reangularity, let us examine a two-dimensional case.

where

represents the entry (i, j) of the DM and relates DP

j to FR

i (i, j = 1, 2). Equation (12) can be rewritten as

where

For the nth dimensional case, reangularity is

The metric S quantifies the angular relationship between the axes of DPs and FRs, evaluating the correlation between a given FR and any pair of DPs. In terms of coupling, S represents the magnitude of the diagonal elements in a normalized DM. In the case of an nth-dimensional scenario,

Both R and S have a maximum value of 1, corresponding to an uncoupled (ideal) design. As the degree of coupling increases, both reangularity and semangularity decrease. In particular, when R or S is equal to 0, the design is considered fully coupled.

3.7. Metrics for System Robustness

System robustness reflects the degree of system coupling. According to the mathematical equations for R and S, it is clear that, as both R and S belong to the interval [0,1], the larger R and S are, the greater R*S is. Concerning the information content of a system, I, the smaller the information content is, the smaller is the variability of the system where (R*S)/I becomes larger and can be employed to quantify the robustness of a system (Gao and He, 2015).

3.8. Robustness Analysis Method

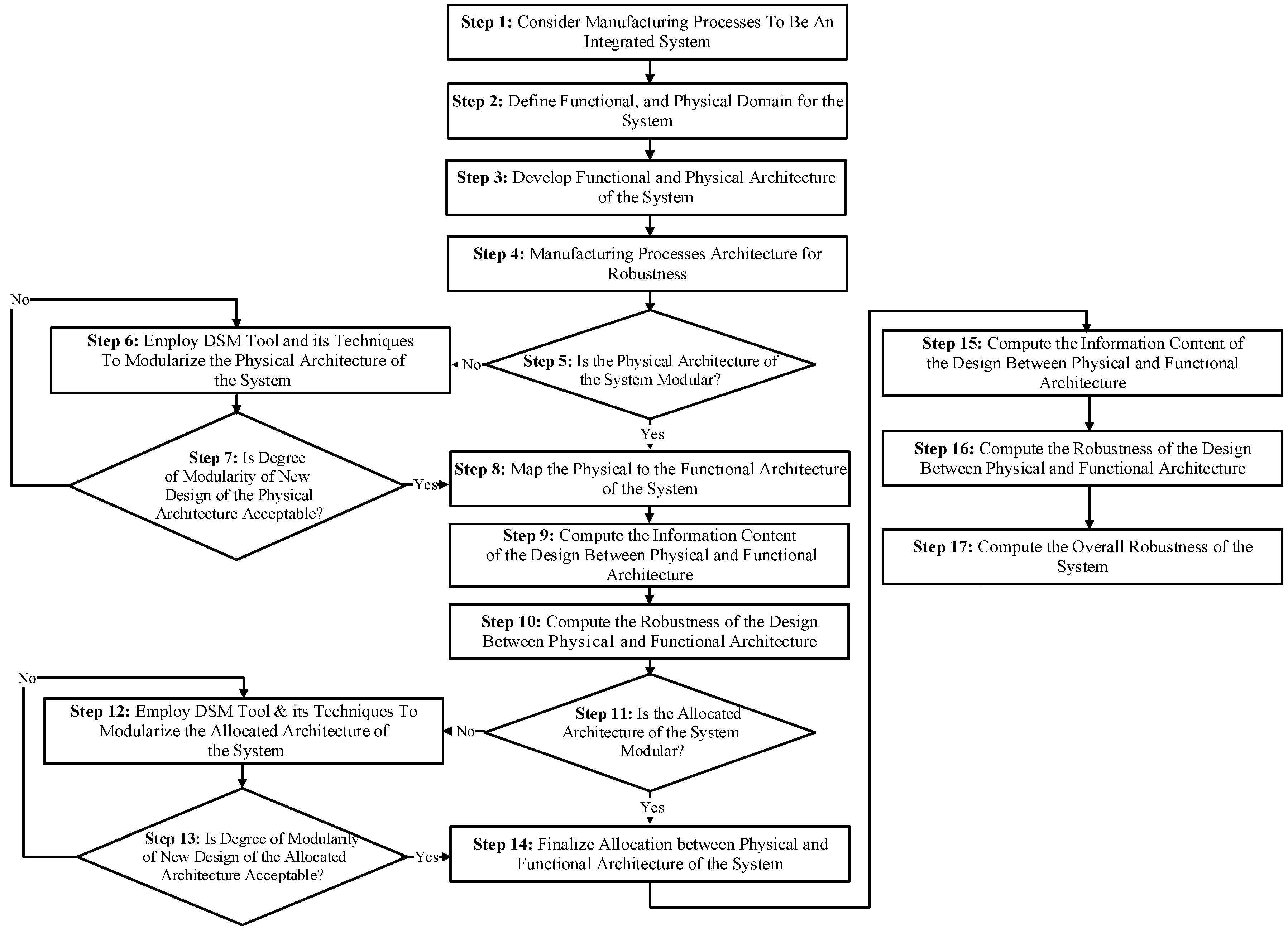

The robustness analysis method looks at the relationship among contract clauses and evaluates alternative sequences. Managers can then choose the best organization of clauses to improve modularization and overall contract robustness. The steps of the method are described below and presented schematically in Exhibit 5:

Steps 1 Consider manufacturing processes as an integrated system

Step 2, 3 Develop functional and physical architecture of the system

Step 4 Design manufacturing processes architecture for robustness

Steps 5, 6, 7 use DSM to modularize the physical architecture of the system

Step 8 Map the physical to the functional architecture of the system

Step 9, 10 Calculate system architecture's information content and robustness

Steps 11, 12, 13 use AD theory to modularize the mapping between the new physical architecture and the functional architecture

Step 14, 15 Recompute system architecture's information content and robustness

Step 16 compute the overall robustness of the system.

Exhibit 5.

Methodology for the Robust Analysis Method.

Exhibit 5.

Methodology for the Robust Analysis Method.

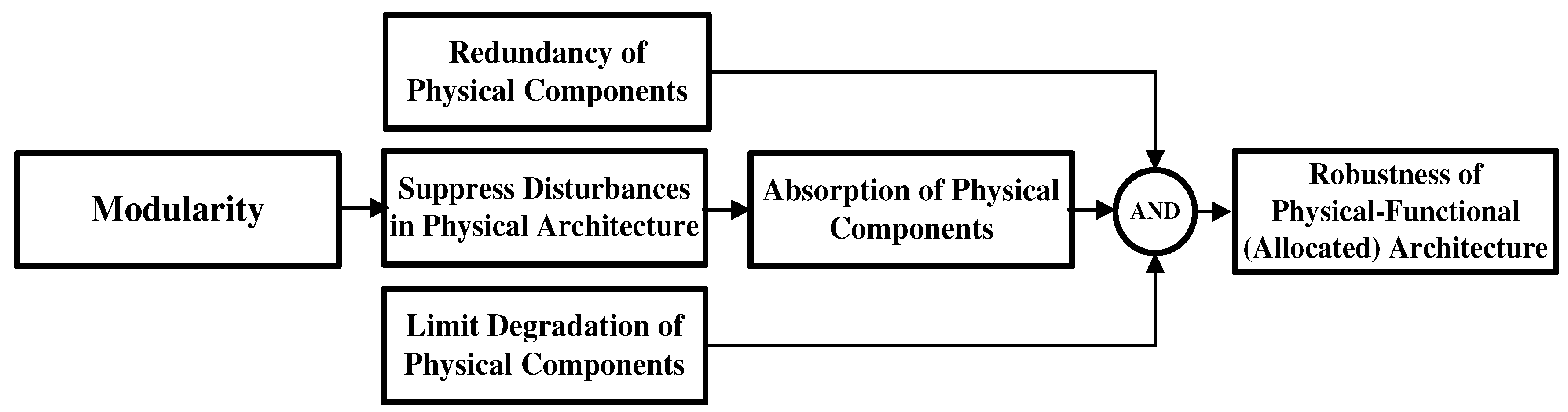

3.9. Contribution of the Study: Modularity and Robustness

Once robustness is analysed, mapping between a contract’s functional and physical architectures needs to be done, and determination of how well the physical elements satisfy the functional elements needs to be evaluated. A literature review of design robustness has indicated that both physical component redundancy and limiting the degradation of physical components have been mentioned by several authors (Jackson and Ferris, 2013; Jackson et al., 2015). In the present study, the focus is on avoiding propagation of failure/disruption/ disturbance, i.e., suppression of disturbances and redundancy in some of physical component in the physical architecture. To avoid propagation failures in a contract, the functional and physical components should not be coupled and the physical components should be independent. Robustness is achieved by having a significant level of modularity that avoids propagation of noise from an affected/impaired module or clause to other modules. Following is a mathematical investigation that demonstrates that modularity suppresses disturbances in the physical architecture as shown in Exhibit 6, where better modularity leads to better contact clauses, and ultimately, greater project success. The mathematical analysis underpins the use of AD Theory and DSM in the robustness analysis method.

Exhibit 6.

Modularity and Robustness.

Exhibit 6.

Modularity and Robustness.

3.10. Modularity and System Variance

System robustness can be improved by minimizing variance. In a multi-FR design, the prerequisite for minimizing variance is the satisfaction of the independence axiom. To mathematically consider the relationship for coupling, i.e., the absence of modularity and system variance, consider an n dimensional case

where (i=1, 2, …, n) represents the ith module in FRs domain,

(i=1, 2, …, n) represents the ith module in DPs domain,

represents a DM which associates DP-based modules with FR-based modules, and

(i=1, 2, .., n and j=1, 2, .., n) are DM submatrices that have one or more dimensions where (j=1, 2, .., n) is allocated to the (i=1, 2, …, n).

In addition,

represents the transposition of the matrix.

where represents the domain of FR-based modules (the functional domain), and represents the domain of DP-based modules (the physical domain).

The random variability of

, i.e.,

can be expressed as

where

represents random variability of

. It is clear that

and

are

where represents the random variability in (i=1, 2, …, m), and represents the random variability in (j=1, 2, …, m).

The transposition of equation (20) is

Therefore, the variance of the

is

where E expresses the mathematical expectation. Hence, the variance of

,

, is

where represents the variance-covariance matrix for .

Assume that the DP-based modules, , are statistically independent of each other.

where

represents the variance or variance-covariance matrix of module

and (i=1, 2, …, m) when the module is one dimensional or multi-dimensional. Then,

