Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

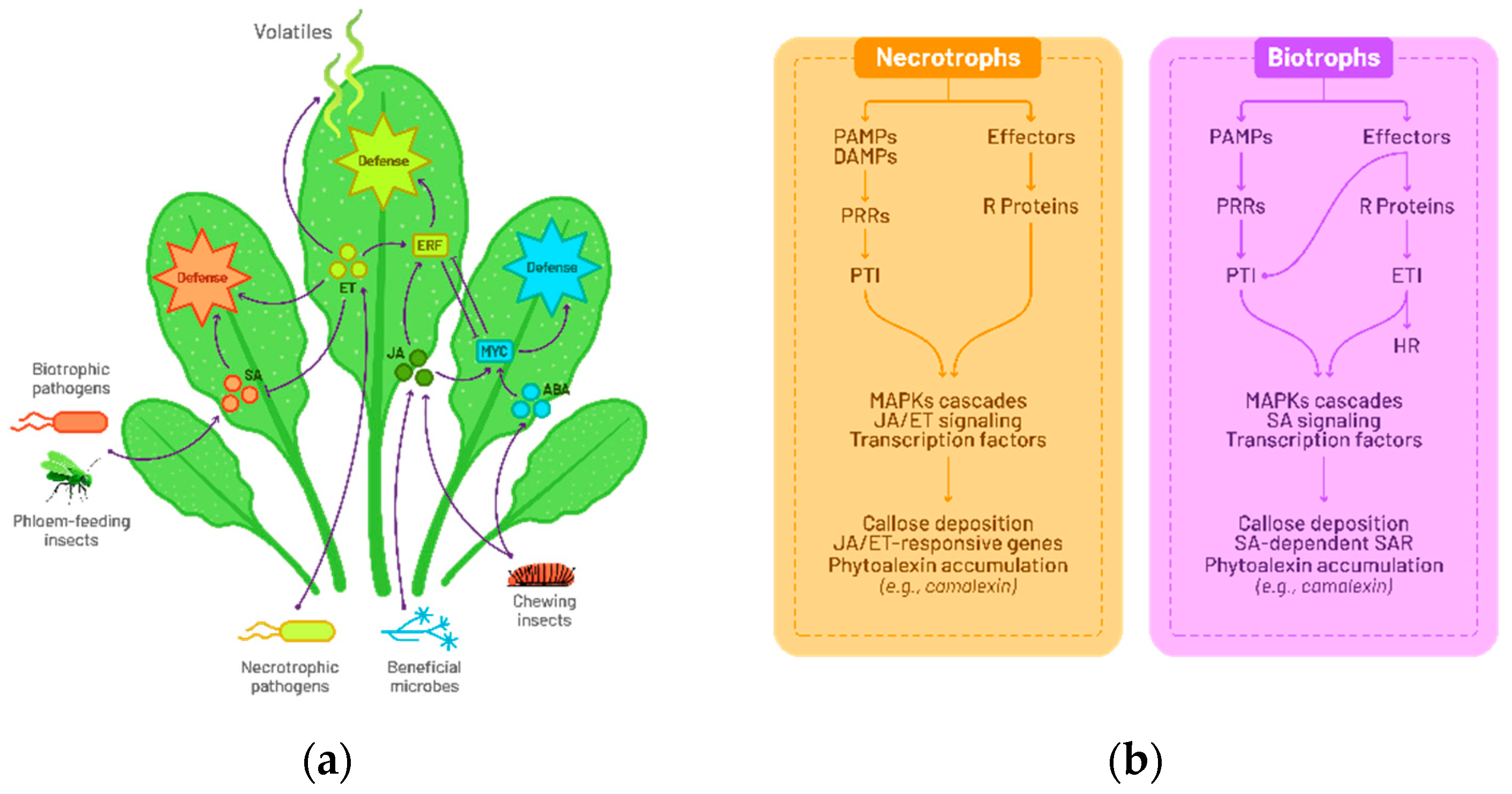

2. Plant immune response

2.1. A general model for plant pathogen interaction

2.2. Susceptible response and plant tolerance

3. Black spot disease in Brassicaceae

4. Seed defense mechanisms and interaction with the necrotrophic seedborne fungi Alternaria brassicicola

4.1. A silent interaction with the seed

4.2. Interaction with the necrotrophic seedborne fungi Alternaria brassicicola

5. Future perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortega-Cuadros, M.; De Souza, T.L.; Berruyer, R.; Aligon, S.; Pelletier, S.; Renou, J.-P.; Arias, T.; Campion, C.; Guillemette, T.; Verdier, J.; Grappin, P. Seed Transmission of Pathogens: Non-Canonical Immune Response in Arabidopsis Germinating Seeds Compared to Early Seedlings against the Necrotrophic Fungus Alternaria Brassicicola. Plants 2022, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewley, J.D.; Bradford, K.J.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy, 3rd Edition; Springer New York, 2013; Vol. 978146144 6934.

- Gupta, S.; Van Staden, J.; Doležal, K. An Understanding of the Role of Seed Physiology for Better Crop Productivity and Food Security. Plant Growth Regul 2022, 97, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonogaki, H. Seed Biology Updates - Highlights and New Discoveries in Seed Dormancy and Germination Research. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonogaki, H. Seed Germination and Dormancy: The Classic Story, New Puzzles, and Evolution. J Integr Plant Biol 2019, 61, 541–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonogaki, H. Seed Dormancy and Germination—Emerging Mechanisms and New Hypotheses. Front Plant Sci 2014, 5, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, E.B. The Seed Microbiome: Origins, Interactions, and Impacts. Plant Soil 2018, 422, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, A.F.; Bashir, I.; Reshi, Z.A.; Kardol, P.; Rashid, I. Insights into the Seed Microbiome and Its Ecological Significance in Plant Life. Microbiol Res 2023, 269, 127318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitink, J.; Leprince, O. Advances in Seed Science and Technology for More Sustainable Crop Production, 1st ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2022.

