Submitted:

05 January 2024

Posted:

08 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

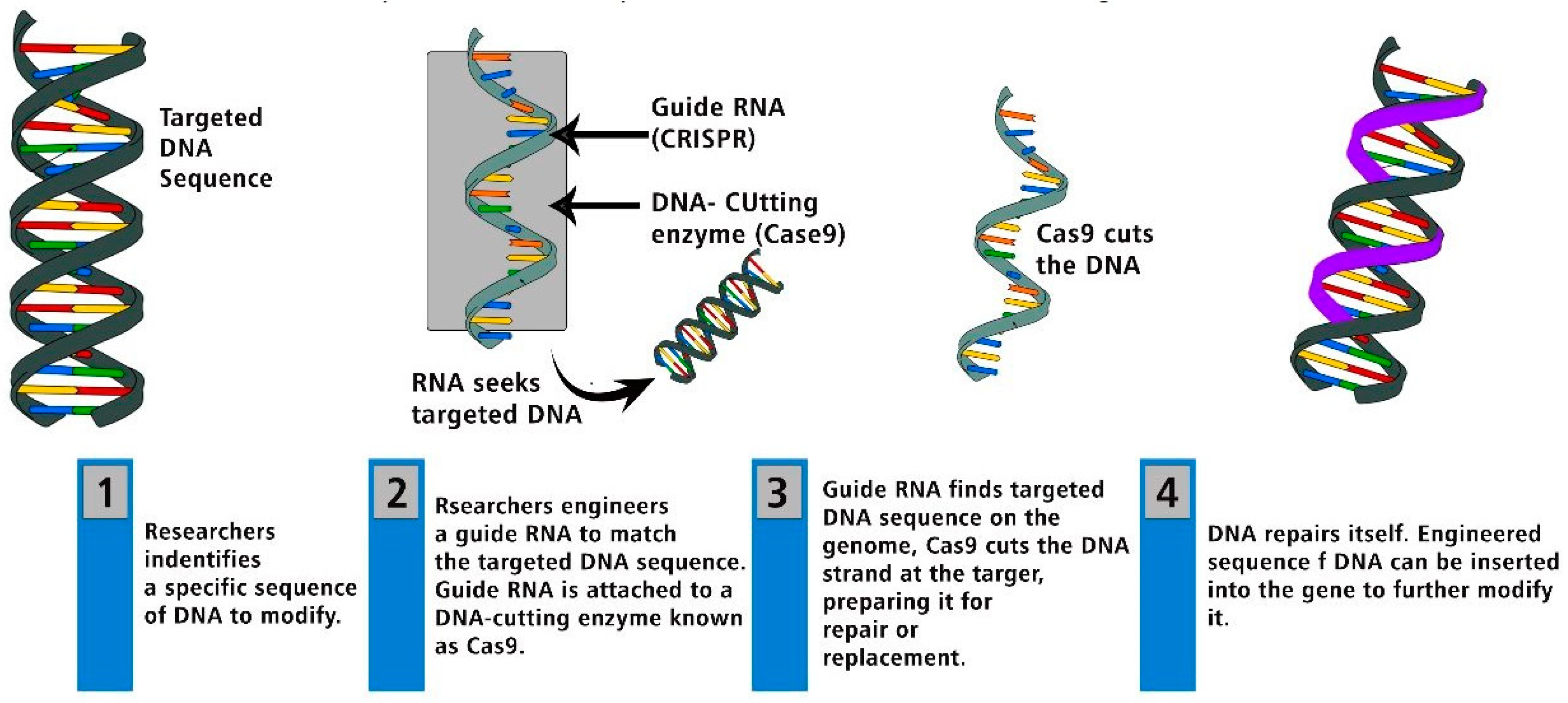

Introduction

History, Development and Scientific Advancement

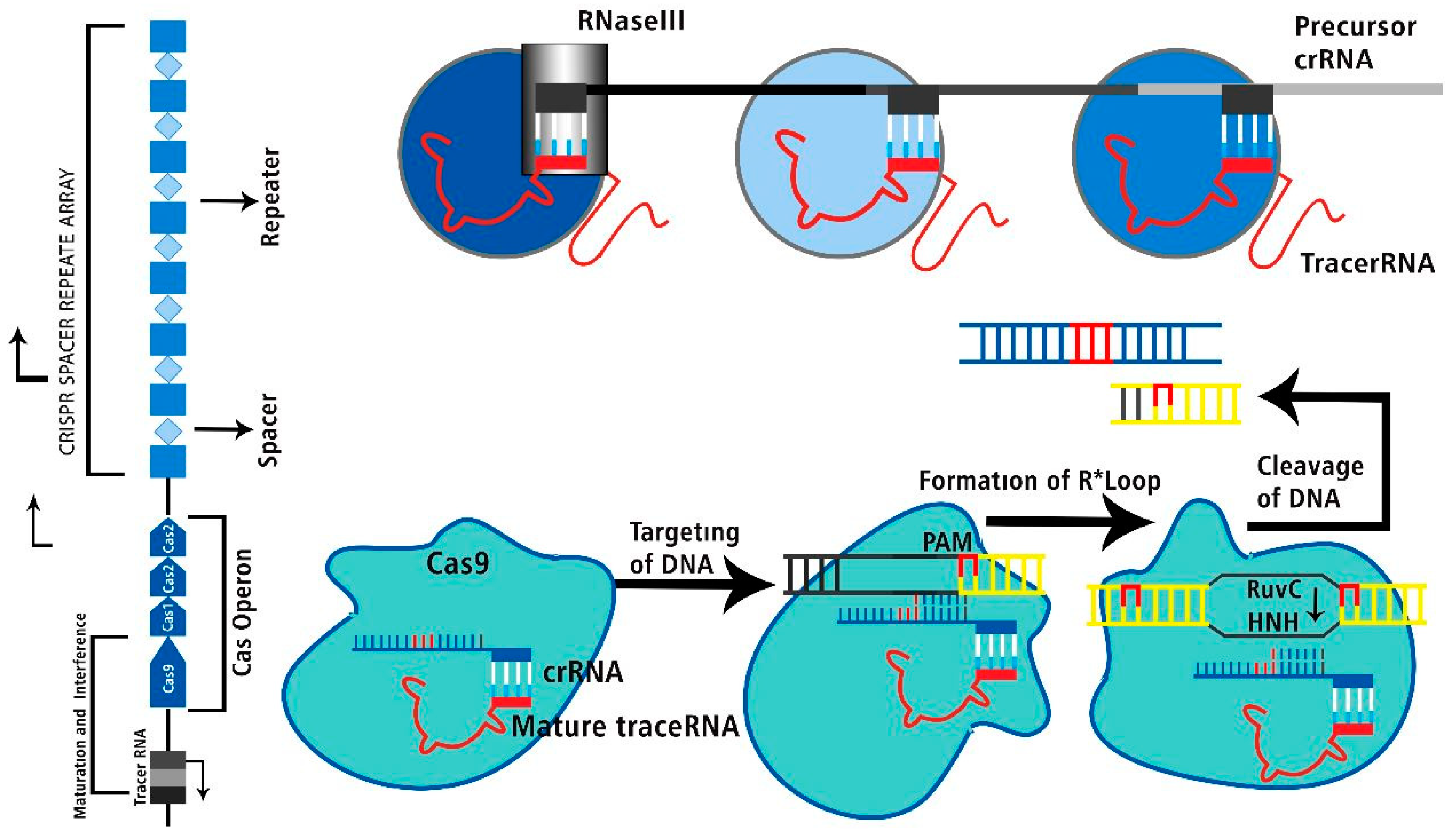

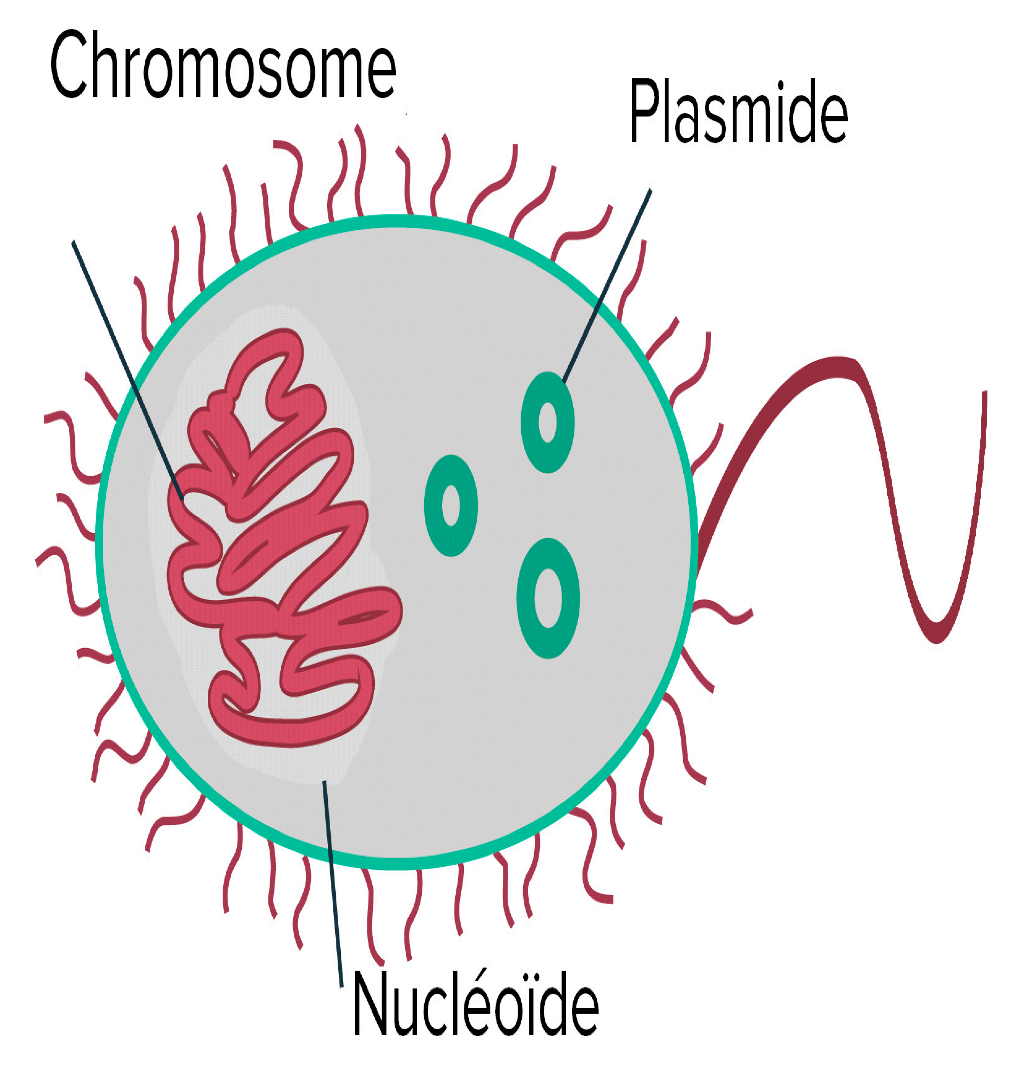

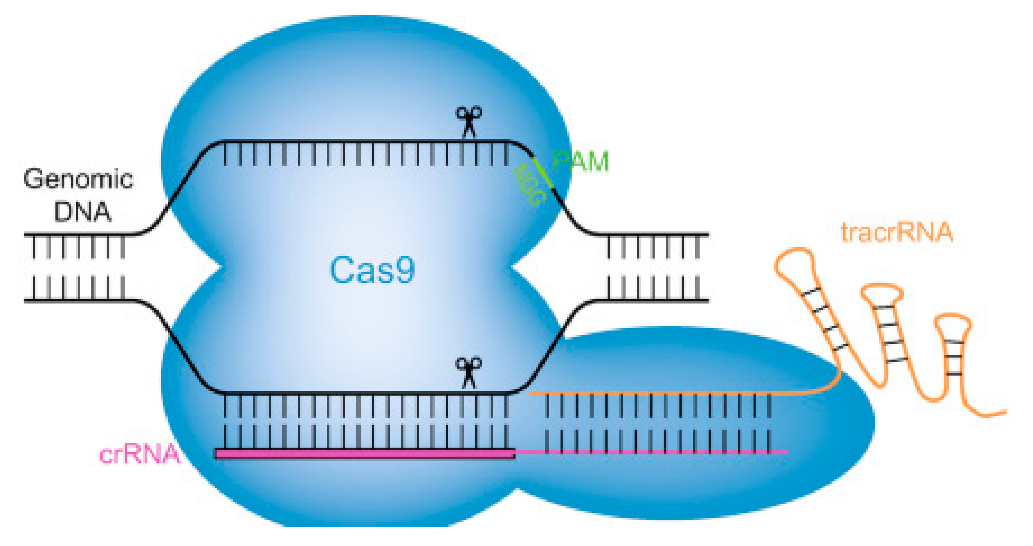

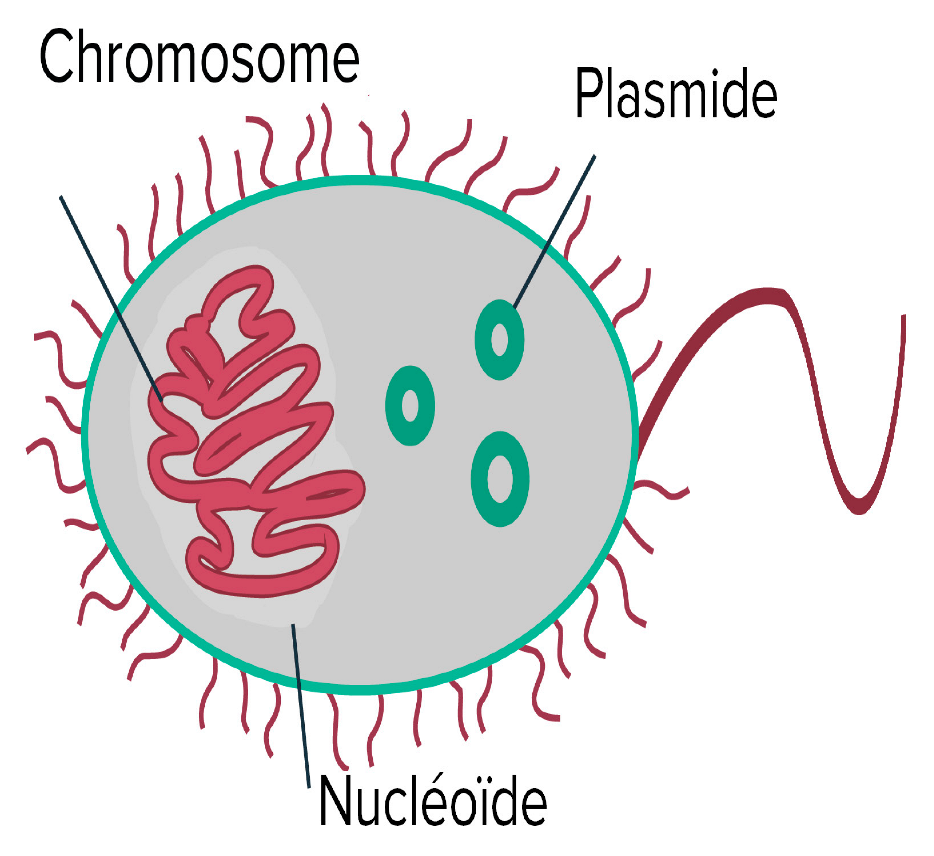

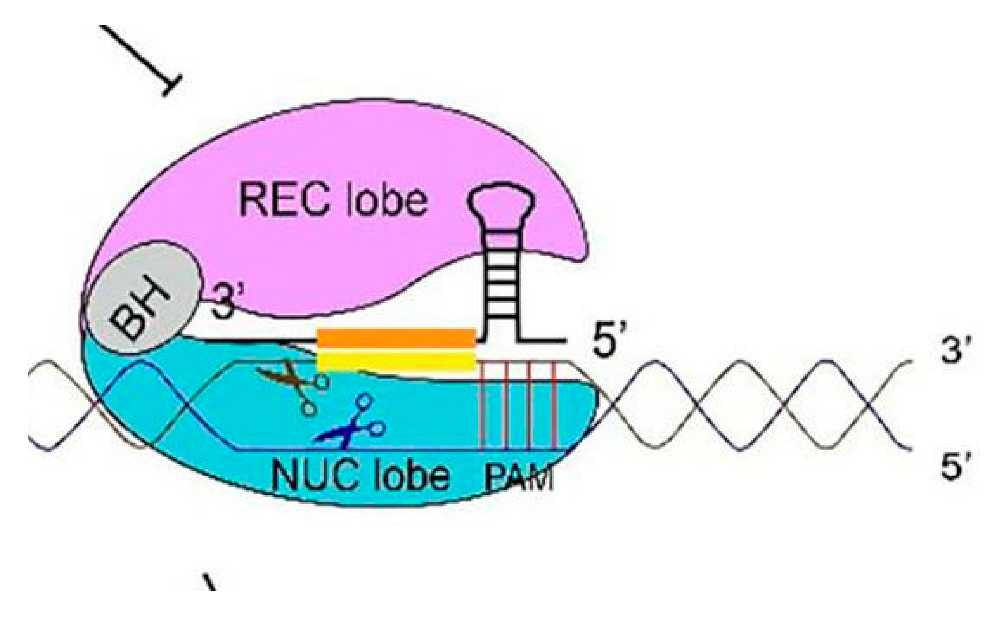

CRISPR-Cas System’s Groups and Classes

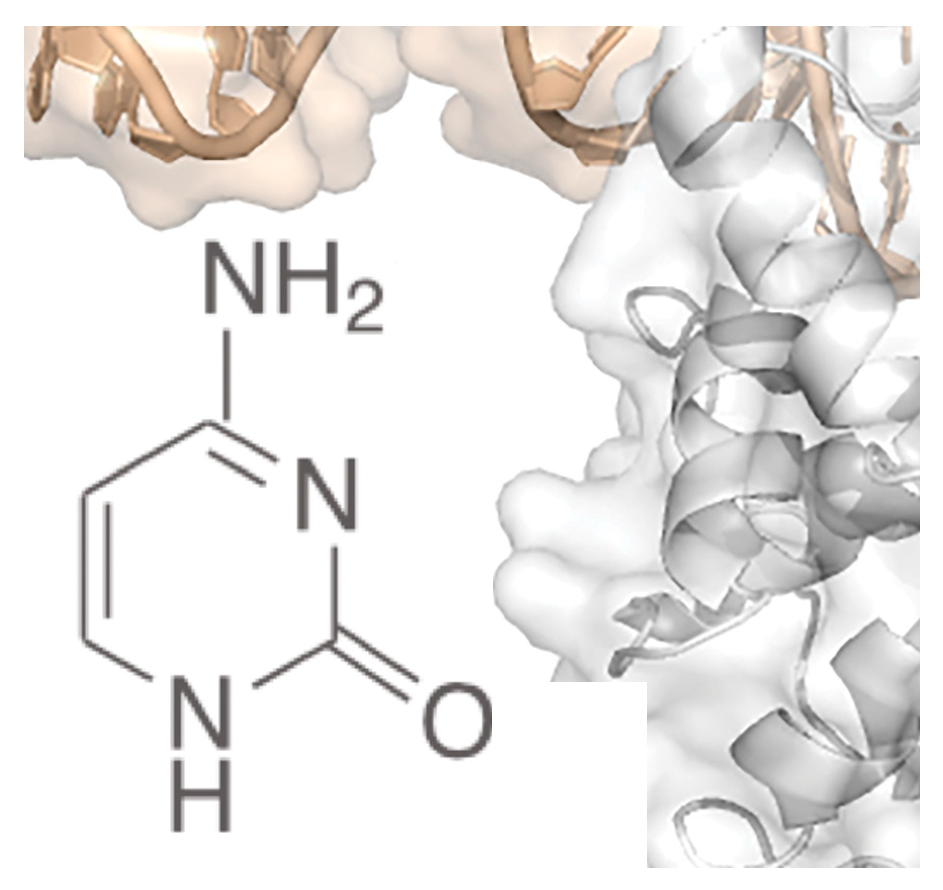

Characteristics of CRISPR-Cas Technology

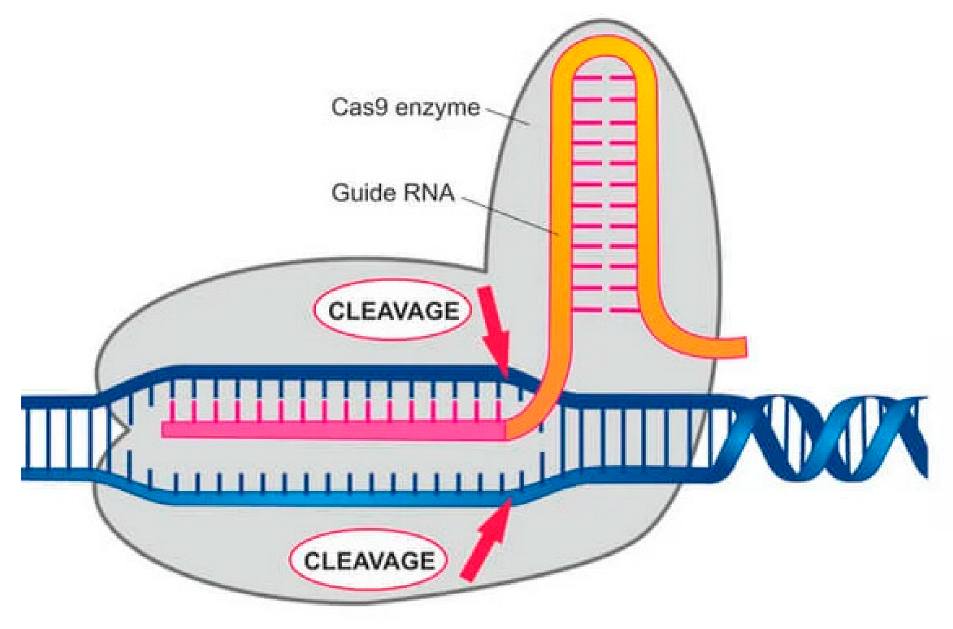

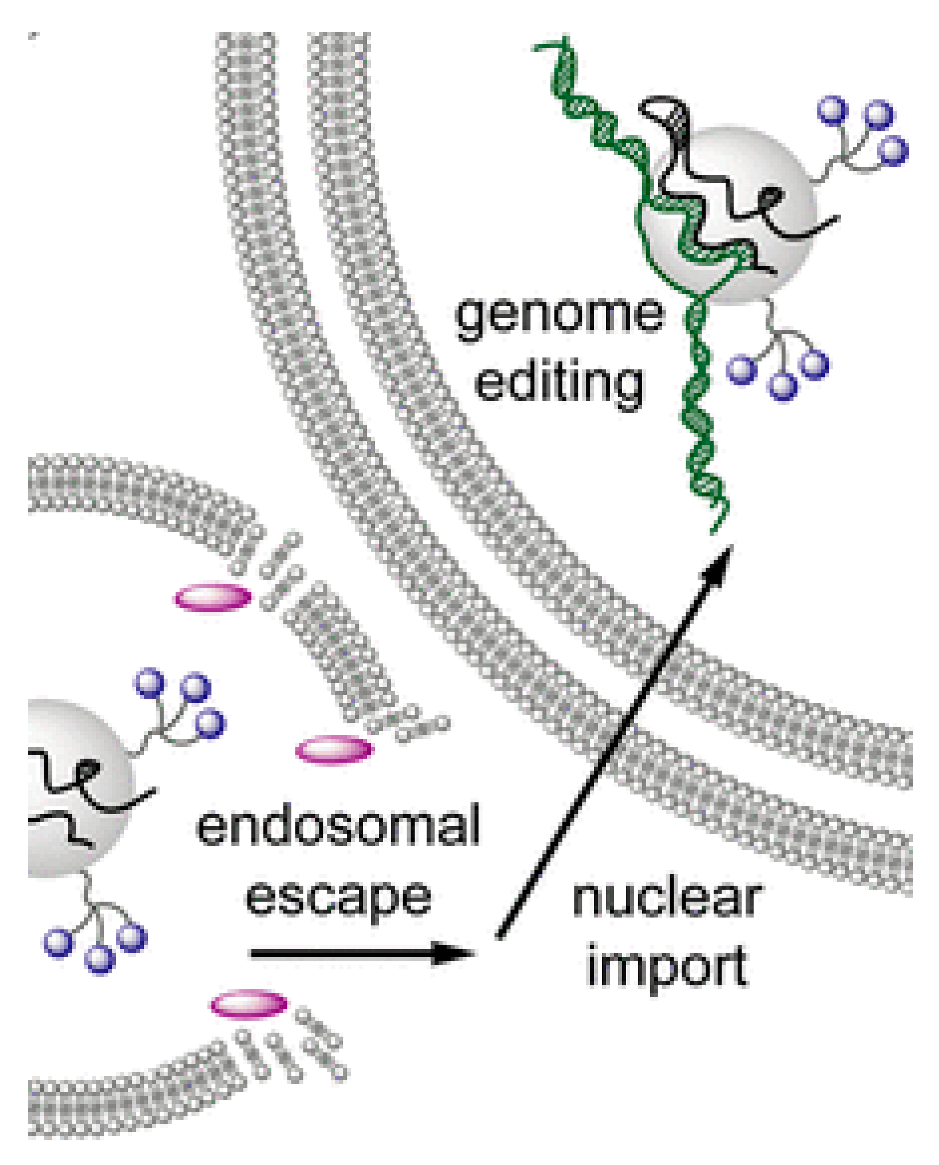

Genome Modification, Cleavage Reliability and Specificity

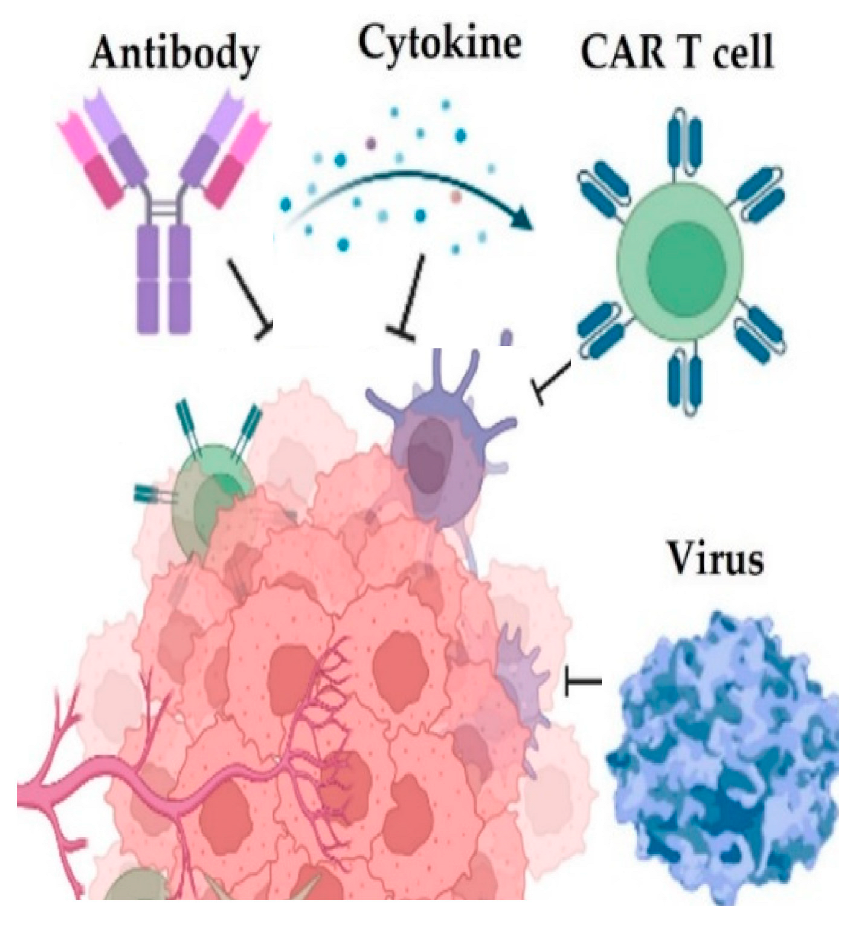

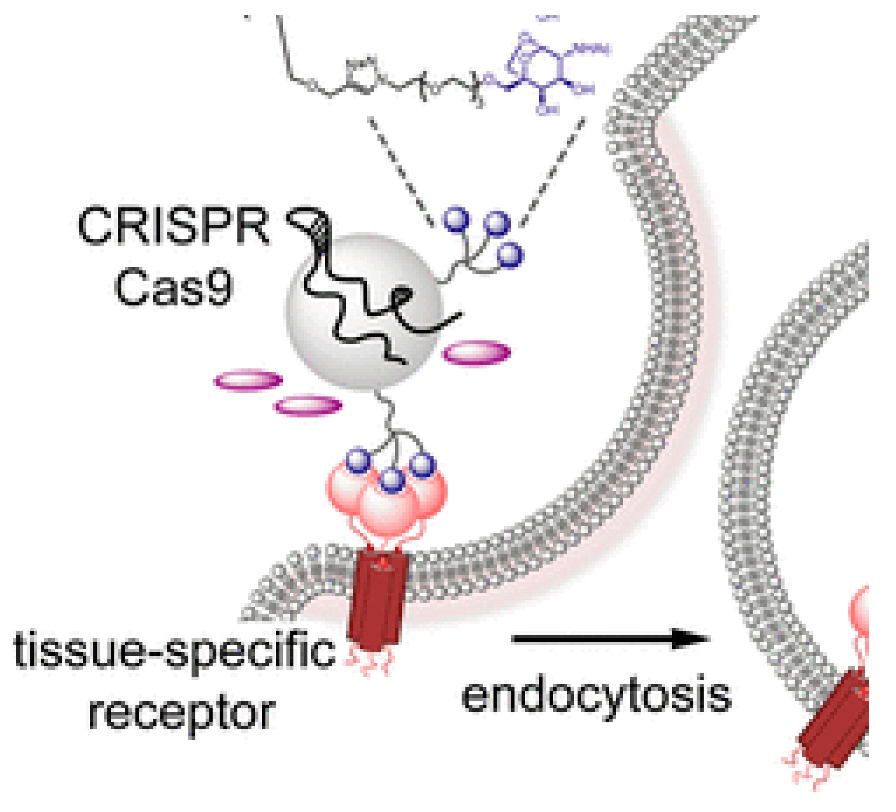

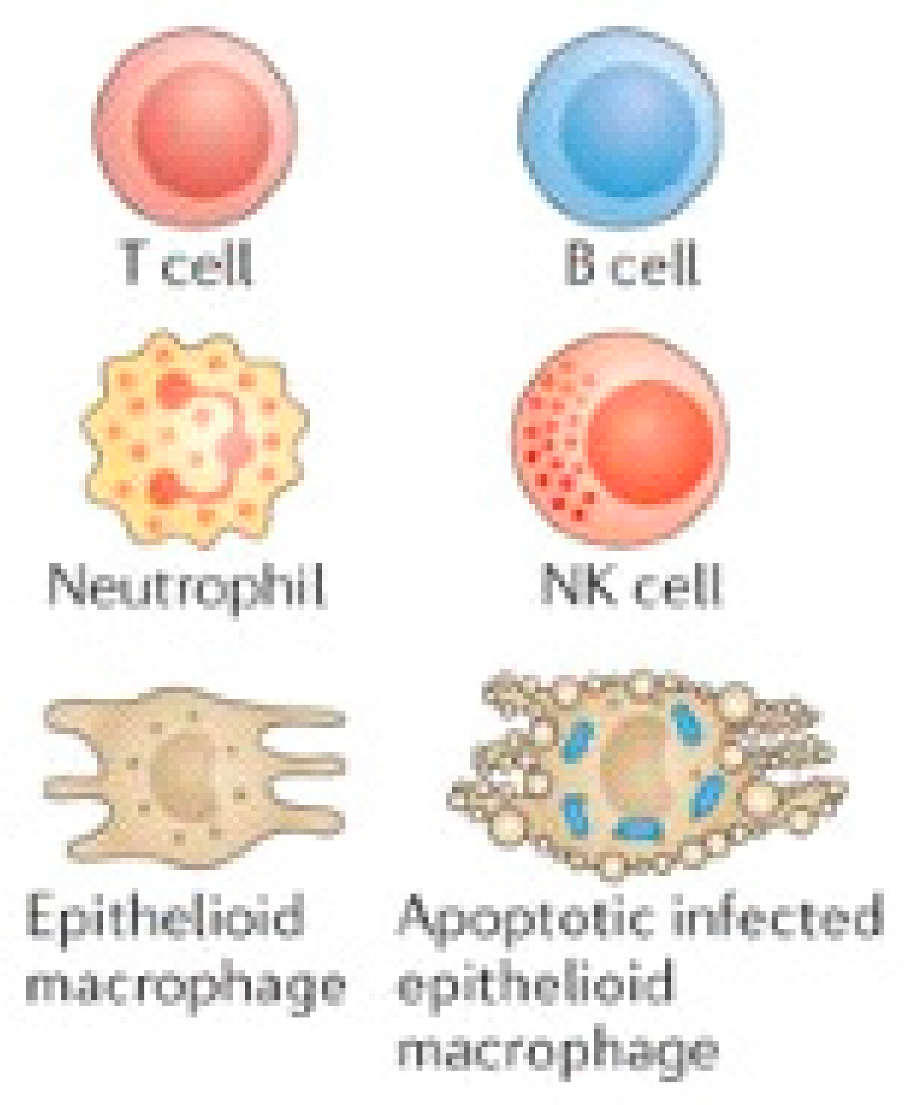

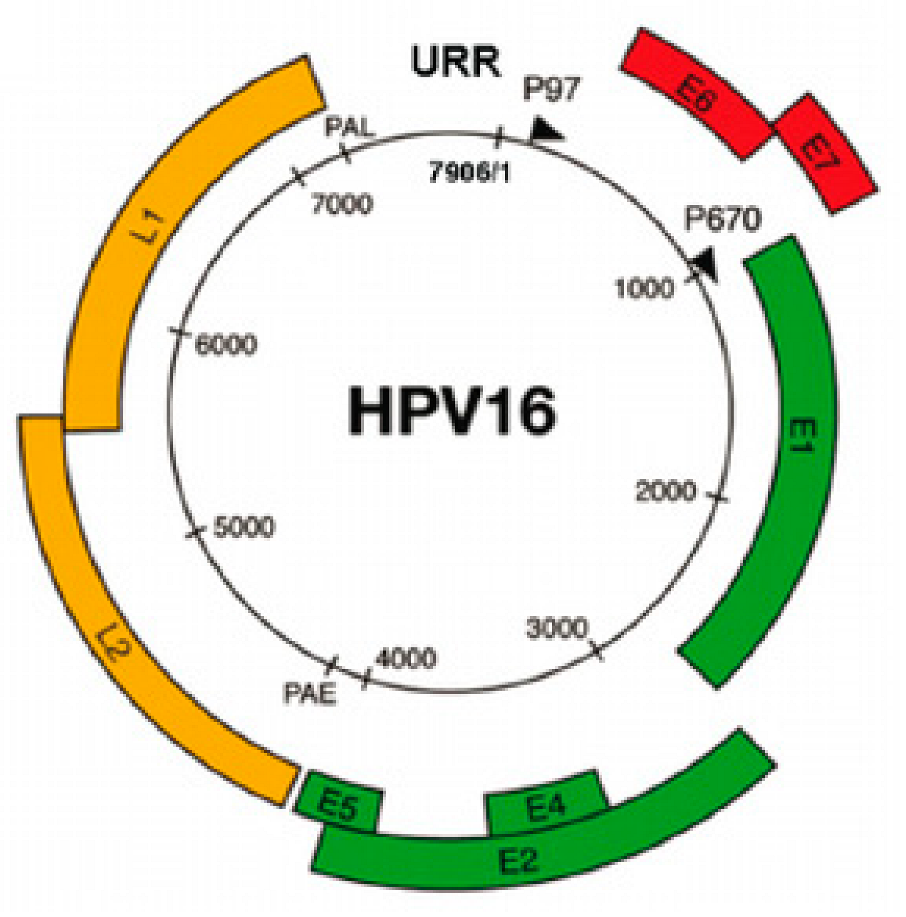

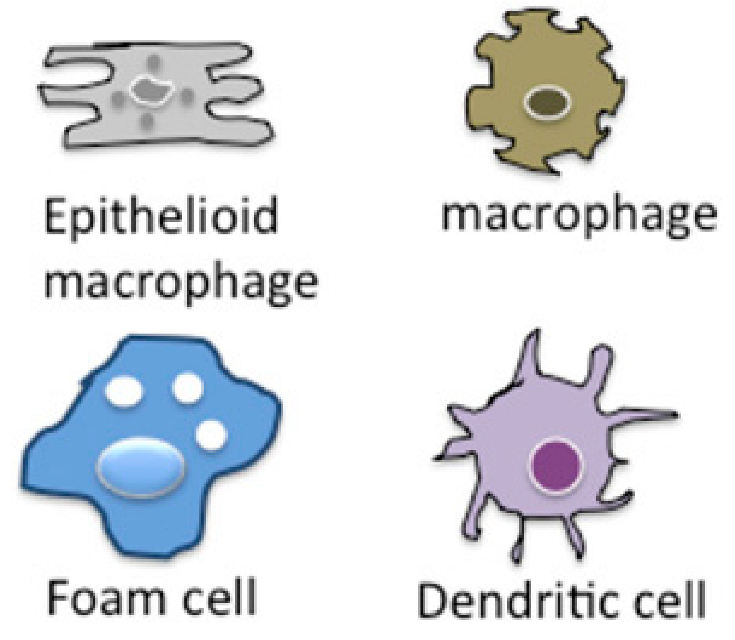

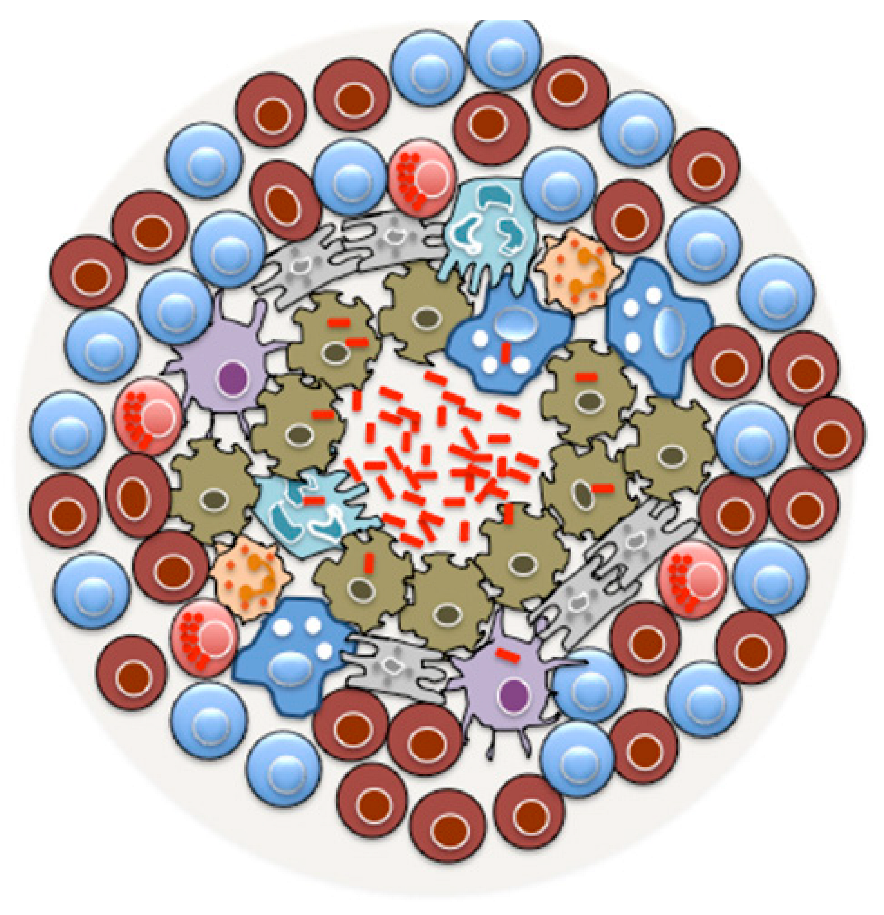

Biomedical Applications

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval and Consent to participate