Moreover, the system variance,

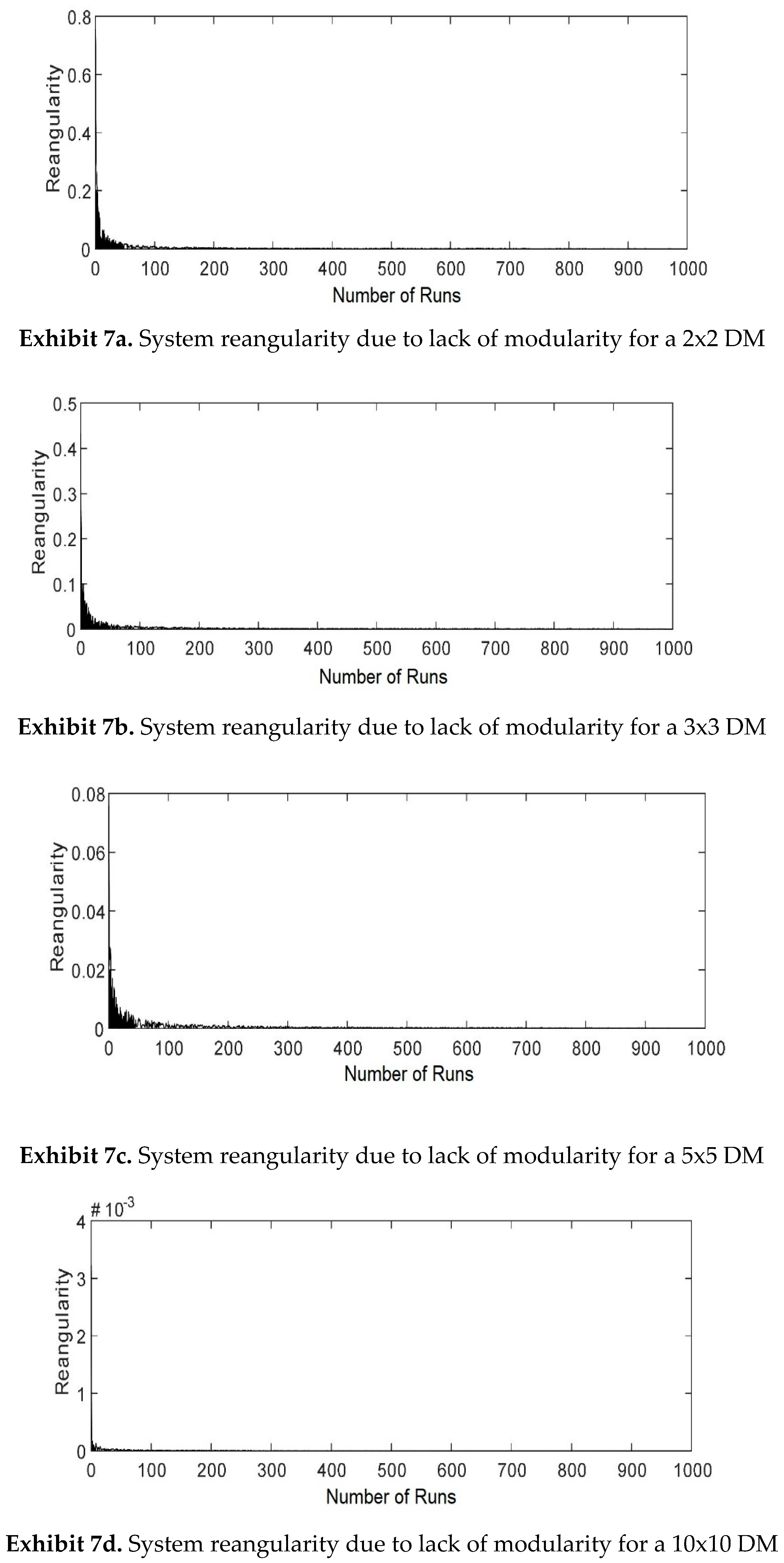

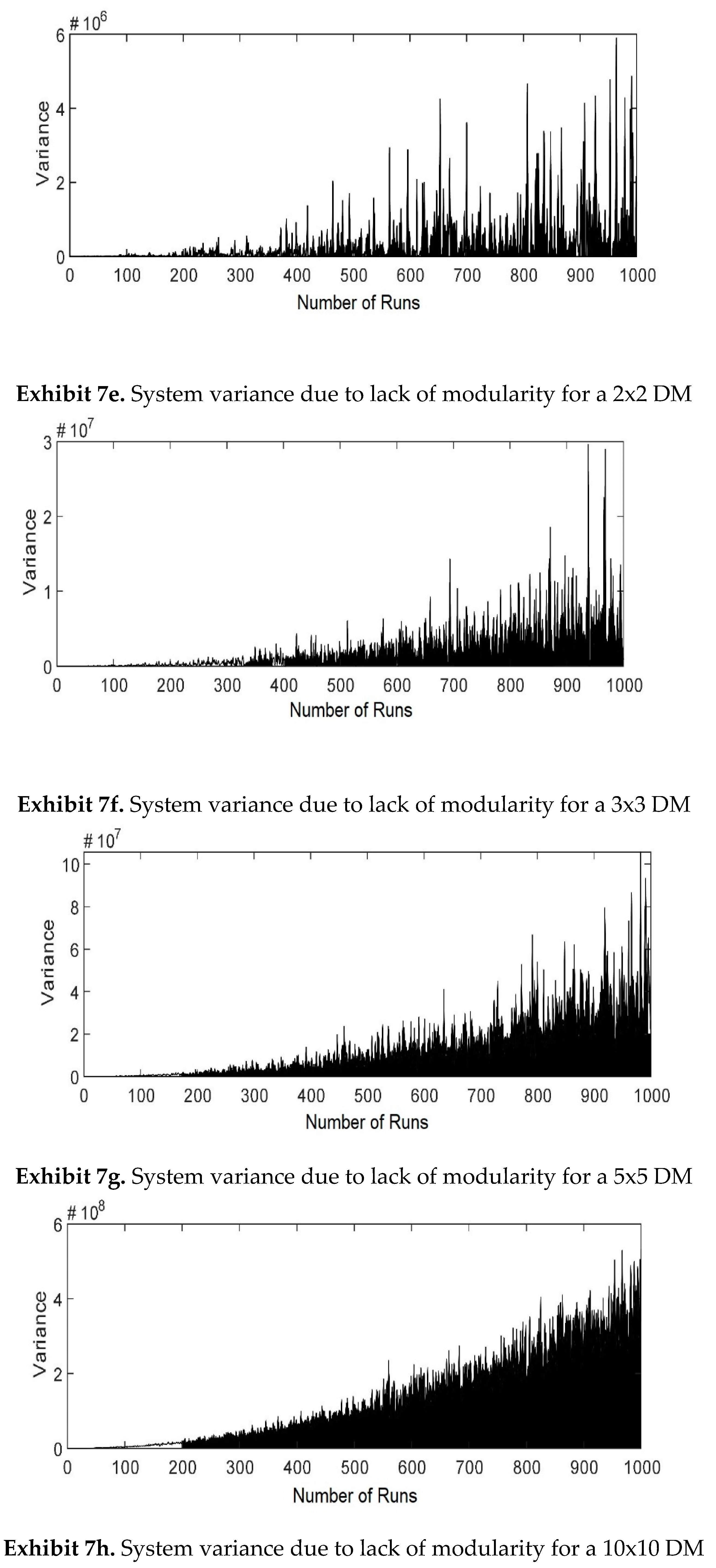

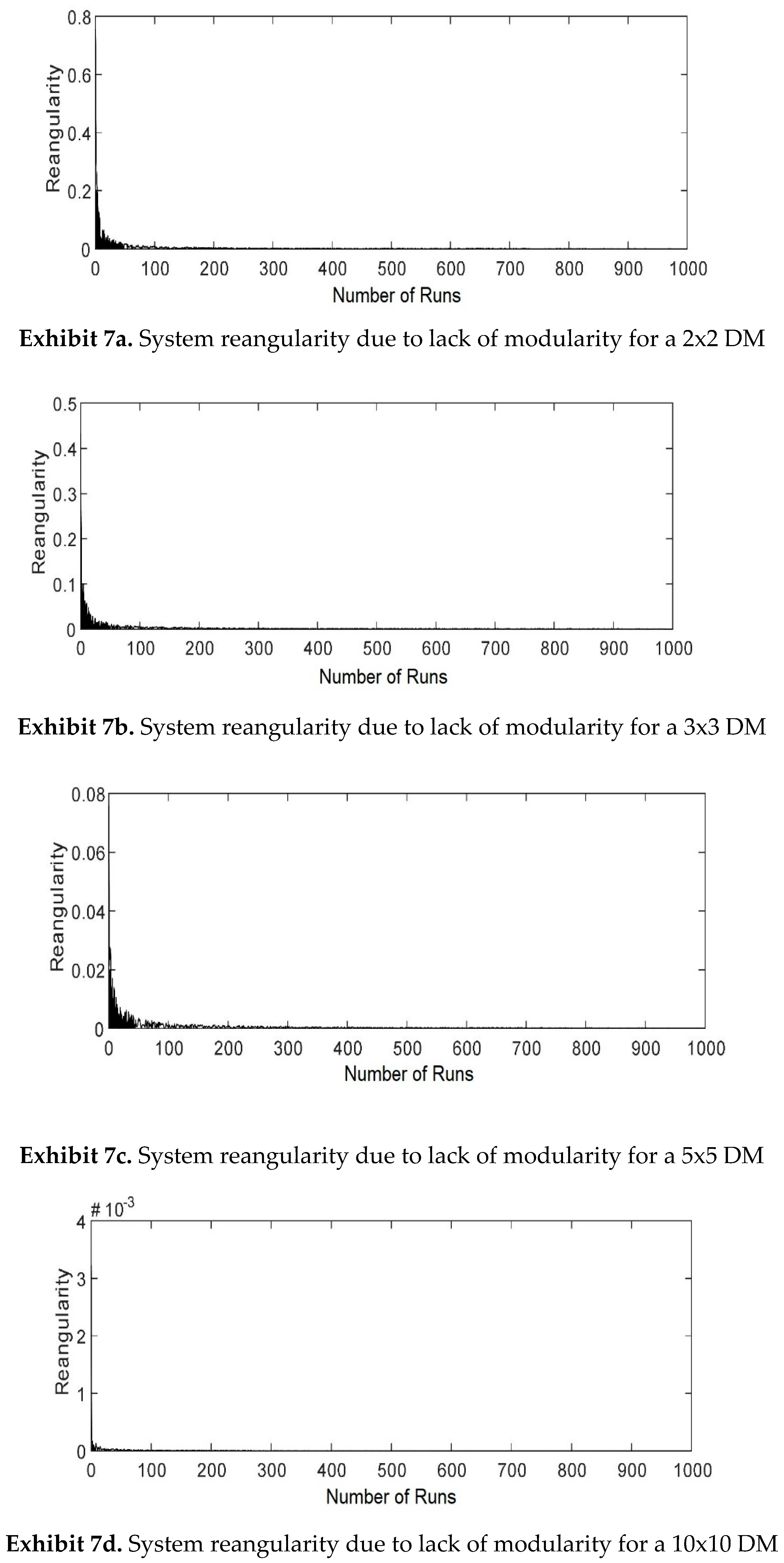

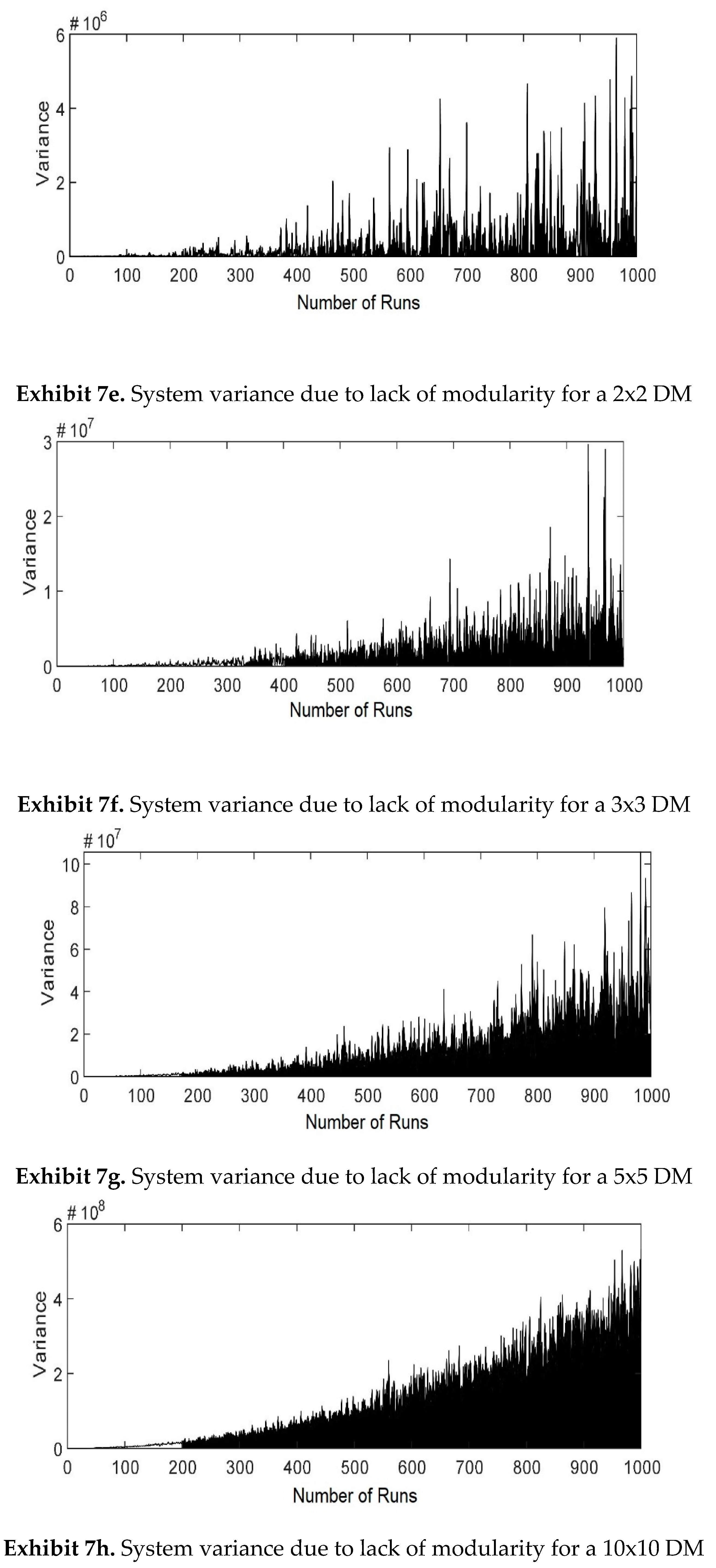

The larger the off-diagonal entries become, the higher is the system variance, i.e., a higher system variance indicates a more coupled system design. The development of a simple, well-defined equation to clarify the relationship between reangularity/semangularity and the lack of modularity may not be easy. However, the behavior of semangularity and reangularity with respect to the magnitude of off-diagonal entries of the DM are relatively similar. To demonstrate the degree of coupling, i.e., the lack of system modularity, for DMs with higher dimensions, computer simulation was used for four square DMs with sizes of 2×2, 3×3, 5×5, and 10×10 that were randomly generated 1000 times. The magnitude of the off-diagonal elements was gradually increased as the number of runs increased, which showed the effect of coupling on semangularity/reangularity and system variance. Exhibits 7a-d show reangularity versus lack of modularity where reangularity becomes smaller as the size of off-diagonal elements increases. Exhibits 7e-h show system variance versus lack of modularity where system variance becomes larger as the size of off-diagonal elements increases. This underlines the need to reduce the coupling among contract clauses as done in the robustness analysis method.

3.11. Modularization of the Allocated Architecture (Mapping between Two Adjacent Domains)

The allocated architecture of a contract refers to the organization of physical elements that yields a design solution which satisfies the functional requirements of a contract. Therefore, modularity of the allocated architecture is essential to achieving a robust contract. Sometimes, due to possible disruptions in project conditions, redundant clauses are used to increase a contract’s reliability to have a better chance of project success. When creating modules, then, it is important to determine whether there is any clause or module that is redundant since the use of redundant elements may result in a loss of contract modularity.

Concerning the improvement of contract reliability, the present study adopts the notion of redundancy from AD theory where in redundant designs there are more DPs than FRs to satisfy the FRs (Suh, 2001; Park, 2007; Heo and Lee, 2007; Gonçalves-Coelho et al., 2012). For instance, a contract objective may be described by a few clauses in such a way that if the most appropriate clause is not able to satisfy the objective, other associated clauses, as redundant elements, can be used to meet the objective. Nevertheless, contract modularity must be ensured. The following two subsections provide more detail about the modularization of the allocated architecture in the absence and presence of redundant physical modules.

3.12. Modularization of the Allocated Architecture in the Absence of Redundant Physical Modules

To map between DP-based and FR-based domains, consider a multi-FR design

where represents the ith module in the functional domain (i=1, 2, .., n), and represents the ith module in the physical domain (i=1, 2, .., n).

Note that

or

can be a module which can encompass only one element or several fully/partially coupled elements. Using equation (34), the derivative of

, i.e.,

where,

represents the derivation of

. If

or

is a module of only one element, equation (36) can be utilized straightforwardly. However, when

or

is a vector which includes several fully/partially coupled elements, equation (36) needs to be expressed as the following. Let

and

(i=1, 2, …, n) be a vector that includes a specific subset of FRs and DPs, respectively. Then,

It is assumed that FRs are independent of each other whereas the associated DPs are partially/fully coupled to each other. Therefore,

can be expressed as

where represents the jth module in the physical domain with k1 DP elements,

represents the pth member of jth module (p=1, 2, …, k1),

represents the qth member of the jth module (q=1, 2, …, k1), and

represents the entry (p,q) in matrix X and signifies the degree of dependency between and (p=1, 2, …, k1 ; q=1, 2, …, k1).

Matrix X in which all diagonal elements are zero is employed to express that every element of

is coupled with the remaining elements. Then,

In addition, assume that

A is the design matrix (

which allocates DPs into FRs that belong to the module

. Therefore,

Incorporating equation (40) into equation (41)

Using equation (44), the derivative of

, i.e.,

(i=1, 2, …, n), is

In order to compute

, consider

. Now,

is

where (.

must be within the required tolerance; thus,

where is the desired change in due to a change in , and is the required tolerance.

In an uncoupled design, must be equal to . The deviation from this ideal condition, , is given by or where or is a module of only one element (case I) or a vector (case II) that includes several fully/partially coupled elements. For an uncoupled system, the required tolerance, must be ≥ or ≥ in case I or II.

Specifically, for case I, consider

, then,

Specifically, for case II, consider

, then,

Equation (61) provides a criterion for determining when the off-diagonal elements of a basic matrix can be disregarded.

3.13. Independence and Tolerance Theorem

An independence and tolerance theorem can be formulated as follows: In case I, a design is considered uncoupled when the specified tolerance,

, exceeds...

Therefore, the non-diagonal elements of the design matrix can be disregarded. If the

(k= 1, 2, ..., n), which represents the stiffnesses relating changes of

to the changes of

, are constant, then...

If , then, the design is uncoupled.

3.14. B. Modularization of the Allocated Architecture in Presence of Redundant Physical Modules

In this case, there are more

than

, resulting in random variability (or noise) introduced by the excess

that can affect the variability of

. It's crucial for the variability to remain within the design range to ensure proper functionality. Therefore,

The random variability in is denoted as , and the variability of is represented by In an ideal one- design, only a single is necessary, as any additional introduce the possibility of random variability. The first term on the right-hand side (RHS) of equation (65) accounts for the compensation effect of the primary , which is selected to vary , while the second term represents the cumulative random variability or noise introduced by any extra . To ensure proper functionality, it's crucial to adjust the error term in two possible ways to achieve .

