Submitted:

27 December 2023

Posted:

28 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Poverty and poverty alleviation in Ghana

1.3. Role of Non-Timber Forest Products in Poverty Alleviation

1.4. Importance of poverty alleviation in forest communities

1.5. Aim of the Review

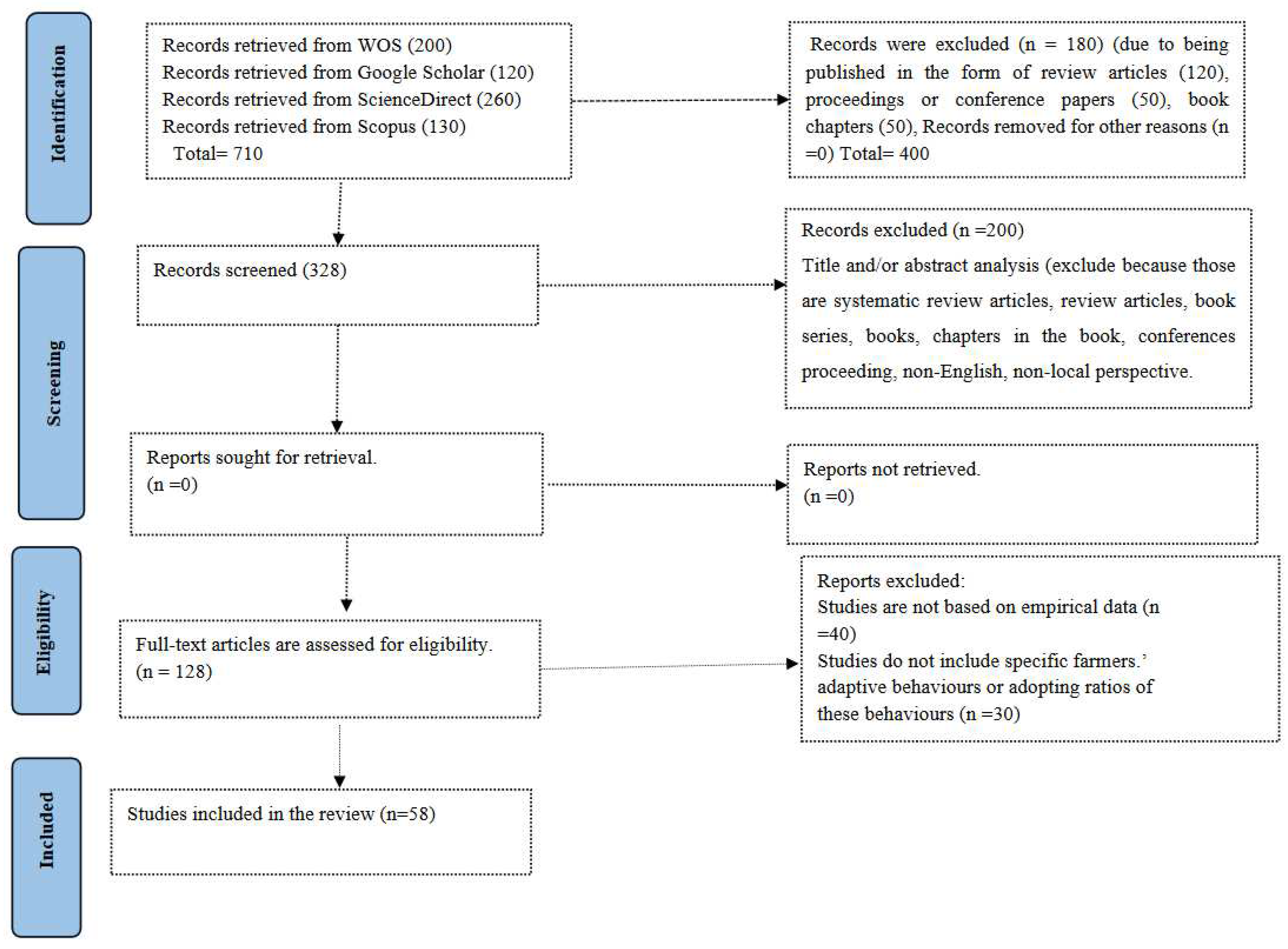

2. Methodology

2.1. Searches terms and languages

2.2. Searches

2.3. Database and Search Strategy

2.4. Data Abstraction and Analysis

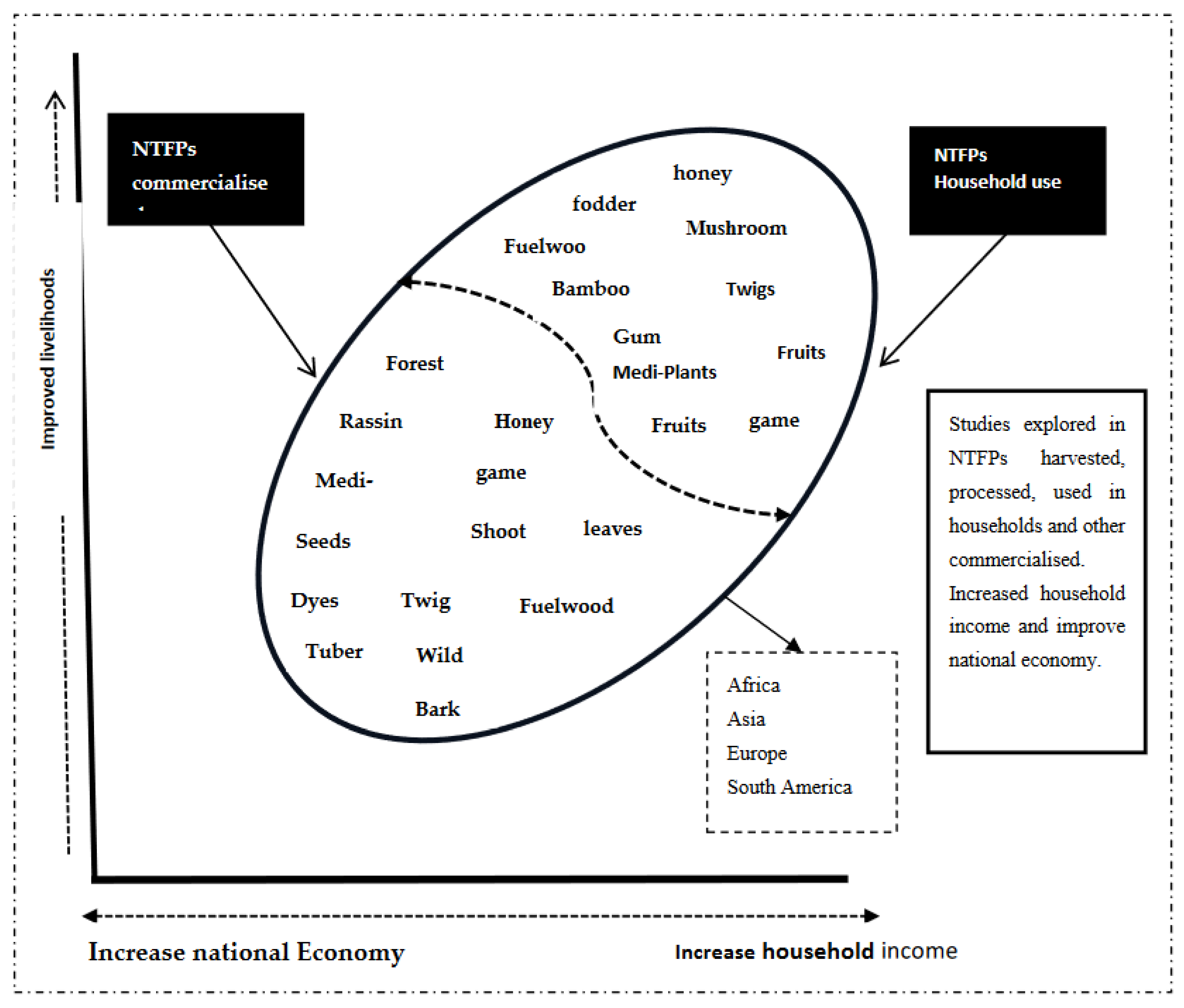

2.5. Analytical framework, of which the literature is analysed to NTFPs potential to alleviate poverty

3. Results

| Database | Total Result According to Stated Keywords | First Phase of Selection Filtered by Title |

