Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods.

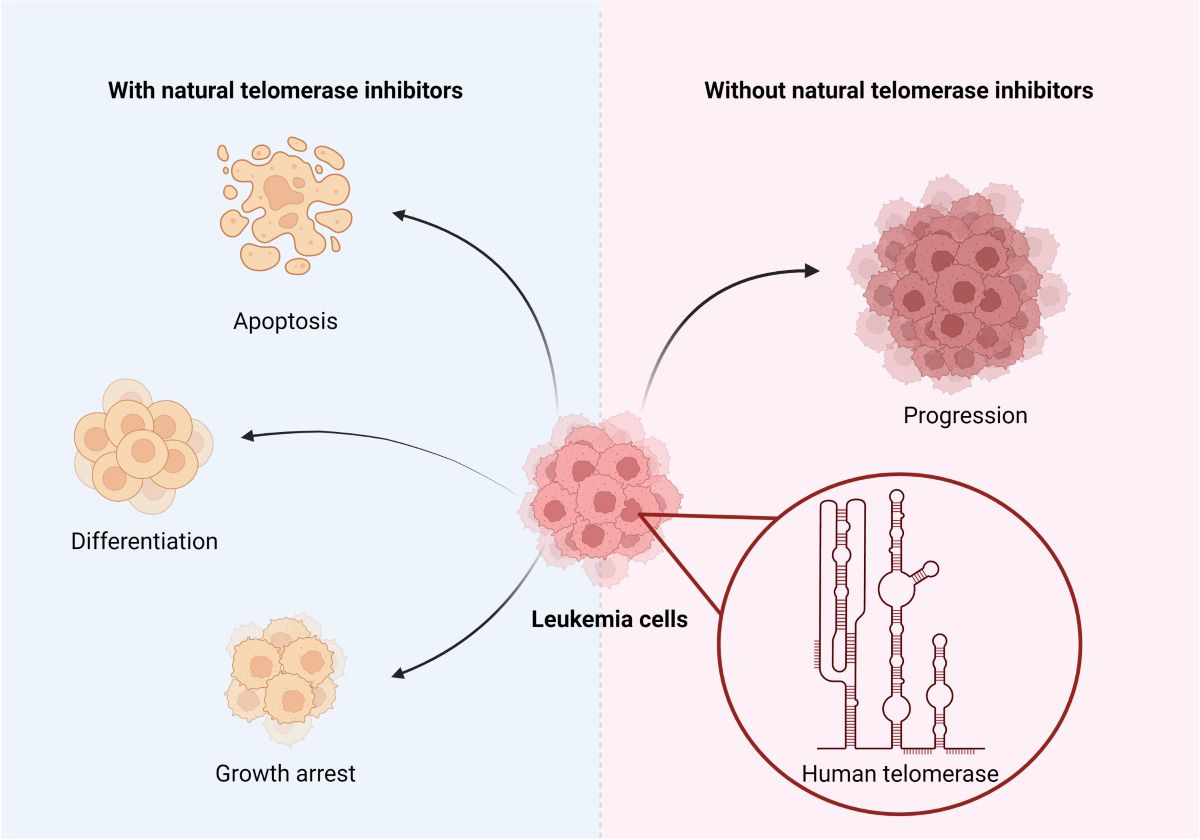

3. Natural substances inhibiting telomerase

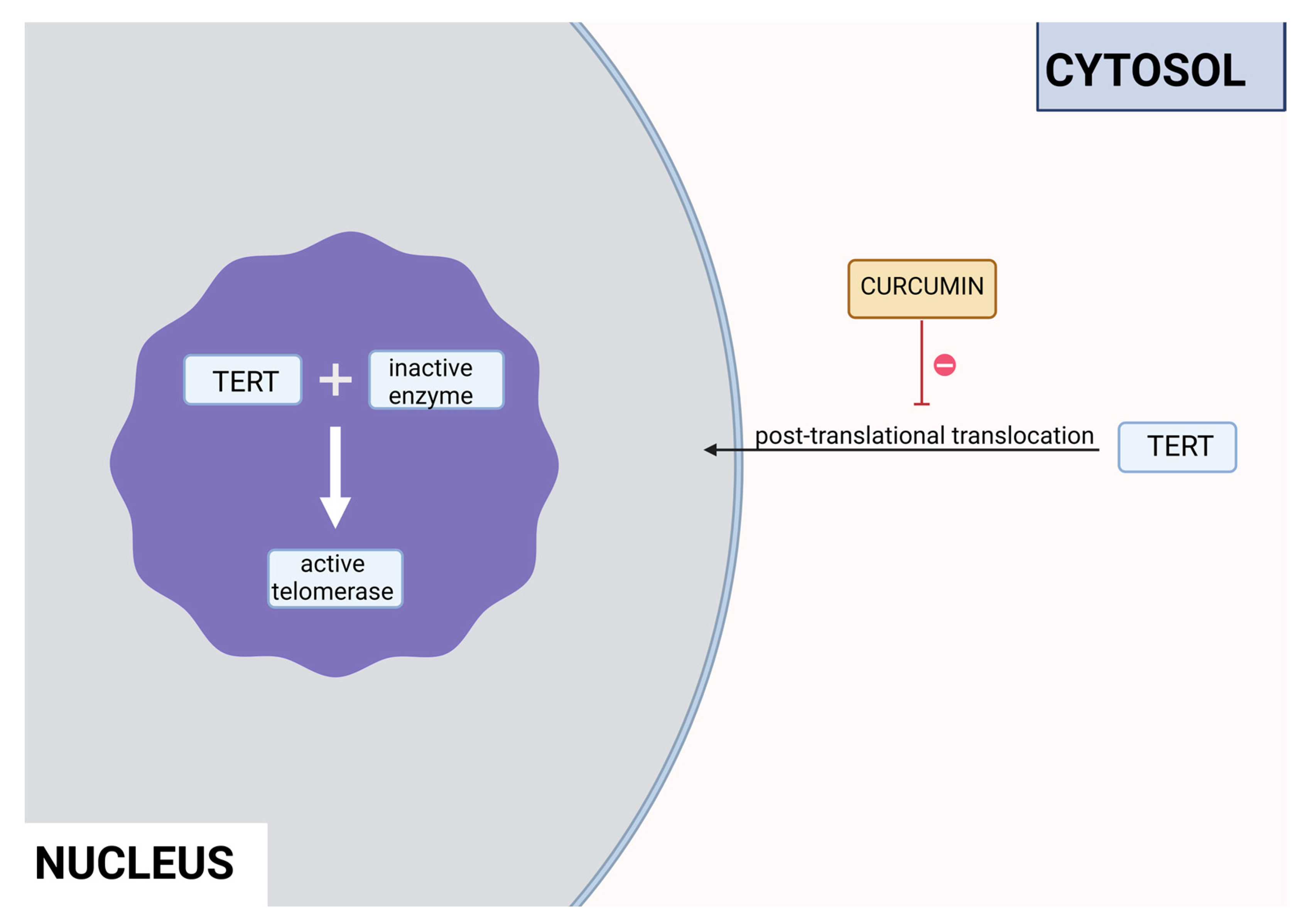

3.1. Polyphenols

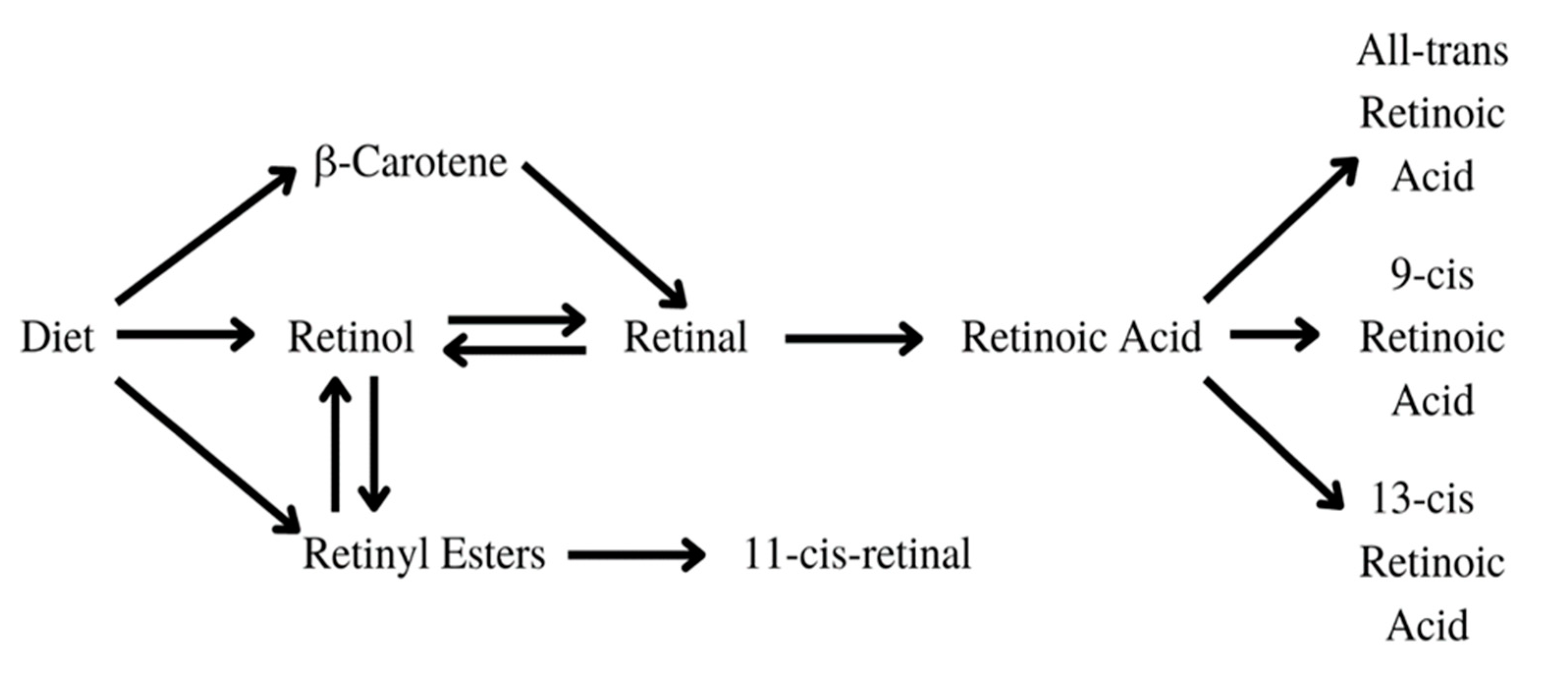

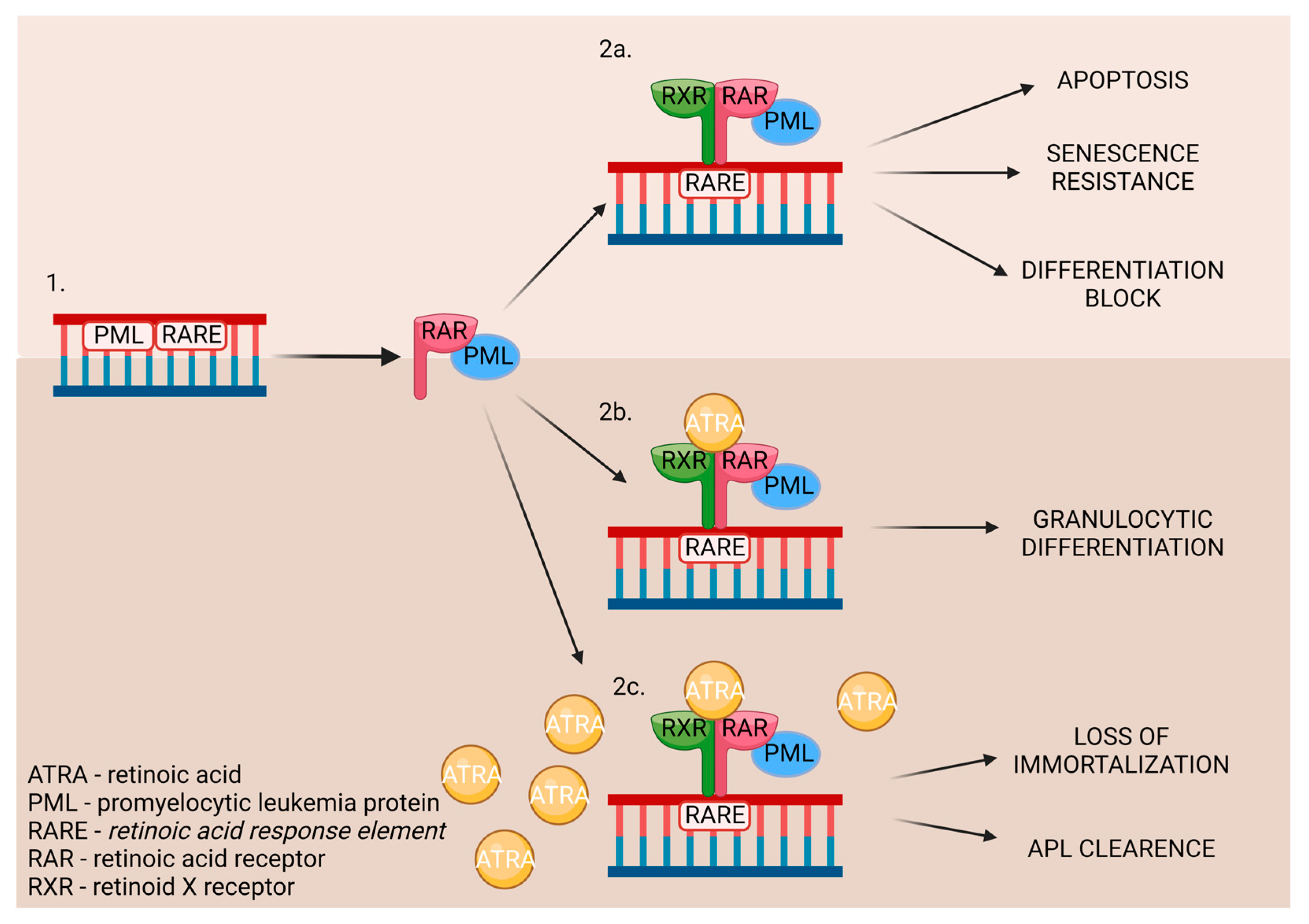

3.2. Vitamin A

3.3. Vitamin D