- Dell’Olmo, E.; Tiberini, A.; Sigillo, L. Leguminous Seedborne Pathogens: Seed Health and Sustainable Crop Management. Plants 2023, 12, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cram, M.M.; Fraedrich, S.W. Seed Diseases and Seedborne Pathogens of North America. Tree Planters’ Notes 2010, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Gupta, A. Seed-Borne Diseases of Agricultural Crops: Detection, Diagnosis & Management; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dodds, P.N.; Rathjen, J.P. Plant Immunity: Towards an Integrated View of Plant–Pathogen Interactions. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The Plant Immune System. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.L.; Trick, M.; Higgins, J.; Fraser, F.; Clissold, L.; Wells, R.; Hattori, C.; Werner, P.; Bancroft, I.; Gullino, M.L.; Munkvold, G. Global Perspectives on the Health of Seeds and Plant Propagation Material; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2014; Vol. Plant Path.

- Glazebrook, J. Contrasting Mechanisms of Defense Against Biotrophic and Necrotrophic Pathogens. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923 2005, 43, 205–227. [CrossRef]

- Divon, H.H.; Fluhr, R. Nutrition Acquisition Strategies during Fungal Infection of Plants. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2007, 266, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghozlan, M.H.; EL-Argawy, E.; Tokgöz, S.; Lakshman, D.K.; Mitra, A.; Ghozlan, M.H.; EL-Argawy, E.; Tokgöz, S.; Lakshman, D.K.; Mitra, A. Plant Defense against Necrotrophic Pathogens. Am J Plant Sci 2020, 11, 2122–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, M.D. Primary Metabolism and Plant Defense—Fuel for the Fire. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI-22-5-0487 2009, 22, 487–497. [CrossRef]

- Łaźniewska, J.; Macioszek, V.K.; Kononowicz, A.K. Plant-Fungus Interface: The Role of Surface Structures in Plant Resistance and Susceptibility to Pathogenic Fungi. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 2012, 78, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