Animal rights

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abudayyeh, O.O.; et al. (2017) RNA targeting with CRISPR–Cas13. Nature 550, 280–28. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; et al. (2016) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated immunity to geminiviruses: differential interference and evasion. Sci. Rep. 6, 26912. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; et al. (2017) Efficient targeted multiallelic mutagenesis in tetraploid potato (Solanum tuberosum) by transient CRISPR-Cas. [CrossRef]

- Bayat, H.; et al. (2018) The conspicuity of CRISPR[1]Cpf1 system as a significant breakthrough in genome editing. Curr. Microbiol. 75, 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Braatz, J.; et al. (2017) CRISPR-Cas9 targeted mutagenesis leads to simultaneous modification of different homoeologous gene copies in polyploid oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Plant Physiol. 174, 935–942. [CrossRef]

- Char, S.N.; et al. (2017) An Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR/Cas9 system for high-frequency targeted mutagenesis in maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 257–268. [CrossRef]

- Che, P.; et al. (2018) Developing a flexible, high[1]efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated sorghum transformation system with broad application. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 1388–1395. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; et al. (2017) Targeted mutagenesis in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) using the CRISPR/ Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 7, 44304. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; et al. (2018) Applications of CRISPR/Cas system to bacterial metabolic engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1089. [CrossRef]

- Dreissig, S.; et al. (2017) Live-cell CRISPR imaging in plants reveals dynamic telomere movements. Plant J. 91, 565–573. [CrossRef]