This approach eliminates the random fluctuations that may arise from additional units used during operations, while ensuring that the tolerance range specified in the design is met for . The primary unit must be capable of compensating for any random variations resulting from the use of extra units.

3.15. B. 2. Multi- Design

In a multi-

design where the number of

units exceeds that of

units, the design becomes redundant and each

unit may be affected by multiple

units. Consequently,

Let's consider the following scenario: {

} represents the

selected to fulfill the vector {

}, with the number of

in {

} being equal to the number of

in {

}. The vector {

}

Extra, which appears as the second term on the right-hand side of equation (67), contains redundant

that remain after {

} satisfies {

}, but these extra

may not be explicitly known. The square matrix [Square DM] represents the relationship between {

} and {

}, while [Extra Matrix] describes how the extra

affect the

. To ensure compliance with the independence axiom, [Square DM] should be either diagonal or triangular. On the other hand, [Extra Matrix] can take any form, including a full matrix, and still satisfy the independence axiom as long as [Square DM] is diagonal or triangular. Specifically, let's look at a special case of equation (67) where we are dealing with a multi-

design consisting of k

and numerous

.

where represents the ith (i=1, 2, …, k) module in the functional domain,

represents the jth (j=1, 2, …, n) module in the physical domain,

represents the pth member of jth module in the physical domain for (p=1, 2, …, k1), and represents the sub-design matrix within DM and relates DPs of to the associated FRs of to satisfy them.

The first term on the right-hand side (RHS) of Equation (68) represents an uncoupled design, while the second term depicts a fully coupled design. However, even with the presence of the second term, this design can still be treated as an uncoupled design if we establish a fixed value for

through

. We can then use

,

,… and

to ensure the independence of

,

, … and

. In such cases, the design range of

would be:

and

When the diagonal design matrix of the first term on the right-hand side (RHS) of Equation (68) is substituted with a triangular matrix in Equation (71), the resultant design can be treated as a decoupled design

Random variability in

through

can be counteracted by using fixed values for

,

, …, and

, provided that any extra terms are fixed first and remain the same across all locations where they are used. In this manner, the design range

may be achieved using

(j=1, 2, …, k), which is:

is the primary controller for . are secondary controllers chosen to satisfy , with a secondary effect on due to off-diagonal elements. is not a primary controller and is the source of random variability. (j=1, 2, …, k) should be set first according to the sequence defined by the triangular matrix to control the corresponding (j=1, 2, …, k). The variability caused by the extra terms can be fixed by eliminating (j=k, k+1, …, n) through fixing . Finally, can be controlled using . If Square DM, the first term on the right-hand side of equation (73), is a full matrix, the design is coupled, which violates the independence axiom. In this case, it is not possible to satisfy the independence of each when unknown introduce random variability.

The previous discussion holds significant implications for designing a robust system that satisfies multiple

simultaneously. In a multi-

design, the selection of

,

, and

must meet the same set of conditions. However, in a decoupled multi-

design, we must also satisfy an additional condition for the elements of a triangular design matrix.

If equation (74) is not satisfied, it indicates an unacceptable design resulting from choosing the wrong . For instance, consider a scenario where diagonal elements have a smaller magnitude than off-diagonal elements. This implies that and , selected to control and , respectively, have a greater impact on than has on . In extreme cases, when one of the diagonal elements is significantly smaller than the off-diagonal elements, the design becomes coupled because one can influence more than two . Additionally, if the number of is less than the number of due to one or more diagonal elements being zero, the design becomes coupled due to an insufficient number of

4. Application

This study focuses on verifying the proposed methodology for analysing the robustness of manufacturing processes in the Iranian tire industry, specifically within 'Barez Industrial Group,' an enterprise based in Tehran, Iran, specializing in Tire Manufacturing since its establishment in 1984.

The manufacturing processes under investigation are the 'system of interest' (SOI), and their architecture is analysed in this study. Considering the dynamic nature of manufacturing environments, the study emphasizes the system's ability to cope with rapid changes. The existing architecture is examined from the perspective of robustness, aiming to identify any shortcomings or limitations. If significant weaknesses are detected, the study proposes a new architecture design based on the engineering design methodology presented in this research, ensuring the system's capability for robustness. By addressing the critical point of verifying the proposed methodology and emphasizing the importance of robustness in manufacturing processes, this study contributes valuable insights to the field of tire manufacturing and engineering design practices within 'Barez Industrial Group.'

4.1. Functional Architecture of the SOI

In step 2 of the research method, the functional architecture of the system of interest (SOI) is addressed and its constituent elements are studied. Applying the Axiomatic Design (AD) theory, the elements of the SOI within the functional domain of the system are identified, considering the elements as 'Functional Requirements' and tagging them with FRs. Exhibit 8 presents and describes these FRs of the SOI.

Exhibit 8.

Description of the leaf functional requirements (FRs) of the SOI.

Exhibit 8.

