Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Data gathering

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical methodology

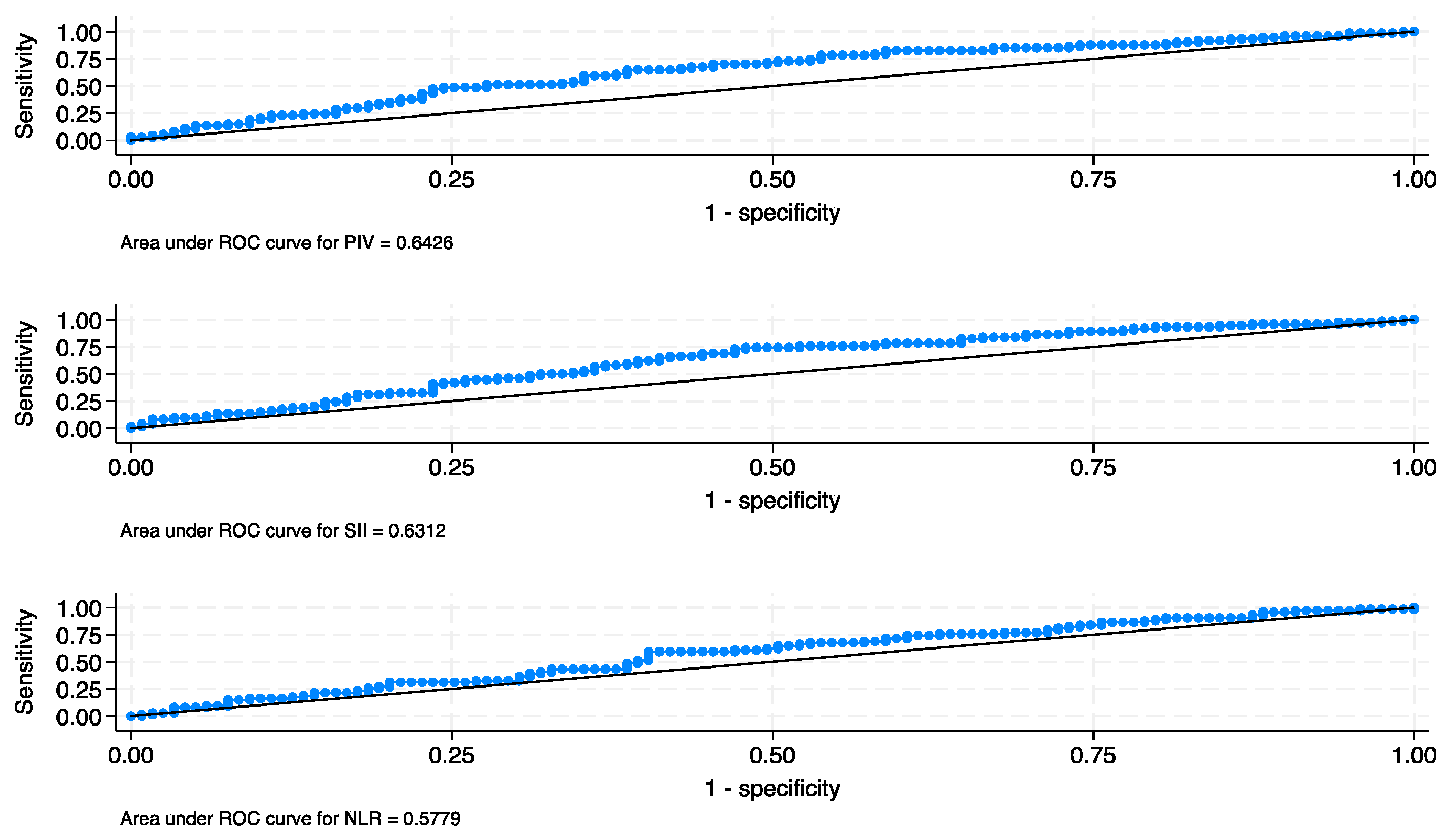

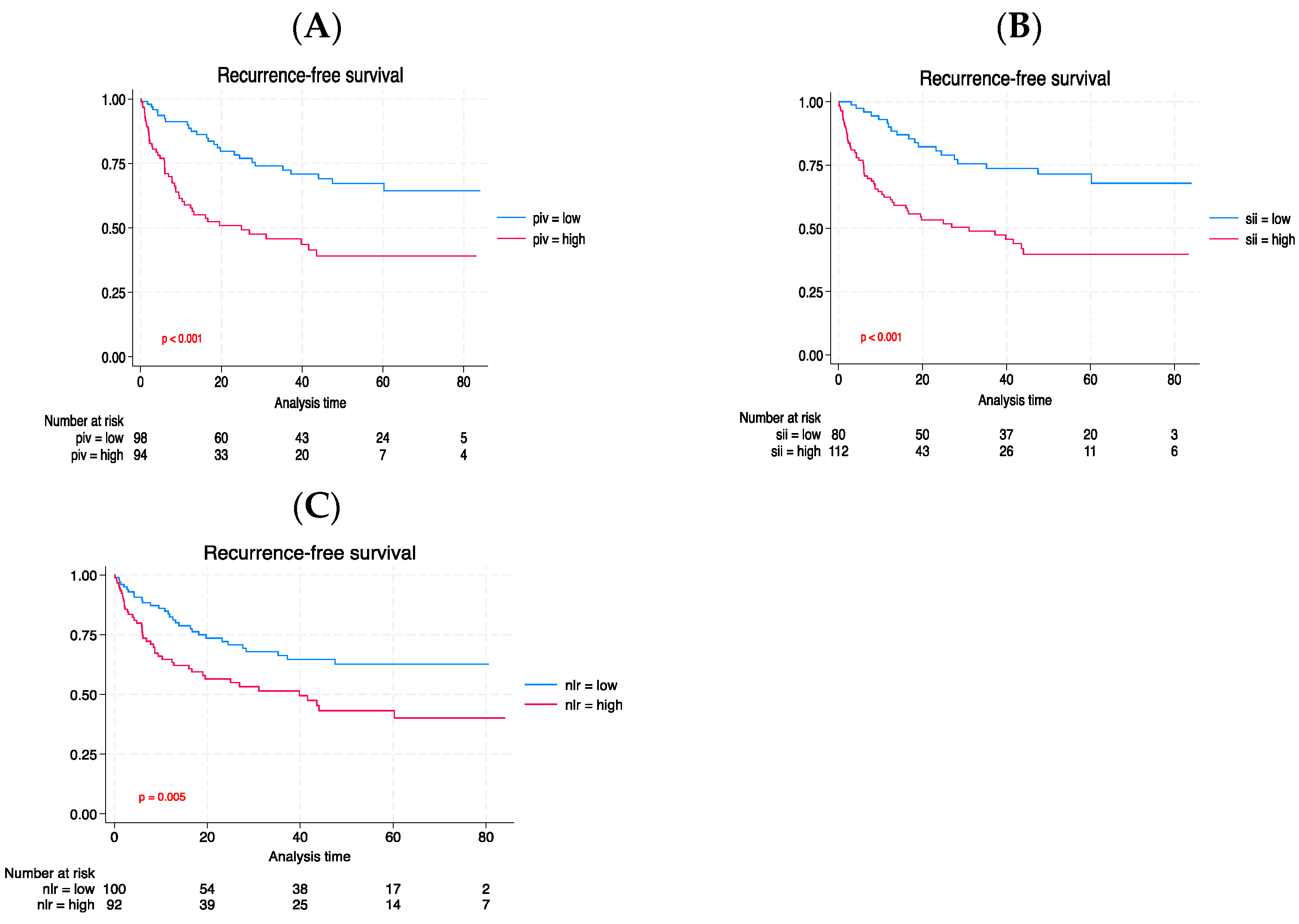

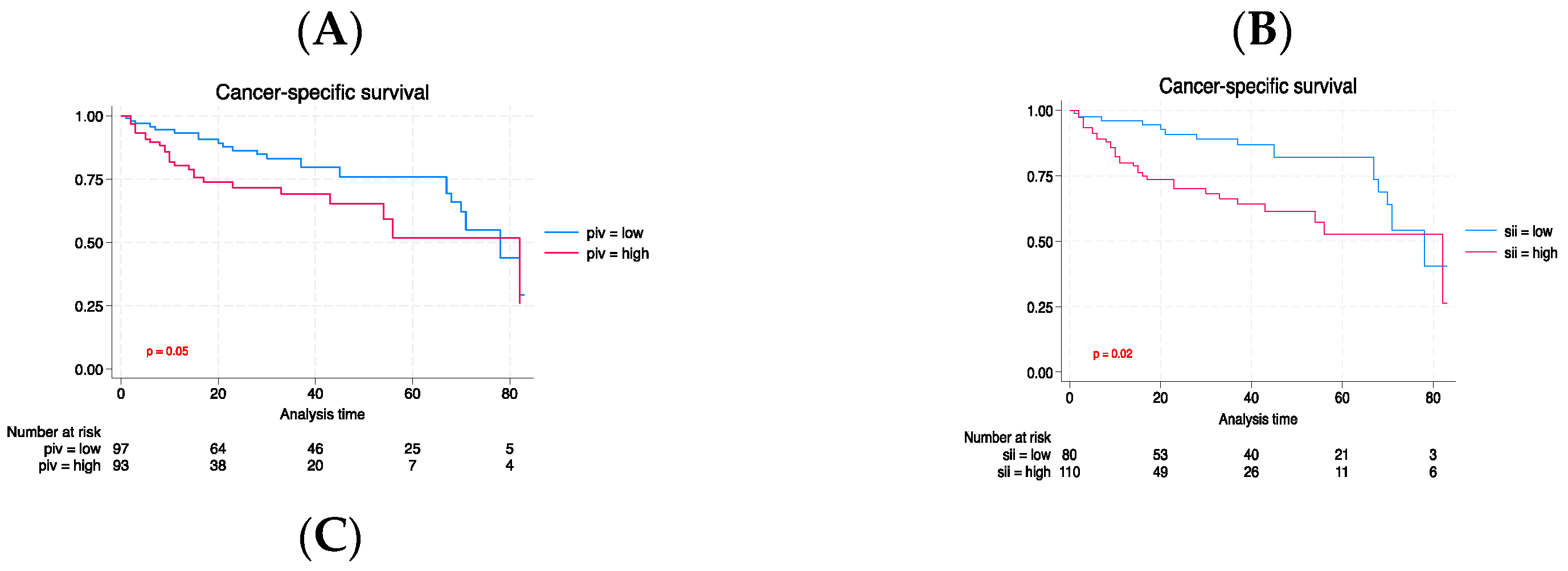

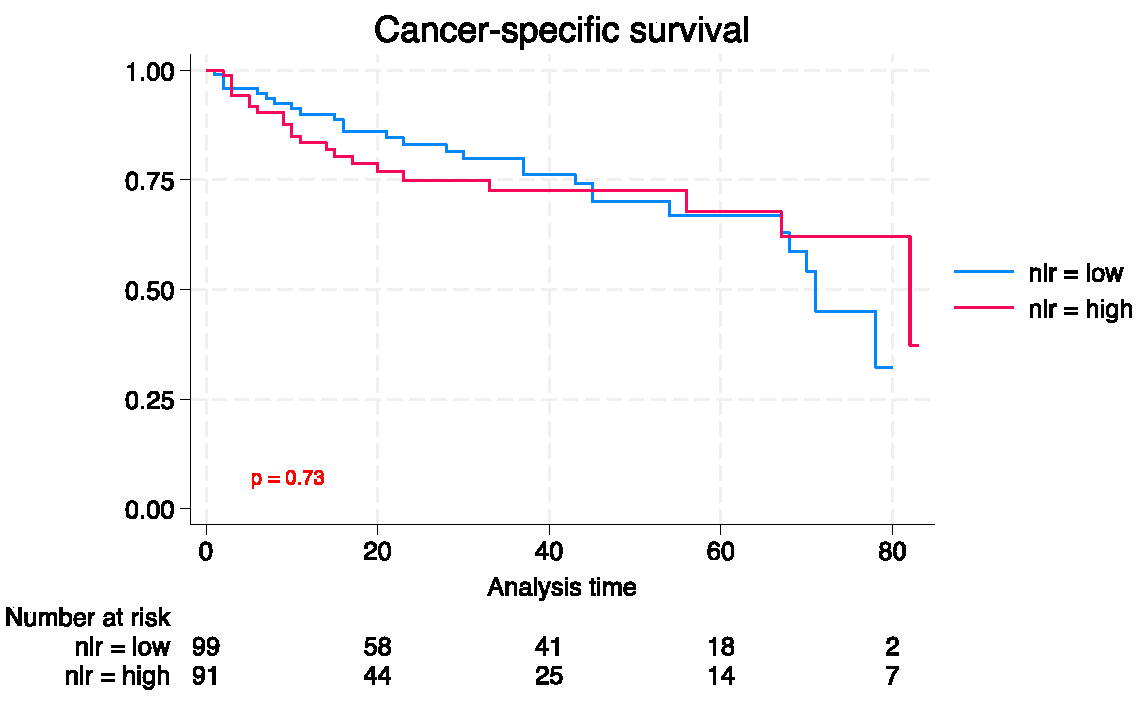

3. Results

3.1. Patient features

3.2. Oncological results

