3. A Robot Embedding of a Model of Action Selection by the Basal Ganglia

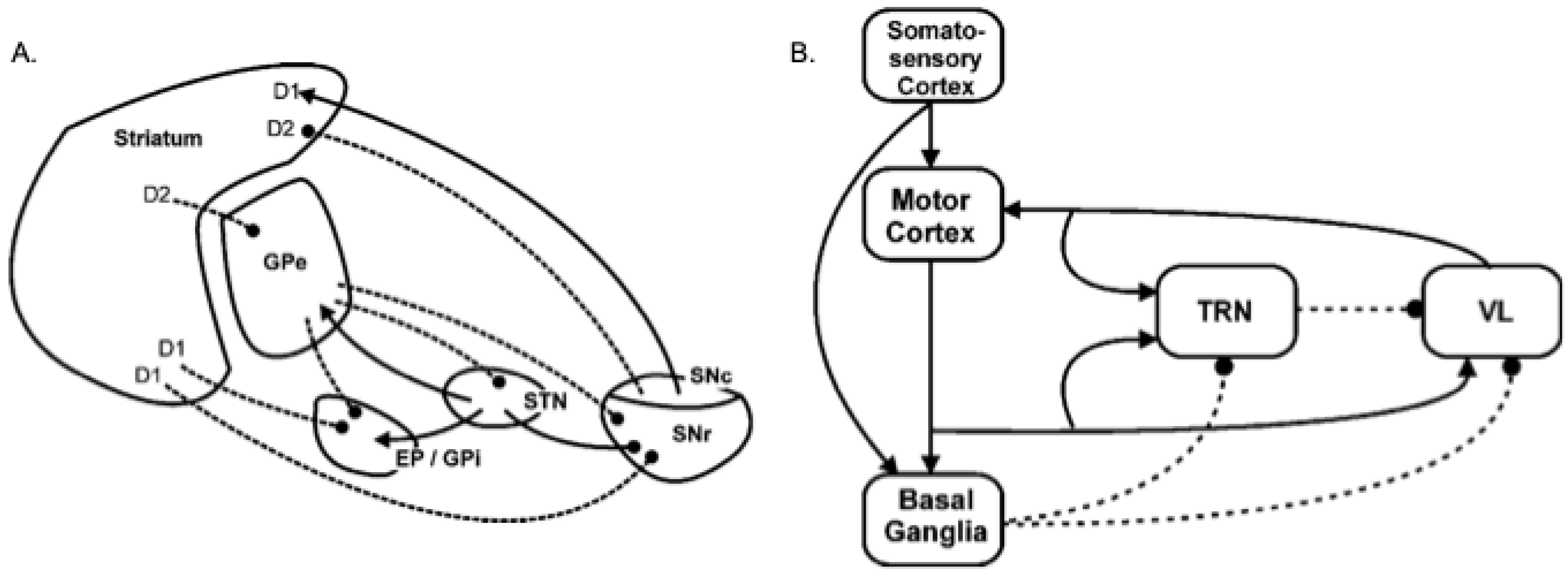

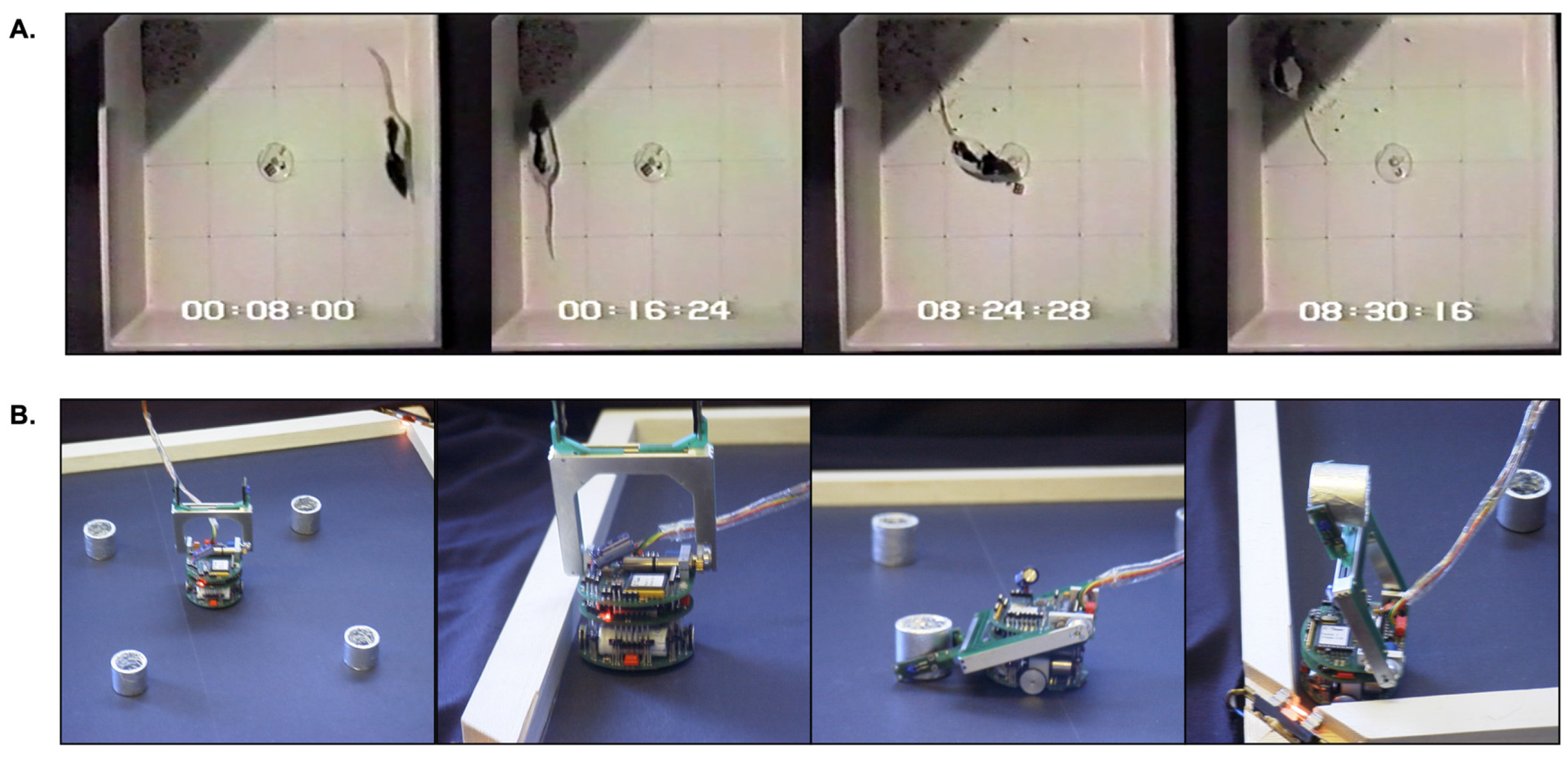

Prescott et al. [

36,

56] embedded the extended basal ganglia model [

41] within the control architecture of a mobile robot in order to demonstrate that signal selection by the embedded model, as described above, could translate into effective action selection for an embodied agent expressing goal-directed behavior. This model was based on consideration of the typical behavior of a hungry rat placed in an open-topped arena with high sides (

Figure 2a and

Supplementary Video, part 1). In this situation, animals initially show fearful or thigmotaxic behavior—avoiding open areas in the centre of the arena, whilst exploring walls and corners. As animals become more accustomed to the novel environment, they show foraging behavior—collecting food pellets from a dish placed in the centre of the arena and typically consuming them in sheltered areas near the periphery. Salamone [

10] showed that effective behavior switching in a similar environment is compromised by the dopamine antagonist Haloperidol and by dopamine-depleting lesions of the striatum, hence the task is an appropriate one for investigation of the effects of variation in simulated dopamine on robot action selection.

In the robot model of this task (

Figure 2b and

Supplementary Video, part 2), a table-top

Khepera mobile robot with a gripper turret is placed in a rectangular arena with illuminated corners, to simulate safe places, and with small foil-covered cylinders to simulate food rewards. Fearful behavior is simulated as staying close to walls and corners; foraging involves searching for, locating, and picking up the cylinders; finally, consummatory behavior is modelled as carrying a cylinder to one of the two illuminated corners and depositing it there. To generate appropriate behavior, robot activity is decomposed into five sub-systems inspired by the ethological classification of behavior. Three of the five action sub-systems—

cylinder-seek, wall-seek, and

wall-follow—map patterns of input from the robot’s sensors into movements that orient the robot towards or away from specific types of stimuli (e.g. object contours). These behaviors can be viewed as belonging to the ethological category of

orienting responses or

taxes [see e.g. 57]. The two remaining sub-systems—

cylinder-pickup and

cylinder-deposit—generate carefully timed movement sequences that achieve specific behavioral outcomes and are modeled on the ethological concept of a

fixed action pattern (FAP) [

58]. Each action sub-system generates its preferred action at a given moment in the form of a

motor vector that specifies target values for the speeds of the two wheels, and for the positions of the gripper arm (raised/lowered) and gripper jaw (open/shut). In the case of the orienting responses, the preferred action is computed using the sensory information available to the robot at that moment, in the case of FAPs, the action specification can also depend on the current value of an internal clock.

In order to make appropriate action selection decisions, the robot needs information about relevant external and internal cues. Signals pertaining to external cues are computed by perceptual sub-systems from the raw sensory data available to the robot via an array of infra-red distance sensor signals, an ambient light sensor, and an optical sensor in the robot gripper. These sensory inputs are used to compute four bipolar signals indicating: the presence (+1) or absence (-1) of a nearby wall, nest area, cylinder, or of an object in the robot gripper. Internal state cues are provided in the form of two real-valued intrinsic drives, loosely analogous to hunger and fear, as calculated by two motivational sub-systems. In the model, ‘fear’ is calculated as a function of exposure to the environment and is reduced with time spent in the environment, whilst ‘hunger’ gradually increases with time and is reduced when cylinders are deposited in the nest corners of the arena.

