Submitted:

08 January 2024

Posted:

10 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. ST-231 and ST-395 Are the Two Prominent Sequence Types

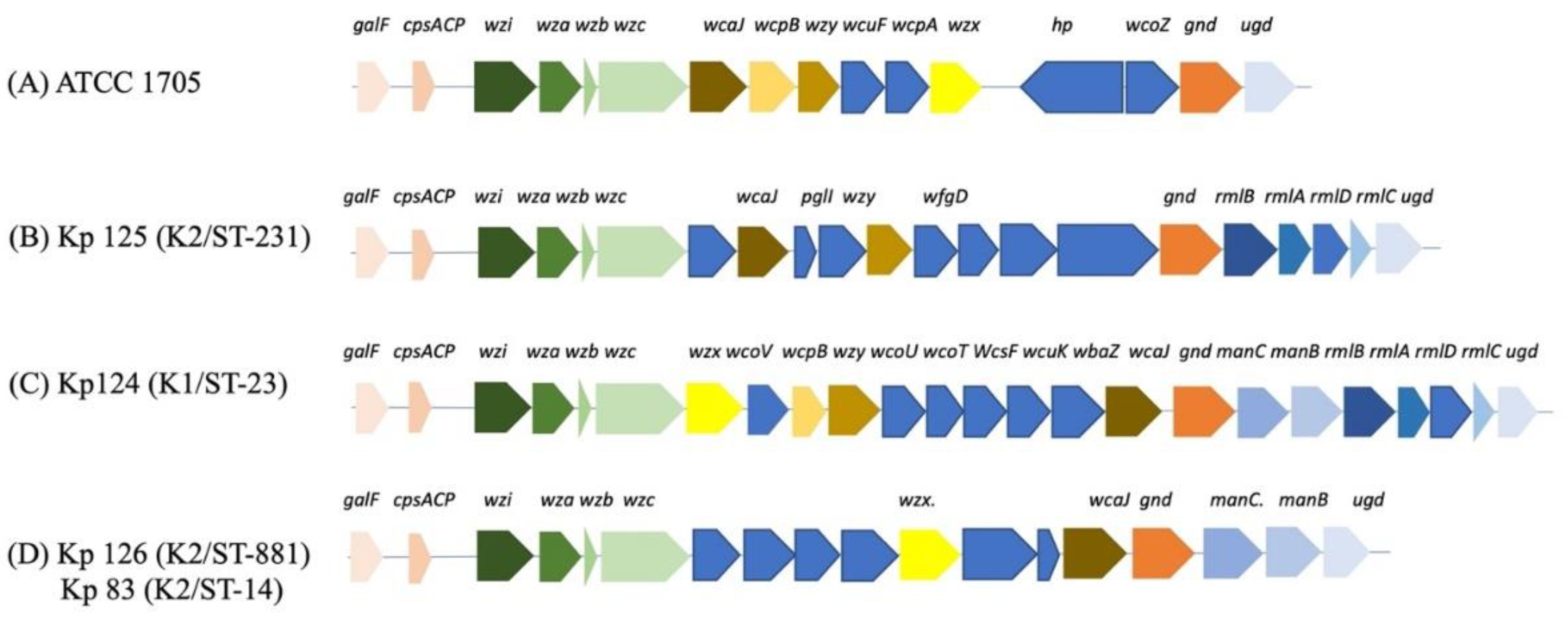

2.2. K-loci Analysis Shows Unique Genetic Arrangement for STs with hvKp

2.3. Plasmid compositions of hvKp K1/ST-23 (Kp124), K2/ST-231 (Kp125), K2/ST-881 (Kp126) and K2/ST-14 (Kp83)

2.4. The Pathogenicity Genes in hvKp Strains

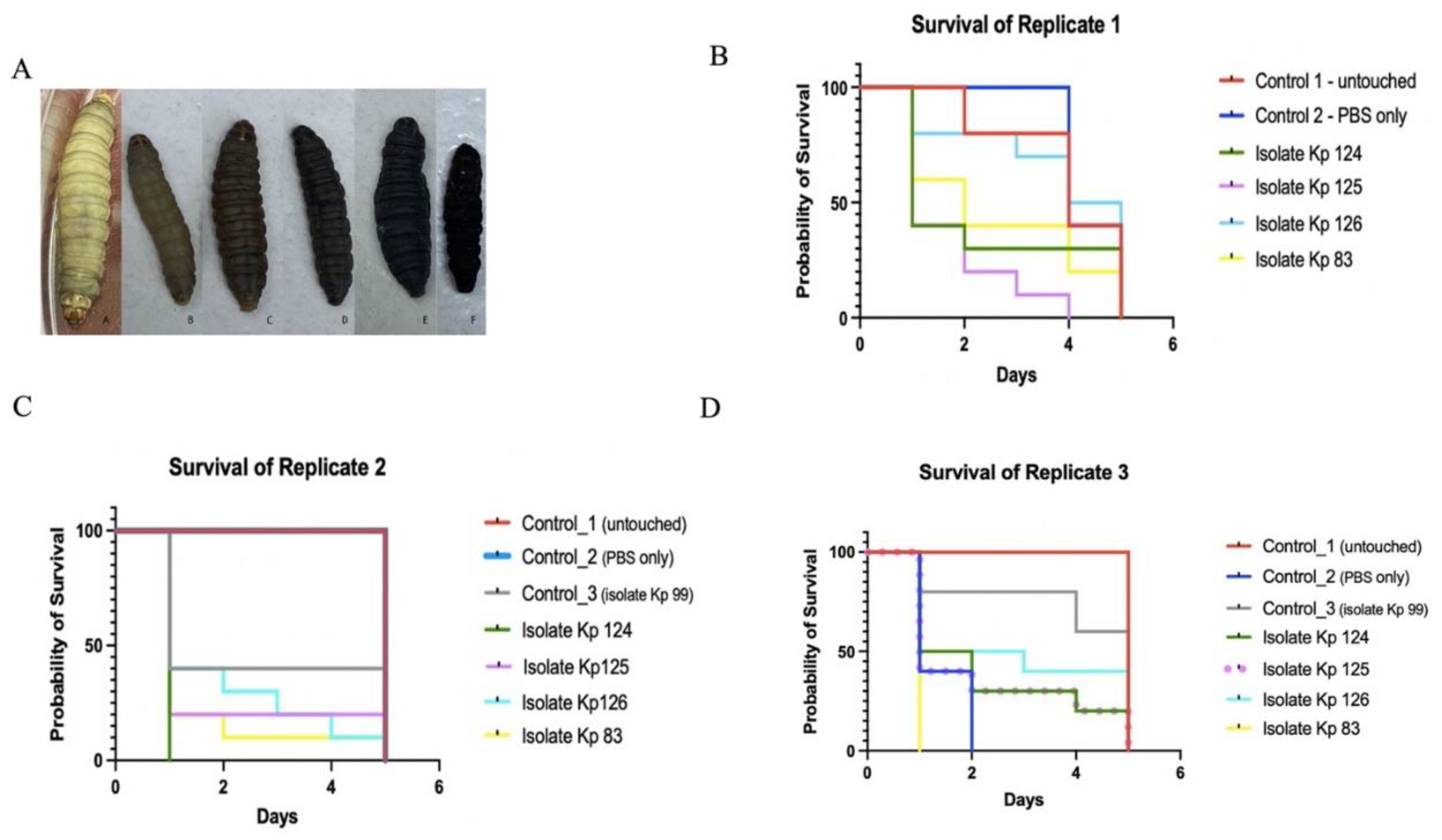

2.5. Clinical hvKp Were Susceptible to Human Serum and Associated with Increased Virulence in G. Mellonella Model

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis Shows Diverse Sequence Types

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates

4.2. String Test for Hypermucoviscosity

4.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

4.4. DNA Extraction and WGS

4.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

4.6. G. mellonella Virulence Assays

4.7. Serum Resistance Assay

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Choby, J. E.; Howard-Anderson, J.; Weiss, D. S. Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae – Clinical and Molecular Perspectives. Journal of Internal Medicine. Blackwell Publishing Ltd March 1, 2020, pp 283–300. [CrossRef]

- Prokesch, B. C.; TeKippe, M.; Kim, J.; Raj, P.; TeKippe, E. M. E.; Greenberg, D. E. Primary Osteomyelitis Caused by Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Lancet Publishing Group 2016, pp e190–e195. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, E. P.; Cervoni, M.; Bernardo, M.; Crivaro, V.; Cuccurullo, S.; Imperi, F.; Zarrilli, R. Molecular Epidemiology and Virulence Profiles of Colistin-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Blood Isolates from the Hospital Agency “Ospedale Dei Colli,” Naples, Italy. Front Microbiol 2018, 9 (JUL). [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, X.; Rao, H.; Yu, H.; Long, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Klebsiella Pneumoniae Bacteremia Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. Frontiers Media S.A. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. R.; Lee, J. H.; Park, K. S.; Jeon, J. H.; Kim, Y. B.; Cha, C. J.; Jeong, B. C.; Lee, S. H. Antimicrobial Resistance of Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Hypervirulence-Associated Determinants, and Resistance Mechanisms. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. Frontiers Media S.A. November 21, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Jing, S.; Ning, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, C. A Wide Clinical Spectrum of Pulmonary Affection in Subjects with Community-Acquired Klebsiella Pneumoniae Liver Abscess (CA-KPLA). Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2023, 29 (1), 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Luo, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, K.; Zeng, T.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Ouyang, J. Clinical and Molecular Characteristics and Antibacterial Strategies of Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Pyogenic Infection. Microbiol Spectr 2023. [CrossRef]

- Russo, T. A.; Olson, R.; MacDonald, U.; Beanan, J.; Davidsona, B. A. Aerobactin, but Not Yersiniabactin, Salmochelin, or Enterobactin, Enables the Growth/Survival of Hypervirulent (Hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella Pneumoniae Ex Vivo and in Vivo. Infect Immun 2015, 83 (8), 3325–3333. [CrossRef]

- Cerdeira, L.; Nakamura-Silva, R.; Oliveira-Silva, M.; Sano, E.; Esposito, F.; Fuga, B.; Moura, Q.; Miranda, C. E. S.; Wyres, K.; Lincopan, N.; Pitondo-Silva, A. A Novel Hypermucoviscous Klebsiella Pneumoniae ST3994-K2 Clone Belonging to Clonal Group 86. Pathog Dis 2021, 79 (8). [CrossRef]

