Submitted:

29 December 2023

Posted:

30 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Analytics

2.1. Substance Systems Used

2.2. Analytics

2.2.1. Concentration Analysis

2.2.2. Video Analysis of Slug Length and Particle Suspension

2.2.3. Offline PSD Analysis

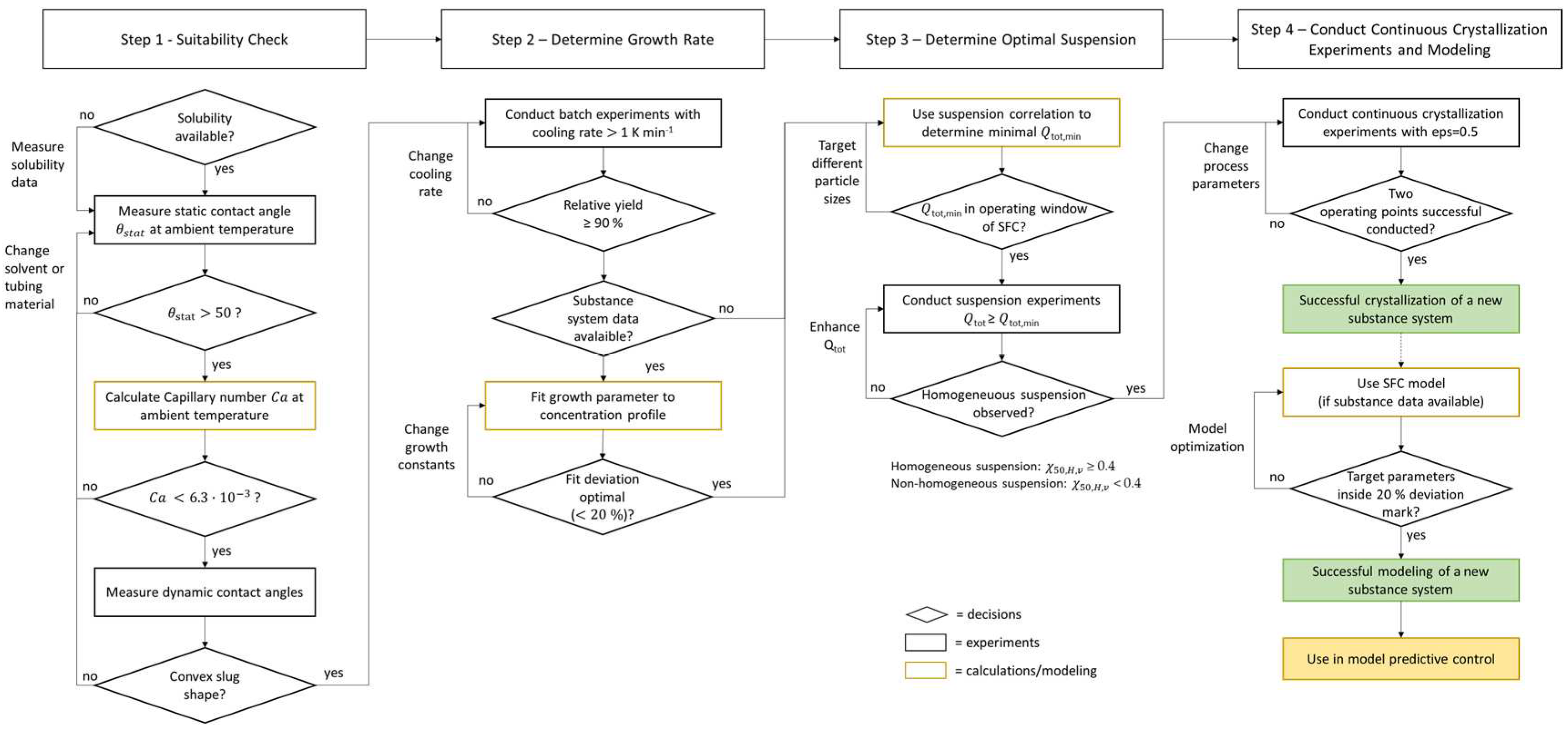

3. Strategy and Experimental Procedures

3.1. Strategy for Transferring the Experimental and Model-Based Approach to Crystallization of Different Substance Systems Inside the Slug Flow Crystallizer

