Submitted:

10 January 2024

Posted:

10 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

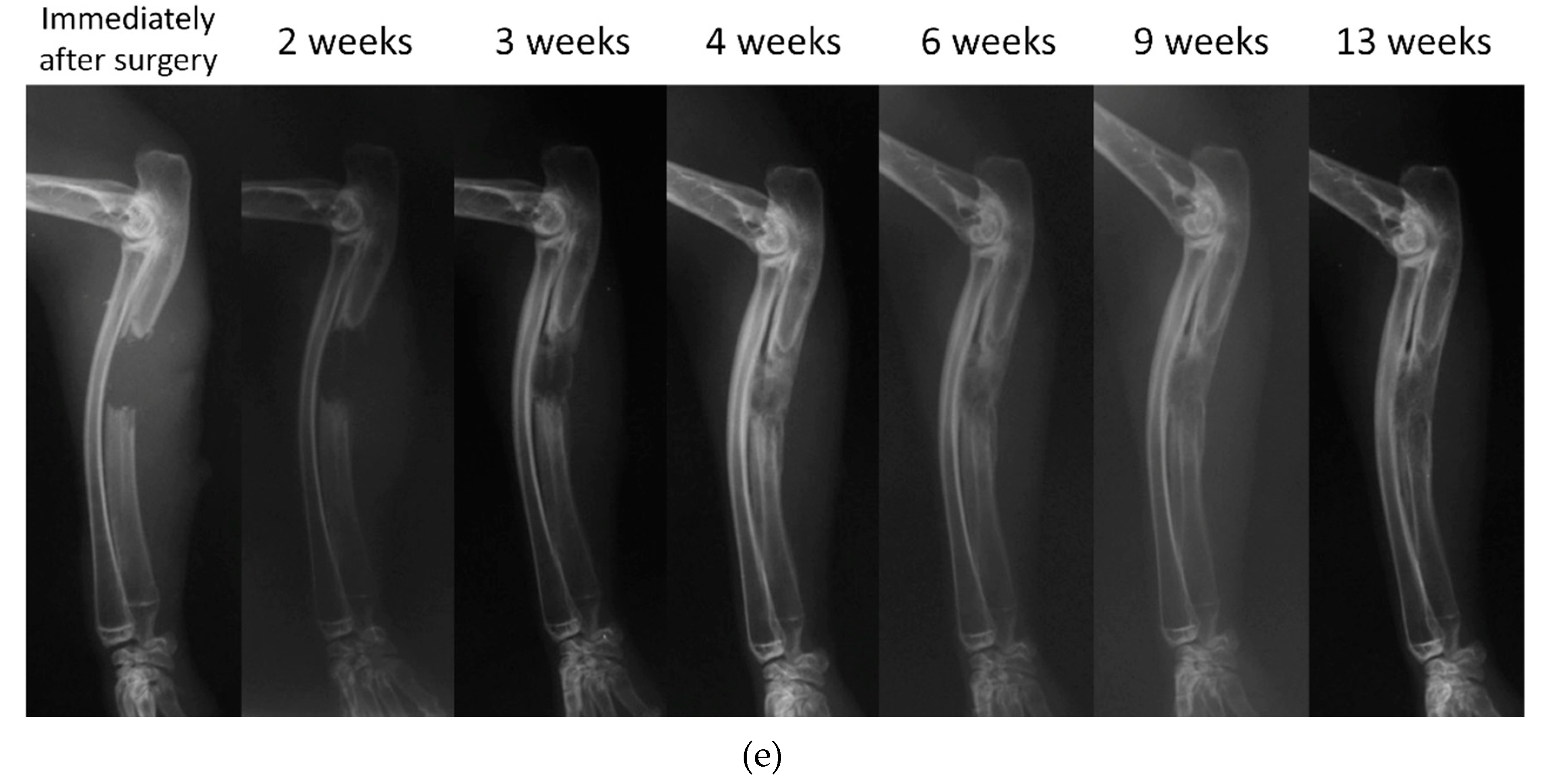

2. Clinical Application of Bone Regeneration Therapy Using Synthetic Bone

3. Research and Development of Biodegradable Polymers

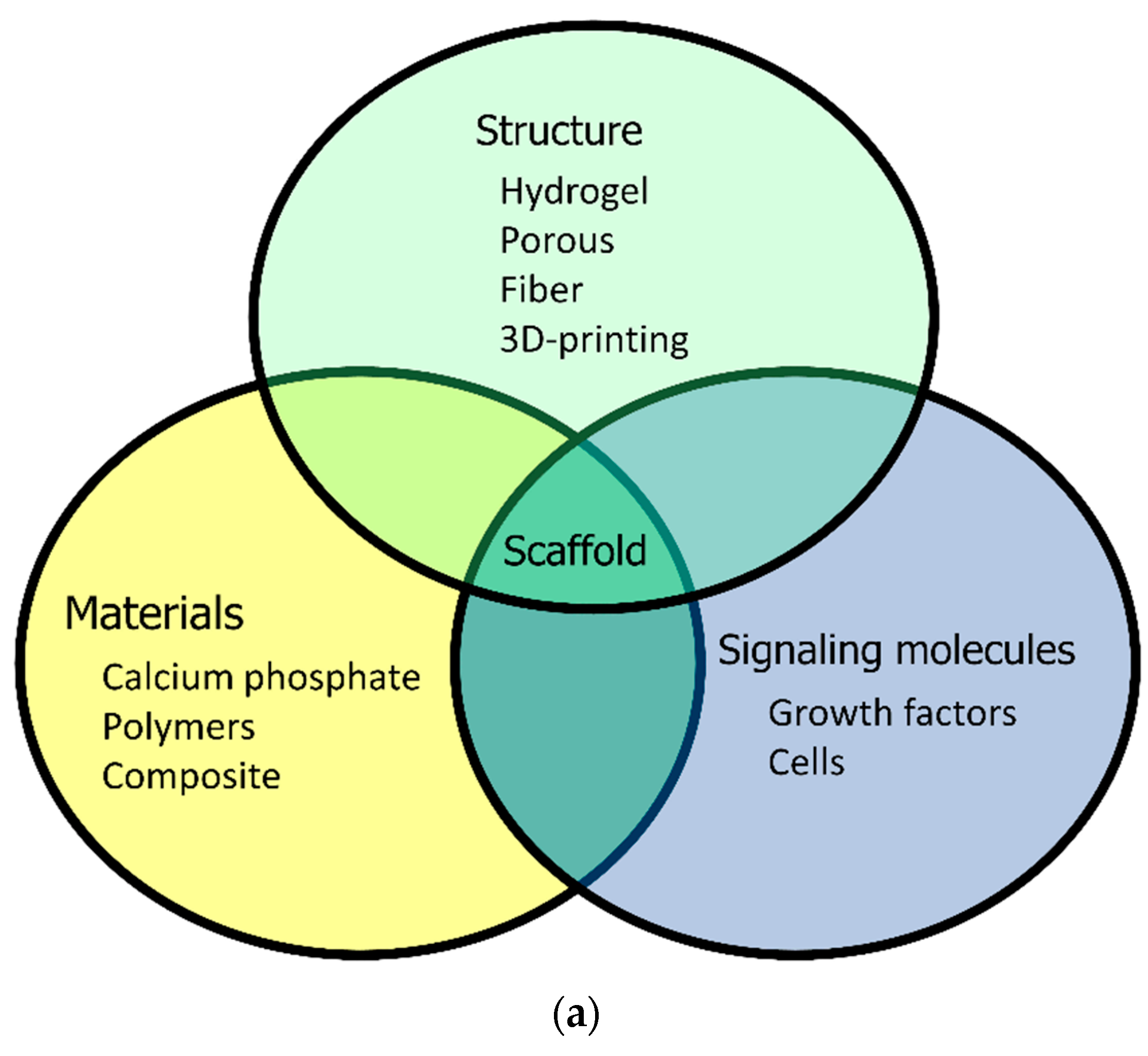

3.1. Material of the Polymer

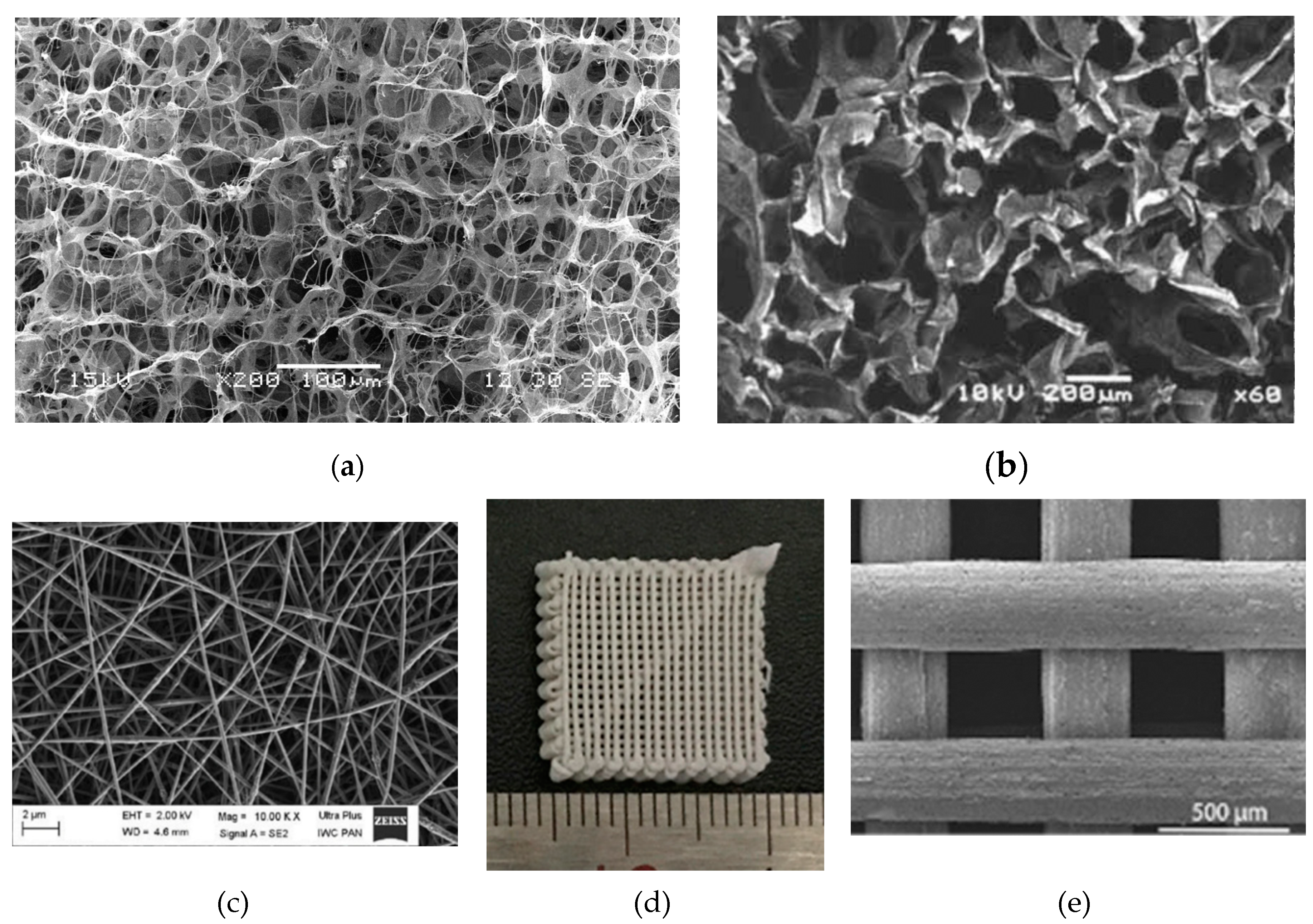

3.2. Three-Dimensional Structure of Synthetic Bonessc

3.3. Cells and Signaling Molecules

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Takahashi, K.; Okita, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from fibroblast cultures. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 3081–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, K.; Ichisaka, T.; Yamanaka, S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007, 448, 313–U1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.G.; Kwon, Y.W.; Lee, T.W.; Park, G.T.; Kim, J.H. Recent advances in stem cell therapeutics and tissue engineering strategies. Biomater. Res. 2018, 22, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M.A.; El-Rosasy, M.A. Hybrid grafting of post-traumatic bone defects using beta-tricalcium phosphate and demineralized bone matrix. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2014, 24, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, R.; Mataliotakis, G.I.; Angoules, A.G.; Kanakaris, N.K.; Giannoudis, P.V. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 2011, 42 Suppl 2, S3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, J.A.; Senunas, L.E.; DeSilva, G.L.; Greenfield, M.L. Autogenous iliac crest bone graft. Complications and functional assessment. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1997, 339, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.B.; Lee, S.Y.; Jeon, D.G. Staged lengthening arthroplasty for pediatric osteosarcoma around the knee. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010, 468, 1660–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrini, M.; Bindiganavile, S.; Say, F.; Colangeli, M.; Campanacci, L.; Depaolis, M.; Ceruso, M.; Donati, D. Is There Benefit to Free Over Pedicled Vascularized Grafts in Augmenting Tibial Intercalary Allograft Constructs? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2017, 475, 1322–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscolo, D.L.; Ayerza, M.A.; Aponte-Tinao, L.A. Massive allograft use in orthopedic oncology. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 2006, 37, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabitsch, K.; Maurer-Ertl, W.; Pirker-Fruhauf, U.; Wibmer, C.; Leithner, A. Intercalary reconstructions with vascularised fibula and allograft after tumour resection in the lower limb. Sarcoma, 2013; 160295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotome, S.; Ae, K.; Okawa, A.; Ishizuki, M.; Morioka, H.; Matsumoto, S.; Nakamura, T.; Abe, S.; Beppu, Y.; Shinomiya, K. Efficacy and safety of porous hydroxyapatite/type 1 collagen composite implantation for bone regeneration: A randomized controlled study. J. Orthop. Sci. 2016, 21, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, N.; Myoui, A.; Tomita, T.; Nakase, T.; Tanaka, J.; Ochi, T.; Yoshikawa, H. Novel hydroxyapatite ceramics with an interconnective porous structure exhibit superior osteoconduction in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002, 59, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Kumagae, Y.; Saito, M.; Chazono, M.; Komaki, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Kitasato, S.; Marumo, K. Bone formation and resorption in patients after implantation of beta-tricalcium phosphate blocks with 60% and 75% porosity in opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 86, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.C.; French, B.G.; Fowler, T.T.; Russell, J.; Poka, A. Induced membrane technique for reconstruction to manage bone loss. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2012, 20, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, J.; Zhu, K.; Cai, T.; Ma, X. Survival, complications and functional outcomes of cemented megaprostheses for high-grade osteosarcoma around the knee. Int. Orthop. 2018, 42, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roddy, E.; DeBaun, M.R.; Daoud-Gray, A.; Yang, Y. P.; Gardner, M.J. Treatment of critical-sized bone defects: clinical and tissue engineering perspectives. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2018, 28, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabello, L.; Pfeiffer, R.; Murphy, G.; Daw, N.C.; Patiño-Garcia, A.; Troisi, R.J.; Hoover, R.N.; Douglass, C.; Schüz, J.; Craft, A.W.; Savage, S.A. Height at diagnosis and birth-weight as risk factors for osteosarcoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2011, 22, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsagozis, P.; Parry, M.; Grimer, R. High complication rate after extendible endoprosthetic replacement of the proximal tibia: a retrospective study of 42 consecutive children. Acta. Orthop. 2018, 89, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimar, J.R. 2nd; Glassman, S.D.; Burkus, J.K.; Pryor, P.W.; Hardacker, J.W.; Carreon, L.Y. Two-year fusion and clinical outcomes in 224 patients treated with a single-level instrumented posterolateral fusion with iliac crest bone graft. Spine J. 2009, 9, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, D.R. The arthrodesis rate in multilevel anterior cervical fusions using autogenous fibula. Spine. 