1. Introduction

Regions such as South China, the Qinling Mountains, Southern Tibet, and Xinjiang Tianshan are known for their abundant antimony-gold resources [

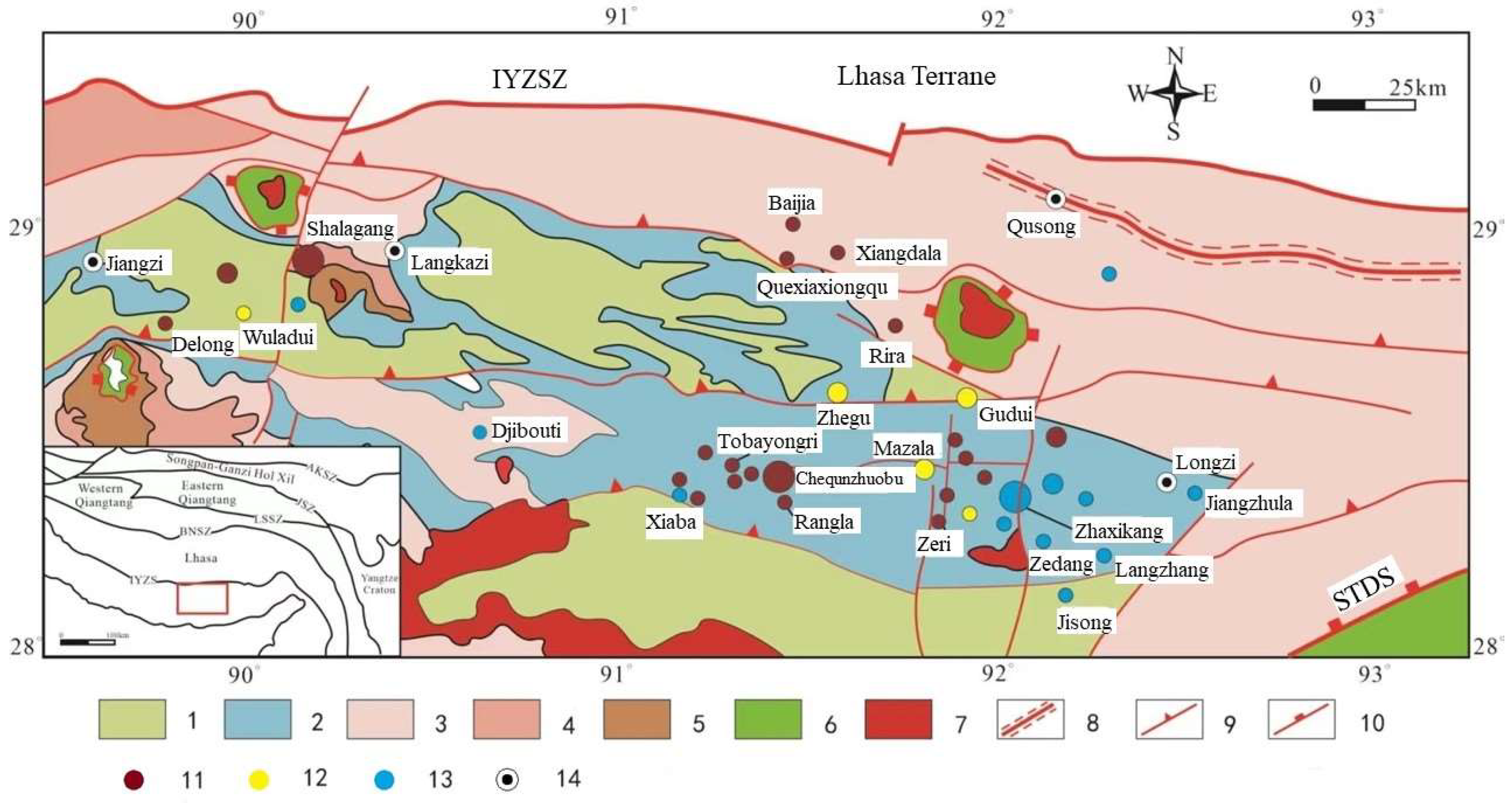

1]. Situated within the Tethys Himalayan region, the antimony polymetallic mineralization belt in southern Tibet is positioned between the Indus-Yarlung Zangbo Suture Zone (IYZSZ) and the South Tibetan Detachment System (STDS) (

Figure 1) [

2]. The region's stratigraphy is extensively exposed, exhibiting intricate tectonic features, and antimony single deposits and antimony polymetallic deposits are widely distributed due to multiple phases of collision and accretion between the Indian plate and the Eurasian plate [

3]. Antimony (gold) deposits within the extensive South Tibetan metallogenic belt are predominantly associated with sedimentary rocks as the main ore-forming wall rocks, exhibiting a wide distribution range, significant production outputs, and substantial metal reserves. The near east-west and north-south fault structures control the spatial distribution of these antimony (gold) deposits (

Figure 1), and the majority of them occur in Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous siltstones, feldspathic sandstones, and carbonaceous slates, as well as alkali-rich medium-basic intrusive rock masses. The organic stuff is abundant in the ore-forming wall rocks.

Organic matter plays a crucial role in the migration and enrichment processes of mineralizing elements, particularly in the formation of metallic sedimentary deposits [

6,

7,

8]. Significant quantities of liquid hydrocarbons can be generated through the thermal decomposition of organic matter during both diagenesis and deep diagenesis [

9,

10]. These liquid hydrocarbons, formed during the evolution of sedimentary organic matter, have been identified in various metal deposits, such as orogenic antimony-gold deposits [

12,

14], Witwatersrand-type Au-U deposits in South Africa [

15], sediment-hosted U deposits [

16,

17], and Mississippi Valley-type Pb-Zn deposits [

20,

19,

20].

Numerous antimony single deposits and antimony-gold deposits are closely associated with liquid hydrocarbons. Antimony single deposits, such as the DaChang antimony deposit in Qinglong, Guizhou, contain liquid hydrocarbons or organic inclusions that are present within the ore and oil source rocks in the marginal basins, and there are multi-layered asphalt layers (ancient oil deposits), with asphalt reserves totaling 368,400 tons. Additionally, there is a close spatial relationship between the antimony mineralization layer and asphalt layers [

21,

22]. Furthermore, isotopic analyses of ore samples from the Meiduo antimony deposit in Northern Tibet indicate that organic matter was involved in the mineralization process, and Raman laser and micro-infrared spectroscopic analyses reveal that the mineralized fluids contain components including CH

4, C

6H

6, and CH

2 [

23]. In the fluid inclusions of the mineralized ores, antimony gold deposits, such as the gold and antimony ore deposits in Lannigou, Guizhou, contain saturated hydrocarbons, unsaturated hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, and other organic substances, and are intimately associated with the oil layer [

