Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

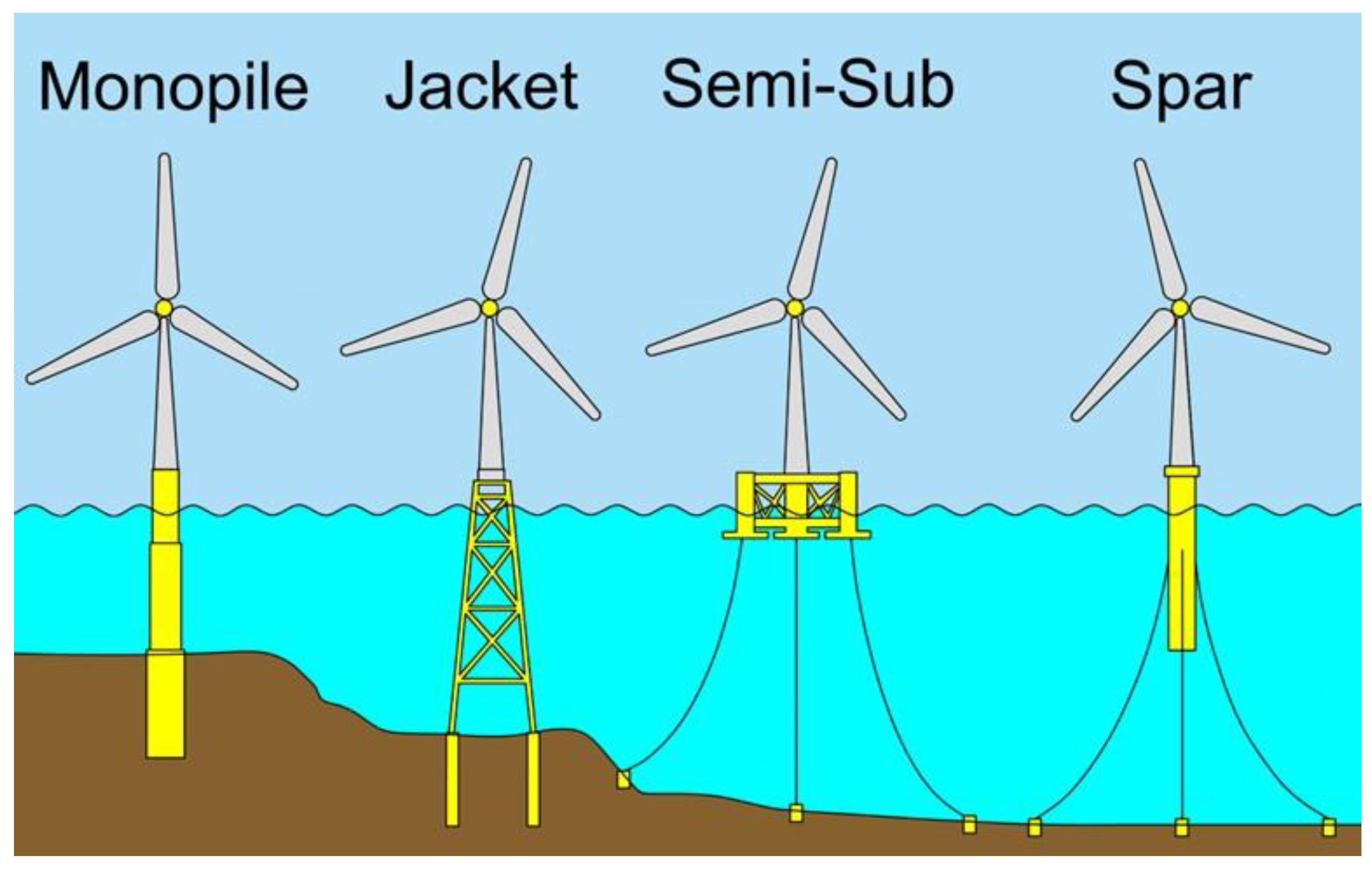

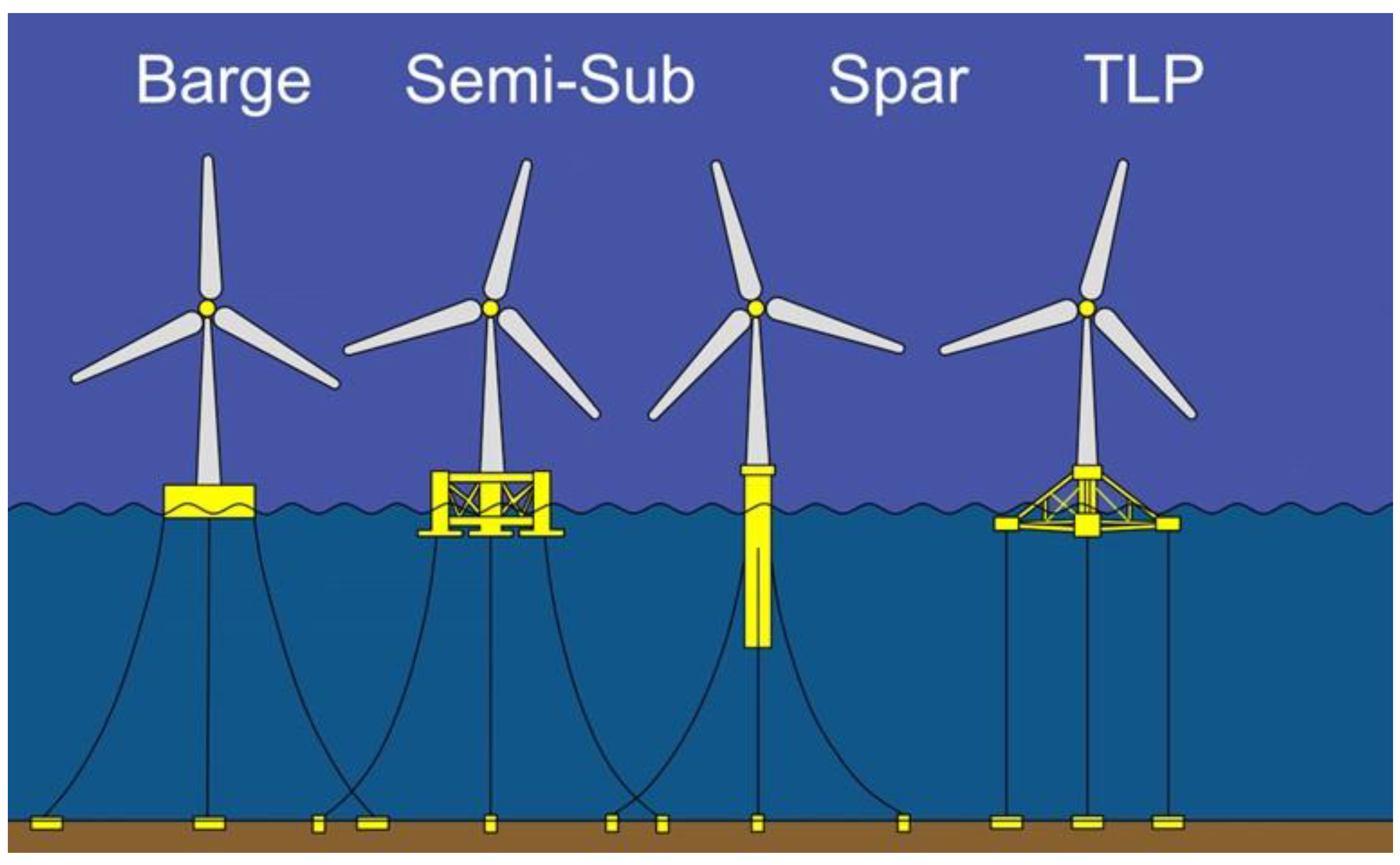

2.1. Worldwide floating wind concepts

2.1.1. Worldwide Spar-buoy floating-wind concepts

2.1.2. Worldwide Semi-submersible floating-wind concepts

2.1.3. Worldwide Barge floating wind concepts

2.1.4. Worldwide TLP floating wind concepts

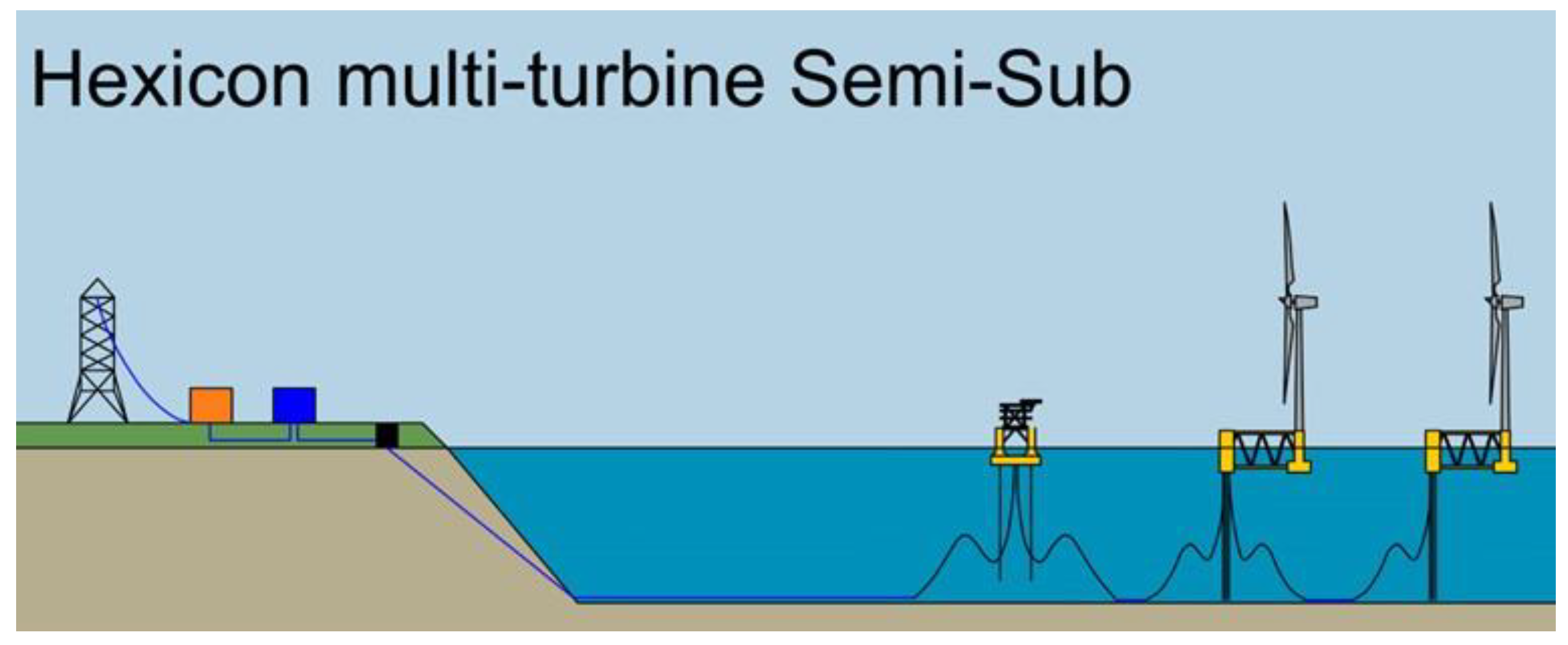

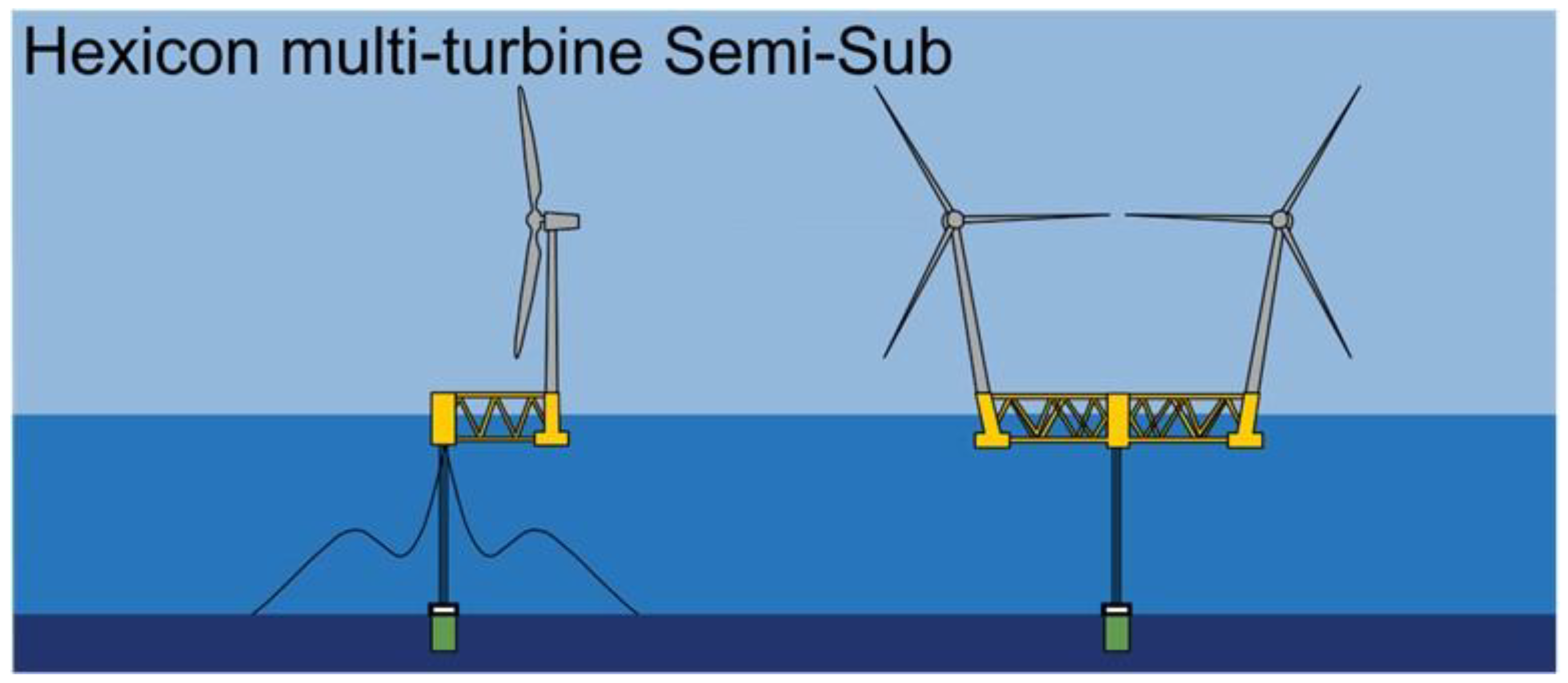

