Submitted:

07 January 2024

Posted:

08 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

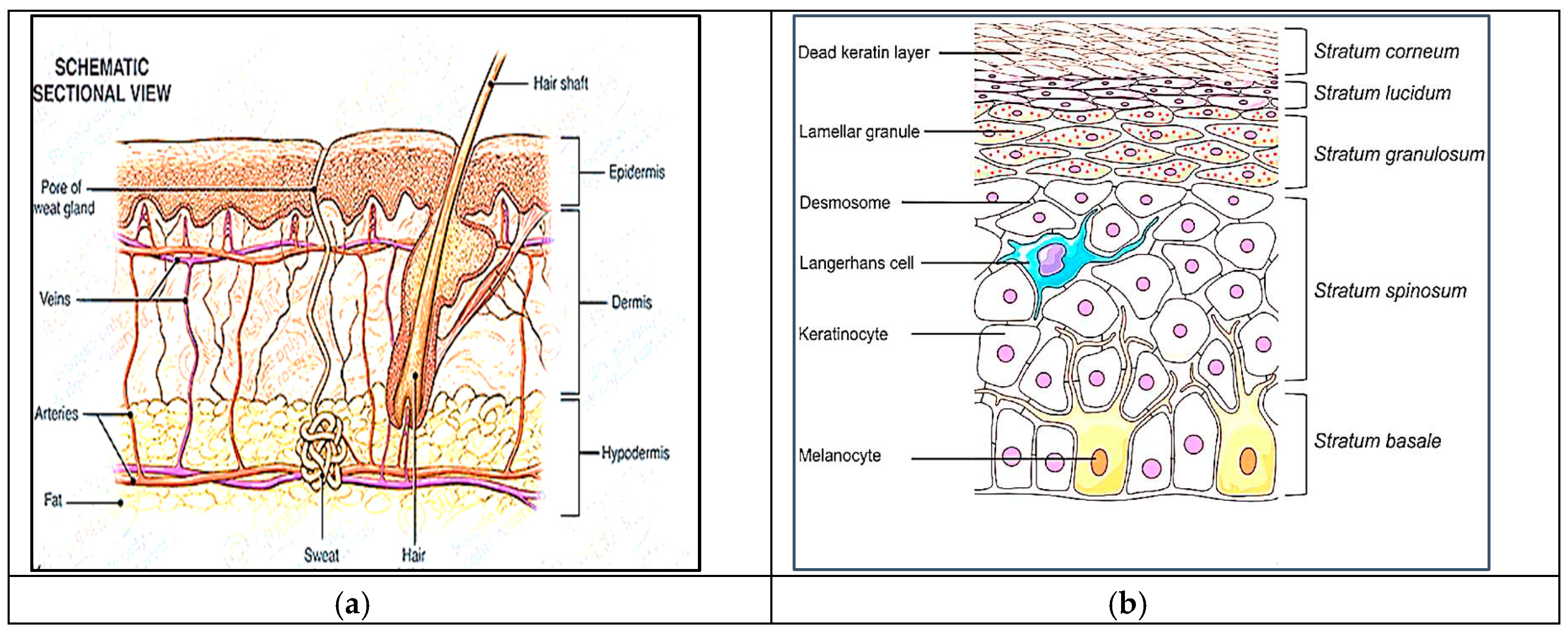

1.1. Skin Permeation as a Barrier

1.2. Factors Affecting Transdermal Permeability

1.2.1. Physico-Chemical Properties of Parent Molecule

- Solubility and Partition Coefficient

- pH Condition and Penetrant Concentration

1.2.2. Physico-Chemical Properties of Drug Delivery System

- Release characteristics and Composition of drug delivery system

1.2.3. Physiological and Pathological Conditions of Skin

- Lipid Film and Skin Hydration

- Effect of Vehicle

1.2.4. Biological Factors

- Skin Age and Skin Condition

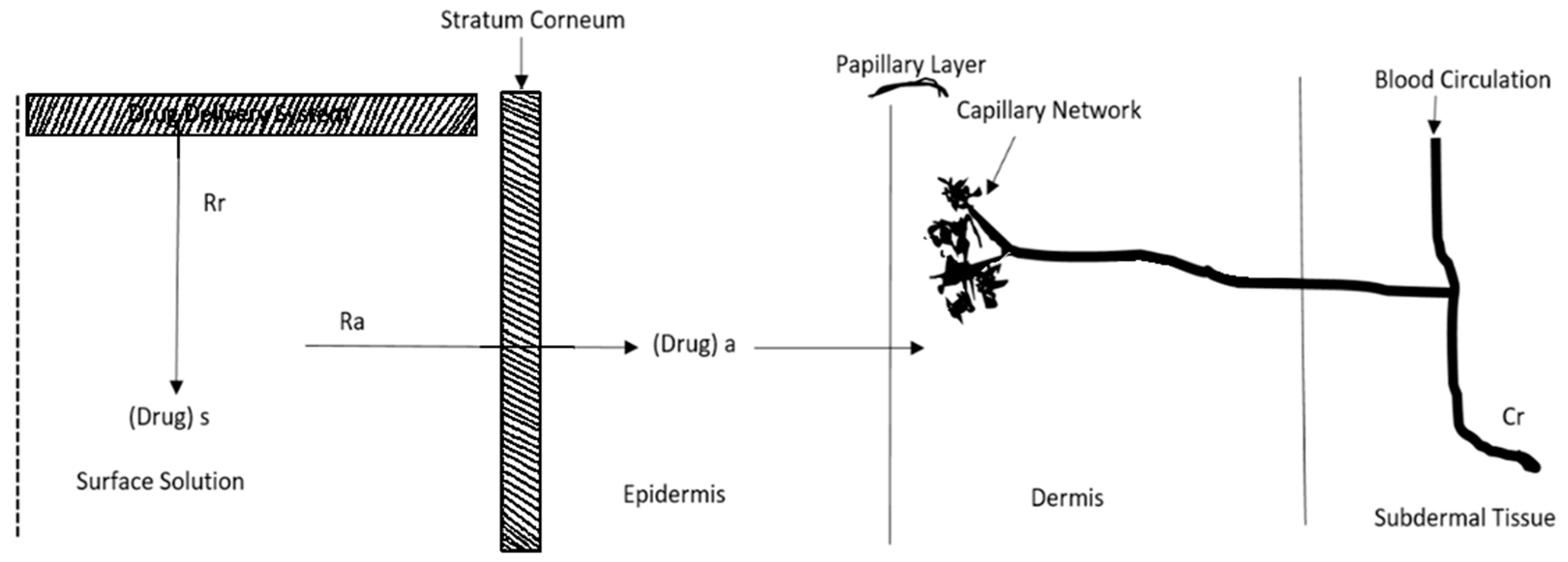

2. Kinetics of Transdermal Permeation

- (a)

- Absorption by the outermost layer of the skin, known as the stratum corneum

- (b)

- Drug permeation through the viable outer layer of the skin

- (c)

- Absorption of the drug by the network of small blood vessels in the upper layer of the dermis [32]

