Submitted:

23 December 2023

Posted:

25 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Optical analysis

2.3. In situ Reflectance Spectroscopy (ISRS, Corg(chlorins))

2.4. Geochemistry

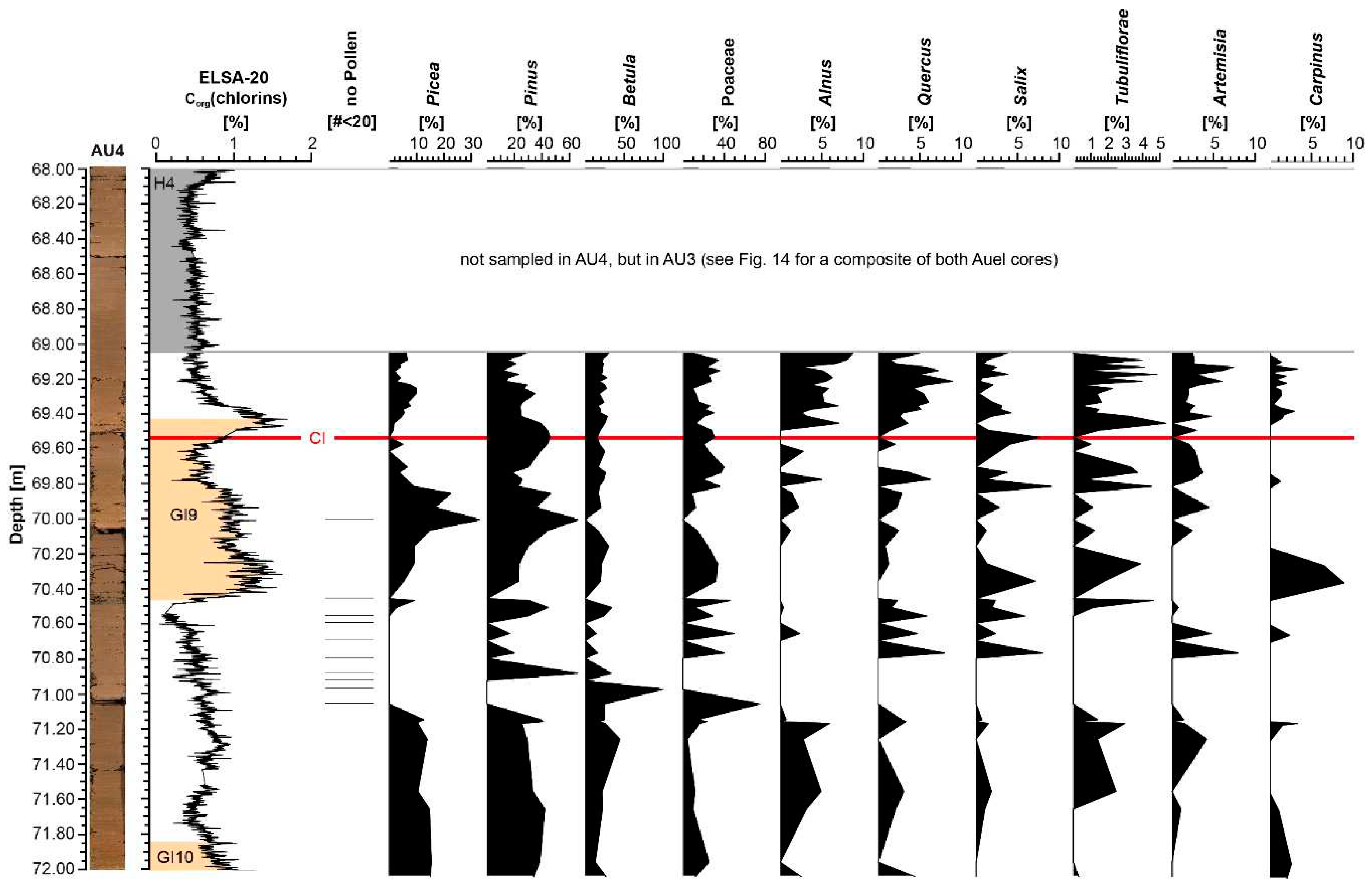

2.5. Pollen

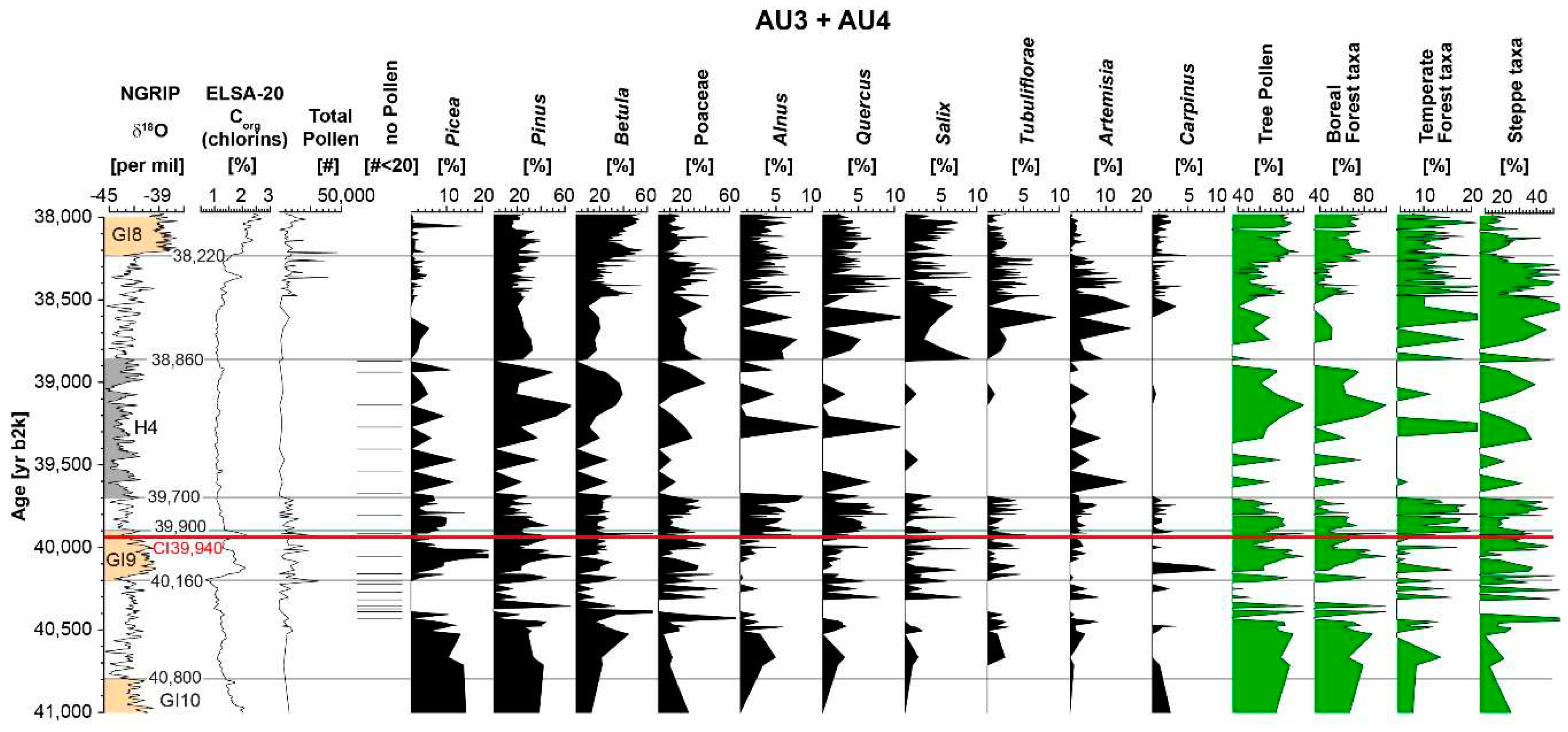

3. Results

