Submitted:

09 January 2024

Posted:

09 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

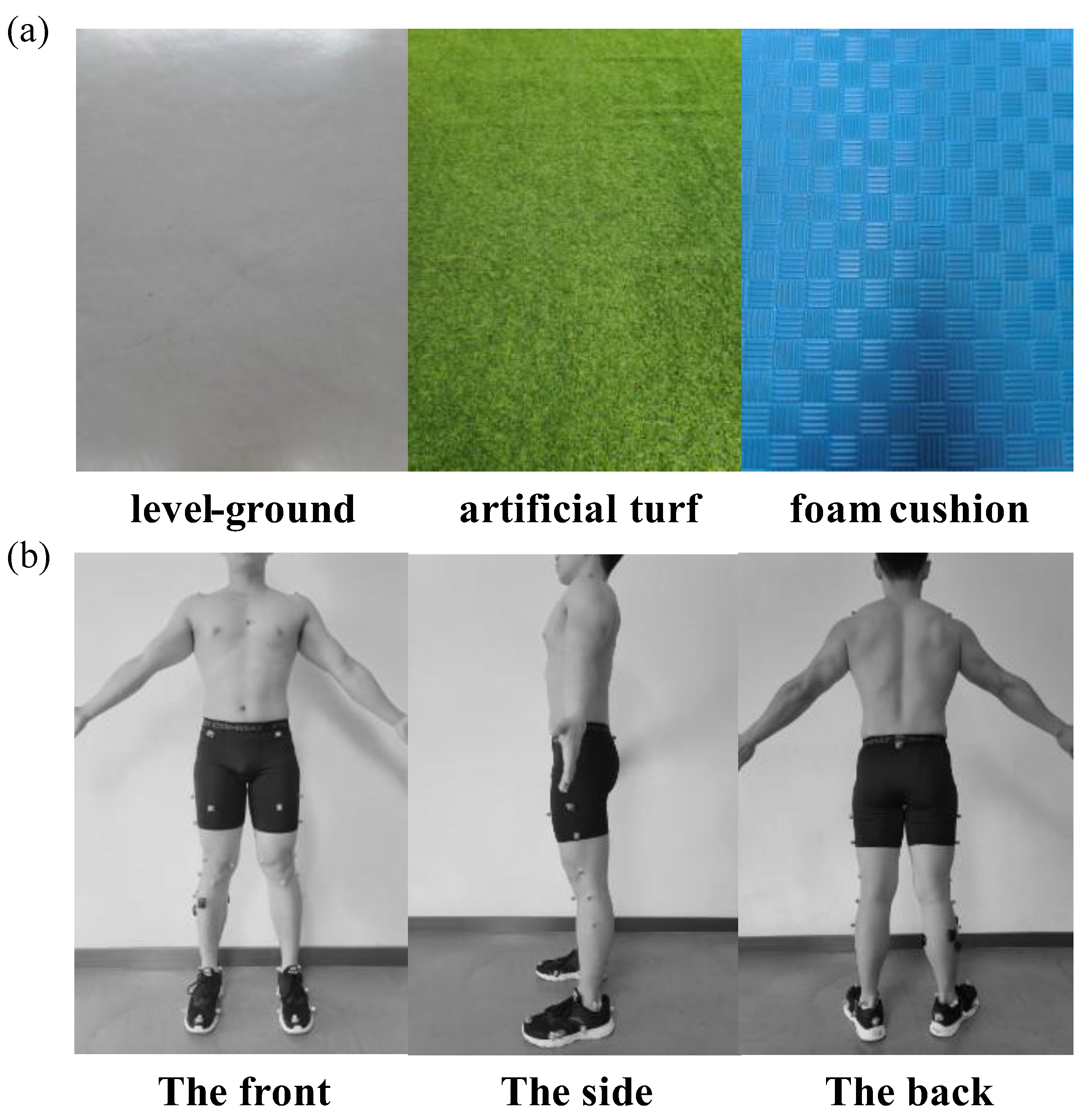

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Neuromuscular Training Program

