1. Introduction

Ostrich oil is derived from the adipose tissues of the ostrich bird (

Struthio camelus). The process that converts these adipose tissues into high-quality crude oil is known as low-temperature wet rendering [

1,

2,

3]. The quality of the oil depends on the temperature and duration of the heating process [

3]. Ostrich oil primarily consists of triglycerides and essential fatty acids, particularly α-linolenic acid (omega-3), linoleic acid (omega-6), and oleic acid (omega-9) [

4,

5]. It has been discovered that these essential fatty acids prevent cardiovascular disease and regulate brain and nervous system function [

6]. Omega-3 and omega-6 assume pivotal roles in human health across all life stages, including developmental, maturation, and aging phases [

7]. Additionally, the antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory activities of ostrich oil appear to be attributed to minor components such as carotenoids, tocopherol, and flavones [

8]. Conventionally employed in traditional medicine, ostrich oil has exhibited anti-inflammatory characteristics that are advantageous in the treatment of ailments including contact dermatitis and eczema. Eltom et al. [

9] reported that the application of the isolated topical γ-lactone (5-hexyl-3H-furan-2-one) derived from ostrich oil significantly mitigated the paw edema induced by formalin in rodents. In addition, it was observed that the nano-emulsion comprising 1% w/w ostrich oil demonstrated more pronounced anti-inflammatory effects in rodent models of carrageenan-induced inflammation than ostrich oil in its pure form [

10]. Wound healing applications have made use of ostrich oil, which is recognized for its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties [

11]. A study was conducted to assess the prospective wound healing effectiveness of an ointment containing 2% w/w ostrich oil on mice that had excisional wounds infected with

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Staphylococcus aureus. In contrast to the ointment base, the ointments containing 2% w/w ostrich oil exhibited a diminished bacterial count and stimulated the process of wound healing through the mitigation of inflammation, promotion of fibroblast proliferation, and enhancement of collagen deposition [

12].

However, ostrich oil faces a significant challenge due to its susceptibility to oxidative and hydrolytic rancidity, leading to undesirable odors and colors [

13]. To enhance the stability of ostrich oil, innovative oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions have been developed. These emulsions provide several advantages, such as reducing the perception of greasiness and minimizing the occurrence of oil rancidity. The role of emulsifiers is pivotal, as they create a protective film around oil droplets, effectively shielding them from the detrimental effects of oxygen and light exposure [

14]. Additionally, prior studies have predominantly focused on topical preparations containing only 1-2% w/w ostrich oil [

10,

12]. Thus, the development of emulsion formulations with high concentrations of ostrich oil poses an intriguing challenge.

The formation of oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions relies on emulsifiers that adsorb to the oil-water interface during homogenization, effectively reducing surface tension and preventing undesirable flocculation and coalescence of oil droplets through steric or electrostatic repulsions [

15]. Tweens and Spans, belonging to classes of surfactants, are frequently employed together to establish stable emulsions. Tweens possess hydrophilic properties, while Spans exhibit lipophilic characteristics. Their synergistic application ensures comprehensive coverage of both emulsion phases, contributing to overall stability. The emulsifiers' amphiphilic nature, combined with their ability to diminish interfacial tension, form micelles, prevent coalescence, and enhance dispersion, plays a crucial role in the effective creation and maintenance of stable emulsions [

14].

The objectives of this study were to assess the feasibility of producing an O/W emulsion with a high concentration of ostrich oil, intended to highlight antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. The anticipated benefits cover a diverse range of effects, including antioxidant, anti-scratch, and protective properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All reagents utilized in the experiments were of analytical reagent (AR) and American Chemical Society (ACS) grade. Methyl heptadecanoate and all fatty acid GC standards were procured from Nu-Chek Prep, Inc., Minnesota, USA. The ICP multi-element standard solution XIII was acquired from Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA. Purchased from St. Louis, Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), and Wijs solution. The reference standard, diclofenac diethylamine, was purchased from the Bureau of Drug and Narcotic, Department of Medical Sciences (DMSC), Ministry of Public Health (Nonthaburi, Thailand). Purchases were made of Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA), Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), and Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA), Becton, Dickinson and Company (Sparks, Maryland, USA), and HiMedia Laboratories Private Limited (Mumbai, Maharashtra, India), respectively. Lincomycin was bought from T.P. Drug Laboratories (1969) Co., Ltd. (Phra Khanong, Bangkok, Thailand). Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany supplied the Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Media (IMDM) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT).

2.2. Preparation and Evaluation of Ostrich Oil

2.2.1. Preparation of Ostrich Oil

Siam Ostrich Farm, located in the Song Phi Nong district of Suphan Buri Province, Thailand, provided ostrich frozen abdominal fat. After thawing the ostrich fat samples at room temperature, adherent tissues were removed, the samples were meticulously rinsed with distilled water, and any remaining surface moisture on the fat tissues was absorbed by tissue papers to remove excess water. Following that, the fat was further chopped into a smooth paste after being reduced to tiny pieces. The rendering method was employed to extricate the paste at a temperature of 50 °C until the fat had fully melted. Subsequent to reaching ambient temperature, the transparent oil was cooled and stored in nitrogen-filled amber glass vials at 4 °C. This precautionary step was taken to prevent oxidation and photodegradation before utilization in the formulation process.

2.2.2. Fatty Acid Composition

As previously reported, fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were produced using a one-step extraction and direct transesterification process between fatty acids and methanol at 90 °C for 30 min [

1]. The solution of FAMEs was promptly analyzed using gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID) and an automated liquid sampler (Model 6890N Network GC System, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). Methyl heptadecanoate was used as an internal standard.

2.2.3. Antioxidant Activity

The DPPH radical scavenging and lipid peroxidation inhibitory activities were done in line with our previous studies [

1,

16]. The absorbance of the reaction solution was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, Hitachi U-2900 (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), set to 500 nm. Trolox was the standard antioxidant.

2.2.4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

By inhibiting the heat-induced denature of egg albumin, anti-inflammatory activity was assessed. The procedure outlined by Limmatvapirat et al. [

17] underwent slight modifications. The reference drug was diclofenac diethylamine.

2.2.5. Acid value (AV) and peroxide value (PV)

AV and PV were evaluated using a potentiometric auto-titrator, Titrino Plus 848 (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland), in accordance with the American Oil Chemists' Society (AOCS) official procedures Cd 3d63 [

18] and Cd 8b-90 [

19].

2.2.6. Heavy Metal Contents

The concentrations of heavy metals were determined using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (7500 ce (Agilent Technologies, California, USA), per our previous report [

20].

2.2.7. Microbial Contamination

The total aerobic microbial count (TAMC), the total combined yeast and mold count (TYMC), and the individual results of

Staphylococcus aureus,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Clostridium spp., and

Candida albicans in samples were analyzed to determine the microbial contamination. All sample enumeration tests were conducted in accordance with the United States Pharmacopoeia 43 and National Formulary 38 [

21].

2.3. Formulation and Evaluation of Emulsion Containing Ostrich Oil

2.3.1. Formulation of O/W Emulsion

Hydrophile-lipophile balance (HLB) is the equilibrium between the size and intensity of a emulsifier molecule's hydrophilic and lipophilic moieties. The range of the HLB scale is 0 to 20. Those with lower HLB values are more oil-soluble (lipophilic emulsifiers), whereas those with higher values are more water-soluble (hydrophilic emulsifiers) [

22]. As depicted in

Table 1, O/W emulsions were formulated with 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5% w/w emulsifiers. The emulsifiers, a blend of sorbitan monooleate (Span 80, HLB 4.3) and polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monooleate (Tween 80, HLB 15.0), were used in various ratios calculated based on the total emulsifier content. To ascertain the HLB values, the emulsions were prepared using the beaker method, which was slightly modified from the previous procedure [

23,

24]. Tween 80 was dissolved in the aqueous phase, while Span 80 was dissolved in the oil phase. At 65 °C and 62 °C, the aqueous phase and the oil phase were heated, respectively. Slowly pouring the oil phase into the water phase, this emulsion was then homogenized at 3,800 rpm for 5 min using a T25 digital Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (IKA, Baden-Württemberg, Germany). Further evaluation was conducted on the physicochemical properties of all emulsions with HLB values between 4.3 and 8.0.

The homogenization speed in the preparation of the O/W emulsion is a crucial parameter with a significant impact on the emulsion's characteristics. The selection of homogenization speed is grounded in theoretical principles supporting the notion that higher speeds can yield smaller emulsion droplets. Smaller droplets enhance stability by providing a larger interfacial area for emulsifiers to act upon. Elevated homogenization speeds generate more intense shear forces, breaking down larger oil droplets into smaller ones. This reduction in droplet size contributes to improved stability by preventing coalescence and promoting homogeneity in the system [

25]. However, the homogenization speed must be carefully balanced with other factors, including the type and concentration of emulsifiers, the nature of the oil phase, and the desired characteristics of the final emulsion. The choice of 3,800 rpm for the homogenization speed in the preparation of the ostrich oil-based O/W emulsion was determined through preliminary experiments, striking a balance between achieving the desired droplet size for stability and practical considerations, such as equipment limitations.

Utilizing Span and Tween as emulsifiers, ostrich oil emulsions were created. The effects of different emulsifier types, including sorbitan monolaurate (Span 20, HLB 8.6), Span 80 (HLB 4.3), polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monolaurate (Tween 20, HLB 16.7), polyoxyethylene (20) sorbitan monostearate (Tween 60, HLB 14.9), and Tween 80 (HLB 15.0), on the properties of O/W emulsions were comparatively evaluated. Also evaluated were the effects of varying concentrations of combined emulsifiers (Span and Tween) at 5, 10, 15, and 20% w/w. According to the experiment described above, each emulsion was prepared using a particular combination of emulsifiers to achieve the required HLB. The oil phase was produced by adding Span to 20% w/w ostrich oil and stirring the mixture at 62 °C with a magnetic stirrer. The aqueous phase was created by dissolving a specific volume of Tween in distilled water at 65 °C, and then the oil phase was continuously poured into the aqueous phase. This emulsion was homogenized for 5 min at 3,800 rpm with a homogenizer. The obtained emulsions were then evaluated.

2.3.2. Evaluation of Emulsion

By means of visual observation, the physical properties and creaming indices of emulsions were ascertained. The creaming index was calculated utilizing Equation (1), in which S denotes the serum layer's height and T signifies the emulsion's total height.