2001, 26, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakoi, A.M.; Iorio, J.A. Iorio; Cahill, P.J. Autologous bone graft harvesting: a review of grafts and surgical techniques. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2015, 99, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C.E.; Martha, J.F.; Kowalski, P.; Wang, D.A.; Bode, R.; Li, L.; Kim, D.H. Prospective evaluation of chronic pain associated with posterior autologous iliac crest bone graft harvest and its effect on postoperative outcome. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2009, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Alencar, P.G; Vieira, I.F. BONE BANKS. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2010, 45, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Vikas, R.; Agrawal, H.S. Allogenic bone grafts in post-traumatic juxta-articular defects: Need for allogenic bone banking. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2017, 73, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, J.; Germain, M.; Winters, M.; Fraser, S.; Duong, A.; Garibaldi, A.; Simunovic, N.; Alsop, D.; Dao, D.; Bessemer, R.; Ayeni, O.R.; Bioburden Steering Committee and Musculoskeletal Tissue Working group. Disinfection of human musculoskeletal allografts in tissue banking: a systematic review. Cell Tissue Bank. 2016, 17, 573-584. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnock, J.M.; Rowan, C.H.; Davidson, H.; Millar, C.; McAlinden, M.G. Improving efficiency of a regional stand alone bone bank. Cell Tissue Bank, 2016, 17, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwitser, E.W.; Jiya, T.U.; Licher, H.G.; van Royen, B.J. Design and management of an orthopaedic bone bank in The Netherlands. Cell Tissue Bank. 2012, 13, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, K.; Inoue, G.; Takahira, N.; Takaso, M. Revision total hip arthroplasty - Salvage procedures using bone allografts in Japan. J. Orthop. Sci. 2017, 22, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, G.; Moghaddam, A. Allograft bone matrix versus synthetic bone graft substitutes. Injury. 2011, 42, S16–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczewski, C.J.; Saul, J.M. Biomaterials for the Delivery of Growth Factors and Other Therapeutic Agents in Tissue Engineering Approaches to Bone Regeneration. Front Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Board, T.N.; Rooney, P.; Eagle, M.J.; Richardson, S.M; Hoyland, J.A. Human decellularized bone scaffolds from aged donors show improved osteoinductive capacity compared to young donor bone. Plos One. 2017, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelis, S.; Virkus, W.; Anderson, D.; Piasecki, P.; Yao, T.K. Functional outcomes of bone graft substitutes for benign bone tumors. Orthopedics. 