1. Introduction

According to United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), there are currently 37.9 million individuals worldwide living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus type-1 (HIV)/ Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), and approximately 22 million are undergoing highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)[

1]. Those infected with HIV and receiving HAART experience an increased life expectancy, marked by a reduced occurrence of AIDS-related morbidity and mortality[

1].

While the treatment has proven highly effective in suppressing viremia[

2], addressing the persistence of HIV in latent tissue reservoirs remains a significant hurdle for long-term management[

3,

4].

HIV primarily targets cells within the lymphoid and myeloid lineages, such as T-helper lymphocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Within these cells, the virus genome is retrotranscribed, and then integrated into the host DNA, forming the provirus[

5]. HIV persists in reservoirs that are largely resistant to the effects of HAART[

6]. Viral reservoirs mainly consist of CD4+ T cells but also macrophages containing transcriptionally silent yet potentially inducible replication-competent proviruses located in multiple anatomical sites wherein replication-competent forms of the virus endure with more stable kinetic properties than in the primary pool of actively replicating virus. However, these host cells are also transcriptionally programmed to enter a quiescent state, which is conducive to HIV latency. Interestingly, the presence of myeloid cells in co-culture with activated HIV-infected T cells may enhance their transition to a post-activation state of latency, underscoring the role of cell-to-cell contact in the establishment of HIV latency[

7].

Better understanding of host factors and physiological signaling pathways governing latency and reactivation within HIV reservoirs in tissues could pave the way for the development of safer and more efficacious therapeutic approaches for individuals living with HIV[

8].

Due to a common mode of transmission through infected human blood, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV co-infection is relatively prevalent, with an estimated 2.3 million individuals globally living with HCV/HIV co-infection[

9].

While HCV primarily targets the liver, chronic HCV infection also involves significant propagation in extrahepatic sites, with detection in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Given that CD4+ T cells serve as the primary site for HIV replication, the co-infection of these cells can give rise to intricate interactions between both viruses[

10,

11].

The sustained presence and renewal of latently infected cells result from various mechanisms, including cellular activation, clonal expansion, and homeostatic processes. These processes may hold specific significance, as they can be modulated within the context of coinfection [

12].

Prior studies have shown that inflamamtion plays a crucial role in the signal-dependent transcription of HIV [

13,

14]. Increased inflammatory response was noted in patients with HCV/HIV co-infection when compared to those with either HCV or HIV mono-infection [

15,

16]. In concordance, HCV co-infection is related to an increased HIV reservoir size in HAART-treated HIV individuals [

17].

The possible mechanisms of interaction between human immunodeficiency virus-infected liver parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells have been studied to understand the development of a fibrotic phenotype [

18]. The presence of HIV provirus in the liver was detected in a human autopsy study, revealing several major HIV reservoir cells, such as resting memory CD4+T lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages [

19].

Hence, our study investigates the interplay between HCV/HIV coinfection in liver cells and its impact on the modulation of HIV viral latency using latently infected cell lines infected with intact virus (J-Lat, and U1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

The spontaneously immortalized human hepatic stellate cell line (LX-2) was generously provided by Dr. Scott L. Friedman (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA). LX-2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies), L-glutamine (2 mM), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. To study HSC transdifferentiation, LX-2 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. The J-Lat 10.6 cell line is a subclone derived from Jurkat-based cells infected with a pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (genus Lentivirus, family Retroviridae) strain, HIV/R7/E−/GFP[

20,

21]. Chronically infected HIV-1 promonocytic (U1) cell lines are clones derived through limiting dilution cloning of U937 cells that survived an acute infection with HIV-1 (LAV-1 strain), initially generated by Folks et al[

22]. Both were obtained from the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS (NIAID, NIH).

THP-1 monocyte cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). THP-1 and J-Lat cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 as previously described. J-Lat and U1 cells were treated with 50 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma Aldrich, Argentina) as a positive control. Additionally, to demonstrate the ability of an inflammatory stimulus as a latency reversal agent, J-Lat cells were co-cultured with THP-1 cells previously stimulated for 4 hours with E. coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Alternatively, culture supernatants from THP-1 cells stimulated with LPS for 4 hours and then cultured for an additional 18 hours were used.

Cocultures of J-Lat: LX-2, J-Lat: Huh7.5, U1: Huh7.5 cells and J-Lat: THP1 cells were performed at 1:1 proportion during 24 and 72 hours. Stimulation of J-Lat with culture supernatants (conditioned medium infected or not) from LX-2, Huh7.5 and THP-1 cells was performed at a 1/2 dilution. Stimulation of U1 with culture supernatants from Huh7.5 conditioned medium infected or not was performed at ½ dilution. Latency viral reversion, was evaluated at 24 and 72 hours post stimulation or cell coculture.

