% Current affiliation: Department of Gynecology, Obstetrics and Gynecological Endocrinology, Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Austria

& Current affiliation: John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Miami, Florida

§ Current affiliation: Department of Structural and Computational Biology, Max Perutz Labs, Campus Vienna Biocenter 5, 1030 Vienna, Austria.

1. Introduction

Driver mutations promote their own propagation, notably observed in cancer cells [

1,

2,

3]. These mutations are well-characterized in genes within the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-Ras signaling pathway and its downstream branches with an impact on cell survival or differentiation [

4]. Similarly, a handful of driver mutations which affect the RTK-Ras signaling pathway have been described in the male germline. These

de novo mutations (DNMs) are rare, but when they occur, they lead to sub-clonal expansion events of the mutation within the testis over time [

5]. The mutant proteins have oncogenic-like properties and a strong correlation between disease prevalence and paternal age has been documented with fathers being significantly older than population average [

6,

7], a phenomenon known as the paternal age-effect (PAE) [

8]. To date, the best characterized congenital disorders associated with PAE-effect are Apert syndrome, Crouzon, Pfeiffer, Costello and Noonan syndromes, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B (MEN2B), Muenke craniosynostosis, hypochondroplasia (HCH), and achondroplasia (ACH) [

6,

7,

9,

10,

11]. The underlying pathogenic driver mutations are exclusive to the male germline and encode missense substitutions with gain-of-function properties; reviewed in [

12,

13,

14]. Given that these mutations are significant contributors to human diseases, understanding their origins and the factors influencing their occurrence, as well as their recurrence in siblings, is crucial.

In an effort to understand the molecular and biological mechanisms underlying PAE-mutations and their expansion in the ageing male germline, studies assessing mutation frequencies for several PAE disorders have been conducted in sperm and testis over the last decades [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In sperm DNA from donors of varying ages, the frequencies of mutations causing Apert syndrome and ACH showed an increase with age [

16,

17,

18]. Further, the examination of post-mortem testes of older donors found a localized enrichment in small regions of the testis of PAE-mutations in genes such

as FGFR2, FGFR3, RET, HRAS, PTPN11, KRAS, BRAF, CBL, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, RAF1, and

SOS1 [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]

This selective advantage is likely the result of changes in the RTK-Ras signaling pathway caused by an hyperactivation of the RTK signaling by the mutant protein in the male germline. Under physiological conditions the activation of RTKs like the FGFR3 depends on growth factor (ligand) binding to the extracellular receptor domains. The conformational changes elicited by this ligand binding are transmitted inside the cell by a rearrangement of the transmembrane helices creating a receptor dimer (or multimer) that triggers the autophosphorylation of the intracellular kinase domain within its activation loop, which in turn is recognized by downstream effector proteins (e.g. GRB2) via their phospho-peptide binding domains. This tightly orchestrated cascade of events ensures specific, high fidelity signal transduction; hence its corruption causes deregulation and disease [

27].

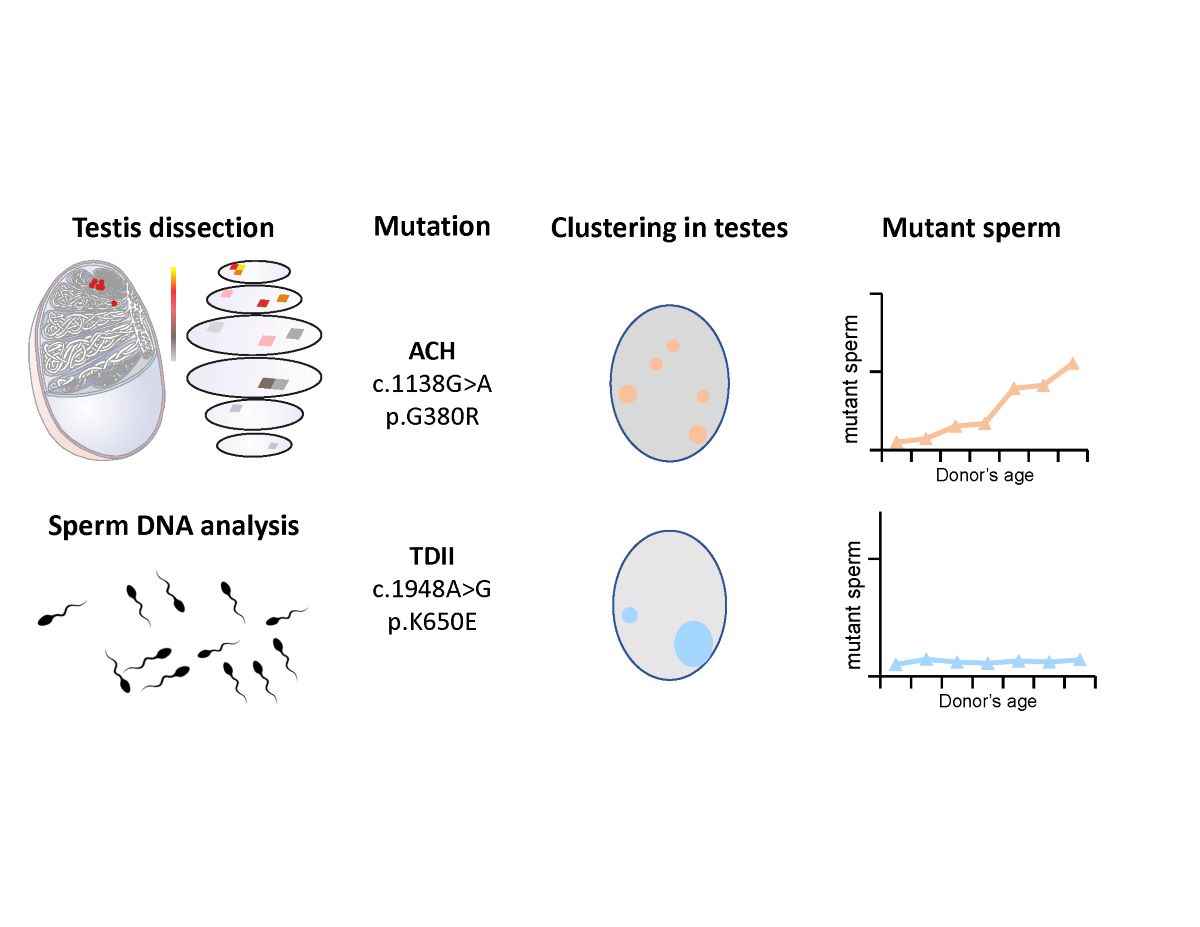

It has been hypothesized that this signal hyperactivation in RTKs induces a modified division pattern in the sexually mature testis. Actively dividing spermatogonia A (SrAp) normally divide asymmetrically, resulting in an undifferentiated daughter cell and a cell that differentiates into sperm. In contrast, mutant SrAp occasionally might divide symmetrically, resulting in two daughter stem cells and a progressive clonal expansion of mutant germ cells that stay in close proximity. This can lead to a relative enrichment of mutant spermatogonia in the testis (sub-clonal expansion) or sperm equivalents, explaining the high mutation frequencies with older age [

20,

21,

24,

25,

26]. A handful of mutations associated with various syndromes, such as Apert syndrome [

20,

21,

23,

24], Noonan syndrome [

22,

23,

26], MEN2B [

21], thanatophoric dysplasia I and II (TDI and TDII) [

28], ACH [

25], Pfeiffer syndrome [

23,

28], HCH, Crouzon, MEN2A, and Beare-Stevenson syndromes [

23], exhibited larger clusters in testes of older donors. Conversely, young individuals (<24 years) showed minimal or no mutational clusters for Apert and Noonan syndrome, supporting the notion that clusters develop during the adult phase of male spermatogenesis, progressively growing over time [

20,

21].

However, there is limited data assessing both testis expansion patterns and sperm mutation frequencies to test the universality of the hypothesis that sub-clonal expansions in the ageing testis also result in a higher number of sperm and a higher transmission risk. Given the extensive role of RTK signaling in many developmental processes, it is likely that the biology and expansion patterns of PAE-mutations might be more complex than assumed and not just the result of a selective advantage gained by SSC, but rather the interplay of several biological mechanisms affecting spermatogenesis all the way to fertilization; with some effects maybe being antagonistic. Particularly, highly activating, gain-of function mutations in FGFR3 could influence the differentiation pathway of spermiogenesis including meiosis and have different effects in different cell-types or developmental stages.

