Submitted:

28 December 2023

Posted:

29 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- a)

- antimicrobial peptides (AMPs);

- b)

- bacteriophages;

- c)

- nanotechnology;

- d)

- ethno-medicine; and

- e)

- probiotics and prebiotics

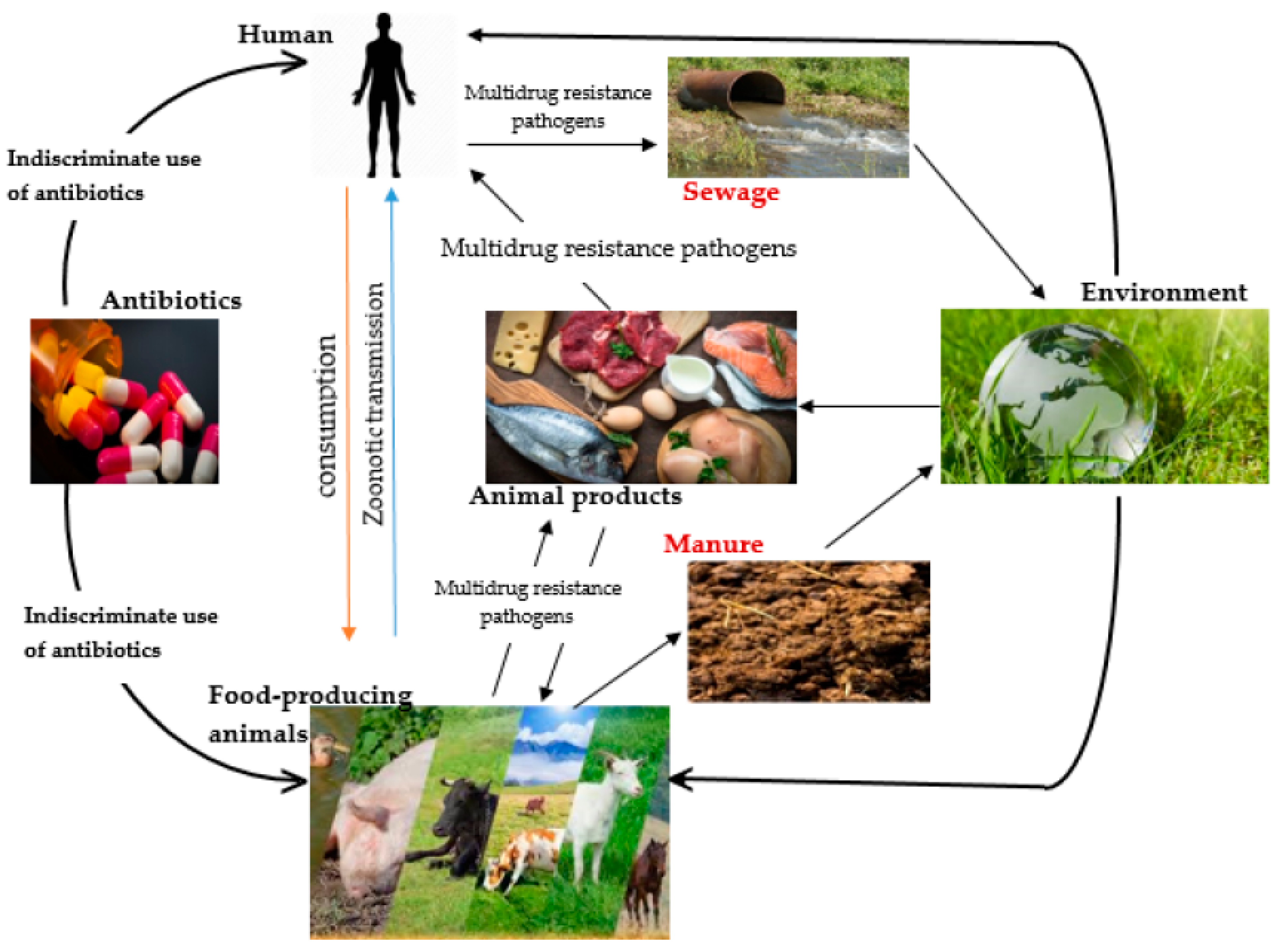

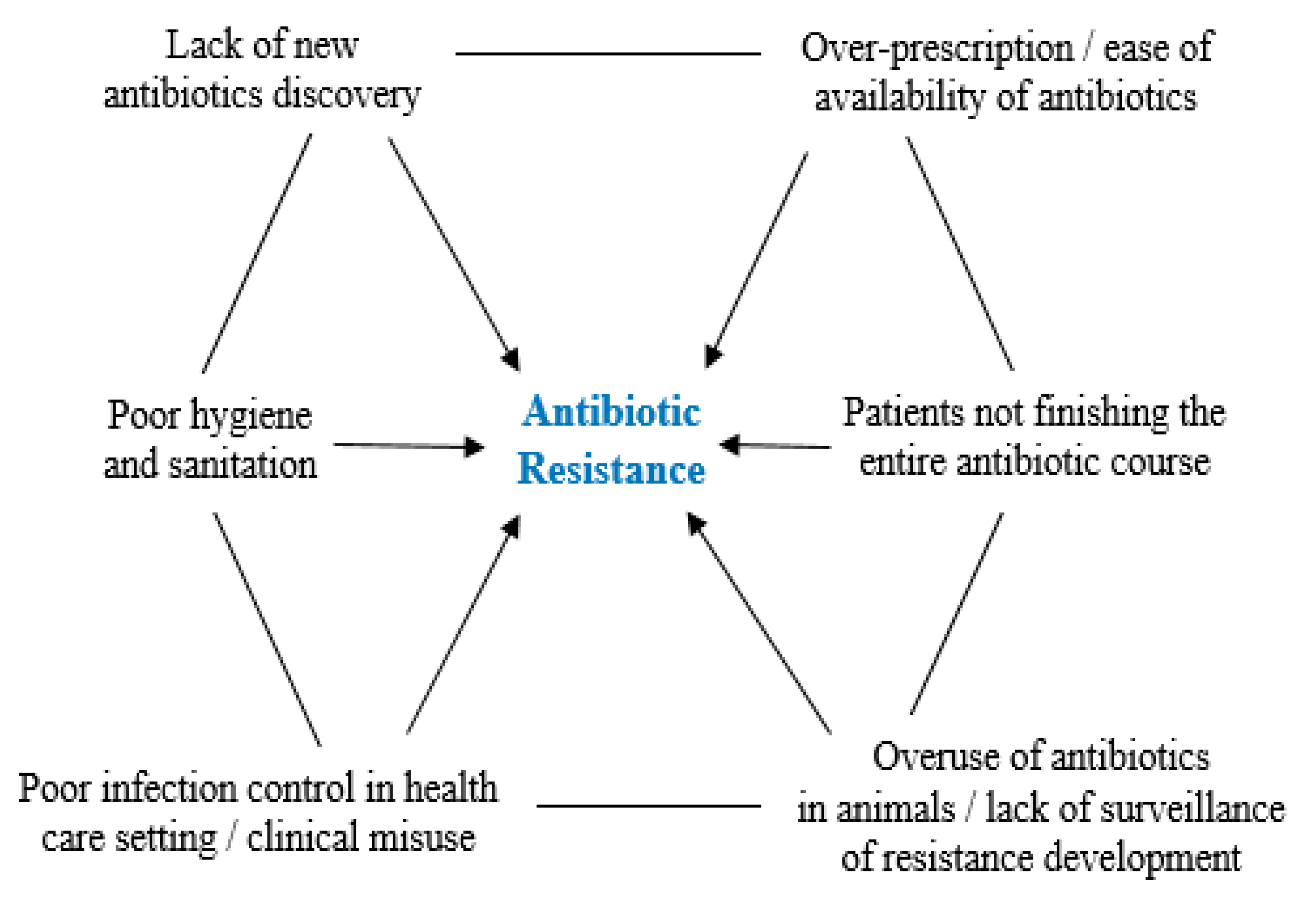

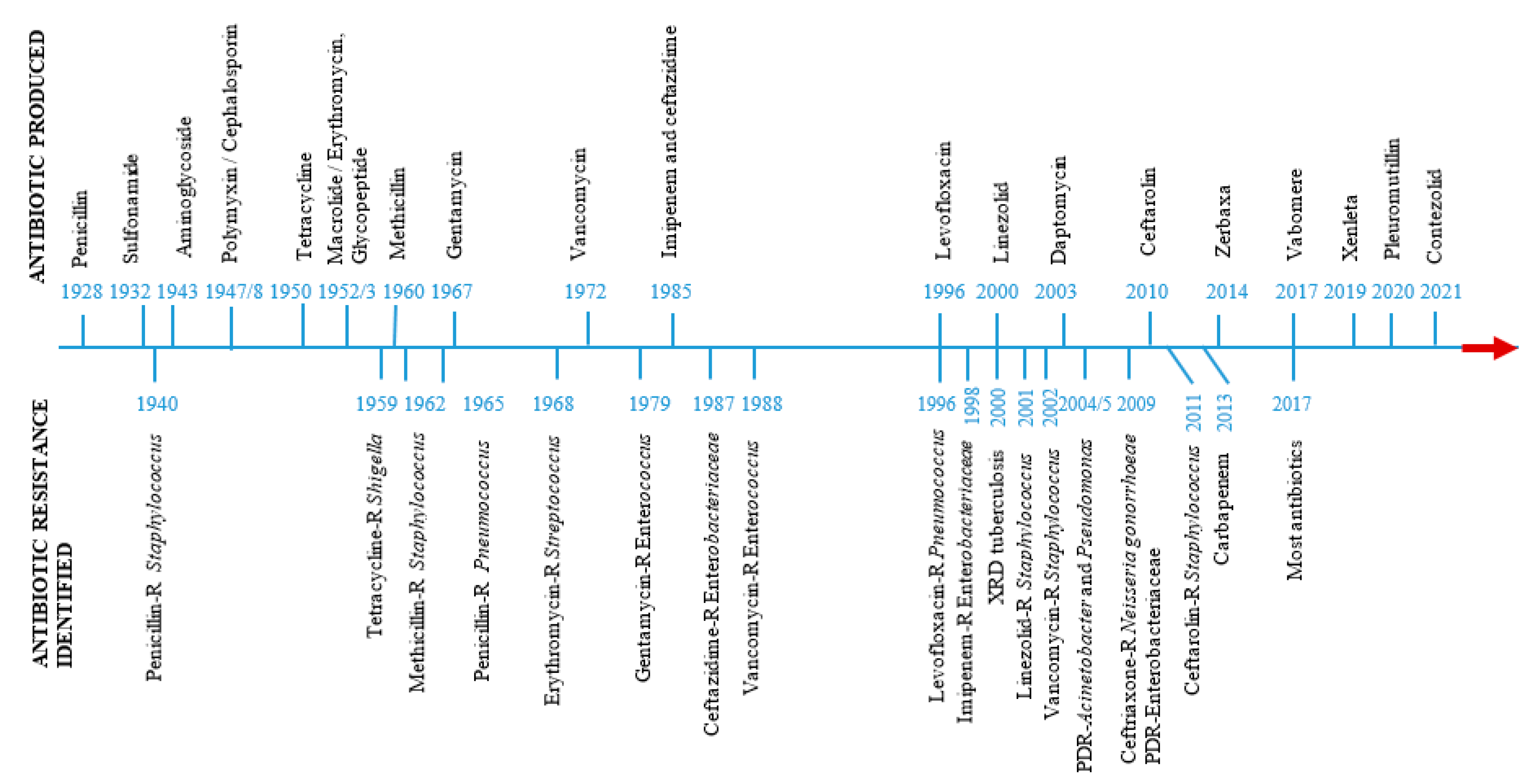

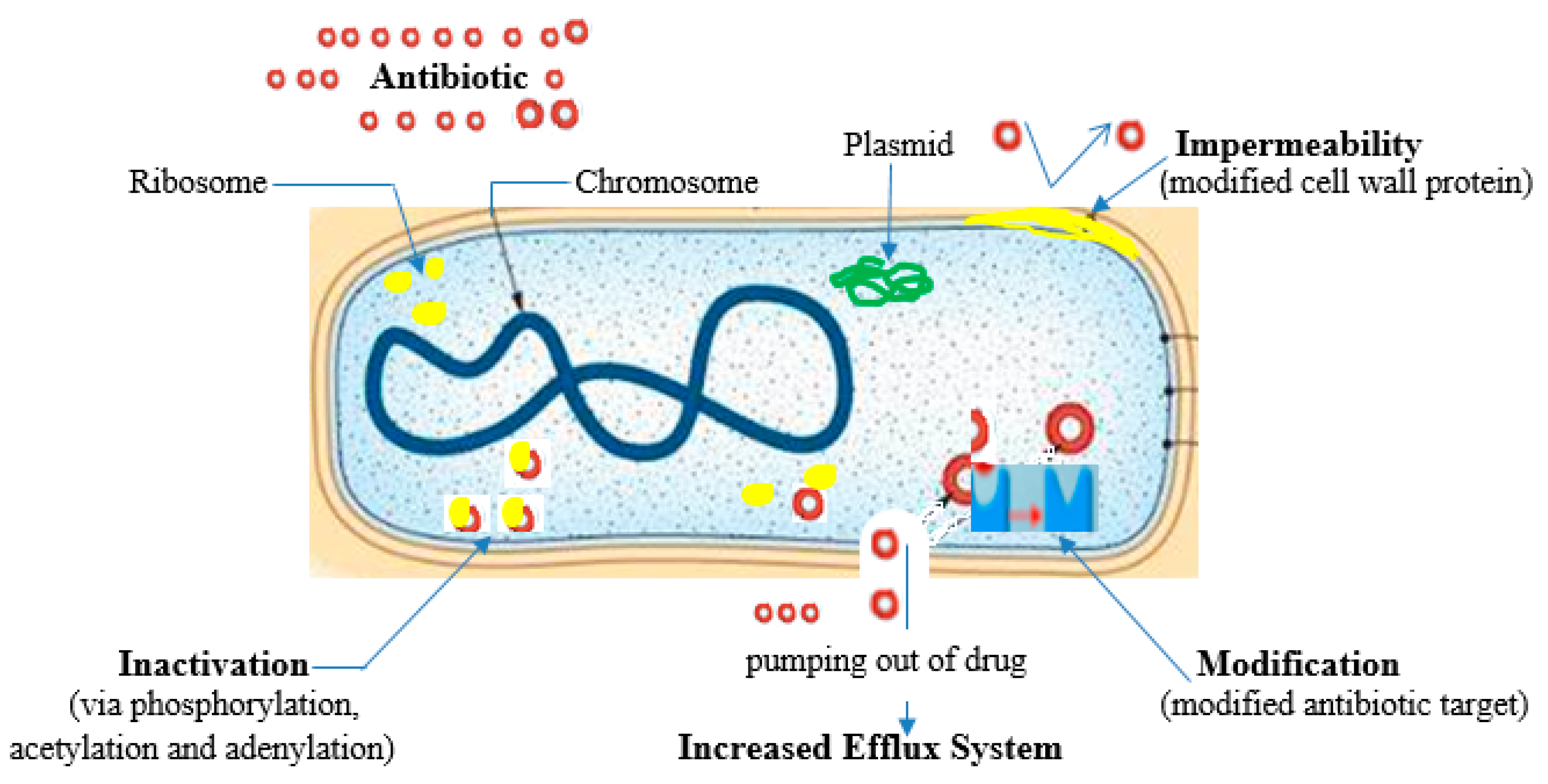

Mode of Action of Antibiotics and Emergence of Antibiotic Resistance

Antimicrobial Peptides

Antimicrobial Peptide Mode of Action

Antimicrobial Peptides as Therapeutic Agents

Bacteriophages

Mechanism of Action of Bacteriophages

Application of Bacteriophages as Bio-control Agents

Application of Bacteriophages as Bio-sensor

Regulations for the Application of Phage Therapy

Nanotechnology

Classification of Nanomaterials and their Properties

Applications of Nanotechnology

Ethno-Medicine

The Effect of Antibiotic Resistance on Sustainable Development Goals

Plants Secondary Metabolites: Key Drivers of Pharmacological Actions of Medicinal Plants

Ethno-Medicine as an Alternative to Antibiotic

Probiotics and Prebiotics

Applications and Mechanism of Action of Probiotics

Established Probiotics Risk Assessment Protocol

Conclusion and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ABDELRAHMAN, F., EASWARAN, M., DARAMOLA, O. I., RAGAB, S., LYNCH, S., ODUSELU, T. J., KHAN, F. M., AYOBAMI, A., ADNAN, F. & TORRENTS, E. Phage-encoded endolysins. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 124.

- ABEDON, S. T.Use of phage therapy to treat long-standing, persistent, or chronic bacterial infections. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2019, 145, 18–39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ABEYSEKERA, G. S., LOVE, M. J., MANNERS, S. H., BILLINGTON, C. & DOBSON, R. C. Bacteriophage-encoded lethal membrane disruptors: Advances in understanding and potential applications. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 1044143.

- ABOLARINWA, T. O., AJOSE, D. J., OLUWARINDE, B. O., FRI, J., MONTSO, K. P., FAYEMI, O. E., AREMU, A. O. & ATEBA, C. N. Plant-derived Nanoparticles as Alternative Therapy against diarrhoeal pathogens in the era of antimicrobial resistance: A review. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 4991.

- ADHIKARI, M. D., SAHA, T. & TIWARY, B. K. 2022. Quest for alternatives to antibiotics: An Urgent Need of the Twenty-First Century. Alternatives to Antibiotics. Springer.

