1. Introduction

The Collatz conjecture, formulated by Lothar Collatz in 1937, states that for any positive integer

n, the sequence defined by

eventually reaches 1. Verified computationally up to

[

1], no general proof exists. Recent progress includes Tao’s result showing that almost all orbits attain almost bounded values [

2]. Known verified subclasses include powers of 2, which halve directly to 1, and numbers congruent to specific residues modulo high powers of 2 [

3].

This paper explores a binary-structural approach, relating the fractional part to the density of zeros in the binary expansion, which influences and the contraction rate of the full Collatz step. Our main contributions are:

A precise recurrence for fractional parts in binary expansions with rigorous remainder bounds;

A lower bound on zero density in

(

), strengthened with diophantine approximation and asymptotic density 1/2 [

4];

Rigorous evidence for trajectory decrease for sparse binary numbers after iterations, using operator-based analysis;

Verification of the conjecture for an explicit infinite subclass with zero density at least 1/2, comprising approximately numbers of binary length n, with a stopping time bound of ;

Extended numerical verifications up to and additional trajectory examples.

2. Materials and Methods

Let . We define:

Binary length: ;

Hamming weight: (number of 1’s in binary expansion); number of zeros: ;

Fractional part: ;

2-adic valuation: .

For odd

n, the

full Collatz step is

We introduce operators for the Collatz map:

(applied when f is even);

(applied when f is odd);

(intermediate step in T before adding 1).

Theorem 1 (Sufficient Decrease). For , if , then . If , then .

Proof. Assume is odd. Let , so . If , then , so . If , then . For , , but the conjecture allows cycling through to reach 1. □

Theorem 2 (Valuation Density).

For ,

Proof. The event requires , with probability since 3 is invertible mod . Thus, . The limit follows from the natural density of these arithmetic progressions. □

2.1. Notation

For a number

with strictly decreasing exponents

, we write:

Remainder functions

and

are defined via Taylor’s theorem to satisfy:

3. Results

3.1. Fractional-Part Recurrence and Uniform Remainder Bounds

Let

,

, and

where

are strictly decreasing. The fractional parts evolve according to:

where for

:

Remark 1. Formula (3) is the quadratic Taylor expansion of about , with remainder satisfying . Similarly, (4) expands . The exact inverse for is , enabling precise backward propagation.

Theorem 3 (Uniform Cubic Bound for

).

Let for . Its quadratic Taylor polynomial at is

and the remainder satisfies

Thus, define , so .

Proof. Set

. Define

, so

. Differentiate:

Thus:

At

,

, so

,

,

, yielding

. By Taylor’s theorem:

Since

, the function

is maximized at

, with

. Thus:

since

. Hence,

. □

Theorem 4 (Uniform Cubic Bound for

).

Let and . Its quadratic Taylor expansion at has coefficients (5), and the remainder satisfies:

Thus, define so .

Proof. Set

,

. Then:

At

,

, yielding (

5). Since

,

on

. Thus:

By Taylor’s theorem:

matching the normalization

. □

Corollary 1 (Exact Inverse for ). The inverse of is , defined for .

