INTRODUCTION:

The movement disease known as diabetic striatopathy (DS) is characterised by hemiballismus-hemichorea (HBHC) as a result of nonketotic hyperglycemia [

1]. This illness encompasses problems linked to striatal pathology (putamen, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus), endocrinopathy (diabetes), and neurological movement disorders similar to hemichorea-hemiballismus [

2]. Particularly in an emergency situation, the significant hyperintensity on imaging modalities like brain CT and T1-weighted MRI might mislead the physician to a mistake of ischemic infarction or cerebral haemorrhage.

The current study defines diabetic striatopathy (DS) as a hyperglycemic state linked to one or both of the subsequent two conditions: (1) chorea/ballism; (2) as previously described, striatal hyperintensity on T1-weighted MRI or hyperdensity on CT [

3]. The sites of neuroimaging abnormalities in the basal ganglia were described using three anatomical regions: the putamen, the globus pallidus, and the caudate nucleus [

4].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION:

The case of a 64-year-old woman is being reported here with poorly controlled Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertension, admitted to the Internal Medicine ward for sudden onset of altered sensorium along with complaints of non-bilious, non-projectile vomiting.

The patient was a known case of Diabetes Mellitus sand Hypertension since 1996, Hypothyroidism since 2016. She had also suffered from ischemic heart disease in 1990 and had a history of Tourette syndrome. She had undergone an operation for Bilateral cataract 6 months ago. She was admitted with the present conditions of Septic Encephalopathy and Septic Acute Kidney injury.

GENERAL EXAMINATION:

On physical examination patient was well oriented to time, place and person during the examination. She was of average built and nutrition was adequate, and there was no evidence of clubbing, cyanosis, icterus, pallor, lymphadenopathy, edema. Her Vitals were within normal range with pulse at 85/- minute, Blood Pressure 110/70 mmHg and respiratory rate at 16 breaths per minute.

Her speech appeared somewhat forced, but it was adequate with proper volume and rhythm. She lacked nystagmus and had normal eye movements in all directions due to her undamaged extraocular muscles. Pupils were reactive to light with normal accommodation. The cranial nerve testing was normal throughout. Both the lower and upper extremities retained their motor strength. When coordination examination with left finger-to-nose test and left heel-to-shin test was done, target was reached. Throughout, the patient's deep tendon reflexes were sufficient. There was no Romberg sign. Extensor plantar responses were also absent.

LAB INVESTIGATIONS:

The patient’s glucose level was 300 mg/dL (normal range: 70- 115 mg/dL), and her haemoglobin A1C was 10 (normal range: 3.8-5.6%). The basic metabolic panel was otherwise normal with Haemoglobin at 9.6 g/dL, Total leukocyte count at 6223 103/mm3 and platelets at 430 per mm3.

IMAGING AND INSTRUMENTAL EXAMINATIONS:

Initially, the patient had undergone USG Abdomen and CT Thorax. The findings of these scans came out to be normal. Then the patient underwent CT scan and MRI of the brain, whose findings are mentioned below.

CT SCAN OF BRAIN (PLAIN):

Spiral volume scanning of brain was performed without contrast. Age related cerebral and cerebellar cortical atrophy was noted.

Abnormal confluent and patchy areas of hypodensities were noted in the bilateral periventricular deep white matter of both cerebral hemispheres, suggestive of chronic small vessel ischaemic changes. Brainstem and 4thventricle were normal. No space occupying lesion was seen. 3rd ventricles appeared normal. No midline shift was noted. No evidence of subdural, extradural or intraparenchymal haemorrhage was noted. Bony skull vault appeared normal. Mucosal thickening was noted in bilateral ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses. Calcified atheromatous changes were noted in cavernous, clinoid and supra-clinoid segments of bilateral internal carotid arteries and V4 segment of both vertebral arteries.

Afterwards, the patient had undergone Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

MRI BRAIN PLAIN:

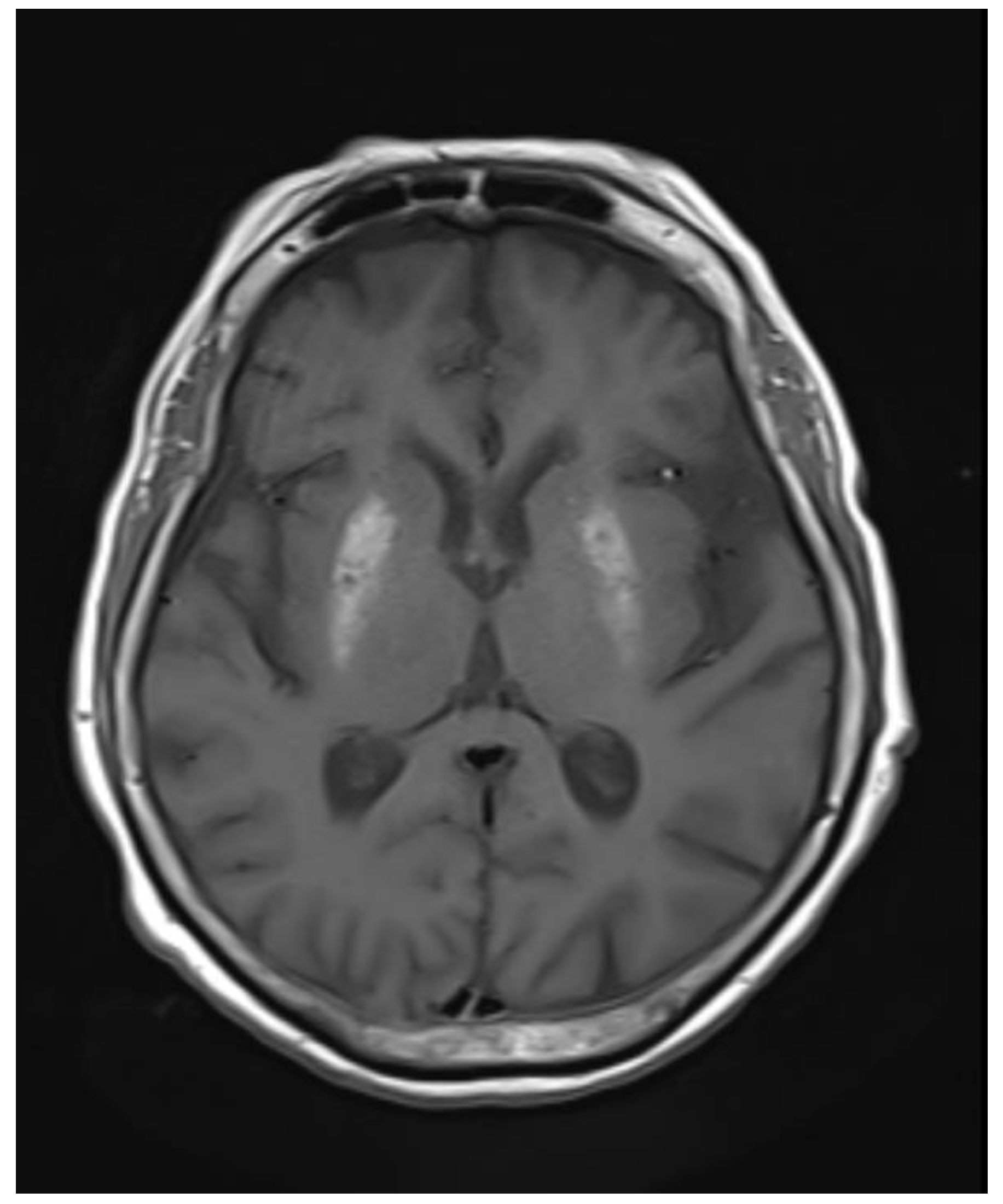

Abnormal symmetrical T1WI hyperintensity was noted in bilateral putamen. Subtle areas of GRE blooming were visible. Dilatation of ventricular system, cerebral sulci, basal cisterns and cerebellar folia were visible which suggested cerebral and cerebellar atrophy. Few discrete T2WI and FLAIR hyperintensities were noted in bilateral periventricular deep white matter in fronto-parietal region, which were suggestive of chronic ischemic changes