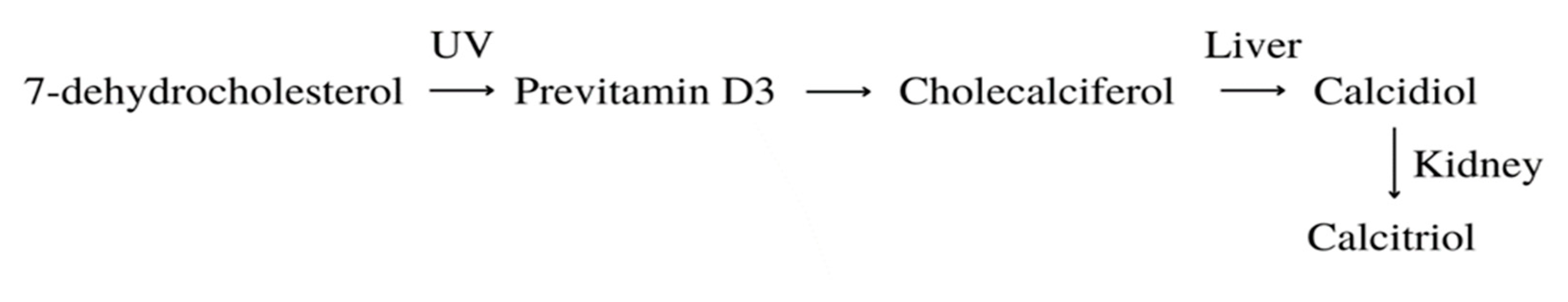

3.4. Vitamin E

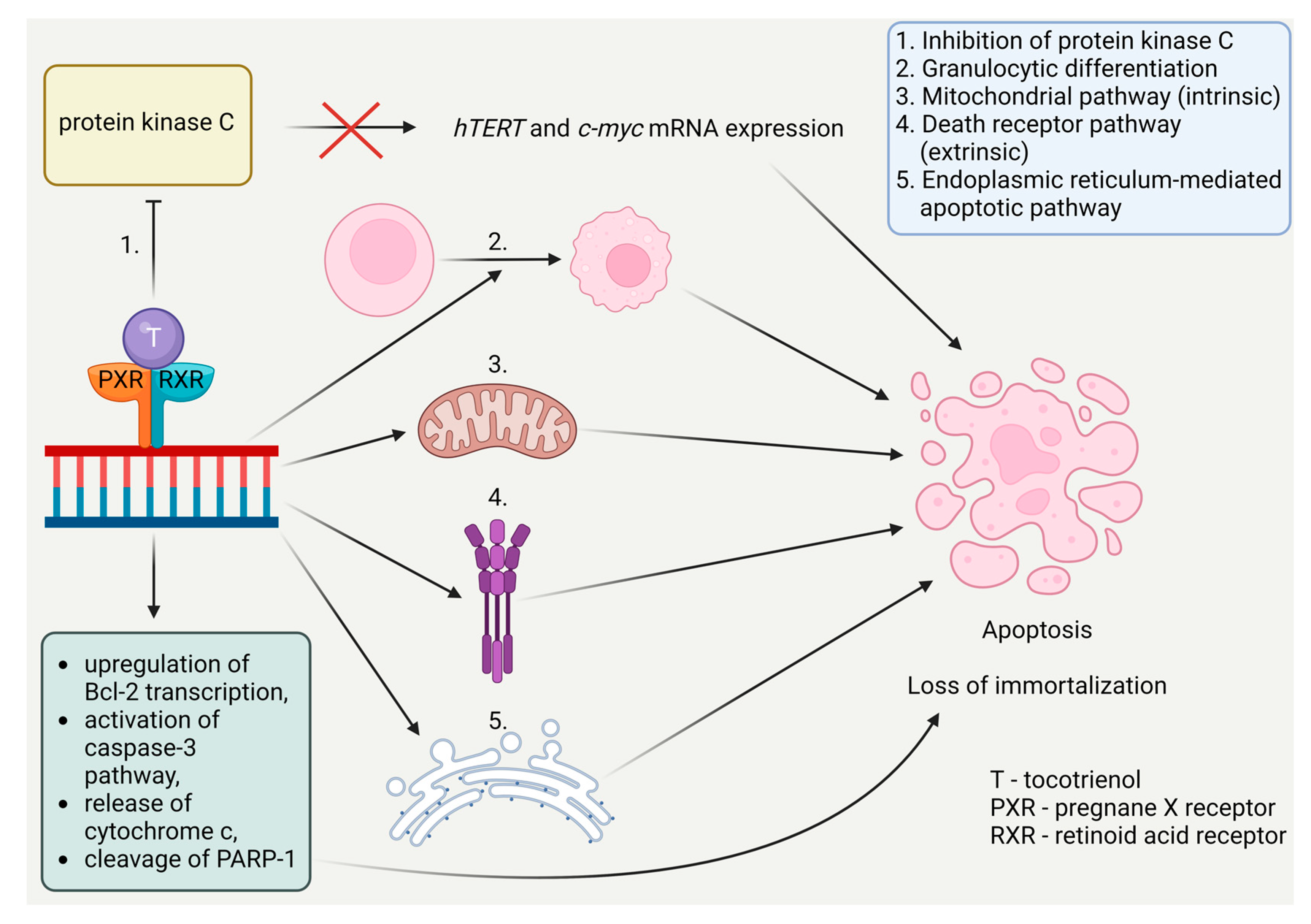

3.5. Fatty acids

3.6. Other substances

| Substance | Natural occurance | Cell line | Dose applied | Durance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcumin | Turmeric | HL-60 | 1, 10, 50 μM | 24 h | [13] |