Second Phase Selection Filtered by Abstract |

Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | 200 | 60 | 40 | 15 |

| Scopus | 130 | 50 | 20 | 10 |

| ScienceDirect | 260 | 35 | 25 | 19 |

|

Google Scholar Total |

120 |

14 | 14 |

14 58 |

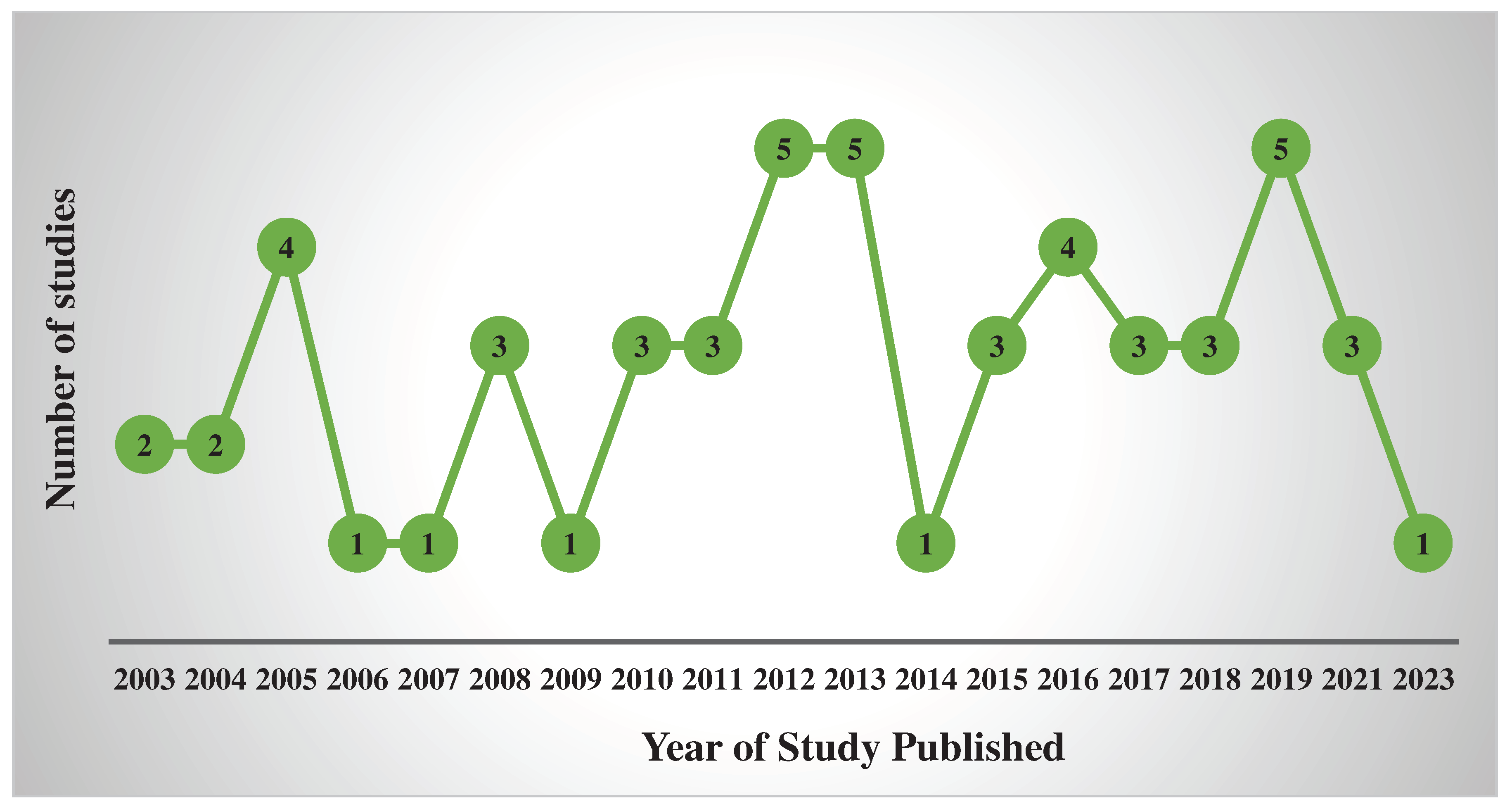

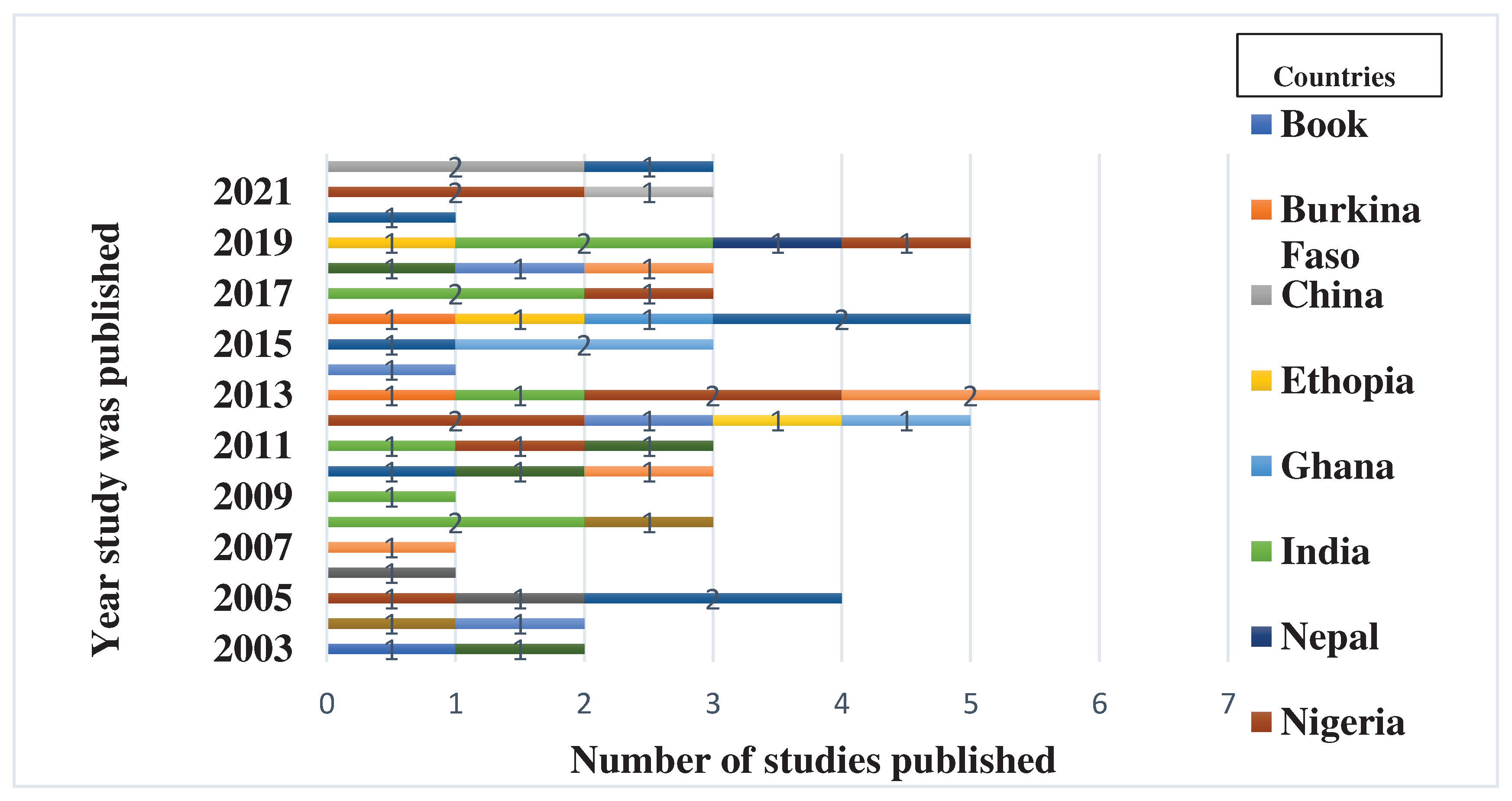

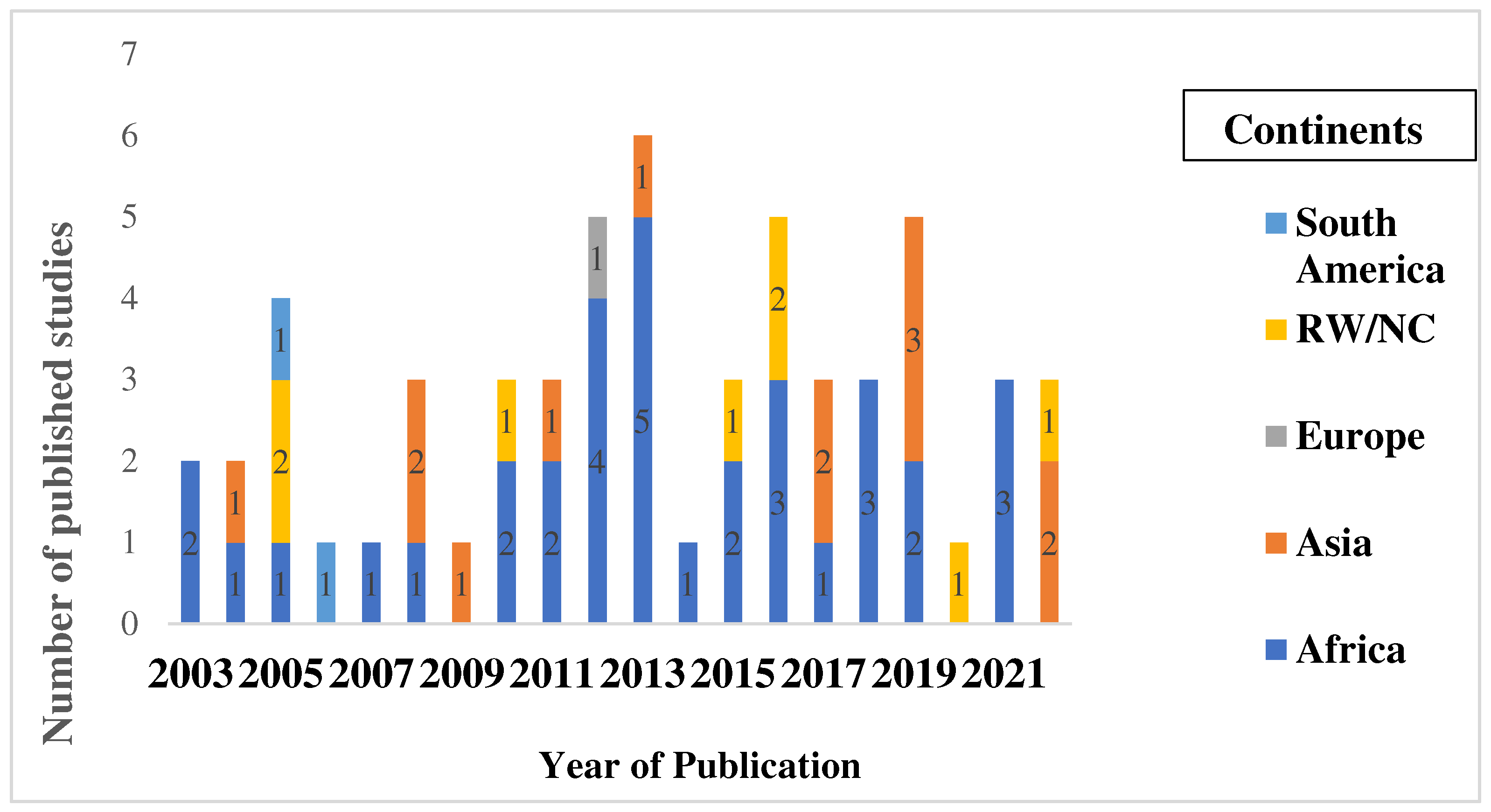

3.1. Distribution across regions and the study's timeframe

| Region Studied | Specific NTFPs collected | % Contribution of NTFPs to Household income | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tanzania | Firewood, fodder, honey. | 40 | (Giliba et al., 2010) |

| Myanmar | bamboo shoot, charcoal, firewood, broom grass | 43.7 | (Moe & Liu, 2016) |

| Ethiopia | Forest coffee, honey, spices (Ethiopian cardamom and long paper), fuelwood, medicinal and edible plants, bamboo | 47 | (Melaku et al., 2014) |

| Nepal | Fruits, leaves, seeds, shoots, bark, roots | 44–78 | (Rijal et al., 2011) |

| India | Medicinal plants, Mushrooms, Wild vegetables, Fuel wood, Gum resin and tannin, Millets, and seeds | 19–32 | (Saha & Sundriyal, 2012) |

| Uganda | Fuel wood, wild vegetables, Mushrooms, medicinal plants. | 26 | (Jagger, 2012) |

| Benin | Fodder, twigs, wild fruits, fuelwood, medicinal plants. | 39 | (Heubach et al., 2011) |

| Myanmar | Fuel, Fodder, Food, Medicinal plant, Wildlife | 50-55 | (Aung et al., 2015) |

| Cameroon | Fodder, medicinal plants, roots, tubers leave flowers, games dyes, etc. | 31 | (Ngwatung & Roger, 2013) |

| Contribution | Region | Products | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4- 60% total income | Tanzania, Ethiopia Nigeria, India, Zambia |

Honey, mushrooms, wood fuel fruits, leaves etc. | (Mulenga et al., 2012),(Nambiar, 2019; Nandi & Sarkar, 2021) |

| 40–60% of women’s income, and 15–20% of overall household income. |

Burkina Faso | NTFP | (Tincani, 2012) |

| 10–50% of harvester’s income in Sudan |

Sudan | Gums, resins, and wax | (Elmqvist & Olsson, 2006) |

