Submitted:

27 December 2023

Posted:

27 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis, Purification, and Preparation of Peptides

2.2. Calculation of Peptide Physicochemical and Structural Parameters

2.3. Bacterial Strains and Inoculum Standardization

2.4. Antibacterial Experiments

2.5. Cell Culture

2.6. MTT Assay and Cytotoxicity Analysis

2.7. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

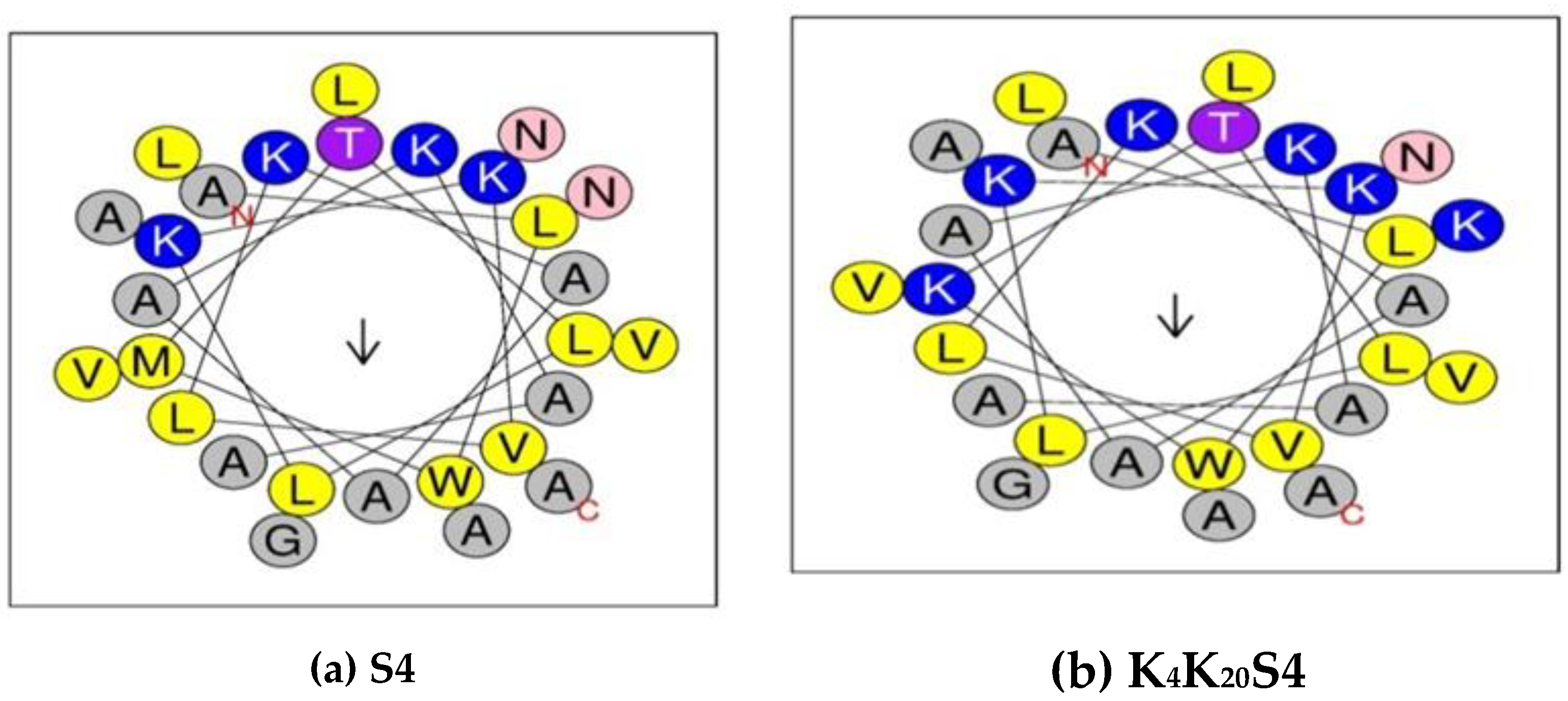

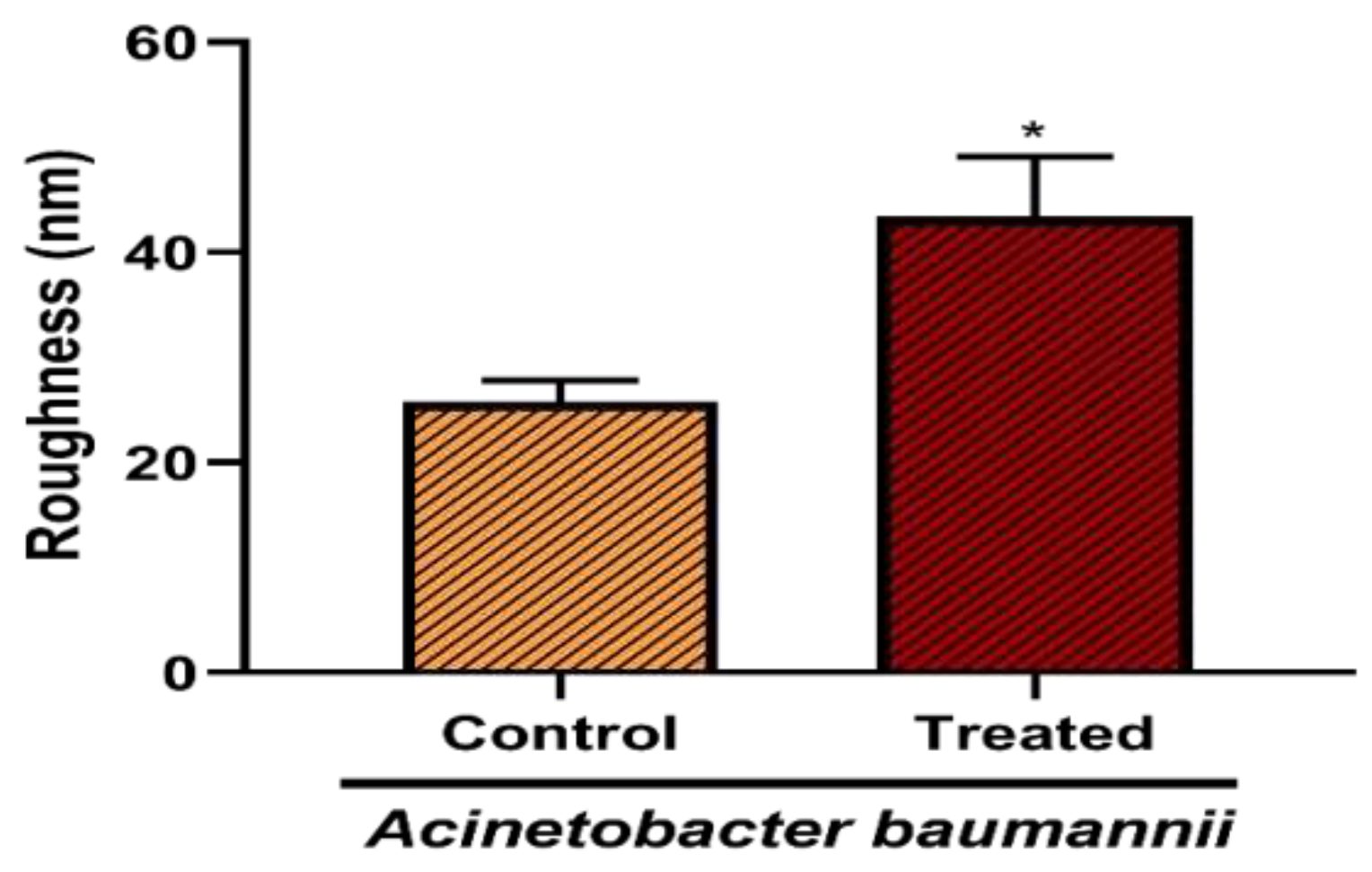

3.1. Design of Dermaseptin S4 and B2 Derivatives

3.2. Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Peptides

3.3. In Vitro Toxicity of Dermaseptin and Derivatives against HEp-2 Cells

3.4. Antibacterial Activity of Dermaseptins Derivatives against Acinetobacter baumannii

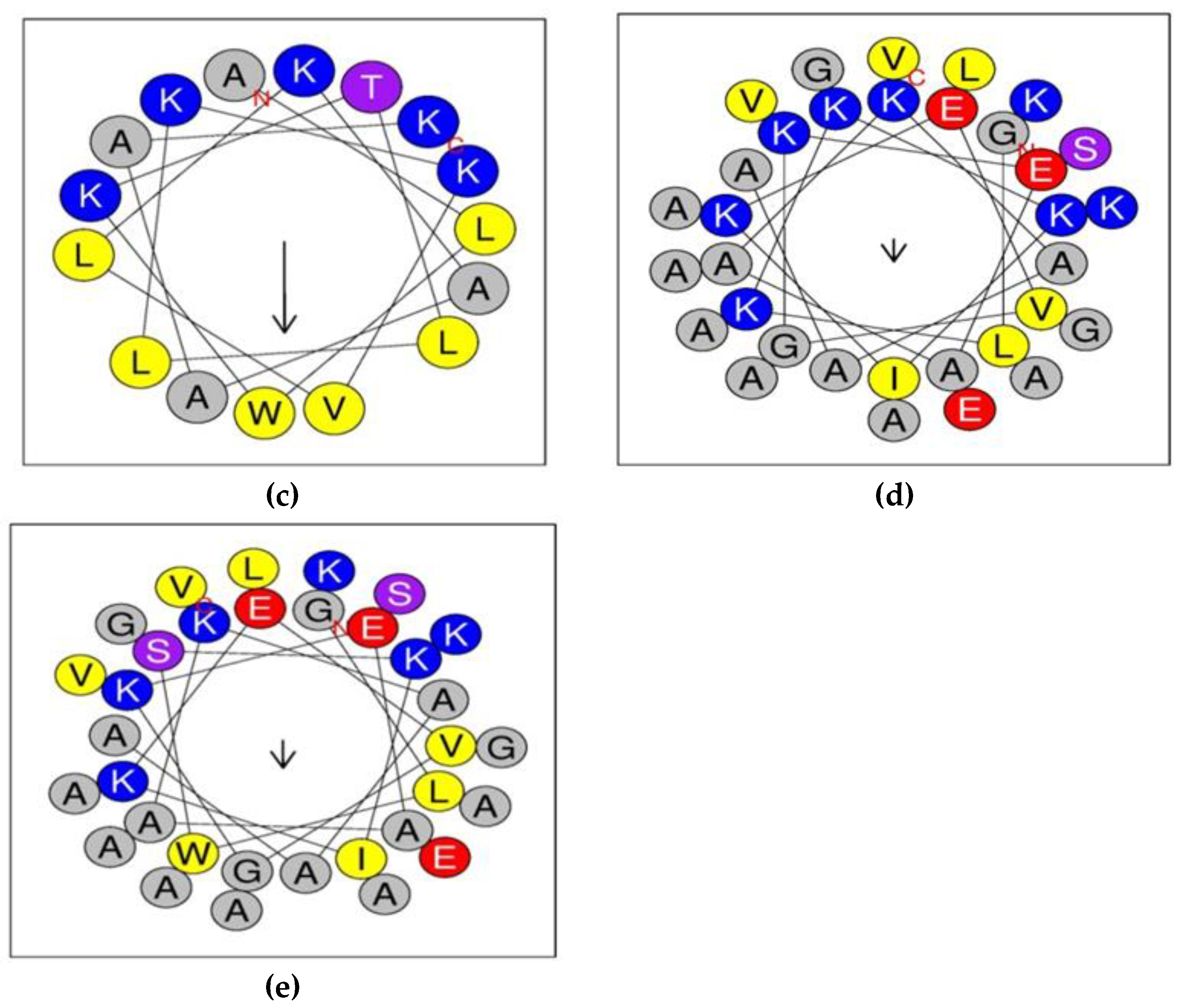

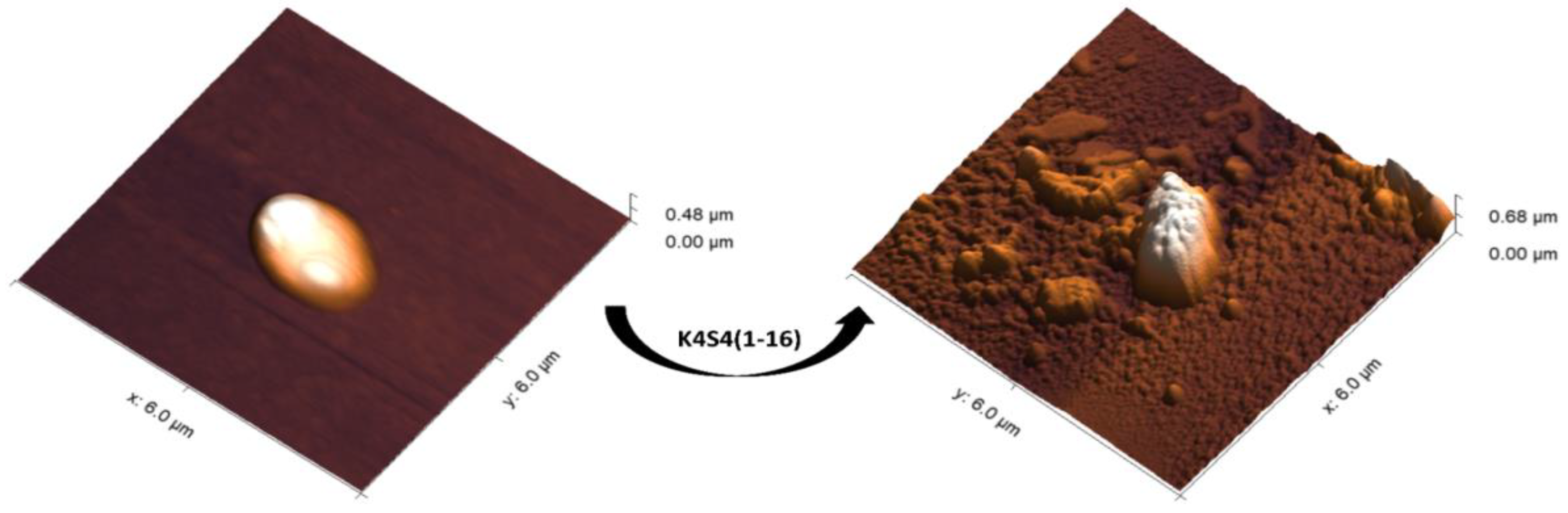