2.2. Viral Stocks

Wild-type (WT) HIV NL43 (X4-tropic) strain was available. We used full-length infectious molecular clones of HIV, pBR-NL4.3 (from Dr. Malcolm Martin), and NLAD8 (from Dr. Eric O. Freed), which were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program (Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, USA) [

23,

24]. The NL43-VSV-G strain was produced through co-transfection with the proviral plasmid in combination with pVSVG to pseudotype envelope-defective viruses with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) glycoprotein G. We co-transfected 293T cells with a VSV-G expression plasmid (pCMV–VSV-G) using an HIV-NL43/VSV-G plasmid ratio of 10:1. After 24 hours, we replaced the culture medium and harvested lentiviral particles at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection. The supernatants were pre-cleared by centrifugation, and ultra-concentrated for 5 hours at 18,000 rpm, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). We stored the concentrated viral particles at -86°C until further use. The quantification of HIV capsid (p24 antigen) in the viral stocks was determined using a commercial ELISA assay (INNOTEST® HIV Antigen mAb). HCV particles were obtained using the J6/JFH clone (from Apath LLC)[

25]. The viral stock was amplified via infection of Huh7.5 cells and harvest culture supernatants. Uninfected culture supernatants were used as control.

HCV RNA load level were determined by quantitative real-time PCR-based cobas® HCV Test. HCV RNA was isolated from 400 µL of culture supernatant using the cobas® 4800 System, which consists of separate devices for sample preparation (cobas x480) and amplification/detection (cobas z480 analyser). The dynamic range of quantification is 15 to 108 IU/mL (1.2-8.0 Log IU/mL). The limit of detection (LoD) is 7.6 IU/mL in serum and 9.2 IU/mL in plasma, and the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) is 15 IU/mL.

2.3. Cellular Infection

LX-2 cells were challenged with pseudotyped HIV co-expressing the G glycoprotein from vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G-HIV). All experiments were conducted in a BSL-3 laboratory at INBIRS. In accordance with institutional rules, all biological materials are mandatory for autoclaving before disposal through incineration. Incineration is carried out in a high-temperature incinerator.

LX-2 cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells per well in 24-well plates and exposed to an HIV inoculum of 0.5 pg of p24 per cell. Huh7.5 cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells per well in 24-well plates and exposed to HCV a multiplicity of infection of 1.

After 4 hours of virus exposure at 37°C, the cells were washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove unabsorbed virus and then incubated in fresh culture medium at 37°C. Culture supernatants from infected and uninfected cells were harvested at 24 and 72 hours post infection and stored at -70°C ultil use.

2.4. Determination of HIV Latency Reversal

Latency reversal was determined through flow cytometry, measuring the percentage of cells positive for enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) in J-Lat 10.6 cells. In the case of U1 cells, latency reversion was assessed by quantifying intracellular P24 expression, utilizing the KC57 monoclonal antibody labeled with phycoerythrin against p24, known as PE-KC57 (Beckman Coulter, United States).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed wherever applicable. Multiple comparisons between all pairs of groups were made using Tukey’s test, and those between two groups were made using MannWhitney U test. Graphical and statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Each experiment was performed in triplicate with different culture preparations on five independent occasions. Data were represented as mean± SD measured in triplicate from three individual experiments. A p < 0.05 is represented as *, p < 0.01 as **, p < 0.001 as ***, and p < 0.0001 as ****. A statistically significant difference between groups was accepted at a minimum level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

