1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer type globally, and the second most common cause of cancer death [

1]. The five-year recurrence rate in a Swedish population-based cohort from 2018 was 5% in stage I, 12% in stage II and 33% in stage III colon cancer [

2]. It is important to assess the risk of recurrent disease, and to promptly observe signs of recurrence, as well as risks for toxicity and expected benefits of adjuvant treatment in deciding when to recommend chemotherapy and what type of chemotherapy. In current guidelines, adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for patients with stage II colon cancer with high-risk criteria, and for all with stage III. Currently, the risk of recurrence is assessed by the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, microsatellite instability/mismatch repair (MSI/MMR) status, number of lymph nodes, and additional clinicopathological characteristics, such as perineural, vascular or lymphatic invasion, histological grade and subtype, tumor obstruction and levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) [

3]. Upcoming biomarkers can be of benefit for assessing risks of recurrence, including the Immunoscore

®, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and gene signatures [

4,

5]. The Immunoscore

® test was predictive of time to recurrence in a large prospective cohort of patients with TNM stages I-III, although its potential role in predicting benefits from chemotherapy in stage II colon cancer patients remains to be assessed [

4]. Postoperative measurement of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) for tumor-specific mutations is promising for identifying individuals with high risk of recurrence [

5].

The phenomenon that tumors shed material to the blood stream was discovered a few decades ago [

6,

7]. This knowledge has given rise to the field of liquid biopsy, i.e., the opportunity to investigate disease anywhere in the body by analyzing markers released to the blood stream, such as circulating tumor cells, ctDNA, exosomes and tumor-educated platelets [

8,

9]. One of the most promising classes of liquid biopsy biomarkers for monitoring solid tumors is ctDNA, the levels of which strongly correlates with tumor volume and with liver metastasis [

10]. The utility of ctDNA to predict recurrence of CRC is currently being studied in several clinical trials [

11,

12]. In a prospective study of 230 patients with resected stage II colon cancer, those who were ctDNA-positive postoperatively had a higher risk of recurrence than those with negative ctDNA. This was true whether or not patients received adjuvant chemotherapy [

5]. By using ctDNA for treatment guidance in stage II colon cancer, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy was reduced without compromising recurrence-free survival [

13]. In stage III colon cancer patients, ctDNA detected postoperatively was associated with shorter recurrence-free survival. However, among stage III postoperative patients, only 42% of recurrences were detected using ctDNA analysis [

14]. Most patients diagnosed with metastatic CRC have detectable ctDNA [

15]. In a prospective study, presence of ctDNA in post treatment samples from 35 metastatic CRC patients was associated with recurrence [

16]. Detection of measurable residual disease (MRD) via ctDNA after curative surgery in earlier stages requires more sensitive technology, compared to monitoring of metastatic disease due to the generally low amount of ctDNA in plasma samples [

17].

There is considerable shedding of tumor fragments in CRC, which makes the disease suitable for liquid biopsy [

18]. Considering that the ctDNA/cfDNA ratio can be much lower than 1%, sensitive detection methods are warranted. Analyses of ctDNA can be conducted with both PCR-based techniques and through next generation sequencing (NGS). Although NGS provides a potential to retain whole genome sequencing data, in clinical practice it is usually limited to panels of hotspots of tens up to a few hundred genes. PCR-based methods can provide a higher level of sensitivity (mutant allele frequencies [MAF] for detection ≤0.01%), but on the downside the number of detectable mutations is limited. The superRCA is an ultrasensitive method for detecting DNA sequence variants from malignant cells in up to a 100,000-fold excess of DNA from normal cells in peripheral blood or bone marrow. This method was previously used to monitor patients with leukemia in order to detect early recurrence [

19]. When comparing superRCA to clinically used NGS and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assays, superRCA is capable of detecting more mutations and lower frequencies than ddPCR, and the method is less costly and has a shorter turn-around time than NGS [

19].

Here, we have evaluated the performance of a superRCA assay for detecting recurrence of solid tumors by analyzing cfDNA from CRC patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tumor Tissue and Plasma Samples

Tumor tissue and plasma samples were obtained through the Uppsala-Umeå Comprehensive Cancer Consortium (U-CAN) project (

www.u-can.uu.se) [

20]. The study included 74 plasma samples from 25 CRC patients from the population-based, prospective longitudinal biobank U-CAN (

Table 1) [

20]. Tumor hotspot mutations in

BRAF, KRAS, NRAS and

PIK3CA were derived from molecular pathology reports in the patients´ medical records. Control genomic DNA (gDNA) was purified from normal tissue, and gDNA was extracted from primary tumor tissue after surgery for samples from 20 of these patients. A volume of 1.8 mL plasma isolated from blood drawn at the time of diagnosis and at two later time points were obtained from all patients, except for patient UU035 where only two samples in total were included. Postoperative plasma samples (collected week six to 13 after surgery) were available from seven patients. UU004 did not have surgery, so for this patient the sample collected week six to 13 from diagnosis was used instead, but included in the postoperative samples. The rest of the samples were collected during the course of the disease, with a time frame of 16 weeks up to four years (

Table 2).