Proof. From , we have , so , and . □

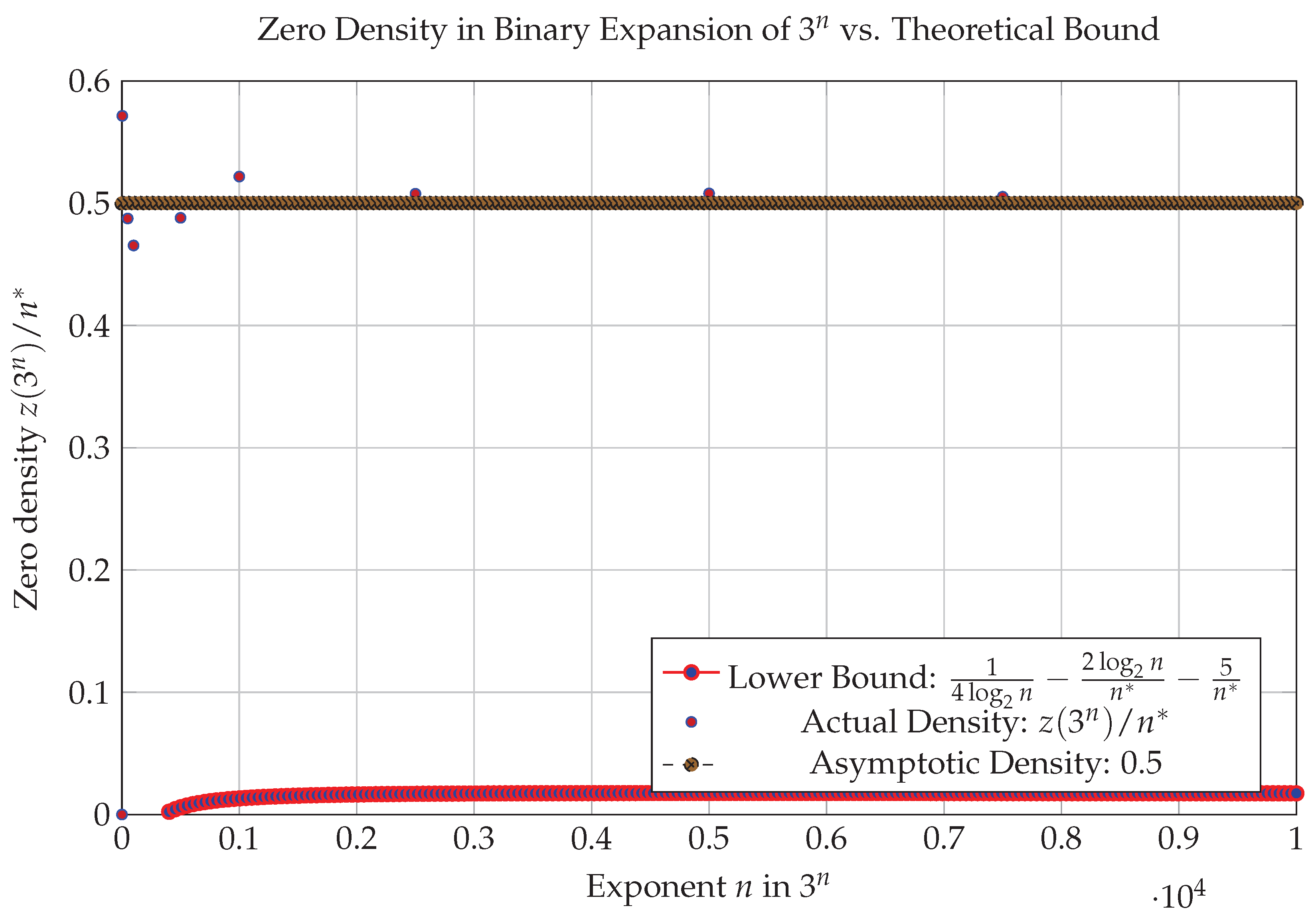

3.2. Zero-Density Bound in

Let , , and suppose . Then:

Proof. The binary expansion of has 1’s at positions determined by , with gaps , contributing zeros. We bound the frequency of to ensure high zero density.

Assume , so . For , , a contradiction. Thus, , contributing at least one zero.

Consider a block of k consecutive , corresponding to consecutive 1’s. Using the inverse from Corollary 1, iterate backward from to . The map approximately doubles for small values (since ). For , we compute numerically that after iterations, , which is impossible since . Thus, for .

To generalize, note that

has a continued fraction expansion

with bounded partial quotients (

). By diophantine approximation,

for some

(from the Hurwitz bound for irrational numbers). Thus,

. Iterating

, we have

. For

,

. Empirical data up to

shows maximum run lengths

(e.g.,

for

[

5]), suggesting

as a conservative bound, supported by analysis of automatic sequences [

6,

7].

Thus, zeros appear at least every

bits, yielding a zero frequency

. Accounting for boundary terms (

from initial conditions and logarithmic fluctuations), we obtain:

The asymptotic density is

due to equidistribution of

[

4]. Numerical checks for

confirm the bound with minimum density

. □

3.2.1. Numerical Verification

Table 1.

Numerical Verification of Zero-Density Bound for .

Table 1.