3. Basic Components and Classification of TDDS

3.1. Polymer Matrices

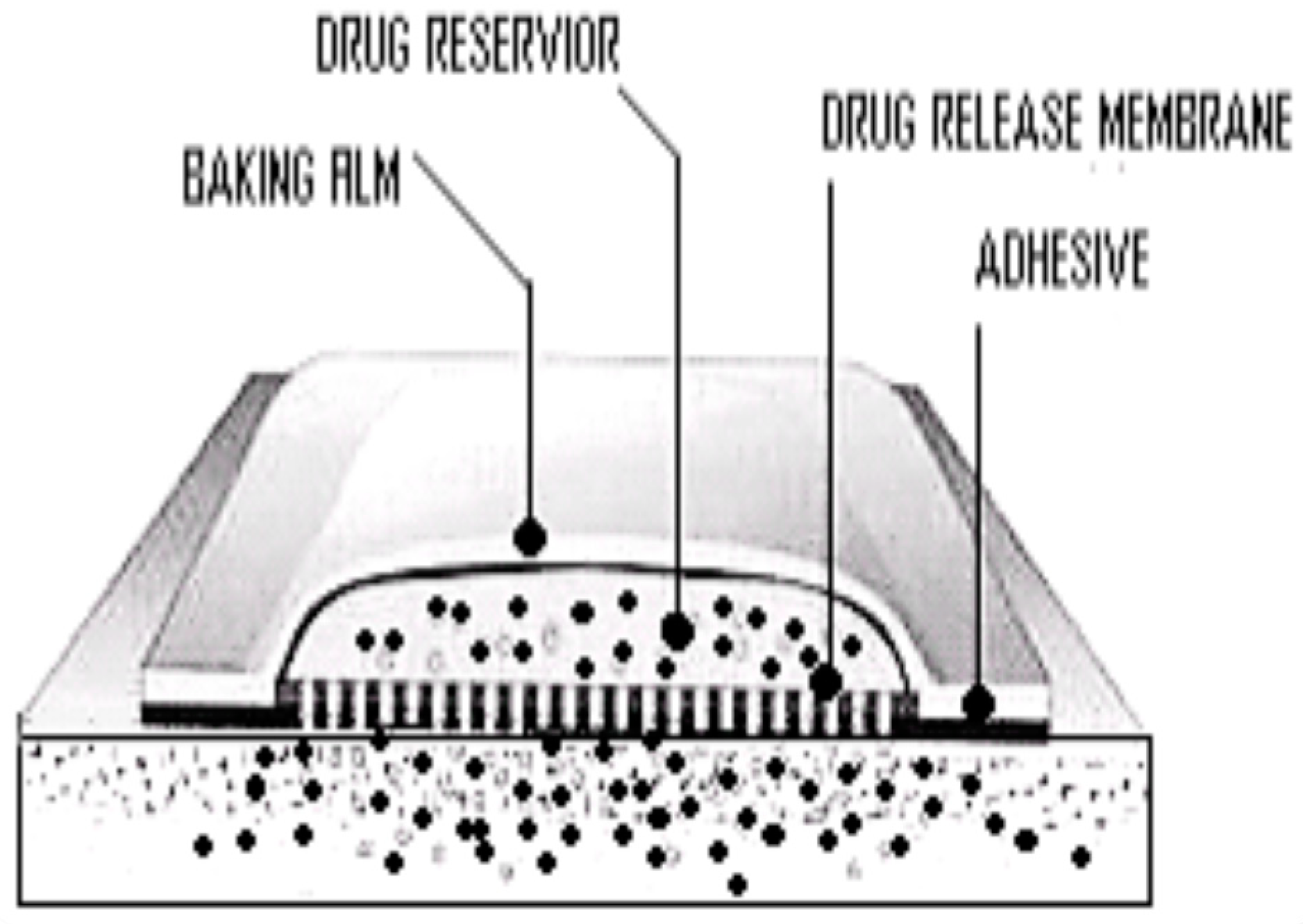

3.2. Drug Reservoir

3.3. Permeation Enhancers

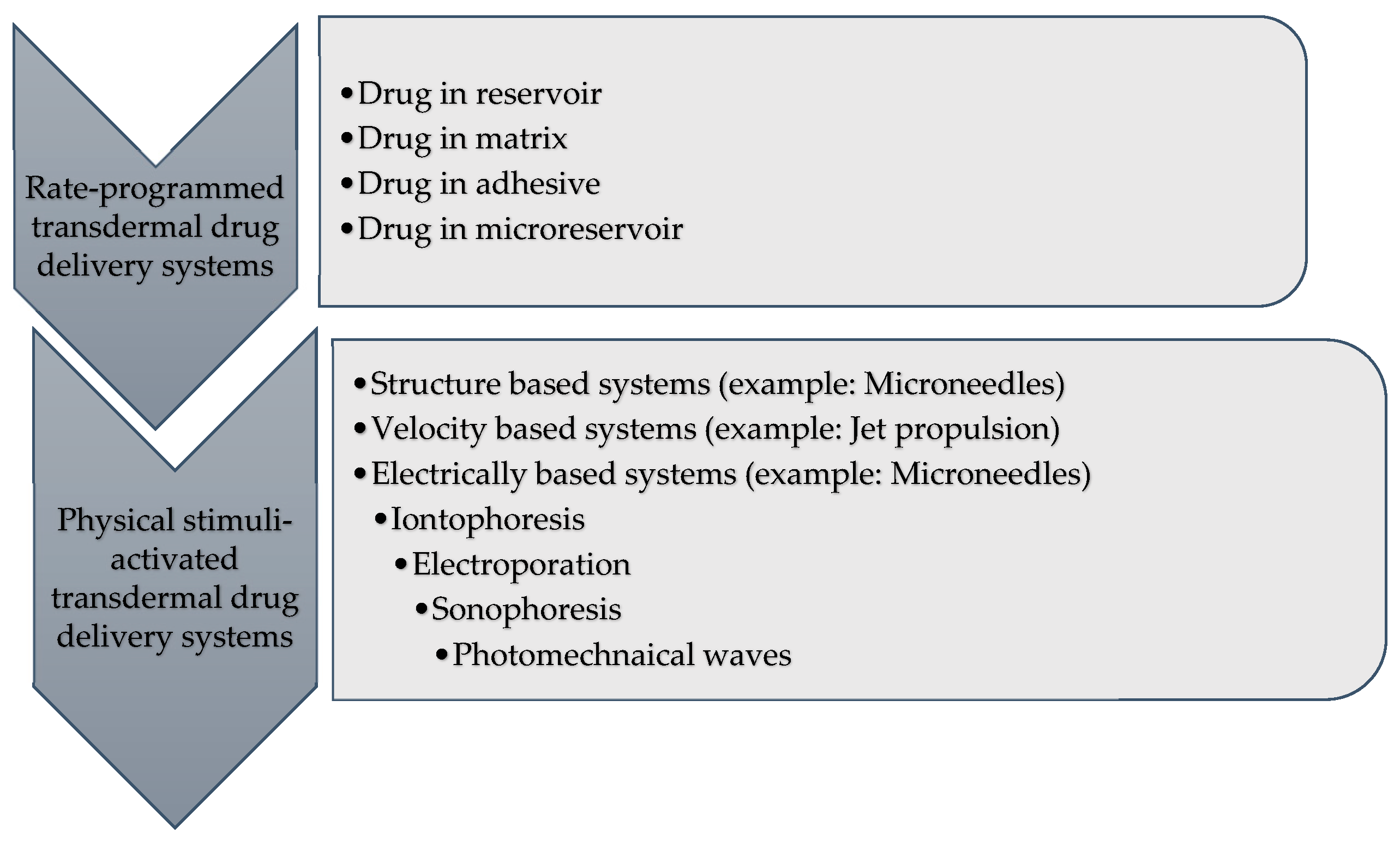

3.4. Classification of TDDS

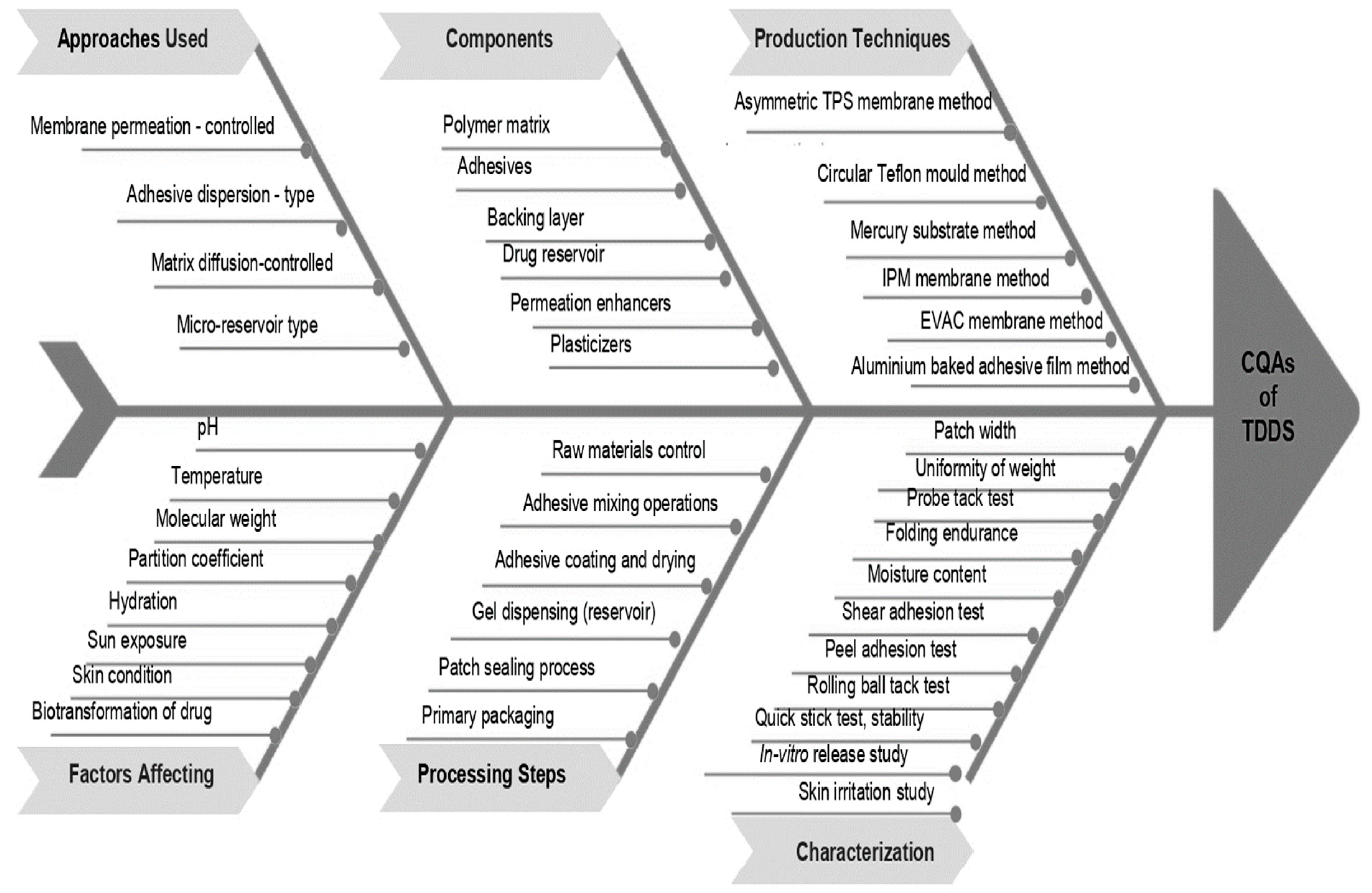

4. Quality by Design (QbD) Approach of TDDS

Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

5. Approaches Used in the Development of TDDS

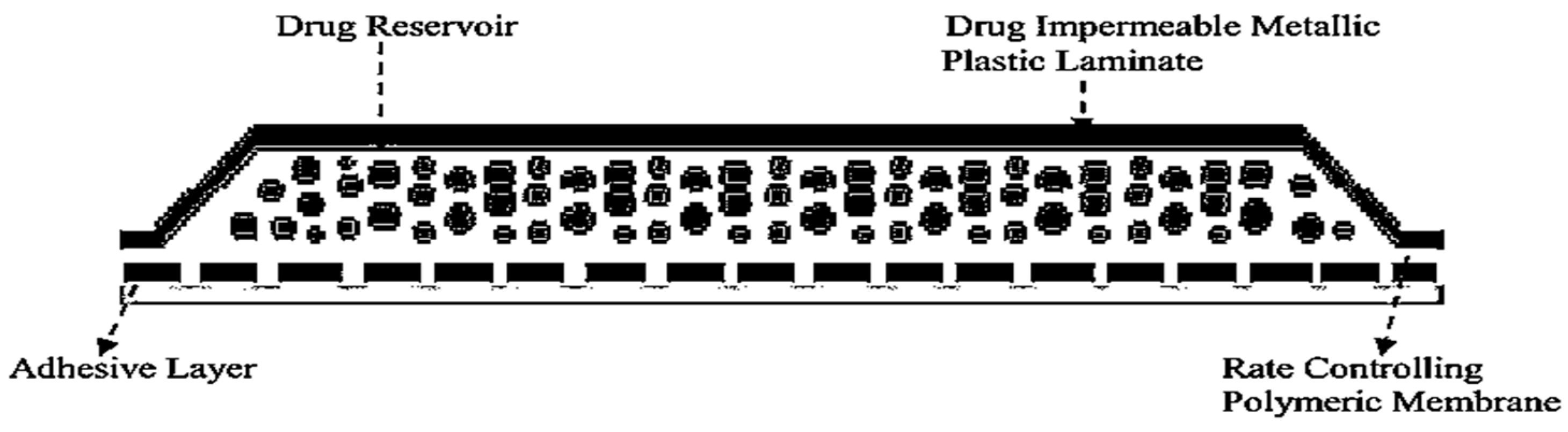

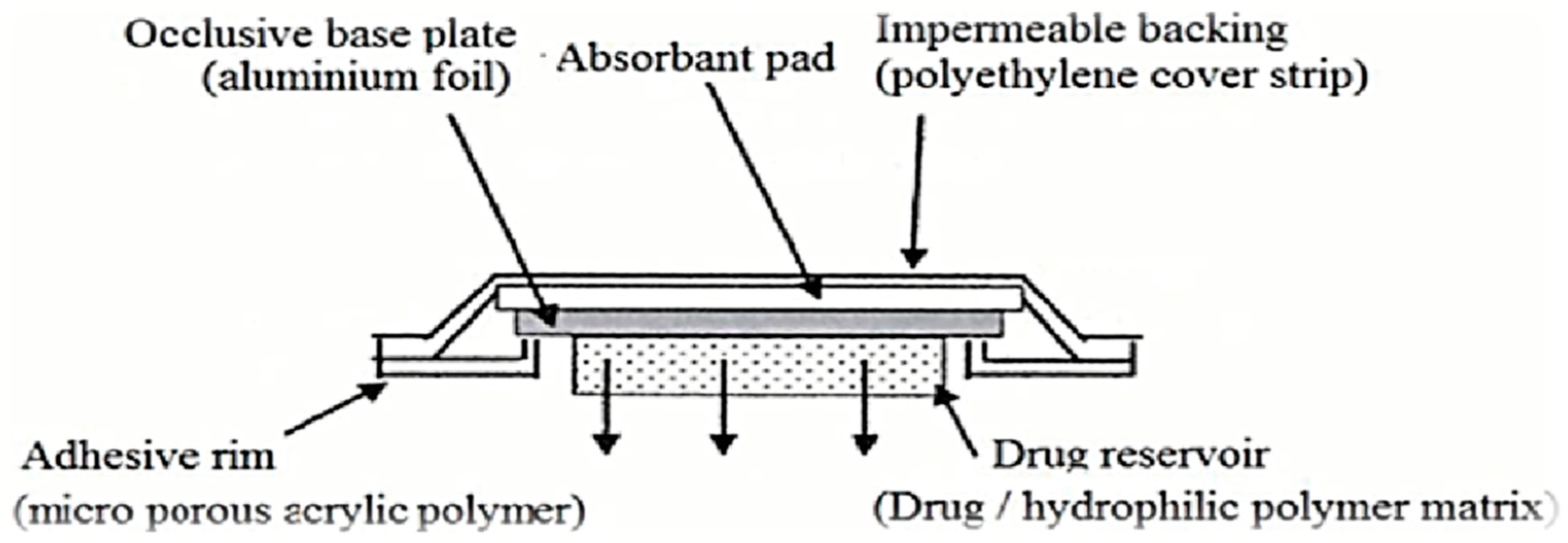

5.1. Membrane Permeation-Controlled Systems

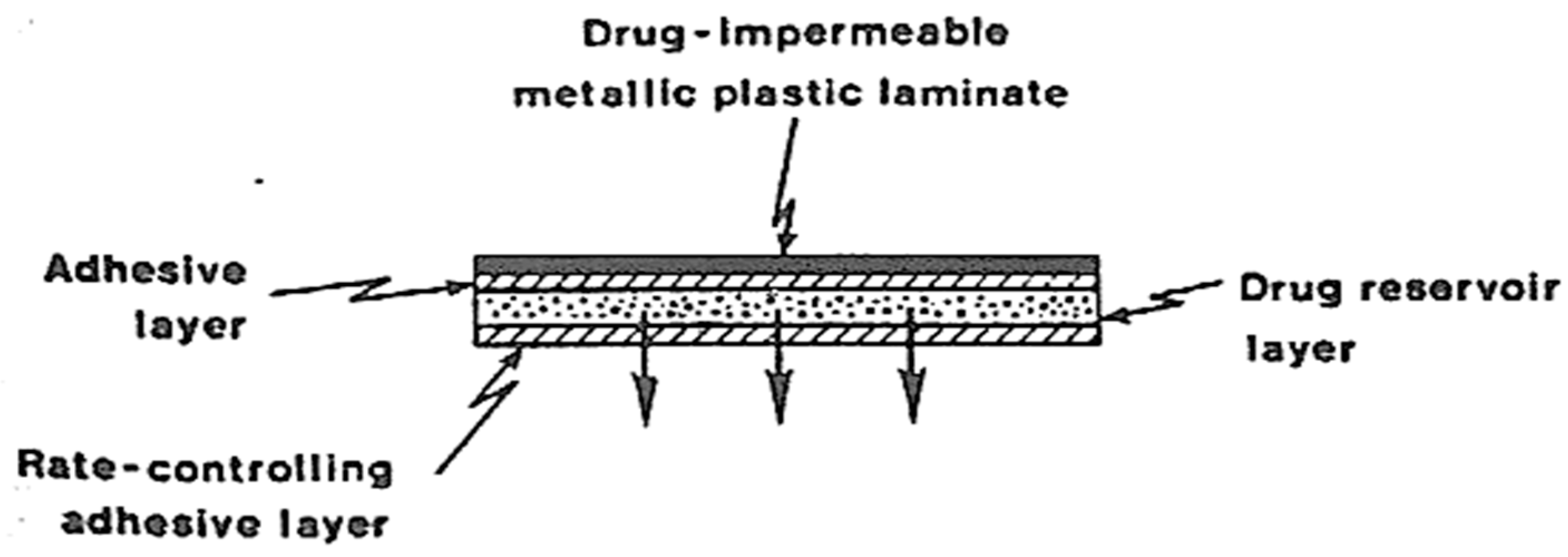

5.2. Adhesive Dispersion-Type Systems

5.3. Matrix Diffusion-Controlled Systems

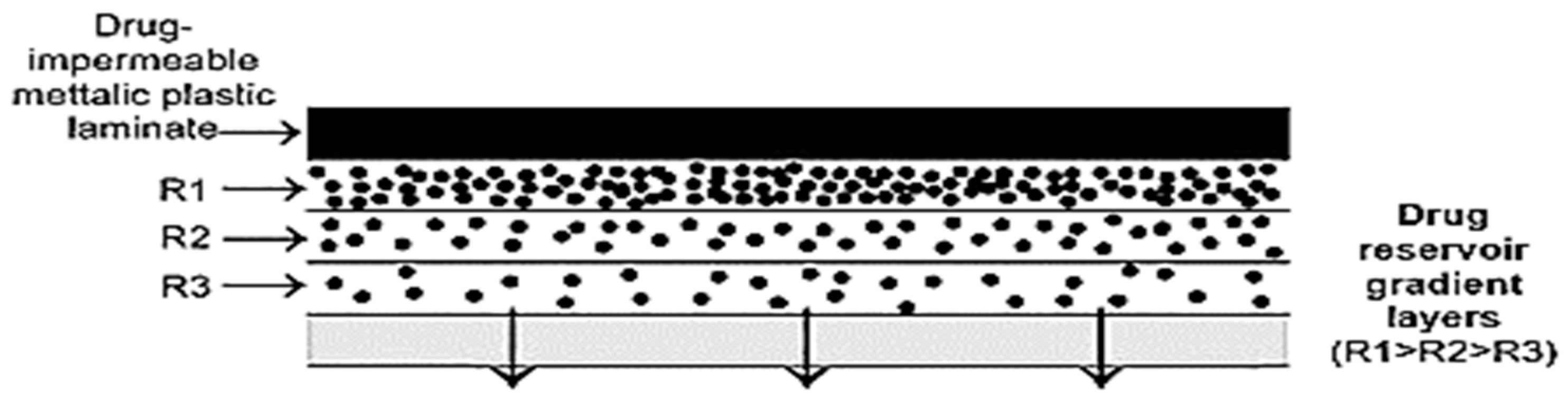

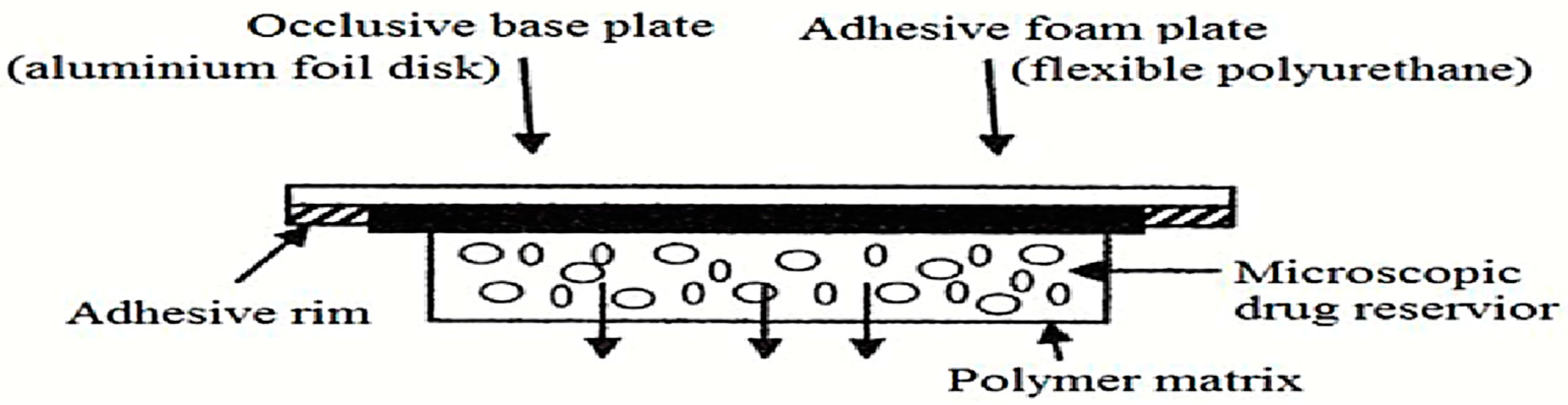

5.4. Microreservoir Type or Micro-Sealed DissolutionCcontrolled Systems

6. Production of TDDS

6.1. Asymmetric TPX Membrane Method

6.2. Circular-Teflon Mould Method

6.3. Mercury-Substrate Method

6.4. By Using the IPM Membrane Method

6.5. By Using the (Ethylene Vinyl Acetate Copolymer) EVAC Membrane Method

6.6. Aluminium-Backed Adhesive Film Method

6.7. By Using the Free-Film Method

7. Enhancement of Transdermal Drug Delivery

7.1. Active Drug Delivery

7.2. Passive Drug Delivery

| Active delivery | Methods | Advantages |

| Iontophoresis | Improves the delivery of polar molecules and high molecular weight compounds, easy to administer, continuous or pulsatile delivery of drugs | |

| Sonophoresis | Strict control of transdermal diffusion rates, greater patient approval, less risk of systemic absorption, non-sensitizing | |

| Electroporation | Highly effective, reproducible, rapid termination of drug delivery, not sensitizing | |

| Photomechanical waves | Improve the transfer of molecules across the plasma membrane without loss of viability, do not cause pain or discomfort | |

| Microneedle | Painless administration of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, faster healing at the injection site, no fear of needle, specific delivery of the drugs | |

| Thermal ablation | Avoid pain, bleeding and infection, better control and reproducibility, low cost and disposable device | |

| Passive delivery | Nanoemulsion | Long-term thermodynamic stability, excellent wettability, high solubilization capacity and physical stability |

| Polymeric nanoparticles | Targeted and controlled release behaviour, high mechanical strength, and both hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs can be loaded | |

| Vesicles | Sustained drug release behaviour, controls the absorption rate through a multilayered structure. |

