1. Introduction

The gastrointestinal (GI) microbiome is a large, diverse, and complex community of microorganisms, known to play significant roles in both health and disease, affecting host metabolism, immune function and physiology (i.e., gut structure) [

1]. As with any ecosystem, the balance of these communities depends on several factors including the host’s age, diet, environment, and health status and changes when exposed to different stimuli. The maintenance of a stable community is vital to host health and depends on the level of microbiome resistance (ability to withstand adversity in a challenge) and resilience (pace of return to initial composition) [

2]. Dysbiosis often refers to the changes observed in response to a challenge (i.e., immune stressor, medication), traditionally observed through a reduction of overall microbial diversity, in combination with a loss of beneficial bacteria and increase in pathobionts, and overall functional alterations of the microbiota community [

3,

4,

5].

Chronic enteropathies (CE) can be characterized by persistently chronic (≥ 3 weeks) GI signs of disease (i.e., weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, lethargy, anorexia) but its diagnosis is reliant on an elimination of extraintestinal factors as causes of disease [

5,

6,

7,

8]. As clinical signs alone cannot diagnose CE, analysis of microbial abundances, microbial metabolites, and/or intestinal markers may be used to aid in disease diagnosis and provide further insight into pathogenesis. Quantifying these analytes and biomarkers, and understanding their importance to host health, may assist in the management of clinical diseases.

The most common strategies for remission of CE include dietary interventions, steroids/immunosuppressive drugs, antibiotics or, in more recent years, fecal microbial transplants. Antibiotics can be useful in the treatment of infections, as they can be efficacious in reducing microbial load. However, the overuse and misuse of antibiotics can lead to the development of antimicrobial resistance, potentially leading to a larger threat to global health in humans and companion animals [

9,

10]. Despite being a common treatment, a few studies have demonstrated that post-antibiotic dysbiosis can occur and result in negative side effects relating to the GI tract and central nervous system [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Although limited research in cats exists, it has been shown that antibiotic administration results in dysbiosis and consequent effects on GI health (i.e., hyporexia, vomiting, diarrhea) [

15,

16,

17].