2004, 27 Suppl 1, S141–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, T.Y.; Wong, H.K. Evolving Treatment Modality of Hand Enchondroma in a Local Hospital: From Autograft to Artificial Bone Substitutes. J. Orthop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2016, 20, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urist, MR. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965, 150, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Stok, J.; Hartholt, K.A.; Schoenmakers, D.A.L.; Arts, J.J.C. The available evidence on demineralised bone matrix in trauma and orthopaedic surgery: A systematic review. Bone Joint Res. 2017, 6, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kombate, N.K.; Walla, A.; Ayouba, G.; Bakriga, B.M.; Dellanh, Y.Y.; Abalo, A.G.; Dossim, A.M. Reconstruction of traumatic bone loss using the induced membrane technique: preliminary results about 11 cases. J. Orthop. 2017, 14, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Tamai, N.; Murase, T.; Myoui, A. Interconnected porous hydroxyapatite ceramics for bone tissue engineering. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2009, 6 Suppl 3, S341–S348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaoka, T.; Yamada, T.; Yuasa, M.; Yoshii, T.; Okawa, A.; Morita, S.; Kozaka, Y.; Hirano, M.; Sotome, S. Biomechanical evaluation of the rabbit tibia after implantation of porous hydroxyapatite/collagen in a rabbit model. J. Orthop. Sci. 2016, 21, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruksakorn, D.; Kongthavonskul, J.; Teeyakasem, P.; Phanphaisarn, A.; Chaiyawat, P.; Klangjorhor, J.; Arpornchayanon, O. Surgical outcomes of extracorporeal irradiation and re-implantation in extremities for high grade osteosarcoma: A retrospective cohort study and a systematic review of the literature. J. Bone Oncol. 2019, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.L.; Vacanti, J.P.; Paige, K.T.; Upton, J.; Vacanti, C.A. Transplantation of chondrocytes utilizing a polymer-cell construct to produce tissue-engineered cartilage in the shape of a human ear. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1997, 100, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, R.; Vacanti, J.P. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993, 260, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

