1. Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of the early blastocyst during mammalian development. These ESCs can self-renew almost indefinitely and retain the ability to generate many cell types of the adult mammalian organism under the right conditions in vitro [

1,

2]. Hence, ESCs are a powerful model for studying mammalian development and disease.

Cardiomyocyte insufficiency, resulting from the inability of cardiomyocytes to regenerate, underlies most heart failures [

3,

4,

5]. Therefore,

ex vivo cardiomyocyte generation will significantly contribute to the discovery of novel factors governing the differentiation of cardiomyocytes in mammalian development. Previous methods for differentiating mouse ESCs (mESCs) into cardiomyocytes use growth factors, which are expensive and have short half-lives [

6,

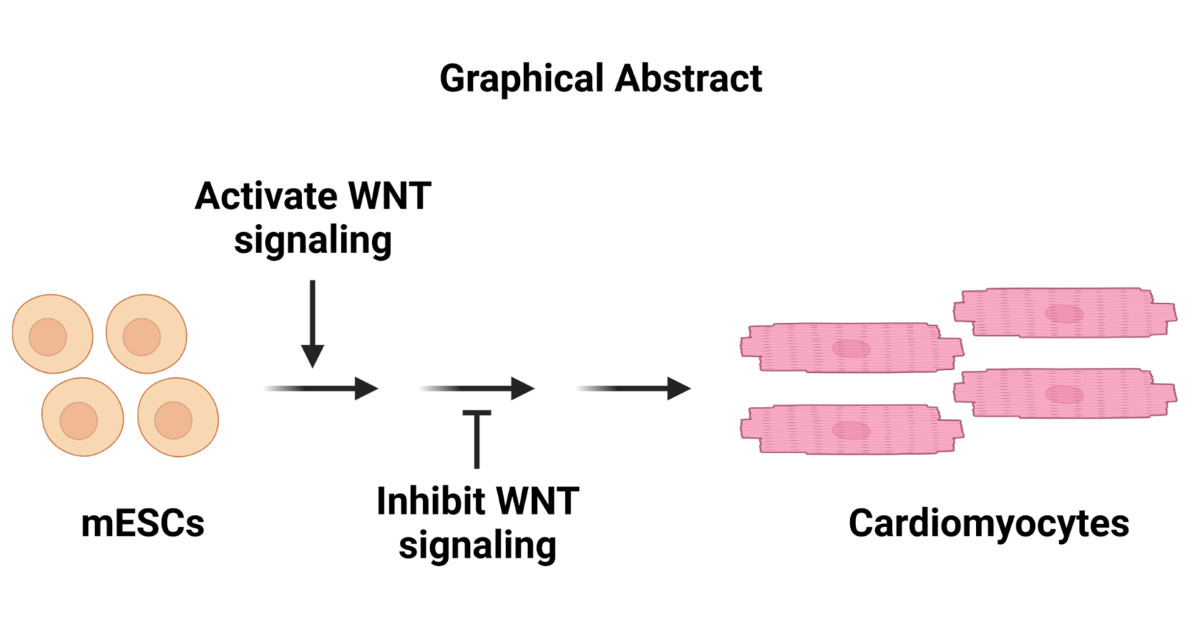

7]. Here, we describe a relatively inexpensive method to efficiently differentiate mESCs into cardiomyocytes based on temporal changes in WNT signaling observed during cardiomyocyte development.

Seminal studies have highlighted the critical role of canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling in cardiac development [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The timing for activation and inhibition of WNT signaling during development is crucial for cardiomyocyte differentiation. This includes the early activation of WNT signaling, promoting the differentiation of ESCs into the mesoderm [

13,

14,

15]. The subsequent inhibition of WNT signaling following mesoderm formation commits mesodermal cells into cardiomyocytes [

16,

17,

18,

19].

In vitro, small molecule inhibitors can efficiently activate and inhibit WNT signaling [

20,

21]. The WNT signaling activator, CHIR99021, inhibits GSK3β (glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta) activity, allowing β-catenin to translocate into the nucleus to turn on WNT signaling target genes [

22,

23]. Similarly, XAV939 is a small molecule that inhibits the WNT signaling pathway by inhibiting TNKS activity, thereby increasing the axin-GSK3β destructive complex to promote phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin [

21,

24]. These small molecule inhibitors are relatively inexpensive and stable and can access cells embedded deeper in tissues, facilitating a uniform and consistent activation of WNT signaling.

Compared to human ESCs (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), mESC differentiation is more frequently used as a mammalian developmental model system for discovering novel mechanisms and factors controlling differentiation and disease. The success of the model system is based on the significant similarities in the early developmental pathways and mechanisms in mammals. Additionally, obtaining and maintaining mESCs are simpler and more affordable than hESCs and hiPSCs and pose fewer administrative tasks [

25]. For cardiomyocyte generation, while other methods have utilized small molecules to activate and inhibit WNT signaling genes in hiPSCs differentiation [

26,

27,

28,

29], these conditions have not been used for mESCs. A recent method used only XAV939 from day 3 to 5 post-differentiation [

30], thereby controlling only the inhibition of WNT signaling. In this study, we describe the “WNT Switch” method that uses small molecule inhibitors to temporally control both the activation and inhibition of WNT signaling to induce differentiation of mESC into cardiomyocytes. The differentiation process was characterized by measuring changes in gene expression using RT-qPCR and Immunofluorescence. The cardiomyocytes generated were monitored for spontaneous contractile activity using bright-field microscopy, and the contractions per minute were measured. We further quantified the efficiency of differentiation in comparison to previously used methods by Fluorescence assisted cell sorting (FACS). The data supports our claim that the “WNT switch” method is robust and generates cardiomyocytes with high efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

CHIR99021 (APExBIO, cat.no. A3011)

XAV939 (Stemcell Technologies, cat.no. 72672)

Trypsin-EDTA (0.25%, wt/vol; Life Technologies, cat.no. 25200-056)

FBS (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. MT35015CV)

E14 mouse embryonic stem cells (ATCC, cat.no. CRL-1821)

NEAA (Thermofisher scientific, cat.no. 11140050)

Sodium pyruvate (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 11360070)

Penicillin-Streptomycin (Thermofisher scientific, cat.no. 15140122)

L-Glutamine (Thermofisher scientific, cat.no. 25030081)

Nonfat dry milk (can be purchased from a local grocery store)

Trypan blue solution (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 15250061)

β-mercaptoethanol (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 21985023)

IMDM (Thermofisher scientific, cat.no. 12440053)

DMEM (Thermofisher scientific, cat.no. 11995065)

Evagreen master mix (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. NC1787870)

cDNA synthesis kit (Meridian Bioscience, cat.no. BIO-65043)

TRIzol® (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 15596026)

Chloroform (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 022920.K2)

DNase I (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 18068015)

DPBS (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 14200075)

Triton X-100 (Millipore, cat.no. T9284)

Ethanol (Millipore, cat.no. 493511)

HEPES (Millipore, cat.no. H4034-25G)

Milli-Q water

Primers for quantitative RT-PCR (

Table S1)

DAPI solution (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 62248)

cTnT antibody (Abcam, cat.no. ab8295)

mouse IgG Alexa Fluor® 488 (Santa Cruz, cat.no. sc-3890)

Gelatin (Sigma, cat.no. G1393-100 mL)

RNase AWAY (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 501978158)

Formaldehyde (Millipore Sigma, cat.no. 252549-100 mL)

PureLink RNA Mini Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, cat.no 12183018A)

Steriflip filtration system (50 mL; Fisher Scientific, cat.no. SCGP00525)

Stericup filtration system (500 mL; Fisher Scientific, cat.no. S2GPT05RE)

Zeiss phase-contrast microscope (Spectra Services; cat.no SKU Axiovert35)

Fluorescence microscope (Biocompare, cat.no. EVOS®FL)

Cell culture plates 100 mm (Corning, cat.no. 430167)

Petri plates 60 mm (Sigma-Aldrich, cat.no. P5481-500EA)

6-well tissue culture plates (Corning, cat.no. 3516)

Tissue culture flask-T25 (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 130189)

Hybex bottle Flasks (1000 mL, 500 mL; Benchmark Scientific, cat.no. B3000-100-B, B3000-500-B)

Falcon conical tubes (50 mL, 15 mL; Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 14-432-22, 14-959-53A)

Cell lifters (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 08100240)

Centrifuge (Eppendorf, cat.no. 022625080)

Biosafety cabinet (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 13-261-222)

Vacuum Liquid waste disposal system (Welch, cat.no. 2511B-75)

Glass Pasteur pipettes (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 1-678-20D)

Serological pipettes (25 mL, 10 mL, 5 mL; Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 13-676-10M, 13-678-11E, 13-676-10H)

Humidified tissue culture incubators (37 oC, 5% CO2; Eppendorf, cat.no. c170i)

Cell counter slides (BIO-RAD, cat.no. 1450011)

Block heater (Thermofisher Scientific, cat.no. 88870001)

Automated cell counter (BIO-RAD, cat.no. 1450102)

Water bath incubators (Fisher Scientific, cat.no. 15-462-20Q)

Microcentrifuge tubes (1.5 mL; VWR, cat.no. 87003-294)

Water purification system (Millipore Sigma, cat.no. ZRQSVP3WW)

Quantitative-PCR detection system (BIO-RAD, cat.no. 1855201)

qPCR 96-well plates (USA Scientific, cat.no. 1402-8590)

All reagents were prepared in a Biosafety II grade HEPA-filtered biosafety cabinet following UV sterilization for at least 30 minutes. The benchtop was swabbed with 70% ethanol, and anything going into the biosafety cabinet was also swabbed properly with 70% ethanol. All aseptic procedures were strictly enforced to maintain a contamination-free cell culture. The concentrations in the parenthesis below indicate the final working concentration.

1000x β-mercaptoethanol: Mixed 355 μL of stock β-mercaptoethanol with 49.65 mL sterile water under sterile conditions. This solution was filtered with the Steriflip filtration system and stored at 4 oC for up to 2 weeks.

