Submitted:

28 August 2024

Posted:

30 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Sample Processing

2.3. PON1 Function Assay

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

2.5. Genotyping Microarray

2.6. Haplotype Phasing for PON1 Gene

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

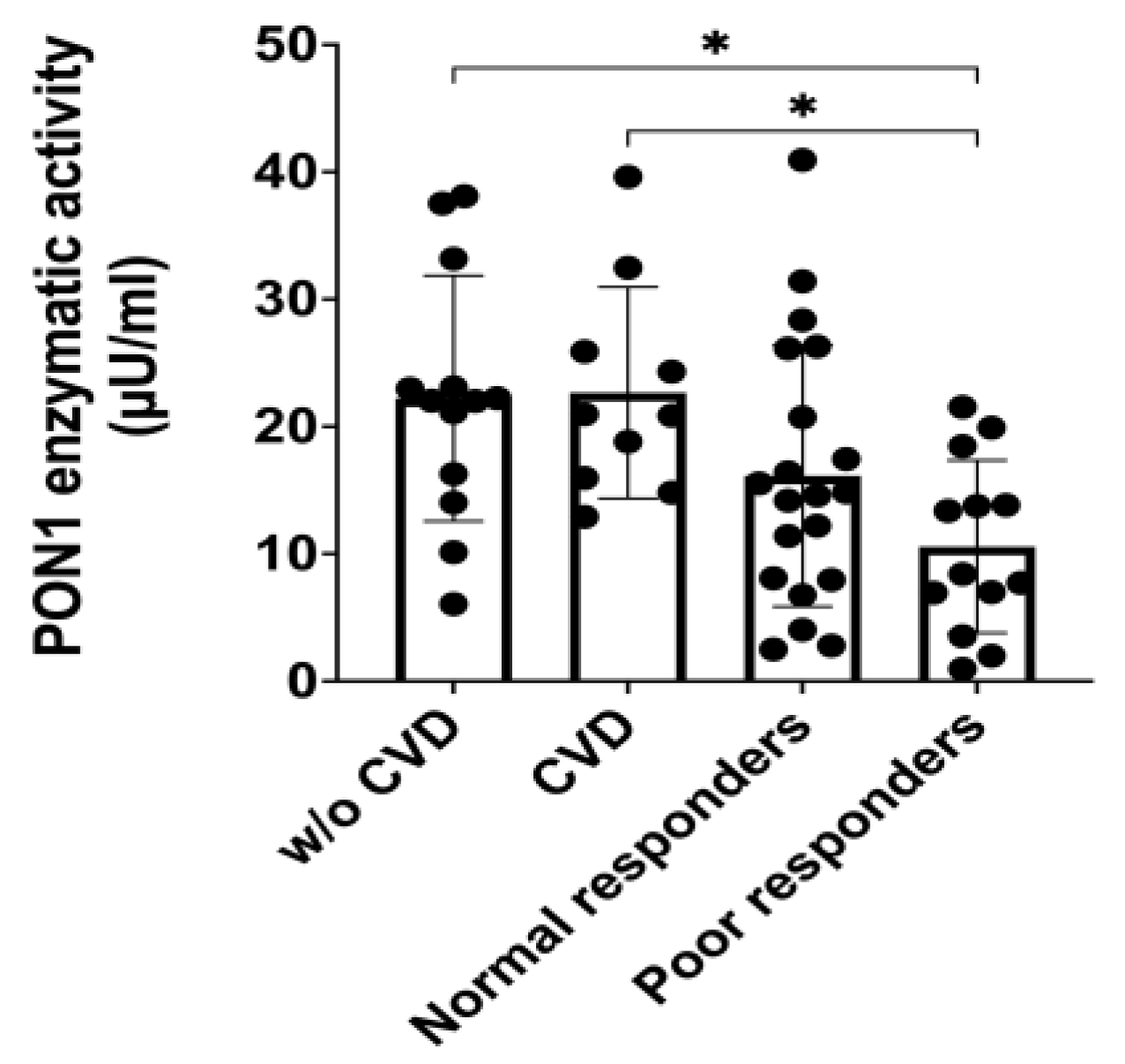

3.1. PON1 Enzymatic Activity

