Submitted:

22 December 2023

Posted:

25 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

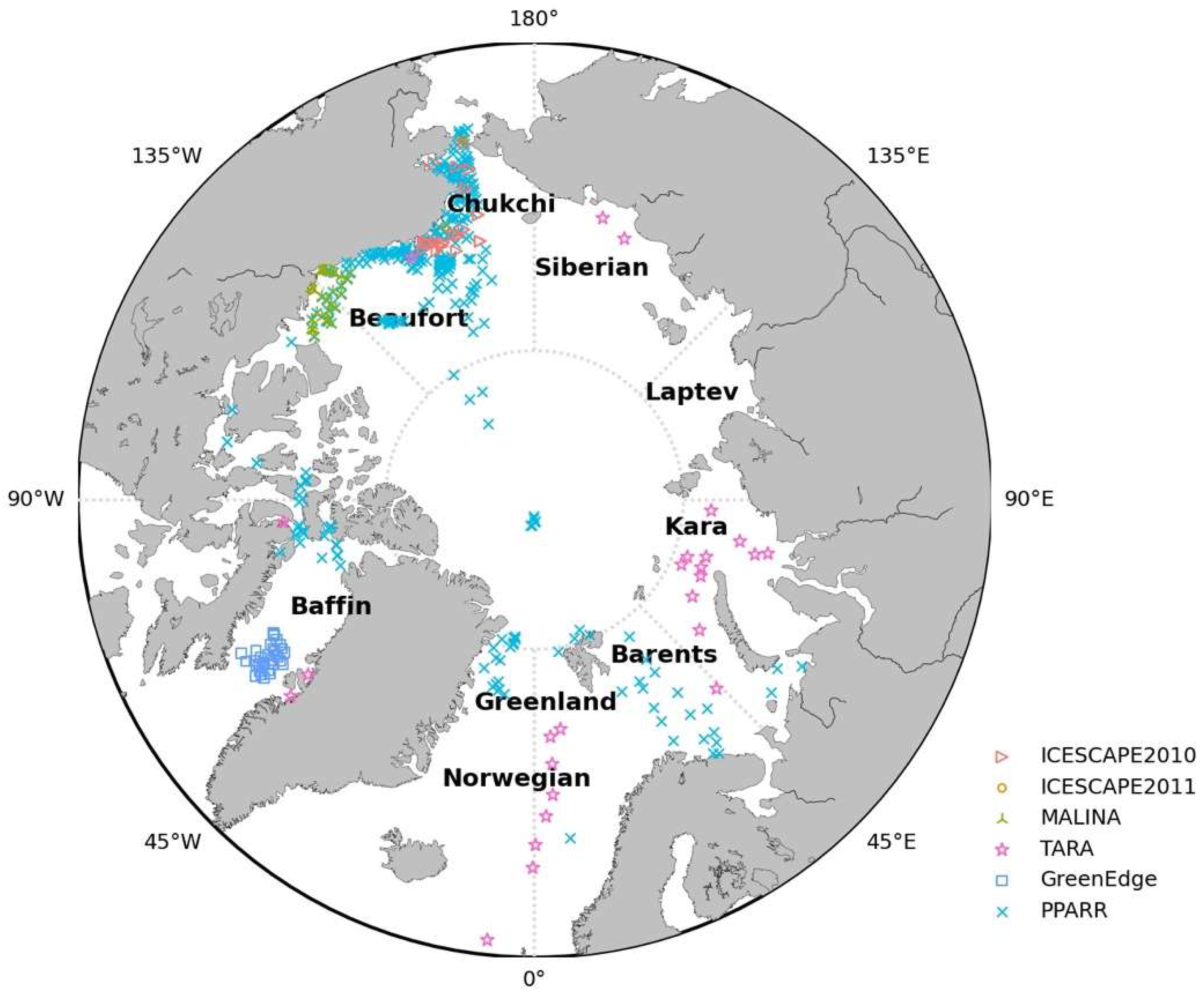

2. Data

2.1. In situ data

2.2. Satellite products

3. Methods

3.1. Descriptions of existing operational ocean-color algorithms

3.1.1. Empirical algorithms

3.1.2. Semi-analytical algorithm – GSM

3.3. Primary-production model

3.4. Climatology products

3.5. Matchup analysis

4. Results