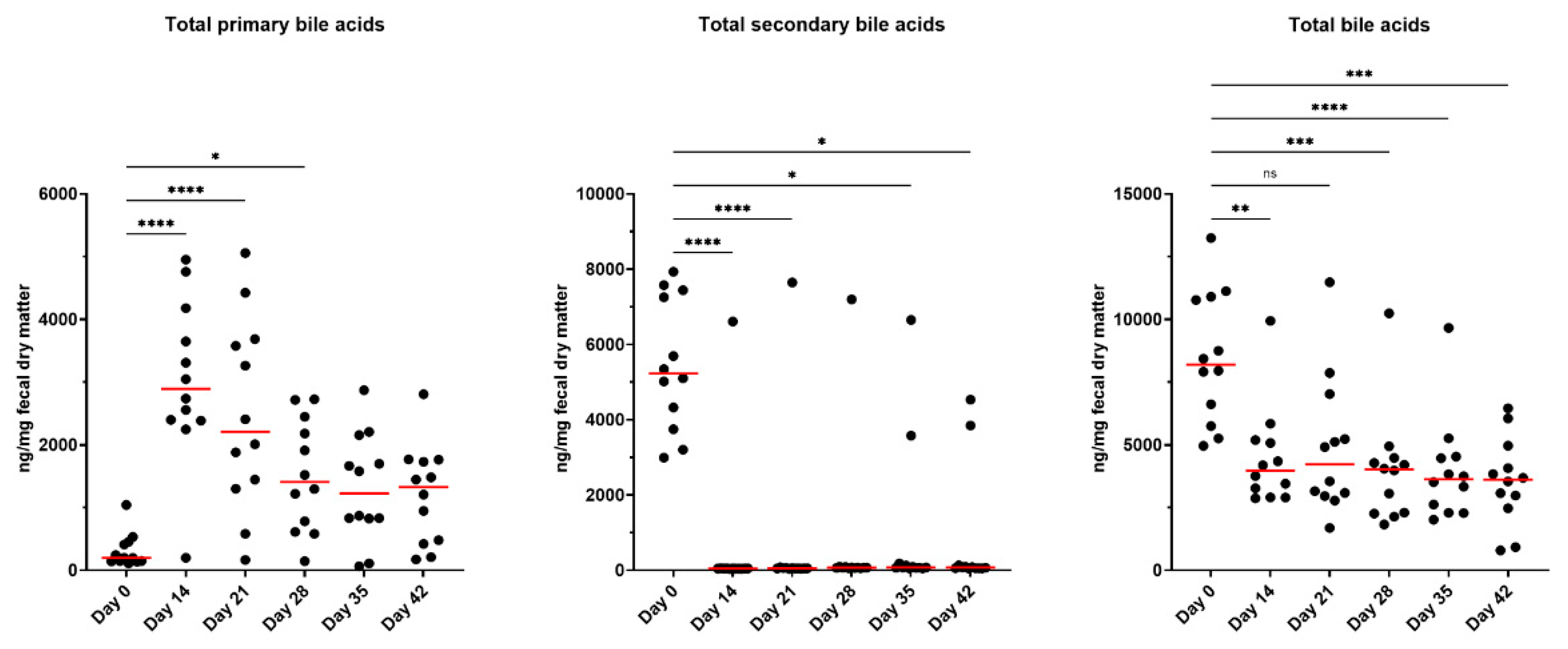

Metronidazole is a potent bactericidal antibiotic with high efficacy in treating giardia and severe GI infections in dogs, demonstrating that it can reduce microbial abundance and affect microbial metabolism as quantified by fecal microbial-derived metabolites [e.g., bile acids (BA)] [

14]. Primary BA are synthesized by the host (conjugated with taurine or glycine) and used to aid in lipid digestion, with the majority being reabsorbed and recycled. Any that escape reabsorption are exposed to colonic microbes with the ability to biotransform primary BA into secondary BA. Previously reported in dogs and cats, a higher primary BA concentration is common in animals with CE or after treatment with antibiotics [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. In more recent years,

Peptacetobacter (previously

Clostridium)

hiranonis, has been shown to be the predominate species with the ability to convert primary BA into secondary BA in dogs and cats via 7α-dehydroxylation enzymes produced by the

baiCD gene [

14,

24,

25]. The abundance of

P. hiranonis is strongly correlated with fecal secondary BA concentrations, with a reduction observed in dogs following metronidazole administration [

26]. Therefore, reduced

P. hiranonis results in an imbalanced BA profile, which is commonly observed in chronic GI disease or with antibiotic administration [

1,

21,

22,

23,

27,

28].