- AHMAD, R., YU, Y.-H., HSIAO, F. S.-H., DYBUS, A., ALI, I., HSU, H.-C. & CHENG, Y.-H. Probiotics as a friendly antibiotic alternative: assessment of their effects on the health and productive performance of poultry. Fermentation 2022, 8, 672.

- AHOVAN, Z., HASHEMI, A., DE PLANO, L., GHOLIPOURMALEKABADI, M. & SEIFALIAN, A. Bacteriophage based biosensors: trends, outcomes and challenges. Nanomaterials 2020, 10.

- AJOSE, D. J., OLUWARINDE, B. O., ABOLARINWA, T. O., MONTSO, P. K., FAYEMI, O. E., AREMU, A. O. & ATEBA, C. N. Combating bovine mastitis in the dairy sector in an era of antimicrobial resistance: ethnoveterinary medicinal option as a viable alternative approach. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2022a, 10, 287.

- AJOSE, D. J., ABOLARINWA, T. O., OLUWARINDE, B. O., MONTSO, P. K., FAYEMI, O. E., AREMU, A. O. & ATEBA, C. N. Application of plant-derived nanoparticles (PDNP) in food-producing animals as a bio-control agent against antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. Biomedicines, 2022b, 2426.

- AJOSE, D. J. & OKOZI, M. O. Antibacterial activity of Ocimum gratissimum L. against some selected human bacterial pathogens. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 2017, 20, 1–8.

- AKMAL, M., RAHIMI-MIDANI, A., HAFEEZ-UR-REHMAN, M., HUSSAIN, A. & CHOI, T.-J. Isolation, characterization, and application of a bacteriophage infecting the fish pathogen Aeromonas hydrophila. Pathogens 2020, 9, 215.

- ALAYANDE, K. A., AIYEGORO, O. A. & ATEBA, C. N. Probiotics in animal husbandry: Applicability and associated risk factors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1087.

- ALLEN, H. K., TRACHSEL, J., LOOFT, T. & CASEY, T. A. Finding alternatives to antibiotics. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2014, 1323, 91–100.

- ALLI, K. & MANGAMOORI, L. N. Phytochemical compound identification and evaluation of antimicrobial activity of Eugenia Bracteata Roxb. International Journal of Biotechnology and Biochemistry 2016, 12, 73–83.

- ANBALAHAN, N. Pharmacological activity of mucilage isolated from medicinal plants. International Journal of Applied and Pure Science and Agriculture 2017, 3, 98–113.

- ANJU, T., RAI, N. K. S. & KUMAR, A. Sauropus androgynus (L.) Merr.: a multipurpose plant with multiple uses in traditional ethnic culinary and ethnomedicinal preparations. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2022, 9, 1–29.

- ANSARI, M. A., KALAM, A., AL-SEHEMI, A. G., ALOMARY, M. N., ALYAHYA, S., AZIZ, M. K., SRIVASTAVA, S., ALGHAMDI, S., AKHTAR, S. & ALMALKI, H. D. Counteraction of biofilm formation and antimicrobial potential of Terminalia catappa functionalized silver nanoparticles against Candida albicans and multidrug-resistant Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 725.

- ANSELMO, A. C. & MITRAGOTRI, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2016, 1, 10–29.

- ARNUSCH, C. J., PIETERS, R. J. & BREUKINK, E. Enhanced membrane pore formation through high-affinity targeted antimicrobial peptides. PLoS One 2012, 7, e39768.

- ASIF, H., AKRAM, M., SAEED, T., KHAN, M., AKHTAR, N., REHMAN, R., SHAH, S., AHMED, K. & SHAHEEN, G. Carbohydrates. Intern. Res. J. Biochem. Bioinformat 2011, 1, 1–5.

- ASLAM, S., LAMPLEY, E., WOOTEN, D., KARRIS, M., BENSON, C., STRATHDEE, S. & SCHOOLEY, R. T. Lessons learned from the first 10 consecutive cases of intravenous bacteriophage therapy to treat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections at a single center in the United States. Open forum infectious diseases, 2020. Oxford University Press US, ofaa389.

- AZIZI-LALABADI, M., HASHEMI, H., FENG, J. & JAFARI, S. M. Carbon nanomaterials against pathogens; the antimicrobial activity of carbon nanotubes, graphene/graphene oxide, fullerenes, and their nanocomposites. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 284, 102250.

- BARRON, M. 2022. Phage therapy: past, present and future. American Society for Microbiology.

- BENNETTS, H., UNDERWOOD, E. & SHIER, F. L. A specific breeding problem of sheep on subterranean clover pastures in western Australia. Veterinary Journal 1946, 102, 348–352.

- BISWARO, L. S., DA COSTA SOUSA, M. G., REZENDE, T. M., DIAS, S. C. & FRANCO, O. L. Antimicrobial peptides and nanotechnology, recent advances and challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 855.

- BRIERS, Y. Phage lytic enzymes. Viruses 2019, 11, 113. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BRUSOTTI, G., CESARI, I., DENTAMARO, A., CACCIALANZA, G. & MASSOLINI, G. Isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from plant resources: the role of analysis in the ethnopharmacological approach. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2014, 87, 218–228.

- BRÜSSOW, H. Hurdles for phage therapy to become a reality—an editorial comment. Viruses 2019, 11(6), 557. [CrossRef]

- CDC. 2022. ANTIMICROBIAL-RESISTANCE THREATENS SUCCESSFUL ACHIEVEMENT OF THE SDG TARGET [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/amr-sdg-pamphlet.pdf [Accessed December 26, 2022].

- CELANDRONI, F., VECCHIONE, A., CARA, A., MAZZANTINI, D., LUPETTI, A. & GHELARDI, E. Identification of Bacillus species: implication on the quality of probiotic formulations. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0217021.

- CENCIC, A. & CHINGWARU, W. The role of functional foods, nutraceuticals, and food supplements in intestinal health. Nutrients 2010, 2, 611–625.

- CHENG, C., ARRITT, F. & STEVENSON, C. Controlling Listeria monocytogenes in cold smoked salmon with the antimicrobial peptide salmine. Journal of Food Science 2015, 80, M1314–M1318.

- COFFEY, B., RIVAS, L., DUFFY, G., COFFEY, A., ROSS, R. P. & MCAULIFFE, O. Assessment of Escherichia coli O157: H7-specific bacteriophages e11/2 and e4/1c in model broth and hide environments. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2011, 147, 188–194.

- COLILLA, M. & VALLET-REGÍ, M. Targeted stimuli-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for bacterial infection treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8605.

- CORREIA, S., POETA, P., HÉBRAUD, M., CAPELO, J. L. & IGREJAS, G. Mechanisms of quinolone action and resistance: where do we stand? Journal of Medical Microbiology 2017, 66, 551–559.

- CROUZET, L., RIGOTTIER-GOIS, L. & SERROR, P. Potential use of probiotic and commensal bacteria as non-antibiotic strategies against vancomycin-resistant Enterococci. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2015, 362, fnv012.

- CULIOLI, G., MATHE, C., ARCHIER, P. & VIEILLESCAZES, C. A lupane triterpene from frankincense (Boswellia sp., Burseraceae). Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 537–541.

- CZAPLEWSKI, L., BAX, R., CLOKIE, M., DAWSON, M., FAIRHEAD, H., FISCHETTI, V. A., FOSTER, S., GILMORE, B. F., HANCOCK, R. E. & HARPER, D. Alternatives to antibiotics—a pipeline portfolio review. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2016, 16, 239–251.

- DAVIS, J. L. Pharmacologic principles. Equine Internal Medicine 2018, 4, 79–137.

- DE KRAKER, M. E., STEWARDSON, A. J. & HARBARTH, S. Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLoS Medicine 2016, 13, e1002184.

- DE MELO PEREIRA, G. V., DE OLIVEIRA COELHO, B., JÚNIOR, A. I. M., THOMAZ-SOCCOL, V. & SOCCOL, C. R. How to select a probiotic? A review and update of methods and criteria. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36, 2060–2076.

- DEEGAN, L. H., COTTER, P. D., HILL, C. & ROSS, P. Bacteriocins: biological tools for bio-preservation and shelf-life extension. International Dairy Journal 2006, 16, 1058–1071.

- DIJKSTEEL, G. S., ULRICH, M. M., MIDDELKOOP, E. & BOEKEMA, B. K. Lessons learned from clinical trials using antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 616979.

- DJEBARA, S., MAUSSEN, C., DE VOS, D., MERABISHVILI, M., DAMANET, B., PANG, K. W., DE LEENHEER, P., STRACHINARU, I., SOENTJENS, P. & PIRNAY, J.-P. Processing phage therapy requests in a Brussels military hospital: Lessons identified. Viruses 2019, 11, 265.

- DONOVAN, P. Access to unregistered drugs in Australia. Australian Prescriber 2017, 40, 194. [CrossRef]

- DOWLING, A., O’DWYER, J. & ADLEY, C. Antibiotics: mode of action and mechanisms of resistance. Antimicrobial Research: Novel Bioknowledge and Educational Programs 2017, 1, 536–545.