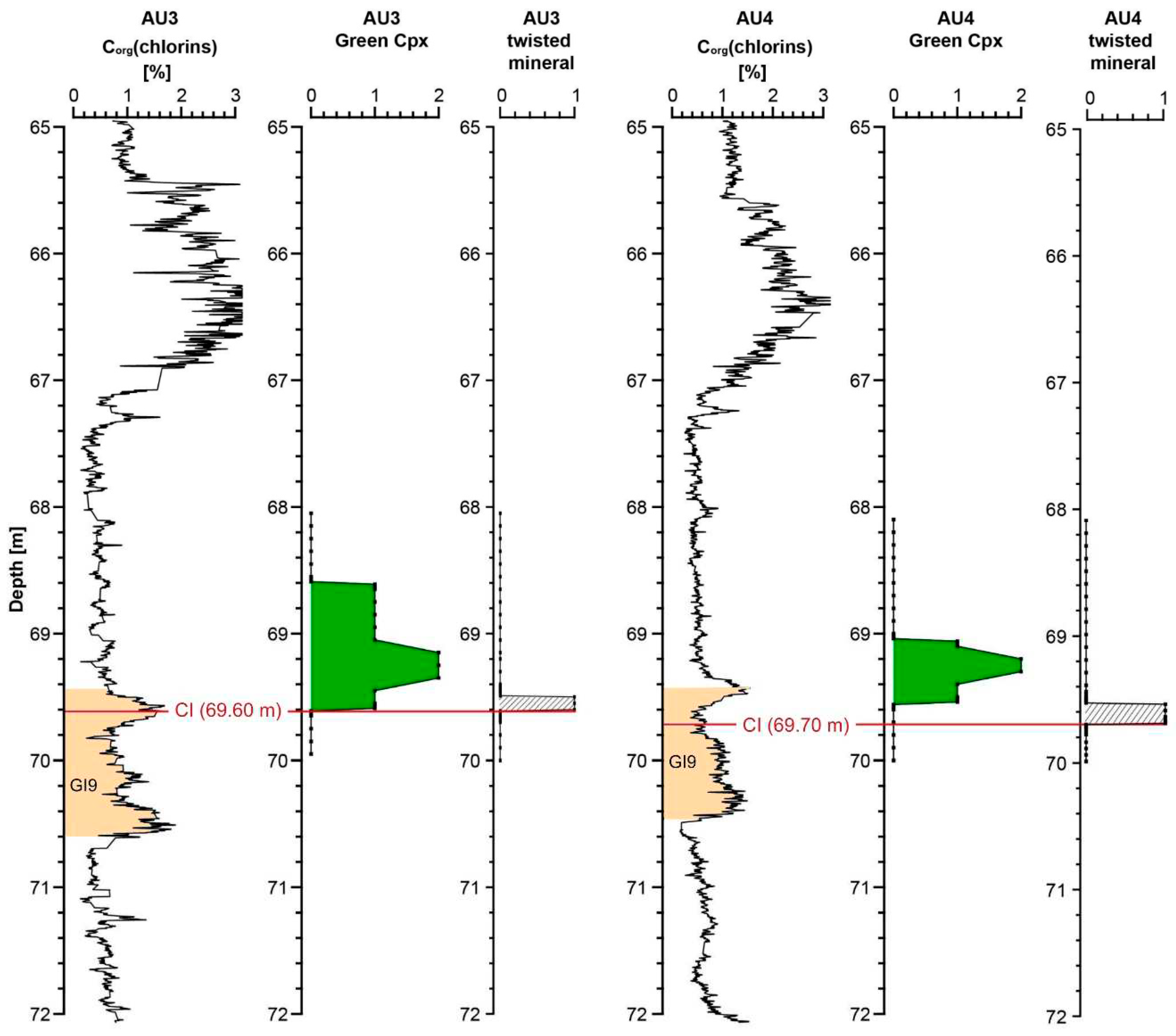

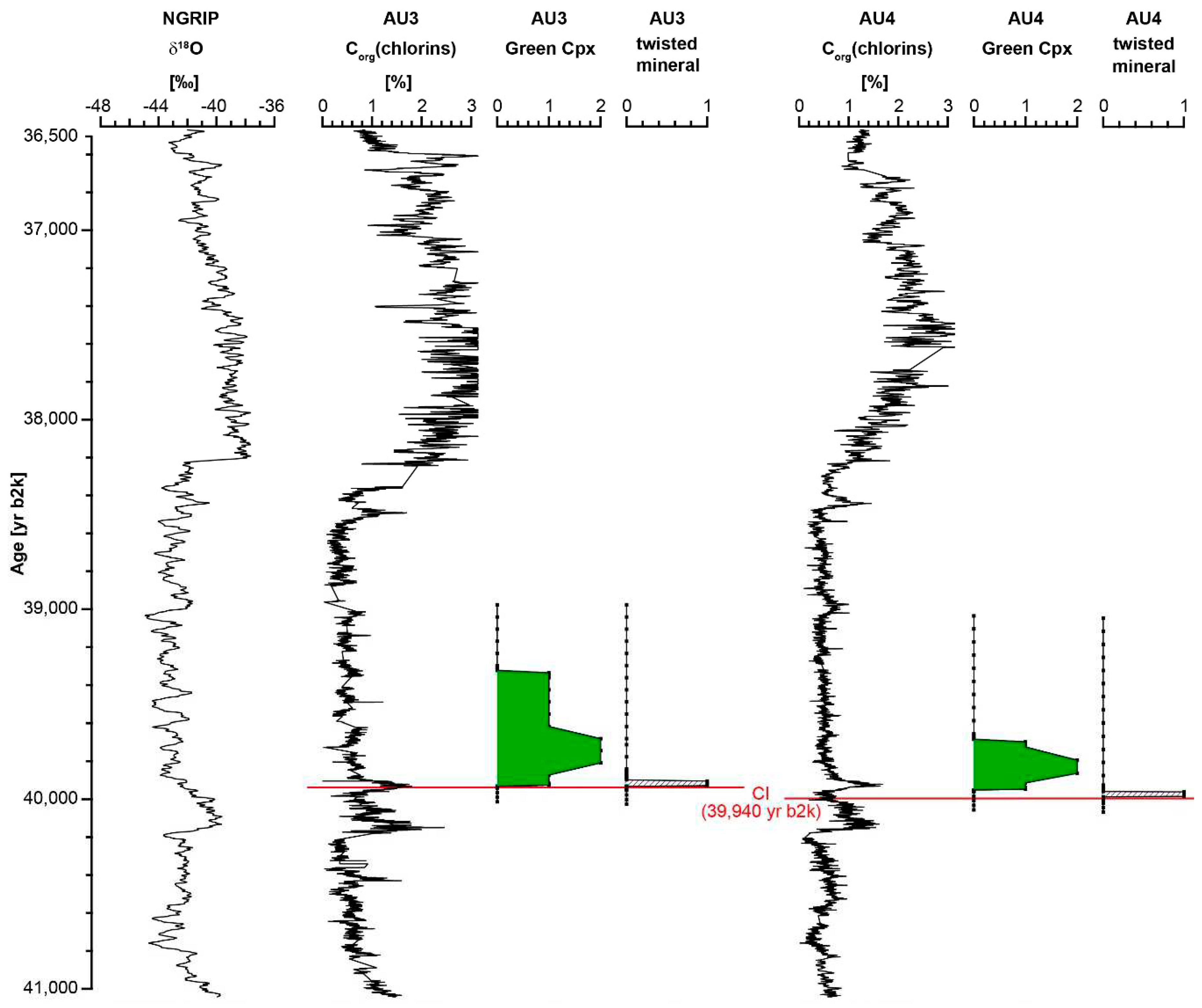

3.1. Geochemical analysis

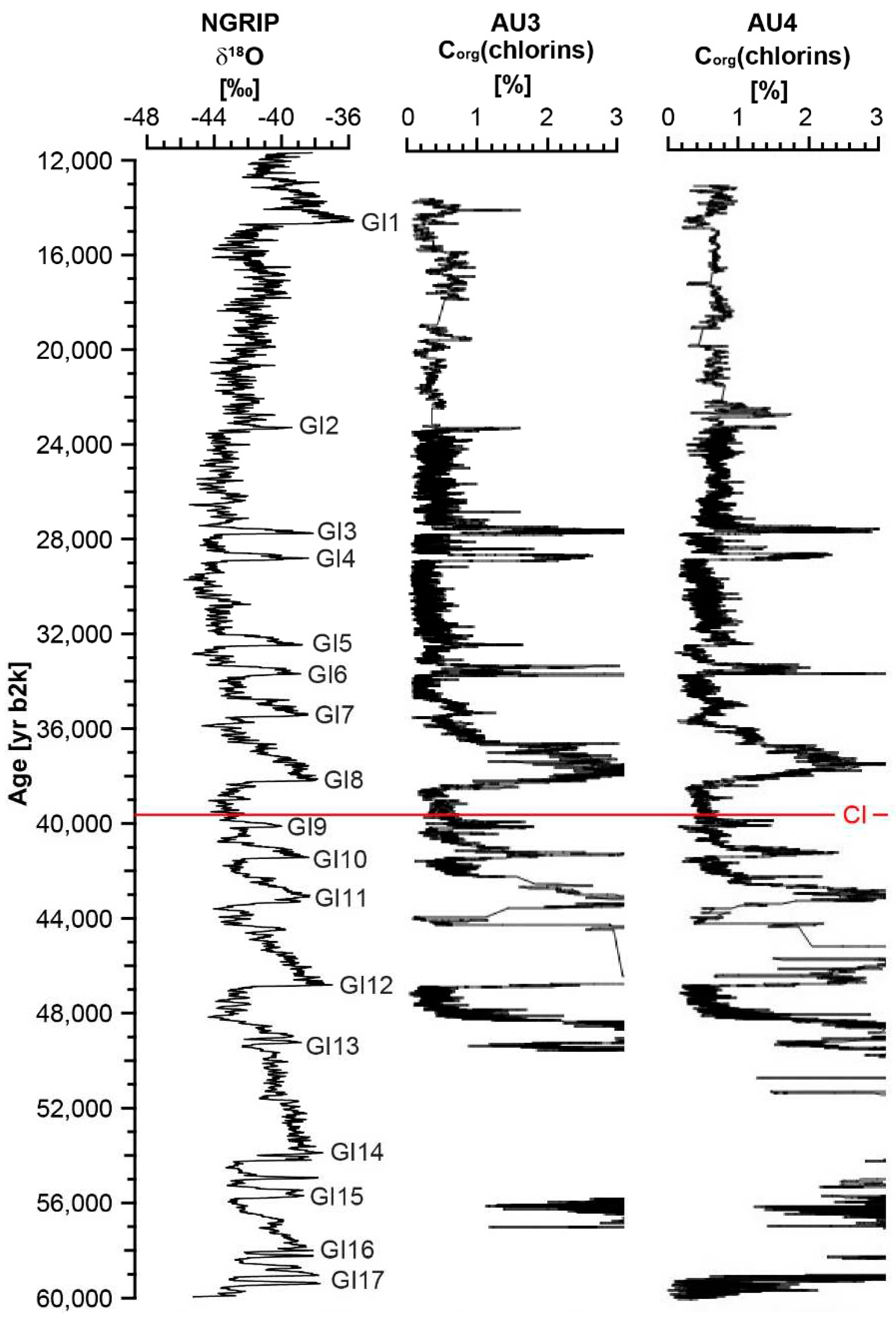

3.2. Stratigraphy