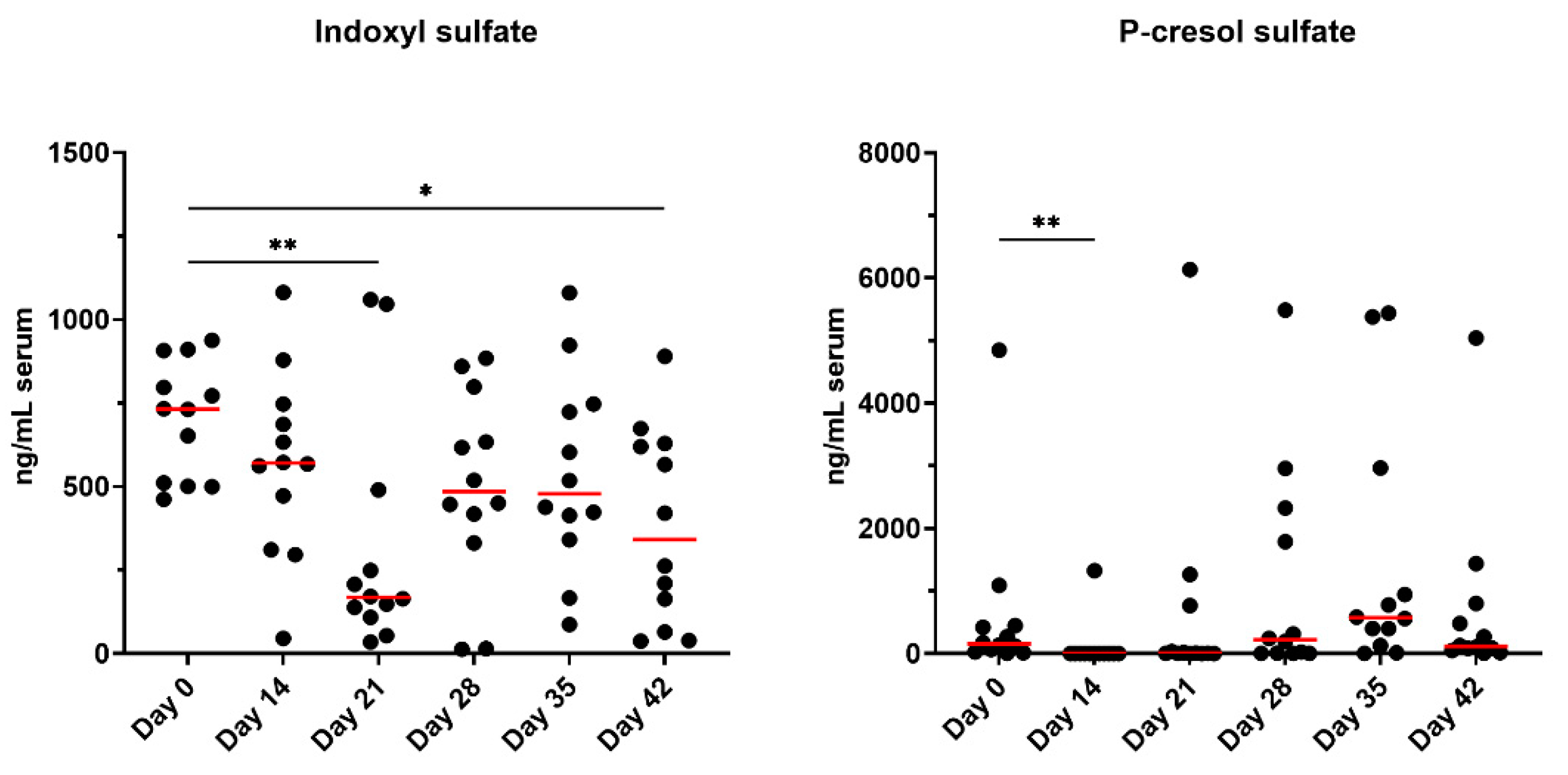

Additionally, serum BA and uremic toxins [indoxyl sulfate (IS), p-cresol sulfate (PCS)] may serve as potential biomarkers of GI dysfunction; however, there is limited research on their concentrations in antibiotic-treated cats or their health implications. Beginning as products of amino acid metabolism by bacteria

, indole and p-cresol are absorbed and transported to the liver, where they are converted by sulfotransferases into IS and PCS before being excreted via urine. In cats with chronic kidney disease, uremic toxins accumulate and can lead to disease progression, induce inflammation, damage nephrons, and promote renal fibrosis, further exacerbating kidney malfunction [

29]. As antibiotics are known to disrupt microbial metabolism, measuring these metabolites in the serum of animals may provide insight into systemic effects of antibiotics and secondary metabolites as relating to GI functionality and integrity.

Overall, limited research is available on the effects of metronidazole on the fecal microbiota and metabolite profiles of cats. With previous research demonstrating prolonged consequences with antibiotic use, the objectives of this study were to evaluate the effects of metronidazole on the fecal microbiota and bacterial metabolites, as well as characterize the serum BA profile and uremic toxin concentrations of healthy adult cats. Based on past research, we hypothesized that metronidazole would drastically alter the fecal microbiota and fecal metabolite profiles, and influence serum metabolite concentrations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Diet, and Experimental Design

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to experimentation (IACUC #22028). Twelve healthy adult domestic shorthair cats (mean age = 4.7 ± 0.4 yr; mean body weight = 4.3 ± 0.8 kg) were used. All cats were housed in an environmentally-controlled facility at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Cats were group-housed, except for feeding times when all cats were individually housed to measure food offered and refused to calculate intake.

Cats had free access to fresh water at all times and were fed twice daily (8 am; 3 pm) at a rate to maintain body weight throughout the study. Cats were fed a standardized diet of Purina Cat Chow (Nestlé Purina PetCare Company, St. Louis, MO), which is formulated to meet all nutrient recommendations provided by the Association of American Feed Control Officials [

30] for adult cats at maintenance. Food offered and refused was measured each day to calculate intake and any observations of vomiting or negative reactions were recorded.

The experimental timeline is presented in

Supplementary Figure S1. The study was 42 days in length, with all cats consuming the basal diet for the duration. The study started with a 14-day baseline phase where all cats were adapted to the diet. After baseline (day 0), cats received metronidazole (Metronidazole Compounded Oil Liquid Chicken Flavored; Chewy, Inc.; Boston, MA) at a dosage of 20 mg/kg orally twice daily (at meal times) for 14 days. Cats were fed the basal diet for another 28 days to monitor recovery. Cats were weighed and body condition scores were assessed using a 9-point scale [

31] once a week prior to the morning feeding throughout the study.