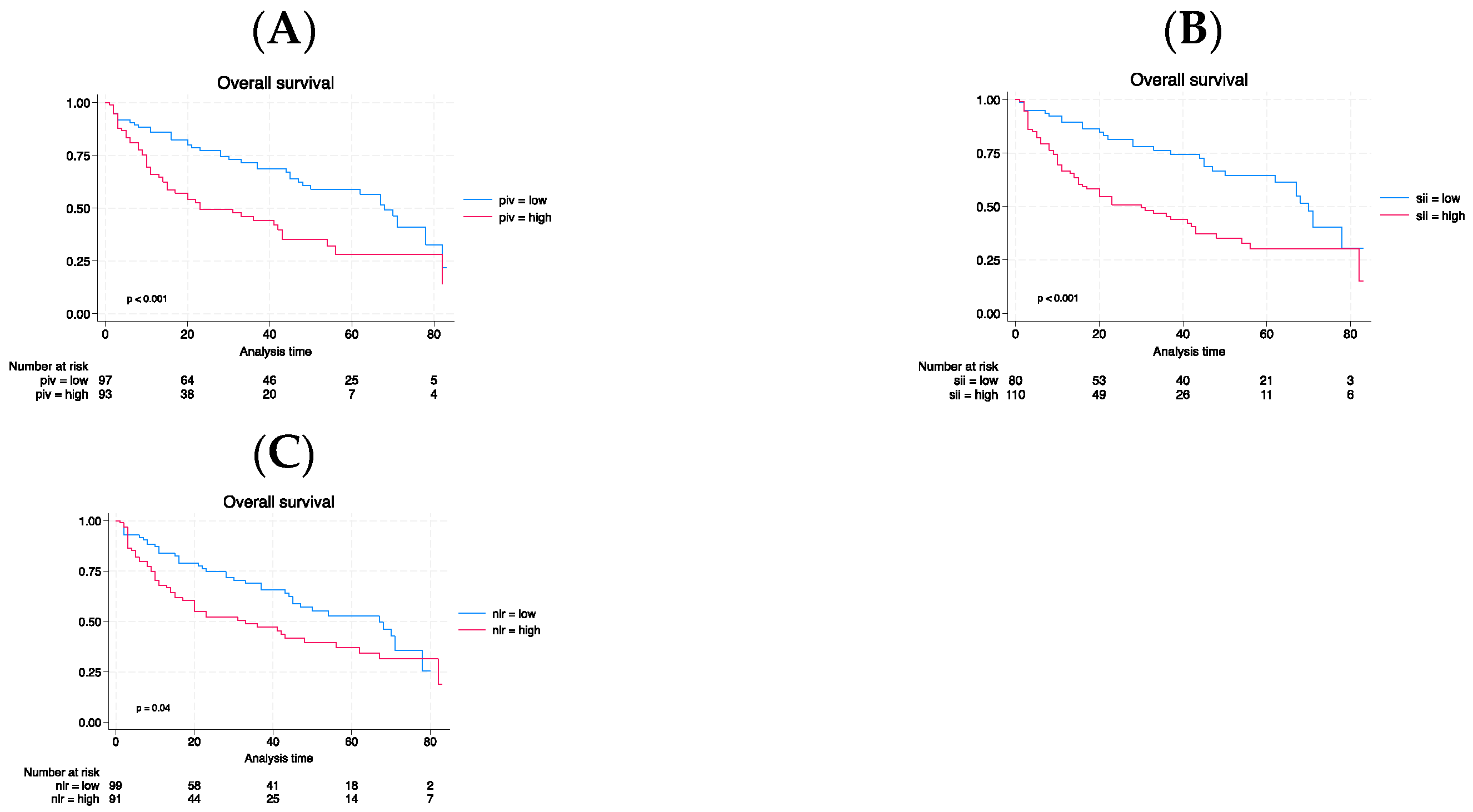

3.3. Long-term outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A., & Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 68(6), 394–424. [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, K. V., & Kohli, M. (2017). Management of Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Cancer and the Emerging Role of Immunotherapy in Advanced Urothelial Cancer. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 92(10), 1564–1582. [CrossRef]

- Witjes, J. A., Bruins, H. M., Cathomas, R., Compérat, E. M., Cowan, N. C., Gakis, G., Hernández, V., Linares Espinós, E., Lorch, A., Neuzillet, Y., Rouanne, M., Thalmann, G. N., Veskimäe, E., Ribal, M. J., & van der Heijden, A. G. (2021). European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2020 Guidelines. European urology, 79(1), 82–104. [CrossRef]

- Bassi, P., Ferrante, G. D., Piazza, N., Spinadin, R., Carando, R., Pappagallo, G., & Pagano, F. (1999). Prognostic factors of outcome after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: a retrospective study of a homogeneous patient cohort. The Journal of urology, 161(5), 1494–1497. [CrossRef]