24,

25]. Moreover, Zhai et al [

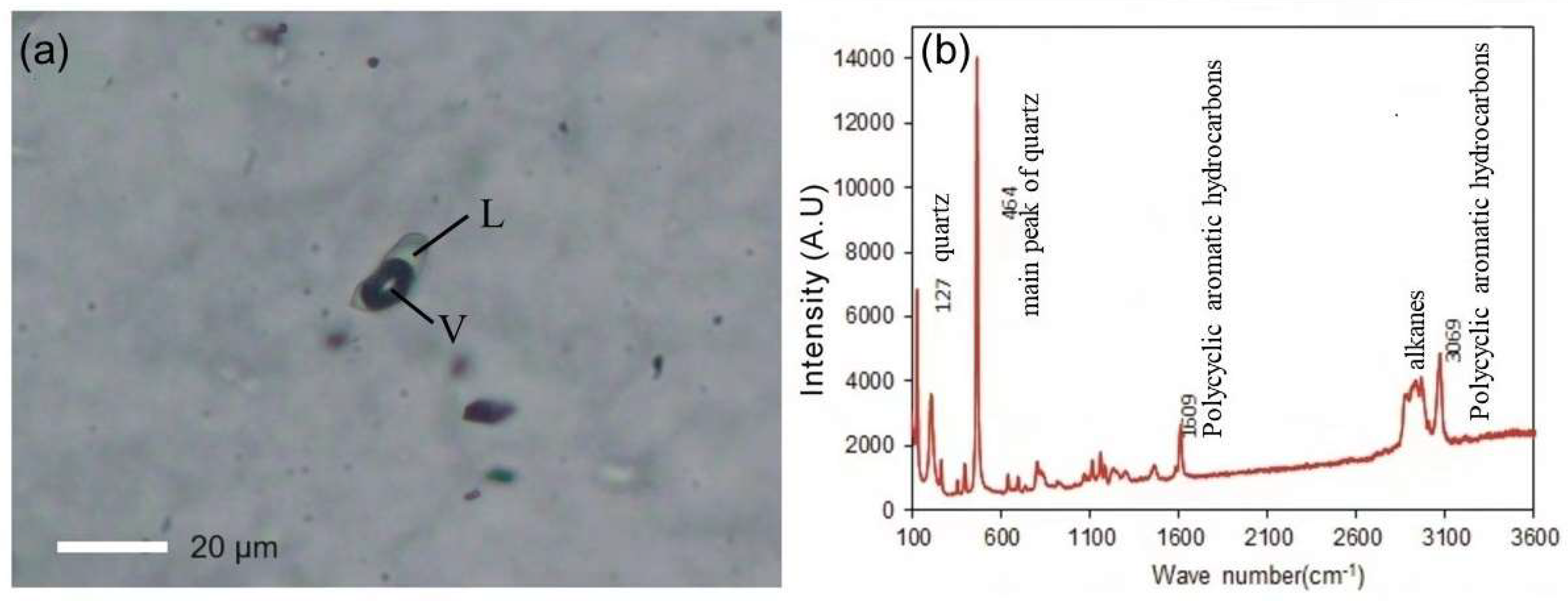

14] employed petrographic observation, Raman spectroscopy, and fluid inclusion micro thermometry to detect gas-liquid two-phase or one-phase organic inclusions at room temperature in the vein mineral quartz and the ore mineral phengite, both of which formed during the metallogenic phase of the Shalagang antimony deposit and the Mazala antimony-gold deposit in southern Tibet (

Figure 2a). Raman spectroscopy analysis indicated that the organic inclusions consisted mainly of alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (

Figure 2b). Levine [

26] proposed that the presence of a considerable quantity of liquid-phase and gas-liquid two-phase organic inclusions in the ore indicated the involvement of liquid hydrocarbons in the transport of ore-forming materials, and the occurrence of liquid organic inclusions indicated the maturation of hydrocarbons.

The current research on the ore-forming fluids of orogenic antimony-gold deposits primarily emphasizes the investigation of their inorganic components. Therefore, additional research is needed to confirm whether liquid hydrocarbons in ore-forming fluids can be involved in antimony mineralization despite indications of their potential positive role in the process. Recent experimental studies by various scholars have shown that natural liquid hydrocarbons have the capacity to transport sufficient mineralizing materials to support the mineralization process. These studies have specifically investigated the solubility of zinc, uranium, palladium, and other metals in liquid hydrocarbons [

31,

32,

32,

30,

31,

32]. N-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol are typical constituents of liquid hydrocarbons formed through the pyrolysis of organic matter, representing the wide range of organic groups present in such hydrocarbons. These two organic compounds are suitable for this experiment because of their physical characteristics, including their melting and boiling temperatures, as well as their stability under various redox and temperature conditions. Therefore, in our experimental investigation to assess the potential contribution of liquid hydrocarbons in ore-forming fluids to the transport of antimony, we utilized n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol.

We conducted experiments involving the dissolution of antimony metal in n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol. The experiments were conducted at temperatures of 100, 150, and 200 °C, with varying reaction durations ranging from 5 to 10 days. Additionally, we performed an XPS analysis to investigate the surface composition of the antimony lumps after the reaction. This analysis enabled us to investigate the potential efficiency of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol in transporting antimony and to determine if liquid hydrocarbons can participate in the transportation of antimony in the ore-forming fluids. This research provides new insights into the transport mechanism of antimony in orogenic antimony-gold deposits located in southern Tibet and hosted by sedimentary rocks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Description

The organic reagents n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol were obtained from Wengjiang Reagent and produced in Guanchang Industrial Zone, Guandu Town, Wengyuan County, Shaoguan, Guangdong. The properties of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol are displayed in

Table 1.