8. Evaluation of TDDS

8.1. Physico-Chemical Evaluation–Adhesive Evaluation

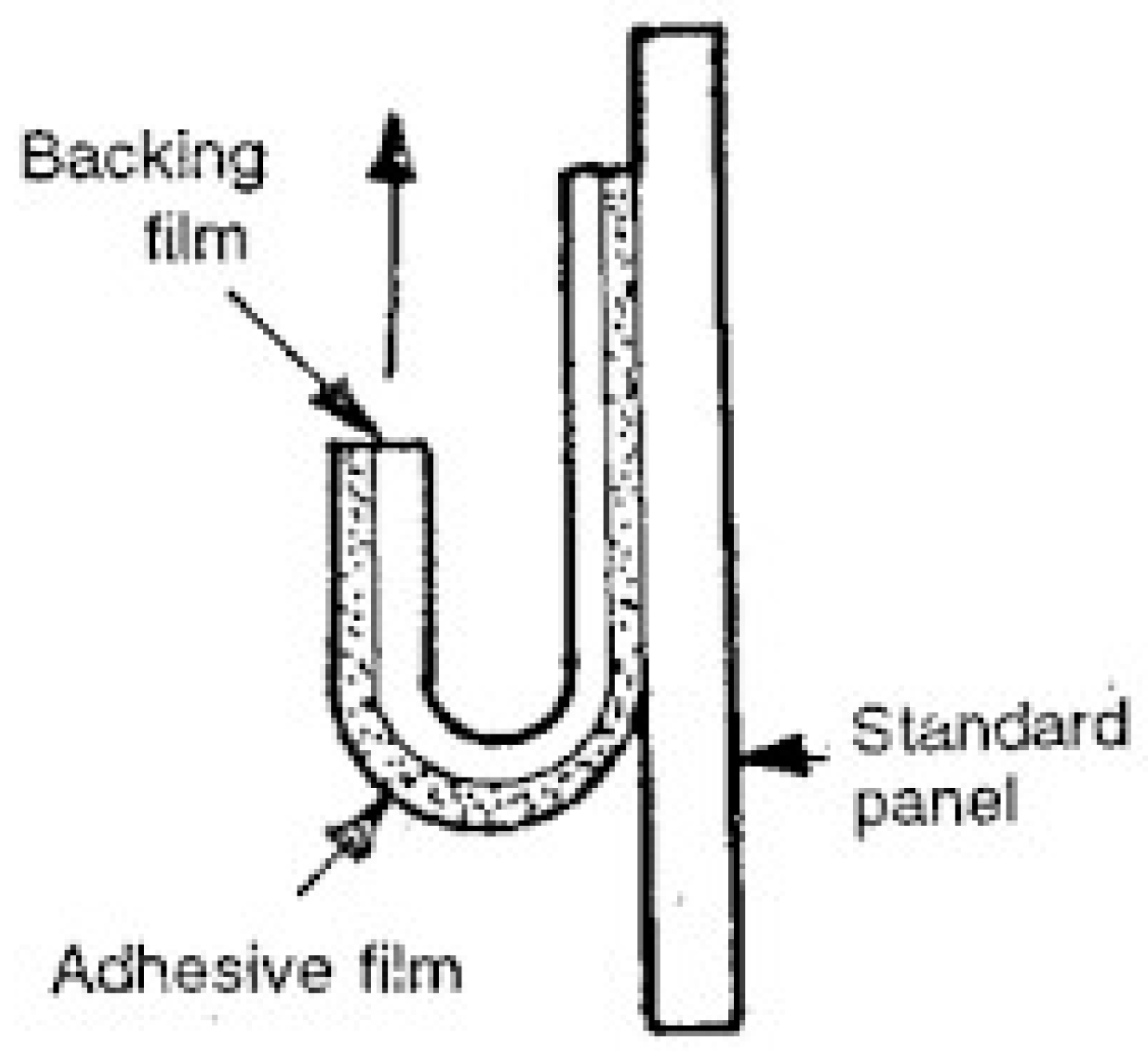

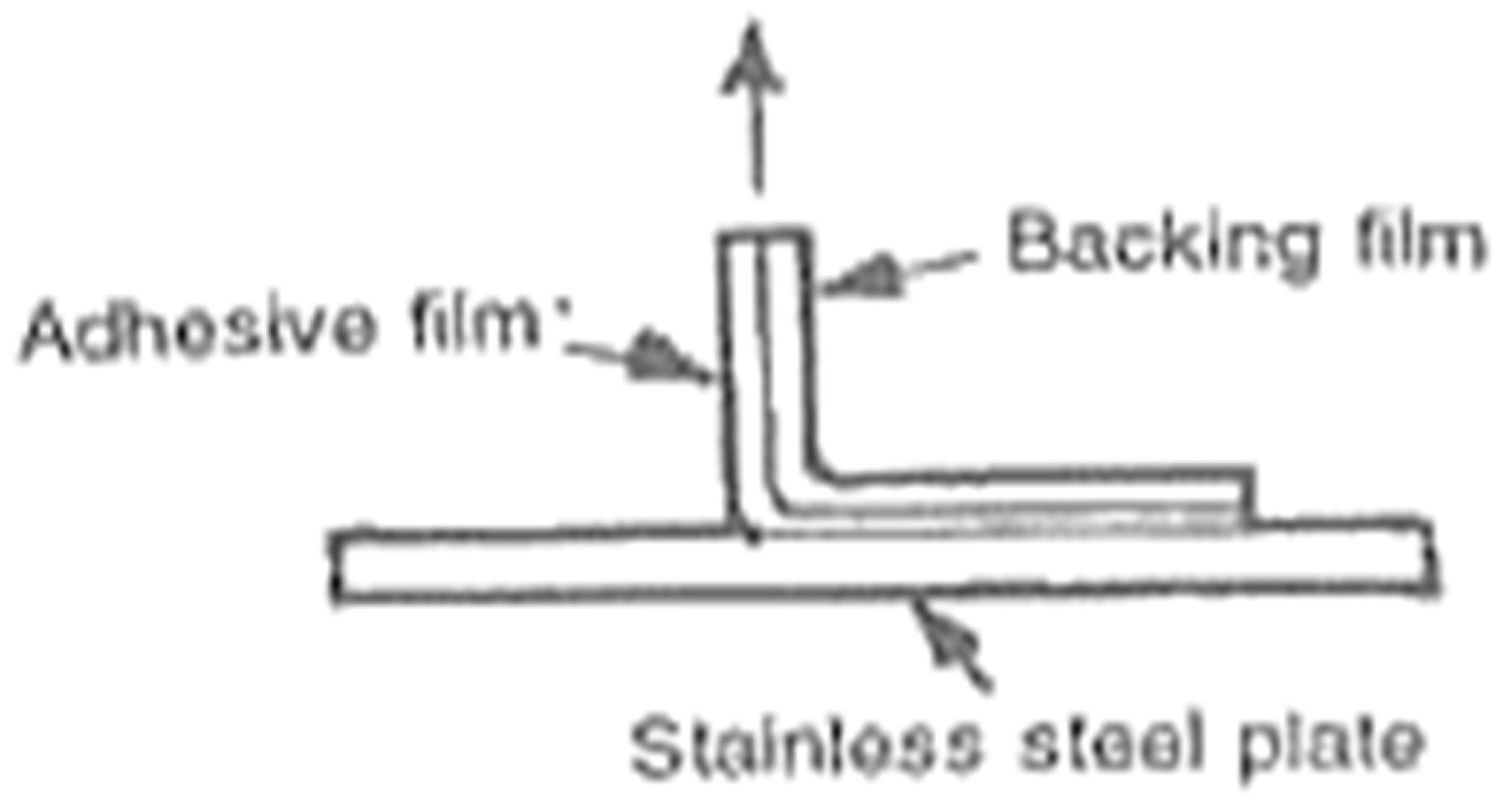

8.1.1. Peel Adhesion Properties [112]

8.1.2. Tack Properties [113]

- (a)

- Thumbtack Test [114]

- (b)

- Rolling Ball Tack Test [115]

- (c)

- Quick-Stick or Peel Tack Test [116]

- (d)

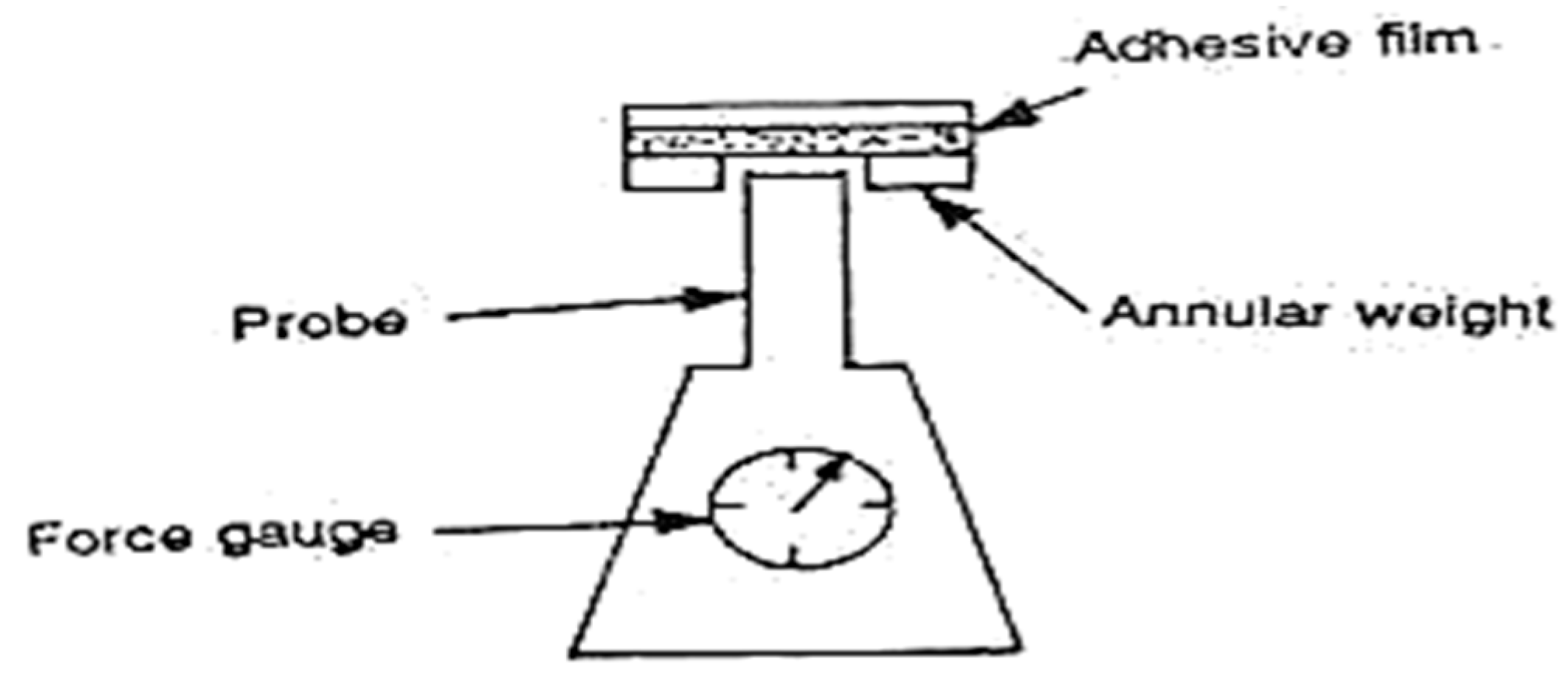

- Probe Tack Test [117]