To further examine this hypothesis, we characterized two different mutations in

FGFR3, which are causative for congenital disorders of different severity (ACH and TDII). Both mutations uncouple FGFR3 signaling from ligand binding: c.1138G>A (p.G380R a variant in the transmembrane helix and c.1948A>G (K650E) that mimics activation in the kinase loop. Specifically, we examined the occurrence of these two variants in sperm samples from donors of various age groups and in an aged testis. Together with recent quantitative data comparing the signaling changes at the cell membrane of the two mutant proteins [

29], we observed that the TDII mutation strongly expanded in the ageing testis, but occurrence of the TDII mutation compared to the ACH mutation was reduced in sperm.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Testis, Sperm, and Control DNA.

Snap-frozen, post-mortem testis was obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI, Philadelphia, PA) from a 68-year-old donor free of a history of tobacco, alcohol, and drug use. The time of death after procurement was maximum 6 hours. The donor did not have a history of cancer, chemotherapy and radiation. Human genomic DNA (NA08859) encoding the FGFR3 c.1138G>A mutation was purchased from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ). A DNA sample heterozygous for the FGFR3 c.1948A>G mutation was kindly provided by the Greenwood Genetic Center, South Carolina. Testis and sperm samples were collected from anonymous donors and complied with the ethical regulations for collection of human samples approved by the ethics commission of Upper Austria F-1-11.

A 1887 bp region of FGRF3 was amplified from 10 ng of human genomic DNA in a 50 µl reaction containing 0.5 µM of each primer F-ACH-88bp, and R-TDII-BA, 1x Phusion HF Buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific), 0.1 U Phusion Hot Start II High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific), and 0.2 mM dNTPs. The reaction was carried out with an initial heating step of 98 °C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles at 98 °C for 15 sec, 68 °C for 15 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec. The 3’ A overhangs were added with 1U of OneTaq to a 15 µl reaction volume that was incubated at 72°C for 10 min. The purified amplicon was cloned into a PCR2.1 vector using the TA-Cloning Kit (Invitrogen) and transformed into XL1-blue competent cells. The plasmid was extracted with a standard plasmid extraction protocol detailed in [

30]. In short, cells were pelleted, resuspended and lysed with an alkaline, detergent solution and the DNA was obtained by acetate/ethanol precipitation.

E. coli DNA. XL1 E. coli blue cells were grown in 15ml LB-medium overnight at 37°C until reaching an OD600 of two. A 3ml cell suspension was then centrifuged at 8000g for 30 sec and the cells were resuspended in the 10% leftover supernatant before adding 600µl cell lysis solution (Gentra Puregene Cell Kit), 24µl 1M DTT, and 2µl proteinase K (QIAGEN 20mg/ml) and incubated overnight at 37°C. RNase treatment was performed by adding 3µl of a 4mg/ml RNase A solution and incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was put on ice for ~15 minutes and 200 µl of protein precipitation solution was added snipping the tube vigorously for 1 minute, followed by two consecutive centrifugation steps at 13,000g for 20 min. The DNA was pelleted by adding 600µl of isopropanol and 1 µL of glycogen solution to the supernatant. At this step a visible DNA bundle was formed when mixing gently. Then, the reaction was centrifuged for 30min at 13,000g, and the pellet was washed with 600µl 70% ethanol and left to dry for 3 minutes. The DNA was resuspended in TE 7.5 (50µl) overnight.

2.2. Testis and Sperm DNA Extraction

Testis DNA extraction was carried out as described previously [

30]. In brief, for each individual testis piece using the NucleoMag Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel, #744300.1) according to manufacturer’s condition except for a few modifications that insured a mild extraction and avoided high temperatures to reduce potential sources of DNA lesions. In brief, up to approximately 20mg of tissue was transferred into a round bottom tube and 100µl of Buffer T1 and a 5mm steel bead (QIAGEN, #69989) were was added. The tissue was homogenized in the TissueLyser (QIAGEN) at 25Hz for 1 minute and then briefly spun down. The steel bead was carefully removed and 100µl of Buffer T1 and 25µl Proteinase K solution (75mg/2.6mL) were added and mixed. The samples were incubated at 37ºC overnight. The lysed samples were then centrifuged at 6,000g for 5 minutes and 225µl of the cleared lysate were transferred into a low-binding DNA and RNA-free tube. Next, 24µl of NucleoMag B-Beads and 360µl Buffer MB2 were transferred and resuspended multiple times and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. The beads were isolated by placing the tube in the magnetic separator for 2 minutes and the supernatant was discarded. 600µl of Buffer MB3 were then transferred and the beads were resuspended in this solution, followed by an isolation step in the magnetic separator for another 2 minutes. The supernatant was discarded and the beads were resuspended in 600µl of Buffer MB4. The solution was placed in the magnetic separator and the supernatant was discarded. 900µl of Buffer MB5 were added to the beads and incubated for 45-60 seconds while on the magnetic separator. The supernatant was then discarded and the beads were resuspended with 50µl of Buffer MB6. Following an incubation step at room temperature for 10-20 minutes, the beads were isolated in the magnetic separator and the supernatant containing the genomic DNA was transferred into a low-binding nucleic acid-free tube.

Puregene Core Kit A (QIAGEN, #1042601) was used to extract genomic DNA from sperm samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions with small alterations as described previously in [

30]. Briefly, 25µl of each sample (∼10

6 sperm cells) were centrifuged at 8,000g for 20 seconds and 90% of the supernatant was discarded. The remaining 10% were resuspended and 150µl of cell lysis solution, 6µl of 1M DTT, and 0.5µl of Proteinase K solution (20mg/µl) were added and incubated at 37ºC overnight. Next, 0.75µl of RNase A (4mg/ml) were added to the previous solution and then incubated at 37ºC for an additional 15 minutes. Samples were placed on ice for 15 minutes and 50µl of protein precipitation solution were added and mixed thoroughly for 1 minute, followed by a 4ºC centrifugation step of 20 minutes at 13,000g. The supernatant was discarded and the same centrifugation conditions were repeated. The supernatant was transferred to a low-binding DNA and RNA-free tube and 150µl of isopropanol and 0.25µl of glycogen solution (QIAGEN, #1045724) were added. The mix was gently mixed until a DNA bundle was formed and then centrifuged at 4ºC for 30 minutes at 13,000g. The supernatant was discarded and the DNA pellet was washed with 150µl of 70% ethanol, followed by a 4ºC centrifugation step of 3 minutes at 13,000g. The ethanol was carefully removed and the pellet was dried and resuspended in 25µl of TE buffer (pH 7.5).

2.3. Bead Emulsion Amplification (BEA)

Pre-BEA sample preparation. Testis, sperm or plasmid DNA samples were digested with CviQI (NEB) to create ~500 base pair fragments carrying the target sites. For the digest, 1200ng of genomic DNA was digested with 6U of CviQI (NEB), in 1x Phusion HF buffer in a 60µl reaction at 25°C for 1 hour followed by overnight incubation at 16°C.

Pre-BEA PCR. Genomic DNA targeting the loci of interest was amplified using primers F-ACH-88bp, R-ACH-R93-SNP R2, F-TDII-3, and R-TDII-BA with the primer sequences listed in Supplementary Methods. Reactions were prepared to a final volume of 20µl containing 200ng of genomic DNA, 1x GC buffer, 200µM of dNTPs, 1µM of each primer, 0.5x of EvaGreen, 3% DMSO and 0.02U/µl of Phusion Hot Start II polymerase. The reactions were held at 94°C for 3 minutes followed by 6 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds, 69°C for 15 seconds, 72°C for 10 seconds, and 8 additional cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 70°C for 15 seconds, 72°C for 10 seconds. Lastly, reactions were run at 72°C for 5 minutes and 65°C for 5 seconds as a final extension step.

Bead preparation. To begin with, 100µl of M-270/280 paramagnetic streptavidin-coated microbeads (ThermoScientific) were transferred into a low binding DNA tube and placed on the magnetic particle concentrator (MPC) for 1 minute. The supernatant was discarded and the beads were resuspended in 200µl of Bind and Wash Buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM Tris-EDTA pH 7.4, 2M NaCl). The reactions were placed on the MPC and the previous step was repeated 3 additional times. The isolated microbeads were resuspended and incubated in 198µl of Bind and Wash Buffer and 2µl of 1mM dual-biotinylated primer (Eurofins) for 20 minutes (resuspended every 5 minutes) at room temperature listed in

Supplementary Materials. The microbeads were then isolated on the MPC and washed twice in 200µl of Bind and Wash Buffer, followed by two washes in 200µl of TE Buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 and 1mM EDTA) and lastly eluted in 100µl of TE Buffer.