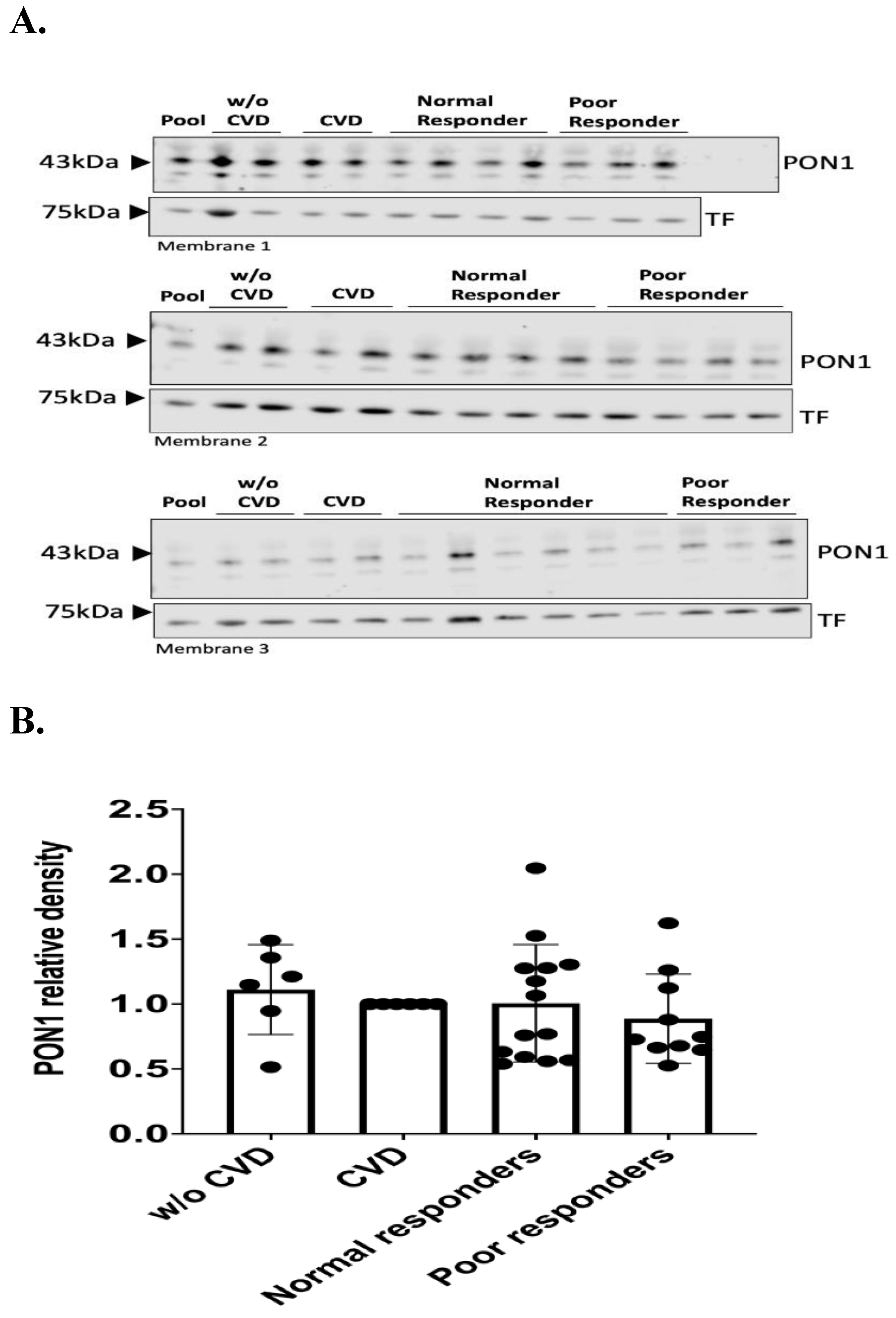

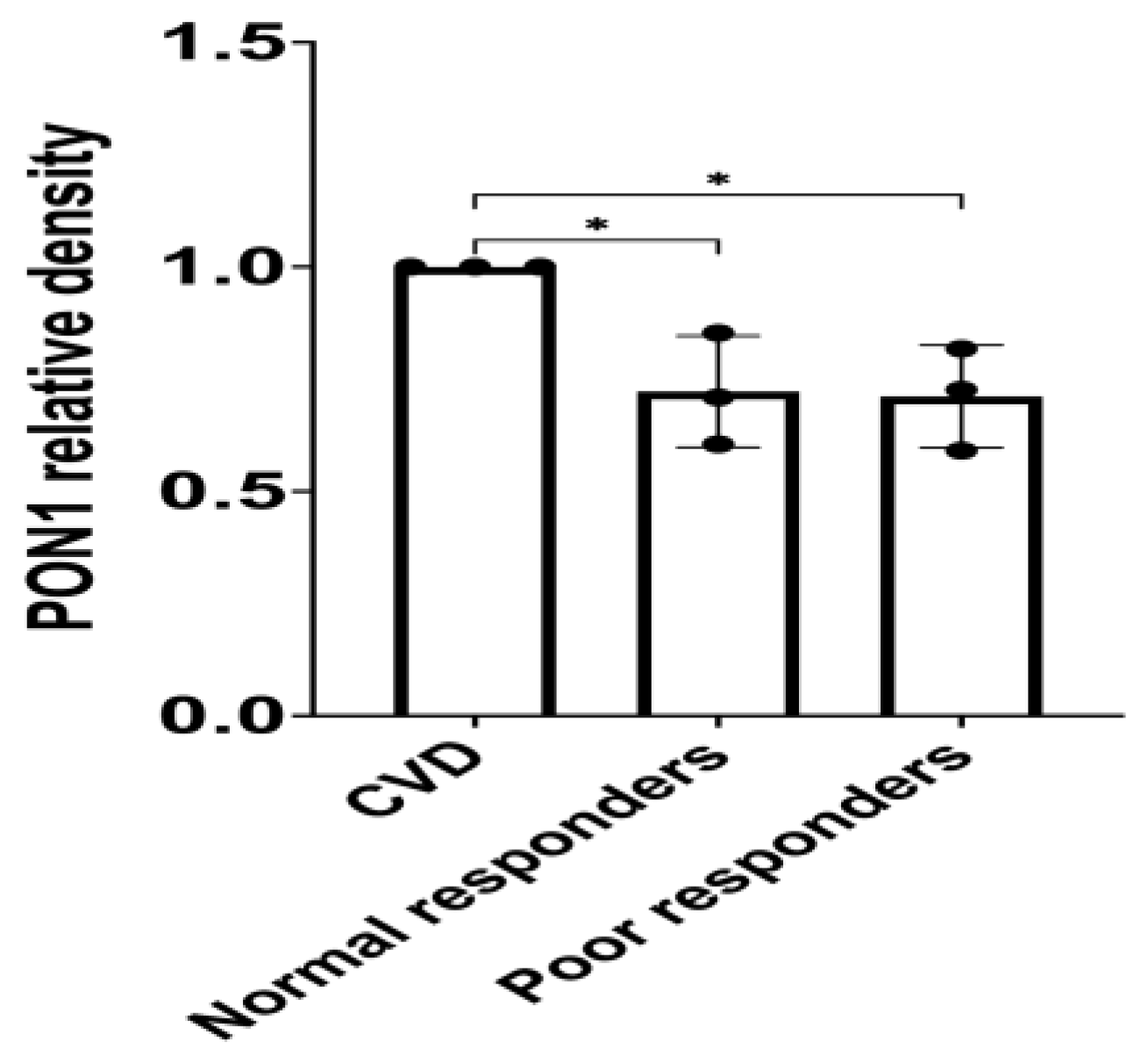

3.2. PON1 Relative Protein Abundance

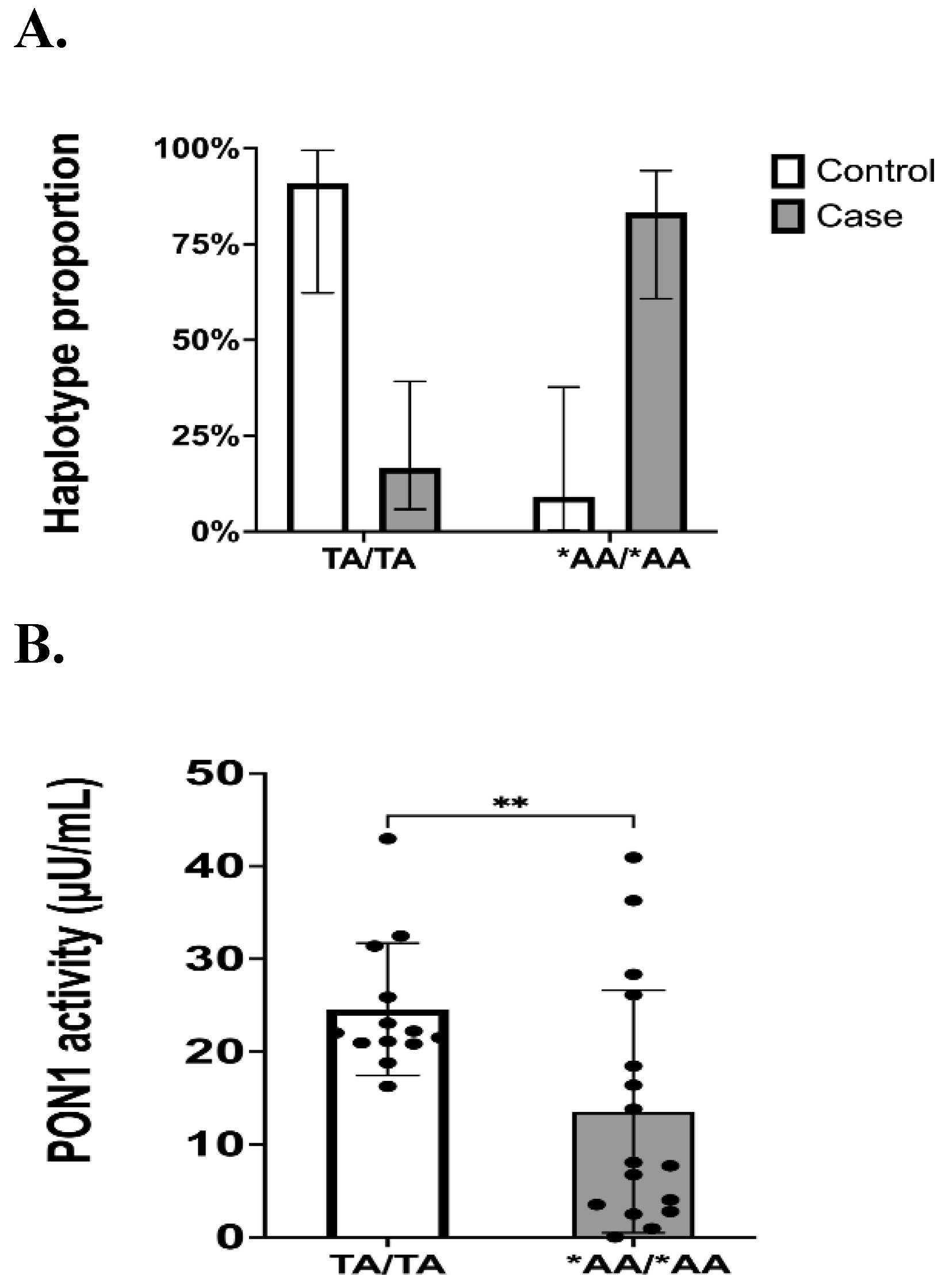

3.3. Genotypes and Haplotype Phasing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FDA. Highlights of Prescribing Information. www.fda.gov/medwatch. (2016).

- Gent, M. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 348, 1329–1339 (1996).