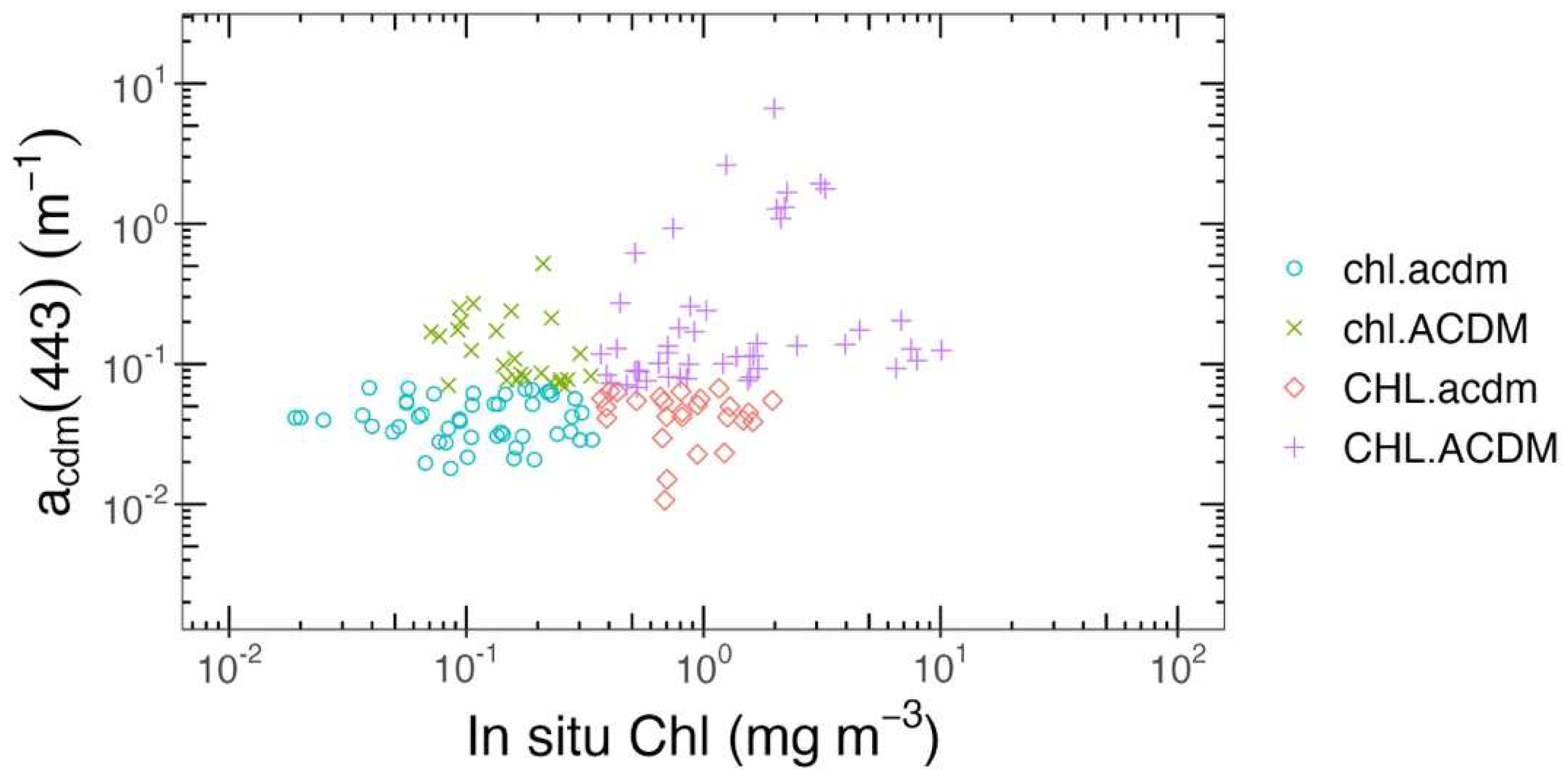

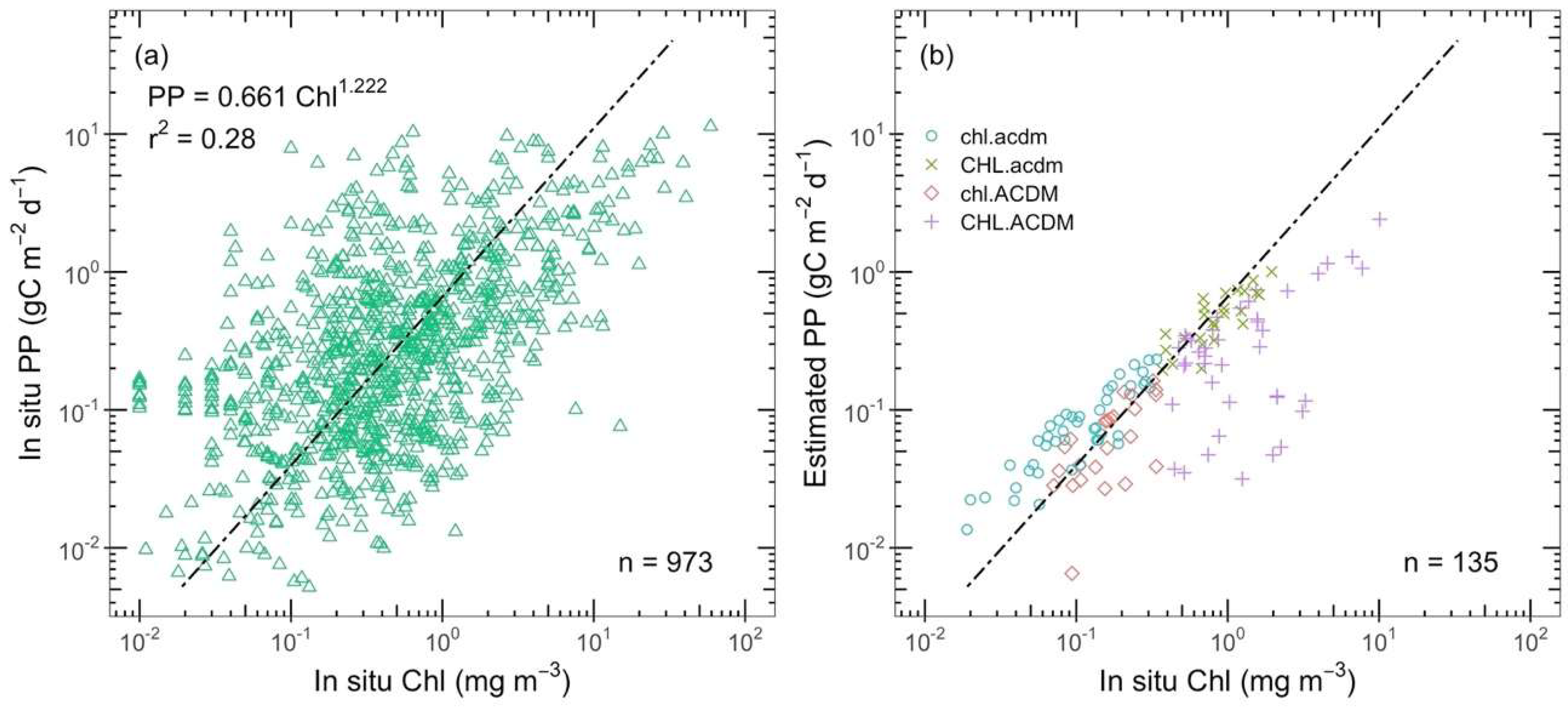

4.1. Overview of product performance

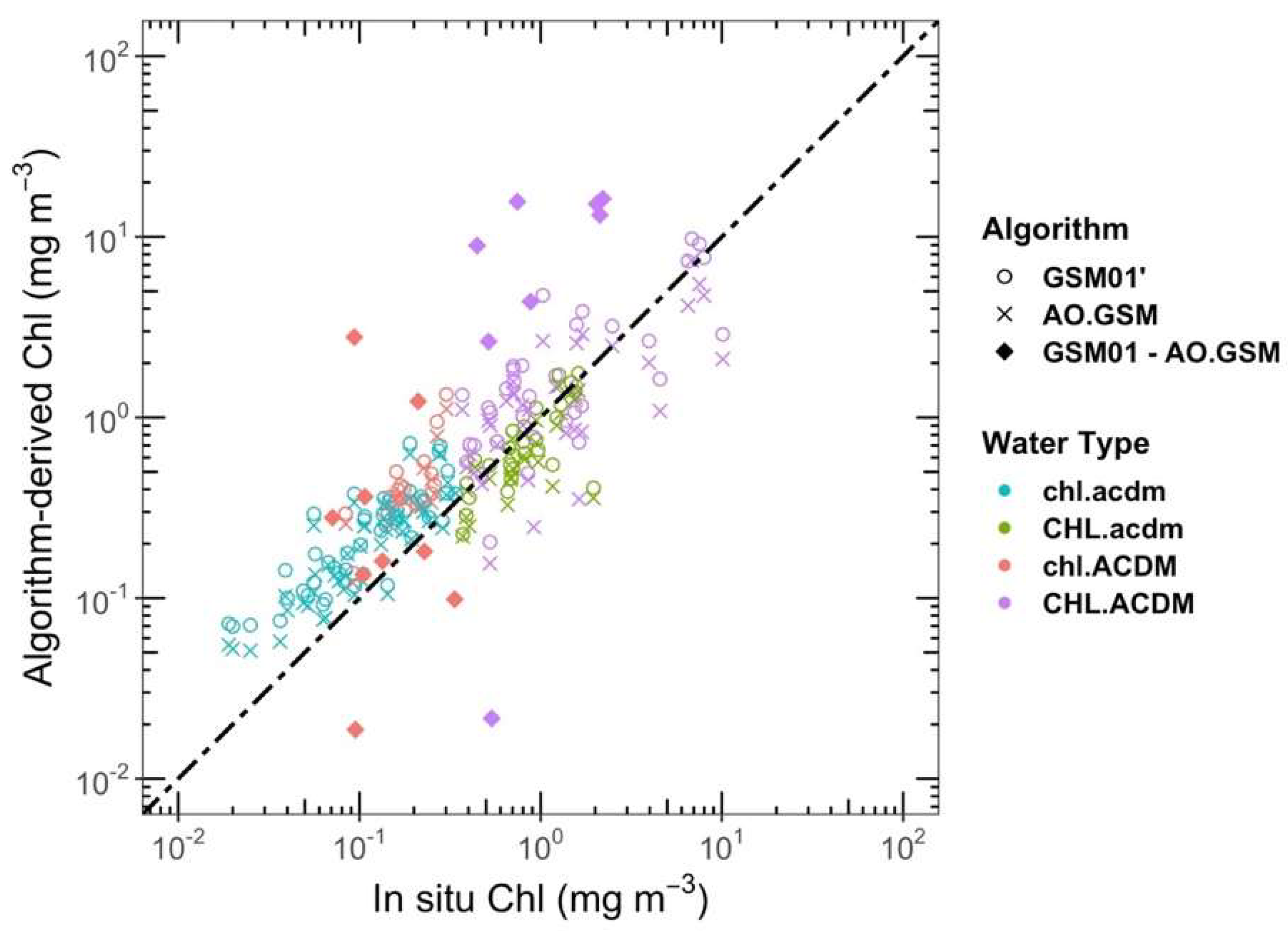

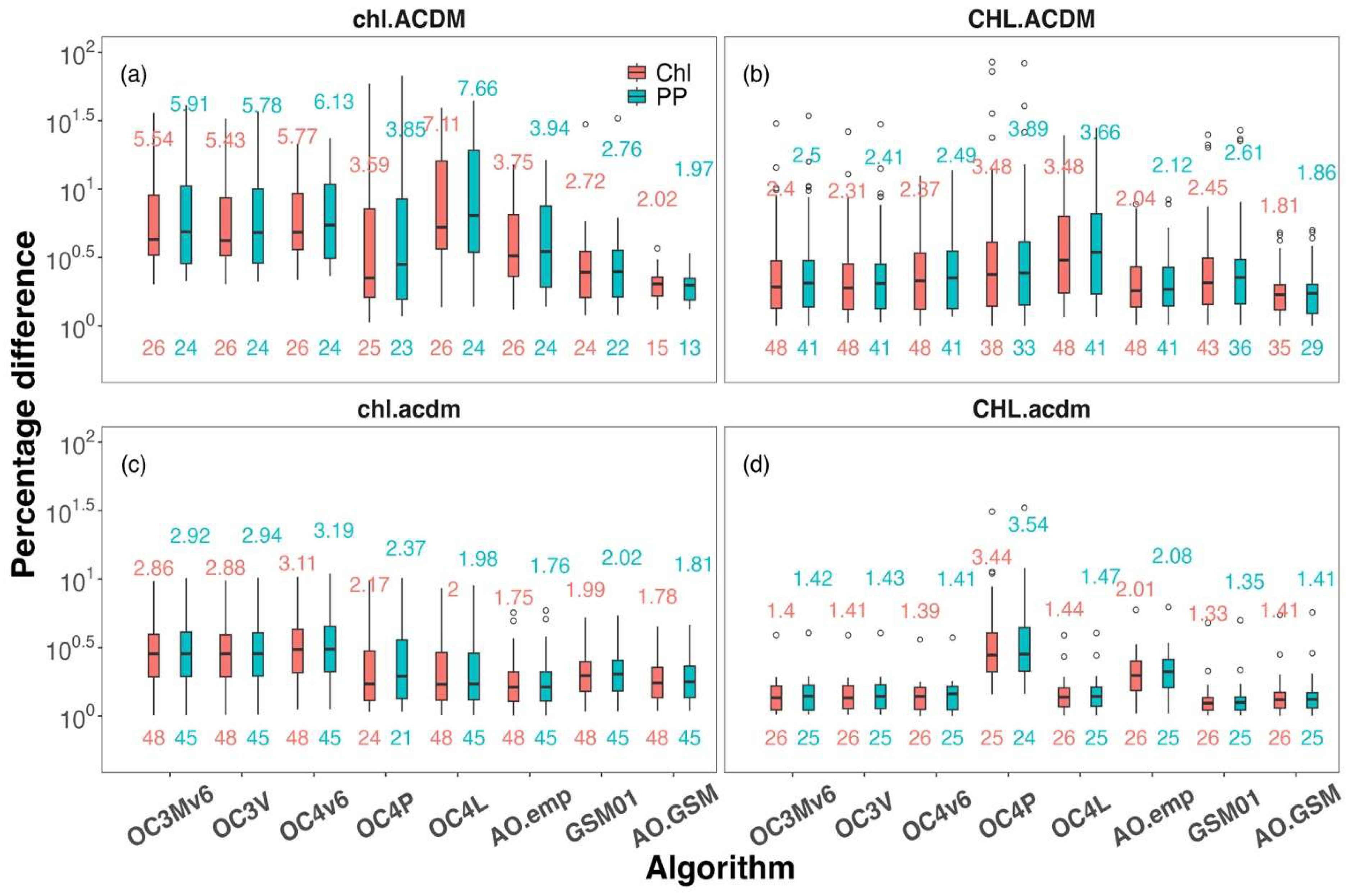

4.2. Bio-optical algorithm evaluations

4.3. Impacts on PP estimates

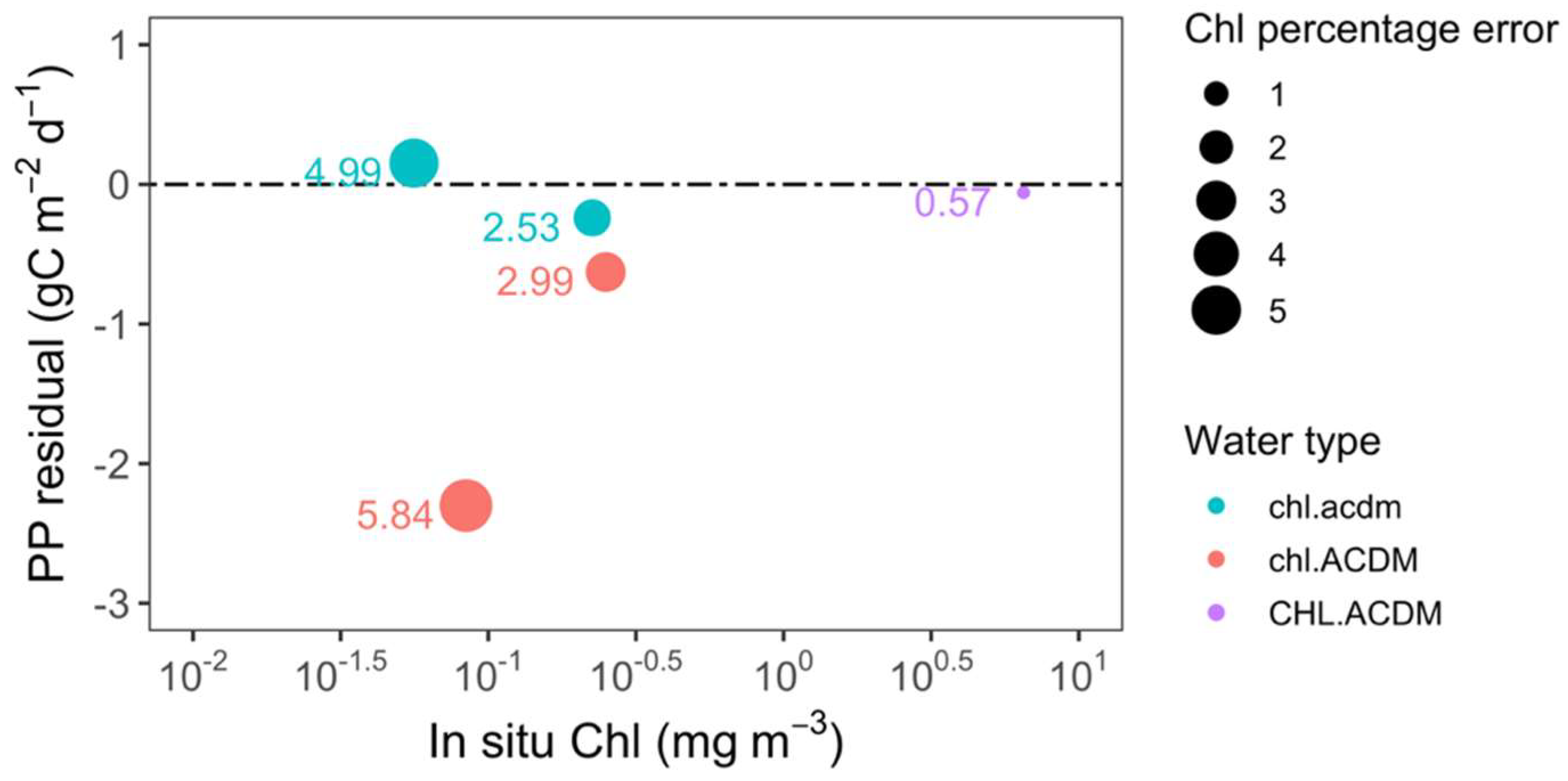

5. Discussions and perspectives

5.1. Chl retrieval error

5.2. PP estimate error