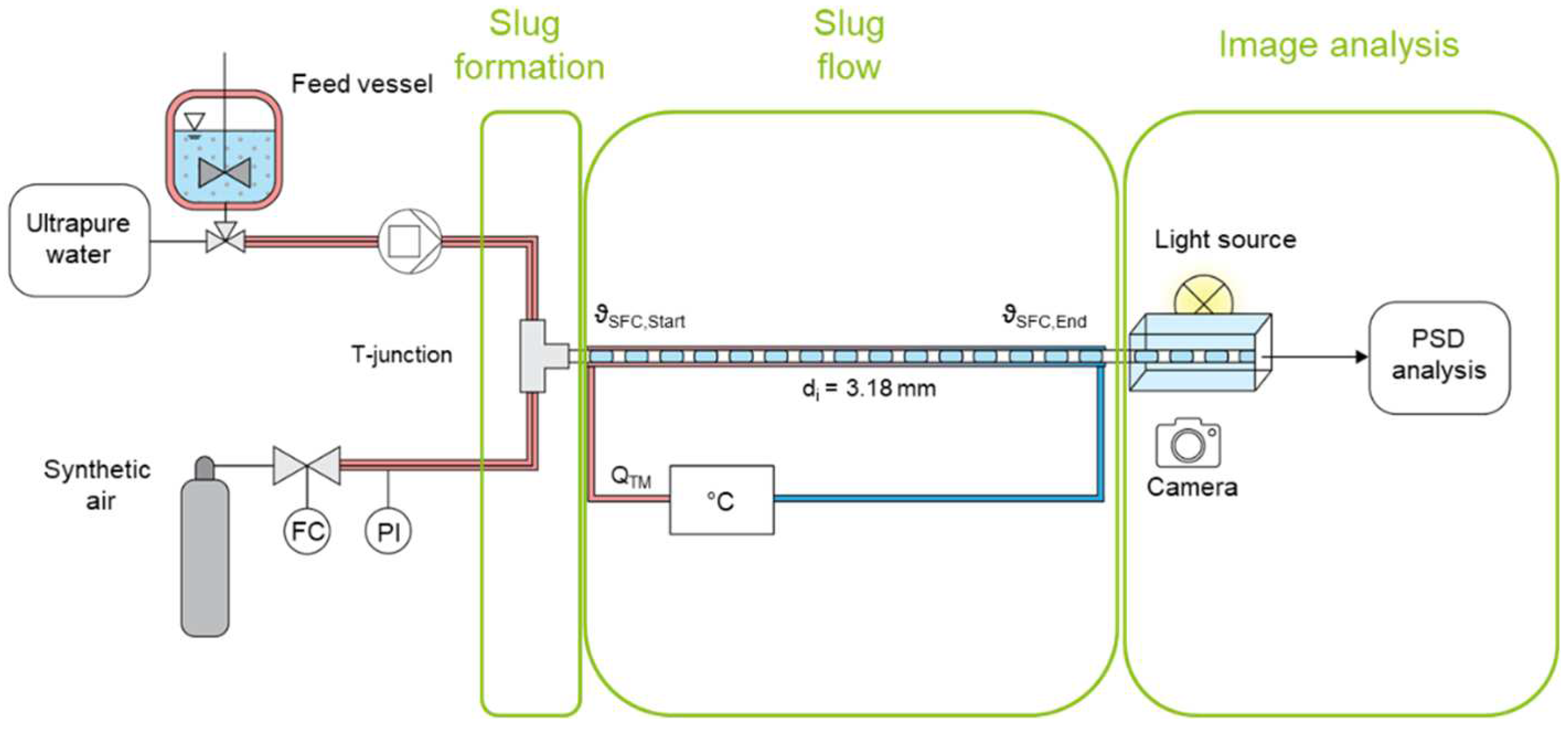

3.2. Setups and Procedures

3.2.1. Batch Crystallization Experiments

3.2.2. Continuous Slug Flow Experiments

4. Results and Discussion

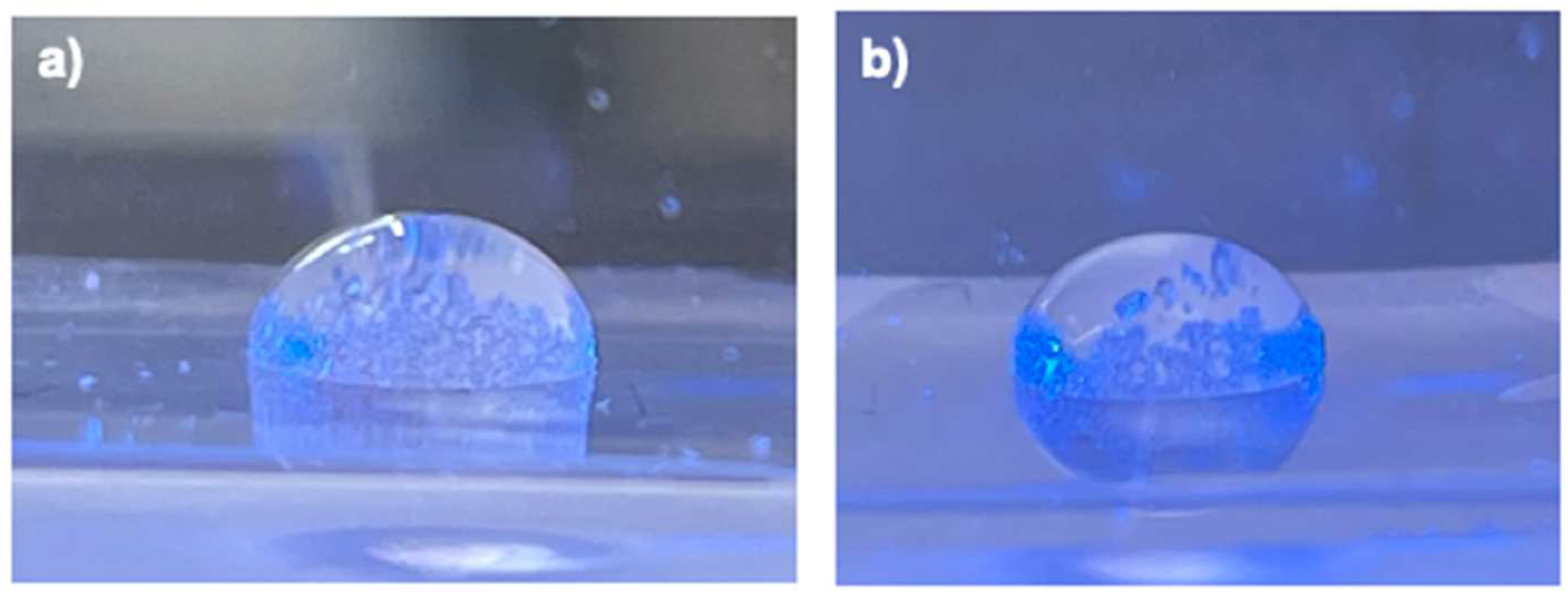

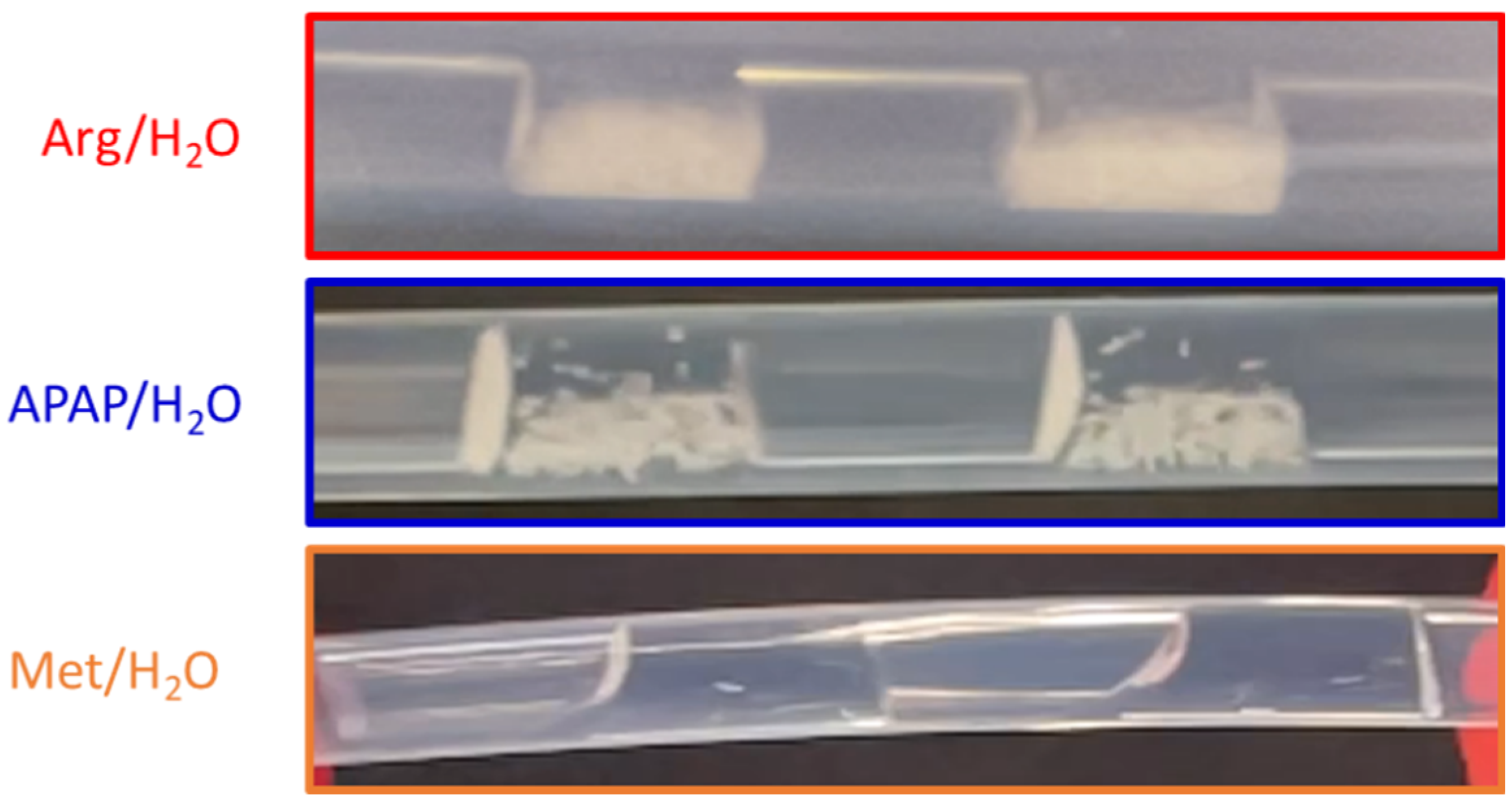

4.1. Results of Step 1 – Suitability Check

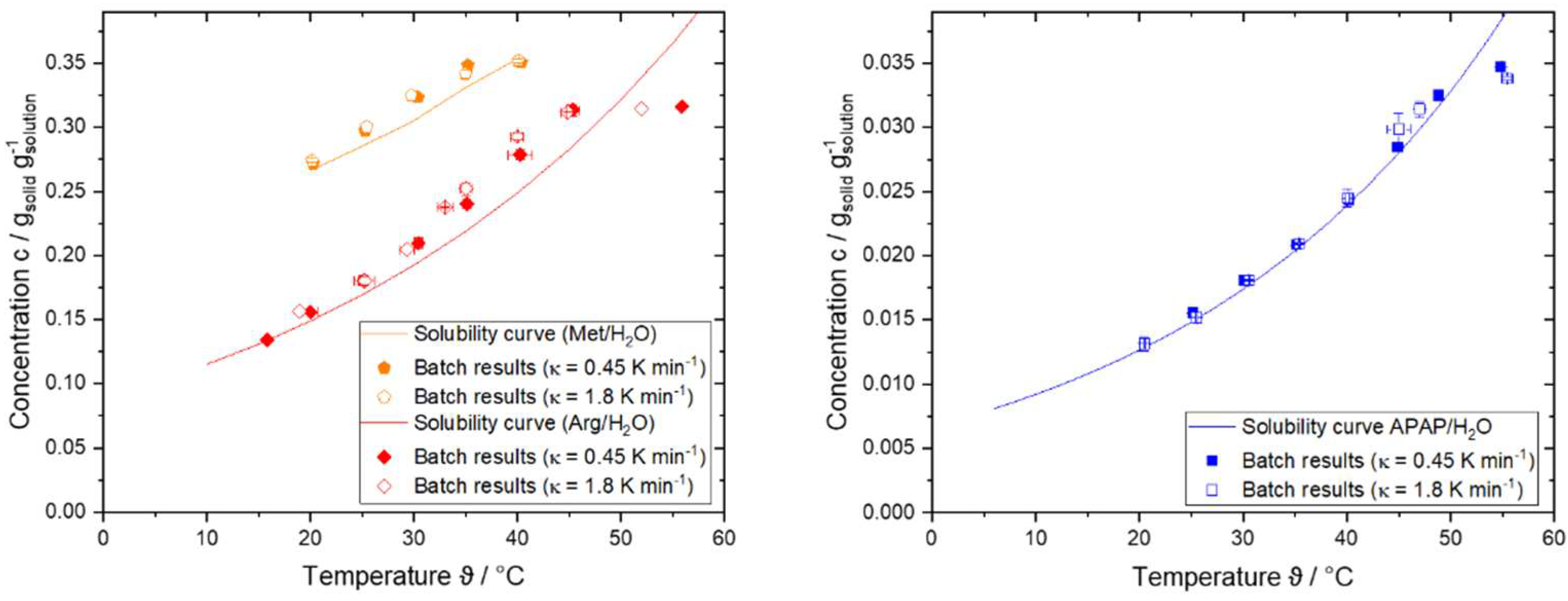

4.2. Results of Step 2 – Determine Growth Behavior

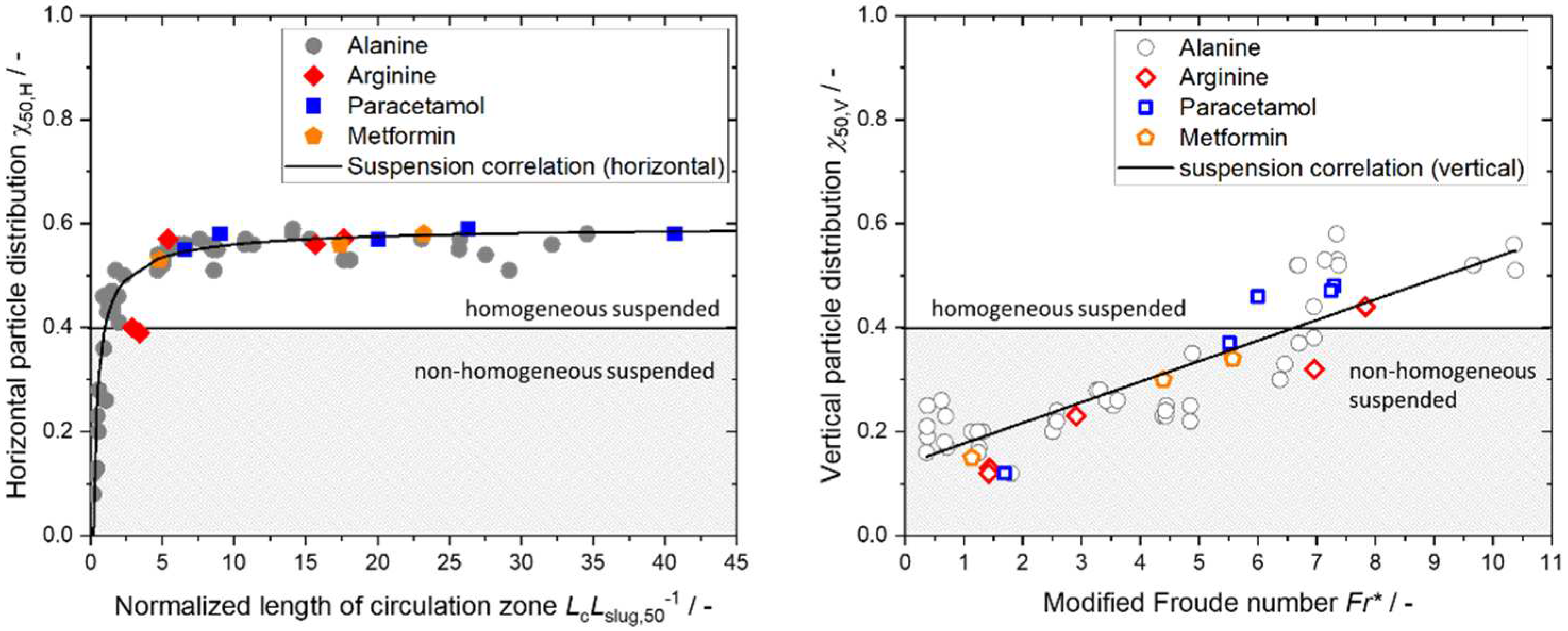

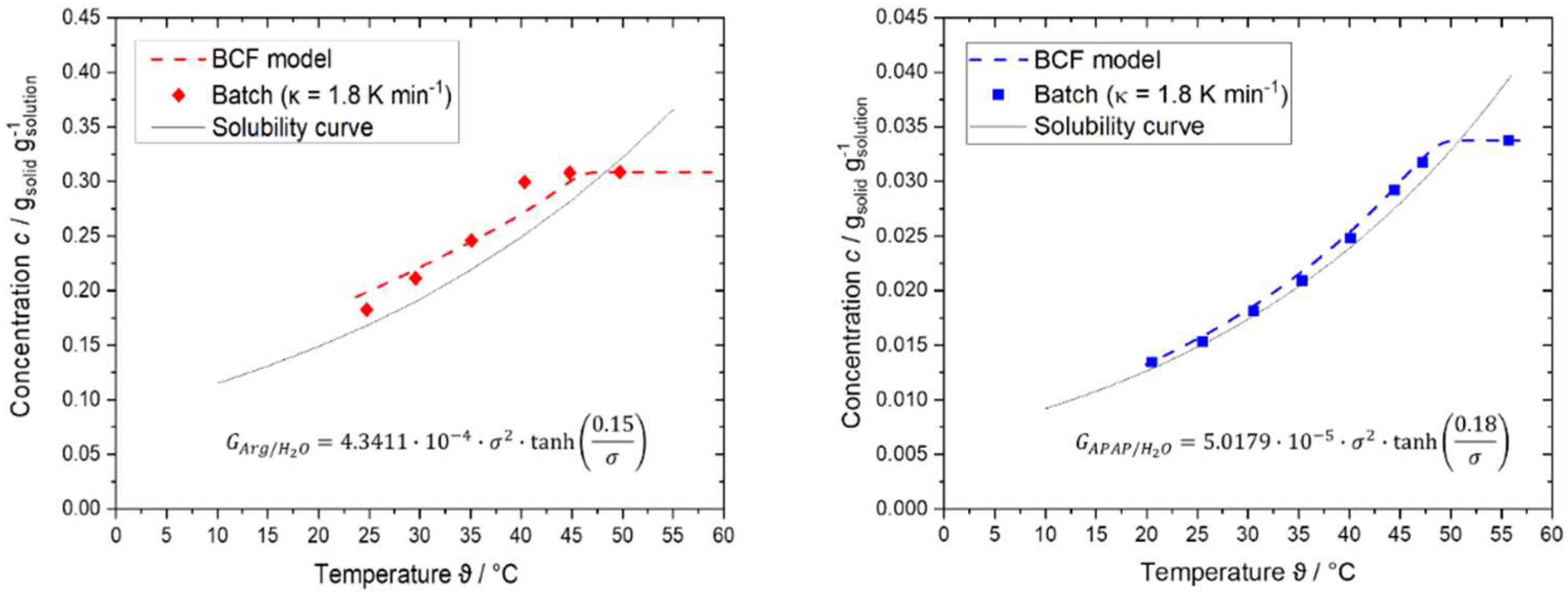

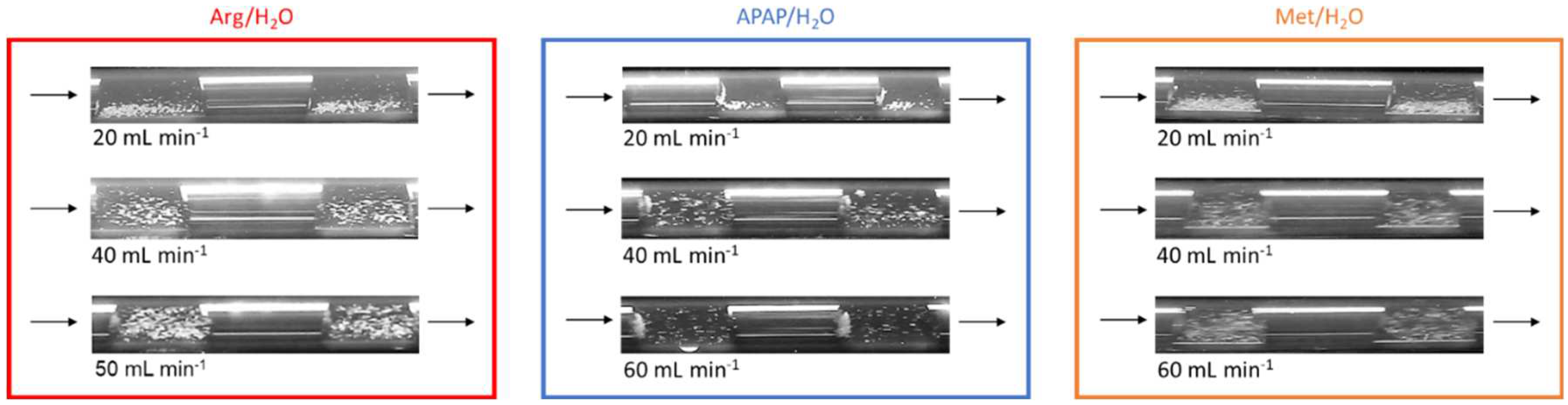

4.3. Results of Step 3 – Determine Optimal Suspension

|

/ mL min-1 |

/ - |

/- |

/ - |

/- |

/ - |

/- |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arg/H2O | 20 | 2.90 | 1.42 | 0.50 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.12 |

| 20 | 3.41 | 1.43 | 0.51 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.13 | |

| 30 | 5.41 | 2.91 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.23 | |

| 40 | 17.64 | 6.96 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.32 | |

| 50 | 15.66 | 7.83 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.44 | |

| APAP/H2O | 20 | 6.57 | 1.69 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.12 |

| 40 | 9.03 | 5.52 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.37 | |

| 40 | 20.06 | 6.00 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.57 | 0.46 | |

| 60 | 40.71 | 7.30 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.48 | |

| 60 | 26.30 | 7.24 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.47 | |

| Met/H2O | 20 | 4.81 | 1.13 | 0.53 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.15 |

| 40 | 23.20 | 4.39 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.58 | 0.30 | |

