Introduction

In Western societies, such as the United States, adults typically derive approximately half of their daily caloric intake from dietary carbohydrates, as stipulated by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans [

1]. This authoritative source recommends that carbohydrates should comprise between 45% and 65% of the total daily caloric intake for individuals aged 2 years and older [

1]. Conversely, in certain regions, particularly within Asia, there is a higher prevalence of carbohydrate consumption. This phenomenon presents challenges in glycemic control, as some data suggests that identical food items may elicit a slightly elevated postprandial (PP) glucose response and a less favorable insulin response in comparison to Caucasians [

2].

Sugar laden diets and fast absorbing carbohydrates increase the risk of weight gain, insulin resistance, diabetes, cardiovascular and metabolic disorders [

3]. Studies indicate that a low glycaemic diet (GI) and certain lifestyle modifications can regulate HbA1c, body mass index and lipid profiles in the people with type-2 diabetes [

4]. Earlier studies indicate that a low GI diet intake can prevent gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) related complications like macrosomia and significantly reduce fasting and postprandial glucose levels [

5]. More importantly, the low GI diet can reduce the risk of insulin usage [

6]. A recently completed review of nutrition and its impact on T2DM concluded that dietary restriction of carbohydrate intake is the single most effective approach to manage T2DM [

7].

Mulberry leaves are traditionally used in Asian subcontinent to lower postprandial blood sugar levels [

8,

9]. Several clinical studies have shown the positive benefit of mulberry leaf extracts on postprandial sugar spikes in healthy as well as diabetic individuals [

10,

11,

12]. The active component of mulberry extract is 1-DNJ (imniosugars) and alkaloids, work by temporarily blocking the enzymes pancreatic alpha glucosidase and amylase [

13,

14]. Acarbose, an amino oligosaccharide isolated from the fermentation broth of

Actinoplanes sp., is another product that has a similar mechanism of action i.e., inhibits brush-border α-glucosidases in humans. Acarbose however has adverse effects such as abdominal distention, flatulence and possibly diarrhea. Such adverse effects are attributed to the impaired digestion of starch by strong inhibition of intestinal α-amylase [

15].

The major advantage of mulberry extract over Acarbose is less gastrointestinal side effects and lack of drug resistance [

14]. The

in vitro inhibitory activity of mulberry leaf extract (MLE) on intestinal α-glucosidase was potent and that on intestinal α-amylase was weak compared to acarbose [

16]. Additionally, our earlier findings and others have demonstrated that mulberry extracts promote insulin sensitivity and reduce insulin resistance by inhibiting the enzyme protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), a master regulator that mediates a cascade of events, which induce insulin resistance and is known to be elevated in prediabetics and diabetics [

17]. Moreover, mulberry bio actives have potential to enhance glucose uptake by activating insulin dependent and independent mechanisms, thereby reducing fasting and random blood glucose levels in diabetics [

18]. Green apples are rich in polyphenols and phytoactives (phlorizin and phloridzin) traditionally known to reduce postprandial blood sugar levels. It works by reducing the uptake of glucose at the brush border of the intestine [

19].

Together, mulberry leaf extract and green apple extract have demonstrated synergistic benefits and were found to reduce postprandial sugar surge caused by high carb meal or a sucrose drink intake in healthy individuals [

20]. In the current study, we have demonstrated the impact of a commercially available nutraceutical, Glubloc™ (a standardised blend of white mulberry leaf extract and green apple peel extract) on postprandial blood sugar spike and insulin levels in healthy individuals post carbohydrate and sugar rich meal intake.

Study design and Objectives:

This is a randomised, placebo controlled, crossover study, participants include 30 healthy south Indian subjects (both male and female), aged between 18–60 years, BMI between 20 and 29.9 kg/m

2 with fasting blood glucose levels ≤ 5.7 mmol/l (or) ≤ 99 mg/dl. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, Medicover Hospitals and prospectively registered under Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI), with approval number CTRI/2023/08/056330. The study took place at the inpatient department of Medicover hospital, Hitech City, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. Glubloc™ tablets (a proprietary blend of Mulberry leaf extract and Apple peel extract) were provided by My PuraVida Wellness Pvt Ltd (Telangana, India). Placebo tablet was similar in color and taste to the Glubloc™, without the actives. The exclusion criteria of the Glubloc™ trial are listed in

Table 1.