The size of oil droplets in the emulsion was determined using a laser scattering particle size distribution analyzer model LA950 (Horiba Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). The zeta potential value was measured using a ZetaPlus zeta potential analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, New York, USA). A Brookfield DV-III Ultra Programmable rheometer, model RVDV-III Ultra (Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Inc., Massachusetts, USA), equipped with a CPE-51 or CPE-40 spindle, was utilized to determine the viscosity at a temperature of 25 °C. The morphology of oil droplets was examined using an Olympus CX41RF optical microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3.3. Stability Test

Samples from the optimized emulsion, consisting of 20% w/w ostrich oil, 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 20 and Tween 80), both with and without 0.01% w/w butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), underwent evaluation for AV, PV, phase separation, and microbial contamination. These stability assessments were conducted using amber vials sealed with hermetically sealed lids, shielded from light, and maintained at temperatures of 4 ± 0.5 °C, room temperature (25 ± 0.5 °C), and 45 ± 0.5 °C. The analysis intervals included the initial, 1st, 3rd, and 6th months. Control analyses were performed on the fresh samples (time zero). To mitigate potential variations caused by different storage conditions, all collected emulsion and ostrich oil samples at each time duration were promptly analyzed.

2.3.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

In order to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the optimized formulation on human dermal fibroblasts, ATCC

® CRL-2076 (Manassas, Virginia, USA), the MTT colorimetric assay [

26] was utilized. To attain the intended concentration range, IMDM was utilized to appropriately dilute each sample. In a 96-microwell plate, cells were inoculated at a density of 1 × 10

4 cells/well and cultured until they achieved a confluency of 80-90%. The cells were subsequently exposed to 100 μl of sample-containing media at 37 °C in an incubator containing 5% CO

2 for 24 h. After adding 10 µl of a 5 mg/ml MTT solution to each well, the mixture was incubated for an additional 2 h. Following the removal of the supernatant, 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were introduced in order to solubilize the formazan products generated by viable cell mitochondria. The absorbance at 550 nm was determined using a Fusion universal microplate analyzer (Model A153601, Packard BioScience Company, Connecticut, USA). In comparison to untreated controls, the percentages of viable cells were calculated.

2.3.5. Antibacterial Assay

The antibacterial activity of the optimized emulsion was evaluated using the agar disc diffusion technique against three bacterial strains:

S. aureus ATCC 6538P,

Escherichia coli DMST 4212, and

P. aeruginosa ATCC 9027 [

27]. A total of 1.5 x 10

8 colony forming units (CFU)/ml of each test strain was inoculated onto MHA plates, which were then left to dry. A volume of 30 µl of the emulsion sample was added to sterile paper discs, each with a diameter of 6 mm. Subsequently, the saturated paper discs were dispensed onto the inoculated agar plate. Following the incubation of the plates at 37 °C for 18-24 h, inhibitory zones (including the 6 mm disc diameter) were determined. To determine whether the emulsion sample was as potent as the commercial antibacterial lincomycin, a parallel analysis study was performed with it at 30 µg/disc. A control emulsion containing a placebo was utilized. Each and every test was performed in triplicate.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using the t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (version 16 of the SPSS program) on measurements performed in triplicate. P-values less than 0.05 were statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and Evaluation of Ostrich Oil

The fatty acid composition of ostrich oil, obtained through the low-temperature rendering method, was analyzed using the GC-FID technique.

Table 2 provides information on the retention time and linearity of FAME standards. Methyl heptadecanoate, serving as an internal standard, exhibited a retention time of 9.1 min. Regression analysis demonstrated correlation coefficients (r

2) for all FAME standards ranging from 0.9998 to 0.9999, signifying a perfect linear relationship. Upon examination of the fatty acid composition, the three most prevalent fatty acids in ostrich oil were oleic acid (omega-9) at 34.60 ± 0.01%, palmitic acid at 28.42 ± 0.05%, and linoleic acid (omega-6) at 27.73 ± 0.01%. Additionally, stearic acid was identified at 5.07 ± 0.05%, α-linolenic acid (omega-3) at 3.02 ± 0.00%, myristic acid at 0.93 ± 0.01%, and lauric acid at 0.23 ± 0.01%.

Ostrich oil is well-regarded for its nutritional value, primarily attributed to its high levels of omega-3, omega-6, and omega-9 fatty acids. This composition positions ostrich oil as a beneficial adjunct therapy for various skin conditions, offering advantages such as moisturizing properties, support for skin barrier function, anti-inflammatory effects, and wound healing capabilities [

28,

29]. Furthermore, palmitic acid has been identified for its antibacterial properties [

30], while stearic acid exhibits anti-inflammatory properties for the skin [

31]. As a result, ostrich oil is widely recognized as an excellent source of nutrients that contribute to overall skin health.

In line with the Codex Standard for Named Animal Fats (CODEX STAN 211-1999) established by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) [

32], the ostrich oil exhibited AV and PV of 0.10 ± 0.00 mg KOH/g oil and 2.53 ± 0.12 mEq O

2/kg oil, respectively. These values were well within the allowed limits of 2 mg KOH/g oil and 10 mEq O

2/kg oil. The concentrations of Fe and Cu were measured at 0.803 ± 0.148 mg/kg and 0.002 ± 0.001 mg/kg, respectively. Additionally, As and Pb were not detected, all falling comfortably within the highest allowable concentrations of 1.5 mg/kg for Fe, 0.4 mg/kg for Cu, 0.1 mg/kg for As, and 0.1 mg/kg for Pb. The microbial limit test revealed that neither TAMC nor TYMC were present in the oil sample.

S. aureus,

P. aeruginosa,

Clostridium spp., and

C. albicans contamination in 1 g of any sample was not detected during pathogen investigation. The outcomes indicate that the prepared ostrich oil was of exceptional quality and safe for human use.

Ostrich oil at a high dose (360 mg/ml, the maximal solubility in the test medium) exhibited no anti-inflammatory activity. In a previous report, ostrich oil was found to lack anti-inflammatory activity in 15-day-treated mice at doses of 100 or 500 mg/kg/day [

33]. Additional anti-inflammatory experiments are required to investigate its mechanism and potential efficacy.

The IC50 of DPPH and the percentage of inhibition of linoleic acid oxidation (Day 5) for ostrich oil were 39.92 ± 1.51 mg/ml and 44.70 ± 1.94%, respectively, while those for Trolox were 0.0043 ± 0.0001 mg/ml and 58.20 ± 5.18%, respectively. The maximal percent inhibition of linoleic acid oxidation by ostrich oil and Trolox occurred on Day 5 and lasted until Day 7; 41.12 ± 1.83 and 55.82 ± 2.03%, respectively. Therefore, the results demonstrated that ostrich oil possesses a potent antioxidant activity and a long duration of linoleic acid oxidation inhibition.

Based on the analysis results mentioned earlier, which encompassed the fatty acid profile, antioxidant activity, microbial contamination, and heavy metal contents, it is possible to deduce that the ostrich oil generated via the low-temperature wet rendering method was appropriate for the formulation of an emulsion intended for topical application on the skin.

3.2. Formulation and Evaluation of Emulsion Containing Ostrich Oil

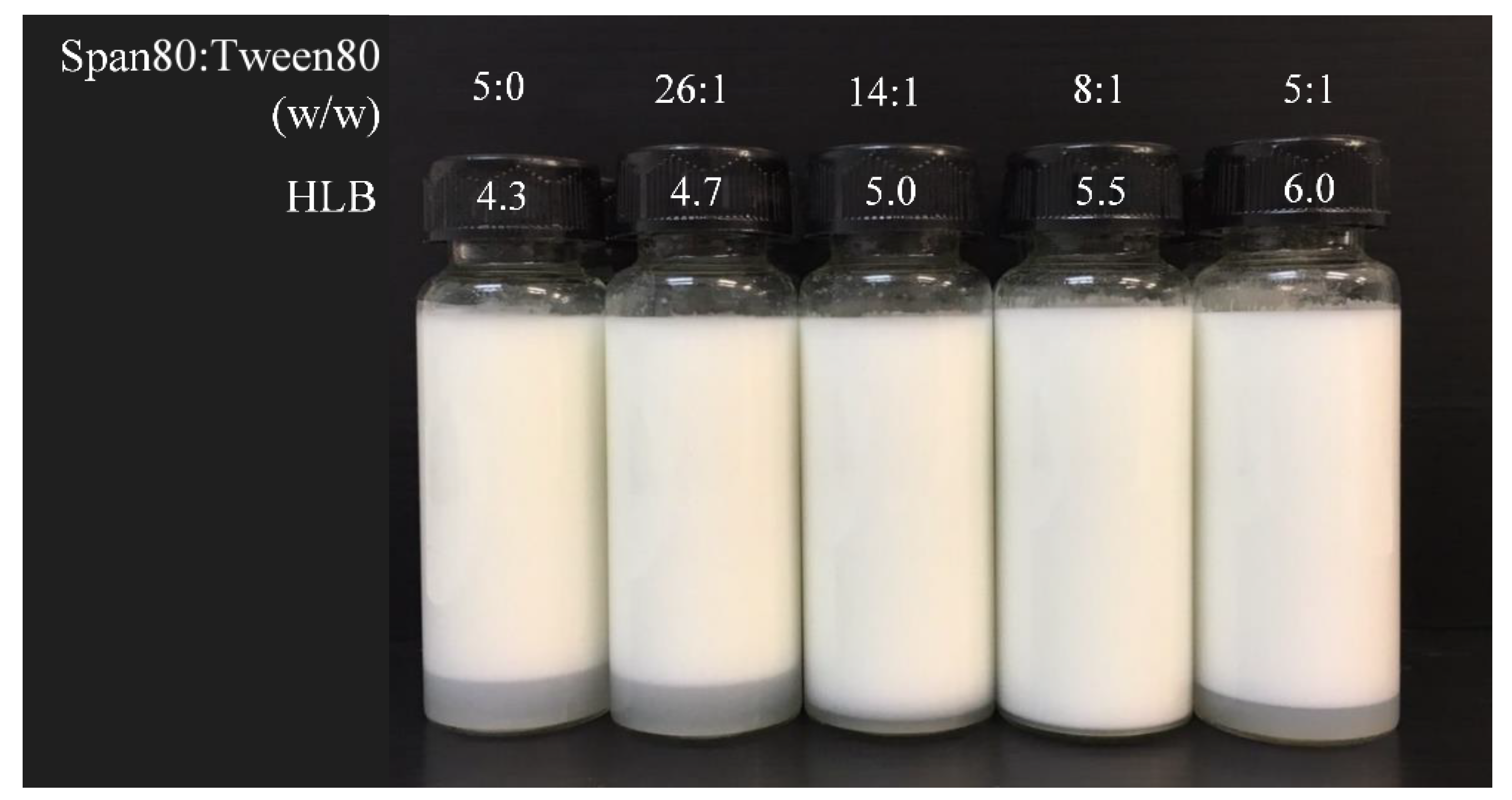

3.2.1. Determination of Required Ostrich Oil HLB

The evaluation of ostrich oil HLB values was conducted using the beaker method to prepare O/W emulsions. These emulsions consisted of 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5% w/w emulsifiers, comprising different ratios of Span 80 and Tween 80, as shown in

Table 1. The stability of all prepared emulsions was assessed by storing them in cylindrical glass vials at room temperature for 24 h, followed by visual observation for any separation between the aqueous and oil phases, as depicted in

Figure 1. The findings revealed that the emulsion with an HLB value of 5.5 displayed the highest stability, showing no phase separation (creaming index of 0.00%) (

Table 1). Based on these results, it can be inferred that the optimal HLB value for ostrich oil is 5.5, indicating that this particular HLB value is essential for achieving the desired emulsion stability.