| This income contributes to 32.6% of annual household subsistence |

Ethiopia | Gums, resins, Bamboo off farm crops and other NTFPs | (Mekonnen et al., 2013, 2014) |

| Between 19% and 95% of local income | South Africa | Honey, mushroom and other NTFPs | (S. Shackleton & Gumbo, 2010) |

| 70% of the cash income of rural household | Tanzania | NTFPs | (Makonda & Gillah, 2007) |

4. Discussions

4.1. Regions where NTFPs' potentials to alleviate poverty has been carefully studied

4.2. NTFPs, income generation and Poverty alleviation

4.3. Critiques

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pandey; Tripathi; Ashwani Kumar Non Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) for Sustained Livelihood: Challenges and Strategies. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, J.; Shah, K.K. Non-timber forest products and their role in the livelihoods of people of Nepal: A critical review. Grassroots Journal of Natural Resources 2020, 3, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Pandey, A.K. Positioning non-timber forest products on the development agenda. Forest Policy and Economics 2014, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Pullanikkatil, D. Considering the links between non-timber forest products and poverty alleviation. In Poverty Reduction Through Non-Timber Forest Products; Springer, 2019; pp. 15–28.

- Harbi, J.; Erbaugh, J.T.; Sidiq, M.; Haasler, B.; Nurrochmat, D.R. Making a bridge between livelihoods and forest conservation: Lessons from non timber forest products’ utilization in South Sumatera, Indonesia. Forest policy and economics 2018, 94, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melese, S.M. Importance of non-timber forest production in sustainable forest management, and its implication on carbon storage and biodiversity conservation in Ethiopia. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation 2016, 8, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety, Y.; Poudel, R.C.; Gurung, J.; Chettri, N.; Chaudhary, R.P. Traditional use and management of NTFPs in Kangchenjunga Landscape: implications for conservation and livelihoods. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 2016, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Van Bueren, E.T.L.; Ceccarelli, S.; Grando, S.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Ortiz, R. Diversifying food systems in the pursuit of sustainable food production and healthy diets. Trends in plant science 2017, 22, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mango, N.; Makate, C.; Mapemba, L.; Sopo, M. The role of crop diversification in improving household food security in central Malawi. Agriculture & Food Security 2018, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshpande, M.; Shackleton, C. Wild edible fruits: a systematic review of an under-researched multifunctional NTFP (non-timber forest product). Forests 2019, 10, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata Ngome, P.I.; Shackleton, C.; Degrande, A.; Tieguhong, J.C. Addressing constraints in promoting wild edible plants’ utilization in household nutrition: case of the Congo Basin forest area. Agriculture & food security 2017, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoodi, H.U.R.; Sundriyal, R.C. Richness of non-timber forest products in Himalayan communities—diversity, distribution, use pattern and conservation status. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine 2020, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mipun, P.; Bhat, N.A.; Borah, D.; Kumar, Y. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to healthcare and livelihood security among the Karbi tribe in Northeast India. Ecological Processes 2019, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asamoah, O.; Danquah, J.A.; Bamsiegwe, D.; Verter, N.; Acheampong, E.; Boateng, C.M.; Kuittinen, S.; Appiah, M.; Pappinen, A. The perception of locals on commercialisation and value addition of non-Timber Forest products in forest adjacent communities in Ghana. 2023.