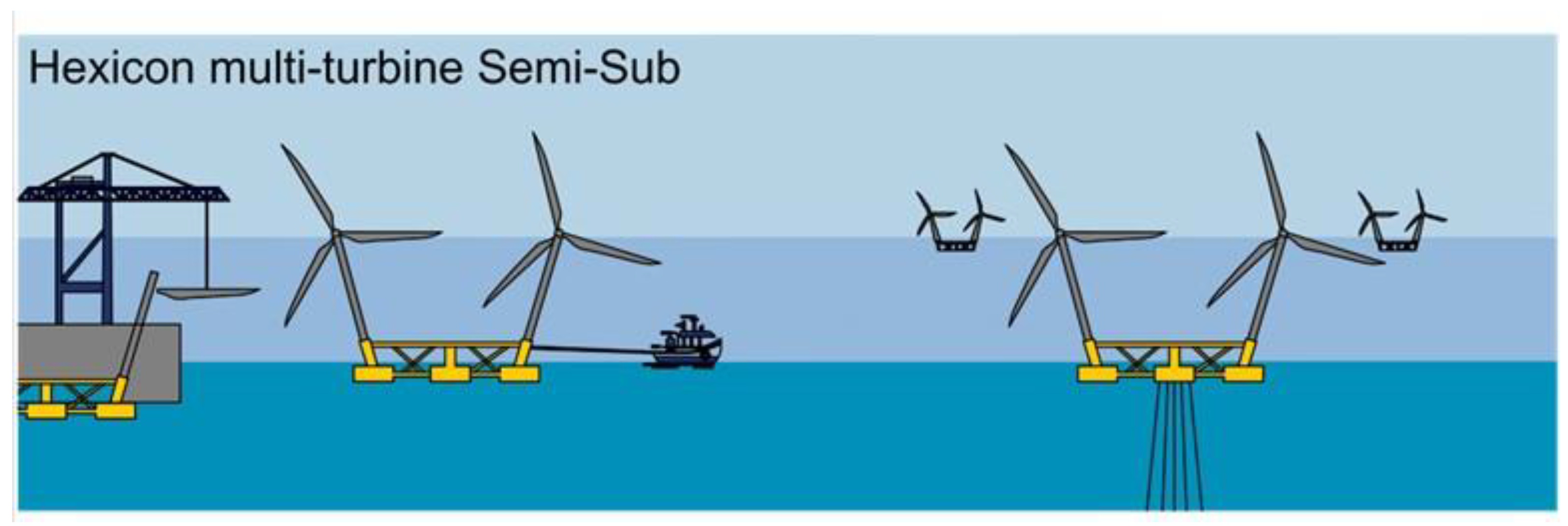

2.1.5. Worldwide multi-turbine floating wind concepts

2.2. Worldwide installed floating-wind projects

Worldwide largest contributing countries to the installed floating-wind projects

2.3. Worldwide planned floating-wind projects

Worldwide largest contributing countries to the planned floating wind projects (Table 3)

- The US has planned a floating wind power capacity of 2.45 GW, from 9 floating wind projects, in the period 2023-2027.