HLB values are used to characterize the surfactant's balance between hydrophilic (water-attracting) and lipophilic (oil-attracting) properties. For the preparation of O/W emulsions, higher HLB values are generally preferred because they indicate a higher degree of hydrophilicity, making the surfactant more effective at stabilizing water droplets in an oil phase [

34]. The optimal HLB value depends on the specific formulation and the types of oils and emulsifiers used. The exact HLB value will depend on the specific requirements of the formulation, the nature of the oils and other ingredients used, and the desired characteristics of the final product. It's important to note that formulating emulsions involves a combination of emulsifiers and possibly co-emulsifiers to achieve the desired stability and texture. Experimentation may be necessary to find the optimal HLB value for a particular emulsion formulation.

The suitability of a particular HLB value for preparing an O/W emulsion depends on various factors, including the specific properties of the oil and the emulsifiers used. In the case of ostrich oil, it appears that an HLB value of 5.5 is considered appropriate for preparing an O/W emulsion. Ostrich oil is known to contain a mixture of fatty acids, and its composition can influence its behavior in emulsion systems. Emulsifiers are chosen based on their HLB values to achieve stability and proper emulsification of the oil phase in the water phase. An HLB value of 5.5 suggests that the emulsifier or emulsifier blend used has a moderate affinity for both water and oil, making it suitable for creating an O/W emulsion with ostrich oil. It's important to note that the specific formulation, the desired characteristics of the final product, and the interaction between the emulsifier and ostrich oil will all play a role in determining the optimal HLB value. Experimentation and testing may be required to fine-tune the formulation and confirm that an HLB of 5.5 is indeed suitable for achieving the desired stability and characteristics in the ostrich oil O/W emulsion.

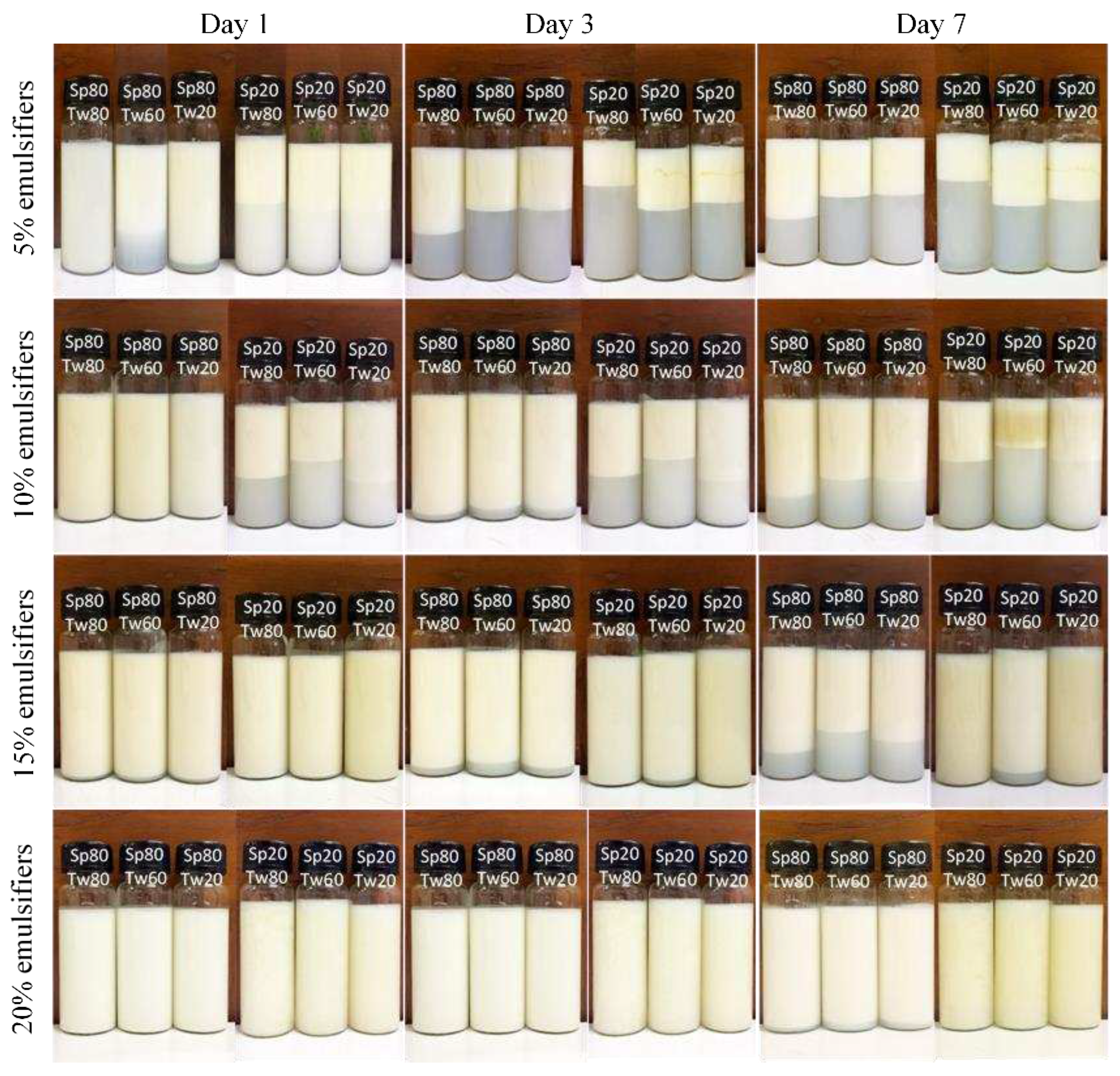

3.2.2. Effects of the Type and Concentration of Mixed Emulsifiers on the Properties of Emulsions

When an emulsifier with a particular HLB value stabilizes an emulsion containing a particular type of oil, it is generally assumed that another emulsifier with the same HLB value will have a similar emulsifying effect [

22,

23,

24]. Therefore, each variety of oil requires an emulsifier system with a unique HLB number, which corresponds to the required HLB of the oil phase. In this study, O/W emulsions with an HLB of 5.5 were prepared with 20% w/w ostrich oil and different ratios of 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixed Span and Tween emulsifiers (

Table 3). After preparing the O/W emulsions, they were stored at room temperature for 1, 3, and 7 days. Subsequently, their physical characteristics were assessed visually (

Figure 2), and their CI percentages were calculated (

Table 4). The viscosity, droplet size, zeta potential, and photomicrographs of emulsions were evaluated.

The study focuses on the effects of different Span and Tween concentrations, types, and ratios on the stability of 20% w/w ostrich oil emulsions with a target HLB value of 5.5. The experimental results revealed that the emulsion stabilized with a 15% w/w mixture of Span 20 and Tween 80 exhibited the highest stability among all formulations tested, with desirable properties in terms of creaming indices (

Table 4).

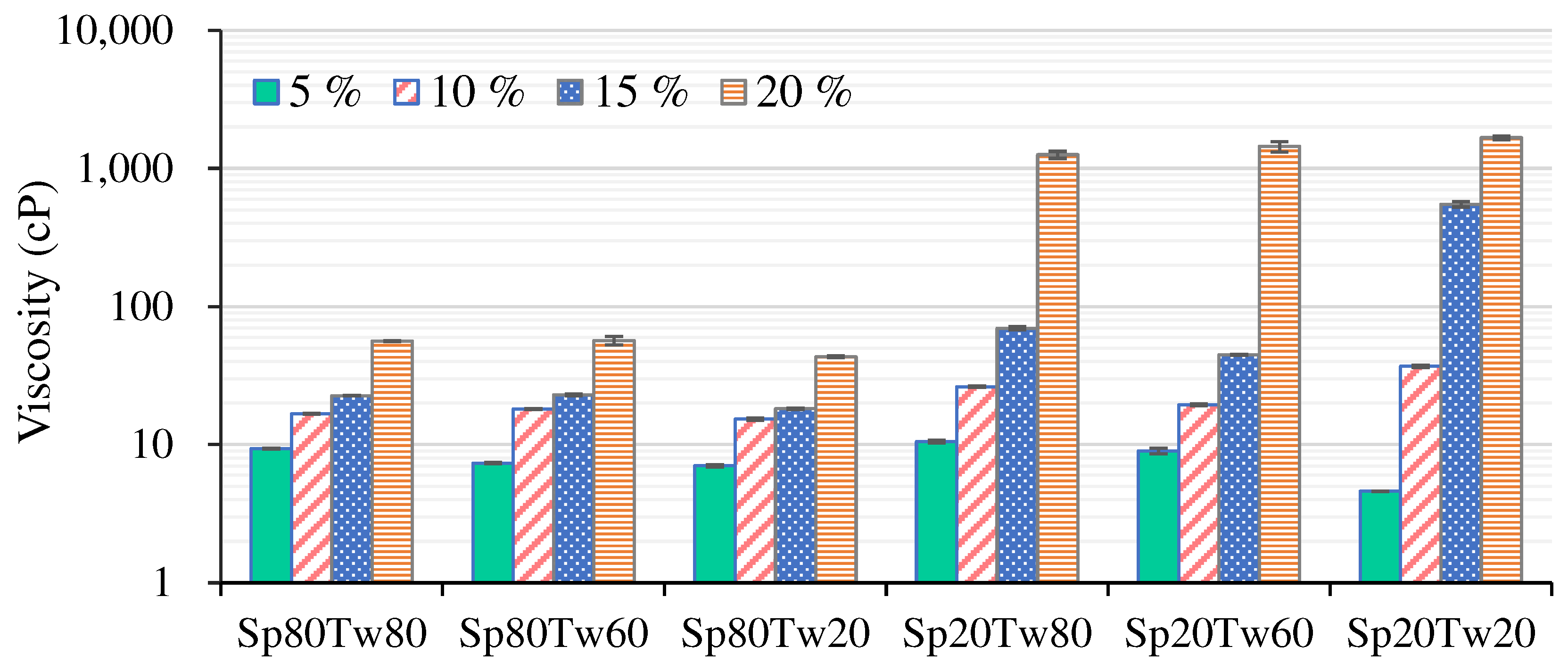

3.2.3. Viscosity

The viscosity profiles of emulsions, featuring 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span and Tween), combined with 20% w/w ostrich oil, are depicted in

Figure 3. An observable trend revealed a gradual increase in viscosities as the concentrations of mixed emulsifiers ascended from 5% to 15% w/w, indicating a positive correlation between emulsifier concentration and viscosity. Subsequently, a pronounced surge in viscosities occurred with 20% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 20 combined with Tween 80, Tween 60, or Tween 20). As previously reported [

35], the rise in viscosity can be attributed to the confinement of water molecules within the crosslinking areas of the emulsifiers. This process enhances the hydration of water molecules that are encircling the hydrophilic portions of the emulsifiers. Addressing stability, both emulsifier concentration and type were identified as factors influencing the viscosity and stability of the emulsions [

14]. The findings, derived from creaming index analysis (

Table 4) and viscosity measurements (

Figure 3), suggested that an optimal concentration for formulating O/W emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil was 15% w/w for mixed emulsifiers. Insights into the manner in which blended emulsifiers influence the viscosity and stability of emulsions are gained from these results, highlighting the importance of emulsifier type and concentration when preparing stable emulsions with ostrich oil.