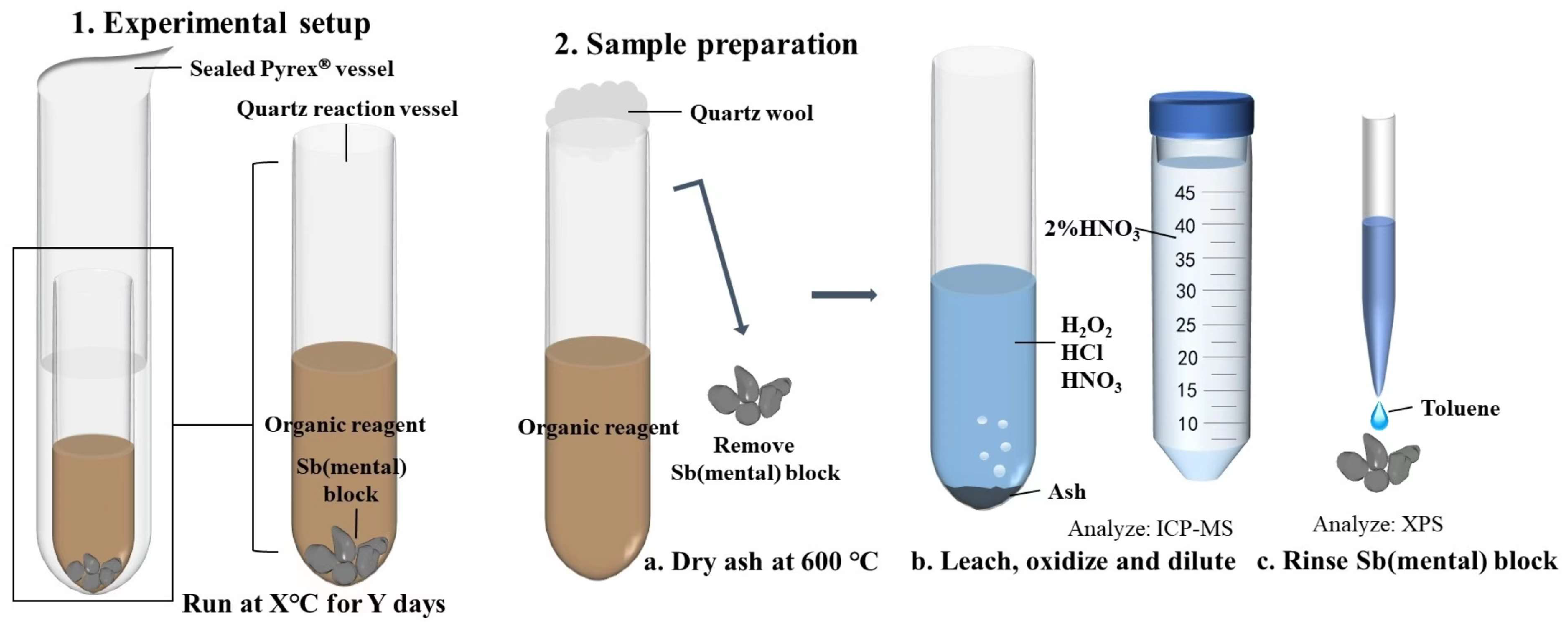

2.2. High-temperature Experiments

The experiments were conducted in a sealed reactor consisting of a larger tube placed over a smaller tube, with the larger tube made of high borosilicate glass test tubes (OD = 12 mm, ID = 10 mm) and the smaller tube made of quartz test tubes (OD = 9 mm, ID = 7 mm) (

Figure 3). The decision to conduct tests at 100, 150, and 200 °C was based on the temperature ranges identified through micro thermometry of fluid inclusions in orogenic antimony deposits, as well as the physical and chemical properties of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol. To minimize the risk of thermal degradation of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol and ensure sufficient time for equilibrium to be reached, the lowest temperature within this range was chosen.

Prior to the experiment, the borosilicate glass and quartz tubes were cleaned with nitric acid (~75% HNO

3) for 24 hours, rinsed with ultrapure water, and dried at 100 °C for 2 hours. The antimony was introduced into the quartz tubes in the form of pure metal blocks with a controlled mass of approximately 0.50 g. Two experimental groups were established: one group received a mixture of 0.25 ml n-dodecane and 0.25 ml n-dodecanethiol in the quartz test tubes, while the other group received only 0.25 ml of n-dodecane. After the addition of the reagents as well as the antimony blocks, the quartz test tubes were carefully introduced into the borosilicate glass test tubes and then sealed with a high-temperature flame. All the weights, that is, the weights of the quartz test tubes before and after the addition of the antimony metal blocks, as well as the n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol, were carefully determined during the experiment using a high-precision analytical balance. Sanz-Robinson et al. [

30,

31] conducted kinetic experiments using a range of crude oil samples and a controlled temperature gradient to evaluate the solubility of palladium and zinc in crude oil and determine the equilibrium time. Palladium and zinc wires were reacted with equal volumes of crude oil for 5, 10, 15, and 30 days. The concentration of palladium in the crude oil started to stabilize after approximately five days, while zinc reached a steady concentration in less than 15 days and, in certain instances, within five days. Therefore, based on the findings of previous studies, reaction durations of 5 and 10 days were selected to ensure the attainment of steady-state concentrations of antimony within a reasonable timeframe.

After completing the weighing process, the sealed reactor was placed inside a tabletop muffle furnace oven preheated to the required temperature. The temperature was maintained within a ±1 °C range. The experimental setup utilized a muffle furnace manufactured by Shanghai Jinping Instrumentation Co., Ltd. The furnace had dimensions of 500 mm in length, 300 mm in width, and 200 mm in height. It operated at a rated voltage of 380 V, a rated temperature of 1200 °C, and a power output of 12 kW, incorporating an electric heating wire as the heating element.

After the experiment, the reactors were opened using a diamond cutter, and the quartz test tubes were carefully extracted using disposable tweezers. Clean quartz wool was used to plug the openings of the quartz test tubes, ensuring no material loss due to volatilization and facilitating subsequent analytical tests.

2.3. XPS Analysis

Organic reagents that had not been completely reacted were evaluated using a method similar to that described by Sugiyama and Williams-Jones [

33]. The crude oils were ashed using a combination of thermal combustion and chemical oxidation. The procedure involved transferring the remaining organic chemicals into a clean quartz test tube, sealing the tube's opening with clean quartz cotton, and subjecting the tube to cauterization at 600 °C for 12 hours. After cauterization, the quartz test tube was treated with a mixture of 0.25 ml HNO

3 (75%), 0.25 ml HCl (35%), and 0.5 ml H

2O

2 (30%) and left to leach for 24 hours, ensuring complete dissolution of any remaining ash. The leaching solution was diluted 1000 times with 2% HNO

3 solution before analyzing and determining the amount of dissolved antimony in the solution using an ICP-MS quadruple rod plasma mass spectrometer (Agilent 7700x, USA) with Y as the internal Standard. Incompletely reacted antimony blocks were removed with disposable tweezers, washed with toluene, and vacuum-dried for 24 hours at room temperature. Subsequently, the surface composition of the antimony blocks was analyzed and studied using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Kα spectrometer. The measurement employed Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV, 12 kV, 720 W) with an X-ray spot size of 400 μm. The scanning mode was set to CAE, with the lens mode as Standard. The full-spectrum scanning fluence energy was 150 eV, the narrow-spectrum scanning fluence energy was 40 eV, and the resolution was ≤0.45 eV. Energy correction was conducted using the surface contamination C1s peak (284.8 eV). The resulting data were fitted and analyzed using XPS Peak41 software and background removal through the Shirley-type method.

