Submitted:

31 December 2023

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

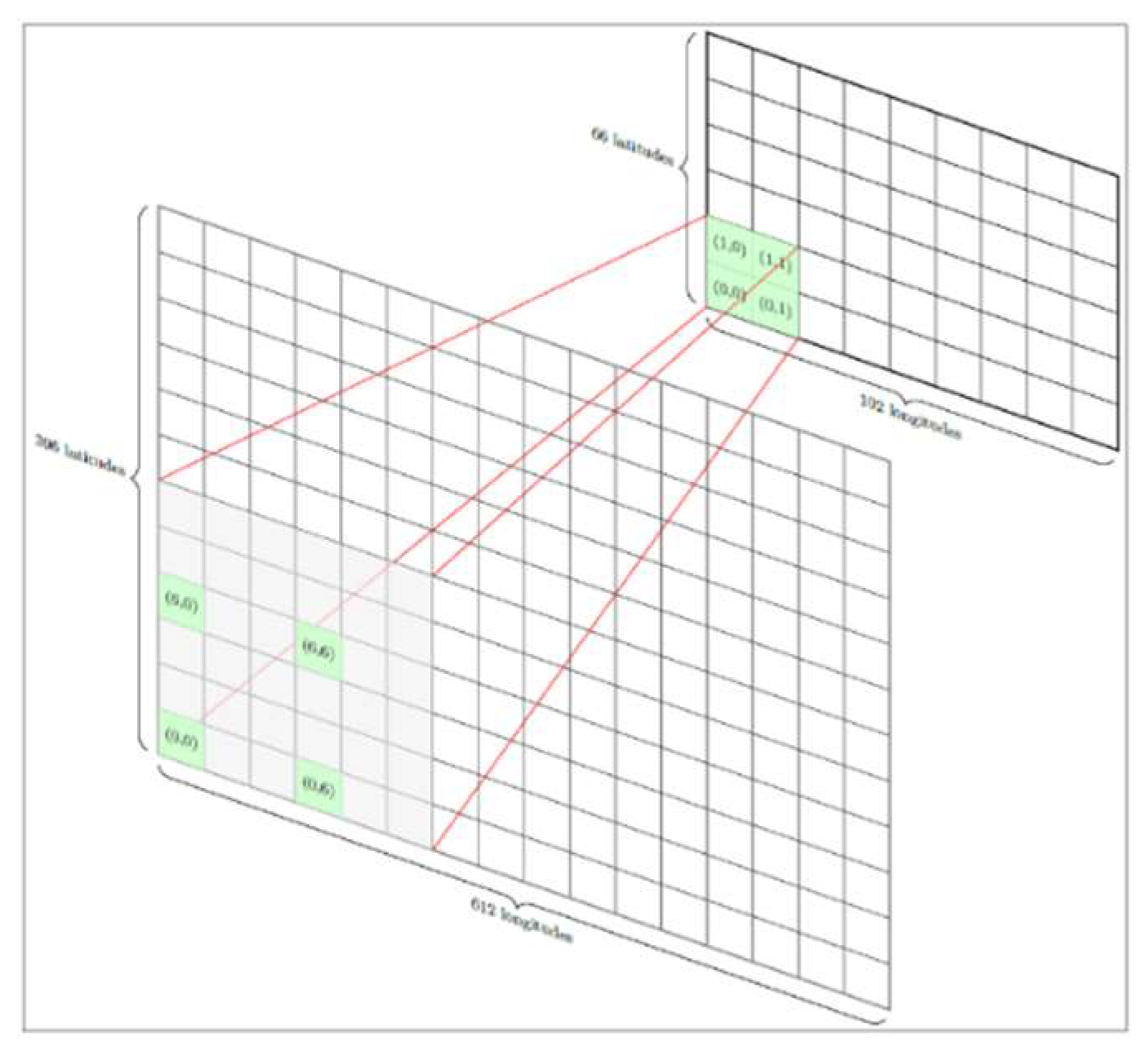

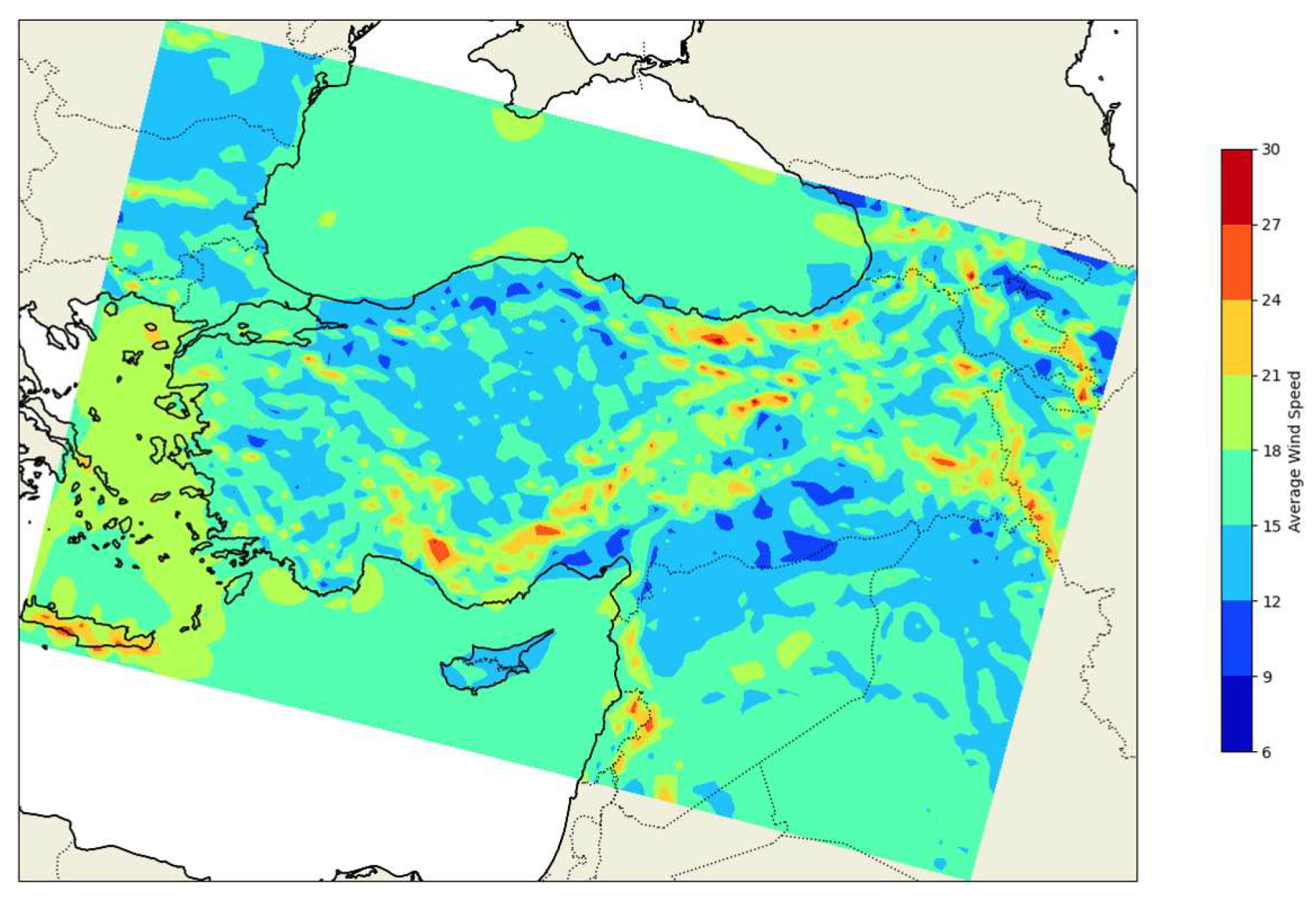

2.1.1. Wind Speed Data

2.1.2. Upper-Level Data

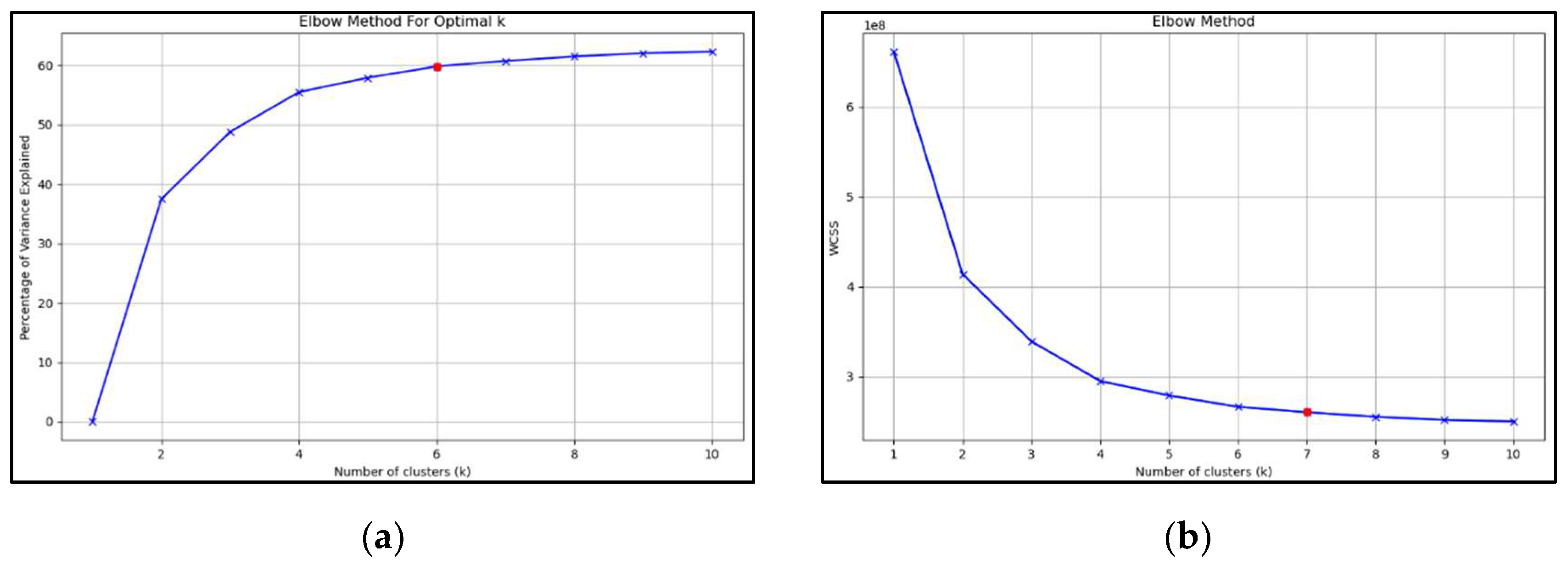

2.2. Cluster Analysis

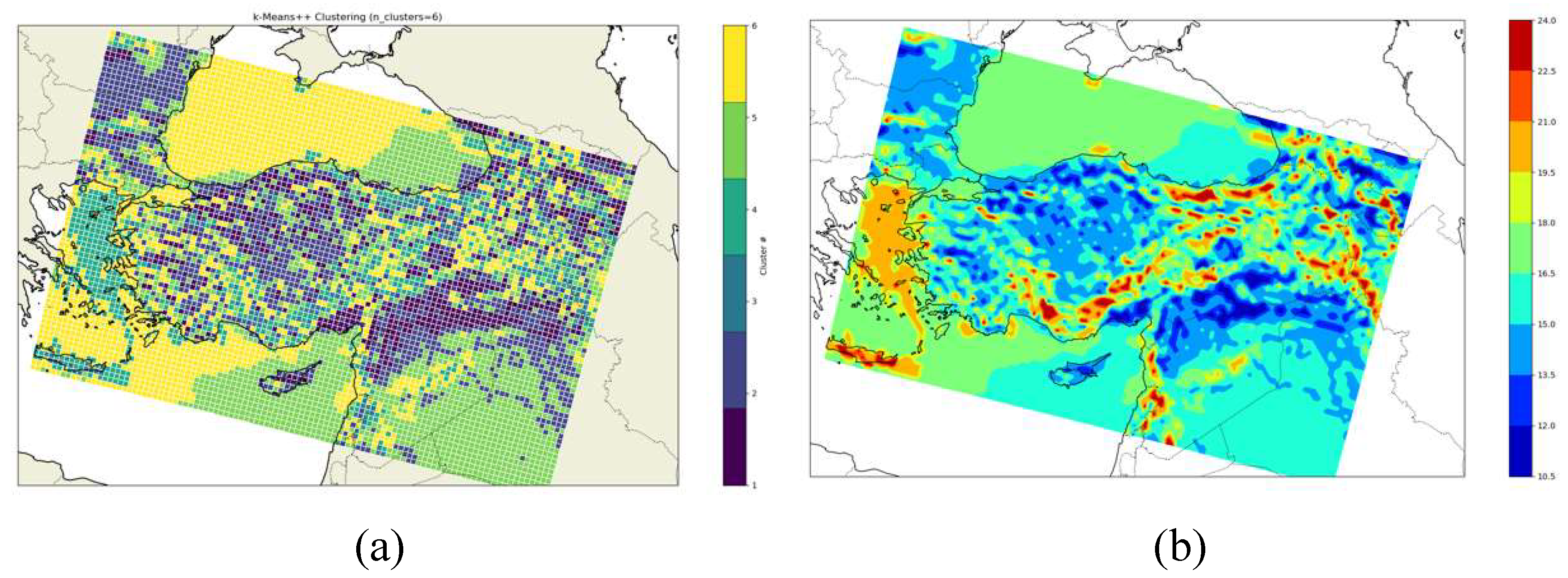

2.2.1. Clustering Extreme Wind Regimes

- The process of initializing centroids involves selecting k initial centroids from the data, which can be done randomly or by utilizing a more sophisticated initialization technique like k-means++. K-means++ is an enhanced initialization approach for k-means clustering [42] that aims to select more representative beginning cluster centroids, leading to faster convergence and improved clustering outcomes. The method sequentially determines the next centroid by selecting the data point that has the highest distance from the current centroids. By adopting this approach, the initial centroids are dispersed, thereby decreasing the probability of getting caught in local optima.