HEPES: We prepared 50 mL of 1 M HEPES with pH 8 by dissolving 11.92 g of HEPES in 40 mL Milli-Q water. After complete dissolution, the pH 8 of the solution was adjusted using 1 M KOH. The volume of the final solution was brought to 50 mL using Milli-Q water and filter sterilized with the Steriflip filtration system under sterile conditions. This solution should be stored at 4 oC.

ES + LIF (Leukemia Inhibitory Factor) Medium: Under sterile conditions, we prepared 1000 mL medium by mixing 804 mL of 1x DMEM, 150 mL of FBS (15 %), 10 mL of L-Glutamine (2 mM), 10 mL of NEAA (1x), 10 mL of sodium pyruvate (1 mM), 10 mL of Pen/Strep (1 mM), 1 mL of β-mercaptoethanol (1x), 1 mL of HEPES (1 mM) and 4 mL of LIF (0.4 %). The medium was filtered with a 500 mL Stericup filtration system over an autoclaved/sterile 1000 mL bottle. This medium can be stored for up to two months at 4 oC.

20% FBS Differentiation Media: Under sterile conditions, we prepared 500 mL medium by mixing 384.5 mL of 1x IMDM, 100 mL of FBS (20%), 5 mL of L-Glutamine (2 mM), 5 mL of NEAA (1x), 5 mL of sodium pyruvate (1 mM) and 500 μL of β-mercaptoethanol (1x). The media was filtered with a 500 mL Stericup filtration system into an autoclaved/sterile 500 mL bottle. This medium should be protected from light and can be stored for a month at 4 oC.

Low FBS Differentiation Media: Under sterile conditions, we prepared 500 mL media by mixing 488.5 mL of 1x IMDM, 1 mL of FBS (0.2%), 5 mL of L-Glutamine (2 mM), 5 mL of NEAA (1 mM), and 500 μL of β-mercaptoethanol (1x). The media was filtered with a 500 mL Stericup filtration system into an autoclaved/sterile 500 mL bottle. This medium should be protected from light and can be stored for a month at 4 oC.

CHIR99021 Media: Under sterile conditions, we aliquoted about 30 μL of CHIR99021 into sterile 1.5 mL sterile microcentrifuge tubes and stored for up to 12 months at -20 oC to prevent freeze-thaw. We added 15 μL of CHIR99021 (3 μM) to 50 mL 20% FBS differentiation medium for differentiation. This media should be freshly prepared and protected from light. The media was filtered through the 50 mL Steriflip filtration system for additional sterility.

XAV939 Media: Under sterile conditions, we prepared a 1 mg/mL solution by adding 1 mL of DMSO to 1 mg of XAV939. We used the 1 mL pipette to mix the solution about 8 to 10 times to ensure complete dissolution of the XAV939 powder. We aliquoted about 20 μL of the 1 mg/mL solution into sterile 1.5 mL sterile microcentrifuge tubes and stored for up to six months at -20 oC to prevent freeze-thaw. We added 15.6 μL of XAV939 (1 μM) to the 50 mL 20% FBS differentiation medium for differentiation. This media should be freshly prepared and protected from light. This media was filtered through the 50 mL Steriflip filtration system for additional sterility.

Gelatin: The gelatin solution was kept briefly in room temperature to thaw. Under sterile conditions, we prepared 100 mL 0.1 % gelatin by diluting 5 mL of sterile stock gelatin with 95 mL of 1x PBS. For an added precaution, we filter sterilized the solution with a 200 mL stericup filtration system into a sterile bottle. Store the solution at 4 oC.

Formaldehyde, 4% (vol/vol): To prepare 5 mL solution, we added 541 μL of 37% formaldehyde into 4.46 mL of 1x PBS in the dark. This solution should be freshly prepared.

PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline): Under sterile conditions, we prepared 1x PBS by mixing 50 mL 10x PBS with 450 mL distilled water. The solution was filtered through a 500 mL stericup filtration system into a sterile 500 mL bottle. PBS should be stored at room temperature.

Blocking solution (5% Nonfat Dry Milk, 0.4% Triton X-100): We added 2.5 g of nonfat dry milk and 400 μL of 50% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 solution into 50 mL of 1x PBS. This solution should be freshly prepared.

PROCEDURE

All the procedures described here were undertaken in a sterile biosafety II tissue culture hood. We strictly followed aseptic techniques to prevent contamination. The UV lamp was used for at least 30 minutes before using the tissue culture hood, and the benchtop was swabbed with 70% ethanol. Anything entering the tissue culture hood was swabbed with 70% ethanol. All pipettes and materials used in the biosafety cabinet were sterile.

2 mL of 0.1% gelatin was added to coat the surface of T25 tissue culture flasks. The excess gelatin solution was aspirated off before seeding ESCs.

We added 9.5 mL of 37 oC ES + LIF media into a 15 mL sterile conical tube.

A frozen vial of mESCs was removed from liquid nitrogen and the vial thawed in a 37 oC water bath. The vial was swirled gently until only a small ice crystal remained in the core of the vial.

The vial was swab with 70% ethanol and placed in the tissue culture hood. Using a sterile 1 mL pipette, we gently transferred the cells into the 15 mL conical tube containing ES + LIF media.

The cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 3 minutes at 1200 rpm in a benchtop centrifuge at room temperature. The supernatant was aspirated and discarded with a sterilized glass Pasteur pipette.

The cell pellet was gently resuspended in 10 mL pre-warmed ES + LIF medium and we transferred the cell suspension into a 25 cm2 tissue culture flask. The cells were grown at 37 oC in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

The cells were distributed evenly in the flask by rocking the flask in a gentle; left, right, up, and down motions.

The next day, the medium was changed with 10 mL ES+LIF medium to remove dead cells and residual DMSO. (Footnote: Pre-warmed media was added perpendicular to the plate to prevent dislodging cells from the tissue culture plate).

- 9.

When ESCs reached about 80-90% confluency (usually about 2 -3 days after thawing), we aspirated the old ES+LIF medium and washed with 10 mL room temperature 1x PBS. The PBS was aspirated and wash repeated one more time. (Footnote: The aspirator pipette was positioned away from the cells at the corner if the flask to prevent dislodging the cells).

- 10.

The cells were covered with 1 mL of trypsin solution and incubated at 37 oC for 1 – 2 minutes for cells to be uniformly dispersed into small clumps and detached from plate surface.

- 11.

We added 9 mL of pre-warmed ES+LIF media to inactivate the trypsin, and gently mixed about 10 times by pipetting up and down using a 10 mL sterile serological pipette.

- 12.

The cells were counted by mixing 10 μL cell suspension with 10 μL trypan blue solution at a 1:1 ratio. 10 μL of the mixture was transferred into the cell counter slide and cells counted using the automated cell counter.

- 13.

3.0 x 106 ESCs were transferred into a gelatin-coated 10 cm tissue culture dish in 10 mL ES+LIF media.

- 14.

After plating the cells, the plate was returned to the incubator. The plate was moved in quick, short, left, right, up, and down motions to evenly disperse the cells across the surface of the plate.

- 15.

The medium was changed the next day by aspirating it and replacing it with a pre-warmed ES+LIF medium.

- 16.

The cells were passaged again after the cells have reached about 80 – 90% confluency by repeating steps 8 – 14 before proceeding with cardiomyocyte differentiation.

- 17.

After the cells have reached 80 – 90% confluency, they can be differentiated into cardiomyocytes. Before performing the steps below, the 20% FBS differentiation medium was prewarmed at 37 oC and supplemented with CHIR990221. This medium was protected from light.

- 18.

Three sterile 10 cm petri plates were filled with about 15 mL of 1x PBS each to flood the base.

- 19.

Steps 8 – 9 were repeated to detach ESCs from the tissue culture plate. The detached cells were resuspended in 10 mL of 20% FBS differentiation medium supplemented with CHIR99021 by gently pipetting up and down 10 times.

- 20.

Cells were counted by repeating step 11 and diluted in the differentiation medium such that a 20 µL droplet will contain 500 cells.

- 21.

Using a 100 µL multichannel pipette with 6 sterile pipette tips attached, we dispensed 20 µL droplets into the lid of the untreated petri plate. The droplets were evenly spaced so they do not touch each other. Each 10 cm petri plate lid contained approximately 60 droplets and were about 1 cm from the edge.

- 22.

The lid was carefully inverted over the base of the petri plate containing PBS. Make a quick flip-over to prevent the drops from running into each other.

- 23.

The plates were moved gently into the cell culture incubator for 48 hours. While moving plates, we ensured the PBS solution at the base did not dislodge droplets from the lid.

- 24.

Exactly after 48 hours, the plates were returned to the tissue culture hood. We pre-warmed the differentiation media by supplementing 20% FBS differentiation medium with XAV939.

- 25.

Using a 1000 µL pipette, the embryoid bodies were collected into a sterile 15 mL conical tube. These embryoid bodies are very delicate and were gently pipetted to maintain their structural integrity. The embryoid bodies were allowed to settle to the bottom of the conical tube by gravity.

- 26.

The supernatant was gently aspirated and discarded without disturbing the settled embryoid bodies.

- 27.

2 mL of pre-warmed 20% FBS differentiation medium supplemented with XAV939 was dispensed into 6 cm sterile petri plates and 1 mL of medium gently added to the embryoid bodies.

- 28.

Using a 1000 µL sterile pipette, embryoid bodies were gently resuspended and transferred into the 6 cm plate containing pre-warmed media.

- 29.

The plate was gently moved into the cell culture incubator for 48 hours, and the plate moved in short left, right, up, and down motions to evenly disperse the embryoid bodies across the surface of the plate.

- 30.

After 48 hrs, the well of the 6-well tissue culture plate was flooded with 2 mL of 0.1% gelatin and placed in the cell culture incubator for about 30 minutes. Following incubation, the excess gelatin solution was aspirated and discarded.

- 31.