3. Results

3.1. Results from the Antimony Solubility Experiments

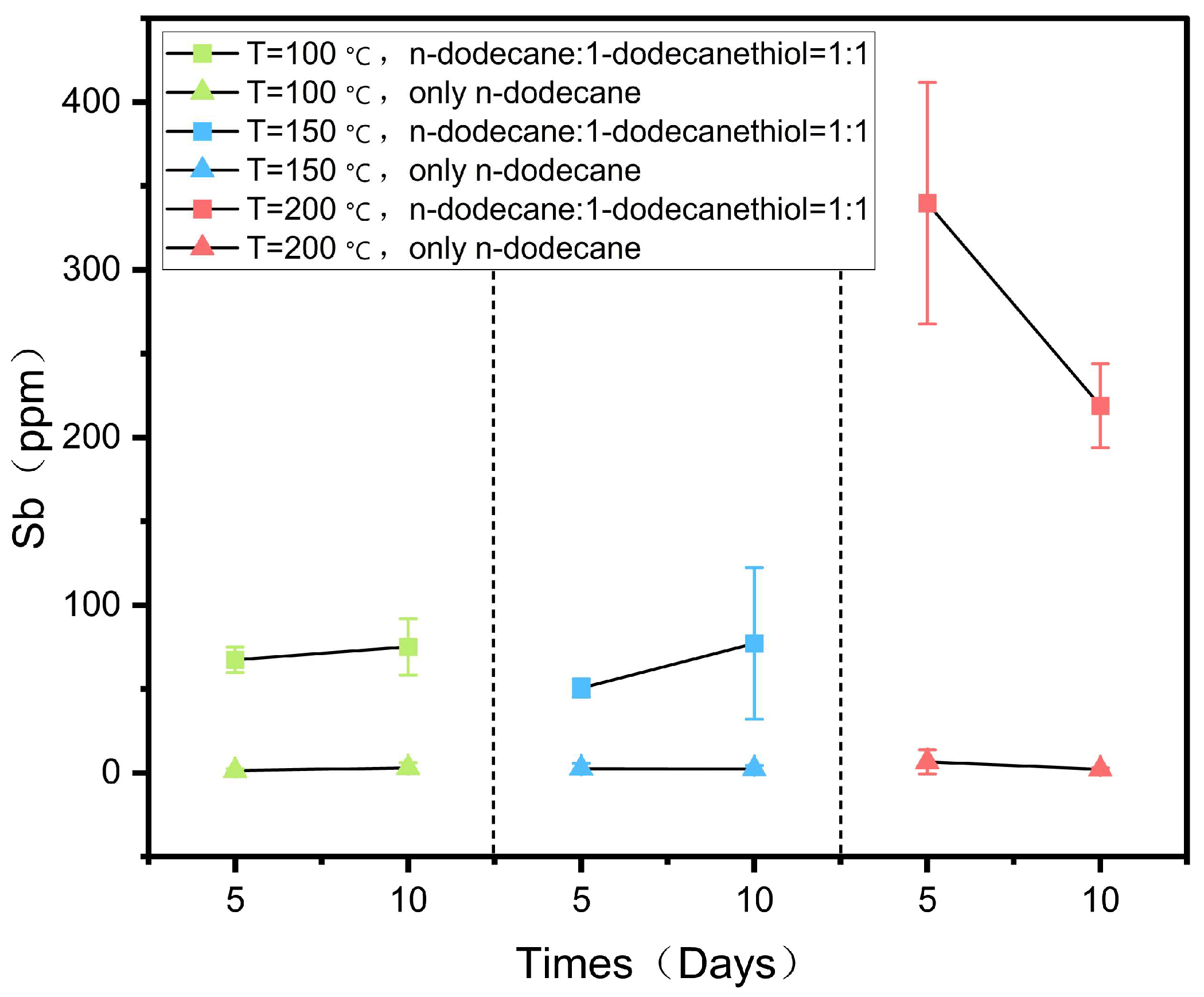

The dissolution of antimony blocks in n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol reagents at 100, 150, and 200 °C is reported in

Table 2 and

Figure 4.

Table 2.

A summary of the experimentally determined solubility of antimony in n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol at 100, 150, and 200 °C. (ppm).

Table 2.

A summary of the experimentally determined solubility of antimony in n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol at 100, 150, and 200 °C. (ppm).

| |

N-dodecane: n-dodecanethiol = 1:1 |

Only n-dodecane |

| |

Times |

5 days |

10 days |

5 days |

10 days |

| Temp. |

|

| 100 °C |

67.44±7.62 |

75.15±16.74 |

1.40±1.02 |

3.02±3.09 |

| 150 °C |

50.58±5.39 |

77.26±45.20 |

2.66±3.08 |

2.41±2.03 |

| 200 °C |

339.76±71.94 |

218.97±25.03 |

6.53±7.17 |

2.27±0.82 |

Figure 4.

Concentration of antimony in both groups of reagents at 100, 150, and 200 °C as a function of the duration of the experiments.

Figure 4.

Concentration of antimony in both groups of reagents at 100, 150, and 200 °C as a function of the duration of the experiments.

The reaction was divided into two groups, with three experiments performed under each set of conditions. One group contained a 1:1 mixture of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol, while the other group used n-dodecane alone as the reagent (

Table 2). The dissolution of antimony was investigated by comparing the two groups. The solubility of antimony in the 1:1 mixture of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol increased with temperature, reaching a maximum of 339.76 ppm at 200 °C, as indicated in

Table 2 and

Figure 4. Moreover, with an increase in reaction time at 100 and 150 °C, the solubility of antimony increased, reaching values of 75.15 ppm and 77.26 ppm on the 10th day, respectively. However, at 200 °C, the solubility of antimony decreased, and on the 5th day, it was higher than on the 10th day, possibly due to slight pyrolysis of the organic reagents during prolonged heating. The solubility of antimony did not increase with temperature in reagents consisting solely of n-dodecane. Only a small amount of antimony was dissolved in n-dodecane, and its solubility did not significantly change at different temperatures or reaction durations, remaining in the range of a few ppm (

Table 2,

Figure 4). These findings demonstrate that the thiol content plays a crucial role in determining the dissolution of antimony.

3.2. Results of XPS Analyses

XPS was employed to measure the spectra of antimony blocks after the reaction in a 1:1 combination of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol at 200 °C, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

Figure 5a illustrates the examination of reagent residues on the surface of the antimony blocks. It was determined that sulfur accounts for approximately 21% of the surface of the antimony metal block. The sulfur (S2p) peaks in the green and red lines correspond to sulfur bound to antimony and have binding energies of 162.06 eV and 160.87 eV (

Figure 5a), respectively. The prominent sulfur (S2p) peak in the blue line corresponds to the unbound free thiol functional group, with a binding energy of 163.31 eV (

Figure 5a) [

34].