- Lindberg, K.; Martvall, A.; Bastos Lima, M.G.; Franca, C.S.S. Herbal medicine promotion for a restorative bioeconomy in tropical forests: A reality check on the Brazilian Amazon. Forest Policy and Economics 2023, 155, 103058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Salim, J.; Anuar, S.N.; Omar, K.; Tengku Mohamad, T.R.; Sanusi, N.A. The Impacts of Traditional Ecological Knowledge towards Indigenous Peoples: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leßmeister, A.; Heubach, K.; Lykke, A.M.; Thiombiano, A.; Wittig, R.; Hahn, K. The contribution of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) to rural household revenues in two villages in south-eastern Burkina Faso. Agroforestry systems 2018, 92, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Paul, S.K. Sustaining the non-timber forest products (NTFPs) based rural livelihood of tribal’s in Jharkhand: Issues and challenges. Jharkhand Journal of Development and Management Studies 2016, 14, 6865–6883. [Google Scholar]

- De Roest, K.; Ferrari, P.; Knickel, K. Specialisation and economies of scale or diversification and economies of scope? Assessing different agricultural development pathways. Journal of Rural Studies 2018, 59, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedita, S.R.; De Noni, I.; Pilotti, L. Out of the crisis: an empirical investigation of place-specific determinants of economic resilience. European Planning Studies 2017, 25, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahenkan, A.; Boo, E. Improving the Supply Chain of Non-Timber Forest Products in Ghana. In Supply Chain Management - New Perspectives; Renko, S., Ed.; InTech, 2011 ISBN 978-953-307-633-1.

- Suleiman, M.S.; Wasonga, V.O.; Mbau, J.S.; Suleiman, A.; Elhadi, Y.A. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecol Process 2017, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, O.E.; Jimoh, K.A.; Oyewole, S.O.; Ayeni, A.E. Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) as a means of Livelihood and Safety Net among the Rurals in Nigeria: A Review. American Journal of Science and Management 2019, 6, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlén, C.B. Opportunities for making the invisible visible: Towards an improved understanding of the economic contributions of NTFPs. Forest Policy and Economics 2017, 84, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.; Opondo, M.; Tschakert, P.; Agrawal, A.; Eriksen, S.; Ma, S.; Perch, L.; Zakieldeen, S. Livelihoods and poverty. In Climate Change 2014 Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects; Cambridge University Press, 2014; pp. 793–832.

- Spicker, P. Poverty. In The Poverty of Nations; Policy Press, 2020; pp. 15–34 ISBN 1-4473-4334-4.

- Decerf, B. Combining absolute and relative poverty: income poverty measurement with two poverty lines. Social Choice and Welfare 2021, 56, 325–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, E.J. Poverty: a concept that is both absolute and relative because human beings are at once individual and social. Review of Social Economy 1990, 48, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, D.; Shepherd, A. Conceptualizing chronic poverty. World development 2003, 31, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, A.M.; Gordon, C. Strategic partnerships between universities and non-academic institutions for sustainability and innovation: Insights from the University of Ghana. Sustainability Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa I: Continental Perspectives and Insights from Western and Central Africa 2020, 245–278.

- Manuel, M.; Desai, H.; Samman, E.; Evans, M. Financing the end of extreme poverty; ODI Report, 2018.

- Newhouse, D.L.; Suarez-Becerra, P.; Evans, M. New estimates of extreme poverty for children. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mellish, J. Relative Poverty–a Measure of Inequality, not Poverty; Р, 2016.

- Müller, J.; Neuhäuser, C. Relative Poverty: On a Social Dimension of Dignity. Humiliation, Degradation, Dehumanization: Human Dignity Violated 2011, 159–172.

- Bhalla, A.S.; Lapeyre, F. Poverty and exclusion in a global world; springer, 2016; ISBN 1-349-27404-6.

- Carvalho, S.; White, H. Combining the quantitative and qualitative approaches to poverty measurement and analysis: the practice and the potential; World Bank Publications, 1997; Vol. 23; ISBN 0-8213-3955-9.

- Coudouel, A.; Hentschel, J.S.; Wodon, Q.T. Poverty measurement and analysis. A Sourcebook for poverty reduction strategies 2002, 1, 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sahn, D.E.; Stifel, D.C. Poverty comparisons over time and across countries in Africa. World development 2000, 28, 2123–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank in Ghana The World Bank Group aims to help Ghana towards creating a dynamic and diversified economy, greener job opportunities, for a more resilient and inclusive society.; 2023.

- OXFAM International The future is equal; 2023.

- World Bank Group (Poverty&Equity) Poverty & Equity Brief Ghana; 2022.

- Selase, A.E.; Lu, X. The impact of Ghana government poverty alleviation actions in the National poverty eradication programme. Available at SSRN 3118226 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, K.A. Growing apart: Ghana’s growing regional inequality since the adoption of poverty reduction strategies and the HIPC initiative (2000–2013). 2017.

- Issaka, Y.B. Non-timber Forest Products, Climate Change Resilience, and Poverty Alleviation in Northern Ghana. Strategies for building resilience against climate and ecosystem changes in sub-saharan Africa 2018, 179–192.