Exclusion criteria:

History of hypersensitivity to any of the investigational product, excipients, or any known food allergies.

Pre-existing medical conditions or taking medication known to affect glucose regulation and/or influence digestion and absorption of nutrients.

History of diabetes mellitus (type I/II) or they used antihyperglycemic drugs or insulin to treat diabetes or related conditions.

Used steroids, protease inhibitors or antipsychotic medicines as these drugs are known to impact glucose metabolism and body fat distribution.

Subjects with the history of uncontrolled hypertension and/or hyperthyroidism.

History of alcoholism

Subjects with psychiatric or neurological disability or mental health disorder

Subjects with serious health conditions such as cardiac disease, renal dysfunction, and cancers.

Female subjects who are pregnant or had planned for pregnancy in the following months or were breast-feeding.

Subjects who refuse to sign informed consent.

According to the investigator’s opinion, participants who are deemed unable to comply with the test requirements or otherwise deemed unsuitable.

Objectives of the study

The primary objective is aimed at understanding the impact of Glubloc™ supplementation on the changes in blood glucose and insulin levels post carbohydrate and sugar rich meal intake. The secondary objective is to record the occurrence of bloating or any gastrointestinal symptoms during the study.

Study Methods

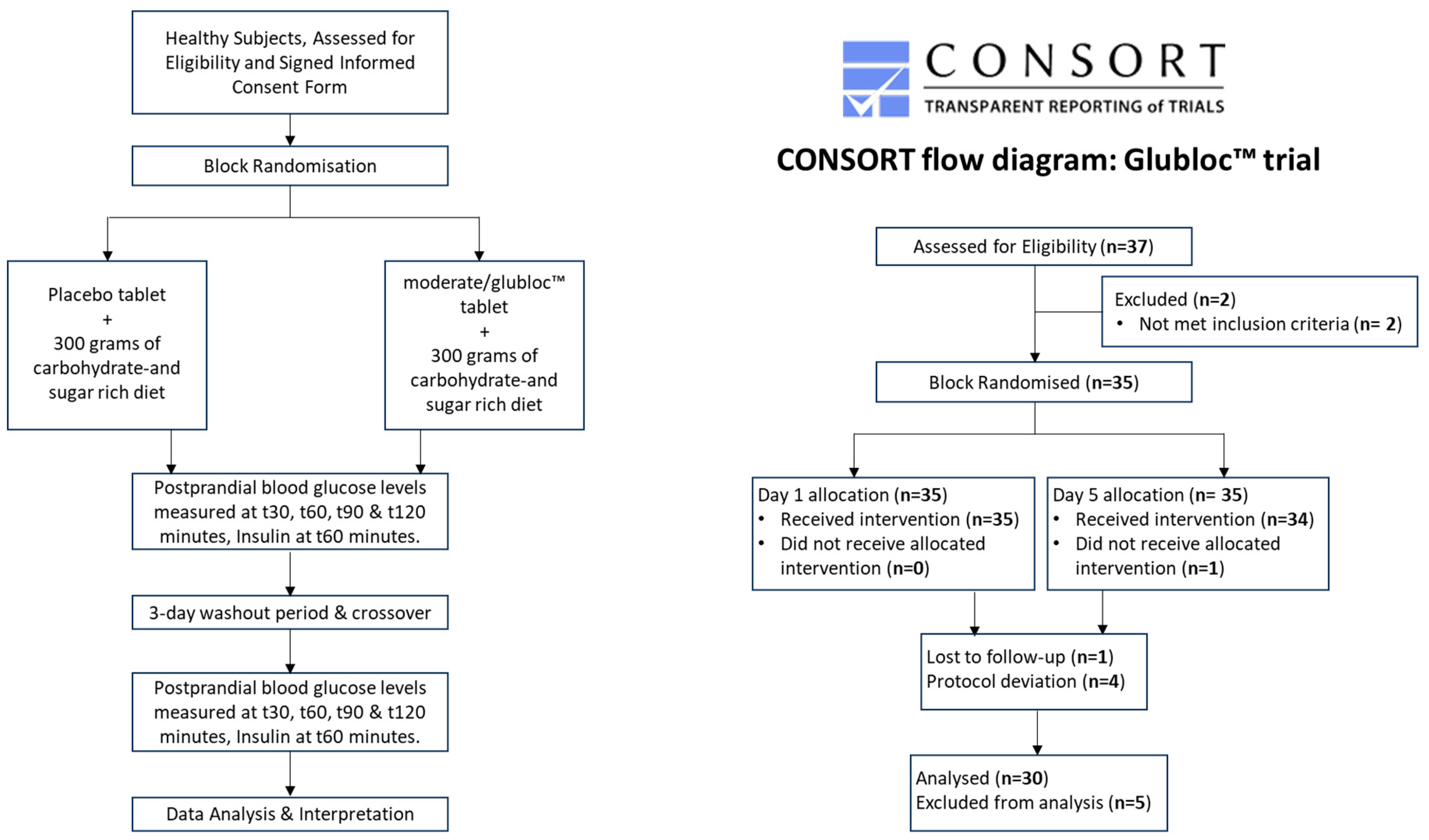

The glycaemic response method used was adapted from that described by Brouns et al [26] and was carried out in accordance with the ISO 26642:2010(E) standards. Following an overnight fast for at least 10 hours, subjects were allocated to placebo and Glubloc™ arms via block randomisation (15 subjects per each arm). Baseline (0 min) reading of blood glucose levels were recorded using Accu-Chek® Active blood glucometer (F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG), they were administered placebo or Glubloc™ tablets 10 minutes before the meal, taken orally with a glass of water. Subjects were asked to eat 300 grams of carbohydrate-and sugar rich meal (250g of Poha with 50 g of Gulab jamun