- Catalán-Nájera, J. C.; Garza-Ramos, U.; Barrios-Camacho, H. Hypervirulence and Hypermucoviscosity: Two Different but Complementary Klebsiella Spp. Phenotypes? Virulence. Taylor and Francis Inc. October 3, 2017, pp 1111–1123. [CrossRef]

- Catalán-Nájera, J. C.; Humberto, B. C.; Josefina, D. B.; Alan, S. P.; Rigoberto, H. C.; García-Méndez, J.; Rayo, M. O.; Velázquez-Larios, M. del R.; Vianney, O. N.; Lourdes, G. X.; Celia, A. A.; Jesús, S. S.; Ulises, G. R. Molecular Characterization and Pathogenicity Determination of Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clinical Isolates Serotype K2 in Mexico. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. Elsevier Inc. July 1, 2019, pp 316–319. [CrossRef]

- Bagley, S. T. Habitat Association of Klebsiella Species. Infection Control. 1985. [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.; Thom, K. A.; Masnick, M.; Johnson, J. K.; Harris, A. D.; Morgan, D. J. Frequency of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)–Producing and Non-KPC-Producing Klebsiella Species Contamination of Healthcare Workers and the Environment . Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014, 35 (4). [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M. K.; Mecsas, J. Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Going on the Offense with a Strong Defense. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2016, 80 (3). [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C. P.; Iyadorai, T.; Sears, C.; Roslani, A. C.; Vadivelu, J.; Samudi, C. Presence of Polyketide Synthase (PKS) Gene and Counterpart Virulence Determinants in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Strains Enhances Colorectal Cancer Progression In-Vitro. Microorganisms 2023, 11 (2). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pallares, S.; Mateo-Vargas, M. A.; Rodríguez-Iglesias, M. A.; Galán-Sánchez, F. Molecular Characterization of Consecutive Isolates of OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Changes in the Virulome Using next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Microbes Infect 2023, 105217. [CrossRef]

- Ashurst, J. v.; Dawson, A. Pneumonia, Klebsiella; 2018.

- Larsen, J.; Enright, M. C.; Godoy, D.; Spratt, B. G.; Larsen, A. R.; Skov, R. L. Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Staphylococcus Aureus: Revision of the Gmk Locus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. July 2012, pp 2538–2539. [CrossRef]

- Wick, R. R.; Heinz, E.; Holt, K. E.; Wyres, K. L. Kaptive Web: User-Friendly Capsule and Lipopolysaccharide Serotype Prediction for Klebsiella Genomes. J Clin Microbiol 2018, 56 (6). [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Liu, C.; Xie, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Shen, H.; Cao, X. Genomic and Clinical Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacter Cloacae Complex Isolates Collected in a Chinese Tertiary Hospital during 2013–2021. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, R.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; Ge, H.; Qiao, J.; Li, Y. Global Prevalence, Characteristics, and Future Prospects of IncX3 Plasmids: A Review. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, H.; Zhang, G.; Rehman, T.; Han, J.; Khan, S.; Shafiq, M.; Yang, X.; Yan, Z.; Yang, X. First Report of Blandm-1 Bearing Incx3 Plasmid in Clinically Isolated St11 Klebsiella Pneumoniae from Pakistan. Microorganisms 2021, 9 (5). [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M. F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shafiq, M.; Bilal, H.; Liu, L.; Ma, J.; Gu, P.; Ge, H. Epidemiological Characterization of Colistin and Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a Tertiary: A Hospital from Anhui Province. Infect Drug Resist 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; Garciá-Fernández, A.; Larsen, M. V.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Aarestrup, F. M.; Hasman, H. PlasmidFinder and PMLST: In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58.

- Carattoli, A.; Zankari, E.; Garciá-Fernández, A.; Larsen, M. V.; Lund, O.; Villa, L.; Aarestrup, F. M.; Hasman, H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids Using Plasmidfinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58 (7). [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Manzoor, R.; Tahir, R. A.; Zhang, X.; Qing, H.; Tong, Y. Structural Genomics of Repa, Repb1-Carrying Incfib Family Pa1705-Qnrs, P911021-Teta, and P1642-Teta, Multidrug-Resistant Plasmids from Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Infect Drug Resist 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K. L.; Lam, M. M. C.; Holt, K. E. Population Genomics of Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Tian, L.; Sun, J.; Ou, H. Y.; Qu, H. Whole-Genome-Sequencing Characterization of Bloodstream Infection-Causing Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae of Capsular Serotype K2 and ST374. Virulence 2018, 9 (1), 510–521. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. J.; Lin, T. L.; Chen, Y. H.; Hsu, C. R.; Hsieh, P. F.; Wu, M. C.; Wang, J. T. Capsular Types of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Revisited by Wzc Sequencing. PLoS One 2013, 8 (12). [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. J.; Fang, H. C.; Yang, H. C.; Lin, T. L.; Hsieh, P. F.; Tsai, F. C.; Keynan, Y.; Wang, J. T. Capsular Polysaccharide Synthesis Regions in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Serotype K57 and a New Capsular Serotype. J Clin Microbiol 2008, 46 (7). [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, C.; Roberts, I. S. Structure, Assembly and Regulation of Expression of Capsules in Escherichia Coli. Molecular Microbiology. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Rahn, A.; Drummelsmith, J.; Whitfield, C. Conserved Organization in the Cps Gene Clusters for Expression of Escherichia Coli Group 1 K Antigens: Relationship to the Colanic Acid Biosynthesis Locus and the Cps Genes from Klebsiella Pneumoniae. J Bacteriol 1999, 181 (7). [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Zeng, W.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhou, T. Genetic and Phenotypic Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae from Liver Abscess. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Struve, C.; Roe, C. C.; Stegger, M.; Stahlhut, S. G.; Hansen, D. S.; Engelthaler, D. M.; Andersen, P. S.; Driebe, E. M.; Keim, P.; Krogfelt, K. A. Mapping the Evolution of Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae. mBio 2015, 6 (4). [CrossRef]