- Quinn, M. J. & Fitzgerald, D. J. Ticlopidine and clopidogrel. Circulation 100, 1667–1672 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.-L., Samant, S., Lesko, L. J. & Schmidt, S. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Clopidogrel. Physiol Behav 176, 139–148 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. R. et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2C19 Genotype and Clopidogrel Therapy: 2022 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther (2022). [CrossRef]

- Cavallari LH, Lee CR, Beitelshees AL, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Duarte JD, Voora D, Kimmel SE, McDonough CW, Gong Y, Dave CV, Pratt VM, Alestock TD, Anderson RD, Alsip J, Ardati AK, Brott BC, Brown L, Chumnumwat S, Clare-Salzler MJ, Coons JC, Denny JC, Dillon C, Elsey AR, Hamadeh IS, Harada S, Hillegass WB, Hines L, Horenstein RB, Howell LA, Jeng LJB, Kelemen MD, Lee YM, Magvanjav O, Montasser M, Nelson DR, Nutescu EA, Nwaba DC, Pakyz RE, Palmer K, Peterson JF, Pollin TI, Quinn AH, Robinson SW, Schub J, Skaar TC, Smith DM, Sriramoju VB, Starostik P, Stys TP, Stevenson JM, Varunok N, Vesely MR, Wake DT, Weck KE, Weitzel KW, Wilke RA, Willig J, Zhao RY, Kreutz RP, Stouffer GA, Empey PE, Limdi NA, Shuldiner AR, Winterstein AG, Johnson JA; IGNITE Network. Multisite Investigation of Outcomes with Implementation of CYP2C19 Genotype-Guided Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(2):181-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2017.07.022. PMCID: PMC5775044.

- Garabedian, T. & Alam, S. High residual platelet reactivity on clopidogrel: Its significance and therapeutic challenges overcoming clopidogrel resistance. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 3, 23–37 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Mackness, M. I., Arrol, S. & Durringtorm, P. N. Paraoxonase prevents accumulation of lipoperoxides in low-density lipoprotein. FEBS Journal 286, 152–154 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Mackness, M. & Mackness, B. Human Paraoxonase-1 (PON1): Gene structure and expression, promiscuous activities and multiple physiological roles. Gene 567, 12–21 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Serrato, M. & Marian, A. J. A Variant of Human Paraoxonase/Arylesterase (HUMPONA) Gene Is a Risk Factor for Coronary Artery Disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 96, 3005–3008 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Mackness, B., Mackness, M. I., Arrol, S., Turkie, W. & Durrington, P. N. Effect of the molecular polymorphisms of human paraoxonase (PON1) on the rate of hydrolysis of paraoxon. Br J Pharmacol 122, 265–268 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J. et al. Gln-Arg192 polymorphism of paraoxonase and coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetes. The Lancet 346, 869–872 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Mackness, B. et al. Paraoxonase Status in Coronary Heart Disease Are Activity and Concentration More Important Than Genotype? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21, 1451–1457 (2001).

- Norris, E. T. et al. Genetic ancestry, admixture and health determinants in Latin America. BMC Genomics 19, 861 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Sirugo G, Williams SM, Tishkoff SA. The Missing Diversity in Human Genetic Studies. Cell. 2019;177(1):26-31. [CrossRef]

- Bouman HJ, Schömig E, van Werkum JW, Velder J, Hackeng CM, Hirschhäuser C, Waldmann C, Schmalz HG, ten Berg JM, Taubert D. Paraoxonase-1 is a major determinant of clopidogrel efficacy. Nat Med 17(1), 110-116 (2011). Erratum in: Nat Med 17(9), 1153 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Abcam. ab241044 Paraoxonase 1 Activity Assay Kit. 1–20 Preprint at (2018).

- Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: A toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 81, (2007).