| HL-60 | 10, 15, 20, 40 μM | 24 and 48 h | [14] | ||

| K-562 | 1, 10, 50 μM | 6, 16, 24, 48 h | [15] | ||

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) | Green tea | HL-60 | 50 μM | 3, 6, 9, 12 days | [16] |

| Jurkat | 30, 50, 70, 85, 100 μM | 24, 48, 72 h | [17] | ||

| Indole-3-carbinol | Broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, cabbage, kale | NALM-6 | 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 μM | 24, 48 h | [19] |

| K-562 | 100, 200, 400 μM | 24, 48 h | [20] | ||

| Butein | Stem bark of cashews, the heartwood of Dalbergia odonifea, Rhus verniciflua, and Caragena jubata | U937, THP-1, HL60, K562 | 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 μM | 24 h | [21] |

| Gossypol | Seeds, roots and stems of cotton plants | HL-60 | 1, 2, 4.5, 6, 10 μM | 24, 48, 72, 96 h | [22] |

| U937, HL60, THP-1, K562 | 5, 10, 20 μM | 24 h | [23] | ||

| Retinoic acid | Yellow, green, red, and leafy vegetables, yellow fruits | HL-60 | 1 μM | 12 days | [27] |

| 242 cases of APL | 60 mg/kg/day | 2 years | [171] | ||

| 124 cases of cAPL | 25mg/m2/day | 5 years | [172] | ||

| Eμ-TCL1 mice | 1 μM | 24, 48 h | [35] | ||

| 9cUAB30 | Novel retinoid | HL-60d | 5 μM | 12 days | [29] |

| Growth factor binding protein 7 | Human insulin recombinant | HL60, KG1a, THP1, HEK293T | 100 μg/mL, 300 μg/mL, 10 mg/kg, 12 mg/kg | 48, 72, 120 h, 7, 14 days, 16 weeks | [30] |

| Vitamin D | Produced in the human body form 7-dehydrocholesterol; fish oil, egg yolk | HL-60 | 10-8M | 3 days | [173] |

| U937 | 10-9-10-7M | 48, 72 h | [174] | ||

| 26 cases of AML | 1 μg/day | 2 x 5 weeks | [175] | ||

| 17 cases of elderly AML | 100,000 IU/week | 6 months | [176] | ||

| EB 1089 | Vitamin D3 analog | HL-60, U937 | 5x10-10M | 96 h | [42] |

| 1,25(OH)2-16-ene-5,6-trans-D3 | Vitamin D3 analog | HL-60 | 10-7M | 4 days | [43] |

| Vitamin E | Vegetable oil, seeds, nuts, grains | U937, KG-1 | 10-50 μM | 24 h | [52] |

| K562 | 100 μM | 48 h | [177] | ||

| 25 cases of AML | 400 IU/day | 30 days | [54] | ||

| 2396 study/2235 control | 600 IU/day | 10 years | [56] | ||

| Valproic acid | Valeriana officinalis | HL-60, HL-60A | 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 mM | 24, 48, 72 h | [60] |

| 18 + 114 patients of AML | 400 mg/day + from day 3 60 - 150 mg/L | 2 x 21 days, 3 x 21 days | [69] | ||

| 31 cases of elderly AML/RAEB | 5 mg/kg daily | 2-23 months | [70] | ||

| 23-Hydroxybetulinic acid | Pulsatilla chinensis | HL-60 | 1 - 1000 μM | 3, 6, 12, 24 h | [62] |

| Ω-3 fatty acids (DHA, EPA) | Seafood, especially fatty fish, nuts, seeds, plant oils | 16 cases of Rai Stage 0-1 CLL | 1. month: 3 x 1250 mg/day 2. month: 6 x 1250 mg/day 3. – 12. month: 9 x 1250 mg/day |

12 months | [65] |

| 14 cases of AML | 100 mL/day | 2 years | [67] | ||

| 60 cases of cALL (30 study/30 control) | 1000 mg/day | 6 months | [66] | ||

| SQDG | Azadirachta indica | MOLT-4 | 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 μM | 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 48, 72 h | [72] |

| Genistein | Lupin, fava beans, soybeans, psoralea | HL-60 | 50 μM | 24, 48, 72 h | [11] |

| Sulforaphane | Cruciferous vegetables | HL-60 | 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 μM | 24, 48 h | [74] |

| Melatonin | Synthesized in a human pineal gland, eggs, fish, nuts | RS4-11 (MLL-AF4+ B-ALL), MOLM-13 (MLL-AF9+ AML), Nalm-6 (non MLL-r B-ALL) | 1, 2, 3 mM | 24, 48, 72 h | [75] |

| Crocin | Crocus sativus | Jurkat | 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 mg/mL | 12, 24, 26, 48 h | [78] |

| Withaferin-A | Withania somnifera | U937 | 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 μM | 12, 24 h | [79] |

| Diosgenin | Trigonella foenum-graecum | K562 | 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 μM | 48 h | [83] |

| Berberine | Berberis vulgaris, Mahonia aquifolium, Berberis aristate, Hydrastis canadensis | HL-60 | 5, 10, 15, 25, 50 μM | 24, 48, 72, 96 h | [86] |

| Apigenin | Basil, oregano, onion, parsley, wine, tea, beer | HL-60, U937, THP-1 | 25, 50, 75, 100 μM | 24 h | [89] |

| Cordycepin | Cordyceps militaris | THP-1, H937 | 10, 20, 30 μM | 24 h | [91] |

| Tanshinone IIA | Salvia miltiorrhiza | HL-60, K562 | 0.5 μg/mL | 5, 6 days | [93] |

| Tanshinone I | Salvia miltiorrhiza | U937, THP-1, SHI 1 | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 μM | 24, 48, 72 h | [95] |

| Rapamycin | Streptomyces hygroscopius bacteria | Jurkat | 1, 10, 100 nM | 8, 16, 24, 32, 72 h | [98] |

| Caffeic acid undecyl ester | Daphne oleoides | NALM-6 | 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, 1, 3 μM | 4, 18 h | [101] |

| NALM-6 | 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, 1μM | 6, 12, 24, 72 h | [100] | ||

| β-Lapachone | Handroanthus impetiginosus | U937, K562, HL60, THP-1 | 1, 2, 3, 4 μM | 24 h | [103] |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | Panax ginseng | CD34+CD38- LSCs | 20, 40, 80 μM | 24, 48, 72 h | [104] |

| U937 | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 0.8, 2 mg/mL | 24, 48, 72 h | [105] | ||

| Bengalin | Venom of Deccanometrus bengalensis | U937, K562 | 0.3, 0.75, 1.5, 1.85, 2.05, 2.23, 3, 3.7, 4.1, 4.5, 6 μg/mL | 24, 48 h | [112] |

| U937 | 1.8, 3.7 μg/mL | 12, 24 h | [110] | ||

| Ascorbic acid | Citrus fruits, green and leafy vegetables | CD34+, HL-60, U937 | 8, 20 mM | 24 h | [117] |

| Telomestatin | Streptomyces anulatus | U937 | 1, 2, 5, 10 μM | 48 h, 0 – 60 days | [119] |

| Silymarin | Silybum marianum | K562 | 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 μg/mL | 24, 48, 72 h | [121] |

| Tianshengyuan-1 | A mixture of various Chinese herbs | HL-60, PBMCs, CD34+ HSCs | 31.2, 62.5 μg/mL | 24 h | [123] |

| Wogonin | Scutellaria baicalensis | HL-60 | 0.5, 1, 2, 3 mg/mL 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 μM | 24 h | [126] |

| Interferon alpha | Synthesized in the human organism by plasmacytoid dendritic cells | 42 study/42 control of AML | 3 x week 3 mln IU | 12 – 18 months | [129] |

| 36 | -1. before HCT, 14., 28., 42. (+/- 7) days 45, 90, 180 μg | 24 months | [130] | ||

| Angelica sinensis polysaccharide | Angelica sinensis | K562, CD34+CD38− | 20, 40, 80 μg/mL | 48 h | [132] |

| FA-2-b-ß fraction (an RNA-protein complex) | Agaricus blazei Murill | HL-60 | 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 μg/mL | 24, 48, 72, 96 h | [136] |

| Platycodin D | Platycodon grandiflorus | U937, THP-1, K562 | 5, 10, 15, 20 μM | 48 h | [138] |

| Pectenotoxin-2 | Dinophysis species | U937, THP-1, HL-60 | 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 ng/mL | 72 h | [139] |

| Camptothecin | Camptotheca acuminata | HL-60 | 1 mg/L | 2, 4, 6 h | [142] |

| Triptonide | Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F | U937, HL-60 | 0-10, 15, 20 nM 2, 4 mg/kg |