3.3. Result summary

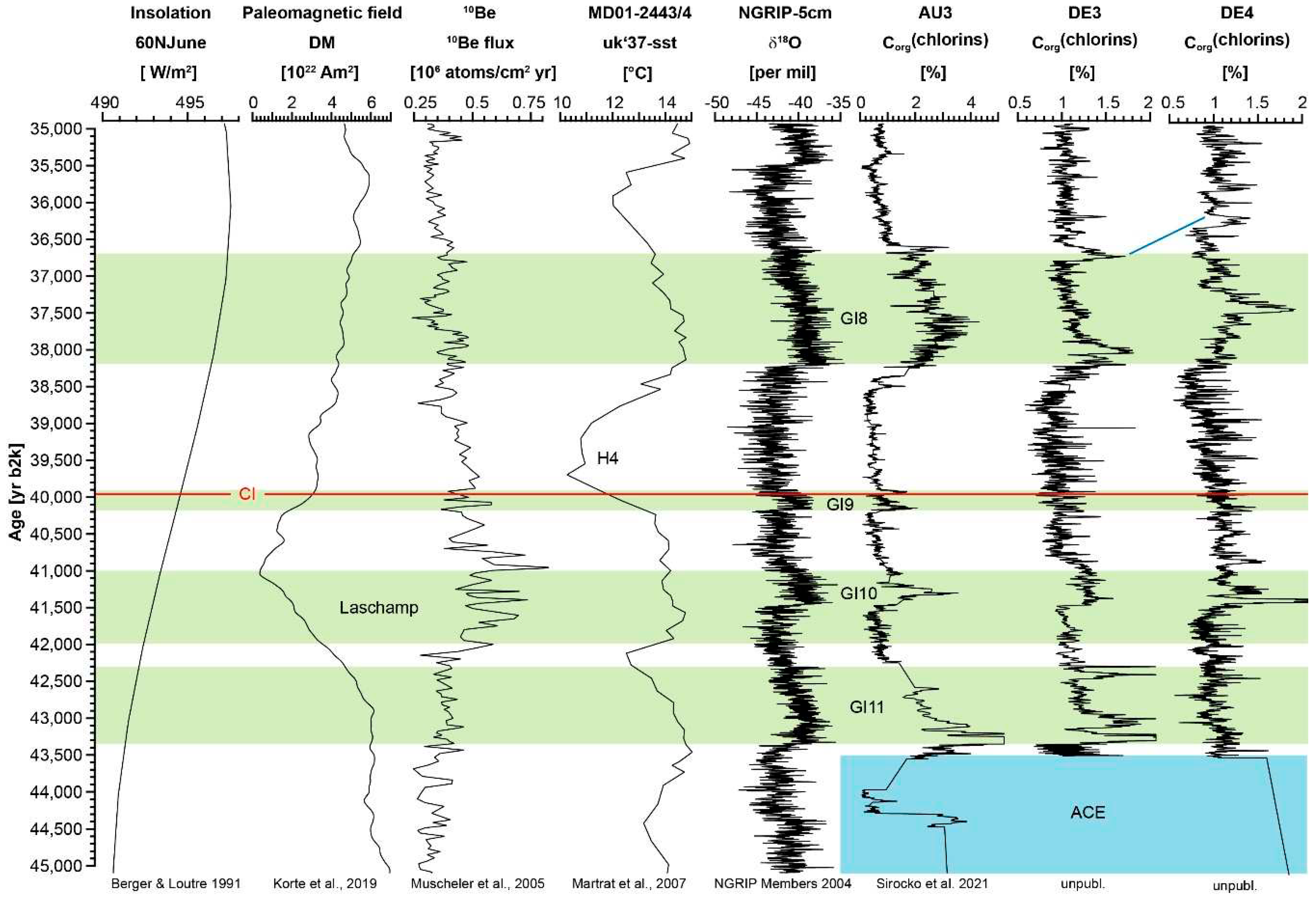

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental change associated with the Campanian Y5-tephra