- Cubero, M.; Grau, I.; Tubau, F.; Pallarés, R.; Dominguez, M. A.; Liñares, J.; Ardanuy, C. Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clones Causing Bacteraemia in Adults in a Teaching Hospital in Barcelona, Spain (2007-2013). Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2016, 22 (2). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, A.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X.; Xia, X. Outbreak of Plasmid-Mediated NDM-1-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae ST105 among Neonatal Patients in Yunnan, China. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2016, 15 (1). [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. H.; Liu, J. W.; Su, L. H.; Chien, C. C.; Li, C. C.; Yang, K. D. Hypermucoviscosity Associated with Klebsiella Pneumoniae-Mediated Invasive Syndrome: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study in Taiwan. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010, 14 (8). [CrossRef]

- Chung, D. R.; Lee, H.; Park, M. H.; Jung, S. I.; Chang, H. H.; Kim, Y. S.; Son, J. S.; Moon, C.; Kwon, K. T.; Ryu, S. Y.; Shin, S. Y.; Ko, K. S.; Kang, C. I.; Peck, K. R.; Song, J. H. Fecal Carriage of Serotype K1 Klebsiella Pneumoniae ST23 Strains Closely Related to Liver Abscess Isolates in Koreans Living in Korea. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2012, 31 (4), 481–486. [CrossRef]

- Gorrie, C. L.; Mirc Eta, M.; Wick, R. R.; Edwards, D. J.; Thomson, N. R.; Strugnell, R. A.; Pratt, N. F.; Garlick, J. S.; Watson, K. M.; Pilcher, D. V.; McGloughlin, S. A.; Spelman, D. W.; Jenney, A. W. J.; Holt, K. E. Gastrointestinal Carriage Is a Major Reservoir of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Infection in Intensive Care Patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017, 65 (2), 208–215. [CrossRef]

- Shu, H. Y.; Fung, C. P.; Liu, Y. M.; Wu, K. M.; Chen, Y. T.; Li, L. H.; Liu, T. T.; Kirby, R.; Tsai, S. F. Genetic Diversity of Capsular Polysaccharide Biosynthesis in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clinical Isolates. Microbiology (N Y) 2009, 155 (12). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. J.; Siek, K. E.; Johnson, S. J.; Nolan, L. K. DNA Sequence of a ColV Plasmid and Prevalence of Selected Plasmid-Encoded Virulence Genes among Avian Escherichia Coli Strains. J Bacteriol 2006, 188 (2). [CrossRef]

- Dolejska, M.; Vill, L.; Dobiasova, H.; Fortini, D.; Feudi, C.; Carattoli, A. Plasmid Content of a Clinically Relevant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clone from the Czech Republic Producing CTX-M-15 and QnrB1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57 (2). [CrossRef]

- Khajanchi, B. K.; Hasan, N. A.; Choi, S. Y.; Han, J.; Zhao, S.; Colwell, R. R.; Cerniglia, C. E.; Foley, S. L. Comparative Genomic Analysis and Characterization of Incompatibility Group FIB Plasmid Encoded Virulence Factors of Salmonella Enterica Isolated from Food Sources. BMC Genomics 2017, 18 (1). [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, T.; Tellevik, M. G.; Kommedal, Ø.; Lindemann, P. C.; Moyo, S. J.; Janice, J.; Blomberg, B.; Samuelsen, Ø.; Langeland, N. Horizontal Plasmid Transfer among Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolates Is the Key Factor for Dissemination of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases among Children in Tanzania. mSphere 2020, 5 (4). [CrossRef]

- Lutgring, J. D.; Zhu, W.; De Man, T. J. B.; Avillan, J. J.; Anderson, K. F.; Lonsway, D. R.; Rowe, L. A.; Batra, D.; Rasheed, J. K.; Limbago, B. M. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Enterobacteriaceae Producing Oxacillinase-48-like Carbapenemases, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2018, 24 (4). [CrossRef]

- Ragupathi, N. K. D.; Bakthavatchalam, Y. D.; Mathur, P.; Pragasam, A. K.; Walia, K.; Ohri, V. C.; Veeraraghavan, B. Plasmid Profiles among Some ESKAPE Pathogens in a Tertiary Care Centre in South India. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2019, 149 (2). [CrossRef]