- For each data point, calculate its distance to all centroids, and assign the data points to the nearest centroid,

- Recompute the centroid of each cluster as the mean of the data points assigned to that cluster,

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until the centroids converge, so that positions do not change significantly between iterations. The K-means algorithm seeks to minimize the objective function, which is the sum of squared distances between each data point and its nearest centroid. The goal of the algorithm is to minimize the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS),

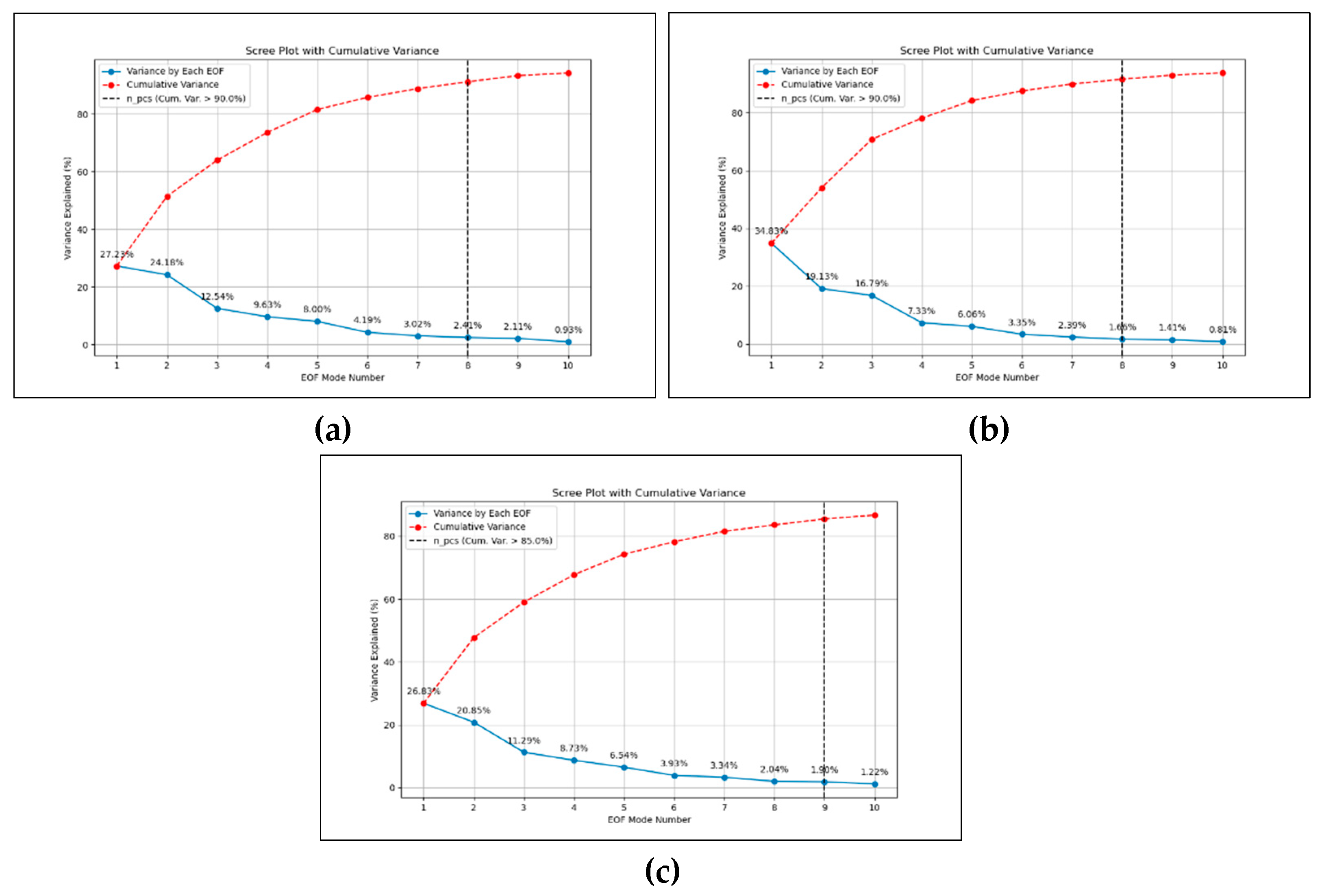

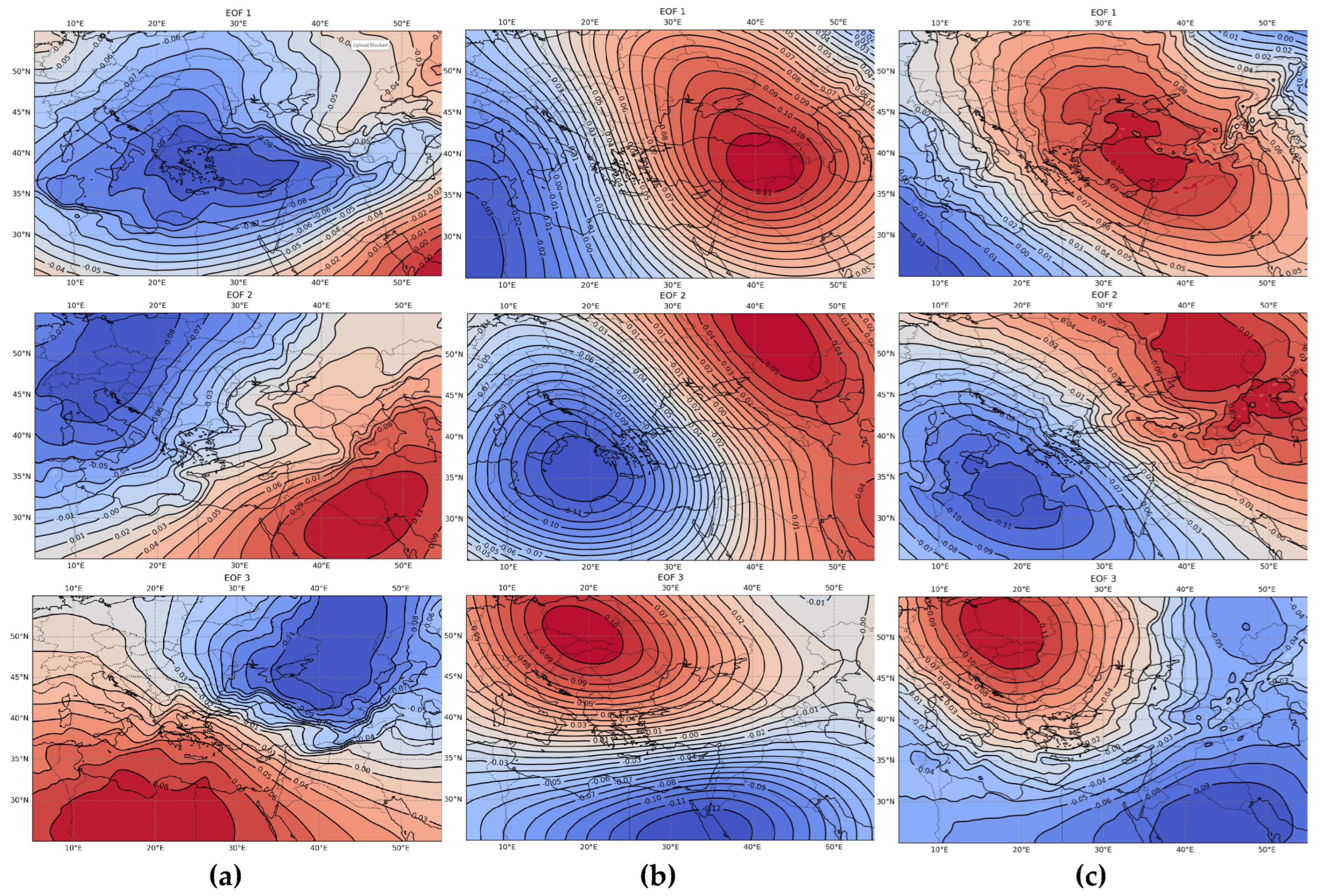

2.2.2. Upper-Level Clustering

3. Results

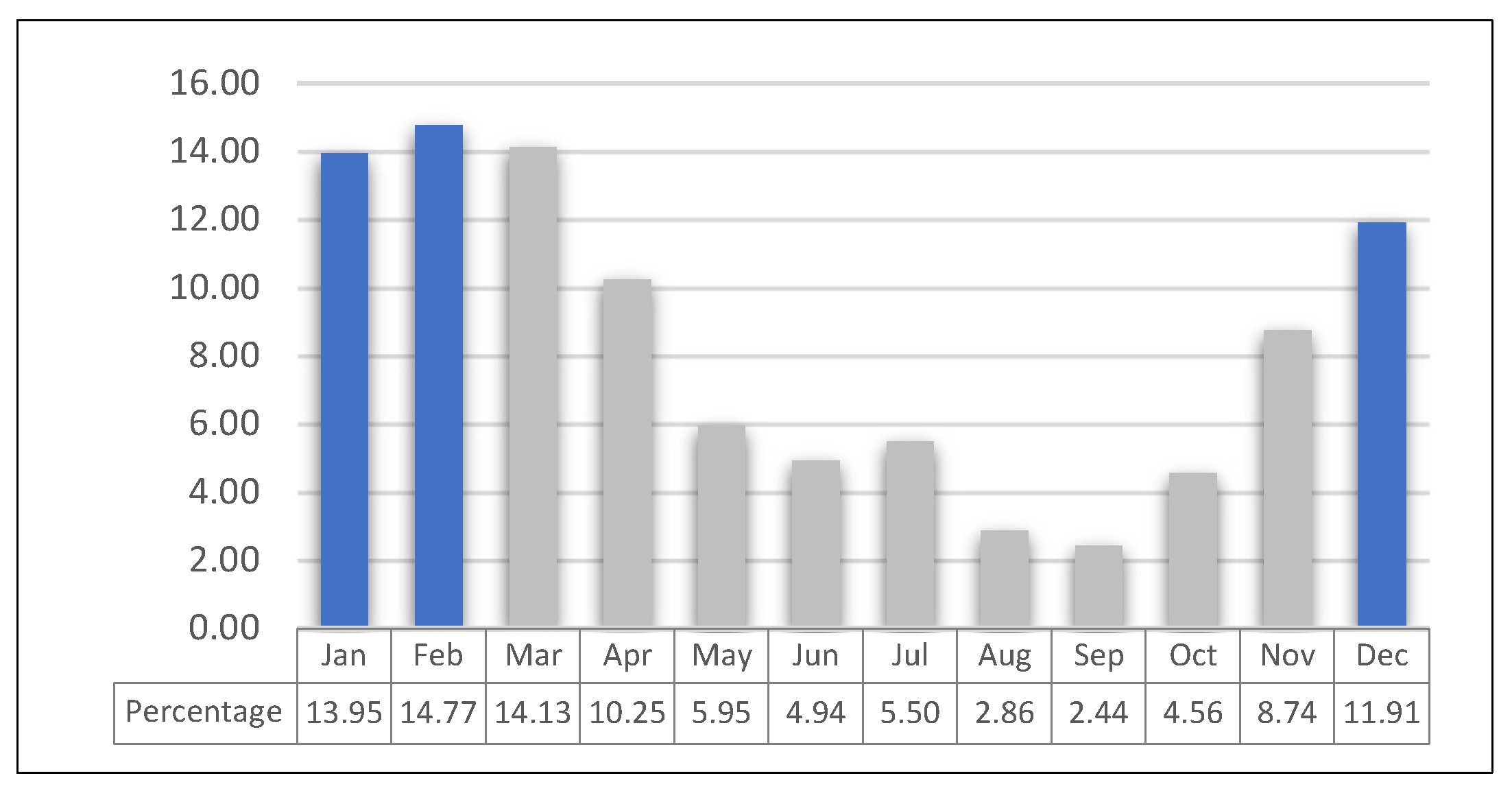

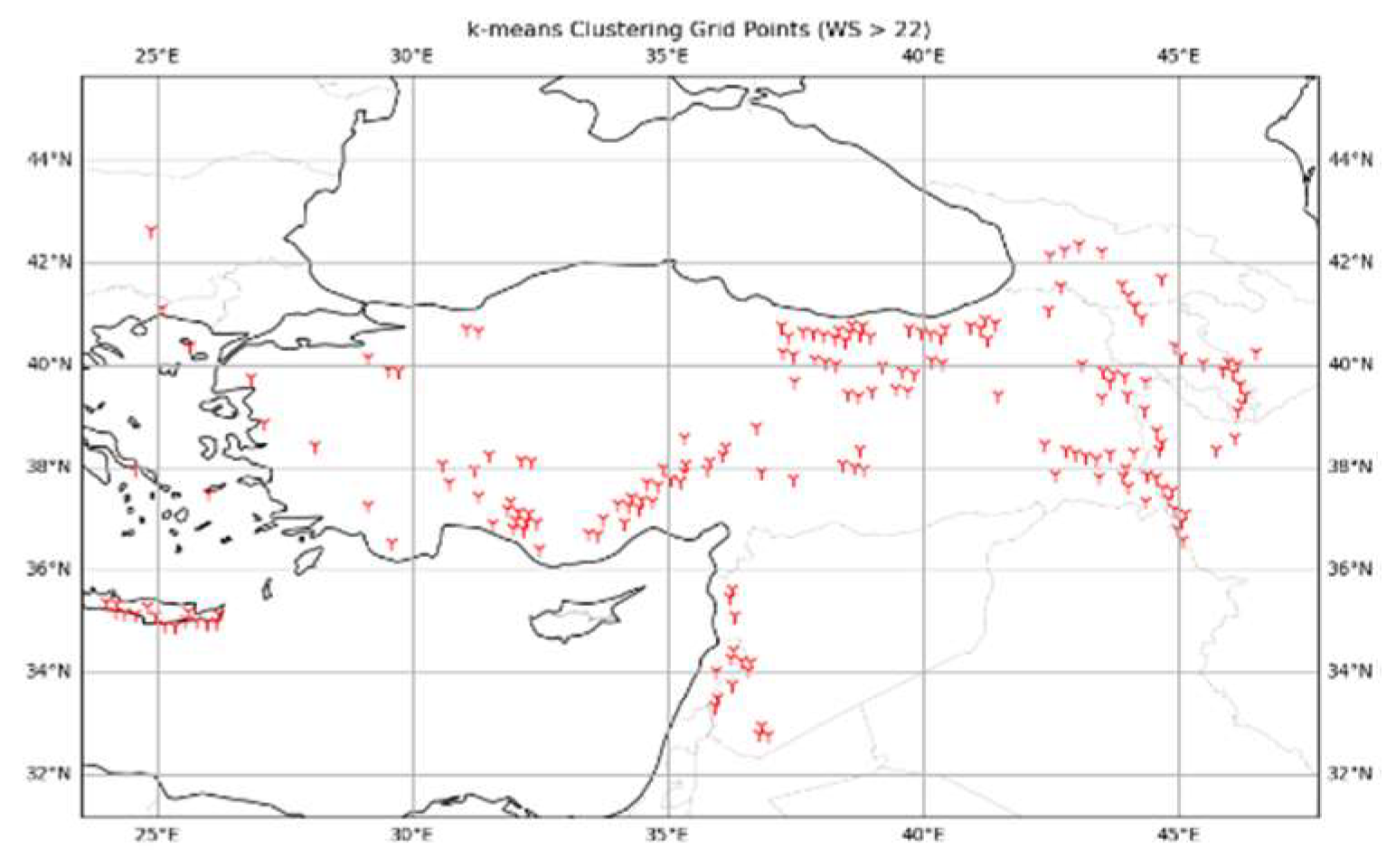

3.1. Extreme Wind Regimes over Turkey

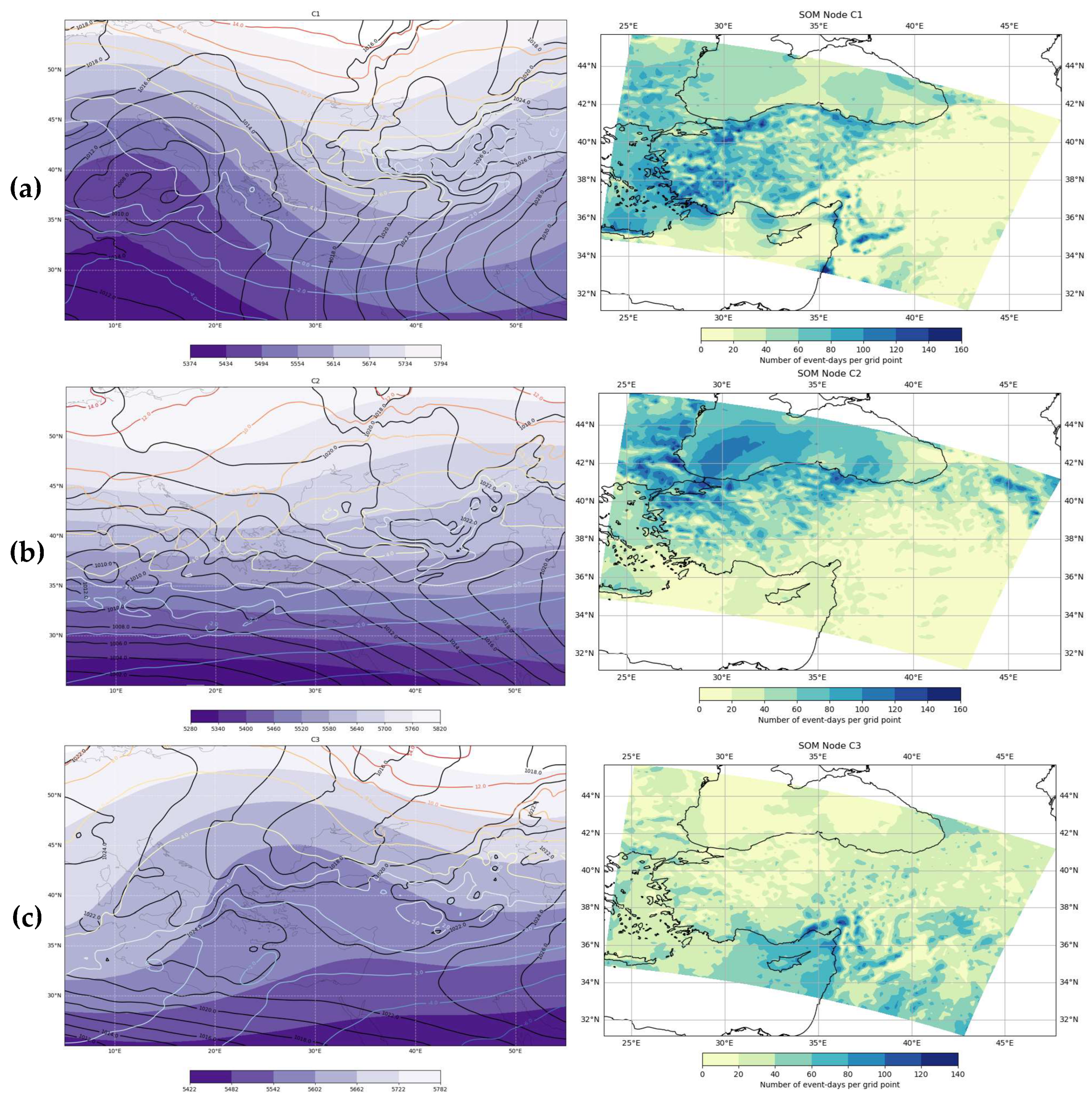

- SOM Node (C1): SOM node C1 (Figure 8a) indicates the low-pressure area in southern part of Italy and northern Africa. This low-pressure area is affecting the western region of Turkey, while a thermal-forming high-pressure system above central Georgia, such as the Siberian Highland, is affecting the northern region of Turkey, particularly inner Anatolia, the central and eastern Black Sea region, and the Eastern Anatolian region. These areas experience intense gradients, leading to strong winds. The Low-Pressure Area over the Mediterranean generates powerful winds to the west of Turkey, with the central region of high pressure originating from colder air masses. The combination of these systems results in strong winds on some days.