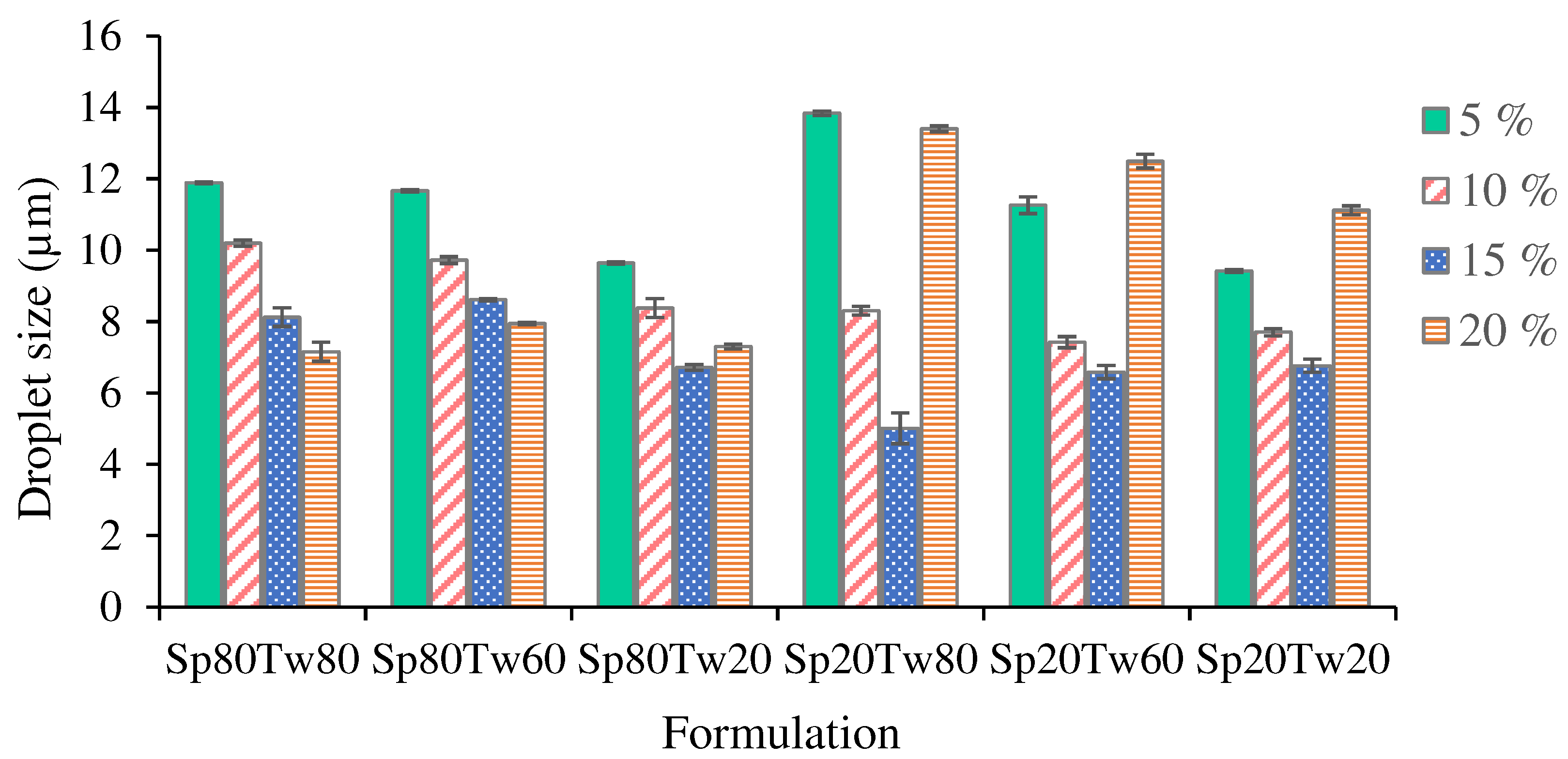

3.2.4. Droplet Size

The droplet size of oil dispersion in emulsions is depicted in

Figure 4. The results demonstrate that as the concentrations of the Span and Tween mixture increased from 5% to 15% w/w, there was a gradual reduction in emulsion droplet size. This phenomenon can be attributed to the increased reduction in surface tension between oil and water, leading to a decrease in interfacial free energy. The emulsifier plays a crucial role in both droplet break-up and recoalescence by lowering interfacial tension and preventing immediate recoalescence [

36,

37]. The emulsion containing 20% w/w ostrich oil emulsified with a 15% w/w mixture of Span 20 and Tween 80 exhibited the smallest droplet size (5.01 ± 0.43 μm), as shown in

Figure 4. Additionally, this emulsion formulation achieved a creaming index of 0.00% (

Table 4), indicating a high level of confidence in the precision of the results. This underscores the effectiveness of the emulsifier mixture in achieving fine droplet sizes and enhancing the stability of the emulsion.

3.2.5. Microscopic Examination

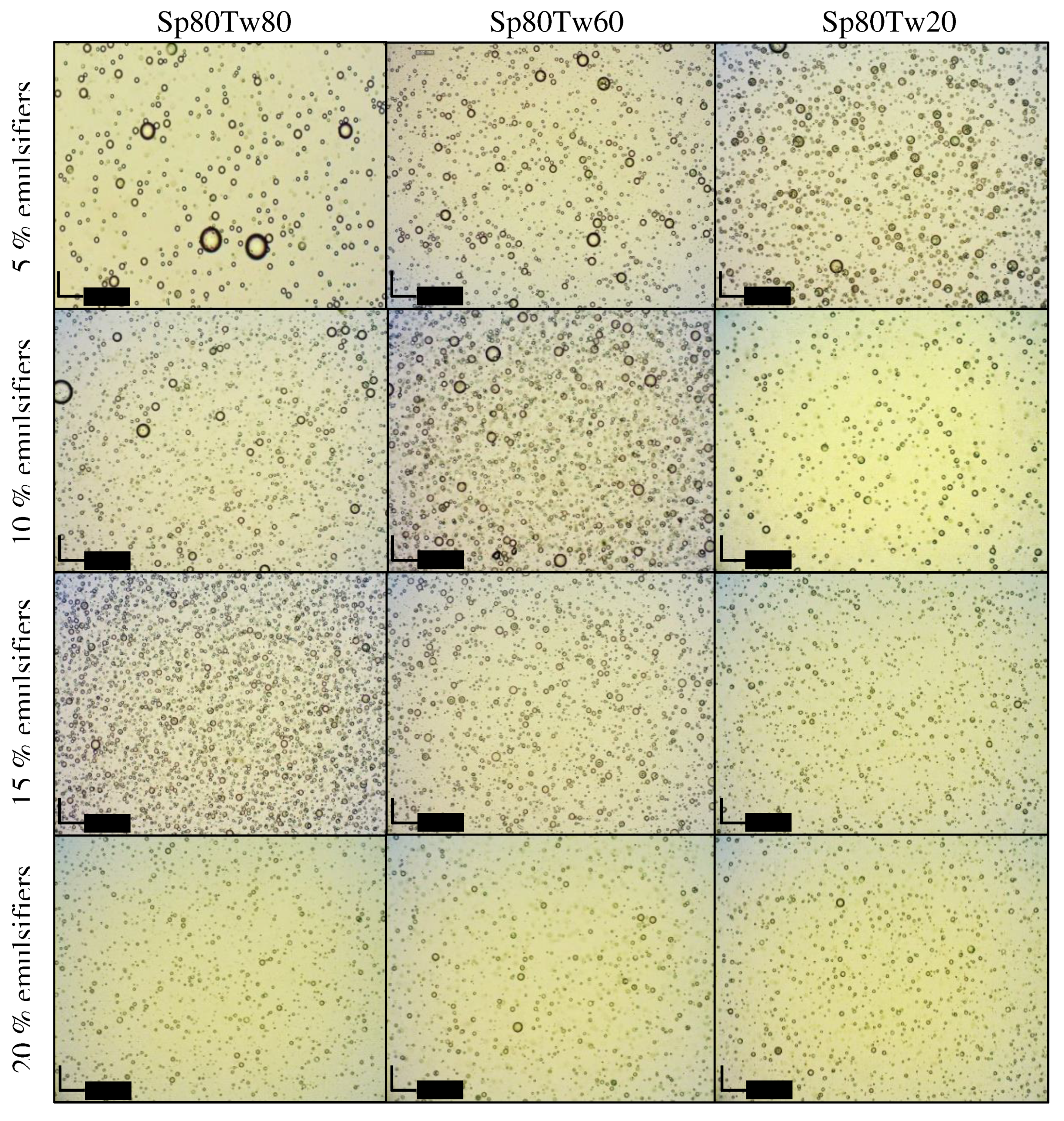

Photomicrographs illustrating emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5%, 10%, 15%, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span 80 and Tween 20, 60, or 80 are presented in