5.3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carmack, E.C.; Yamamoto-Kawai, M.; Haine, T.W.; Bacon, S.; Bluhm, B.A.; Lique, C.; Melling, H.; Polyakov, I.V.; Straneo, F.; Timmermans, M.-L.; et al. Freshwater and Its Role in the Arctic Marine System: Sources, Disposition, Storage, Export, and Physical and Biogeochemical Consequences in the Arctic and Global Oceans. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2016, 121, 675–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.J.; Holmes, R.M.; McClelland, J.W.; Vörösmarty, C.J.; Lammers, R.B.; Shiklomanov, A.I.; Shiklomanov, I.A.; Rahmstorf, S. Increasing River Discharge to the Arctic Ocean. Science 2002, 298, 2171–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, P.A.; McClelland, J.W.; Holmes, R.M.; Zhulidov, A.V.; Mull, K.; Peterson, B.J.; Striegl, R.G.; Aiken, G.R.; Gurtovaya, T.Y. Flux and Age of Dissolved Organic Carbon Exported to the Arctic Ocean: A Carbon Isotopic Study of the Five Largest Arctic Rivers: ARCTIC RIVER DOC. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2007, 21, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, M.; Arrigo, K.; Bélanger, S.; Forget, M.-H.; et al. Ocean Colour Remote Sensing in Polar Seas. International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG) 2015. http://ioccg.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/10/ioccg-report-16.pdf.