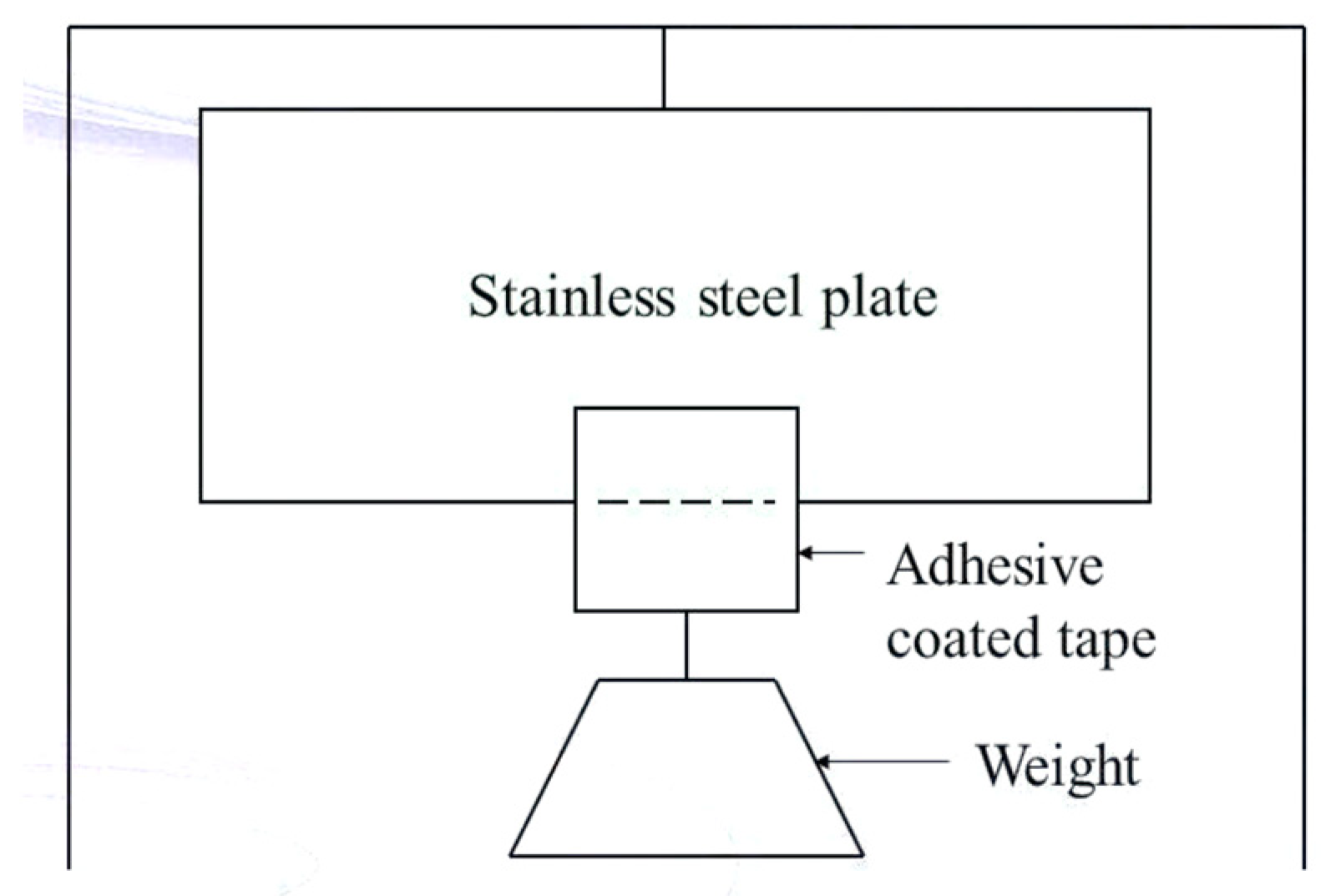

8.1.3. Shear Strength Properties [118]

8.2. Patch Width [119]

8.3. Folding Endurance [120]

8.4. Percentage of Moisture Content [121]

8.5. Moisture Uptake [122]

8.6. Content Uniformity Test [123]

8.7. Drug Content [124]

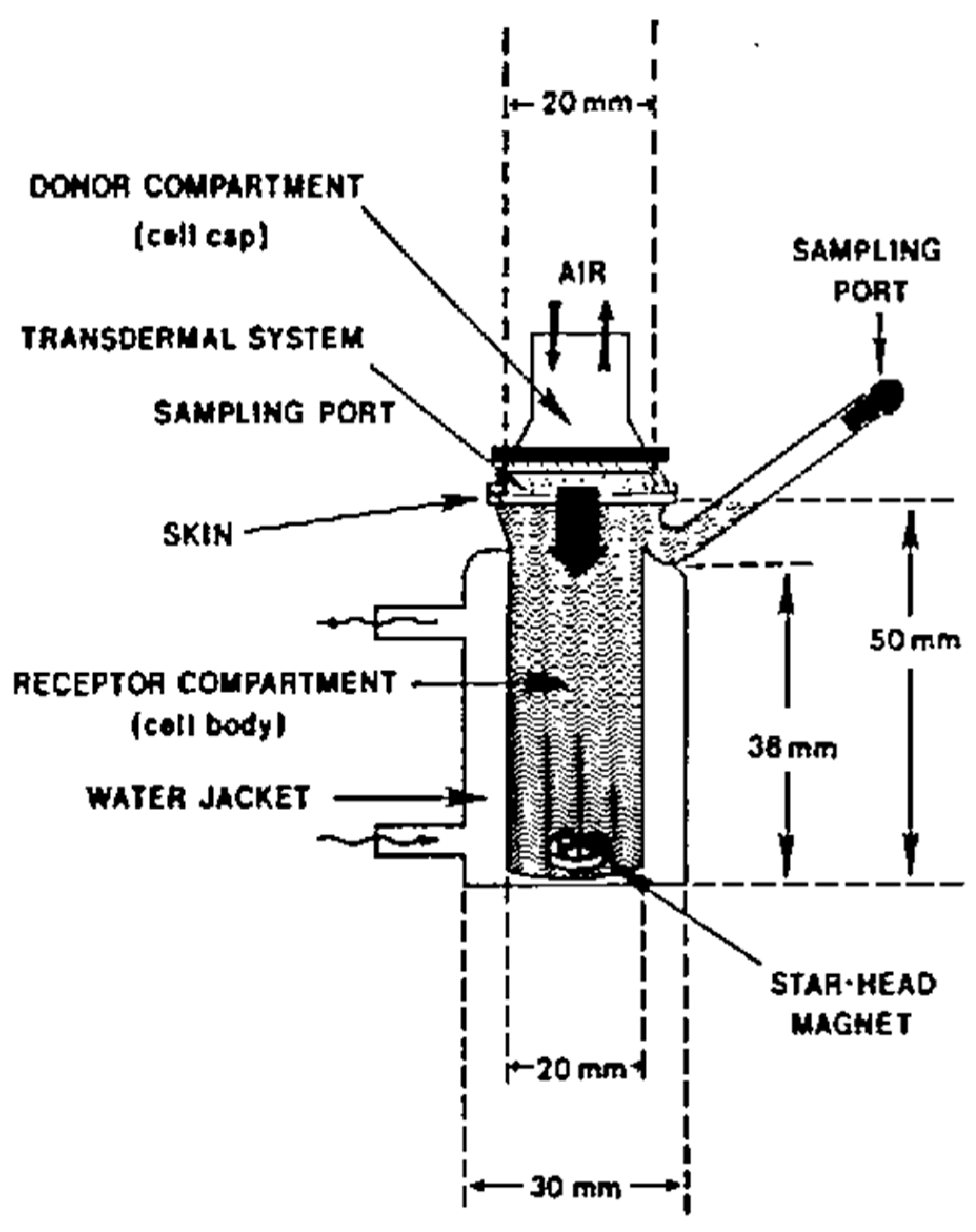

8.8. In-Vitro Drug release [125]

8.9. Skin Irritation Study [126]

8.10. Stability Study [127]

8.11. In-Vivo Evaluation

8.11.1. Animal Models [128]

8.11.2. Human Models [129]

8.12. Cutaneous toxilogical evaluation [130]

9. Regulatory Guidance

10. Potential Applications of Transdermal Products

| Drugs | Indications |

|---|---|

| Nicotine | Cessation of tobacco smoking |

| Fentanyl CII (Duragesic) | Moderate/severe pain |

| Buprenorphine CIII (Bu Trans) | Relief for severe pain |

| Oestrogen, Levonorgestrel, Estradiol | Treat menopausal syndromes, postmenopausal osteoporosis |

| Ortho Evra or Evra (norelgestromin, ethinyl estradiol) | Contraceptive |

| Nitroglycerin | Angina pectoris and relieves pain after surgery |

| Scopolamine | Motion sickness |

| Clonidine | Anti-hypertensive |

| MAOI selegiline | Anti-depressant |

| Methylphenidate | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |

| Asenapine | Antipsychotic agent |

| Vitamin B12 (Cyanocobalamin) | Supplement |

| Rivastigmine, Donepezil | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Asenapine | Bipolar disorder |

| Bisoprolol | Atrial fibrillation |

| Clonidine | Hypertension, Tourette syndrome, ADHD |

| Dextroamphetamine | ADHD |

| Granisetron | Anti-emetic |

| Lidocaine | Treatment of pain |

| Oxybutynin | Overactive bladder |

| Rotigotine | Parkinson’s disease |

| Testosterone | Hypogonadism in males |

| Selegiline | Depression |

11. Clinical Considerations of TDDS

- The extent of percutaneous absorption can differ depending on the location of the application. The intended primary application location is indicated in the package insert for each product. The patient should be informed about the significance of utilizing the prescribed location. After a period of one week, it is possible to reuse skin sites.

- The use of TDDS should be limited to skin that is clean, dry, and devoid of hair. Additionally, the skin should not be oily, irritable, inflamed, damaged, or callused. Increased skin moisture can enhance the rate of drug penetration beyond the targeted level. The presence of excess sebum on the skin can hinder the ability of the patch to stick to the intended area.

- Avoid applying skin lotion at the location of application. Lotions alter the moisture of the skin and have the potential to modify the partition coefficient between the medication and the skin.

- It is not advisable to cut TDDSs (to decrease the dose) as this compromises the integrity of the system.

- The unit should be removed from its protective packaging, taking caution to avoid any tearing or cutting. Remove the protective backing carefully to reveal the sticky layer, making sure not to touch the adhesive surface with your fingertips. To achieve consistent contact and adherence, it is necessary to firmly apply pressure to the skin location using the heel of the hand for approximately 10 seconds.

- The TDDS should be positioned in a location where it is not susceptible to friction from clothing or bodily motion. It is permissible to keep it on while showering, bathing, or swimming. If a TDDS becomes dislodged before the intended time, one can either try to reapply it or replace it with a new system.

- It is important to wear a TDDS for the entire duration specified in the product’s instructions. Subsequent to that time frame, it ought to be eliminated and substituted with a new system as directed.

- The patient must be advised to properly cleanse their hands before and after applying a TDDS. Using precautions and avoiding touching the eyes or mouth while handling the system is important.

- If the patient experiences sensitivity or intolerance to a TDDS, or if skin irritation occurs, the patient should seek reevaluation.

- When removing a used TDDS, it should be folded in half with the adhesive layer to prevent any possibility of reuse. The patch that has been used, and still contains traces of medication, should be placed inside the pouch of the replacement patch and disposed of in a way that is safe for children and pets.

12. Conclusion and Future Challenges

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chien, Y.W.; Liu, J.C. Transdermal drug delivery systems. J. Biomater. Appl. 1986, 1, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasagna, L.; Greenblatt, D.J. More than skin deep: Transdermal drug-delivery systems. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986, 314, 1638–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, B.; John, V.A. Pharmacokinetic characterisation of transdermal delivery systems. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1994, 26, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, D.; Bandaru, R.; Samal, S.K.; Naik, R.; Kumar, P.; Kesharwani, P.; Dandela, R. Chapter 9—Oral drug delivery of nano medicine. In Theory and Applications of Nonparenteral Nanomedicines; Kesharwani, P., Taurin, S., Greish, K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhu, L.; Yang, N.; Li, H.; Yang, Q. Recent advances of oral film as platform for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 604, 120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Arora, M.; Ravi Kumar, M.N.V. Oral Drug Delivery Technologies-A Decade of Developments. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2019, 370, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Zhang, Y.F.; Jiao, F.Y.; Guo, X.Y.; Gao, X.M. Efficacy of clonidine transdermal patch for treatment of Tourette’s syn drome in children. Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2009, 11, 537–539. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.M.; Wang, L.; Xue, H.Y.; Lu, W.L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, H.Y. In vitro and in vivo characterization of a newly developed clonidine transdermal patch for treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.P.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.J.; Hong, S.Q.; Li, S.Z.; Hu, Y. The Efficacy and Tolerability of the Clonidine Transdermal Patch in the Treatment for Children with Tic Disorders: A Prospective, Open, Single-Group, Self-Controlled Study. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.N.; Kalia, Y.N.; Horstmann, M.; Roberts, M.S. Transdermal patches: History, development and pharmacology. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 2179–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Langer, R. Transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G.; Alle, M.; Chakraborty, C.; Kim, J.C. Strategies for transdermal drug delivery against bone disorders: A preclinical and clinical update. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Choi, H.Y.; Lim, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Jeon, H.S.; Hong, D.; Kim, S.S.; Choi, Y.K.; Bae, K.S. Single dose pharmacokinetics ofthe novel transdermal donepezil patch in healthy volunteers. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.K.; Bae, K.S.; Hong, D.H.; Kim, S.S.; Choi, Y.K.; Lim, H.S. Pharmacokinetic evaluation by modeling and simulation analysis of a donepezil patch formulation in healthy male volunteers. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, W.; Chedraui, P.; Mendoza, J.; Ruilova, I. Gabapentin vs. low-dose transdermal estradiol for treating post-menopausal women with moderate to very severe hot flushes. Gynecol. Endocrinol 2010, 26, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C.; Caruso, M.G.; Berloco, P.; Buonsante, A.; Giannandrea, B.; Di Leo, A. alpha-Tocopherol and beta-carotene serum levels in post-menopausal women treated with transdermal estradiol and oral medroxyprogesterone acetate. Horm. Metab. Res. 1996, 28, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kruger, P.; Maibach, H.; Colditz, P.B.; Roberts, M.S. Using Skin for Drug Delivery and Diagnosis in the Critically Ill. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 77, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.C.; Barry, B.W. Penetration Enhancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 128–137. 19. Benson, H.A.; Watkinson, A.C. Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery: Principles and Practice; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012.