3.5. The Morphological Effect of K4S4(1-16) on the Treated Bacteria

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Funding statement

Conflicts of Interest

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| HAIs | Healthcare-Associated infections |

| MDR | Multi-resistant bacterial strains |

| MTT | (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CAUTIs | Catheter-associated urinary tract infections |

| HAPs | Hospital-acquired pneumonias |

| BSIs | Bloodstream infections |

| SSIs | Surgical site infections |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial peptides |

| DS | Dermaseptin |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| Pfp | Fmoc-aminoacidpentafluorophenyl |

| Dhbt | 3-hydroxy- 2,3-dehydro-4-oxo-benzotriazine |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| MHA | Mueller Hinton Agar |

| DMEM | Modified Eagle Medium |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| Alg NPs | Alginate nanoparticles |

References

- Monegro, A.F.; Muppidi, V.; Regunath, H. Hospital-Acquired Infections. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL,. StatPearls Publishing. 2023. PMID: 28722887.

- Naveed, S.; Sana, A.; Sadia, H.; Qamar, F.; Aziz, N. Nosocomial Infection: Causes Treatment and Management. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. Res. 2019, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larypoor, M.; Frsad, S. Evaluation of nosocomial infections in one of hospitals of Qom, 2008. Iran. J. Med. Microbiol. Persian. 2011, 5, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olise, C.C.; Simon-Oke, I.A. Fomites: Possible vehicle of nosocomial infections. J. Pub. Health. Catalog. 2018, 1, 16–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5- Du, Q. Zhang, D. Hu, W. Li, X. Xia, Q. Wen, T. Jia, H. Nosocomial infection of COVID-19: A new challenge for healthcare professionals (Review,. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 47, 31. [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.A.; Baig, F.K.; Mehboob, R. Nosocomial infections: epidemiology, prevention, control and surveillance. Asian. Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017, 7, 478–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houang, E.T.S. Sormunen, R.T. Lai, L. Chan, C.Y. Leong, A.S.Y. Effect of desiccation on the ultrastructural appearances of Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter lwoffii. J. Clin. Path. 1998, 51, 786–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS, Report: Early Implementation 2016–2017, World Health, Organization, 2017. ISBN 978-92-4-151344-9. (Accessed 20 November 2023.