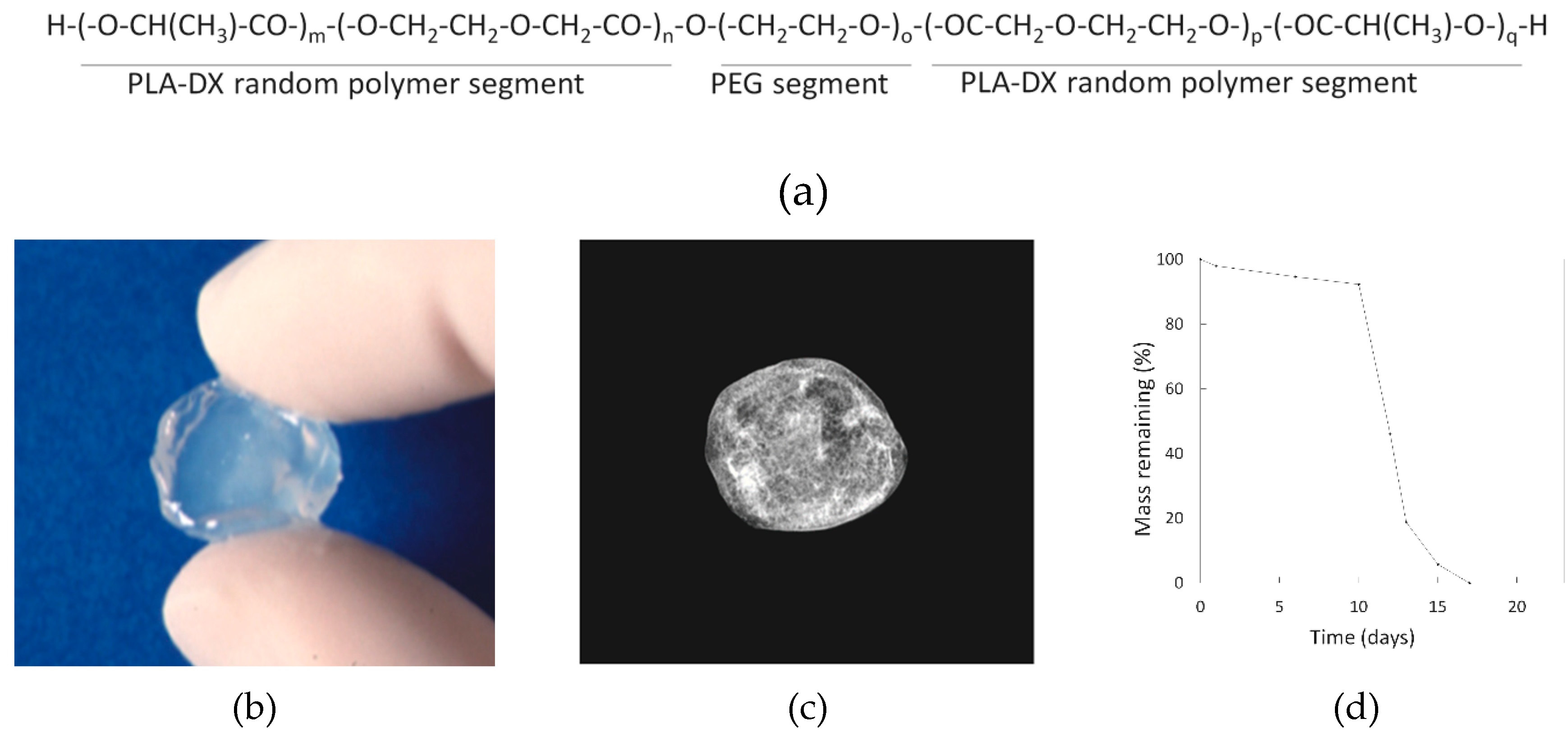

- Aoki, K.; Saito, N. Biodegradable Polymers as Drug Delivery Systems for Bone Regeneration. Pharmaceutics. 2020, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.F.; Sfeir, C.; Kumta, P.N. Novel synthesis strategies for natural polymer and composite biomaterials as potential scaffolds for tissue engineering. Philos. Trans. A Math Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 368, 1981–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, F. Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashedi, I.; Talele, N.; Wang, X.H.; Hinz, B.; Radisic, M.; Keating, A. Collagen scaffold enhances the regenerative properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. PloS One. 2017, 12, e0187348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogenkamp, H.R.; Pot, M.W.; Hafmans, T.G.; Tiemessen, D.M.; Sun, Y.; Oosterwijk, E.; Feitz, W.F.; Daamen, W.F.; van Kuppevelt, T.H. Scaffolds for whole organ tissue engineering: Construction and in vitro evaluation of a seamless, spherical and hollow collagen bladder construct with appendices. Acta Biomater. 2016, 43, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, J.C.; Mehr, M.; Buxton, P.G.; Best, S.M.; Cameron, R.E. Optimising collagen scaffold architecture for enhanced periodontal ligament fibroblast migration. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2018, 29, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstens, M.H.; Chin, M.; Li, X.J. In situ osteogenesis: Regeneration of 10-cm mandibular defect in porcine model using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) and helistat absorbable collagen sponge. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2005, 16, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, J.; Low, S.; Choon, A.T.; Sampath Kumar, T.S.; Ramakrishna, S. Mineralization of osteoblasts with electrospun collagen/hydroxyapatite nanofibers. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 2039–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.A.; Gunn, W.G.; Peister, A.; Prockop, D.J. An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 329, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, G. Three-dimensional hierarchical composite scaffolds consisting of polycaprolactone, beta-tricalcium phosphate, and collagen nanofibers: fabrication, physical properties, and in vitro cell activity for bone tissue regeneration. Biomacromolecules. 2011, 12, 502–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, H.P.; Janda, R.; Clarke, J. Clinical and experimental observations on the use of gelatin sponge or foam. Surgery. 1946, 20, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abada, H.T.; Golzarian, J. Gelatine sponge particles: handling characteristics for endovascular use. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007, 10, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangro, B.; Bilbao, I.; Herrero, I.; Corella, C.; Longo, J.; Beloqui, O.; Ruiz, J.; Zozaya, J.M.; Quiroga, J.; Prieto, J. Partial splenic embolization for the treatment of hypersplenism in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1993, 18, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, S.; Sonohara, S.; Yoshida, M.; Murai, M.; Shimokawa, S.; Fujimoto, R.; Fukushima, S.; Kokubo, S.; Nozaki, K.; Takahashi, K.; Uchida, T.; Yokohama, S.; Sonobe, T. A new recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 carrier for bone regeneration. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 223, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohanizadeh, R.; Swain, M.V.; Mason, R.S. Gelatin sponges (Gelfoam) as a scaffold for osteoblasts. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.K.; Adhikari, J.; Saha, P. Facile fabrication of electrospun regenerated cellulose nanofiber scaffold for potential bone-tissue engineering application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019, 122, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, F.; Atyabi, S.M.; Norouzian, D.; Zandi, M.; Irani, S.; Bakhshi, H. . Polycaprolactone/carboxymethyl chitosan nanofibrous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018, 115, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Peng, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cai, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; OuYang, H.W. The promotion of bone regeneration by nanofibrous hydroxyapatite/chitosan scaffolds by effects on integrin-BMP/Smad signaling pathway in BMSCs. Biomaterials. 2013, 34, 4404–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.J.; Casalini, T.; Hulsart-Billström, G.; Wang, S.; Oommen, O.P.; Salvalaglio, M.; Larsson, S.; Hilborn, J.; Varghese, O.P. Synthetic design of growth factor sequestering extracellular matrix mimetic hydrogel for promoting in vivo bone formation. Biomaterials. 2018, 161, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paidikondala, M.; Wang, S.J.; Hilborn, J.; Larsson, S.; Varghese, O.P. Impact of Hydrogel Cross-Linking Chemistry on the in Vitro and in Vivo Bioactivity of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 2006–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, F.H.; Fishman, J.A.; Daniels, N.; Proimos, J.; Anderson, B.; Carpenter, C.B.; Forrow, L.; Robson, S.C.; Fineberg, H.V. Uncertainty in xenotransplantation: Individual benefit versus collective risk. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, D. Last chance to stop acid think on risks of xenotransplants. Nature. 1998, 391, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhojani-Lynch, T. Late-Onset Inflammatory Response to Hyaluronic Acid Dermal Fillers. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 2017, 5, e1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.W.; Park, M.J.; Lee, S.H. Hyaluronic acid-induced diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: unknown complication induced by a well-known injectable agent. Ann Transl Med, 2019, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, R.J.; Richards, C.; Walker, T. Allergic reactions to oral, surgical and topical bovine collagen. Anaphylactic risk for surgeons. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 24, 257–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, N.; Okada, T.; Horiuchi, H.; Murakami, N.; Takahashi, J.; Nawata, M.; Ota, H.; Nozaki, K.; Takaoka, K. A biodegradable polymer as a cytokine delivery system for inducing bone formation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, K.; Haniu, H.; Kim, Y.A.; Saito, N. The Use of Electrospun Organic and Carbon Nanofibers in Bone Regeneration. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Jiang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Xu, G.; Tong, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; Ji, J.; Shi, P.; Ouyang, H.W. Bi-layer collagen/microporous electrospun nanofiber scaffold improves the osteochondral regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 7236–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Borne, M.P.; Raijmakers, N.J.; Vanlauwe, J.; Victor, J.; de Jong, S.N.; Bellemans, J.; Saris, D.B.; International Cartilage Repair Society. International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) and Oswestry macroscopic cartilage evaluation scores validated for use in Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) and microfracture. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15, 1397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhu, W.; Song, J.; Wei, P.; Yang, F.; Liu, N.; Feng, R. Linear-dendrimer type methoxy-poly (ethylene glycol)-b-poly (epsilon-caprolactone) copolymer micelles for the delivery of curcumin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Z. Short-peptide-based molecular hydrogels: novel gelation strategies and applications for tissue engineering and drug delivery. Nanoscale. 2012, 4, 5259–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, W.; Chou, J.; Wen, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H. Electrospun nanosilicates-based organic/inorganic nanofibers for potential bone tissue engineering. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2018, 172, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Feng, Q. Incorporation of silica nanoparticles to PLGA electrospun fibers for osteogenic differentiation of human osteoblast-like cells. Regen Biomater. 2018, 5, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofejeva, A.; D'Este, M.; Loca, D. Calcium phosphate/polyvinyl alcohol composite hydrogels: A review on the freeze-thawing synthesis approach and applications in regenerative medicine. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 95, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, M.S.; Behzad, T.; Sajkiewicz, P.; Rafienia, M.; Bagheri, R.; Ghasemi-Mobarakeh, L.; Kolbuk, D.; Pahlevanneshan, Z.; Bonakdar, S.H. Development of electrospun poly (vinyl alcohol)-based bionanocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2018, 106, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.S.; Alvarez, V.A. Mechanical properties of polyvinylalcohol/hydroxyapatite cryogel as potential artificial cartilage. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 34, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokugo, A.; Ozeki, M.; Kawakami, O.; Sugimoto, K.; Mushimoto, K.; Morita, S.; Tabata, Y. Augmented bone regeneration activity of platelet-rich plasma by biodegradable gelatin hydrogel. Tissue Eng. 2005, 11, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, F.; Sartore, L.; Moulisova, V.; Cantini, M.; Almici, C.; Bianchetti, A.; Chinello, C.; Dey, K.; Agnelli, S.; Manferdini, C.; Bernardi, S.; Lopomo, N.F.; Sardini, E.; Borsani, E.; Rodella, L.F.; Savoldi, F.; Paganelli, C.; Guizzi, P.; Lisignoli, G.; Magni, F.; Salmeron-Sanchez, M.; Russo, D. 3D gelatin-chitosan hybrid hydrogels combined with human platelet lysate highly support human mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation. J. Tissue Eng. 2019, 10, 2041731419845852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Tsujigiwa, H.; Nagatsuka, H.; Nagai, N.; Yoshinobu, J.; Okano, M.; Fukushima, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Yoshino, T.; Nishizaki, K. Regeneration of rat auditory ossicles using recombinant human BMP-2/collagen composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2005, 73, 133–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Tabata, Y. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in biodegradable sponges composed of gelatin and beta-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials. 2005, 26, 3587–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reneker, D.H.; Chun, I. Nanometre diameter fibres of polymer, produced by electrospinning. Nanotechnology. 1996, 7, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yeo, M.; Ahn, S.; Kang, D.O.; Jang, C.H.; Lee, H.; Park, G.M.; Kim, G.H. Designed hybrid scaffolds consisting of polycaprolactone microstrands and electrospun collagen-nanofibers for bone tissue regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2011, 97, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, L.; Ye, S.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y. Fabrication and Application of Novel Porous Scaffold in Situ-Loaded Graphene Oxide and Osteogenic Peptide by Cryogenic 3D Printing for Repairing Critical-Sized Bone Defect. Molecules. 2019, 24, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, N.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, L. Experimental study of rhBMP-2 chitosan nano-sustained release carrier-loaded PLGA/nHA scaffolds to construct mandibular tissue-engineered bone. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2019, 102, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Fishero, B.A.; Christophel, J.J.; Li, C.J.; Kohli, N.; Lin, Y.; Dighe, A.S.; Cui, Q. Poly(lactic-co-glycolide) polymer constructs cross-linked with human BMP-6 and VEGF protein significantly enhance rat mandible defect repair. Cell and Tissue Research,. [CrossRef]

