Submitted:

06 January 2024

Posted:

08 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

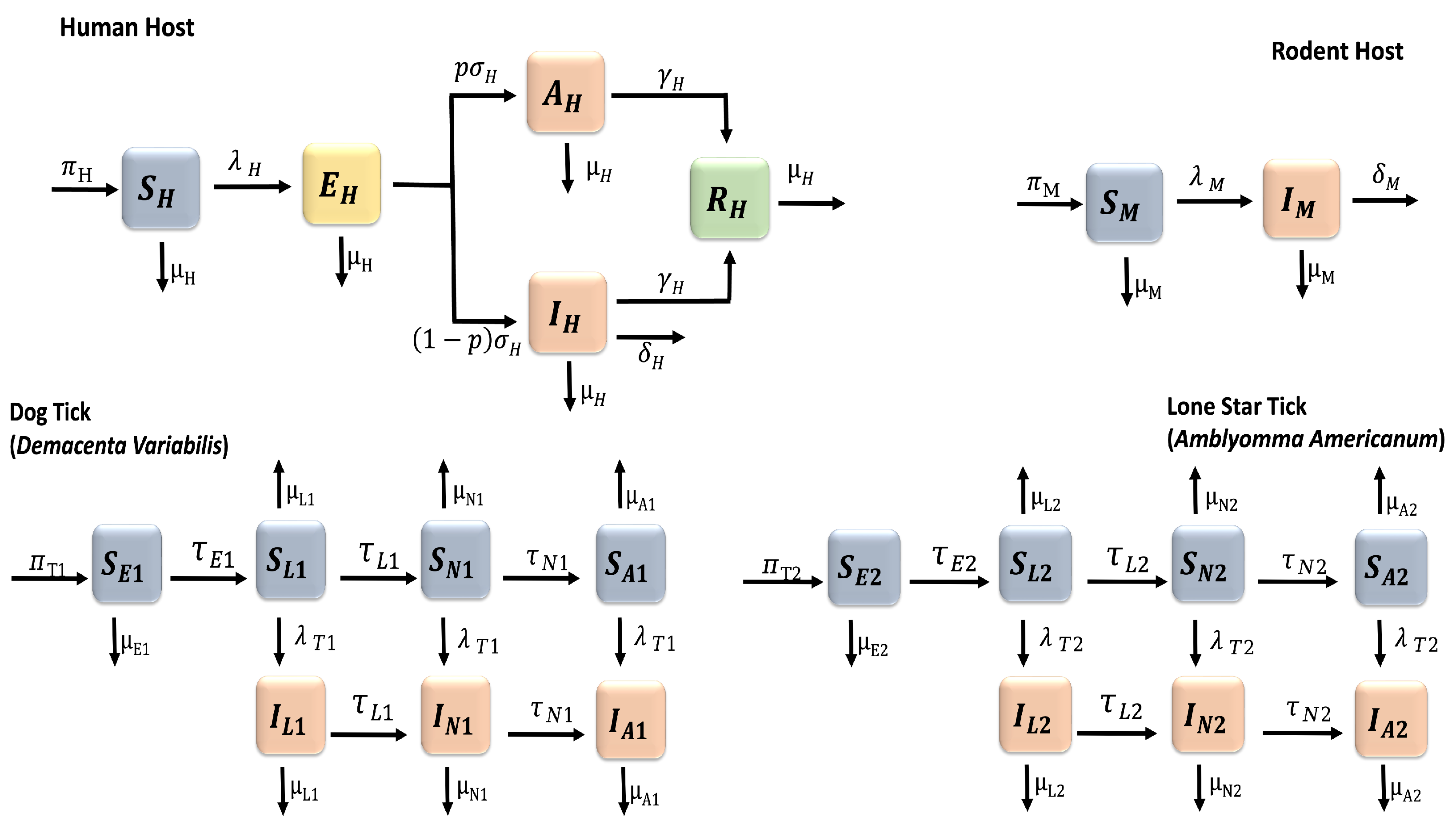

2. Model Formulation

2.1. Analysis of the Model

2.1.1. Basic Qualitative Properties

Positivity and Boundedness of Solutions

Invariant Regions

2.1.2. Stability of Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE)

3. Tick Model with Prescribed Fire

3.1. Estimating the Reduction Proportion Due to Prescribed Fire