Description of the leaf functional requirements (FRs) of the SOI.

| Code |

Description |

Code |

Description |

| FR1111

|

Organize meetings for the research committee. |

FR1139

|

Request the required tests and follow up on the test. |

| FR1112

|

Make a decision about the annual budget. |

FR113,10

|

Prepare and archive APQP file documents. |

| FR1113

|

Define new projects for the offices. |

FR113,11

|

Prepare documents and archive SQA documents. |

| FR1114

|

Decide on the duration of projects. |

FR113,12

|

Check and prepare a product requirements chart, and turn it into a technical specification. |

| FR1115

|

Complete the project charter. |

FR113,13

|

Perform the process of improvement and change. |

| FR1121

|

Conduct phenomenological studies of the project. |

FR1141

|

Check test requests. |

| FR1122

|

Select the initial formulation. |

FR1142

|

Coordinate to receive tires from the production line. |

| FR1123

|

Produce the experimental mixture. |

FR1143

|

Plan to take the test. |

| FR1124

|

Evaluate the results. |

FR1144

|

Run the test. |

| FR1125

|

Optimize the formulation. |

FR1145

|

Review and analyze results. |

| FR1126

|

Produce a prototype. |

FR1146

|

Generate test reports. |

| FR1127

|

Acknowledge the research objectives. |

FR1151

|

Manage knowledge of the combined design process and the final product in all design aspects. |

| FR1128

|

Design the production process for in-line mixing. |

FR1152

|

Support the knowledge management process to fix product line defects. |

| FR1129

|

Prepare mixed pre-production samples. |

FR1153

|

Manage previous knowledge within the organization. |

| FR112,10

|

Prepare pre-production stage tires. |

FR1154

|

Coordinate the holding of internal seminars. |

| FR112,11

|

Validate to achieve project goals. |

FR1155

|

Coordinate and disseminate new sciences in the field of tire production. |

| FR112,12

|

Perform daily line production. |

FR1156

|

Receive and archive lessons learned related to research and development projects. |

| FR112,13

|

Prepare the mixture reference recipe and deliver it to the Research and Development Documentation Center. |

FR1157

|

Publish lessons learned at the organization level. |

| FR112,14

|

Prepare project documentation and store a copy in the archive of the mixture design office and deliver another copy to the documentation center. |

FR1221

|

Select the size and brand of comparable tires. |

| FR1131

|

Design the template profile and pattern. |

FR1222

|

Request to buy. |

| FR1132

|

Simulate and certify the design. |

FR1223

|

Determine the test and its standard. |

| FR1133

|

Prepare template drawings. |

FR1231

|

Issue processes based on design department ORDERS. |

| FR1134

|

Prepare the Common Technical Document (CTD). |

FR1232

|

Check the production notifications sent by the process department to decide on issuing or not issuing the process. |

| FR1135

|

Build the ORDER design. |

FR1233

|

Prepare PFMEA for all radial tire production processes. |

| FR1136

|

Issue the manufacturing process. |

FR1234

|

Investigate and eliminate the reasons for the non-functioning of the radial tire in the test center tests. |