- Enciso-Rodriguez, F.; et al. (2019) Overcoming self[1]incompatibility in diploid potato using CRISPR[1]Cas9. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 376. [CrossRef]

- Endo, M.; et al. (2019) Genome editing in plants by engineered CRISPR–Cas9 recognizing NG PAM. Nat. Plants 5, 14–17. [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Bartolome´, J.; et al. (2018) Targeted DNA demethylation of the Arabidopsis genome using the human TET1 catalytic domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, E2125–E2134. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; et al. (2017) Engineered Cpf1 variants with altered PAM specificities. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 789–792. [CrossRef]

- Gaudelli, N.M.; et al. (2017) Programmable base editing of A, T to G, C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, J.M.; et al. (2018) An APOBEC3A-Cas9 base editor with minimized bystander and off-target activities. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 977–982. [CrossRef]

- Harrington, L.B.; et al. (2018) Programmed DNA destruction by miniature CRISPR-Cas14 enzymes. Science 362, 839–842. [CrossRef]

- (2013) DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 827–832. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.H.; et al. (2018) Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 556, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; et al. (2019) Genome engineering in rice using Cas9 variants that recognize NG PAM sequences. Mol. Plant 12, 1003–1014. [CrossRef]

- Jansing, J.; et al. (2018) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of six glycosyltransferase genes in Nicotiana benthamiana for the production of recombinant proteins lacking b-1, 2-xylose and core a-1, 3-fucose. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 350–361. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; et al. (2018) Direct observation of DNA target searching and cleavage by CRISPR-Cas12a. Nat. Commun. 