4.2. Comparison to the global climate between 45,000 and 35,000 yr b2k

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sample ID | SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | FeO | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auel (AU) | ||||||||

| AU-1 | 50.13 | 0.29 | 4.38 | 6.60 | 0.12 | 14.05 | 22.23 | 0.66 |

| AU-2 | 49.54 | 0.63 | 3.76 | 8.37 | 0.39 | 13.20 | 22.60 | 0.43 |

| AU-3 | 48.70 | 1.16 | 5.53 | 4.44 | 0.10 | 14.91 | 22.43 | 0.54 |

| AU-4.2 | 49.87 | 0.65 | 2.57 | 8.90 | 0.78 | 12.84 | 22.15 | 0.64 |

| Mean* | 49.56 | 0.68 | 4.06 | 7.08 | 0.35 | 13.75 | 22.35 | 0.57 |

| Urluia (URL) | ||||||||

| URL-1 | 49.10 | 0.54 | 3.47 | 8.11 | 0.44 | 13.23 | 22.55 | 0.43 |

| URL-2 | 49.95 | 0.40 | 2.68 | 7.52 | 0.42 | 13.61 | 23.06 | 0.49 |

| URL-4 | 48.17 | 0.71 | 4.05 | 8.51 | 0.41 | 12.80 | 22.69 | 0.48 |

| URL-6.2 | 49.39 | 0.65 | 2.39 | 9.24 | 0.83 | 12.11 | 22.87 | 0.60 |

| URL-6.3 | 49.53 | 0.82 | 3.98 | 6.33 | 0.36 | 14.31 | 22.36 | 0.45 |

| Mean** | 49.23 | 0.63 | 3.31 | 8.00 | 0.49 | 13.21 | 22.71 | 0.49 |

| Phlegraean Fields, c.f. Fedele et al. [46] | ||||||||

| Mean*** | 50.10 | 0.58 | 3.57 | 8.31 | 0.35 | 13.46 | 22.98 | 0.34 |

| Sample ID | Na2O | K2O | Cl | FeO | SiO2 | P2O5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urluia (URL) | ||||||

| URL-3.2 | 8.88 | 5.18 | 0.59 | 3.52 | 55.27 | 0.00 |

| URL-5 | 4.29 | 8.42 | 0.39 | 2.72 | 60.47 | 0.07 |

| URL-6.1 | 4.68 | 8.02 | 0.51 | 3.04 | 58.03 | 0.04 |

| URLb_4-3 | 6.04 | 7.60 | 0.64 | 2.76 | 59.26 | 0.06 |

| URL_1-1a | 4.18 | 8.47 | 0.35 | 2.99 | 60.12 | 0.10 |

| Mean* | 5.61 | 7.54 | 0.50 | 3.01 | 58.63 | 0.05 |

| Auel** | 6.18 | 7.24 | 0.49 | 2.65 | 60.01 | 0.08 |

| Phlegraean Fields, c.f. Fedele et al. [46] | ||||||

| Mean*** | 4.53 | 8.42 | 2.84 | 59.78 | 0.20 | |

| Sample ID | CaO | MnO | MgO | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urluia (URL) | ||||||

| URL-3.2 | 1.30 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 22.51 | 98.21 |

| URL-5 | 1.98 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 18.39 | 97.72 |

| URL-6.1 | 2.07 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 17.87 | 95.46 |

| URLb_4-3 | 1.73 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 18.43 | 97.50 |

| URL_1-1a | 2.12 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 18.03 | 97.33 |

| Mean* | 1.84 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 19.05 | 97.25 |

| Auel** | 1.66 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 18.72 | 97.93 |

| Phlegraean Fields, c.f. Fedele et al. [46] | ||||||

| Mean*** | 1.96 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 18.18 | |

| Element | Mean Phlegraean Fields11 samples | Chondrite normalized data [60] |

|---|---|---|

| La | 16.18 | 66.16 |

| Ce | 54.09 | 84.80 |

| Pr | 9.82 | 101.88 |

| Nd | 54.82 | 115.70 |

| Sm | 16.22 | 105.31 |

| Eu | 4.68 | 80.71 |

| Gd | 15.32 | 74.98 |

| Tb | 2.05 | 54.86 |

| Dy | 12.25 | 48.19 |

| Ho | 2.08 | 36.75 |

| Er | 5.40 | 32.55 |

| Tm | 0.70 | 27.23 |

| Yb | 4.31 | 26.10 |

| Lu | 0.63 | 24.99 |

| Oxides | Green Cpx (AU3, 69.60 m) | Green Cpx (Urluia) |

|---|---|---|

| Na2O | 0.33 | 0.65 |

| SiO2 | 45.52 | 50.98 |

| K2O | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| TiO2 | 2.50 | 0.64 |

| FeO | 6.52 | 9.41 |

| Al2O3 | 7.29 | 2.62 |

| MgO | 13.06 | 12.47 |

| CaO | 24.10 | 22.63 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.14 | 0.07 |

| MnO | 0.10 | 0.74 |

| Element | Green Cpx (AU3, 69.60 m) | Green Cpx (Urluia) |

|---|---|---|

| La | 51.39 | 53.31 |

| Ce | 67.97 | 73.85 |

| Pr | 70.77 | 86.54 |

| Nd | 67.60 | 93.42 |

| Sm | 43.96 | 82.34 |

| Eu | 34.06 | 68.42 |

| Gd | 24.87 | 57.81 |

| Tb | 15.03 | 44.94 |

| Dy | 12.40 | 38.65 |

| Ho | 8.55 | 29.10 |

| Er | 6.59 | 25.18 |

| Tm | 5.04 | 19.30 |

| Yb | 5.61 | 20.30 |

| Lu | 4.65 | 16.58 |

References

- Sirocko, F.; Krebsbach, F.; Albert, J.; Britzius, S.; Schenk, F.; Förster, M.W. Relation between the Central European Climate Change and the Eifel Volcanism during the Last 130,000 Years: The ELSA-23 Tephra Stack. Quaternary, submitted.