72 h, 3, 6, 9, 14, 21 days | [148] |

| Constunolide | Stem bark of Magnolia sieboldii | NALM-6 | 2, 6, 8, 10 μM | 1, 2, 4, 6 h | [149] |

| Salvicine | Salvia prionitis (modified) | HL-60 | 2.5, 5, 10, 20 μM | 2, 4, 6 h | [150] |

| Patensin | Pulsatilla patens var. multifida | HL-60 | 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 mmol/L | 3, 6, 12, 24 h | [151] |

| Dideoxypetrosynol A | Marine sponge Petrosia sp. | U-937 | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1 μg/mL | 48 h | [152] |

| (Z)-stellettic acid C | Stelletta sp. sponges | U-937 | 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 μg/mL | 48 h | [153] |

| Trichostatin A | Culture broth of Streptomyces platensis | U-937 | 15, 30, 45, 60, 75 nM | 48 h | [154] |

| Homoharringtonine | Chinese evergreen Cephalotaxus harringtonia | HL-60 | 5, 10, 50, 100, 500 μg/L | 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 h | [155] |

| Baicalin | Scutellaria baicalensis | HL-60 | HL-60 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 μg/mL | 12, 24, 48 h | [156] |

| Manisa propolis | Substance collected by honeybees | 4 childhood leukemia cases (3 ALL, 1 CML) | 15, 30, 60 ng/mL | 24, 48, 72 h | [157] |

| CCFR-CEM | 0.03 μg/mL | 24, 48, 72, 96 h | [158] | ||

| D-galactan sulfate | Gymnodinium sp. A3 | K562 | 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1 μg/mL | 15, 45 min | [159] |

| Oridonin | Isodon rubescens, Rabdosia rubescens | HL-60 | 4, 8, 16, 24 μM | 12, 36, 48, 60, 72 h | [162] |

| HPB-ALL | 16, 24, 32, 40, 56 μM | 24, 48, 72 h | [164] | ||

| Gold nanoparticles | Gold | HL-60 | 1-1000 μg/mL, 2500 mg/kg | 28 days | [168] |

| Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound | Ultrasound | K562, U937 | 0.3, 0.5, 0.67 MHz | 60 s cycle 1, 10, 20, 30 ms pulse duration 72 h 2 min cycle 1, 10, 20, 30, 100 ms pulse duration 2 days |

[170] |

4. Conclusions

- Their ambiguous effect on chemoprevention;

- The lack of data indicating the optimal and toxic doses;

- The lack of data regarding their potential side effects;

- The lack of data evaluating their pharmacodynamic properties.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

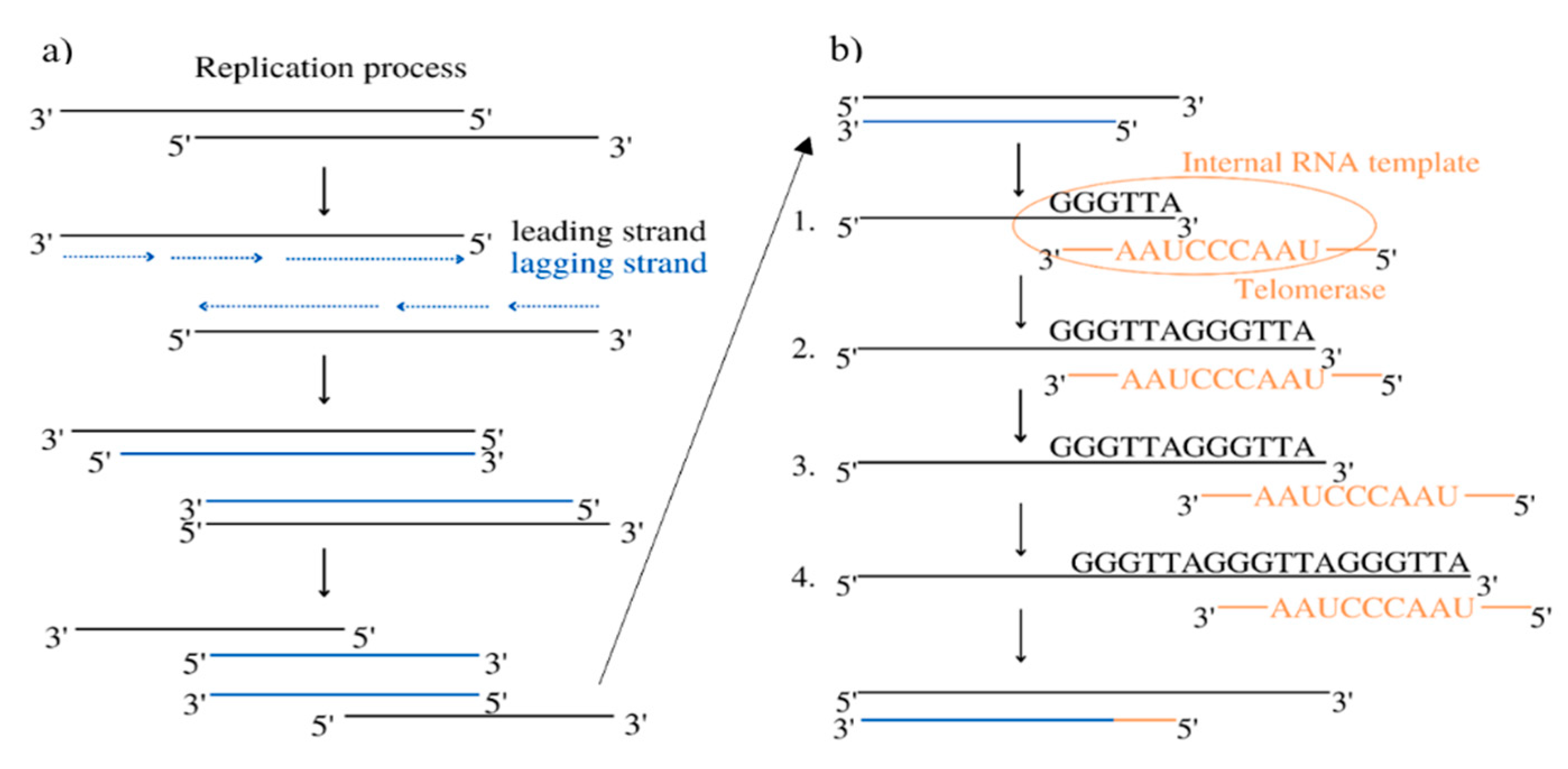

- Zvereva, M.I.; Shcherbakova, D.M.; Dontsova, O.A. Telomerase: Structure, Functions, and Activity Regulation. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2010, 75, 1563–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sušac, L.; Feigon, J. Structural Biology of Telomerase. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dratwa, M.; Wysoczańska, B.; Łacina, P.; Kubik, T.; Bogunia-Kubik, K. TERT—Regulation and Roles in Cancer Formation. Front Immunol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, S.; Rhodes, D. Telomerase Structure. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2014, 25, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, H.; Kumar, R.; Tanwar, P.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Khan, F.; Pandey, P.; Kang, S.; Moon, M.; Choi, J.; Choi, M.; Park, M.N.; Kim, B.; Saeed, M. Unraveling the therapeutic potential of natural products in the prevention and treatment of leukemia. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 160, 114351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.W.; Piatyszek, M.A.; Prowse, K.R.; Harley, C.B.; West, M.D.; Ho, P.L.C.; Coviello, G.M.; Wright, W.E.; Weinrich, S.L.; Shay, J.W. Specific Association of Human Telomerase Activity with Immortal Cells and Cancers. Science (1979) 1994, 266, 2011–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trybek, T.; Kowalik, A.; Góźdź, S.; Kowalska, A. Telomeres and Telomerase in Oncogenesis (Review). Oncol Lett 2020, 20, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesare, A.J.; Reddel, R.R. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres: Models, Mechanisms and Implications. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Telomerase Inhibitors from Natural Products and Their Anticancer Potential. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.-Z.; Qin, Q.-P.; Chen, J.-N.; Chen, Z.-F. Oxoisoaporphine as Potent Telomerase Inhibitor. Molecules 2016, 21, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci Okcanoglu, T.; Avci, C.B.; Yılmaz Süslüer, S.; Kayabasi, C.; Saydam, G.; Gunduz, C. Genistein-Induced Apoptosis Affects Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Activity in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Cyprus Journal of Medical Sciences 2020, 5, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.-M.; Li, H.-B. Natural Polyphenols for Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Nutrients 2016, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee (nee Chakraborty), S.; Ghosh, U.; Bhattacharyya, N.P.; Bhattacharya, R.K.; Dey, S.; Roy, M. Curcumin-Induced Apoptosis in Human Leukemia Cell HL-60 Is Associated with Inhibition of Telomerase Activity. Mol Cell Biochem 2007, 297, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikmen, M.; Canturk, Z.; Ozturk, Y.; Tunali, Y. Investigation of the Apoptotic Effect of Curcumin in Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells by Using Flow Cytometry. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2010, 25, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Ghosh, U.; Bhattacharyya, N.P.; Bhattacharya, R.K.; Roy, M. Inhibition of Telomerase Activity and Induction of Apoptosis by Curcumin in K-562 Cells. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2006, 596, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berletch, J.B.; Liu, C.; Love, W.K.; Andrews, L.G.; Katiyar, S.K.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Epigenetic and Genetic Mechanisms Contribute to Telomerase Inhibition by EGCG. J Cell Biochem 2008, 103, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi-Pirbaluti, M.; Pourgheysari, B.; Shirzad, H.; Motaghi, E.; Askarian Dehkordi, N.; Surani, Z.; Shirzad, M.; Beshkar, P.; Pirayesh, A. Effect of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) on Cell Proliferation Inhibition and Apoptosis Induction in Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cell Line. Journal of HerbMed Pharmacology 2015, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemimehr, N.; Farsinejad, A.; Mirzaee Khalilabadi, R.; Yazdani, Z.; Fatemi, A. The Telomerase Inhibitor MST-312 Synergistically Enhances the Apoptotic Effect of Doxorubicin in Pre-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 106, 1742–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, M.; Tavasoli, B.; Manafi, R.; Kiani, F.; Kashiri, M.; Ebrahimi, S.; Kazemi, A. Indole-3-Carbinol Suppresses NF-ΚB Activity and Stimulates the P53 Pathway in Pre-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells. Tumor Biology 2015, 36, 3919–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, M.; Jafari, L.; Alikarami, F.; Manafi Shabestari, R.; Kazemi, A. Indole-3-Carbinol Induces Apoptosis of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Cells through Suppression of STAT5 and Akt Signaling Pathways. Tumor Biology 2017, 39, 101042831770576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.-O.; Kim, M.-O.; Lee, J.-D.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, G.-Y. Butein Suppresses C-Myc-Dependent Transcription and Akt-Dependent Phosphorylation of HTERT in Human Leukemia Cells. Cancer Lett 2009, 286, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, F.; Avci, C.B.; Gunduz, C.; Sezgin, C.; Simsir, I.Y.; Saydam, G. Gossypol Exerts Its Cytotoxic Effect on HL-60 Leukemic Cell Line via Decreasing Activity of Protein Phosphatase 2A and Interacting with Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Activity. Hematology 2010, 15, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.H.; Walter, M. Combining old and new concepts in targeting telomerase for cancer therapy: transient, immediate, complete and combinatory attack (TICCA). Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carazo, A.; Macáková, K.; Matoušová, K.; Krčmová, L.K.; Protti, M.; Mladěnka, P. Vitamin A Update: Forms, Sources, Kinetics, Detection, Function, Deficiency, Therapeutic Use and Toxicity. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G. The Discovery of the Visual Function of Vitamin A. J Nutr 2001, 131, 1647–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Chen, Z.; You, J.; McNutt, M.A.; Zhang, T.; Han, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gong, E.; Gu, J. All-Trans-Retinoic Acid Induces Cell Growth Arrest in a Human Medulloblastoma Cell Line. J Neurooncol 2007, 84, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Berletch, J.B.; Green, J.G.; Pate, M.S.; Andrews, L.G.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Telomerase Inhibition by Retinoids Precedes Cytodifferentiation of Leukemia Cells and May Contribute to Terminal Differentiation. Mol Cancer Ther 2004, 3, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Gu, J.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Chen, S.-J.; Chen, Z. Mechanisms Ofall-Trans Retinoic Acid-Induced Differentiation of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Cells. J Biosci 2000, 25, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, W.K.; Tyson DeAngelis, J.; Berletch, J.B.; Phipps, S.M.O.; Andrews, L.G.; Brouillette, W.J.; Muccio, D.D.; Tollefsbol, T.O. The Novel Retinoid, 9cUAB30, Inhibits Telomerase and Induces Apoptosis in HL60 Cells. Transl Oncol 2008, 1, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gils, N.; Verhagen, H.J.M.P.; Rutten, A.; Menezes, R.X.; Tsui, M.L.; Vermue, E.; Dekens, E.; Brocco, F.; Denkers, F.; Kessler, F.L.; et al. IGFBP7 Activates Retinoid Acid-Induced Responses in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stem and Progenitor Cells. Blood Adv 2020, 4, 6368–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Thé, H. Differentiation Therapy Revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 2, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, M.; Kantarjian, H.; Ravandi, F. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia Current Treatment Algorithms. Blood Cancer J 2021, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masetti, R.; Vendemini, F.; Zama, D.; Biagi, C.; Gasperini, P.; Pession, A. All-Trans Retinoic Acid in the Treatment of Pediatric Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2012, 12, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutny, M.A.; Todd, ; Alonzo, A.; Abla, O.; Et Al Key Points, ; Assessment of Arsenic Trioxide and All-Trans Retinoic Acid for the Treatment of Pediatric Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group AAML1331 Trial; 2021.