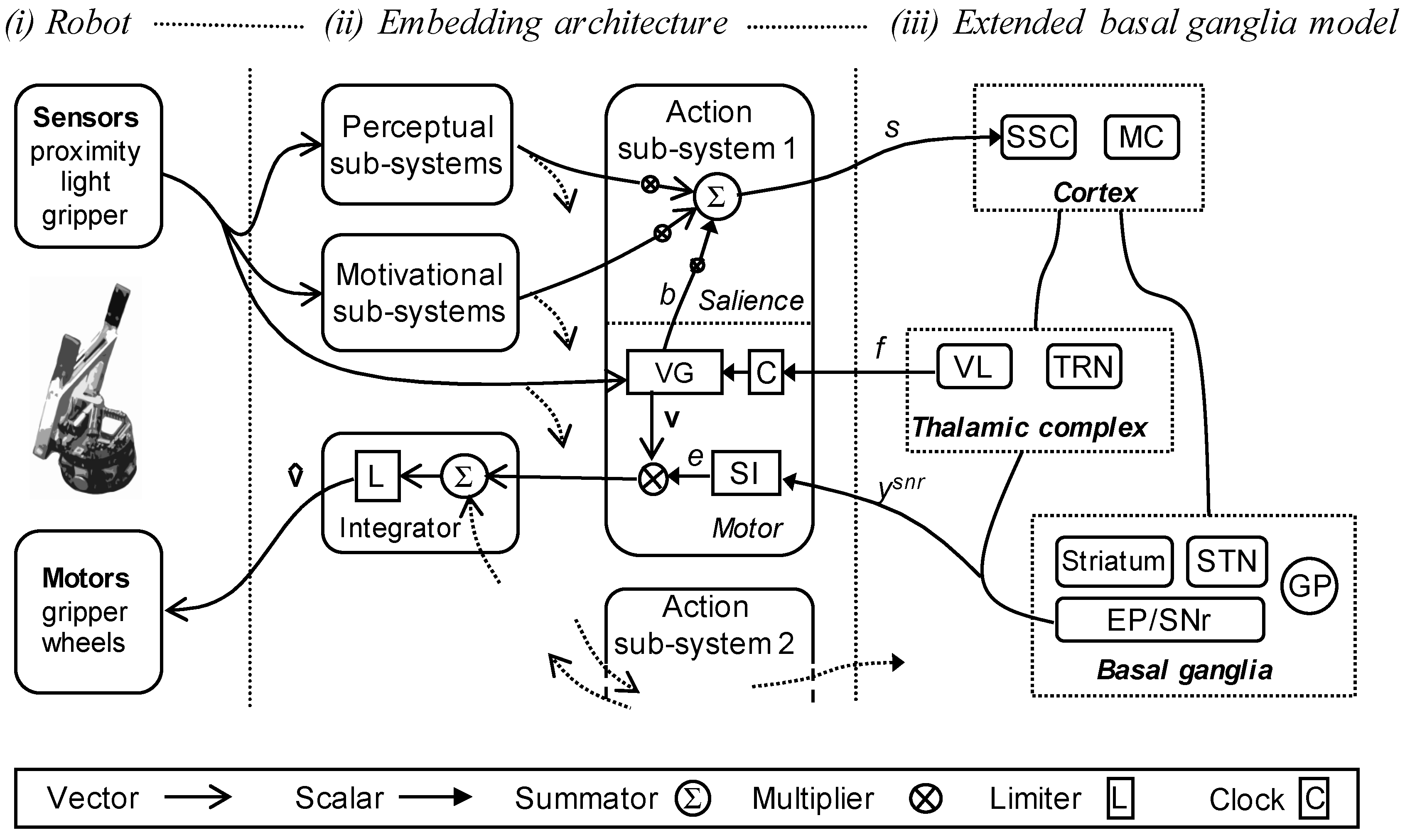

Figure 3 shows how these different component sub-systems come together and interact with the embedded basal ganglia model. The model is composed of three parts: (i) the

robot and its sensory and motor systems; (ii) the

embedding architecture, that is, the set of

perceptual, motivational, action sub-systems; and its interface to (iii) the

extended basal ganglia model. Connections for the first of the five action sub-systems are shown, projections to and from the other action sub-systems are indicated by dotted lines.

As shown in

Figure 3, each action sub-system takes inputs from the perceptual and motivational sub-systems, and from an internally-generated

busy signal (

b) that is only non-zero if the action is currently selected, and that allows that sub-system to selectively boost its own salience. Based on these inputs the action sub-system generates a weighted sum (the weights are hand-tuned) that is an estimate of its own instantaneous

salience (

s) that is provided as an input to the embedded basal ganglia model. At the same time, the action-generating component of the sub-system calculates its preferred motor vector based on the robot’s sensor input and a

feedback signal (

f) from the component of basal ganglia model corresponding to the

ventrolateral thalamus (VL). This feedback signal is used to update or reset the clock (C) for the action system (in the case of a FAP), and to trigger the

busy signal that contributes to its salience calculation.

As noted above, for each action sub-system i, the output of the basal ganglia, , is converted into a gating signal, , via equation 1 which is then used to scale the value of the motor vector for that action. An integrator module then sums all of the motor vectors and passes the aggregate vector through a limiter (L) that constrains all values to lie in the range 0–1, this vector is then converted into the specific motor commands that control the robot. The full robot model operates on a series of discrete time-steps providing sensor updates and modifying its action output at a rate of approximately 7Hz. The embedded basal ganglia model is simulated using the Euler method and run to convergence for each time-step of the robot model.

Full details of the test environment, the robot sensor and motor systems, the embedding architecture components, and the simulation of the extended basal ganglia model, including their motivation in relation to the neuroscientific understanding of relevant brain sub-systems, are provided in [

36], which also provides a broader discussion of the use of robotic models in neuroscience.

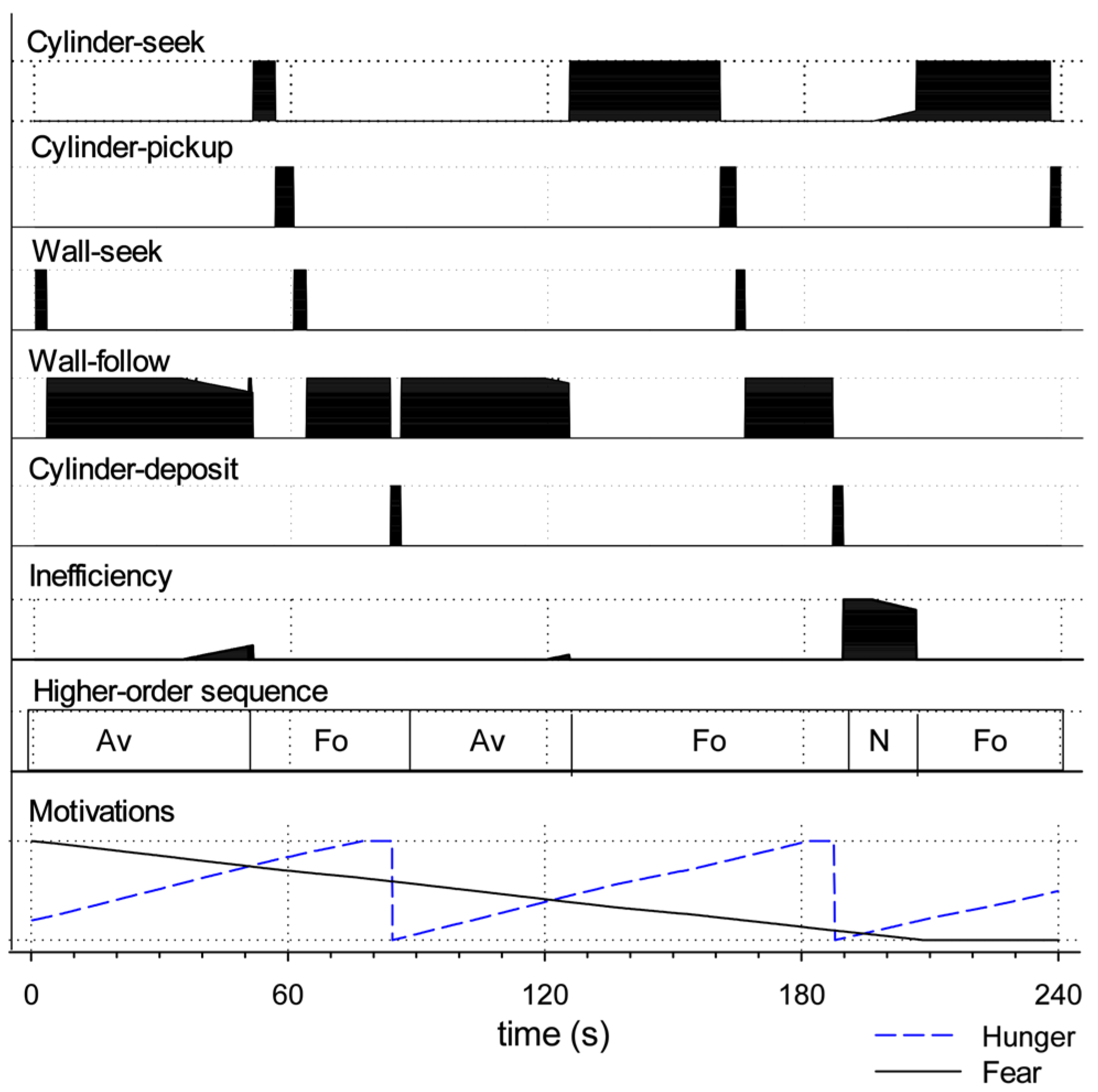

To illustrate normal functioning of the model,

Figure 4 shows a single 240s run with the level of simulated tonic dopamine set at λ = 0.20. The top five lines of the plot show the value of the gating signal,

, for each of the five action sub-systems at each time step in the style of a behavioral ethogram. Comparing across the different actions, it is evident that the robot generates extended sequences of behavior with no more than one action sub-system fully selected at any given time. The efficiency of selected actions is at or near 100%, actions are performed over extended bouts (solid blocks of high efficiency) and the inefficiency of the winner (plotted as the sixth line of the plot) is generally near zero. In this run, the robot is initially fearful and seeks the wall (

wall-seek), then switches into its

wall-follow behavior. This can be viewed as forming a

higher-order sequence of

avoidance (

Av) behavior as labelled in the seventh line of the plot. The final line of the plot shows the activity of the model motivational systems. As the level of simulated fear gradually subsides, simulated hunger is increasing. As a result, at around 50s, the robot rapidly switches into its

cylinder-seek behavior. When it subsequently locates a cylinder it switches to

cylinder-pickup, then to

wall-seek (this time carrying a cylinder), then

wall-follow, and, when it finds a lit corner,

cylinder-deposit. The higher-order action sequence beginning with

cylinder-seek and ending with a successful deposit is labelled as

foraging (Fo) in the plot. Releasing the cylinder has the effect of reducing simulated hunger such that the robot is again motivated principally by fear to perform its avoidance-related behaviors (

wall-seek and

wall-follow). However, the level of simulated hunger gradually rises which leads to two further higher-order foraging sequences interspersed by a period of

no behavior. The absence of behavior occurs when neither of the intrinsic motivations is sufficiently strong to trigger any action—the robot sits idle, just as the rat might wait quietly in the corner of the arena.