- Matsuoka, A.; Ortega-Retuerta, E.; Bricaud, A.; Arrigo, K.R.; Babin, M. Characteristics of Colored Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM) in the Western Arctic Ocean: Relationships with Microbial Activities. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2015, 118, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, A.; Huot, Y.; Shimada, K.; Saitoh, S.-I.; Babin, M. Bio-Optical Characteristics of the Western Arctic Ocean: Implications for Ocean Color Algorithms. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2007, 33, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, A.; Bricaud, A.; Benner, R.; Para, J.; Sempéré, R.; Prieur, L.; Bélanger, S.; Babin, M. Tracing the Transport of Colored Dissolved Organic Matter in Water Masses of the Southern Beaufort Sea: Relationship with Hydrographic Characteristics. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, A.; Hill, V.; Huot, Y.; Babin, M.; Bricaud, A. Seasonal Variability in the Light Absorption Properties of Western Arctic Waters: Parameterization of the Individual Components of Absorption for Ocean Color Applications. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2011, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidov, A.B.; Kopelevich, O.V.; Mosharov, S.A.; Sheberstov, S.V.; Vazyulya, S.V. Modelling Kara Sea Phytoplankton Primary Production: Development and Skill Assessment of Regional Algorithms. Journal of Sea Research 2017, 125, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, D.; Pozdnyakov, D.; Johannessen, J.; Counillon, F.; Sychov, V. Satellite-Derived Multi-Year Trend in Primary Production in the Arctic Ocean. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2013, 34, 3903–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyuk, P.A.; Stepochkin, I.E.; Bukin, O.A.; Sokolova, E.B.; Mayor, A.Y.; Shambarova, J.V.; Gorbushkin, A.R. Determination of the Chlorophyll a Concentration by MODIS-Aqua and VIIRS Satellite Radiometers in Eastern Arctic and Bering Sea. Izvestiya, Atmospheric and Oceanic Physics 2016, 52, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vörösmarty, C.J.; Fekete, B.M.; Meybeck, M.; Lammers, R.B. Global System of Rivers: Its Role in Organizing Continental Land Mass and Defining Land-to-Ocean Linkages. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2000, 14, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Behrenfeld, M.J.; Randerson, J.T.; Falkowski, P. Primary Production of the Biosphere: Integrating Terrestrial and Oceanic Components. Science 1998, 281, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winder, M.; Sommer, U. Phytoplankton Response to a Changing Climate. Hydrobiologia 2012, 698, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, K.R.; van Dijken, G.; Pabi, S. Impact of a Shrinking Arctic Ice Cover on Marine Primary Production. Geophysical Research Letters 2008, 35, L19603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, S.; Babin, M.; Tremblay, J.-É. Increasing Cloudiness in Arctic Damps the Increase in Phytoplankton Primary Production Due to Sea Ice Receding. Biogeosciences (Online) 2013, 10, 4087–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahru, M.; Brotas, V.; Manzano-Sarabia, M.; Mitchell, B.G. Are Phytoplankton Blooms Occurring Earlier in the Arctic? Global Change Biology 2011, 17, 1733–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.M.; Arrigo, K.R. Ocean Color Algorithms for Estimating Chlorophyll a, CDOM Absorption, and Particle Backscattering in the Arctic Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2020, 125, e2019JC015706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, G.F.; Wang, J.; Comiso, J.C. Transformation of Global Satellite Chlorophyll Retrievals with a Regionally Tuned Algorithm. Remote Sensing of Environment 2004, 90, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricaud, A.; Morel, A.; Prieur, L. Absorption by Dissolved Organic Matter of the Sea (Yellow Substance) in the UV and Visible Domains1. Limnology and Oceanography 1981, 26, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.E.; Maritorena, S.; Mitchell, B.G.; Siegel, D.A.; Carder, K.L.; Garver, S.A.; Kahru, M.; McClain, C. Ocean Color Chlorophyll Algorithms for SeaWiFS. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1998, 103, 24937–24953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.E.; Maritorena, S.; Siegel, D.A.; O’Brien, M.C.; Toole, D.; Mitchell, B.G.; Kahru, M.; Chavez, F.P.; Strutton, P.; Cota, G.F.; et al. Ocean Color Chlorophyll a Algorithms for SeaWiFS, OC2 and OC4: Version 4. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2000, 103, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cota, G.F. Remote-Sensing Reflectance in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas: Observations and Models. Applied Optics 2003, 42, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritorena, S.; Siegel, D.A.; Peterson, A.R. Optimization of a Semianalytical Ocean Color Model for Global-Scale Applications. Applied Optics 2002, 41, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massicotte, P.; Amon, R.M.W.; Antoine, D.; Archambault, P.; Balzano, S.; Bélanger, S.; Benner, R.; Boeuf, D.; Bricaud, A.; Bruyant, F.; et al. The MALINA Oceanographic Expedition: How Do Changes in Ice Cover, Permafrost and UV Radiation Impact Biodiversity and Biogeochemical Fluxes in the Arctic Ocean? Earth System Science Data 2021, 13, 1561–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, K.R. Impacts of Climate on EcoSystems and Chemistry of the Arctic Pacific Environment (ICESCAPE). Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2015, 118, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunagawa, S.; Acinas, S.G.; Bork, P.; Bowler, C.; Eveillard, D.; Gorsky, G.; Guidi, L.; Iudicone, D.; Karsenti, E.; Lombard, F.; et al. Tara Oceans: Towards Global Ocean Ecosystems Biology. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2020, 18, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massicotte, P.; Amiraux, R.; Amyot, M.-P.; Archambault, P.; Ardyna, M.; Arnaud, L.; Artigue, L.; Aubry, C.; Ayotte, P.; Bécu, G.; et al. Green Edge Ice Camp Campaigns: Understanding the Processes Controlling the Under-Ice Arctic Phytoplankton Spring Bloom. Earth System Science Data 2020, 12, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.B.; Morrow, J.H.; Matsuoka, A. Apparent Optical Properties of the Canadian Beaufort Sea Part 2: The 1% and 1 Cm Perspective in Deriving and Validating AOP Data Products. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 4511–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, D.; Hooker, S.; Bélanger, S.; Matsuoka, A.; Babin, M. Apparent Optical Properties of the Canadian Beaufort Sea 1: Observational Overview and Water Column Relationships. Biogeosciences (Online) 2013, 10, 4493–4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heukelem, L.; Thomas, C.S. Computer-Assisted High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method Development with Applications to the Isolation and Analysis of Phytoplankton Pigments. Journal of Chromatography A 2001, 910, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ras, J.; Claustre, H.; Uitz, J. Spatial Variability of Phytoplankton Pigment Distributions in the Subtropical South Pacific Ocean: Comparison Between in Situ and Predicted Data. Biogeosciences 2008, 5, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.B.; Zibordi, G. Platform Perturbations in Above-Water Radiometry. Applied Optics 2005, 44, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, R.A.; Stramski, D.; Neukermans, G. Optical Backscattering by Particles in Arctic Seawater and Relationships to Particle Mass Concentration, Size Distribution, and Bulk Composition: Particle Backscattering in Arctic Seawater. Limnology and Oceanography 2016, 61, 1869–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricaud, A.; Babin, M.; Claustre, H.; Ras, J.; Tièche, F. Light Absorption Properties and Absorption Budget of Southeast Pacific Waters. Journal of Geophysical Research 2010, 115, C08009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Matrai, P.A.; Friedrichs, M.A.M.; Saba, V.S.; Ardyna, M.; Babin, M.; Gosselin, M.; Hirawake, T.; Kang, S.-H.; Lee, S.H. Water Temperature, Primary Productivity-Phytoplankton, Chlorophyll-a Concentration, and Other Data Collected by CTD, Scintillation Counter, Fluorometer, and Other Instruments from Arctic Ocean from 1959-08-03 to 2011-10-21 (NCEI Accession 0161176) 2018.