- Farinello, D.; Wozińska, M.; Lenti, E.; Genovese, L.; Bianchessi, S.; Migliori, E.; Sacchetti, N.; di Lillo, A.; Bertilaccio, M.T.S.; de Lalla, C.; et al. A Retinoic Acid-Dependent Stroma-Leukemia Crosstalk Promotes Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Progression. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, Q.T.; Koeffler, H.P. Vitamin D Compounds in Leukemia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2005, 97, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulling, P.M.; Olson, K.C.; Olson, T.L.; Feith, D.J.; Loughran, T.P. Vitamin D in Hematological Disorders and Malignancies. Eur J Haematol 2017, 98, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D: Importance in the Prevention of Cancers, Type 1 Diabetes, Heart Disease, and Osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2004, 79, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christakos, S.; Dhawan, P.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D: Metabolism, Molecular Mechanism of Action, and Pleiotropic Effects. Physiol Rev 2016, 96, 365–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trump, D.L.; Deeb, K.K.; Johnson, C.S. Vitamin D: Considerations in the Continued Development as an Agent for Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Cancer J 2010, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiappan, R.; Shen, Z.; Tse, A.K.-W.; Jinwal, U.; Tang, J.; Lungchukiet, P.; Sun, Y.; Kruk, P.; Nicosia, S. v.; Zhang, X.; et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Suppresses Telomerase Expression and Human Cancer Growth through MicroRNA-498. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 41297–41309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Williams, M.; Newland, A.; Colston, K. Leukemia Cell Differentiation: Cellular and Molecular Interactions of Retinoids and Vitamin D. General Pharmacology: The Vascular System 1999, 32, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisatake, J.; Kubota, T.; Hisatake, Y.; Uskokovic, M.; Tomoyasu, S.; Koeffler, H.P. 5,6-Trans-16-Ene-Vitamin D3: A New Class of Potent Inhibitors of Proliferation of Prostate, Breast, and Myeloid Leukemic Cells. Cancer Res 1999, 59, 4023–4029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delvin, E.; Alos, N.; Rauch, F.; Marcil, V.; Morel, S.; Boisvert, M.; Lecours, M.-A.; Laverdière, C.; Sinnett, D.; Krajinovic, M.; et al. Vitamin D Nutritional Status and Bone Turnover Markers in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Survivors: A PETALE Study. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Xu, Y.; de Necochea-Campion, R.; Baylink, D.J.; Payne, K.J.; Tang, X.; Ratanatharathorn, C.; Ji, Y.; Mirshahidi, S.; Chen, C.-S. Application of Vitamin D and Vitamin D Analogs in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia. Exp Hematol 2017, 50, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Muindi, J.R.; Tan, W.; Hu, Q.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; Wilding, G.E.; Ford, L.A.; Sait, S.N.J.; Block, A.W.; et al. Low 25(OH) Vitamin D3 Levels Are Associated with Adverse Outcome in Newly Diagnosed, Intensively Treated Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer 2014, 120, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, X.; Chelghoum, Y.; Fanari, N.; Cannas, G. Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels Are Associated with Prognosis in Hematological Malignancies. Hematology 2011, 16, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Drake, M.T.; Maurer, M.J.; Allmer, C.; Rabe, K.G.; Slager, S.L.; Weiner, G.J.; Call, T.G.; Link, B.K.; Zent, C.S.; et al. Vitamin D Insufficiency and Prognosis in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2011, 117, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, C.K.; Khanna, S.; Roy, S. Tocotrienols: Vitamin E beyond tocopherols. Life Sci 2006, 18, 2088–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Sundaram, C.; Prasad, S.; Kannappan, R. Tocotrienols, the Vitamin E of the 21st Century: Its Potential against Cancer and Other Chronic Diseases. Biochem Pharmacol 2010, 80, 1613–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, M.G. Vitamin E, Nuclear Receptors and Xenobiotic Metabolism. Arch Biochem Biophys 2004, 423, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem; Zouein; Mohamad; Hodroj; Haykal; Abou Najem; Naim; Rizk The Vitamin E Derivative Gamma Tocotrienol Promotes Anti-Tumor Effects in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cell Lines. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2808. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shvachko, L.P.; Zavelevich, M.P.; Gluzman, D.F.; Kravchuk, I. v; Telegeev, G.D. Vitamin Е Activates Expression of С/EBP Alpha Transcription Factor and G-CSF Receptor in Leukemic K562 Cells. Exp Oncol 2018, 40, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, K.N.; Sheikha, A.; Thanoon, I.A.-J.; Hussein, F.N. Effect of Vitamin E on Chemotherapy Induced Oxidative Stress and Immunoglobulin Levels in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Tikrit Medical Journal 2008, 14, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Telegeev, G.D.; Gluzman, D.F.; Zavelevich, M.P.; Shvachko, L.P. Aberrant Expression of Placental-like Alkaline Phosphatase in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells in Vitro and Its Modulation by Vitamin E. Exp Oncol 2020, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.T.; Buring, J.E.; Mukamal, K.J.; Vinayaga Moorthy, M.; Wayne, P.M.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Battinelli, E.M.; Ridker, P.M.; Sesso, H.D.; Weinstein, S.J.; et al. COMT and Alpha-Tocopherol Effects in Cancer Prevention: Gene-Supplement Interactions in Two Randomized Clinical Trials. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2019, 111, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunn, J.; Theobald, H.E. The Health Effects of Dietary Unsaturated Fatty Acids. Nutr Bull 2006, 31, 178–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitsuka, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Suzuki, T.; Miyazawa, T. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Inhibit Telomerase Activity in DLD-1 Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells: A Dual Mechanism Approach. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2005, 1737, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Yung, B.Y.M. Nucleophosmin/B23 Regulates the Susceptibility of Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells to Sodium Butyrate-Induced Apoptosis and Inhibition of Telomerase Activity. Int J Cancer 1999, 83, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, D.; Huang, K.; Yin, S.; Li, Y.; Xie, S.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J. Synergistic/Additive Interaction of Valproic Acid with Bortezomib on Proliferation and Apoptosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Leuk Lymphoma 2012, 53, 2487–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Yin, S.-M.; Feng, S.-Q.; Nie, D.-N.; Xie, S.-F.; Ma, L.-P.; Wang, X.-J.; Wu, Y.-D. Effect of Valproic Acid on Apoptosis of Leukemia HL-60 Cells and Expression of h-Tert Gene. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2010, 18, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.-N.; Ye, W.-C.; Liu, G.-G.; Hsiao, W.L.W. 23-Hydroxybetulinic Acid-Mediated Apoptosis Is Accompanied by Decreases in Bcl-2 Expression and Telomerase Activity in HL-60 Cells. Life Sci 2002, 72, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODA, M.; UENO, T.; KASAI, N.; TAKAHASHI, H.; YOSHIDA, H.; SUGAWARA, F.; SAKAGUCHI, K.; HAYASHI, H.; MIZUSHINA, Y. Inhibition of Telomerase by Linear-Chain Fatty Acids: A Structural Analysis. Biochemical Journal 2002, 367, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H. Apoptosis of U937 Human Leukemic Cells by Sodium Butyrate Is Associated with Inhibition of Telomerase Activity. Int J Oncol 2006, 29, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahrmann, J.F.; Ballester, O.F.; Ballester, G.; Witte, T.R.; Salazar, A.J.; Kordusky, B.; Cowen, K.G.; Ion, G.; Primerano, D.A.; Boskovic, G.; et al. Inhibition of Nuclear Factor Kappa B Activation in Early-Stage Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia by Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Cancer Invest 2013, 31, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- el Amrousy, D.; El-Afify, D.; Khedr, R.; Ibrahim, A.M. Omega 3 Fatty Acids Can Reduce Early Doxorubicin-induced Cardiotoxicity in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2022, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bükki, J.; Stanga, Z.; Tellez, F.B.; Duclos, K.; Kolev, M.; Krähenmann, P.; Pabst, T.; Iff, S.; Jüni, P. Omega-3 Poly-Unsaturated Fatty Acids for the Prevention of Severe Neutropenic Enterocolitis in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Nutr Cancer 2013, 65, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, T.R.; Borges, D.S.; de Oliveira, P.F.; Mocellin, M.C.; Barbosa, A.M.; Camargo, C.Q.; del Moral, J.Â.G.; Poli, A.; Calder, P.C.; Trindade, E.B.S.M.; et al. Oral Fish Oil Positively Influences Nutritional-Inflammatory Risk in Patients with Haematological Malignancies during Chemotherapy with an Impact on Long-Term Survival: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 2017, 30, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rücker, F.G.; Lang, K.M.; Fütterer, M.; Komarica, V.; Schmid, M.; Döhner, H.; Schlenk, R.F.; Döhner, K.; Knudsen, S.; Bullinger, L. Molecular Dissection of Valproic Acid Effects in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Identifies Predictive Networks. Epigenetics 2016, 11, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, M.T.; Salvi, F.; Perticone, S.; Baraldi, A.; de Paoli, L.; Gatto, S.; Pietrasanta, D.; Pini, M.; Primon, V.; Zallio, F.; et al. Hematologic Improvement and Response in Elderly AML/RAEB Patients Treated with Valproic Acid and Low-Dose Ara-C. Leuk Res 2011, 35, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitsuka, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Igarashi, M.; Miyazawa, T. Telomerase Inhibition by Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol from Edible Purple Laver (Porphyra Yezoensis). Cancer Lett 2004, 212, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.K.; Pradhan, B.S.; Banerjee, S.; Mondal, N.B.; Majumder, S.S.; Bhattacharyya, M.; Chakrabarti, S.; Roychoudhury, S.; Majumder, H.K. Sulfonoquinovosyl Diacylglyceride Selectively Targets Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells and Exerts Potent Anti-Leukemic Effects in Vivo. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dart, D.A.; Adams, K.E.; Akerman, I.; Lakin, N.D. Recruitment of the Cell Cycle Checkpoint Kinase ATR to Chromatin during S-Phase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 16433–16440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.