Submitted:

18 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

2.2. Animals and Management

2.3. Experimental design

2.4. Determination of tilmicosin

2.5. HPLC method validation

2.6. Data analysis

3. Results

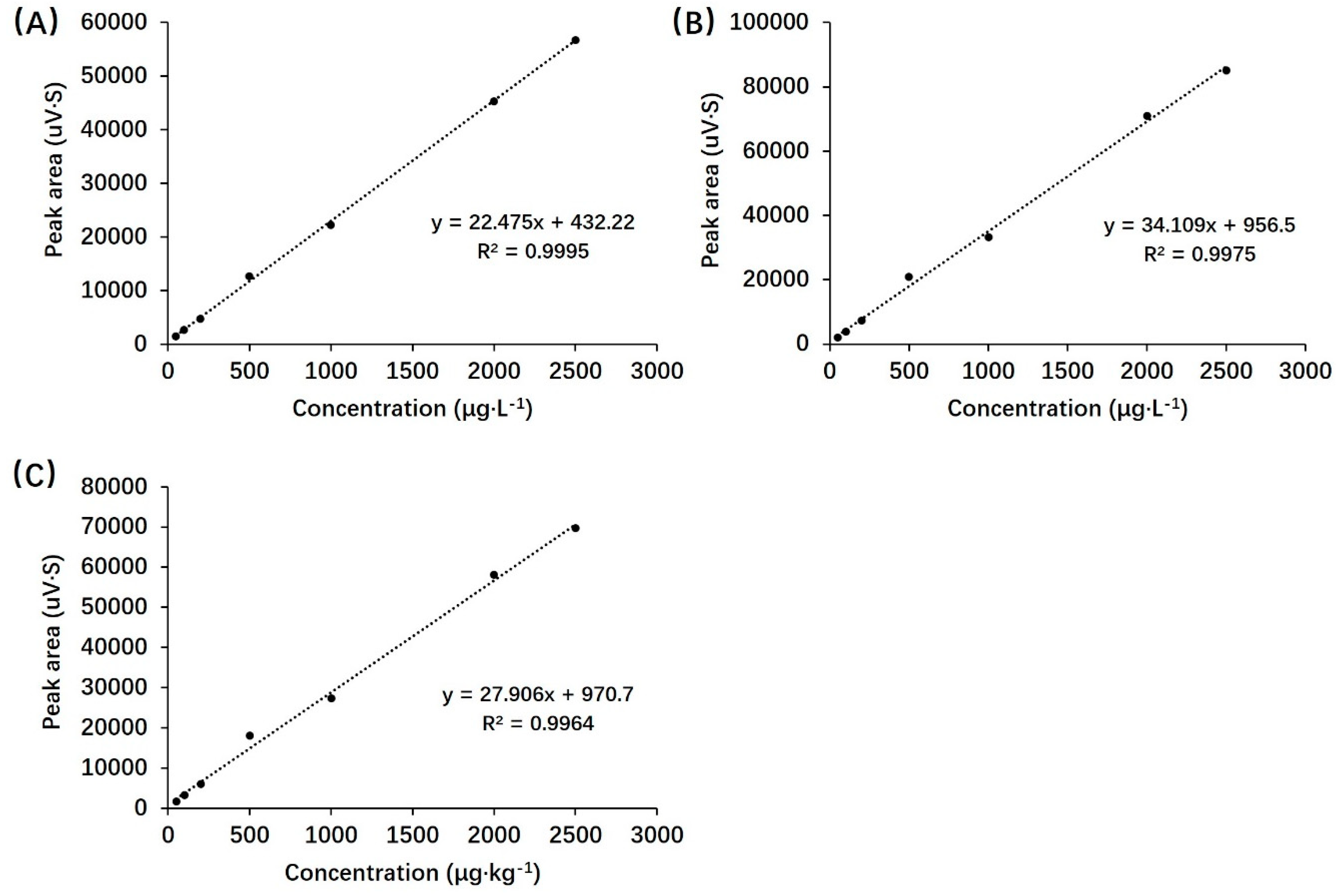

3.1. Validation parameters

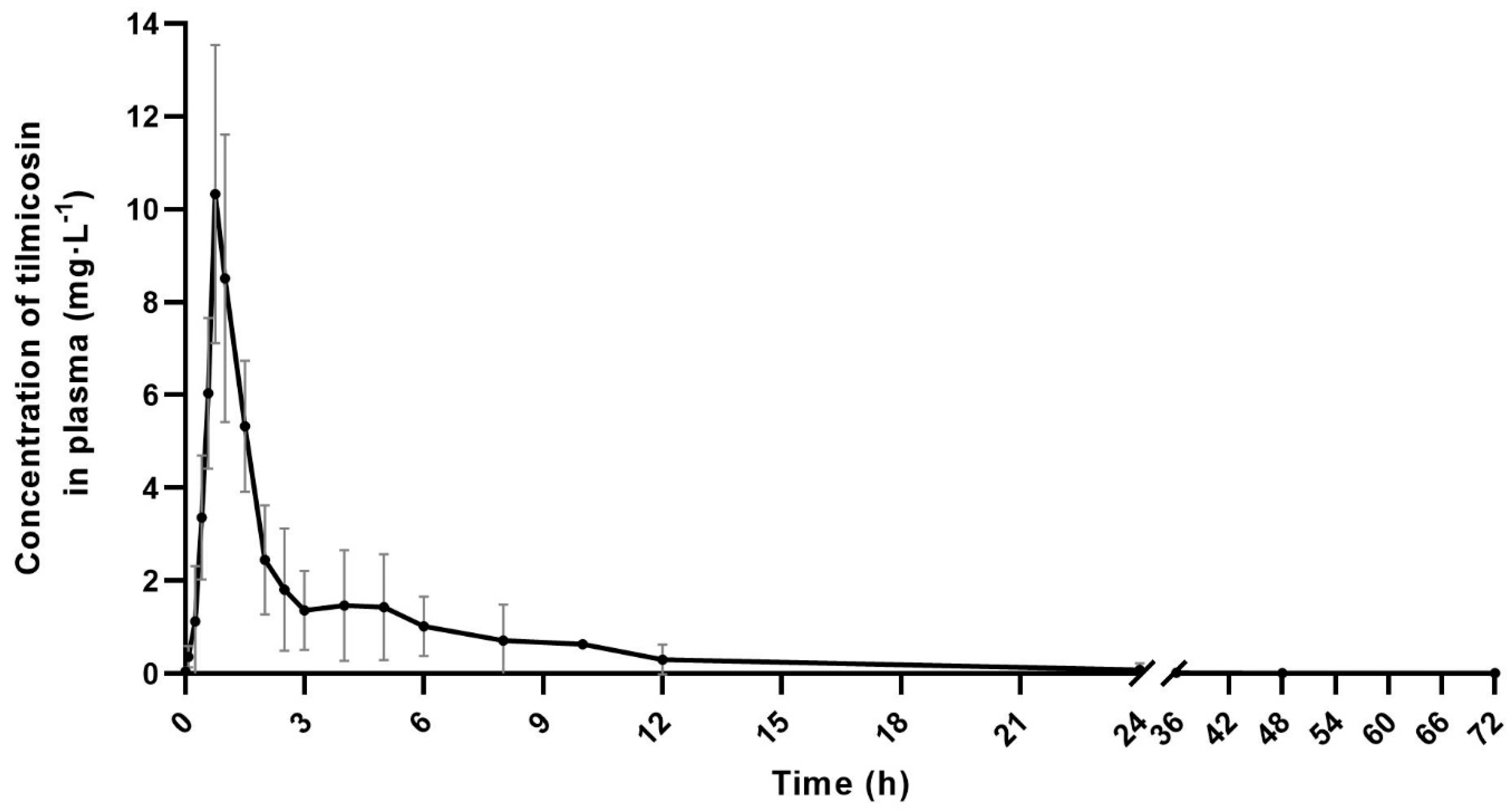

3.2. Pharmacokinetic parameters of plasma tilmicosin

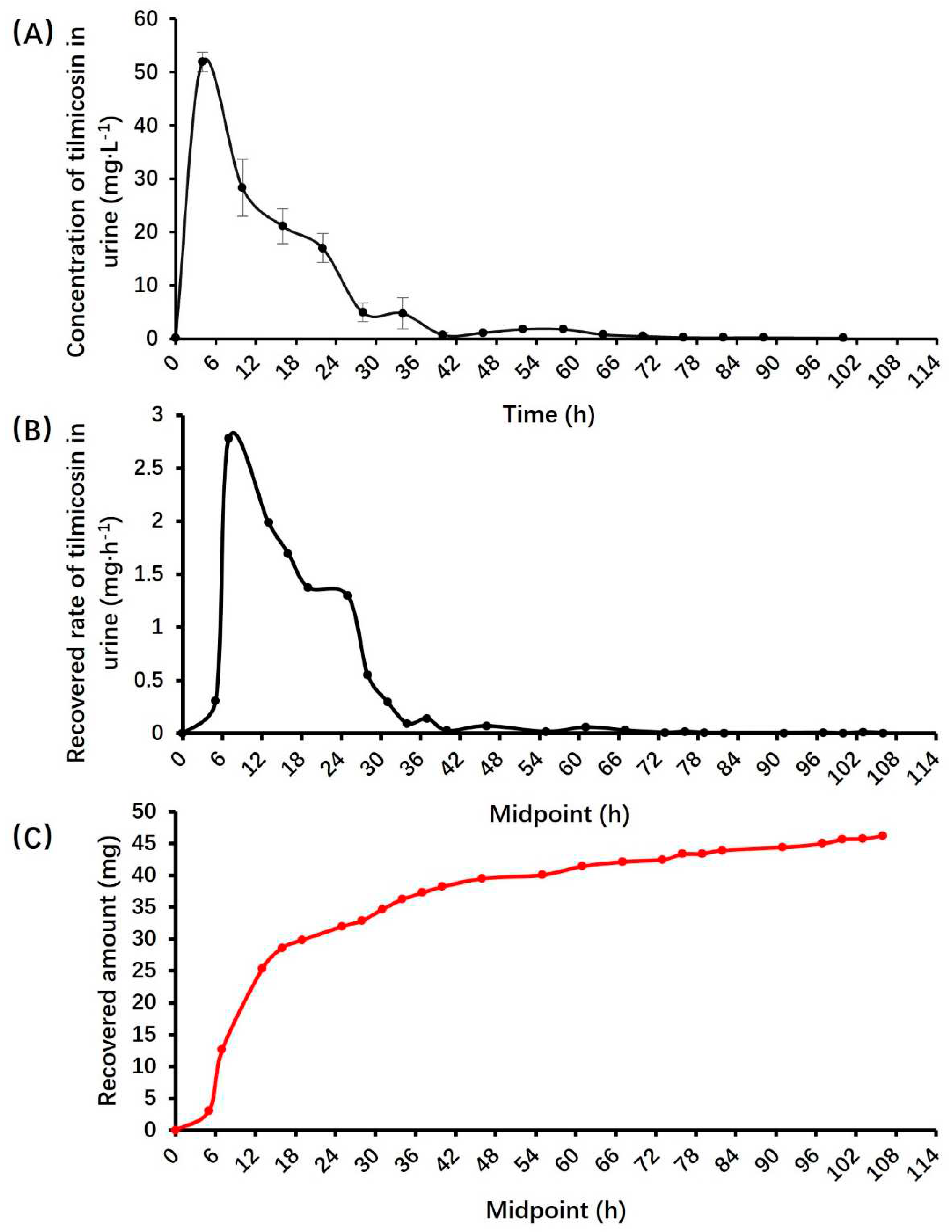

3.3. Pharmacokinetic parameters of tilmicosin in urine

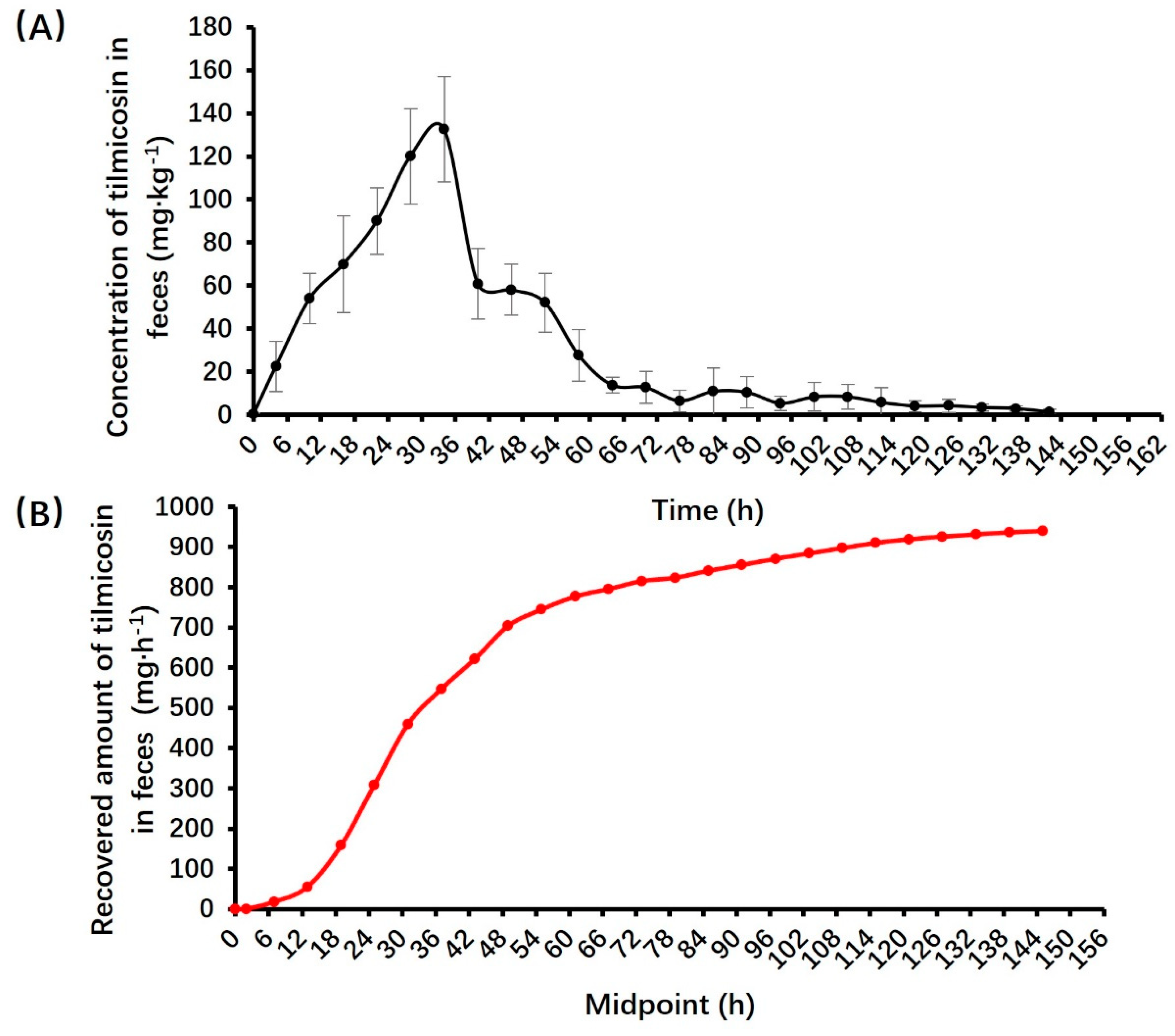

3.3. Pharmacokinetic parameters of tilmicosin in feces

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Villarino, N.; Martín-Jiménez, T. Pharmacokinetics of macrolides in foals. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2013, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Cortés, I.; Acevedo-Domínguez, N.A.; Olguin-Alor, R.; Cortés-Hernández, A.; Álvarez-Jiménez, V.; Campillo-Navarro, M.; Sumano-López, H.S.; Gutiérrez-Olvera, L.; Martínez-Gómez, D.; Maravillas-Montero, J.L.; et al. Tilmicosin modulates the innate immune response and preserves casein production in bovine mammary alveolar cells during staphylococcus aureus infection. Journal of animal science 2019, 97, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Laslop, N.; Mankin, A.S. How macrolide antibiotics work. Trends in biochemical sciences 2018, 43, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charleston, B.; Gate, J.J.; Aitken, I.A.; Reeve-Johnson, L. Assessment of the efficacy of tilmicosin as a treatment for mycoplasma gallisepticum infections in chickens. Avian pathology : Journal of the W.V.P.A 1998, 27, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ose, E.E. In vitro antibacterial properties of el-870, a new semi-synthetic macrolide antibiotic. The Journal of antibiotics 1987, 40, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziv, G.; Shem-Tov, M.; Glickman, A.; Winkler, M.; Saran, A. Tilmicosin antibacterial activity and pharmacokinetics in cows. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 1995, 18, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inamoto, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Iijima, H.; Kawashima, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Ogimoto, K. Antibacterial activity of tilmicosin against pasteurella multocida and actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae isolated from pneumonic lesions in swine. The Journal of veterinary medical science 1994, 56, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modric, S.; Webb, A.I.; Derendorf, H. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tilmicosin in sheep and cattle. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 1998, 21, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giguère, S. Macrolides, azalides, and ketolides. In Antimicrobial therapy in veterinary medicine, 4th ed.; 2013; pp. 211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Avci, T.; Elmas, M. Milk and blood pharmacokinetics of tylosin and tilmicosin following parenteral administrations to cows. The Scientific World Journal 2014, 2014, 869096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorneaux, B.; Shryock, T.R. Intracellular accumulation, subcellular distribution, and efflux of tilmicosin in bovine mammary, blood, and lung cells. Journal of dairy science 1999, 82, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, W.H.; Byrd, R.A.; Cochrane, R.L.; Hanasono, G.K.; Hoyt, J.A.; Main, B.W.; Meyerhoff, R.D.; Sarazan, R.D. A review of the toxicology of the antibiotic micotil 300. Veterinary and human toxicology 1993, 35, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clark, C.; Dowling, P.M.; Ross, S.; Woodbury, M.; Boison, J.O. Pharmacokinetics of tilmicosin in equine tissues and plasma. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2008, 31, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, T.; Lu, M.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W. Preparation and evaluation of tilmicosin-loaded hydrogenated castor oil nanoparticle suspensions of different particle sizes. International journal of nanomedicine 2014, 9, 2655–2664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, E. Donkey and mule welfare. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Equine practice 2019, 35, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Liu, S.; Liang, Q.; Lin, J.; Jiang, L.; Chen, F.; Wei, Z. Analysis of heparan sulfate/heparin from colla corii asini by liquid chromatography-electrospray ion trap mass spectrometry. Glycoconjugate journal 2019, 36, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickards, K.J.; Thiemann, A.K. Respiratory disorders of the donkey. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Equine practice 2019, 35, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Womble, A.; Giguère, S.; Murthy, Y.V.; Cox, C.; Obare, E. Pulmonary disposition of tilmicosin in foals and in vitro activity against rhodococcus equi and other common equine bacterial pathogens. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2006, 29, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, C.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, S.; Guo, P.; Ding, S.; Li, X. Pharmacokinetics of tilmicosin after oral administration in swine. American journal of veterinary research 2005, 66, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, K.R.; Portillo, T.; Hassfurther, R.; Hunter, R.P. Pharmacokinetics of tilmicosin in beef cattle following intravenous and subcutaneous administration. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2011, 34, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yan, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, M.; Song, S.; Yao, Z.; Jia, Y.; Yuan, S. Pharmacokinetics of tilmicosin in chicken joints based on a novel microdialysis sampling method. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2023, 46, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, J.; Jia, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zhou, M.; Song, S.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, N. The pharmacokinetics of tilmicosin in plasma and joint dialysate in an experimentally mycoplasma synoviae infection model. Poultry science 2023, 102, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallina, G.; Lucatello, L.; Drigo, I.; Cocchi, M.; Scandurra, S.; Agnoletti, F.; Montesissa, C. Kinetics and intrapulmonary disposition of tilmicosin after single and repeated oral bolus administrations to rabbits. Veterinary research communications 2010, 34 (Suppl 1), S69-72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, C.; Mao, C.; Cai, Q.; Shen, X.; Ding, H. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of tilmicosin in plasma and lung tissue in healthy chickens and chickens experimentally infected with mycoplasma gallisepticum. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2020, 43, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Qin, H.; Chen, D.; Wu, M.; Meng, K.; Zhang, A.; Pan, Y.; Qu, W.; Xie, S. The dose regimen formulation of tilmicosin against lawsonia intracellularis in pigs by pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (pk-pd) model. Microbial pathogenesis 2020, 147, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ji, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Ding, H. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic integration of tilmicosin against pasteurella multocida in a piglet tissue cage model. Frontiers in veterinary science 2023, 10, 1260990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Song, J.S.; Ahn, S. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of (13)c-labeled succinic acid in mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.V.; Fanget, M.C.; MacLauchlin, C.; Clausen, V.A.; Li, J.; Cloutier, D.; Shen, L.; Robbie, G.J.; Mogalian, E. Clinical and preclinical single-dose pharmacokinetics of vir-2218, an rnai therapeutic targeting hbv infection. Drugs in R&D 2021, 21, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Su, M.; Cheng, W.; Xia, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, R.; Sun, S.; Feng, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, urinary excretion, and pharmaco-metabolomic study of tebipenem pivoxil granules after single escalating oral dose in healthy chinese volunteers. Frontiers in pharmacology 2021, 12, 696165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Woodbury, M.; Dowling, P.; Ross, S.; Boison, J.O. A preliminary investigation of the disposition of tilmicosin residues in elk tissues and serum. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2004, 27, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Basha, E.A.; Idkaidek, N.M.; Al-Shunnaq, A.F. Pharmacokinetics of tilmicosin (provitil powder and pulmotil liquid ac) oral formulations in chickens. Veterinary research communications 2007, 31, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ba, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Wu, F.; Li, Z.; Deng, H.; Yang, H. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of solid dispersion formulation of tilmicosin in pigs. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2021, 44, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, S.; Cao, J.; Qiu, Y. Tilmicosin enteric granules and premix to pigs: Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and comparative pharmacokinetics. Journal of veterinary pharmacology and therapeutics 2019, 42, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Yun, H. Postantibiotic effects and postantibiotic sub-mic effects of erythromycin, roxithromycin, tilmicosin, and tylosin on pasteurella multocida. International journal of antimicrobial agents 2001, 17, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Jimenez, L.E.; Aranda-Aguirre, E.; Castelan-Ortega, O.A.; Shettino-Bermudez, B.S.; Ortiz-Salinas, R.; Miranda, M.; Li, X.; Angeles-Hernandez, J.C.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; Gonzalez-Ronquillo, M. Worldwide traceability of antibiotic residues from livestock in wastewater and soil: A systematic review. Animals : An open access journal from MDPI 2021, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bogaard, A.E.; Stobberingh, E.E. Antibiotic usage in animals: Impact on bacterial resistance and public health. Drugs 1999, 58, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perruchon, C.; Katsivelou, E.; Karas, P.A.; Vassilakis, S.; Lithourgidis, A.A.; Kotsopoulos, T.A.; Sotiraki, S.; Vasileiadis, S.; Karpouzas, D.G. Following the route of veterinary antibiotics tiamulin and tilmicosin from livestock farms to agricultural soils. Journal of hazardous materials 2022, 429, 128293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atef, M.; Abo el-Sooud, K.; Nahed, E.; Tawfik, M. Elimination of tilmicosin in lactating ewes. DTW. Deutsche tierarztliche Wochenschrift 1999, 106, 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Feinman, S.E.; Matheson, J.C. Draft environmental impact statement: Subtherapeutic antibacterial agents in animal feeds. Food and drug administration department of health education and welfare report.; Washington DC, 1978; p 72.