mix, ~600 kilocalories), within 15 minutes or less. Blood glucose levels were measured at t30, t60, t90 & t120 minutes using Accu-Chek® Active blood glucometer (F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG). Venous blood sample of 3 ml was collected at t60 minutes to assess serum insulin levels. The test was repeated after 3 days with the opposite treatment.

Sample size

Based on the earlier clinical studies on Morus alba, we estimated a sample size of n = 30 participants would provide over 90% power to detect a similar effect size. By adopting a more conservative approach and permitting a narrower margin for detection, a cohort of 30 participants would still afford a minimum of 80% statistical power in discerning a 25% variance in the Incremental Area Under the Curve (iAUC). In order to account for a potential loss to follow up, we aimed to recruit 35 participants.

Statistical Analysis.

The significance of differences in blood glucose levels between Glubloc™ and placebo was determined by ANOVA of values obtained over the initial 120 min. Total iAUC0-120 and cumulative iAUC were calculated using trapezoidal rule. Paired t-test was used to test the effects of placebo versus Glubloc™ treatments on blood glucose and insulin levels. If the effect was found to be significant by ANOVA, multiple comparison of LSD was used to test the difference between the treatments. All tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was set at 0.05 (P<0.05).

Results

Of 35 randomised subjects, one participant dropped out citing personal reasons, one subject was not able to finish eating the food, three subjects deviated from the study protocol on their second visit. Recruitment began in August 2023 and the study was closed at the end of September 2023 with 30 participants having completed both the visits.

Figure 1 depicts the trial flow diagram.

Incremental area under the curve (iAUC) was calculated for all glucose measurements from baseline to 120 minutes in accordance with FAO/WHO’s ‘Joint Guidelines on glycaemic index testing of foods and the International Standard ‘ISO 26642/2010: Food Products–determination of the glycaemic index (GI) and recommendation for food classification’.