- EFSA, E. P. O. B. H. Scientific Opinion on the evaluation of the safety and efficacy of Listex™ P100 for the removal of Listeria monocytogenes surface contamination of raw fish. EFSA Journal 2012, 10, 2615.

- EFSA, E. P. O. B. H. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of Listex™ P100 for reduction of pathogens on different ready-to-eat (RTE) food products. EFSA Journal 2016, 14, e04565.

- FAHY, E., SUBRAMANIAM, S., MURPHY, R. C., NISHIJIMA, M., RAETZ, C. R., SHIMIZU, T., SPENER, F., VAN MEER, G., WAKELAM, M. J. & DENNIS, E. A. Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids1. Journal of Lipid Research 2009, 50, S9–S14.

- FANG, K., JIN, X. & HONG, S. H. Probiotic Escherichia coli inhibits biofilm formation of pathogenic E. coli via extracellular activity of DegP. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 1–12.

- FAO/WHO 2002. Joint FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 30 April and 1 May 2002.

- FAO/WHO. 2006. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Evaluation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Powder Milk with Live. In Health and Nutrition Properties of Probiotics in Food including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 85; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006 [Online]. Available: https://www.fao.org/3/a0512e/a0512e.pdf [Accessed December 27, 2022].

- FERREIRA, A., PEREIRA-MANFRO, W. & ROSA, A. D. P. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli and probiotic activity against foodborne pathogens: a brief review. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access 2017, 7, 00248.

- FISCARELLI, E. V., ROSSITTO, M., ROSATI, P., ESSA, N., CROCETTA, V., DI GIULIO, A., LUPETTI, V., DI BONAVENTURA, G. & POMPILIO, A. In vitro newly isolated environmental phage activity against biofilms preformed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 478.

- FRIZZO, L. S., SIGNORINI, M. L. & ROSMINI, M. R. 2018. Probiotics and prebiotics for the health of cattle. Probiotics and prebiotics in animal health and food safety. Springer.

- FUERTES, G., GIMÉNEZ, D., ESTEBAN-MARTÍN, S., SÁNCHEZ-MUNOZ, O. L. & SALGADO, J. A lipocentric view of peptide-induced pores. European Biophysics Journal 2011, 40, 399–415.

- GAO, Y., CHEN, Y., CAO, Y., MO, A. & PENG, Q. Potentials of nanotechnology in treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 213, 113056.

- GHARPURE, S., AKASH, A. & ANKAMWAR, B. A review on antimicrobial properties of metal nanoparticles. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2020, 20, 3303–3339.

- GHOSH, C., SARKAR, P., ISSA, R. & HALDAR, J. Alternatives to conventional antibiotics in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Trends in Microbiology 2019, 27, 323–338.

- GIBB, B., HYMAN, P. & SCHNEIDER, C. L. The many applications of engineered bacteriophages—An overview. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 634.

- GOŁAWSKA, S., SPRAWKA, I., ŁUKASIK, I. & GOŁAWSKI, A. Are naringenin and quercetin useful chemicals in pest-management strategies? Journal of pest science 2014, 87, 173–180.

- GONDIL, V. S., HARJAI, K. & CHHIBBER, S. Endolysins as emerging alternative therapeutic agents to counter drug-resistant infections. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2020, 55, 105844.

- GOYAL, P., BELAPURKAR, P. & KAR, A. A review on in vitro and in vivo bioremediation potential of environmental and probiotic species of Bacillus and other probiotic microorganisms for two heavy metals, cadmium and nickel. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia 2019, 16, 01–13.

- GRASSI, L., MAISETTA, G., ESIN, S. & BATONI, G. Combination strategies to enhance the efficacy of antimicrobial peptides against bacterial biofilms. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8, 2409.

- GUPTA, A., MUMTAZ, S., LI, C.-H., HUSSAIN, I. & ROTELLO, V. M. Combatting antibiotic-resistant bacteria using nanomaterials. Chemical Society Reviews 2019a, 48, 415–427.

- GUPTA, K., SINGH, S. P., MANHAR, A. K., SAIKIA, D., NAMSA, N. D., KONWAR, B. K. & MANDAL, M. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm and virulence by active fraction of Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels leaf extract: in-vitro and in silico studies. Indian Journal of Microbiology, 2019b, 59, 13–21.

- HARBORNE, J. B. Classes and functions of secondary products from plants. Chemicals from Plants 1999, 26, 1–25.

- HARISH, K. & VARGHESE, T. Probiotics in humans–evidence based review. Calicut Med J, 2006, 4, e3.

- HELMY, Q., KARDENA, E. & GUSTIANI, S. 2019. Probiotics and bioremediation. Microorganisms. IntechOpen.

- HOF, W. V. T., VEERMAN, E. C., HELMERHORST, E. J. & AMERONGEN, A. V. N. Antimicrobial peptides: properties and applicability. Biological Chemistry 2001, 382, 597–619.

- HOFFMANN, D. 2003. Medical herbalism: the science and practice of herbal medicine, Simon and Schuster.

- HOFFMANN, S. A., MACULLOCH, B. & BATZ, M. 2015. Economic burden of major foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- HU, B., PAN, Y., LI, Z., YUAN, W. & DENG, L. EmPis-1L, an effective antimicrobial peptide against the antibiotic-resistant VBNC state cells of pathogenic bacteria. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2019, 11, 667–675.

- HUAN, Y., KONG, Q., MOU, H. & YI, H. Antimicrobial peptides: classification, design, application and research progress in multiple fields. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 2559.

- HUANG, H. W. Action of antimicrobial peptides: two-state model. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 8347–8352. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HUDSON, J., BILLINGTON, C., PREMARATNE, A. & ON, S. L. Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157: H7 using ultraviolet light-treated bacteriophages. Food Science and Technology International 2016, 22, 3–9.

- HUMPHRIES, R. M., POLLETT, S. & SAKOULAS, G. A current perspective on daptomycin for the clinical microbiologist. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2013, 26, 759–780.

- HUSSEIN, R. A. & EL-ANSSARY, A. A. Plants secondary metabolites: the key drivers of the pharmacological actions of medicinal plants. Herb. Med 2019, 1.

- IBRAHIM, R. A., CRYER, T. L., LAFI, S. Q., BASHA, E.-A., GOOD, L. & TARAZI, Y. H. Identification of Escherichia coli from broiler chickens in Jordan, their antimicrobial resistance, gene characterization and the associated risk factors. BMC Veterinary Research 2019, 15, 1–16.

- ISOLAURI, E., KIRJAVAINEN, P. & SALMINEN, S. Probiotics: a role in the treatment of intestinal infection and inflammation? Gut 2002, 50, iii54–iii59.

- JAGLAN, A. B., ANAND, T., VERMA, R., VASHISTH, M., VIRMANI, N., BERA, B. C., VAID, R. K. & TRIPATHI, B. N. Tracking the phage trends: A comprehensive review of applications in therapy and food production. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13.

- JAHN, S., SEIWERT, B., KRETZING, S., ABRAHAM, G., REGENTHAL, R. & KARST, U. Metabolic studies of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloids galantamine and lycorine based on electrochemical simulation in addition to in vivo and in vitro models. Analytica Chimica Acta 2012, 756, 60–72.

- JAROW, J. P., LURIE, P., IKENBERRY, S. C. & LEMERY, S. Overview of FDA’s expanded access program for investigational drugs. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 2017, 51, 177–179.

- JEPSON, R. G. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Sao Paulo Medical Journal 2013, 131, 363–363. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JIANG, H., CHENG, H., LIANG, Y., YU, S., YU, T., FANG, J. & ZHU, C. Diverse mobile genetic elements and conjugal transferability of sulfonamide resistance genes (sul1, sul2, and sul3) in Escherichia coli isolates from Penaeus vannamei and pork from large markets in Zhejiang, China. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 1787.

- KANG, H.-K., KIM, C., SEO, C. H. & PARK, Y. The therapeutic applications of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): a patent review. Journal of Microbiology 2017, 55, 1–12.

- KESAVELU, D., ROHIT, A., KARUNASAGAR, I. & KARUNASAGAR, I. Composition and laboratory correlation of commercial probiotics in India. Cureus 2020, 12, e11334.

- KIM, M. J., KU, S., KIM, S. Y., LEE, H. H., JIN, H., KANG, S., LI, R., JOHNSTON, T. V., PARK, M. S. & JI, G. E. Safety evaluations of Bifidobacterium bifidum BGN4 and Bifidobacterium longum BORI. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1422.

- KORF, I. H., MEIER-KOLTHOFF, J. P., ADRIAENSSENS, E. M., KROPINSKI, A. M., NIMTZ, M., ROHDE, M., VAN RAAIJ, M. J. & WITTMANN, J. Still something to discover: Novel insights into Escherichia coli phage diversity and taxonomy. Viruses 2019, 11, 454.

- LARSSON, D. & FLACH, C.-F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2022, 20, 257–269.