- SOM Node (C2): Similar to the C1 pattern, Africa experiences a region of low atmospheric pressure, whereas the northeast of Turkey has an area of high atmospheric pressure. Furthermore, an area of high atmospheric pressure is detected in the eastern region of the Caspian Sea, while a region of low atmospheric pressure is discovered in the northwest. Additionally, there is another high-pressure area in northern Central Europe. As a result of the impact of these pressure fields, Turkey experiences a significant pressure gradient effect. When examining the broader GPH area, there is a more pronounced variation in the southern parts. The presence of steep gradients contributes significantly to the occurrence of frequent and intense windy conditions in the western parts of Turkey, spanning from the northwest to the southwest. No direct effect can be identified for isotherm areas (Figure 8b).

- SOM Node (C3): This pattern mainly focuses on the northeastern region of Europe, where a cyclone is impacting the Black Sea and extending its influence across Turkey. Additionally, an anti-cyclone is exerting its impacts on Greece and the Mediterranean. The occurrence of winds on the Thrace can be attributed to the presence of pressure gradient zones. When looking at the geopotential height values, the effects of the ridge area of large-scale waves can be observed. Although these patterns and the periods when extremely windy days occur can be explained for the Thrace region, they cannot be fully explained for the whole of Turkey. It is thought that it can be explained by more local scale events. (Figure 8c).

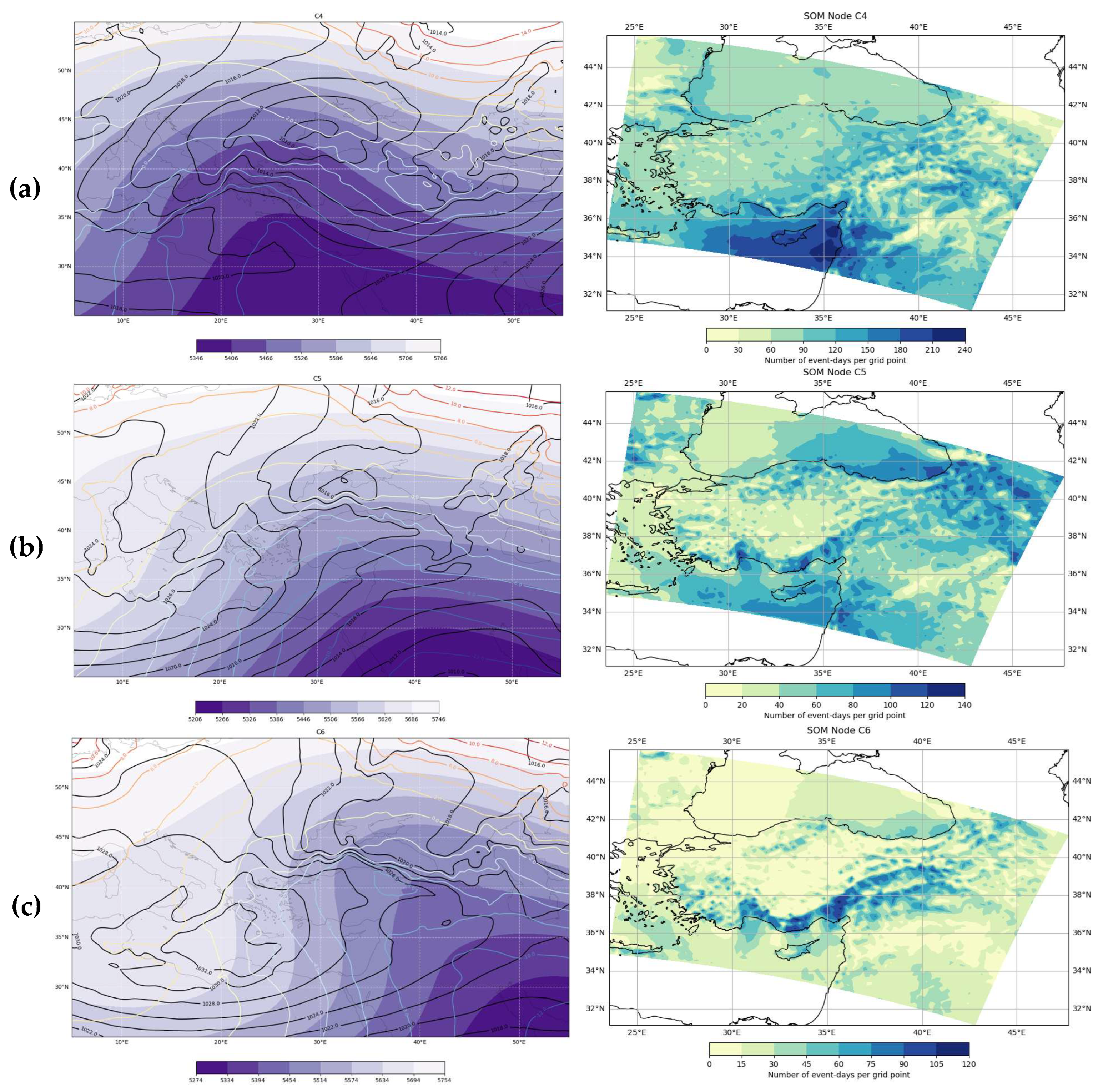

- SOM Node (C4): During the period when this pattern is effective, there is a low-pressure center located over the Black Sea, and it is observed that the high-pressure center shifts towards the west of North Africa. Additionally, there is a high-pressure area in the East. A pattern that is effective all over Turkey is observed with the influence of strong temperature gradients. This pattern, depending on the frontal activity, has an increasing effect on days with strong winds throughout Turkey. The geopotential height field does not seem to have much effect on this pattern because it represents a large-scale pattern. It can be seen here that during the winter months when high winds occur on Turkey, events on a synoptic scale rather than a broad scale have a greater impact. Strong gradients are seen in this pattern. (Figure 9a).

- SOM Node (C5): In this pattern, the southwestern parts of Turkey, Central Anatolia and the western Black Sea region are under the general influence of the anticyclone (Azores Anticyclone) over central Italy and northern Africa. The northeastern parts are under the general influence of a cyclonic area. Accordingly, a strong gradient area has been detected in both the Black Sea and Southeastern Anatolia regions, which explains the strong winds. It has been observed that events on a synoptic scale have a greater impact. In addition, it has been determined that the cyclones formed over the Black Sea and the frontal patterns that develop regarding it increase the days of strong winds in this region. (Figure 9b).

- SOM Node (C6): A pattern is observed in which the Azores high pressure area expands over the Mediterranean and reaches over Turkey. In northeastern Asia, there is a strong gradient area where a low-pressure pattern is formed. These patterns may explain the high wind days in the northeast and west. However, the high wind days in the south cannot be explained by this pattern. (Figure 9c).