-S.; Shih, Y.-L.; Lee, C.-H.; Hsueh, S.-C.; Liu, J.-Y.; Liao, N.-C.; Chen, Y.-L.; Huang, Y.-P.; Lu, H.-F.; Chung, J.-G. Sulforaphane-Induced Apoptosis in Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells through Extrinsic and Intrinsic Signal Pathways and Altering Associated Genes Expression Assayed by CDNA Microarray. Environ Toxicol 2017, 32, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.-L.; Sun, X.; Huang, L.-B.; Liu, X.-J.; Qin, G.; Wang, L.-N.; Zhang, X.-L.; Ke, Z.-Y.; Luo, J.-S.; Liang, C.; et al. Melatonin Inhibits MLL-Rearranged Leukemia via RBFOX3/HTERT and NF-ΚB/COX-2 Signaling Pathways. Cancer Lett 2019, 443, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Dietary Sources and Bioactivities of Melatonin. Nutrients 2017, 9, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisi, A.; Akbari, G.; Mard, S.A.; Badfar, G.; Zarezade, V.; Mirshekar, M.A. Role of Crocin in Several Cancer Cell Lines: An Updated Review. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2020, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.-Z.; Zang, C.; Sun, L.-R. The Effect and Mechanisms of Proliferative Inhibition of Crocin on Human Leukaemia Jurkat Cells. West Indian Medical Journal 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.H.; Lee, T.-J.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.-H.; Park, J.-W.; Kwon, T.K. Induction of Apoptosis by Withaferin A in Human Leukemia U937 Cells through Down-Regulation of Akt Phosphorylation. Apoptosis 2008, 13, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Katiyar, S.P.; Sundar, D.; Kaul, Z.; Miyako, E.; Zhang, Z.; Kaul, S.C.; Reddel, R.R.; Wadhwa, R. Withaferin-A Kills Cancer Cells with and without Telomerase: Chemical, Computational and Experimental Evidences. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e2755–e2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khathayer, F.; Ray, S.K. Diosgenin as a Novel Alternative Therapy for Inhibition of Growth, Invasion, and Angiogenesis Abilities of Different Glioblastoma Cell Lines. Neurochem Res 2020, 45, 2336–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semwal, P.; Painuli, S.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Rauf, A.; Sharma, A.; Daştan, S.D.; Kumar, M.; Alshehri, M.M.; Taheri, Y.; Das, R.; et al. Diosgenin: An Updated Pharmacological Review and Therapeutic Perspectives. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Fan, J.; Wang, Q.; Ju, D.; Feng, M.; Li, J.; Guan, Z.; An, D.; Wang, X.; Ye, L. Diosgenin Induces ROS-Dependent Autophagy and Cytotoxicity via MTOR Signaling Pathway in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, N. A review on analytical methods for natural berberine alkaloids. J Sep Sci 2019, 9, 1794–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Hao, J.; Fan, D. Biological Properties and Clinical Applications of Berberine. Front Med 2020, 14, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.L.; Hsu, C.Y.; Liu, W.H.; Yung, B.Y.M. Berberine-Induced Apoptosis of Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells Is Associated with down-Regulation of Nucleophosmin/B23 and Telomerase Activity. Int J Cancer 1999, 81, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschin, M.; Rossetti, L.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Schirripa, S.; Bianco, A.; Ortaggi, G.; Savino, M.; Schultes, C.; Neidle, S. Natural and Synthetic G-Quadruplex Interactive Berberine Derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2006, 16, 1707–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kręgiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.; Novellino, E.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasooriya, R.G.P.T.; Kang, S.H.; Kang, C.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Moon, D.O.; Hyun, J.W.; Chang, W.Y.; Kim, G.Y. Apigenin Decreases Cell Viability and Telomerase Activity in Human Leukemia Cell Lines. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2012, 50, 2605–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, S.A.; Elkhalifa, A.E.O.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Patel, M.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Snoussi, M.; Ashraf, M.S.; Adnan, M.; Hadi, S. Cordycepin for Health and Wellbeing: A Potent Bioactive Metabolite of an Entomopathogenic Medicinal Fungus Cordyceps with Its Nutraceutical and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2020, 25, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.J.; Kwon, G.S.; Jeong, J.W.; Kim, C.H.; Yoon, H.M.; Kim, G.Y.; Shim, J.H.; Moon, S.K.; Kim, W.J.; Choi, Y.H. Cordyceptin Induces Apoptosis through Repressing HTERT Expression and Inducing Extranuclear Export of HTERT. J Biosci Bioeng 2015, 119, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Khan, F.B.; Safdari, H.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Alzohairy, M.A.; Safdari, M.; Amirizadeh, M.; Rehman, S.; Equbal, M.J.; Hoque, M. Prospective Therapeutic Potential of Tanshinone IIA: An Updated Overview. Pharmacol Res 2021, 164, 105364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, T.L.; Su, C.C. Tanshinone IIA induces apoptosis in human lung cancer A549 cells through the induction of reactive oxygen species and decreasing the mitochondrial membrane potential. Int J Mol Med 2010, 25, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Jin, L.; Deng, H.; Wu, D.; Shen, Q. K.; Quan, Z. S.; Zhang, C. H.; & Guo, H. Y. (2022). Research and Development of Natural Product Tanshinone I: Pharmacology, Total Synthesis, and Structure Modifications. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 920411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Fan, R.F.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.Z.; Fang, Z.G.; Guan, W.B.; Lin, D.J.; Xiao, R.Z.; Huang, R.W.; Huang, H.Q.; et al. Down-Regulation of Telomerase Activity and Activation of Caspase-3 Are Responsible for Tanshinone I-Induced Apoptosis in Monocyte Leukemia Cells in Vitro. Int J Mol Sci 2010, 11, 2267–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. The Role of Rapamycin in Healthspan Extension via the Delay of Organ Aging. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 70, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vézina, C.; Kudelski, A.; Sehgal, S.N. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975, 10, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.M.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, Y.; Lai, X.Y.; Huang, H. Antiproliferative Effect of Rapamycin on Human T-Cell Leukemia Cell Line Jurkat by Cell Cycle Arrest and Telomerase Inhibition. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2008, 29, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomizawa, A.; Kanno, S.I.; Osanai, Y.; Yomogida, S.; Ishikawa, M. Cytotoxic effects of caffeic acid undecyl ester are involved in the inhibition of telomerase activity in NALM-6 human B-cell leukemia cells. Oncol Lett 2013, 4, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomizawa, A.; Kanno, S.I.; Osanai, Y.; Goto, A.; Sato, C.; Yomogida, S.; Ishikawa, M. Induction of apoptosis by a potent caffeic acid derivative, caffeic acid undecyl ester, is mediated by mitochondrial damage in NALM-6 human B cell leukemia cells. Oncol Rep 2013, 2, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feriotto, G.; Tagliati, F.; Giriolo, R.; Casciano, F.; Tabolacci, C.; Beninati, S.; Khan, M.T.H.; Mischiati, C. Caffeic Acid Enhances the Anti-Leukemic Effect of Imatinib on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells and Triggers Apoptosis in Cells Sensitive and Resistant to Imatinib. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.L.; de Albuquerque Wanderley Sales, V.; Gomes de Melo, C.; Ferreira da Silva, R.M.; Vicente Nishimura, R.H.; Rolim, L.A.; Rolim Neto, P.J. Beta-Lapachone: Natural Occurrence, Physicochemical Properties, Biological Activities, Toxicity and Synthesis. Phytochemistry 2021, 186, 112713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, D.-O.; Kang, C.-H.; Kim, M.-O.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Lee, J.-D.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, G.-Y. β-Lapachone (LAPA) Decreases Cell Viability and Telomerase Activity in Leukemia Cells: Suppression of Telomerase Activity by LAPA. J Med Food 2010, 13, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J. Ginsenoside Rg1 Induces Senescence of Leukemic Stem Cells by Upregulating P16INK4a and Downregulating HTERT Expression. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2021, 30, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.E.; Park, C.; Kim, S.H.; Hossain, M.A.; Kim, M.Y.; Chung, H.Y.; Son, W.S.; Kim, G.-Y.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, N.D. Korean Red Ginseng Extract Induces Apoptosis and Decreases Telomerase Activity in Human Leukemia Cells. J Ethnopharmacol 2009, 121, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Chu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, N. Hepataprotective Effects of Ginsenoside Rg1 – A Review. J Ethnopharmacol 2017, 206, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Shang, W.; Xue, J.; Chen, R.; Xing, Y.; Song, D.; Xu, R. Ginsenoside Rg1 Promotes Cerebral Angiogenesis via the PI3K/Akt/MTOR Signaling Pathway in Ischemic Mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2019, 856, 172418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Jiao, D.; Xu, H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, T.; Liang, Q. Ginsenoside Rg1 Promotes Lymphatic Drainage and Improves Chronic Inflammatory Arthritis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2020, 20, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, Z.; Shen, F.; Xie, P.; Wang, J.; Zhu, A.; Zhu, G. Ginsenoside Rg1 Prevents PTSD-Like Behaviors in Mice Through Promoting Synaptic Proteins, Reducing Kir4.1 and TNF-α in the Hippocampus. Mol Neurobiol 2021, 58, 1550–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Gupta, S.; Halder, B.; Gomes, A.; Gomes, A. Bengalin Initiates Autophagic Cell Death through ERK–MAPK Pathway Following Suppression of Apoptosis in Human Leukemic U937 Cells. Life Sci 2013, 93, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S.; das Gupta, S.; Gomes, A.; Giri, B.; Dasgupta, S.C.; Biswas, A.; Mishra, R.; Gomes, A. A High Molecular Weight Protein Bengalin from the Indian Black Scorpion (Heterometrus Bengalensis C.L. Koch) Venom Having Antiosteoporosis Activity in Female Albino Rats. Toxicon 2010, 55, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. das; Gomes, A.; Debnath, A.; Saha, A.; Gomes, A. Apoptosis Induction in Human Leukemic Cells by a Novel Protein Bengalin, Isolated from Indian Black Scorpion Venom: Through Mitochondrial Pathway and Inhibition of Heat Shock Proteins. Chem Biol Interact 2010, 183, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2000; Vol. chapter 3, ISBN 978-0-309-06935-9.