9, 2777. [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; et al. (2016) Modification of the PthA4 effector binding elements in type I CsLOB1 promoter using Cas9/sg RNA to produce transgenic Duncan grapefruit alleviating XccDpthA4:dCsLOB1.3 infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 1291–1301. [CrossRef]

- Kanazashi, Y.; et al. (2018) Simultaneous site[1]directed mutagenesis of duplicated loci in soybean using a single guide RNA. Plant Cell Rep. 37, 553–563. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; et al. (2018) CRISPR/Cas9- mediated efficient editing in phytoene desaturase (PDS) demonstrates precise manipulation in banana cv. Rasthali genome. Funct. Integr. Genom 18, 89–99. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; et al. (2019) Targeting plant ssDNA viruses with engineered miniature CRISPR-Cas14a. Trends Biotech. 37, 800–804. [CrossRef]

- Khanday, I.; et al. (2019) A male-expressed rice embryogenic trigger redirected for asexual propagation through seeds. Nature 565, 91–95. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; et al. (2017) In vivo genome editing with a small Cas9 orthologue derived from. Campylobacter jejuni. Nat. Commun. 8, 14500. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; et al. (2017) Increasing the genome[1]targeting scope and precision of base editing with engineered Cas9-cytidine deaminase fusions. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 371–376. [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; et al. (2015) Engineered CRISPR[1]Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature 523, 481–485. [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; et al. (2019) Engineered CRISPR–Cas12a variants with increased activities and improved targeting ranges for gene, epigenetic and base editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 276–282. [CrossRef]

- Kocak, D.D.; et al. (2019) Increasing the specificity of CRISPR systems with engineered RNA secondary structures. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 657–666. [CrossRef]