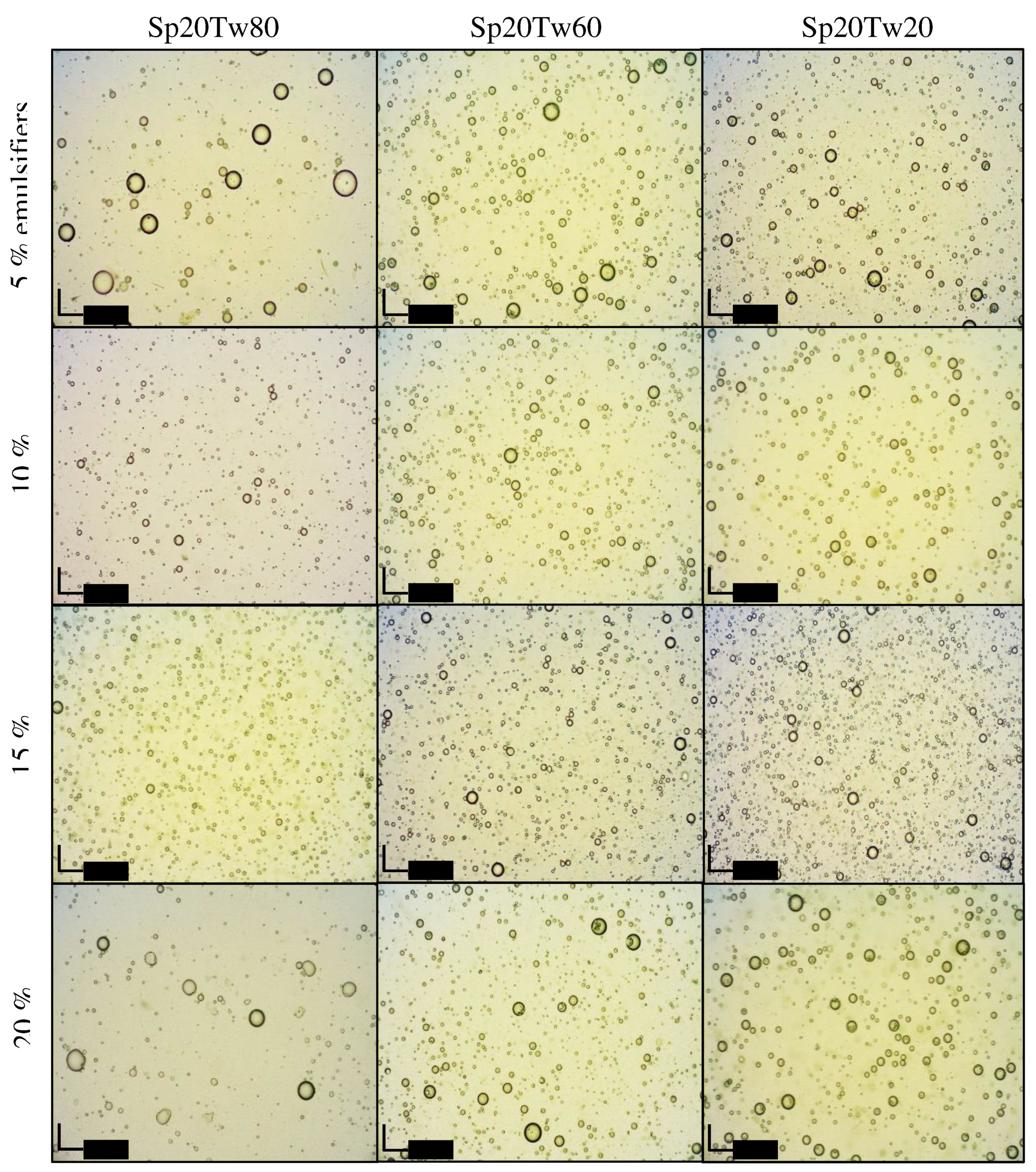

Figure 5. Additionally,

Figure 6 displays photomicrographs of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5%, 10%, 15%, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span 20 and Tween 20, 60, or 80. In

Figure 5, it is evident that the droplet size of emulsions stabilized with higher concentrations of mixed emulsifiers (15% w/w and 20% w/w) is smaller compared to those with lower concentrations (5% w/w and 10% w/w). Notably, the emulsion stabilized with 15% w/w Span 20 and Tween 80 exhibited the smallest droplet size (

Figure 6). These findings align with the droplet size information previously discussed in Topic 3.2.4. The photomicrographs provide visual confirmation of the relationship between emulsifier concentration and droplet size, supporting the idea that higher concentrations contribute to smaller droplet sizes. This information enhances our understanding of the emulsion stability achieved through specific emulsifier formulations, particularly emphasizing the efficacy of 15% w/w Span 20 and Tween 80 in minimizing droplet size in the presented emulsion system.

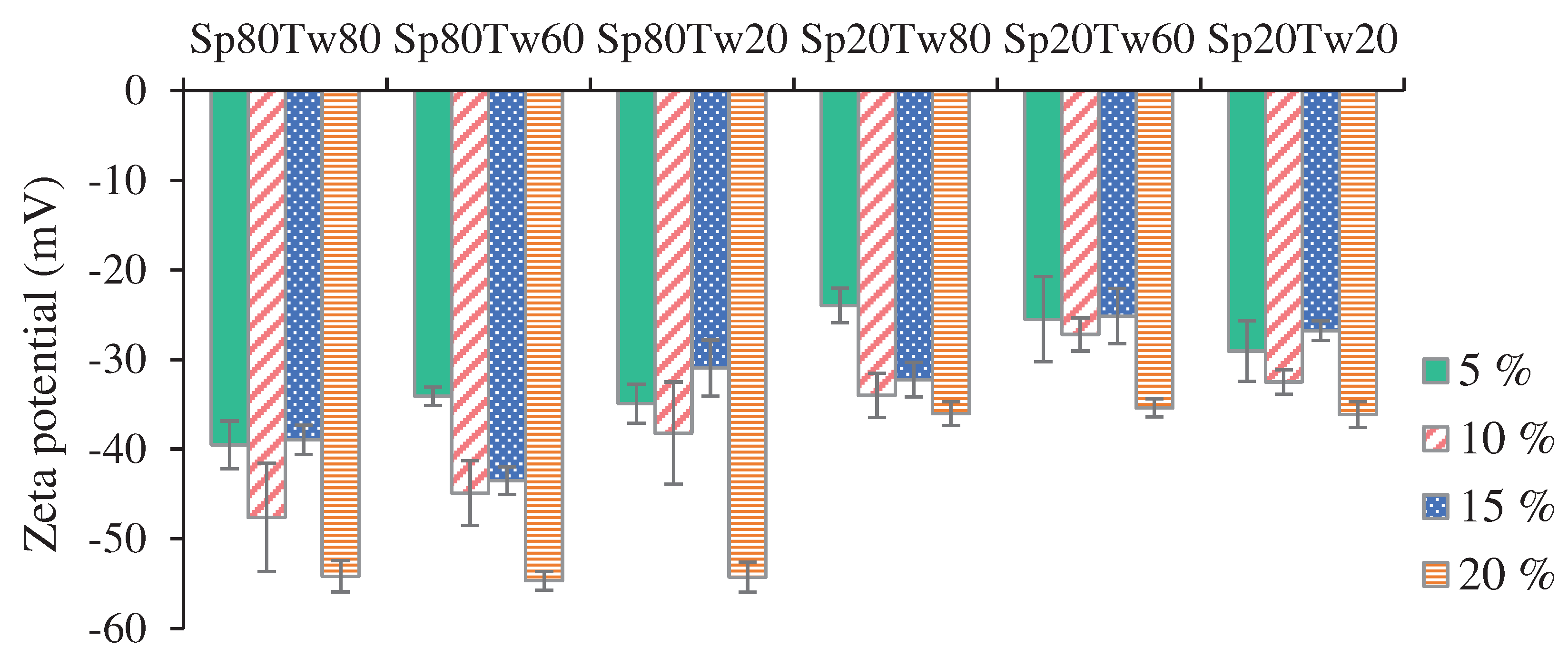

3.2.6. Zeta Potential

The zeta potential, representing electric charges on particle surfaces, serves as a crucial parameter for assessing emulsion stability. In this study, the zeta potential values for all emulsions consistently exhibited negative charges. According to previous research [

14,

38], a stable emulsion is achieved when the mutual repulsion among emulsion droplets surpasses attractive forces. Examining the zeta potential values in

Figure 7, it was observed that the emulsion stabilized with a 5% w/w concentration of Span 20 and Tween 80 displayed the highest zeta potential value (-23.97 ± 1.94 mV). Conversely, the emulsion stabilized with a 20% w/w concentration of Span 80 and Tween 60 exhibited the lowest zeta potential value (-54.68 ± 1.05 mV). Notably, negative zeta potential values in the emulsions were attributed to the carboxyl group of fatty acids present in ostrich oil.

For stable emulsions, it is generally recommended that zeta potential values exceed ±30 mV to prevent deflocculation of the emulsion system [

39]. In this context, the emulsion stabilized with a 15% w/w concentration of Span 20 and Tween 80, which showed a creaming index of 0.00% (

Table 4), demonstrated a zeta potential value of -32.22 mV (

Figure 7). These results emphasize that zeta potential values are influenced by the concentrations, types, and ratios of mixed emulsifiers. The study contributes valuable insights into how manipulating these parameters can impact the stability of emulsions, providing practical considerations for formulating stable emulsion systems.

Zeta potential is an essential determinant of the stability of an emulsion. As depicted in

Figure 7, the emulsion produced by combining 15% w/w Span 20 and Tween 80 demonstrated a notably elevated negative value of -32.22 mV. Strong electrostatic repulsion exists between the dispersed oil particles in the aqueous phase, as indicated by this result. An increase in surface charge contributes to the stability of an emulsion through the promotion of repulsive forces among particles, thereby impeding contraction and coalescence [

40]. In general, the zeta potential is utilized to assess the stability of droplets. Zeta potential values exceeding +30 mV or -30 mV indicate favorable emulsion stability [

41]. A comparatively stable system is produced when the repulsive forces of an emulsion outweigh the attractive forces, as indicated by a high zeta potential.

In this section, the influence of concentrations, types, and ratios of Span and Tween on the stability of 20% w/w ostrich oil emulsions with an HLB of 5.5 was thoroughly investigated, encompassing various physical characteristics, creaming indices, viscosities, droplet sizes, and zeta potentials. The outcomes consistently revealed that the 20% w/w ostrich oil emulsion stabilized with a 15% w/w combination of Span 20 and Tween 80 exhibited the highest degree of stability among the formulations. This finding underscores the importance of the chosen emulsifier composition and its concentration in achieving optimal stability for ostrich oil emulsions with the specified HLB.

3.2.7. Stability

To assess stability, samples from the optimized emulsion, comprising 20% w/w ostrich oil and 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 20 and Tween 80), with and without 0.01% w/w BHT, were subjected to storage at different temperatures: 4 °C, 25 °C, and 45 °C. The evaluation included measurements of AV, PV, phase separation, and microbial contamination at various time points (0, 1, 3, and 6 months). AV and PV served as indicators for assessing the physicochemical stability of the optimized ostrich oil emulsions with and without BHT. An increase in free fatty acids (elevated AV) in samples suggests triglyceride hydrolysis of ostrich oil in the emulsions. Compounds such as free butyric, capric, caprylic, and caproic acids, produced by hydrolysis, are responsible for the rancid flavor of oils. PV, on the other hand, indicates the level of primary oxidation in oils by measuring the hydroperoxides generated during oxidation. Therefore, AV and PV are key parameters associated with the stability of the oil [

42].