BEA. This procedure follows the exact protocols described previously in [

31] and initially described in [

32,

33] and elaborated in Supplementary Methods. Specifically, 1µl of a 1:10 dilution of the pre-BEA PCR reaction was hybridized to 6x10

6 beads covered with the Dual-biotinylated primer (see the previous section) in 1x TitatinumTaq Buffer and 16mM MgCl

2. The hybridization was carried out at 94°C for 2 minutes, 80°C for 5 minutes, followed by 15 minutes of exposure until it cools down to room temperature (0.1°C increments per second). The beads were washed once with water and mixed with the aqueous PCR phase with the same primers as in “Pre-BEA PCR” section and the oil phase as described in Supplementary Methods and in [

31] and initially described in [

32,

33].

The emulsion was prepared using the Dow-Corning components as described in Supplementary Methods and in [

31] and pipetted out in 8-PCR strip-tubes. The emulsion PCR was carried out in a standard thermocycler with an initial denaturation step of 94˚C for 2 minutes followed by 55 cycles at 94˚C for 15 seconds, 65°C for 15 seconds, 72˚C for 35 seconds and with an end step at 72˚C for 2 min. Beads were washed and labelled as described previously in [

31] with the probes targeting the site of interest by an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 2 minutes followed by 60°C for 5 minutes, 72°C for 5 minutes and kept at 75˚C until unextended probes were washed off. Samples were then immobilized on a microscope slide and scanned as described in Supplementary Methods and in [

31] and initially described in [

32,

33]. In each experiment, only ~10% of the beads amplified a product given the low input ratio of DNA molecules to beads to assure that most of beads get attached to only one initial molecule based on Poisson distribution. Experiments rendering more than 30% positives were discarded and repeated considering that beads seeded with more than one molecule could result in an underestimate of the mutation number. If both a mutant and wild type molecule are on a bead, the bead results in a multi-coloured bead eliminated during the analysis.

Dye switches. After scanning the beads with a microscope, the probes were washed off and the beads were re-labelled with the probes of interest (see section 6.5.5.1) at 95°C for 2 minutes followed by 63°C for 5 minutes, 72°C for 5 minutes and kept at 75°C until unextended probes were washed off. The dye switch was performed in a hybridization chamber and in situ PCR block as described previously [

25,

31]. Since the beads were immobilized on an acrylamide array, it was possible to re-scan the beads without losing the positional information of each bead. The labeling probes are listed in

Supplementary Materials

Bead-calling. For each experiment two sets with 5 images each were analyzed. Brightfield images between scans (normal scan and dye switch scan) were aligned by computing the normalized cross correlation matrix of pairs of images in Matlab (Mathworks) as described previously [

31]. In brief, the analysis of images at each raster position involves custom Matlab algorithms. This process includes correcting random shifts between images by registering them based on normalized correlation. Images requiring more than a 500-pixel alignment correction are discarded. A mask is created for bright field images using wavelet-based segmentation, and this mask is then applied to subsequent washes. Beads are identified by comparing masks, and the mean fluorescent signal intensity for each bead is extracted, along with the bead identifier and area, saved in a text file. The text file categorizes beads into four clusters (00, 10, 01, 11) based on signal intensities, aiding in the classification of beads with specific genotypes. The ‘11’ cluster represents beads fluorescing in both channels, and the ‘00’cluster represents empty beads with no fluorescence. The classification scheme was based on a Gaussian Mixture model and normalization parameters described in detail previously [

32]. Wild type beads were identified as beads classified as 1001 and mutants as 0110.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine a linear correlation between the observed and expected VAFs for the control samples using the software OriginPro (OriginLab Corporation). Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to test the correlation between variant allele frequency (VAF) and sperm donors’ age using the software OriginPro (OriginLab Corporation). Mann-Whitney-U test was used to compare the differences in the accumulation of mutations in sperm between ACH and TDII variants. All VAF presented in this work were Poisson corrected according to the following formula:

3. Results

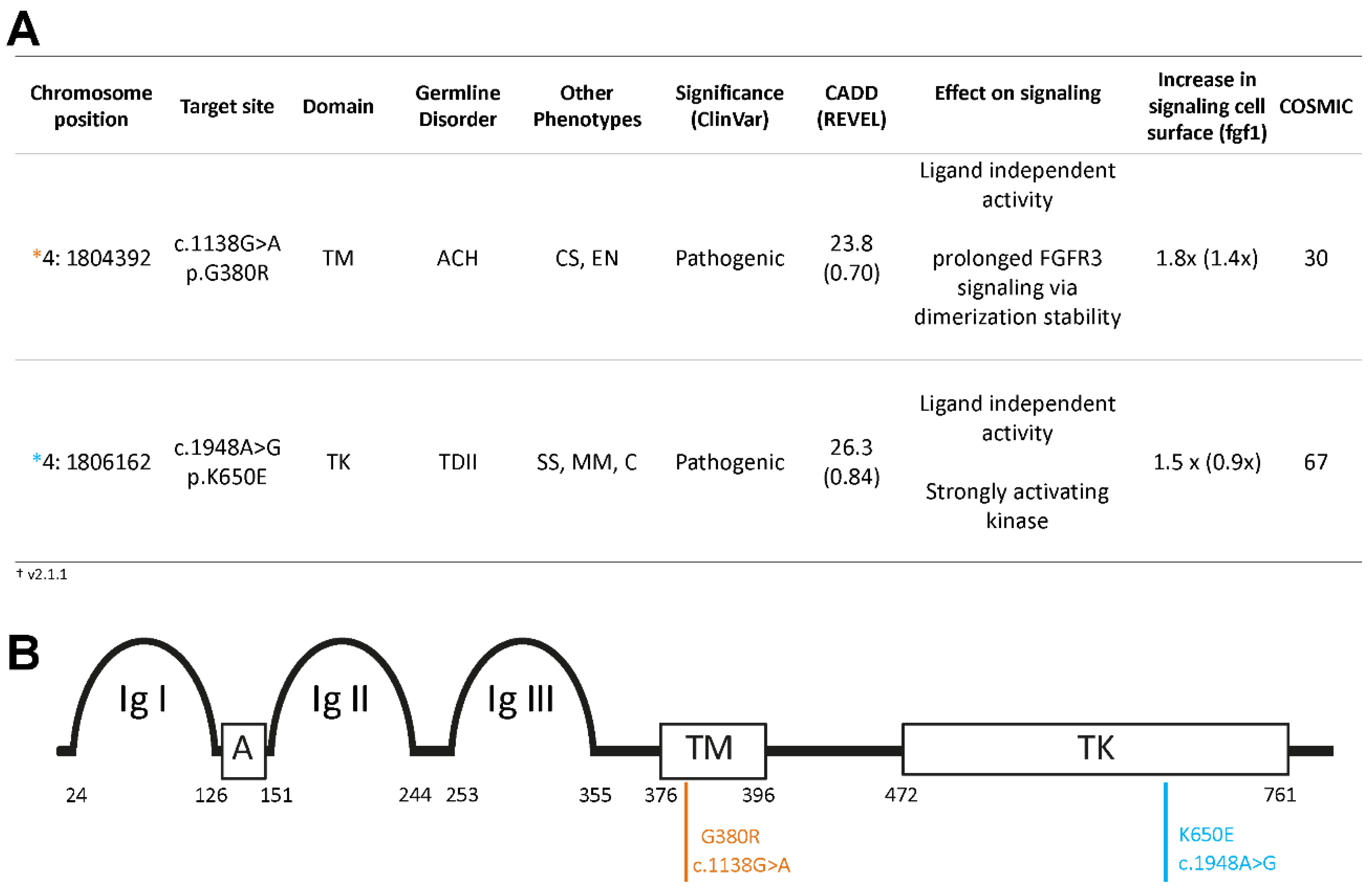

We examined the variant allele frequency (VAF) of c.1138G>A (p.G380R) and c.1948A>G (p.K650E) in sperm donors of diverse ages and in one post-mortem dissected testis of a 68-year-old donor. The c.1138G>A (p.G380R) variant, screened in the same experiment with some data presented elsewhere [

19], is associated with ACH, craniosynostosis syndrome, and epidermal nevus [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], and is well-characterized in the male germline. It is more prevalent in sperm from older donors [

17,

40], forms sub-clonal clusters in the testis [

23,

25], and has a higher incidence in offspring of older fathers [

7,

35,

39]. Its

in silico predicted deleteriousness CADD score is 23.8 (

Figure 1), and it has been reported to exhibit moderate ligand-independent, constitutive activation of the RTK signaling pathway [

19,

29,

41,

42,

43].