2.2. DNA Preparation

Control tumor gDNA was extracted from fresh-frozen sections using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany), while matched normal gDNA was extracted from blood samples using the Nucleospin 96 Blood core kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). Control normal and tumor gDNA samples were available as purified gDNA with high concentrations (7.8-40 ng/μL) in 30-100 μL aliquots. Plasma samples were received as 8 aliquots of 220 μL each. The 8 aliquots from each plasma sample were pooled and the cfDNA was purified using the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit (Qiagen cat.55114) and a QIAvac 24 Plus (Qiagen cat.19413) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and eluted in a total volume of 30 μL elution buffer. The cfDNA concentrations were determined using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA).

2.3. superRCA Assay Principle

The MAF of the samples were determined with the multiplex CRC superRCA Mutation Kit (Rarity Bioscience, Sweden) using a CytoFLEX flow-cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, USA) for read-out. The multiplex CRC superRCA Mutation Detection assay is based on the original superRCA protocol [

19]. superRCA is a single tube, targeted multiplex genotyping assay that combines two rounds of rolling circle amplification (RCA) with sequence specific genotyping padlock probes. First, the purified DNA sample undergoes a limited number of cycles of multiplex PCR to enrich sequences of interest. Next, the 3´and 5´ ends of one of the strands of amplification products are allowed to hybridize next to each other to a complementary oligonucleotide, allowing the ends of the strands to be joined by ligation to form circular DNA molecules. The circular strands then template RCA reactions that yield, for each starting DNA circle, one linear single-stranded concatemer with several hundred repeats of the original amplicon. Next, genotyping padlock probes, specific for the mutant or wild-type sequences, are introduced to interrogate the repeated targets in individual RCA products. The assay is tolerant for the occasional mistyping by the padlock probes, since according to the majority vote principle, the most abundant signal coming from each genotyped RCA product accurately reflects the true genotype of that starting DNA circle. The circularized genotyping padlock products, linked to RCA products, are then in turn replicated in secondary RCA reactions. The products of the secondary RCA reactions remain anchored to the first RCA products by hybridization. Each of the starting RCA products result in individual brightly fluorescent clusters of DNA by hybridizing fluorescent oligonucleotides, differentially labeled for detecting products of mutant or wild-type sequences.

Each superRCA reaction yields ~106 products that can be distinguished and counted using standard flow cytometry. The highly accurate genotyping of the repeated sequence of the first RCA products, along with the large number of superRCA products that are counted, together, account for the very sensitive and precise detection of mutant sequences – suitable for detecting MRD in patient plasma samples.

2.4. Pre-Amplification

The 10 DNA amplicons encompassing 44 mutations covered by the multiplex CRC superRCA Mutation Kit (Rarity Bioscience, Sweden) (

Table S1) were enriched in the samples by multiplex PCR using the CRC Pre-amplification buffer, supplemented with Pre-amp Enzyme 1 and 2 supplied with the kit. Pre-amplification reactions were performed in 0.2 mL 96 Well PCR plates (Nest Biotechnology, China) in a final volume of 50 μL, using a SimpliAmp Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The program started with a 10 min incubation at 37 °C, followed by 30 s denaturation at 98 °C before cycling between 30 s at 98 °C and 120 s at 62 °C. The program ended with a 5 min extension at 72 °C.

The number of cycles were adjusted according to the total DNA input in the PCR sample, and also the integrity of the DNA as cfDNA in plasma was fragmented. Plasma samples with >25 ng total cfDNA were amplified in 14 cycles, while 16 PCR cycles were used to amplify plasma samples with <25 ng total cfDNA. The whole 30 μL DNA sample from plasma cfDNA purification was used in the final superRCA analysis, except for the UU035 follow-up sample where 4.4 μL, corresponding to 33 ng DNA, was used. A total of 33 ng from each of the control gDNA samples with identified hotspot mutations was analyzed. The assay was performed according to manufacturer´s instructions (Rarity Bioscience, Sweden).

2.5. superRCA Reactions

All superRCA reactions were performed in a full-skirted 0.1 mL 96 Well PCR Plate (Nest Biotechnology, China) using an automated protocol on an OT-2 Pipetting Robot fitted with a GEN2 Thermocycler Module (Opentrons, USA) using the buffers supplied with the kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, 1.2 μL of the PCR enriched samples were added to 20 μL PCR Clean-Up Buffer, supplemented with 1st Clean-up Enzyme and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Next, 5 μL Clean-Up Buffer supplemented with 2nd Clean-Up Enzyme was added and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min, followed by 55 °C for 5 min. Five μL Ligation Buffer supplemented with DNA ligase was then added and the mixture was incubated at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 55 °C for 15 min. After ligation, 5 μL RCA buffer supplemented with RCA polymerase was added and incubated at 37 °C for 25 min, followed by 60 °C for 10 min. Next, 5 μL of a genotyping solution with the appropriate Genotyping padlock probes were added and incubated at 55 °C for 30 min. This was followed by addition of 5 μL Clean-Up Buffer, supplemented with 3rd Clean-Up Enzyme and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, 75 °C for 15 min. Next, 5 μL RCA buffer supplemented with superRCA polymerase was added and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 25 min. The final superRCA products were labeled by addition of fluorescent hybridization oligonucleotides in 5 μL Labeling buffer and incubated at 45 °C for 15 min.

2.6. Flow Cytometry

The final superRCA reaction products were identified and enumerated using a CytoFLEX flow-cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA). The superRCA products derived from wild-type alleles were labelled with FITC and those derived from mutant variants were labelled with Cy-5. Acquisition was set at 30 μL/min for 75 s. The number of events depended on the amount of input but were in the range 400,000-1,000,000. Negative controls (wild-type control) were included at all times when the assay was performed and positive controls were included when available.