Using a 1000 µL pipette, embryoid bodies were transferred into a 15 mL conical tube and allowed to settle by gravity. After settling, the supernatant was aspirated and discarded without dislodging the embryoid bodies.

- 32.

The embryoid bodies were gently resuspended in 2 mL 20% FBS differentiation medium and transferred into the gelatin-coated well in the 6-well tissue culture plate.

- 33.

The plates were returned to the cell culture incubator at 37 oC for 24 hours. *The embryoid bodies will attach and undergo morphological changes*.

- 34.

After 24 hrs, the 20% FBS differentiation medium was replaced with 3 mL Low FBS differentiation media. This will reduce the growth of other cell types.

- 35.

The media was changed with fresh pre-warmed Low FBS differentiation media every 24 hours and cells monitored for contractile activity.

- 36.

Typically, contractile activity is observed after 8 days post-differentiation.

2 – 5 x 106 cells were used for RNA purification from ESCs before differentiation. For samples from days 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 post-differentiation, prepare four 10 cm petri plates each for RNA purification. The procedure described here uses TRizol for RNA purification on a clean lab bench. RNA is very unstable and prone to degradation by RNases that are ubiquitously present in the lab environment. Therefore, we used autoclaved pipette tips, a clean bench, and RNaseAway to clean pipettes before RNA purification. The microcentrifuge tubes were handled with clean gloves, and touching the inner lid of the tubes was avoided as this could introduce RNases to samples.

For undifferentiated cells, 5 x 106 cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 3 minutes, supernatant discarded, cells washed with 1x PBS, and 1 mL of TRIzol® reagent add. For embryoid bodies on day 2 and day 4, pellet embryoid bodies by gravity, wash with 1x PBS, and add 1 mL of TRIzol® reagent. For differentiation days 6, 8, and 12, detach cells using a cell lifter and pellet by centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 3 minutes or by washing attached cells gently with PBS and directly adding 1 mL of TRIzol® reagent.

Using a 1 mL pipette, the TRIzol® reagent was mixed with the sample until there were no visible cells by pipetting up and down about 10 times. The samples were incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature.

200 µL of chloroform was added to the tubes and shaken vigorously by hand for 15 seconds. This was incubated for 3 minutes at room temperature.

After incubation, the phases begun to separate. The tube was gently placed in a centrifuge without mixing and spun at 12000 x g for 15 minutes at 4 oC.

At this point, the phases were well separated, and care was taken when removing tubes from the centrifuge to prevent mixing. The top aqueous phase (~500 µL) was collected into another clean 1.5 mL tube.

500 µL of 100% isopropanol was added to the aqueous phase, mixed a few times by inverting the tubes up and down, and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. The tubes were centrifuged at 12000 x g for 10 minutes at 4 oC.

The supernatant was discarded from the tube and the RNA pellet washed with 1 mL of 75% ethanol. The tube was centrifuged at 7500 x g for 5 minutes at 4 oC, the wash discarded, and the RNA pellet air dried for 10 minutes.

The RNA pellet was resuspended in 85 µL RNAse-free water, 4 µL DNAse, 1 µL RNase inhibitor, and 10 µL of 10x DNase Buffer added. The resuspended RNA was mixed properly and incubated at 37 oC for 2 hours.

Following DNase treatment, the RNA was cleaned up by either (A) Repeating steps (1 – 7) or following the instructor manual of the PureLink RNA Mini Kit.

After final purification and resuspension of RNA in ~ 100 µL of RNase-free water, 0.5 µL of RNase inhibitor was added.

The integrity of RNA was assessed by running 1 ug of RNA on an agarose gel. The RNA was quantified before proceeding to the next steps.

cDNA was synthesized using 1 ug of RNA and random hexamers by following the instructor’s manual of the RT-cDNA synthesis kit.

For quantitative PCR, 1:50 cDNA dilution was made. 6 µL of the cDNA dilution, 1.5 µL of primer mix (forward and reverse), and 7.5 µL of Evagreen® mix were used per well. The qPCR reaction was performed in the Quantitative-PCR detection system following the Evagreen® instructor’s manual.

Day 12 differentiated cardiomyocytes were washed with 1 mL PBS in the 6-well tissue culture plates

In the dark, 1 mL of freshly prepared 4% (vol/vol) formaldehyde was added and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature to fix cells.

Following incubation, we washed the cells 3 times with 1x PBS, aspirating PBS between each wash.

We prepared the primary antibody solution by adding 1 µL of cTnT antibody to 1 mL of blocking solution, mixed properly, and added to the well containing fixed cardiomyocytes.

The cells were incubated with cTnT antibody overnight at 4 oC or room temperature for 2 hrs.

Following incubation, the cTnT antibody solution was discarded and the cells washed with 1x PBS three times, aspirating PBS between each wash.

In the dark, the secondary antibody solution was prepared by diluting 1 µL of mouse IgG Alexa Fluor® 488 in 1 mL blocking solution. This solution was added to the well containing fixed cells and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

The secondary antibody solution was aspirated in the dark and repeat step 6 repeated.

Following washes, 1 mL of 0.5 µg/mL DAPI solution in PBS was added to the well in the dark.

Immunofluorescence images were taken using the EVOS®FL fluorescence microscope.

(Footnote: The EVOS®FL microscope can take images of plates directly. Alternatively, cardiomyocytes can be grown on coverslips in the wells and transferred onto a microscope slide after following steps 1-9 described above. The cover slip should be mounted over mounting media on a microscope slide).

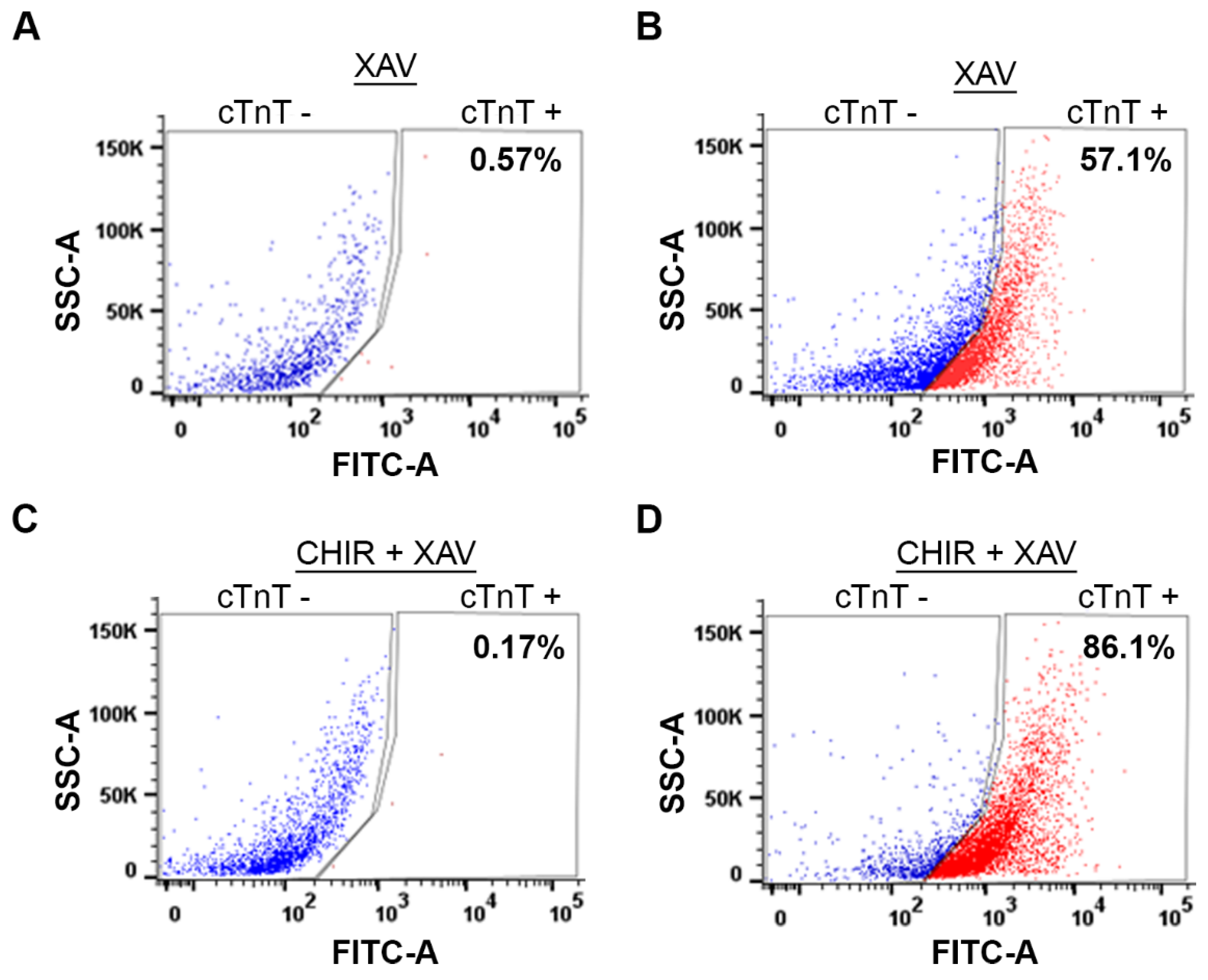

Preparation of cells for FACS: We performed quantitative analysis to determine the purity and yield of cardiomyocytes generated using the combination of CHIR99021 and XAV939 by following previously published methods [

26]. Briefly, cardiomyocytes on day 12 post-differentiation were washed with 1x PBS to remove the medium and dead cells. The cardiomyocytes were then incubated with 1 mL 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA for 5 minutes at 37

oC to singularize cells. The trypsin reaction was quenched with differentiation medium containing FBS and cells further singularized by continuous pipetting. The cells were counted and pelleted at 200 x g for 5 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1% formaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature. The cells were pelleted and resuspended in cold 90% methanol for 15 minutes at 4

oC. The cells were pelleted, and 0.5 million cells were resuspended in 1x PBS buffer containing 2.5% BSA to wash cells. This wash was performed 3 times to remove residual methanol. Next, the cells were resuspended in 1x PBS buffer containing 2.5% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 without antibody or with cTnT antibody at a dilution of 1:100 and incubated overnight at 4

oC. Following incubation, the cells were washed three times with 1x PBS buffer containing 2.5% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100. Here, cells were incubated with no secondary antibody or AlexaFluor 488 secondary antibody at a 1:1000 dilution for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with 1x PBS buffer containing 2.5% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100. We then performed flow cytometry using the BD Fortessa.