The pathogenic variant c.1948A>G (p.K650E) is associated with TDII and has been observed in spermatocytic seminoma and multiple myeloma cases [

44,

45,

46]. With a CADD score of 26.3 and a substantial mutation count reported in COSMIC (

Figure 1), this missense substitution is embryonic lethal already at the heterozygous state. The constitutively active TDII mutation [

47,

48] was reported as one of the strongest activating mutants of FGFR3 signaling in whole cell lysates [

43,

49]. Yet, the comparative analysis of signaling at the plasma membrane showed a similar ligand-independent activation of both mutations [

29]. Both variants are classified as deleterious/pathogenic by ClinVar (

Figure 1).

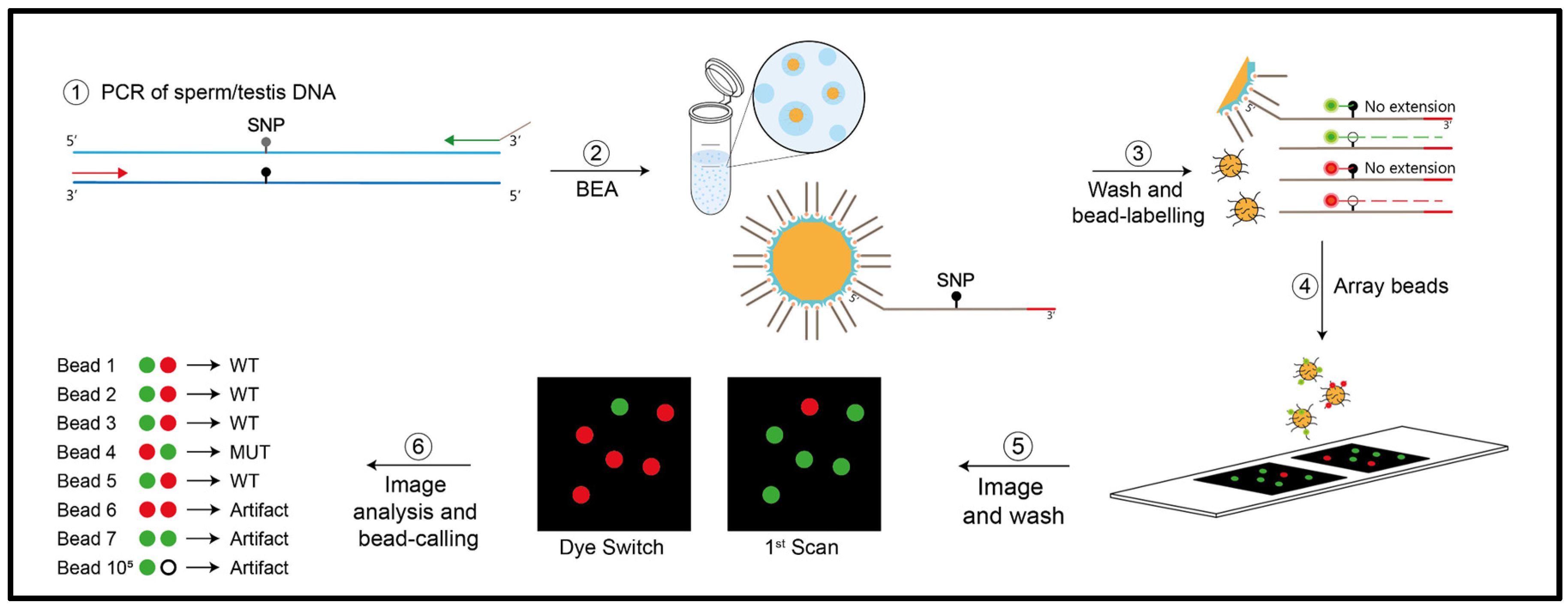

3.1. Measuring Low Frequency Mutations in the Male Germline

In order to measure mutation frequencies of both

FGFR3 variants in sperm and testis DNA, we used digital PCR that can measure VAFs ≥10

-5. Specifically, we used bead emulsion amplification (BEA), an in-house digital PCR method that examines single molecules multiplexed for two sites that was previously validated [

25,

31,

32,

33]. A schematic of this method is shown in

Figure 2.

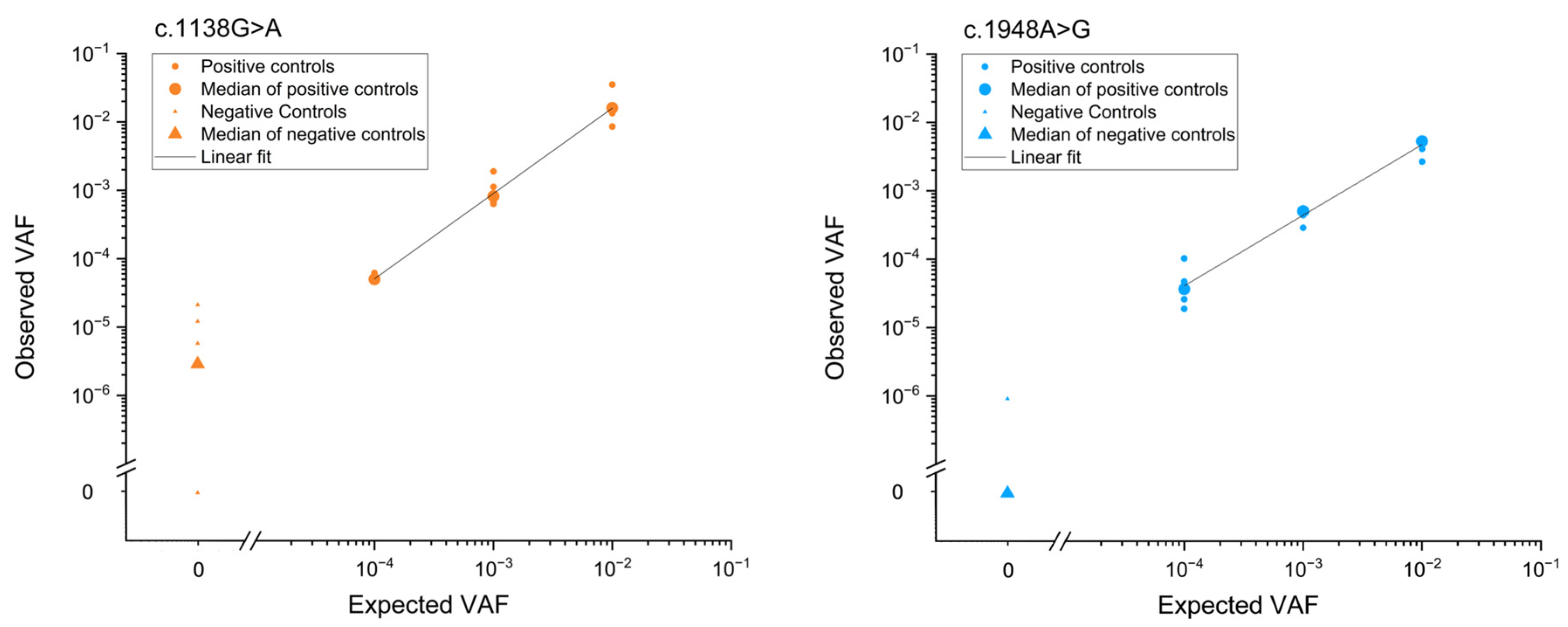

Accuracy and reproducibility of the method were determined through a serial dilution experiment with positive controls (ACH- or TDII carrier DNA) spiked into wild-type (WT) human genomic DNA at various ratios (

Figure 3 and

Supplementary Table S1). The method exhibited a good correlation between input and observed ratios of genomic DNA. A Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) of 0.99 and 0.98 for c.1138G>A and c.1948A>G, respectively, confirmed the assay’s accuracy and reproducibility. Additionally, the background mutation level of a wild-type plasmid was measured, revealing levels below of the positive controls (

Figure 3), and reflects the method's sensitivity to measure VAFs at 10

-5 or larger. In this study, we utilized approximately 300,000 genomes per input, followed by PCR and emulsion amplification on beads.