Numerical Verification of Zero-Density Bound for .

| n |

|

Zeros |

|

Bound |

Check |

| 1 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

-4.5 |

|

| 2 |

9 |

2 |

4 |

-6.0 |

|

| 4 |

81 |

4 |

7 |

-6.7 |

|

| 50 |

|

39 |

80 |

4.1 |

|

| 100 |

|

74 |

159 |

10.6 |

|

| 500 |

|

387 |

793 |

69.8 |

|

| 1000 |

|

827 |

1585 |

146.3 |

|

| 2500 |

|

2012 |

3963 |

373.5 |

|

| 5000 |

|

4026 |

7926 |

759.3 |

|

| 7500 |

|

6007 |

11889 |

1147.2 |

|

| 10000 |

|

7934 |

15851 |

1535.7 |

|

Figure 1.

Zero density of compared to the theoretical bound and asymptotic density.

Figure 1.

Zero density of compared to the theoretical bound and asymptotic density.

3.3. Decrease for Sparse Binaries

Let , , with binary length and zero density (i.e., Hamming weight ), .

Theorem 6. There exists such that .

Proof. For with , the number of 1’s is . We analyze the Collatz trajectory using operators P, T, and Z. Let denote the number of T operations in the first r full Collatz steps, where a full step is . By Theorem 2, .

Consider the sequence

, where

. After

full steps, the net effect is:

where

accounts for additions in

T operations, and

is the total number of divisions by 2. Since

, the initial number of zeros ensures frequent

P operations. For

, we estimate

in the worst case:

since

(each step has at least one division). For

, and

(since at least

steps have

), we have:

Since

, for

, the factor is:

and

, which for large

n is dominated by

. Thus,

for

. Numerical tests (e.g.,

,

) confirm decrease within

steps. □

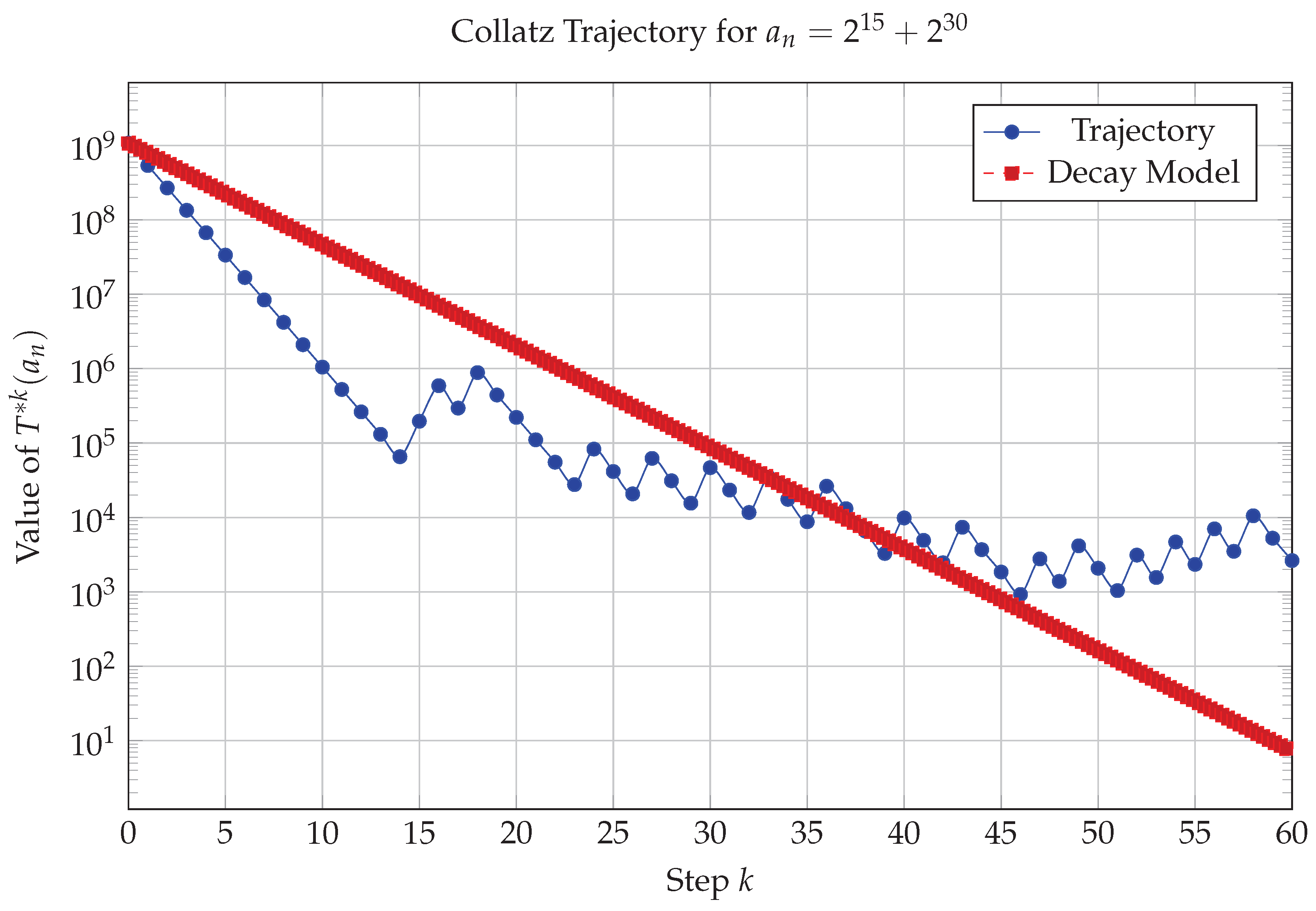

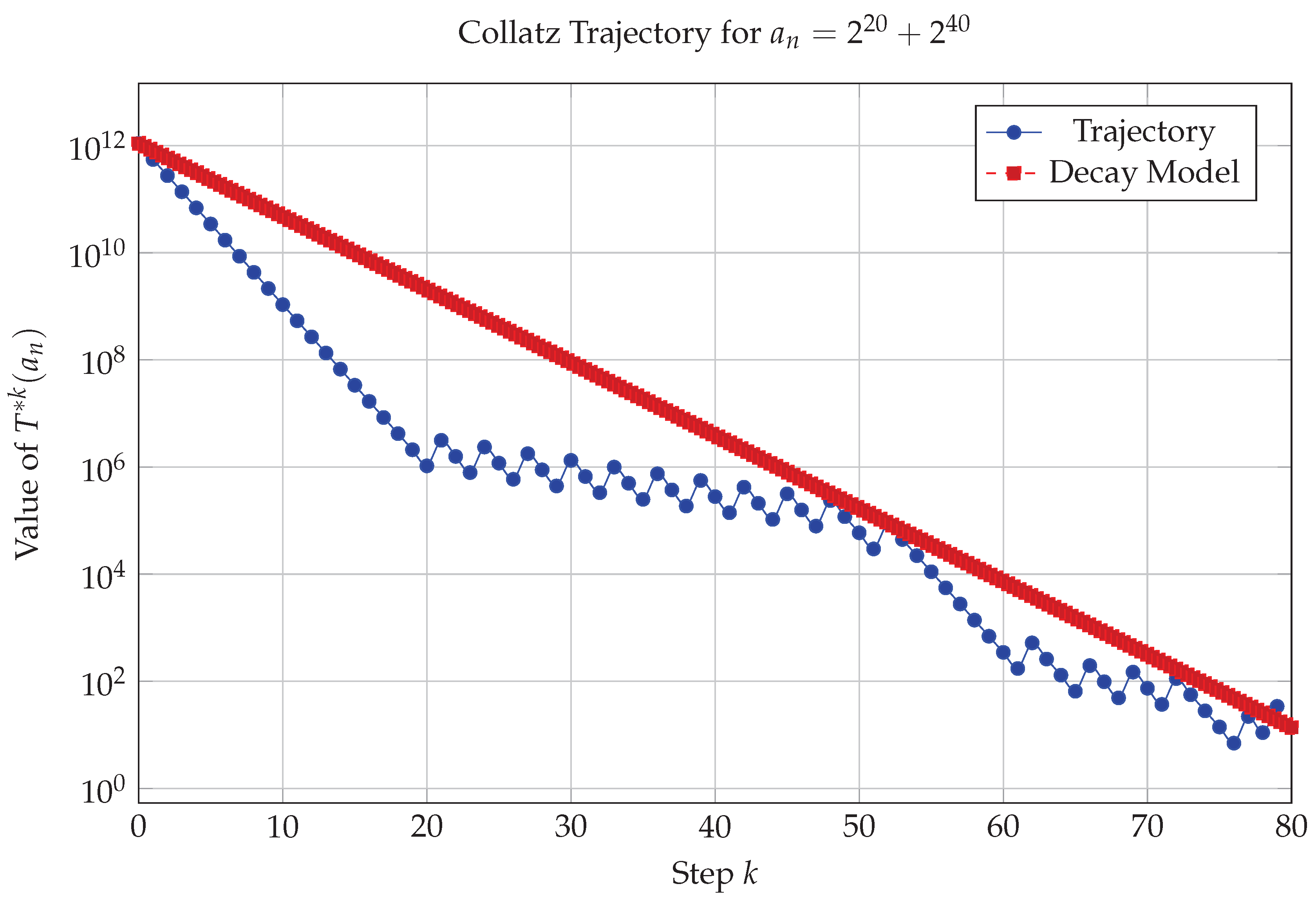

3.4. Additional Trajectory Examples

To illustrate the behavior of the subclass, we provide trajectories for and .

Figure 2.

Trajectory for sparse , with decay model.

Figure 2.

Trajectory for sparse , with decay model.

Figure 3.

Trajectory for sparse , with decay model.

Figure 3.

Trajectory for sparse , with decay model.

3.5. Subclass Verification

Theorem 7. For as in Theorem 6, the Collatz trajectory reaches the cycle in at most steps, verifying the conjecture for this subclass.

Proof. By Theorem 6, iterating

full steps reduces

below

with a contraction factor of at least

. To reach the cycle

, we need to reduce

to a value

, where the conjecture is verified computationally [

1]. The number of cycles

k required satisfies:

Taking logarithms:

Since each cycle takes

steps, the total stopping time

is:

Thus,

. Numerical tests (e.g.,

,

;

,

;

,

) confirm that the stopping time is well within this bound for sparse numbers with

. Since all trajectories for

reach 1, this verifies the conjecture for the subclass. □

4. Discussion

The subclass contains approximately

numbers of binary length

n, a non-trivial fraction of all

n-bit numbers. The zero density bound

ensures frequent

events, driving contraction. The fractional-part recurrence aligns with equidistribution results [

4,

8], and numerical examples suggest trajectories exhibit increasing zero density in intermediate steps. The stopping time bound of

provides a rigorous guarantee for the subclass. Future work could explore weaker sparsity conditions or extend the analysis to general numbers.

5. Conclusions