- Stein, J. P., Lieskovsky, G., Cote, R., Groshen, S., Feng, A. C., Boyd, S., Skinner, E., Bochner, B., Thangathurai, D., Mikhail, M., Raghavan, D., & Skinner, D. G. (2001). Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 19(3), 666–675. [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, M. A., el-Mekresh, M. M., el-Baz, M. A., el-Attar, I. A., & Ashamallah, A. (1997). Radical cystectomy for carcinoma of the bladder: critical evaluation of the results in 1,026 cases. The Journal of urology, 158(2), 393–399. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 144(5), 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Gao, Y., Wu, Y., & Lin, H. (2020). Prognostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with urologic cancers: a meta-analysis. Cancer cell international, 20, 499. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X., Li, T., Dai, Y., & Li, J. (2019). Preoperative systemic inflammation score (SIS) is superior to neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as a predicting indicator in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC cancer, 19(1), 721. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J. P., Hua, X., Long, Z. Q., Zhang, W. W., Lin, H. X., & He, Z. Y. (2020). Erratum to prognostic value of skeletal muscle index and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio for lymph node-positive breast cancer patients after mastectomy. Annals of translational medicine, 8(7), 520. [CrossRef]

- Marchioni, M., Primiceri, G., Ingrosso, M., Filograna, R., Castellan, P., De Francesco, P., & Schips, L. (2016). The Clinical Use of the Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) in Urothelial Cancer: A Systematic Review. Clinical genitourinary cancer, 14(6), 473–484. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Gu, L., Chen, Y., Chong, Y., Wang, X., Guo, P., & He, D. (2021). Systemic immune-inflammation index is a promising non-invasive biomarker for predicting the survival of urinary system cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of medicine, 53(1), 1827–1838. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L., Yang, Y., Hu, X., Zhang, R., & Li, X. (2023). Prognostic value of the pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of translational medicine, 21(1), 79. [CrossRef]

- Russo, Pierluigi et al. “Is Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index a Real Non-Invasive Biomarker to Predict Oncological Outcomes in Patients Eligible for Radical Cystectomy?.” Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) vol. 59,12 2063. 22 Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Halabi, Susan et al. “Developing and Validating Risk Assessment Models of Clinical Outcomes in Modern Oncology.” JCO precision oncology vol. 3 (2019): PO.19.00068. [CrossRef]

- Kayar, Ridvan et al. “Pan-immune-inflammation value as a prognostic tool for overall survival and disease-free survival in non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer.” International urology and nephrology, 10.1007/s11255-023-03812-w. 29 Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jaehong, and Jong-Sup Bae. “Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Neutrophils in Tumor Microenvironment.” Mediators of inflammation vol. 2016 (2016): 6058147. [CrossRef]

- Lolli, Cristian et al. “Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts the clinical outcome in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer treated with sunitinib.” Oncotarget vol. 7,34 (2016): 54564-54571. [CrossRef]

- Auguste, Patrick et al. “The host inflammatory response promotes liver metastasis by increasing tumor cell arrest and extravasation.” The American journal of pathology vol. 170,5 (2007): 1781-92. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hao-Cheng et al. “Neutrophil elastase induces IL-8 synthesis by lung epithelial cells via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.” Journal of biomedical science vol. 11,1 (2004): 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L M et al. “MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis.” Cell vol. 103,3 (2000): 481-90. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Shile et al. “Effects of the Tumor-Leukocyte Microenvironment on Melanoma-Neutrophil Adhesion to the Endothelium in a Shear Flow.” Cellular and molecular bioengineering vol. 1,2-3 (2008): 189-200. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, Dagmar et al. “Platelet-derived nucleotides promote tumor-cell transendothelial migration and metastasis via P2Y2 receptor.” Cancer cell vol. 24,1 (2013): 130-7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Lei et al. “Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) before and after surgery in operable breast cancer patients.” Cancer biomarkers : section A of Disease markers vol. 28,4 (2020): 537-547. [CrossRef]

- Minami, Takafumi et al. “Identification of Programmed Death Ligand 1-derived Peptides Capable of Inducing Cancer-reactive Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes From HLA-A24+ Patients With Renal Cell Carcinoma.” Journal of immunotherapy (Hagerstown, Md. : 1997) vol. 38,7 (2015): 285-91. [CrossRef]

- Thommen, Daniela S et al. “A transcriptionally and functionally distinct PD-1+ CD8+ T cell pool with predictive potential in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 blockade.” Nature medicine vol. 24,7 (2018): 994-1004. [CrossRef]