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Protocol

2.5. Data Processing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Model Validation and Sensitivity

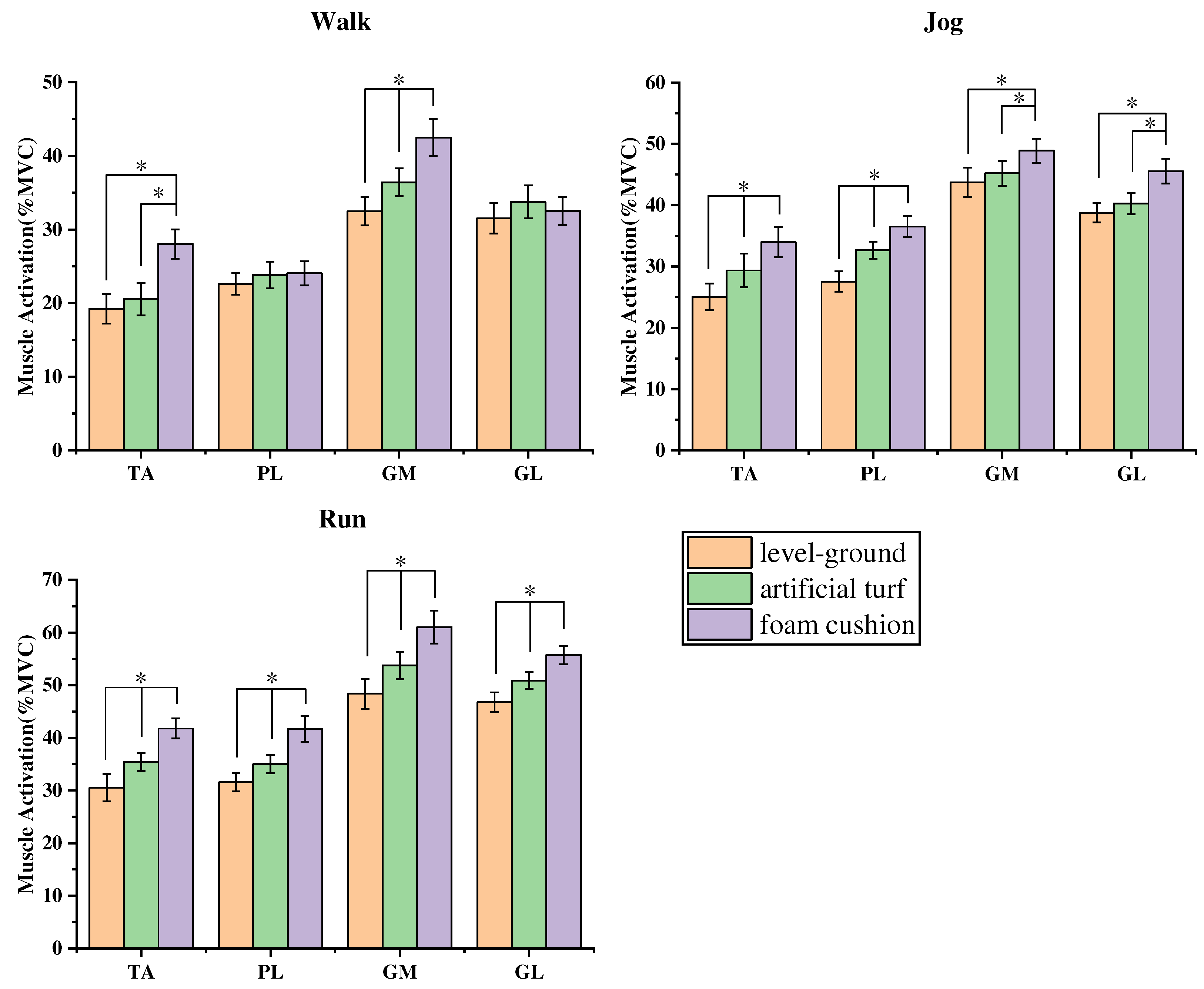

3.2. Comparative results of non-parametric tests of muscle activation

3.3. Results of the SNPM1d comparison of kinematic and kinetic

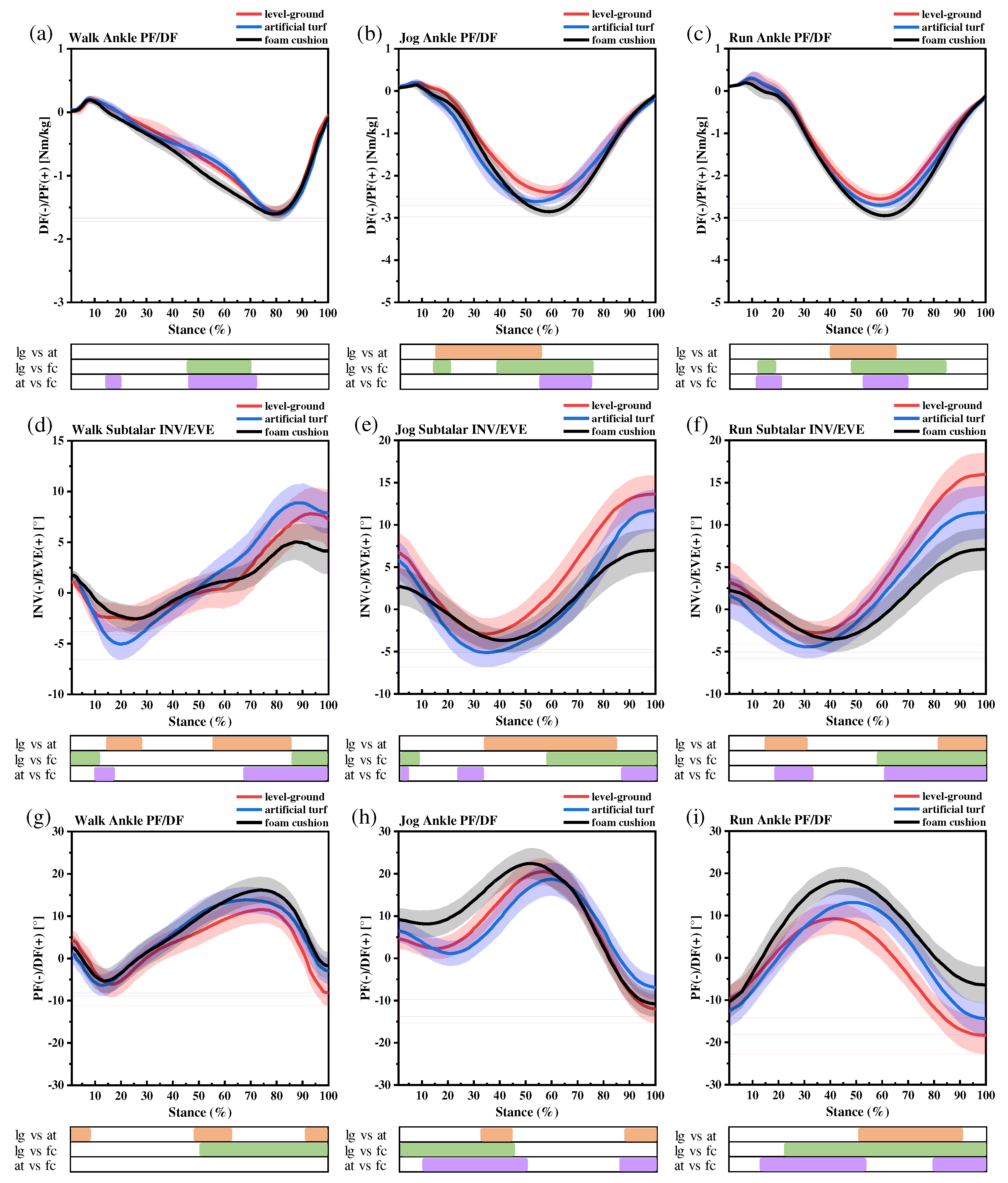

3.3.1. Ankle moments

3.3.2. Subtalar joint INV and EVE

3.3.3. Ankle sagittal plane kinematics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Health, N.I.o. Concurrent and aerobic exercise training promote similar benefits in body composition and metabolic profiles in obese adolescents.

- Paluska, S.A. An overview of hip injuries in running. Sports medicine 2005, 35, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.-W.; Wong, D.W.-C.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, M. Foot arch deformation and plantar fascia loading during running with rearfoot strike and forefoot strike: a dynamic finite element analysis. Journal of Biomechanics 2019, 83, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrabano, V.; Horisberger, M.; Russell, I.; Dougall, H.; Hintermann, B. Etiology of ankle osteoarthritis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 2009, 467, 1800–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, M.M.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Marshall, S.W.; Wikstrom, E.A. Epidemiology of ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability. Journal of athletic training 2019, 54, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Mei, Q.; Xiang, L.; Fernandez, J.; Gu, Y. Differences in the locomotion biomechanics and dynamic postural control between individuals with chronic ankle instability and copers: a systematic review. Sports Biomechanics 2022, 21, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahunt, E.; Coughlan, G.F.; Caulfield, B.; Nightingale, E.J.; Lin, C.-W.C.; Hiller, C.E. Inclusion criteria when investigating insufficiencies in chronic ankle instability. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2010, 42, 2106–2121. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, J.; Sullivan, S.J.; Schneiders, A.G. Evidence of sensorimotor deficits in functional ankle instability: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2010, 13, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, T.W.; Needle, A.R.; Delahunt, E. Prevention of lateral ankle sprains. Journal of Athletic Training 2019, 54, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, H.; Needle, A.R.; Swanik, C.B.; Gustavsen, G.A.; Kaminski, T.W. Role of external prophylactic support in restricting accessory ankle motion after exercise. Foot & Ankle International 2012, 33, 862–869. [Google Scholar]