- LE, C.-F., FANG, C.-M. & SEKARAN, S. D. Intracellular targeting mechanisms by antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2017, 61, e02340–16.

- LE, T. S., SOUTHGATE, P. C., O’CONNOR, W., POOLE, S. & KURTBӦKE, D. I. Bacteriophages as biological control agents of enteric bacteria contaminating edible oysters. Current Microbiology 2018, 75, 611–619.

- LEE, N.-Y., KO, W.-C. & HSUEH, P.-R. Nanoparticles in the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10, 1153.

- LEE, S., LEE, J., JIN, Y.-I., JEONG, J.-C., CHANG, Y. H., LEE, Y., JEONG, Y. & KIM, M. Probiotic characteristics of Bacillus strains isolated from Korean traditional soy sauce. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 79, 518–524.

- LEI, J., SUN, L., HUANG, S., ZHU, C., LI, P., HE, J., MACKEY, V., COY, D. H. & HE, Q. The antimicrobial peptides and their potential clinical applications. American Journal of Translational Research 2019, 11, 3919.

- LI, W., O’BRIEN-SIMPSON, N. M., HOLDEN, J. A., OTVOS, L., REYNOLDS, E. C., SEPAROVIC, F., HOSSAIN, M. A. & WADE, J. D. Covalent conjugation of cationic antimicrobial peptides with a β-lactam antibiotic core. Peptide Science 2018, 110, e24059.

- LI, W., TAILHADES, J., O’BRIEN-SIMPSON, N. M., SEPAROVIC, F., OTVOS, L., HOSSAIN, M. A. & WADE, J. D. Proline-rich antimicrobial peptides: potential therapeutics against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Amino acids 2014, 46, 2287–2294.

- LI, Z., LI, X., ZHANG, J., WANG, X., WANG, L., CAO, Z. & XU, Y. Use of phages to control Vibrio splendidus infection in the juvenile sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2016, 54, 302–311.

- ŁOBODA, D., KOZŁOWSKI, H. & ROWIŃSKA-ŻYREK, M. Antimicrobial peptide–metal ion interactions–a potential way of activity enhancement. New Journal of Chemistry 2018, 42, 7560–7568.

- ŁOJEWSKA, E. & SAKOWICZ, T. An Alternative to Antibiotics: Selected Methods to Combat Zoonotic Foodborne Bacterial Infections. Current Microbiology 2021, 78, 4037–4049.

- LUO, X., LIAO, G., LIU, C., JIANG, X., LIN, M., ZHAO, C., TAO, J. & HUANG, Z. Characterization of bacteriophage HN 48 and its protective effects in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus against Streptococcus agalactiae infections. Journal of Fish Diseases 2018, 41, 1477–1484.

- MANOHAR, P., LOH, B. & LEPTIHN, S. Will the overuse of antibiotics during the Coronavirus pandemic accelerate antimicrobial resistance of bacteria? Infectious Microbes and Diseases 2020, 2, 87–88.

- MARTINEZ, S. R., IBARRA, L. E., PONZIO, R. A., FORCONE, M. V., WENDEL, A. B., CHESTA, C. A., SPESIA, M. B. & PALACIOS, R. E. Photodynamic inactivation of ESKAPE group bacterial pathogens in planktonic and biofilm cultures using metallated porphyrin-doped conjugated polymer nanoparticles. ACS Infectious Diseases 2020, 6, 2202–2213.

- MASOTTI, V., JUTEAU, F., BESSIÈRE, J. M. & VIANO, J. Seasonal and phenological variations of the essential oil from the narrow endemic species Artemisia molinieri and its biological activities. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2003, 51, 7115–7121.

- MBA, I. E. & NWEZE, E. I. Nanoparticles as therapeutic options for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria: Research progress, challenges, and prospects. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2021, 37, 1–30.

- MCGAW, L. J., FAMUYIDE, I. M., KHUNOANA, E. T. & AREMU, A. O. Ethnoveterinary botanical medicine in South Africa: A review of research from the last decade (2009 to 2019). Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2020, 257, 112864.

- MCLINDEN, T., SARGEANT, J. M., THOMAS, M. K., PAPADOPOULOS, A. & FAZIL, A. Component costs of foodborne illness: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–12.

- MEILE, S., KILCHER, S., LOESSNER, M. J. & DUNNE, M. Reporter phage-based detection of bacterial pathogens: Design guidelines and recent developments. Viruses 2020, 12, 944.

- MITEVA, M., ANDERSSON, M., KARSHIKOFF, A. & OTTING, G. Molecular electroporation: a unifying concept for the description of membrane pore formation by antibacterial peptides, exemplified with NK-lysin. FEBS Letters 1999, 462, 155–158.

- MITRA, D., KANG, E.-T. & NEOH, K. G. Polymer-based coatings with integrated antifouling and bactericidal properties for targeted biomedical applications. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2021, 3, 2233–2263.

- MOHAMED, F. M., THABET, M. H. & ALI, M. F. The use of probiotics to enhance immunity of broiler chicken against some intestinal infection pathogens. SVU-International Journal of Veterinary Sciences 2019, 2, 1–19.

- MOHAMMED, I., SAID, D. G. & DUA, H. S. Human antimicrobial peptides in ocular surface defense. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2017, 61, 1–22.

- MOLCHANOVA, N., HANSEN, P. R. & FRANZYK, H. Advances in development of antimicrobial peptidomimetics as potential drugs. Molecules 2017, 22, 1430.

- MONTANHER, A. B., ZUCOLOTTO, S. M., SCHENKEL, E. P. & FRÖDE, T. S. Evidence of anti-inflammatory effects of Passiflora edulis in an inflammation model. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2007, 109, 281–288.

- MONTSO, P. K., MLAMBO, V. & ATEBA, C. N. Characterization of lytic bacteriophages infecting multidrug-resistant shiga toxigenic atypical Escherichia coli O177 strains isolated from cattle feces. Frontiers in Public Health 2019, 7, 355.

- MONTSO, P. K., MNISI, C. M., ATEBA, C. N. & MLAMBO, V. An assessment of the viability of lytic phages and their potency against multidrug resistant Escherichia coli O177 strains under simulated rumen fermentation conditions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 265.

- MÖSGES, R., BAUES, C., SCHRÖDER, T. & SAHIN, K. Acute bacterial otitis externa: efficacy and safety of topical treatment with an antibiotic ear drop formulation in comparison to glycerol treatment. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2011, 27, 871–878.

- MOSTOWY, S. Louis Pasteur continues to shape the future of microbiology. Disease Models and Mechanisms 2022, 15, dmm050011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MUBEEN, B., ANSAR, A. N., RASOOL, R., ULLAH, I., IMAM, S. S., ALSHEHRI, S., GHONEIM, M. M., ALZAREA, S. I., NADEEM, M. S. & KAZMI, I. Nanotechnology as a novel approach in combating microbes providing an alternative to antibiotics. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1473.

- MULANI, M. S., KAMBLE, E. E., KUMKAR, S. N., TAWRE, M. S. & PARDESI, K. R. Emerging strategies to combat ESKAPE pathogens in the era of antimicrobial resistance: a review. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 539.

- MURUGAIYAN, J., KUMAR, P. A., RAO, G. S., ISKANDAR, K., HAWSER, S., HAYS, J. P., MOHSEN, Y., ADUKKADUKKAM, S., AWUAH, W. A. & JOSE, R. A. M. Progress in alternative strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance: Focus on antibiotics. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 200.

- MWINGA, J. L., OTANG-MBENG, W., KUBHEKA, B. P. & AREMU, A. O. Ethnobotanical survey of plants used by subsistence farmers in mitigating cabbage and spinach diseases in OR Tambo Municipality, South Africa. Plants 2022, 11, 3215.

- NANDA, A. M., THORMANN, K. & FRUNZKE, J. Impact of spontaneous prophage induction on the fitness of bacterial populations and host-microbe interactions. Journal of Bacteriology 2015, 197, 410–419.

- NGUYEN, F., STAROSTA, A. L., ARENZ, S., SOHMEN, D., DÖNHÖFER, A. & WILSON, D. N. Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance mechanisms. Biological Chemistry 2014, 395, 559–575.

- NGUYEN, L. T., HANEY, E. F. & VOGEL, H. J. The expanding scope of antimicrobial peptide structures and their modes of action. Trends in Biotechnology 2011, 29, 464–472.

- NIEMEYER, J. C., LOLATA, G. B., DE CARVALHO, G. M., DA SILVA, E. M., SOUSA, J. P. & NOGUEIRA, M. A. Microbial indicators of soil health as tools for ecological risk assessment of a metal contaminated site in Brazil. Applied Soil Ecology 2012, 59, 96–105.

- NIKOLICH, M. P. & FILIPPOV, A. A. Bacteriophage therapy: developments and directions. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 135.

- OUWEHAND, A. C., FORSSTEN, S., HIBBERD, A. A., LYRA, A. & STAHL, B. Probiotic approach to prevent antibiotic resistance. Annals of Medicine 2016, 48, 246–255.