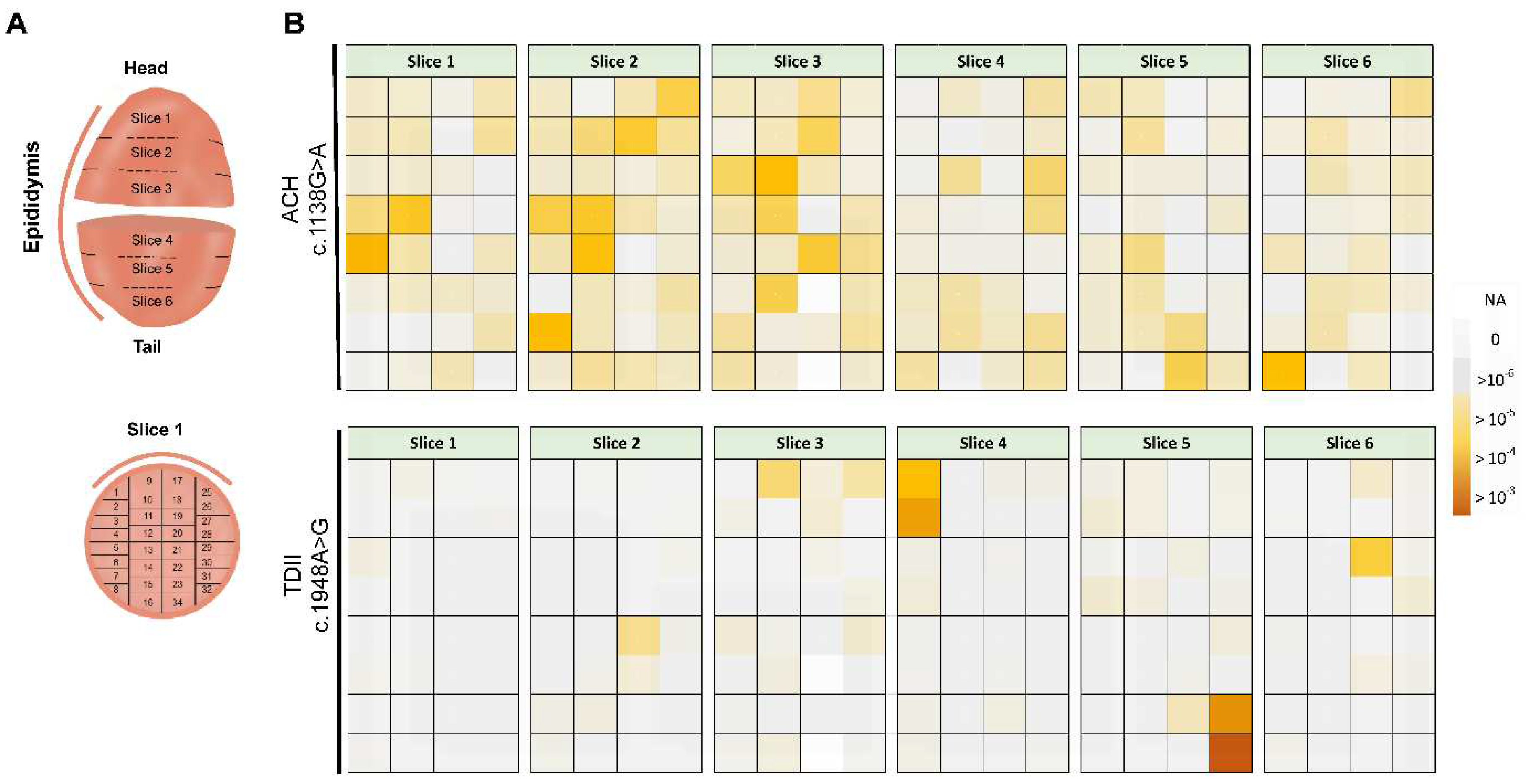

3.2. Transmission of Mutations in Testis

To test the sub-clonal expansion in the male gonad, we assessed the spatial distribution of the mutations in a testis of a post-mortem donor (68-years old). We adapted the testis dissection strategy used previously in combination with single-molecule PCR screening for this purpose [

20,

21,

24,

25]. Briefly, the human testis was dissected into 6 slices and further cut into 192 pieces (

Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4B shows the spatial distribution of c.1138G>A and c.1948A>G (data in

Supplementary Table S2).

For the canonical PAE variant associated with ACH (c.1138G>A), we measured mutations in many pieces (average VAF= 3.5x10

-5; median VAF = 2.3x10

-5); yet, some pieces accumulated more mutations than neighboring pieces with the highest measured VAF (MaxVAF) being 4.1x10

-4. The MaxVAF/IQR ratio, representing the highest VAF of all pieces relative to the rest of the testis, was ~12-fold larger than the interquartile range (IQR), with 64% of the testis capturing 95% of the mutants (P>95,

Table 1). In the case that mutations are uniformly distributed (no cluster formation), the MaxVAF/IQR should be closer to 1.

The TDII mutation exhibited a more extreme non-uniform distribution, forming very strong clusters that were 2-3 orders of magnitude higher than adjacent pieces (

Figure 4B). The MaxVAF/IQR ratio differed by over two orders of magnitude (MaxVAF/IQR ~500-fold;

Table 1). The average VAF was 3x10

-5, with a few individual pieces showing VAFs as high as 10

-3, which contributed to most of the mutations with 12% of the testis capturing 95% of the mutants (P>95). These parameters strongly support a sub-clonal expansion event for TDII, with individual pieces reaching higher VAFs than for the ACH mutation, and indicates a stronger clonal expansion for TDII than for the canonical PAE mutation ACH.

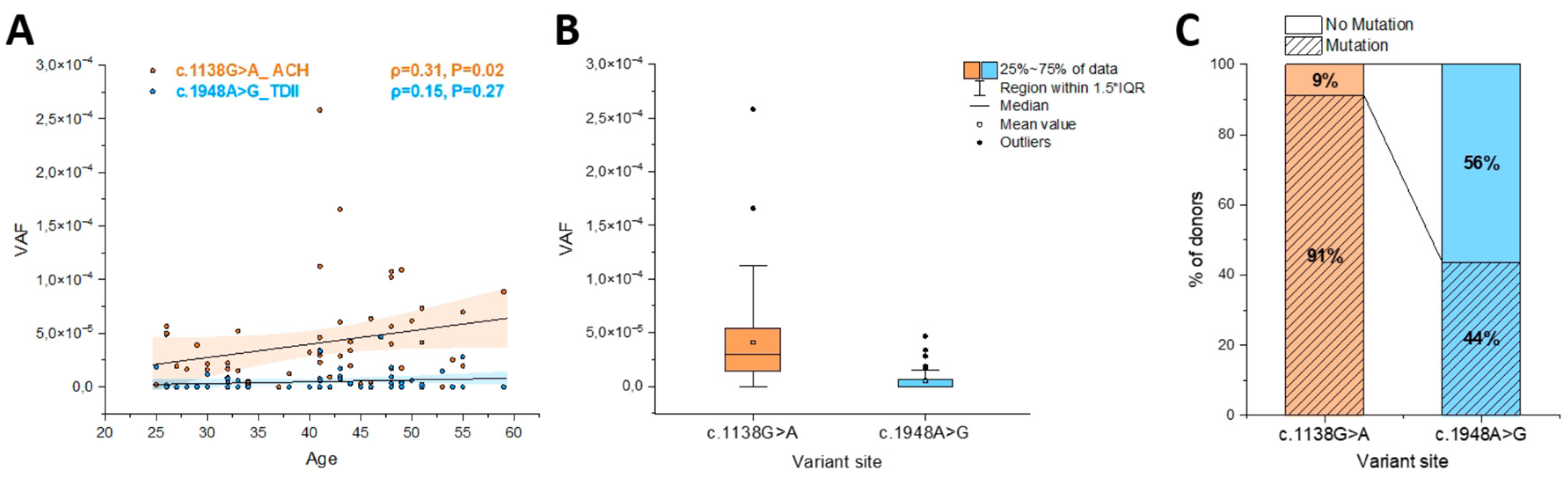

3.3. Transmission of Mutations in Sperm

We examined in parallel 55-56 sperm donors (25 to 59 years) for the ACH and the TDII mutation, respectively. As shown in

Figure 5A, the ACH mutation (c.1138G>A) increased with the donor’s age with the VAF showing a positive correlation (ρ=0.31) measured with the Spearman’s correlation test that was significant (P=0.02), as was also reported in [

19]. The highest VAF (MaxVAF,

Table 2) was 2.6x10

-4 measured in a 41-year-old sperm donor with the median VAF for all sperm donors reaching 2.9x10

-5, and an interquartile range (IQR) of 5.9x10

-5 (

Table 2;

Supplementary Table S3).