- Delaneau, O., Zagury, J. F. & Marchini, J. Improved whole-chromosome phasing for disease and population genetic studies. Nat Methods 10, 5–6 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Suarez DF, Botton MR, Scott SA, Tomey MI, Garcia MJ, Wiley J, Villablanca PA, Melin K, Lopez-Candales A, Renta JY, Duconge J. Pharmacogenetic association study on clopidogrel response in Puerto Rican Hispanics with cardiovascular disease: A novel characterization of a Caribbean population. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 11, 95-106 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Cartagena, E. et al. Quantitative Proteomic Profile of Caribbean Hispanics with Resistance to Clopidogrel. The FASEB Journal 34, 1 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mackness, B., Turkie, W. & Mackness, M. Paraoxonase-1 (PON1) promoter region polymorphisms, serum PON1 status and coronary heart disease. Archives of Medical Science 9, 8–13 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Shunmoogam, N., Naidoo, P. & Chilton, R. Paraoxonase (PON)-1: A brief overview on genetics, structure, polymorphisms and clinical relevance. Vasc Health Risk Manag 14, 137–143 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Aviram, M. et al. Human serum paraoxonase (PON1) is inactivated by oxidized low density lipoprotein and preserved by antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med 26, 892–904 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Shih, D. M. et al. Mice lacking serum paraoxonase are susceptible to organophosphatetoxicity and atherosclerosis. Nature 394, 284–287 (1998).

- Mackness, B., Hunt, R., Durrington, P. N. & Mackness, M. I. Increased Immunolocalization of Paraoxonase, Clusterin, and Apolipoprotein A-I in the Human Artery Wall with the Progression of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17, (1997). [CrossRef]

- Gong, I. Y. et al. Clarifying the importance of CYP2C19 and PON1 in the mechanism of clopidogrel bioactivation and in vivo antiplatelet response. Eur Heart J 33, 2856–2864 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Hulot, J. S. et al. CYP2C19 but not PON1 genetic variants influence clopidogrel pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and clinical efficacy in post-myocardial infarction patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 4, 422–428 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. P. et al. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene variants are not associated with clopidogrel response. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90, 568–574 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Sibbing, D. et al. No association of paraoxonase-1 Q192R genotypes with platelet response to clopidogrel and risk of stent thrombosis after coronary stenting. Eur Heart J 32, 1605–1613 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Tresukosol, D. et al. Effects of cytochrome P450 2C19 and paraoxonase 1 polymorphisms on antiplatelet response to clopidogrel therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE 9, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Leviev, I., Negro, F. & James, R. W. Two Alleles of the Human Paraoxonase Gene Produce Different Amounts of mRNA: An Explanation for Differences in Serum Concentrations of Paraoxonase Associated with the (Leu-Met54) Polymorphism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17, 2935–2939 (1997).

- Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. Association, correlation and causation. Nat Methods 12, 899–900 (2015).

- Claudio-Campos, K. I. et al. CYP2C9∗61, a rare missense variant identified in a Puerto Rican patient with low warfarin dose requirements. Pharmacogenomics 20, 3–8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Brophy, V. H. et al. Effects of 5′ regulatory-region polymorphisms on paraoxonase-gene (PON1) expression. Am J Hum Genet 68, 1428–1436 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Leviev, I. & James, R. W. Promoter Polymorphisms of Human Paraoxonase PON1 Gene and Serum Paraoxonase Activities and Concentrations. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20, 516–521 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. et al. Statistical considerations of optimal study design for human plasma proteomics and biomarker discovery. J Proteome Res 11, 2103–2113 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Handler DC, Pascovici D, Mirzaei M, Gupta V, Salekdeh GH, Haynes PA. The Art of Validating Quantitative Proteomics Data. Proteomics. 2018; 18(23): e1800222. [CrossRef]

- Geyer PE, Holdt LM, Teupser D, Mann M. Revisiting biomarker discovery by plasma proteomics. Mol Syst Biol. 2017;13(9):942. [CrossRef]

- Mölleken C, Sitek B, Henkel C, Poschmann G, Sipos B, Wiese S, Warscheid B, Broelsch C, Reiser M, Friedman SL, Tornøe I, Schlosser A, Klöppel G, Schmiegel W, Meyer HE, Holmskov U, Stühler K. Detection of novel biomarkers of liver cirrhosis by proteomic analysis. Hepatology. 2009; 49(4):1257-66. [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T. M. et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 143, E984–E1010 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Abu-Saleh, N., Aviram, M. & Hayek, T. Aqueous or lipid components of atherosclerotic lesion increase macrophage oxidation and lipid accumulation. Life Sci 154, 1–14 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Keaney, J. F. et al. Obesity and systemic oxidative stress: Clinical correlates of oxidative stress in the Framingham study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23, 434–439 (2003).