XPS tests indicate that most sulfur is chemically bonded to antimony, while a portion exists as unbound free thiols. Additionally,

Figure 5b demonstrates that XPS measurements of the toluene-rinsed surface of the antimony block reveal the presence of a blend of antimony metal and antimony compound (III). The antimony (Sb3d) peaks are depicted by the green and red lines, with binding energies of 530.30 eV and 529.39 eV (

Figure 5b), respectively, corresponding to antimony compounds formed through thiol reactions. During the reaction with the mixed reagents, the antimony metal undergoes oxidation while the thiols undergo reduction.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra obtained by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of antimony blocks after reaction with a 1:1 mixture of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol reagents at 200 ˚C. Figure a shows the XPS spectrum of the residual reagent sulfur form on the antimony block after the reaction. The thiol peak was separated into an unbound thiol peak in blue (163.31 eV), while the sulfur peaks bound to antimony are represented by the green (162.06 eV) and red (160.87 eV) peaks. Figure b displays the XPS spectrum of the antimony block surface after the reaction and rinsing with toluene. The green and red peaks represent the compound antimony, while the blue peak represents the antimony metal.

Figure 5.

XPS spectra obtained by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of antimony blocks after reaction with a 1:1 mixture of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol reagents at 200 ˚C. Figure a shows the XPS spectrum of the residual reagent sulfur form on the antimony block after the reaction. The thiol peak was separated into an unbound thiol peak in blue (163.31 eV), while the sulfur peaks bound to antimony are represented by the green (162.06 eV) and red (160.87 eV) peaks. Figure b displays the XPS spectrum of the antimony block surface after the reaction and rinsing with toluene. The green and red peaks represent the compound antimony, while the blue peak represents the antimony metal.

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Determining the Concentration and Speciation of Antimony in Liquid Hydrocarbons

Previous experimental studies have demonstrated that temperature exerts a significant influence on the solubility of antimony in solution. In a study by Кoлпакoва [

35], the solubility of stibnite ores in H

2S-H

2O solution was examined across temperatures ranging from 100 to 300 °C. The results revealed a substantial alteration in stibnite solubility due to temperature variations, with the maximum solubility observed at 200 °C. He et al. [

36] conducted water-rock leaching experiments on the S, Cl-containing stratum of antimony in a medium-low temperature hydrothermal system. Their findings revealed that the antimony leaching rate increased with rising temperature within the range of 100-200 °C, reaching its peak at 200 °C. William-Jones and Norman [

37] provided evidence of the substantial impact of temperature on antimony precipitation in hydrothermal fluids, highlighting that lower temperatures were more favourable for the formation of stibnite through antimony precipitation. The present experimental study on the dissolution of antimony was conducted at 100, 150, and 200 °C temperature gradients, and the results showed that temperature is an important parameter affecting the solubility of antimony in organic reagents.

Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between antimony solubility and temperature. In the 1:1 mixture of n-dodecane and n-dodecanethiol reagent group, the solubility of antimony exhibits a gradual increase with temperature, reaching its peak at 200 °C (

Figure 4). Research indicates that the solubility of most minerals increases as temperature rises. Within a specific range, higher temperatures enhance the extraction of mineralized metals from surrounding mineralized rocks by ore-forming fluids, leading to a significant elevation in the concentration of mineralized components in the fluids and facilitating mineralization enrichment. Additionally, temperature impacts the density of the ore-forming fluid. As temperature increases, the density of the fluid decreases, prompting its upward flow toward faults, fracture zones, and other regions of the ore that are conducive to mineralization. This, in turn, affects the mineralization process.

The findings of our study indicate that the thiol group can dissolve substantial quantities of antimony, with 339 ppm of antimony dissolved at 200 °C. Additionally,

Figure 4 illustrates that the solubility of antimony in the thiol group is significantly greater compared to the n-dodecane group (

Figure 4). Based on the XPS characterization results, unbound thiols were found to persist on the surface of the metallic antimony block after the completion of the reaction (

Figure 5). Additionally, the surface of the antimony block exhibited a higher presence of sulfur-bound compounds, providing evidence for the strong affinity between antimony and the reduced sulfur in the reagent mixture. The experimental results reveal that thiol is the critical parameter governing the dissolution of antimony in organic reagents. Metals can form ligands by interacting with organic compounds, and the stability constants of organic-metal complexes are significantly greater than those of inorganic complexes. Therefore, as long as low concentrations of organic ligands are present in mineralized hydrothermal fluids, organic-metal complexes are dominant [

38]. The ability of specific sulfur compounds, especially thiols, to create organometallic complexes with chalcophile elements is widely acknowledged [

39,

40]. In contrast, antimony is a chalcophile element that effortlessly combines with sulfur. Furthermore, unlike n-dodecane, which is a soft base, n-dodecanethiol has polarity due to the presence of sulfur-based functional groups, and antimony metal is a junction acid; hence, the thiol reacts more readily with antimony, enabling its solubilization in the reagent. Therefore, liquid hydrocarbons with a high concentration of thiols can play a role in the transportation of antimony during the mineralization process. The amount of hydrogen sulfide in the mineralized layer affects the concentration of thiols in liquid hydrocarbons. In the deep source area of antimony-gold mines in southern Tibet, hydrocarbons and sulfates undergo thermochemical reduction reactions, resulting in the generation of substantial amounts of hydrogen sulfide. This hydrogen sulfide can react with organic compounds present in crude oil and natural gas, leading to an increase in the concentration of thiols and the subsequent production of liquid hydrocarbons that are enriched with thiols [

44,

42,

43,

44].

4.2. Formation of Liquid Hydrocarbons in Orogenic Antimony-Gold Ores and Their Role in the Mineralization Process

The collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates occurred approximately 65 million years ago [

45,

46,

47], resulting in a collisional orogenic process that can be divided into two distinct phases: early collision-extrusion and late orogenic intracontinental extension. Throughout this process, various geological features emerged in southern Tibet, including folded tectonics, retrograde fractures, metamorphic nuclear vaults, and near east-west and near north-south fracture systems (

Figure 1) [

2,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. These geological features have played a role in constraining the mineralization of antimony (gold) deposits. Numerous antimony single deposits and antimony-gold deposits are present within the Southern Tibetan Plateau, of which the Shalagang antimony deposit represents the characteristics of antimony deposits with sedimentary rocks as the main ore-forming enclosing rocks, and the Mazala antimony-gold deposit represents the characteristics of antimony-gold deposits with sedimentary rocks as the main ore-forming enclosing rocks. The Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous strata, where these two deposits are located, are most developed with siltstone, sandstone, quartz sandstone, carbonaceous slate, and marl. These strata contain a large amount of sedimentary organic matter, which often constitutes the ore-forming wall rocks of the deposits [

53]. Previous studies have revealed that the Shalagang antimony deposit and the Mazala antimony-gold deposit are shallow, low-temperature deposits. Additionally, fluid inclusions within the relevant mineralized ores of these two deposits have been found to contain liquid hydrocarbon components (

Figure 2) [

14,

54].