- Sides, G.D.; Cerimele, B.J.; Black, H.R.; Busch, U.; DeSante, K.A. Pharmacokinetics of dirithromycin. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 1993, 31 (Suppl C), 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Donkey name | ± s | |||

| Jacob | Joshua | Matthew | William | ||

| Body weight (kg) | 148.00 | 140.00 | 145.00 | 135.00 | 142.00±4.95 |

| Single administered dose (mg · kg-1) | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | - |

| Administered dose (mg) | 1480.00 | 1400.00 | 1450.00 | 1350.00 | 1420.00±49.50 |

| Concentrated feed intake (kg · d-1) | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | - |

| Coarse fodder intake (kg · d-1) | 2.06 | 2.39 | 1.76 | 2.24 | 2.11±0.23 |

| Total feces volume (kg) | 41.65 | 43.55 | 31.45 | 34.80 | 37.86±4.93 |

| Water intake (L · d-1) | 8.21 | 6.03 | 6.79 | 8.21 | 7.31±0.94 |

| Total urine volume (L) | 6.37 | 4.87 | 6.68 | 4.53 | 5.61±0.93 |

| Spike level (μg·L-1)/(μg·kg-1) |

Average Recovery(%) | ||

| Plasma | Urine | Feces | |

| 50 | 87.53±2.04 | 87.93±2.78 | 82.60±3.71 |

| 500 | 84.73±2.37 | 91.33±3.35 | 79.00±1.02 |

| 5000 | 86.38±4.64 | 86.22±3.29 | 80.13±3.07 |

| Items | Donkey name | ± s | |||

| Jacob | Joshua | Matthew | William | ||

| λz (1·h-1) | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.06±0.02 |

| T1/2λz (h) | 10.40 | 12.76 | 8.41 | 26.39 | 14.49±7.04 |

| Tmax (h) | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.81±0.11 |

| Cmax (mg·L-1) | 5.69 | 5.10 | 18.82 | 15.34 | 11.23±5.97 |

| AUC0-∞ (mg·L-1·h) | 20.09 | 12.05 | 29.64 | 36.96 | 24.69±9.43 |

| MRT (h) | 11.71 | 8.83 | 5.84 | 5.82 | 8.05±2.44 |

| Cl/F (L·kg-1·h-1) | 0.50 | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.48±0.22 |

| Vd/F (L·kg-1) | 7.47 | 15.27 | 40.96 | 10.30 | 9.28±4.10 |

| Items | Donkey name | ± s | |||

| Jacob | Joshua | Matthew | William | ||

| λz (1/h) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06±0.01 |

| T1/2λz (h) | 8.99 | 11.08 | 12.18 | 17.82 | 12.52±3.29 |

| Time of maximum rate (h) | 7.00 | 7.00 | 16.00 | 25.00 | 13.75±7.46 |

| Maximum excretion rate (mg · h-1) | 3.22 | 2.34 | 1.70 | 2.86 | 2.53±0.57 |

| AURC0-∞ (mg) | 47.75 | 40.92 | 24.50 | 42.63 | 38.95±8.71 |

| Recovered amount (mg) | 45.57 | 35.78 | 27.62 | 31.24 | 35.05±6.73 |

| Recovered percent (%) | 3.09 | 2.56 | 1.90 | 2.31 | 2.47±0.43 |

| Items | Donkey name | ± s | |||

| Jacob | Joshua | Matthew | William | ||

| Recovered amount (mg) | 815.77 | 875.09 | 1008.52 | 1060.14 | 939.88±98.46 |

| Recovered percent (%) | 55.12 | 62.51 | 69.55 | 78.53 | 66.43±8.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).