- Ofner, Heidemarie et al. “Blood-Based Biomarkers as Prognostic Factors of Recurrent Disease after Radical Cystectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International journal of molecular sciences vol. 24,6 5846. 19 Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Xingxing et al. “The clinical use of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in bladder cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” International journal of clinical oncology vol. 22,5 (2017): 817-825. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jian-Hui et al. “Systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer.” World journal of gastroenterology vol. 23,34 (2017): 6261-6272. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yan et al. “Prognostic value of the pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis.” Annals of translational medicine vol. 7,18 (2019): 433. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Jie-Hui et al. “Prognostic role of systemic immune-inflammation index in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Oncotarget vol. 8,43 75381-75388. 29 Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Gorgel, Sacit Nuri et al. “Retrospective study of systemic immune-inflammation index in muscle invasive bladder cancer: initial results of single centre.” International urology and nephrology vol. 52,3 (2020): 469-473. [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, Nico C et al. “Impact of preoperative systemic immune-inflammation Index on oncologic outcomes in bladder cancer patients treated with radical cystectomy.” Urologic oncology vol. 40,3 (2022): 106.e11-106.e19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yi et al. “Prognostic value of pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with gastrointestinal cancers.” Journal of cellular physiology vol. 234,5 (2019): 5555-5563. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Yongfang, and Haiyan Wang. “Prognostic prediction of systemic immune-inflammation index for patients with gynecological and breast cancers: a meta-analysis.” World journal of surgical oncology vol. 18,1 197. 7 Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Bolin et al. “Prognostic impact of elevated pre-treatment systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) in hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis.” Medicine vol. 99,1 (2020): e18571. [CrossRef]

- Fucà, Giovanni et al. “The Pan-Immune-Inflammation Value is a new prognostic biomarker in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a pooled-analysis of the Valentino and TRIBE first-line trials.” British journal of cancer vol. 123,3 (2020): 403-409. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Xiaoyan et al. “Clinical utility of the pan-immune-inflammation value in breast cancer patients.” Frontiers in oncology vol. 13 1223786. 30 Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shariat, Shahrokh F et al. “Statistical consideration for clinical biomarker research in bladder cancer.” Urologic oncology vol. 28,4 (2010): 389-400. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total | Low PIV | High PIV | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=193 | N= 99 (51.3) | N = 94 (48.7) | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 78 (73-83) | 78 (73-83) | 79 (73-83) | 0.38 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.07 | |||

| Male | 154 (79.7) | 84 (84.8) | 70 (74.7) | |

| Female | 39 (20.2) | 15 (15.1) | 24 (25.5) | |

| Smoke, n (%) | 149 (77.2) | 83 (83.8) | 66 (70.2) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 31 (16.0) | 16 (16.1) | 15 (15.9) | 0.96 |

| Clinical T stage, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| cTa | 67 (34.7) | 41 (41.4) | 26 (27.6) | |

| cTis | 24 (12.4) | 18 (12.3) | 6 (11.7) | |

| cT1 | 49 (25.3) | 23 (25.1) | 26 (23.9) | |

| cT2 | 29 (15.0) | 14 (14.9) | 15 (14.1) | |

| cT3 | 18 (9.3) | 3 (9.2) | 15 (8.8) | |

| cT4 | 6 (3.1) | 0 (3.1) | 6 (2.9) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26 (24-29) | 26 (24-29) | 26 (24-28) | 0.39 |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | 0.27 | |||

| Open | 186 (96.3) | 94 (94.9) | 92 (97.8) | |

| Robot-assisted | 7 (3.6) | 5 (5.0) | 2 (2.1) | |

| Urinary diversion, n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| Ureterocutaneostomy | 21 (10.8) | 6 (6.0) | 15 (15.9) | |

| Ileal conduit | 148 (76.6) | 74 (78.2) | 74 (78.7) | |

| Orthotopic neobladder | 24 (12.4) | 19 (19.1) | 5 (5.3) | |

| Pathological T stage, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| pT0 | 14 (7.2) | 10 (10.1) | 4 (4.2) | |

| pTa | 10 (5.1) | (5.0) | 5 (5.3) | |

| pTis | 23 (11.9) | 17 (17.1) | 6 (6.3) | |

| pT1 | 26 (13.4) | 19 (19.1) | 7 (7.4) | |

| pT2a | 30 (15.5) | 16 (16.1) | 14 (14.8) | |

| pT2b | 5 (2.5) | 3 (3.0) | 2 (2.1) | |

| pT3a | 49 (25.3) | 22 (22.2) | 27 (28.7) | |

| pT3b | 8 (4.1) | 4 (3.0) | 5 (5.3) | |

| pT4a | 21 (10.8) | 4 (4.0) | 17 (18.0) | |

| pT4b | 7 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Lymph node, n (%) | 37 (19.1) | 11 (11.1) | 26 (27.6) | 0.004 |

| LVI, n (%) | 128 (66.3) | 54 (54.5) | 74 (78.7) | < 0.001 |

| Locally advanced disease, n (%) | 102 (52.8) | 37 (37.3) | 65 (69.1) | < 0.001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 40 (20.7) | 15 (15.1) | 25 (26.6) | 0.05 |