From the perspective of the observer, the robot’s behavior appears to be integrated and purposeful, individual action bouts are assembled to larger sequences that successfully reduce its drives. In section 5, we will compare this example of effective action selection and integrated behavior with other runs in which the robot demonstrates various forms of behavioral disintegration as the result lowering or raising the level of simulated dopamine in the model basal ganglia.

4. Tonic Dopamine Modulation in the Extended Basal Ganglia Model

Before presenting further results for the robot model, it is useful to investigate the response of a non-embodied version of the extended basal ganglia model to changes in tonic dopamine modulation as this will provide a useful yardstick for evaluating the embodied robotic version, and will help us to better understand the specific consequences that embodiment might entail. This investigation builds on prior studies of simulated tonic dopamine modulation [

40,

41] by providing a fine-grained analysis across the spectrum of possible λ levels.

To better understand the effect of varying simulated dopamine on the selection properties of the extended basal ganglia model we simulated a five channel model, with two active channels, varying the salience

in channel 1 systematically from 0 to 1 in steps of 0.01, then for each value of

, varying the salience

of channel 2 from 0 through 1, again in steps of 0.01. For each resulting salience vector

the model was run to convergence and the result classified according to the scheme set out in

Section 2. Importantly, selection competitions were run in sequence from low values to high values. The activations levels of all leaky integrators in the model were initialized to zero for each new value of

but thereafter, while that salience value was tested, were retained from one competition to the next. In other words, we simulated the situation where channel 1 was initially the only active channel, and

gradually increased channel 2 while holding channel 1 constant, the goal being to simulate some aspects of the continuity of experience that we can expect in the robot model in which the recent history of selection competitions may influence the current competition through hysteresis. Previous studies have established that the basal ganglia model, in both its original and extended forms, shows good selection properties, across a wide-range of salience pairings, with the simulated dopamine level set at around λ= 0.20; for this analysis we therefore looked at values of simulated dopamine ranging from 0 through to 0.5 in increments of 0.01.

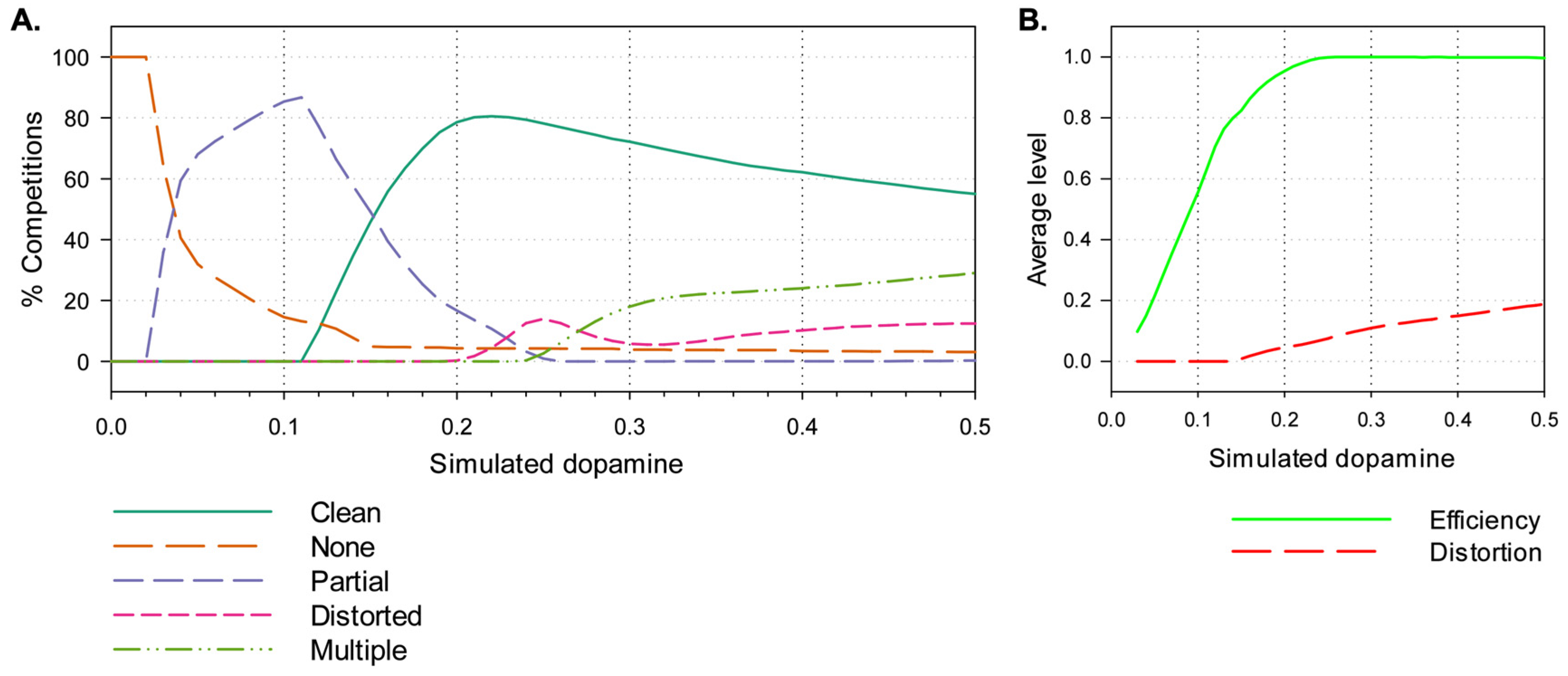

Figure 5a shows the percentage of action selection competitions, across the 500,000 (50x100x100) runs, falling into each of the selection classes—

clean selection, no selection, partial selection, distortion, and multiple selection. Values of λ below 0.01 result in no selection, while in the range 0.04–0.15 partial selection predominates, from 0.15 upwards the majority of competitions end in clean selection with a peak around 0.22, distorted selection begins to appear with values above 0.2, and multiple selection occurs with levels of 0.25 and greater.

Figure 5b shows the average values of efficiency and distortion across all runs at a given level of λ. These graphs indicate that average efficiency increases gradually reaching its maximal value (1.0) at λ = 0.23, distortion increases gradually from zero beginning at around λ = 0.15 and reaching 0.2 by λ = 0.5.

ranging from 0 through to 0.5 in increments of 0.01. Data was obtained through an exhaustive search of a two-dimensional salience space. Partial selection is predominant for low dopamine values, distortion and multiple-selection evident at high dopamine values. B. Average efficiency and distortion across all runs at each level of λ.

Figure 5 shows the average outcome at different levels of λ across all possible

dyads. In order to better understand the interplay between salience, simulated dopamine and selection, in

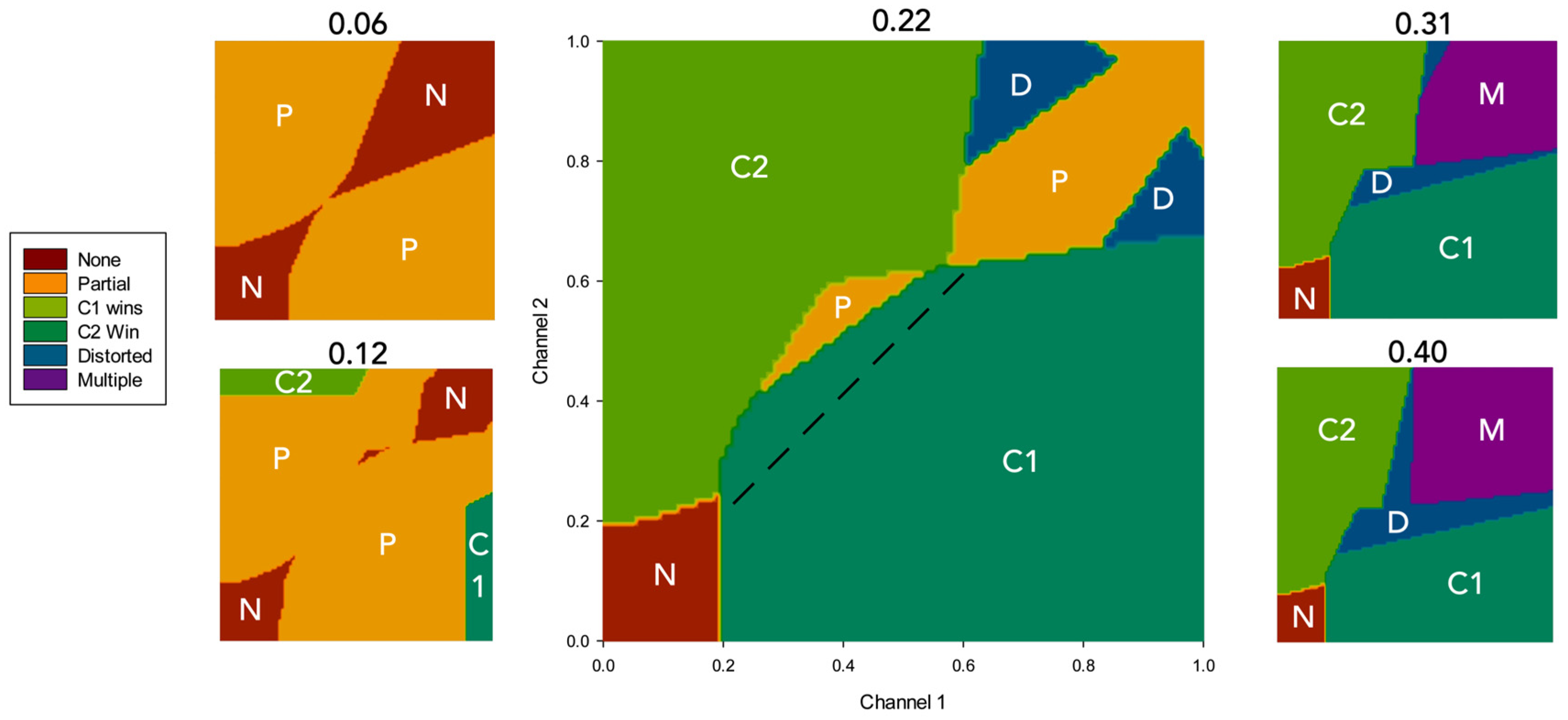

Figure 6 we show the outcome of the simulation for five specific values of simulated dopamine (λ= 0.06, 0.12, 0.22, 0.31, 0.40) but indicating the boundaries of different classes of selection outcomes on the

plane. For clean selection only, the plots also distinguish between selection of channel 1 (which is active first) and of channel 2 (which then competes for selection against channel 1).