Changes in postprandial blood glucose levels

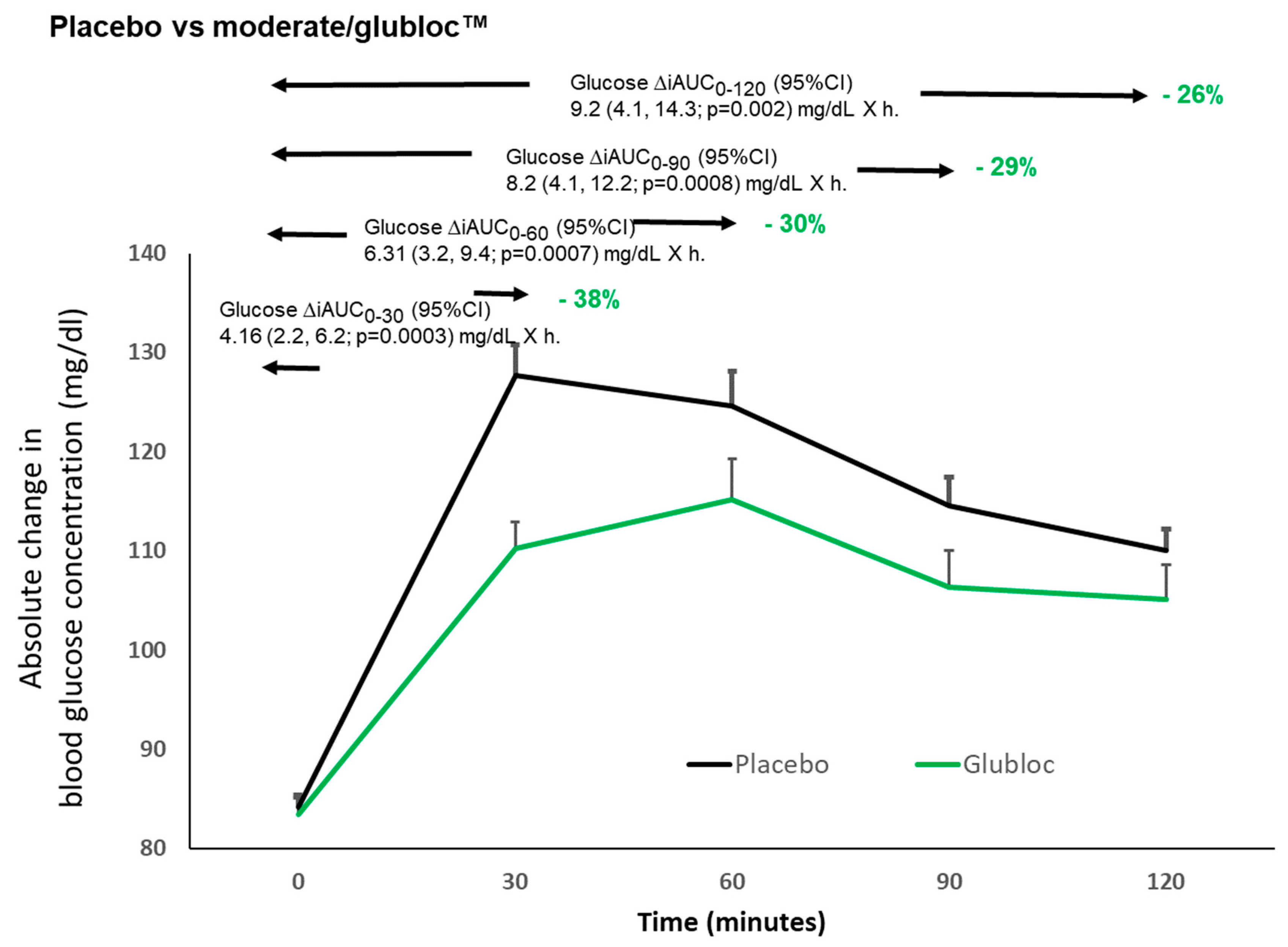

The change in postprandial blood glucose levels in the Glubloc™ and placebo groups are shown in

Figure 2. The value on the vertical axis represents absolute change in postprandial blood glucose levels. The Glubloc™ group showed a reduction in the iAUC of blood glucose after the meal compared to the placebo treated group at 0.5 h (− 38%, p < 0.0003), 1 h (− 30%, p = 0.0007), 1.5 h (− 29%, p = 0.0008), and 2.0 h (− 26%, p = 0.002). Throughout the study, a trend toward a lower cumulative iAUC was observed in the Glubloc™ versus placebo group. The Cmax was 136.5 ± 2.7 mg/dL in the placebo group versus 120.5 ± 1.9 mg/dL in the Glubloc™ group (

Table 2). Postprandial blood glucose levels peaked at Tmax, 46.2 ± 5.3 min and 63.75 ± 6.5 min in placebo and Glubloc™ groups, respectively (

Table 3). indicating the tendency of the latter to delay and lower the peak blood glucose level.