FACS Analysis: We collected data for unstained, only secondary antibody staining, and both primary antibody (cTnT) and secondary antibody staining. We used cells collected from secondary antibodies only as a background for gating. This was referred to as cTnT negative cells. The cells collected outside this gate from cTnT and AlexaFluor 488 were gated as cTnT-positive cells.

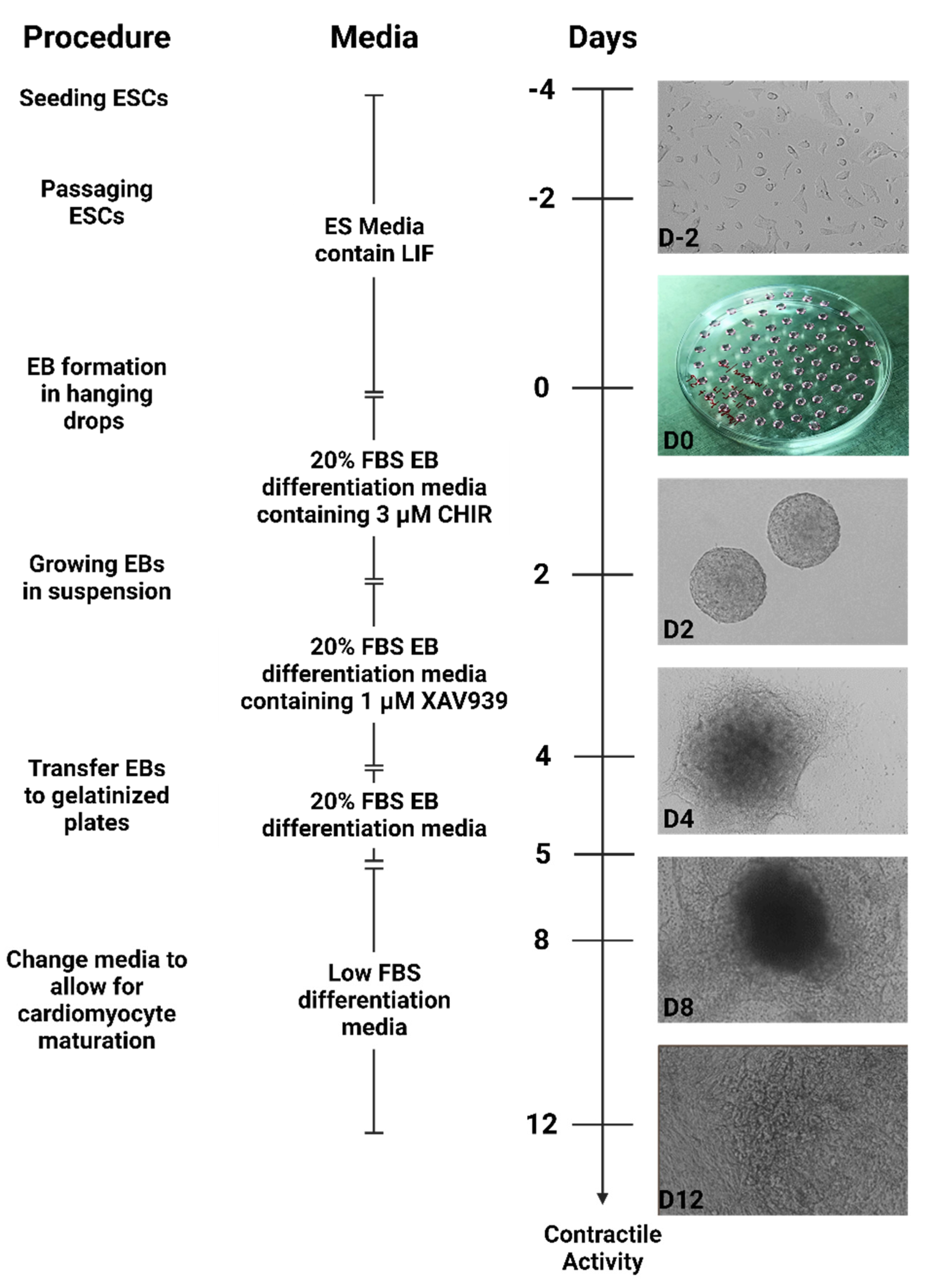

Briefly, mouse ESCs are cultured for at least two passages after thawing using medium containing the leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). To begin differentiation, the cells are cultured in 20% differentiation medium supplemented with CHIR99021 as hanging drops. Uniform rounded embryoid bodies were formed on day 2 (D2) of differentiation (

Figure 1). The embryoid bodies were transferred to petri plates in differentiation medium supplemented with XAV939. On day 4 of differentiation (D4), an increase in embryoid body size was observed, with cells beginning to attach to the surface of the petri plates (

Figure 1). After transferring embryoid bodies to gelatinized plates, significant morphology changes were observed, with cells growing out of the embryoid body core to generate a monolayer sheet of attached cells by day 8 (D8). These sheets of cells also displayed contractile activity, which continued to increase through day 12 (D12) of differentiation (

Figure 1,

Supplementary video 1).

3. Results

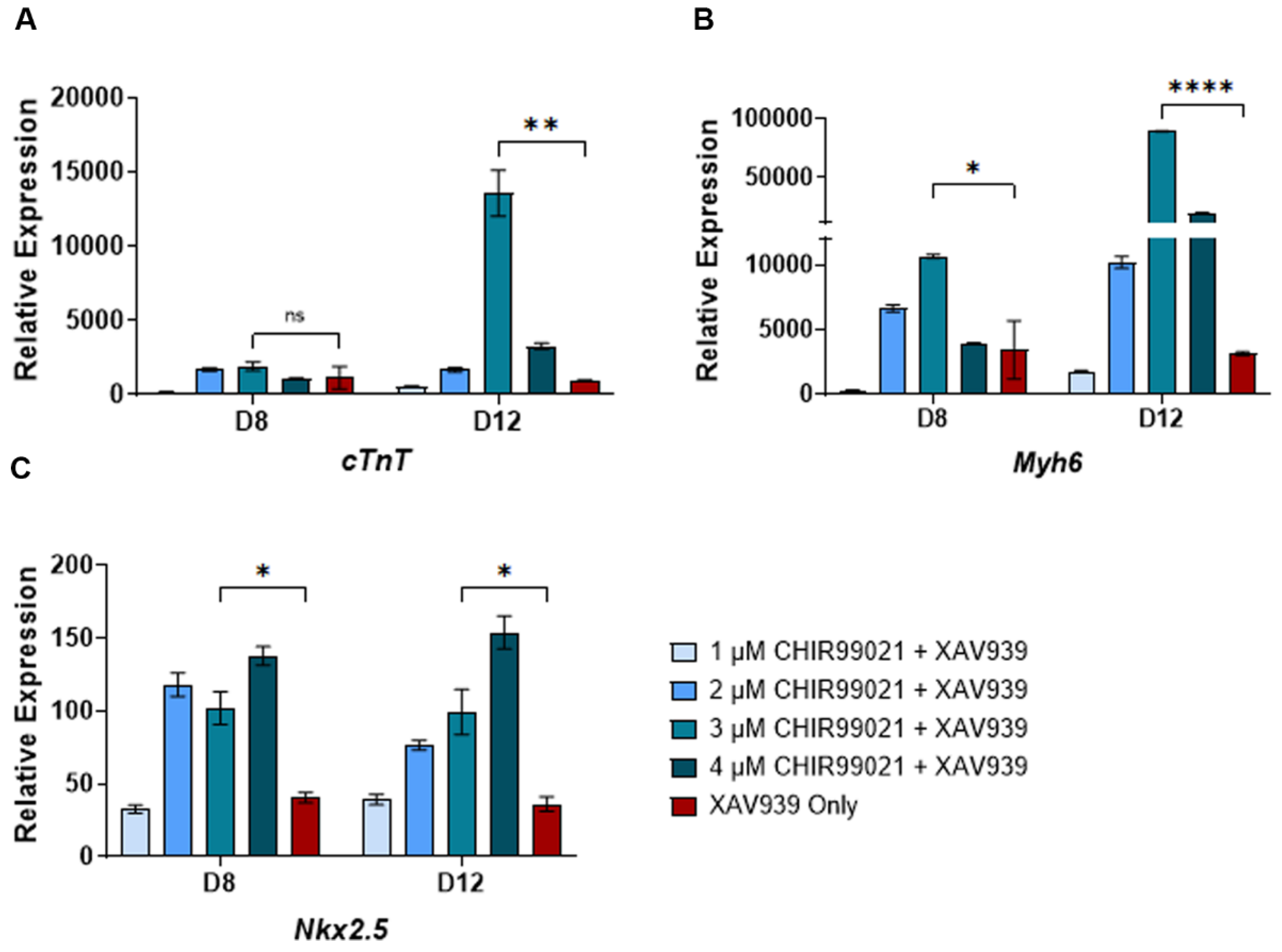

CHIR99021 has previously been used for cardiomyocyte differentiation from human IPSCs. Therefore, to identify the optimum CHIR99021 concentration sufficient to induce cardiomyocyte differentiation from mouse ESCs, we used 1, 2, 3, and 4 μM CHIR99021 for the first two days of differentiation. The treatment with CHIR99021 was immediately followed by XAV939 treatment. In addition, we also differentiated mouse ESCs into cardiomyocytes using the previously published method, which only utilized the XAV939 treatment [

30]. We then characterized the cardiomyocytes generated under these conditions by monitoring the expression of the cardiomyocyte-specific genes (

cTnT,

Myh6, and

Nkx2.