Several properties of

Figure 6 are worth noting. First, at all levels of λ, there is little or no selection at very low salience levels. This is largely as a consequence of the threshold value of the model striatal input neurons which serves to weed-out weakly salient inputs. Second, with low λ (e.g. 0.12), clean selection (C1 or C2 in

Figure 6) occurs, if at all, only when there is a high salience input in just one channel, otherwise partial selection is the norm. Third, at all simulated dopamine levels there is no clean selection for strong, evenly matched, salience values (top-right corner of all plots). With low values of λ (0.06, 0.12) the outcome is no selection or partial selection of one or both channels, while with high values (0.31, 0.4) the result is distortion of the selected channel or multiple selection. The dotted line in the central plot (λ= 0.22) is shown to illustrate the extent of hysteresis in the model: channel 1 wins many selection competitions (encroaches across the diagonal) in which channel 2 salience is greater, purely because is was activated first.

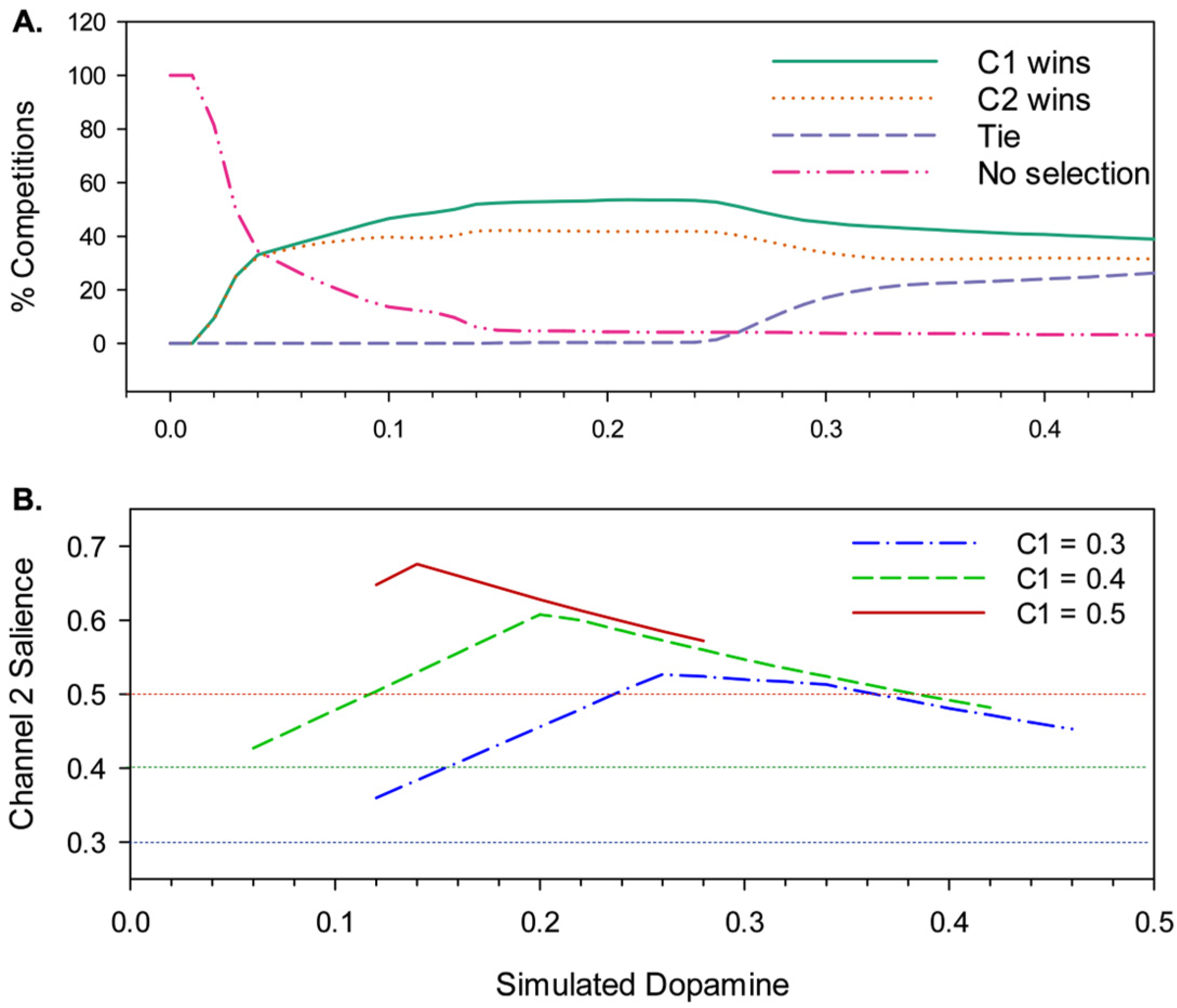

To further our understanding of hysteresis in the model, the simulation results described above were reclassified to show the extent to which channel 1, which is always active first, is preferred to channel 2 irrespective of the selection outcome. Thus, the result of each competition was rescored as either a

channel 1 win , a

channel 2 win , a

tie , or

no selection .

Figure 7a shows the results of this reclassification, and reveals that hysteresis is a property of the model for all but the lowest levels of simulated dopamine modulation (λ ≤ 0.06) with channel 1 consistently winning up to 10% more competitions than channel 2.

, required for channel 2 to prevail (i.e. e2>e1) against a channel 1 salience, , of 0.3, 0.4, or 0.5, for different values of λ. Data is shown only where there is a clear switch from channel 1 to channel 2 with increasing (i.e. without an intervening interval of no-selection or multiple selection). The degree of hysteresis varies depending on λ and , with the value of λ that generates maximum hysteresis decreasing with increasing .

However, this is still not the full story.

Figure 7b shows a further measure of hysteresis—the level of channel 2 salience required to overcome a given level of channel 1 salience—for three different initial, fixed levels of

. The plot shows that hysteresis is governed by a complex interaction of λ with salience, specifically, for values of

in the range 0.3-0.5 the degree of hysteresis first increases with increasing λ, peaks, and then decreases; at its maximum, channel 2 salience needs to reach 176% of the channel 1 salience in order to win the selection competition. The peak λ value for hysteresis also changes for different values of

—as the salience of the selected channel increases, the value of λ at which hysteresis is maximal goes lower.

We conclude that the relatively flat level of hysteresis shown across a broad range of λ values in

Figure 7a masks a significance dependency on salience. This outcome can be explained by understanding that hysteresis in the model occurs as a consequence of activity in the basal-ganglia-thalamo-cortical feedback loop (via VL and TRN in

Figure 1). Activity in this loop increases in proportion to reduced basal ganglia output, in other words, it increases with selection efficiency. With low values of λ, partial selection (low efficiency) predominates for low or intermediate salience values. This outcome results in less positive feedback via the thalamo-cortical pathway than with high salience competitions. Consequently, when λ is low, hysteresis will be maximal with high salience. In contrast, high λ levels result in high efficiency selection with comparatively low-levels of salience input thus generating substantial positive feedback and strong hysteresis. However, high-level salience competitions can result in the partial or full disinhibition of multiple channels (distorted or multiple selection), a consequence of this is increased TRN inhibition of the VL thalamus for the winning channel resulting in a significant reduction in thalamocortical feedback for that channel. This means that with higher levels of λ, the current winner can be more vulnerable to interrupt by its competitors.

In

Figure 5, clean selection for the disembodied model was above 75% in the range 0.2≤ λ< 0.3, fell steeply to zero in the lower range 0.0≤ λ< 0.2 and more gradually (to 55%) in the higher range 0.3≤λ≤0.5. Defining these ranges as, respectively, intermediate, low, and high λ, and building on the analysis just described (and in earlier explorations in [

36,

40,

41]), we can make the following hypotheses concerning the effects of varying simulated dopamine in the robotic model:

Hypothesis 1 (h1). At intermediate levels of λ(0.2≤λ< 0.3) we should expect to see a high proportion of clean selection with selected behaviors fully disinhibited and competing behaviors fully suppressed.

Hypothesis 2. At low levels of λ (0.0≤λ< 0.2) we should expect a predominance of partial selection or no selection (very low λ) and consequently the slowing or absence of movement.

Hypothesis 3. For high levels of λ0.3≤λ≤0.5) we should expect to see reduced inhibition of losing channels, leading to distorted or multiple selection, and resulting in motor commands that mix the movement requests of more than one action sub-system.

Hypothesis 4. At both low and high levels of λ, we should expect to see changes in the hysteresis of selected channels modulated according to the nature of the salience competition (e.g. whether the salience of competing channels is high or low, or evenly matched) as illustrated in

Figure 7b. Changes to hysteresis can be expected translate into consequences for action maintainence and for the timing of behavioral switching.

With respect to each of these hypotheses, the observed behavior of the robot may depend on a variety of factors related to its embodiment (discussed further below) and the requirement to generate sequences of integrated behavior. Moreover, whereas the above analysis was based on an exhaustive search of an essentially two-dimensional salience space, the robot model samples behavior-dependant trajectories through a five-dimensional salience space. The actual outcomes with respect to hypotheses 1-4 are therefore only partially predicatable from the disembodied model and to be further determined from observation.

5. Selection in the Neurorobotic Basal Ganglia Model

Based on our analysis of the disembodied model we decided to test the robot for 30 trials each at low, intermediate and high simulated dopamine levels, with five trials, each lasting 120s, at each of 18 different values of λ: low= 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, 0.12, 0.15, 0.18, intermediate= 0.20, 0.21, 0.22, 0.23, 0.25, 0.28, and high= 0.31, 0.34, 0.37, 0.40, 0.43, 0.46. The robot started each trial in the centre of the arena, facing one of the four walls, with four cylinders placed 18cm diagonally in from each corner (

Figure 2, right).