- Komor, A.C.; et al. (2017) Improved base excision repair inhibition and bacteriophage Mu Gam protein yields C:G-to-T:A base editors with higher efficiency and product purity. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao4774. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; et al. (2016) The Neisseria meningitides CRISPR-Cas9 system enables specific genome editing in mammalian cells. Mol. Ther. 24, 645–654. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; et al. (2018) Activities and specificities of CRISPR/Cas9 and Cas12a nucleases for targeted mutagenesis in maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 362–372. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; et al. (2018) Editing of an alpha-kafirin gene family increases, digestibility and protein quality in Sorghum. Plant Physiol. 177, 1425–1438. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; et al. (2017) Targeted mutagenesis in the medicinal plant. Salvia miltiorrhiza. Sci. Rep. 7, 43320. [CrossRef]

- Pessina, S.; et al. (2016) Knockdown of MLO genes reduces susceptibility to powdery mildew in grapevine. Hort. Res. 3, 16016. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; et al. (2017) A high-efficiency CRISPR/Cas9 system for targeted mutagenesis in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Sci. Rep. 7, 43902. [CrossRef]

- Macovei, A.; et al. (2018) Novel alleles of rice eIF4G generated by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis confer resistance to rice tungro spherical virus. Plant. [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; et al. (2015) An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 722–736. [CrossRef]

- Malnoy, M.; et al. (2016) DNA-free genetically edited grapevine and apple protoplast using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1904. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; et al. (2017) Heritability of targeted gene modifications induced by plant-optimized CRISPR systems. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 1075–1093. [CrossRef]

- Mercx, S.; et al. (2017) Inactivation of the b (1, 2)- xylosyltransferase and the a (1, 3)-fucosyltransferase genes in Nicotiana tabacum BY-2 cells by a multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 strategy results in glycoproteins without plant-specific glycans. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 403. [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.; et al. (2018) Heavily and fully modified RNAs guide efficient SpyCas9-mediated genome editing. Nat. Commun. 9, 2641. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.B.; et al. (2018) Highly efficient genome editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using CRISPR RNA with a uridinylate-rich 3ʹ-overhang. Nat. Commun. 9, 3651. [CrossRef]

- Nishimasu, H.; et al. (2018) Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease with expanded targeting space. Science 361, 1259–1262. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; et al. (2018) High-throughput detection and screening of plants modified by gene editing using quantitative real-time PCR. Plant J. 95, 557–567. [CrossRef]

- Puchta, H.; et al. (2017) Applying CRISPR/Cas for genome engineering in plants: the best is yet to come. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 36, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; et al. (2019) High efficient and precise base editing of C, G to T, A in the allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) genome using a modified CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol. J. Published online May 22, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rees, H.A.; Liu, D.R. (2018) Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 770–788. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; et al. (2018) Cis-trans engineering advances and perspectives on customized transcriptional regulation in plants. Mol. Plant 11, 886–898. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; et al. (2017) A CRISPR–Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing and transcriptional repression in plants. Nat. Plants 3, 17018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; et al. (2018) High efficient multisites genome editing in allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol J. 16, 137–150. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; et al. (2018) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient targeted mutagenesis in grape in the first generation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 16, 844–855. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.O.; et al. (2018) The current state and future of CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA design tools. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 749. [CrossRef]

- Wolter, F.; Puchta, H. (2018) The CRISPR/Cas revolution reaches the RNA world: Cas13, a new Swiss Army knife for plant biologists. Plant J. 94, 767–775. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; et al. (2017) APOBEC: from mutator to editor. J. Genet. Genomics 44, 423–437 Doudna, J.A. and. [CrossRef]

| Advancement/ Discovery | Advancement/ Discovery | ||

| 2020 Nobel prize for CRISPR Cas9 genome editing |

|

2019 First invivo CRISPR clinically trialed for the treatment monogenic disorders. The invention of nCATS by CRISPR/Cas9 |

|

| 2018 1st CRISPR clinical trial for cancer immunotherapy |

|

2016 The Base editor (BE) was made after Cas13a (C2c2) was found. |

|

| 2015 Therapeutic proof of concept based on the discovery of Cas13a (C2c2), which is a part of the Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 system, and its use to fix the dystrophin gene in vitro and then put it into a mouse model. The Base editor (BE) was made after Cas12a (Cpf1) was found. |

|

2014 Cas9 has been turned into a solid, and libraries for screening the whole genome have been made. |

|

| 2013 Using CRISPR Cas9, cells from mammals were successfully changed. When two Cas9n Nickases are used together, they work better for off-site targeting. Evidence for genome editing in eukaryotic cells using CRISPR/Cas9. Cas9-based functional screening of the whole genome. For the first time, it has been shown that eukaryotic cells can use Cas9 to change their DNA. |

|

2014 Mammalian cells' genomes are being changed. Mammalian cells' genomes are being changed. The finds of dCas9, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa. Cas9 RNA makes site-specific editing of the genome possible in human cells and other living creatures. The finds of dCas9, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa. Cas9 RNA makes site-specific editing of the genome possible in human cells and other living creatures. |

|

| 2012 In live species, Cas9 was shown to be an RNA-guided endonuclease, and its ability to target DNA was defined. Cas9-driven DNA targeting: a look in the lab. CRISPR Cas9 is a DNA endonuclease that is directed by RNA and has been studied in a lab dish.. |

|

2011 There are three parts to the CRISPR system, and each one is made up of a different mix of tracrRNA, crRNA, and Cas9. The finds of tracRNA and Type II CRISPR Even though all cas genes have tracRNA, only the cas9 gene is needed for type II defence. |

|

| 2010 Cas9 is led to the place where the DNA will be cut by protospacer sequences. Gameau (2010) found that Cas9 cuts target DNA and that Type II CRISPR Cas also cuts target DNA (67). |

|

2009 Cmr complex cleaves ssRNA |

|

| 2008 CRISPR system types III-A targets DNA, Discovered the function of crRNA |

|

The first experimental proof that CRISPR gives adaptive immunity (Barrangou et al., 2007) suggests that CRISPR ioci may give their hosts adaptive immunity. |  |

| 2005 Due to the fact that the alien origin of the spaceship was found, the adaptive immune function was proposed. Cas genes found in CRISPRs include virus sequences. (2005-2006) |

|

2002 Identification of Cas genes, Coined the CRISPR acronym, CRISPR name adopted and signature Cas genes identified. Coined CRISPR name defined signature Cas genes, Coined CRISPR name, discovery of Cas genes |

|

| 2000 Discovered that CRISPR families are widespread in procaryotes |

|

1993 Discovery of CRISPR clustered repeats in M. tuberculosis |

|

| 1987 Escherichia coli was the first to find CRISPR grouped repeats. The CRISPR-associated grouped repeats were found. In a 1987 study by Ishino et al., CRISPR clustered repeats (CRISPR) were first described. This study was also the first to describe CRISPR clustered repeats. |

|

1979 Gene Replacement in yeast. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).