| 60 | 17.38 | 5.57 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.34 |

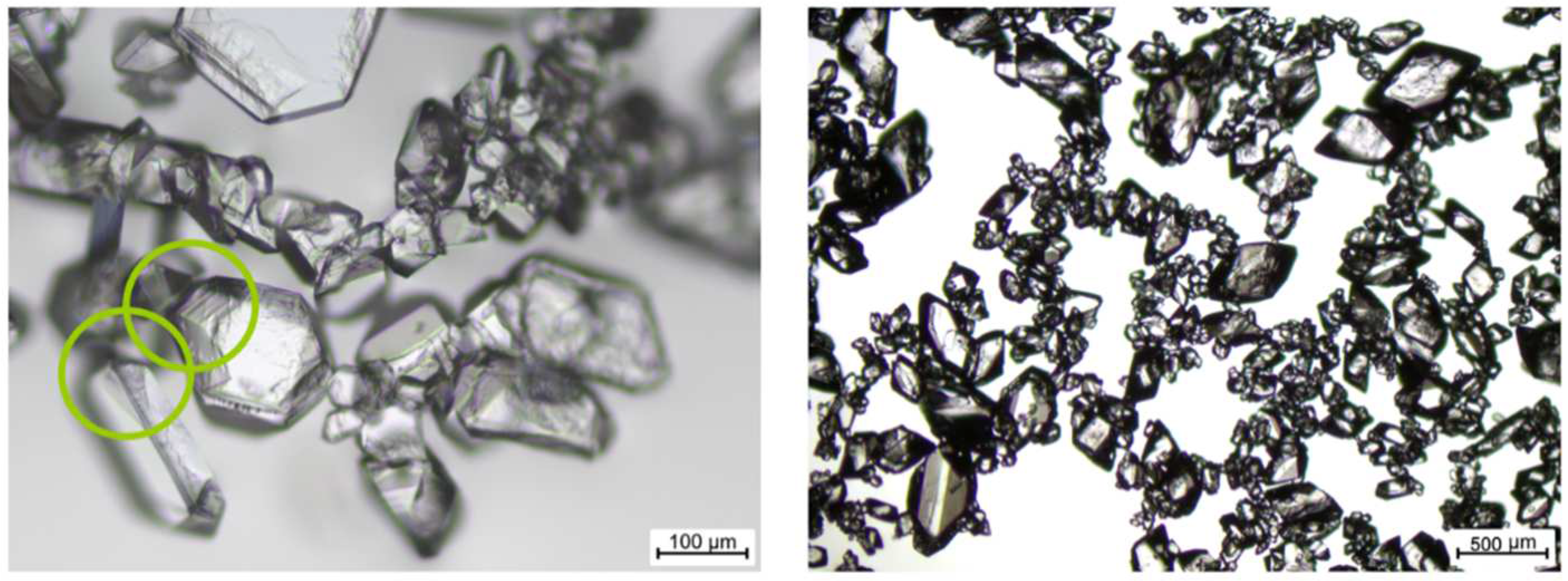

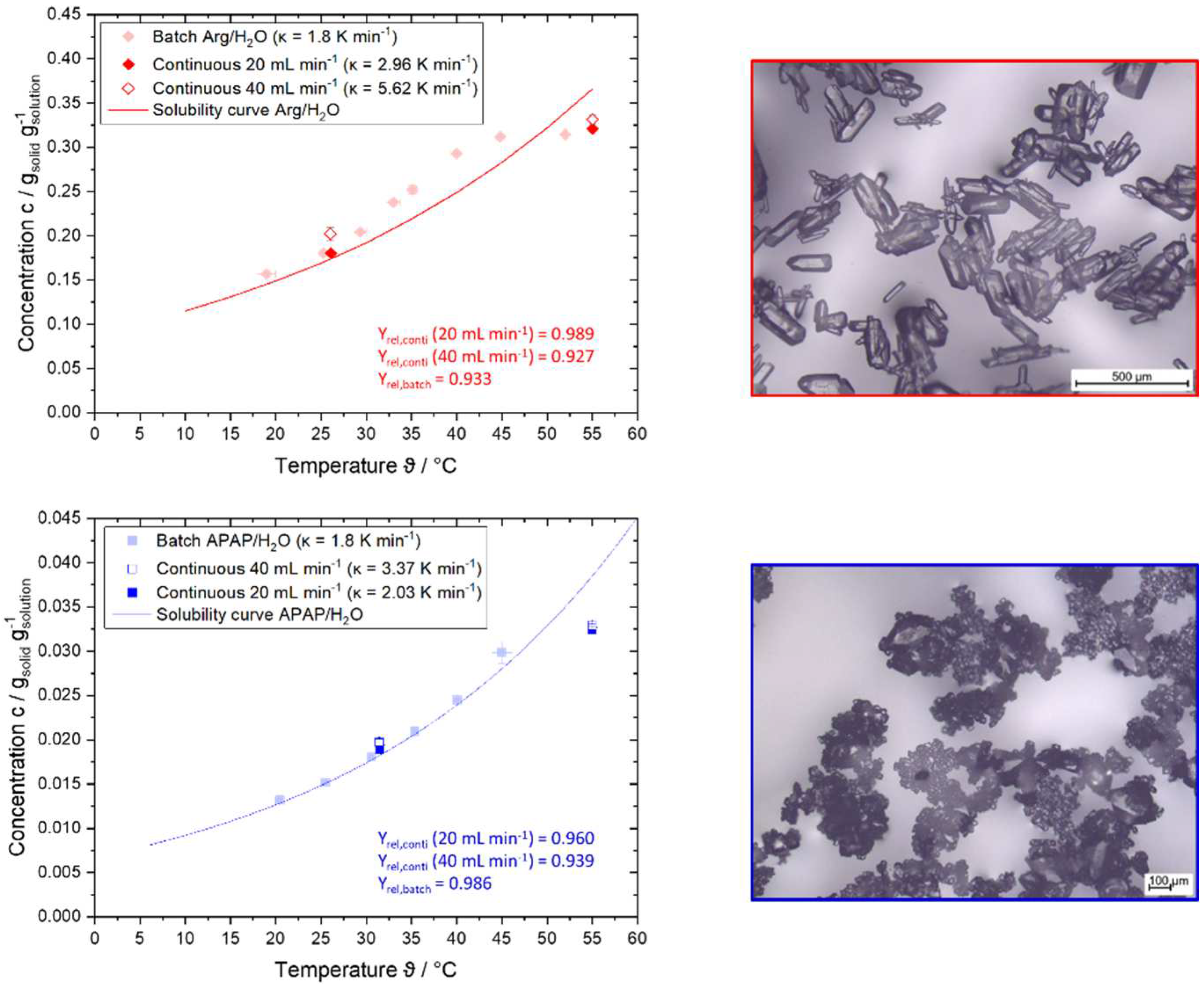

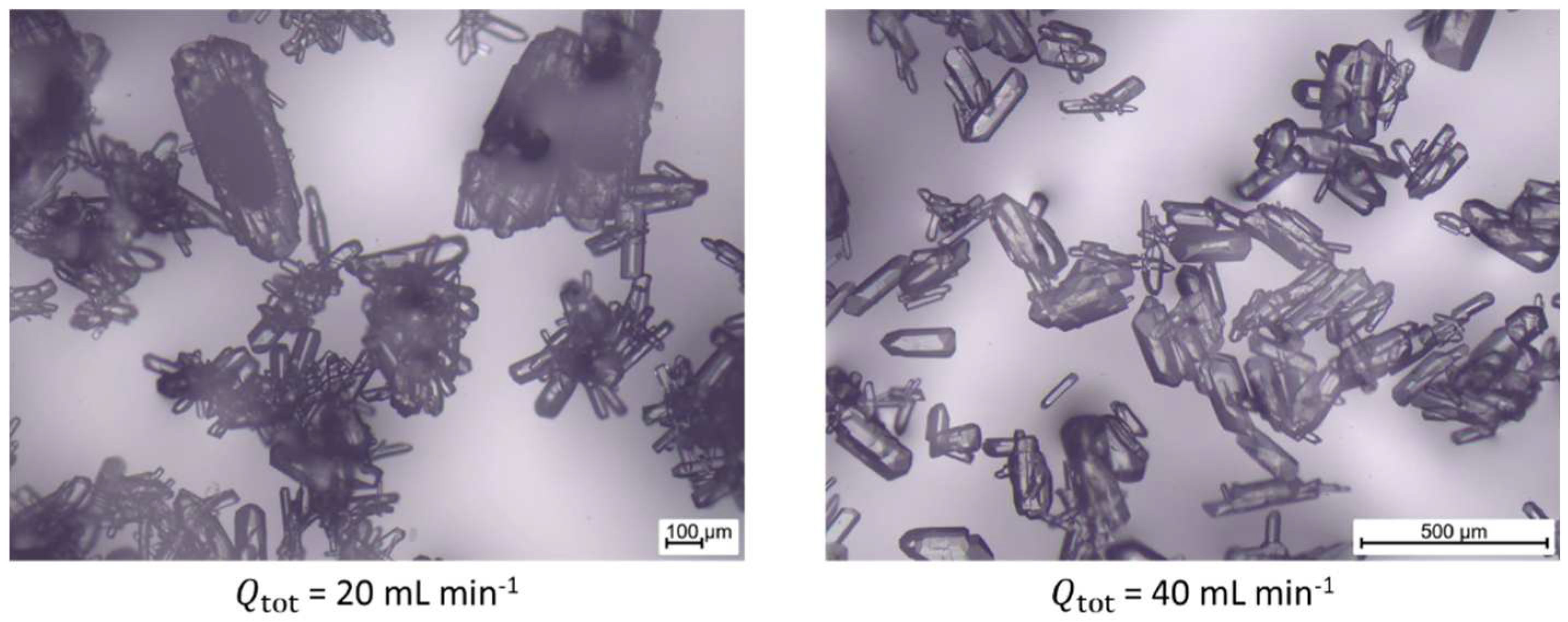

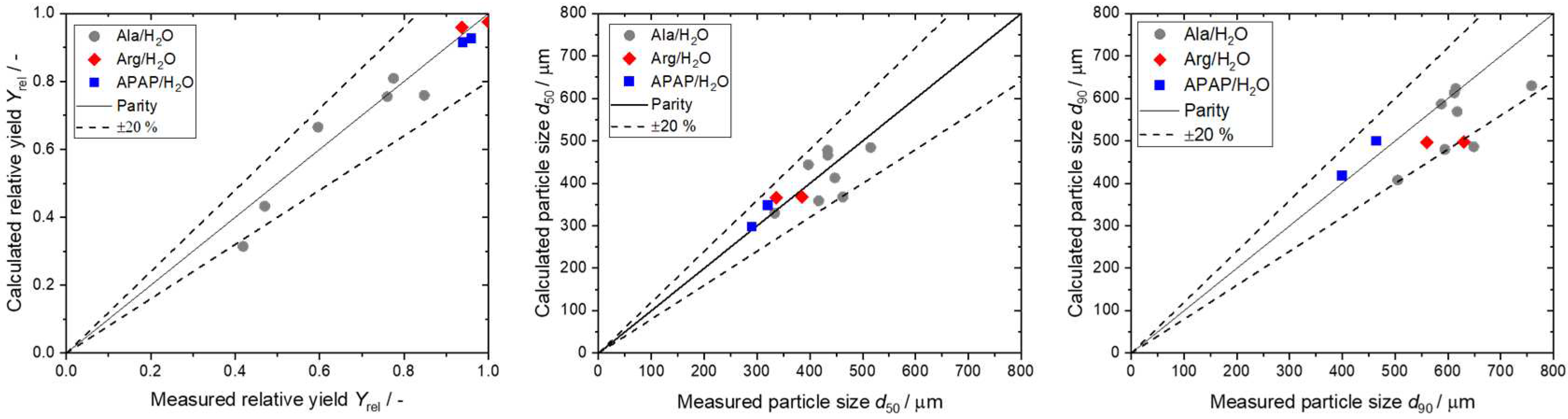

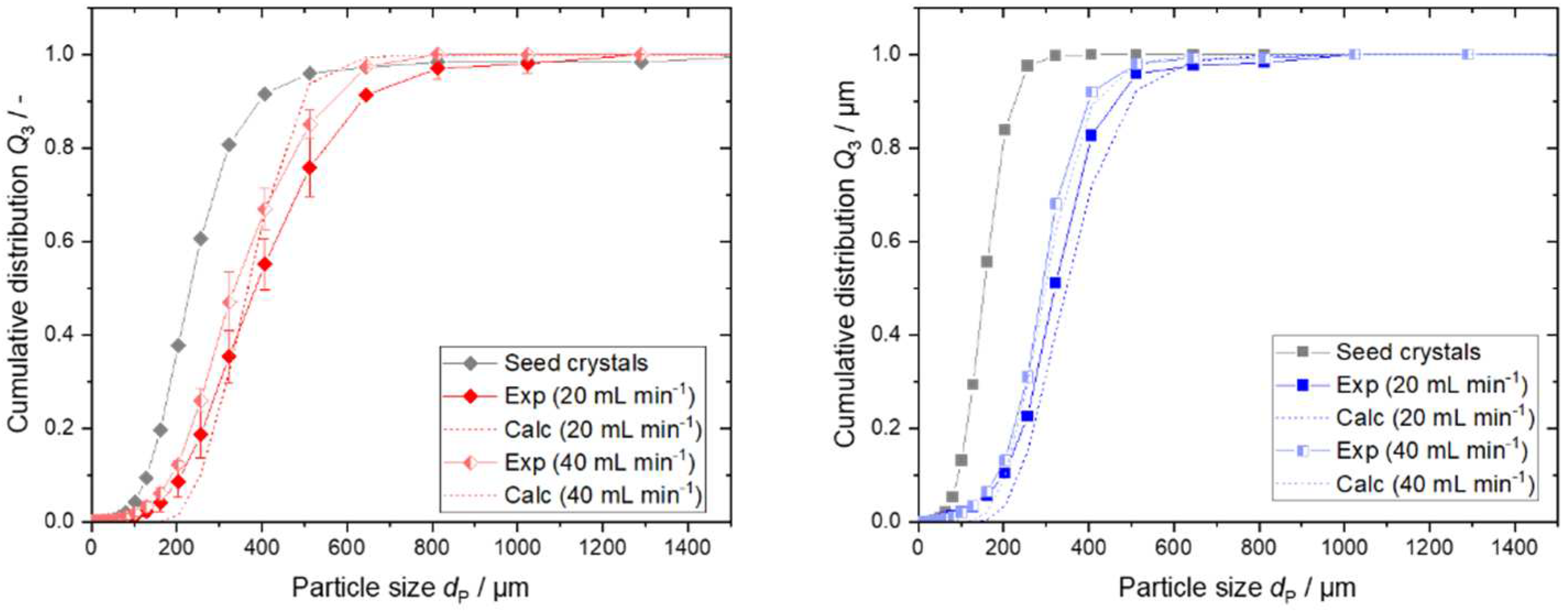

4.3. Results of Step 4 - Conduct Continuous Crystallization Experiments and Modeling

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| Abbreviations | |

| Ala | l-Alanine |

| ALD | Axis length distribution |

| APAP | Acetaminophen/paracetamol |

| API | Active pharmaceutical ingredient |

| Arg | l-Arginine |

| FEP | Fluorinated-ethylene-propylene |

| H2O | Water |

| MAL | Major axis length |

| MALch | Characteristic major axis length |

| Met | Metformin hydrochloride |

| MIL | Minor axis length |

| MILch | Characteristic minor axis length |

| PSD | Particle size distribution |

| RTD | Residence time distribution |

| SFC | Slug flow crystallizer |

| SLD | Slug length distribution |

| STY | Space-time yield |

| Latin Symbols | |

| A | Factor in growth rate equation/m s-1 |

| B | Factor in growth rate eqaution/- |

| Concentration/g g−1 | |

| Saturation concentration/g g−1 | |

| Ca | Capillary number/- |

| d | Diameter/m |

| Modified Froude number | |

| G | Growth rate/m s-1 |

| L | Characteristic length/m |

| Normalized length of circulation zone/- | |

| m | Mass/kg |

| n | Stirrer speed/rpm |

| Q | Volume flow rate/mL min−1 |

| Q3 | Cumulative distribution function/- |

| S | Supersaturation level/- |

| V | Volume/m-3 |

| w | Mass fraction/- |

| Y | Yield/% |

| Greek Symbols | |

| ε | Liquid hold-up/- |

| Three-phase contact angle/° | |

| Temperature/°C | |

| Cooling rate/K min-1 | |

| Residence time/s | |

| Relative supersaturation/- | |

| χ | Goodness of suspension/- |

| Indices | |

| 0 | Initial state |

| 10 | 10 % of the distribution |

| 50 | Median |

| 90 | 90 % of the distribution |

