Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. H. pylori status

2.3. Allergy and Asthma

2.4. Ethical considerations

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strachan, D.P. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ 1989, 299, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomfield, S.F.; Rook, G.A.; Scott, E.A.; Shanahan, F.; Stanwell-Smith, R.; Turner, P. Time to abandon the hygiene hypothesis: new perspectives on allergic disease, the human microbiome, infectious disease prevention and the role of targeted hygiene. Perspect Public Health 2016, 136, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, J.F. Revisiting the Hygiene Hypothesis in the Context of Autoimmunity. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 615192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarner, F.; Bourdet-Sicard, R.; Brandtzaeg, P.; Gill, H.S.; McGuirk, P.; van Eden, W.; Versalovic, J.; Weinstock, J.V.; Rook, G.A. Mechanisms of disease: the hygiene hypothesis revisited. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006, 3, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caraballo, L. The tropics, helminth infections and hygiene hypotheses. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2018, 14, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercelli, D. Mechanisms of the hygiene hypothesis--molecular and otherwise. Curr Opin Immunol 2006, 18, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, J.V.; Elliott, D.E. Helminths and the IBD hygiene hypothesis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009, 15, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, R.M.; Smits, H.H.; McSorley, H.J. Modulation of Host Immunity by Helminths: The Expanding Repertoire of Parasite Effector Molecules. Immunity 2018, 49, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panelli, S.; Epis, S.; Cococcioni, L.; Perini, M.; Paroni, M.; Bandi, C.; Drago, L.; Zuccotti, G.V. Inflammatory bowel diseases, the hygiene hypothesis and the other side of the microbiota: Parasites and fungi. Pharmacol Res 2020, 159, 104962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.S.; Aviles-Santa, M.L.; Freedman, N.D.; Perreira, K.M.; Garcia-Bedoya, O.; Kaplan, R.C.; Daviglus, M.L.; Graubard, B.I.; Talavera, G.A.; Thyagarajan, B.; et al. Associations of Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A seropositivity with asthma in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL): addressing the hygiene hypothesis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2021, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferle, P.I.; Kramer, A. Helicobacter pylori-infection status and childhood living conditions are associated with signs of allergic diseases in an occupational population. Eur J Epidemiol 2008, 23, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaser, M.J.; Chen, Y.; Reibman, J. Does Helicobacter pylori protect against asthma and allergy? Gut 2008, 57, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, I.C.; Dehzad, N.; Reuter, S.; Martin, H.; Becher, B.; Taube, C.; Muller, A. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 3088–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetti, E.; Leonardi, S.; Lanzafame, A.; Garozzo, M.T.; Filippelli, M.; Tomarchio, S.; Ferrara, V.; Salpietro, C.; Pulvirenti, A.; Francavilla, R.; et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and atopic diseases: is there a relationship? A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 17635–17647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugule, I.; Karklina, D.; Remberga, S.; Rumba-Rozenfelde, I. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Risk Factors in Relation to Allergy in Children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2017, 20, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness-Jensen, E.; Langhammer, A.; Hveem, K.; Lu, Y. Helicobacter pylori in relation to asthma and allergy modified by abdominal obesity: The HUNT study in Norway. World Allergy Organ J 2019, 12, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.T.