| FR1137

|

Issue the baking process. |

FR1235

|

Carry out projects defined in meetings. |

| FR1138

|

Experimentally construct and cook, then examine defects and uniformity. |

FR1236

|

Prepare and update work standards for different parts of radial riding. |

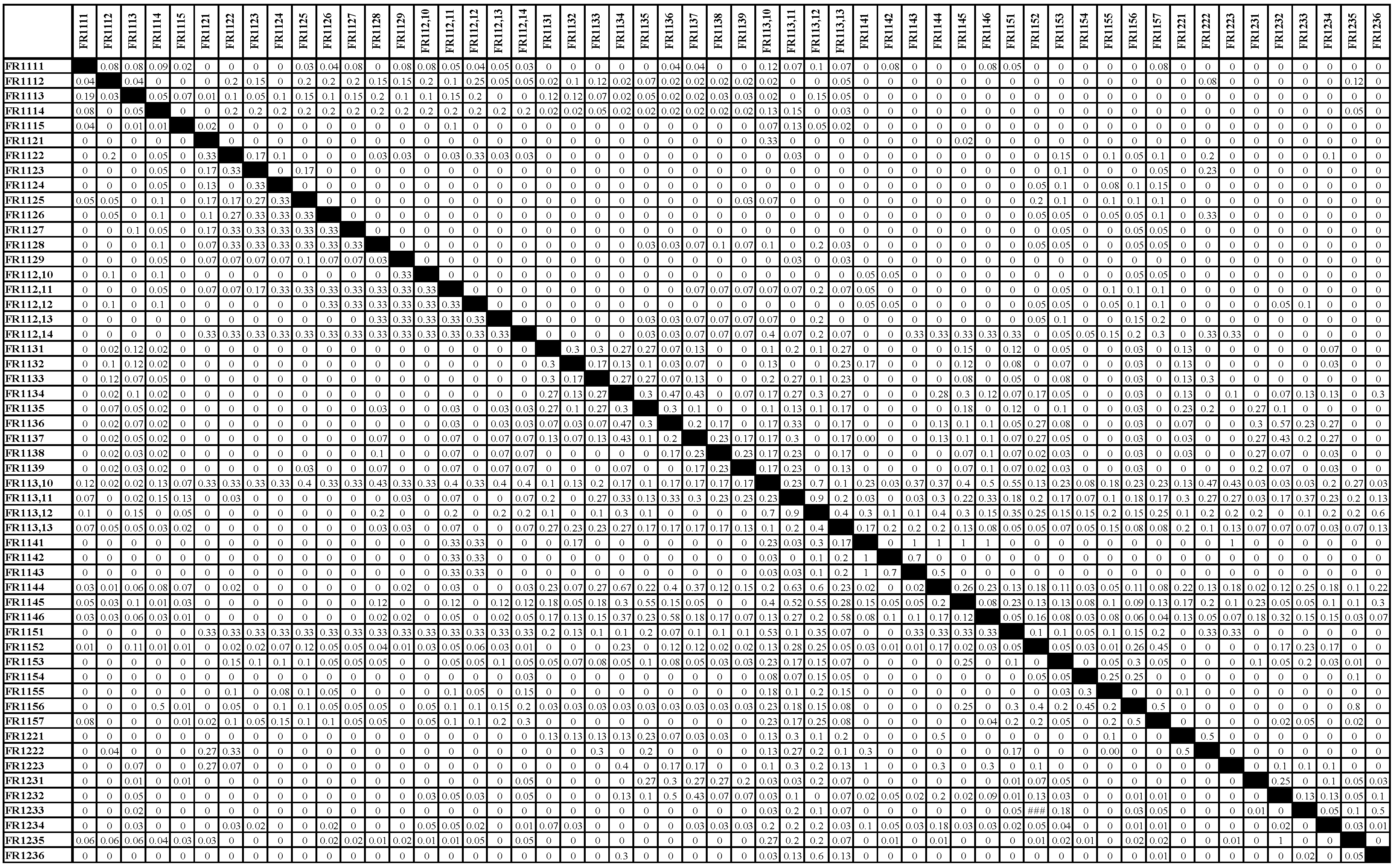

4.2. Originate the Functional Architecture of the SOI in DSM Representation.

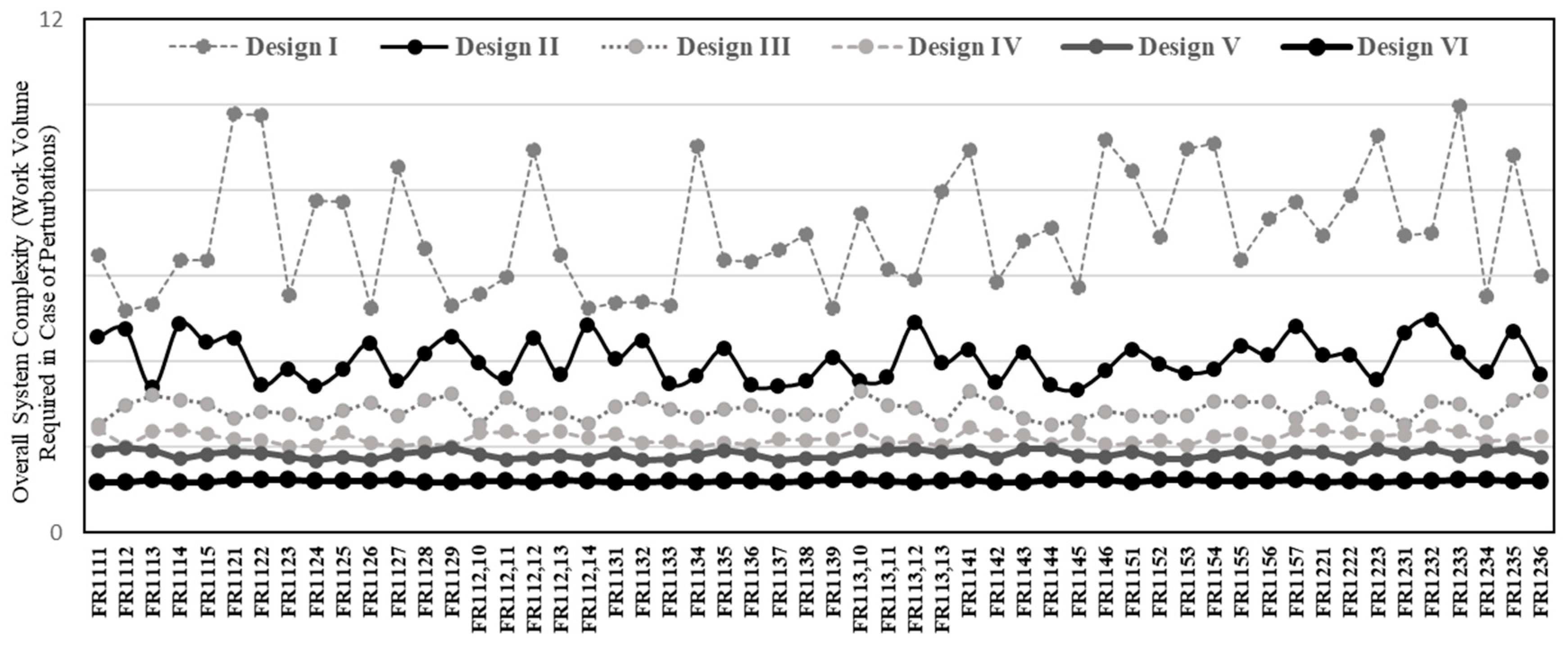

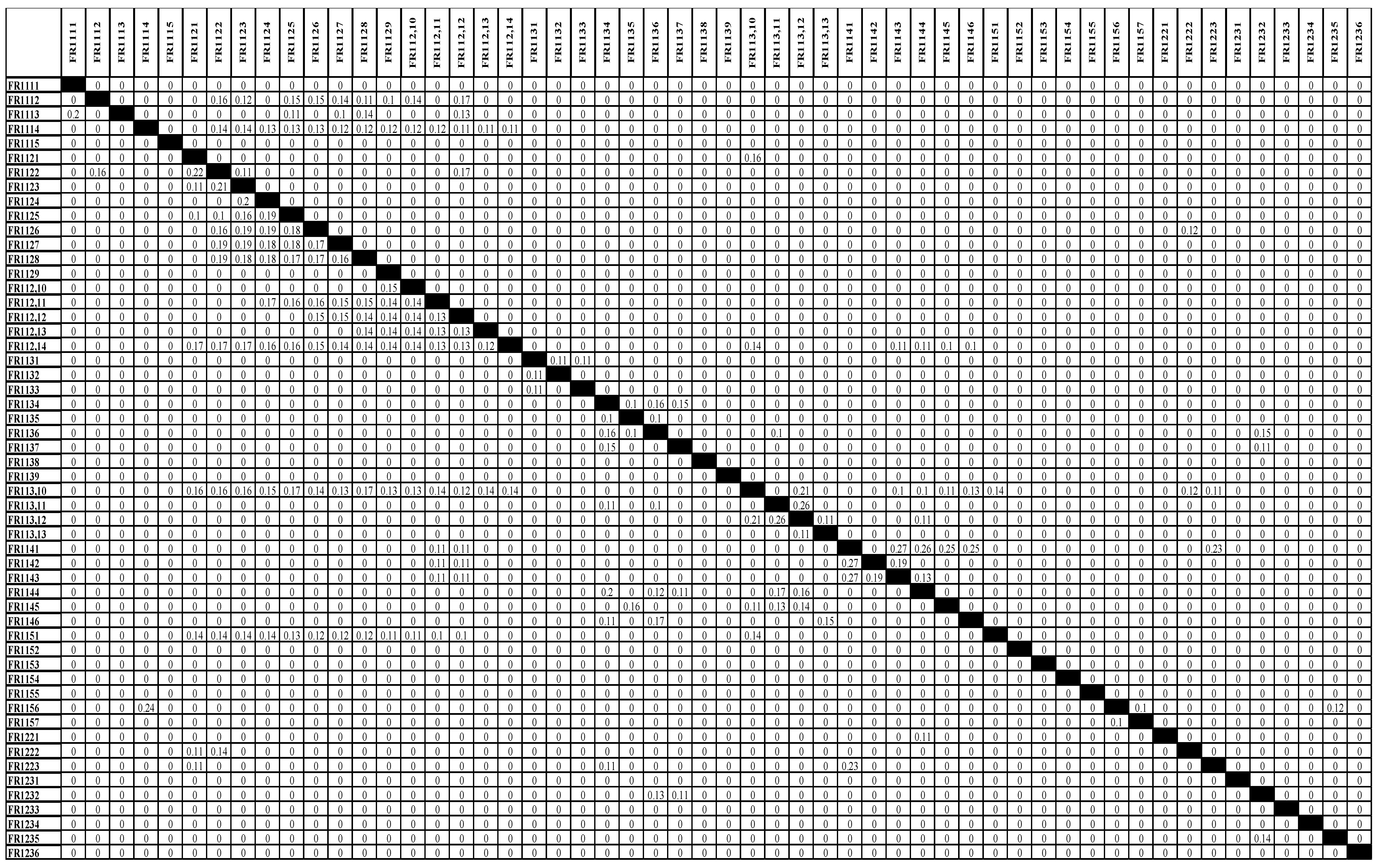

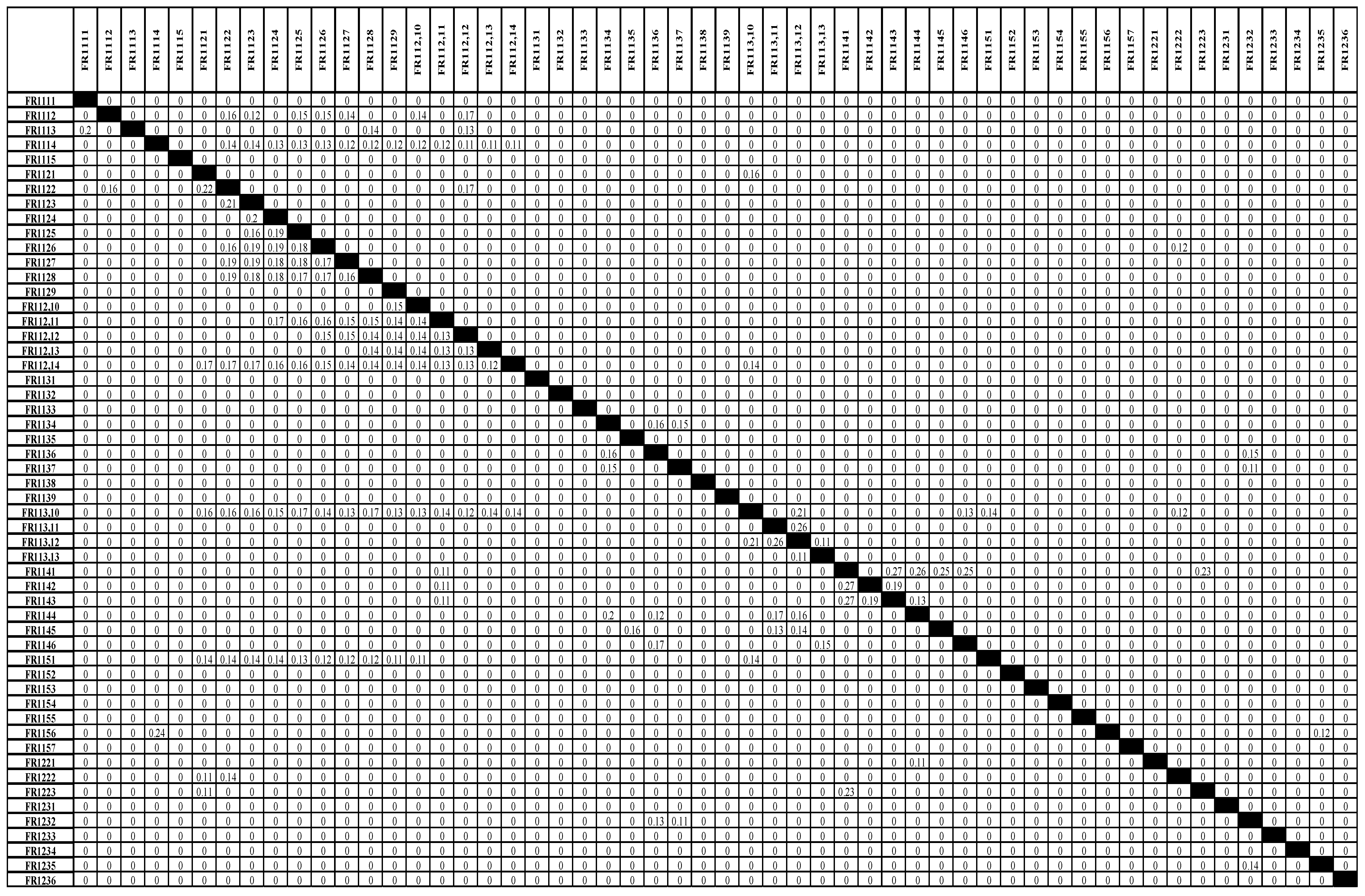

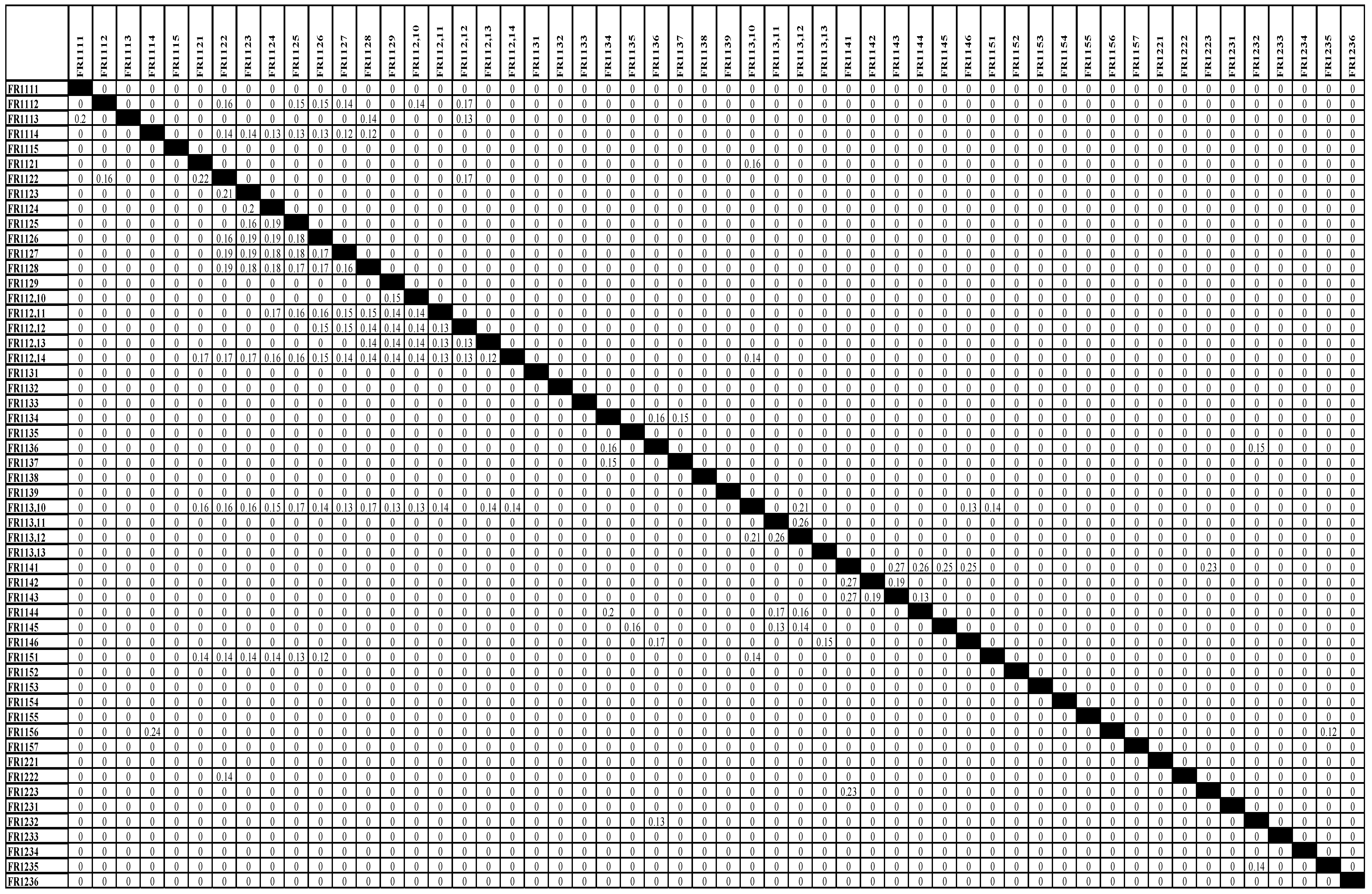

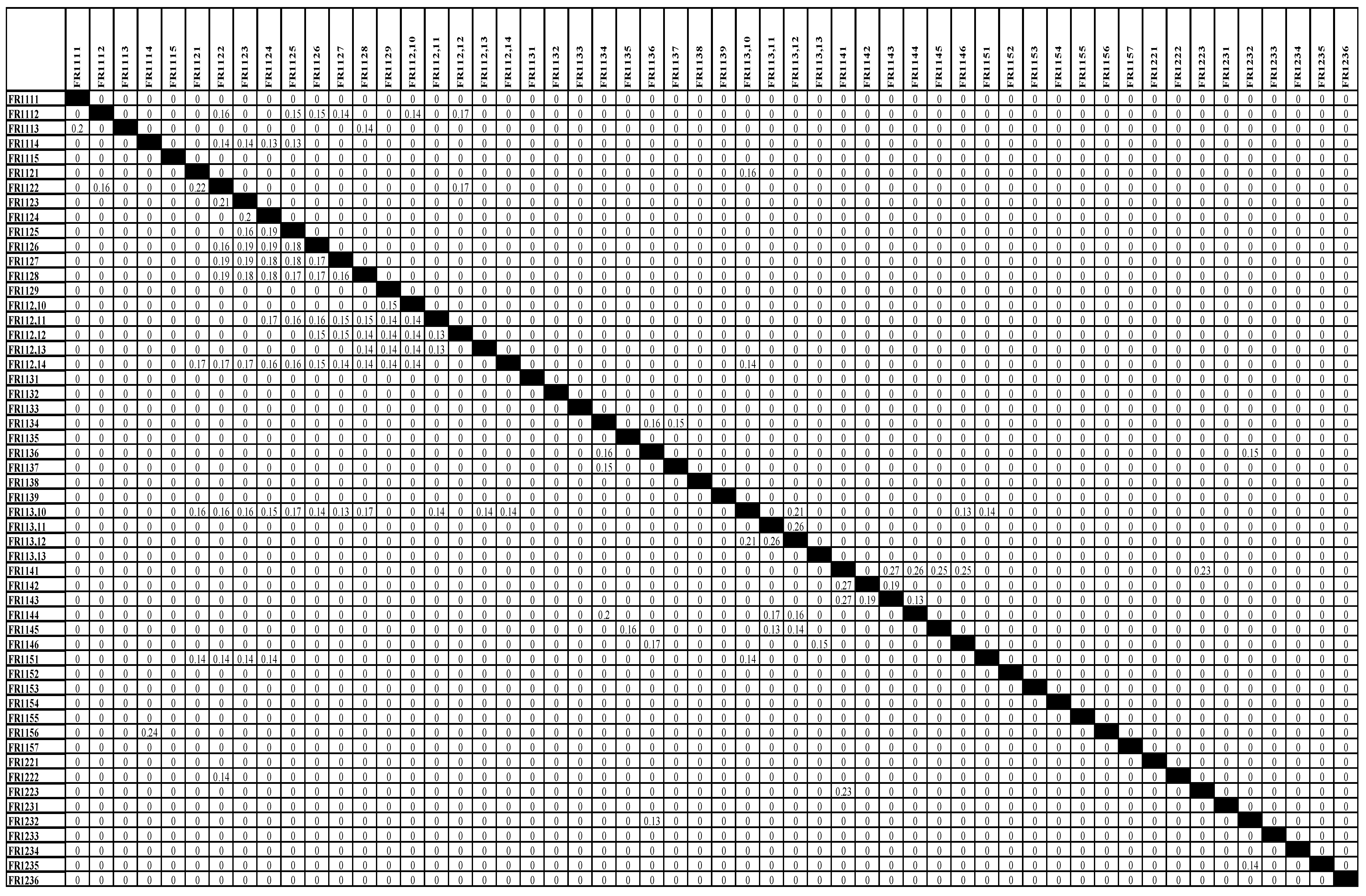

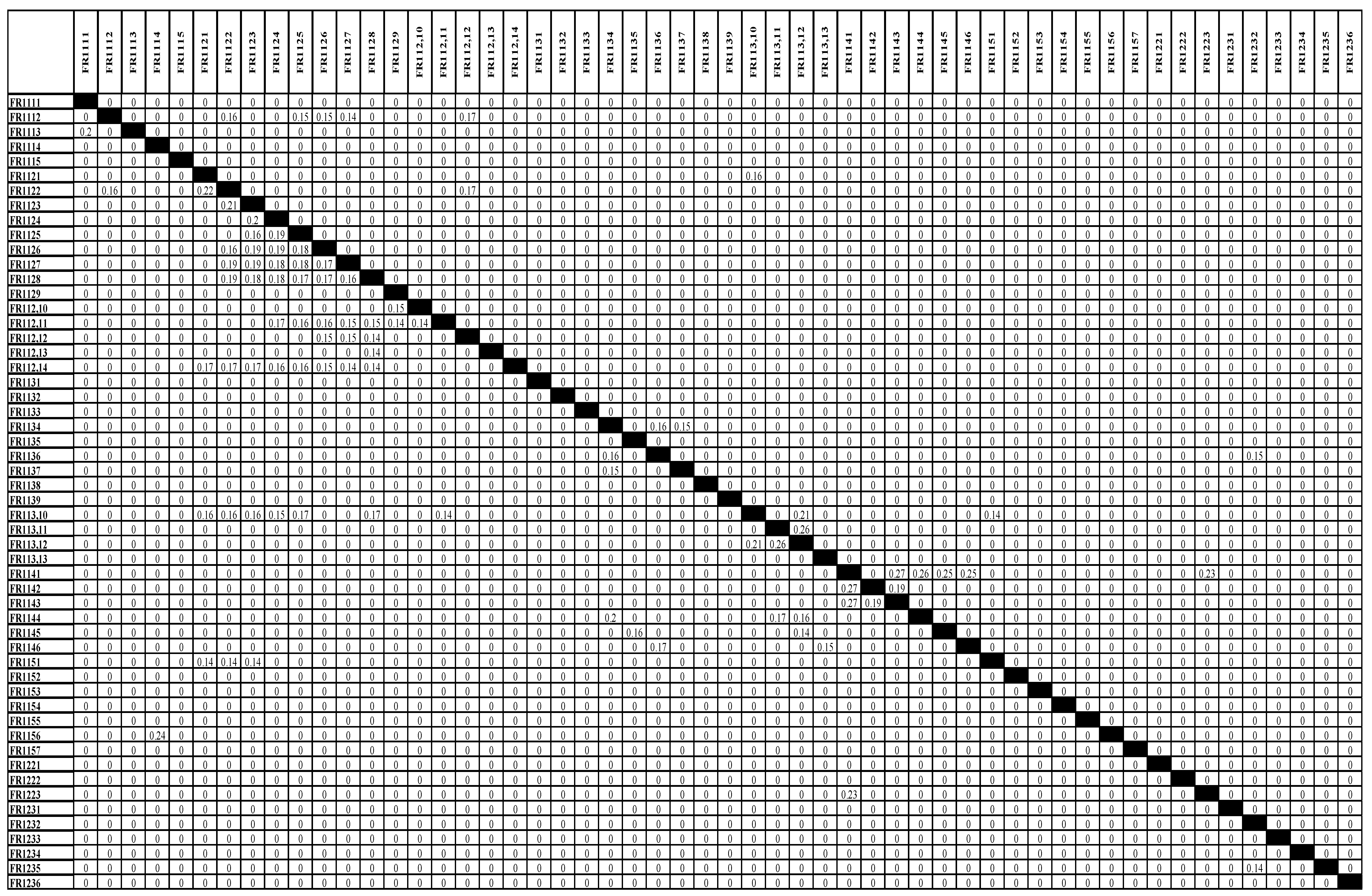

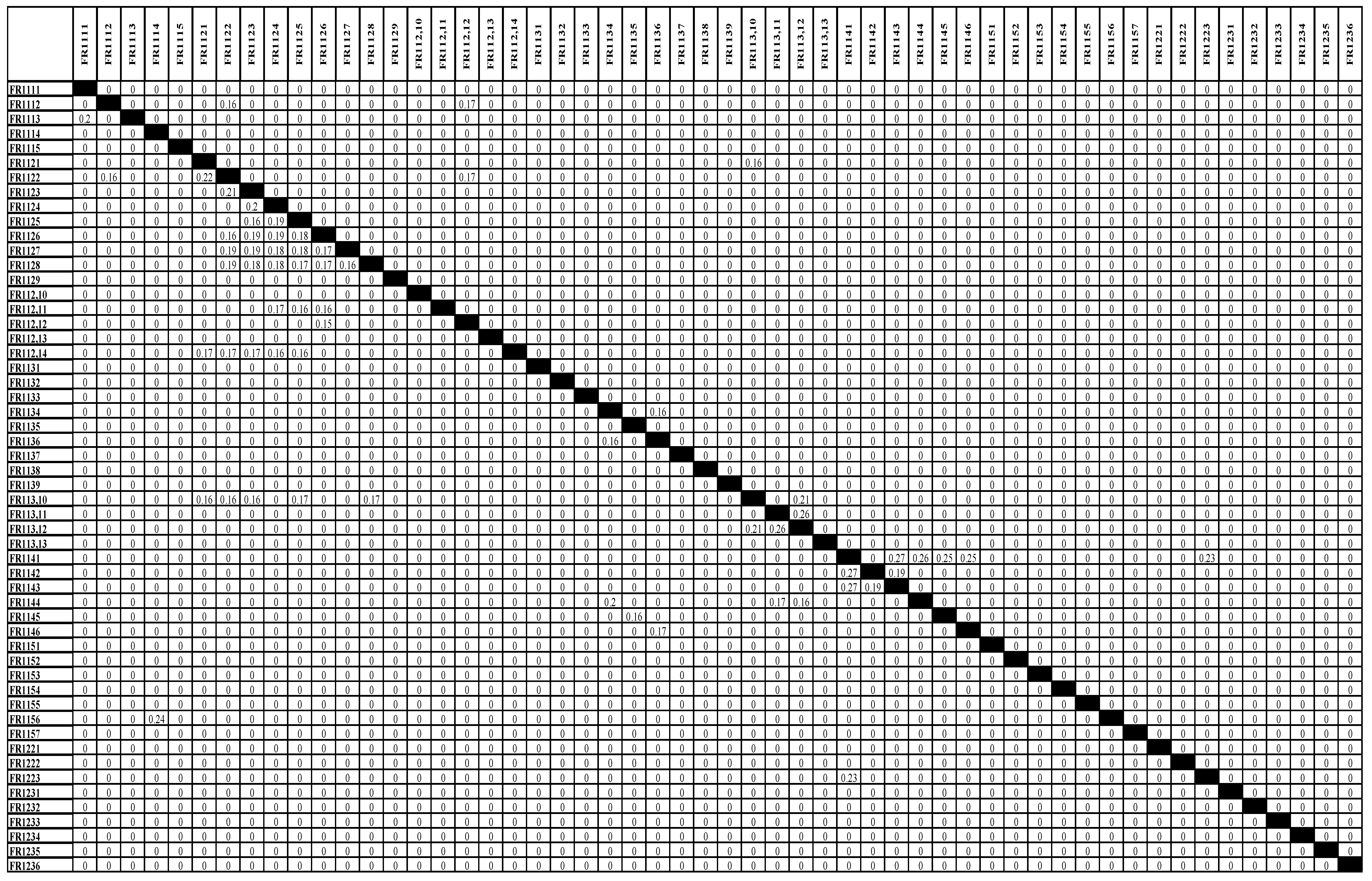

Following steps 3-6 of the method, the DSM tool portrays the functional architecture of the system of interest (SOI). Exhibit 9 shows the original architecture design. Positive values above the diagonal in the original DSM signify substantial coupling, suggesting changes in one element affect others. To curtail change propagation, a beneficial solution called 'modularization' is suggested.

Exhibit 9.

Displaying the initial SOI design using a Numerical Design Structure Matrix

Exhibit 9.

Displaying the initial SOI design using a Numerical Design Structure Matrix

4.3. Significance of Each System Element within the Functional Architecture of the SOI

4.3.1. Initial Significance of Each System Element

Each SOI element's significance is assessed by 'C1' (system architecture dependency) and 'C2' (element's info dependency on architecture). 'C1' gauges system's reliance on an element, while 'C2' measures element's info contribution and input from the system.