4. Global Sensitivity Analysis

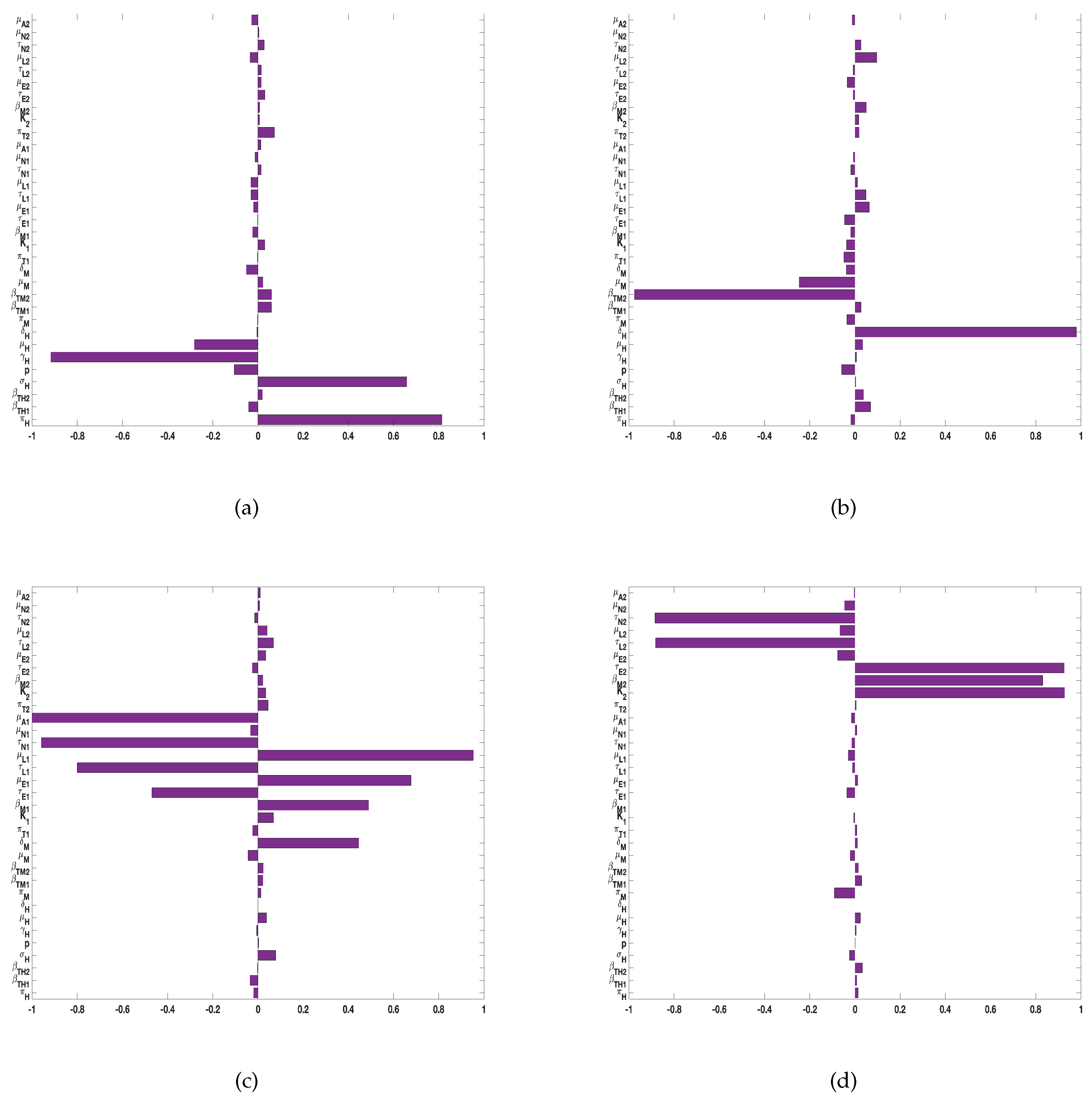

4.1. Global Sensitivity Analysis for Tularaemia Model (1)

4.2. Global Sensitivity Analysis for Tularaemia Model (2)

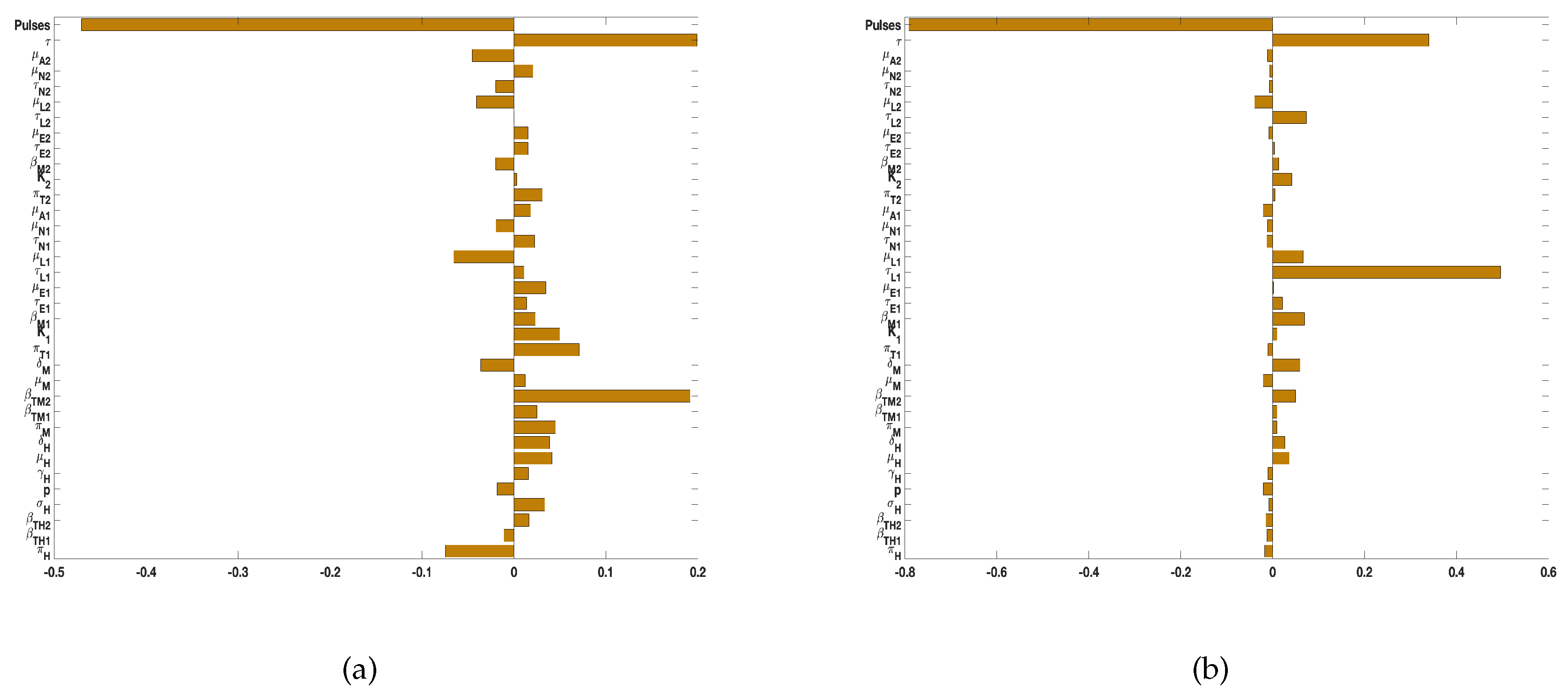

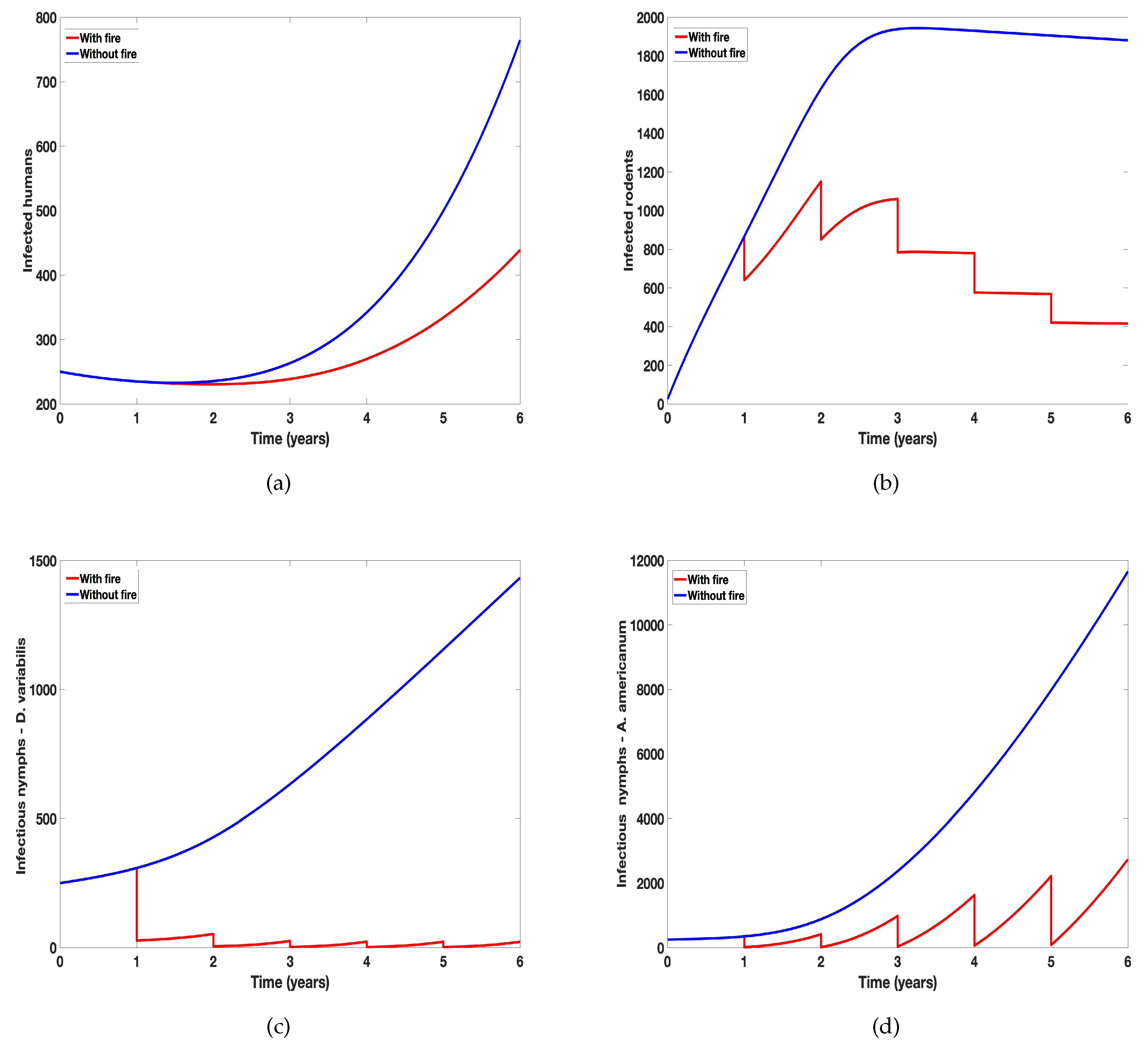

5. Numerical Simulations: Effect of Fire

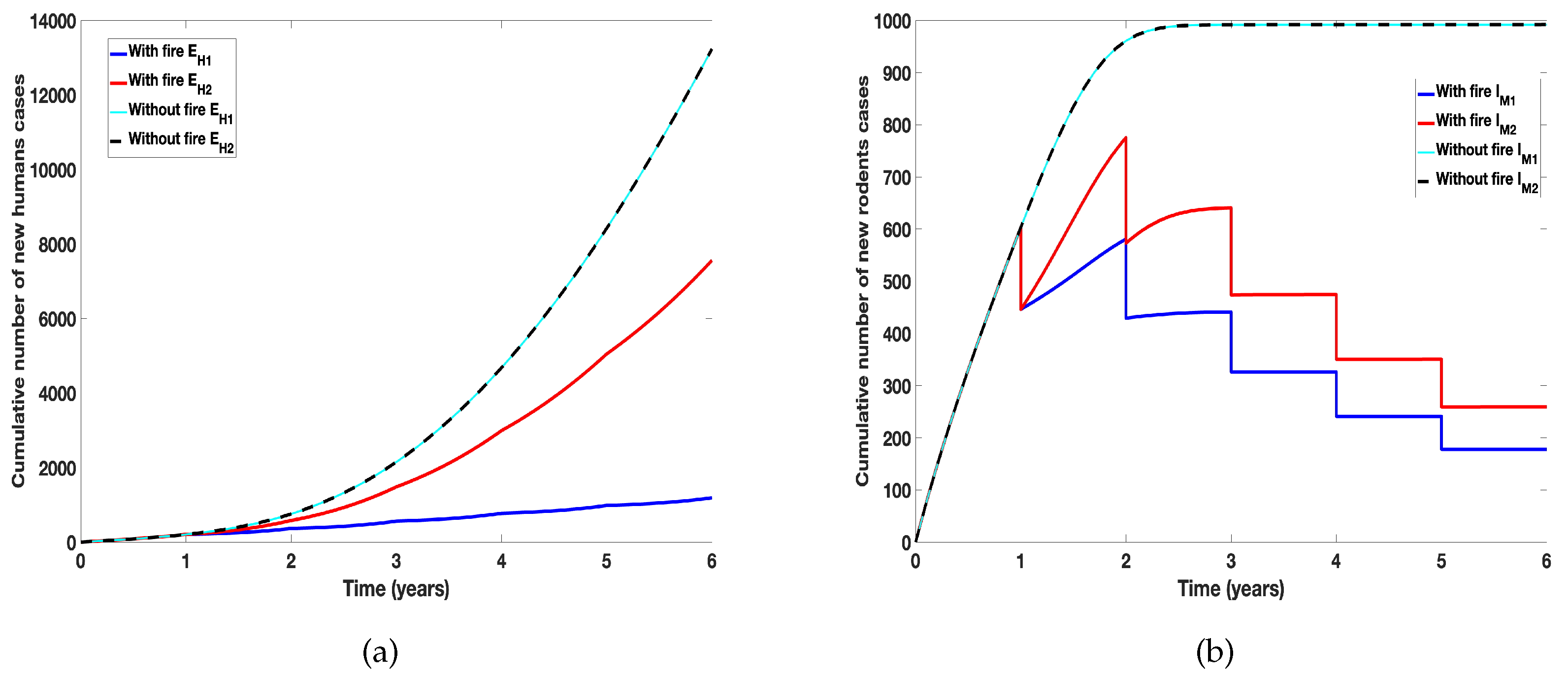

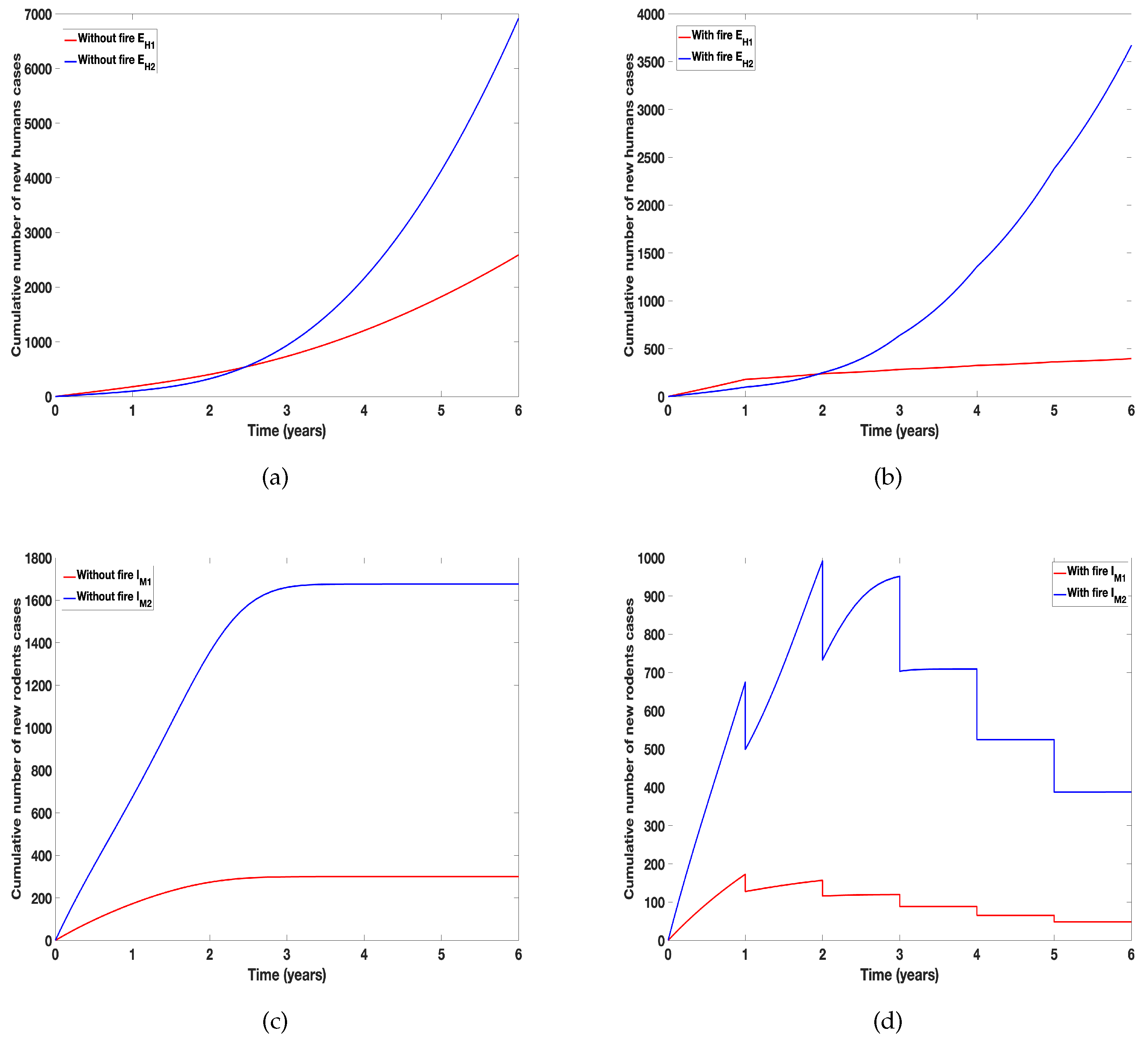

5.1. Differential Effect of Fire on Infected New Cases