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; Bai, C.Q.; Ling, C.H.; Yuan, F.L. The Protective Effects of Helicobacter pylori Infection on Allergic Asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2021, 182, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, M.P.; Bilotta, M.; Vaira, D.; Manca, A.; Massarelli, G.; Leandro, G.; Atzei, A.; Pisanu, G.; Graham, D.Y.; Realdi, G. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in shepherds. Dig Dis Sci 1999, 44, 1161–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmas, C.; Gabriele, F.; Conchedda, M.; Bortoletti, G.; Ecca, A.R. Causality or coincidence: may the slow disappearance of helminths be responsible for the imbalances in immune control mechanisms? J Helminthol 2003, 77, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricardi, P.M. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: controversial aspects of the 'hygiene hypothesis'. Clin Exp Immunol 2010, 160, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiotani, A.; Miyanishi, T.; Kamada, T.; Haruma, K. Helicobacter pylori infection and allergic diseases: epidemiological study in Japanese university students. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008, 23, e29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, C.; Asbjornsdottir, H.; Birgisdottir, A.; Sigurjonsdottir, R.B.; Gunnbjornsdottir, M.; Gislason, D.; Olafsson, I.; Cook, E.; Jogi, R.; Gislason, T.; et al. The effect of infectious burden on the prevalence of atopy and respiratory allergies in Iceland, Estonia, and Sweden. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007, 120, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibman, J.; Marmor, M.; Filner, J.; Fernandez-Beros, M.E.; Rogers, L.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; Blaser, M.J. Asthma is inversely associated with Helicobacter pylori status in an urban population. PLoS One 2008, 3, e4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holster, I.L.; Vila, A.M.; Caudri, D.; den Hoed, C.M.; Perez-Perez, G.I.; Blaser, M.J.; de Jongste, J.C.; Kuipers, E.J. The impact of Helicobacter pylori on atopic disorders in childhood. Helicobacter 2012, 17, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, C.; Anderson, W.J.; Reid, T.S.; Godden, D.J. Childhood exposure to infection and risk of adult onset wheeze and atopy. Thorax 2000, 55, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radon, K.; Windstetter, D.; Eckart, J.; Dressel, H.; Leitritz, L.; Reichert, J.; Schmid, M.; Praml, G.; Schosser, M.; von Mutius, E.; et al. Farming exposure in childhood, exposure to markers of infections and the development of atopy in rural subjects. Clin Exp Allergy 2004, 34, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, M.P.; Malaty, H.M.; Graham, D.Y.; Fanciulli, G.; Delitala, G.; Realdi, G. Risk Factors Associated with Helicobacter pylori Infection among Children in a Defined Geographic Area. Clin Infect Dis 2002, 35, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dore, M.P.; Fanciulli, G.; Tomasi, P.A.; Realdi, G.; Delitala, G.; Graham, D.Y.; Malaty, H.M. Gastrointestinal symptoms and Helicobacter pylori infection in school-age children residing in Porto Torres, Sardinia, Italy. Helicobacter 2012, 17, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaneva, M.; Darlenski, R. The link between atopic dermatitis and asthma- immunological imbalance and beyond. Asthma Res Pract 2021, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dore, M.P.; Massidda, M.; Meloni, G.F.; Soro, S.; Pes, G.M.; Graham, D.Y. The Association of Childhood Asthma and Helicobacter pylori Infection in Sardinia. Archives of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Asthma management and prevention for adults and children older than 5 years. A pocket guide for health professionals. ; 2019.