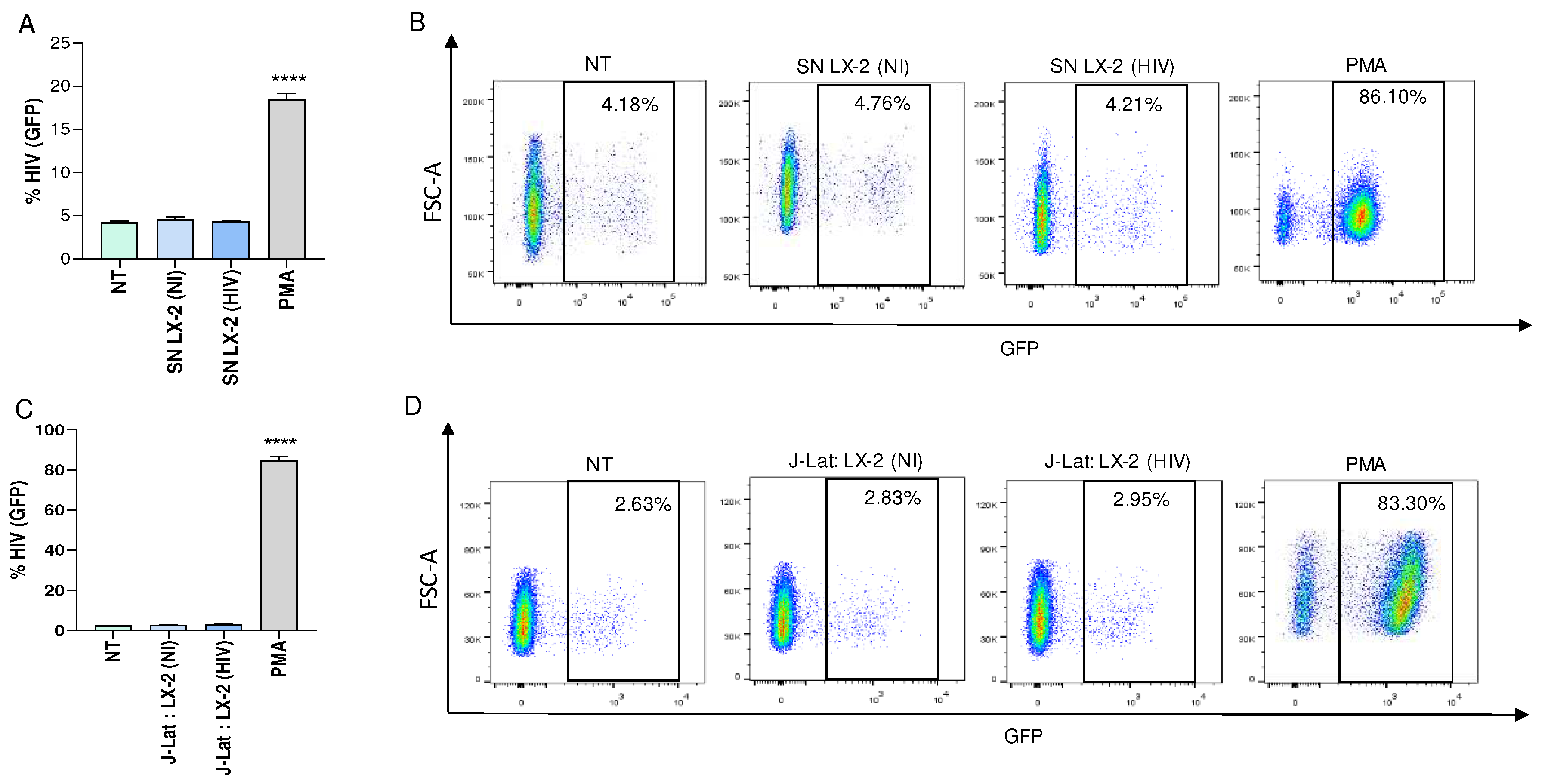

3.1. HIV-Infected Hepatic Stellate cells (LX-2) Were not Able to Reverse Viral Latency in J-Lat Cells

As previously mentioned, HIV genomic RNA levels increase in the serum of patients with liver involvement. HIV infection results in the modulation of cytokines, which play a role in regulating the homeostasis of the immune system[

26,

27,

28].

To investigate the modulation of viral latency reversal, culture supernatants from VSV-G-HIV-infected LX-2 cells obtained at 24 and 72 hours post infection were used to stimulate a latently infected T cell line, J-Lat during 24 and 72 hours. Our results showed that conditioned media from HIV-infected LX-2 cells were unable to reverse viral latency in J-Lat cells (

Figure 1A and B, and not shown).

Additionally, co-culturing HIV-infected LX-2 cells with J-Lat cells during 24 and 72 hours were also unable to reverse viral latency (

Figure 1C and D, and not shown). However, J-Lat cells were capable of reversing latency when stimulated with PMA, which served as a positive control (

Figure 1).