- Talreja, D.; Muraleedharan, C.; Gunathilaka, G.; Zhang, Y.; Kaye, K.S.; Walia, S.K.; Kumar, A. Virulence properties of multidrug resistant ocular isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Curr. Eye. Res. 2014, 39(7), 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Chowdhury, G.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Dutta, S.; Basu, S. ; Convergence of Biofilm Formation and Antibiotic Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 793615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ia, K.; Diene, S.M.; Goderdzishvili, M.; Rolain, J.M. Molecular detection of OXA carbapenemase genes in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Iraq and Georgia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2011, 38, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidian, M.; Nigro, S.J. Emergence, molecular mechanisms and global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Genom. 2019, 5, e000306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Chai, D.; Wang, R.; Liang, B.; Bai, N. Colistin resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii: clinical reports, mechanisms and antimicrobial strategies. J. Antimicrob. Chemoth. 2012, 67, 1607–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon-Venezia, S.; Leavitt, A.; Carmeli, Y. High tigecycline resistance in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemoth. 2007, 59, 772–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisinger, E.; Vargas-Cuebas, G.; Mortman, N.J.; Syal, S.; Dai, Y.; Wainwright, E.L.; Lazinski, D.; Wood, S.; Zhu, Z.; Anthony, J. et al. The Landscape of Phenotypic and Transcriptional Responses to Ciprofloxacin in Acinetobacter baumannii: Acquired Resistance Alleles Modulate Drug-Induced SOS Response and Prophage Replication. mBio. 2019, 10, e01127–e01219. [CrossRef]

- Gellings, P.S.; Wilkins, A.A.; Morici, L.A. Recent Advances in the Pursuit of an Effective Acinetobacter baumannii Vaccine. Pathogens. 2020, 9, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, A.A.; Ren, D. Antimicrobial peptides. Pharmaceuticals. 2013, 6, 1543–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangi, J. Hao, X. Lai, R. Zhang, Z.Y. Antimicrobial peptides: New hope in the war against multidrug resistance. Zool. Res. 2019, 40, 488–505. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.L.; Hancock, R.E. Cationic host defense (antimicrobial, peptides. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006, 18, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargraves, S. Greub, G. Jacquier, N. Peptides antimicrobiens: une alternative aux antibiotiques? Education. 2020, 1, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mor, A. Nguyen, V.H. Delfour, A. Migliore-Samour, D. Nicolas, P. Isolation, amino acid sequence, and synthesis of dermaseptin, a novel antimicrobial peptide of amphibian skin. Biochemistry, 1991; 30, 8824–8830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiche, M. Ladram, A. Nicolas, P. A consistent nomenclature of antimicrobial peptides isolated from frogs of the subfamily Phyllomedusinae. Peptides. 2008, 29, 2074–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairi, A. Tangy, F. Saadi, S. Hani, K. In vitro activity of dermaseptin S4 derivatives against genital infections pathogens. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 50, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, P. El Amri, C. The dermaseptin superfamily: a gene-based combinatorial library of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009, 1788, 1537–1550. [CrossRef]