- Yuan, C.; Adeloye, D.; Luk, T.T.; Huang, L.; He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ye, X.; Yi, Q.; Song, P.; Rudan, I.; et al. The global prevalence of and factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2022, 6, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, Q.A.; Pittet, L.F.; Curtis, N.; Zimmermann, P. Antibiotic exposure and adverse long-term health outcomes in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2022, 85, 213–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Tarassishin, L.; Eisele, C.; Rendon, A.; Debebe, A.; Hawkins, K.; Hillenbrand, C.; Agrawal, M.; Torres, J.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; et al. Breastfeeding Is Associated with Lower Likelihood of Helicobacter Pylori Colonization in Babies, Based on a Prospective USA Maternal-Infant Cohort. Dig Dis Sci 2022, 67, 5149–5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunet, N.; Peleteiro, B.; Bastos, J.; Correia, S.; Marinho, A.; Guimaraes, J.T.; La Vecchia, C.; Barros, H. Child day-care attendance and Helicobacter pylori infection in the Portuguese birth cohort Geracao XXI. Eur J Cancer Prev 2014, 23, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.D.; Oliver, B.G.G. Sexual dimorphism in chronic respiratory diseases. Cell Biosci 2023, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekpruke, C.D.; Silveyra, P. Sex Differences in Airway Remodeling and Inflammation: Clinical and Biological Factors. Front Allergy 2022, 3, 875295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raherison, C.; Hamzaoui, A.; Nocent-Ejnaini, C.; Essari, L.A.; Ouksel, H.; Zysman, M.; Prudhomme, A.; groupe de travail 'Femmes et poumons' de la, S. [Woman's asthma throughout life: Towards a personalized management?]. Rev Mal Respir 2020, 37, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardolo, F.L.M.; Levra, S.; Sprio, A.E.; Bertolini, F.; Carriero, V.; Gallo, F.; Ciprandi, G. Asthma in the Real-World: The Relevance of Gender. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2020, 181, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidyatillake, N.T.; Allen, K.J.; Lodge, C.J.; Dharmage, S.C.; Abramson, M.J.; Simpson, J.A.; Lowe, A.J. The impact of breastfeeding on lung development and function: a systematic review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2013, 9, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waidyatillake, N.T.; Dharmage, S.C.; Allen, K.J.; Lodge, C.J.; Simpson, J.A.; Bowatte, G.; Abramson, M.J.; Lowe, A.J. Association of breast milk fatty acids with allergic disease outcomes-A systematic review. Allergy 2018, 73, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orczyk-Pawilowicz, M.; Lis-Kuberka, J. The Impact of Dietary Fucosylated Oligosaccharides and Glycoproteins of Human Milk on Infant Well-Being. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, X.; Bloom, M.S.; Qian, Z.; Rolling, C.A.; Xian, H.; Lin, S.; Li, S.; Chen, G.; et al. Association of Breastfeeding and Air Pollution Exposure With Lung Function in Chinese Children. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e194186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshammer, H.; Hutter, H.P. Breast-Feeding Protects Children from Adverse Effects of Environmental Tobacco Smoke. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, M.; Wijga, A.H.; Brunekreef, B.; Smit, H.A.; de Jongste, J.C.; Aalberse, R.C.; Hoekstra, M.O.; Gerritsen, J.; Postma, D.S. Effects of pets on asthma development up to 8 years of age: the PIAMA study. Allergy 2009, 64, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuneit, J.; Seibold, A.M.; Apfelbacher, C.J.; Konstantinou, G.N.; Koplin, J.J.; La Grutta, S.; Logan, K.; Flohr, C.; Perkin, M.R.; Task Force "Overview of Systematic Reviews in Allergy Epidemiology " of the, E.I.G.o.E. The state of asthma epidemiology: an overview of systematic reviews and their quality. Clin Transl Allergy 2017, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtimäki, J.; Thorsen, J.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Hjelmso, M.; Shah, S.; Mortensen, M.S.; Trivedi, U.; Vestergaard, G.; Bonnelykke, K.; Chawes, B.L.; et al. Urbanized microbiota in infants, immune constitution, and later risk of atopic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021, 148, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.M.; Choo, K.E.; Noorizan, A.M.; Lee, Y.Y.; Graham, D.Y. Evidence against Helicobacter pylori Being Related to Childhood Asthma. J Infect Dis 2009, 199, 914–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farag, T.H.; Stoltzfus, R.J.; Khalfan, S.S.; Tielsch, J.M. Unexpectedly low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among pregnant women on Pemba Island, Zanzibar. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2007, 101, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farag, T.H.; Fahey, J.W.; Khalfan, S.S.; Tielsch, J.M. Diet as a factor in unexpectedly low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2008, 102, 1164–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, D.Y.; Yamaoka, Y.; Malaty, H.M. Contemplating the future without Helicobacter pylori and the dire consequences hypothesis. Helicobacter 2007, 12 Suppl 2, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, W.; Ege, M.J.; von Mutius, E. The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med 2006, 355, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, G. Association between Helicobacter pylori and asthma: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013, 25, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, K.W.; Lam, W.K.; Chan, K.N.; Hu, W.; Wu, A.; Kwok, E.; Zheng, L.; Wong, B.C.; Lam, S.K. Helicobacter pylori sero-prevalence in asthma. Respir Med 2000, 94, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soloski, M.J.; Poulain, M.; Pes, G.M. Does the trained immune system play an important role in the extreme longevity that is seen in the Sardinian blue zone? Front Aging 2022, 3, 1069415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, D.; Ang, M.; Sokollik, C.; Wu, T.; Abdullah, M.; Greenfield, L.; Fattouh, R.; Reardon, C.; Tang, M.; Diao, J.; et al. Helicobacter pylori inhibits dendritic cell maturation via interleukin-10-mediated activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway. J Innate Immun 2015, 7, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Hp 1 IgG < 0.21 (n=434) |