- Schiftan, G.S.; Ross, L.A.; Hahne, A.J. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of science and medicine in sport 2015, 18, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herb, C.C.; Hertel, J. Current concepts on the pathophysiology and management of recurrent ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports 2014, 2, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Oh, S.; Kwon, J.W. Effect of plyometric versus ankle stability exercises on lower limb biomechanics in taekwondo demonstration athletes with functional ankle instability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vriend, I.; Gouttebarge, V.; Van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E. Neuromuscular training is effective to prevent ankle sprains in a sporting population: a meta-analysis translating evidence into optimal prevention strategies. Journal of ISAKOS 2016, 1, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, R.; Willems, T.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Roosen, P. Influence of balance surface on ankle stabilizing muscle activity in subjects with chronic ankle instability. Journal of rehabilitation medicine 2015, 47, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.-Y.; Han, J.-H.; Sung, Y.-H. Effects of ankle strengthening exercise program on an unstable supporting surface on proprioception and balance in adults with functional ankle instability. Journal of exercise rehabilitation 2018, 14, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behm, D.G.; Muehlbauer, T.; Kibele, A.; Granacher, U. Effects of strength training using unstable surfaces on strength, power and balance performance across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine 2015, 45, 1645–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-C.; Roche, J.L.; Steed, D.P.; Musolino, M.C.; Marchetti, G.F.; Furman, G.R.; Redfern, M.S.; Whitney, S.L. Test-retest reliability of postural stability on two different foam pads. Journal of nature and science 2015, 1, e43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.; Migel, K.G.; Kim, H.; Wikstrom, E.A. Acute vibration feedback during gait reduces mechanical ankle joint loading in chronic ankle instability patients. Gait & Posture 2021, 90, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Delp, S.L.; Anderson, F.C.; Arnold, A.S.; Loan, P.; Habib, A.; John, C.T.; Guendelman, E.; Thelen, D.G. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering 2007, 54, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.; Hicks, J.L.; Uchida, T.K.; Habib, A.; Dembia, C.L.; Dunne, J.J.; Ong, C.F.; DeMers, M.S.; Rajagopal, A.; Millard, M. OpenSim: Simulating musculoskeletal dynamics and neuromuscular control to study human and animal movement. PLoS computational biology 2018, 14, e1006223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Donahue, M.; Docherty, C. Development of the identification of functional ankle instability (IdFAI). Foot & Ankle International 2012, 33, 755–763. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Q.; Fernandez, J.; Xiang, L.; Gao, Z.; Yu, P.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. Dataset of lower extremity joint angles, moments and forces in distance running. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, S.L.; Anderson, F.C.; Arnold, A.S.; Loan, P.; Habib, A.; John, C.T.; Guendelman, E.; Thelen, D.G. OpenSim: open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering 2007, 54, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Xuan, R.; Song, Y.; Bíró, I.; Liang, M.; Gu, Y. Effect of heel lift insoles on lower extremity muscle activation and joint work during barbell squats. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, K.; Delahunt, E.; Caulfield, B. Ankle function during gait in patients with chronic ankle instability compared to controls. Clinical biomechanics 2006, 21, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinn, L.; Dicharry, J.; Hertel, J. Ankle kinematics of individuals with chronic ankle instability while walking and jogging on a treadmill in shoes. Physical Therapy in Sport 2013, 14, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Shinkoda, K. Differences of muscle co-contraction of the ankle joint between young and elderly adults during dynamic postural control at different speeds. Journal of physiological anthropology 2017, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Mei, Q.; Peng, H.-T.; Li, J.; Wei, C.; Gu, Y. A comparative study on loadings of the lower extremity during deep squat in Asian and Caucasian individuals via OpenSim musculoskeletal modelling. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Robinson, M.A. Zero- vs. one-dimensional, parametric vs. non-parametric, and confidence interval vs. hypothesis testing procedures in one-dimensional biomechanical trajectory analysis. J Biomech 2015, 48, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, K.M.; DeMers, M.S.; Schwartz, M.H.; Delp, S.L. Compressive tibiofemoral force during crouch gait. Gait & posture 2012, 35, 556–560. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.I.; Docherty, C.L.; Simon, J.; Klossner, J.; Schrader, J. Ankle strength and force sense after a progressive, 6-week strength-training program in people with functional ankle instability. Journal of athletic training 2012, 47, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloak, R.; Nevill, A.; Day, S.; Wyon, M. Six-week combined vibration and wobble board training on balance and stability in footballers with functional ankle instability. Clinical journal of sport medicine 2013, 23, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.-Y.; Jankaew, A.; Lin, C.-F. Effects of plyometric and balance training on neuromuscular control of recreational athletes with functional ankle instability: a randomized controlled laboratory study. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadi, H.; Rajabi, R.; Karimizadeh Ardakani, M. The effect of six weeks of neuromuscular training on joint position sense and lower extremity function in male athletes with functional ankle instability. Journal of Exercise Science and Medicine 2017, 9, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, H.; Rajabi, R.; Alizadeh, M.H.; Jamshidi, A. Effect of six weeks neuromuscular training on dynamic postural control and lower extremity function in male athletes with functional ankle instability. Studies in sport medicine 2014, 5, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, M.; Hsu, W.-L.; Woollacott, M.H.; Chou, L.-S. Ankle dorsiflexor strength relates to the ability to restore balance during a backward support surface translation. Gait & posture 2013, 38, 812–817. [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone, B.J.; Ronsky, J.L.; Meeuwisse, W.H.; Zernicke, R.F. Ankle kinematics and muscle activity in functional ankle instability. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2014, 24, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feger, M.A.; Donovan, L.; Hart, J.M.; Hertel, J. Lower extremity muscle activation during functional exercises in patients with and without chronic ankle instability. PM&R 2014, 6, 602–611. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, L.A.B.; Pereira, W.M.; Rossi, L.P.; Kerpers, I.I.; de Paula Jr, A.R.; Oliveira, C.S. Analysis of electromyographic activity of ankle muscles on stable and unstable surfaces with eyes open and closed. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2011, 15, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, J.S.; Schaefer de Araújo, F.G.; Santos, G.M.; Keighley, J.; Dos Santos, M.J. Changes in postural control after a ball-kicking balance exercise in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Journal of athletic training 2016, 51, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams III, D.B.; Murray, N.G.; Powell, D.W. Athletes who train on unstable compared to stable surfaces exhibit unique postural control strategies in response to balance perturbations. Journal of sport and health science 2016, 5, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, A.; Pezarat-Correia, P.; Esteves, J.; Fernandes, O. The influence of a balance training program on the electromyographic latency of the ankle musculature in subjects with no history of ankle injury. Physical Therapy in sport 2011, 12, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.; Nielsen, R.O.; Rasmussen, S.; Sørensen, H. Comparisons of increases in knee and ankle joint moments following an increase in running speed from 8 to 12 to 16 km· h− 1. Clinical Biomechanics 2014, 29, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigo, C.A.; Merlo, A.; Brambilla, C.; Mazzoli, D. Balanced Foot Dorsiflexion Requires a Coordinated Activity of the Tibialis Anterior and the Extensor Digitorum Longus: A Musculoskeletal Modelling Study. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerapong, P.; Hume, P.A.; Kolt, G.S. Stretching: mechanisms and benefits for sport performance and injury prevention. Physical Therapy Reviews 2004, 9, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, M.C.; McKeon, P.O. Joint mobilization improves spatiotemporal postural control and range of motion in those with chronic ankle instability. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2011, 29, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnett, C.R.; Hanish, M.J.; Wheeler, T.J.; Miriovsky, D.J.; Danielson, E.L.; Barr, J.B.; Grindstaff, T.L. Ankle dorsiflexion range of motion influences dynamic balance in individuals with chronic ankle instability. International journal of sports physical therapy 2013, 8, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, M.C.; Staton, G.S.; McKeon, J.M.M.; Mattacola, C.G.; McKeon, P.O. Dorsiflexion and dynamic postural control deficits are present in those with chronic ankle instability. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2012, 15, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, M.C.; Farwell, K.E.; Gaven, S.L.; Weinhandl, J.T. Weight-bearing dorsiflexion range of motion and landing biomechanics in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Journal of athletic training 2015, 50, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J.M.; Golshani, A.; Gargac, S.; Goswami, T. Biomechanics of the ankle joint and clinical outcomes of total ankle replacement. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials 2008, 1, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, G.B.; Pinerola, J.J.; Caturano, R.W. Invertor vs. evertor peak torque and power deficiencies associated with lateral ankle ligament injury. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 1997, 26, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, A.; Swanik, C.; Thomas, S.; Glutting, J.; Knight, C.; Kaminski, T.W. Differences in lateral drop jumps from an unknown height among individuals with functional ankle instability. Journal of athletic training 2013, 48, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMers, M.S.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. Preparatory co-activation of the ankle muscles may prevent ankle inversion injuries. Journal of biomechanics 2017, 52, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.T.; McInnis, K.C.; Borg-Stein, J. Ankle sprains: evaluation, rehabilitation, and prevention. Current sports medicine reports 2019, 18, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Franco, N.; Martínez-López, E.J.; Lomas-Vega, R.; Hita-Contreras, F.; Osuna-Pérez, M.C.; Martínez-Amat, A. Short-term effects of proprioceptive training with unstable platform on athletes' stabilometry. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2013, 27, 2189–2197. [Google Scholar]