- Münzel, T. et al. Impact of Oxidative Stress on the Heart and Vasculature: Part 2 of a 3-Part Series. Journal of the American College of Cardiology vol. 70 212–229 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.035 (2017).

- Meisinger, C., Freuer, D., Bub, A. & Linseisen, J. Association between inflammatory markers and serum paraoxonase and arylesterase activities in the general population: A cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis 20, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y. et al. Low human paraoxonase predicts cardiovascular events in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 46, 239–242 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Murillo González, F. E. et al. PON1 concentration and high-density lipoprotein characteristics as cardiovascular biomarkers. Archives of Medical Science – Atherosclerotic Diseases 4, 47–54 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. et al. Association between PON1 activity and coronary heart disease risk: A meta-analysis based on 43 studies. Mol Genet Metab 105, 141–148 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. et al. PON1 L55M and Q192R gene polymorphisms and CAD risks in patients with hyperlipidemia: Clinical study of possible associations. Herz 43, 642–648 (2018).

- Luo, J. Q., Ren, H., Liu, M. Z., Fang, P. F. & Xiang, D. X. European versus Asian differences for the associations between paraoxonase-1 genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cell Mol Med 22, 1720–1732 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Macharia, M., Kengne, A. P., Blackhurst, D. M., Erasmus, R. T. & Matsha, T. E. Paraoxonase1 genetic polymorphisms in a mixed ancestry African population. Mediators Inflamm 2014, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Garin, M.-C. B. et al. Paraoxonase Polymorphism Met-Leu54 Is Associated with Modified Serum Concentrations of the Enzyme A Possible Link between the Paraoxonase Gene and Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes. Journal of Clinical Investigation 99, 62–66 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Holland, N. et al. Paraoxonase polymorphisms, haplotypes, and enyzme activity in Latino mothers and newborns. Environ Health Perspect 114, 985–991 (2006).

- Bhattacharyya, T. et al. Relationship of paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene polymorphisms and functional activity with systemic oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 299, 1265–1276 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Kumru S, Aydin S, Aras A, Gursu MF, Gulcu F. Effects of surgical menopause and estrogen replacement therapy on serum paraoxonase activity and plasma malondialdehyde concentration. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2005;59(2):108-12. [CrossRef]

- Taşkiran, P. et al. The relationship between paraoxanase gene Leu-Met (55) and Gln-Arg (192) polymorphisms and coronary artery disease. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 37, 473—478 (2009).

- Watzinger, N. et al. Human Paraoxonase1 Gene Polymorphisms and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Community-Based Study. Cardiology 98, 116–122 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Barrès, R. et al. Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metab 15, 405–411 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Bonder, M. J. et al. Disease variants alter transcription factor levels and methylation of their binding sites. Nat Genet 49, 131–138 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Breton, C. v. et al. Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure affects global and gene-specific DNA methylation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180, 462–467 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Waterland, R. A. & Jirtle, R. L. Transposable Elements: Targets for Early Nutritional Effects on Epigenetic Gene Regulation. Mol Cell Biol 23, 5293–5300 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, R. et al. Distribution of paraoxonase PON1 gene polymorphisms in Mexican populations. Its role in the lipid profile. Exp Mol Pathol 80, 85–90 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, G. et al. Genetic polymorphism in paraoxonase 1 (PON1): Population distribution of PON1 activity. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 12, 473–507 (2009). [CrossRef]

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Caribbean Hispanics residing in Puerto Rico Both sexes (i.e., males/females) Age ≥ 21 years old Receiving clopidogrel (75 mg/day) for therapeutic indications (ACS, stable CAD, PAD) over at least 6 months. No clinically active hepatic abnormality. The ability to understand the requirements of the study. The ability to comply with the study procedures and protocols. A female patient is eligible to enter the study if she is of child-bearing potential and not pregnant or nursing, or not of child-bearing potential. |