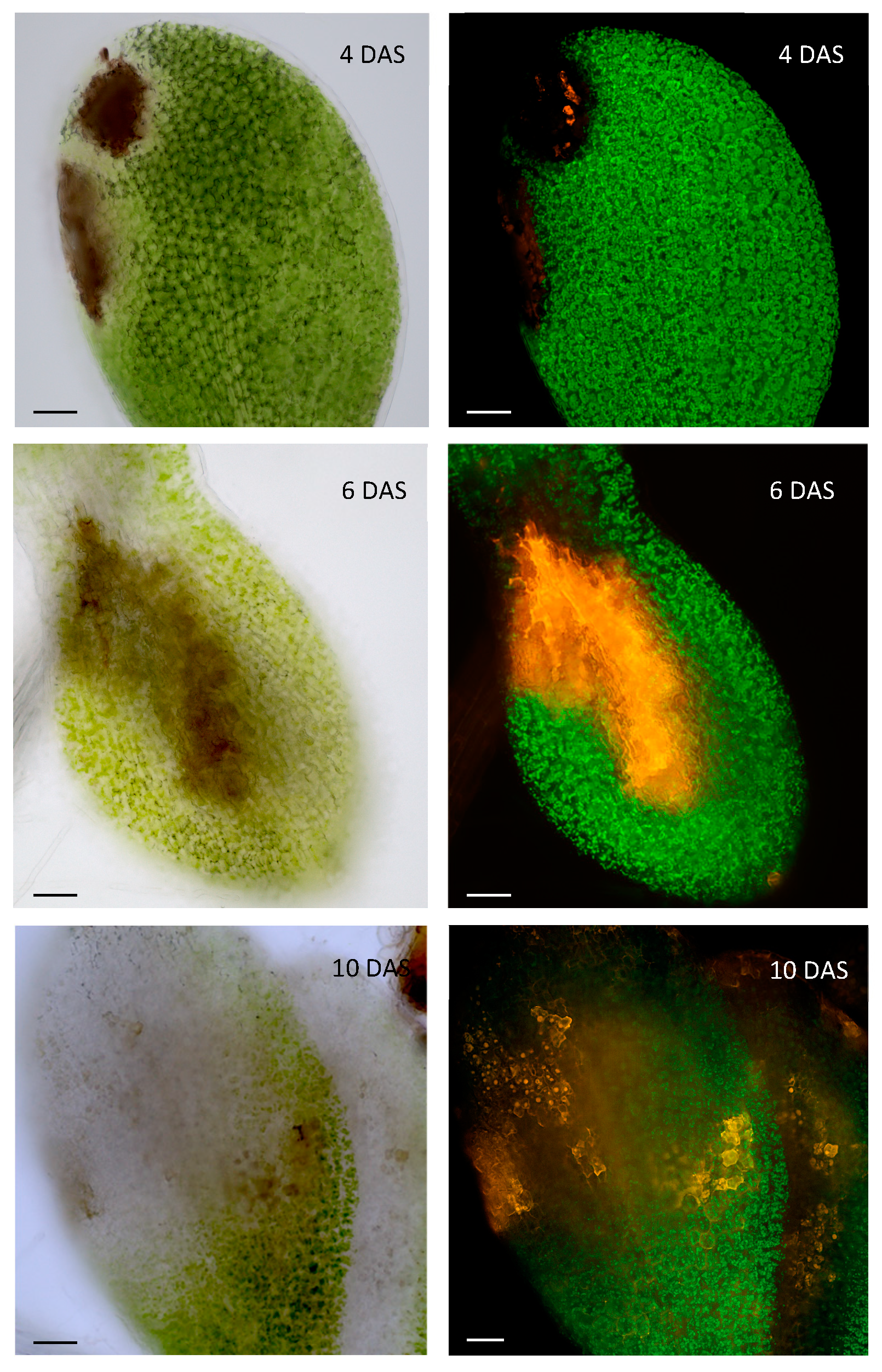

- Pochon, S.; Terrasson, E.; Guillemette, T.; Iacomi-Vasilescu, B.; Georgeault, S.; Juchaux, M.; Berruyer, R.; Debeaujon, I.; Simoneau, P.; Campion, C. The Arabidopsis Thaliana-Alternaria Brassicicola Pathosystem: A Model Interaction for Investigating Seed Transmission of Necrotrophic Fungi. Plant Methods 2012, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łaźniewska, J.; Macioszek, V.K.; Lawrence, C.B.; Kononowicz, A.K. Fight to the Death: Arabidopsis Thaliana Defense Response to Fungal Necrotrophic Pathogens. Acta Physiol Plant 2010, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wees, S.C.M.; Chang, H.; Zhu, T.; Glazebrook, J. Characterization of the Early Response of Arabidopsis to Alternaria Brassicicola Infection Using Expression Profiling. Plant Physiol 2003, 132, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalling, J.W.; Davis, A.S.; Arnold, A.E.; Sarmiento, C.; Zalamea, P.-C. Extending Plant Defense Theory to Seeds. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 2020, 51, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, E.P.; Okubara, P.A.; Anderson, J.V.; Morris, C.F. Polyphenol Oxidase as a Biochemical Seed Defense Mechanism. Front Plant Sci 2014, 5, 117840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panstruga, R.; Moscou, M.J. What Is the Molecular Basis of Nonhost Resistance? Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioszek, V.K.; Jęcz, T.; Ciereszko, I.; Kononowicz, A.K. Jasmonic Acid as a Mediator in Plant Response to Necrotrophic Fungi. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Hu, S.; Jian, W.; Xie, C.; Yang, X. Plant Antimicrobial Peptides: Structures, Functions, and Applications. Botanical Studies. 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stotz, H.U.; Sawada, Y.; Shimada, Y.; Hirai, M.Y.; Sasaki, E.; Krischke, M.; Brown, P.D.; Saito, K.; Kamiya, Y. Role of Camalexin, Indole Glucosinolates, and Side Chain Modification of Glucosinolate-Derived Isothiocyanates in Defense of Arabidopsis against Sclerotinia Sclerotiorum. Plant Journal 2011, 67, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Schlaich, N. Arabidopsis Thaliana- The Model Plant to Study Host-Pathogen Interactions. Curr Drug Targets 2011, 12, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balint-Kurti, P. The Plant Hypersensitive Response: Concepts, Control and Consequences. Mol Plant Pathol 2019, 20, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ádám, A.L.; Nagy, Z.; Kátay, G.; Mergenthaler, E.; Viczián, O. Signals of Systemic Immunity in Plants: Progress and Open Questions. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrath, U. Systemic Acquired Resistance. Plant Signal Behav 2006, 1, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellam, A.; Iacomi-Vasilescu, B.; Hudhomme, P.; Simoneau, P. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Brassinin, Camalexin and Two Isothiocyanates against the Crucifer Pathogens Alternaria Brassicicola and Alternaria Brassicae. Plant Pathol 2007, 56, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, U.S.; Lee, S.; Mysore, K.S. Host versus Nonhost Resistance: Distinct Wars with Similar Arsenals. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nürnberger, T.; Lipka, V. Non-Host Resistance in Plants: New Insights into an Old Phenomenon. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Lefert, P.; Panstruga, R. A Molecular Evolutionary Concept Connecting Nonhost Resistance, Pathogen Host Range, and Pathogen Speciation. Trends in Plant Science. 2011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patkar, R.N.; Naqvi, N.I. Fungal Manipulation of Hormone-Regulated Plant Defense. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, D.; Smith, D.L.; Kabbage, M.; Roth, M.G. Effectors of Plant Necrotrophic Fungi. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorshkov, V.; Tsers, I. Plant Susceptible Responses: The Underestimated Side of Plant–Pathogen Interactions. Biological Reviews 2022, 97, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frías, M.; González, C.; Brito, N. BcSpl1, a Cerato-Platanin Family Protein, Contributes to Botrytis Cinerea Virulence and Elicits the Hypersensitive Response in the Host. New Phytologist 2011, 192, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, D.; Zeng, H.; Guo, L.; Yang, X. BcGs1, a Glycoprotein from Botrytis Cinerea, Elicits Defence Response and Improves Disease Resistance in Host Plants. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 457, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Oirdi, M.; El-Rahman, T.A.; Rigano, L.; El-Hadrami, A.; Rodriguez, M.C.; Daayf, F.; Vojnov, A.; Bouarab, K. Botrytis Cinerea Manipulates the Antagonistic Effects between Immune Pathways to Promote Disease Development in Tomato. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Lamothe, R.; El Oirdi, M.; Brisson, N.; Bouarab, K. The Conjugated Auxin Indole-3-Acetic Acid–Aspartic Acid Promotes Plant Disease Development. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiberg, A.; Wang, M.; Lin, F.M.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kaloshian, I.; Huang, H. Da; Jin, H. Fungal Small RNAs Suppress Plant Immunity by Hijacking Host RNA Interference Pathways. Science (1979) 2013, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, D.A.; Hendriks, K.P.; Koch, M.A.; Lens, F.; Lysak, M.A.; Bailey, C.D.; Mummenhoff, K.; Al-Shehbaz, I.A. An Updated Classification of the Brassicaceae (Cruciferae). PhytoKeys 2023, 220, 127. [CrossRef]