2.7. Ethical Approval

The patients gave written informed consent to donate biopsy and blood samples for research when they were included in the U-CAN cohort. The ethical permit EPN Uppsala 2015-419 regulated the use of the samples and clinical data from the patients in this project.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Cohort and cfDNA Purification

To evaluate the performance of the superRCA assay for recurrence detection, blood samples were collected at diagnosis, postoperatively and/or during follow-up from 25 patients along with tissue samples from 20 of these patients (

Table 3). Most (60%) were below 75 years old, and male (60%). Three patients (12%) were in stage I, five (20%) in stage II, 15 (60%) in stage III, and two (8%) were in stage IV. The majority had a primary tumor located in the colon (72%). Both patients that experienced clinical relapse after treatment or continued recurrence-free were included.

The study included gDNA and plasma samples both from patients with clinically identified and unknown genetic tumor markers (

Table 1). Control gDNA isolated from tumor and matching normal tissue biopsies were obtained from 20 patients. Fifteen of the gDNA patient samples had one or two identified hotspot mutations in the four routinely analyzed genes, while the remaining five had wild-type hotspot backgrounds. In addition, plasma samples were collected at the time of diagnosis and at later time points from these 20 patients and from five additional patients (

Table 2 and

Figure S1). The five additional patients included four with identified hotspot mutations and one wild-type (

Table 1). In total, 12 unique hotspot mutations in four different genes (

KRAS,

PIK3CA,

BRAF, and

NRAS) were included in six different amplicons that were amplified jointly (KRAS146, KRAS12, PIK3CA545, PIK3CA1047, BRAF600 and NRAS12). Fifteen patients had a single hotspot mutation among the targeted positions, four had two hotspot mutations, and six had none in the target genes (

Table 1).

As expected, the amount of cfDNA varied in the different plasma samples from a total of 7.13 ng cfDNA recovered from the UU019 follow-up sample to 222.9 ng cfDNA recovered from the UU035 follow-up sample. The average cfDNA amount recovered was 22.43 ng, 15.91 ng, and 26.62 ng at diagnosis, postoperatively, and during follow-up, respectively (

Table 1 and

Figure S2).