2.2. Blood and Fecal Sample Collections and Analyses

At days 0, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42, overnight fasted blood samples were collected via jugular venipuncture. To collect blood, cats were sedated for at least 30 minutes with an intramuscular injection mix of Dexdomitor (dexmedetomidine; 0.02 mg/kg BW; Zoetis, Parsippany-Troy Hills, NJ) and Torbugesic (butorphanol tartrate; 0.4 mg/kg BW; Zoetis), and reversed using Antisedan (atipamezole hydrochloride; 0.2 mg/kg BW; Zoetis). Blood was collected into serum tubes containing a clot activator and gel for serum separation (BD Vacutainer SST Tubes #367986, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) for serum metabolite concentrations. Blood for serum isolation was centrifuged 1,800 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes (Beckman CS-6R Centrifuge; Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA).

On days 0, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42, fresh fecal samples were collected for the analysis of fecal score, pH, dry matter (DM) percentage, microbiota populations, and BA (conjugated and unconjugated forms), short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), branched-chain fatty acid (BCFA), phenol, indole, ammonia, and lactate concentrations. Fecal scores were recorded based on the following scale: 1 = hard, dry pellets, small hard mass; 2 = hard, formed, dry stool, remains firm and soft; 3 = soft, formed, and moist stool, retains shape; 4 = soft, unformed stool, assumes the shape of container; and 5 = watery, liquid that can be poured.

Fecal pH was measured immediately using an AP10 pH meter (Denver Instrument, Bohemia, NY) with a Beckman Electrode (Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, CA). After pH was measured, an aliquot was collected for DM determination in accordance to the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) [

32] using a 105°C oven. Two aliquots for phenol and indole measurement were frozen at -20°C until analysis. An aliquot collected for SCFA, BCFA, and ammonia analyses was diluted in a 1:1 ratio (w/v) of feces: 2 N HCl and frozen at −20°C until analysis. Other aliquots were collected into sterile cryogenic vials (Corning Inc., Corning, NY), immediately frozen in dry ice, and stored at −80°C until analysis for microbiota and BA.

Frozen fecal and serum samples were shipped on dry ice to the Texas A&M University Gastrointestinal Laboratory where they underwent further analysis.

2.2.1. Serum Uremic Toxin Analysis

A liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) assay was developed for measurement of serum uremic toxins based on previously published methods with modifications [

33]. The assay was analytically validated for use in dog and cat serum according to the FDA guidelines for bioanalytical method validation. Excess serum samples from dogs and cats submitted for routine diagnostic evaluation were used for the purposes of validation. Standard and internal standard stock solutions were prepared at 1 mg/mL methanol and stored at −20°C. A working solution of internal standards (312.5 ng/mL acetonitrile;

13C

6- indoxyl sulfate and d

7-p-cresol sulfate) was prepared fresh from stocks and stored at 4°C. Calibration curves consisted of 16 concentrations (1.22–40,000 ng/mL) and were prepared fresh by dilution of stocks into water.

Serum was extracted via the addition of 200 µL internal standard working solution to 100 µL serum. Samples were vortexed briefly and centrifuges at 16,000 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Samples were then diluted 1:1 in a new tube by the addition of 200 µL of 0.1% formic acid in water to 200 µL supernatant. Samples were then transferred to glass autosampler vial inserts and 5 µL injected for analysis.

The LC–MS/MS instrument consisted of an Infinity II Multisampler (maintained at 6°C) and a 1260 binary pump coupled to a 6470B triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with a jet stream electrospray ion source (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water and mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The flow was set to 0.4 mL/min and column temperature was maintained at 40°C. The analytical column was an Agilent InifinityLab Poroshell 120 Phenyl Hexyl 2.1 x 100 mm, 2.7 µm column. The mobile phase gradient started with 10% B and ramped to 32.5 % B from 0 to 3 minutes. The column was washed of high retaining compounds with 99% B from 3.1 to 4.7 minutes, and then re-equilibrated with 10% B from 4.8 to 6.2 minutes. The multiwash parameters and injection sequence added approximately 1 minute to the run time leading to an approximate time of 7.2 minutes from injection to injection. Only a portion of the sample (from 1 to 3 minutes) was sent to the MS with the remainder diverted to waste.

The analytes were measured in negative mode with dynamic multiple reaction monitoring. Precursor and product ions and fragment voltage and collision energies for each analyte are listed in

Supplemental File S1. The drying gas temperature was set to 250°C and flow at 9 L/min. The nebulizer was set to 40 psi and sheath gas temperature and flow to 350°C and 11 L/min, respectively. Capillary and nozzle voltages were 4,000 and 1,500 V. Data was processed in MassHunter Quant Analysis Software v.10.0 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

2.2.2. Fecal SCFA, BCFA, Ammonia, Phenol, and Indole Analyses

Samples used for SCFA and BCFA analysis were determined by gas chromatography according to Erwin et al. [

