1. Introduction

Kidney cancer has long gone unnoticed [

1], despite being one of the top ten most fatal cancers [

1] and the seventh most prevalent form of neoplasm in the developed world [

2]. More than 90% of kidney cancer cases are renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [

3], which refers to cancer that begins in the renal epithelium [

4]. Despite advancements in healthcare and management, renal cell carcinoma is a cunning neoplasm that accounts for about 2% of cancer diagnoses and fatalities worldwide [

3] and is also the most dangerous renal malignancy [

5]. The cortex of the kidney—which is made up of the glomerulus, tubular apparatus, and collecting duct—is where the majority of RCCs develop [

6]. Modifiable risk factors such as smoking [

7], obesity [

7], uncontrolled hypertension [

8], poor diet [

9], alcohol consumption, and occupational exposure [

10] are top candidates for prevention efforts in the fight against this aggressive malignancy [

11].

There are at minimum ten molecular and histological subtypes of this disease, of which ccRCC has been shown to be the most widespread and liable for a majority of cancer-related deaths [

4]. Clear cell RCC, a renal stem cell tumour typically found in the proximal nephron and tubular epithelium [

4] and also known as conventional RCC [

12], comprises up to 80% of RCC diagnoses [

13] and is more likely to haematogenously spread to the lungs, liver, and bones [

14]. Most ccRCC tumours have the same primary driving characteristic—a loss of Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumour suppressor gene function—which is normally present throughout the tumour [

15]. Clear cell RCC can be hereditary (4%) or random (>96%) [

16]. Most familial ccRCCs are caused by a hereditary VHL mutation [

11] and, as a result of the abundance of cytoplasmic lipids in malignant cells, exhibit the typical physical appearance of a well-circumscribed golden-yellow mass [

17]. Microscopically, the tumour exhibits a complex vascular network [

18] with tiny sinusoid-like capillaries dividing nests of malignant cells, in addition to the typical clear cell morphology indicated by cytoplasmic lipid and glycogen build-up [

19].

Since approximately a century ago, the grading of RCC has been acknowledged as a prognostic marker [

20]. The tumour grade identifies whether cancer cells are regular or aberrant under a microscope. The more aberrant the cells seem and the higher the grade, the quicker the tumour is likely to spread and expand. Many different grading schemes have been proposed, initially focused on a collection of cytological characteristics and more recently on nuclear morphology. Nuclear size (area, major axis, and perimeter), nuclear shape (shape factor and nuclear compactness), and nucleolar prominence characteristics are the main emphasis in the Fuhrman grading of renal cell carcinomas. Even though Fuhrman grading has been widely used in clinical investigations, its predictive value and reliability are up for discussion [

21]. Fuhrman et al. [

22] showed, in 1982, that tumours of grades 1, 2, 3, and 4 presented considerably differing metastatic rates. When grade 2 and 3 tumours were pooled into a single cohort, they likewise demonstrated a strong correlation between tumour grade and survival [

22]. The International Society of Urologic Pathologists (ISUP) suggested a revised grading system for RCC in 2012, in order to address the shortcomings of the Fuhrman grading scheme [

23]. This system is primarily based on the assessment of nucleoli: grade 1 tumours have inconspicuous and basophilic nucleoli at 400× magnification; grade 2 tumours have eosinophilic nucleoli at 400× magnification; grade 3 tumours have visible nucleoli at 100× magnification; and grade 4 tumours have extreme pleomorphism or rhabdoid and/or sarcomatoid morphology [

24]. This grading system has been approved for papillary and ccRCC tumours [

23]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the ISUP grading system at a consensus conference in Zurich; as a result, the WHO/ISUP grading system is currently applied internationally [

24]. The abnormality of tumour cells relative to normal cells is described by the tumour grade. It also characterises the aberrant appearance of tissues when viewed under a microscope. The grade provides some insight into how cancer may act. A tumour classified as low-grade is more likely to grow more slowly and spread less frequently than one with a high grade. Thus, grades 1 and 2 are ranked as low-grade ccRCC, while grades 3 and 4 denote high-grade ccRCC. Grading ultimately facilitates the optimal management and treatment of tumours, according to their prognostic behaviour concerning their respective grades. For instance, in elderly or very sick patients who have small renal tumours (<4 cm) and high mortality rate, cryoablation, active surveillance, or radiofrequency ablation may be considered to manage their conditions [

25]. It is crucial to note that confident radiological diagnosis of low-grade tumours in active surveillance can significantly impact clinical decisions, hence eliminating the risk of over-treatment [

26]. As ccRCC is the most prevalent subtype (8 in 10 RCCs) with the highest potential for metastasis, it requires careful characterisation [

27]. High-grade cancers have a poorer prognosis, are more aggressive, have high risk of post-operative recurrence, and may metastasise [

26]. Therefore, it is very important to differentiate between different grades of ccRCC, as high-grade ccRCC requires immediate and exact management. Precision medicine together with personalised treatment has advanced with the advent of cutting-edge technology; hence, clinicians are interested in determining the grade of ccRCC before surgery or treatment, enabling them to better advise regarding therapy and even predict cancer-free survival if surgery has been conducted. The diagnosis of ccRCC grade is commonly carried out based on pre- and post-operative methods. One such pre-operative method is biopsy. However, the accuracy of a biopsy can be influenced by several factors, including the size and location of the tumour, the experience of the pathologist performing the biopsy, and the quality of the biopsy sample [

28]. Due to sampling errors, a biopsy may not always provide an accurate representation of the overall tumour grade [

29]. Inter-observer variability can also lead to inconsistencies in the grading process. This can be especially problematic for tumours that are borderline between two grades [

30]. In some cases, a biopsy may not provide a definitive diagnosis as it only considers the cross-sectional area of the tumour and, compounded with the fact that ccRCC presents high spatial and temporal heterogeneity [

31], it may not be representative of the entire tumour [

32]. A biopsy also has a small chance of haemorrhage (3.5%) and a rare risk of track seeding (1:10,000) [

33,

34]. Due to the limitations highlighted for biopsies [

35], radical or partial nephrectomy treatment specimens are usually used as definitive post-operative diagnostic tools for tumour grade. With partial or radical nephrectomy being the definitive therapeutic approach, a small but significant number of patients are subjected to unnecessary surgery, even though their management may not require surgical resection. Nephrectomy also increases the possibility of contracting chronic renal diseases that may result in cardiovascular ailments [