Where, xi = a+iΔx

If n →∞, R.H.S of the expression approaches the definite integral ∫ab f(x)dx.

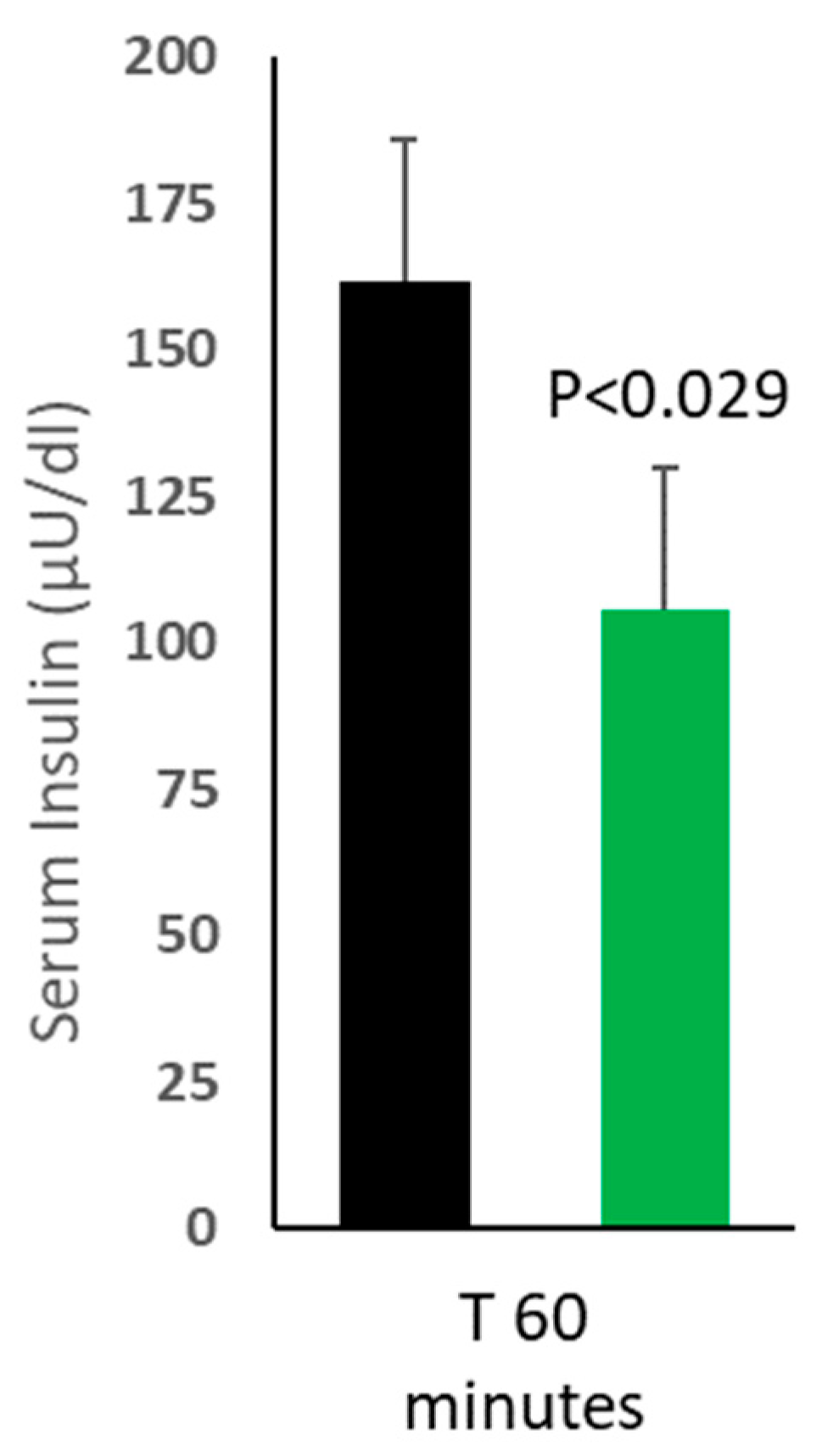

Changes in the postprandial serum insulin levels:

Increase in postprandial insulin levels indicate the surge in blood glucose levels, which trigger the release of insulin from the pancreas to enhance the glucose uptake and generate ATP by key organs and helps maintain blood glucose levels. Postprandial serum insulin levels were found to be significantly lower in Glubloc™ group versus placebo group at T 60 minutes (P<0.029).

Gastrointestinal symptoms:

Table 4 below sets out the percentage of subjects experiencing any gastrointestinal symptoms. These were recorded as nausea, abdominal cramping, distension or flatulence. None of the subjects from both the groups experienced GI related side effects during the study and the rest of the day.

Discussion

White mulberry leaf and green apple peel are two natural ingredients, that have shown to reduce postprandial blood glucose levels by regulating the digestion of the carbohydrates and by modulating the uptake of glucose at the brush border of the intestine. The individual capabilities were demonstrated in various randomised clinical studies [

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In this randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover study, carried out in healthy normoglycaemic individuals, we have demonstrated the efficacy of a combined extract of white mulberry leaf and green apple peel (Glubloc™) on postprandial glucose and insulin levels. Moreover, with Glubloc™ supplementation, we did not observe any incidence of GI side effects and no subjects dropped out of the study due to side effects or adverse events.

Mulberry leaf extract not only directly affects α-glucosidase and related enzymes, and influence carbohydrate metabolism and absorption [

13,

24]. Its ability to moderate insulin spikes is noteworthy, given the direct correlation between elevated systemic insulin levels and increased whole-body glucose uptake [

27]. It's worth emphasizing that suppressing insulin secretion, without dietary or exercise intervention, can lead to weight loss and reduced adipose tissue production [

28]. Studies show that prolonged mulberry leaf administration results in a dose-dependent decrease in body weight gain and hepatic lipid accumulation in mice [

12].

Green apple peel is rich in hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (HZDs), dihydrochalcones, flavanols, flavonols, and anthocyanins. The five major (poly)phenol groups include flavan-3-ols/procyanidins (epicatechin and procyanidins), phenolic acids (chlorogenic acid), dihydrochalcones (phloridzin), flavonols (quercetin glycosides), and anthocyanins (cyanidin 3-galactoside) [

29]. Specifically, dietary (poly)phenols are responsible for the inhibition of critical polysaccharide and disaccharide digestive enzymes like pancreatic α-amylase and α-glucosidase thereby delaying glucose absorption into the bloodstream [

29,

30].

Intake of mulberry leaf and apple peel extract complex (Glubloc™) before a high carbohydrate, sugar rich meal significantly reduced the blood glucose levels when compared to placebo treatment, observed over the initial 120 min of testing in healthy individuals. The sugar spike at 30 minutes, observed in placebo group became gradual and peaked at 60 min with Glubloc™ intake (

Figure 2). The reduction in blood glucose spike presumably reflects the ability of Glubloc™ to inhibit intestinal glucosidase and amylase. In line with blood sugar levels, serum insulin levels were identified to be significantly less in Glubloc™ group (

Figure 3), response to less blood glucose entering the body.

Since mulberry leaf and apple peel extracts contains bio actives (flavonoids, iminosugars and chalcone derivatives like 1-deoxynojirimycin, cyanidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin-3-rutinoside, resveratrol and oxyresveratrol) specific to α-glucosidase inhibition and being a weak amylase inhibitor [

15], no gastrointestinal side effects like bloating, gas or diarrhoea were observed during the study. This overrides the limitation of two known drugs (acarbose and miglitol), use of these drugs was limited due to gastrointestinal irritation, bloating, gas, and diarrhoea.