In comparison, for the TDII mutation (c.1948A>G) older sperm donors generally showed an increased mutation accumulation, as indicated by a positive correlation (ρ=0.15), but this correlation did not reach statistical significance (P=0.27;

Figure 5A). The maximum VAF of 4.7x10

-5 was measured in a 47-year-old sperm donor. The median frequency was 0 and the interquartile range (IQR) 5x10

-6 was almost 7-fold lower for TDII than for the ACH mutation (

Table 2). Overall, the mean, median and IQR VAFs were an order of magnitude lower for TDII than for the ACH mutation and the difference in the mutational load between these two variants is significant when comparing all the data (

Figure 5B).

We also compared the ratio of samples in which a mutation was measured to those without any mutations (

Figure 5C). It should be noted that samples with no mutations might not represent a VAF of 0, but are likely within the detection limit of the Poisson distribution, for which the positive events occur approximately 60% of the time for VAF frequencies lower than 10

-5 with the input of 300,000 genomes. Note that for the ACH mutation (c.1138G>A) most of the samples carried mutations (91%), whereas for the TDII mutation (c.1948A>G) this percentage was 44%, also suggesting that in general the same sample had a lower VAF for TDII often resulting in an ‘empty’ measurement or a VAF of zero.

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathogenic FGFR3 Mutations Accumulate Differently in the Ageing Male Germline

Our study, utilizing bead-emulsion amplification (BEA), contributes important insights into the accumulation of pathogenic FGFR3 variants in the ageing male germline. Our measurements were highly accurate and sensitive for both variants, c.1138G>A and c.1948A>G, in sperm and testis DNA, albeit we cannot exclude that data for c.1138G>A is noisier and samples with VAFs smaller than 10-5 might contain some false positive counts based on the behavior of the negative plasmid controls.

Sub-clonal expansion events in the testis were observed for both the ACH (c.1138G>A) and the TDII mutation (c.1948A>G), with individual testis pieces reaching high levels, particularly c.1948A>G reaching the highest VAF at 10

-3. The observation of sub-clonal expansion events for the c.1138G>A locus in a testis of an older donor, has been reported previously using the same BEA method [

25] or sequencing individual testis biopsies selected by

in situ screening of increased FGFR3 signaling [

23]. In addition, our measurements of an average VAF of 3.5x10

-5 for the c.1138G>A variant are consistent with findings in testis biopsies measuring VAFs of a similar magnitude (4.5x10

-5, n=5) from donors aged 65 to 70 years [

23]. Our data also are consistent with previous reports showing an increase of the ACH mutation (c.1138G>A) in sperm DNA [

17,

40].

For the TDII mutation (c.1948A>G), we also observe strong clustering in the testis, which aligns with the severity of the associated clinical outcome resulting in embryonic lethality. However, contrary to the expectation that large clonal expansions in the ageing testis leads to an increase of mutant sperm in older donors, for c.1148A>G the VAF increase with the donor’s age was modest and not significant. Interestingly, the VAFs measured in sperm for this variant was significantly lower by almost an order of magnitude than VAFs measured for the ACH mutation (c.1138G>A). The reduced birth incidence in TDII (1 in 100,000) compared to ACH (1 in 15,000-30,000) [

6,

38,

46,

54] may also be attributed to a lower number of TDII mutant sperm.

4.2. Activation of Tyrosine Kinase Signaling by the Mutations Associated with ACH and TDII

It has been suggested that the expansion of different

FGFR3 variants in the male germline are driven by similar biological mechanisms, but to date, there has been limited data supporting this view. The ACH mutation c.1138G>A (p.G380R) introduces a strong negative charge in the dimerization interface of the transmembrane helices and was proposed to stabilize the active FGFR3 dimer resulting in a ligand-independent autoactivation potential of the receptor and enhanced signaling activity [

41,

43,

48]. In contrast, the TDII mutation c.1948A>G (p.K650E) mimics the activating phosphorylation in the kinase domain, thereby rendering the kinase constitutively active irrespective of dimerization and growth factor signaling [

47,

48]. Consistently p.K650E has been described as one of the strongest activating mutations of FGFR3 in whole-cell lysates [

42,

43,

47,

48,

49].

A recent study compared different FGFR3 variants regarding their downstream signaling at the cellular surface, using a combination of micropatterns and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. It measured the recruitment of the downstream adaptor protein GRB by the FGFR3 mutants c.1138G>A (pG380R) and c.1948A>G (p.K650E) with and without the addition of fibroblast growth factor (fgf) ligands fgf1 and fgf2 [

19,

29]. Both substitutions induced a ligand-independent recruitment at the basal state, with the ACH mutation(G380R) showing a higher level of activation than the TDII variant (K650E) [

29]. Interestingly this is in contrast to previous studies that estimated receptor activation based on the level of tyrosine phosphorylation in the respective mutant in whole cell lysates (e.g. [

43]). It is possible that whilst the TDII mutant strongly enhances kinase activity this does not translate into downstream activation at the cell surface level. However, the mutant FGFR3 intracellular protein chain (trapped inside the cellular export machinery) still might induce a strong activation of downstream extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) proteins inside the cell [

55,

56,

57].

Role of RTK-MAPK in Meiotic Differentiation from Sperm into Spermatids

Spermatogenesis in the adult human testis involves a delicate balance between spermatogonial stem cell (SSC) self-renewal and differentiation, supported by germ cell-niche interactions with various somatic cell types (Leydig, myoid, Sertoli, endothelial, macrophage) as identified by single-cell transcriptomics of a large number of testis cells [

58,

59]. Additionally, male germ cells undergo the intricate process of meiosis, transforming from mitotic spermatogonia to spermatocytes. This transition is characterized by significant gene expression changes during male meiosis and spermiogenesis [

60].

The tyrosine phosphatase SHP2, encoded by the

PTPN11 gene, part of the downstream RTK signaling cascade plays a key role in spermatogenesis and the maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells [

61]. It is also crucial for maintaining a functional blood–testis barrier (BTB) [

62]. Specifically, the absence of SHP2 (tested in SHP2knockout mice) disrupts spermatogenesis by modifying the actin cytoskeleton, mislocalizing key junction proteins at the BTB, consequently affecting junction integrity and Sertoli cell support of spermatogenesis [

62]. In addition, in SHP2 knockout mice SSC differentiation was affected, leading to a reduction in spermatogonial number [

61,

63].

The RTK-MAPK signaling is also important in regulating the expression of numerous genes/proteins associated with meiotic recombination and synapsis. In SHP2 knock-outs the expression of meiotic proteins was suppressed and caused meiotic spermatocytes to undergo apoptosis [

63]. This might explain male infertility in gain- and loss-of-function mutations in

PTPN11 associated with pathological conditions such as Noonan syndrome and LEOPARD syndrome [

61,

63]. SHP2 is abundant in spermatogonia but markedly decreases in meiotic spermatocytes, along with the increased expression of meiotic genes (e.g.,

Dmc1,

Rad51,

Smc3 was reduced in SHP2 knockouts) [

58,

63]. Further, RTK-MAPK signaling is important in regulating the disassembly of synaptonemal complex (SC) proteins during late meiotic pachytene with the MAPK inactivation being required for the timely disassembly of SC proteins and coordination of crossing-overs [

64]. Conversely, constitutively phosphorylated SYP-2 of the SC was found to impair the disassembly of the SC and the progression of the meiotic cell cycle [

64].

Together, these findings suggest that an aberrant RTK-MAPK signaling might have an effect on the differentiation phases from spermatogonia to spermatid formation. A study examining the different possible mutations associated with codon p.650 in FGFR3 observed that variants with significantly increased receptor kinase activity compared to wild type [

43], also had a strong expansion prevalence in somatic (e.g. skin tumors) and male germline tissue (e.g. testicular tumors), but were underrepresented in sperm [

15]. However, this observation may be attributed to two plausible hypotheses: firstly, robust sub-clonal expansions may not be induced in the normal ageing testis by strong activation of the RTK signaling, or secondly, SSC cells may not differentiate into sperm with meiosis being impaired. Note that each scenario is possible since each affects different cell types: spermatogonia or spermatocytes, respectively

Based on our study, measuring the mutation distribution in both testis and sperm, we suggest that in the context of RTK constitutive and high signaling, only a fraction of mutant SSC differentiate into sperm. We observed that the TDII mutation (c.1948A>G) clustered strongly in the testis, aligning with its phenotypic severity, but showed only a modest and non-significant age-related increase in sperm. This contrasting mutational load in testis versus sperm is best explained by a mechanism hindering spermiogenesis interfering with meiosis in mutant spermatocytes due to aberrant RTK signaling. Also, VAFs in sperm for the TDII mutation were an order of magnitude lower than for the ACH mutation (c.1138G>A).