36]. Therefore, precise grading of ccRCC through non-invasive methods is imperative, in order to improve the effectiveness and targeted management of tumours. The assumption in most research and clinical practice is that solid renal masses are homogenous in nature or, if heterogeneous, they have the same distribution throughout the tumour volume [

37]. Recent studies [

38] have highlighted that, in some histopathologic classifications, different tumour sub-regions may have different rates of aggressiveness; hence, heterogeneity plays a significant role in tumour progression. Ignoring such intra-tumoural differences may lead to inaccurate diagnosis, treatment, and prognoses [

39]. The biological makeup of tumours is complex and, therefore, leads to spatial differences within their structures. These variations may be due to the expression of genes or the microscopic structure [

40]. Such differences can be caused by several factors, including hypoxia (i.e., the loss of oxygen in the cells) and necrosis (i.e., the death of cells). This is mostly synonymous with the tumour core. Likewise, high cell growth and tumour-infiltrating cells are factors associated with the periphery [

41]. Medical imaging analysis has been shown to be capable of detecting and quantifying the level of heterogeneity in tumours [

42,

43,

44]. This ability enables tumours to be categorised into different sub-regions depending on the level of heterogeneity. In relation to tumour grading, intra-tumoural heterogeneity may prove useful in determining the sub-region of the tumour containing the most prominent features that enable successful grading of the tumour. Radiomics, which is the extraction of high-throughput features from medical images, is a modern technique that has been used in medicine to extract features that would not be otherwise visible to the naked eye alone [

45]. It was first proposed by Lambin et al. [

46] in 2012 to extract features, taking into consideration the differences in solid masses. Radiomics eliminates the subjectivity in the extraction of tumour features from medical images, functioning as an objective virtual biopsy [

47]. A significant number of studies have applied radiomics approaches for the classification of tumour subtypes, grading, and even the staging of tumours [

48,

49].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a wide area whose aim is to build machines which simulate human cognitive abilities. It has enabled a shift from human systems to machine systems trained by computers using features obtained from the input data. In recent years, with the advent of AI, there has been tremendous progress in the field of medical imaging. Machine learning which is a branch of AI has been used to extract high dimension features from medical images and have shown significant ability to perform image segmentation, recognition, reconstruction and classification. They have also made it easy to quantify and standardised medical image features thereby acting as an intermediary between clinics and pathology. AI has been proven to be effective in reducing misdiagnosis and improving accuracy of renal diseases. ML is expected by numerous researchers to bring drastic changes in the field of individualised diagnosis and patient treatment and is currently used to predict the nuclear grade, classification and prognosis of RCC using radiomic data [

50,

51,

52,

53]. AI has also enabled the analysis of tumour sub-regions in a variety of clinical tasks, using several imaging modalities such as CT and MRI [

54]. However, these analyses have been limited to only a few types of tumours, particularly brain tumours [

55], head and neck tumours [

56], and breast cancers [

57]. To date, no study has attempted to analyse the effect of intra-tumoural heterogeneity on the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of renal masses and specifically ccRCCs. This rationale formed the basis of the present study, focusing on the effect of intra-tumoural heterogeneity on the grading of ccRCC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to comprehensively focus on tumour sub-regions in renal tumours for the prediction of tumour grade.

In this research, the hypothesis that radiomics combined with ML can significantly differentiate between high- and low-grade ccRCC for individual patients is tested. This study sought solutions to two major problems that previous research has not been able to address:

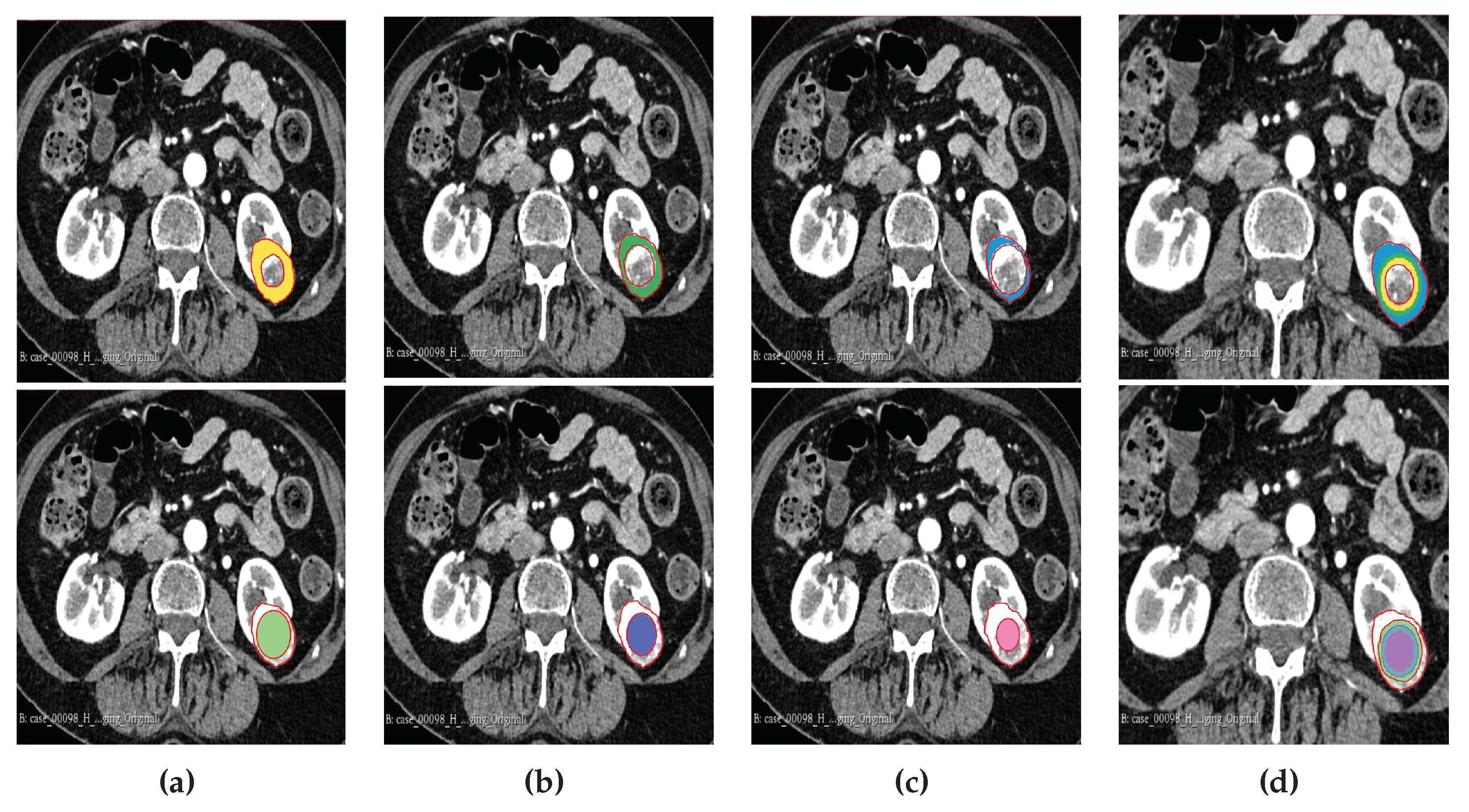

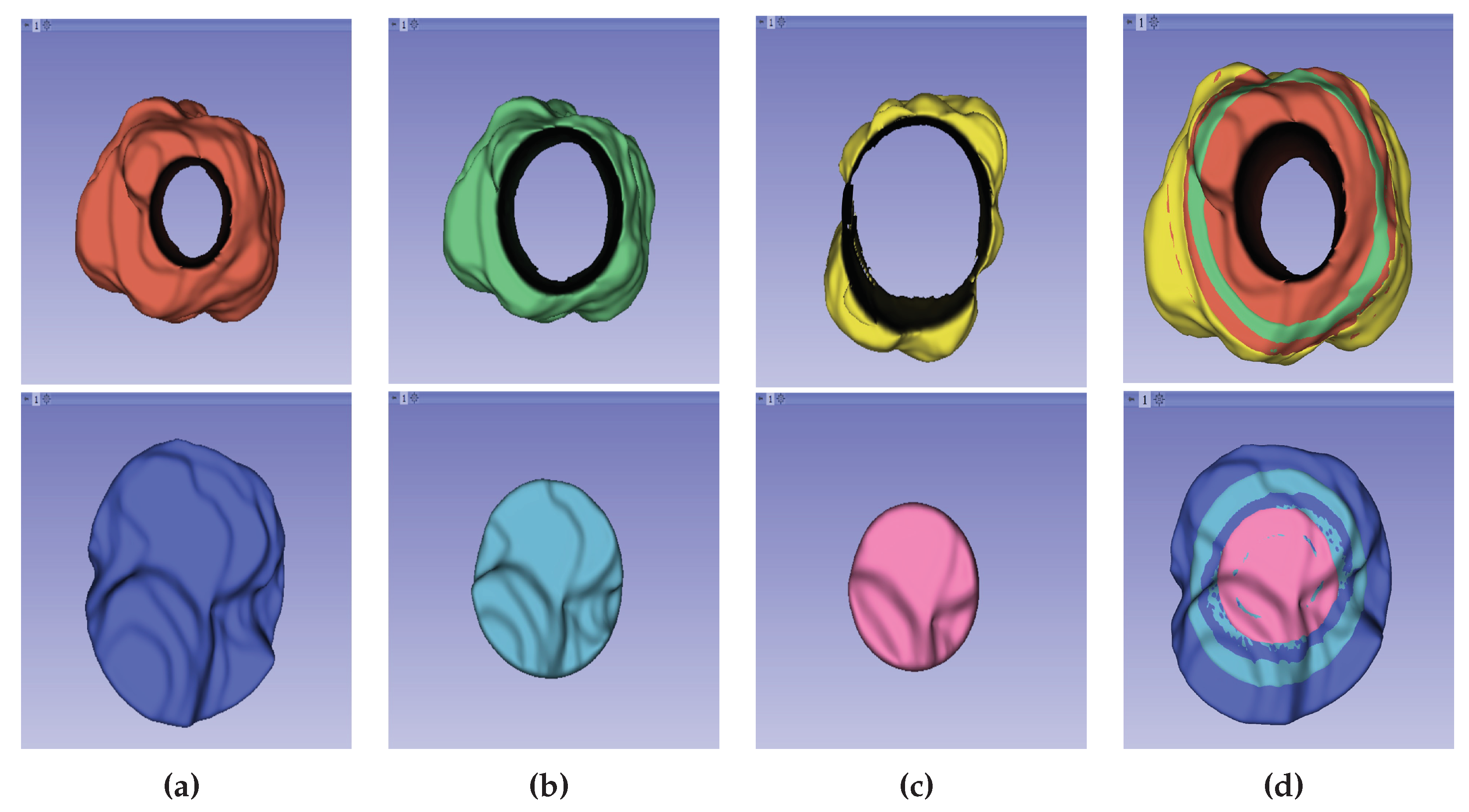

Characterising the effect of subregional intra-tumoural heterogeneity on grading in ccRCC;

Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of radiomics and ML through image-guided biopsy in determining the grade of renal masses, using resection (partial or complete) histopathology as a reference standard.

1.1. Key contributions:

Clinical Application: This research offers a practical application of radiomics and machine learning techniques in the field of oncology, specifically in the diagnosis and grading ccRCC which could potentially aid clinicians in early detection, accurate and precise treatment planning due to its higher diagnostic accuracy in comparison to traditional methods.

Subregion Heterogeneity Analysis: The inclusion of intra-tumoural subregion heterogeneity analysis highlights the depth of the research beyond simple tumour delineation and delves into the spatial distribution and variations within the tumour. This provides deeper insights into tumour biology and behaviour, leading to more personalised treatment approaches.

Potential for Non-invasive Assessment: Radiomics–machine learning algorithms, has the potential to extract valuable information from medical images non-invasively reducing the need for invasive procedures for tumour characterisation and grading, improving patient comfort and reducing healthcare costs.

4. Discussion

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma is the most common subtype of renal cell carcinoma and is responsible for the majority of renal cancer-related deaths. It comprises up to 80% of RCC diagnoses [

5], and is more likely to metastasise to other organs [

14]. Important diagnostic criteria that must be derived include tumour grade, tumour stage, and the histological type of the tumour. For most cancer patients, histological grade is a crucial predictor of local invasion or systemic metastases, which may affect how well they respond to treatment. To define the extent of the tumour, tumour staging-based clinical assessment, imaging investigations, and histological assessment are required. A greater comprehension of the neoplastic situation and awareness of the limitations of diagnostic techniques are made possible through an understanding of the procedures involved in tumour diagnosis, grading, and staging.