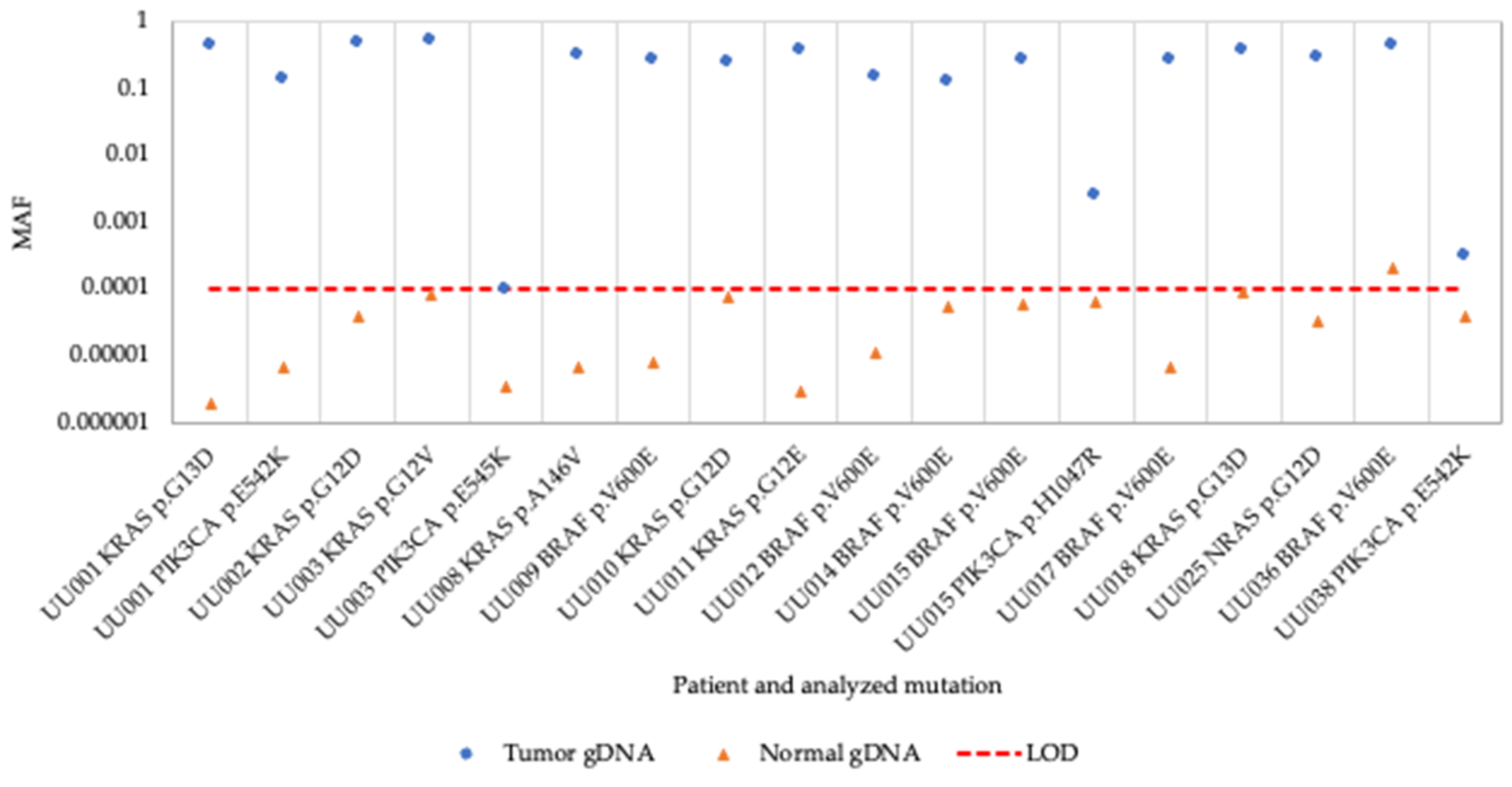

3.2. superRCA Analysis of Samples with Identified Hotspot Mutations

All previously identified hotspot mutations were detected in the tumor biopsy gDNA samples using the superRCA mutation assay although the MAF was low in three biopsies (

Figure 1 and

Table S2). All corresponding control gDNA samples from normal tissue were negative except for a sample from patient UU036 with a

BRAF V600E mutation, where the mutation was detected at a MAF of 0.0002 (0.02% MAF) in the normal control sample. These results demonstrate that the assay efficiently detected different hotspot mutations in the gDNA control samples.

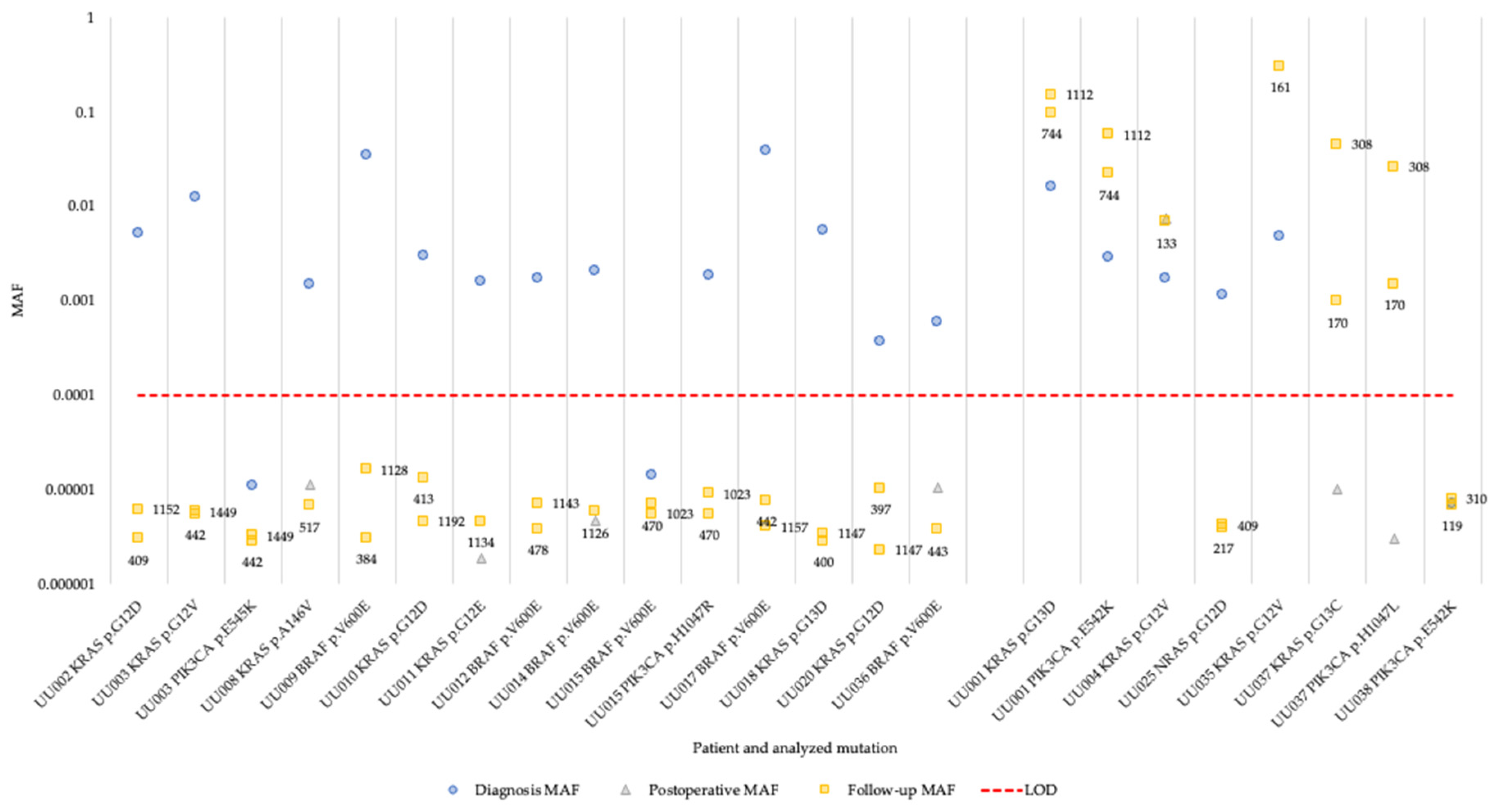

Next, we analyzed the cfDNA isolated from plasma from the 19 patients with identified hotspot mutations. In 17 of the patients (94% of patients with available diagnosis plasma sample), at least one of the hotspot mutations present in the tumor could be detected in cfDNA at the time of diagnosis (