- Korea has planned a floating wind power capacity of 1.6 GW, from 7 floating wind projects, in the period 2020-2024.

- France has planned a floating wind power capacity of 113.5 MW, from 5 projects, in the period 2021-2022.

- Ireland has planned a floating wind power capacity of 106 MW, from 2 projects, in 2022.

- The UK has planned a floating wind power capacity of 105 MW, from 2 projects, in 2021.

- Spain has planned a floating wind power capacity of 103.2 MW, from 6 projects, in the period 2020-2021.

- Norway has planned a floating wind power capacity of 102.6 MW, from 5 projects, in the period 2020-2023.

- Japan has planned a floating wind power capacity of 28 MW, from 3 floating wind projects, in the period 2020-2023.

2.4. Further details on the worldwide installed and planned floating wind projects in the world (based on Table 2 and Table 3)

3. Results

3.1. Findings of Table 1 (Worldwide floating wind turbine concepts – Part 1)

3.2. Findings of Table 1 (Worldwide floating wind-turbine concepts – Part 2)

3.3. Findings of Table 1 (Worldwide floating wind-turbine concepts – Part 3)

3.4. Findings of Table 2 (Worldwide installed floating wind-turbine projects)

3.5. Findings of Table 3 (Worldwide planned floating wind-turbine projects)

3.6. Findings of Table 4 (Further details on the worldwide installed and planned floating wind projects – Part 1)

3.7. Findings of Table 4 (Further details on the worldwide installed and planned floating wind projects – Part 2)

3.8. Findings of Table 4 (Further details on the worldwide installed and planned floating wind projects – Part 3)

3.9. Findings of Table 4 (Further details on the worldwide installed and planned floating wind projects – Part 4)

3.10. Findings of Table 4 (Further details on the worldwide installed and planned floating wind projects Part 5)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lathigara, A., Zhao, F. 2022. Floating Offshore Wind – a Global Opportunity. Global Wind Energy Council.

- Tande, J. O., Wagenaar, J. W., Latour, M. I., Aubrun, S., Wingerde, A. V., Eecen, P., Andersson, M., Barth, S., McKeever, P., Cutululis, N. A. 2022. Proposal for European lighthouse project: Floating wind energy. EU SETWind project.

- Wind Europe. 2021. Scaling up Floating Offshore Wind Towards Competitiveness.

- Wind Europe. 2017. FLOATING OFFSHORE WIND ENERGY - A POLICY BLUEPRINT FOR EUROPE.

- Butterfield, S., Musial, W., Jonkman, J., Sclavounos, P. 2007. Engineering Challenges for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. NREL/CP-500-38776.

- ETIP Wind. 2020. FLOATING OFFSHORE WIND DELIVERING CLIMATE NEUTRALITY.

- Kurniawati, I., Beatriz, B., Varghese, R., Kostadinović, D., Sokol, I., Hemida, H., Alevras, P., Baniotopoulos, C. 2023. Conceptual Design of a Floating Modular Energy Island for Energy Independency: A Case Study in Crete. Energies 16, no. 16: 5921. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. G. 2017. Hywind – From idea to the world’s first wind farm based upon floaters. University of Bergen.

- ABB and ZERO. 2018. Floating offshore wind - Norway’s next offshore boom?

- Yildirir, V., Rusu, E., Onea, F. 2022. Wind Variation near the Black Sea Coastal Areas Reflected by the ERA5 Dataset. Inventions 7, no. 3: 57. [CrossRef]

- Yildirir, V., Rusu, E., Onea, F. 2022. Wind Energy Assessments in the Northern Romanian Coastal Environment Based on 20 Years of Data Coming from Different Sources. Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4249. [CrossRef]

- Girleanu, A., Onea, F., Rusu, E. 2021. The efficiency and coastal protection provided by a floating wind farm operating in the Romanian nearshore. Energy Reports 7, no.: 13-18. [CrossRef]

- Girleanu, A., Onea, F., Rusu, E. 2021. Assessment of the Wind Energy Potential along the Romanian Coastal Zone. Inventions 6, no. 2: 41. [CrossRef]

- Onea, F., Rusu, E., Rusu, L. 2021. Assessment of the Offshore Wind Energy Potential in the Romanian Exclusive Economic Zone. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 9, no. 5: 531. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A., Onea, F., Rusu, E. 2020. Study Concerning the Expected Dynamics of the Wind Energy Resources in the Iberian Nearshore. Energies 13, no. 18: 4832. [CrossRef]

- Onea, F., Ruiz, A., Rusu, E. 2020. An Evaluation of the Wind Energy Resources along the Spanish Continental Nearshore. Energies 13, no. 15: 3986. [CrossRef]

- Raileanu, A. B., Onea, F., Rusu, E. 2020. Implementation of Offshore Wind Turbines to Reduce Air Pollution in Coastal Areas—Case Study Constanta Harbor in the Black Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8, no. 8: 550.

- Onea, F., Rusu, E. 2019. An Assessment of Wind Energy Potential in the Caspian Sea. Energies 12, no. 13: 2525. [CrossRef]

- Onea, F., Rusu, E. 2016. Efficiency assessments for some state-of-the-art wind turbines in the coastal environments of the Black and the Caspian seas. Energy Exploration & Exploitation 34, no. 2: 217-234. [CrossRef]

- Raileanu, A., Onea, F., Rusu, E. 2015. Assessment of the wind energy potential in the coastal environment of two enclosed seas. OCEANS’15 MTS/IEEE GENOVA. [CrossRef]

- Onea, F., Raileanu, A., Rusu, E. 2015. Evaluation of the Wind Energy Potential in the Coastal Environment of Two Enclosed Seas. Advances in Meteorology 2015, no.: 1-14. [CrossRef]

- ABSG Consulting Inc. 2021. Floating Offshore Wind Turbine Development Assessment. BOEM, stage of publication (accepted).

- Jakobsen, E. G., Ironside, N. 2021. OCEANS UNLOCKED - A FLOATING WIND FUTURE. Available online: https://www.cowi.com/insights/oceans-unlocked-a-floating-wind-future (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Equinor. N.d. Hywind Tampen. Available online: https://www.equinor.com/energy/hywind-tampen (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Equinor. N.d. Hywind Scotland. Available online: https://www.equinor.com/energy/hywind-scotland (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Baltscheffsky, H. 2021. JOIN THE FUTURE. Available online: https://www.utilityeda.com/wp-content/uploads/Wed_Session-8-a_Hexicon-AB_Henrik-Baltscheffsky_Offshore-Wind-Power.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Kubiat, U., Lemon, M. 2020. Drivers for and Barriers to the Take-up of Floating Offshore Wind Technology: A Comparison of Scotland and South Africa. Energies 13, no. 21: 5618. [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Y., Chuang, T. C., Zhao, C., Johanning, L. 2022. Dynamic Response of an Offshore Floating Wind Turbine at Accidental Limit States—Mooring Failure Event. Applied Sciences 12, no. 3: 1525. [CrossRef]

- Kosasih, K. M. A., Suzuki, H., Niizato, H., Okubo, S. 2020. Demonstration Experiment and Numerical Simulation Analysis of Full-Scale Barge-Type Floating Offshore Wind Turbine. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8, no. 11: 880. [CrossRef]

- Möllerström, E. 2019. Wind Turbines from the Swedish Wind Energy Program and the Subsequent Commercialization Attempts—A Historical Review. Energies 12, no. 4: 690. [CrossRef]