| 90-10 | Width of distribution |

| Saturation | |

| Ala | l-alanine |

| amb | Ambient temperature |

| Arg | l-arginine |

| BCF | Burton, Cabrera and Frank |

| BCF,mod | Modified Burton, Cabrera and Frank |

| dry | Dry solid |

| empty | Empty vessel |

| eq | Equivalent |

| H | Horizontal |

| Inner | |

| L | Liquid |

| Met | Metformin hydrochloride |

| rel | relative |

| SFC,end | Outlet of the SFC |

| SFC,start | Inlet of the SFC |

| slug | Slug |

| solid | Solid phase |

| solution | Solution (liquid phase) |

| stat | static |

| tot | total |

| tubing | Tubing |

| v | vertical |

References

- T. Wang, H. Lu, J. Wang, Y. Xiao, Y. Zhou, Y. Bao, H. Hao, Recent progress of continuous crystallization, Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 54 (2017) 14–29. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma, S. Wu, E.G.J. Macaringue, T. Zhang, J. Gong, J. Wang, Recent Progress in Continuous Crystallization of Pharmaceutical Products: Precise Preparation and Control, Org. Process Res. Dev. 24 (2020) 1785–1801. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Myerson, D. Erdemir, A.Y. Lee, Handbook of Industrial Crystallization, Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- A. Mersmann, Crystallization Technology Handbook, CRC Press, 2001.

- A. Lewis, M. Seckler, H. Kramer, G. van Rosmalen, Industrial Crystallization, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- J.W. Mullin, Industrial Crystallization, Springer US, Boston, MA, 1976.

- Advances in Industrial Crystallization, MDPI, 2021.

- B. Wood, K.P. Girard, C.S. Polster, D.M. Croker, Progress to Date in the Design and Operation of Continuous Crystallization Processes for Pharmaceutical Applications, Org. Process Res. Dev. 23 (2019) 122–144. [CrossRef]

- Z.K. Nagy, N. Yazdanpanah (Eds.), The Handbook of Continuous Crystallization, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020.