The results of our tests indicate that liquid hydrocarbons play a crucial role in antimony mineralization transport. Previous research by Migdisov et al. [

27] examined the solubility of gold in a variety of natural crude oils at temperatures ranging from 100 to 300 °C, yielding results comparable to those presented here. Their experiments demonstrated that liquid hydrocarbons may have significantly contributed to the formation of the deposits. Liquid hydrocarbons can extract gold from its host rocks, transport it in appreciable concentrations, and deposit it in economically exploitable amounts. Crede et al. [

28,

29] performed an in-situ XAS experiment at 25-250 °C to determine the morphology and structural properties of gold complexes in aqueous and oil-based fluids (S-free n-dodecane, S-bearing 1-dodecanethiol). Since sulfur and organothiol compounds are ubiquitous and abundant components in natural oils, the experimental results show that natural oils can potentially enrich gold from coexisting gold-bearing brines, demonstrating the importance of liquid hydrocarbons in conveying and enriching gold mineralization. As a result, we may conclude that liquid hydrocarbons can play an essential role in both antimony transport and gold mineralization.

This also provides a possible explanation mechanism for the co-occurrence of antimony and gold ores in southern Tibet from the ore-forming fluid. Regional metamorphic tectonic events impact the organic-rich peripheral rocks within the orogenic antimony-gold deposits associated with sedimentary rock strata during the diagenesis stage, leading to the liberation of organic components, including liquid hydrocarbons. These components are subsequently enriched in the ore-bearing fluids, facilitating the entry of the active and more active antimony and gold elements into the reservoir in complex and other forms, in conjunction with water and oil. Ductile shear zones and faults create favourable conditions for the upwelling of ore-bearing fluids. These fluids are subsequently influenced by changes in temperature and pressure, leading to their migration, precipitation in favourable tectonic sites, and the eventual formation of mineralized bodies [

2,

11].

4.3. Evaluation of the Potential of Liquid Hydrocarbons as Ore-forming Fluids in Orogenic Antimony-Gold Ores

When evaluating the potential of liquid hydrocarbons as ore-forming fluids, it is crucial to compare antimony solubility in them to antimony solubility in hydrothermal fluids. The solubility characteristics of pyroxene indicate that solutions of different properties can dissolve and transport high concentrations of antimony. Elevated temperatures and mildly acidic or alkaline conditions are particularly favourable for the dissolution and transport of antimony [

55]. Extensive research data on the antimony concentration in modern geothermal fluids has shown significant variability, with the majority having antimony contents around 0.1 ppm. In contrast, fluids in New Zealand's geothermal areas exhibit antimony contents as high as 84.42-238.25 ppm, demonstrating the presence of fluids with elevated antimony levels in nature. Nevertheless, compared to the antimony solubility in this experiment, it is clear that the antimony level in modern geothermal fluids is far from saturation. In addition, studies have shown that hydrothermal solutions forming epithermal gold deposits contain only a few tens of ppb of gold [

56], which is within the solubility range of gold in crude oils identified in the study of Migdisov et al [

27]. Hence, we conclude that liquid hydrocarbons have great potential as mineralizing fluids for transporting antimony and gold mineralization.

Additionally, the antimony concentration and extractability of the host rock are crucial factors in the formation of antimony ore-forming fluids. The average antimony content in magmatic rocks is generally lower than Clark's value, with ultramafic rocks having the lowest antimony content (0.1 ppb), basaltic and acidic rocks exhibiting similar antimony levels (0.2 ppb), and sedimentary shales and mudstone rocks containing the highest antimony content (1.5 to 2 ppm) [

57]. The prevalence of sedimentary rocks in southern Tibet, along with the abundant organic matter in the surrounding rocks, creates a favorable metallogenic environment conducive to hydrocarbon reservoir formation. When hydrocarbons come into contact with sulfate minerals at temperatures exceeding 100 °C, they trigger reactions like TSR (thermal sulfate reduction), leading to a substantial increase in thiol levels [

58]. Based on the findings of this experimental work, thiols readily react and combine with antimony, causing antimony oxidation and thiol reduction, effectively inhibiting antimony migration during mineralization. Hydrocarbons with a high thiol content significantly enhance the extraction of antimony metal from ore-forming wall rocks. Consequently, in antimony deposits with sedimentary rock accommodation, organic fluids, rather than aqueous fluids, primarily facilitate antimony transfer. The hydrocarbons found in the inclusions are likely the remaining organic components devoid of thiol after their involvement in metal transportation for mineralization.

This experiment's XPS characterization results show that antimony is readily bonded to thiols (

Figure 5). However, we are unsure of the exact manner in which antimony is transported in liquid hydrocarbons in this instance. Additional ligands or functional groups present in liquid hydrocarbons may also play a significant role in facilitating the transport of antimony. In addition to the formation of organic complexes for metal transportation during mineralization, liquid hydrocarbons can exhibit other forms. An example of this is the synthesis of noble metal nanoparticles (NMNPs) to explore the enrichment and transportation of gold and platinum group elements (PGE) within naturally occurring organic (hydrocarbon) systems [

32]. Furthermore, it has been found that liquid hydrocarbons are more efficient in transporting valuable metals when they are in the form of nanoparticles rather than molecules. Hence, a detailed investigation into the specific form of liquid hydrocarbons involved in the transportation of antimony during mineralization is warranted.

5. Conclusions

(1) Antimony exhibits a pronounced chemical affinity towards reduced sulfur components. The solubility of antimony in organic reagents with a high thiol concentration surpasses its solubility in fluids previously identified as antimony mineralized.

(2) The thermochemical sulfate reaction that occurs in the ore-forming peripheral rocks of orogenic antimony-gold deposits with sedimentary rock accommodation in a specific temperature range produces high concentrations of hydrogen sulfide. This, in turn, leads to the formation of a liquid hydrocarbon rich in thiols. This liquid hydrocarbon with a high thiol content can serve as a carrier within the ore-forming fluids for antimony mineralization.

(3) There is a clear positive correlation between the solubility of antimony and thiols, suggesting that thiols are determinants of antimony solubilization in liquid hydrocarbons. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that other organic ligands, such as porphyrins and carboxylic acids, may also play a role in the dissolution and transport of antimony.

Author Contributions

Y.S. and Z.D. conceived and designed the experiments; Y.S. analyzed the data and wrote this paper; Z.D. and X.S. revised the original manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91855213, 41972070, 41672071, and U1302233), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC0603603 and 2018YFA0702605), International Program for Candidates, Sun Yat-Sen University (SYSU-32110-20230907-0002).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available in the online version of the paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank editors and anonymous reviewers for providing valuable remarks and constructive comments that have enhanced the overall quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could appear to have influenced the work reported.

References

- Li, F.; Zhang, G.Y.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, J.F.; Qin, Z.P.; Chen, X.; Lan, Z.W. Mineralization process of the Mazhala Au-Sb deposit, South Tibet: Constraints from fluid inclusions, H-O-S isotopes, and trace elements. Ore Geology Reviews. 2023, 160, 105595. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.S.; Hou, Z.Q.; Gao, W.; Wang, H.P.; Li, Z.Q.; Meng, X.J.; Qu, X.M. Metallogenic characteristics and genetic model of antimony and gold deposits in south Tibetan detachment system. Acta Geologica Sinica. 2006, 80, 1377-1391.