- Wokovich, A.M.; Shen, M.; Doub, W.H.; Machado, S.G.; Buhse, L.F. Evaluating elevated release liner adhesion of a transdermal drug delivery system (TDDS): A study of Daytrana methylphenidate transdermal system. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2011, 37, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.K.; Lan, T.H.; Wu, B.J. A double-blind randomized clinical trial of different doses of transdermal nicotine patch for smoking reduction and cessation in long-term hospitalized schizophrenic patients. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 263, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, N.; Singh, V.; Yusuf, M.; Khan, R.A. Non-invasive drug delivery technology: Development and current status of transdermal drug delivery devices, techniques and biomedical applications. Biomed. Tech. Eng. 2020, 65, 243–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, K.A. Dermatological and Transdermal Formulations; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, A.; Dwivedi, S.; Giri, T.K.; Saraf, S.; Saraf, S.; Tripathi, D.K. Approaches for Breaking the Barriers of Drug Permeation through Transdermal Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2012, 164, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perng, R.P.; Hsieh, W.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Lu, C.C.; Chiang, S.J. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation. J. Formos. Med. Assoc 1998, 97, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, J.D. Transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 344–345. 38. Dahlstrom, C.G.; Rasmussen, K.; Bagger, J.P.; Henningsen, P.; Haghfelt, T. Transdermal nitroglycerin (Transiderm-Nitro) in the treatment of unstable angina pectoris. Dan. Med. Bull. 1986, 33, 265–267.

- Archer, D.F.; Furst, K.; Tipping, D.; Dain, M.P.; Vandepol, C. A randomized comparison of continuous combined transdermal delivery of estradiol-norethindrone acetate and estradiol alone for menopause. CombiPatch Study Group. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 94, 498–503. [Google Scholar]