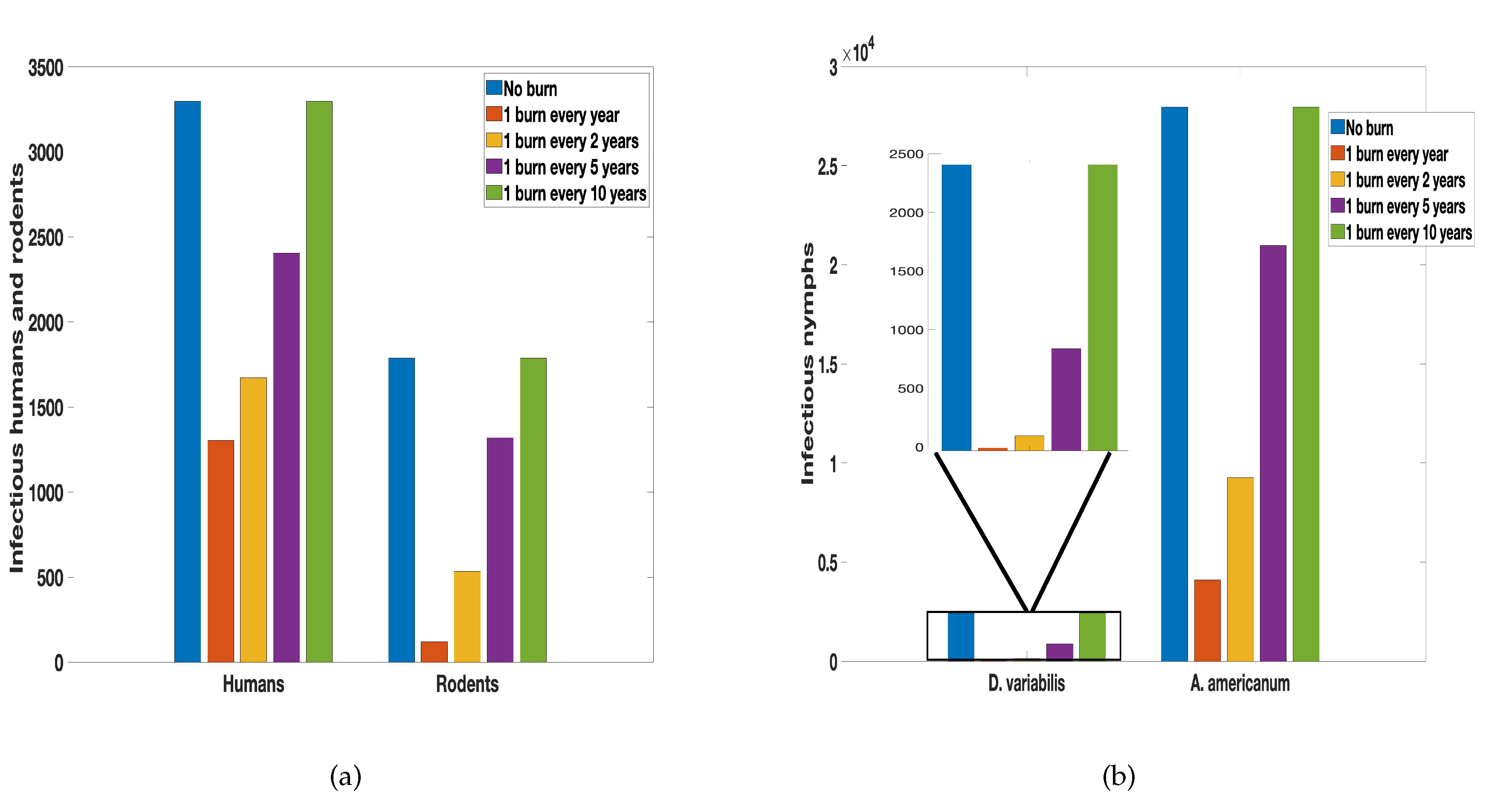

5.2. Frequency and Time between Burn

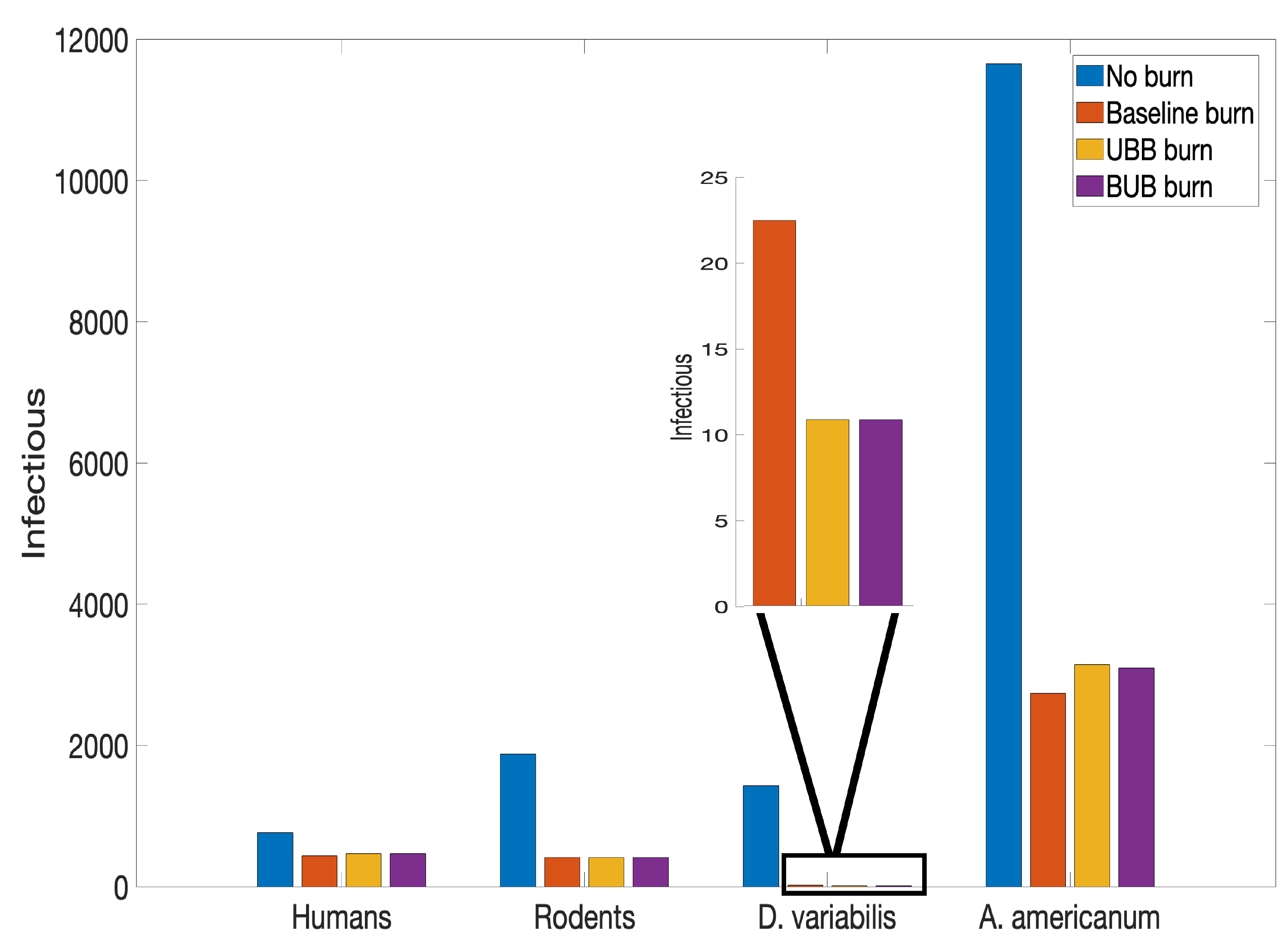

5.3. Burn Environments

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion

6.1. Conclusion

- (i)

- The results of the sensitivity analyzes using as response or output functions the reproduction number (), the infected humans (), the infected rodents (), the sum of infected D. variablis ticks at all life stages (), and the sum of infected A. americanum ticks at all life stages () to identify the parameters with the most impact on these functions in no particular order are: the most significant parameters related infected humans are the birth, death, and disease induced death rates (, ), human disease progression rate (), and the recovery rate (); the most significant parameters related to infected rodents are rodent birth, death, and disease induced death rates (, , ), rodent transmission probability () to A. americanum. The significant parameters related D. variablis are eggs maturation () and in-viability () rates, the larvae maturation () and mortality () rates, the nymphs maturation rate (), and the adult mortality rate (). The significant parameters related to A. americanum are its carrying capacity (), the eggs maturation () rate, the larvae maturation rate (), and the nymphs maturation () rate, its adult death rate (, and the transmission probability () to rodents.