- Shai, Y. Mode of action of membrane active antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 2002, 66, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, R.; Dagan, A.; Mor, A. Structure-activity relationship study of antimicrobial dermaseptin S4 showing the consequences of peptide oligomerization on selective cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 4230–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiche, M.; Ducancel, F.; Mor, A.; Boulain, J.; Menez, A.; Nicolas, P. Precursors of vertebrate peptide antibiotics dermaseptin b and adenoregulin have extensive sequence identities with precursors of opioid peptides dermorphin, dermenkephalin, and deltorphins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 17847–17852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, J.W.; Caceres, J.; Moni, R.W.; Gusovsky, F.; Moos, M.; Seamon, K.B.; Milton, K.; Myers, C.W. Frog secretions and hunting magic in the upper Amazon: Identification of a peptide that interacts with an adenosine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 10960–10963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazime, N.; Belguesmia, Y.; Barras, A.; Amiche, M.; Boukherroub, R.; Drider, D. Enhanced Antibacterial Activity of Dermaseptin through Its Immobilization on Alginate Nanoparticles—Effects of Menthol and Lactic Acid on Its Potentialization. Antibiotics. 2022, 11, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanth, C.; Abbassi, F.; Lequin, O.; Ayala-Sanmartin, J.; Ladram, A.; Nicolas, P.; Amiche, M. Mechanism of antibacterial action of dermaseptin B2: interplay between helix-hinge-helix structure and membrane curvature strain. Biochemistry. 2009, 48, 313–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, E.J.H.; Dekker, D.; Amiche, M. Dermaseptins, Multifunctional Antimicrobial Peptides: A Review of Their Pharmacology, Effectivity, Mechanism of Action, and Possible Future Directions. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautier, R.; Douguet, D.; Antonny, B.; Drin, G. HELIQUEST: a web server to screen sequences with specific α-helical properties. Bioinformatics. 2008, 24, 2101–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Escamilla, A.M.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.; Serrano, L. Prediction of sequence-dependent and mutational effects on the aggregation of peptides and proteins. Nat. Biotec. 2004, 22, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, V.; Serrano, L. Elucidating the folding problem of helical peptides using empirical parameters. Nat. Struc. Mol. Bio. 1994, 1, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, CLSI Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; approved standard— 28th ed M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2018, Wayne, PA.