- M.L. Rasche, M. Jiang, R.D. Braatz, Mathematical modeling and optimal design of multi-stage slug-flow crystallization, Computers & Chemical Engineering 95 (2016) 240–248. [CrossRef]

- M. Jiang, Z. Zhu, E. Jimenez, C.D. Papageorgiou, J. Waetzig, A. Hardy, M. Langston, R.D. Braatz, Continuous-Flow Tubular Crystallization in Slugs Spontaneously Induced by Hydrodynamics, Crystal Growth & Design 14 (2014) 851–860. [CrossRef]

- M. Termühlen, B. Strakeljahn, G. Schembecker, K. Wohlgemuth, Characterization of slug formation towards the performance of air-liquid segmented flow, Chemical Engineering Science 207 (2019) 1288–1298. [CrossRef]

- M. Termühlen, M.M. Etmanski, I. Kryschewski, A.C. Kufner, G. Schembecker, K. Wohlgemuth, Continuous slug flow crystallization: Impact of design and operating parameters on product quality, Chemical Engineering Research and Design 170 (2021) 290–303. [CrossRef]

- M. Termühlen, B. Strakeljahn, G. Schembecker, K. Wohlgemuth, Quantification and evaluation of operating parameters’ effect on suspension behavior for slug flow crystallization, Chemical Engineering Science 243 (2021) 116771. [CrossRef]

- C. Steenweg, A.C. Kufner, J. Habicht, K. Wohlgemuth, Towards Continuous Primary Manufacturing Processes—Particle Design through Combined Crystallization and Particle Isolation, Processes 9 (2021) 2187. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Kufner, N. Westkämper, H. Bettin, K. Wohlgemuth, Prediction of Particle Suspension State for Various Particle Shapes Used in Slug Flow Crystallization, ChemEngineering 7 (2023) 34. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Kufner, M. Rix, K. Wohlgemuth, Modeling of Continuous Slug Flow Cooling Crystallization towards Pharmaceutical Applications, Processes 11 (2023) 2637. [CrossRef]

- A.C. Kufner, A. Krummnow, A. Danzer, K. Wohlgemuth, Strategy for Fast Decision on Material System Suitability for Continuous Crystallization Inside a Slug Flow Crystallizer, Micromachines 13 (2022). [CrossRef]