Mulberry leaf extract has other major benefits over acarbose or miglitol, which includes improved insulin sensitivity by inhibiting the enzyme PTP-1B [

17,

31], it contains compounds such as fagomine, which induces insulin secretion, promotes glucose uptake in cells by activating insulin dependent and insulin independent pathways, long term improvements in HbA1C levels and reduced lipid peroxidation [

8,

10,

12,

17,

18].

Mulberry leaf and apple peel are considered safe for human consumption and categorised as foodstuffs/nutraceuticals in India and other Asian countries by their regulatory bodies due to their long history of traditional usage [

15].

Conclusions

Glubloc™ reduced and delayed postprandial glucose spike and overall blood glucose levels after a calorie rich, high carbohydrate and high sugar meal intake. Importantly, postprandial insulin rise was also significantly suppressed, determined at 60 minutes. No gastrointestinal symptoms or side effects were reported during the study. Glubloc™ may have multiple modes of action and further studies are necessary to evaluate its potential to manage type 2 diabetes and dysglycaemia.

Limitations

The study was conducted in healthy subjects with a specific south Indian diet, which is high calorie, and loaded with carbohydrates and sucrose. The results may vary with different diets prepared with a combination of carbohydrates and sugars with protein rich or fat rich ingredients as Glubloc™ can limit only the digestion and uptake of polysaccharides and disaccharides. Additional limitations of this study include single dosing only in relation to a single meal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.C.G., Methodology, S.P.G., M.K., Investigation, S.P.G., D.B., M.S. Data Curation, D.B., M.S., S.P.G. Writing, Review and Editing, S.P.G., M.K., D.B., M.S. All the authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the internal grants of My Pura Vida Wellness Pvt Ltd, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

Declaration of Competing Interest

C.C.G., represents the sponsor of the study, My PuraVida Wellness Pvt Ltd. The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We thank the technical support of Medicover Hospitals for glucose and insulin studies and analysis. We thank all participants of the study.

References

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 2020; 9th.,. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf.

- Wee MSM, Henry CJ. Reducing the glycemic impact of carbohydrates on foods and meals: Strategies for the food industry and consumers with special focus on Asia. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safe 2020; 19: 670–702. [CrossRef]

- Stanhope KL. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 2016; 53: 52–67. [CrossRef]

- Sabarathinam S. A glycemic diet improves the understanding of glycemic control in diabetes patients during their follow-up. Future Science OA 2023; 9: FSO843. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen L, Poulsen CW, Kampmann U, et al. Diet and Healthy Lifestyle in the Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2020; 12: 3050. [CrossRef]

- Radulian G, Rusu E, Dragomir A, et al. Metabolic effects of low glycaemic index diets. Nutr J 2009; 8: 5. [CrossRef]

- Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base. Nutrition 2015; 31: 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Jiang W, Bai H, et al. Study on active components of mulberry leaf for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular complications of diabetes. Journal of Functional Foods 2021; 83: 104549. [CrossRef]

- Jeong HI, Jang S, Kim KH. Morus alba L. for Blood Sugar Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022; 2022: 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Thaipitakwong T, Supasyndh O, Rasmi Y, et al. A randomized controlled study of dose-finding, efficacy, and safety of mulberry leaves on glycemic profiles in obese persons with borderline diabetes. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2020; 49: 102292. [CrossRef]

- Kim JY, Ok HM, Kim J, et al. Mulberry Leaf Extract Improves Postprandial Glucose Response in Prediabetic Subjects: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Journal of Medicinal Food 2015; 18: 306–313. [CrossRef]

- Lown M, Fuller R, Lightowler H, et al. Mulberry-extract improves glucose tolerance and decreases insulin concentrations in normoglycaemic adults: Results of a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. PLoS ONE 2017; 12: e0172239. [CrossRef]