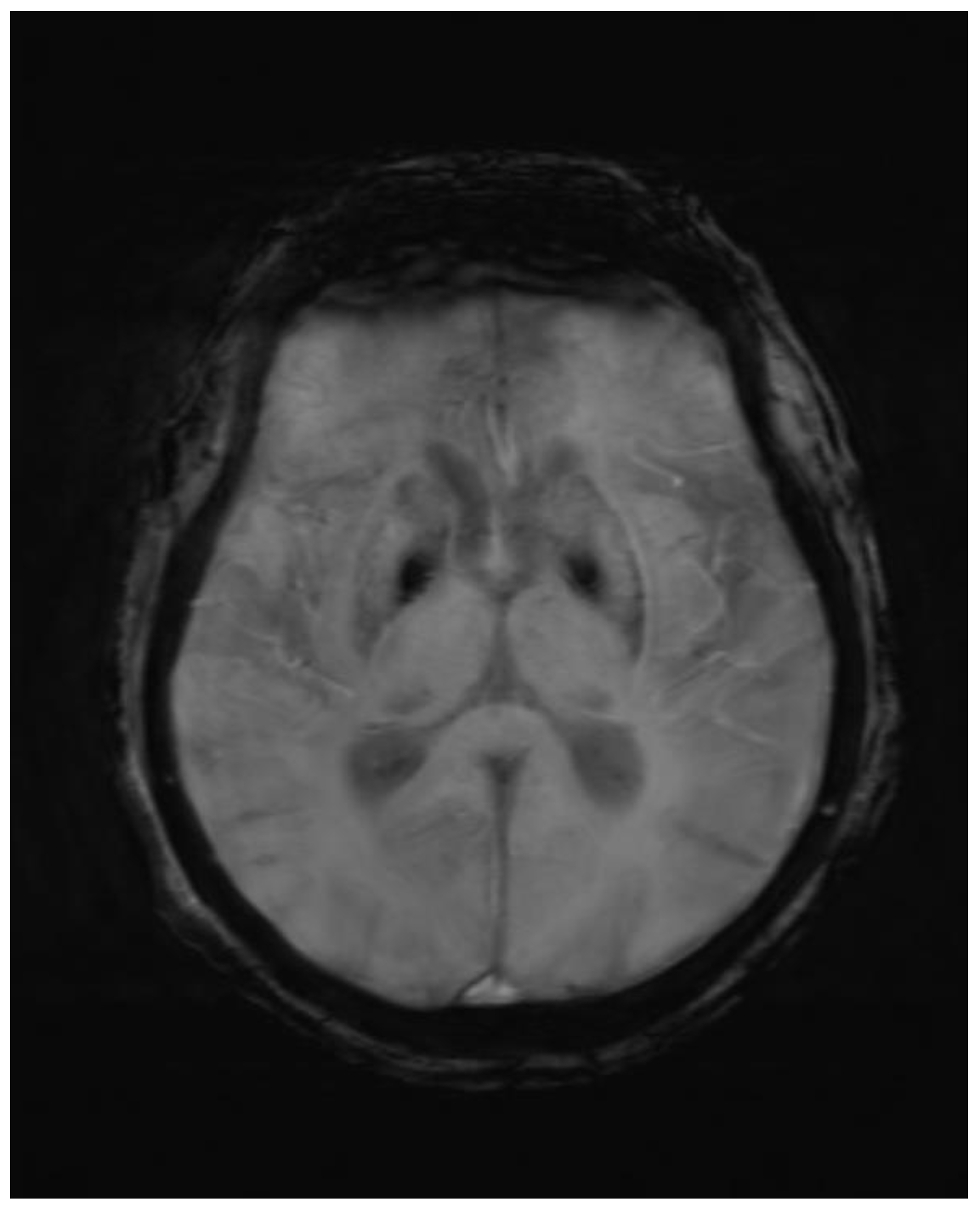

Figure 1.

Axial GRE image showing blooming in corresponding T1 hyperintense area.

Figure 1.

Axial GRE image showing blooming in corresponding T1 hyperintense area.

Figure 2.

Axial T1wi sequence showing bilateral symmetrical hyperintensity in putamen.

Figure 2.

Axial T1wi sequence showing bilateral symmetrical hyperintensity in putamen.

THERAPEUTIC APPROACH

Adequate hydration and management of hyperglycemia was the mainstay of therapy for DS in this patient. She was also kept on medication consisting of anti-chorea drugs. There are four main classes of anti-chorea medications, namely antipsychotics, GABA-receptor agonists, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and dopamine-depleting agents. This patient was given Haloperidol as the main anti chorea drug. 2nd line therapy includes tetrabenazine, risperidone and clonazepam. Combined regimens have also proven to be beneficial in treating chorea associated with diabetic striatopathy.

DISCUSSION

Diabetic Striatopathy is a disease caused by severe uncontrolled hyperglycemia [

5]. Numerous neurological problems, including encephalopathy, movement difficulties, and seizures, are among its clinical symptoms [

6]. In more than 90% of individuals with diabetic striatopathy, chorea or ballismus is unilateral [

7]. Neuroimaging demonstrates abnormalities in the striatum. Diabetic Striatopathy is characterised by involvement of the striatum in neuroimaging, with the putamen being the most frequently observed structure, followed by the globus pallidus, caudate nucleus, and internal capsule sparing [

8]. Putamen involvement alone is more frequent than putamen and caudate nucleus involvement combined.

Diabetic striatopathy is more plausible because of the acute nature of the symptoms and the lack of fever, which help rule out neurogenetic and viral causes. By taking into consideration the causes of striatal T1 hyperintensity on brain MRI, the list of differential diagnoses can be further reduced. The biophysics of T1-weighted MRI sequences states that melanin [

9], fat, slow-moving blood flow, high protein content, methemoglobin in subacute haemorrhage, and paramagnetic transition metals with unpaired electrons, such as manganese, iron, zinc, and copper, can all cause T1-shortening, that results in hyperintensities. Some of these causes of T1-hyperintensity can be ruled out by looking at the clinical manifestations of DS. Iron and copper should be ruled out since they can lead to chronic illnesses that develop slowly. Since manganese induces Parkinsonism [

10], it can be eliminated. On susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sequences, early subacute blood on an MRI brain exhibits hypodensities, but late subacute blood exhibits hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences [

11]. A DWI sequence with high signal intensity and an ADC sequence with low signal intensity would indicate an ischemic infarct. Fat can be easily be eliminated on fat-suppression images. Despite its electron pairs, calcium is paramagnetic because it is a metal [

12]; Although dark on both SWI and gradient-recalled echo (GRE) sequences, it is bright on phase-filtered SWI sequences.