The AVs of samples with and without BHT stored at 4 °C and samples with BHT at 25 °C did not exhibit significant differences over the 6-month storage period, as indicated in

Table 5. During the initial month of storage, AVs of samples without BHT kept at 25 °C showed a slight increase, while those of samples without BHT stored at 45 °C experienced a substantial increase. Following the first month of storage, samples maintained at higher temperatures (25 °C and 45 °C) displayed elevated AVs, with the highest values observed in samples without BHT stored at 45 °C (

Table 5). Concerning PVs of samples stored at different temperatures, PVs of samples determined at 4 °C and 25 °C slightly increased, while values of samples stored at 45 °C exhibited a considerable increase over the 6-month storage period. Notably, samples without BHT stored at 45 °C for 6 months displayed the highest AV and PV. These findings suggest that ostrich oil in emulsions is more susceptible to deterioration and rancidity at higher temperatures in the absence of BHT. In summary, the emulsion of ostrich oil with BHT contributes to increased stability, particularly at elevated temperatures. However, it's noteworthy that the AVs and PVs obtained from the stability testing remained within the allowable limits of 2 mg KOH/g sample and 10 mEq O2/kg sample [

32]. This suggests that, despite the observed changes, the quality of the ostrich oil emulsions remained within acceptable standards throughout the storage period. Furthermore, the results of the AVs and PVs in

Table 5 showed that the optimized O/W emulsions could maintain the stability of ostrich oil by reducing hydrolysis and oxidation processes.

The phase separation of samples obtained from different storage temperatures was determined using creaming indices expressed as percentages. All emulsion samples, both with and without BHT, kept at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 45 °C for 6 months exhibited creaming indices of 0.00%, indicating excellent physical stability. No microbial contamination by

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa was detected in 1 g of each sample, with or without BHT, over the 6-month period at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 45 °C, aligning with the USP acceptance criteria for the microbiological quality of non-sterile topical dosage forms [

43], which specifies the absence of

S. aureus and

P. aeruginosa in 1 g of any samples. The TAMC and TYMC of samples with BHT were not detected, while those without BHT gradually increased at all storage temperatures for 1, 3, and 6 months. Particularly, samples without BHT stored at 45 °C exhibited the highest TAMC (50 CFU/g) and TYMC (< 10 CFU/g). However, it's important to note that these values remained within the USP acceptance criteria for the microbiological quality of non-sterile topical dosage forms [

43], which specify that TAMC and TYMC should not exceed 10

2 CFU/g and 10

1 CFU/g, respectively. Thermal stability investigations over the 6-month period indicated that the optimized formulations with BHT remained largely unaffected by a range of climatic conditions, except for occasional instances of phase separation and microbial contamination.

The comprehensive examination of the optimized emulsion's stability under diverse temperature conditions is crucial for assessing its suitability for real-world applications. By subjecting the emulsion to controlled environments, the study aimed to simulate conditions it might encounter during storage and transportation. The inclusion of ostrich oil, mixed emulsifiers, and BHT in the formulation suggests a complex composition designed for specific performance and stability. BHT, known for its antioxidant properties [

44], is commonly used to prevent oxidation and enhance the stability of oil formulations. The emulsifiers, Span 20 and Tween 80, likely contribute to the emulsion's stability and consistency. The study's findings, indicating that temperature variations within the specified range did not lead to significant changes in the emulsion's integrity, are promising. This suggests that the formulation maintains its structural and functional properties even under challenging climatic conditions. Such stability is essential for ensuring the product's effectiveness and safety over time. It's worth noting that the use of controlled storage conditions and rigorous testing methodologies enhances the reliability of the results. These findings provide valuable insights into the robustness of the emulsion, supporting its potential for practical applications where stability is a critical factor.

3.2.8. Cytotoxicity Assay

An in vitro cytotoxicity assessment was carried out to gauge the safety of the optimized emulsion containing ostrich oil, specifically formulated for topical skin application. Human dermal fibroblasts served as the model organism for assessing potential skin damage. Remarkably, when subjected to the optimized emulsion comprising 20% w/w ostrich oil and 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 20 and Tween 80) at a concentration below 3.2 mg/ml for a duration of up to 24 h, CRL-2076 human dermal fibroblasts exhibited no statistically significant difference in viability compared to control cells. This suggests a favorable safety profile for the formulation, highlighting its potential suitability for skin application.

3.2.9. Antibacterial Assay

To assess the antibacterial efficacy, the following microorganisms were employed: Gram-positive S. aureus ATCC 6538P, Gram-negative E. coli DMST 4212, and Gram-negative facultatively anaerobic and aerobic P. aeruginosa ATCC 9027. In that specific order, the inhibition zones of the optimized emulsion comprising 20% w/w ostrich oil and 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 20 and Tween 80) measured 12.32 ± 0.19 mm, 6.93 ± 0.18 mm, and 6.3 ± 0.14 mm. In contrast, when tested exclusively on S. aureus, ostrich oil demonstrated an inhibitory zone measuring 6.12 ± 0.15 mm. No inhibition zone was observed against E. coli or P. aeruginosa. Bactericidal effects of lincomycin were detected against all microorganisms during testing, as indicated by inhibitory zones with respective dimensions of 27.00 ± 0.65 mm, 21.03 ± 0.25 mm, and 8.02 ± 0.18 mm.

The results reveal that the optimized emulsion demonstrated antibacterial activity against the tested microorganisms. Upon closer examination, it can be deduced that Gram-positive bacteria exhibit greater susceptibility to the optimized emulsion with ostrich oil. This heightened susceptibility is likely attributable to variations in cellular wall architecture. Gram-positive bacteria are characterized by a thick peptidoglycan layer and, in some instances, the presence of teichoic acids. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria possess a thinner peptidoglycan layer surrounded by an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides. These structural distinctions have significant implications for bacterial susceptibility to various substances. For instance, the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria can confer increased resistance to certain antibiotics or bioactive compounds compared to Gram-positives [

45].

Bacteria, including

S. aureus,

E. coli, and

P. aeruginosa, are commonly associated with various infections and are frequently found in diverse environments. The presence of these bacteria in a scratch or wound may indicate a potential risk of infection, as they are recognized pathogens [

46].

S. aureus is typically present on the skin and mucous membranes and can lead to skin infections, abscesses, and more severe conditions, such as bloodstream infections. Certain strains of

E. coli have the potential to cause infections, particularly if they contaminate wounds.

P. aeruginosa is notorious for causing skin and soft tissue infections, especially in wounds and burns. Therefore, it is imperative to seek antibacterial topical products for the treatment of scratches or wounds. However, the appropriate treatment will depend on the severity of the infection and the specific bacteria involved.

3.2.10. Antioxidant Assay

The antioxidant activity of ostrich oil and an optimized emulsion containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 20 and Tween 80) was evaluated by measuring the percentage inhibition of linoleic acid oxidation at a test concentration of 2.4 mg/ml on Day 5. The results showed that the percentage inhibition for ostrich oil and the optimized emulsion was 44.70 ± 1.94% and 52.20 ± 2.01%, respectively. In comparison, Trolox (the positive control) had a percentage inhibition of 58.20 ± 5.18%. These findings indicate that the antioxidant activity of ostrich oil is enhanced after encapsulation in an O/W emulsion. Notably, the optimized emulsion exhibited a significantly higher percentage inhibition compared to ostrich oil alone. The observed influence of the O/W emulsion on antioxidant activity was found to be statistically significant (p > 0.05).

The application of antioxidant activity can be advantageous when it comes to treating injuries and wounds. Antioxidants are compounds that aid in the neutralization of free radicals, which are detrimental molecules capable of inducing oxidative stress and causing cellular damage [

47]. Antioxidants have the potential to alleviate inflammation, a physiological reaction that occurs in response to injury but can hinder the recovery process when it becomes excessive [

48]. Antioxidants serve to safeguard cells against oxidative damage, thereby facilitating the body's intrinsic capacity to restore compromised tissues. Scar formation may be mitigated with the assistance of antioxidants, which promote the regeneration of healthy skin cells. Antioxidants have the potential to facilitate the synthesis of collagen, an essential protein that is involved in the structure of the epidermis and the healing of wounds [

49].

It is crucial to acknowledge that although antioxidant-rich substances may provide advantages, the principal emphasis in wound care lies in maintaining wound cleanliness, infection protection, and a conducive environment for uncomplicated healing. While topical ostrich oil emulsions featuring antioxidant and antibacterial properties may be regarded as supplementary treatments, it is imperative to seek the advice of a healthcare professional prior to implementing any additional measures, particularly when dealing with severe injuries or infections that require immediate attention.

The heightened antioxidant and antibacterial characteristics observed in an emulsion containing ostrich oil, as opposed to ostrich oil alone, can be ascribed to a number of emulsification process-related factors and the synergistic influences of the emulsion constituents. There are several significant considerations. The emulsification process considerably increases the available surface area for interaction by reducing the ostrich oil to smaller droplets, thereby increasing the surface area available for interaction. The augmented surface area facilitates enhanced interaction between ostrich oil and reactive molecules or microorganisms, thereby augmenting the overall efficacy. In order to enhance dispersion, emulsification guarantees that the oil is distributed more uniformly across the formulation. The even dispersion of these compounds enhances the oil's capacity to interact with microbes and free radicals, thereby optimizing its antibacterial and antioxidant properties [

50]. Reduced droplet diameters within the emulsion have the potential to augment the bioavailability of bioactive compounds that are found in ostrich oil. The enhanced bioavailability of the oil's beneficial components facilitates their improved absorption and utilization by epidermis cells or microbes [

51]. In order to enhance the stability of the formulation, emulsions frequently incorporate emulsifiers and stabilizers (e.g., Span 20 and Tween 80) as stabilizing agents. Additionally, these agents might possess intrinsic qualities that augment their antimicrobial and antioxidant impacts as a whole [

52]. The integration of emulsifiers with ostrich oil may result in synergistic effects, wherein the distinct constituents collaborate to augment the overall effectiveness. By forming a stable and adherent layer on the skin, emulsions can extend the duration of contact between the oil and the affected area or wound [

53]. The protracted contact time facilitates a sustained release of bioactive compounds, thereby enhancing the duration of their antibacterial and antioxidant properties. As a result, the emulsification procedure serves to improve the chemical and physical characteristics of ostrich oils, thereby increasing their efficacy in demonstrating antioxidant and antibacterial properties. The enhanced properties of emulsions bearing ostrich oil can be attributed to a combination of factors, including increased surface area, improved dispersion, stabilizing agents, and possible synergistic effects.