5) on days 8 and 12 post-differentiation by RT-qPCR. We observed the least induction of

cTnT,

Myh6, and

Nkx2.5 from cells differentiated with 1 µM CHIR99021. In both day 8 and day 12 post-differentiation, treatment with 4 µM CHIR99021 showed the highest

Nkx2.5 gene expression. On day 8 of cardiomyocyte differentiation, the expression of

cTnT in 2, 3, and 4 µM CHIR99021 treated cells was similar to cells only treated with XAV939 (

Figure 2A). Interestingly, the expression of

cTnT and

Myh6 was highest in 3 µM treated cells compared to the other conditions (

Figure 2A,B). More importantly, the induction of these cardiomyocyte-specific gene markers was significantly higher in the 3 μM CHIR99021 treated samples compared to the only XAV939 treated cells (

Figure 2A–C). These data suggest that 3 μM CHIR99021 treatment of ESCs for two days post-differentiation followed by treatment with XAV939 is sufficient to induce higher yields of cardiomyocytes.

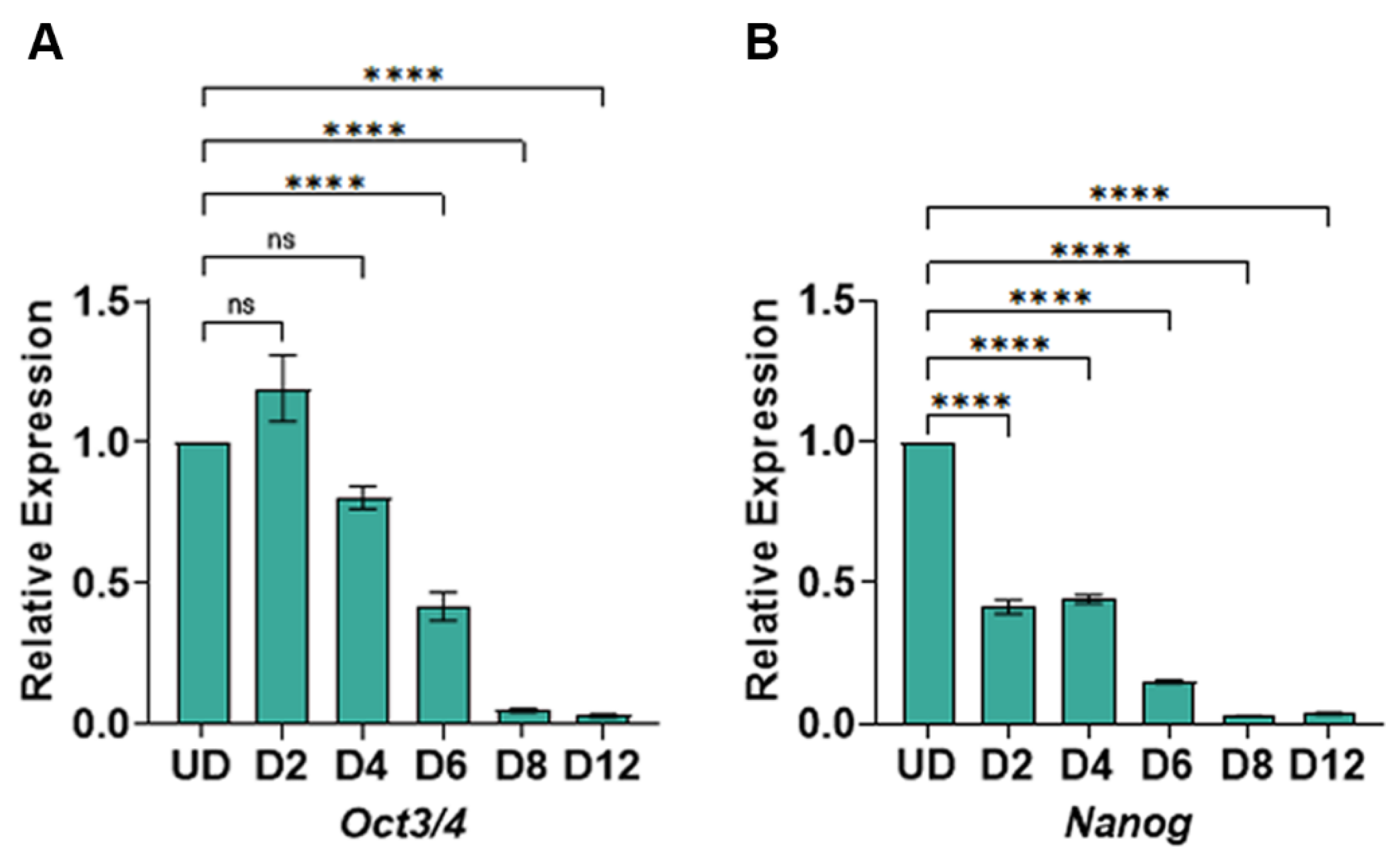

The successful differentiation of pluripotent stem cells requires the complete repression of pluripotency-specific genes post-differentiation. Therefore, we asked whether the expression of the pluripotency master regulators

Oct3/4 and

Nanog were repressed post-differentiation. We purified total RNA from undifferentiated and days 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 cells post-differentiation. Following cDNA synthesis, we performed quantitative qPCR using gene-specific primers for

Oct3/

4 and

Nanog. We observed a significant repression of

Oct3/4 expression beginning from day 6 post-differentiation. The expression of

Oct3/4 continued to decrease significantly by day 8 and day 12 post-differentiation (

Figure 3A). Additionally, the expression of

Nanog was immediately repressed by day 2 post-differentiation, further decreasing expression throughout the cardiomyocyte differentiation (

Figure 3B). Taken together, the expression profiles of the pluripotency-specific genes suggest a complete exit from the pluripotency state post-differentiation.