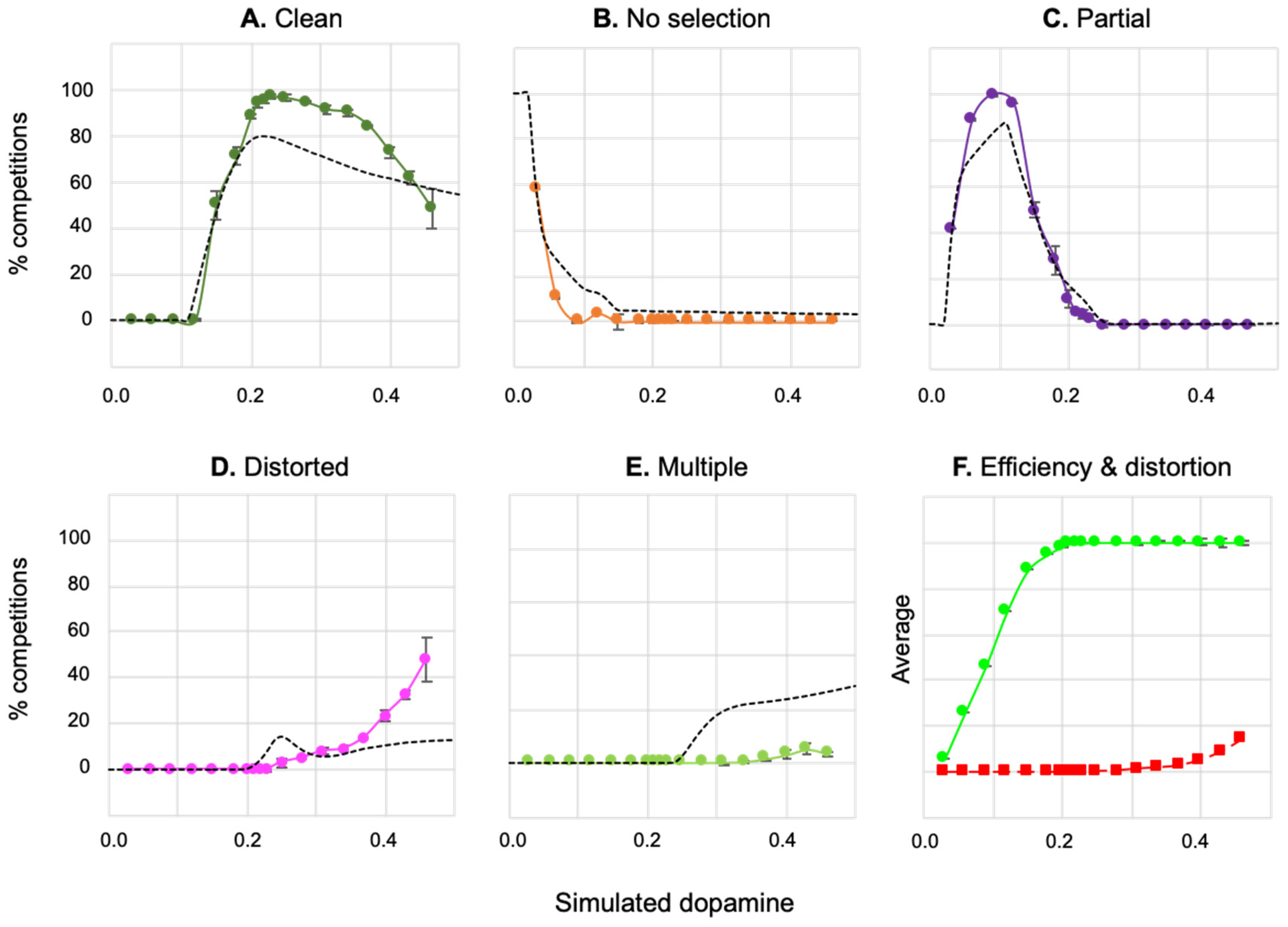

In each, trial, which typically consisted of around 800 robot time-steps, the outcome of the basal ganglia selection competition, at each time-step, was classified according to the selection criteria specified above. For each λ value, the percentage of time-steps resulting in each type of selection outcome was then averaged across all five trials regardless of the behavioral outcome on individual trials (which we consider next). The results of this analysis are shown in

Figure 8a–e together with a plot of average efficiency and distortion across the different λ levels (8f).

These results shows the expected similarity between the selection profiles for the robotic and non-embodied models, nevertheless there are some important differences. These include, in the robotic model, an increased proportion of partial selection at low λlevels (0.03 ≤ λ≤ 0.12), of clean selection at intermediate and moderately-high levels (0.2≤ λ≤0.4), and of distorted selection at high levels (0.3 ≤ λ≤0.46). There is also an almost complete absence of multiple selection at high λ levels. Whilst average efficiency is similar across the robotic and disembodied models, the robot model overall has less distortion except at the highest λ levels. In the intermediate range of simulated dopamine (λ0.20–0.29) clean selection for the robotic model is in the range 89-95% compared to 73-81% clean selection for the disembodied model.

These results largely reflect the fact the robot model is spending little time sampling the very high salience areas of the state-space, or the very low salience areas, compared to the exhaustive search conducted for the disembodied model. This was confirmed by an analysis of salience values across 15 runs (one at each level of λ) which found that 95% of selection competitions were in the range 0.3–0.75 for the winning channel and 0.2–0.7 for the strongest losing channel (see also [

36] for a plot of how the salience space is sampled by the robot model). Note that that there may also be up to five channels with non-zero salience at any time compared to just two in the disembodied model.

Effects of simulated dopamine modulation on behavioral outcome

Our previous robotic study of the basal ganglia [

36] showed that an embedded basal ganglia model was able to generate integrate behavior in our biology-inspired foraging task and for a specific intermediate value of simulated dopamine (λ= 0.20). In the current study, we address the question of how varying simulated dopamine impacts behavioral integration, and seek to describe and understand a variety of distinctive patterns of behavioral disintegration that arise when simulated dopamine is reduced or increase relative to this baseline.

To begin this analysis a simple binary classification scheme was developed and applied to the 90 robot trials described above, evaluating each trial according to its success in achieving higher-order behavioral goals. Specifically, we define ‘integrated behavior’ for this task as constituting, at minimum, successful avoidance in the initial ‘high fear/low hunger’ phase, and a successful foraging sequence in the later ‘low fear/high hunger’ phase. Operationally, we define:

- (i)

successful avoidance as activity resulting in the discovery of a wall (ignoring any cylinders encountered en route) followed by movement some distance along the wall’s length, and

- (ii)

successful foraging as activity resulting in the deposition of a cylinder in a ‘nest’ area.

This classification scheme proved to be sufficiently simple to be applied during live observation of robot behavior, in addition, automatic logs were recorded detailing the robot’s sensory, motivational, and basal ganglia state at each time-step, and the bout structure of its behavioral selections, allowing us to reconstruct and analyse the robot’s behavior post hoc.

The outcome of our initial analysis was as follows. Seven levels of simulated dopamine (0.20–0.28 and 0.37) were scored as generating successful behavior on all five trials, five levels (0.03–0.12 and 0.46) were unsuccessful on all trials, and the remaining six levels (0.15, 0.18, 0.31, 0.34, 0.40, 0.43) generated a mixture of successful and unsuccessful trials.

In order to better understand what was happening at levels of λ that generated mixed results, a quota sampling strategy was implemented in which further trials were conducted until a total of five successful trials, at each of these levels, had been achieved. This required between 1 and 11 trials per level, resulting in an additional 26 trials.

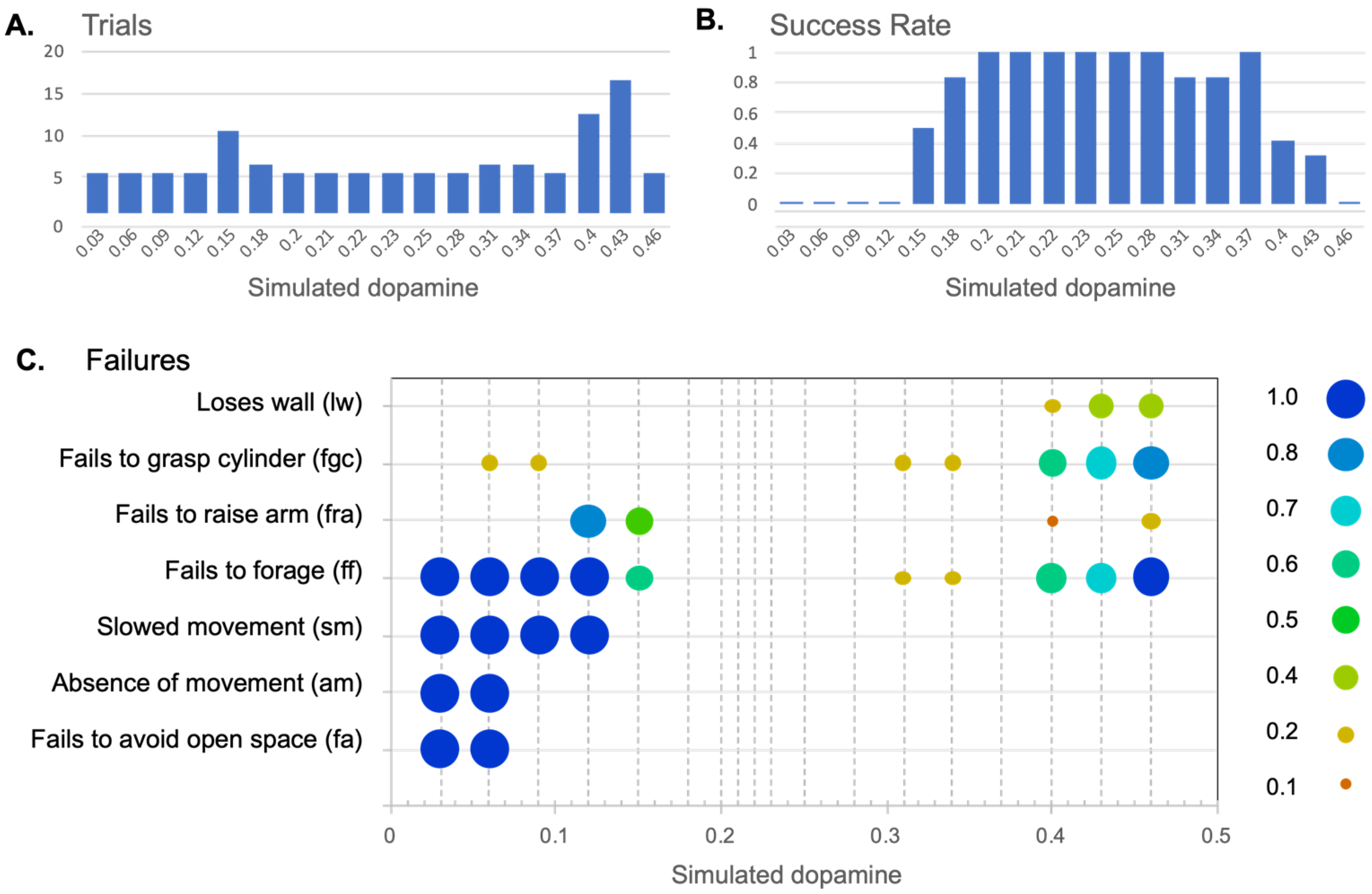

Figure 9 shows the total trials (9a) the overall success rate (9b) at different levels of λ, across all 116 trials, assessed against the criteria of success in both avoidance and foraging.

Figure 9c shows a more detailed analysis of types of failures under the low and high λregimes that we describe further below.

Figure 9b confirms that the in the range of intermediate λvalues (0.2–0.28), that generates a high proportions of clean selection in

Figure 8, the robot also reliably generates integrated sequences of behavior. The absence of any failures in the 30 trials in this range provides a 95% confidence level that the failure rate for this class of models is 10% or less.