The grading of RCC was determined as a prognostic marker more than a hundred years ago [

20], involving the identification of a tumour as being either regular or aberrant when observed under a microscope. Hence, it is one of the factors that determines the ability of cancer to grow and spread to other adjacent cells. To accurately grade a tumour, several grading schemas have been applied, of which the WHO/ISUP and Fuhrman grading systems are the most popular and widely accepted. Previously, grading was focused on a collection of cytological characteristics of the tumour; however, nuclear morphology has more recently become a major area of focus. The Fuhrman grading system has been used for some time [

104], with its worldwide adoption in 1982 [

22]. Nuclear size, nuclear shape, and nucleolar prominence are major characteristics associated with the Fuhrman grading system [

104,

105]. In 1982, Fuhrman et al. [

22] demonstrated that grade 1, 2, 3, and 4 tumours had considerably different rates of metastasis; likewise, they also demonstrated that, when grade 2 and 3 were pooled together, there was a significant and strong correlation between tumour grade and survival [

22].

Despite these seemingly encouraging findings, there are several methodological issues with the study conducted by Fuhrman et al.; for example, its reliance on retrospective data collected over a 13-year period raises questions about potential biases [

20]. The system’s dependency on a small sample size of only 85 cases may also make its conclusions less generalisable [

20,

104]. The inclusion of several RCC subtypes without subtype-specific grading eliminated the possibility of variations in tumour behaviour [

20,

104,

106]. It is difficult to grade consistently and accurately, due to the complexity of the criteria, which call for the simultaneous evaluation of three nuclear factors (i.e., nuclear size, nuclear irregularity, and nucleolar prominence) [

104,

106], resulting in poor inter-observer reproducibility and interpretability. The lack of guidelines that can be utilised to assign weights to the different discordant parameters to achieve a final grade makes the Fuhrman system even more controversial [

104,

105]. Furthermore, the shape of the nucleus has not been well-defined for different grades [

104]. Grading discrepancies are a result of conflict between the grading criteria and a lack of direction for resolving them [

20,

23,

106]. Additionally, imprecise standards for nuclear pleomorphism and nucleolar prominence adversely affect classifications made by pathologists, resulting in increased variability [

104]. Even if a tumour is localised, grading according to the highest-grade area could result in an over-estimation of tumour aggressiveness [

20,

104]. This system’s inconsistent behaviour and poor reproducibility [

106] have raised questions regarding its dependability and potential effects on patient care and prognosis [

107]. Flaws regarding inter-observer repeatability [

107,

108], and the fact that the Fuhrman grading system is still widely used despite these flaws, indicate that there is a need for more research and better grading methods.

An extensive and co-operative effort resulted in the development of the ISUP grading system for renal cell neoplasia in 2012 as an alternative to the Fuhrman grading system [

104,

106]. The system was ratified and adopted by the WHO in 2015 and renamed as the WHO/ISUP grading system [

20,

24]. As opposed to the Fuhrman grading system, the ISUP system focuses on the prominence of nuclei as the sole parameter that should be utilised when identifying the tumour grade. This reduction in rating parameters has led to better grade distinction and increased predictive value. This has also eliminated the controversy around reproducibility that had been identified with respect to the Fuhrman grading system. Previous studies have shown that there is a clear separation between grades 2 and 3 in the WHO/ISUP grading system, which was not the case with the Fuhrman system. Indeed, in their study, Dugher et al. [

23] have highlighted the downgrade of Fuhrman grades 2 and 3 to grades 1 and 2, respectively, in the WHO/ISUP system. This indicates that, besides the overlap of grades in the Fuhrman system, there was also an over-estimation of grades—a problem that has been rectified with the WHO/ISUP grading system [

23,

49,

109]. The WHO/ISUP grading system has been highly associated with the prognoses of patients [

110]. Pre-operative imaging-guided biopsy is a diagnostic tool that is used to identify the tumour grade. However, there are inherent problems that have been identified in connection with this approach, including the fact that it is invasive in nature, causes discomfort, and may lead to other complications in patients when the procedure is performed [

35,

111]. Therefore, non-invasive testing, imaging, and clinical evaluations may be necessary to confirm the presence of ccRCC and its grade without having to undergo such a procedure. Radiomics has gained traction in clinical practice in recent years, and has been a buzzword since 2016 [

45]. It refers to the extraction of high-dimensional quantitative image features in what is known as image texture analysis, describing the pixel intensity in medical images such as X-ray images as well as CT, MRI, CT/PET, CT/SPECT, US, and mammogram scans. Radiomics approaches have been applied in a number of studies for the diagnosis, grading, and staging of tumours. Machine learning is one of the major branches of AI, providing methods that are trained on a set of known data and then tested on unknown data. In this way, researchers have attempted to make machines more intelligent through determining spatial differences in data that would have been otherwise difficult for a human being to decipher. Such approaches have been used in combination with texture analyses, particularly for tumour classification, grading, and staging. They are capable of learning and improving through the analysis of image textural features, thereby resulting in higher accuracy than native methods [

112]. Heterogeneity within tumours is a significant predictor of outcomes, with greater diversity within the tumour being potentially linked to increased tumour severity. The level of tumour heterogeneity can be represented through images known as kinetic maps, which are simply signal intensity time curves [

113,

114,

115]. Previous studies [

116,

117] that have utilised these maps typically end up averaging the signal intensity features throughout the solid mass; hence, regions with different levels of aggressiveness end up contributing equally to determining the final features. This leads to a loss of information regarding the correct representation of the tumour [

118,

119]. In some studies, there have been attempts to preserve intra-tumoural heterogeneity through extracting the features at the periphery and the core and analysing them separately [

42,

43,

44,

117]; however, this is still not sufficient, as information from other sub-regions of the tumour is not considered.

In this research, we carried out an investigation of the influences of intra-tumoural sub-region heterogeneity and biopsy on the accuracy of grading ccRCC. A total sample of 391 patients with pathologically proven ccRCC from two broad data sets was used. The objective of this work was to study the impact of intra-tumoural heterogeneity on the grading of ccRCC, comparing and contrasting ML- and AI-based methods combined with CT radiomics signatures with a biopsy and partial and radical nephrectomy in terms of determining the grade of ccRCC. Finally, the possibility of using CT radiomics ML analysis as an alternative to—and, thereby, as a replacement for—the conventional WHO/ISUP grading system in the grading of ccRCC was investigated.