- Diancourt, L.; Passet, V.; Verhoef, J.; Grimont, P. A. D.; Brisse, S. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Nosocomial Isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43 (8). [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Hegerle, N.; Nkeze, J.; Sen, S.; Jamindar, S.; Nasrin, S.; Sen, S.; Permala-Booth, J.; Sinclair, J.; Tapia, M. D.; Johnson, J. K.; Mamadou, S.; Thaden, J. T.; Fowler, V. G.; Aguilar, A.; Terán, E.; Decre, D.; Morel, F.; Krogfelt, K. A.; Brauner, A.; Protonotariou, E.; Christaki, E.; Shindo, Y.; Lin, Y. T.; Kwa, A. L.; Shakoor, S.; Singh-Moodley, A.; Perovic, O.; Jacobs, J.; Lunguya, O.; Simon, R.; Cross, A. S.; Tennant, S. M. The Diversity of Lipopolysaccharide (O) and Capsular Polysaccharide (K) Antigens of Invasive Klebsiella Pneumoniae in a Multi-Country Collection. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Han, R.; Yin, D.; Jiang, B.; Ding, L.; Guo, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Hu, F. A Nationwide Genomic Study of Clinical Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carrying Bla OXA-232 and RmtF in China . Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11 (3). [CrossRef]

- Mancini, S.; Poirel, L.; Tritten, M. L.; Lienhard, R.; Bassi, C.; Nordmann, P. Emergence of an MDR Klebsiella Pneumoniae ST231 Producing OXA-232 and RmtF in Switzerland. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Potron, A.; Kalpoe, J.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. European Dissemination of a Single OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clone. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2011, 17 (12). [CrossRef]

- Gijón, D.; Tedim, A. P.; Valverde, A.; Rodríguez, I.; Morosini, M.-I.; Coque, T. M.; Manrique, M.; Pareja, E.; Tobes, R.; Ruiz-Garbajosa, P.; Cantón, R. Early OXA-48-Producing Enterobacterales Isolates Recovered in a Spanish Hospital Reveal a Complex Introduction Dominated by Sequence Type 11 (ST11) and ST405 Klebsiella Pneumoniae Clones . mSphere 2020, 5 (2). [CrossRef]

- Al-Agamy, M. H.; Aljallal, A.; Radwan, H. H.; Shibl, A. M. Characterization of Carbapenemases, ESBLs, and Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Determinants in Carbapenem-Insensitive Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Riyadh Hospitals. J Infect Public Health 2018, 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Alsharapy, S. A.; Gharout-Sait, A.; Muggeo, A.; Guillard, T.; Cholley, P.; Brasme, L.; Bertrand, X.; Moghram, G. S.; Touati, A.; De Champs, C. Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Clinical Isolates in Al Thawra University Hospital, Sana’a, Yemen. Microbial Drug Resistance 2020, 26 (3). [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Potron, A.; Nordmann, P. OXA-48-like Carbapenemases: The Phantom Menace. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2012, 67 (7). [CrossRef]

- López-Camacho, E.; Paño-Pardo, J. R.; Ruiz-Carrascoso, G.; Wesselink, J. J.; Lusa-Bernal, S.; Ramos-Ruiz, R.; Ovalle, S.; Gómez-Gil, R.; Pérez-Blanco, V.; Pérez-Vázquez, M.; Gómez-Puertas, P.; Mingorance, J. Population Structure of OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae ST405 Isolates during a Hospital Outbreak Characterised by Genomic Typing. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018, 15. [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, H. H.; Dolapçı, İ.; Avcı, M.; Tekeli, A. The Emergence of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Sequence Type 395 Non-Susceptible to Carbapenems and Colistin from Turkey. Indian J Med Microbiol 2023, 46. [CrossRef]

- Sandfort, M.; Hans, J. B.; Fischer, M. A.; Reichert, F.; Cremanns, M.; Eisfeld, J.; Pfeifer, Y.; Heck, A.; Eckmanns, T.; Werner, G.; Gatermann, S.; Haller, S.; Pfennigwerth, N. Increase in NDM-1 and NDM-1/OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Germany Associated with the War in Ukraine, 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27 (50). [CrossRef]

- Ménard, G.; Rouillon, A.; Cattoir, V.; Donnio, P. Y. Galleria Mellonella as a Suitable Model of Bacterial Infection: Past, Present and Future. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. Frontiers Media S.A. December 22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Decré, D.; Verdet, C.; Emirian, A.; Le Gourrierec, T.; Petit, J. C.; Offenstadt, G.; Maury, E.; Brisse, S.; Arlet, G. Emerging Severe and Fatal Infections Due to Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Two University Hospitals in France. J Clin Microbiol 2011, 49 (8). [CrossRef]

- Konagaya, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Suda, T.; Tsuda, Y.; Isogai, J.; Murayama, H.; Arakawa, Y.; Ogino, H. Ruptured Emphysematous Prostatic Abscess Caused by K1-ST23 Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae Presenting as Brain Abscesses: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Nomoto, H.; Harada, S.; Suzuki, M.; Yomono, K.; Yokochi, R.; Hagino, N.; Nakamoto, T.; Moriyama, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Kutsuna, S.; Ohmagari, N. Infection with Capsular Genotype K1-ST23 Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolates in Japan after a Stay in East Asia: Two Cases and a Literature Review. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2021, 27 (10). [CrossRef]