- (ii)

- Prescribed fire can reduce the number of ticks leading to a reduction in the number of tularemia infected humans, rodents and ticks.

- (iii)

- A. americanum produced more tulareamia infection in humans and rodents than D. variablis due to the differential effect of prescribed fire which leaves more A. americanum than D. variablis after a burn.

- (iv)

- As time between burn increases, more infected humans, rodents, and ticks increases. Frequent burning reduces the number of ticks and therefore infections.

- (v)

- The spatial arrangement of UBB and BUB areas may not matter as either arrangement led to fewer ticks and reduction in tularemia transmission with the implementation of prescribed fire.

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Proof of Lemma 1

Appendix B. Proof of Lemma 2

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Tularaemia: Annual epidemiological report for 2019. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/tularaemia-annual-epidemiological-report-2019, 2021. Accessed: 2023-12-14.

- Azmy, S. Ackleh and Amy Veprauskas. Modeling the invasion and establishment of a tick-borne pathogen. Ecological modelling, 467:109915, 2022.

- Molly Adams. KU professor leads students in prescribed burn at Lecompton prairie. https://lawrencekstimes.com/2023/11/29/cultural-burn-winter-school/, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-28.

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). Tularemia facts. https://www.avma.org/tularemia-facts, 2003. Accessed: 2023-12-15.

- R.M. Anderson and R. May. Infectious Diseases of Humans. Oxford University Press, New York., 1991.

- Dmitry, A. Apanaskevich, J. H. Oliver, D. E. Sonenshine, and R. M. Roe. Life cycles and natural history of ticks. Biology of ticks, 1:59–73, 2014.

- R. B. Atherton, R. W. Schainker and E. R. Ducot. On the statistical sensitivity analysis of models for chemical kinetic. AIChE Journal, 21(3):441–448, 1975.

- Stina Bäckman, Jonas Näslund, Mats Forsman, and Johanna Thelaus. Transmission of tularemia from a water source by transstadial maintenance in a mosquito vector. Scientific reports, 5(1):7793, 2015.

- Genel Bir Bakış. A general overview of francisella tularensis and the epidemiology of tularemia in turkey. Flora, 15(2):37–58, 2010.

- Blyssalyn V Bieber, Dhaval K Vyas, Amanda M Koltz, Laura A Burkle, Kiaryce S Bey, Claire Guzinski, Shannon M Murphy, and Mayra C Vidal. Increasing prevalence of severe fires change the structure of arthropod communities: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Functional Ecology, 37(8):2096–2109, 2023.

- S. M. Blower and H. I. Dowlatabadi. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex models of disease transmission: an hiv model, as an example. International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale de Statistique, pages 229–243, 1994.

- N. Boulanger, P. Boyer, E. Talagrand-Reboul, and Y. Hansmann. Ticks and tick-borne diseases. Medecine et maladies infectieuses, 49(2):87–97, 2019.

- David M. J. S. Bowman, Jennifer K. Balch, Paulo Artaxo, William J. Bond, Jean M. Carlson, Mark A. Cochrane, Carla M. D’Antonio, Ruth S. DeFries, John C Doyle, and Sandy P Harrison. Fire in the earth system. science, 324(5926):481–484, 2009.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tularemia: United states, 1990-2000. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 51(9):181–184, 2002.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Births and natality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-06.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Deaths and mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-06.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Tularemia. https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/tularemia/faq.asp#:~:text=Tularemia%2C%20also%20known%20as%20%E2%80%9Crabbit,all%20U.S.%20states%20except%20Hawaii., 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Tickborne disease surveillance data summary. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/data-summary/index.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-09-17.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Ticks: Tickborne disease surveillance data summary. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/data-summary/index.html#print, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-14.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Tularemia. https://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/index.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-17.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Tularemia: Diagnosis & treatment. https://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/diagnosistreatment/index.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Tularemia: For Clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/clinicians/index.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Tularemia: Signs & symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/signssymptoms/index.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-09-17.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). Tularemia: Transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/transmission/index.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-15.

- Nakul Chitnis, James M. Hyman, and Jim M. Cushing. Determining important parameters in the spread of malaria through the sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model. Bulletin of mathematical biology, 70(5):1272–1296, 2008.

- Cleveland Clinic. Tularemia. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17775-tularemia, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Columbia University, Lyme and Tick-Borne Diseases Research Center. Tularemia. https://www.columbia-lyme.org/tularemia, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- L. M. Cooksey, D. G. Haile, and G. A. Mount. Computer simulation of rocky mountain spotted fever transmission by the american dog tick (acari: Ixodidae). Journal of medical entomology, 27(4):671–680, 1990.

- Max Diaz. Exploring the Benefits of Prescribed Fire. https://www.columbialandtrust.org/exploring-the-benefits-of-prescribed-fire/, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-28.

- O. Diekmann, J. A. P. Heesterbeek, and J. A. P. Metz. On the definition and computation of the basic reproduction ratio r0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 28:503–522, 1990.

- Katherine J. Elliott, Ronald L. Hendrick, Amy E. Major, James M. Vose, and Wayne T. Swank. Vegetation dynamics after a prescribed fire in the southern appalachians. Forest Ecology and Management, 114(2-3):199–213, 1999.

- J. Ellis, P. C. Oyston, M. Green, and R. W. Titball. Tularemia. Clin Microbiol Rev, 15:631–646, 2002.

- Peter D. Fowler, S. Nguyentran, L. Quatroche, M. L. Porter, V. Kobbekaduwa, S. Tippin, Guy Miller, E. Dinh, E. Foster, and J. I. Tsao. Northward expansion of amblyomma americanum (acari: Ixodidae) into southwestern michigan. Journal of Medical Entomology, 59(5):1646–1659, 2022.

- A. Fulk and F. B. Agusto. Effects of rising temperature and prescribed fire on amblyomma americanum with ehrlichiosis. medRxiv, pages 2022–11, 2022.

- A. Fulk, W. Huang, and F. B. Agusto. Exploring the effects of prescribed fire on tick spread and propagation in a spatial setting. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2022, 2022.

- Holly Gaff and Elsa Schaefer. Metapopulation models in tick-borne disease transmission modelling. Modelling parasite transmission and control, pages 51–65, 2010.

- Holly D. Gaff and Louis J. Gross. Modeling tick-borne disease: a metapopulation model. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 69:265–288, 2007.