| Program | Number of times | Group | Interval | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 15 | 3 | 20s | 3min |

| DF | 15 | 3 | 20s | 3min |

| lunge | 16 | 2 | 60s | 3min |

| vertical jump | 15 | 2 | 60s | 3min |

| lateral jump | 15 | 2 | 60s | 3min |

| Joint Moments (Nm/kg) | LG | AT | FC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walk | Ankle PF | 1.58±0.10 | 1.62±0.06 | 1.61±0.12 |

| Jog | Ankle PF | 2.41±0.16bc | 2.65±0.09ac | 2.87±0.12ab |

| Run | Ankle PF | 2.51±0.12bc | 2.72±0.10ac | 2.96±0.17ab |

| Joint kinematics (°) | LG | AT | FC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walk | Subtalar EVE | 8.10±2.67 | 9.01±1.86c | 5.14±1.84b | |

| Subtalar INV | 3.14±1.54 | 5.12±1.52 | 2.82±1.01 | ||

| Subtalar mobility | 11.24±3.08 | 14.13±2.40c | 7.96±2.10b | ||

| Jog | Subtalar EVE | 13.63±1.34c | 11.72±1.86c | 7.20±2.47ab | |

| Subtalar INV | 2.97±0.94b | 5.15±0.93a | 3.88±1.37 | ||

| Subtalar mobility | 16.60±1.64c | 16.87±2.08c | 11.09±2.83ab | ||

| Run | Subtalar EVE | 15.97±1.59bc | 11.47±3.12a | 7.19±2.49a | |

| Subtalar INV | 2.84±1.55 | 4.51±1.29 | 3.65±1.49 | ||

| Subtalar mobility | 18.81±2.22c | 15.98±3.37c | 10.84±2.90ab | ||

| Joint kinematics (°) | LG | AT | FC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walk | Ankle DF | 10.10±2.73c | 13.18±2.35 | 15.14±2.58a | |

| Ankle PF | 6.64±2.18 | 7.37±1.88 | 5.05±1.79 | ||

| Ankle mobility | 17.74±3.49 | 20.55±3.01 | 20.19±3.14 | ||

| Jog | Ankle DF | 18.58±2.61c | 16.71±2.87c | 22.52±2.67ab | |

| Ankle PF | 12.78±2.69b | 7.90±2.36ac | 12.04±2.54b | ||

| Ankle mobility | 31.36±3.75b | 24.61±3.72ac | 34.56±3.69b | ||

| Run | Ankle DF | 7.14±2.73bc | 13.25±3.04ac | 18.44±2.62ab | |

| Ankle PF | 18.41±2.70c | 14.49±2.74c | 8.38±2.98ab | ||

| Ankle mobility | 25.55±3.84 | 27.74±4.09 | 26.82±3.97 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).