- Borg, M., Jensen, M. W., Urquhart, S., Andersen, M. T., Thomsen, J. B., Stiesdal, H. 2020. Technical Definition of the Tetra Spar Demonstrator Floating Wind Turbine Foundation. Energies 13, no. 18: 4911. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S., Zhang, L., Shi, W., Wang, B., Li, X. 2021. Dynamic Responses for Wind Float Floating Offshore Wind Turbine at Intermediate Water Depth Based on Local Conditions in China. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 9, no. 10: 1093. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, T., Liu, Y. 2020. Dynamic Response Analysis of a Semi-Submersible Floating Wind Turbine in Combined Wave and Current Conditions Using Advanced Hydrodynamic Models. Energies 13, no. 21: 5820. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Kim, M. H. 2022. Review of Recent Offshore Wind Turbine Research and Optimization Methodologies in Their Design. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, no. 1: 28. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Chuang, Z., Wang, K., Li, X., Chang, X., Hou, L. 2022. Structural Parametric Optimization of the VOLTURNUS-S Semi-Submersible Foundation for a 15 MW Floating Offshore Wind Turbine. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, no. 9: 1181. [CrossRef]

- Qu, X., Yao, Y. 2022. Numerical and Experimental Study of Hydrodynamic Response for a Novel Buoyancy-Distributed Floating Foundation Based on the Potential Theory. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, no. 2: 292. [CrossRef]

- Mathern, A., Von der Haar, C., Marx, S. 2021. Concrete Support Structures for Offshore Wind Turbines: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Trends. Energies 14, no. 7: 1995. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H., Ha, Y. J., Cho, S. G., Lim, C. H., Kim, K. W. 2022. A Numerical Study on the Performance Evaluation of a Semi-Type Floating Offshore Wind Turbine System According to the Direction of the Incoming Waves. Energies 15, no. 15: 5485. [CrossRef]

- Ghigo, A., Cottura, L., Caradonna, R., Bracco, G., Mattiazzo, G. 2020. Platform Optimization and Cost Analysis in a Floating Offshore Wind Farm. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8, no. 11: 835. [CrossRef]

- Bensalah, A., Barakat, G., Amara, Y. 2022. Electrical Generators for Large Wind Turbine: Trends and Challenges. Energies 15, no. 18: 6700. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, C. J., Hinrichs, J. C., Murphy, J. 2019. Uncertainty in the Physical Testing of Floating Wind Energy Platforms’ Accuracy versus Precision. Energies 12, no. 3: 435. [CrossRef]

- Petracca, E., Faraggiana, E., Ghigo, A., Sirigu, M., Bracco, G., Mattiazzo, G. 2022. Design and Techno-Economic Analysis of a Novel Hybrid Offshore Wind and Wave Energy System. Energies 15, no. 8: 2739. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. D., Shin, H. 2020. The Effect of the Second-Order Wave Loads on Drift Motion of a Semi-Submersible Floating Offshore Wind Turbine. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8, no. 11: 859. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guillamón, A., Kaushik, D., Cutululis, N. A., Molina-García, A. 2019. Offshore Wind Power Integration into Future Power Systems: Overview and Trends. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 7, no. 11: 399. [CrossRef]

- Rickert, Christopher., Parambil, A. M. T., Leimeister, M. 2022. Conceptual Study and Development of an Autonomously Operating, Sailing Renewable Energy Conversion System. Energies 15, no. 12: 4434. [CrossRef]

- Baita-Saavedra, E., Cordal-Iglesias, D., Filgueira-Vizoso, A., Morató, À., Lamas-Galdo, I., Álvarez-Feal, C., Carral, L., Castro-Santos, L. 2020. An Economic Analysis of An Innovative Floating Offshore Wind Platform Built with Concrete: The SATH® Platform. Applied Sciences 10, no. 11: 3678. [CrossRef]

- González, J., Payán, M., Santos, J., Gonzalez, A. 2021. Optimal Micro-Siting of Weathervaning Floating Wind Turbines. Energies 14, no. 4: 886. [CrossRef]

- Walia, D., Schünemann, P., Hartmann, H., Adam, F., Großmann, J. 2021. Numerical and Physical Modeling of a Tension-Leg Platform for Offshore Wind Turbines. Energies 14, no. 12: 3554. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Ren, Y., Shi, W., Li, X. 2022. Investigation on a Large-Scale Braceless-TLP Floating Offshore Wind Turbine at Intermediate Water Depth. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, no. 2: 302. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R. 2022. Economic Analysis of Renewable Power-to-Gas in Norway. Sustainability, 14, 16882. [CrossRef]

- Lamei, A., Hayatdavoodi, M. 2020. On motion analysis and elastic response of floating offshore wind turbines. Journal of Ocean Engineering and Marine Energy 6. [CrossRef]

- Renzi, E., Michele, S., Zheng, S., Jin, S., Greaves, D. 2021. Niche Applications and Flexible Devices for Wave Energy Conversion: A Review. Energies 14, no. 20: 6537. [CrossRef]

- Solomin, E., Sirotkin, E., Cuce, E., Selvanathan, S. P., Kumarasamy, S. 2021. Hybrid Floating Solar Plant Designs: A Review. Energies 14, no. 10: 2751. [CrossRef]

- Skobiej, B., Niemi, A. 2022. Validation of copula-based weather generator for maintenance model of offshore wind farm. WMU J Marit Affairs 21, 73–87. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Xing, Y., Gaidai, O., Wang, K., Sandipkumar Patel, K., Dou, P., Zhang, Z. 2022. A novel multi-dimensional reliability approach for floating wind turbines under power production conditions. Front. Mar. Sci. Sec. Ocean Solutions Volume 9. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, H., Zhou, S., Ni, Y., Cai, C., Zhou, T., Li, Q. 2022. Review of Study on the Coupled Dynamic Performance of Floating Offshore Wind Turbines. Energies 15, no. 11: 3970. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E. C., Holcombe, A., Brown, S., Ransley, E., Hann, M., Greaves, D. 2023. Evolution of floating offshore wind platforms: A review of at-sea devices. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. Volume 183. 113416. ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Haces-Fernandez, F., Li, H., Ramirez, D. 2018. Assessment of the Potential of Energy Extracted from Waves and Wind to Supply Offshore Oil Platforms Operating in the Gulf of Mexico. Energies 11, no. 5: 1084. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, P., Crawford, C. 2023. Comparison of optimal power production and operation of unmoored floating offshore wind turbines and energy ships. Wind Energy Science. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. D., Dinh, M. C., Kim, H. M., Nguyen, T. T. 2021. Simplified Floating Wind Turbine for Real-Time Simulation of Large-Scale Floating Offshore Wind Farms. Energies 14, no. 15: 4571. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, V., Giannini, G., Cabral, T., López, M., Santos, P., Taveira-Pinto, F. 2022. Assessing the Effectiveness of a Novel WEC Concept as a Co-Located Solution for Offshore Wind Farms. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, no. 2: 267. [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Galeana, A., Brennan, F. 2021. Floating Offshore Vertical Axis Wind Turbines: Opportunities, Challenges and Way Forward. Energies 14, no. 23: 8000. [CrossRef]

- Ulazia, A., Nafarrate, A., Ibarra-Berastegi, G., Sáenz, J., Carreno-Madinabeitia, S. 2019. The Consequences of Air Density Variations Over Northeastern Scotland for Offshore Wind Energy Potential. Energies 12, no. 13: 2635. [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R., Früh, W. G. 2022. The transitional states of a floating wind turbine during high levels of surge. Renewable Energy. Volume 200. Pages 1469-1489. ISSN 0960-1481. [CrossRef]

- Díaz, H., Serna, J., Nieto, J., Guedes Soares, C. 2022. Market Needs, Opportunities, and Barriers for the Floating Wind Industry. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 10, no. 7: 934. [CrossRef]

- Venture. 2021. Power to X - TRANSFORMING RENEWABLE ELECTRICITY INTO GREEN PRODUCTS AND SERVICES. Concept paper.

- Andersen, M. T. 2016. Floating Foundations for Offshore Wind Turbines. Ph.D. Dissertation. Faculty of Engineering and Science, Aalborg University.

- North Sea Wind Power Hub. 2021. Integration of offshore wind. Discussion Paper #1.

- Codiga, D. A. 2018. PROGRESSION HAWAII OFFSHORE WIND. SCHLACK ITO.

- CADEMO Corporation. 2021. CADEMO Research and Demonstration Goals.

- Cabigan, M. K. 2022. Offshore Wind Development in an Integrated Energy Market in the North Sea: Defining regional energy policies in an integrated market and offshore wind infrastructure. Master thesis (NTNU).