- M. E. Gilliam, Will T. Rechkemmer, K. W. McCravy, and S. E. Jenkins. The influence of prescribed fire, habitat, and weather on Amblyomma americanum (Ixodida: Ixodidae) in West-Central Illinois, USA. Insects, 9(2):36, 2018.

- E. R. Gleim, L. M. Conner, R. D. Berghaus, M. L. Levin, G. E. Zemtsova, and M. J. Yabsley. The phenology of ticks and the effects of long-term prescribed burning on tick population dynamics in southwestern Georgia and northwestern Florida. PLoS One, 9(11):e112174, 2014.

- Elizabeth R. Gleim, Galina E. Zemtsova, Roy D. Berghaus, Michael L. Levin, Mike Conner, and Michael J. Yabsley. Frequent prescribed fires can reduce risk of tick-borne diseases. Scientific reports, 9(1):9974, 2019.

- E. Guo and F. B. Agusto. Baptism of fire: Modeling the effects of prescribed fire on lyme disease. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology, 2022, 2022.

- Gürcan. Epidemiology of tularemia. Balkan medical journal, 2014(1):3–10, 2014.

- D.M. Hamby. A review of techniques for parameter sensitivity analysis of environmental models. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 32(2):135–154, 1994.

- M. J. Hepburn and A. J. H. Simpson. Tularemia: current diagnosis and treatment options. Expert review of anti-infective therapy, 6(2):231–240, 2008.

- G. Hestvik, E. Warns-Petit, L. A. Smith, N. J. Fox, H. Uhlhorn, M. Artois, D. Hannant, M. R. Hutchings, R. Mattsson, and L. Yon. The status of tularemia in europe in a one-health context: a review. Epidemiology & Infection, 143(10):2137–2160, 2015.

- H. W. Hethcote. The mathematics of infectious diseases. SIAM Review, 42(4):599–653, 2000.

- J. Kevin Hiers, Joseph J. O’Brien, J. Morgan Varner, Bret W. Butler, Matthew Dickinson, James Furman, Michael Gallagher, David Godwin, Scott L. Goodrick, and Sharon M. Hood. Prescribed fire science: The case for a refined research agenda. Fire Ecology, 16:1–15, 2020.

- C. E. Hopla. The ecology of tularemia. Advances in veterinary science and comparative medicine, 18:25–53, 1974.

- Illinois Department of Public Health. Tularemia. https://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/emergency-preparedness-response/public-health-care-system-preparedness/tularemia, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Sonja Kittl, Thierry Francey, Isabelle Brodard, Francesco C. Origgi, Stéphanie Borel, Marie-Pierre Ryser-Degiorgis, Ariane Schweighauser, and Joerg Jores. First european report of francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica isolation from a domestic cat. Veterinary research, 51(1):1–5, 2020.

- C. J. Krebs. Ecological methodology. Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc., 1989.

- Deepak Kumar, Surendra Raj Sharma, Abdulsalam Adegoke, Ashley Kennedy, Holly C. Tuten, Andrew Y. Li, and Shahid Karim. Recently evolved francisella-like endosymbiont outcompetes an ancient and evolutionarily associated coxiella-like endosymbiont in the lone star tick (amblyomma americanum) linked to the alpha-gal syndrome. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 12:425, 2022.

- Marilynn A. Larson, Khalid Sayood, Amanda M. Bartling, Jennifer R. Meyer, Clarise Starr, James Baldwin, and Michael P. Dempsey. Differentiation of francisella tularensis subspecies and subtypes. Journal of clinical microbiology, 58(4):10–1128, 2020.

- Y. Lou, L. Liu, and D. Gao. Modeling co-infection of ixodes tick-borne pathogens. Mathematical Biosciences & Engineering, 14(5&6):1301, 2017.

- A. Ludwig, H.S. Ginsberg, G.J. Hickling, and N.H. Ogden. A dynamic population model to investigate effects of climate and climate-independent factors on the lifecycle of amblyomma americanum (acari: Ixodidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 53(1):99–115, 2016.

- Milliward Maliyoni, Faraimunashe Chirove, Holly D. Gaff, and Keshlan S. Govinder. A stochastic tick-borne disease model: Exploring the probability of pathogen persistence. Bulletin of mathematical biology, 79:1999–2021, 2017.

- Marino, I. B. Hogue, C. J. Ray, and D. E. Kirschner. A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. Journal of theoretical biology, 254(1):178–196, 2008.

- M. D. McKay, R. J. Beckman, and W. J. Conover. A comparison of three methods for selecting values of input variables in the analysis of output from a computer code. Technometrics, 42(1):55–61, 2000.

- Laura K. McMullan, Scott M. Folk, Aubree J. Kelly, Adam MacNeil, Cynthia S. Goldsmith, Maureen G. Metcalfe, Brigid C. Batten, César G. Albariño, Sherif R. Zaki, and Pierre E. Rollin. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in missouri. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(9):834–841, 2012.

- Medscape. Tularemia. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/230923-overview?form=fpf, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- T. Mörner. The ecology of tularaemia. Revue scientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics), 11(4):1123–1130, 1992.

- Torsten Mörner and Edward Addison. Tularemia. Infectious diseases of wild mammals, pages 303–312, 2001.

- G. A. Mount and D. G. Haile. Computer simulation of population dynamics of the american dog tick (acari: Ixodidae). Journal of medical entomology, 26(1):60–76, 1989.

- H. G. Mwambi, J. Baumgärtner, and K. P. Hadeler. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a vector-host interaction model for the brown ear tick (rhipicephalus appendiculatus). Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 9(3):279–301, 2000.

- R. Norman, R.G. Bowers, M. Begon, and .J. Hudson. Persistence of tick-borne virus in the presence of multiple host species: tick reservoirs and parasite mediated competition. Journal of theoretical biology, 200(1):111–118, 1999.

- F. Occhibove, K. Kenobi, M. Swain, and C. Risley. An eco-epidemiological modeling approach to investigate dilution effect in two different tick-borne pathosystems. Ecological Applications, 32(3):e2550, 2022.

- K. A. Padgett, L. E. Casher, S. L. Stephens, and R. S. Lane. Effect of prescribed fire for tick control in california chaparral. Journal of Medical Entomology, 46(5):1138–1145, 2009.