Figure 2 and

Table S3). One of the patients (UU038) had MAF below the detection limit of 0.0001 (0.01% MAF) in plasma collected at diagnosis. In the postoperative samples, one of the patients were positive and had increased MAF for the identified hotspot mutations while the remaining patients showed background levels of mutant alleles in the cfDNA (

Figure 2). This pattern persisted in the follow-up samples where the MAF of the patient positive for the hotspot mutations remained increased. The MAF of three patients (UU001, UU035 and UU037) were increased during follow-up, while measurements for the rest of the patients remained at background levels (

Figure 2). For one patient whose cfDNA sample taken 20 days postoperatively was negative (UU037), both identified hotspot mutations were detected in the cfDNA samples collected during follow-up.

Comparing the plasma cfDNA superRCA results with patient data revealed that the four patients with detectable hotspot mutations in cfDNA after surgery (UU001, UU004, UU035 and UU037) indeed experienced clinical relapse. An additional patient (UU025) also experienced clinical relapse after surgery but the

NRAS p.G12D mutation was not detected in the follow-up plasma samples. It is possible that a tumor cell clone lacking the

NRAS p.G12D mutation was responsible for the relapse in this patient. The recurrent tumor was not genotyped and the malignant cells carrying the

NRAS p.G12D mutation could then be cleared during surgery or adjuvant chemotherapy. Moreover, patient UU038 also experienced clinical relapse but the

PIK3CA p.E542K mutation was not detected in any sample, neither at diagnosis nor at follow-up. The remaining 13 patients exhibiting background levels of hotspot mutations remained recurrence-free after surgery (

Table 1 and

Table 2,

Figure 2 and

Figure S1).

3.3. Multiplex superRCA Analysis of Wild-type Samples

One of the advantages of the superRCA mutation detection assay is the possibility to analyze multiple mutations in limited cfDNA samples. The unbiased, low cycle, multiplex, pre-amplification in the superRCA procedure enriches the relevant DNA sequences in samples without affecting the MAF. Thus, after the pre-amplification, the samples can be divided and analyzed in parallel in the 96 well format for any mutation present in the amplicons included in the panel. Amongst the patients without

RAS,

BRAF and

PIK3CA mutations (i.e., wild-type of these genes), three experienced clinical relapses after surgery (UU005, UU006, and UU007) (

Figure S1). Since the recurrent tumors were not genotyped and the genetic signature thus unknown, we proceeded to analyze cfDNA in the last samples collected from these patients and from patient UU025, discussed above, for all 44 mutations included in the superRCA CRC Mutation assay target panel (

Table S1). The last follow-up sample for patient UU007 was unfortunately lost during cfDNA purification, so instead the earlier follow-up plasma cfDNA was analyzed for this patient. However, the earlier follow-up sample for patient UU007 was collected 750 days prior to recurrent disease. The rationale was that in the relapse patients with wild-type tumors, additional mutations might have been acquired or selected for during treatment. Each of the 44 wild-type genotypes encoded in the 10 different amplicons were analyzed in the samples, but none of the samples were positive for any of the mutations included in the panel (results not shown).

4. Discussion

Operated cancer patients increasingly have their tumors sequenced to identify patient-specific, sometimes actionable mutations. This also provides an opportunity to search for the identified mutations in blood liquid biopsies. Serial analyses of cfDNA have proven helpful in several studies to provide an estimate of the recurrence risk and, if repeated samples are taken, to detect recurrence prior to any clinical or radiological manifestation of relapse [

21,

22]. According to the Swedish national guidelines from 2016 and 2020 for management of CRC patients, computed tomography of the chest and abdomen and measurement of CEA are recommended after one and three years to detect recurrence of radically resected colon cancer [

23]. This internationally low intensity of follow-up is based upon a large multicenter study (COLOFOL) where more intense follow-up did not result in better survival [

24]. However, even if CEA has a sensitivity of less than 70% for detecting recurrence and imaging cannot detect small recurrences early, these follow-up methods are internationally accepted at much higher frequencies. In a recent study, cfDNA investigation could detect recurrences in median 8.7 months before imaging [

25]. In yet another study, analysis of cfDNA revealed recurrence 9.4 months before recurrence was detected by imaging [

22]. Hence, screening for ctDNA appears to offer greater sensitivity for recurrence than CEA and imaging in clinical practice. However, measurement of ctDNA is not yet routine outside highly specialized centers.