- Jaffee, S.; Henson, S.; Unnevehr, L.; Grace, D.; Cassou, E. The safe food imperative: Accelerating progress in low-and middle-income countries; World Bank Publications, 2018; ISBN 1-4648-1346-9.

- Mukul, S.A.; Rashid, A.Z.M.M.; Uddin, M.B.; Khan, N.A. Role of non-timber forest products in sustaining forest-based livelihoods and rural households’ resilience capacity in and around protected area: a Bangladesh study†. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2016, 59, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable livelihoods and rural development; Practical Action Publishing Rugby, 2015; ISBN 1-85339-875-6.

- Rahman, Md.H.; Roy, B.; Islam, Md.S. Contribution of non-timber forest products to the livelihoods of the forest-dependent communities around the Khadimnagar National Park in northeastern Bangladesh. Regional Sustainability 2021, 2, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S.; Puri, A.; Subba, M.; Dey, T.; Rai, P.; Shukla, G.; Pala, N.A. Value addition of non-timber forest products: prospects, constraints, and mitigation. Value Addition of Horticultural Crops: Recent Trends and Future Directions 2015, 213–244.

- Meinhold; Darr The Processing of Non-Timber Forest Products through Small and Medium Enterprises—A Review of Enabling and Constraining Factors. Forests 2019, 10, 1026. [CrossRef]

- Djoudi, H.; Vergles, E.; Blackie, R.R.; Koame, C.K.; Gautier, D. Dry forests, livelihoods and poverty alleviation: understanding current trends. International Forestry Review 2015, 17, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, G.; Yigezu, E. Women economic empowerment through non timber forest products in Gimbo District, south west Ethiopia. American Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 2015, 3, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepcha, L.D.; Shukla, G.; Moonis, M.; Vineeta; Bhat, J.A.; Kumar, M.; Chakravarty, S. Seasonal relation of NTFPs and socio-economic indicators to the household income of the forest-fringe communities of Jaldapara National Park. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2022, 42, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, N.R.; Choudhury, P.; Barbhuiya, R.A.; Singh, B. Importance of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) in rural livelihood: A study in Patharia Hills Reserve Forest, northeast India. Trees, Forests and People 2021, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, D.C.; Page, T.; Ota, L. Challenges and opportunities for inclusive value chains of niche forest products in small island developing states: Canarium nuts, sandalwood, and whitewood in Vanuatu. Journal of Rural Studies 2023, 100, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Güneralp, B. Understanding the Dynamics Between Forest Landscapes and Rural Livelihoods: A Case Study from Central India. In Forests as Complex Social and Ecological Systems: A Festschrift for Chadwick D. Oliver; Springer, 2022; pp. 295–320.

- Vaughan, B.; Gunson, B.; Murphy, B. Non-Timber Forest Products: Potential for Sustainable and Equitable Development In Ontario, Canada. Journal of Rural and Community Development 2023, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Bannor, R.K.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.; Mensah, P.O.; Derkyi, M.; Nassah, V.F. Entrepreneurial behaviour among non-timber forest product-growing farmers in Ghana: An analysis in support of a reforestation policy. Forest Policy and Economics 2021, 122, 102331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbi, J.; Cao, Y.; Milantara, N.; Mustafa, A.B. Assessing the Sustainability of NTFP-Based Community Enterprises: A Viable Business Model for Indonesian Rural Forested Areas. Forests 2023, 14, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D.; Pascucci, S.; Poldner, K.; Gartner, W.B. Learning “who we are” by doing: Processes of co-constructing prosocial identities in community-based enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing 2018, 33, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D. Re-inventing the commons: community forestry as accumulation without dispossession in Nepal. The Journal of Peasant Studies 2016, 43, 989–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, N.R. Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: A unifying foundation. 2015.

- World Bank World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work; Washington, DC: World Bank, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4648-1328-3.

- Boukhatem, J. Assessing the direct effect of financial development on poverty reduction in a panel of low-and middle-income countries. Research in International Business and Finance 2016, 37, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, N.; Khan, M.A.; Mohammad, K.D. Poverty alleviation by Zakah in a transitional economy: a small business entrepreneurial framework. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 2015, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, O.D. Impact of human capital development on poverty alleviation in Nigeria. International Journal of Economics & Management Sciences 2018, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanain, K.M. Integrating Zakah, Awqaf and IMF for poverty alleviation: Three models of Islamıc micro finance. Journal of Economic and Social Thought 2015, 2, 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- van Niekerk, A.J. Inclusive economic sustainability: SDGs and global inequality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauro, N.A.; Zauro, N.A.; Saad, R.A.J.; Sawandi, N. Enhancing socio-economic justice and financial inclusion in Nigeria: The role of zakat, Sadaqah and Qardhul Hassan. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 2020, 11, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizi, G. Marketised “educational desire” and the impetus for self-improvement: the shifting and reproduced meanings of higher education in contemporary China. Asian Studies Review 2019, 43, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, A.; Taylor, M. The short guide to community development; Policy Press, 2016; ISBN 1-4473-2783-7.

- Werhane, P.H.; Newton, L.H.; Wolfe, R. Alleviating poverty through profitable partnerships: Globalization, markets, and economic well-being; Routledge, 2020; ISBN 1-00-076601-2.

- Gore, C. The post-2015 moment: Towards Sustainable Development Goals and a new global development paradigm; Wiley Online Library, 2015; Vol. 27, pp. 717–732; ISBN 0954-1748.

- Osei-Kyei, R. A best practice framework for public-private partnership implementation for infrastructure development in Ghana. 2017.

- Hirons, M.; Robinson, E.; McDermott, C.; Morel, A.; Asare, R.; Boyd, E.; Gonfa, T.; Gole, T.W.; Malhi, Y.; Mason, J. Understanding poverty in cash-crop agro-forestry systems: evidence from Ghana and Ethiopia. Ecological Economics 2018, 154, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.S. Deforestation and its effect on livelihood patterns of forest fringe communities in the Asunafo North Municipality, 2014.