- PALMA, E., TILOCCA, B. & RONCADA, P. Antimicrobial resistance in veterinary medicine: An overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 1914.

- PARK, K. H., OH, S.-Y., YOO, S., FONG, J. J., KIM, C. S., JO, J. W. & LIM, Y. W. Influence of season and soil properties on fungal communities of neighboring climax forests (Carpinus cordata and Fraxinus rhynchophylla). Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 2643.

- PASUPULETI, M., SCHMIDTCHEN, A. & MALMSTEN, M. Antimicrobial peptides: key components of the innate immune system. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2012, 32, 143–171.

- PATEL, P. H. & HASHMI, M. F. 2021. Macrolides. StatPearls StatPearls Publishing, Tampa, FL, USA.

- PELCZAR, M., CHAN, E. & KRIEG, N. Control of microorganisms, the control of microorganisms by physical agents. Microbiology 1988, 469, 509.

- PELFRENE, E., BOTGROS, R. & CAVALERI, M. Antimicrobial multidrug resistance in the era of COVID-19: a forgotten plight? Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 2021, 10, 1–6.

- PETERSON, E. & KAUR, P. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms in bacteria: relationships between resistance determinants of antibiotic producers, environmental bacteria, and clinical pathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 2928.

- PETSONG, K., BENJAKUL, S., CHATURONGAKUL, S., SWITT, A. I. M. & VONGKAMJAN, K. Lysis profiles of Salmonella phages on Salmonella isolates from various sources and efficiency of a phage cocktail against S. enteritidis and S. typhimurium. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 100.

- PINTO, G., ALMEIDA, C. & AZEREDO, J. Bacteriophages to control shiga toxin-producing E. coli–safety and regulatory challenges. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2020, 40, 1081–1097.

- PIRNAY, J.-P., VERBEKEN, G., CEYSSENS, P.-J., HUYS, I., DE VOS, D., AMELOOT, C. & FAUCONNIER, A. The magistral phage. Viruses 2018, 10, 64.

- PLESSAS, S., NOUSKA, C., KARAPETSAS, A., KAZAKOS, S., ALEXOPOULOS, A., MANTZOURANI, I., CHONDROU, P., FOURNOMITI, M., GALANIS, A. & BEZIRTZOGLOU, E. Isolation, characterization and evaluation of the probiotic potential of a novel Lactobacillus strain isolated from feta-type cheese. Food Chemistry 2017, 226, 102–108.

- POKORNY, A., BIRKBECK, T. H. & ALMEIDA, P. F. Mechanism and kinetics of δ-lysin interaction with phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 11044–11056.

- PRADO, M., BLANDÓN, L., VANDENBERGHE, L., RODRIGUES, C., CASTRO, G., THOMAZ-SOCCOL, V. & SOCCOL, C. Milk kefir: composition, microbial cultures, biological activities, and related products. Frontiers in Microbiology 2015, 30, 1177.

- PRASHER, P., SINGH, M. & MUDILA, H. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial therapeutics: current perspectives and future challenges. Biotech 2018, 8, 1–23.

- RABANAL, F. & CAJAL, Y. Recent advances and perspectives in the design and development of polymyxins. Natural Product Reports 2017, 34, 886–908.

- RAMIREZ, K., CAZAREZ-MONTOYA, C., LOPEZ-MORENO, H. S. & CASTRO-DEL CAMPO, N. Bacteriophage cocktail for biocontrol of Escherichia coli O157: H7: Stability and potential allergenicity study. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0195023.

- REINHARDT, A. & NEUNDORF, I. Design and application of antimicrobial peptide conjugates. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 701.

- RIBER, C. F., SMITH, A. A. & ZELIKIN, A. N. Self-Immolative linkers literally bridge disulfide chemistry and the realm of Thiol-free drugs. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2015, 4, 1887–1890.

- RIMA, M., RIMA, M., FAJLOUN, Z., SABATIER, J.-M., BECHINGER, B. & NAAS, T. Antimicrobial peptides: A potent alternative to antibiotics. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1095.

- RINGØ, E. Probiotics in shellfish aquaculture. Aquaculture and Fisheries 2020, 5, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- RITSEMA, J. A., DER WEIDE, H. V., TE WELSCHER, Y. M., GOESSENS, W. H., VAN NOSTRUM, C. F., STORM, G., BAKKER-WOUDENBERG, I. A. & HAYS, J. P. Antibiotic-nanomedicines: facing the challenge of effective treatment of antibiotic-resistant respiratory tract infections. Future Microbiology 2018, 13, 1683–1692.

- ROBBINS, T., BU, D. & CARRIQUE-MAS, J. F evre. EM, Gilbert, M., Grace, D., Hay, SI, Jiwakanon, J., Kakkar, M., Kariuki, S., Laxminarayan, R., Lubroth, J., Magnusson, U., Thi Ngoc, P., van Bockel, TP and Woolhouse. MEJ 2016, 1–3.

- RUDRAMURTHY, G. R., SWAMY, M. K., SINNIAH, U. R. & GHASEMZADEH, A. Nanoparticles: alternatives against drug-resistant pathogenic microbes. Molecules 2016, 21, 836.

- SAN MILLAN, A. Evolution of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in the clinical context. Trends in Microbiology 2018, 26, 978–985. [CrossRef]

- SÁNCHEZ-LÓPEZ, E., GOMES, D., ESTERUELAS, G., BONILLA, L., LOPEZ-MACHADO, A. L., GALINDO, R., CANO, A., ESPINA, M., ETTCHETO, M. & CAMINS, A. Metal-based nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: an overview. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 292.

- SEIGLER, D. S. 1998. Indole Alkaloids. Plant Secondary Metabolism. Springer.

- SHAI, Y. & OREN, Z. From “carpet” mechanism to de-novo designed diastereomeric cell-selective antimicrobial peptides. Peptides 2001, 22, 1629–1641.

- SHEARD, D. E., O’BRIEN-SIMPSON, N. M., WADE, J. D. & SEPAROVIC, F. Combating bacterial resistance by combination of antibiotics with antimicrobial peptides. Pure and Applied Chemistry 2019, 91, 199–209.

- SHIN, S. W., SHIN, M. K., JUNG, M., BELAYNEHE, K. M. & YOO, H. S. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and transfer of tetracycline resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolates from beef cattle. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2015, 81, 5560–5566.

- SHOUSHA, A., AWAIWANONT, N., SOFKA, D., SMULDERS, F. J., PAULSEN, P., SZOSTAK, M. P., HUMPHREY, T. & HILBERT, F. Bacteriophages isolated from chicken meat and the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2015, 81, 4600–4606.

- SIERRA, J. M., FUSTÉ, E., RABANAL, F., VINUESA, T. & VIÑAS, M. An overview of antimicrobial peptides and the latest advances in their development. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 2017, 17, 663–676.

- SILLANKORVA, S. M., OLIVEIRA, H. & AZEREDO, J. Bacteriophages and their role in food safety. Bacteriophages and their role in food safety. International Journal of Microbiology 2012, 2012.

- SINGH, A. P., BISWAS, A., SHUKLA, A. & MAITI, P. Targeted therapy in chronic diseases using nanomaterial-based drug delivery vehicles. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2019, 4, 1–21.

- SLAVIN, Y. N., ASNIS, J., HÄFELI, U. O. & BACH, H. Metal nanoparticles: understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2017, 15, 1–20.

- SOLOMON, S. L. & OLIVER, K. B. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States: stepping back from the brink. American Family Physician 2014, 89, 938–941.

- SPILLER, F., ALVES, M. K., VIEIRA, S. M., CARVALHO, T. A., LEITE, C. E., LUNARDELLI, A., POLONI, J. A., CUNHA, F. Q. & DE OLIVEIRA, J. R. Anti-inflammatory effects of red pepper (Capsicum baccatum) on carrageenan-and antigen-induced inflammation. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2008, 60, 473–478.

- SPIRESCU, V. A., CHIRCOV, C., GRUMEZESCU, A. M. & ANDRONESCU, E. Polymeric nanoparticles for antimicrobial therapies: An up-to-date overview. Polymers 2021, 13, 724.

- STEVENSON, C. L. Advances in peptide pharmaceuticals. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology 2009, 10, 122–137. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SUBRAMANIAM, S., FAHY, E., GUPTA, S., SUD, M., BYRNES, R. W., COTTER, D., DINASARAPU, A. R. & MAURYA, M. R. Bioinformatics and systems biology of the lipidome. Chemical reviews 2011, 111, 6452–6490.

- SUMI, C. D., YANG, B. W., YEO, I.-C. & HAHM, Y. T. Antimicrobial peptides of the genus Bacillus: a new era for antibiotics. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 2015, 61, 93–103.

- SURESH, K., KRISHNAPPA, S. & BHARDWAJ, P. Safety concerns of Probiotic use: a review. Safety 2013, 34, 40.