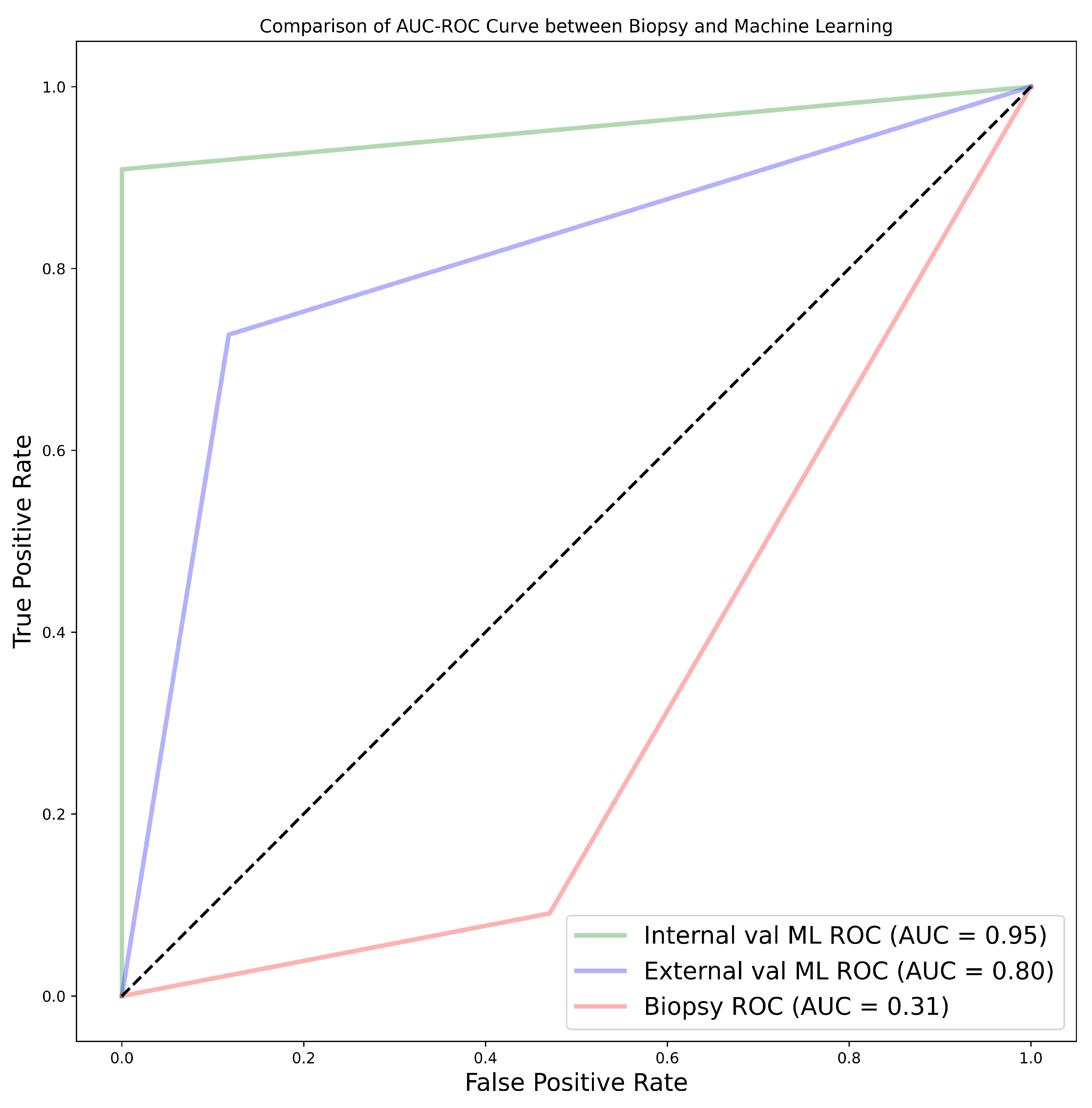

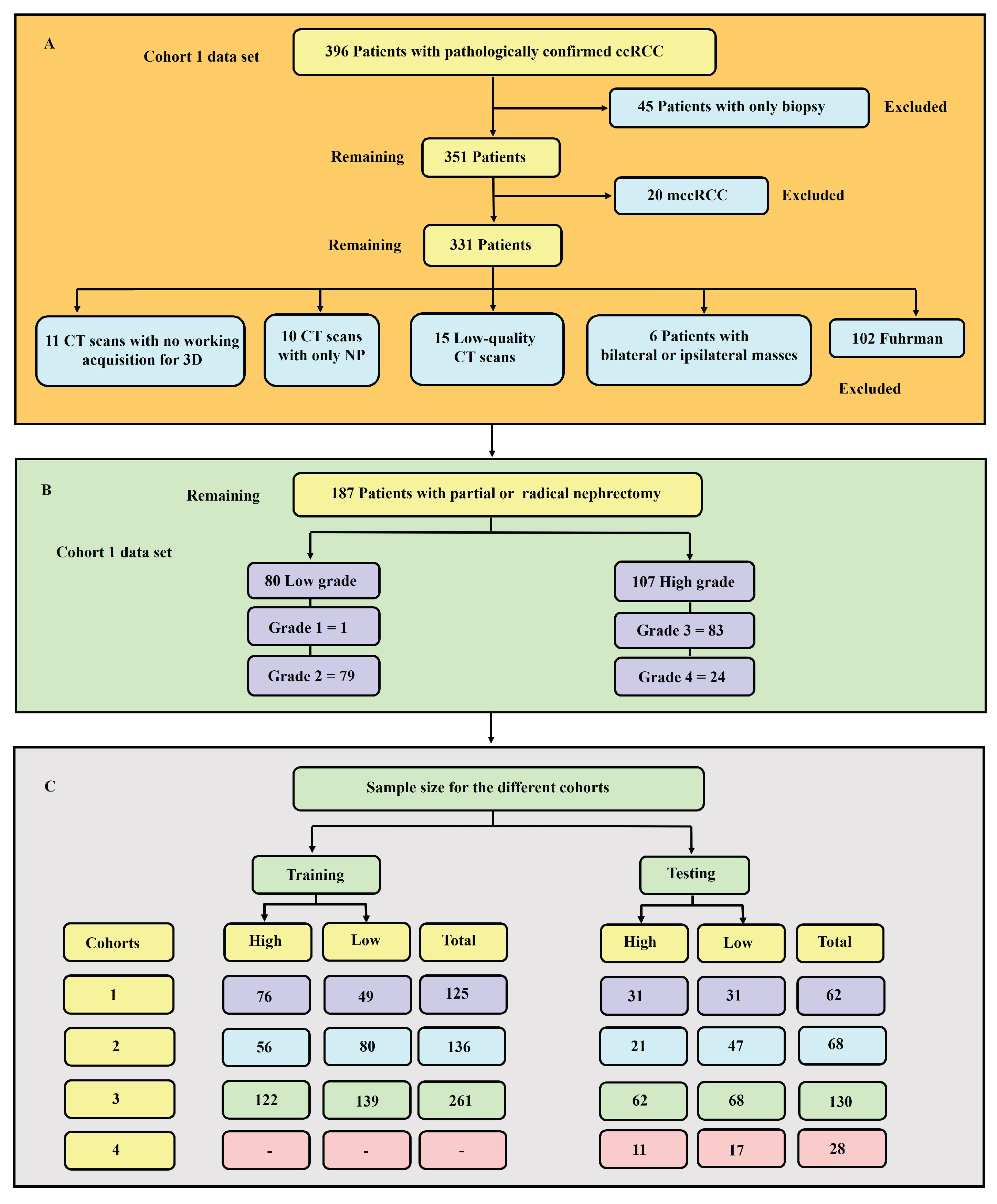

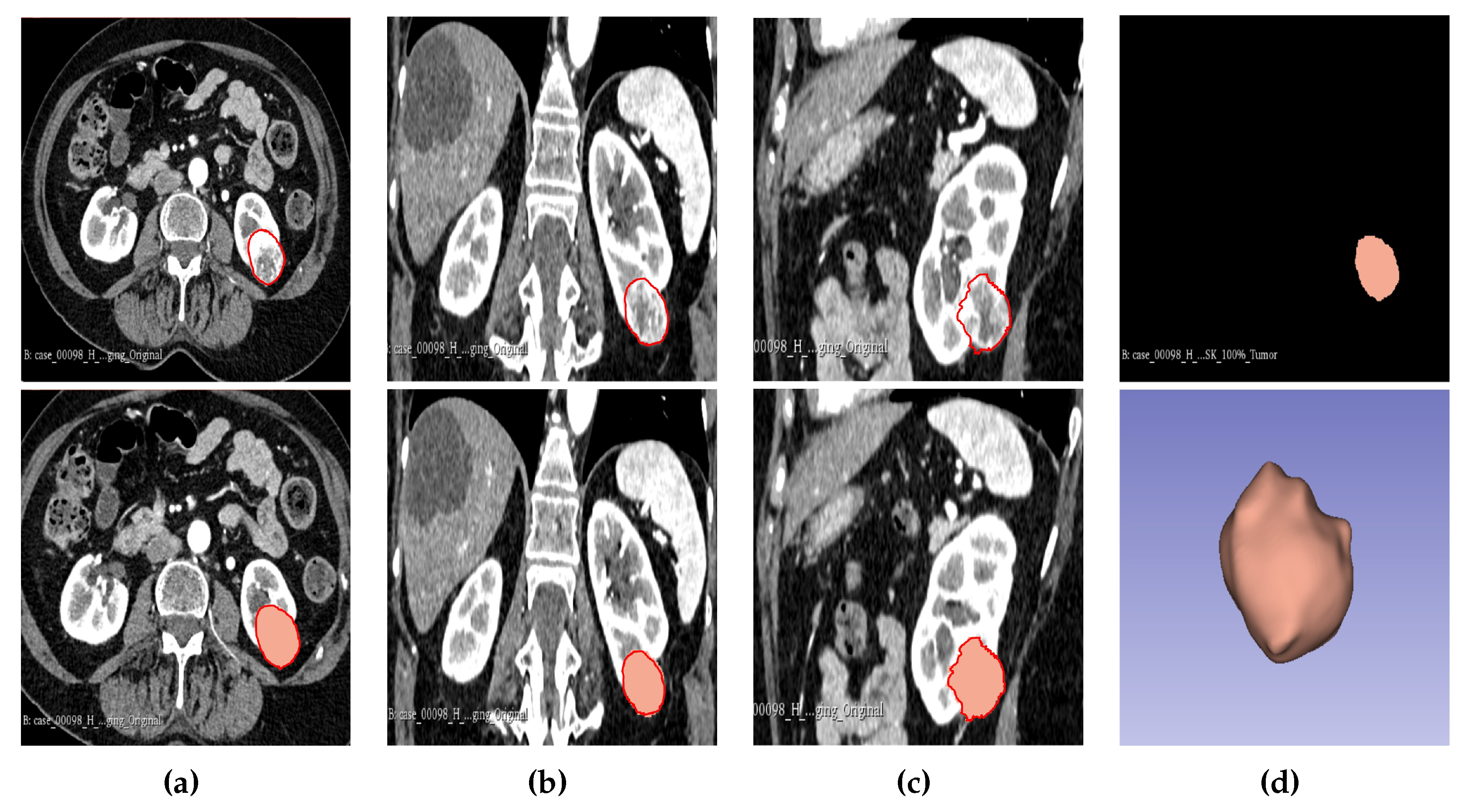

The experimental findings of our research highlighted various aspects for discussion. From the results, it was found that age, tumour size, and tumour volume were statistically significant for cohorts 1, 2, and 3. However, for cohort 4, none of the clinical features were found to be significant. Upon further analysis of the statistically significant clinical features using the point-biserial correlation coefficient (rpb), no features were verified as significant. Moreover, the 50% tumour core was identified as the best tumour sub-region, with the highest average performance for the models in cohorts 1, 2, and 3, with average AUCs of 77.91%, 87.64%, and 76.91%, respectively. It is worth noting that the 25% tumour periphery presented an increase in average performance for cohort 1, having an AUC of 78.64%; however, this result was not statistically different from that of the 50% core, and it failed to register the best performance in the other cohorts. Among the 11 classifiers, the CatBoost classifier was the best model in all three cohorts, with average AUC values of 80.00%, 86.50%, and 77.00% for cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Likewise, the best-performing distinct classifier per cohort was CatBoost, with AUC of 85% in the 100% core, 91% in the 50% periphery, and 80% in the 50% core for cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In the external validation, cohort 1 validated on cohort 2 data had the highest performance in the 25% periphery, with the highest AUC of 71% and the best classifier being QDA. Conversely, cohort 2 validated on cohort 1 data provided the best performance in the 50% core, with an AUC of 77% and the best classifier being the SVM. Finally, in the comparison between biopsy- and ML-based classification of the 28 patients who underwent both a biopsy and nephrectomy (i.e., cohort 4), the ML model was found to be more accurate, with the best AUC values for internal and external validation being 95% and 80%, respectively, in comparison to an AUC of 31% when a biopsy was performed. In this case, the nephrectomy results of grading were assumed as the ground-truth. For each of the 231 models the pathological grade of a tumour was predicted in less than 2 seconds. It is worth noting that the segmentations in cohort 1 were markedly different from those in cohort 2. Cohort 2 emerged as the highest-performing group, followed by cohort 1, while the combined cohort, notably cohort 3, exhibited the lowest performance. This disparity can be attributed to several factors, including variations in scanners, segmentations, pixel size, section thickness, tube current, tube voltage, kernel reconstruction, enhancement of contrast agent and imaging protocols. Moreover, cohort 1, in itself is a multi-institutional data set from three different centres. Refer to

Table A1–

Table A10 for comparison.