| Progressive disease, n (%) | 61 (31.6) | 22 (22.2) | 39 (41.4) | 0.004 |

| Cancer-related deaths, n (%) | 96 (49.7) | 44 (44.4) | 52 (55.3) | 0.131 |

| Any-cause deaths, n (%) | 52 (26.9) | 26 (26.2) | 26 (27.6) | 0.827 |

| Lymph node | Advanced Tumor grading | Locoregionally extended state | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

| PIV (Reference:low) | |||||||||

| High | 1.84 | 0.76, 4.47 | 0.17 | 2.87 | 1.36, 6.04 | 0.005 | 3.30 | 1.60, 6.77 | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.14 | 0.33, 3.88 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.28, 1.99 | 0.576 | 1.00 | 0.39, 2.57 | 0.98 |

| Smoke (Reference: no) | |||||||||

| Smoke | 0.59 | 0.23, 1.50 | 0.27 | 0.93 | 0.37, 2.33 | 0.890 | 1.48 | 0.59, 3.70 | 0.39 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | |||||||||

| Female | 0.56 | 0.19, 1.60 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.10, 0.90 | 0.032 | 0.53 | 0.20, 1.42 | 0.21 |

| Clinical tumor stage | |||||||||

| (Reference: cTa/cTis/cT1) | |||||||||

| cT2 | 4.92 | 1.84, 13.13 | 0.001 | 45.10 | 9.46, 215.03 | <0.001 | 29.15 | 6.32, 134.36 | <0.001 |

| cT3/cT4 | 11.16 | 3.86, 32.27 | <0.001 | 23.49 | 4.91, 112.20 | <0.001 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit test | Hosmer–Lemeshow test | 0.20 | 0.68 | 0.91 | |||||

| AUC | |||||||||

| Model with PIV | AUC: 0.78 | AUC: 0.80 | AUC: 0.81 | ||||||

| Model without PIV | AUC: 0.76 (+2%) | AUC: 0.77 (+3%) | AUC: 0.76 (+5%) | ||||||

| (p = difference model) | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.04 |

| Lymph node | Advanced Tumor grading | Locoregionally extended state | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

| NLR (Reference: low) | |||||||||

| High | 1.47 | 0.65, 3.36 | 0.35 | 1.98 | 0.97, 4.05 | 0.06 | 1.60 | 0.80, 3.18 | 0.17 |

| Age | 1.13 | 0.33, 3.82 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.29, 1.99 | 0.588 | 1.01 | 0.40, 2.51 | 0.97 |

| Smoke (Reference: no) | |||||||||

| Smoke | 0.54 | 0.21, 1.35 | 0.19 | 0.79 | 0.32, 1.94 | 0.620 | 1.22 | 0.51, 2.93 | 0.65 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | |||||||||

| Female | 0.58 | 0.20, 1.66 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.11, 0.92 | 0.035 | 0.57 | 0.21, 1.48 | 0.25 |

| Clinical tumor stage | |||||||||

| (Reference: cTa/cTis/cT1) | |||||||||

| cT2 | 4.99 | 1.88, 13.25 | 0.001 | 44.10 | 9.29, 209.21 | <0.001 | 27.01 | 5.97, 122.05 | <0.001 |

| cT3/cT4 | 13.19 | 4.72, 36.85 | <0.001 | 32.22 | 6.73, 154.29 | <0.001 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit test | Hosmer–Lemeshow test | 0.97 | 0.25 | 0.91 | |||||

| AUC | |||||||||

| Model with NLR | AUC: 0.77 | AUC: 0.78 | AUC: 0.77 | ||||||

| Model without NLR | AUC: 0.76 (+1%) | AUC: 0.77 (+1%) | AUC: 0.76 (+1%) | ||||||

| (p = difference model) | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Lymph Node | Advanced Tumor grading | Locoregionally extended state | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

| SII (Reference: low) | |||||||||

| High | 2.91 | 1.09, 7.72 | 0.03 | 2.09 | 1.00, 4.40 | 0.05 | 2.96 | 1.44, 6.08 | 0.003 |

| Age | 1.10 | 0.33, 3.72 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.30, 2.07 | 0.644 | 1.06 | 0.42, 2.70 | 0.89 |

| Smoke (Reference: no) | |||||||||

| Smoke | 0.56 | 0.22, 1.41 | 0.22 | 0.82 | 0.33, 2.02 | 0.680 | 1.30 | 0.53, 3.19 | 0.56 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | |||||||||

| Female | 0.52 | 0.18, 1.51 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.11, 0.91 | 0.034 | 0.51 | 0.19, 1.36 | 0.18 |