Hp IgG ≥ 0.21 (n=58) |

P-value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

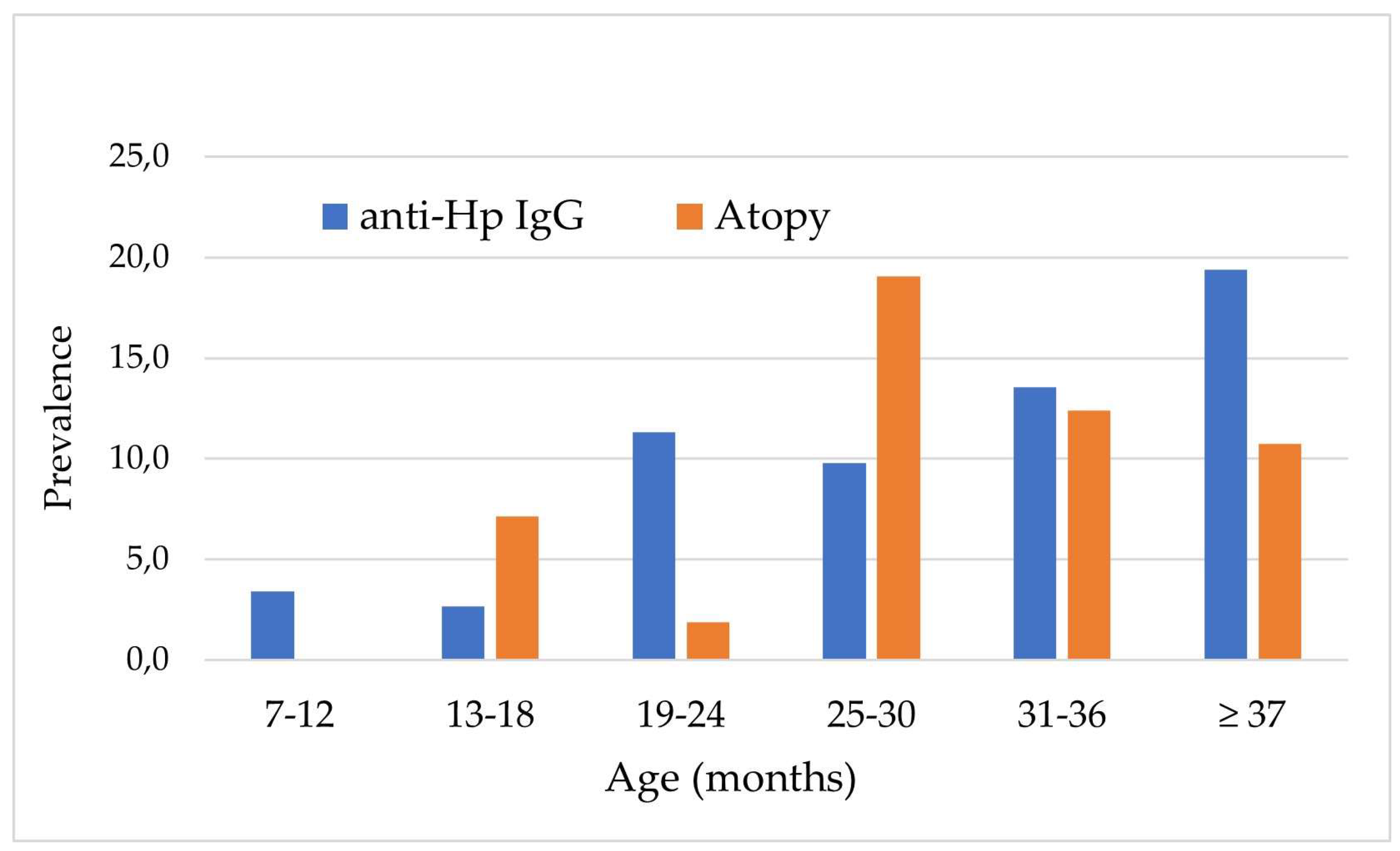

| Age (months), n (%) 7 ‒ 12 13 ‒ 18 19 ‒ 24 25 ‒ 30 31 ‒ 36 ≥ 37 |

58 (96.5) 73 (97.3) 47 (88.7) 46 (90.2) 102 (86.4) 108 (80.6) |

3 (4.9) 2 (2.7) 6 (11.3) 5 (9.8) 16 (13.6) 26 (19.4) |

0.002 |

| Sex, n (%) Female Male |

218 (90.8) 216 (85.7) |

22 (9.2) 36 (14.3) |

0.078 |

| Residence, n (%) Urban Rural |

369 (91.1) 65 (74.7) |

36 (8.9) 22 (25.3) |

<0.0001 |

| House size in m2, n (%) ≥ 100 < 100 |

226 (92.6) 208 (83.9) |

18 (7.4) 40 (16.1) |

0.003 |

| Breastfeeding, n (%) No < 6 months 6‒11 months ≥ 12 months |

197 (89.5) 188 (90.8) 33 (73.3) 16 (80.0) |

23 (10.5) 19 (9.2) 12 (26.7) 4 (20.0) |

0.409 |

| Ownership of animals, n (%) No Pets Farm animals |

358 (90.2) 76 (80.0) 16 (66.7) |

39 (9.8) 19 (20.0) 8 (33.3) |

0.006 |

| School, n (%) No Day care center School |

271 (93.2) 96 (84.7) 67 (97.1) |

49 (6.8) 7 (15.3) 2 (2.9) |

0.011 |

| Weight, n (%) Normal Reduced |

343 (87.1) 91 (92.9) |

51 (12.9) 7 (7.1) |

0.111 |

| Allergy and/or asthma, n (%) No Allergy Asthma Allergy and asthma |

397 (88.6) 9 (75.0) 28 (87.5) 0 (0.0) |

51 (11.4) 3 (25.0) 4 (12.5) 0 (0.0) |

0.374 |

| Variables | No atopy (n=448) | Atopy (n=44) | p-value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months), n (%) 7 ‒ 12 13 ‒ 18 19 ‒ 24 25 ‒ 30 31 ‒ 36 ≥ 37 |

59 (100.0) 70 (93.3) 51 (96.2) 42 (82.4) 105 (89.0) 121 (89.0) |