Clinical feature significance is an important aspect of such research, as it gives a general overview of the data to be used in a study. Few studies have opted to include clinical features which are statistically significant into their ML radiomics models [

120,

121]. Takahashi et al. [

121], for instance, incorporated 9 out of 12 clinical features into their prediction model due to them being statistically significant [

121]. In our study, age, tumour size, and tumour volume were found to be statistically significant; however, they were not integrated into the ML radiomics model as a confirmatory test using the point-biserial correlation coefficient revealed a lack of significance. Nonetheless, there is a lack of clear guidelines on the relationship between statistical significance and predictive significance. There is a misunderstanding that association statistics may result in predictive utility; however, association only provides information regarding a population, whereas predictive research focuses on either multi-class or binary classification of a singular subject [

122]. Moreover, the degree of association between clinical features and the outcome is affected by sample size; that is, statistical significance is likely to increase with an increase in sample size [

123]. This has been clearly portrayed in previous research, such as that of Alhussaini et al. [

48]. Even in our own research, for the cohort 4 data—despite being derived from the same population as cohort 1—the age, tumour size, tumour volume, and gender were not statistically significant, indicating that the sample size might be the likely cause. Zhao et al. [

124], in their prospective research, presented interesting findings regarding tumour sub-regions in ccRCC. In their research, they indicated that somatic copy number alterations (CANs), grade, and necrosis are higher in the tumour core, compared to the tumour margin. Our findings, obtained using different tumour sub-regions, tend to agree with the study by Zhao et al. [

124], even though the authors did not construct a predictive ML algorithm. He et al. [

125] have constructed five predictive CT scan models using an artificial neural network algorithm, in order to predict the tumour grade of ccRCC using both conventional image features and texture features. The best-performing model in their study, using the corticomedullary phase (CMP) and the texture features, provided an accuracy of 91.76%. This is comparable to our study, in which the CatBoost classifier attained the highest accuracy of 91.14%. However, He et al. [

125] did not use other metrics, which could have been useful in analysing the overall success of the prediction. For instance, the research could have depicted a high accuracy but with bias towards one class. Moreover, the research findings were not externally validated; hence, the prediction performance is unclear with respect to other data sets. Similar to He et al. [

125], Sun et al. [