- Beiter, P., Musial, W., Duffy, P., Cooperman, A., Shields, M., Heimiller, D., Optis, M. 2020. The Cost of Floating Offshore Wind Energy in California Between 2019 and 2032. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-5000-77384.

- INPEX CORPORATION. 2022. Goto Floating Wind Farm LLC Consortium Begins Offshore Wind Turbine Assembly (Towards Realization of Floating Offshore Wind Power Generator). Press Release.

- Belvasi, N., Conan, B., Schliffke, B., Perret, L., Desmond, C., Murphy, J., Aubrun, S. 2022. Far-Wake Meandering of a Wind Turbine Model with Imposed Motions: An Experimental S-PIV Analysis. Energies 15, no. 20: 7757. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L., Ikoma, T., Aida, Y., Masuda, K. 2021. Mean Wave Drift Forces on a Barge-Type Floating Wind Turbine Platform with Moonpools. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 9, no. 7: 709. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guillamón, A., Das, K., Cutululis, N. A., Molina-García, Á. 2019. Offshore Wind Power Integration into Future Power Systems: Overview and Trends. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 7, 399. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H. 2020. Introduction to the 1.2 GW Floating Offshore Wind Farm Project in the East Sea, Ulsan, Korea. University of Ulsan, KOREA.

- Lee, J., Xydis, G. 2023. Floating offshore wind project development in South Korea without government subsidies. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Ha, K., Kim, J. B., Yu, Y., Seo, H. 2021. Structural Modeling and Failure Assessment of Spar-Type Substructure for 5 MW Floating Offshore Wind Turbine under Extreme Conditions in the East Sea. Energies. 14., 6571. [CrossRef]

- TECHNIP ENERGIES. 2022. Technip Energies, Subsea 7, and SAMKANG M&T to Perform FEED for Gray Whale 3 Floating Offshore Wind Project in South Korea.

- Strivens, S., Northridge, E., Evans, H., Harvey, M., Camp, T., Terry, N. 2021. Floating Wind Joint Industry Project (Phase III summary report). CARBON TRUST.

- Tamarit, F., García, E., Quiles, E., Correcher, A. 2023. Model and Simulation of a Floating Hybrid Wind and Current Turbines Integrated Generator System, Part I: Kinematics and Dynamics. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 11, no. 1: 126. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, O. S., Singlitico, A., Proskovics, R., McDonagh, S., Desmond, C., Murphy, J. D. 2022. Dedicated large-scale floating offshore wind to hydrogen: Assessing design variables in proposed typologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. Volume 160. 112310. ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Ringvej Dahl, I., Tveitan, B. W., Cowan, E. C. 2022. The Case for Policy in Developing Offshore Wind: Lessons from Norway. Energies 15, no. 4: 1569. [CrossRef]

- Flagship. 2020. Floating offshore wind optimization for commercialization. Brochure.

- Aquatera. 2016. Dounreay-Tri Floating Wind Demonstration Project (Environmental Statement).

- Ideol. N, A. IDEOL Winning Solutions for Offshore Wind. Brochure.

- Brocklehurst, B., Bradshaw, K. 2022. AFLOWT Environmental Impact Assessment Scoping Report. SEAI.

- Emerald floating wind. 2021. Emerald Project: Foreshore License Application for Site Investigation Work – Risk Assessment for Annex IV Species.

- GICON. N.d. GICON SOF (A modular and cost competitive TLP Solution). Brochure.

- BOURBON. 2022. Bourbon Subsea Services awarded by EOLMED an EPCI contract for one of the first floating wind pilot farm in the French Mediterranean Sea. Press release.

- IGEOTEST. 2013. PROVENCE GRAND LARGE & MISTRAL FLOATING OFFSHORE WIND PROJECT. Brochure.

- COPERNICUS. 2018. MET-OCEAN STUDIES AND KEY ENVIRONMENTAL PARAMETERS FOR FLOATING OFFSHORE WIND TECHNOLOGY. Brochure.

- EOLFI. 2016. GROIX & Belle-Ile floating wind turbines, Signature of a new phase at NAVEXPO. Press release.

- Nair, R. J. Towing of Floating Wind Turbine Systems. Master's thesis. UIT University.

- Voltà, L. 2021. Self-Alignment on Single Point Moored Downwind Floater – The PivotBuoy® Concept. EERA Deep Wind.

- Margheritini, L., Rialland, A., Sperstad, I. B. 2015. THE CAPITALISATION POTENTIAL FOR PORTS DURING THE DEVELOPMENT OF MARINE RENEWABLE ENERGY. Beppo.

- RWE Offshore Wind GmbH. 2023. Demo SATH has achieved a key project milestone with the offshore installation. Press release.

- EOLFI. N, A. EOLFI, A member of the Shell Group. Brochure.

- IRENA. 2019. Innovation landscape for a renewable-powered future: Solutions to integrate variable renewables. International Renewable Energy Agency. ISBN 978-92-9260-111-9.

| Type | Concept | Designer | Hull Material |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spar-buoy | Hywind Toda Hybrid Spar |

Equinor Toda |

Steel or concrete Steel and concrete hybrid |

| Fukushima FORWARD Advanced Spar |

JMU | Steel | |

| SeaTwirl | SeaTwirl | Steel | |

| Stiesdal TetraSpar | Stiesdal | Steel | |

| Semi-submersible | WindFloat Fukushima FORWARD compact semi-submersible |

Principle Power MES |

Steel Steel |

| Fukushima FORWARD V-shape semi-Submersible |

MHI | Steel | |

| VolturnUS | University of Maine | Concrete | |

| Sea Reed | Naval Energies | Steel, concrete, or hybrid | |

| Cobra semi-spar | Cobra | Concrete | |

| OO-Star | Iberdrola | Concrete | |

| Hexafloat | Saipem | Steel | |

| Eolink | Eolink | Steel | |

| SCD nezzy | SCD Technology | Concrete | |

| Nautilus | NAUTILUS Floating Solutions | Steel | |

| Tri-Floater | GustoMSC | Steel | |

| TrussFloat | DOLFINES | Steel | |

| Barge | Ideol Damping Pool Barge Saitec SATH (Swinging Around Twin Hull) |

Ideol Saitec |

Concrete or steel Concrete |

| Tension leg platform | SBM TLP PivotBuoy TLP |

SBM Offshore X1 Wind |

Steel Steel |

| Gicon TLP | Gicon | Concrete | |

| Pelastar TLP | Glosten | Steel | |

| TLPWind TLP | Iberdrola | Steel | |

| Multi-turbine platform | Hexicon multi-turbine semi-submersible W2Power Floating Power Plant |

Hexicon EnerOcean Floating Power Plant |

Steel Steel Steel |

| Continent | Country, Location | Year, Turbine - Power | Project Name, Designer |

|---|---|---|---|

| North America | U.S., Maine | 2013, Renewegy 20 kW | VolturnUS 1:8, University of Maine |

| Asia | Japan, Goto Japan, Fukue |

2013, Hitachi 2 MW downwind 2015, Hitachi 2 MW downwind |

Kabashima, Toda Sakiyama, Toda |

| Japan, Fukushima | 2013, 66kV - 25MVA Floating Substation |

Fukushima FORWARD Phase 1, Fukushima Offshore Wind Consortium |

|

| Japan, Fukushima | 2013, Hitachi 2 MW downwind |

Fukushima FORWARD Phase 1, Fukushima Offshore Wind Consortium |

|

| Japan, Fukushima | 2015, MHI 7 MW | Fukushima FORWARD Phase 2, Fukushima Offshore Wind Consortium |

|

| Japan, Fukushima | 2016, Hitachi 5 MW downwind |

Fukushima FORWARD Phase 2, Fukushima Offshore Wind Consortium |

|

| Japan, Kitakyushu | 2019, Aerodyn SCD 3 MW – 2 bladed |

Hibiki, Ideol | |

| Europe | Denmark, Lolland Norway, Karmøy |

2008, 33 kW 2009, Siemens 2.3 MW |

Poseidon 37 Demonstrator [58], Floating Power Plant Hywind Demo, Equinor |

| Portugal, Aguçadoura | 2011, Vestas 2 MW | WindFloat 1 (WF1), Principle Power | |

| Portugal, Viana do Castelo | 2020, MHI Vestas 3×8.4 MW | WindFloat Atlantic (WFA), PrinciplePower | |