34] using a gas chromatograph (Hewlett-Packard 5890A series II, Palo Alto, CA) coupled to a flame ionization detector. The gas chromatograph was fitted with a glass column (180 cm x 4 mm i.d.) packed with 10% SP-1200/1% H

3PO

4 on 80/100+ mesh Chromosorb WAW (Supelco Inc., Bellefonte, PA). Nitrogen was the carrier gas with a flow rate of 75 mL/min. Oven, detector, and injector temperatures were 125, 175, and 180°C, respectively. Fecal ammonia concentrations were determined according to the method of Chaney and Marbach [

35]. Fecal phenol (phenol, 4-methylphenol, 4-ethylphenol) and indole (indole, 7-methylindole, 3-methylindole, 2,3-dimethylindole) concentrations were determined using gas chromatography according to the methods described by Flickinger et al. [

36].

2.2.3. Fecal Lactate Analysis

The fecal D-, L-, and total lactate concentrations were measured by utilizing the protocol described by Blake et al. [

18]. Briefly, an aliquot of 120–130 mg feces was mixed with 750 μL of 0.1 M triethanolamine buffer (pH 9.15) and thoroughly vortexed. The mixture was then centrifuged at 13,000 ×

g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Following this, 495 μL of the supernatant was deproteinized with 10 μL of 6 M trichloroacetic acid, vortexed again, and kept on ice for 20 minutes. The sample was further centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Subsequently, 400 μL of the supernatant was diluted with 1,600 μL of 0.1 M triethanolamine buffer (pH 9.15) to neutralize the pH (adjusted between 7 and 10). The processed fecal extract was then analyzed using a D-/L-Lactate Enzymatic Kit (R-Biopharm Inc., Darmstadt, Germany) in a 96-well plate format, following a modified version of the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.2.4. Fecal and Serum BA Analyses

Bie acids were measured using an in-house validated LC-MS/MS method. Briefly, an aliquot of 100 mg feces was extracted with the addition of 300 µL methanol and 40 µL internal standard working solution (d4-glycocholic acid and d4-glycolithocholic acid). Samples were placed on a bead beater for 2 minutes and then centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged again at 10,000 x g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was then transferred to an autosampler vial and 3 µL injected onto an LC-MS/MS. A diluted sample was also injected after combining 5 µL of the supernatant and 295 µL methanol. Concentrations were calculated from the diluted sample for high concentration BA and from the undiluted sample for low concentration BA.

Serum BA analysis was performed with a modified sample preparation protocol that was developed and cross validated for this study. Briefly, 200 µL serum was combined with 560 µL methanol and 40 µL internal standard mixture in methanol (d4-glycocholic acid and d4-glycolithocholic acid) vortexed and centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was transferred to a glass tube and dried under a continuous stream of nitrogen on a heating block set to 65°C for approximately 20 minutes or until dry. Samples were reconstituted in 75 µL methanol, transferred to autosampler vials and 5 µL injected.

2.2.5. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) and Dysbiosis Index (DI) Analysis

qPCR analysis of select bacterial taxa was performed with specific primers targeting

Bacteroides,

Blautia,

Bifidobacterium,

P. hiranonis,

Escherichia coli,

Faecalibacterium,

Fusobacterium,

Streptococcus,

Turicibacter, and universal bacteria as described in Sung et al. [

5]. Briefly, the conditions for qPCR were as follows: initial denaturation at 98°C for 2 minutes, then 35 cycles with denaturation at 98°C for 3 seconds, and annealing for 3 seconds. Melt curve analysis was performed to validate the specific generation of the qPCR product using these conditions: 60°C to 90°C with an increase of 0.5°C for 5 seconds. Each reaction was run in duplicate. The qPCR data were expressed as the log amount of DNA (fg) for each bacterial group per 10 ng of isolated total DNA as reported previously [

37,

38]. The degree of dysbiosis is represented as a single numerical value that measures the closeness of a taxa compared to the mean abundances derived from healthy and diseased populations and is calculated by a Euclidean distance model, as detailed in Sung et al. [

5]. Using this DI system, a score less than zero is considered healthy and “normal”, while any score greater than 1 denotes dysbiosis. A DI of 0–1 represents an equivocal outcome.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10.4 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) and are displayed in figures. If normality standard under the Gaussian distribution or Shapiro-Wilk test statistic were met, the repeated measures one-way ANOVA model was used to compare time points. All means were compared to day 0 with significance denoted as the following: (*: P<0.05; **: P<0.01; ***: P<0.001; ****: P<0.0001). If data did not meet normality assumptions, the Freidman test was utilized. Simple linear regression was performed to assess the relationship between Bifidobacterium or pH and fecal D-, L-, and total lactate, with 95% confidence intervals shown. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 and trends were reported if P<0.10.