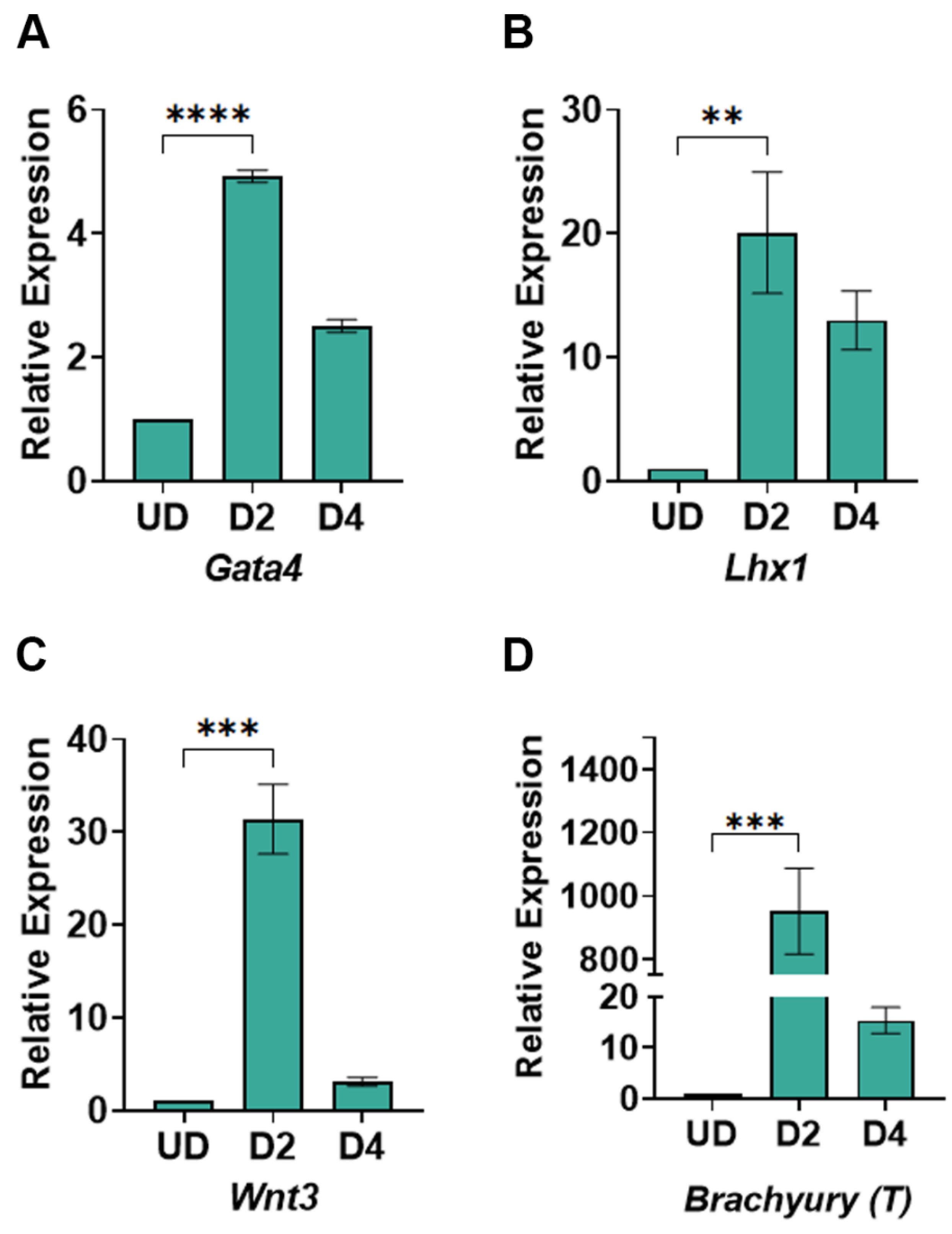

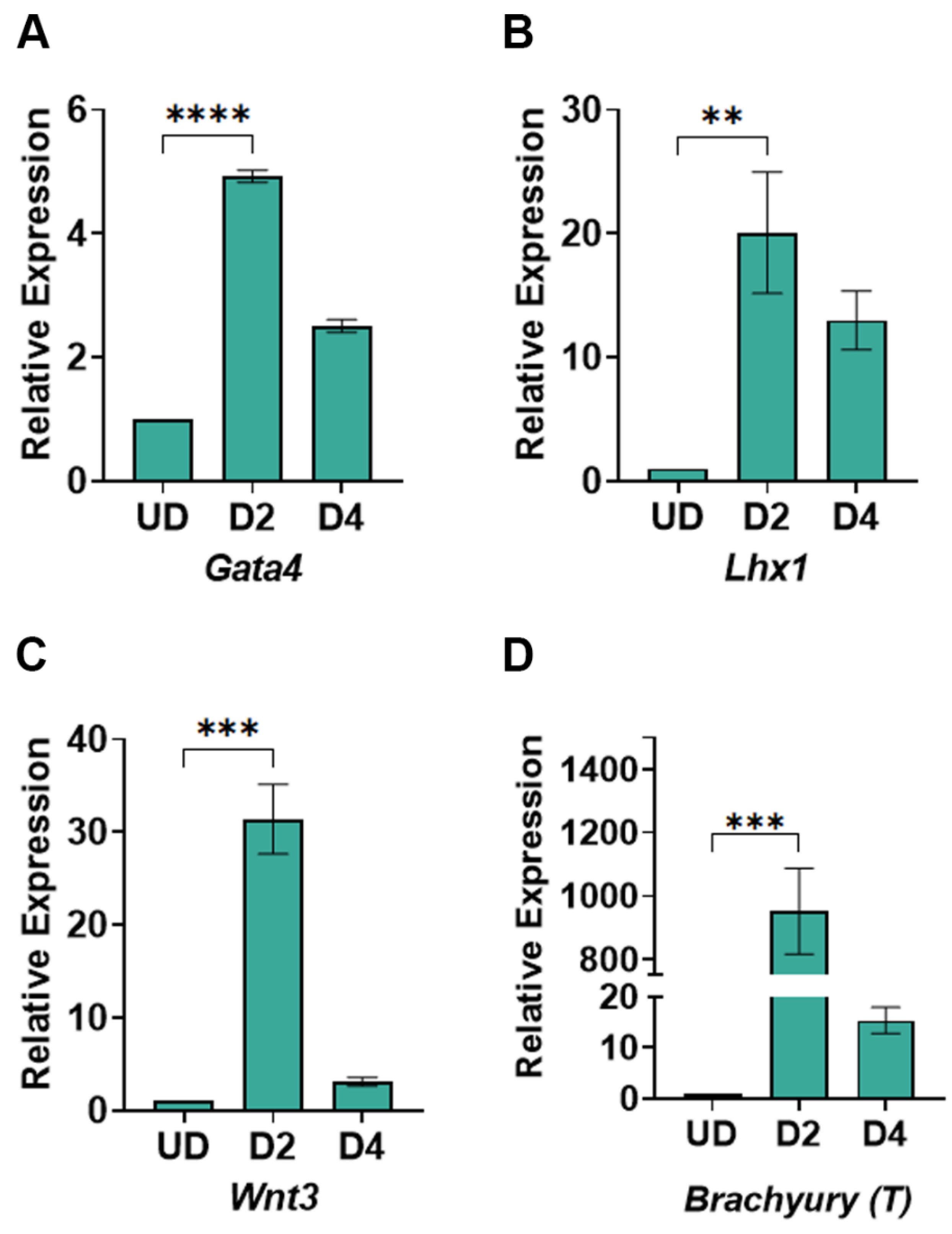

Our method relies on modulating the WNT signaling pathway to induce mesoderm and cardiac mesoderm formation. We expected to achieve increased WNT signaling upon treatment of cells with CHIR99021 and the inhibition of the WNT signaling pathway by treatment with XAV939. To determine whether we successfully induced WNT signaling and its inhibition thereof, we measured the expression of WNT signaling genes at days 2 and 4 post-differentiation compared to undifferentiated cells. The genes we chose to monitor for the WNT signaling pathway also indicate mesoderm differentiation. As expected, we saw a significant increase in the expression of

Gata4 (

Figure 4A),

Lhx1 (

Figure 4B),

Wnt3 (

Figure 4C), and

Brachyury (

Figure 4D), indicating an induction of the WNT signaling pathway by CHIR99021. Similarly, the treatment of cells with XAV939 reduced the expression of these genes by day 4 post-differentiation (

Figure 4A–D). Taken together, these data highlight the efficiency of our method in inducing WNT signaling and mesoderm genes, which is critical for cardiomyocyte differentiation.

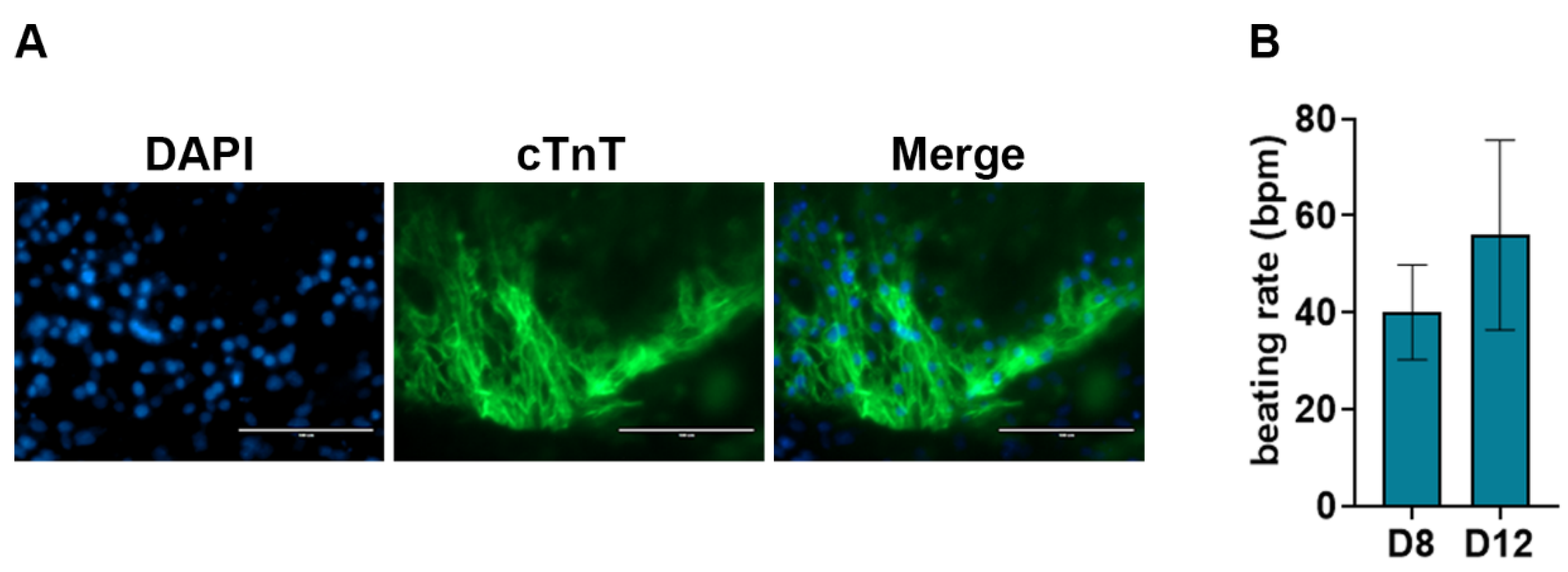

A key feature of cardiomyocytes is their unique morphology and sarcomere structures. This morphology can be visualized using immunostaining against cTnT, cTnI, MLC2a, and

α-actinin. To characterize the efficient differentiation of ESCs into cardiomyocytes using our method, we performed immunostaining against cTnT on day 12 post-differentiation. Our data showed a positive immunostaining of cTnT in day 12 cardiomyocytes (

Figure 5A). Additionally, we measured the contractile activity of the cardiomyocytes by measuring the beats per minute (bpm) using videos obtained from brightfield microscopy. We observed a mean bpm of about 40 and 60 at D8 and D12 respectively, which are similar to rates previously reported [

31].

Next, we compared the yield of cardiomyocytes generated by WNT Switch method with currently used method [

30], which utilizes only XAV939 treatment using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). Briefly, cardiomyocytes were dissociated, fixed, and stained with anti-cTNT and AlexaFluor-488 antibodies. As a negative control, we stained dissociated cardiomyocytes with the AlexaFluor-488 antibody without the anti-cTnT antibody (

Figure 6A,C). Following FACS analysis, the induction of cardiomyocytes from XAV939 treated cells yielded about 57.1 % cardiomyocytes (

Figure 6B), similar to the 58.7% yield previously published [

30]. As expected, our method for cardiomyocyte induction, generated about 86.1% yield (

Figure 6D). A 30% increase in the yield concludes demonstrates the robustness of WNT Switch method that improves our ability to perform molecular analysis biological pathways in this cell type.

4. Discussion

The heart is the first organ formed during mammalian development and is controlled by gene regulation and signal transduction pathways. In particular, the WNT signaling pathway is critical for the efficient development of cardiomyocytes [

27]. These cardiomyocytes confer function to the heart through their contractile activity and are a critical component of the heart. In fact, due to their reduced proliferative ability, cardiomyocyte deficiency underlies most heart failures [

3,

4,

5]. Here, we describe WNT Switch method as an efficient way to generate cardiomyocytes from mouse ESCs

in vitro that could be used to study the molecular mechanisms regulating cardiomyocyte development. This method leverages the regulation of WNT signaling during normal mammalian heart development. Cardiomyocyte progenitors originate from the mesoderm germ layer following gastrulation [

32]. Thus, it is imperative to induce mesoderm formation during cardiomyocyte differentiation. Strong evidence supports the role of the WNT signaling pathway in inducing mesoderm formation [

33,

34,

35]. Previous methods developed for mouse cardiomyocyte differentiation rely on the endogenous activation of WNT signaling or growth factors to induce mesoderm post-differentiation [

6,

30,

36,

37]. WNT Switch method is distinct, given that we treat cells with CHIR99021 during embryoid body formation to induce mesoderm formation. Upon treatment of ESCs from undifferentiated to day 2, we show an increased expression of mesoderm-specific genes (

Figure 4), suggesting an induction of mesoderm formation. The high expression of the WNT3 ligand (

Wnt3a) and the WNT response genes (

T,

Lhx1, Gata4) supports the specific induction of the WNT signaling pathway. The relative expression of the mesoderm-specific genes we obtained from our differentiation method is comparable to other methods that utilize expensive but unstable growth factors [

7].