- Travica, N.; Ried, K.; Sali, A.; Scholey, A.; Hudson, I.; Pipingas, A. Vitamin C Status and Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Guo, C.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Su, M. Functional Benefit and Molecular Mechanism of Vitamin C against Perfluorooctanesulfonate-Associated Leukemia. Chemosphere 2021, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.-J.; Zou, X.-L.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Ni, X.; Wei, J. Effect of High Dose Vitamin C on Proliferation and Apoptosis of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2020, 28, 833–841. [Google Scholar]

- Shin-ya, K. Telomerase Inhibitor, Telomestatin, a Specific Mechanism to Interact with Telomere Structure. Nihon Rinsho 2004, 62, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tauchi, T.; Shin-ya, K.; Sashida, G.; Sumi, M.; Okabe, S.; Ohyashiki, J.H.; Ohyashiki, K. Telomerase Inhibition with a Novel G-Quadruplex-Interactive Agent, Telomestatin: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies in Acute Leukemia. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5719–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C.S.; Holečková, V.; Petrásková, L.; Biedermann, D.; Valentová, K.; Buchta, M.; Křen, V. The Silymarin Composition… and Why Does It Matter??? Food Research International 2017, 100, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faezizadeh, Z.; Mesbah-Namin, S.A.; Allameh, A. The effect of silymarin on telomerase activity in the human leukemia cell line K562. Planta Med 2012, 9, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Qin, X.; Yuan, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Jin, Y.; Zeng, G.; Yen, L.; Hu, J.; Dang, T.; et al. Effect of Tianshengyuan-1 (TSY-1) on Telomerase Activity and Hematopoietic Recovery - in Vitro, Ex Vivo, and in Vivo Studies. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014, 7, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Qin, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y.; Santiskulvong, C.; Vu, V.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Z.; Chow, M.; Rao, J. Tianshengyuan-1 (TSY-1) Regulates Cellular Telomerase Activity by Methylation of TERT Promoter. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 7977–7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, D.L.; Ngau, T.H.; Nguyen, N.H.; Tran, G.-B.; Nguyen, C.T. Potential Therapeutic and Pharmacological Effects of Wogonin: An Updated Review. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 9779–9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.M.; Haseeb, A.; Ansari, M.Y.; Devarapalli, P.; Haynie, S.; Haqqi, T.M. Wogonin, a Plant Derived Small Molecule, Exerts Potent Anti-Inflammatory and Chondroprotective Effects through the Activation of ROS/ERK/Nrf2 Signaling Pathways in Human Osteoarthritis Chondrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 2017, 106, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.T.; Wang, C.Y.; Yang, R.C.; Chu, C.J.; Wu, H.T.; Pang, J.H.S. Wogonin, an Active Compound in Scutellaria Baicalensis, Induces Apoptosis and Reduces Telomerase Activity in the HL-60 Leukemia Cells. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiladjian, J.-J.; Giraudier, S.; Cassinat, B. Interferon-Alpha for the Therapy of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Targeting the Malignant Clone. Leukemia 2016, 30, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonsson, B.; Hjorth-Hansen, H.; Weis Bjerrum, O.; Porkka, K. Interferon Alpha for Treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Curr Drug Targets 2011, 12, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, X.-H.; Kong, J.; Wang, J.; Jia, J.-S.; Lu, S.-Y.; Gong, L.-Z.; Zhao, X.-S.; Jiang, Q.; Chang, Y.-J.; et al. Interferon-α as Maintenance Therapy Can Significantly Reduce Relapse in Patients with Favorable-Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2021, 62, 2949–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magenau, J.M.; Peltier, D.; Riwes, M.; Pawarode, A.; Parkin, B.; Braun, T.; Anand, S.; Ghosh, M.; Maciejewski, J.; Yanik, G.; et al. Type 1 Interferon to Prevent Leukemia Relapse after Allogeneic Transplantation. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 5047–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nai, J.; Zhang, C.; Shao, H.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Gao, L.; Dai, M.; Zhu, L.; Sheng, H. Extraction, Structure, Pharmacological Activities and Drug Carrier Applications of Angelica Sinensis Polysaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 183, 2337–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, C.Y.; Cai, S.Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, R.; Wang, Y.P. Senescence Effects of Angelica Sinensis Polysaccharides on Human Acute Myelogenous Leukemia Stem and Progenitor Cells. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2013, 14, 6549–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, G.; Tangen, J.-M.; Mahmood, F.; Mirlashari, M.R.; Nissen-Meyer, L.S.H.; Nentwich, I.; Therkelsen, S.P.; Tjønnfjord, G.E.; Johnson, E. Antitumor, Anti-Inflammatory and Antiallergic Effects of Agaricus Blazei Mushroom Extract and the Related Medicinal Basidiomycetes Mushrooms, Hericium Erinaceus and Grifola Frondosa: A Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dbass, A.M.; Al- Daihan, S.K.; Bhat, R.S. Agaricus Blazei Murill as an Efficient Hepatoprotective and Antioxidant Agent against CCl4-Induced Liver Injury in Rats. Saudi J Biol Sci 2012, 19, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Tian, N.; Wang, H.; Yan, H. Chemically Sulfated Polysaccharides from Agaricus Blazei Murill: Synthesis, Characterization and Anti-HIV Activity. Chem Biodivers 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Xi, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Primary mechanism of apoptosis induction in a leukemia cell line by fraction FA-2-b-ss prepared from the mushroom Agaricus blazei Murill. Braz J Med Biol Res 2007, 40, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.O.; Moon, D.O.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, J.D.; Kim, N.D.; Kim, G.Y. Platycodin D induces mitotic arrest in vitro, leading to endoreduplication, inhibition of proliferation and apoptosis in leukemia cells. Int J Cancer 2008, 122, 2674–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.O.; Moon, D.O.; Choi, Y.H.; Shin, D.Y.; Kang, H.S.; Choi, B.T.; Lee, J.D.; Li, W.; Kim, G.Y. Platycodin D Induces Apoptosis and Decreases Telomerase Activity in Human Leukemia Cells. Cancer Lett 2008, 261, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.O.; Moon, D.O.; Kang, S.H.; Heo, M.S.; Choi, Y.H.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, J.D.; Kim, G.Y. Pectenotoxin-2 Represses Telomerase Activity in Human Leukemia Cells through Suppression of HTERT Gene Expression and Akt-Dependent HTERT Phosphorylation. FEBS Lett 2008, 582, 3263–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaiwa, N.; Maarouf, N.R.; Darwish, M.H.; Alhamad, D.W.M.; Sebastian, A.; Hamad, M.; Omar, H.A.; Orive, G.; Al-Tel, T.H. Camptothecin’s Journey from Discovery to WHO Essential Medicine: Fifty Years of Promise. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 223, 113639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazareva, N.F.; Baryshok, V.P.; Lazarev, I.M. Silicon-Containing Analogs of Camptothecin as Anticancer Agents. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2018, 351, 1700297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.F.; Liu, W.J.; Ding, J. Regulation of Telomerase Activity in Camptothecin-Induced Apoptosis of Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2000, 21, 759–764. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.; Dai, S.-M. A Chinese Herb Tripterygium Wilfordii Hook F in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Mechanism, Efficacy, and Safety. Rheumatol Int 2011, 31, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Z.; Qin, W.; Zheng, H.; Schegg, K.; Han, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; McSwiggin, H.; Peng, H.; et al. Triptonide Is a Reversible Non-Hormonal Male Contraceptive Agent in Mice and Non-Human Primates. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Tan, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, P.; Lv, C.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, Z. Triptonide Inhibits Lung Cancer Cell Tumorigenicity by Selectively Attenuating the Shh-Gli1 Signaling Pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2019, 365, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Meng, M.; Liu, Y.; Qi, J.; Zhao, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, P.; et al. Triptonide Effectively Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Metastasis through Concurrent Degradation of Twist1 and Notch1 Oncoproteins. Breast Cancer Research 2021, 23, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Niu, X.; Jin, R.; Xu, F.; Ding, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z. Triptonide Inhibits Metastasis Potential of Thyroid Cancer Cells via Astrocyte Elevated Gene-1. Transl Cancer Res 2020, 9, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Meng, M.; Zheng, N.; Cao, Z.; Yang, P.; Xi, X.; Zhou, Q. Targeting of Multiple Senescence-Promoting Genes and Signaling Pathways by Triptonide Induces Complete Senescence of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2017, 126, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, S.; Kitajima, Y.; Kakuta, M.; Osanai, Y.; Kurauchi, K.; Ujibe, M.; Ishikawa, M. Costunolide-Induced Apoptosis Is Caused by Receptor-Mediated Pathway and Inhibition of Telomerase Activity in NALM-6 Cells. Biol Pharm Bull 2008, 31, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-J.; Jiang, J.-F.; Xiao, D.; Ding, J. Down-Regulation of Telomerase Activity via Protein Phosphatase 2A Activation in Salvicine-Induced Human Leukemia HL-60 Cell Apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol 2002, 64, 1677–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.N.; Ye, W.C.; Rui, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, G.Q. Patensin-Induced Apoptosis Is Accompanied by Decreased Bcl-2 Expression and Telomerase Activity in HL-60 Cells. J Asian Nat Prod Res 2004, 6, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, N.D.; Choi, Y.H. Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 and Telomerase Activities in Human Leukemia Cells by Dideoxypetrosynol A, a Polyacetylene from the Marine Sponge Petrosia Sp. Int J Oncol 2007, 30, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, W. il; Hong, S.H.; Park, D. il; Kim, N.D.; Bae, S.J.; Jung, J.H.; Choi, Y.H. Induction of Apoptosis by (Z)-Stellettic Acid C, an Acetylenic Acid from the Sponge Stelletta Sp., Is Associated with Inhibition of Telomerase Activity in Human Leukemic U937 Cells. Chemotherapy 2007, 53, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, H.J.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, B.T.; Park, Y.-M.; Choi, Y.H. Induction of Apoptosis and Inhibition of Telomerase Activity by Trichostatin A, a Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, in Human Leukemic U937 Cells. Exp Mol Pathol 2007, 82, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.-Z.; Lin, M.-F.; Huang, H.; Cai, Z. Homoharringtonine-Induced Apoptosis of Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells Is Associated with Down-Regulation of Telomerase. Am J Chin Med (Gard City N Y) 2006, 34, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, J.; Wang, H.; Song, G.; Guo, Q.; Tian, J.; Han, Y.; Liao, Q.; Liu, G.; et al. The Downregulation of C-Myc and Its Target Gene HTERT Is Associated with the Antiproliferative Effects of Baicalin on HL-60 Cells. Oncol Lett 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogulu, O.; Biray, C.; Gunduz, C.; Karaca, E.; Aksoylar, S.; Sorkun, K.; Salih, B.; Ozkinay, F. Effects of Manisa Propolis on Telomerase Activity in Leukemia Cells Obtained from the Bone Marrow of Leukemia Patients. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2009, 60, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunduz, C.; Biray, C.; Kosova, B.; Yilmaz, B.; Eroglu, Z.; Şahin, F.; Omay, S.B.; Cogulu, O. Evaluation of Manisa Propolis Effect on Leukemia Cell Line by Telomerase Activity. Leuk Res 2005, 29, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogawa, K.; Yamada, T.; Sumida, T.; Hamakawa, H.; Kuwabara, H.; Matsuda, M.; Muramatsu, Y.; Kose, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Sasaki, Y.; et al. Induction of Apoptosis and Inhibition of DNA Topoisomerase-I in K-562 Cells by a Marine Microalgal Polysaccharide. Life Sci 2000, 66, PL227–PL231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogawa, K.; Sumida, T.; Hamakawa, H.; Yamada, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Matsuda, M.; Oda, H.; Miyake, H.; Tashiro, S.; Okutani, K. Inhibitory Effect of a Marine Microalgal Polysaccharide on the Telomerase Activity in K562 Cells.