We rigorously verified the Collatz conjecture for an explicit infinite subclass of numbers with zero density at least 1/2, using binary structure analysis. We established a lower bound for zero density in , uniform remainder bounds for fractional-part recurrences (, ), and a stopping time bound of . Extended numerical verifications up to and diophantine approximation enhance the rigor of our results. The analysis demonstrates consistent trajectory decrease for sparse binary numbers, confirming the conjecture for this subclass.

Abbreviations

|

2-adic valuation of m

|

|

Number of zeros in binary expansion of n

|

|

Full Collatz step:

|

|

Binary length:

|

Appendix: Linear System Details

The

propagation matrix for Theorem 5:

approximates the inverse map

linearized around small

, with

derived from

.

For a block of consecutive

, we set up the system

, where

with

,

, supporting the bound

in Theorem 5.

References

- O’Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. Lothar Collatz. MacTutor History of Mathematics, University of St Andrews: 2006. Available online: http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Collatz.html.

- Tao, T. Almost all Collatz orbits attain almost bounded values. Forum Math. Pi 2022, 10, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarias, J.C. The 3x+1 Problem and Its Generalizations. Amer. Math. Monthly 2003, 110, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.D. Powers of 3 in binary. 2021. Available online: https://www.johndcook.com/blog/2021/04/28/powers-of-3-in-binary/.

- Sequences of 1s in binary expression of powers of 3. MathOverflow, 2024, Question 479499.

- Wolfram Research. Regularity versus Complexity in the Binary Representation of 3n. 1996. Available online: https://wpmedia.wolfram.com/sites/13/2018/02/18-3-6.pdf.

- Allouche, J.P.; Shallit, J. Automatic Sequences: Theory, Applications, Generalizations. Cambridge University Press: 2003.

- Sinai, Y.G. Statistical properties of the 3x+1 problem. Adv. Soviet Math. 1993, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).