The cfDNA analysis can be tumor-informed or tumor-agnostic. Tumor-agnostic approaches for ctDNA detection have been suffering from low sensitivity due to the pre-defined list of targets in the assay aiming for assay robustness and cost effectiveness. The tumor-informed approach has better sensitivity due to the designing of personalized mutation assays, but presupposes mutational analysis of tumor tissue. However, the situation for the tumor-agnostic approach has been improved by adding DNA methylation as epigenetic markers [

26]. Tumor-agnostic cfDNA analyses can allow earlier assessment of MRD status, as they do not depend on tissue retrieval for sequencing and customization of a ctDNA panel, hence minimizing delays to start of adjuvant therapy [

27]. Analysis of cfDNA without prior knowledge about the mutation status may also prove applicable to screen for previously unknown malignant disease. Using Safe SeqS assays to assess a single tumor-specific somatic mutation in cfDNA in each patient, 42% of recurrences were detected [

14]. Another tumor-informed, hybrid-capture cfDNA sequencing MRD assay called AlphaLiquid® Detect was used to target large sets of patient-specific mutations by sequencing, efficiently predicting recurrence of disease [

28]. Two blood-based liquid biopsy tests have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for guidance in treatment decisions for patients with solid cancer. Guardant360 CDx and FoundationOne Liquid CDx were both approved in 2020 with intention to identify cancer patients who may benefit from certain treatments by detecting genetic alterations in cfDNA in plasma [

29,

30].

In this study we evaluated a tumor-informed mutation detection assay, superRCA. The assay was applied to samples from CRC patients in stages I through IV. At least one hotspot mutation could be detected in plasma cfDNA at diagnosis in 17 of 19 patients with identified hotspot mutations in tumor gDNA, and the assay revealed dynamic changes of MAF over time. In four of these patients the MAF increased postoperatively and/or during follow-up, which accorded with their recurrent clinical course. Hotspot mutations were not detected for two of the patients who experienced recurrent disease. There might be several causes for this, one being tumor heterogeneity. Due to intratumoral heterogeneity caused by dynamic changes occurring over time in the tumor and the uneven distribution of subpopulations of mutation clones across the tumor tissue, hotspot mutations might have been missed [

31]. Another possible reason is the limited mutation panel. Since this study based the MRD assessment on tissue data, mutations outside of the current routinely used panel would have been missed. However, even though the mutation panel is small, it is clinically relevant since it includes the mutations currently checked before treatment decisions, and it can easily be customized to include other mutations as needed. None of the wild-type samples were positive for any of the mutations included in the superRCA CRC Mutation assay target panel. In this case, none of the investigated recurrences seem to have acquired any of the mutations covered by the mutation target panel. Even though these samples were negative for all the mutations tested, analyzing 44 different mutant variants in cfDNA plasma samples with limited DNA amounts demonstrated the potential of the assay for high throughput screening for numerous mutant variants in scarce DNA samples. Blind screening of the cfDNA samples collected at diagnosis using the whole superRCA CRC Mutation target panel assay would correctly genotype 17 out of 25 (68%) patients in this cohort. In a prospective study with metastatic CRC patients, ctDNA levels were analyzed in post-treatment and follow-up blood samples. Five out of 35 patients were ctDNA-positive for a

KRAS,

NRAS or

BRAF mutation by ddPCR and in total, 17 patients had recurrent disease [

16]. In comparison to our study, Boysen et al. [

16] reported more cases and more recurrences. However, slightly fewer recurrences were detected by their methods, four out of 10 (40%), compared to four out of six (67%) by cfDNA analysis using superRCA. This comparison only includes the patients with known mutational status. Moreover, no false positive cases were detected by superRCA, while one was observed by Boysen et al.

A delay of at least two to four weeks after curative surgery is required in MRD assessment through cfDNA testing, in order to ensure good sensitivity. The presence of high levels of normal cfDNA after surgery can dilute the ctDNA levels leading to lower sensitivity [

18,

32]. The timing of blood sampling affects the ctDNA levels since the release of ctDNA can be affected by factors such as the surgery and inflammatory or infectious processes. Thus, depending on the scientific question, the blood sampling should be planned accordingly. During treatment, both normal and tumor cells are directly affected, influencing ctDNA levels, possibly with a detectable change within days to weeks. Long-term changes may occur in weeks to months and correlates more accurately to actual shrinkage of the tumor [

33]. In this study, time points for the included samples varied. The time points for the included plasma samples were limited by the availability of plasma samples with sufficient amount. This could be addressed by collecting the samples at predetermined time points with regard to patient-specific treatments, as is done in U-CAN, while securing sufficient amounts of each plasma sample. With shorter intervals between sample collection it will be possible to investigate how long before clinically manifest recurrent disease that hotspot mutations can be detected in cfDNA.

The superRCA technique described here, presents several advantages in monitoring cancer patients by screening for patient-specific mutations compared to alternative approaches. While rare mutation monitoring by sequencing is highly flexible, it is costly to achieve high sensitivity, and turn-around time is long. superRCA, can be performed in a few hours, and is capable of detecting mutations at rates as low as one in 100,000 [

19]. Moreover, as shown here, several mutations can be targeted in parallel in the limited DNA samples available by liquid biopsy, and readout only depends on an installed base of flow cytometers.

The ability of superRCA to reveal recurrence of solid tumors should be validated in larger cohorts in future studies, as well as in prospective studies with predetermined time points for sample collection. Since the MRD assessment was based on tissue data, relevant mutations outside the current panel would have been missed, but could be targeted in future studies. Patient-specific mutations identified by initial sequencing upon diagnosis can be used to establish dedicated assays that complement the standardized multiplex panel used in this study. The sensitivity and multiplexing potential of superRCA for mutation analysis in cfDNA may allow earlier detection of recurrent disease for prompt therapy adjustment. By predicting the risk of micrometastatic disease, the assays may inform selection of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II colon cancer patients and of optimal combination and duration of treatment in stage III colon cancers.