A decrease in average VAFs in testis compared to sperm for activating RTK mutations can also be derived indirectly from data on the mutation associated with Apert syndrome (c.755C>G, p.S252W in

FGFR2). This variant is located in the linker region between the IGII and IGIII domain and contributes to the FGF binding site of the receptor. Its mutation causes a loss of specificity for the activating growth factor and results in an increased unspecific activation of the receptor [

65]. The average number of mutations for variant c.755C>G in

FGFR2, measured in the testis was 8-10 times higher than the average mutation frequency measured in sperm when comparing age groups older than 35 years (

Table 3). Specifically, 18% of 168 sperm donors versus 83% of the testis donors within a middle aged-group (36-68 years) had a higher average VAF than the youngest group eliminating the possibility of a sample size effect. This discrepancy, observed across data collected by the same method and group [

18,

21], also challenges the assumption that larger clusters in the testes also results in a higher mutation load in sperm.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our investigation revealed distinct behaviors for c.1138G>A and c.1948A>G variants. The observed discordance between mutation frequency in testis and sperm for these two variants underscores the intricate interplay between activation levels, ageing, and meiotic differentiation, offering a foundation for further understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the expansion and transmission of pathogenic driver mutations in the male germline.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Data Availability Statement

Author’s Contributions: Conceptualization, I.T-B. and B.A.; methodology, B.A., E.N., Y.S.; software, L.M.; validation, S.M., R.S. B.A. and Y.S.; formal analysis, Y.S.; investigation, B.A., Y.S. and I.T-B.; resources, T.E.; data curation, Y.S., S.M., R.S., R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, I.T-B.,; writing—review and editing, I.T-B, Y.S., and R.R.; visualization, Y.S., supervision I.T-B.; project administration, I.T-B.; funding acquisition, I.T.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by ITB from the Austrian Research Fund (FWF) grant numbers (P30867000; FWFP25525000-and SFB F-8809-B). We would like to thank Philipp Hermann for the advice on statistical testing. We would also like to thank the Greenwood Genetic Center, South Carolina for kindly providing a heterozygous DNA with the c.1948A>G mutation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Wilson, G.A.; McGranahan, N.; Birkbak, N.J.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Veeriah, S.; Shafi, S.; Johnson, D.H.; Mitter, R.; Rosenthal, R.; et al. Tracking the Evolution of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turajlic, S.; Xu, H.; Litchfield, K.; Rowan, A.; Horswell, S.; Chambers, T.; O'Brien, T.; Lopez, J.I.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Nicol, D.; et al. Deterministic Evolutionary Trajectories Influence Primary Tumor Growth: TRACERx Renal. Cell 2018, 173, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, L.R.; Gerstung, M.; Knappskog, S.; Desmedt, C.; Gundem, G.; Van Loo, P.; Aas, T.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Larsimont, D.; Davies, H.; et al. Subclonal diversification of primary breast cancer revealed by multiregion sequencing. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasetti, C.; Vogelstein, B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015, 347, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, K.A.; Goriely, A. The impact of paternal age on new mutations and disease in the next generation. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orioli, I.M.; Castilla, E.E.; Barbosa-Neto, J.G. The birth prevalence rates for the skeletal dysplasias. J. Med. Genet. 1986, 23, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risch, N.; Reich, E.W.; Wishnick, M.M.; McCarthy, J.G. Spontaneous mutation and parental age in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1987, 41, 218–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crow, J.F. Upsetting the dogma: Germline selection in human males. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannan-Eliya, S.V.; Taylor, I.B.; De Heer, I.M.; Van Den Ouweland, A.M.; Wall, S.A.; Wilkie, A.O. Paternal origin of FGFR3 mutations in Muenke-type craniosynostosis. Hum. Genet. 2004, 115, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, M.; Cordeddu, V.; Chang, H.; Shaw, A.; Kalidas, K.; Crosby, A.; Patton, M.A.; Sorcini, M.; van der Burgt, I.; Jeffery, S.; et al. Paternal germline origin and sex-ratio distortion in transmission of PTPN11 mutations in Noonan syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 75, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampino, G.; Pantaleoni, F.; Carta, C.; Cobellis, G.; Vasta, I.; Neri, C.; Pogna, E.A.; De Feo, E.; Delogu, A.; Sarkozy, A.; et al. Diversity, parental germline origin, and phenotypic spectrum of de novo HRAS missense changes in Costello syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnheim, N.; Calabrese, P. Understanding what determines the frequency and pattern of human germline mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnheim, N.; Calabrese, P. Germline Stem Cell Competition, Mutation Hot Spots, Genetic Disorders, and Older Fathers. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2016, 17, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goriely, A.; Wilkie, A.O. Paternal age effect mutations and selfish spermatogonial selection: Causes and consequences for human disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 90, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goriely, A.; Hansen, R.M.; Taylor, I.B.; Olesen, I.A.; Jacobsen, G.K.; McGowan, S.J.; Pfeifer, S.P.; McVean, G.A.; Rajpert-De Meyts, E.; Wilkie, A.O. Activating mutations in FGFR3 and HRAS reveal a shared genetic origin for congenital disorders and testicular tumors. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goriely, A.; McVean, G.A.; Rojmyr, M.; Ingemarsson, B.; Wilkie, A.O. Evidence for selective advantage of pathogenic FGFR2 mutations in the male germ line. Science 2003, 301, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiemann-Boege, I.; Navidi, W.; Grewal, R.; Cohn, D.; Eskenazi, B.; Wyrobek, A.J.; Arnheim, N. The observed human sperm mutation frequency cannot explain the achondroplasia paternal age effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14952–14957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.R.; Qin, J.; Glaser, R.L.; Jabs, E.W.; Wexler, N.S.; Sokol, R.; Arnheim, N.; Calabrese, P. The ups and downs of mutation frequencies during aging can account for the Apert syndrome paternal age effect. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, S.; Hartl, I.; Brumovska, V.; Yasari, A.; Striedner, Y.; Bishara, M.; Mair, T.; Ebner, T.; Schütz, G.J.; Calabrese, P.P.; et al. Exploring FGFR3 mutations in the male germline: Implications for clonal germline expansions and paternal age-related dysplasias. Genome Biol. Evol. under review.