- S. Heisel, J. Ernst, A. Emshoff, G. Schembecker, K. Wohlgemuth, Shape-independent particle classification for discrimination of single crystals and agglomerates, Powder Technology 345 (2019) 425–437. [CrossRef]

- S. Heisel, M. Rolfes, K. Wohlgemuth, Discrimination between Single Crystals and Agglomerates during the Crystallization Process, Chem Eng & Technol 41 (2018) 1218–1225. [CrossRef]

- C. Steenweg, J. Habicht, K. Wohlgemuth, Continuous Isolation of Particles with Varying Aspect Ratios up to Thin Needles Achieving Free-Flowing Products, Crystals 12 (2022) 137. [CrossRef]

- W.K. Burton, N. Cabrera, F.C. Frank, The growth of crystals and the equilibrium structure of their surfaces, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 243 (1951) 299–358. [CrossRef]

- J.Y.Y. Heng, A. Bismarck, A.F. Lee, K. Wilson, D.R. Williams, Anisotropic surface energetics and wettability of macroscopic form I paracetamol crystals, Langmuir the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids 22 (2006) 2760–2769. [CrossRef]

- J.Y.Y. Heng, A. Bismarck, D.R. Williams, Anisotropic surface chemistry of crystalline pharmaceutical solids, AAPS PharmSciTech 7 (2006) 84. [CrossRef]

| Static contact angle / ° |

Capillary number Ca / - |

Slug shape | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arg/H2O | 93.26 ± 1.22 ° [18] | 8.7·10−4 [18] | Convex |

| APAP/H2O | 90.61 ± 1.62 ° [18] | 6.3·10−4 [18] | Convex |

| Met/H2O | 101.4 ± 1.99 ° | 2.76·10−3 | Convex |

|

/ K min-1 |

/ - |

/ - |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Arg/H2O | 0.45 K min-1 | 1.112 | 0.937 ± 0.02 |

| 1.8 K min-1 | 1.177 | 0.933 ± 0.05 | |

| APAP/H2O | 0.45 K min-1 | 1.042 | 0.987 ± 0.012 |

| 1.8 K min-1 | 1.066 | 0.986 ± 0.014 | |

| Met/H2O | 0.45 K min-1 | 1.055 | 0.903 ± 0.01 |

| 1.8 K min-1 | 1.054 | 0.894 ± 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).