- Sirocko, F.; Knapp, H.; Dreher, F.; Förster, M.W.; Albert, J.; Brunck, H.; Veres, D.; Dietrich, S.; Zech, M.; Hambach, U.; et al. The ELSA-Vegetation-Stack: Reconstruction of Landscape Evolution Zones (LEZ) from Laminated Eifel Maar Sediments of the Last 60,000 Years. Global and Planetary Change 2016, 142, 108–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silleni, A.; Giordano, G.; Isaia, R.; Ort, M.H. The Magnitude of the 39.8 Ka Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption, Italy: Method, Uncertainties and Errors. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 543399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, S.; Wörner, G.; Civetta, L.; Tesoro, R. Magma Chamber Evolution Prior to the Campanian Ignimbrite and Neapolitan Yellow Tuff Eruptions (Campi Flegrei, Italy). Bull Volcanol 2008, 70, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.V.; Schmincke, H.-U. Pyroclastic Rocks; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fedele, F.G.; Giaccio, B.; Isaia, R.; Orsi, G. The Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption, Heinrich Event 4, and Palaeolithic Change in Europe: A High-Resolution Investigation. Geophysical Monograph Series 2003, 139, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.V.; Orsi, G.; Ort, M.; Heiken, G. Mobility of a Large-Volume Pyroclastic Flow — Emplacement of the Campanian Ignimbrite, Italy. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 1993, 56, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccio, B.; Hajdas, I.; Isaia, R.; Deino, A.; Nomade, S. High-Precision 14C and 40Ar/39Ar Dating of the Campanian Ignimbrite (Y-5) Reconciles the Time-Scales of Climatic-Cultural Processes at 40 Ka. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 45940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunell, R.; Federman, A.; Sparks, S.; Williams, D. The Age, Origin, and Volcanological Significance of the Y-5 Ash Layer in the Mediterranean. Quat. res. 1979, 12, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vivo, B.; Rolandi, G.; Gans, P.B.; Calvert, A.; Bohrson, W.A.; Spera, F.J.; Belkin, H.E. New Constraints on the Pyroclastic Eruptive History of the Campanian Volcanic Plain (Italy). Mineralogy and Petrology 2001, 73, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Svensson, A.; Hvidberg, C.S.; Lohmann, J.; Kristiansen, S.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Steffensen, J.P.; Rasmussen, S.O.; Cook, E.; Kjær, H.A.; et al. Magnitude, Frequency and Climate Forcing of Global Volcanism during the Last Glacial Period as Seen in Greenland and Antarctic Ice Cores (60–9 Ka). Clim. Past 2022, 18, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterne, M.; Kallel, N.; Labeyrie, L.; Vautravers, M.; Duplessy, J.; Rossignol-Strick, M.; Cortijo, E.; Arnold, M.; Fontugne, M. Hydrological Relationship between the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea during the Past 15-75 Kyr. Paleoceanography 1999, 14, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton-That, T.; Singer, B.; Paterne, M. 40Ar/39Ar Dating of Latest Pleistocene (41 Ka) Marine Tephra in the Mediterranean Sea: Implications for Global Climate Records. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2001, 184, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veres, D.; Lane, C.S.; Timar-Gabor, A.; Hambach, U.; Constantin, D.; Szakács, A.; Fülling, A.; Onac, B.P. The Campanian Ignimbrite/Y5 Tephra Layer – A Regional Stratigraphic Marker for Isotope Stage 3 Deposits in the Lower Danube Region, Romania. Quaternary International 2013, 293, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccio, B.; Isaia, R.; Fedele, F.G.; Di Canzio, E.; Hoffecker, J.; Ronchitelli, A.; Sinitsyn, A.A.; Anikovich, M.; Lisitsyn, S.N.; Popov, V.V. The Campanian Ignimbrite and Codola Tephra Layers: Two Temporal/Stratigraphic Markers for the Early Upper Palaeolithic in Southern Italy and Eastern Europe. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2008, 177, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narcisi, B. Tephrochronology of a Late Quaternary Lacustrine Record from the Monticchio Maar (Vulture Volcano, Southern Italy). Quaternary Science Reviews 1996, 15, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.; Ryan, W.B.F.; Ninkovich, D.; Altherr, R. Explosive Volcanic Activity in the Mediterranean over the Past 200,000 Yr as Recorded in Deep-Sea Sediments. Geol Soc America Bull 1978, 89, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, L.; Scarpati, C.; Sparice, D.; Perrotta, A.; Laiena, F. A Chemostratigraphic Study of the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption (Campi Flegrei, Italy): Insights on Magma Chamber Withdrawal and Deposit Accumulation as Revealed by Compositionally Zoned Stratigraphic and Facies Framework. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2016, 324, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpati, C.; Perrotta, A. Stratigraphy and Physical Parameters of the Plinian Phase of the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption. Geological Society of America Bulletin 2016, 128, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.C.; Isaia, R.; Engwell, S.L.; Albert, Paul. G. Tephra Dispersal during the Campanian Ignimbrite (Italy) Eruption: Implications for Ultra-Distal Ash Transport during the Large Caldera-Forming Eruption. Bull Volcanol 2016, 78, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civetta, L.; Orsi, G.; Pappalardo, L.; Fisher, R.V.; Heiken, G.; Ort, M. Geochemical Zoning, Mingling, Eruptive Dynamics and Depositional Processes — the Campanian Ignimbrite, Campi Flegrei Caldera, Italy. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 1997, 75, 183–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwell, S.L.; Sparks, R.S.J.; Carey, S. Physical Characteristics of Tephra Layers in the Deep Sea Realm: The Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption. SP 2014, 398, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, F.G.; Giaccio, B.; Hajdas, I. Timescales and Cultural Process at 40,000 BP in the Light of the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption, Western Eurasia. Journal of Human Evolution 2008, 55, 834–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimmons, K.E.; Hambach, U.; Veres, D.; Iovita, R. The Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption: New Data on Volcanic Ash Dispersal and Its Potential Impact on Human Evolution. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowaczyk, N.R.; Arz, H.W.; Frank, U.; Kind, J.; Plessen, B. Dynamics of the Laschamp Geomagnetic Excursion from Black Sea Sediments. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2012, 351–352, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacha, L. Luminescence Dating of Loess from the Island of Susak in the Northern Adriatic Sea and the “Gorjanović Loess Section” from Vukovar in Eastern Croatia, Freie Universität Berlin, 2011.