| Sweden, Lysekil | 2015, 30 kW Vertical Axis Wind Turbine |

SeaTwirl S1, SeaTwirl | |

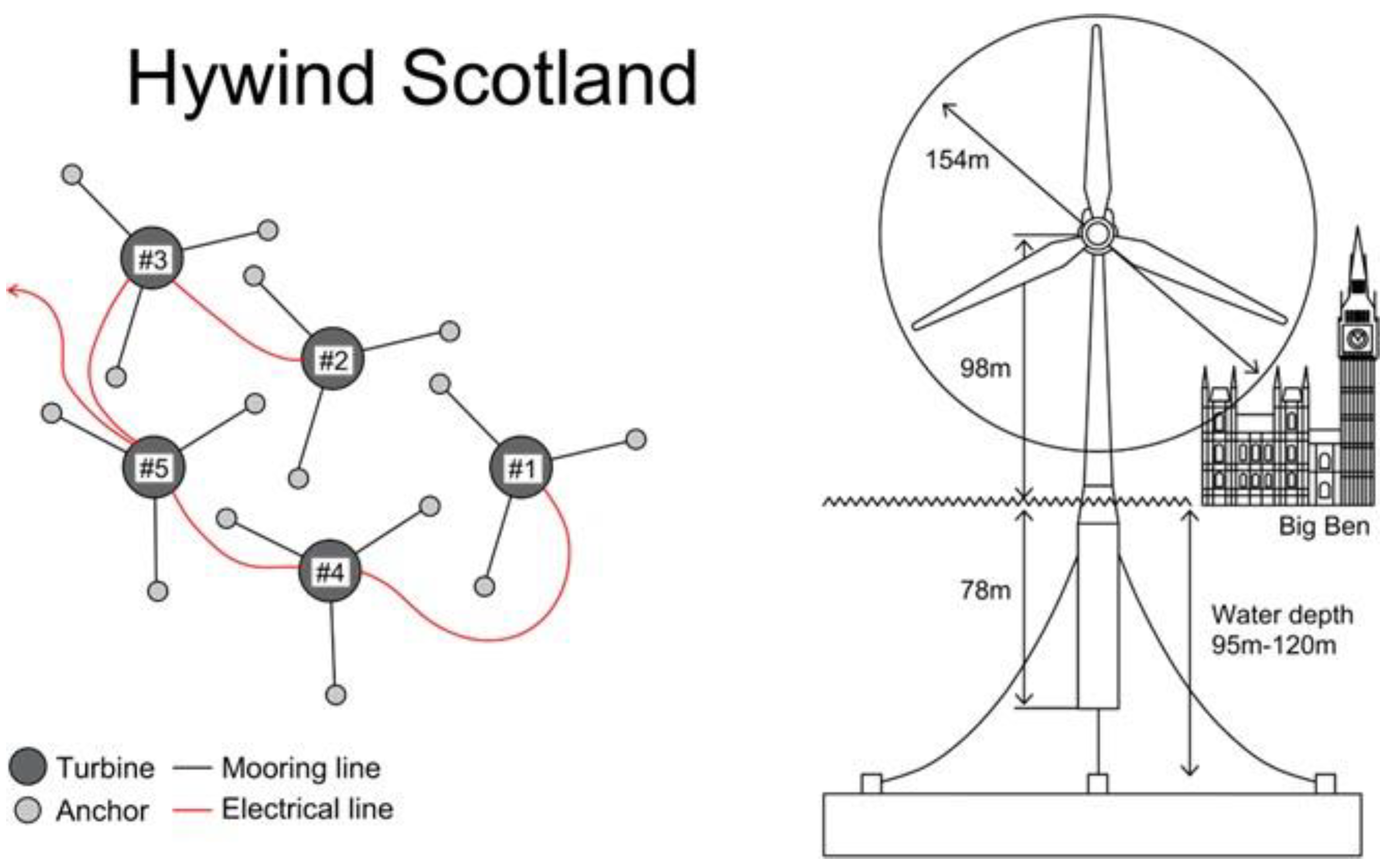

| UK, Peterhead | 2017, Siemens 5×6 MW | Hywind Scotland, Equinor | |

| UK, Dounreay |

2017, N/A 2×5 MW | Hexicon Dounreay Trì project [86], Hexicon |

|

| UK, Kincardineshire | 2020, MHI Vestas 2 MW (former WF1) & MHI Vestas 5×9.5MW |

Kincardine, Principle Power | |

| Spain, Gran Canaria Spain, Santander France, Le Croisic Germany, Baltic Sea |

2019, 2×100 kW twin-rotor 2020, Aeolos 30 kW 2018, Vestas 2 MW 2017, Siemens 2.3 MW |

W2Power 1:6 Scale, EnerOcean BlueSATH, Saitec Floatgen, Ideol Gicon SOF [90], GICON |

|

| Continent | Country - Location, Floating Substructure Design -Type | Year, Turbine - Power | Project Name, Designer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | Norway - Karmøy, Stiesdal TetraSpar - Spar Norway - Haugaland, SeaTwirl Spar |