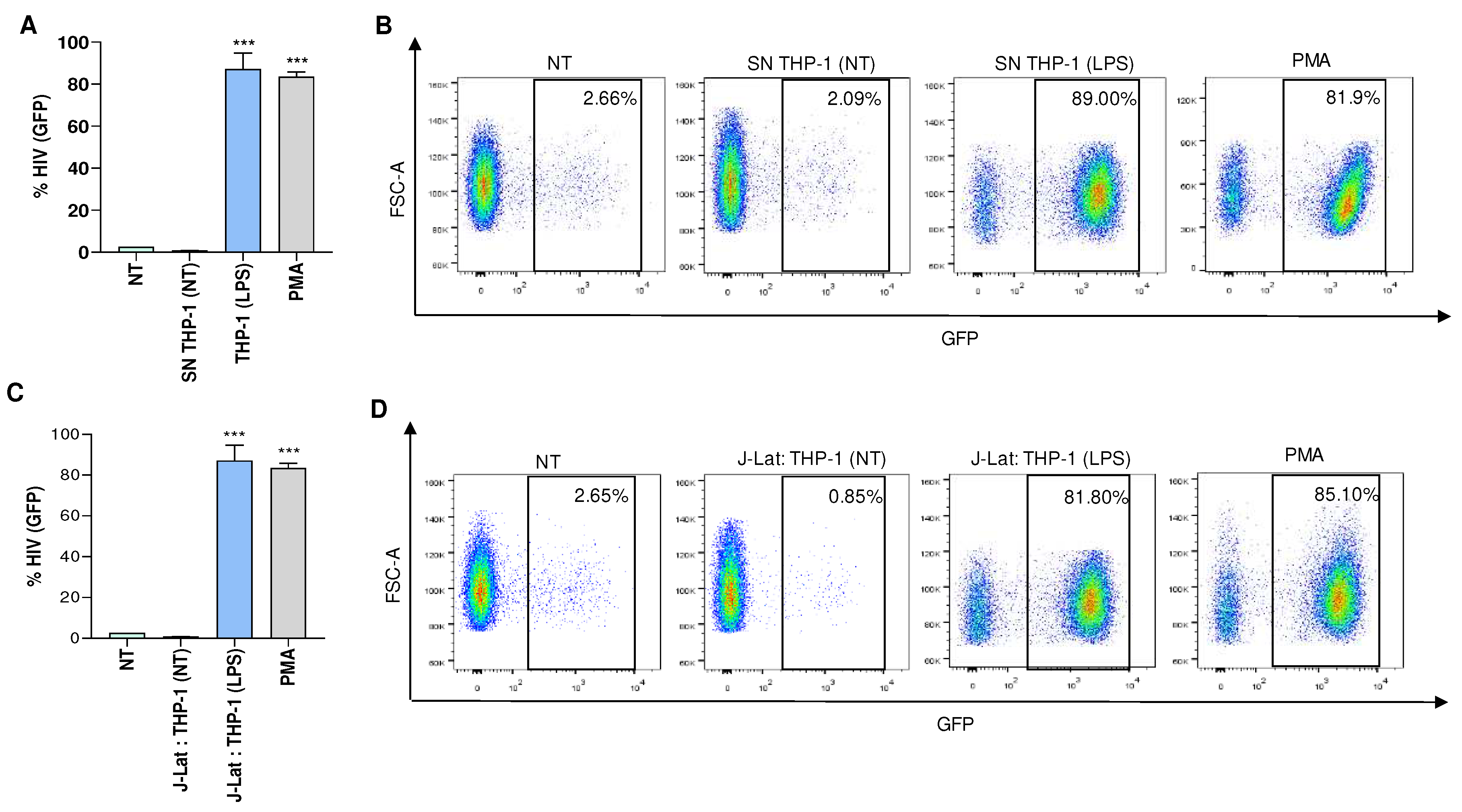

Furthermore, viral latency was reversed when J-Lat cells were co-cultured with LPS-treated monocytes (THP-1 cells), or exposed to culture supernatants from THP-1 cells that were previously stimulated with LPS (

Figure 2). These findings suggest that a similar approach, but with the induction of appropriate stimuli, could potentially reverse viral latency in J-Lat cells.

Taken together our results indicated that that neither the soluble mediators released by HIV-infected HSCs nor cell to cell contact are capable of promoting latency reversal.