In the remainder of this section we consider the nature of the failures in behavioral integration that occur with levels of λ below or above this intermediate range then explore the effects of simulated dopaminemodulation on the timing and frequency of behavior switching.

Figure 9c provides an analysis of the types of failure of behavioral integration observed at different level of λ, and as described in

Table 1.

Figure 10a–e shows some example runs, recorded with low and high λ, that help to illustrate the robot behavior observed at different levels of simulated dopamine.

In the statistical analyses reported below we use an alpha value of 0.05 and report significance values as two-tailed. If Levene’s test is significant then we report “equal variances not assumed” and provide adjusted degrees of freedom and p-values.

Behavioral consequences of low simulated tonic dopamine (λ< 0.2)

Slowed movement and periods of inaction. In section 4 we showed that the model basal ganglia generates partial (low efficiency) selection for low levels of simulated dopamine. Since our robotic model employs the basal ganglia output as a gate on targeted motor systems, the consequence of partial selection in behavioral terms should be that this gate is not fully opened for winning competitors; motor acts should be slowed or even extinguished altogether. This expectation, noted as hypothesis 1 above, was borne out in our study (see

Figure 9c) which saw the expected translation of partial/weak selection into slowed movement (sm) for all runs at λ level 0.12 or lower. At λ= 0.06, 0.03 the robot is moving too slowly to complete a successful foraging sequence in the time allowed, thus failing altogether on the criterion for successful avoidance (fa). Periods during which the robot makes no movement (am), despite being otherwise sufficiently motivated, are seen at λ= 0.06 (average of 14s per trial, compared to 2s for intermediate levels of λ) and for longer spells at λ= 0.03 (average of 38s per trial). Note that it is possible to distinguish between the dysfunctional absence of movement due to low λ as seen in

Figure 10a, and its appropriate absence during periods of low motivation (as in the period of no selection for λ= 0.20 in

Figure 4). The

Supplementary Video (part 4) shows an example of slow movement and no movement for an example run with λ= 0.10.

Premature deselection. In the range λ= 0.06–0.15 behavior can break down as the result of the premature deselection of an ongoing behavior, this can be seen as a failure of persistence or action maintenance. At λ= 0.09 or below this typically occured during the initial wall-seek bout leading to an absence of movement and failure to reach the wall as noted above. A further point of vulnerability was seen in the range λ= 0.09–0.15 and occured when the robot attempted to execute the

cylinder pickup FAP but either failed to grasped the cylinder (

fgc in 9b) or failed to raise the gripper arm at the end of cylinder-pickup bout (

fra in 9c). An example of the

fgc failure is shown in the

Supplementary Video (part 5). Failure to raise the gripper arm occurred in 80% of trials at λ= 0.12 and 50% of trials at λ= 0.15, and also resulted in a

behavioral trap, as described in Appendix 1, where the robot detected its lowered arm as an obstacle and engaged in a slow circling behavior until the end of the trial.

Failures more likely at low salience levels. Our experiments show that, at low λ,weakly selected behaviors are typically not executed with sufficient vigour and can be vulnerable to interrupt, further investigation also shows support for hypothesis 4—that the effects of varying simulated dopamine can also depend on salience level. Specifically, comparison across the 10 trials at λ= 0.15 shows that the variability in outcome (successful vs. unsuccessful) resulted from differences in the timing of the initial

cylinder-pickup bout across trials—the robot encountered a cylinder, and initiated the cylinder-pickup FAP, significantly

later in the successful runs (M= 66.7s, SD= 6.88) compared to the unsuccessful runs (M= 52.0s, SD= 2.23) (independent-samples t-test: t(4.8)= 4.557, p=0.007, equal variances not assumed). Recall that the salience of

cylinder-pickup increases with simulated ‘hunger’, which in turn increases gradually with longer search times. In other words, for those runs at λ= 0.15 in which a cylinder is discovered quickly, and in which the robot is therefore more likely fail through premature deselection, the selection of the cylinder-pickup behavior is at a

lower salience level than for the successful trials (longer search durations). This can be related to

Figure 7b which showed reduced hysteresis, and hence less behavioral persistence, for low values of λ (compared to intermediate values). More generally, in all low λ conditions, robot behaviors are executed more efficiently at higher salience levels, and therefore the symptoms of reduced simulated dopamine such as slowed movement are more pronounced when salience is low.

Behavioral consequences of high simulated tonic dopamine (λ> 0.3)

Distortion of winning channels by active losers. At high levels of λ the non-embodied model predicted reduced inhibition of the motor output from losing channels leading to distortion of the winning action (hypothesis 3). The behavioral consequences of distortion are visible in the robot model with levels of simulated dopamine λ≥ 0.31 and occasionally resulted in behavioral disintegration for λ0.31, 0.34 through failure to complete a foraging bout (

ff in

Figure 9c). Likelihood of failure increased with very high levels of λ with more than 50% fails at λ0.4, 0.43 and 100% fails at λ0.46. At all of these λlevels, failure to forage was typically due to an inability to grasp a cylinder (

fgc), however, other evidence of behavioral disintegration was also evident, particularly, difficulty in tracking walls (

lw). Failure to grasp a cylinder oftens results in a second form of

behavioral trap where the robot enters repeated cycles of

cylinder-seek and (unsuccessful)

cylinder-pickup, an example of this is shown

Figure 10e (t= 85-120s), an example of this type of failure is shown in the

Supplementary Video (part 6).

Failure more likely at high salience levels. That there was a mix of successful and unsuccessful runs, at some high λ levels, indicates that the impact of distortion on behavioral outcome can depend on circumstances. We illustrate this by comparing, in

Figure 10d,e, two trials with λ= 0.31 showing that both successful foraging (10d) and disintegrated foraging (10e) are possible at this level. In 10d, the robot quickly locates a cylinder at t= 49s, in 10e, the only unsuccessful run at this λ level, there is a much more protracted

cylinder-seek search ending at t= 84s (see Appendix 1 for a detailed commentary and comparison). At higher λ levels (0.40 and 0.43), comparison of successful (M= 37.1s, SD= 6.06) vs. unsuccessful trials (M= 63.3s, SD= 16.4) shows that, on average, in successful runs the robots discovered a cylinder whilst foraging

earlier than in unsuccessful trials (independent-samples t-test: t(18)= -4.741, p<0.001). This is the reverse of the situation with low λ—with high simulated dopamine it is the longer search bouts, giving rise to higher salience levels (from increasing ‘hunger’), that tend to result in greater behavioral disintegration. This again matches hypothesis 3—that the effect of varying simulated dopamine on behavior will depend upon salience levels—with contrasting effects seen at low and high λ levels.

From

Figure 7b, we can expect reduced hysteresis (behavioral persistence) for higher levels of λ, however, that figure also shows that increasing salience at high λdoes

not significantly impact on hysteresis. To understand why the robot performs better at lower levels of salience with high λ we therefore need to look beyond the basal ganglia model itself and to consider the influence of distortion on behavioral persistence via its effect on behavior. This is the topic of our final analysis.

Effects of distortion on behavioral persistence

A key property of the robotic model, that distinguishes it from the non-embodied simulation, is that selection outcomes have behavioral consequences that shape the robot’s subsequent sensory experiencies. More specifically, the robot’s motor output, in part, determines its trajectory through the state-space of perceptual and motivational affordances for future selection competitions. Since varying the level of simulated dopamine can influence motor behavior by slowing movement or by merging partially selection actions with winning ones, it is interesting to establish whether this has any significant consequences for the selection behavior of the embodied model.

Here we explore this issue by examining the some effects of distorted selection on the timing and frequency of behavior switching. To assist this analysis an additional 90 robot trials were performed at all of the λlevels previously tested, but this time with a ‘winner-takes-all’ filter applied to the efficiency values of all sub-systems, such that the winning sub-system was always assigned an efficiency of 1.0, and all losers an efficiency of 0.0. In the following analyses the behavior of this winner-takes-all variant will be contrasted with the ‘soft’ selection generated by the standard model that allows multiple channels to influence motor output.

Timing of behavior switching. Our investigation of the non-embodied model showed significant hysteresis at almost all levels of simulated dopamine in the context of closely-matched salience competitions (

Figure 7), this should show up strongly, in the robot model in the initial transition from avoidance to foraging behavior. The key competitors at this point are wall-follow and cylinder-seek and the prime determinant of their relative salience, that eventually allows the latter to prevail, is a gradual, time-determined reduction in ‘fear’ alongside a steady increase in ‘hunger’. The length of the time leading up to this switch from avoidance to foraging therefore provides an measure of the operation of behavioral persistence in the model.