- Stephen R. Palmer, Lord Soulsby, and David Ian Hewitt Simpson. Zoonoses: biology, clinical practice, and public health control. Oxford university press, 1998.

- Emily L. Pascoe, Matteo Marcantonio, Cyril Caminade, and Janet E. Foley. Modeling potential habitat for amblyomma tick species in california. Insects, 10(7):201, 2019.

- Robert, L. Penn. Francisella tularensis (tularemia). In Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, pages 2590–2602. Elsevier, 2015.

- Paola Pilo. Phylogenetic lineages of francisella tularensis in animals. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 8:258, 2018.

- M. A. Sanchez and S. M. Blower. Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis of the basic reproductive rate: tuberculosis as an example. American Journal of Epidemiology, 145(12):1127–1137, 1997.

- Harry M. Savage, Kristen L. Burkhalter, Marvin S. Godsey Jr, Nicholas A. Panella, David C. Ashley, William L. Nicholson, and Amy J. Lambert. Bourbon virus in field-collected ticks, missouri, usa. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 23(12), 2017.

- A Sjöstedt. Family xvii. francisellaceae, genus i., 2005.

- J. Snowden and K. A. Simonsen. Tularemia. https://europepmc.org/books/n/statpearls/article-30676/?extid=28613501&src=med, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- State of New Jersey, Department of Agriculture. Tularemia. https://www.nj.gov/agriculture/divisions/ah/diseases/tularemia.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Bei Sun, Xue Zhang, and Marco Tosato. Effects of coinfection on the dynamics of two pathogens in a tick-host infection model. Complexity, 2020:1–14, 2020.

- Olivia Tardy, Catherine Bouchard, Eric Chamberland, André Fortin, Patricia Lamirande, Nicholas H. Ogden, and Patrick A. Leighton. Mechanistic movement models reveal ecological drivers of tick-borne pathogen spread. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 18(181):20210134, 2021.

- A. Tärnvik and M. C. Chu. New approaches to diagnosis and therapy of tularemia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1105(1):378–404, 2007.

- Danielle M. Tufts, Ben Adams, and Maria A. Diuk-Wasser. Ecological interactions driving population dynamics of two tick-borne pathogens, borrelia burgdorferi and babesia microti. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 290(2001):20230642, 2023.

- US Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Prescribed fire. https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/prescribed-fire, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-10.

- P. Van den Driessche and J. Watmough. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical biosciences, 180(1):29–48, 2002.

- J. Morgan Varner, Mary A. Arthur, Stacy L. Clark, Daniel C. Dey, Justin L. Hart, and Callie J. Schweitzer. Fire in eastern north american oak ecosystems: filling the gaps. Fire Ecology, 12:1–6, 2016.

- VOA News. 'Prescribed Burns' Could Aid Forests in US Southeast, Experts Say. https://www.voanews.com/a/prescribed-burns-could-aid-forests-in-us-southeast-experts-say-/7399183.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-28.

- Robert J. Whelan. The ecology of fire. Cambridge university press, 1995.

- Michael C. Wimberly, Adam D. Baer, and Michael J. Yabsley. Enhanced spatial models for predicting the geographic distributions of tick-borne pathogens. International Journal of Health Geographics, 7(1):1–14, 2008.

- Derya Karataş Yeni, Fatih Büyük, Asma Ashraf, and M. Salah ud Din Shah. Tularemia: a re-emerging tick-borne infectious disease. Folia microbiologica, 66(1):1–14, 2021.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Number of susceptible humans | |

| Number of exposed humans | |

| Number of asymptomatic humans | |

| Number of infected humans | |

| Number of recovered humans | |

| Number of susceptible rodents | |

| Number of infected rodents | |

| Number of susceptible eggs of ticks type | |

| Number of susceptible larvae of ticks type i | |

| Number of infected larvae of ticks type i | |

| Number of susceptible nymphs of ticks type i | |

| Number of infected nymphs of ticks type i | |

| Number of susceptible adults of ticks type i | |

| Number of infected adults of ticks type i |

| Parameter | Description | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human birth rate | 0.011 | [15] | |

| Tick 1-to-human transmission probability | 0.2 | [28] | |

| Tick 2-to-human transmission probability | 0.1 | [35] | |

| Disease progression rate | 1/21–1 | [17,22,26,75,76] | |

| p | Proportion infectious | 0.04-–0.19 | [9,42] |

| Human recovery rate | 1/21–1/10 | [21,49] | |

| Human natural death rate | 0.0104 | [16] | |

| Human disease-induced death rate | 0.03–0.3 | [49,60,76] | |

| Rodent birth rate | 0.02 | [54] | |

| Rodent-to-tick 1 transmission probability | 0.2 | [28] | |

| Rodent-to-tick 2 transmission probability | 0.1 | [35] | |

| Rodent death rate | 0.01 | [54] | |

| Rodent disease-induced death rate | 0.01 | [54] | |

| Birth rate of tick 1 (Demacenta variablis) | 4,500 | [63] | |

| Carrying capacity for tick 1 | 10,000 | assumed | |

| Tick 1-to-rodent transmission probability | 0.2 | [28] | |

| Maturation rate of egg to larva for tick 1 | 0.2 | assumed | |

| Maturation rate of larva to nymph for tick 1 | 0.2 | assumed | |

| Maturation rate of nymph to adult for tick 1 | 0.2 | assumed | |

| Eggs in-viability rate of tick 1 | 0.0174 | [63] | |

| Mortality rate of the larvae of tick 1 | 0.0294 | [63] | |

| Mortality rate of the nymph of tick 1 | 0.0296 | [63] | |

| Mortality rate of the adult of tick 1 | 0.0137 | [63] | |

| Birth rate of tick 2 (Amblyomma americanum) | 6,000 | [34,55] | |

| Carrying capacity for tick 2 | 120,000 | assumed | |

| Tick 2-to-rodent transmission probability | 0.1 | [35] | |

| Maturation rate of egg to larva for tick 2 | 0.2 | [34,55] | |

| Maturation rate of larva to nymph for tick 2 | 0.2 | [34,55] | |

| Maturation rate of nymph to adult for tick 2 | 0.2 | [34,55] | |

| Eggs in-viability rate of tick 2 | 0.008 | [34,55] | |

| Mortality rate of the larvae of tick 2 | 0.005 | [34,55] | |

| Mortality rate of the nymph of tick 2 | 0.004 | [34,55] | |

| Mortality rate of the adult of tick 2 | 0.003 | [34,55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).