2020, Siemens Gamesa 3.6 MW 2021, 1 MW Vertical Axis Wind Turbine |

TetraSpar Demo [82], Stiesdal SeaTwirl S2 [37], SeaTwirl |

||

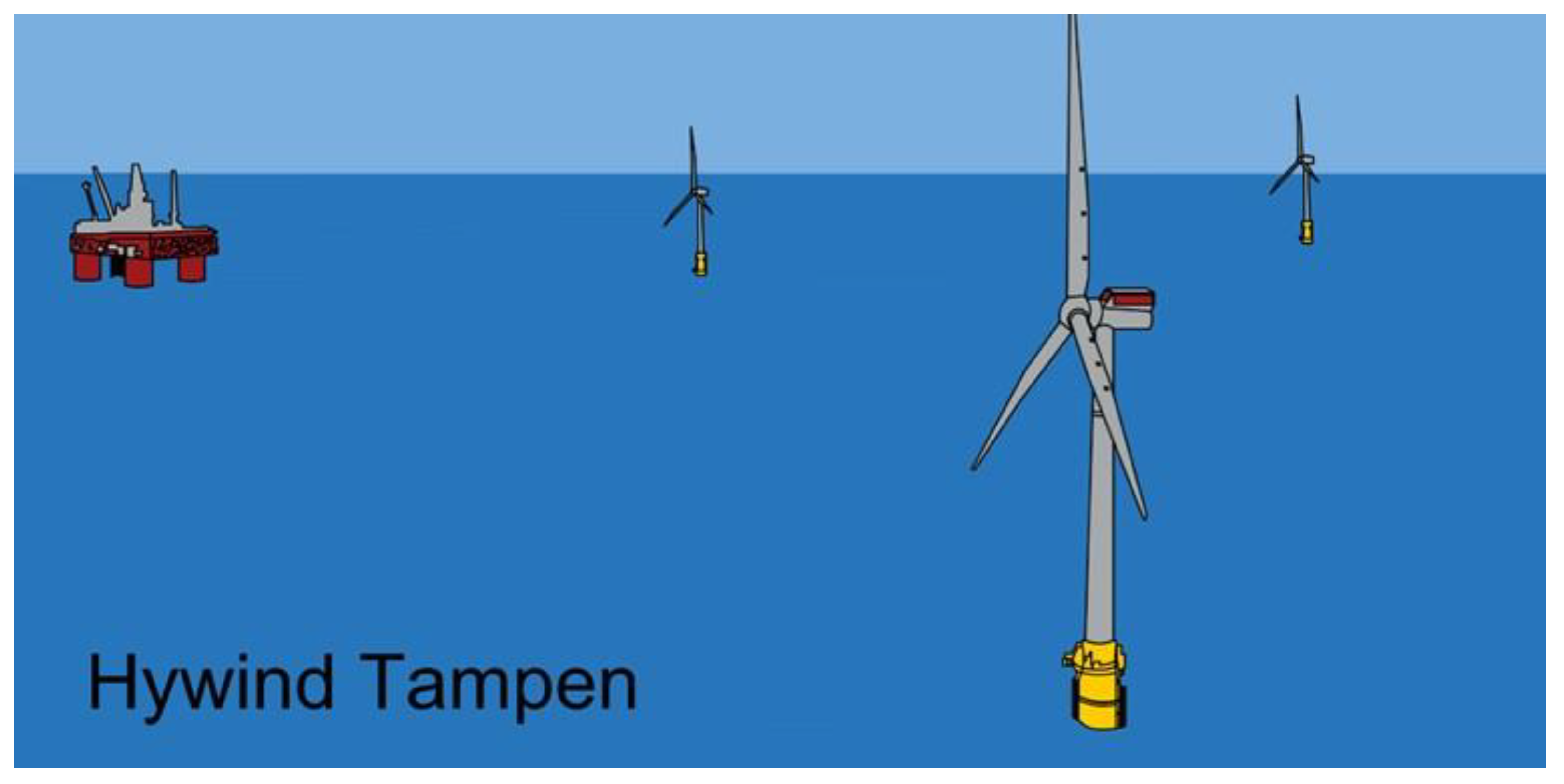

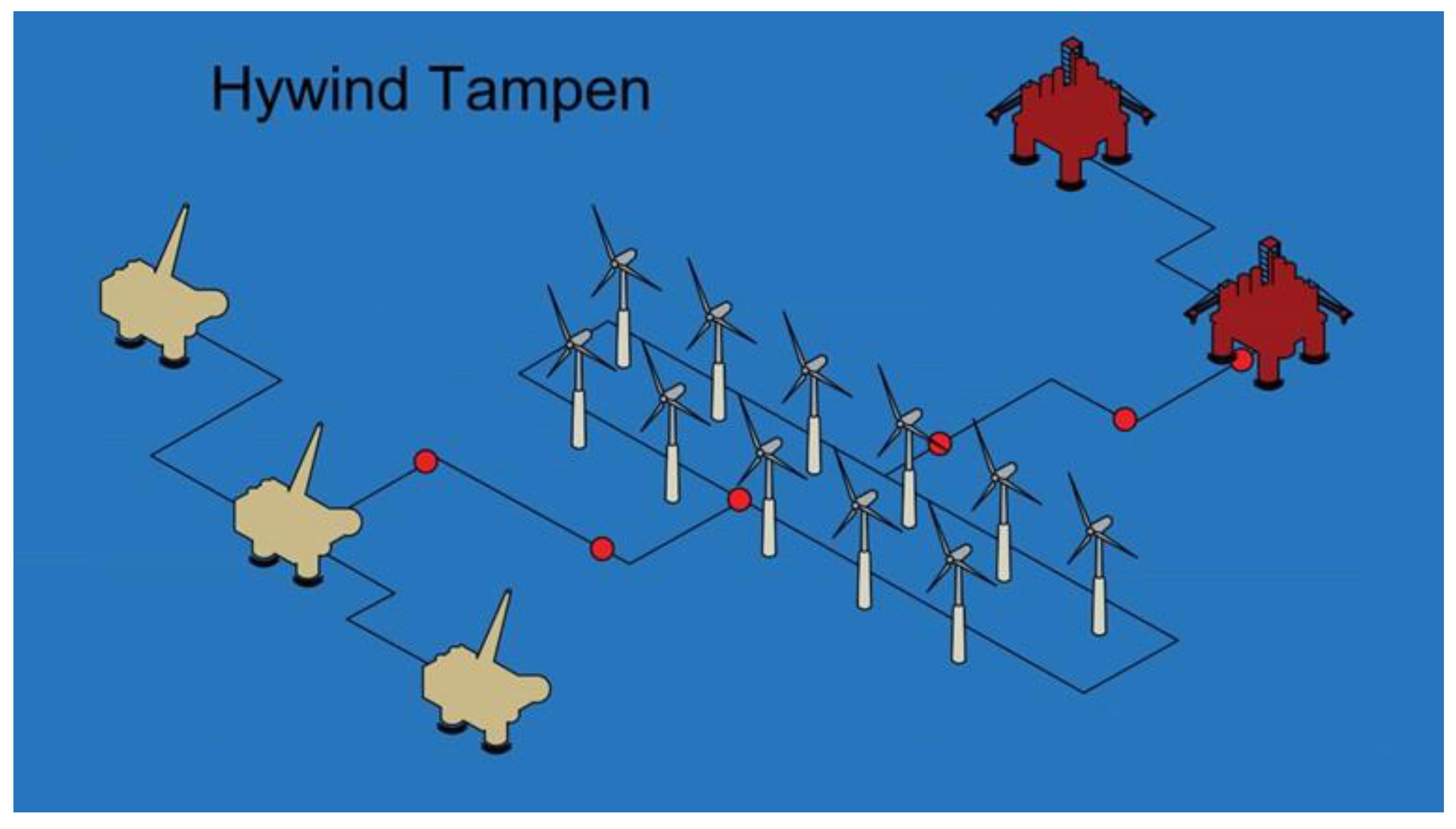

| Norway - Snorre & Gullfaks offshore fields, Hywind Spar | 2022, Siemens Gamesa 11×8 MW |

Hywind Tampen, Equinor [84] |

|||

| Norway - Karmøy, OO-Star semi-submersible | 2022, 10 MW | Flagship Demo, Iberdrola [85] |

|||

| Offshore Norway | 2023, N/A | NOAKA, N/A | |||

| Offshore UK, Ideol damping pool - barge | 2021, 100 MW | Atlantis Ideol [87], Ideol | |||

| Offshore UK, TLPWind TLP | N/A, 5 MW | TLPWind UK, Iberdrola | |||

| Ireland - Offshore Irish west coast, Hexafloat -semi-submersible |

2022, 6 MW | AFLOWT [88], Saipem | |||

| Ireland - Offshore Kinsale, WindFloat semi-submersible | N/A, 100 MW | Emerald [89], Principle Power |

|||

| France - Gruissan, Ideol Damping Pool, barge | 2021, Senvion 4×6.2 MW | EolMed [91], Ideol | |||

| France - Offshore Napoleon Beach, SBM TLP | 2021, Siemens Gamesa 3×8.4 MW |

Provence Grand Large (PGL) [92], SBM Offshore | |||

| France - Offshore Leucate-Le Barcarès, WindFloat semi-submersible |

2022, MHI Vestas 3×10 MW | Golfe du Lion (EFGL) [93], Principle Power | |||

| France - Offshore Brittany, Sea Reed semi-submersible | 2022, MHI Vestas 3×9.5 MW | Groix & Belle-Ile [94], Naval Energies | |||

| France - Offshore Le Croisic, Eolink semi-submersible | N/A, 5 MW | Eolink Demonstrator [95], Eolink | |||

| Spain - Offshore Canary Island, PivotBuoy TLP | 2020, Vestas 200kW | PivotBuoy 1:3 Scale [96], X1 Wind | |||

| Spain - Offshore Canary Islands, Cobra semi-spar | 2020, 5×5 MW | FLOCAN5 [97], Cobra | |||

| Spain - Offshore Basque, Saitec SATH | 2021, 2 MW | DemoSATH [98], Saitec | |||

| Spain - Offshore Gran Canaria, N/A |

N/A, 4×12.5 MW | Parque Eólico Gofio, Greenalia | |||

| Spain - Basque, N/A | N/A, 26 MW | Balea, N/A | |||

| Spain - Offshore Gran Canaria, N/A |

N/A | WunderHexicon, Hexicon | |||

| North America | U.S. - Monhegan Island, VolturnUS semi-submersible | 2023, 12 MW | New England Aqua Ventus I [22], University of Maine | ||

| U.S. - California, WindFloat semi-submersible | 2024, 100 – 150 MW | Red Wood Coast [65], Principle Power |

|||

| U.S. - Hawaii, WindFloat semi-submersible | 2025, 400 MW | Progression South [69], Principle Power | |||

| U.S. - California, SBM TLP/ Saitec SATH | 2025, 4×12 MW | CADEMO, SBM Offshore/ SAITEC [70] |

|||

| U.S. - California, N/A | 2026, 1 GW | Castle Wind, N/A | |||

| U.S. - Hawaii, WindFloat semi-submersible | 2027, 400 MW | AWH Oahu Northwest, Principle Power | |||

| U.S. - Hawaii, WindFloat semi-submersible | 2027, 400 MW | AWH Oahu South [71], Principle Power | |||

| U.S. - California, N/A | N/A | Diablo Canyon [72], N/A | |||

| U.S. - Massachusetts, N/A | N/A, 10+ MW | Mayflower Wind, Atkins | |||

| Asia | Japan - Goto, Toda Hybrid spar Offshore Japan, Ideol Damping Pool, barge |

2021, 22 MW 2023, N/A |

Goto City [73], Toda Acacia [74,75], Ideol |

||

| Offshore Japan, SCD NEZZY Semi-Submersible | N/A, Aerodyn SCD 6 MW – 2-bladed |