- Berner, A.; Boerckel, J.D.; Saifzadeh, S.; Steck, R.; Ren, J.; Vaquette, C.; Zhang, J.Q.; Nerlich, M.; Guldberg, R.E.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Woodruff, M.A. Biomimetic tubular nanofiber mesh and platelet rich plasma-mediated delivery of BMP-7 for large bone defect regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 2012, 347, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asatrian, G.; Pham, D.; Hardy, W.R.; James, A.W.; Peault, B. Stem cell technology for bone regeneration: current status and potential applications. Stem Cells Cloning. 2015, 8, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.Z.; Lee, J.H. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Bone Regeneration. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2018, 10, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosario, C.; Rodriguez-Evora, M.; Reyes, R.; Delgado, A.; Evora, C. BMP-2, PDGF-BB, and bone marrow mesenchymal cells in a macroporous beta-TCP scaffold for critical-size bone defect repair in rats. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 10, 045008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussy, Y.; Bertrand Duchesne, M.P.; Gagnon, G. Activation of human platelet-rich plasmas: effect on growth factors release, cell division and in vivo bone formation. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2007, 18, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X.; Du, Y.; Deng, H.; Li, Z. Incorporating platelet-rich plasma into coaxial electrospun nanofibers for bone tissue engineering. Int J Pharm. 2018, 547, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).