- Aryeetey, E.; McKay, A. Ghana: the challenge of translating sustained growth into poverty reduction. Delivering on the promise of pro-poor growth: Insights and Lessons from country experiences 2007, 1, 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Breisinger, C.; Diao, X.; Thurlow, J.; Al-Hassan, R.M. Agriculture for development in Ghana: New opportunities and challenges. 2008.

- Mulungu, K.; Manning, D.T. Impact of Weather Shocks on Food Security: How Effective are Forests as Natural Insurance? The Journal of Development Studies 2023, 59, 1760–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasona, M.; Adeonipekun, P.A.; Agboola, O.; Akintuyi, A.; Bello, A.; Ogundipe, O.; Soneye, A.; Omojola, A. Incentives for collaborative governance of natural resources: A case study of forest management in southwest Nigeria. Environmental Development 2019, 30, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med 2009, 151, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.; Fancourt, M.; Sandbrook, C.; Sibanda, M.; Giuliani, A.; Gordon-Maclean, A. Which components or attributes of biodiversity influence which dimensions of poverty? Environ Evid 2014, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Correa, P.C.; Cantera Kintz, J.R. Ecosystem-based adaptation for improving coastal planning for sea-level rise: A systematic review for mangrove coasts. Marine Policy 2015, 51, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanchini, M.; Steendahl, I.B.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Pruna, R.; Dupont, G.; Coutts, A.J.; Meyer, T.; McCall, A. Exercise-Based Strategies to Prevent Muscle Injury in Elite Footballers: A Systematic Review and Best Evidence Synthesis. Sports Med 2020, 50, 1653–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.Y.; Curtis, P.R.; Sone, B.J.; Hampton, L.H. Association of parent training with child language development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics 2019, 173, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; López-Cózar, E.D. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. Journal of informetrics 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.S.; Komoroske, L.M.; Grosholz, E.D. Trophic sensitivity of invasive predator and native prey interactions: integrating environmental context and climate change. Functional Ecology 2017, 31, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffril, H.A.M.; Ahmad, N.; Samsuddin, S.F.; Samah, A.A.; Hamdan, M.E. Systematic literature review on adaptation towards climate change impacts among indigenous people in the Asia Pacific regions. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 258, 120595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badini, O.S.; Hajjar, R.; Kozak, R. Critical success factors for small and medium forest enterprises: A review. Forest Policy and Economics 2018, 94, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Rodríguez, L.; Hogarth, N.J.; Zhou, W.; Xie, C.; Zhang, K.; Putzel, L. China’s conversion of cropland to forest program: a systematic review of the environmental and socioeconomic effects. Environmental Evidence 2016, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3 (2): 77–101; 2017.

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development; sage, 1998; ISBN 0-7619-0961-3.

- Giliba, R.A.; Lupala, Z.J.; Mafuru, C.; Kayombo, C.; Mwendwa, P. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to poverty alleviation and forest conservation in Mbulu and Babati Districts-Tanzania. Journal of Human Ecology 2010, 31, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, K.T.; Liu, J. Economic contribution of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) to rural livelihoods in the Tharawady District of Myanmar. Int. J. Sci 2016, 2, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaku, E.; Ewnetu, Z.; Teketay, D. Non-timber forest products and household incomes in Bonga forest area, southwestern Ethiopia. Journal of forestry research 2014, 25, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, A.; Smith-Hall, C.; Helles, F. Non-timber forest product dependency in the Central Himalayan foot hills. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2011, 13, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Sundriyal, R.C. Utilization of non-timber forest products in humid tropics: Implications for management and livelihood. Forest Policy and Economics 2012, 14, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagger, P. Environmental income, rural livelihoods, and income inequality in western Uganda. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 2012, 21, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heubach, K.; Wittig, R.; Nuppenau, E.-A.; Hahn, K. The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: A case study from northern Benin. Ecological Economics 2011, 70, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, P.S.; Adam, Y.O.; Pretzsch, J.; Peters, R. Distribution of forest income among rural households: A case study from Natma Taung national park, Myanmar. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 2015, 24, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwatung, A.; Roger, N. The role of non-timber forest products to communities living in the Northern periphery of the Korup National Park. Revista de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território 2013, 1, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, B.P.; Richardson, R.B.; Tembo, G. Non-timber forest products and rural poverty alleviation in Zambia; 2012.

- Nambiar, E.S. Tamm Review: Re-imagining forestry and wood business: pathways to rural development, poverty alleviation and climate change mitigation in the tropics. Forest Ecology and Management 2019, 448, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.; Sarkar, S. Non-Timber Forest Products Based Household Industries and Rural Economy—A Case Study of Jaypur Block in Bankura District, West Bengal (India). In Spatial Modeling in Forest Resources Management; Shit, P.K., Pourghasemi, H.R., Das, P., Bhunia, G.S., Eds.; Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 505–528. ISBN 978-3-030-56541-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tincani, L.S. Resilient livelihoods: adaptation, food security and wild foods in rural Burkina Faso, SOAS, University of London, 2012.

- Elmqvist, B.; Olsson, L. Livelihood diversification: continuity and change in the Sahel. GeoJournal 2006, 67, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, Z.; Worku, A.; Yohannes, T.; Bahru, T.; Mebratu, T.; Teketay, D. Economic contribution of gum and resin resources to household livelihoods in selected regions and the national economy of Ethiopia. 2013.

- Mekonnen, Z.; Worku, A.; Yohannes, T.; Alebachew, M.; Kassa, H. Bamboo Resources in Ethiopia: Their value chain and contribution to livelihoods. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 2014, 12, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Gumbo, D. Contribution of non-wood forest products to livelihoods and poverty alleviation. The dry forests and woodlands of Africa: managing for products and services 2010, 63–91.

- Makonda, F.B.S.; Gillah, P.R. Balancing wood and non-wood products in Miombo Woodlands. 2007.

- Peerzada, I.A.; Islam, M.A.; Chamberlain, J.; Dhyani, S.; Reddy, M.; Saha, S. Potential of NTFP Based Bioeconomy in Livelihood Security and Income Inequality Mitigation in Kashmir Himalayas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Y.O. An analytical framework for assessing the effect of income from non-timber forest products on poverty alleviation in Savannah region, Sudan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Menelisi, F. The role of non-timber forest products in the enhancement of rural livelihoods: a case of Nyautongi woodland management project in ward 8 of Chirumanzu District. 2014.