86] also constructed an SVM algorithm to predict the pathological grade of ccRCC. The results of their research gave an AUC of 87%, sensitivity of 83%, and specificity of 67%. However, we found that they erred by giving an overly optimistic AUC with a very low specificity. This can easily be seen by analysing our SVM results for the best-performing SVM model, which had an AUC of 86%, sensitivity of 80.95%, and specificity of 91.49%. Our best model—the CatBoost classifier—performed much better. Xv et al. [

126] set out to analyse the performance of the SVM classifier using three feature selection algorithms for the differentiation of ccRCC pathological grades in both clinical–radiological and radiomics features. The three algorithms were the LASSO, recursive feature elimination (RFE), and ReliefF algorithms. Their best-performing model was SVM–ReliefF with combined clinical and radiomics features, with an AUC of 88% in the training set, 85% in the validation set, and 82% in the test set. It is worth noting that we used none of the feature selection algorithms used by Xv et al. [

126], but obtained better performance. Cui et al. [

127] conducted internal and external validation for the purpose of predicting the pathological grade of ccRCC. Their research achieved satisfactory performance, with internal and external validation accuracy of 78% and 61%, respectively, in the corticomedullary phase using the CatBoost classifier. Compared to their research, our results indicated better performance when the CatBoost classifier was used for both the internal and external validation, with an accuracy of 91.18% and 75.98%, respectively, in the CMP. Wang et al. [

128] also conducted a multi-centre study using a logistic regression model; however, they used both biopsy and nephrectomy as the ground-truth, despite the challenges that have been highlighted regarding biopsies. They did not report on the internal validation performance; however, their training AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were 89%, 85%, and 84%, respectively. Likewise, their external validation AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were 81%, 58%, and 95%, respectively. Their external validation performance was better than our performance using the LR model, which obtained an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 74%, 59.74%, and 88.19%, respectively. However, in general, our CatBoost classifier still out-performed their LR model. Moldovanu et al. [

129] investigated the use of multi-phase CT using LR to predict the WHO/ISUP nuclear grade of ccRCC. When our results were compared with their validation set, which yielded an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 81%, 72.73%, and 75.90% in the corticomedullary phase, our research exhibited higher performance not only in the best-performing model but also in the LR model, which obtained an AUC, sensitivity, and specificity of 84%, 71.43%, and 95.75%, respectively.