| Clinical tumor stage | |||||||||

| (Reference: cTa/cTis/cT1) | |||||||||

| cT2 | 5.35 | 1.97, 14.56 | 0.001 | 45.06 | 9.47, 214.31 | <0.001 | 31.41 | 6.73, 146.46 | <0.001 |

| cT3/cT4 | 10.58 | 3.70, 30.19 | <0.001 | 27.08 | 5.66, 129.51 | <0.001 | |||

| Goodness-of-fit test | Hosmer–Lemeshow test | 0.89 | 0.21 | 0.82 | |||||

| AUC | |||||||||

| Model with SII | AUC: 0.79 | AUC: 0.80 | AUC: 0.81 | ||||||

| Model without SII | AUC: 0.76 (+3%) | AUC: 0.77 (+3%) | AUC: 0.76 (+5%) | ||||||

| (p = difference model) | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| Relapse-Free Survival | Cancer-Specific Survival | Overall Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95%CI | p-value | HR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| PIV (Reference: low) | |||||||||

| High | 1.89 | 1.12, 3.19 | 0.017 | 1.07 | 0.57, 2.02 | 0.819 | 1.64 | 1.05, 2.56 | 0.029 |

| Age | 0.77 | 0.40, 1.46 | 0.427 | 1.27 | 0.53, 3.04 | 0.579 | 1.11 | 0.61, 2.02 | 0.717 |

| Smoking status (Reference: no) | |||||||||

| Smoke | 0.91 | 0.53, 1.55 | 0.744 | 1.30 | 0.62, 2.73 | 0.478 | 1.25 | 0.74, 2.10 | 0.401 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | |||||||||

| Female | 0.86 | 0.49, 1.52 | 0.624 | 1.47 | 0.78, 2.80 | 0.230 | 1.06 | 0.64, 1.75 | 0.811 |

| Clinical tumor condition | |||||||||

| (Reference: cTa/cTis/cT1) | |||||||||

| cT2 | 1.58 | 0.82, 3.05 | 0.168 | 1.03 | 0.42, 2.53 | 0.938 | 1.25 | 0.69, 2.27 | 0.450 |

| cT3/cT4 | 7.14 | 3.90, 13.06 | <0.001 | 8.77 | 4.13, 18.61 | <0.001 | 4.02 | 2.24, 7.19 | <0.001 |

| Harrel’s index | |||||||||

| Model accuracy | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.66 | ||||||

| Model accuracy without PIV | 0.68 (+4%) | 0.71 (+1%) | 0.63 (+3%) | ||||||

| (p = difference model) | 0.01 | 0.81 | 0.03 |

| Relapse-Free Survival | Cancer-Specific Survival | Overall Survival | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95%CI | p-value | HR | 95%CI | p-value | HR | 95%CI | p-value |

| PIV (Reference: low) | |||||||||

| High | 1.74 | 1.04, 2.92 | 0.034 | 1.30 | 0.69, 2.43 | 0.412 | 1.58 | 1.00, 2.49 | 0.048 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.52, 1.88 | 0.994 | 1.46 | 0.61, 3.49 | 0.387 | 1.21 | 0.67, 2.21 | 0.517 |

| Smoking status (Reference: no) | |||||||||

| Smoke | 1.26 | 0.72, 2.19 | 0.403 | 2.13 | 1.02, 4.44 | 0.043 | 1.73 | 1.02, 2.92 | 0.039 |

| Sex (Reference: male) | |||||||||

| Female | 1.42 | 0.77, 2.61 | 0.258 | 1.78 | 0.92, 3.45 | 0.084 | 1.30 | 0.77, 2.18 | 0.314 |

| Tumor grading | |||||||||

| (Reference: pT0/pTa/pTispT1) | |||||||||

| pT2 | 1.67 | 0.65, 4.28 | 0.283 | 0.98 | 0.31, 3.11 | 0.981 | 1.54 | 0.70, 3.40 | 0.276 |

| pT3/pT4 | 2.84 | 1.14, 7.09 | 0.025 | 2.88 | 1.17, 7.11 | 0.021 | 3.23 | 1.59, 6.53 | 0.001 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 1.03 | 0.41, 2.54 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.38, 2.44 | 0.957 | 0.90 | 0.44, 1.81 | 0.774 |

| Lymph node invasion | 3.85 | 2.12, 6.99 | <0.001 | 4.26 | 1.89, 9.61 | <0.001 | 3.12 | 1.74, 5.60 | <0.001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.31 | 0.73, 2.34 | 0.349 | 0.44 | 0.19, 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 0.34, 1.08 | 0.092 |

| C-index | |||||||||

| Model with PIV | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Model without PIV | 0.77 (+1%) | 0.76 | 0.72 (1%) | ||||||

| (p = difference model) | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).