For insights into element significance, percentage average dependencies are calculated from the original Numerical Design Structure Matrix (NDSM) of the architecture. Exhibits 10 and 11 display this, providing a comprehensive view of individual element importance and role in the SOI;

Exhibit 10.

Percentage of information provided by each system element for the entire system (NDSM

rows).

Exhibit 10.

Percentage of information provided by each system element for the entire system (NDSM

rows).

| Code |

Percentage (%) |

Code |

Percentage (%) |

Code |

Percentage (%) |

| FR1121

|

0.57 |

FR1231

|

1.36 |

FR1157

|

1.87 |

| FR1115

|

0.6 |

FR1138

|

1.38 |

FR1152

|

1.9 |

| FR1129

|

0.69 |

FR1235

|

1.38 |

FR112,11

|

1.96 |

| FR112, 10

|

0.73 |

FR1113

|

1.44 |

FR1223

|

2.04 |

| FR1124

|

0.83 |

FR1112

|

1.52 |

FR1136

|

2.25 |

| FR1154

|

0.87 |

FR1142

|

1.55 |

FR1137

|

2.26 |

| FR1123

|

0.88 |

FR1131

|

1.55 |

FR1146

|

2.44 |

| FR1236

|

0.96 |

FR112,13

|

1.55 |

FR1134

|

2.49 |

| FR1233

|

0.99 |

FR1232

|

1.56 |

FR113,13

|

2.64 |

| FR1111

|

1.04 |

FR1221

|

1.56 |

FR1156

|

2.75 |

| FR1234

|

1.11 |

FR112,12

|

1.59 |

FR1145

|

2.87 |

| FR1155

|

1.12 |

FR1222

|

1.6 |

FR1144

|

3.11 |

| FR1125

|

1.19 |

FR1133

|

1.64 |

FR1141

|

3.17 |

| FR1139

|

1.25 |

FR1128

|

1.68 |

FR113,11

|

3.72 |

| FR1132

|

1.27 |

FR1153

|

1.74 |

FR113,12

|

3.92 |

| FR1122

|

1.29 |

FR1143

|

1.77 |

FR112,14

|

3.94 |

| FR1127

|

1.31 |

FR1114

|

1.79 |

FR1151

|

4.34 |

| FR1126

|

1.32 |

FR1135

|

1.82 |

FR113,10

|

5.85 |

Exhibit 11.