- Danuri HM, Lestari WA, Sugiman U, et al. In Vitro α-Glucosidase Inhibition and Antioxidant Activity of Mulberry (Morus Alba L.) Leaf Ethanolic Extract. Jgizipangan 2020; 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Mudra M, Ercan-Fang N, Zhong L, et al. Influence of Mulberry Leaf Extract on the Blood Glucose and Breath Hydrogen Response to Ingestion of 75 g Sucrose by Type 2 Diabetic and Control Subjects. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1272–1274. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Huang X, Ye H, et al. Randomized, Double-Blinded, Double-Dummy, Active-Controlled, and Multiple-Dose Clinical Study Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of Mulberry Twig (Ramulus Mori, Sangzhi) Alkaloid Tablet and Acarbose in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2016; 2016: 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kim G-N, Kwon Y-I, Jang H-D. Mulberry Leaf Extract Reduces Postprandial Hyperglycemia with Few Side Effects by Inhibiting α-Glucosidase in Normal Rats. Journal of Medicinal Food 2011; 14: 712–717. [CrossRef]

- Paudel P, Yu T, Seong S, et al. Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B Inhibition and Glucose Uptake Potentials of Mulberrofuran G, Albanol B, and Kuwanon G from Root Bark of Morus alba L. in Insulin-Resistant HepG2 Cells: An In Vitro and In Silico Study. IJMS 2018; 19: 1542. [CrossRef]

- Naowaboot J, Pannangpetch P, Kukongviriyapan V, et al. Mulberry Leaf Extract Stimulates Glucose Uptake and GLUT4 Translocation in Rat Adipocytes. Am J Chin Med 2012; 40: 163–175. [CrossRef]

- Niederberger KE, Tennant DR, Bellion P. Dietary intake of phloridzin from natural occurrence in foods. Br J Nutr 2020; 123: 942–950. [CrossRef]

- Gali CC, Palle L. GlublocTM Reduces Postprandial Blood Glucose Surge in Healthy Individuals (A Placebo Controlled Pilot study). Preprint, In Review. Epub ahead of print 12 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed M, Zagury RL, Bhaskaran K, et al. A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Study to Evaluate Postprandial Glucometabolic Effects of Mulberry Leaf Extract, Vitamin D, Chromium, and Fiber in People with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Ther 2023; 14: 749–766. [CrossRef]

- Okada J, Yamada E, Okada K, et al. Comparing the efficacy of apple peels and a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (ipragliflozin) on interstitial glucose levels: A pilot case study. Current Therapeutic Research 2020; 93: 100597. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi M, Mineshita Y, Yamagami J, et al. Effects of the timing of acute mulberry leaf extract intake on postprandial glucose metabolism in healthy adults: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2023; 77: 468–473. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Yang Y, Dong W, et al. Investigation on the Enzymatic Profile of Mulberry Alkaloids by Enzymatic Study and Molecular Docking. Molecules 2019; 24: 1776. [CrossRef]

- Thondre PS, Lightowler H, Ahlstrom L, et al. Mulberry leaf extract improves glycaemic response and insulaemic response to sucrose in healthy subjects: results of a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2021; 18: 41. [CrossRef]

- Blaschek W. Natural Products as Lead Compounds for Sodium Glucose Cotransporter (SGLT) Inhibitors. Planta Med 2017; 83: 985–993. [CrossRef]

- Kahn BB, Flier JS. Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2000; 106: 473–481.

- Velasquez-Mieyer PA, Cowan PA, Arheart KL, et al. Suppression of insulin secretion is associated with weight loss and altered macronutrient intake and preference in a subset of obese adults. Int J Obes 2003; 27: 219–226. [CrossRef]

- Yu CHJ, Migicovsky Z, Song J, et al. (Poly)phenols of apples contribute to in vitro antidiabetic properties: Assessment of Canada’s Apple Biodiversity Collection. Plants People Planet 2023; 5: 225–240. [CrossRef]

- Rasouli H, Hosseini-Ghazvini SM-B, Adibi H, et al. Differential α-amylase/α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of plant-derived phenolic compounds: a virtual screening perspective for the treatment of obesity and diabetes. Food Funct 2017; 8: 1942–1954. [CrossRef]

- Niu S-L, Tong Z-F, Zhang Y, et al. Novel Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B Inhibitor-Geranylated Flavonoid from Mulberry Leaves Ameliorates Insulin Resistance. J Agric Food Chem 2020; 68: 8223–8231. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).