- Feng, X.L.; Du, G.S. The distribution, mineralization types and prospecting and exploration of the gold deposits in Xizang. Tethyan Geology. 1999, 23, 31-38.

- Sun, X.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Wang, C.M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Geng, X.B. Identifying geochemical anomalies associated with Sb-Au-Pb-Zn-Ag mineralization in North Himalaya, southern Tibet. Ore Geology Reviews. 2016, 73, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Tang, J.X.; Chen, W.; Sun, H. Study on the distribution, type and metallogenic regularity of antimony deposit in Tibet. Geology in China. 2023, 1-34.

- Fu, J.M.; Peng, P.A.; Lin, Q.; Liu, D.H.; Jia, R.F.; Shi, J.X.; Lu, J.L. A few issues in the study of organic geochemistry of stratified mineral deposits. Advances in Earth Science. 1990, 5, 43-49.

- Zhuang, H.P.; Lu J.L. Metallogenic deposits associated with organic matter. Geology-Geochemistry. 1996, 4, 6-11.

- Zhuang, H.P.; Lu J.L.; Wen, H.J.; Mao, H.H. Organic matter in hydrothermal ore-forming fluid. Geology-Geochemistry. 1997, 1, 85-91.

- Wan, C.L.; Zhai, Q.L.; Jin, Q. Interaction between source rocks and igneous rocks-a preliminary investigation of dissolution of igneous rocks by organic acids and catalysis of transition metals in the generation of hydrocarbons in the source rocks. Geology-Geochemistry. 2001, 29, 46-51.

- Miao, Y.N.; Li, X.F.; Wang, X.Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.J.; Liu, F.W.; Xia, J. Review on hydrocarbon generation, pores formation and its methane adsorption mechanism in shale kerogen. Scientia Sinica Physica, Mechanica & Astronomica. 2017, 47, 114604. [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.W.; Sun, X.M.; Zhai, W.; Zhou, F.; Liang, Y.H. Ore-forming fluid geochemistry and metallogenic mechanism from Mazhala gold-antimony deposit in southern Tibet, China. Acta Petrologica Sinica. 2013, 29, 1427-1438.

- Hu, S.Y.; Evans, K.; Craw, D.; Rempel, K.; Bourdet, J.; Dick, J.; Grice, K. Raman characterization of carbonaceous material in the Macraes orogenic gold deposit and metasedimentary host rocks, New Zealand. Ore Geology Reviews. 2015, 70, 80-95. [CrossRef]

- Mirasol-Robert, A.; Grotheer, H.; Bourdet, J.; Suvorova, A.; Grice, K.; McCuaig, T.C.; Greenwood, P.F. Evidence and origin of different types of sedimentary organic matter from a Paleoproterozoic orogenic Au deposit. Precambrian Research. 2017, 299, 319-338. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Zheng, S.Q.; Sun, X.M.; Wei, H.X.; Mo, R.W.; Zhang, L.Y.; Zhou, F.; Yi, J.Z. He-Ar isotope compositions of orogenic Mazhala Au-Sb and Shalagang Sb deposits in Himalayan orogeny, southern Tibet: Constrains to ore-forming fluid origin. Acta Petrologica Sinica. 2018, 34, 3525-3538 (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Fuchs, S.; Williams-Jones, A.E.; Jackson, S.E.; Przybylowicz, W.J. Metal distribution in pyrobitumen of the Carbon Leader Reef, Witwatersrand Supergroup, South Africa: evidence for liquid hydrocarbon ore fluids. Chemical Geology. 2016, 426, 45-59. [CrossRef]

- Landais, P. Organic geochemistry of sedimentary uranium ore deposits. Ore Geology Reviews. 1996, 11, 33-51. [CrossRef]

- Spirakis, C.S. The roles of organic matter in the formation of uranium deposits in sedimentary rocks. Ore Geology Reviews. 1996, 11, 53-69. [CrossRef]

- Parnell, J. Metal enrichments in solid bitumens - A review. Mineralium Deposita. 1988, 23, 191-199. [CrossRef]

- Gize, A.; Barnes, H. Organic processes in Mississippi Valley Type ore genesis. 28th International Geological Congress Abstracts. 1989, 557-558.

- Kesler, S.; Jones, H.; Furman, F.; Sassen, R.; Anderson, W.; Kyle, J. Role of crude oil in the genesis of Mississippi Valley Type deposits: evidence from the Cincinnati arch. Geology. 1994, 22, 609-612. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.Y.; Shi, J.X.; Hu, R.Z. Organic matter and its role in mineralization in DaChang antimony deposit, Guizhou, China. Acta Mineralogica Sinica. 1997, 3, 310-315.

- Wang, P.P. Relationship between organic matters and mineralization in the Qinglong antimony deposit, Guizhou province. Value Engineering. 2019, 38, 243-245.

- Yan, S.H.; Yu, J.J.; Zhao, Y.X.; Xu, Z.Z.; Wang A.J.; Teng, R.L. Geology and Geochemistry of the Meiduo Antimony Ore Belt in Northern Tibet: Its Origin and Geodynamic Setting. Acta Geoscientica Sinica. 2004, 25, 541-548.

- Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, W.H. The study of organic ore-forming fluids in the Lannigou gold (mercury, antimony) deposit, Guizhou Province. Mineral Deposits. 1998, 17, 354-361.

- Yin, F.G.; Wan, F.; Tang, W.Q. The disseminated gold deposits in southwestern Guizhou: Mineralization model and its correlation with oil-generation theories. Sedimentary Geology and Tethyan Geology. 2000, 20, 1-8.

- Levine, R. Occurrence of fracture hosted imponite and petroleum fluid inclusion, Quebec city region, Canada. AAPG Bulletin. 1991, 75, 139-153.