- Matsuoka, A.; Hooker, S.B.; Bricaud, A.; Gentili, B.; Babin, M. Estimating Absorption Coefficients of Colored Dissolved Organic Matter (CDOM) Using a Semi-Analytical Algorithm for Southern Beaufort Sea Waters: Application to Deriving Concentrations of Dissolved Organic Carbon from Space. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Grant, M. Ocean Colour Algorithm Blending 2016.

- Lewis, K.; Van Dijken, G.; Arrigo, K. Bio-Optical Database of the Arctic Ocean 2020, 63356799 bytes.

- Garver, S.A.; Siegel, D.A. Inherent Optical Property Inversion of Ocean Color Spectra and Its Biogeochemical Interpretation: 1. Time Series from the Sargasso Sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1997, 102, 18607–18625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seegers, B.N.; Stumpf, R.P.; Schaeffer, B.A.; Loftin, K.A.; Werdell, P.J. Performance Metrics for the Assessment of Satellite Data Products: An Ocean Color Case Study. Optics Express 2018, 26, 7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legendre, P. Model II Regression User’s Guide, r Edition. R Vignette 1998, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Pabi, S.; van Dijken, G.L.; Arrigo, K.R. Primary Production in the Arctic Ocean, 1998. Journal of Geophysical Research 2008, 113, C08005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrette, M.; Yool, A.; Quartly, G.D.; Popova, E.E. Near-Ubiquity of Ice-Edge Blooms in the Arctic. Biogeosciences Discussions 2010, 7, 8123–8142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardyna, M.; Babin, M.; Gosselin, M.; Devred, E.; Bélanger, S.; Matsuoka, A.; Tremblay, J.-É. Parameterization of Vertical Chlorophyll a in the Arctic Ocean: Impact of the Subsurface Chlorophyll Maximum on Regional, Seasonal, and Annual Primary Production Estimates. Biogeosciences (Online) 2013, 10, 4383–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, T.; Gallegos, C.L. Modelling Primary Production. Springer 1980, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, A. Available Usable and Stored Radiant Energy in Relation to Marine Photosynthesis. Deep Sea Research 1978, 25, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessen, D.O.; Carroll, J.; Kjeldstad, B.; Korosov, A.A.; Pettersson, L.H.; Pozdnyakov, D.; Sørensen, K. Input of Organic Carbon as Determinant of Nutrient Fluxes, Light Climate and Productivity in the Ob and Yenisey Estuaries. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2010, 88, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cota, G.F.; Ruble, D.A. Absorption and Backscattering in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. Journal of Geophysical Research 2005, 110, C04014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, S.; Babin, M.; Larouche, P. An Empirical Ocean Color Algorithm for Estimating the Contribution of Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter to Total Light Absorption in Optically Complex Waters. Journal of Geophysical Research 2008, 113, C04027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.B.; Bélanger, S.; Larouche, P. Evaluation of Ocean Color Algorithms in the Southeastern Beaufort Sea, Canadian Arctic: New Parameterization Using SeaWiFS, MODIS, and MERIS Spectral Bands. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2012, 38, 535–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.M.; Mitchell, B.G.; van Dijken, G.L.; Arrigo, K.R. Regional Chlorophyll a Algorithms in the Arctic Ocean and Their Effect on Satellite-Derived Primary Production Estimates. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2016, 130, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Station | Year | Month | Region | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALINA | 37 | 2009 | July-August | Southern Beaufort Sea | SeaBASS |