2 (3.3) 5 (6.7) 2 (3.8) 9 (17.6) 13 (11.0) 13 (9.7) |

0.001 |

|

Sex, n (%) Female Male |

222 (92.5) 226 (89.7) |

18 (7.5) 26 (10.3) |

0.420 |

|

Residence, n (%) Urban Rural |

368 (90.9) 80 (92.0) |

37 (9.1) 7 (8.0) |

0.482 |

|

House size, n (%) < 100 ≥ 100 |

215 (90.0) 233 (92.1) |

29 (11.9) 15 (6.0) |

0.406 |

|

Breastfeeding, n (%) No Yes |

197 (89.5) 251 (92.3) |

23 (10.5) 21 (7.7) |

0.025 |

|

Ownership of animals, n (%) No Yes |

361 (90.9) 87 (91.6) |

36 (9.1) 8 (8.4) |

0.827 |

|

School, n (%) No Yes |

297 (92.8) 151 (87.8) |

23 (7.2) 21 (12.2) |

0.063 |

|

H. pylori IgG < 0.21 ≥ 0.21 |

398 (91.7) 50 (86.2) |

36 (8.3) 8 (13.8) |

0.233 |

| Variables, n (%) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age < 24 months ≥ 24 months |

reference 1.70 (0.88‒3.30) |

reference 1.10 (0.41‒2.94) |

|

Sex Female Male |

reference 1.29 (0.69‒2.41) |

reference 2.17 (0.95‒4.44) |

|

Residence, n (%) Urban Rural |

reference 0.73 (0.30‒1.78) |

reference 1.46 (0.64‒3.35) |

|

Breastfeeding, n (%) No Yes |

reference 1.07 (1.57‒2.00) * |

reference 1.91 (0.75‒4.84) |

|

Ownership of animals No Yes |

reference 2.29 (1.26‒4.19) |

reference 0.65 (0.23‒1.86) |

|

School, n (%) No Yes |

reference 1.80 (0.96‒3.35) |

reference 1.58 (0.57‒4.39) |

|

Helicobacter pylori status negative positive |

reference 1.81 (0.80‒4.11) |

reference (0.22‒2.84) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).