4. Conclusions

The objective of this research was to develop an O/W emulsion that was optimized by incorporating substantial 20% ostrich oil and 15% w/w blended emulsifiers (Span 20 and Tween 80) via homogenization. The O/W emulsion that was optimized exhibited the most minute particle size of 5.01 ± 0.43 μm and a suitable zeta potential of -32.22 mV. In preparation for topical administration, it exhibited a positive safety profile during testing on CRL-2076 human dermal fibroblasts. Upon enrichment with ostrich oil, the optimized O/W emulsion demonstrated significantly heightened antibacterial and antioxidant properties compared to ostrich oil alone. Due to these observed properties, the optimized emulsion is highly suitable for topical application. Physical and microbial stability were maintained by the emulsion, which contained 20% w/w ostrich oil, 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 20 and Tween 80), and 0.01% w/w BHT, according to stability experiments conducted over a period of 6 months at temperatures of 4 °C, 25 °C, and 45 °C. This research highlights the feasibility of employing ostrich oil in topical formulations, shedding light on its efficacy in O/W emulsions. The aforementioned results indicate possible uses in the formulation of topical emulsions that incorporate a range of animal oils.

Author Contributions

Methodology, writing—original draft, C.L. and J.P.; data collecting, J.P.; data curation, C.L., J.P. and S.L.; conceptualization, C.L. and S.L.; supervision, C.L.; writing—review and editing and project administration, C.L., J.P. and S.L.; validation, S.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Silpakorn University under the Postdoctoral fellowship program [grant number: SURDI Postdoctoral/66/4].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, the corresponding author will provide access to the data utilized to substantiate the conclusions drawn in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Faculty of Pharmacy, Silpakorn University for providing the facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The author affirms that no financial or commercial relationships that might be construed as a potential conflict of interest existed during the course of the research.

Ethics

The acquisition of fresh ostrich fat for the study followed established animal welfare guidelines.

References

- Ponphaiboon, J.; Limmatvapirat, S.; Chaidedgumjorn, A.; Limmatvapirat, C. Physicochemical Property, Fatty Acid Composition, and Antioxidant Activity of Ostrich Oils using Different Rendering Methods. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 93, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, M. Animal fats-edible oil processing, The American Oil Chemists' Society (AOCS) Lipid Library, 2013. Available online: https://lipidlibrary.aocs.org/edible-oil-processing/animal-fats (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Sharma, H.; Giriprasad, R.; Goswami, M. Animal Fat-processing and Its Quality Control. Int. J. Food Process. Technol. 2013, 4, 1000252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belichovska, D.; Hajrulai-Musliu, Z.; Uzunov, R.; Belichovska, K.; Arapcheska, M. Fatty Acid Composition of Ostrich (Struthio Camelus) Abdominal Adipose Tissue. Maced. Vet. Rev. 2015, 38, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xue, Y.; Chen, G.C.; Zhang, A.J.; Chen, Z.F.; Liao, X.; Ding, L.S. Rapid Separation and Characterisation of Triacylglycerols in Ostrich Oil by Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Quadrupole Time-of-flight Mass Spectrometry. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2098–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. n-3 Fatty acids, Inflammation, and Immunity-relevance to Postsurgical and Critically Ill Patients. Lipids 2004, 39, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.; Serra-Majem, L.; Calder, P.C.; Uauy, R. Systematic Reviews of the Role of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavanji, S.; Larki, B.; Taraghian, A.H. A Review of Application of Ostrich Oil in Pharmacy and Diseases Treatment. J. Nov. Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 650–654. [Google Scholar]

- Eltom, S.E.M.; Abdellatif, A.A.H.; Maswadeh, H.; Al-Omar, M.S.; Abdel-Hafez, A.A.; Mohammed, H.A.; Agabein, E.M.; Alqasoomi, I.; Alrashidi, S.A.; Sajid, M.S.M.; Mobark, M.A. The Anti-inflammatory Effect of γ-Lactone Isolated from Ostrich Oil of Struthio camelus (Ratite) and Its Formulated Nano-emulsion in Formalin-induced Paw Edema. Molecules 2021, 26, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, S.M. Preparation, Characterization and In Vivo Anti-inflammatory Studies of Ostrich Oil Based Nanoemulsion. J. Oleo Sci. 2019, 68, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.C.; Leung, G.; Wang, E.; Ma, S.; Lo, B.K.; McElwee, K.J.; Cheng, K.M. Ratite Oils Promote Keratinocyte Cell Growth and Inhibit Leukocyte Activation. Poult. Sci, 2015; 94, 2288–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahpour, M.R.; Vahid, M.; Oryan, A. Effectiveness of Topical Application of Ostrich Oil on the Healing of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected Wounds. Connect. Tissue Res. 2018, 59, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzuto, J.M.; Park, E.J. Autooxidation and Antioxidation. In Encyclopedia of Pharmaceutical Technology, 3rd ed.; Swarbrick, J., Ed.; PharmaceuTech, Inc.: Pinehurst, North Carolinia, USA, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, B.A.; Akhtar, N.; Khan, H.M.S.; Waseem, K.; Mahmood, T.; Rasul, A.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, H. Basics of Pharmaceutical Emulsions: A Review. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 5, 2715–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton-Carabin, C.C.; Ropers, M.H.; Genot, C. Lipid Oxidation in Oil-in-Water Emulsions: Involvement of the Interfacial Layer. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 945–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmatvapirat, C.; Limmatvapirat, S.; Krongrawa, W.; Ponphaiboon, J.; Witchuchai, T.; Jiranuruxwong, P.; Theppitakpong, P.; Pathomcharoensukchai, P. Beef Tallow: Extraction, Physicochemical Property, Fatty Acid Composition, Antioxidant Activity, and Formulation of Lotion Bars. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 11, 018–028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmatvapirat, C.; Limmatvapirat, S.; Chansatidkosol, S.; Krongrawa, W.; Liampipat, N.; Leechaiwat, S.; Lamaisri, P.; Siangjong, L.; Meetam, P.; Tiankittumrong, K. Preparation and properties of anti-nail-biting lacquers containing shellac and bitter herbal extract. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 8537544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The American Oil Chemists’ Society. AOCS Official Method Cd 3d-63: Acid Value of Fats and Oils. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the AOCS, 7 th ed.; Champaign, Illinois, USA, 2017.

- The American Oil Chemists’ Society. AOCS Official Method Cd 8b-90: Peroxide Value, Acetic Acid, Isooctane Method. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the AOCS, 7 th ed.; Champaign, Illinois, USA, 2017.

- Limmatvapirat, C.; Limmatvapirat, S.; Charoenteeraboon, J.; Wessapan, C.; Kumsum, A.; Jenwithayaamornwech, S.; Luangthuwapranit, P. Comparison of Eleven Heavy Metals in Moringa oleifera Lam. Products. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 77, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. 〈61〉 Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Microbial Enumeration Tests. The United States Pharmacopeia 43 and the National Formulary 38 (USP 43-NF 38), 2023. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, W.; Mohammad, T.G. Effect of Hydrophilic-lipophilic Balance (HLB) Values of Surfactant Mixtures on the Physicochemical Properties of Emulsifiable Concentrate Formulations of Difenoconazole. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int. 2019, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, M.G.B.; Reis, S.A.G.B.; Damasceno, C.M.D.; Rolim, L.A.; Rolim-Neto, P.J.; Carvalho, F.O.; Quintans-Junior, L.J.; Almeida, J.R.G.d.S. Development and Evaluation of Stability of a Gel Formulation Containing the Monoterpene Borneol. Sci. World J, 2016; 7394685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.R.A.; Santiago, R.R.; de Souza, T.P.; Egito, E.S.T.; Oliveira, E.E.; Soares, L.A.L. Development and Evaluation of Emulsions from Carapa guianensis (Andiroba) Oil. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, S.; Wagner, G.; Urban, K.; Ulrich, J. High-Pressure Homogenization as a Process for Emulsion Formation. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2004, 27, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirwana, I.; Munadziroh, E.; Yogiartono, R.M.; Thiyagu, C.; Ying, C.S.; Dinaryanti, A. Cytotoxicity and Proliferation Evaluation on Fibroblast After Combining Calcium Hydroxide and Ellagic Acid. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2021, 12, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.W.; Kirby, W.M.; Sherris, J.C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing by a Standardized Single Disk Method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 45, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balić, A.; Vlašić, D.; Žužul, K.; Marinović, B.; Mokos1, Z.B. Omega-3 Versus Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Gad, M.Z. Omega-9 Fatty Acids: Potential Roles in Inflammation and Cancer Management. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yff, B.T.S.; Lindsey, K.L.; Taylor, M.B.; Erasmus, D.G.; Jäger, A.K. The Pharmacological Screening of Pentanisia prunelloides and the Isolation of the Antibacterial Compound Palmitic Acid. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 79, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, M.H.; Marcelletti, J.F.; Katz, L.R.; Katz, D.H.; Pope, L.E. Topical Application of Docosanol- or Stearic Acid-containing Creams Reduces Severity of Phenol Burn Wounds in Mice. Contact Dermatitis 2000, 43, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Codex Standard for Fats and Oils from Animal Sources, Codex Standard for Named Animal Fats (CODEX-STAN 211 - 1999), Codex Alimentarius: Fats, oils and related products; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Santin, J.R.; Kopp, M.A.T.; Correa, T.P.; Melato, J.; Benvenutti, L.; Nunes, R.; Goldoni, F.C.; Patel, Y.B.K.; Souza, J.A.; Soczek, S.H.S.; Fernandes, E.S.; Pastor, M.V.D.; Junior, L.C.K.; Apel, M.A.; Henriques, A.T.; Quintão, N.L.M. Neuroinflammation and Hypersensitivity Evidenced by the Acute and 28-day Repeated Dose Toxicity Tests of Ostrich Oil in Mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 177, 113852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, S. Effect of Mixing Protocol on Formation of Fine Emulsions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2006, 61, 3009–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, M.M.; Badawy, M.E.I.; Taktak, N.E.M. Characterization, Antimicrobial Activity, and Antioxidant Activity of the Nanoemulsions of Lavandula spica Essential Oil and Its Main Monoterpenes. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 65, 102732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adheeb Usaid, A.S.; Premkumar, J.; Ranganathan, T.V. Emulsion and It’s Applications in Food Processing - A Review. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2014, 4, 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ramisetty, K.A.; Shyamsunder, R. Effect of Ultrasonication on Stability of Oil in Water Emulsions. Int. J. Drug Deliv. 2011, 3, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.A.; Akhtar, N.; Khan, H.M.S.; Waseem, K.; Mahmood, T.; Rasul, A.; Iqbal, M.; Khan, H. Basics of Pharmaceutical Emulsions: A Review. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 5, 2715–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Dong, H.; Dai, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, R. The Effects of Pectin Structure on Emulsifying, Rheological, and In Vitro Digestion Properties of Emulsion. Foods 2022, 11, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachurski, J.; MichaŁek, M. The Effect of the ζ Potential on the Stability of a Non-Polar Oil-in-Water Emulsion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996, 184, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honary, S.; Zahir, F. Effect of Zeta Potential on the Properties of Nano-Drug Delivery Systems - A Review (Part 1). Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 12, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignitter, M.; Somoza, V. Critical Evaluation of Methods for the Measurement of Oxidative Rancidity in Vegetable Oils. J. Food Drug Anal. 2012, 20, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. 〈1111〉 Microbiological Examination of Nonsterile Products: Acceptance Criteria for Pharmaceutical Preparations and Substances for Pharmaceutical Use. The United States Pharmacopeia 43 and the National Formulary 38 (USP 43-NF 38), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Yu, C.; Liang, M.; Cheng, H.; Li, W.; Lai, F.; Ma, L.; Liu, X. Oxidation Characteristics and Thermal Stability of Butylated Hydroxytoluene. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Jubeh, B.; Karaman, R. Resistance of Gram-Negative Bacteria to Current Antibacterial Agents and Approaches to Resolve It. Molecules 2020, 25, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puca, V.; Marulli, R.Z.; Grande, R.; Vitale, I.; Niro, A.; Molinaro, G.; Prezioso, S.; Muraro, R.; Giovanni, P.D. Microbial Species Isolated from Infected Wounds and Antimicrobial Resistance Analysis: Data Emerging from a Three-Years Retrospective Study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free Radicals, Antioxidants and Functional Foods: Impact on Human Health. Phcog. Rev. 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arulselvan, P.; Fard, M.T.; Tan, W.S.; Gothai, S.; Fakurazi, S.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Kumar, S.S. Role of Antioxidants and Natural Products in Inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 5276130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino-Sanz, I.M.; López-Franco, M.D.; Castro, B.; Pancorbo-Hidalgo, P.L. The Role of Antioxidants on Wound Healing: A Review of the Current Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mcclements, D.J.; Mclandsborough, L.A. Interaction Between Emulsion Droplets and Escherichia coli Cells. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixé-Roig, J.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Martín-Belloso, O. Emulsion-Based Delivery Systems to Enhance the Functionality of Bioactive Compounds: Towards the Use of Ingredients from Natural, Sustainable Sources. Foods 2023, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. , Tu, Z., Sha, X., Ye, Y., & Li, Z. Flavor, Antimicrobial Activity, and Physical Properties of Composite Film Prepared with Different Surfactants. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3099–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo, V.; Díaz, E.; Muñoz, L.N.; González-Barrios, A.F.; Rodríguez-Cortina, J.; Cruz, J.C.; Muñoz-Camargo, C. Enhancing Wound Healing: A Novel Topical Emulsion Combining CW49 Peptide and Lavender Essential Oil for Accelerated Regeneration and Antibacterial Protection. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The physical appearances of emulsions with varying HLB values containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5% w/w mixed emulsifier of Span 80 and Tween 80 in varied ratios.