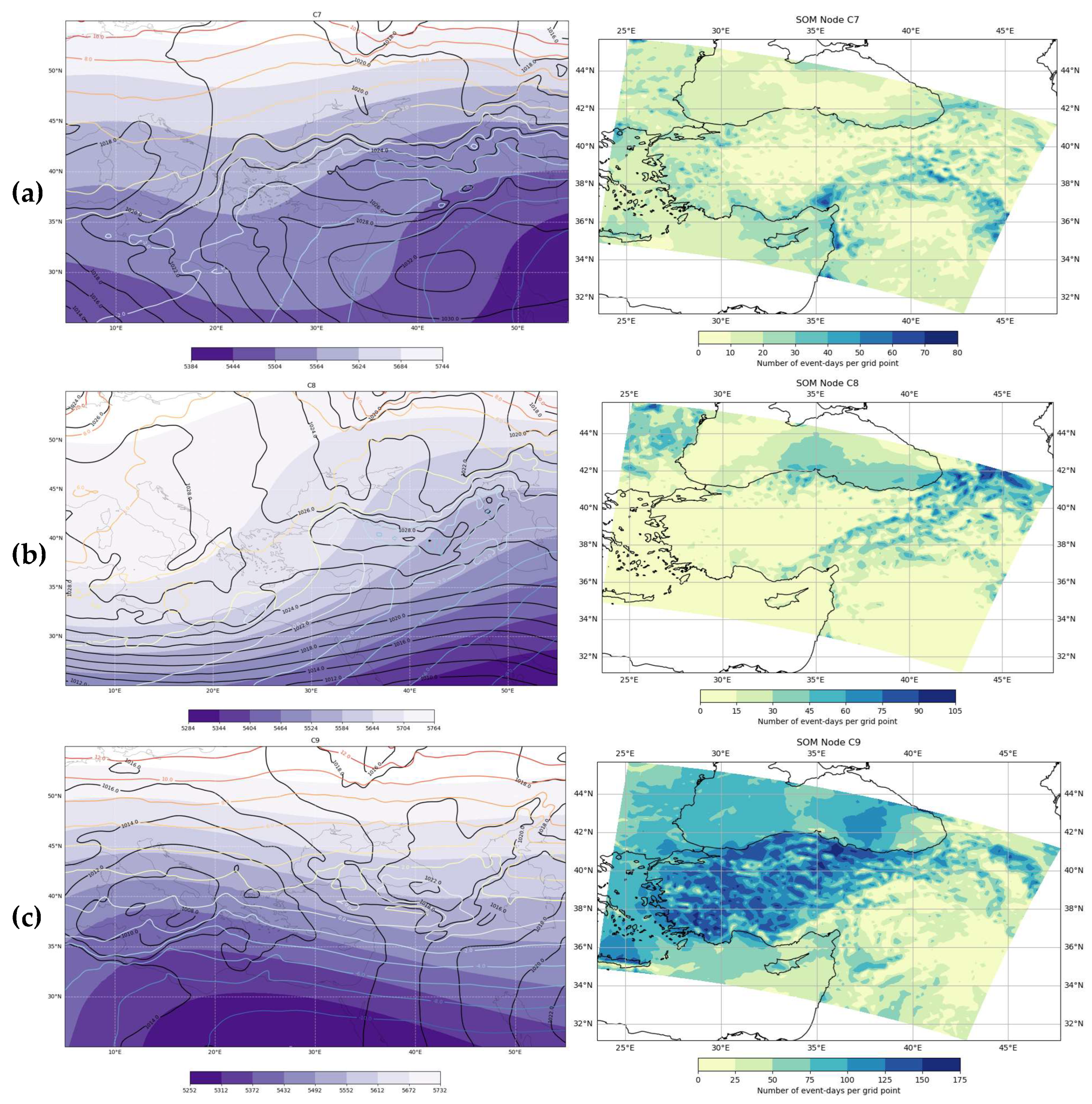

- SOM Node (C7): Due to the interaction of short and long waves on the wave pattern at the upper levels of the atmosphere, it is seen that, unlike other patterns, a short-wave trough is formed at the upper level. This trough affects the western regions through Greece. Turkey is generally under the influence of high pressure and the number of strong windy days is not high. Extremely windy days occurred off the coast of Cyprus due to the high-pressure gradient. The wave interaction that occurred over Syria at ground level appears to be more effective in this pattern. (Figure 10a).

- SOM Node (C8): In this pattern, the general effect of a high-pressure area is seen, which is effective over all of Turkey, except the Mediterranean, and whose center extends to the north-east of Central Anatolia. The temperature field created a strong gradient only over the Black Sea. There is a low-pressure area over the northeast. In this pattern, Turkey is under the influence of a low-pressure area whose center is over northeastern Europe and expanding over the Black Sea, and a high-pressure area

- SOM Node (C9): In this pattern, there is a low-pressure area centered on the western and central Mediterranean and affecting the western and southwestern regions of Turkey, and a low-pressure area in the northeast that originates over Siberia and the Caspian Sea and extends its effect to the northeastern part of Turkey. In addition to the strong gradients formed in the low-pressure area, strong gradients also formed in the isotherm areas. However, strong gradients are also observed in the geopotential height field. In this pattern, strong isobar, isotherm, and geopotential high gradients are seen together over Turkey. Thus, it characterizes very well the days with the strongest winds in Turkey. (Figure 10c).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kunz, M.; Mohr, S.; Rauthe, M.; Lux, R.; Kottmeier, C. Assessment of extreme wind speeds from regional climate models – Part 1: Estimation of return values and their evaluation. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, U.; Leckebusch, G.C.; Pinto, J.G. Extra-tropical cyclones in the present and future climate: A review. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2009, 96, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palutikof, J.P.; Brabson, B.B.; Lister, D.H.; Adcock, S.T. A review of methods to calculate extreme wind speeds. Meteorol. Appl. 1999, 6, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Richman, M.B. On the application of cluster analysis to growing season precipitation data in North America East of the Rockies. J. Climate 1995, 8, 897–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J. Big Data Mining for Climate Change. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pampuch, L. A.; Negri, R. G.; Loikith, P. C.; Bortolozo, C. A. A review on clustering methods for climatology analysis and its application over South America. Int. J. Geosci. 2023, 14, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E. N. Empirical orthogonal functions and statistical weather prediction. Scientific Rep. 1, Statistical Forecasting Project, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Defense Document Center, 1956.