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.-T.; Ma, W.; Xie, X.; Huang, Q. Oridonin: A Review of Its Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-J.; Wu, X.-Y.; Lul, H.-L.; Pan, X.-L.; Peng, J.; Huang, R.-W. Anti-Proliferation Effect of Oridonin on HL-60 Cells and Its Mechanism. Chin Med Sci J 2004, 19, 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J.; Huang, R.W.; Lin, D.J.; Wu, X.Y.; Peng, J.; Pan, X.L.; Song, Y.Q.; Lin, Q.; Hou, M.; Wang, D.N.; et al. Oridonin-Induced Apoptosis in Leukemia K562 Cells and Its Mechanism. Neoplasma 2005, 52, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-J.; Huang, R.-W.; Lin, D.-J.; Wu, X.-Y.; Peng, J.; Pan, X.-L.; Lin, Q.; Hou, M.; Zhang, M.-H.; Chen, F. Antiproliferation Effects of Oridonin on HPB-ALL Cells and Its Mechanisms of Action. Am J Hematol 2006, 81, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faa, G.; Gerosa, C.; Fanni, D.; Lachowicz, J.I.; Nurchi, V.M. Gold - Old Drug with New Potentials. Curr Med Chem 2018, 25, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Pandit, S.; Mokkapati, V.R.S.S.; Garg, A.; Ravikumar, V.; Mijakovic, I. Gold Nanoparticles in Diagnostics and Therapeutics for Human Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, E.E.; Mwamuka, J.; Gole, A.; Murphy, C.J.; Wyatt, M.D. Gold Nanoparticles Are Taken Up by Human Cells but Do Not Cause Acute Cytotoxicity. Small 2005, 1, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chinnathambi, A.; Nasif, O.; Alharbi, S.A. Green Synthesis and Chemical Characterization of a Novel Anti-Human Pancreatic Cancer Supplement by Silver Nanoparticles Containing Zingiber Officinale Leaf Aqueous Extract. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2021, 14, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phenix, C.P.; Togtema, M.; Pichardo, S.; Zehbe, I.; Curiel, L. High Intensity Focused Ultrasound Technology, Its Scope and Applications in Therapy and Drug Delivery. J Pharm Pharm Sci 2014, 17, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelstein, D.R.; Ye, J.; Schibber, E.F.; Roychoudhury, A.; Martinez, L.T.; Fekrazad, M.H.; Ortiz, M.; Lee, P.P.; Shapiro, M.G.; Gharib, M. Selective Ablation of Cancer Cells with Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound. Appl Phys Lett 2020, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.-H.; Wu, D.-P.; Jin, J.; Li, J.-Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.-X.; Jiang, H.; Chen, S.-J.; Huang, X.-J. Oral Tetra-Arsenic Tetra-Sulfide Formula Versus Intravenous Arsenic Trioxide As First-Line Treatment of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2013, 31, 4215–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testi, A.M. GIMEMA-AIEOPAIDA Protocol for the Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) in Children. Blood 2005, 106, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, J.G.; Kim, E.S.; Park, W.H.; Jung, C.W.; Kim, B.K.; Lee, Y.Y. Telomerase Activity in Acute Myelogenous Leukaemia: Clinical and Biological Implications. Br J Haematol 1998, 100, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewison, M.; Barker, S.; Brennan, A.; Nathan, J.; Katz, D.R.; O’Riordan, J.L. Autocrine Regulation of 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol Metabolism in Myelomonocytic Cells. Immunology 1989, 68, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, D.; Campa, E.; Dellacasa, C.; Campana, S.; Foli, C.; Boccadoro, M. Differentiating Agents + Low-Dose Chemotherapy in the Management of Old/Poor Prognosis Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia or Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Haematologica 2004, 89, 619–620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paubelle, E.; Zylbersztejn, F.; Alkhaeir, S.; Suarez, F.; Callens, C.; Dussiot, M.; Isnard, F.; Rubio, M.-T.; Damaj, G.; Gorin, N.-C.; et al. Deferasirox and Vitamin D Improves Overall Survival in Elderly Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia after Demethylating Agents Failure. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shvachko, L.; Zavelevich, M.; Gluzman, D.; Telegeev, G. (2021) Vitamin E in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) Prevention. Vitamin E in Health and Disease - Interactions, Diseases and Health Aspects. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).