| ICESCAPE2010 | 34 | 2010 | June-July | Chukchi and Beaufort Sea | SeaBASS |

| ICESCAPE2011 | 16 | 2011 | June-July | Chukchi and Beaufort Sea | SeaBASS |

| TARA | 27 | 2013 | May-November | Polar circle | SeaBASS |

| GREEN EDGE | 34 | 2016 | June-July | Baffin Bay | Individual |

| PPARR | 973 | 1959-2011 | August | Arctic Ocean | NOAA NCEI |

| Water type | Threshold | Number |

|---|---|---|

| chl.acdm | ≤ 0.067 m-1 | 48 |

| CHL.acdm | ≤ 0.067 m-1 | 26 |

| chl.ACDM | > 0.067 m-1 | 26 |

| CHL.ACDM | > 0.067 m-1 | 48 |

| Algorithms | Blue | Green | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC3Mv6 | 443>488 | 547 | 0.2424 | -2.7423 | 1.8017 | 0.0015 | -1.2280 |

| OC3V | 443>486 | 551 | 0.2228 | -2.4683 | 1.5867 | -0.4275 | -0.7768 |

| OC4v6 | 443>490>510 | 555 | 0.3272 | -2.9940 | 2.7218 | -1.2259 | -0.5683 |

| OC4P | 443>490>510 | 555 | 0.2710 | -6.2780 | 26.29 | -60.94 | 45.31 |

| OC4L | 443>490>510 | 555 | 0.5920 | -3.6070 | - | - | - |

| AO.emp | 443>490>510 | 555 | 0.1746 | -2.8293 | 0.6592 | - | - |

| Algorithm | n | bias | MAE | Overall Wins (%) | r2 | slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC3Mv6 | 148 | 2.22 | 2.68 | 48.9 | 0.49 | 0.86 |

| OC3V | 148 | 2.17 | 2.64 | 48.0 | 0.49 | 0.83 |

| OC4v6 | 148 | 2.32 | 2.75 | 37.2 | 0.52 | 0.83 |

| OC4P | 112 | 1.08 | 3.16 | 38.8 | 0.21 | 1.61 |

| OC4L | 148 | 2.30 | 2.82 | 43.2 | 0.55 | 1.28 |

| AO.emp | 148 | 1.36 | 2.15 | 65.6 | 0.54 | 0.92 |

| GSM01 | 141 | 1.59 | 2.08 | 58.6 | 0.62 | 0.97 |

| AO.GSM | 124 | 1.24 | 1.73 | 58.0 | 0.79 | 0.77 |

| Percent Wins | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | OC3Mv6 | OC3V | OC4v6 | OC4P | OC4L | AO.emp | GSM01 | AO.GSM |

| OC3Mv6 | - | 46.6 | 27.7 | 39.9 | 41.9 | 72.3 | 66.9 | 62.2 |

| OC3V | 53.4 | - | 29.1 | 39.2 | 42.6 | 71.6 | 67.6 | 60.8 |

| OC4v6 | 72.3 | 70.9 | - | 39.2 | 46.6 | 73.0 | 73.0 | 64.9 |

| OC4P | 60.1 | 60.8 | 60.8 | - | 56.1 | 67.6 | 60.8 | 55.4 |

| OC4L | 58.1 | 57.4 | 53.4 | 43.9 | - | 67.6 | 63.5 | 53.4 |

| AO.emp | 27.7 | 28.4 | 27.0 | 32.4 | 32.4 | - | 42.6 | 50.0 |

| GSM01 | 33.1 | 32.4 | 27.0 | 37.2 | 36.5 | 57.4 | - | 59.5 |

| AO.GSM | 37.8 | 39.2 | 35.1 | 39.9 | 46.6 | 50.0 | 35.8 | - |

| Overall Wins | 48.9 | 48.0 | 37.2 | 38.8 | 43.2 | 65.6 | 58.6 | 58.0 |

| Failure | 36 (24.3%) | 7 (4.7%) | 24 (16.2%) | |||||

| Water Type | Algorithm | n | bias | MAE | Wins (%) | Failure | r2 | slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chl.acdm | GSM01 | 48 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 6.2 | 0.71 | 0.85 | |

| AO.GSM | 48 | 1.74 | 1.78 | 93.8 | 0.75 | 0.92 | ||

| CHL.acdm | GSM01 | 26 | 0.83 | 1.33 | 69.2 | 0.52 | 1.09 | |

| AO.GSM | 26 | 0.74 | 1.41 | 30.8 | 0.50 | 1.11 | ||

| chl.ACDM | GSM01 | 24 | 2.10 | 2.72 | 34.6 | 2 (7.7%) | 0.08 | 1.03 |

| AO.GSM | 15 | 2.02 | 2.02 | 57.7 | 11 (42.3%) | 0.65 | 1.25 | |

| CHL.ACDM | GSM01 | 43 | 1.57 | 2.45 | 47.9 | 5 (10.4%) | 0.27 | 1.03 |

| AO.GSM | 35 | 0.92 | 1.81 | 41.7 | 13 (27.1%) | 0.47 | 0.79 | |

| Across all | GSM01 * | 124 | 1.47 | 1.81 | 29.0 | 0.80 | 0.81 | |

| AO.GSM | 124 | 1.24 | 1.73 | 71.0 | 0.79 | 0.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).