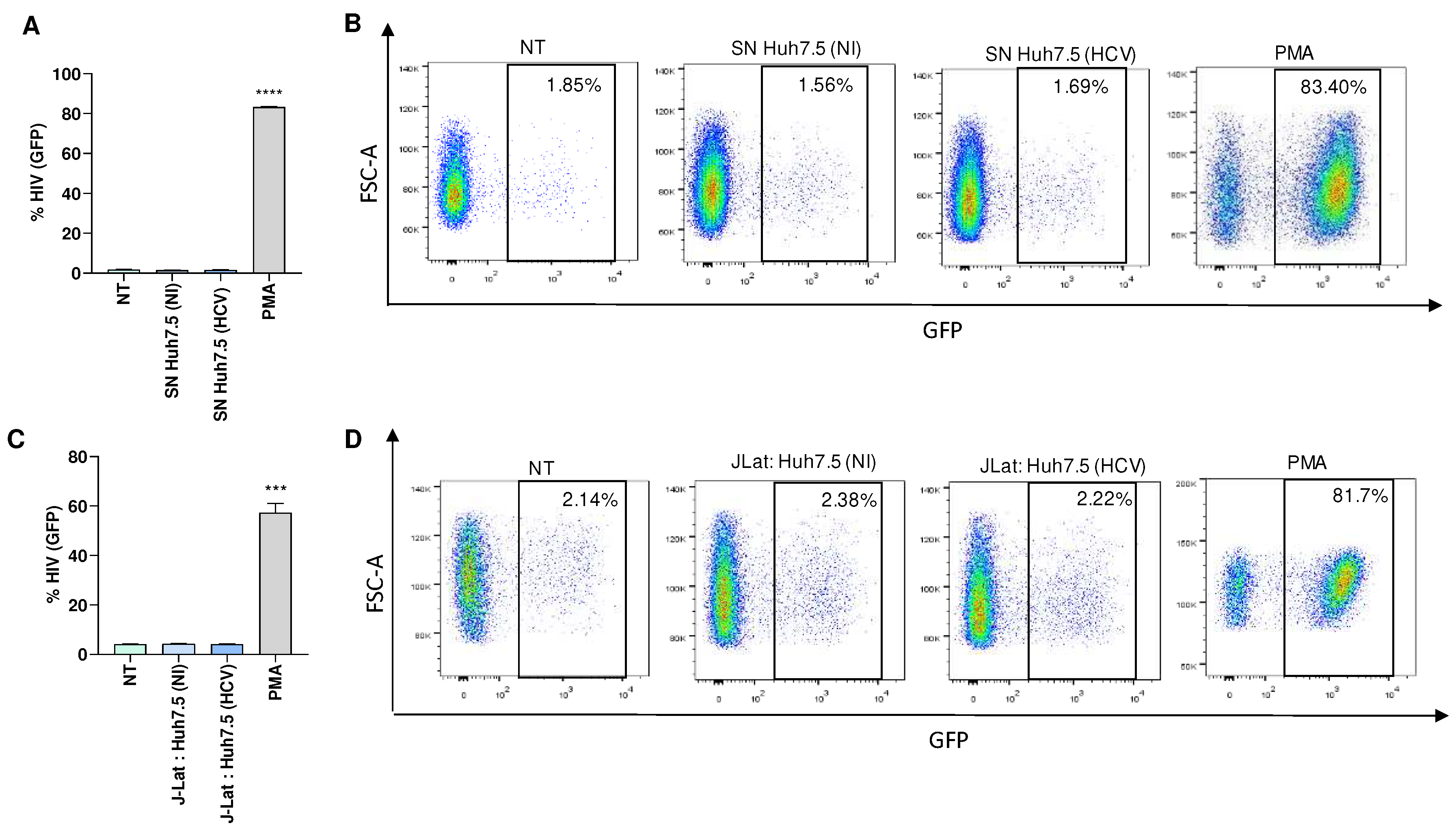

3.2. HCV-Infected Hepatocytes (Huh7.5 Cells) Were not Able to Reverse Viral Latency in J-Lat Cells and U1 Cells

To determine the role of HCV in modulating latency reversion, Huh7.5 cells were infected with HCV, and culture supernatants were collected 24 and 72 hours post-infection. J-Lat cells were then stimulated during 24 and 72 hours with culture supernatants from HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells to investigate the possibility of latency reversion. Culture supernatants from uninfected Huh7.5 cells served as a control. Our results indicated that culture supernatants from HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells were unable to induce latency reversion in J-Lat cells (

Figure 3A and B, and not shown). However, J-Lat cells were capable of reversing latency when stimulated with PMA, serving as a positive control (

Figure 3). Additionally, co-culturing HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells with J-Lat cells also failed to reverse viral latency (

Figure 3C and D).

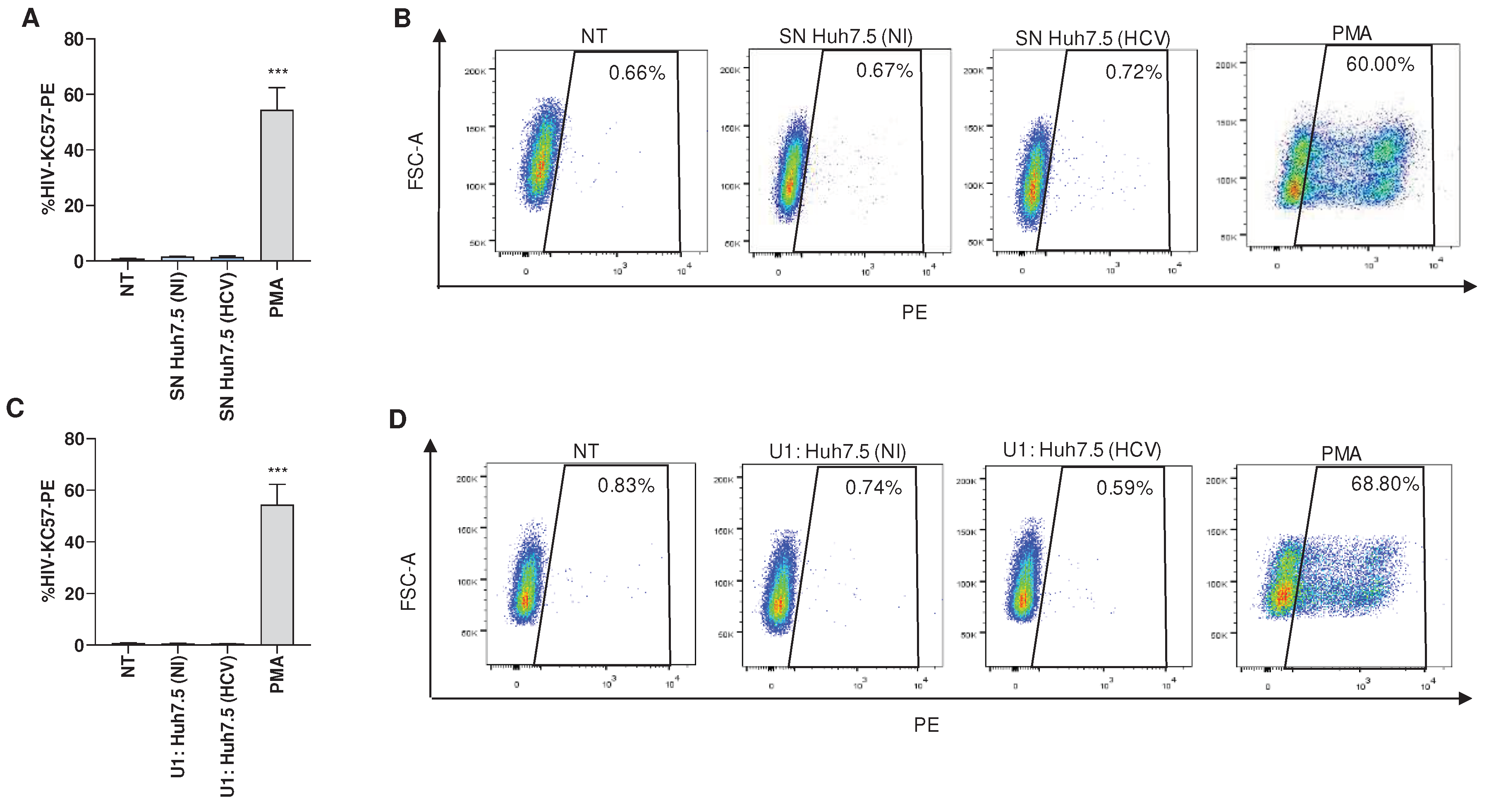

Besides CD4+ T lymphocytes, cells of the myeloid lineage, especially macrophages, are believed to be important for HIV-1 persistence[

29].