- TANG, R., YU, H., QI, M., YUAN, X., RUAN, Z., HU, C., XIAO, M., XUE, Y., YAO, Y. & LIU, Q. Biotransformation of citrus fruits phenolic profiles by mixed probiotics in vitro anaerobic fermentation. LWT 2022, 160, 113087.

- TILOCCA, B., BALMAS, V., HASSAN, Z. U., JAOUA, S. & MIGHELI, Q. A proteomic investigation of Aspergillus carbonarius exposed to yeast volatilome or to its major component 2-phenylethanol reveals major shifts in fungal metabolism. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2019, 306, 108265.

- TOMAT, D., CASABONNE, C., AQUILI, V., BALAGUÉ, C. & QUIBERONI, A. Evaluation of a novel cocktail of six lytic bacteriophages against shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in broth, milk and meat. Food Microbiology 2018, 76, 434–442.

- TOOKE, C. L., HINCHLIFFE, P., BRAGGINTON, E. C., COLENSO, C. K., HIRVONEN, V. H., TAKEBAYASHI, Y. & SPENCER, J. β-Lactamases and β-Lactamase Inhibitors in the 21st Century. Journal of Molecular Biology 2019, 431, 3472–3500.

- TORCATO, I. M., HUANG, Y.-H., FRANQUELIM, H. G., GASPAR, D., CRAIK, D. J., CASTANHO, M. A. & HENRIQUES, S. T. Design and characterization of novel antimicrobial peptides, R-BP100 and RW-BP100, with activity against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes 2013, 1828, 944–955.

- VALLABANI, N. & SINGH, S. Recent advances and future prospects of iron oxide nanoparticles in biomedicine and diagnostics. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 1–23.

- VANHEE, L. M., GOEMÉ, F., NELIS, H. J. & COENYE, T. Quality control of fifteen probiotic products containing Saccharomyces boulardii. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2010, 109, 1745–1752.

- VANKERCKHOVEN, V., HUYS, G., VANCANNEYT, M., VAEL, C., KLARE, I., ROMOND, M.-B., ENTENZA, J. M., MOREILLON, P., WIND, R. D., KNOL, J., WIERTZ, E., POT, B., VAUGHAN, E. E., KAHLMETER, G. & GOOSSENS, H. Biosafety assessment of probiotics used for human consumption: recommendations from the EU-PROSAFE project. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2008, 19, 102–114.

- VENTOLA, C. L. Progress in nanomedicine: approved and investigational nanodrugs. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2017, 42, 742.

- VIAZIS, S., AKHTAR, M., FEIRTAG, J. & DIEZ-GONZALEZ, F. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157: H7 viability on hard surfaces by treatment with a bacteriophage mixture. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2011, 145, 37–42.

- VIAZIS, S. & DIEZ-GONZALEZ, F. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli: the twentieth century’s emerging foodborne pathogen: a review. Advances in Agronomy 2011, 111, 1–50.

- WANG, J., DOU, X., SONG, J., LYU, Y., ZHU, X., XU, L., LI, W. & SHAN, A. Antimicrobial peptides: Promising alternatives in the post feeding antibiotic era. Medicinal Research Reviews 2019, 39, 831–859.

- WEBB, G. P. An overview of dietary supplements and functional foods. Dietary Supplements and Functional Foods 2011, 1–51.

- WENDLANDT, S., FEßLER, A. T., MONECKE, S., EHRICHT, R., SCHWARZ, S. & KADLEC, K. The diversity of antimicrobial resistance genes among staphylococci of animal origin. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2013, 303, 338–349.

- WHO. 1991. Programme on Traditional Medicine. Guidelines for the assessment of herbal medicines. World Health Organization. [Online]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/58865 [Accessed December 26, 2022].

- WHO. 2013. WHO traditional medicine strategy 2014–2023. Altern Integr Med: 1-78 [Online]. Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en/ [Accessed December 26, 2022].

- WHO 2015. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- WHO. 2022. The fight against Antimicrobial Resistance is closely linked to the Sustainable Development Goals. [Online]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/337519/WHO-EURO-2020-1634-41385-56394-eng.pdf [Accessed December 26, 2022].

- WIMLEY, W. C. Describing the mechanism of antimicrobial peptide action with the interfacial activity model. ACS Chemical Biology 2010, 5, 905–917. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WU, J., HU, Y., DU, C., PIAO, J., YANG, L. & YANG, X. The effect of recombinant human lactoferrin from the milk of transgenic cows on Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium infection in mice. Food & Function 2016, 7, 308–314.

- WU, M., MAIER, E., BENZ, R. & HANCOCK, R. E. Mechanism of interaction of different classes of cationic antimicrobial peptides with planar bilayers and with the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 7235–7242.

- WU, N., DAI, J., GUO, M., LI, J., ZHOU, X., LI, F., GAO, Y., QU, H., LU, H. & JIN, J. Pre-optimized phage therapy on secondary Acinetobacter baumannii infection in four critical COVID-19 patients. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2021, 10, 612–618.

- WU, W.-H., DI, R. & MATTHEWS, K. R. Activity of the plant-derived peptide Ib-AMP1 and the control of enteric foodborne pathogens. Food Control 2013, 33, 142–147.

- XIN, Q., SHAH, H., NAWAZ, A., XIE, W., AKRAM, M. Z., BATOOL, A., TIAN, L., JAN, S. U., BODDULA, R. & GUO, B. Antibacterial carbon-based nanomaterials. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1804838.

- XU, L., ZHAO, X.-Y., WU, Y.-L. & ZHANG, W. The study on biological and pharmacological activity of coumarins. 2015 Asia-Pacific Energy Equipment Engineering Research Conference, 2015. Atlantis Press, 135-138.

- YARNELL, E. Botanical medicines for the urinary tract. World Journal of Urology 2002, 20, 285–293. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- YASIR, M., WILLCOX, M. D. P. & DUTTA, D. Action of antimicrobial peptides against bacterial biofilms. Materials 2018, 11, 2468.

- YEAMAN, M. R. & YOUNT, N. Y. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacological Reviews 2003, 55, 27–55.

- YEON, K.-M., YOU, J., ADHIKARI, M. D., HONG, S.-G., LEE, I., KIM, H. S., KIM, L. N., NAM, J., KWON, S.-J. & KIM, M. I. Enzyme-immobilized chitosan nanoparticles as environmentally friendly and highly effective antimicrobial agents. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2477–2485.

- ZAWISTOWSKA-ROJEK, A., ZAREBA, T., MRÓWKA, A. & TYSKI, S. Assessment of the microbiological status of probiotic products. Polish Journal of Microbiology 2016, 65, 97–104.

- ZHARKOVA, M. S., ORLOV, D. S., GOLUBEVA, O. Y., CHAKCHIR, O. B., ELISEEV, I. E., GRINCHUK, T. M. & SHAMOVA, O. V. Application of antimicrobial peptides of the innate immune system in combination with conventional antibiotics—a novel way to combat antibiotic resistance? Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2019, 9, 128.

| Antibiotic family | Mode of action | Mechanism of resistance | Reference |

| β-lactams β-lactamase inhibitors Fluoroquinolones Macrolides, Lincosamides and Streptogamin (MLS) Aminoglycosides Tetracycline Sulfonamides (Folate pathway inhibitors) |

Cell wall synthesis inhibitors. Binds trans peptidase also known as penicillin binding proteins (PBPs) that help form peptidoglycan Inactivates the enzyme; beta-lactamase Hydrolysis of the beta-lactam ring Binds DNA-gyrase or topoisomerase II and topoisomerase IV; enzymes needed for supercoiling, replication and separation of circular bacterial DNA. Binds the bacterial 50S ribosomal subunits; inhibit protein synthesis Bind to the bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit thus inhibit bacterial protein synthesis Bind reversibly to the 30S ribosomal subunit as such blocks the binding of the aminoacyl-tRNA to the acceptor site on the mRNA-ribosome complex Inhibit the bacterial enzyme dihydropteroate synthetase (DPS) in the folic acid pathway, thereby blocking bacterial nucleic acid synthesis |

Beta-lactamase production primarily - bla genes Expression of alternative PBPs Production of extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) Target modification Decreased membrane permeability Efflux pumps Target site modification Active drug efflux Target site modification (via the action of 16S rRNA methyltransferases (RMTs)) Enzymatic Drug Modification (adenylation, acetylation and phosphorylation), Efflux systems Efflux systems, Target modification, Inactivating enzymes, Ribosomal protection Excessive bacterial production of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) Reduction in the ability of the drug to penetrate the bacterial cell wall Production of altered forms of the dihydropteroate synthetase (DPS) enzyme with a lower affinity for sulfonamides Hyperproduction of para-amino benzoic acid (PABA), which overcomes the competitive substitution of the sulfonamides |