4. Discussion

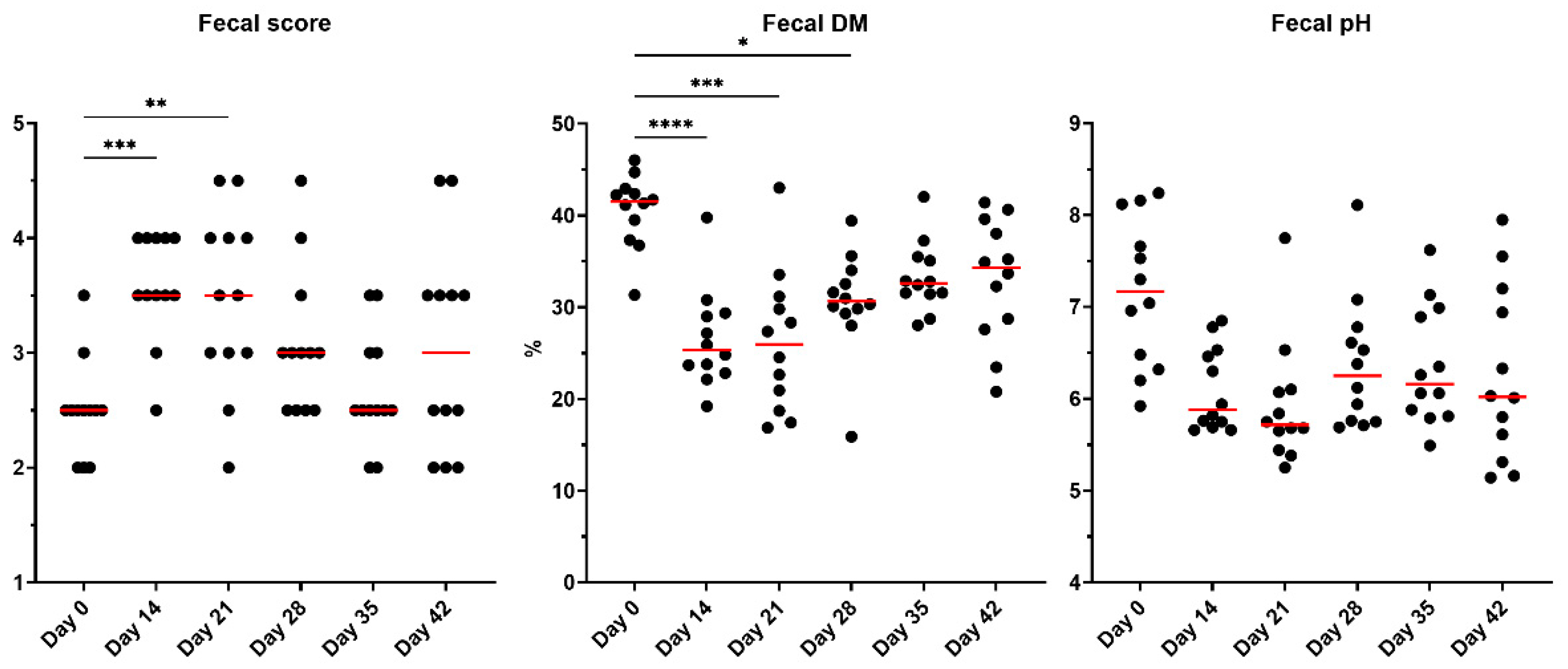

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of metronidazole administration on the fecal microbiota, fecal metabolites, and serum BA and uremic toxins of healthy adult cats. Metronidazole was administered at a dose similar to what is prescribed in an outpatient setting for cats with giardia. Metronidazole caused dysbiosis and significantly impacted stool quality, moisture content, and metabolite concentrations. Metronidazole induced prolonged dysbiosis and disrupted microbial metabolism in the majority of animals, even when monitored up to 28 days following cessation.