- Ünal, Y.S.; Tan, E.; Menteş, Ş.S. Summer heat waves over western Turkey between 1965 and 2006. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2012, 112, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierstedt, S.E.; Hünicke, B.; Zorita, E. Variability of wind direction statistics of mean and extreme wind events over the Baltic Sea region. Tellus A: Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2015, 67, 29073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, F.L.; Horel, J.; Whiteman, C.D. Using EOF Analysis to Identify Important Surface Wind Patterns in Mountain Valleys. Journal of Applied Meteorology 2004, 43, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjami, H.; Hesari, A. R. E. Assessment of sea surface wind field pattern over the Caspian Sea using eof analysis. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 35, 101254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkeş, M.; Tatlı, H. Use of the spectral clustering to determine coherent precipitation regions in Turkey for the period 1929–2007. Int. J. Climatol. 2010, 31, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartigan, J.A.; Wong, M.A. A k-means clustering algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 1979, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaga, K.P.; Yang, M.-S. Unsupervised k-means clustering algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 80716–80727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, J. C.; Aran, M.; Cunillera, J.; Amaro, J. Atmospheric circulation patterns associated with strong wind events in Catalonia. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bernardino, A.; Iannarelli, A. M.; Casadio, S.; Pisacane, G.; Mevi, G.; Cacciani, M. Classification of synoptic and local-scale wind patterns using k-means clustering in a Tyrrhenian coastal area (Italy). Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2022, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşilbudak, M. Clustering analysis of multidimensional wind speed data using k-means approach. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Renewable Energy and Applications, Birmingham, UK, 20-23 Nov 2016; pp. 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlando, M. The synoptic-scale surface wind climate regimes of the Mediterranean Sea according to the cluster Analysis of ERA-40 wind fields. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2008, 96, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckebusch, G. C.; Weimer, A.; Pinto, J. G.; Reyers, M.; Speth, P. Extreme wind storms over Europe in present and future climate: A cluster analysis approach. Meteorol. Z. 2008, 17, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Maps; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, E.; Lynch, A.; Cassano, J.; Koslow, M. Classification of synoptic patterns in the western Arctic associated with extreme events at Barrow, Alaska, USA. Clim. Res. 2006, 30, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos, T.; Comrie, A.C.; Liverman, D.M. Intraseasonal variability associated with wet monsoons in southeast Arizona. J. Climate 2002, 15, 2477–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusch, D.B.; Alley, R.B.; Hewitson, B.C. Relative performance of self-organizing maps and principal component analysis in pattern extraction from synthetic climatological data. Polar Geogr. 2005, 29, 188–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa Raju, K.; Nagesh Kumar, D. Classification of Indian meteorological stations using cluster and fuzzy cluster analysis, and Kohonen artificial neural networks. Hydrol. Res. 2007, 38, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedairia, S.; Khadir, M.T. Self-organizing map and k-means for meteorological day type identification for the region of Annaba-Algeria. In Proceedings of the 7th Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management Applications, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 26-28 June 2008; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spassiani, A. C.; Mason, M. S. Application of self-organizing maps to classify the meteorological origin of wind gusts in Australia. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 210, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Hao, C.; Cao, J.; Lan, X.; Huang, Y. Characteristics of large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns conducive to severe spring and winter wind events over Beijing in China based on a machine learning categorizing method. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, B.-J.; Nam, H.-G.; Jeong, J.; Shim, J.-K.; Kim, K. R.; Kim, S. Classification of homogeneous regions of Strong wind and gust wind in Korea. SOLA 2020, 16, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastine, D.; Larsén, X.; Witha, B.; Dörenkämper, M.; Gottschall, J. Extreme winds in the new European wind atlas. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2018, 1102, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Angelou, N.; Arnqvist, J.; Callies, D.; Cantero, E.; Arroyo, R.C.; Courtney, M.; Cuxart, J.; Dellwik, E.; Gottschall, J.; et al. Complex terrain experiments in the new European wind atlas. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20160101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menteş, Ş.; Ünal, Y.; Ezber, Y.; Barutçu, B.; Aslan, Z.; Kirkil, G.; Topçu, S.; Erten, E.; İncecil, S.; Önol, B. Yeni Avrupa Rüzgar Atlası (NEWA) Projesi Kapsamında Türkiye Üzerine Rüzgar Enerji Kaynağının Modellenmesi. 2019 (No: 215M386) TÜBİTAK.

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), (Accessed on 26-11-2023). [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), (Accessed on 26-11-2023). [CrossRef]

- Kalnay, E.; Kanamitsu, M.; Kistler, R.; Collins, W.; Deaven, D.; Gandin, L.; Iredell, M.; Saha, S.; White, G.; Woollen, J.; et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1996, 77, 437–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, J.R.; Hakim, G.J. An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology; Academic Press, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.M.; Hobbs, P.V. Atmospheric Science; Elsevier, 2006.

- Dee, D.P.; Uppala, S.M.; Simmons, A.J.; Berrisford, P.; Poli, P.; Kobayashi, S.; Andrae, U.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Balsamo, G.; Bauer, P.; et al. The ERA-interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 553–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, J.P.; Oort, A.H. Physics of climate; American Institute of Physics: Melville, NY, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, 21 Jun 1967, 1(14); pp. 281–297.

- Arthur, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. K-means++: The advantages of careful seeding. In Proceedings of the Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 7-9 Jan 2007; pp. 1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.-L.; Yang, M.-S. Alternative C-Means Clustering Algorithms. Pattern Recognition 2002, 35, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.; Cooper, M.C. A study of standardization of variables in cluster analysis. J. Classif. 5 1988, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Murty, M.N.; Flynn., P.J. 1999. Data clustering: a review. ACM Comput. Surv. 1999, 31, 264–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Self-organized formation of topologically correct feature maps. Biol. Cybern. 1982, 43, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaski, S.; Kohonen, T. Exploratory data analysis by the self-organizing map: Structures of welfare and poverty in the world. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Neural Networks in the Capital Markets; 1996; pp. 498–507. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- Vesanto, J.; Himberg, J.; Alhoniemi, E.; Parhankangas, J. SOM Toolbox for Matlab 5, Helsinki University of Technology, Helsinki, Finland, Rep. A57. Helsinki University of Technology, Neural Networks Research Centre, Espoo, Finland 2000, No. April.

- Tatli, H.; Menteş, Ş.S. Detrended cross-correlation patterns between North Atlantic oscillation and precipitation. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2019, 138, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaski, S. Data exploration using self-organizing maps. Ph.D. Thesis, Finnish Academy of Technology, Finland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tatli, H.; Dalfes, H.N.; Menteş, Ş.S. A statistical downscaling method for monthly total precipitation over Turkey. Int. J. Climatol. 2004, 24, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Zou, M.; Cheung, H.N.; Zhou, W.; Li, Q.; Feng, G.; Dong, W. Predictability of the wintertime 500 hpa geopotential height over Ural-Siberia in the NCEP climate forecast system. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 54, 1591–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, H.E.; Smith, D.M.; Scaife, A.A.; Dunstone, N.J. Seasonal predictability of the East Atlantic pattern in late autumn and early winter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Y.; Yu, W.; Lin, H. A new statistical–dynamical downscaling procedure based on eof analysis for regional time series generation. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2013, 52, 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, P.; Jack, C.; Tadross, M.; van Aardenne, L.; Lennard, C. Interannual rainfall variability and som-based circulation classification. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 50, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Event-Day Count | 270 | 311 | 371 | 433 | 290 | 199 | 311 | 224 | 298 |

| Mean Event-Day Percentage | 8.29% | 6.76% | 4.44% | 10.11% | 12.37% | 10.33% | 2.33% | 5.41% | 15.47% |

| Mean Wind Speed | 22.81 | 21.82 | 22.65 | 22.54 | 22.53 | 23.72 | 22.38 | 22.64 | 22.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).