A properly formed mesoderm is a hub for cardiomyocyte progenitor cells and generates progenitor cells for endothelial and hematopoietic lineages [

38,

39]. Interestingly, the WNT signaling pathway contributes to the fate of mesoderm cells into distinct lineages [

40]. The continuous activation of WNT signaling is implicated in the formation of endothelial cells and other mesodermal lineages [

41,

42,

43]. However, inhibiting the WNT signaling pathway promotes cardiomyocyte progenitor lineages post-mesoderm differentiation [

16,

17,

24,

26]. Therefore, we immediately followed the activation of mesoderm formation with the inhibition of WNT signaling using XAV939 from day 2 to day 4. We observed a decrease in gene expression of the WNT signaling genes on day 4 (

Figure 4A–D).

The benchmark for cardiomyocyte differentiation is a spontaneous and uniform contractile activity. We began observing spontaneous contractile activity from Day 8 post-differentiation, which continued to increase by day 12 of differentiation (

Figure 5B,

Supplementary video 1). The presence of contractile activity corroborated the elevated expression of the cardiac-specific gene markers (

cTnT,

Myh6, and

Nkx2.5) from day 8 post-differentiation (

Figure 2). Importantly, the elevated expression of the cardiomyocyte-specific genes is higher than previously reported methods [

7,

30]. The increased expression of the cardiac-specific gene markers and the uniform contractile activity we observed highlight the success of our method. Additionally, we show that the combined treatment with CHIR99021 and XAV939 generates about a 30% increase in the yield of cardiomyocytes generated from mouse ESCs compared to the XAV939 treatment alone (

Figure 2). Importantly, our yield for cardiomyocyte differentiation exceeded previous studies utilizing growth factors [

6,

36,

37]. We also obtained positive immunostaining of cTnT, further confirming the presence of cardiomyocytes (

Figure 5A). As expected for successful differentiation, the pluripotency-specific gene markers (

Oct3/4 and

Nanog) were remarkably reduced post-differentiation (

Figure 3A,B).

Altogether, mESCs are invaluable in modeling developmental processes and diseases and the Wnt Switch method is an easy, fast, efficient, and reproducible protocol to generate cardiomyocytes from mESCs in vitro. This method will advance studies on understanding molecular mechanisms and gene regulatory factors that control the cardiomyocyte development program. For example, molecular experiments like Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) at the different stages during cardiomyocyte differentiation often require large number of cells and the WNT Switch method can generate sizable cardiomyocytes for molecular analysis. Additionally, the generation of a homogeneous population of cardiomyocytes can help identify therapeutic targets that could unlock the proliferative ability of cardiomyocytes in vivo.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G.; methodology, I.K.M. M.L.E, H.J.T; formal analysis, I.K.M, M.L.E; writing—review and editing, I.K.M and H.G; supervision, H.G.; funding acquisition, H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the American Heart Association and Start-Up funds from the College of Agriculture, Purdue University

Data Availability Statement

All data are presented in this article, and raw files can be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Gowher Lab members for their continued support and discussions during the design of this method. We also thank Dr. Xiaoping Bao (Purdue University) and Dr. Jill Hutchcroft (Purdue University) for their insights regarding the generation of this method.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- J. Nichols and A. Smith, "Naive and primed pluripotent states," Cell Stem Cell, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 487-92, Jun 5 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Rossant, "Stem Cells and Early Lineage Development," Cell, vol. 132, no. 4, pp. 527-531, 2008/02/22/ 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Parmacek and J. A. Epstein, "Cardiomyocyte renewal," (in eng), N Engl J Med, vol. 361, no. 1, pp. 86-8, Jul 2 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. R. Porrello and E. N. Olson, "A neonatal blueprint for cardiac regeneration," (in eng), Stem Cell Res, vol. 13, no. 3 Pt B, pp. 556-70, Nov 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. V. Huikuri, A. Castellanos, and R. J. Myerburg, "Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias," (in eng), N Engl J Med, vol. 345, no. 20, pp. 1473-82, Nov 15 2001. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinopoulos, H. Ishida, R. Saba, S. Coppen, K. Suzuki, and K. Yashiro, "Cardiomyocyte differentiation from mouse embryonic stem cells using a simple and defined protocol," (in eng), Dev Dyn, vol. 245, no. 2, pp. 157-65, Feb 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Mazzotta, C. Neves, R. J. Bonner, A. S. Bernardo, K. Docherty, and S. Hoppler, "Distinctive Roles of Canonical and Noncanonical Wnt Signaling in Human Embryonic Cardiomyocyte Development," (in eng), Stem Cell Reports, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 764-776, Oct 11 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Pahnke, G. Conant, L. D. Huyer, Y. Zhao, N. Feric, and M. Radisic, "The role of Wnt regulation in heart development, cardiac repair and disease: A tissue engineering perspective," (in eng), Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 473, no. 3, pp. 698-703, May 6 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tian, E. D. Cohen, and E. E. Morrisey, "The importance of Wnt signaling in cardiovascular development," (in eng), Pediatr Cardiol, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 342-8, Apr 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Buikema, P.-P. M. Zwetsloot, P. A. Doevendans, I. J. Domian, and J. P. G. Sluijter, "Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling during Cardiac Development and Repair," Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 98-110. [CrossRef]

- W.-b. Fu, W. E. Wang, and C.-y. Zeng, "Wnt signaling pathways in myocardial infarction and the therapeutic effects of Wnt pathway inhibitors," Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 9-12, 2019/01/01 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Brade, J. Männer, and M. Kühl, "The role of Wnt signalling in cardiac development and tissue remodelling in the mature heart," Cardiovascular Research, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 198-209, 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Merrill, "Wnt pathway regulation of embryonic stem cell self-renewal," (in eng), Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, vol. 4, no. 9, p. a007971, Sep 1 2012. [CrossRef]

- U. Kreuser, J. Buchert, A. Haase, W. Richter, and S. Diederichs, "Initial WNT/β-Catenin Activation Enhanced Mesoderm Commitment, Extracellular Matrix Expression, Cell Aggregation and Cartilage Tissue Yield From Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells," (in eng), Front Cell Dev Biol, vol. 8, p. 581331, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhao, Y. Tang, Y. Zhou, and J. Zhang, "Deciphering Role of Wnt Signalling in Cardiac Mesoderm and Cardiomyocyte Differentiation from Human iPSCs: Four-dimensional control of Wnt pathway for hiPSC-CMs differentiation," Scientific Reports, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 19389, 2019/12/18 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Ueno et al., "Biphasic role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiac specification in zebrafish and embryonic stem cells," (in eng), Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 104, no. 23, pp. 9685-90, Jun 5 2007. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Naito et al., "Developmental stage-specific biphasic roles of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiomyogenesis and hematopoiesis," (in eng), Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 103, no. 52, pp. 19812-7, Dec 26 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. Kwon, K. R. Cordes, and D. Srivastava, "Wnt/beta-catenin signaling acts at multiple developmental stages to promote mammalian cardiogenesis," (in eng), Cell Cycle, vol. 7, no. 24, pp. 3815-8, Dec 15 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. Gessert and M. Kühl, "The multiple phases and faces of wnt signaling during cardiac differentiation and development," (in eng), Circ Res, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 186-99, Jul 23 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Zheng, J. Liu, Y. Wu, T. L. Huang, and G. Wang, "Small-molecule inhibitors of Wnt signaling pathway: towards novel anticancer therapeutics," (in eng), Future Med Chem, vol. 7, no. 18, pp. 2485-505, 2015. [CrossRef]

- 21. F. H. Tran and J. J. Zheng, "Modulating the wnt signaling pathway with small molecules," (in eng), Protein Sci, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 650-661, Apr 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang et al., "A Highly Selective GSK-3β Inhibitor CHIR99021 Promotes Osteogenesis by Activating Canonical and Autophagy-Mediated Wnt Signaling," (in eng), Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), vol. 13, p. 926622, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Chen et al., "Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors induce the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway to suppress growth and self-renewal in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma," (in eng), Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 111, no. 14, pp. 5349-54, Apr 8 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, X. Zheng, Y. Han, Y. Lv, F. Lan, and J. Zhao, "XAV939 inhibits the proliferation and migration of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells through the WNT pathway," (in eng), Oncol Lett, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 8973-8982, Jun 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Halevy and A. Urbach, "Comparing ESC and iPSC-Based Models for Human Genetic Disorders," (in eng), J Clin Med, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 1146-62, Oct 24 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Lian et al., "Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions," (in eng), Nat Protoc, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 162-75, Jan 2013. [CrossRef]

- X. Lian et al., "Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signaling," (in eng), Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 109, no. 27, pp. E1848-57, Jul 3 2012. [CrossRef]

- X. Lian et al., "Chemically defined, albumin-free human cardiomyocyte generation," in Nat Methods, vol. 12, no. 7). United States, 2015, pp. 595-6.