Diarrhea is not a commonly reported side effect of metronidazole administration in cats but the usage of antibiotics has previously been reported to loosen stools of animals undergoing treatment [

21,

22,

23], and metronidazole is commonly prescribed to treat acute diarrhea in cats. In the current study, stools were loosened during and 7 days after metronidazole administration. Additionally, 50% (6/12) of cats had persistent looser stools and less than ideal fecal scores (≥3.5) by the end of the study. Fecal scores varied greatly by animal, demonstrating highly individualized responses. Concurrently, fecal DM percentages were reduced (higher stool moisture) and fecal pH was numerically lower, indicating physiological changes induced in the GI tract. The GI tract environment (i.e., oxygen concentrations, pH measurements) varies and can influence the presence and abundance of microbes present. An alteration in pH stability may influence bacterial growth of pH-sensitive bacteria (e.g., low pH inhibits growth of

Streptococcus and

Veillonella) or cause metabolic disruption and production of SCFA [

39]. Additionally, lactic acid bacteria thrive in more acidic conditions and may explain the sustained increase observed in

Bifidobacterium abundances in the present study. While

Bifidobacterium remained within the reference interval for the entirety of the study, it is known to increase following metronidazole treatment and in a chronic GI disease state, thereby potentiating overgrowth of other lactic acid bacteria (i.e.,

Lactobacillus, Streptococcus) [

18,

22,

27]. The pH of a fecal sample may provide insight into microbial activity (i.e., fermentation, BA transformations) and has been shown to reduce in cats treated with metronidazole [

22]; however, fecal pH does not represent the full microbial activity occurring in more proximal areas of the GI and can be a limitation for interpretation.

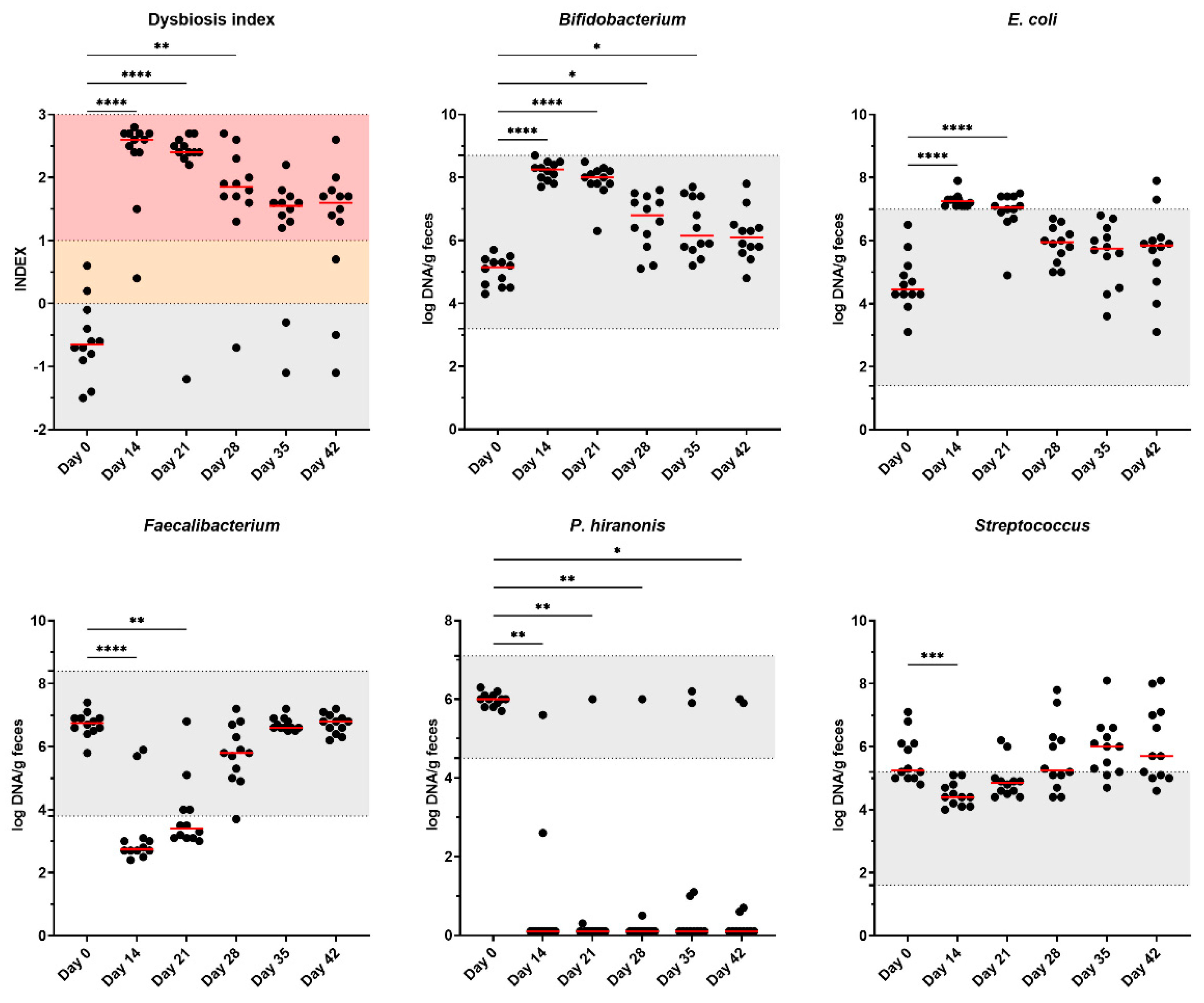

Metronidazole altered the overall microbiota composition, including an increased DI and changes to several bacterial taxa. Increased DI is commonly reported following antibiotic treatment and in cases of chronic GI diseases [