- Danso, M.O.; Berkers, T.; Mieremet, A.; Hausil, F.; Bouwstra, J.A. An ex vivo human skin model for studying skin barrier repair. Exp. Dermatol, 2014; 24, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, M.O.; van Drongelen, V.; Mulder, A.; Gooris, G.; van Smeden, J.; El Ghalbzouri, A.; Bouwstra, J.A. Exploring the potentials of nurture: 2nd and 3rd generation explant human skin equivalents. J. Dermatol. Sci, 2015; 77, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.N.; Jeong, E.; Prausnitz, M.R. Transdermal delivery of molecules is limited by full epidermis, not just stratum corneum. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepps, O.G.; Dancik, Y.; Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Modeling the human skin barrier— Towards a better understanding of dermal absorption. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.W.; Shin, S.C. Enhanced transdermal delivery of atenolol from the ethylene-vinyl acetate matrix. Int. J. Pharm. 2004, 287, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dull, P. Transdermal oxybutynin (oxytrol) for urinary incontinence. Am. Fam. Physician 2004, 70, 2351–2352. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, C. Transdermally-delivered oxybutynin (Oxytrol(R) for overactive bladder. Issues Emerg Health Technol, 2001; 24, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, A.; Farlow, M.; Lefevre, G. Pharmacokinetics of a novel transdermal rivastigmine patch for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefevre, G.; Pommier, F.; Sedek, G.; Allison, M.; Huang, H.L.; Kiese, B.; Ho, Y.Y.; Appel-Dingemanse, S. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the novel rivastigmine transdermal patch versus rivastigmine oral solution in healthy elderly subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 48, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, J.-H.; Prausnitz, M.R. Dissolving microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2113–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnin, B.C.; Morgan, T.M. Transdermal penetration enhancers: Applications, limitations, and potential. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 955–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.N.; Kalia, Y.N.; Horstmann, M.; Roberts, M.S. Transdermal patches: History, development and pharmacology. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 2179–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Langer, R. Transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Alle, M.; Chakraborty, C.; Kim, J.C. Strategies for transdermal drug delivery against bone disorders: A preclinical and clinical update. J. Control. Release 2021, 336, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, R.W.; Wiemann, S.; Keck, C.M. Improved dermal and transdermal delivery of curcumin with smartfilms and nanocrystals. Molecules 2021, 26, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermode, M. Unsafe Injections in Low-Income Country Health Settings: Need for Injection Safety Promotion to Prevent the Spread of Blood-Borne Viruses. Health. Promot. Int. 2004, 19, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.R.; Morrow, D.I.; Woolfson, A.D. Microneedle-Mediated Transdermal and Intradermal Drug Delivery; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kretsos, K.; Kasting, G.B. A Geometrical Model of Dermal Capillary Clearance. Math. Biosci. 2007, 208, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.R.; Garland, M.J.; Migalska, K.; Majithiya, R.; McCrudden, C.M.; Kole, P.L.; Mahmood, T.M.T.; McCarthy, H.O.; Woolfson, A.D. Hydrogel-Forming Microneedle Arrays for Enhanced Transdermal Drug Delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4879–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Mitragotri, S. Micro-Scale Devices for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhawan, J.; Parmar, P.K.; Bansal, A.K. Nanocrystals for improved topical delivery of medium soluble drug: A case study of acyclovir. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 65, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.A.; Rashid, F.; Khan, M.K.; Alqahtani, S.S.; Sultan, M.H.; Almoshari, Y. Fabrication of capsaicin loaded nanocrystals: Physical characterizations and in vivo evaluation. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekko, I.A.; Permana, A.D.; Vora, L.; Hatahet, T.; McCarthy, H.O.; Donnelly, R.F. Localised and sustained intradermal delivery of methotrexate using nanocrystal-loaded microneedle arrays: Potential for enhanced treatment of psoriasis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 152, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, P.; Hansen, D.; Matarazzo, D.; Petterson, L.; Swisher, C.; Trappolini, A. Transderm Scop for prevention of motion sickness. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 311, 468–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, S.K.; Strasinger, C.; Kelchen, M.; Carr, J.; Ye, W.; Wokovich, A.; Ghosh, P.; Rajagopal, S.; Ueda, K.; Fisher, J.; et al. Determination of Rate and Extent of Scopolamine Release from Transderm Scop(R) Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems in Healthy Human Adults. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhasin, S.; Storer, T.W.; Asbel-Sethi, N.; Kilbourne, A.; Hays, R.; Sinha-Hikim, I.; Shen, R.; Arver, S.; Beall, G. Effects of testosterone replacement with a nongenital, transdermal system, Androderm, in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men with low testosterone levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkilani, A.Z.; McCrudden, M.T.; Donnelly, R.F. Transdermal Drug Delivery: Innovative Pharmaceutical Developments Based on Disruption of the Barrier Properties of the stratum corneum. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 438–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, S.; Whiteman, A.; Brandner, B. Transdermal drug delivery in pain management. Contin. Educ. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain 2011, 11, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, I.A.; Ghate, V.M.; Dsouza, L.; Lewis, S.A. Lipid vesicles: A versatile drug delivery platform for dermal and transdermal applications. Colloids Surf. B 2020, 195, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, R.R.; Torchilin, V.P. Challenges in development of targeted liposomal therapeutics. AAPS J. 2012, 14, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, J.C.; Freeling, J.P.; Wang, Z.; Ho, R.J.Y. Emerging research and clinical development trends of liposome and lipid nanoparticle drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 103, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillet, A.; Evrard, B.; Piel, G. Liposomes and parameters affecting their skin penetration behaviour. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2011, 21, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, L.S.; Skee, D.M.; Natarajan, J.; Wong, F.A.; Anderson, G.D. Pharmacokinetics of a contraceptive patch (Evra/Ortho Evra) containing norelgestromin and ethinyloestradiol at four application sites. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 53, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Anwer, M.K.; Shams, M.S.; Ali, A.; Khar, R.K.; Shakeel, F.; Taha, E.I. Proniosomal transdermal therapeutic system of losartan potassium: Development and pharmacokinetic evaluation. J. Drug Target. 2009, 17, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, N.; Marsh, A. A short history of nitroglycerine and nitric oxide in pharmacology and physiology. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2000, 27, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannos, S. Skin Microporation: Strategies to Enhance and Expand Transdermal Drug Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2014, 24, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.B.; Traynor, M.J.; Martin, G.P.; Akomeah, F.K. Transdermal drug delivery systems: Skin perturbation devices. In Drug Delivery Systems; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C.; Costela, A.; García-Moreno, I.; Llanes, F.; Teijon, J.M.; Blanco, D. Laser Treatments on Skin Enhancing and Controlling Transdermal Delivery of 5-fluorouracil. Lasers Surg. Med. 2008, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.S.; McCullough, J.L.; Glenn, T.C.; Wright, W.H.; Liaw, L.L.; Jacques, S.L. Mid-Infrared Laser Ablation of Stratum Corneum Enhances in Vitro Percutaneous Transport of Drugs. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1991, 97, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, M. Nitric oxide discovery Nobel Prize winners. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 1747–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, P.K.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Ruggirello, D.; Tomlinson, J.; Babcock-Atkinson, E.; Ray, M.; Golub, A.; Cohen, A. Relative bioavailability of a new transdermal nitroglycerin delivery system. J. Pharm. Sci. 1986, 75, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour, J.A.; Heel, R.C. Transdermal estradiol. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of menopausal complaints. Drugs 1990, 40, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, Y.; Borg, M.L.; Sibille, M.; Thebault, J.; Renoux, A.; Douin, M.J.; Djebbar, F.; Dain, M.P. Bioavailability Study of Menorest(R), a New Estrogen Transdermal Delivery System, Compared with a Transdermal Reservoir System. Clin. Drug Investig. 1995, 10, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiso, T.; Hata, T.; Iwaki, M.; TANINO, T. Transdermal absorption of bupranolol in rabbit skin in vitro and in vivo. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 24, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, L.; Du Preez, J.; Gerber, M.; Du Plessis, J.; Viljoen, J. Essential fatty acids as transdermal penetration enhancers. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.K.; Jasti, B.R. Theory and Practice of Contemporary Pharmaceutics; CRC press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, Y.B.; Prausnitz, M.R. The Rule of Five for Non-Oral Routes of Drug Delivery: Ophthalmic, Inhalation and Transdermal. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.N.; Jeong, E.; Prausnitz, M.R. Transdermal delivery of molecules is limited by full epidermis, not just stratum corneum. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepps, O.G.; Dancik, Y.; Anissimov, Y.G.; Roberts, M.S. Modeling the human skin barrier—Towards a better understanding of dermal absorption. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaten, G.E.; Palac, Z.; Engesland, A.; Filipović-Grčić, J.; Vanić, Ž.; Škalko-Basnet, N. In vitro skin models as a tool in optimization of drug formulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 75, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M.; Diab, R.; Elaissari, A.; Fessi, H. Lipid nanocarriers as skin drug delivery systems: Properties, mechanisms of skin interactions and medical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Qindeel, M.; Ahmed, N.; Khan, A.U.; Khan, S.; Rehman, A.U. Development of novel pH-sensitive nanoparticle-based transdermal patch for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 603–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.K.; Mishra, N.; Yadav, K.S.; Yadav, N.P. Nanoemulsion as pharmaceutical carrier for dermal and transdermal drug delivery: Formulation development, stability issues, basic considerations and applications. J. Control. Release 2018, 270, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Macri, L.K.; Kaplan, H.M.; Kohn, J. Nanoparticles and nanofibers for topical drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, A.; Shen, L.; Kelly, S.; Sahota, R.; Brezovic, C.; Bixler, C.; Powell, J. Steady-state bioavailability of estradiol from two matrix transdermal delivery systems, Alora and Climara. Menopause 1998, 5, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenbaum, H.; Birkhauser, M.; De Nooyer, C.; Lambotte, R.; Pornel, B.; Schneider, H.; Studd, J. Comparison of two estradiol transdermal systems (Oesclim 50 and Estraderm TTS 50). I. Tolerability, adhesion and efficacy. Maturitas 1996, 25, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngkin, E.Q. Estrogen replacement therapy and the estraderm transdermal system. Nurse Pract. 1990, 15, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wokovich, A.M.; Prodduturi, S.; Doub, W.H.; Hussain, A.S.; Buhse, L.F. Transdermal drug delivery system (TDDS) adhesion as a critical safety, efficacy and quality attribute. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2006, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, B. Novel Mechanisms and Devices to Enable Successful Transdermal Drug Delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 14, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Park, H.; Seo, J.; Lee, S. Sonophoresis in Transdermal Drug Deliverys. Ultrasonics 2014, 54, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.; Kalia, Y.N.; Guy, R.H. Transdermal Drug Delivery: Overcoming the skin’s Barrier Function. Pharm. Sci. Technol. Today 2000, 3, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stott, P.W.; Williams, A.C.; Barry, B.W. Mechanistic study into the enhanced transdermal permeation of a model β-blocker, propranolol, by fatty acids: A melting point depression effect. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 219, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimentová, J.; Kosák, P.; Vávrová, K.; Holas, T.; Hrabálek, A. Influence of terminal branching on the transdermal permeationenhancing activity in fatty alcohols and acids. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 7681–7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty, J.P. Menorest: Technical development and pharmacokinetic profile. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1996, 64, S29–S33. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, J.E. Rotigotine Transdermal Patch: A Review in Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, D.H.; Buff, L.A.; Katz, R.J. Sustained antianginal efficacy of transdermal nitroglycerin patches using an overnight 10-hour nitrate-free interval. Am. J. Cardiol. 1988, 61, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartan, C.M. Buprenorphine Transdermal Patch: An Overview for Use in Chronic Pain. US Pharm 2014, 10, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Kanikkannan, N.; Singh, M. Skin permeation enhancement effect and skin irritation of saturated fatty alcohols. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 248, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maibach, H.I.; Feldmann, R.J. The effect of DMSO on percutaneous penetration of hydrocortisone and testosterone in man. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1967, 141, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadgraft, J.; Lane, M.E. Transdermal delivery of testosterone. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 92, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, J.; Poduri, R.; Panchagnula, R. Transdermal delivery of naloxone: Ex vivo permeation studies. Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 179, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Guan, Y.; Tian, Q.; Shi, X.; Fang, L. Transdermal enhancement strategy of ketoprofen and teriflunomide: The effect of enhanced drug-drug intermolecular interaction by permeation enhancer on drug release of compound transdermal patch. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 572, 118800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, V.L.; Wirostko, B.; Korenfeld, M.; From, S.; Raizman, M. Ophthalmic drug delivery using iontophoresis: Recent clinical applications. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. 2020, 36, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoellhammer, C.M.; Blankschtein, D.; Langer, R. Skin permeabilization for transdermal drug delivery: Recent advances and future prospects. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorec, B.; Préat, V.; Miklavčič, D.; Pavšelj, N. Active Enhancement Methods for Intra-and Transdermal Drug Delivery: A Review. Zdravniški Vestnik 2013, 82, 339–356. (In Slovenian) [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, K.S.; Milewski, M.; Swadley, C.L.; Brogden, N.K.; Ghosh, P.; Stinchcomb, A.L. Challenges and Opportunities in dermal/transdermal Delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2010, 1, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, G.; Roberts, M.S.; Grice, J.; Anissimov, Y.G.; Moghimi, H.R.; Benson, H.A. Iontophoretic skin permeation of peptides: An investigation into the influence of molecular properties, iontophoretic conditions and formulation parameters. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2014, 4, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, T.M. Selected medicines used in iontophoresis. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aqil, M.; Kamran, M.; Ahad, A.; Imam, S.S. Development of clove oil based nanoemulsion of olmesartan for transdermal delivery: Box–Behnken design optimization and pharmacokinetic evaluation. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 214, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Singh, A.; Harikumar, S. Development and optimization of nanoemulsion based gel for enhanced transdermal delivery of nitrendipine using box-behnken statistical design. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2020, 46, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, F.; Ramadan, W. Transdermal delivery of anticancer drug caffeine from water-in-oil nanoemulsions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 75, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marucci, G.; Buccioni, M.; Ben, D.D.; Lambertucci, C.; Volpini, R.; Amenta, F. Efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2021, 190, 108352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.L.; Friedhoff, L.T. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of donepezil HCl following single oral doses. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 46 (Suppl. 1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickel, U.; Thomsen, T.; Weber, W.; Fischer, J.P.; Bachus, R.; Nitz, M.; Kewitz, H. Pharmacokinetics of galanthamine in humans and corresponding cholinesterase inhibition. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1991, 50, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farlow, M.R. Clinical pharmacokinetics of galantamine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003, 42, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitragotri, S. Devices for Overcoming Biological Barriers: The use of physical forces to disrupt the barriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Gadiraju, P.; Park, J.; Allen, M.G.; Prausnitz, M.R. Microsecond Thermal Ablation of Skin for Transdermal Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2011, 154, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azagury, A.; Khoury, L.; Enden, G.; Kost, J. Ultrasound Mediated Transdermal Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 72, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameen, D.; Michniak-Kohn, B. Development and in vitro evaluation of pressure sensitive adhesive patch for the transdermal delivery of galantamine: Effect of penetration enhancers and crystallization inhibition. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 139, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Uddin, S.; Chowdhury, M.R.; Wakabayashi, R.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Goto, M. Insulin Transdermal Delivery System for Diabetes Treatment Using a Biocompatible Ionic Liquid-Based Microemulsion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 42461–42472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhote, V.; Bhatnagar, P.; Mishra, P.K.; Mahajan, S.C.; Mishra, D.K. Iontophoresis: A Potential Emergence of a Transdermal Drug Delivery System. Sci. Pharm. 2012, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, L.R.; Harada, L.K.; Silva, E.C.; Campos, W.F.; Moreli, F.C.; Shimamoto, G.; Pereira, J.F.B.; Oliveira, J.M., Jr.; Tubino, M.; Vila, M.; et al. Non-invasive Transdermal Delivery of Human Insulin Using Ionic Liquids: In vitro Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Choi, D.; Hong, J. Insulin particles as building blocks for controlled insulin release multilayer nano-films. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 54, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, V.B.V.; Yoshida, C.M.P.; Pereira, S.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Franco, T.T. Electrostatic Self-Assembled Chitosan-Pectin Nano- and Microparticles for Insulin Delivery. Molecules 2017, 22, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, E.E.L.; Ibsen, K.N.; Mitragotri, S. Transdermal insulin delivery using choline-based ionic liquids (CAGE). J. Control. Release 2018, 286, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, E.; Kaykın, M.; ¸Sahin Bektay, H.; Güngör, S. Recent Advances on Topical Application of Ceramides to Restore Barrier Function of Skin. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariya, S.H.; Gohel, M.C.; Mehta, T.A.; Sharma, O.P. Microneedles: An Emerging Transdermal Drug Delivery System. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, H.S.; Prausnitz, M.R. Coated Microneedles for Transdermal Delivery. J. Control. Release 2007, 117, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, X.; Wei, L.; Wu, F.; Wu, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, W. Dissolving and biodegradable microneedle technologies for transdermal sustained delivery of drug and vaccine. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2013, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-C.; Huang, S.-F.; Lai, K.-Y.; Ling, M.-H. Fully embeddable chitosan microneedles as a sustained release depot for intradermal vaccination. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3077–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, J.; Smeets, J.; Drenth, H.J.; Gill, D. Pharmacokinetics of a granisetron transdermal system for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2009, 15, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.N.; Adler, M.T.; Ouillette, H.; Berens, P.; Smith, J.A. Observational Case Series Evaluation of the Granisetron Transdermal Patch System (Sancuso) for the Management of Nausea/Vomiting of Pregnancy. Am. J. Perinatol. 2017, 34, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badoi, D.; Crauciuc, E.; Rusu, L.; Luca, V. Therapy with climara in surgical menopause. Rev. Med. Chir. Soc. Med. Nat. Iasi 2012, 116, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taggart, W.; Dandekar, K.; Ellman, H.; Notelovitz, M. The effect of site of application on the transcutaneous absorption of 17-beta estradiol from a transdermal delivery system (Climara). Menopause 2000, 7, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.M.; Shi, X.X.; Yang, S.W.; Qian, Q.F.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Y.Q.; Ou, P. Efficacy of clonidine transdermal patch in treatment of moderate to severe tic disorders in children. Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2017, 19, 786–789. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.; Zhang, Y.F.; Jiao, F.Y.; Guo, X.Y.; Gao, X.M. Efficacy of clonidine transdermal patch for treatment of Tourette’s syndrome in children. Chin. J. Contemp. Pediatr. 2009, 11, 537–539. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.M.; Wang, L.; Xue, H.Y.; Lu, W.L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, H.Y. In vitro and in vivo characterization of a newly developed clonidine transdermal patch for treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . McAllister, D.V.; Wang, P.M.; Davis, S.P.; Park, J.H.; Canatella, P.J.; Allen, M.G.; Prausnitz, M.R. Microfabricated Needles for Transdermal Delivery of Macromolecules and Nanoparticles: Fabrication Methods and Transport Studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacik, A.; Kopecna, M.; Vavrova, K. Permeation enhancers in transdermal drug delivery: Benefits and limitations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitragotri, S. Modeling skin permeability to hydrophilic and hydrophobic solutes based on four permeation pathways. J. Control. Release 2003, 86, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.W.; Shin, S.C. Enhanced transdermal delivery of atenolol from the ethylene-vinyl acetate matrix. Int. J. Pharm. 2004, 287, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, K.; Xu, Y.; Kang, C.; Liu, H.; Tam, K.; Ko, S.; Kwan, F.; Lee, T.M.H. Sharp Tipped Plastic Hollow Microneedle Array by Microinjection Moulding. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2012, 22, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Allen, M.G.; Prausnitz, M.R. Biodegradable Polymer Microneedles: Fabrication, Mechanics and Transdermal Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2005, 104, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffarel-Salvador, E.; Tuan-Mahmood, T.-M.; McElnay, J.C.; McCarthy, H.O.; Mooney, K.; Woolfson, A.D.; Donnelly, R.F. Potential of hydrogel-forming and dissolving microneedles for use in paediatric populations. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 489, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ita, K. Transdermal delivery of drugs with microneedles: Strategies and outcomes. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, A.; Shen, L.; Kelly, S.; Sahota, R.; Brezovic, C.; Bixler, C.; Powell, J. Steady-state bioavailability of estradiol from two matrix transdermal delivery systems, Alora and Climara. Menopause 1998, 5, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berner, B.; John, V.A. Pharmacokinetic Characterisation of Transdermal Delivery Systems. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1994, 26, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marwah, H.; Garg, T.; Goyal, A.K.; Rath, G. Permeation enhancer strategies in transdermal drug delivery. Drug Delivery 2016, 23, 564–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manca, M.L.; Zaru, M.; Manconi, M.; Lai, F.; Valenti, D.; Sinico, C.; Fadda, A.M. Glycerosomes: A new tool for effective dermal and transdermal drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 455, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitragotri, S.; Burke, P.A.; Langer, R. Overcoming the challenges in administering biopharmaceuticals: Formulation and delivery strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. An overview of clinical and commercial impact of drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, R.; Mandru, A. Enhancement of skin permeability with thermal ablation techniques: Concept to commercial products. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 817–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ita, K. Dissolving microneedles for transdermal drug delivery: Advances and challenges. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Prausnitz, M.R. Dissolving microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2113–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Ruan, J.; Quan, P.; Fang, L. High drug-loading and controlled-release hydroxyphenyl-polyacrylate adhesive for transdermal patch. J. Control. Release 2023, 353, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Liu, C.; Piao, H.; Quan, P.; Fang, L. Enhanced Drug Loading in the Drug-in-Adhesive Transdermal Patch Utilizing a Drug-Ionic Liquid Strategy: Insight into the Role of Ionic Hydrogen Bonding. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Liu, C.; Quan, P.; Fang, L. Molecular mechanism of high capacity-high release transdermal drug delivery patch with carboxyl acrylate polymer: Roles of ion-ion repulsion and hydrogen bond. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 585, 119376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, L.F.; Perera, R.; Bullen, C.; Mant, D.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Cahill, K.; Lancaster, T. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, 46–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraceni, A.; Hanks, G.; Kaasa, S. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: Evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qindeel, M.; Ullah, M.H.; Fakharud, D.; Ahmed, N.; Rehman, A.U. Recent trends, challenges and future outlook of transdermal drug delivery systems for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. J. Control. Release 2020, 327, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, P.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Q. Biocompatible nanoparticles and vesicular systems in transdermal drug delivery for various skin diseases. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 555, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Tokhy, F.S.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.M.A. Transdermal delivery of second-generation antipsychotics for management of schizophrenia; disease overview, conventional and nanobased drug delivery systems. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoellhammer, C.M.; Blankschtein, D.; Langer, R. Skin permeabilization for transdermal drug delivery: Recent advances and future prospects. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Q. Biocompatible nanoparticles and vesicular systems in transdermal drug delivery for various skin diseases. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 555, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoellhammer, C.M.; Blankschtein, D.; Langer, R. Skin permeabilization for transdermal drug delivery: Recent advances and future prospects. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Advantages |