Yi et al. [

130] have performed research for prediction of the WHO/ISUP pathological grade of ccRCC using both radiomics and clinical features with an SVM model. The 264 samples used were from the nephrographic phase (NP). We noted that there was a massive class imbalance in the data, with a ratio between low- and high-grade samples of 78:22; however, they did not highlight how this issue was resolved. Nonetheless, the testing accuracy yielded an AUC of 80.17%, lower than that obtained in our research. Similar to our study, Karagöz and Guvenis [

93] constructed a 3D radiomic feature-based classifier to determine the nuclear grade of ccRCC using the WHO/ISUP grading system. The best results were obtained using the LightGBM model, which obtained an AUC of 0.89. They also carried out tumour dilation and contraction by 2 mm, which led them to conclude that the ML algorithm is robust against deviation in segmentation by observers. Our best model out-performed their results and our sample size was much larger, thereby providing more trustworthy results. Demirjian et al. [

49] also constructed a 3D model using data from two institutions using RF, AdaBoost, and ElasticNet classifiers. The best-performing model, RF, obtained an AUC of 0.73. This model performance was lower than in our research. The use of a data set graded using the Fuhrman system for testing may have led to poor results, as WHO/ISUP and Fuhrman use different parameters for grading; hence, it is impossible to use the Fuhrman grade as the ground-truth for a model trained using WHO/ISUP. Shu et al. [

65] have extracted radiomics features from the CMP and NP to construct 7 ML algorithms, with the best model in the CMP (i.e., the MLP algorithm) achieving an accuracy of 0.974. The findings of this study are quite interesting, but the gold standard used for grade prediction was not discussed; this may lead us to the conclusion that biopsy was part of the gold standard. We have highlighted the controversies surrounding biopsies and, accordingly, the research may have been affected by such issues. There are some studies which have applied deep learning for the prediction of tumour grade [

131,

132,

133]. The AUC in these studies ranged from 77.00% to 88.20%. These results are not only worse than those obtained in the current research, but the Fuhrman grading system was also used as the gold standard. A biopsy is a commonly used diagnostic tool for the identification of RCC subtypes. The diagnostic accuracy of a biopsy for RCC has been reported to range from 86 to 98%, but this can be influenced by various factors [

35,

134,

135]. Notably, when it comes to grading RCC, the range of accuracy widens to between 43 and 76% [

35,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141]. Nevertheless, a biopsy’s accuracy in classifying renal cell tumours is debatable (Millet et al., 2012). Different studies have contended that a kidney biopsy typically understates the final grade. For instance, biopsies underestimated the nuclear grade in 55% of instances and only properly identified 43% of the final nuclear grades [

136]. In particular, the final nuclear grade was marginally more likely to be understated in biopsies of larger tumours, while histologic subtype analysis yielded more accurate results; especially when evaluating clear cell renal tumours. In the research by Blumenfeld et al. [

136], only one case of the nuclear grade being over-estimated was reported. In the study of Millet et al. [

138], biopsy led to under-estimation of the grade in 13 cases while, in 2 cases, it over-estimated the grade. In our study, we found that the accuracy of biopsy was 35.71% in determining the tumour grade, with a sensitivity and specificity of 9.09% and 52.94%, respectively, in the 28 NHS samples (cohort 4) when nephrectomy was used as a gold standard. These results are in agreement with previous studies determining biopsy to perform poorly in terms of predicting tumour grade. The results obtained through biopsies were compared to our ML models, and the models out-performed biopsies by far; in fact, our worst-performing model was still better than biopsy. The best model had an accuracy of 96.43%, sensitivity of 90.91%, and specificity of 100% in the internal validation, comprising a 60.72% improvement in accuracy. Likewise, in the external validation, there was a 46.43% improvement in accuracy, with an accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of 82.14%, 72.73%, and 88.24%, respectively. Therefore, we can conclude that ML approaches are able to distinguish low- from high-grade ccRCC with better accuracy, when compared to biopsy, and thus should be considered as a replacement.

In previous research, no paper has tackled the effect of tumour sub-region with regard to the grading of ccRCC; hence, there were no studies with which our results could be compared. The current research dived deeper into the possibility of pre-operatively grading ccRCC without the need for biopsy. Moreover, the effect of the information contained in different tumour sub-regions on grading was analysed. It is the belief of the authors of this research that the results of this study will assist clinicians in finding the best management strategies for patients of ccRCC, as well as enabling informative pre-treatment assessments that allow treatments to be tailored to individual patients.

4.0.1. Limitations and Future research

The work encountered a few challenges which are important to highlight. The samples used in this study were obtained from different institutions, and the scans were captured using different scanners and protocols. This may have lowered the overall performance of the models. However, it was important to use such data as the research was not meant to be institution-specific but, instead, generally applicable. Second, the retrospective nature of the research may have limited our work, and it is therefore recommended that more research should be conducted through a prospective study. Third, the current research assumed that the divided tumour sub-regions (25%, 50%, and 75% core and periphery) are heterogeneous in nature. In this regard, more research using pixel intensity measures from different tumour sub-regions is encouraged. Fourth, manual segmentation is not only time-consuming but also subject to observer variability; thus, research on automated tumour image segmentation techniques is encouraged. Fifth, the predominant approach to grading ccRCC studies revolves around utilising a binarised model output. This is motivated by two primary factors. First, there exists a notable discrepancy in the sample sizes across different grades, with grades 1 and 4 exhibiting smaller cohorts compared to grades 2 and 3. Second, adopting a 4-class model is perceived to yield minimal impact on patient management, given the similarity in management strategies between low grades (I and II) and high grades (III and IV) [

142]. Nonetheless, there is merit in exploring the application of a 4-class model in forthcoming investigations, as doing so may validate the suitability of radiomics machine learning analyses in delineating distinct WHO/ISUP grading categories. Moreover, despite this being one of the few studies which has used a large sample size, we still consider our sample size to be small with respect to ML and AI approaches, which often require larger data sets for training. Finally, it’s advisable to undertake a deep learning study using a substantial data set based on the WHO/ISUP grading systems.

4.0.2. Take-home messages:

Radiomics features combined with ML algorithms have the potential to predict the WHO/ISUP grade of ccRCC more accurately than pre-operative biopsy.

Analysing different tumor subregions, such as the 50% tumor core and 25% tumor periphery, provides valuable information for determining tumor grade.

Analysing different cohorts from both single and multi-centre studies represented the effect of data heterogeneity on the model’s performance. This underscores the importance of implementing a robust model that generalises well for real-world applications in grading ccRCCs.

The study highlighted the promising application of advanced imaging techniques and ML in oncology for precise tumor grading.