- Muhammad, S.S. Analysis of Economic Value, Utilization and Conservation of Selected Non-timber Forest Products in the Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria, University of Nairobi, 2017.

- Mahapatra, A.K.; Tewari, D.D. Importance of non-timber forest products in the economic valuation of dry deciduous forests of India. Forest Policy and Economics 2005, 7, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Shackleton, S.E.; Buiten, E.; Bird, N. The importance of dry woodlands and forests in rural livelihoods and poverty alleviation in South Africa. Forest policy and economics 2007, 9, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoh, S.O.; Amusa, T.O.; Azeez, I.O. Population distribution and threats to sustainable management of selected non-timber forest products in tropical lowland rainforests of south western Nigeria. Journal of forestry research 2013, 24, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaku, S.G.; Kabir, A.; Tukur, A.A.; Jimento, I.G. Wood fuel consumption in Nigeria and the energy ladder: A review of fuel wood use in Kaduna State. Journal of Petroleum Technology and Alternative Fuels 2013, 4, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Onuche, P. Non-timber forest products (NTFPs): a pathway for rural poverty reduction in Nigeria. International Journal of Economic Development Research and Investment 2011, 2, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mbuvi, D.; Boon, E. The livelihood potential of non-wood forest products: The case of Mbooni Division in Makueni District, Kenya. Environment, Development and sustainability 2009, 11, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, M.; Morse-Jones, S.; Posen, P.; Swetnam, R.D.; Balmford, A.; Bateman, I.J.; Burgess, N.D.; Chamshama, S.A.O.; Fisher, B.; Freeman, T. The importance of local forest benefits: Economic valuation of Non-Timber Forest Products in the Eastern Arc Mountains in Tanzania. Global Environmental Change 2014, 24, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, I.R.; Stephenson, S.L.; Buchanan, P.K.; Wang, Y.; Cole, A.L. Edible and poisonous mushrooms of the world; Timber Press, 2003; ISBN 0-88192-586-1.

- Shanley, P.; Pierce, A.R.; Laird, S.A.; Binnqüist, C.L.; Guariguata, M.R. From lifelines to livelihoods: non-timber forest products into the twenty-first century. Tropical forestry handbook 2015, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashares, J.S.; Arcese, P.; Sam, M.K.; Coppolillo, P.B.; Sinclair, A.R.; Balmford, A. Bushmeat hunting, wildlife declines, and fish supply in West Africa. Science 2004, 306, 1180–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargeot, C.; Drouet-Hoguet, N.; Le Bel, S. The role of bushmeat in urban household consumption: Insights from Bangui, the capital city of the Central African Republic. BOIS & FORETS DES TROPIQUES 2017, 332, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, R.; Bull, G. Economic shocks and Miombo woodland resource use: a household level study in Mozambique. Department of Forest Resource Management, University of British Columbia 2008, 80–105.

- Laird, S.A.; Wynberg, R.P. Locating responsible research and innovation within access and benefit sharing spaces of the convention on biological diversity: the challenge of emerging technologies. NanoEthics 2016, 10, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Fei, B.; Das, M.; Jiang, Z. Bamboo and rattan: Nature-based solutions for sustainable development. The Innovation 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigit, A.S. International Economics: Rattan. 2020.

- Huang, L.; Chen, K.; Zhou, M.; Nuse, B. Gravity models of china’s bamboo and rattan products exports: Applications to trade potential analysis. Forest Products Journal 2019, 69, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sastry, C.B. The international network for bamboo and rattan. UNASYLVA-FAO- 1999, 48–53.

- Nataliya, S. Non-wood forest products for livelihoods. Bosque (Valdivia) 2012, 33, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María Castro, L.; Encalada, D.; Rodrigo Saa, L. Non-Timber Forest Products as an Alternative to Reduce Income Uncertainty in Rural Households. In Sustainable Rural Development Perspective and Global Challenges; Özçatalbaş, O., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2023 ISBN 978-1-80355-420-4.

- Shackleton, C.M.; Garekae, H.; Sardeshpande, M.; Sinasson Sanni, G.; Twine, W.C. Non-timber forest products as poverty traps: Fact or fiction? Forest Policy and Economics 2024, 158, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Y.O.; Pretzsch, J.; Pettenella, D. An Analytical Framework for Assessing the Effect of Income from Non-timber Forest Products on Poverty Alleviation in Savannah Region, Sudan. uofkjas 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, Y.O.; Pretzsch, J.; Pettenella, D. Contribution of Non-Timber Forest Products livelihood strategies to rural development in drylands of Sudan: Potentials and failures. Agricultural Systems 2013, 117, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.M.; Mundial, B. The ecology and management of non-timber forest resources; World Bank Washington, DC, 1996; ISBN 0-8213-3619-3.

- Neumann, R.P.; Hirsch, E. Commercialisation of non-timber forest products: review and analysis of research. 2000.

- Angelsen, A.; Wunder, S. Exploring the forest-poverty link. CIFOR occasional paper 2003, 40, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- FAO State of the world’s forests 2003. Part II. Selected current issues in the forest sector.; Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) Rome, 2003.

| Databases | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | Non-timber forest products” OR “NTFPs*” AND “Potential” AND “poverty” OR “livelihood” OR “Improvement” OR “Alleviation” AND “forest communities” OR “Locals” OR “Fringe” OR “Adjacent” |

| Scopus | Non-timber forest products” OR “NTFPs*” AND “Potential” AND “poverty” OR “livelihood” OR “Improvement” OR “Alleviation” AND “forest communities” OR “Locals” OR “Fringe” OR “Adjacent” |

| ScienceDirect | Non-timber forest products” OR “NTFPs*” AND “Potential” AND “poverty” OR “livelihood” OR “Improvement” OR “Alleviation” AND “forest communities” OR “Locals” OR “Fringe” OR “Adjacent” |

| Google Scholar | Non-timber forest products” OR “NTFPs*” AND “Potential” AND “poverty” OR “livelihood” OR “Improvement” OR “Alleviation” AND “forest communities” OR “Locals” OR “Fringe” OR “Adjacent” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).