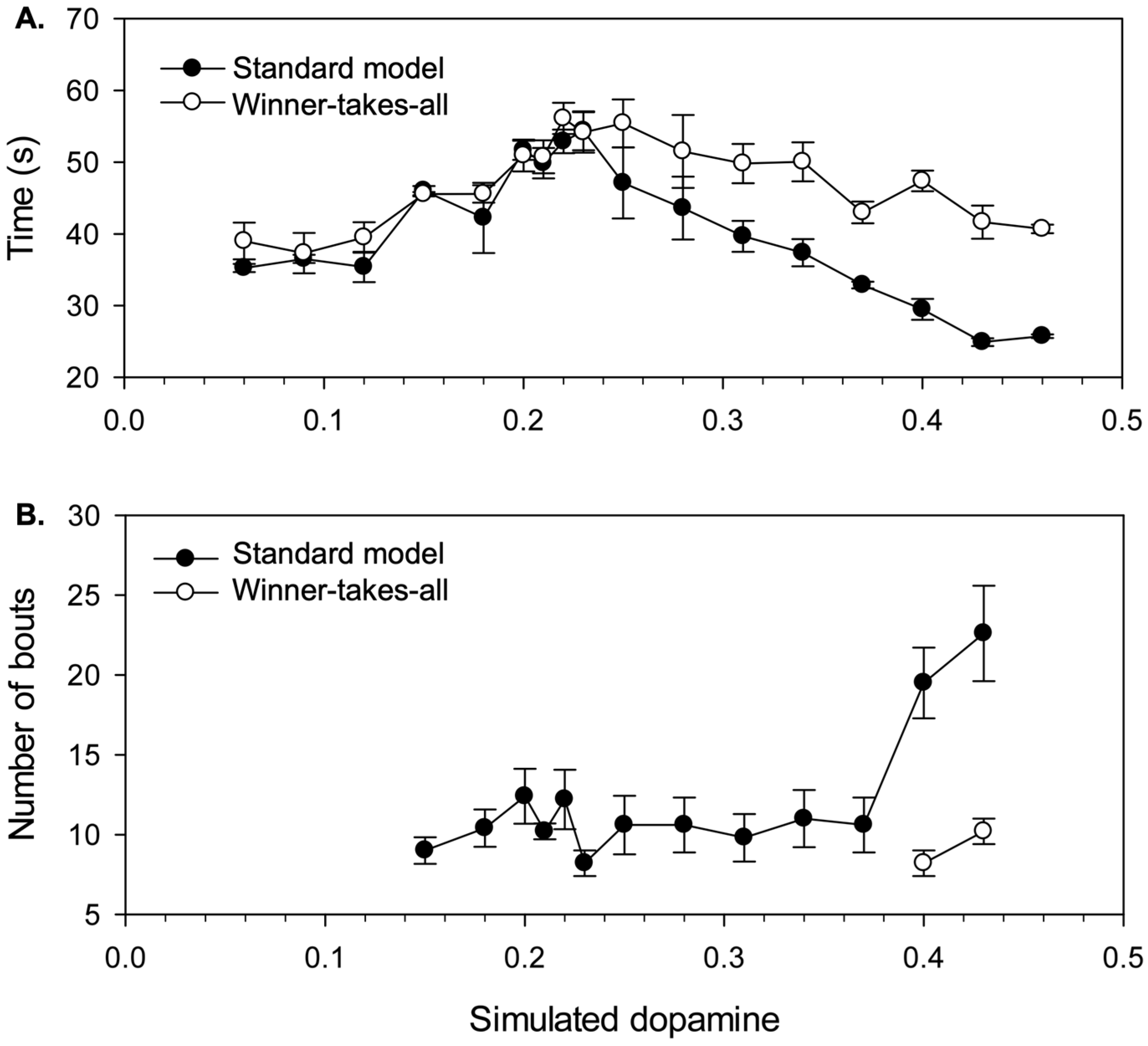

Figure 11a plots this ‘time-to-switch’ measure against different levels of λ and shows the different outcomes observed with both the standard model (from the original set of 90 trials) and the new winner-takes-all control. For each dopamine level we plot the average and standard error of the time-to-switch calculated over the five trials.

Comparison with

Figure 7b, shows that the graph for the winner-takes-all variant provides a good match to the degree of hysteresis found for a fixed salience (on the initial winning channel) of 0.4. Since the salience of wall-follow preceding the switch is typically in the range 0.3–0.4, this demonstrates that hysteresis in the embodied model basal ganglia generates a corresponding level of behavioral persistence under winner-takes-all conditions. However, the standard model generates an interesting difference from this result. Specifically, two-way ANOVA shows a significant interaction (F(1,16)= 3.641, p<0.001) between model type (standard vs. winner-takes-all) and λ. Posthoc comparisons for low, intermediate and high λ values, show a difference for high values only (λ≥ 0.31) where switching occurs significantly earlier in the standard model (M= 31.7s, sd=6.26) compared to the winner-takes-all variant (M= 45.4s, sd= 5.66) (independent-samples t-test: t(58)= -8.92, p<0.001). We conclude that, with higher λ, the distortion provided by losing channels can significantly reduce behavioral persistence in the robot over and above the reduction resulting from lower hysteresis in the embedded basal ganglia at higher levels of simulated dopamine.

Looking at

Figure 10 (panels d and e), which showed behavior for two trials with λ=0.31, we can observe, towards the end of the wall-follow bout (around t=30), a small, but gradually increasing, output on the cylinder-seek channel. It is this ‘leakage’ of motor output from the cylinder-seek sub-system that constitutes the difference between the standard and winner-takes-all versions of the model. A key to understanding the effect of this distortion is to note that the wall-follow behavior is not especially robust, and is sometimes pushed off track by sensor noise or wheel-slip even when driven by a clean motor signal. The effect of the motor noise introduced by partial selection of cylinder-seek is therefore to increase the variability in the robot trajectory making it more difficult to maintain sensor contact with the nearby wall. In this situation, any loss of the wall percept due to distorted movement will lead to a rapid reduction in wall-follow salience and a switch to the cylinder-seek behavior.

Increased switching frequency with high simulated dopamine. If distortion makes some behaviors more vulnerable to interrupt, then we might also expect increased levels of behavior switching. To investigate this possibility,

Figure 11b illustrates one specific measure of switch frequency, the total number of bouts occurring during the first avoidance sequence and first foraging sequence of each trial. This measure was preferred to counting bouts (or switches) within a fixed time interval as it allows us to exploit a useful base-line—integrated behavior (by our earlier operational definitions) requires a minimum of seven bouts across these two sequences.

Since this measure can only be applied to trials containing a completed foraging sequence, this analysis only considered λ values in the range 0.15–0.43, and the graph plots the average and standard error of the number of bouts observed for the five successful trials at each simulated dopamine level. These data reveal that the performance of the robot is slightly above the base-line level of seven bouts across most of the range of simulated dopamine values, however, the number of bouts increases substantially for very high λ levels (λ= 0.40, 0.43; M= 21.3 bouts, SD= 4.73). Moreover, as shown in

Figure 11b, comparison with winner-takes-all selection at these levels (M= 9.2 bouts, SD= 1.99) shows that the latter requires significantly fewer bouts (independent-samples t-test: t(2.22)= 4.33, p= 0.041, equal variances not assumed). We therefore conclude that the increased switching seen with the standard model is largely due to the distortion of motor output created by losing competitors.

Figure 10e shows an example run with λ= 0.40 that illustrates the increased frequency of bout switching (between wall-seek and wall-follow in t= 0–50s) that can occur due to distortion with high simulated dopamine.

These analyses of the effects of increased λ on switch timing and frequency demonstrate that distortion in the robot model does not inevitably lead to a mixed motor output—trying to do two things at once—instead, its effect can be to make certain behavioral states more vulnerable to interrupt which can then lead to an increased frequency of behavior switching.

5. Discussion

Robotics can play an important role in neuroscience through its ability to create computational models of the nervous system that are

embodied, that is, they control physical devices (robots) that exists in the world, and

situated, that is, they must engage in real-time, and in closed sense-action loops, with the environments in which they are placed [

59,

60]. Robotic models, like animals, can display

integrated behavior, where they generate sequences of actions that are coherent with both their internal motivations and the unfolding dynamics of the world [

45,

61]. Conversely, their behavior can become

disintegrated when action sequences fall out-of-step with the affordances of the environment and they fail to achieve their goals [

36]. The study of robotic models therefore offers opportunities for comparisons with animal and human behavior that differ from those that are available from the non-embodied models more typically studied in computational neuroscience. For instance, we can study them objectively, as behaving systems, without having to place an interpretation on their inputs and outputs [

62,

63]. We can also examine the consequences for this observable behavior of specific interventions that simulate changes to the nervous system studied in relevant animals models, or that might arise in human neurological disorders.

Effects of simulated dopamine modulation on robot behavior

In the current study we explored the capability of an embedded basal ganglia model to generated patterns of integrated behavior when operating across a range of simulated tonic dopamine levels (λ). The robot performed the intended avoidance and foraging behaviors successfully for a range of intermediate λ values (0.2-0.28), values below this range caused some slowness of movement, in line with previous predictions from non-embodied models, with movement speeds falling below 75% of its intended vigor at around half of this range (λ= 0.12), and with prolonged periods of no movement for very low λ values (0.06 or less). Some runs with low λ also resulted in the premature deselection of behavior. High values of λ (0.3 or greater) lead to some distortion of motor output as the result of partial (or full) selection of multiple competing action sub-systems.

We found that simulated dopamine modulation of action selection outside the intermediate range did not invariantly lead to behavioral disintegration, since its effects varied with the precise circumstances of the robot. Specifically, low λ systems functioned well (selecting cleanly) with high salience signals but poorly with weak salience inputs. Conversely, high λ systems generated cleaner selections at low salience levels. While expectations from non-embodied modelling (hypotheses 1-4 above) were borne out in the robot implementation, the performance of the robot, across the full range of λ values, was better than might have been predicted from prior analyses of the selection properties of the model basal ganglia. This result can be explained by the finding that the robot, through its behavior, “self-structures” its own input [

64], sampling only a limited area of the state-space of salience competitions, and predominantly parts of the space that have better-than-average outcomes (in terms of effective selection).

Hysteresis in the non-embodied model translates into persistence in behavioral expression in the robot. Persistence varied in an interesting way with λ, in a manner only partially explained by the behavior of the embedded basal ganglia model. Persistence was maximal at an intermediate λ levels, with reduced persistence at both lower and higher levels that could be traced to the functioning of the basal ganglia-thalamocortical loop. For high λ, reduced persistence was also partly the result of motor distortion making the current behavior of the robot more vulnerable to interrupt. This is an outcome that was not predictable from the disembodied model. Very high levels of λ also produced an increase in behavior switching within extended sequences of goal-directed activity. Again, this result is not entirely predicted by the disembodied model which forecast a greater degree of distortion (mixed behavior) at high λ values as a result of partial or full selection of multiple competitors.

Dysfunction of basal ganglia dopaminergic function in animals and humans

Dysfuntion of dopaminergic regulation of the basal ganglia is implicated in a range of neurological disorders [

35]. In Parkinson’s Disease (PD), for instance, tonic dopamine depletion in the striatum is one of the primary drivers of symptoms, including those relating to impaired movement and difficulty in initiating movement [

65]. In computational neuroscience models, the progressively debilitating effects of PD have been modelled as increased attenuation of tonic dopamine in the striatum [

66,

67,

68]. ADHD, which is characterized by hyperactivity, impulsiveness, impaired attention, and executive dysfunction, has also been linked to dopamine dysregulation, and particularly, to increased levels of dopamine transporter that remove dopamine from the synapse [

35]. This outcome has been modelled as resulting in a less pronounced (compared to PD) reduction in striatal dopamine [

69]. In schizophrenia, by contrast, an up-regulation of dopamine is thought to underlie symptoms related to disorganization including expression of bizarre or inappropriate behavior [

35,

70], this has been modelled as involving an increase in striatal dopamine [

71]. Tourette’s syndrome which causes sufferers to make involuntary movements or sounds has also been characterized as a consequence of elevated striatal dopamine [

71,

72]. Other motor dysfunctions such as chorea and dystonia have been hypothesized to involve a failure to inhibit unwanted movements in which dopamine dysregulation could be implicated [

7]. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is thought to involve hyperactivity in parts of the obitofrontal cortex, and treatments involving dopamine antagonists have been found to augment the benefits of therapies involving seretonin reuptake inhibitors [

73].