Percentage of information input received by each system element from the entire system

(NDSM columns).

Exhibit 11.

Percentage of information input received by each system element from the entire system

(NDSM columns).

| Code |

Percentage (%) |

Code |

Percentage (%) |

Code |

Percentage (%) |

| FR1111

|

0.85 |

FR112,14

|

1.56 |

FR1145

|

2.13 |

| FR1112

|

0.94 |

FR1131

|

1.77 |

FR1146

|

1.76 |

| FR1113

|

1.13 |

FR1132

|

1.35 |

FR1151

|

1.82 |

| FR1114

|

1.3 |

FR1133

|

1.88 |

FR1152

|

1.84 |

| FR1115

|

0.63 |

FR1134

|

2.83 |

FR1153

|

1.72 |

| FR1121

|

1.62 |

FR1135

|

2.18 |

FR1154

|

0.99 |

| FR1122

|

2.08 |

FR1136

|

2.36 |

FR1155

|

1.42 |

| FR1123

|

1.92 |

FR1137

|

2.22 |

FR1156

|

1.98 |

| FR1124

|

1.94 |

FR1138

|

1.44 |

FR1157

|

1.97 |

| FR1125

|

2.01 |

FR1139

|

1.28 |

FR1221

|

1.57 |

| FR1126

|

1.79 |

FR113,10

|

3.53 |

FR1222

|

2.07 |

| FR1127

|

1.64 |

FR113,11

|

3.83 |

FR1223

|

1.74 |

| FR1128

|

1.9 |

FR113,12

|

4.13 |

FR1231

|

1.33 |

| FR1129

|

1.68 |

FR113,13

|

2.93 |

FR1232

|

1.97 |

| FR112,10

|

1.59 |

FR1141

|

2.41 |

FR1233

|

1.43 |

| FR112,11

|

2.38 |

FR1142

|

1.04 |

FR1234

|

1.51 |

| FR112,12

|

2.01 |

FR1143

|

1.8 |

FR1235

|

1.4 |

| FR112,13

|

1.46 |

FR1144

|

2.51 |

FR1236

|

1.43 |

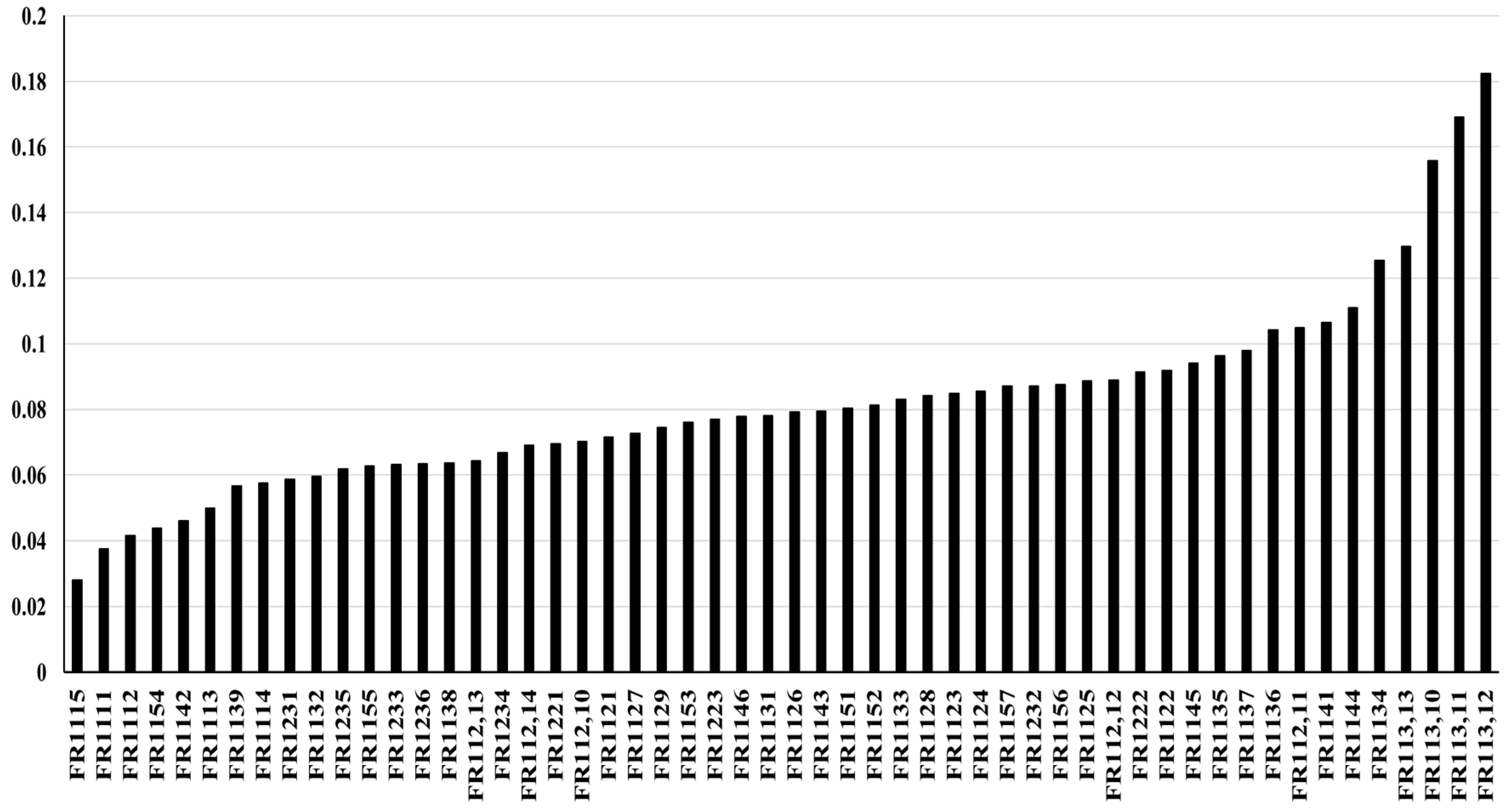

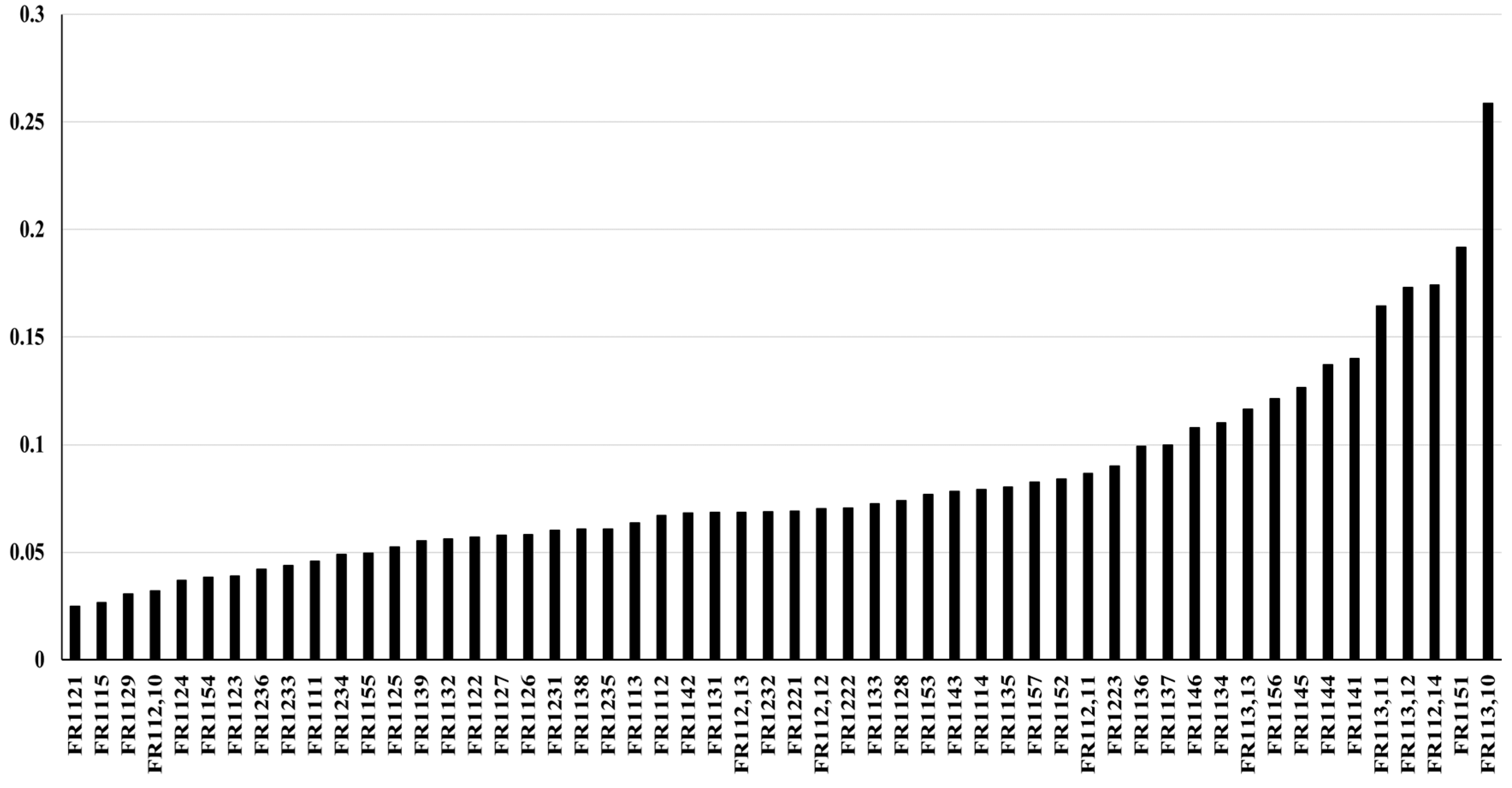

(NDSM)Exhibits 12 and 13 are included to provide a clearer visual representation of

the information presented in Tables 10 and 11, respectively;

Exhibit 12.

Prioritization of the proportion of information contribution from each system element to

the entire SOI (NDSM rows).

Exhibit 12.

Prioritization of the proportion of information contribution from each system element to

the entire SOI (NDSM rows).

Exhibit 13.

Prioritization of the percentage of information input received by each system element from

the entire SOI (NDSM columns).

Exhibit 13.

Prioritization of the percentage of information input received by each system element from

the entire SOI (NDSM columns).