5. Conclusions

The superRCA assay performed well in analyses of hotspot mutations in cfDNA. The assay is a promising tool to monitor CRC patients for recurrence via ctDNA. The analyses could potentially decrease recurrence risks by allowing treatment to be promptly initiated for those in greatest need. Further validation of the assay in larger cohorts will be required.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org., Table S1: The superRCA CRC Mutation assay target panel; Table S2: Mutant allele frequencies of hotspot mutations

a priori known in tumor and normal gDNA by superRCA; Table S3: Mutant allele frequencies of hotspot mutations determined by superRCA in plasma cell-free DNA at diagnosis, early and later follow-up; Figure S1: Days from diagnosis to surgery, early and later follow-up plasma samples for all 25 patients and days to recurrent disease for applicable patients. Figure S2: Total cfDNA input for plasma samples at diagnosis, early and later follow-up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S., U.L., and L.C.; methodology, L.C.; validation, L.C., and T.E.; formal analysis, L.C. and T.E.; investigation, E.S, L.N. and L. M.; resources, L.N., L.M. and P-H.E.; data curation, E.S., L.N., P-H.E., L.M. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S., L.N., S.A., B.G., T.S.; writing—review and editing, E.S., L.N., P-H.E., L.M., L.C., T.E., B.G., U.L. and T.S.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, B.G., U.L and T.S.; project administration, U.L. and T.S.; funding acquisition, U.L. and T.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by European Commission, grant number 294409 and 115234; the Swedish Research Council, grant number 2013-06023, 2014-02969, 2018-05895 and 2022-00570; the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, grant number SB16-0046; the Swedish Cancer Society, grant number 19 0384 and CAN 2018/772; and Vinnova, grant number 2019-01464.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved under the ethical permit Uppsala EPN 2015-419.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

Sample collection was supported by U-CAN, through Uppsala Biobank and the Department of Clinical Pathology, Uppsala University Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

L.C and U.L are founders and shareholders of Rarity Bioscience, a company formed after the study was initiated, now producing superRCA assays. L.C and T.E are employed at Rarity Bioscience. The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209-249. [CrossRef]

- Osterman, E.; Glimelius, B. Recurrence Risk After Up-to-Date Colon Cancer Staging, Surgery, and Pathology: Analysis of the Entire Swedish Population. Dis Colon Rectum 2018, 61, 1016-1025. [CrossRef]

- Argilés, G.; Tabernero, J.; Labianca, R.; Hochhauser, D.; Salazar, R.; Iveson, T.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Quirke, P.; Yoshino, T.; Taieb, J.; et al. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 1291-1305. [CrossRef]

- Pagès, F.; Mlecnik, B.; Marliot, F.; Bindea, G.; Ou, F. S.; Bifulco, C.; Lugli, A.; Zlobec, I.; Rau, T. T.; Berger, M. D.; et al. International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet 2018, 391, 2128-2139. [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Tomasetti, C.; Li, L.; Springer, S.; Kinde, I.; Silliman, N.; Tacey, M.; Wong, H. L.; Christie, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis detects minimal residual disease and predicts recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8, 346ra392. [CrossRef]

- McKiernan, J. M.; Buttyan, R.; Bander, N. H.; de la Taille, A.; Stifelman, M. D.; Emanuel, E. R.; Bagiella, E.; Rubin, M. A.; Katz, A. E.; Olsson, C. A.; et al. The detection of renal carcinoma cells in the peripheral blood with an enhanced reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay for MN/CA9. Cancer 1999, 86, 492-497. [CrossRef]

- Loberg, R. D.; Fridman, Y.; Pienta, B. A.; Keller, E. T.; McCauley, L. K.; Taichman, R. S.; Pienta, K. J. Detection and isolation of circulating tumor cells in urologic cancers: a review. Neoplasia 2004, 6, 302-309. [CrossRef]

- Zygulska, A. L.; Pierzchalski, P. Novel Diagnostic Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 852. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhu, L.; Song, J.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Li, W.; Luo, P.; Sun, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Liquid biopsy at the frontier of detection, prognosis and progression monitoring in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer 2022, 21, 86. [CrossRef]

- Osumi, H.; Shinozaki, E.; Yamaguchi, K.; Zembutsu, H. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA for colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci 2019, 110, 1148-1155. [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Kotani, D.; Yukami, H.; Mishima, S.; Sawada, K.; Shirasu, H.; Ebi, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Aleshin, A.; et al. CIRCULATE-Japan: Circulating tumor DNA-guided adaptive platform trials to refine adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci 2021, 112, 2915-2920. [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Cohen, J.; Li, L.; Hong, W.; Christie, M.; Wong, H. L.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Thomson, B.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA dynamics and recurrence risk in patients undergoing curative intent resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases: A prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2021, 18, e1003620. [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J. D.; Lahouel, K.; Lo, S. N.; Wang, Y.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.; Lee, M.; Harris, S.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis Guiding Adjuvant Therapy in Stage II Colon Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 2261-2272. [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J. D.; Wang, Y.; Christie, M.; Simons, K.; Lee, M.; Wong, R.; Kosmider, S.; Ananda, S.; McKendrick, J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analyses as Markers of Recurrence Risk and Benefit of Adjuvant Therapy for Stage III Colon Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2019, 5, 1710-1717. [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Wong, H. L.; Roebert, J.; Christie, M.; Tacey, M.; Wong, R.; Singh, M.; Karapetis, C. S.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA as an early marker of therapeutic response in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2015, 26, 1715-1722. [CrossRef]