- de Araujo, A.R.; Quelemes, P.V.; Perfeito, M.L.; de Lima, L.I.; Sá, M.C.; Nunes, P.H.; Joanitti, G.A.; Eaton, P.; Soares, M.J.; de Souza de Almeida Leite, J.R. Antibacterial, antibiofilm and cytotoxic activities of Terminalia fagifolia Mart. extract and fractions. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2015, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efron, L.; Dagan, A.; Gaidukov, L.; Ginsburg, H.; Mor, A. Direct interaction of dermaseptin S4 aminoheptanoyl derivate with intraerythrocytic malaria parasite leading to increased specific antiparasitic activity in culture. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 24067–24072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustanovich, I.; Shalev, D.E.; Mikhlin, M.; Gaidukov, L.; Mor, A. Structural requirements for potent versus selective cytotoxicity for antimicrobial dermaseptin S4 derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 16941–16951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Z.Y.; Wiradharma, N.; Yang, Y.Y. Strategies employed in the design and optimization of synthetic antimicrobial peptide amphiphiles with enhanced therapeutic potentials. Adv. Drug. Deliv. 2014, 78, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wei, D.; Yan, P.; Zhu, X.; Shan, A.; Bi, Z. Characterization of cell selectivity, physiological stability and endotoxin neutralization capabilities of alpha-helix-based peptide amphiphiles. Biomaterials. 2015, 52, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lyu, X.; Na, D.; Shan, A. Antimicrobial activity, improved cell selectivity and mode of action of short PMAP-36-derived peptides against bacteria and Candida. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, N.; Zhu, X.; Chou, S.; Shan, A.; Li, W.; Jiang, J. Antimicrobial potency and selectivity of simplified symmetric-end peptides. Biomaterials. 2014, 35, 8028–8039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zoggel, H.; Carpentier, G.; Dos Santos, C.; Hamma-Kourbali, Y.; Courty, J.; Amiche, M.; Delbé, J. Antitumor and angiostatic activities of the antimicrobial peptide dermaseptin B2. PLoS. One. 2012, 7, e44351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irazazabal, L.N.; Porto, W.F.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Casale, S.; Humblot, V.; Ladram, A.; Franco, O.L. Selective amino acid substitution reduces cytotoxicity of the antimicrobial peptide mastoparan. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016, 1858, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navon-Venezia, S.; Feder, R.; Gaidukov, L.; Carmeli, Y.; Mor, A. Antibacterial properties of dermaseptin S4 derivatives with in vivo activity. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2002, 46, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugliak, M.; Feder, R.; Zolotarev, V.Y.; Gaidukov, L.; Dagan, A.; Ginsburg, H.; Mor, A. Antimalarial activities of dermaseptin S4 derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2442–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.; Neidle, A.; Marks, N. Significant differences in the degradation of pro-leu-gly-nH2 by human serum and that of other species (38484). Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1975, 148, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.Y.; Oh, J.E.; Lee, K.H. Effect of D-amino acid substitution on the stability, the secondary structure, and the activity of membrane-active peptide. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 58, 1775–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, A.; Papo, N.; Shai, Y. In vitro activity and potency of an intravenously injected antimicrobial peptide and its DL amino acid analog in mice infected with bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2004, 48, 3127–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, S.; Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, R.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; et al. Antimicrobial activity and stability of the D-amino acid substituted derivatives of antimicrobial peptide polybia-MPI. AMB. Express. 2016, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaezi, Z.; Bortolotti, A.; Luca, V.; Perilli, G.; Mangoni, M.L.; Khosravi-Far, R.; Bobone, S.; Stella, L. Aggregation determines the selectivity of membrane-active anticancer and antimicrobial peptides: The case of killer FLIP. Biochim. Biophys Acta. Bio. 2020, 1, 183107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Musaimi, O.; Valenzo, O.M.M.; Williams, D.R. Prediction of peptides retention behavior in reversed-phase liquid chromatography based on their hydrophobicity. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, e2200743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.; Weiss, R.M.; Terwilliger, T.C. The hydrophobic moment detects periodicity in protein hydrophobicity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1984, 81, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.; Weiss, R.M.; Terwilliger, T.C. The helical hydrophobic moment: a measure of the amphiphilicity of a helix. Nature. 1982, 299, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison, S.R.; Phoenix, D.A. Influence of C-terminal amidation on the efficacy of modelin-5. Biochemistry. 2011, 50, 1514–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, R.; Zhu, X.; Tu, Y.; Wu, J.; Landry, M.P. Activity of Antimicrobial Peptide Aggregates Decreases with Increased Cell Membrane Embedding Free Energy Cost. Biochemistry. 2018, 57, 2606–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M.; Sothiselvam, Sh.; Lu, T.K.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C. Peptide Design Principles for Antimicrobial Applications. J. Mol. Bio. 2019, 431, 3547–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; He, L.; Li, G.; Zhai, N.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Y. Role of helicity of α-helical antimicrobial peptides to improve specificity. Prot. Cell. 2014, 5, 631–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezetsky, I.; Tossi, A. Alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides—using a sequence template to guide structure–activity relationship studies. Bioch. Biophy. Acta. 2006, 1758, 1436–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.H.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Park, T.I.; Kim, H.J.; Hyun, S.H.; Kim, S.A.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, J.C. Outer membrane protein 38 of Acinetobacter baumannii localizes to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis of epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 1127–11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, Y.C.; et al. Acinetobacter baumannii invades epithelial cells and outer membrane protein A mediates interactions with epithelial cells. BMC. Microbiol. 2008, 8, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belaid, A.; Aouni, M.; Khelifa, R.; Trabelsi, A.; Jemmali, M.; Hani, K. In vitro antiviral activity of dermaseptins against herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Med. Virol. 2002, 66, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourkhede, D.P.; Bhoomika, S.; Pathak, R.; Yadav, J.P.; Nishanth, D.; Vergis, J.; Malik, S.V.S.; Barbuddhe, S.B.; Rawool, D.B. Antimicrobial efficacy of Cecropin A (1-7,- Melittin and Lactoferricin (17-30, against multi-drug resistant Salmonella Enteritidis. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 147, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sruthy, K.S.; Nair, A.; Antony, S.P.; Puthumana, J.; Singh, I.S.B.; Philip, R. A histone H2A derived antimicrobial peptide, Fi-Histin from the Indian White shrimp, Fenneropenaeus indicus: Molecular and functional characterization. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2019, 92, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zairi, A.; Serres, C.; Tangy, F.; Jouannet, P.; Hani, K. In vitro spermicidal activity of peptides from amphibian skin: dermaseptin S4 and derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 266–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaid, A.; Braiek, A.; Alibi, S.; Hassen, W.; Beltifa, A.; Nefzi, A.; Mansour, H.B. Evaluating the effect of dermaseptin S4 and its derivatives on multidrug-resistant bacterial strains and on the colon cancer cell line SW620. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 40908–40916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorin, C.; Saidi, H.; Belaid, A.; Zairi, A.; Baleux, F.; Hocini, H.; Bélec, L.; Hani, K.; Tangy, F. The antimicrobial peptide dermaseptin S4 inhibits HIV-1 infectivity in vitro. Virology. 2005, 334, 264–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, F.; Perl, T.; Schulze, M.H.; Binder, L. Personalised beta-lactam therapy: basic principles and practical approach. Laboratoriums. Medizin. 2016, 40, 385397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MerremRM, IV (meropenem for injection,: US Prescribing Information, AstraZeneca. 2007.