- P. W. Burridge et al., "Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes," (in eng), Nat Methods, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 855-60, Aug 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, J. Hao, and C. C. Hong, "Cardiac induction of embryonic stem cells by a small molecule inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling," (in eng), ACS Chem Biol, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 192-7, Feb 18 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Heo et al., "Mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase 1 regulates the early differentiation of cardiomyocytes from mouse embryonic stem cells," Exp Mol Med, vol. 48, no. 8, p. e254, Aug 19 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Van Vliet, S. M. Wu, S. Zaffran, and M. Pucéat, "Early cardiac development: a view from stem cells to embryos," (in eng), Cardiovasc Res, vol. 96, no. 3, pp. 352-62, Dec 1 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Tran et al., "Wnt3a-induced mesoderm formation and cardiomyogenesis in human embryonic stem cells," (in eng), Stem Cells, vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 1869-78, Aug 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Kemp, E. Willems, D. Wawrzak, M. Hendrickx, T. Agbor Agbor, and L. Leyns, "Expression of Frizzled5, Frizzled7, and Frizzled10 during early mouse development and interactions with canonical Wnt signaling," (in eng), Dev Dyn, vol. 236, no. 7, pp. 2011-9, Jul 2007. [CrossRef]

- A. Schohl and F. Fagotto, "A role for maternal beta-catenin in early mesoderm induction in Xenopus," (in eng), Embo j, vol. 22, no. 13, pp. 3303-13, Jul 1 2003. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Engels et al., "Insulin-like growth factor promotes cardiac lineage induction in vitro by selective expansion of early mesoderm," (in eng), Stem Cells, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 1493-502, Jun 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Kattman et al., "Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines," (in eng), Cell Stem Cell, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 228-40, Feb 4 2011. [CrossRef]

- E. Ferretti and A. K. Hadjantonakis, "Mesoderm specification and diversification: from single cells to emergent tissues," (in eng), Curr Opin Cell Biol, vol. 61, pp. 110-116, Dec 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Evseenko et al., "Mapping the first stages of mesoderm commitment during differentiation of human embryonic stem cells," (in eng), Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 107, no. 31, pp. 13742-7, Aug 3 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Davis and N. I. Zur Nieden, "Mesodermal fate decisions of a stem cell: the Wnt switch," (in eng), Cell Mol Life Sci, vol. 65, no. 17, pp. 2658-74, Sep 2008. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Woll et al., "Wnt signaling promotes hematoendothelial cell development from human embryonic stem cells," (in eng), Blood, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 122-31, Jan 1 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Olsen et al., "The Role of Wnt Signalling in Angiogenesis," (in eng), Clin Biochem Rev, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 131-142, Nov 2017.

- N. Manukjan, Z. Ahmed, D. Fulton, W. M. Blankesteijn, and S. Foulquier, "A Systematic Review of WNT Signaling in Endothelial Cell Oligodendrocyte Interactions: Potential Relevance to Cerebral Small Vessel Disease," (in eng), Cells, vol. 9, no. 6, Jun 25 2020. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic for WNT Switch method for differentiating mouse ESCs into cardiomyocytes: The schematic summarizes the differentiation method for ESCs into cardiomyocytes. D2 to D12 are the days of differentiation and the morphology of cells on those specific days. Representative images of the differentiation state are shown on the right part of the timeline.

Figure 1.

Schematic for WNT Switch method for differentiating mouse ESCs into cardiomyocytes: The schematic summarizes the differentiation method for ESCs into cardiomyocytes. D2 to D12 are the days of differentiation and the morphology of cells on those specific days. Representative images of the differentiation state are shown on the right part of the timeline.

Figure 2.

RT-qPCR for cardiac-specific genes in undifferentiated and differentiated cells: (A) Expression of cTnT gene; (B) Expression of the Myh6 gene; (C) Expression of Nkx2.5. The data shows the gene expression for cardiac-specific genes relative to Gapdh expression. The relative expression was normalized to gene expression in the undifferentiated cells, which has been set to 1. The mathematical equation used was 2-ΔΔCq. where ΔΔcq represents (Gapdh – Gene target) and (Undifferentiated – day of differentiation). UD: Undifferentiated, D2-D12: days post-differentiation, Cq: quantification cycle obtained from the qPCR machine. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ns: non-significant change, ****: p-value < 0.0001, ***: p-value < 0.001, **, p-value < 0.01. Statistical significance was obtained by performing a student t-test comparing gene expression in 3 µM CHIR99021 treated cells to XAV939-only cells.

Figure 2.

RT-qPCR for cardiac-specific genes in undifferentiated and differentiated cells: (A) Expression of cTnT gene; (B) Expression of the Myh6 gene; (C) Expression of Nkx2.5. The data shows the gene expression for cardiac-specific genes relative to Gapdh expression. The relative expression was normalized to gene expression in the undifferentiated cells, which has been set to 1. The mathematical equation used was 2-ΔΔCq. where ΔΔcq represents (Gapdh – Gene target) and (Undifferentiated – day of differentiation). UD: Undifferentiated, D2-D12: days post-differentiation, Cq: quantification cycle obtained from the qPCR machine. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ns: non-significant change, ****: p-value < 0.0001, ***: p-value < 0.001, **, p-value < 0.01. Statistical significance was obtained by performing a student t-test comparing gene expression in 3 µM CHIR99021 treated cells to XAV939-only cells.

Figure 3.

RT-qPCR for pluripotency genes in undifferentiated and differentiated cells: (a) Expression of Oct3/4 gene; (b) Expression of the Nanog gene. The data shows the gene expression for Oct3/4 and Nanog relative to Gapdh expression. The relative expression was then normalized to gene expression in the undifferentiated cells, set to 1. The mathematical equation used was 2-ΔΔCq where ΔΔcq represents (Gapdh – Gene target) and (Undifferentiated – day of differentiation). UD: Undifferentiated, D2-D12: days post-differentiation, Cq: quantification cycle obtained from the qPCR machine. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ns: non-significant change, ****: p-value < 0.0001. The statistical significance was obtained by performing a unpaired t-test in GraphPad prism comparing gene expression in days post-differentiation to the undifferentiated cells.

Figure 3.

RT-qPCR for pluripotency genes in undifferentiated and differentiated cells: (a) Expression of Oct3/4 gene; (b) Expression of the Nanog gene. The data shows the gene expression for Oct3/4 and Nanog relative to Gapdh expression. The relative expression was then normalized to gene expression in the undifferentiated cells, set to 1. The mathematical equation used was 2-ΔΔCq where ΔΔcq represents (Gapdh – Gene target) and (Undifferentiated – day of differentiation). UD: Undifferentiated, D2-D12: days post-differentiation, Cq: quantification cycle obtained from the qPCR machine. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ns: non-significant change, ****: p-value < 0.0001. The statistical significance was obtained by performing a unpaired t-test in GraphPad prism comparing gene expression in days post-differentiation to the undifferentiated cells.

Figure 4.

RT-qPCR for mesoderm-specific genes in undifferentiated and differentiated cells: (A) Expression of the Gata4 gene; (B) Expression of the Lhx1 gene (C) Expression of Wnt3, (D) Expression of Brachyury (T). The data shows the gene expression for mesoderm-specific genes relative to Gapdh expression. The relative expression was normalized to gene expression in the undifferentiated cells, which has been set to 1. The mathematical equation used was 2-ΔΔCq. where ΔΔcq represents (Gapdh – Gene target) and (Undifferentiated – day of differentiation). UD: Undifferentiated, D2-D4: days post-differentiation, Cq: quantification cycle obtained from the qPCR machine. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ns: non-significant change, ****: p-value < 0.0001, ***: p-value < 0.001, **, p-value < 0.01. Statistical significance was obtained by performing a unpaired t-test in GraphPad prism comparing gene expression in day2 post-differentiation to the undifferentiated cells.

Figure 4.

RT-qPCR for mesoderm-specific genes in undifferentiated and differentiated cells: (A) Expression of the Gata4 gene; (B) Expression of the Lhx1 gene (C) Expression of Wnt3, (D) Expression of Brachyury (T). The data shows the gene expression for mesoderm-specific genes relative to Gapdh expression. The relative expression was normalized to gene expression in the undifferentiated cells, which has been set to 1. The mathematical equation used was 2-ΔΔCq. where ΔΔcq represents (Gapdh – Gene target) and (Undifferentiated – day of differentiation). UD: Undifferentiated, D2-D4: days post-differentiation, Cq: quantification cycle obtained from the qPCR machine. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ns: non-significant change, ****: p-value < 0.0001, ***: p-value < 0.001, **, p-value < 0.01. Statistical significance was obtained by performing a unpaired t-test in GraphPad prism comparing gene expression in day2 post-differentiation to the undifferentiated cells.

Figure 5.

Characterization of cardiomyocytes. (A)Immunostaining of day 12 cardiomyocytes showing a positive immuno-stain against anti-cTnT antibody. DAPI was used for nucleus staining. The scale bar represents 100 μM. (B) Average beating rates of cardiomyocytes at days 8 and 12 post-differentiation. Bpm: beats per minute.

Figure 5.

Characterization of cardiomyocytes. (A)Immunostaining of day 12 cardiomyocytes showing a positive immuno-stain against anti-cTnT antibody. DAPI was used for nucleus staining. The scale bar represents 100 μM. (B) Average beating rates of cardiomyocytes at days 8 and 12 post-differentiation. Bpm: beats per minute.

Figure 6.

Induction of cardiomyocytes by WNT Switch method yields increased cardiomyocytes: (A, B) Representative FACS analysis of cardiomyocytes generated from only XAV939 treatment in (A) absence of cTnT antibody and (B) with cTnT antibody. Representative FACS analysis of cardiomyocytes generated from 3 µM CHIR99021 and XAV939 treated cells in (C) the absence of cTnT antibody and (D) in the presence of cTnT antibody. XAV: XAV939, CHIR: CHIR99021.

Figure 6.

Induction of cardiomyocytes by WNT Switch method yields increased cardiomyocytes: (A, B) Representative FACS analysis of cardiomyocytes generated from only XAV939 treatment in (A) absence of cTnT antibody and (B) with cTnT antibody. Representative FACS analysis of cardiomyocytes generated from 3 µM CHIR99021 and XAV939 treated cells in (C) the absence of cTnT antibody and (D) in the presence of cTnT antibody. XAV: XAV939, CHIR: CHIR99021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).