- Tsanova, T.; Veres, D.; Hambach, U.; Spasov, R.; Dimitrova, I.; Popov, P.; Talamo, S.; Sirakova, S. Upper Palaeolithic Layers and Campanian Ignimbrite/Y-5 Tephra in Toplitsa Cave, Northern Bulgaria. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2021, 37, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masotta, M.; Mollo, S.; Freda, C.; Gaeta, M.; Moore, G. Clinopyroxene–Liquid Thermometers and Barometers Specific to Alkaline Differentiated Magmas. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2013, 166, 1545–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, E.L.; Smith, V.C.; Albert, P.G.; Aydar, E.; Civetta, L.; Cioni, R.; Çubukçu, E.; Gertisser, R.; Isaia, R.; Menzies, M.A.; et al. The Major and Trace Element Glass Compositions of the Productive Mediterranean Volcanic Sources: Tools for Correlating Distal Tephra Layers in and around Europe. Quaternary Science Reviews 2015, 118, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, F.; Schenk, F. Modelling of Uncertainty in Geo Sciences Sites. Squirrel Papers 2023, 5(1), #4. [CrossRef]

- Thiery, F.; Schenk, F. CI Site Instances Collection. Squirrel Papers 2023, Research Squirrel Engineers, via @campanian-ignimbrite-geo, https://research-squirrel-engineers.github.io/campanian-ignimbrite-geo/Site_collection/index.html.

- Thiery, F.; Schenk, F. Campanian Ignimbrite Geo Locations. Squirrel Papers 2023, 5(2), #2. [CrossRef]

- Thiery, F.; Schenk, F.; Baars, S. Dealing with Doubts: Site Georeferencing in Archaeology and in the Geosciences. Squirrel Papers 2023, 5(1), #6. [CrossRef]

- Thiery, F. Semantic Modelling Using LOD Techniques of Uncertainty, Vagueness and Ambiguities in the Archaeological Domain. Squirrel Papers 2023, 5(5), #3. [CrossRef]

- Obreht, I.; Zeeden, C.; Hambach, U.; Veres, D.; Marković, S.B.; Bösken, J.; Svirčev, Z.; Bačević, N.; Gavrilov, M.B.; Lehmkuhl, F. Tracing the Influence of Mediterranean Climate on Southeastern Europe during the Past 350,000 Years. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 36334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S.B.; Stevens, T.; Kukla, G.J.; Hambach, U.; Fitzsimmons, K.E.; Gibbard, P.; Buggle, B.; Zech, M.; Guo, Z.; Hao, Q.; et al. Danube Loess Stratigraphy — Towards a Pan-European Loess Stratigraphic Model. Earth-Science Reviews 2015, 148, 228–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deino, A.L.; Orsi, G.; De Vita, S.; Piochi, M. The Age of the Neapolitan Yellow Tuff Caldera-Forming Eruption (Campi Flegrei Caldera – Italy) Assessed by 40Ar/39Ar Dating Method. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 2004, 133, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Van Den Bogaard, C.; Merkt, J.; Müller, J. A New Lateglacial Chronostratigraphic Tephra Marker for the South-Eastern Alps: The Neapolitan Yellow Tuff (NYT) in Längsee (Austria) in the Context of a Regional Biostratigraphy and Palaeoclimate. Quaternary International 2002, 88, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirocko, F.; Seelos, K.; Schaber, K.; Rein, B.; Dreher, F.; Diehl, M.; Lehne, R.; Jäger, K.; Krbetschek, M.; Degering, D. A Late Eemian Aridity Pulse in Central Europe during the Last Glacial Inception. Nature 2005, 436, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirocko, F.; Dietrich, S.; Veres, D.; Grootes, P.M.; Schaber-Mohr, K.; Seelos, K.; Nadeau, M.-J.; Kromer, B.; Rothacker, L.; Röhner, M.; et al. Multi-Proxy Dating of Holocene Maar Lakes and Pleistocene Dry Maar Sediments in the Eifel, Germany. Quaternary Science Reviews 2013, 62, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirocko, F.; Martínez-García, A.; Mudelsee, M.; Albert, J.; Britzius, S.; Christl, M.; Diehl, D.; Diensberg, B.; Friedrich, R.; Fuhrmann, F.; et al. Muted Multidecadal Climate Variability in Central Europe during Cold Stadial Periods. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, J.; Sirocko, F. Evidence for an Extreme Cooling Event Prior to the Laschamp Geomagnetic Excursion in Eifel Maar Sediments. Quaternary 2023, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, F.; Schenk, F. How to Locate the Campanian Ignimbrite Site Urluia Based on Literature? How to Provide and Publish This Data in a FAIR Way? Squirrel Papers 2023, 5(1), #5. [CrossRef]

- Thiery, F.; Schenk, F. CI Site 52: Urluia (Romania). Squirrel Papers 2023, Research Squirrel Engineers, via @campanian-ignimbrite-geo, http://fuzzy-sl.squirrel.link/data/cisite_52. /.