- Steffens, N.A.; Zimmermann, E.S.; Nichelle, S.M.; Brucker, N. Meropenem use and therapeutic drug monitoring in clinical practice: a literature review. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021, 46, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Vasil, A.I.; Vasil, M.L.; Hodges, R.S. “Specificity Determinants” Improve Therapeutic Indices of Two Antimicrobial Peptides Piscidin 1 and Dermaseptin S4 Against the Gram-negative Pathogens Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pharmaceuticals. 2014, 7, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strahilevitz, J.; Mor, A.; Nicolas, P.; Shai, Y. Spectrum of antimicrobial activity and assembly of dermaseptin-b and its precursor form in phospholipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1994, 33, 10951–10960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zairi, A.; Ferrieres, L.; Latour-Lambert, P.; Beloin, C.; Tangy, F.; Ghigo, J.M.; et al. In vitro activities of dermaseptins K4S4 and K4K20S4 against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa planktonic growth and biofilm formation. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2014, 58, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Li, L.; Xi, X.; Wu, D.; Zhou, M.; et al. Discovery of phylloseptins that defense against gram-positive bacteria and inhibit the proliferation of the non-small cell lung cancer cell line, from the skin secretions of Phyllomedusa frogs. Molecules. 2017, 22, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Ding, X.; Li, W.; Lu, T.; Ma, C.; Xi, X.; et al. Discovery of two skin derived dermaseptins and design of a TAT-fusion analogue with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and low cytotoxicity on healthy cells. Peer. J. 2018, 6, e5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santajit, S.; Indrawattana, N. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2475067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Shea, P. Intermolecular interactions with/within cell membranes and the trinity of membrane potentials: kinetics and imaging. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003, 31, 990e996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Hung, A.; Li, R.; Barlow, A.; Singleton, W.; Matthyssen, T.; Sani, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Wade, J.D.; O'Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Li, W. Systematic comparison of activity and mechanism of antimicrobial peptides against nosocomial pathogens. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 231, 114135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouny, Y.; Rapaport, D.; Mor, A.; Nicolas, P.; Shai, Y. Interaction of antimicrobial dermaseptin and its fluorescently labeled analogues with phospholipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1992, 31, 12416–12423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, M.G.; Ferrari, E.; Goddard, A.D.; Lancaster, L.; Sanderson, P.; Miller, C. Mechanistic and phenotypic studies of bicarinalin, BP100 and colistin action on Acinetobacter baumannii. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peptides | Sequence* | Parameters** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | MW |

Net Charge |

H | Aggregation | μH | α-Helix % | ||

| S4 (Native) | ALWMTLLKKVLKAAAKAALNAVLVGANA | 28 | 2.850 | +4 | 0.544 | 183.33 | 0.248 | 16.55 |

| K4K20S4 | ALWKTLLKKVLKAAAKAALKAVLVGANA | 28 | 2.861 | +6 | 0.451 | 112.02 | 0.246 | 11.8 |

| K4S4(1-16) | ALWKTLLKKVLKAAAK | 16 | 1.782 | +5 | 0.426 | 0 | 0.526 | 2.41 |

| B2 (Native) | GLWSKIKEVGKEAAKAAAKAAGKAALGAVSEAV | 33 | 3.181 | +3 | 0.199 | 9.681 | 0.204 | 10.02 |

| K3K4B2 | GLKKKIKEVGKEAAKAAAKAAGKAALGAVSEAV | 33 | 3.164 | +5 | 0.072 | 9.681 | 0.159 | 9.85 |

|

Peptides |

CC50 Hep-2 cells (μg/ml) |

Acinetobacter baumannii MIC ( μg/ml) |

Acinetobacter baumannii MBC ( μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S4 | 16.51 | 12.5 | 25 |

| K4S4(1-16) | 68.9 | 6.25 | 12.5 |

| K4K20S4 | 75.71 | 3.125 | 6.25 |

| B2 | 30.4 | 12.5 | 25 |

| K3K4B2 | 61.25 | 6.25 | 12.5 |

| meropenem | ND | 32 | 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).