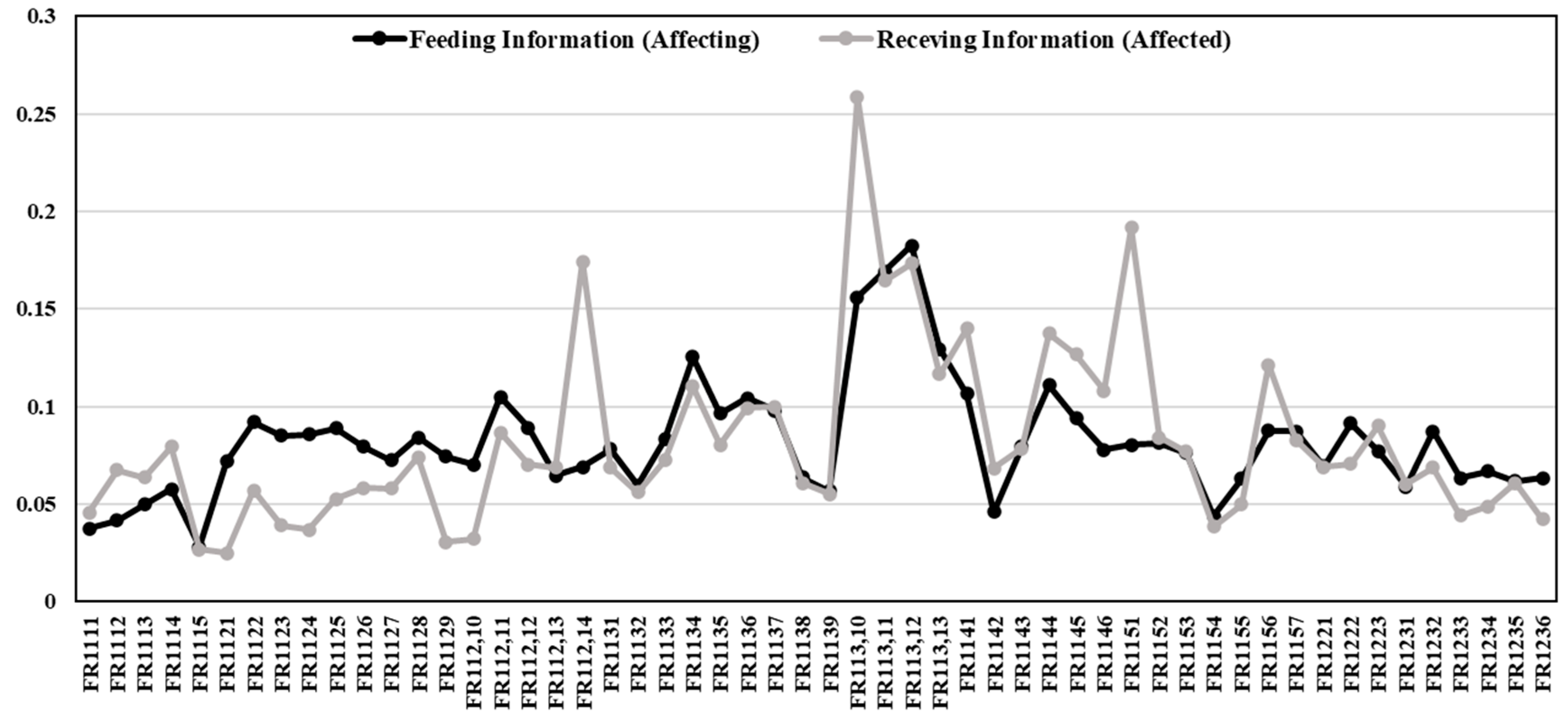

Furthermore, Exhibit 14 offers a comparison between the 'percentage of information feed that each system element can provide' and the 'percentage of information inputs that each system element receives' for/from the entire SOI;

Exhibit 14.

Comparing the information contribution and input percentages for each system element

within the entire system.

Exhibit 14.

Comparing the information contribution and input percentages for each system element

within the entire system.

As observed in the aforementioned figures, it is evident that the criteria C1 and C2 for each system element are not identical. For instance, while elements 'FR113,10', 'FR113,11', and 'FR113,12' demonstrate maximal percentage of information feed they can provide for the entire system (i.e., C1), they also receive the highest percentage of information inputs from the entire system (i.e., C2). However, it is essential to avoid potential misinterpretation, as the significance of each process (i.e., each node of the network representing the system architecture of the SOI) should be evaluated based on both criteria concurrently.

To achieve this, the present study utilizes a weighting method known as the 'compound measure,' proposed within this research. The subsequent section will delve into further details about this approach.

4.3.2. Compound Weights of each system element

To establish a singular weight for each element, two criteria, namely 'C1' and 'C2' are introduced with equal values (i.e., WC1 = 0.5, WC2 = 0.5). Subsequently, two Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) weighting methods, 'SAW' and 'TOPSIS,' are utilized. The resulting weights obtained through these methods are collectively referred to as 'Compound Weights' in this study.

Exhibit 15 displays the final compound weights of each element within the SOI, based on the outcomes derived from the SAW and TOPSIS methods.

Exhibit 15.

Compound weight of each element of the SOI.

Exhibit 15.

Compound weight of each element of the SOI.

| |

SAW |

TOPSIS |

FRs |

SAW |

TOPSIS |

| FR1111 |

0.009 |

0.005 |

FR1139 |

0.013 |

0.010 |

| FR1112 |

0.012 |

0.010 |

FR113,10 |

0.045 |

0.059 |

| FR1113 |

0.013 |

0.010 |

FR113,11 |

0.038 |

0.044 |

| FR1114 |

0.015 |

0.014 |

FR113,12 |

0.040 |

0.047 |

| FR1115 |

0.006 |

0.000 |

FR113,13 |

0.028 |

0.031 |

| FR1121 |

0.012 |

0.010 |

FR1141 |

0.027 |

0.032 |

| FR1122 |

0.018 |

0.016 |

FR1142 |

0.013 |

0.011 |

| FR1123 |

0.015 |

0.013 |

FR1143 |

0.018 |

0.017 |

| FR1124 |

0.015 |

0.013 |

FR1144 |

0.028 |

0.032 |

| FR1125 |

0.017 |

0.015 |

FR1145 |

0.024 |

0.028 |

| FR1126 |

0.016 |

0.014 |

FR1146 |

0.020 |

0.022 |

| FR1127 |

0.015 |

0.013 |

FR1151 |

0.029 |

0.037 |

| FR1128 |

0.018 |

0.017 |

FR1152 |

0.019 |

0.019 |

| FR1129 |

0.013 |

0.011 |

FR1153 |

0.017 |

0.017 |

| FR112,10 |

0.012 |

0.010 |

FR1154 |

0.009 |

0.005 |

| FR112,11 |

0.022 |

0.023 |

FR1155 |

0.013 |

0.010 |

| FR112,12 |

0.018 |

0.018 |

FR1156 |

0.023 |

0.026 |

| FR112,13 |

0.015 |

0.013 |

FR1157 |

0.019 |

0.019 |

| FR112,14 |

0.025 |

0.033 |

FR1221 |

0.016 |

0.014 |

| FR1131 |

0.017 |

0.015 |

FR1222 |

0.019 |

0.018 |

| FR1132 |

0.013 |

0.010 |

FR1223 |

0.019 |

0.019 |

| FR1133 |

0.018 |

0.017 |

FR1231 |

0.013 |

0.011 |

| FR1134 |

0.027 |

0.030 |

FR1232 |

0.018 |

0.017 |

| FR1135 |

0.020 |

0.020 |

FR1233 |

0.013 |

0.009 |

| FR1136 |

0.023 |

0.025 |

FR1234 |

0.013 |

0.011 |

| FR1137 |

0.022 |

0.024 |

FR1235 |

0.014 |

0.012 |

| FR1138 |

0.014 |

0.012 |

FR1236 |

0.012 |

0.009 |

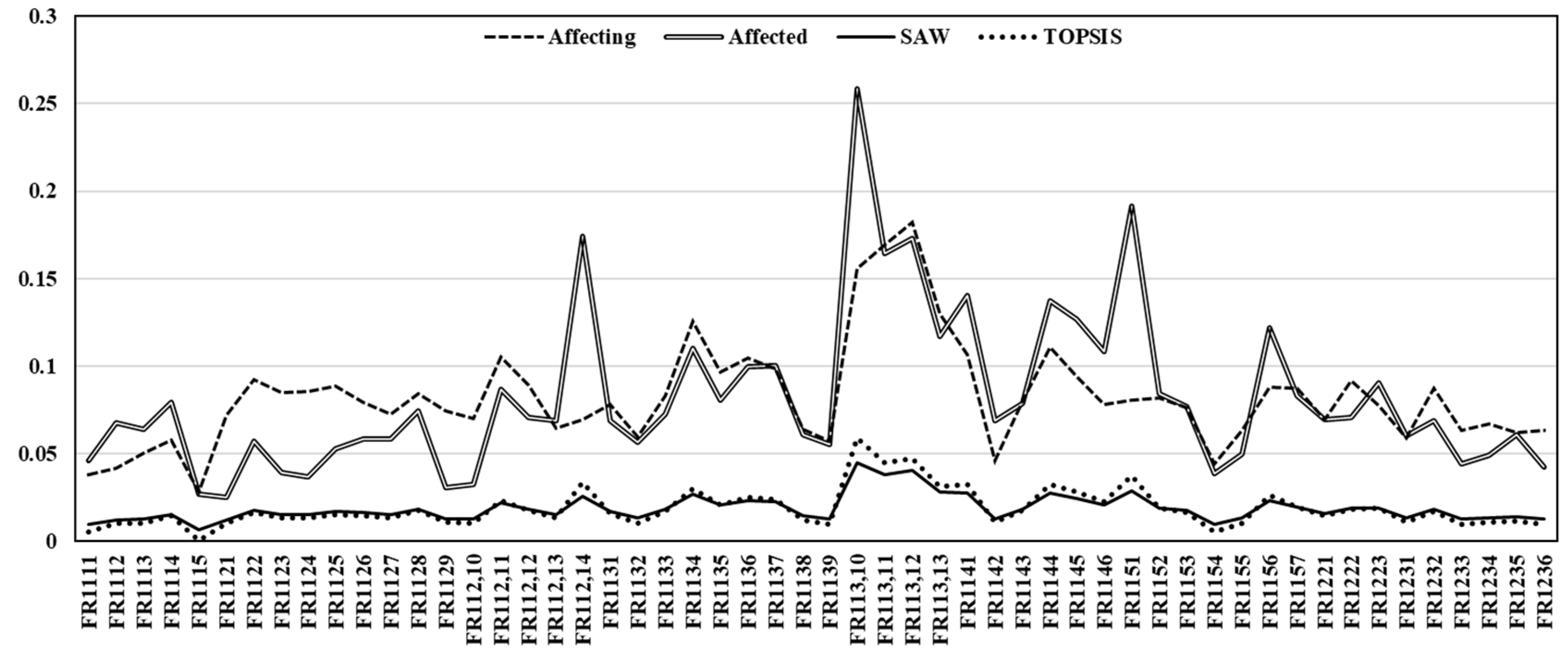

Exhibit 16 presents a comparison of the compound weight of each element obtained from both the TOPSIS method and the SAW method, alongside the weights originally computed (i.e., weights obtained from C1 and C2 only).

Exhibit 16.

Comparing the compound weights of each element with their original individual weights.

Exhibit 16.

Comparing the compound weights of each element with their original individual weights.

As the figure illustrates, there are considerable differences between the original weights and the weights obtained from applying the MCDM methods. However, the latter weights (i.e., weights given by the SAW and TOPSIS methods) are nearly similar, while also being more reasonable and acceptable.

Given the considerable similarity between the results obtained from the SAW and TOPSIS methods, for the sake of simplicity and without losing generality, the weights given by the TOPSIS method are used to continue the analyses. Exhibit 17 presents the updated prioritization of the elements based on the compound weights derived from the TOPSIS method;

Exhibit 17.

Prioritization of elements according to their compound weights determined by the TOPSIS method.

Exhibit 17.

Prioritization of elements according to their compound weights determined by the TOPSIS method.

| System Element |

Priority |

Compound Weight |

System Element |

Priority |

Compound Weight |

| FR113,10

|

29 |

0.0449 |

FR1131

|

20 |

0.0168 |

| FR113,12

|

31 |

0.0404 |

FR1125

|

10 |

0.0167 |

| FR113,11

|

30 |

0.0378 |

FR1126

|

11 |

0.0160 |

| FR1151

|

39 |

0.0286 |

FR1221

|

46 |

0.0157 |

| FR113,13

|

32 |

0.0281 |

FR1127

|

12 |

0.0151 |

| FR1144

|

36 |

0.0276 |

FR1114

|

4 |

0.0151 |

| FR1141

|

33 |

0.0272 |

FR112,13

|

18 |

0.0150 |

| FR1134

|

23 |

0.0269 |

FR1123

|

8 |

0.0149 |

| FR112,14

|

19 |

0.0255 |

FR1124

|

9 |

0.0148 |

| FR1145

|

37 |

0.0243 |

FR1138

|

27 |

0.0141 |

| FR1136

|

25 |

0.0231 |

FR1235

|

53 |

0.0139 |

| FR1156

|

44 |

0.0230 |

FR1234

|

52 |

0.0135 |

| FR1137

|

26 |

0.0224 |

FR1231

|

49 |

0.0134 |

| FR112,11

|

16 |

0.0220 |

FR1132

|

21 |

0.0132 |

| FR1146

|

38 |

0.0204 |

FR1155

|

43 |

0.0130 |

| FR1135

|