A large number of animal models have been developed to investigate the neurological bases for these disorders many of which have explored genetic, developmental, drug or lesion-induced alterations to the dopamine system [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Animal studies have also directly explored the role of dopamine in regulating action selection and motivated behavior [

79,

80,

81,

82]. In the remainder of this discussion we briefly compare results with the robot model with animal studies and human neurological disorders thought to involve lowered or heightened levels of tonic striatal dopamine.

Dopamine-depleting interventions and neurological conditions associated with reduced striatal dopamine

Behavior execution. In animals, activational aspects of motivation, such as response rate, vigor, and persistence, are impaired at doses of DA antagonist that leave intact directional or goal-directed aspects of responding (for review see [

9,

12,

16,

81]). In patients with PD, major symptoms include slowness in movement (bradykinesia), reduced size of movement (hypokinesia), and absence of movement (akinesia) [

83]. Consistent with these findings, in the robot model, slowed movement was a visible consequence as λ was lowered below the intermediate range, often leading to more prolonged bouts of behavior as action sequences take longer to perform. As λ was further reduced, movements were only partially executed or even fully suppressed, despite high-levels of motivation.

Salience. In animal models, behavior evoked by events that have high biological salience are comparatively resistant to dysfunctional dopamine neurotransmission. Thus, complex learned responses to mild stimuli are more prone to disturbance than unlearned responses evoked by intense unconditioned stimuli [

12]. Similarly, behavior directed by external sensory stimuli is less affected than internally motivated (interoceptive) behavior [

15,

21]. Consummatory behaviors (e.g. eating, drinking) are less disrupted than preparatory behaviors (acts that lead to, or make possible, consummatory behaviors) [

10,

16,

20,

84,

85]. For example, while lesions of the mesolimbic dopamine projection abolish food hoarding in rats, actual feeding and drinking remain relatively unaffected [

85]. High levels of arousal evoked by painful or highly arousing stimuli (such as being plunged into a icy bath) can lead to the restoration of normal behavioral responses (such as swimming) in otherwise akinetic animals caused by lesions that effect the dopamine system [

24,

86]. Patients with PD often show problems in initiating movement, however, salient visual stimuli such as stripes painted on the floor can facilitate initation of walking and reduce the incidence of freezing of gait [

87]. Patients with PD can also show “paradoxical kinesia” (close to normal movement) in times of acute stress, for example when escaping from fire [

88]. Salience competitions appear to have a deleterious affect on patients with PD that is more marked than in controls, for instance, a stimulus such as a doorway can have an inhibitory effect on movement, causing some patients to freeze; irrelevant stimuli have also been found to increased reaction times in a manual response task [

87]. More broadly, patients with PD can also have difficulty expressing two motor programs simultaneously [

83,

89].

Our robot model casts interesting light on some of these findings. For instance, we found that, with low λ, behavioral selections made between highly salient competitors were less vulnerable to partial selection, or no selection, than those made on the basis of low salience competitions (

Figure 6). High levels of motivation also led to a general increase in salience for competing behaviors and consequently clean(er) selection. We also found that selection in the low-λ robot was impaired by increased salience of a competitor, in some situations this led to freezing where competitors were evenly matched (e.g.

Supplementary Video, part 4). More generally, at low λ levels, selection of the winning channel was more impacted by the presence of activity in competing channels than in similar circumstances but with λ in the intermediate range.

Lack of persistence. Rats with reduced dopamine show difficulty in maintaining motivated behavior over time. For instance, Gaddy and Neill [

17] showed that dopamine-deprived animals had impaired performance of behaviors requiring sustained effort, whilst Salamone [

10] found increased frequency of unfinished feeding bouts (partially-eaten food pellets) and failure to carry food pellets to normal feeding loci. Patients with PD often make incomplete movements and can exhibit sudden freezing, they also show rapid fatigue and can have difficulty in maintaining a behavior over time. For example, in the case of hand writing, for many patients their letters become smaller and smaller (micrographia) before writing ceases altogether [

90]. In the robot model we found that low λ makes the currently selected behavior more vulnerable to early deselection or interrupt, largely as the result of decreased thalamocortical feedback failing to maintain the selected behavior. A similar challenge could underlie the premature deselection of behaviors seen in PD [see 83] and the increased distractibility, and lack of persistence, associated with ADHD. As illustrated in

Figure 7b, hysteresis in the basal ganglia falls of quite quickly as λ is reduced, including for values in the intermediate range when salience is at a moderate level. This is consistent with the obversation that individuals with ADHD show problems with behavioural persistence without the motor symptoms (bradykinesia etc) associated with more profound deficiencies in striatal dopamine.

Behavioral timing. Studies with animals provide inconsistent evidence regarding switching frequency and time to initiate behaviors, with outcomes varying with experimental set-up [

10]. In the robot model we found that time-to-switch depends on the salience of the behavior and on that of its competitors. This may help explain inconsistent findings in humans and animals. For example, in PD there is evidence that while some visual saccades are slowed, others are made more rapidly (hyper-reflexively) than in controls. Through meta-analysis we previously demonstrated that latency to saccade was dependent on the size (eccentricity) of the saccade, with smaller saccades more likely to be hyper-reflexive [

91]. We suggest that this outcome arises because the current fixation behavior is more vulnerable to early interrupt due to reduced hysteresis in the relevant basal ganglia loop.

Dopamine increasing interventions, and neurological conditions involving increased striatal dopamine

Response frequency and duration. Animals treated with dopamine agonists show increases response frequency alongside decreased response duration with increases in dose [

92,

93,

94]. Seen in the context of our robot study this is consistent with our finding of reduced time to switch and increase in distractibility and number of bouts with high levels of λ (see

Figure 10e and

Figure 11).

Suppressing unwanted actions. A common feature of neurological disorders involving increased striatal dopamine is difficulty in suppressing unwanted actions and thoughts. These can include the more stereotyped forms of unwanted action or speech seen in Tourette’s syndrome, as well as the short twitch-like movements seen in chorea and thought to resemble fragments of normal behaviors, and perhaps some of the intrusive thoughts and bizarre actions associated with schizophrenia. In the non-embodied basal ganglia model elevated λ levels resulted in simultaneous selection of multiple channels, an outcome that has some resemblance to dystonia. However, the robot model generated a somewhat different result including patterns of rapid switching between channels, indicating that interruption of ongoing behavior is made more likely by the motor interference generated by a partially selected competing channel. The more promiscuous forms of selection enable by higher dopamine levels mean that patterns of behavior whose salience activity is “bubbling below the surface” may find an opportunity for expression due to a momentary loss of attention or concentration.

Stereotypy and hyperactivity. At higher doses of DA agonist, animals typically express a narrower range of behaviors and can become fixated on certain action patterns, that have become known as stereotypies. These may be oral (e.g. licking, biting, and gnawing) but that can also include forms of repetitive movement, including running [

95], that are matched to environmental affordances. For example, Kelley et al. [

94], summarising results with a hole-board task, commented that “with the higher doses [of amphetamine], locomotor routes become shorter and animals focalize uniquely on the holes (but still maintaining some locomotion and shifting from hole to hole) […] residual components of the original behavior remain, but their pattern is greatly altered” (p. 73). Dopamine transporter (DAT) knockout mice, which have levels of striatal dopamine that are elevated by 70%, show hyperactivity and reduced habituation when placed in a novel environment [

96], while DAT knockout rats are less sensitive to reward than wildtype animals, and show rigidity of action choice, alongside, hyperactivity, choice pattern and compulsive stereotypies [

97].

Dopamine agonist-induced stereotypy in animals has been seen as a model for schizophrenia—though schizophrenics typically do not exhibit motor stereotypies, their symptoms often do involve compulsive and repetitive patterns of behavior and thought [

93]. Repetitive sequences of actions, including constrained exploration patterns within an open environment, have been observed in rats treated with the DA agonist quinpirole and have been compared to the rituals seen in people with obsessive compusive disorder [

95].

Qualitatively, the behavior of the robot model at the highest λ trials (e.g.

Figure 10f) bears some resemblance to patterns on behavior in hyper-dopaminergic animals—the actions of the robot sample a narrow range of the potential actions, resemble some elements of complete action patterns but are fragmentary, poorly organized and fail to achieve goals (see, e.g.

Supplementary Video, part 6). The underlying cause of the behavioral disintegration is selection (full or partial) of multiple channels, leading to early interrupt of ongoing behavior or mixing and distortion of motor acts. In animals, removal of basal ganglia inhibition from the motor system, will lead to complex effects as selection of behavior is governing by multiple brain systems, including attentional mechanisms, which we might consider as ‘early’ selection, and brainstem and motor components, that may provide forms of ‘late’ selection [

98].

Limitations and related work

The current model can be improved along a considerable number of lines. First, whilst the Gurney et al. model of basal ganglia employed here has been shown to have enduring appeal, there a multiple ways in which it has been improved and extended that could be integrated into a future robot embodiment (see [

99]). For example, a richer model of D1/D2 receptor behavior (see [

100]) could impact on the behavior of a robotic model, as has been investigated for a simulated robot by Bahuguna et al. [

101]. There is also scope to develop the wider architecture. For instance, whilst the current model builds on our understanding of dorsal basal ganglia pathways, the ventral basal gangla domain shows important similarities and differences, and significantly, plays a critical role in the regulation of dopamine neurons [

102].

Our robotic modelling demonstrates the importance of understanding how selection circuitry interacts with wider sensorimotor systems in the brain. Elsewhere, we have explored this in the context of cortical and sub-cortical loops involved in the selection of eye movements in a robotic active vision model [

103,

104], and in the control of whisker-guided behaviour in robots with moving vibrissae [

105]. A simplified version of the current model has also been deployed in a commercial biomimetic animal-like robot controlled by brain-inspired layered architecture [

106]. Other interesting work in this direction includes models of basal ganglia interactions with locomotor pattern generators systems such as those underlying lamphry swimming [

107]. For a more complete brain-inspired architecture that includes a basal ganglia model of action selection see [

108].

The current model highlights the importance of understanding how drive systems in the brain interact with action selection mechanisms. In place of the proxy models of drives used here, future models could usefully explore drive models based on a more realistic model of energy management (e.g. [

109]). Another interesting direction to explore is the interaction of the basal ganglia with other brain substrates involved in motivational and action selection. For example, in [

110] we developed a layered model of the hypothalamus that models the interplay of hunger and satiety in a simulated foraging task, the model also operates to regulate the activity of simulate dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Variability in the tonic dopamine signal could be an interesting target for modelling as it is known to be impacted by task engagement, motivation and arousal systems, stress and reward [

111,

112,

113] and has been shown here to have a significant interaction with salience in supporting effective selection. Finally, action selection is also impacted by other major neuromodulatory systems besides dopamine [

114] as has been explored in a robotic model by Krichmar [

115].