- Shon, A. S.; Bajwa, R. P. S.; Russo, T. A. Hypervirulent (Hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella Pneumoniae: A New and Dangerous Breed. Virulence 2013, 4 (2). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Torres, V. V. L.; Liu, H.; Rocker, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Bi, W.; Lin, J.; Strugnell, R. A.; Zhang, S.; Lithgow, T.; Zhou, T.; Cao, J. An Outbreak of Carbapenem-Resistant and Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumoniae in an Intensive Care Unit of a Major Teaching Hospital in Wenzhou, China. Front Public Health 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bugla-Płoskońska, G.; Kiersnowski, A.; Futoma-Kołoch, B.; Doroszkiewicz, W. Killing of Gram-Negative Bacteria with Normal Human Serum and Normal Bovine Serum: Use Of Lysozyme and Complement Proteins in the Death Of Salmonella Strains O48. Microb Ecol 2009, 58 (2). [CrossRef]

- Tichaczek-Goska, D.; Witkowska, D.; Cisowska, A.; Jankowski, S.; Hendrich, A. B. The Bactericidal Activity of Normal Human Serum against Enterobacteriaceae Rods with Lipopolysaccharides Possessing O-Antigens Composed of Mannan. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2012, 21 (3).

- Benge, G. R. Bactericidal Activity of Human Serum against Strains of Klebsiella from Different Sources. J Med Microbiol 1988, 27 (1). [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K. M.; Chiu, S. K.; Lin, C. L.; Huang, L. Y.; Tsai, Y. K.; Chang, J. C.; Lin, J. C.; Chang, F. Y.; Siu, L. K. Surface Antigens Contribute Differently to the Pathophysiological Features in Serotype K1 and K2 Klebsiella Pneumoniae Strains Isolated from Liver Abscesses. Gut Pathog 2016, 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- Tomas, J. M.; Benedi, V. J.; Ciurana, B.; Jofre, J. Role of Capsule and O Antigen in Resistance of Klebsiella Pneumoniae to Serum Bactericidal Activity. Infect Immun 1986, 54 (1). [CrossRef]

- DeLeo, F. R.; Kobayashi, S. D.; Porter, A. R.; Freedman, B.; Dorward, D. W.; Chen, L.; Kreiswirth, B. N. Survival of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Sequence Type 258 in Human Blood. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61 (4). [CrossRef]

- Kumabe, A.; Kenzaka, T. String Test of Hypervirulent Klebsiella Pneumonia. QJM. Oxford University Press December 1, 2014, p 1053. [CrossRef]

- Ruangpan, L. Chapter 3. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Test and Determination of Antimicrobial Resistant Bacteria. Laboratory manual of standardized methods for antimicrobial sensitivity tests for bacteria isolated from aquatic animals and environment 2004, No. Mic.

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing A CLSI Supplement for Global Application. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2020.

- Bolger, A. M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (15), 2114–2120. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A. M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (15). [CrossRef]

- Nurk, S.; Bankevich, A.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.; Korobeynikov, A.; Lapidus, A.; Prjibelsky, A.; Pyshkin, A.; Sirotkin, A.; Sirotkin, Y.; Stepanauskas, R.; McLean, J.; Lasken, R.; Clingenpeel, S. R.; Woyke, T.; Tesler, G.; Alekseyev, M. A.; Pevzner, P. A. Assembling Genomes and Mini-Metagenomes from Highly Chimeric Reads. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); 2013; Vol. 7821 LNBI. [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid Prokaryotic Genome Annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (14). [CrossRef]

- Carver, T.; Harris, S. R.; Berriman, M.; Parkhill, J.; McQuillan, J. A. Artemis: An Integrated Platform for Visualization and Analysis of High-Throughput Sequence-Based Experimental Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28 (4). [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S. F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E. W.; Lipman, D. J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J Mol Biol 1990, 215 (3). [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, R.; Barrett, T.; Beck, J.; Benson, D. A.; Bollin, C.; Bolton, E.; Bourexis, D.; Brister, J. R.; Bryant, S. H.; Canese, K.; Cavanaugh, M.; Charowhas, C.; Clark, K.; Dondoshansky, I.; Feolo, M.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Funk, K.; Geer, L. Y.; Gorelenkov, V.; Graeff, A.; Hlavina, W.; Holmes, B.; Johnson, M.; Kattman, B.; Khotomlianski, V.; Kimchi, A.; Kimelman, M.; Kimura, M.; Kitts, P.; Klimke, W.; Kotliarov, A.; Krasnov, S.; Kuznetsov, A.; Landrum, M. J.; Landsman, D.; Lathrop, S.; Lee, J. M.; Leubsdorf, C.; Lu, Z.; Madden, T. L.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Malheiro, A.; Meric, P.; Karsch-Mizrachi, I.; Mnev, A.; Murphy, T.; Orris, R.; Ostell, J.; O’Sullivan, C.; Palanigobu, V.; Panchenko, A. R.; Phan, L.; Pierov, B.; Pruitt, K. D.; Rodarmer, K.; Sayers, E. W.; Schneider, V.; Schoch, C. L.; Schuler, G. D.; Sherry, S. T.; Siyan, K.; Soboleva, A.; Soussov, V.; Starchenko, G.; Tatusova, T. A.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Todorov, K.; Trawick, B. W.; Vakatov, D.; Ward, M.; Yaschenko, E.; Zasypkin, A.; Zbicz, K. Database Resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46 (D1). [CrossRef]