An experiment was conducted to determine whether HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells could induce latency reversion in a latently infected monocytic cell, U1. Our results indicated that culture supernatants from HCV-infected Huh7.5 obtained at 24 and 72 hours post-infection were unable to induce latency reversion in U1 cells stimulated during 24 or 72 hours. Additionally, supernatants from uninfected Huh7.5 cells or co-culture of uninfected cells with U1 had no effect (

Figure 4A and B). Alternatively, co-culture between HCV-infected Huh7.5 and U1 also failed to induce latency reversion at 24 and 72 hours post coculture (

Figure 4C and D). However, latency reversion was observed when U1 cells were stimulated with PMA (

Figure 4). Additionally, supernatants from uninfected Huh7.5 cells or co-culture of uninfected cells with U1 had no effect.

Collectively, our findings indicate that neither the soluble mediators released by HCV-infected Huh7.5 cells nor the ligands expressed on the membrane of these cells are able to promote latency reversal.

4. Discussion

Owing to a common mode of transmission through infected human blood, co-infection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are relatively prevalent, affecting an estimated 2.3 million people worldwide[

9].

In a recent study, a larger size of the HIV reservoir in resting CD4+ T cells was observed among individuals with HCV/HIV coinfection who were undergoing ART treatment. This trend was evident in both individuals with chronic HCV and those who had spontaneously resolved HCV, as compared to subjects infected with HIV alone[

17]. Likewise, studies have reported that coinfection with HCV influences the progression of HIV disease in people living with HIV (PLWH) who are undergoing antiretroviral therapies (HAART). In cases of HCV coinfection, there is a detrimental impact on the homeostasis of CD4+ T cell counts, facilitating HIV replication and contributing to the persistence of viral reservoirs[

30].

Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the pivotal role of latently-infected cells in the persistence, propagation, and dissemination of HIV[

13,

14,

18]. Despite the effectiveness of systemic HAART in reducing plasma viral load, it primarily focuses on this aspect and does not specifically target latently-infected cells within anatomical reservoirs[

31]. The factors that intricately regulate the latency and/or reactivation of HIV within microenvironments of reservoirs remain poorly understood. Liver cells is well-established for their interactions with both macrophages and T-cells, influencing their activation phenotype[

32,

33]. It has been previously demonstrated that hepatic stellate cells and hepatocytes secrete soluble mediators in response to HIV and HCV infection, respectively[

34,

35,

36]. The balance between the pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators create a microenvironment that could be involved in reactivation or maintenance of HIV latency.

Additionally, latency reversion could be modulated by cell to cell contact in a way dependent on the cell involved and the state of activation. It has been demonstrated that interactions between monocytes/dendritic cells and latently HIV-infected T cells play a crucial role in reversing latency. Conversely, a post-activation T cell latency model, when in contact with monocytes and subjected to anti-CD3 stimulation, demonstrated a reduction in virus expression[

37].

Hence, undertaking further studies to define the specific roles of soluble mediators and cell-cell contact receptors in the maintenance and reactivation of latency could potentially result in a significant breakthrough in understanding the mechanisms that contribute to the modulation of the viral reservoir.

Our findings, employing the latently-infected monocytic cell line (U1) and the latently-infected T cell line (J-Lat) revealed that the cytokines produced by the infection of hepatic stellate cells and hepatocytes with HIV and HCV, respectively were unable to induce latency reversal under the conditions studied, indicating that the microenvironment induced by direct viral interaction with hepatic cells are not responsible for latency reversal.

The liver serves as a secondary lymphoid organ, hosting a significant population of CD4+ T cells and boasting the largest concentration of tissue-resident macrophages in the body. Consequently, the liver might act as a reservoir for HIV, as both HIV DNA and RNA have been detected in human hepatocytes and liver macrophages, persisting even when suppressive HAART is administered. Yet, it is conceivable that the liver microenvironment, particularly in hepatocytes, as opposed to CD4+ T cells with diverse activation statuses, may be favorable to latency[

38,

39,

40].

Additionally, a point to consider is that in the conditioned medium from HIV-infected hepatic stellate cells, there would release HIV wild type, which is lymphotropic and, although it should have replicative capacity, fails to become a "stimulus" for latently infected J-Lat cells.

Monocytes, which harbor replication-competent virus, have the potential to replenish tissue macrophage reservoirs upon leaving the bloodstream and undergoing differentiation into monocyte-derived macrophages [

41]. Furthermore, due to their ability to transmigrate into tissue compartments, macrophages are implicated in viral dissemination to multiple anatomical sites[

42,

43]. However, our experiments indicated that HCV-infected hepatocytes were unable to reverse the latency in U1 cells.