- Rakow, G. Species Origin and Economic Importance of Brassica. 2004, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. How the Necrotrophic Fungus Alternaria Brassicicola Kills Plant Cells Remains an Enigma. Eukaryot Cell 2015, 14, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmendra, K.; Neelam, M.; Yashwant, K.B.; Ajay, K.; Kamlesh, K.; Kalpana, S.; Gireesh, C.; Chanda, K.; Sushil, K.S.; Raj, K.M.; Adesh, K. Alternaria Blight of Oilseed Brassicas: A Comprehensive Review. Afr J Microbiol Res 2014, 8, 2816–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Tyagi, A.; Rajarammohan, S.; Mir, Z.A.; Bae, H. Revisiting Alternaria-Host Interactions: New Insights on Its Pathogenesis, Defense Mechanisms and Control Strategies. Sci Hortic 2023, 322, 112424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamgain, A.; Roychowdhury, R.; Tah, J. Alternaria Pathogenicity and Its Strategic Controls. Research & Reviews: Journal of Biology 2013, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, M.; Nowakowska, M.; Niezgoda, A.; Kozik, E. Alternaria Black Spot of Crucifers: Symptoms, Importance of Disease, and Perspectives of Resistance Breeding. Journal of Fruit and Ornamental Plant Research 2012, 76, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.; Gupta, S.K.; Swapnil, P.; Zehra, A.; Dubey, M.K.; Upadhyay, R.S. Alternaria Toxins: Potential Virulence Factors and Genes Related to Pathogenesis. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pedras, M.S.C.; Chumala, P.B.; Jin, W.; Islam, M.S.; Hauck, D.W. The Phytopathogenic Fungus Alternaria Brassicicola: Phytotoxin Production and Phytoalexin Elicitation. Phytochemistry 2009, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, C.B.; Mitchell, T.K.; Craven, K.D.; Cho, Y.; Cramer, R.A.; Kim, K.H. At Death’s Door: Alternaria Pathogenicity Mechanisms. Plant Pathol J (Faisalabad) 2008, 24, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrasse, A.; Darsonval, A.; Boureau, T.; Brisset, M.N.; Durand, K.; Jacques, M.A. Transmission of Plant-Pathogenic Bacteria by Nonhost Seeds without Induction of an Associated Defense Reaction at Emergence. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010, 76, 6787–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsonval, A.; Darrasse, A.; Meyer, D.; Demarty, M.; Durand, K.; Bureau, C.; Manceau, C.; Jacques, M.A. The Type III Secretion System of Xanthomonas Fuscans Subsp. Fuscans Is Involved in the Phyllosphere Colonization Process and in Transmission to Seeds of Susceptible Beans. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeaujon, I.; Léon-Kloosterziel, K.M.; Koornneef, M. Influence of the Testa on Seed Dormancy, Germination, and Longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2000, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smýkal, P.; Vernoud, V.; Blair, M.W.; Soukup, A.; Thompson, R.D. The Role of the Testa during Development and in Establishment of Dormancy of the Legume Seed. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Tatematsu, K.; Hanada, K.; Duermeyer, L.; Okamoto, M.; Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Saito, K.; Toyoda, T.; Kawakami, N.; Kamiya, Y.; Seki, M.; Nambara, E. Tissue-Specific Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Cell Wall Metabolism, Flavonol Biosynthesis and Defense Responses Are Activated in the Endosperm of Germinating Arabidopsis Thaliana Seeds. Plant Cell Physiol 2012, 53, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Cuadros, M.; Chir, L.; Aligon, S.; Arias, T.; Verdier, J.; Grappin, P. Dual-Transcriptomic Datasets Evaluating the Effect of the Necrotrophic Fungus Alternaria Brassicicola on Arabidopsis Germinating Seeds. Data Brief 2022, 44, 108530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Lee, Y.H. Hypoxia: A Double-Edged Sword During Fungal Pathogenesis? Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Miao, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Xia, C.; Zeng, W.; Sun, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Wang, Q. WRKY33-Mediated Indolic Glucosinolate Metabolic Pathway Confers Resistance against Alternaria Brassicicola in Arabidopsis and Brassica Crops. J Integr Plant Biol 2022, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, M.W.; Hancock, A.M.; Huang, Y.S.; Toomajian, C.; Atwell, S.; Auton, A.; Muliyati, N.W.; Platt, A.; Sperone, F.G.; Vilhjálmsson, B.J.; Nordborg, M.; Borevitz, J.O.; Bergelson, J. Genome-Wide Patterns of Genetic Variation in Worldwide Arabidopsis Thaliana Accessions from the RegMap Panel. Nat Genet 2012, 44, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koornneef, M.; Alonso-Blanco, C.; Vreugdenhil, D. NATURALLY OCCURRING GENETIC VARIATION IN ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2004, 55, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerville, C.; Koornneef, M. A Fortunate Choice: The History of Arabidopsis as a Model Plant. Nat Rev Genet 2002, 3, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, L.A.; Shushkov, P.; Nevado, B.; Gan, X.; Al-Shehbaz, I.A.; Filatov, D.; Bailey, C.D.; Tsiantis, M. Resolving the Backbone of the Brassicaceae Phylogeny for Investigating Trait Diversity. New Phytologist 2019, 222, 1638–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Host | Manipulate mechanism | Elicitors or effectors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato, Tobacco, and Arabidopsis | Programmed cell death (PCD) | Cerato-platanin family proteins (CPPs) – BcSpl Necrosis-inducing proteins (NIPs) - BcGs1. |

Frías et al. [41] Zhang et al. [42] |

| Tomato | SA pathway | Exopolysaccharide (EPS) - β-(1,3)(1,6)-d-glucan | El Oirdi M et al. [43] |

| Arabidopsis | Auxin pathway | Auxin Indole-3-Acetic Acid–Aspartic Acid -IAA-Aspartate | González-Lamothe R et al. [44] |

| Tomato and Arabidopsis | Peroxiredoxin (oxidative stress-related gene), mitogen activated protein kinases (MPK1, MPK2, MPKKK4), and a cell wall-associated kinase (WAK) | sRNAs: Bc-siR3.1 Bc-siR3.2 Bc-siR5 |

Weiberg et al. [45] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).