- Wick, R. R.; Heinz, E.; Holt, K. E.; Wyres, K. L. Kaptive Web: User-Friendly Capsule and Lipopolysaccharide Serotype Prediction for Klebsiella Genomes. J Clin Microbiol 2018, 56 (6). [CrossRef]

- Lam, M. M. C.; Wick, R. R.; Watts, S. C.; Cerdeira, L. T.; Wyres, K. L.; Holt, K. E. A Genomic Surveillance Framework and Genotyping Tool for Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Its Related Species Complex. Nat Commun 2021, 12 (1). [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.; Xie, Y.; Bi, D.; Sun, J.; Li, J.; Tai, C.; Deng, Z.; Ou, H. Y. ICEberg 2.0: An Updated Database of Bacterial Integrative and Conjugative Elements. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47 (D1), D660–D665. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M. v.; Cosentino, S.; Rasmussen, S.; Friis, C.; Hasman, H.; Marvig, R. L.; Jelsbak, L.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Ussery, D. W.; Aarestrup, F. M.; Lund, O. Multilocus Sequence Typing of Total-Genome-Sequenced Bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50 (4). [CrossRef]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R. S.; Ruppe, E.; Roberts, M. C.; Schwarz, S.; Cattoir, V.; Philippon, A.; Allesoe, R. L.; Rebelo, A. R.; Florensa, A. F.; Fagelhauer, L.; Chakraborty, T.; Neumann, B.; Werner, G.; Bender, J. K.; Stingl, K.; Nguyen, M.; Coppens, J.; Xavier, B. B.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Westh, H.; Pinholt, M.; Anjum, M. F.; Duggett, N. A.; Kempf, I.; Nykäsenoja, S.; Olkkola, S.; Wieczorek, K.; Amaro, A.; Clemente, L.; Mossong, J.; Losch, S.; Ragimbeau, C.; Lund, O.; Aarestrup, F. M. ResFinder 4.0 for Predictions of Phenotypes from Genotypes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2020, 75 (12). [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B. P.; Raphenya, A. R.; Lau, T. T. Y.; Tsang, K. K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A. L. v.; Cheng, A. A.; Liu, S.; Min, S. Y.; Miroshnichenko, A.; Tran, H. K.; Werfalli, R. E.; Nasir, J. A.; Oloni, M.; Speicher, D. J.; Florescu, A.; Singh, B.; Faltyn, M.; Hernandez-Koutoucheva, A.; Sharma, A. N.; Bordeleau, E.; Pawlowski, A. C.; Zubyk, H. L.; Dooley, D.; Griffiths, E.; Maguire, F.; Winsor, G. L.; Beiko, R. G.; Brinkman, F. S. L.; Hsiao, W. W. L.; Domselaar, G. v.; McArthur, A. G. CARD 2020: Antibiotic Resistome Surveillance with the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48 (D1). [CrossRef]

- Kaas, R. S.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Aarestrup, F. M.; Lund, O. Solving the Problem of Comparing Whole Bacterial Genomes across Different Sequencing Platforms. PLoS One 2014, 9 (8). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. Mol Biol Evol 2016, 33 (7). [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R Core Team (2014). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/. 2014.

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (ITOL): An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Bioinformatics 2007, 23 (1). [CrossRef]

- Jesper, L.; C, E. M.; Daniel, G.; G, S. B.; R, L. A.; L, S. R. Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Staphylococcus Aureus: Revision of the Gmk Locus. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50 (7), 2538–2539. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H. A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 2015, 32 (1), 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Smith, D. K.; Zhu, H.; Guan, Y.; Lam, T. T.-Y. Ggtree: An r Package for Visualization and Annotation of Phylogenetic Trees with Their Covariates and Other Associated Data. Methods Ecol Evol 2017, 8 (1), 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D. T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B. Q.; Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35 (2), 518–522. [CrossRef]

- Harding, C. R.; Schroeder, G. N.; Collins, J. W.; Frankel, G. Use of Galleria Mellonella as a Model Organism to Study Legionella Pneumophila Infection. J Vis Exp 2013, No. 81. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, S.; Volz, M. S.; Fiedler, T.; Podschun, R.; Schneider, T. Klebsiella Pneumoniae– Induced Liver Abscesses, Germany. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2014. [CrossRef]

| Isolate (Kp) | Sequence type | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 102, 106, 110, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 118, 125 | 231 | 32 |

| 103, 104, 108, 111,121, 123 | 395 | 19 |

| 124 and 128 | 23 | 6 |

| 105 and 117 | 405 | 6 |

| 100 | 13 | 1 |

| 101 | 45 | 1 |

| 107 | 1714 | 1 |

| 109 | 280 | 1 |

| 119 | 1710 | 1 |

| 120 | 147 | 1 |

| 122 | 37 | 1 |

| 126 | 881 | 1 |

| 127 | 11 | 1 |

| 83 | 14 | 1 |

| 129 | 86 | 1 |

| Isolate | Serotype | ST | Source | Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kp 83 | K2 | 14 | Urine | D |

| Kp 124 | K1 | 23 | Pus | C |

| Kp 125 | K2 | 231 | Urine | B |

| Kp 126 | K2 | 881 | Urine | A |

| Strain name, serotype, and ST | Plasmid | Resistance Phenotype | Resistance genotype | Resistance Mechanism | Drug Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kp 83 K2/ST-14 | IncFIA (HI1) 204,189 |