Figure 1.

The physical appearances of emulsions with varying HLB values containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5% w/w mixed emulsifier of Span 80 and Tween 80 in varied ratios.

Figure 2.

Visual characteristics of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and a 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w emulsifier mixture of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) on days 1, 3, and 7.

Figure 2.

Visual characteristics of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and a 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w emulsifier mixture of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) on days 1, 3, and 7.

Figure 3.

Viscosities of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) mixed emulsifiers.

Figure 3.

Viscosities of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) mixed emulsifiers.

Figure 4.

Droplet size of the emulsions comprising 20% w/w ostrich oil and a 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixture of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw).

Figure 4.

Droplet size of the emulsions comprising 20% w/w ostrich oil and a 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixture of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw).

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span (Sp) 80 and Tween (Tw) 20, 60, or 80.

Figure 5.

Photomicrographs of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span (Sp) 80 and Tween (Tw) 20, 60, or 80.

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span (Sp) 20 and Tween (Tw) 20, 60, or 80.

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span (Sp) 20 and Tween (Tw) 20, 60, or 80.

Figure 7.

Zeta potential of the emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw).

Figure 7.

Zeta potential of the emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixtures of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw).

Table 1.

O/W emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 80 and Tween 80), as well as their required HLB values and creaming indices.

Table 1.

O/W emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5% w/w mixed emulsifiers (Span 80 and Tween 80), as well as their required HLB values and creaming indices.

| Formulation |

Distilled Water

(% w/w) |

Ostrich oil

(% w/w)

|

Emulsifier (5% w/w)

|

HLB |

Creaming Index (%) |

Span 80

(% w/w) |

Tween 80

(% w/w) |

Span 80 : Tween 80 (w/w) |

| 1 |

75 |

20 |

5 |

0 |

5 : 0 |

4.3 |

12.38 |

| 2 |

75 |

20 |

4.82 |

0.18 |

26 : 1 |

4.7 |

11.29 |

| 3 |

75 |

20 |

4.67 |

0.33 |

14 : 1 |

5.0 |

4.27 |

| 4 |

75 |

20 |

4.43 |

0.57 |

8 : 1 |

5.5 |

0.00 |

| 5 |

75 |

20 |

4.20 |

0.80 |

5 :1 |

6.0 |

9.69 |

Table 2.

Retention time and linearity of FAME standards.

Table 2.

Retention time and linearity of FAME standards.

| FAME Standards |

Retention Time

(min) |

Regression Equation (y=ax+b) |

Correlation Coefficient (r2) |

| Methyl laurate |

2.8 |

y = 1.0931x + 0.0013 |

0.9998 |

| Methyl myristate |

4.1 |

y = 1.1781x + 0.0023 |

0.9998 |

| Methyl palmitate |

6.8 |

y = 0.8441x - 0.0100 |

0.9998 |

| Methyl stearate |

12.2 |

y = 0.9189x - 0.0121 |

0.9998 |

| Methyl oleate |

13.1 |

y = 1.2001x - 0.0087 |

0.9999 |

| Methyl linoleate |

15.1 |

y = 1.1643x + 0.0116 |

0.9998 |

| Methyl linolenate |

18.5 |

y = 1.1147x - 0.0014 |

0.9998 |

Table 3.

O/W emulsion with an HLB of 5.5 containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w combined Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) emulsifiers.

Table 3.

O/W emulsion with an HLB of 5.5 containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w combined Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) emulsifiers.

| Fomulation |

Distilled Water

(% w/w) |

Ostrich Oil

(% w/w) |

Span (Sp)

(% w/w) |

Tween (Tw)

(% w/w) |

| 5% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

75 |

20 |

4.44 |

0.56 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

75 |

20 |

4.42 |

0.58 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

75 |

20 |

4.52 |

0.48 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

75 |

20 |

3.72 |

1.28 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

75 |

20 |

3.70 |

1.30 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

75 |

20 |

3.76 |

1.24 |

| 10% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

70 |

20 |

8.88 |

1.12 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

70 |

20 |

8.86 |

1.14 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

70 |

20 |

9.04 |

0.96 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

70 |

20 |

7.54 |

2.46 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

70 |

20 |

7.52 |

2.48 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

70 |

20 |

7.84 |

2.16 |

| 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

65 |

20 |

13.32 |

1.68 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

65 |

20 |

13.30 |

1.70 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

65 |

20 |

13.54 |

1.46 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

65 |

20 |

11.30 |

3.70 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

65 |

20 |

11.28 |

3.72 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

65 |

20 |

11.74 |

3.26 |

| 20% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

60 |

20 |

17.76 |

2.24 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

60 |

20 |

17.74 |

2.26 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

60 |

20 |

18.06 |

1.94 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

60 |

20 |

15.08 |

4.52 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

60 |

20 |

15.04 |

4.96 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

60 |

20 |

15.66 |

4.34 |

Table 4.

Creaming index percentages of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and a 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixture of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) on Days 1, 3, and 7.

Table 4.

Creaming index percentages of emulsions containing 20% w/w ostrich oil and a 5, 10, 15, or 20% w/w mixture of Span (Sp) and Tween (Tw) on Days 1, 3, and 7.

| Formulation |

Percent of Creaming Index |

| Day 1 |

Day 3 |

Day 7 |

| 5% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

0.00 |

11.32 |

25.45 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

30.48 |

34.55 |

45.45 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

7.41 |

20.00 |

23.64 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

50.91 |

60.00 |

60.00 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

46.73 |

50.91 |

54.55 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

46.73 |

50.91 |

54.55 |

| 10% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

0.00 |

5.56 |

23.64 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

0.00 |

7.41 |

36.36 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

0.00 |

7.41 |

35.71 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

40.00 |

41.07 |

52.63 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

51.79 |

52.63 |

61.02 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

35.71 |

35.09 |

51.67 |

| 15% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

0.00 |

7.14 |

18.97 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

0.00 |

9.09 |

36.84 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

0.00 |

7.14 |

44.83 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

0.00 |

3.45 |

8.20 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| 20% w/w mixed emulsifiers |

| Sp80Tw80 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Sp80Tw60 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

6.52 |

| Sp80Tw20 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

6.52 |

| Sp20Tw80 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Sp20Tw60 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Sp20Tw20 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Table 5.

AVs and PVs of the optimized emulsion with and without BHT.

Table 5.

AVs and PVs of the optimized emulsion with and without BHT.

| Sample |

Storage Temperature (°C) |

AV (mg KOH/g Sample |

PV (mEq O2/kg Sample) |

| Initial |

1 Month |

3 Months |

6 Months |

Initial |

1 Month |

3 Months |

6 Months |

Optimized emulsion

with BHT |

4 °C |

0.09 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

2.50 ± 0.10 |

2.50 ± 0.10 |

2.50 ± 0.11 |

2.50 ± 0.10 |

| 25 °C |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

2.50 ± 0.10 |

2.61 ± 0.12 |

2.61 ± 0.11 |

| 45 °C |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

0.23 ± 0.02 |

2.55 ± 0.10 |

2.98 ± 0.15 |

3.72 ± 0.21 |

Optimized emulsion

without BHT |

4 °C |

0.09 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

2.50 ± 0.10 |

2.51 ± 0.10 |

2.95 ± 0.13 |

3.30 ± 0.20 |

| 25 °C |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

0.14 ± 0.02 |

0.17 ± 0.02 |

2.51 ± 0.11 |

2.98 ± 0.12 |

4.51 ± 0.21 |

| 45 °C |

0.14 ± 0.02 |

0.16 ± 0.02 |

0.32 ± 0.02 |

3.31 ± 0.11 |

5.61 ± 0.19 |

7.51 ± 0.25 |

| Ostrich oil |

4 °C |

0.09 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

0.12 ± 0.01 |

2.50 ± 0.10 |

2.51 ± 0.10 |

2.95 ± 0.13 |

3.30 ± 0.20 |

| 25 °C |

0.13 ± 0.01 |

0.14 ± 0.02 |

0.18 ± 0.01 |

2.55 ± 0.13 |

3.18 ± 0.10 |

4.89 ± 0.15 |

| 45 °C |

0.14 ± 0.02 |

0.17 ± 0.01 |

0.34 ± 0.02 |

3.50 ± 0.14 |

5.80 ± 0.19 |

8.91 ± 0.20 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).