|---|

| The concentration of the drug can be reduced due to improved bioavailability, protecting sensitive drugs from the harsh conditions of GIT |

| A simplified medication regimen leads to improved patient compliance and reduced inter and intra-patient variability |

| Dose frequency can be reduced, circumvents first pass effect of drugsCan be used for chronic conditions that require drug therapy for a long period of time |

| Prevent the hassle of parenteral therapy since TDDS are non-invasive |

| Sustained release of drugs, Offers long duration of action, maintains a more uniform plasma drug concentration |

| It delivers a steady-state infusion of a drug over an extended time.Therapeutic failures associated with intermittent dosing can also be avoided |

| Reduces the systemic drug interactions, self-administration is possibleThe drug can be terminated at any point of time by removing the transdermal patch |

| Limitations |

|---|

| The drug must have some desirable physicochemical properties for penetration through the stratum corneum |

| Skin irritation or contact dermatitis at the site of application due to the drug, excipients and enhancers of the drug used to increase percutaneous absorption |

| The barrier function of the skin changes from one site to another on the same person, person to person and with age. Variability of application site conditions |

| Only potent drugs are suitable for transdermal drug delivery |

| Unsuitable for large molecules (M.wt above 500 Daltons), drugs metabolized in the skin and undergo protein binding in the skin |

| The therapeutic efficacy of the medication can be affected by cutaneous metabolism |

| The dosing option is limited. Inconsistent absorption |

| Natural Polymers | Synthetic Elastomers | Synthetic Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulose derivatives, zein, gelatin, waxes, shellac, gums and their derivatives, proteins, natural rubber and starch | Polybutadiene, hydrin rubber, polysiloxane, silicone rubber, butyl rubber, acetonitrile, styrene-butadiene rubber, neoprene and nitrile | Polyvinyl chloride, polyvinyl alcohol, polyacrylate, polypropylene, polyethylene, polyamide, polyuria, polymethyl methacrylate, epoxy and polyvinyl pyrrolidone |

| Physicochemical Properties | Biological Properties |

|---|---|

| The molecular weight of the drug should be less than 1000 Daltons | Only potent medications with a daily dosage in the range of a few milligrams per day are appropriate |

| The drug should have an affinity for both hydrophilic and lipophilic phases | The half-life of the drug should be short and he drug should not induce an allergic response |

| The drug should possess a low melting point | Drugs that undergo degradation in the gastrointestinal tract or are rendered inactive by the hepatic first-pass effect are appropriate choices for TDDS |

| Drugs that require prolonged administration or have adverse effects on tissues other than the intended target can also be developed as TDDS |

| Solvents | Surfactants | Binary systems | Miscellaneous compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| They increase the penetration by swelling the polar pathway and by fluidizing lipids. Examples: Water, alcohols, alkyl methyl sulfoxides, dimethyl acetamide, dimethyl formamide, pyrrolidones, propylene glycol, glycerol, silicone fluids, and isopropyl palmitate. |

They are used to enhance polar pathway transport, especially of hydrophilic drugs. These compounds are, however, skin irritants. Anionic surfactants can penetrate and interact strongly with the skin and can induce large alterations in the skin. Cationic surfactants are more irritant than anionic surfactants, hence they have not been widely used as skin permeation enhancers. Of the three classes of surfactants, nonionic surfactants have been recognized as those with the least potential for irritation and are widely used. Examples: Anionic surfactants: Dioctyl sulphosuccinate, sodium lauryl sulphate, decodecylmethyl sulphoxide. Nonionic surfactants: Pluronic F127, Pluronic F68. Bile salts: Sodium taurocholate, sodium deoxycholate, sodium tauroglycocholate. |

These systems open up the heterogeneous multilaminate pathway as well as the continuous pathways. Examples: Propylene glycol-oleic acid, 1, 4 butane diol-linoleic acid. |

These include urea (hydrating and keratolytic agent), N, N dimethyl-m-toluamide, calcium thioglycolate, eucalyptol and soyabean casein. |

| Chemical penetration Enhancers |

Drugs used | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|

| Terpenes | Zidovudine Imipramine hydrochloride |

Disrupt the lipid bilayer of the stratum corneum (SC), increased drug partitioning in the SC |

| Dimethyl sulphoxide | Naloxone Hydrocortisone Naloxone |

Disrupt the lipid bilayer of the stratum corneum (SC), denature the proteins of the SC |

| Pyrrolidone | Bupranolol Ketoprofen |

Change the solubility properties of the SC |

| Alcohols | Lidocaine Thymoquinone |

Alter the drug solubility in the SC, extract the lipids of SC |

| Fatty acids | Propranolol Flurbiprofen Theophylline |

Interact with the lipid bilayer. |

| Urea | Metronidazole Indomethacin |

Disrupt the lipid bilayer of the SC, increase the hydration of the SC |

| Adhesives | Backing Membrane |

|---|---|

| The attachment of transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDS) to the skin has been achieved through the utilization of a pressure-sensitive adhesive. The adhesive is applied either on the front or rear of the device and extends around the edges. It must meet the following criteria: | It is a material that is impervious and provides protection to the product when applied to the skin. Example: Metallic plastic laminate, plastic backing with absorbent pad, occlusive base plate, adhesive foam pad (flexible polyurethane) |

| Should not cause irritation or sensitization to the skin upon contact. The medication should firmly adhere to the skin throughout the dosing period without being displaced by activities. | They are flexible and provide a good bond to the drug reservoir |

| It should have a simple removal process and should not leave a permanent residue on the skin. Should come into direct contact with the skin. Commonly employed pressure-sensitive adhesives encompass polyisobutylenes, acrylics, and silicones. | Prevent drug from leaving the dosage form through the top |

| TDDS | Use |

|---|---|

| Nitroglycerin-releasing transdermal patch (Transderm-Nitro) | Once a day medication in anginal pectoris |

| Clonidine-releasing transdermal patch (Catapres) |

7 days of therapy for hypertension |

| Estradiol-releasing transdermal patch (Estraderm) |

Treatment of menopausal syndrome for 3-4 days |

| Scopolamine-releasing transdermal patch (Transderm-Scop) |

72 hours of prophylaxis for motion sickness |

| Physico-Chemical Evaluation | In-Vitro Evaluation | In-Vivo Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Compatibility study | In-vitro release study | Animal models |

| Thickness test | Skin irritation study | Human volunteers |

| Uniformity of weight | Stability study | Toxicological evaluation |

| Drug content | ||

| Moisture content | ||

| Adhesive evaluation | ||

| Tensile strength | ||

| Folding endurance | ||

| Water vapour transmission study | ||

| Microscopic study |

| Drug name | Formulations | Approval year | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tazarotene | Lotion | 2019 | Acne |

| Asenapine | Transdermal system | 2019 | Schizophrenia |

| Trifarotene | Cream | 2019 | Acne |

| Tribanibulin | Ointment | 2020 | Actinic keratosis |

| Clascoterone | Cream | 2020 | Acne |

| Abametapira | Topical lotion | 2020 | Head lice removal |

| Calcipotriene and betamethasone dipropionate | Cream | 2020 | Plaque, psoriasis |

| Minocycline | Topical foam | 2020 | Rosacea |

| Lactic acid, citric acid and potassium bitartrate | Vaginal gel | 2020 | Contraceptive |

| Ethinylesyradiol and levonoegesterol | Transdermal system | 2020 | Contraceptive |

| Ruxolitinib | Cream | 2021 | Atopic dermatitis |

| Butenafine hydrochloride | Cream | 2021 | Fungal skin infection |

| Fentanyl | Patch | 2021 | Pain |

| Tretinoin benzoyl peroxide | Cream | 2021 | Acne |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).