ESBL, | tet (B), tetR | Antibiotic efflux, target alteration | Tetracycline |

| AMP, TZP, FEP, CTX, IMP, CAZ, CIP | |||||

| IncFIB(K) 208,191 bp |

catI | Antibiotic inactivation | Phenicol | ||

| drfA12 | Antibiotic target replacement | Folate pathway antagonist | |||

| aadA2 | Antibiotic inactivation | Aminoglycoside | |||

| qacEdelta1 | Efflux | Disinfecting agents and intercalating dyes | |||

| sul1 | Target replacement | Sulfonamides | |||

| mphA | Antibiotic inactivation | Macrolides | |||

| IncFIB(pNDM-Mar) 372 826 bp |

OXA-1 | Antibiotic inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin | ||

| NDM-1 | Antibiotic inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin | |||

| QnrB1 | Target protection | Quinolones | |||

| catI | Antibiotic inactivation | Phenicol | |||

| CTX-M-15 | Antibiotic inactivation | Cephalosporin | |||

| AAC(6’)-lb-cr6 | Antibiotic inactivation | Quinolones, Aminoglycoside | |||

| IncR 68 649 bp |

tet(D) | Efflux | Tetracycline | ||

| sul2 | Target replacement | Sulfonamides | |||

| drfA14 | Target replacement | Folate pathway antagonist | |||

| SHV-2 | Inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin | |||

| QnrS1 | Target protection | Quinolones | |||

| APH(6)-Id | Inactivation | Aminoglycoside | |||

| Kp125 K2/ST-231 | ColKP3 5095 bp |

KPC | OXA-181 | Antibiotic Inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin |

| IncFIB(pQil) 115.300 bp |

AMP, TZP, FEP, CTX, CAZ | KPC-3 | Antibiotic Inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin | |

| TEM-1 | Antibiotic Inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin | |||

| APH(3’)-la | Antibiotic Inactivation | Aminoglycoside | |||

| IncFII(pAMA1167-NDM-5) 175,879 bp |

sul1 | Target replacement | Sulfonamide | ||

| qacEdelta1 | Efflux | Disinfecting agents and intercalating dyes | |||

| aadA5 | Antibiotic Inactivation | Aminoglycoside | |||

| NDM-5 | Antibiotic Inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin | |||

| mphA | Antibiotic Inactivation | Macrolides | |||

| drA17 | Target replacement | Folate pathway antagonist | |||

| tetR | Antibiotic efflux, target alteration | Tetracylines | |||

| Kp124 K1/ST-23 | IncFIB(pQil) 115.300 bp |

ESBL/KPC | KPC-3 | Antibiotic Inactivation | Carbapenem, Cephalosporin |

| AMP, TZP, FEP, CTX, FOX, CAZ | |||||

| Kp126 K2/ST-881 | IncFIB(K) 208,191 bp |

ESBL, | catI | Antibiotic inactivation | Phenicol |

| AMP, FEP, CTX, IMP, CAZ, CIP | drfA12 | Antibiotic target replacement | Folate pathway antagonist | ||

| aadA2 | Antibiotic inactivation | Aminoglycoside | |||

| qacEdelta1 | Efflux | Disinfecting agents and intercalating dyes | |||

| sul1 | Target replacement | Sulfonamides | |||

| mphA | Antibiotic inactivation | Macrolides |

| Antibiotic | Abbreviation | Disk content (μg) | Zone diameter breakpoints (mm) | ||

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | |||

| Ampicilin | AMP | 10 | ≥ 17 | 14-16 | ≤ 13 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | TZP | 110 | ≥ 21 | 18-20 | ≤ 17 |

| Cefepime | FEP | 30 | ≥ 25 | 19-24 | ≤ 18 |

| Cefotaxime | CTX | 30 | ≥ 26 | 23-25 | ≤ 22 |

| Cefoxitin | FOX | 30 | ≥18 | 15-17 | ≤ 14 |

| Ceftazidime | CAZ | 30 | ≥ 21 | 18-20 | ≤ 17 |

| Imipenem | IMP | 10 | ≥ 23 | 20-22 | ≤ 19 |

| Meropenem | MEM | 10 | ≥ 23 | 20-22 | ≤ 18 |

| Gentamicin | CN | 30 | ≥ 15 | 13-14 | ≤ 12 |

| Amikacin | AK | 10 | ≥ 17 | 15-16 | ≤ 14 |

| Ciprofloxacin | CIP | 5 | ≥ 31 | 21-30 | ≤ 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).