Non-Hispanic patients Currently enrolled in another active research protocols BUN > 30 and creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL Hematocrit (Hct) ≤ 25% Nasogastric or enteral feedings Acute illness (e.g., sepsis, infection, anemia) HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B patients Alcoholism and drug abuse Patients with any cognitive and mental health impairment Sickle cell patients Active malignancy Patients taking another antiplatelet |

| Characteristics | All Patients (n = 36) | Normal Responders (n= 20) | Poor Responders (n= 16) | p value | Negative Controls (n = 13) | Positive Controls (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 67 ± 10 | 67 ± 9 | 68 ± 10 | 0.9817 | 48 ± 11 | 53 ± 18 |

| Sex (%, n) | 0.5152 | |||||

| Female | 56% (20) | 50% (10) | 63% (10) | 53.8% (7) | 54.5% (6) | |

| Male | 44% (16) | 50% (10) | 38% (6) | 46.2% (6) | 45.5% (5) | |

| BMI | 30.9 ± 5.9 | 29.6 ± 5.2 | 32.6 ± 6.5 | 0.1291 | 28.9 ± 6.2 | 30.1 ± 5.5 |

| Current smoker (%, n) | 19% (7) | 20% (4) | 19% (3) | > 0.9999 | 15.4% (2) | 18.2% (2) |

| Diabetes Mellitus (%, n) | 92% (33) | 90% (18) | 94% (15) | > 0.9999 | 91% (10) | |

| Dyslipidemia (%, n) | 92% (33) | 95% (19) | 88% (14) | 0.5742 | 91% (10) | |

| Hypertension (%, n) | 97% (35) | 95% (19) | 100% (16) | > 0.9999 | 100% (11) | |

| Clopidogrel indication (%, n) | ||||||

| Stable CAD or ACS | 72.2% (26) | 75% (15) | 68.75% (11) | |||

| PAD | 27.78% (10) | 25% (5) | 31.25% (5) | 0.7225 | ||

| MI, STEMI & NSTEMI (%, n) | 2.77% (1) | 0% (0) | 6.25% (1) | 0.4444 | ||

| Coronary artery stents (%, n)# | 36.1% (13) | 40% (8) | 31.3% (5) | 0.7314 | ||

| Aspirin Users (%, n) | 64% (23) | 60% (12) | 69% (11) | 0.7314 | 0% (0) | |

| CCB Users (%, n) | 31% (11) | 35% (7) | 25% (4) | 0.7182 | 27.3% (3) | |

| Cilostazol Users (%, n) | 14% (5) | 15% (3) | 13% (2) | > 0.999 | ||

| PPI Users (%, n) | 28% (10) | 20% (4) | 38% (6) | 0.2853 | 18.2% (2) | |

| Statins Users (%, n) | 81% (29) | 90% (18) | 69% (11) | 0.2036 | 82% (9) | |

| CYP2C19*2 status (MAF, %, n)* | 13.9% (10) | 12.5% (5) | 15.6% (5) | 0.7426 | 15.4% (4) | 13.6% (3) |

| Variable | Negative Controls (n = 13) | Positive Controls (n = 11) | Normal Responders (n = 20) | Poor Responders (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs662 (p.Q192R) | ||||

| 4 (31%) | 5 (45.5%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (12.5%) | |

| QR | 7 (54%) | 4 (36.4%) | 11 (55%) | 11 (68.75%) |

| RR | 2 (15%) | 2 (18.1%) | 6 (30%) | 3 (18.75%) |

| MAF | 42.31% | 36.4% | 57.5% | 53.12% |

| 95%CI | 19.33 - 68.05 | 13.81 - 60.94 | 39.07 - 73.50 | 34.21 - 74.18 |

| rs854560 (p.L55M) | ||||

| LL | 9 (69.2%) | 6 (54.5%) | 10 (50%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| LM | 4 (30.8%) | 2 (18.2%) | 7 (35%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| MM | 0 (0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| MAF | 15.38% | 36.4% | 32.5% | 18.75% |

| 95%CI | 2.96 - 44.80 | 19.33 - 68.05 | 17.93 - 50.66 | 8.07 - 41.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).