It is hypothesised that the pathophysiology of the disease results from a switch in brain metabolism in Non Ketotic Hyperglycemia from the Krebs cycle to an alternative anaerobic pathway [

13]. This switch causes the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid to be depleted to succinic acid, which in turn causes the globus pallidus to disinhibit the thalamus [

14]. The precise workings of DS remain poorly understood. According to biopsies, the lesion is a striatal-limited gliosis vasculopathy. Reactive astrocytosis, patchy ischemia necrosis, petechial haemorrhage, vascular proliferation, and arteriolar alterations like those of diabetic proliferative retinopathy are among the rather variable postmortem findings.

CONCLUSION:

When elderly people exhibit dystonia, chorea, or ballism, DS should be taken into consideration and the aberrant movements should be treated correctly. According to reports, the prevalence of diabetic striatopathy is 1 in 100,000. However, this number is likely underestimated because most doctors are unaware of the disorder, which might cause it to be mistakenly diagnosed as a common intracerebral haemorrhage. Physicians and the general public need to be aware of this condition because, in addition to severely limiting the daily functioning of those who suffer from it, the absence of established treatment guidelines may result in potentially fatal complications. An proper diagnosis can be made with thorough and deliberate analysis, saving the patient needless suffering.

Ethical Statement

Being a case report study, there were no ethical issues and the IRB was notified about the topic and the case. Still, no formal permission was required as this was a record-based case report. Permission from the patient for the article has been acquired and ensured that their information or identity is not disclosed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding and Sponsorship

None of the authors are financially interested in any of the products, devices or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

References

- C.-B. Chua, C.-K. Sun, C.-W. Hsu, Y.-C. Tai, C.-Y. Liang, and I.-T. Tsai, “‘Diabetic striatopathy’: clinical presentations, controversy, pathogenesis, treatments, and outcomes,” Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1594, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Rocha Cabrero and O. De Jesus, Hemiballismus. 2023.

- A. Arecco, S. Ottaviani, M. Boschetti, P. Renzetti, and L. Marinelli, “Diabetic striatopathy: an updated overview of current knowledge and future perspectives,” J Endocrinol Invest, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghandili and S. Munakomi, Neuroanatomy, Putamen. 2023.

- O. Y. Alkhaja, A. Alsetrawi, T. AlTaei, and M. Taleb, “Diabetic striatopathy unusual presentation with ischemic stroke—A case report and literature review,” Radiol Case Rep, vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 2297–2302, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C.-B. Chua, C.-K. Sun, C.-W. Hsu, Y.-C. Tai, C.-Y. Liang, and I.-T. Tsai, “‘Diabetic striatopathy’: clinical presentations, controversy, pathogenesis, treatments, and outcomes,” Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1594, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Dong, J.-Y. E, L. Zhang, W. Teng, and L. Tian, “Non-ketotic Hyperglycemia Chorea-Ballismus and Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Case Report and Literature Review,” Front Neurosci, vol. 15, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C.-B. Chua, C.-K. Sun, C.-W. Hsu, Y.-C. Tai, C.-Y. Liang, and I.-T. Tsai, “‘Diabetic striatopathy’: clinical presentations, controversy, pathogenesis, treatments, and outcomes,” Sci Rep, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1594, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Sąsiadek, “Intracranial lesions with high signal intensity on T1-weighted MR images – review of pathologies,” Pol J Radiol, vol. 78, no. 4, pp. 36–46, 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. R. Guilarte, “Manganese and Parkinson’s Disease: A Critical Review and New Findings,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 118, no. 8, pp. 1071–1080, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Eastwood, S. T. Engelter, J. F. MacFall, D. M. Delong, and J. M. Provenzale, “Quantitative assessment of the time course of infarct signal intensity on diffusion-weighted images.,” AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 680–7, Apr. 2003.

- Q. Miao, C. Nitsche, H. Orton, M. Overhand, G. Otting, and M. Ubbink, “Paramagnetic Chemical Probes for Studying Biological Macromolecules,” Chem Rev, vol. 122, no. 10, pp. 9571–9642, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Chatterjee, R. Ghosh, and S. Dubey, Diabetic Striatopathy. 2000.

- A. Arecco, S. Ottaviani, M. Boschetti, P. Renzetti, and L. Marinelli, “Diabetic striatopathy: an updated overview of current knowledge and future perspectives,” J Endocrinol Invest, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).