Nezzy Demonstrator [40], SCD Technology | |||

| Korea - Ulsan, Hexicon multi-turbine semi- submersible |

2022, 200 MW | Donghae TwinWind, Hexicon |

|||

| Korea - Ulsan, Semi- submersible |

2020, 750 kW | Ulsan 750kW Floating Demonstrator, University of Ulsan |

|||

| Korea - Ulsan, N/A | 2020, 5 MW | Ulsan Prototype [78,79], N/A | |||

| Korea - Ulsan, N/A | 2023, 500 MW | Gray Whale [80], N/A | |||

| Korea - Ulsan, Hywind Spar | 2024, 200 MW | KNOC (Donghae 1) [77,81], Equinor | |||

| Korea - Ulsan, WindFloat semi-submersible | N/A, 500 MW | KFWind, Principle Power | |||

| Korea - Ulsan, N/A | N/A, 200 MW | White Heron, N/A | |||

| Year | Project, Location, Distance To Shore |

Turbine & Power, Floating Substructure Design & Type, Designer |

Water Depth, Site Condition, Estimated Cost |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | HYWIND DEMO (ZEFYROS), Offshore Karmøy Norway, 10 km |

Siemens 2.3 MW, Hywind Spar, Equinor |

220 m, wind speed 40 m/s & max wave height 19 m, US $71 million |

|

| 2011 | WINDFLOAT 1 (WF1), Offshore Aguçadoura Portugal, 5 km |

Vestas 2 MW, WindFloat semi-submersible, Principle Power |

49 m, wind speed 31 m/s & max wave height 17 m, US $25 million |

|

| 2013 | VOLTURNUS 1:8, Offshore Castine Maine US, 330 m |

Renewegy 20 kW, VolturnUS, semi-submersible, University of Maine |

27.4 m, 50-year wind speed 14.1 m/s & 50-year significant wave height 1.3 m, US $12 million |

|

| SAKIYAMA, Offshore Sakiyama Fukue Island Japan, 5 km |

Hitachi 2 MW downwind, Haenkaze -Toda Hybrid spar, Toda |

100 m, 50-year wind speed 45.8 m/s & 50-year significant wave height 12.1 m, N/A |

||

| FUKUSHIMA FORWARD PROJECT phase I, Offshore Fukushima Japan, 23 km |

66kV - 25 MVA Floating Substation, Fukushima Kizuna - Advanced Spar, Japan Marine United Corporation (JMU) |

120 m, 50-year wind speed 48.3 m/s & 50-year significant wave height 11.71 m, US $157 million for all the phases of the project |

||

| FUKUSHIMA FORWARD PROJECT phase I, Offshore Fukushima Japan, 23 km |

Hitachi 2 MW downwind, Fukushima Mira - compact semi-submersible, Mitsui Engineering & Shipbuilding Co., Ltd. (MES) |

122-123 m, 50-year wind speed 48.3 m/s & 50-year significant wave height 11.71 m, US $157 million for all the phases of the project |

||

| 2015 | FUKUSHIMA FORWARD PROJECT, phase II, Offshore Fukushima Japan, 23 km |

MHI 7 MW, Fukushima Shimpuu - V-shape Semi-Submersible, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. (MHI) |

125 m, 50-year wind speed 48.3 m/s & 50-year significant wave height 11.71 m, US $157 million for all the phases of the project |

|

| SEATWIRL S1, Offshore Lysekil Sweden, N/A |

30 kW Vertical Axis Wind Turbine, SeaTwirl Spar, SeaTwirl |

35 m, wind speed 35 m/s, N/A |

||

| 2016 | FUKUSHIMA FORWARD PROJECT, phase II, Offshore Fukushima Japan, 23 km |

Hitachi 5 MW downwind, Fukushima Hamakaze - Advanced Spar, Japan Marine United Corporation (JMU) |

110-120 m, 50-year wind peed 48.3 m/s & 50-year significant wave height 11.71 m, US $157 million for all the phases of the project |

|

| 2017 | HYWIND SCOTLAND, Offshore Peterhead Scotland UK, 25 km |

Siemens 5×6 MW, Hywind Spar, Equinor |

95-120 m, average wind speed 10 m/s & average wave height 1.8 m, US $210 million |

|

| 2018 | FLOATGEN, Offshore Le Croisic France, 20 km |

Vestas 2 MW, Ideol Damping Pool-barge, Ideol |

33 m, wind speed 24.2 m/s & significant wave height 5.5 m, US $22.5 million |

|

| 2019 | HIBIKI, Offshore Kitakyushu Japan, 15 km |

Aerodyn SCD 3 MW - 2 bladed, Ideol Damping Pool - barge, Ideol |

55 m, typhoon-prone area, N/A |

|

| W2POWER 1:6 SCALE, Offshore Gran Canaria Spain, N/A |

2×100 kW twin-rotor, EnerOcean W2Power semi-submersible, EnerOcean |

N/A |

||

| 2020 | WINDFLOAT ATLANTIC (WFA), Offshore Viana do Castelo Portugal, 20 km |

MHI Vestas 3×8.4 MW, WindFloat semi-submersible, Principle Power |

85-100 m, N/A, US $134 million |

|

| KINCARDINE, Offshore Kincardineshire Scotland UK, 15 km |

MHI Vestas 2 MW (former WF1) - MHI Vestas 5×9.5 MW, WindFloat semi-submersible, Principle Power |

60-80 m, UK North Sea off the coast of Scotland, US $445 million |

||

| BLUESATH, Offshore Santander Spain, 800 m |

Aeolos 30 kW, Saitec SATH 1:6, Saitec |

N/A, Abra del Sardinero, US $2.2 million |

||

| TETRASPAR DEMO, Offshore Karmøy Norway, 10 km |

Siemens Gamesa 3.6 MW, Stiesdal TetraSpar - Spar, Stiesdal |

220 m, Near Zefyros (former Hywind Demo), US $20.5 million |

||

| 2021 | DEMOSATH, Offshore Basque Spain, 3.2 km |

2 MW, Saitec SATH, Saitec | 85 m, wind speed 12 m/s & significant wave height 2.8 m, $17.3 million |

|

| EOLMED, Offshore Gruissan Mediterranean Sea France, 15 km |

Senvion 4×6.2 MW, Ideol Damping Pool - barge, Ideol |

55 m, Mediterranean Sea, US $236.2 million |

||

| PROVENCE GRAND LARGE (PGL), Offshore Napoleon beach Mediterranean Sea France, 17 km |

Siemens Gamesa 3×8.4 MW, SBM TLP, SBM Offshore |

100 m, Mediterranean Sea, US $225 million |

||

| 2022 | HYWIND TAMPEN, Snorre & Gullfaks offshore fields Offshore Norway, 140 km |

Siemens Gamesa 11×8 MW, Hywind Spar, Equinor |

260-300 m, mean significant wave height 2.8 m, US $545 million |

|

| GOLFE DU LION (EFGL), Offshore Leucate-Le Barcarès Mediterranean Sea France, 16 km |

MHI Vestas 3×10 MW, WindFloat semi-submersible, Principle Power |

65-80 m, Mediterranean Sea, US $225 million |

||

| GROIX & BELLE-ILE, Offshore Brittany France, 22 km |

MHI Vestas 3×9.5 MW, Sea Reed semi-submersible, Naval Energies |

60 m, Atlantic Ocean off the coast of France, US $254 million |

||

| DONGHAE TWINWIND, Offshore Ulsan Korea, 62 km |

200 MW, Hexicon multi-turbine semi-submersible, Hexicon |

N/A | ||

| 2023 | NEW ENGLAND AQUA VENTUS I, Offshore Monhegan Island in the Gulf of Maine US, 4.8 km |

12 MW, VolturnUS - semi-submersible, University of Maine |

100 m, 50-year wind speed 40 m/s & 50-year significant wave height 10.2 m, US $100 million |

|

| 2024 | REDWOOD COAST, Offshore Humboldt County California US, 40 km |

100 – 150 MW, WindFloat semi-submersible, Principle Power |

600 m - 1 km, average annual wind speed 9-10 m/s, N/A |

|

| 2025 | CADEMO, Offshore Vandenberg California US, 4.8 km |

4×12 MW, SBM TLP/ Saitec SATH, SBM Offshore/Saitec |

85-96 m, average wind speed 8.5 m/s, N/A |

|

| 2026 | CASTLE WIND, Offshore Morro Bay California US, 48 km |

1 GW, N/A, N/A | 813 m-1.1 km, average wind speed 8.5 m/s, N/A |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).