- Migdisov, A.A.; Guo, X.; Xu, H.; Williams-Jones, A.E.; Sun, C.J.; Vasyukova, O.; Sugiyama, I.; Fuchs, S.; Pearce, K.; Roback, R. Hydrocarbons as ore fluids. Geochemical Perspectives Letters. 2017, 5, 47-52. [CrossRef]

- Crede, L.S.; Evans, K.A.; Rempel, K.U.; Grice, K.; Sugiyama, I. Gold partitioning between 1-dodecanethiol and brine at elevated temperatures: Implications of Au transport in hydrocarbons for oil-brine ore systems. Chemical Geology. 2019, 504, 28-37. [CrossRef]

- Crede, L.S.; Liu, W.; Evans, K.A.; Rempel, K.U.; Testemale, D.; Brugger, J. Crude oils as ore fluids: An experimental in-situ XAS study of gold partitioning between brine and organic fluid from 25 to 250 ℃. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2019, 244, 352-365. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Robinson, J.; Williams-Jones, A.E. Zinc solubility, speciation and deposition: A role for liquid hydrocarbons as ore fluids for Mississippi Valley Type Zn-Pb deposits. Chemical Geology. 2019, 520, 60-68. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Robinson, J.; Sugiyama, I.; Williams-Jones, A.E. The solubility of palladium (Pd) in crude oil at 150, 200 and 250 ℃ and its application to ore genesis. Chemical Geology. 2020, 531, 119320. [CrossRef]

- Kubrakova, I.V.; Nabiullina, S.N.; Pryazhnikov, D.V.; Kiseleva, M.S. Organic matter as a forming and transporting agent in transfer processes of PGE and gold. Geochemistry International. 2022, 60, 748-756. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, I.; Williams-Jones, A.E. An approach to determining nickel, vanadium and other metal concentrations in crude oil. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2018, 1002, 18-25. [CrossRef]

- Castner, D.G.; Hinds, K.; Grainger, D.W. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy sulfur 2p study of organic thiol and disulfide binding interactions with gold surfaces. Langmuir. 1996, 12, 5083-5086. [CrossRef]

- Кoлпакoва, H.H.; Мапучарянц, Б.О.; Zhang, F.X. Physicochemical conditions responsible for antimony and gold-antimony mineralization. Geology-Geochemistry. 1993, 5, 17-22.

- He, J.; Ma, D.S.; Liu, Y.J. Geochemistry of mineralization in the Zhazixi antimony ore belt on the margin of the Jiangnan old land. Mineral Deposits. 1996, 15, 41-52.

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Norman, C. Controls of mineral parageneses in the system Fe-Sb-S-O. Economic Geology. 1997, 92, 308-324. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.L.; Yuan, Z.Q. Experimental studies of organic-Zn complexes and their stability. Chinese Journal of Geochemistry. 1986, 5, 369-380. [CrossRef]

- Lewan, M. Factors controlling the proportionality of vanadium to nickel in crude oils. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1984, 48, 2231-2238. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, T.H. Metal transport in ore fluids by organic ligand complexation. Organic Acids in Geological Processes. 1994, 319-354. [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.Y.; Rogers, M.A.; Drushel, H.V.; Koons, C.B. Evolution of sulfur compounds in crude oils. AAPG Bulletin. 1974, 58, 2338-2348. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Mankiewicz, P.; Walters, C.; Qian, K.; Phan, N.T.; Madincea, M.E.; Nguyen, P.T. Natural occurrence of higher thiadiamondoids and diamondoidthiols in a deep petroleum reservoir in the Mobile Bay gas field. Organic geochemistry. 2011, 42, 121-133. [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Worden, R.H.; Bottrell, S.H.; Wang, L.; Yang, C. Thermochemical sulphate reduction and the generation of hydrogen sulphide and thiols (mercaptans) in Triassic carbonate reservoirs from the Sichuan Basin, China. Chemical Geology. 2003, 202, 39-57. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.P.; Burklé-Vitzthum, V.; Marquaire, P.M.; Michels, R. Thermal reactions between alkanes and H2S or thiols at high pressure. Journal of analytical and applied pyrolysis. 2013, 103, 307-319. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Katayama, I.; Yamamoto, H.; Misawa, K.; Ishikawa, M.; Rehman, H.U.; Kausar, A.B.; Shiraishi, K. Timing of Himalayan ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism: sinking rate and subduction angle of the Indian continental crust beneath Asia. Journal of Metamorphic Geology. 2003, 21, 589-599. [CrossRef]

- Leech, M.; Singh, S.; Jain, A.; Klemperer, S.; Manickavasagam, R. The onset of India- Asia continental collision: Early, steep subduction required by the timing of UHP metamorphism in the western Himalaya. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2005, 234, 83-97. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.Q.; Qu, X.M.; Yang, Z.S.; Meng, X.J.; Li, Z.Q.; Yang, Z.M.; Zheng, M.P.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Nie, F.J.; Gao, Y.F.; Jiang, S.H.; Li, G.M. Metallogenesis in Tibetan collisional orogenic belt: III. Mineralization in post-collisional extension setting. Mineral Deposits. 2006, 25, 629-651.

- Burchfie, B.C.; Chen, Z.; Hodges, K.V.; Liu, Y.P.; Royden, L.H.; Deng, C.R.; Xu, J.N. The south Tibetan detachment system, Himalayan orogen: extension contemporaneous with and parallel to shortening in a collisional mountain belt. Geological Society of America Special Paper. 1992, 269, 1-41. [CrossRef]

- Schares, E.; Xu, R.H.; Allegere, C.J. U-Pb geochronology of the Gangdese (Transhimalaya) plutonism in the Lhasa-Xizang region, Tibet. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1984, 69, 311-320. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.M.; McKeegan, K.D.; LeFort, P. Detection of inherited monazite in the Manaslu leucogranite by 208Pb/ 232Th ion microprobe dating: Crystallization age and tectonic implications. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1995, 133, 271-282. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.Q.; Gao, Y.F.; Qu, X.M.; Rui, Z.Y.; Mo, X.X. Origin of adakitic intrusives generated during mid-Miocene east-west extension in southern Tibet. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2004, 220, 139-155. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Wang, D.; Yi, J.Z.; Yu, Z.Z.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Li X.X.; Shi, G.W.; Xu J.; Liang, Y.C.; Dou, X.F.; Ren, H. Antimony mineralization and prospecting orientation in the north Himalayan metallogenic belt, Tibet. Earth Science Frontier. 2022, 29, 200-230. [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.J.; Hu, P.; Jiang, S.H.; Li, Z.Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.Z. Type and temporal-spatial distribution of gold and antimony deposits (prospects) in southern Tibet, China. Acta Geologica Sinica. 2005, 3, 373-385.

- Zhai, W.; Sun, X.M.; Yi, J.Z.; Zhang, X.G.; Mo, R.W.; Zhou, F.; Wei, H.X.; Zeng, Q.G. Geology, geochemistry, and genesis of orogenic gold-antimony mineralization in the Himalayan Orogen, South Tibet, China. Ore Geology Reviews. 2014, 58, 68-90. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.W. Characteristics and discussion of stibnite solubility in different solutions. Mineral Resour. 1994, 201, 33-42.

- Williams-Jones, A.E.; Bowell, R.J.; Migdisov, A.A. Gold in solution. Elements. 2009, 5, 281–287. [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.B. A preliminary study on the basic features of global antimony mineralization and the background of mega antimony deposits in the world. Geotectonica et Metallogenia. 1994, 3, 199-208.

- Machel, H.G. Bacterial and thermochemical sulfate reduction in diagenetic settings - old and new insights. Sedimentary Geology. 2001, 140, 143-175. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).