- Choi, S.K.; Yoon, S.R.; Calabrese, P.; Arnheim, N. A germ-line-selective advantage rather than an increased mutation rate can explain some unexpectedly common human disease mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10143–10148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.K.; Yoon, S.R.; Calabrese, P.; Arnheim, N. Positive selection for new disease mutations in the human germline: Evidence from the heritable cancer syndrome multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eboreime, J.; Choi, S.K.; Yoon, S.R.; Sadybekov, A.; Katritch, V.; Calabrese, P.; Arnheim, N. Germline selection of PTPN11 (HGNC:9644) variants make a major contribution to both Noonan syndrome's high birth rate and the transmission of sporadic cancer variants resulting in fetal abnormality. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 2205–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, G.J.; Ralph, H.K.; Ding, Z.; Koelling, N.; Mlcochova, H.; Giannoulatou, E.; Dhami, P.; Paul, D.S.; Stricker, S.H.; Beck, S.; et al. Selfish mutations dysregulating RAS-MAPK signaling are pervasive in aged human testes. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 1779–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Calabrese, P.; Tiemann-Boege, I.; Shinde, D.N.; Yoon, S.R.; Gelfand, D.; Bauer, K.; Arnheim, N. The molecular anatomy of spontaneous germline mutations in human testes. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, D.N.; Elmer, D.P.; Calabrese, P.; Boulanger, J.; Arnheim, N.; Tiemann-Boege, I. New evidence for positive selection helps explain the paternal age effect observed in achondroplasia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 4117–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.R.; Choi, S.K.; Eboreime, J.; Gelb, B.D.; Calabrese, P.; Arnheim, N. Age-dependent germline mosaicism of the most common noonan syndrome mutation shows the signature of germline selection. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 92, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmon, M.A.; Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 2010, 141, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, G.J.; McGowan, S.J.; Giannoulatou, E.; Verrill, C.; Goriely, A.; Wilkie, A.O. Visualizing the origins of selfish de novo mutations in individual seminiferous tubules of human testes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2454–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartl, I.; Brumovska, V.; Striedner, Y.; Yasari, A.; Schutz, G.J.; Sevcsik, E.; Tiemann-Boege, I. Measurement of FGFR3 signaling at the cell membrane via total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy to compare the activation of FGFR3 mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbeithuber, B.; Betancourt, A.J.; Ebner, T.; Tiemann-Boege, I. Crossovers are associated with mutation and biased gene conversion at recombination hotspots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2109–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palzenberger, E.; Reinhardt, R.; Muresan, L.; Palaoro, B.; Tiemann-Boege, I. Discovery of Rare Haplotypes by Typing Millions of Single-Molecules with Bead Emulsion Haplotyping (BEH). Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1551, 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulanger, J.; Muresan, L.; Tiemann-Boege, I. Massively parallel haplotyping on microscopic beads for the high-throughput phase analysis of single molecules. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiemann-Boege, I.; Curtis, C.; Shinde, D.N.; Goodman, D.B.; Tavare, S.; Arnheim, N. Product length, dye choice, and detection chemistry in the bead-emulsion amplification of millions of single DNA molecules in parallel. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 5770–5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accogli, A.; Pacetti, M.; Fiaschi, P.; Pavanello, M.; Piatelli, G.; Nuzzi, D.; Baldi, M.; Tassano, E.; Severino, M.S.; Allegri, A.; et al. Association of achondroplasia with sagittal synostosis and scaphocephaly in two patients, an underestimated condition? Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2015, 167A, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellus, G.A.; Hefferon, T.W.; Ortiz de Luna, R.I.; Hecht, J.T.; Horton, W.A.; Machado, M.; Kaitila, I.; McIntosh, I.; Francomano, C.A. Achondroplasia is defined by recurrent G380R mutations of FGFR3. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995, 56, 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Georgoulis, G.; Alexiou, G.; Prodromou, N. Achondroplasia with synostosis of multiple sutures. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2011, 155A, 1969–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, C.; van Oers, J.M.; Vogt, T.; Landthaler, M.; Stoehr, R.; Blaszyk, H.; Hofstaedter, F.; Zwarthoff, E.C.; Hartmann, A. Mosaicism of activating FGFR3 mutations in human skin causes epidermal nevi. J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 2201–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, F.; Bonaventure, J.; Legeai-Mallet, L.; Pelet, A.; Rozet, J.M.; Maroteaux, P.; Le Merrer, M.; Munnich, A. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature 1994, 371, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiang, R.; Thompson, L.M.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Church, D.M.; Fielder, T.J.; Bocian, M.; Winokur, S.T.; Wasmuth, J.J. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia. Cell 1994, 78, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, R.; Arbeithuber, B.; Ivankovic, M.; Heinzl, M.; Moura, S.; Hartl, I.; Mair, T.; Lahnsteiner, A.; Ebner, T.; Shebl, O.; et al. Discovery of an unusually high number of de novo mutations in sperm of older men using duplex sequencing. Genome Res. 2022, 32, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocharov, E.V.; Lesovoy, D.M.; Goncharuk, S.A.; Goncharuk, M.V.; Hristova, K.; Arseniev, A.S. Structure of FGFR3 transmembrane domain dimer: Implications for signaling and human pathologies. Structure 2013, 21, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Hristova, K. The physical basis of FGFR3 response to fgf1 and fgf2. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 8576–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naski, M.C.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Ornitz, D.M. Graded activation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 by mutations causing achondroplasia and thanatophoric dysplasia. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesi, M.; Nardini, E.; Brents, L.A.; Schrock, E.; Ried, T.; Kuehl, W.M.; Bergsagel, P.L. Frequent translocation t(4;14)(p16.3;q32.3) in multiple myeloma is associated with increased expression and activating mutations of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat. Genet. 1997, 16, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavormina, P.L.; Shiang, R.; Thompson, L.M.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Wilkin, D.J.; Lachman, R.S.; Wilcox, W.R.; Rimoin, D.L.; Cohn, D.H.; Wasmuth, J.J. Thanatophoric dysplasia (types I and II) caused by distinct mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat. Genet. 1995, 9, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, W.R.; Tavormina, P.L.; Krakow, D.; Kitoh, H.; Lachman, R.S.; Wasmuth, J.J.; Thompson, L.M.; Rimoin, D.L. Molecular, radiologic, and histopathologic correlations in thanatophoric dysplasia. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998, 78, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, H.; Blais, S.; Neubert, T.A.; Li, X.; Mohammadi, M. Structural mimicry of a-loop tyrosine phosphorylation by a pathogenic FGF receptor 3 mutation. Structure 2013, 21, 1889–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, M.K.; D'Avis, P.Y.; Robertson, S.C.; Donoghue, D.J. Profound ligand-independent kinase activation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 by the activation loop mutation responsible for a lethal skeletal dysplasia, thanatophoric dysplasia type II. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996, 16, 4081–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellus, G.A.; Spector, E.B.; Speiser, P.W.; Weaver, C.A.; Garber, A.T.; Bryke, C.R.; Israel, J.; Rosengren, S.S.; Webster, M.K.; Donoghue, D.J.; et al. Distinct missense mutations of the FGFR3 lys650 codon modulate receptor kinase activation and the severity of the skeletal dysplasia phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 67, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, J.D.; Laskowski, R.A.; Nightingale, A.; Hurles, M.E.; Thornton, J.M. VarMap: A web tool for mapping genomic coordinates to protein sequence and structure and retrieving protein structural annotations. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4854–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircher, M.; Witten, D.M.; Jain, P.; O'Roak, B.J.; Cooper, G.M.; Shendure, J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, N.M.; Rothstein, J.H.; Pejaver, V.; Middha, S.; McDonnell, S.K.; Baheti, S.; Musolf, A.; Li, Q.; Holzinger, E.; Karyadi, D.; et al. REVEL: An Ensemble Method for Predicting the Pathogenicity of Rare Missense Variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, J.G.; Bamford, S.; Jubb, H.C.; Sondka, Z.; Beare, D.M.; Bindal, N.; Boutselakis, H.; Cole, C.G.; Creatore, C.; Dawson, E.; et al. COSMIC: The Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D941–D947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.E., Jr. Prevalence of lethal osteochondrodysplasias in Denmark. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1989, 32, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventure, J.; Horne, W.C.; Baron, R. The localization of FGFR3 mutations causing thanatophoric dysplasia type I differentially affects phosphorylation, processing and ubiquitylation of the receptor. FEBS J. 2007, 274, 3078–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, L.; Legeai-Mallet, L. FGFR3 intracellular mutations induce tyrosine phosphorylation in the Golgi and defective glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1773, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lievens, P.M.; Mutinelli, C.; Baynes, D.; Liboi, E. The kinase activity of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 with activation loop mutations affects receptor trafficking and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 43254–43260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Grow, E.J.; Mlcochova, H.; Maher, G.J.; Lindskog, C.; Nie, X.; Guo, Y.; Takei, Y.; Yun, J.; Cai, L.; et al. The adult human testis transcriptional cell atlas. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Nie, X.; Giebler, M.; Mlcochova, H.; Wang, Y.; Grow, E.J.; DonorConnect; Kim, R. ; Tharmalingam, M.; Matilionyte, G.; et al. The Dynamic Transcriptional Cell Atlas of Testis Development during Human Puberty. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, B.P.; Cheng, K.; Singh, A.; Roa-De La Cruz, L.; Mutoji, K.N.; Chen, I.C.; Gildersleeve, H.; Lehle, J.D.; Mayo, M.; Westernstroer, B.; et al. The Mammalian Spermatogenesis Single-Cell Transcriptome, from Spermatogonial Stem Cells to Spermatids. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Phillips, B.T.; Suzuki, H.; Orwig, K.E.; Rajkovic, A.; Lapinski, P.E.; King, P.D.; Feng, G.S.; Walker, W.H. The transition from stem cell to progenitor spermatogonia and male fertility requires the SHP2 protein tyrosine phosphatase. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, P.; Walker, W.H. The tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 regulates Sertoli cell junction complexes. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 88, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, W.S.; Yi, J.; Kong, S.B.; Ding, J.C.; Zhao, Y.N.; Tian, Y.P.; Feng, G.S.; Li, C.J.; Liu, W.; et al. The role of tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 in spermatogonial differentiation and spermatocyte meiosis. Asian J. Androl. 2020, 22, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarajan, S.; Mohideen, F.; Tzur, Y.B.; Ferrandiz, N.; Crawley, O.; Montoya, A.; Faull, P.; Snijders, A.P.; Cutillas, P.R.; Jambhekar, A.; et al. The MAP kinase pathway coordinates crossover designation with disassembly of synaptonemal complex proteins during meiosis. Elife 2016, 5, e12039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Herr, A.B.; Waksman, G.; Ornitz, D.M. Loss of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 ligand-binding specificity in Apert syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 14536–14541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).