- Obreht, I.; Hambach, U.; Veres, D.; Zeeden, C.; Bösken, J.; Stevens, T.; Marković, S.B.; Klasen, N.; Brill, D.; Burow, C.; et al. Shift of Large-Scale Atmospheric Systems over Europe during Late MIS 3 and Implications for Modern Human Dispersal. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, L.; Zanetti, A.; Morra, V.; Lustrino, M.; Melluso, L.; Vannucci, R. Clinopyroxene/Liquid Trace Element Partitioning in Natural Trachyte–Trachyphonolite Systems: Insights from Campi Flegrei (Southern Italy). Contrib Mineral Petrol 2009, 158, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, B.; Sirocko, F. In-Situ Reflectance Spectroscopy - Analysing Techniques for High-Resolution Pigment Logging in Sediment Cores. International Journal of Earth Sciences 2002, 91, 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.J.B. Electron Microprobe Analysis and Scanning Electron Microscopy in Geology, 2nd ed.; Camebridge University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prelević, D.; Akal, C.; Romer, R.L.; Mertz-Kraus, R.; Helvac, C. Magmatic Response to Slab Tearing: Constraints from the Afyon Alkaline Volcanic Complex, Western Turkey. Journal of Petrology 2015, 56, 527–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, D.; Frischknecht, R.; Heinrich, C.A.; Kahlert, H.-J. Capabilities of an Argon Fluoride 193 Nm Excimer Laser for Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectometry Microanalysis of Geological Materials. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1997, 12, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochum, K.P.; Weis, U.; Stoll, B.; Kuzmin, D.; Yang, Q.; Raczek, I.; Jacob, D.E.; Stracke, A.; Birbaum, K.; Frick, D.A.; et al. Determination of Reference Values for NIST SRM 610–617 Glasses Following ISO Guidelines. Geostandard Geoanalytic Res 2011, 35, 397–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longerich, H.P.; Jackson, S.E.; Günther, D. Inter-Laboratory Note. Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometric Transient Signal Data Acquisition and Analyte Concentration Calculation. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1996, 11, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, T.O.; Van Der Gaast, S.; Koster, B.; Vaars, A.; Gieles, R.; De Stigter, H.C.; De Haas, H.; Van Weering, T.C.E. The Avaatech XRF Core Scanner: Technical Description and Applications to NE Atlantic Sediments. SP 2006, 267, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, B.E.; Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, M. Pollen Analysis and Pollen Diagrams. In Handbook of Holocene Palaoecology and Palaeohydrology; 1986; pp. 455–484. [Google Scholar]

- Fægri, K.; Iversen, J. Textbook of Pollen Analysis; 4th ed.; 1989.

- Britzius, S.; Dreher, F.; Maisel, P.; Sirocko, F. Vegetation Patterns during the Last 132,000 Years from Sediment Cores from Six Eifel Maars: The ELSA Stack 24 Pollen. Quaternary, submitted.

- Kendrick, J.E.; Lavallée, Y.; Mariani, E.; Dingwell, D.B.; Wheeler, J.; Varley, N.R. Crystal Plasticity as an Indicator of the Viscous-Brittle Transition in Magmas. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbaret, L.; Bystricky, M.; Champallier, R. Microstructures and Rheology of Hydrous Synthetic Magmatic Suspensions Deformed in Torsion at High Pressure. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, 2006JB004856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, S.; Hardiman, M.J.; Staff, R.A.; Koutsodendris, A.; Appelt, O.; Blockley, S.P.E.; Lowe, J.J.; Manning, C.J.; Ottolini, L.; Schmitt, A.K.; et al. The Marine Isotope Stage 1–5 Cryptotephra Record of Tenaghi Philippon, Greece: Towards a Detailed Tephrostratigraphic Framework for the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Quaternary Science Reviews 2018, 186, 236–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, N.M.; Hamilton, P.J.; O’Nions, R.K. Rare-Earth Abundances in Chondritic Meteorites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1978, 42, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, L.; Scarpati, C.; Lanphere, M.; Melluso, L.; Morra, V.; Perrotta, A.; Ricci, G. The Breccia Museo Formation, Campi Flegrei, Southern Italy: Geochronology, Chemostratigraphy and Relationship with the Campanian Ignimbrite Eruption. Bull Volcanol 2008, 70, 1189–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.O.; Bigler, M.; Blockley, S.P.; Blunier, T.; Buchardt, S.L.; Clausen, H.B.; Cvijanovic, I.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Johnsen, S.J.; Fischer, H.; et al. A Stratigraphic Framework for Abrupt Climatic Changes during the Last Glacial Period Based on Three Synchronized Greenland Ice-Core Records: Refining and Extending the INTIMATE Event Stratigraphy. Quaternary Science Reviews 2014, 106, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhöfer, M. Plankton-Pigmente Und Deren Abbauprodukte Als Biomarker Zur Beschreibung Und Abschätzung Der Phytoplankton-Sukzession Und -Sedimentation Im Nordatlantik. Berichte aus dem Institut für Meereskunde an der Christian-Albrechts-Universität Kiel 1994, 251. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, J.; Zander, P.; Grosjean, M.; Sirocko, F. Fine-Tuning of Sub-Annual Resolution Spectral Index Time Series from Eifel Maar Sediments, Western Germany, to the NGRIP 3 δ18O Chronology, 26–60 Ka. Quaternary, submitted.

- Costa, A.; Folch, A.; Macedonio, G.; Giaccio, B.; Isaia, R.; Smith, V.C. Quantifying Volcanic Ash Dispersal and Impact of the Campanian Ignimbrite Super-eruption. Geophysical Research Letters 2012, 39, 2012GL051605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martrat, B.; Grimalt, J.O.; Shackleton, N.J.; de Abreu, L.; Hutterli, M.A.; Stocker, T.F. Four Climate Cycles of Recurring Deep and Surface Water Destabilizations on the Iberian Margin. Science 2007, 317, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.; Loutre, M.F. Insolation Values for the Climate of the Last 10 Million Years. Quaternary Science Reviews 1991, 10, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, M.; Brown, M.C.; Panovska, S.; Wardinski, I. Robust Characteristics of the Laschamp and Mono Lake Geomagnetic Excursions: Results From Global Field Models. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscheler, R.; Beer, J.; Kubik, P.W.; Synal, H.-A. Geomagnetic Field Intensity during the Last 60,000 Years Based on 10Be and 36Cl from the Summit Ice Cores and 14C. Quaternary Science Reviews 2005, 24, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).