- Boysen, A. K.; Pallisgaard, N.; Andersen, C. S. A.; Spindler, K. G. Circulating tumor DNA as a marker of minimal residual disease following local treatment of metastases from colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2020, 59, 1424-1429. [CrossRef]

- Zviran, A.; Schulman, R. C.; Shah, M.; Hill, S. T. K.; Deochand, S.; Khamnei, C. C.; Maloney, D.; Patel, K.; Liao, W.; Widman, A. J.; et al. Genome-wide cell-free DNA mutational integration enables ultra-sensitive cancer monitoring. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1114-1124. [CrossRef]

- Malla, M.; Loree, J. M.; Kasi, P. M.; Parikh, A. R. Using Circulating Tumor DNA in Colorectal Cancer: Current and Evolving Practices. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 2846-2857. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Eriksson, A.; Weström, S.; Pandzic, T.; Lehmann, S.; Cavelier, L.; Landegren, U. Ultra-sensitive monitoring of leukemia patients using superRCA mutation detection assays. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 4033. [CrossRef]

- Glimelius, B.; Melin, B.; Enblad, G.; Alafuzoff, I.; Beskow, A.; Ahlström, H.; Bill-Axelson, A.; Birgisson, H.; Björ, O.; Edqvist, P. H.; et al. U-CAN: a prospective longitudinal collection of biomaterials and clinical information from adult cancer patients in Sweden. Acta Oncol 2018, 57, 187-194. [CrossRef]

- Dasari, A.; Morris, V. K.; Allegra, C. J.; Atreya, C.; Benson, A. B., 3rd; Boland, P.; Chung, K.; Copur, M. S.; Corcoran, R. B.; Deming, D. A.; et al. ctDNA applications and integration in colorectal cancer: an NCI Colon and Rectal-Anal Task Forces whitepaper. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020, 17, 757-770. [CrossRef]

- Schøler, L. V.; Reinert, T.; Ørntoft, M. W.; Kassentoft, C. G.; Árnadóttir, S. S.; Vang, S.; Nordentoft, I.; Knudsen, M.; Lamy, P.; Andreasen, D.; et al. Clinical Implications of Monitoring Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017, 23, 5437-5445. [CrossRef]

- Regionala Cancercentrum i samverkan. Nationellt vårdprogram Tjock- och ändtarmscancer. Available online: https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/globalassets/cancerdiagnoser/tjock--och-andtarm-anal/vardprogram/nationellt-vardprogram-tjock-andtarmscancer.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Wille-Jørgensen, P.; Syk, I.; Smedh, K.; Laurberg, S.; Nielsen, D. T.; Petersen, S. H.; Renehan, A. G.; Horváth-Puhó, E.; Påhlman, L.; Sørensen, H. T. Effect of More vs Less Frequent Follow-up Testing on Overall and Colorectal Cancer-Specific Mortality in Patients With Stage II or III Colorectal Cancer: The COLOFOL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 2095-2103. [CrossRef]

- Reinert, T.; Henriksen, T. V.; Christensen, E.; Sharma, S.; Salari, R.; Sethi, H.; Knudsen, M.; Nordentoft, I.; Wu, H. T.; Tin, A. S.; et al. Analysis of Plasma Cell-Free DNA by Ultradeep Sequencing in Patients With Stages I to III Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2019, 5, 1124-1131. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A. R.; Van Seventer, E. E.; Siravegna, G.; Hartwig, A. V.; Jaimovich, A.; He, Y.; Kanter, K.; Fish, M. G.; Fosbenner, K. D.; Miao, B.; et al. Minimal Residual Disease Detection using a Plasma-only Circulating Tumor DNA Assay in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 5586-5594. [CrossRef]

- Biagi, J. J.; Raphael, M. J.; Mackillop, W. J.; Kong, W.; King, W. D.; Booth, C. M. Association between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011, 305, 2335-2342. [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, S. B.; Heo, S.; Lim, Y.; Lee, W.; Cho, S. H.; Ahn, J.; Kang, J. K.; Kim, S. Y.; Kim, H. P.; Bang, D.; et al. Personalised circulating tumour DNA assay with large-scale mutation coverage for sensitive minimal residual disease detection in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2023. [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data (SSED) for Guardant360® CDx. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf20/P200010S010B.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED) for FoundationOne® Liquid CDx. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf19/P190032S005B.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A. T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018, 15, 81-94. [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, T. V.; Tarazona, N.; Frydendahl, A.; Reinert, T.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; Carbonell-Asins, J. A.; Sharma, S.; Renner, D.; Hafez, D.; Roda, D.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA in Stage III Colorectal Cancer, beyond Minimal Residual Disease Detection, toward Assessment of Adjuvant Therapy Efficacy and Clinical Behavior of Recurrences. Clin Cancer Res 2022, 28, 507-517. [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Attard, G.; Bidard, F. C.; Curigliano, G.; De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Diehn, M.; Italiano, A.; Lindberg, J.; Merker, J. D.; Montagut, C.; et al. ESMO recommendations on the use of circulating tumour DNA assays for patients with cancer: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann Oncol 2022, 33, 750-768. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).