(Dowling et al., 2017, Tooke et al., 2019, Ibrahim et al., 2019) (Correia et al., 2017) (Patel and Hashmi, 2021) (Wendlandt et al., 2013) (Nguyen et al., 2014, Shin et al., 2015) (Davis, 2018, Jiang et al., 2019) |

| Phages | Sample | Technique | Outcome | Reference |

| BEC8 cocktail (38, 39, 41, CEV2, AR1, 42, ECA1, and ECB7) A cocktail composed by the phages e11/2 and e4/1c BEC8 cocktail Cocktail compose by phages DT1 to DT6 FAHEc1 phiEco1, phiEco2, phiEco3, phiEco5, phiEco6 and phiS1 Phages phiJLA23, phiKP26, phiC119 and phiE142 AKH-2 PVS-1, and PVS-2, PVS-3 HN48 |

Spinach leaves and romaine lettuce Cattle hide Sterilized hard surfaces (stainless steel chips, ceramic tile chips, and high density polyethylene chips - HDPEC). Milk and meat UHT milk; Ready-to-eat meat; Raw beef Oyster Tomatoes Misgurnus anguillicaudatus Apostichopus japonicas (Sea cucumber) Oreochromis niloticus (Nile tilapia) |

Following a one-hour drying period in a biosafety enclosure, the leaves were spot-inoculated with bacteria. On top of the previously inoculated leaf, BEC8, Trans-cinnamaldehyde, or TSB was administered. Without dehydrating the bacterial inoculum, positive controls were generated by combining it with BEC8 or TC. The phage cocktail was introduced into the organism using a portable spray container. Negative control: An absence of wash treatment was observed. The semiconductor was spot-treated with bacteria before being dried in a biosafety cabinet. Prior to inoculation, the chip surface was treated with BEC8 or TSB. MOIs of 1, 10, and 100 were utilised. To generate positive controls, the bacterial inoculum was combined with BEC8 or TC without the process of dehydrating Sterile, commercially available milk that had been reconstituted with CaCl2 was used to inoculate one bacterial strain per batch. One portion of each batch was subjected to a phage cocktail, while the other was set aside as a control. 0.4 cm thick, 1 cm2 portions of meat were spot-treated with bacterial strains and left to adhere for 10 minutes at room temperature. Following this, a phage cocktail was introduced into every meat piece. In order to establish controls, TMG buffer was added. Before being applied to food products, phage FAHEc1 was exposed to ultraviolet radiation; phages are capable of lysing bacterial cells, even if they lose viability. Phages and E. coli O157:H7 were utilised to inoculate UHT milk. Inoculating raw beef at 37 °C simulated phage application immediately prior to slathering in carcasses At 37 °C, bacteria that had been grown overnight were introduced to the oysters and allowed to adhere for one hour. After adding phage suspension, the oyster meat was incubated at 3 °C for two days, followed by two hours at 37 °C A mixture of phages comprising 109 PFU/mL of each phage. In addition, microencapsulated phages were generated by combining a polymer mixture comprising 30% phage cocktail, 60% SM Buffer, and 10% solids (modified starch and maltodextrin). The tomato plants were categorised into three groups: the first group received E. coli O157:H7 inoculation, the second group received a microencapsulated cocktail phage inoculated with the bacterial host, and the third group served as a control without any inoculation Loach immersed against Aeromonas hydrophilia Individual phage or cocktail supplementation of the diet to combat Vibrio splendidus Containment of Streptococcus agalactiae by means of phage preparation introduced to the tank |

Cell counts were reduced by both BEC8 and Trans-cinnamaldehyde at the various MOIs and temperatures. The effect of the BEC8 cocktail on both liquid and desiccated cells was identical. An augmentation of the antimicrobial effect was observed upon the combination of both agents. After one hour of application to the cattle hide, phage cocktail demonstrated enhanced efficacy. The degree of bacterial eradication was equivalent to that obtained by washing the sample with water alone, when the sampling was conducted immediately following phage application Phage cocktail exhibited superior performance rating in inactivating the bacterial mixture across a range of conditions, including low to high MOIs, low to high temperatures, and shorter to extended periods of exposure. Both under arid and liquid conditions, bacterial levels could be regulated by phages. Phage-insensitive variants were not identified Phage cocktail could detectably reduce the quantity of various E. coli isolates tested at 4 °C. A decrease in value was observed at higher temperatures (25 and 37 °C), but it persisted only during the initial hours of incubation. Phage cocktails induce greater E. coli reduction in meat at elevated temperatures. A decline in cell count was observed exclusively with an increased phage concentration, encompassing both UV-treated and untreated phages. Untreated phages generally produce superior outcomes in milk. Consistency in observations was maintained for the control in RTE meat. The utilisation of UV-treated phages resulted in a more pronounced reduction of the host in uncooked beef Attenuating all bacterial genotypes is possible with a high concentration of phages. When bacteria are present singly or in combination, a reduction is observed The concentrations of E. coli O157:H7 in tomatoes encapsulated with microencapsulated phages were substantially reduced after 24 hours at 4 °C, in comparison to the control group that did not receive the phage cocktail. The observed differences persisted for a duration of five days. Free phages are less stable in the presence of stress factors than microencapsulated phages. Phage-treated loach exhibited a higher survival rate In contrast to the single phage and control groups, the phage cocktail-treated group exhibited an 82% survival rate 60% greater survival rate than the control group |

Viazis and Diez-Gonzalez, 2011 Coffey et al., 2011 Viazis et al., 2011 Tomat et al., 2018 Hudson et al., 2016 Le et al., 2018 Ramirez et al., 2018 Akmal et al., 2020 Li et al., 2016 Luo et al., 2018 |

| Secondary metabolite (SM) | Characteristics | Sub-category of SM | Uses | References |

|

Phenols |

Probably constitute the largest group of plant SMs, They share the presence of one or more phenol groups as a common feature and range from simple structures with one aromatic ring to highly complex polymeric substances Widespread in plants and contribute significantly to the color, taste and flavor of many herbs, foods and drinks |

Quercetin | Anti-inflammatory | (Goławska et al., 2014, Hussein and El-Anssary, 2019) |

| Flavonoids | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects, anti-tumor | (Montanher et al., 2007, Serafin et al., 2009) | ||

| Gallic acid, Phenol | Antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, anti-anaphylactic, antiseptic, anti-mutagenic, choleretic and bronchodilatory actions | (Pelczar et al., 1988, Yarnell, 2002, Spiller et al., 2008) | ||

| Tannin | Anti-diarrhea, antidote, antiseptic | (Jepson et al., 2013) | ||

| Coumarin | Anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, anticancer and anti-Alzheimer’s | (Xu et al., 2015) | ||

|

Alkaloids |

Organic compounds with at least one nitrogen atom in a heterocyclic ring. Except for the fact that they are all nitrogen-containing compounds, no general definition fits all alkaloids. Many are toxic to animals to cause death if eaten |

Aromatics, Carbolines, Ergots, Imidazoles, Pyridines, Purines, Quinolines, Piperidines, etc. |

Analgesia, local anesthesia, cardiac stimulation, respiratory stimulation and relaxation, vasoconstriction muscle relaxation and toxicity, as well as antineoplastic, hypertensive and hypotensive properties. antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral |

(Seigler, 1998, Hoffmann, 2003, Hussein and El-Anssary, 2019) |

|

Saponins |

This hydrophobic-hydrophilic asymmetry means that these compounds have the ability to lower surface tension and are soap-like. They form foam in aqueous solutions and cause hemolysis of blood erythrocytes in vitro. |

Pentoses, Hexoses, or Uronic acids |

Antitumor, piscicidal, molluscicidal, spermicidal, sedative, expectorant, anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. | Rehab 2018 (Hussein and El-Anssary, 2019) |

|

Terpenes |

Most diverse group of plant SMs All forms are derived chemically from 5-carbon isoprene units assembled in different ways Classified according to the number of isoprene units in the molecule |

Monoterpenes, Sesquiterpenes, Sesterterpenes, Hemiterpenes, Diterpenes Triterpenes |

Anti-hemorrhagic, analgesic, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antineoplastic and antiprotozoal activities, anti-rheumatics |

(Hoffmann, 2003, Culioli et al., 2003) |

|

Lipids |

Major structural components of all biological membranes Source of energy reservoirs and fuel for cellular activities in addition to being vitamins and hormones Although lipids are primary metabolites, recent studies revealed pharmacological activities to members of this class of SMs |

Fixed oils, Waxes, Essential oils, Sterols, Fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), Phospholipids and others |

Anti-inflammatory, anti-aging, wound healing activities, antiseptic, antimicrobial, analgesic, sedative, spasmolytic and locally anesthetic remedies. They are also used as fragrances in embalmment, as sunscreens, moisturizer and in food preservation |

(Masotti et al., 2003, Fahy et al., 2009, Subramaniam et al., 2011) |

|

Carbohydrates |

Starter for all SMs and animal biochemical. Although carbohydrates are primary metabolites, they are incorporated in plenty of SMs through glycosidation linkages. Polymers of simple sugars and uronic acids produce mucilage and gums |

Monosaccharides, Disaccharides, Oligosaccharides and Polysaccharides | Demulcent, emollient |

(Asif et al., 2011, Anbalahan, 2017) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).