Further investigations are needed to elucidate the role of the interaction between liver cells in regulating HIV latency and/or reactivation, aiming to provide a physiologically relevant model for understanding the reservoir microenvironments in vivo.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Q., and M.V.D.; methodology C.A.M.L., R.N.F., and F.A.S investigation. C.A.M.L., R.N.F., and F.A.S, writing original draft preparation, M.V.D.; writing—review and editing, J.Q., and M.V.D.; funding acquisition, J.Q., and M.V.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Agencia Nacional of Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCYT, Argentina), PICT 2019-0499, PICT 2020-0691 to MVD and PICT-2019-1698, PICT 2020-1173 to JQ, and Universidad de Buenos Aires (SECyT). Funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Back, D.; Marzolini, C. The challenge of HIV treatment in an era of polypharmacy. J Int AIDS Soc 2020, 23, e25449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnighausen, T.; Bloom, D.E.; Humair, S. Human Resources for Treating HIV/AIDS: Are the Preventive Effects of Antiretroviral Treatment a Game Changer? PloS one 2016, 11, e0163960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, K.M.; Palmer, S.E. How to Define the Latent Reservoir: Tools of the Trade. Current HIV/AIDS reports 2016, 13, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlama, C.; Deeks, S.G.; Autran, B.; Martinez-Picado, J.; van Lunzen, J.; Rouzioux, C.; Miller, M.; Vella, S.; Schmitz, J.E.; Ahlers, J.; et al. Barriers to a cure for HIV: new ways to target and eradicate HIV-1 reservoirs. Lancet 2013, 381, 2109–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, B.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Q. HIV Tissue Reservoirs: Current Advances in Research. AIDS patient care and STDs 2023, 37, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamel, J.; Bruggemans, A.; Debyser, Z. Establishment of latent HIV-1 reservoirs: what do we really know? Journal of virus eradication 2019, 5, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C.; Gantner, P.; Fromentin, R.; Chomont, N. The multifaceted nature of HIV latency. The Journal of clinical investigation 2020, 130, 3381–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, G.; Singh, N.J. Modular Approaches to Understand the Immunobiology of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Latency. Viral immunology 2021, 34, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, L.; Easterbrook, P.; Gower, E.; McDonald, B.; Sabin, K.; McGowan, C.; Yanny, I.; Razavi, H.; Vickerman, P. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2016, 16, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskus, T.; Radkowski, M.; Piasek, A.; Nowicki, M.; Horban, A.; Cianciara, J.; Rakela, J. Hepatitis C virus in lymphoid cells of patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: evidence of active replication in monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes. The Journal of infectious diseases 2000, 181, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackard, J.T.; Smeaton, L.; Hiasa, Y.; Horiike, N.; Onji, M.; Jamieson, D.J.; Rodriguez, I.; Mayer, K.H.; Chung, R.T. Detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in serum and peripheral-blood mononuclear cells from HCV-monoinfected and HIV/HCV-coinfected persons. The Journal of infectious diseases 2005, 192, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcis, G.; Bouchat, S.; Kula, A.; Van Driessche, B.; Delacourt, N.; Vanhulle, C.; Avettand-Fenoel, V.; De Wit, S.; Rohr, O.; Rouzioux, C.; et al. Reactivation capacity by latency-reversing agents ex vivo correlates with the size of the HIV-1 reservoir. Aids 2017, 31, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabel, G.; Baltimore, D. An inducible transcription factor activates expression of human immunodeficiency virus in T cells. Nature 1987, 326, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, J.C.; Oltman, A.; Han, A.; Bates, D.L.; Chen, L. Structural basis of HIV-1 activation by NF-kappaB--a higher-order complex of p50:RelA bound to the HIV-1 LTR. Journal of molecular biology 2009, 393, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, L.E.; Wendelboe, A.M.; Lazzeroni, L.C.; Chary, A.; Winters, M.A.; Osinusi, A.; Kottilil, S.; Polis, M.A.; Holodniy, M. Immune biomarker differences and changes comparing HCV mono-infected, HIV/HCV co-infected, and HCV spontaneously cleared patients. PloS one 2013, 8, e60387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, M.; Romero-Cores, P.; Montes-Oca, M.; Martin-Aspas, A.; Soto-Cardenas, M.J.; Guerrero, F.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, C.; Giron-Gonzalez, J.A. Immune activation response in chronic HIV-infected patients: influence of Hepatitis C virus coinfection. PloS one 2015, 10, e0119568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Huertas, M.R.; Palladino, C.; Garrido-Arquero, M.; Esteban-Cartelle, B.; Sanchez-Carrillo, M.; Martinez-Roman, P.; Martin-Carbonero, L.; Ryan, P.; Dominguez-Dominguez, L.; Santos, I.L.; et al. HCV-coinfection is related to an increased HIV-1 reservoir size in cART-treated HIV patients: a cross-sectional study. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M.; Poluektova, L.Y.; Kharbanda, K.K.; Osna, N.A. Liver as a target of human immunodeficiency virus infection. World journal of gastroenterology 2018, 24, 4728–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaillon, A.; Gianella, S.; Dellicour, S.; Rawlings, S.A.; Schlub, T.E.; De Oliveira, M.F.; Ignacio, C.; Porrachia, M.; Vrancken, B.; Smith, D.M. HIV persists throughout deep tissues with repopulation from multiple anatomical sources. The Journal of clinical investigation 2020, 130, 1699–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Bisgrove, D.; Verdin, E. HIV reproducibly establishes a latent infection after acute infection of T cells in vitro. The EMBO journal 2003, 22, 1868–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniasz, P.D.; Cullen, B.R. Multiple blocks to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in rodent cells. Journal of virology 2000, 74, 9868–9877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folks, T.M.; Justement, J.; Kinter, A.; Dinarello, C.A.; Fauci, A.S. Cytokine-induced expression of HIV-1 in a chronically infected promonocyte cell line. Science 1987, 238, 800–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, A.; Gendelman, H.E.; Koenig, S.; Folks, T.; Willey, R.; Rabson, A.; Martin, M.A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. Journal of virology 1986, 59, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, E.O.; Englund, G.; Martin, M.A. Role of the basic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix in macrophage infection. Journal of virology 1995, 69, 3949–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, G.; Donis, R.O.; Wakita, T.; Bukh, J.; Grakoui, A. Intragenotypic JFH1 based recombinant hepatitis C virus produces high levels of infectious particles but causes increased cell death. Virology 2008, 376, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hokello, J.; Sharma, A.L.; Dimri, M.; Tyagi, M. Insights into the HIV Latency and the Role of Cytokines. Pathogens 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, N.E.; Lane, B.R.; Bock, P.J.; Markovitz, D.M. Protein phosphatase 2A enhances activation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by phorbol myristate acetate. Journal of virology 2003, 77, 2276–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, G.; Bressler, P.; Kinter, A.; Duh, E.; Timmer, W.C.; Rabson, A.; Justement, J.S.; Stanley, S.; Fauci, A.S. Interleukin 6 induces human immunodeficiency virus expression in infected monocytic cells alone and in synergy with tumor necrosis factor alpha by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. The Journal of experimental medicine 1990, 172, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruize, Z.; Kootstra, N.A. The Role of Macrophages in HIV-1 Persistence and Pathogenesis. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobran, S.T.; Ancuta, P.; Shoukry, N.H. A Tale of Two Viruses: Immunological Insights Into HCV/HIV Coinfection. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 726419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, D.M.; Archin, N.M.; Cohen, M.S.; Eron, J.J.; Ferrari, G.; Garcia, J.V.; Gay, C.L.; Goonetilleke, N.; Joseph, S.B.; Swanstrom, R.; et al. Curing HIV: Seeking to Target and Clear Persistent Infection. Cell 2020, 181, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Lambrecht, J.; Ju, C.; Tacke, F. Hepatic macrophages in liver homeostasis and diseases-diversity, plasticity and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficht, X.; Iannacone, M. Immune surveillance of the liver by T cells. Sci Immunol 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1655–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Tao, W.; Xiang, Y.; Huang, B.; Niu, J.; Zhong, J.; Meng, G. HCV genomic RNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human myeloid cells. PloS one 2014, 9, e84953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S.; Holmes, J.A.; Jindal, R.; Bale, S.S.; Brisac, C.; Alatrakchi, N.; Lidofsky, A.; Kruger, A.J.; Fusco, D.N.; Luther, J.; et al. Exposure to human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus in hepatic and stellate cell lines reveals cooperative profibrotic transcriptional activation between viruses and cell types. Hepatology 2016, 64, 1951–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.D.; Lu, H.K.; Chang, J.J.; Rhodes, A.; Lewin, S.R.; Cameron, P.U. The Pathway To Establishing HIV Latency Is Critical to How Latency Is Maintained and Reversed. Journal of virology 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandathil, A.J.; Sugawara, S.; Goyal, A.; Durand, C.M.; Quinn, J.; Sachithanandham, J.; Cameron, A.M.; Bailey, J.R.; Perelson, A.S.; Balagopal, A. No recovery of replication-competent HIV-1 from human liver macrophages. The Journal of clinical investigation 2018, 128, 4501–4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispe, I.N. Immune tolerance in liver disease. Hepatology 2014, 60, 2109–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.Z.; Dieterich, D.; Thomas, P.A.; Huang, Y.X.; Mirabile, M.; Ho, D.D. Identification and quantitation of HIV-1 in the liver of patients with AIDS. Aids 1992, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhuis, R.T.; Abreu, C.M.; Costa, P.A.G.; Ferreira, E.A.; Ratliff, J.; Pohlenz, L.; Shirk, E.N.; Rubin, L.H.; Blankson, J.N.; Gama, L.; et al. Monocyte-derived macrophages contain persistent latent HIV reservoirs. Nature microbiology 2023, 8, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulcher, J.A.; Hwangbo, Y.; Zioni, R.; Nickle, D.; Lin, X.; Heath, L.; Mullins, J.I.; Corey, L.; Zhu, T. Compartmentalization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 between blood monocytes and CD4+ T cells during infection. Journal of virology 2004, 78, 7883–7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Sharron, M.; Montaner, L.J.; Weissman, D.; Doms, R.W. Quantification of CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 levels on lymphocyte subsets, dendritic cells, and differentially conditioned monocyte-derived macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1999, 96, 5215–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).