5,

20,

23,

24,

25,

40]. Changes in microbial profiles may be initiated or altered by several factors (i.e., diet change, environmental stressors, medications) but the extent of these changes differs, with antibiotics and chronic intestinal disease typically leading to more severe dysbiosis. Continued dysbiosis was observed in 83% (10/12) of cats in the current study. Following metronidazole administration, the bacterial community failed to return to baseline composition and may be potentially a risk factor for long-term health consequences [

41]. The present study did not permit continued sampling further than 4 weeks to monitor follow-up of these animals and is considered to be a limitation to this research. Based on the results presented here, antibiotic-treated cats should be monitored for a longer time period in future studies.

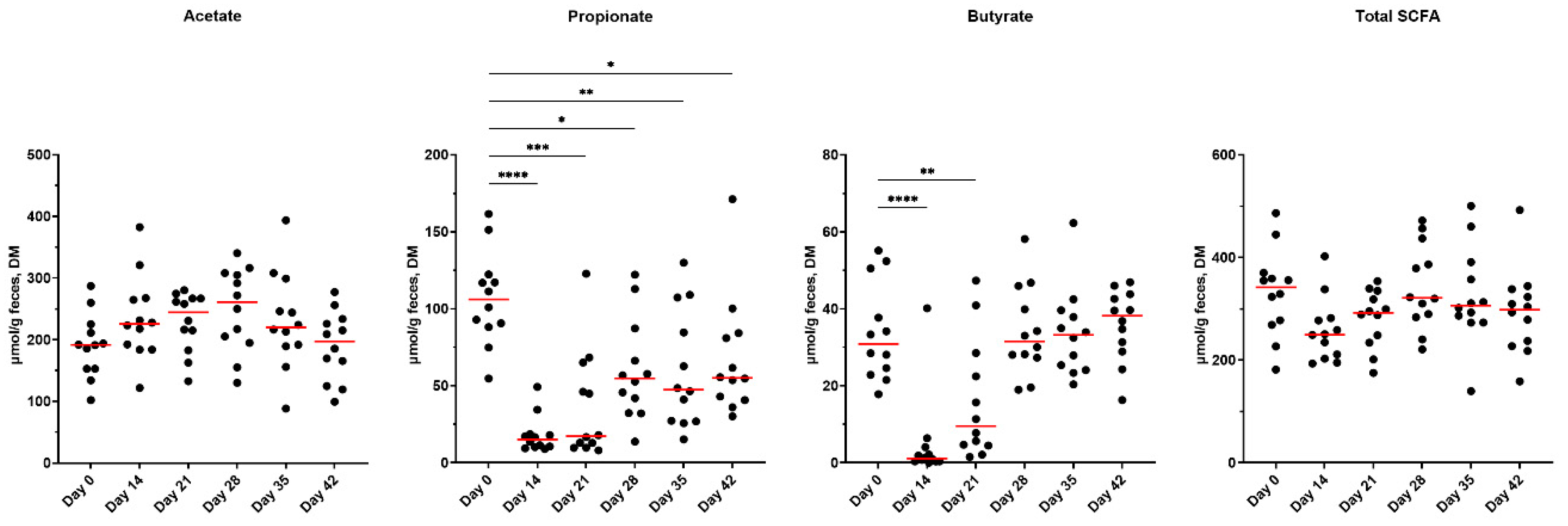

The SCFA producers,

Blautia, Faecalibacterium, and

Turicibacter, were reduced after metronidazole administration [

1,

27,

42]. Reductions were not observed beyond a two-week recovery period. Several cats fell below the reference range for

Faecalibacterium immediately after metronidazole (10/12) and one-week post-cessation (8/12). These bacterial taxa are important for host health, as they utilize any undigested food products from the host, producing SCFA that can serve as an energy source for the host colonocytes as well as reducing luminal pH to discourage pathogenic bacterial growth and increasing intestinal barrier integrity by stimulating goblet cells, increasing tight junction proteins and antimicrobial peptide expression [

43,

44,

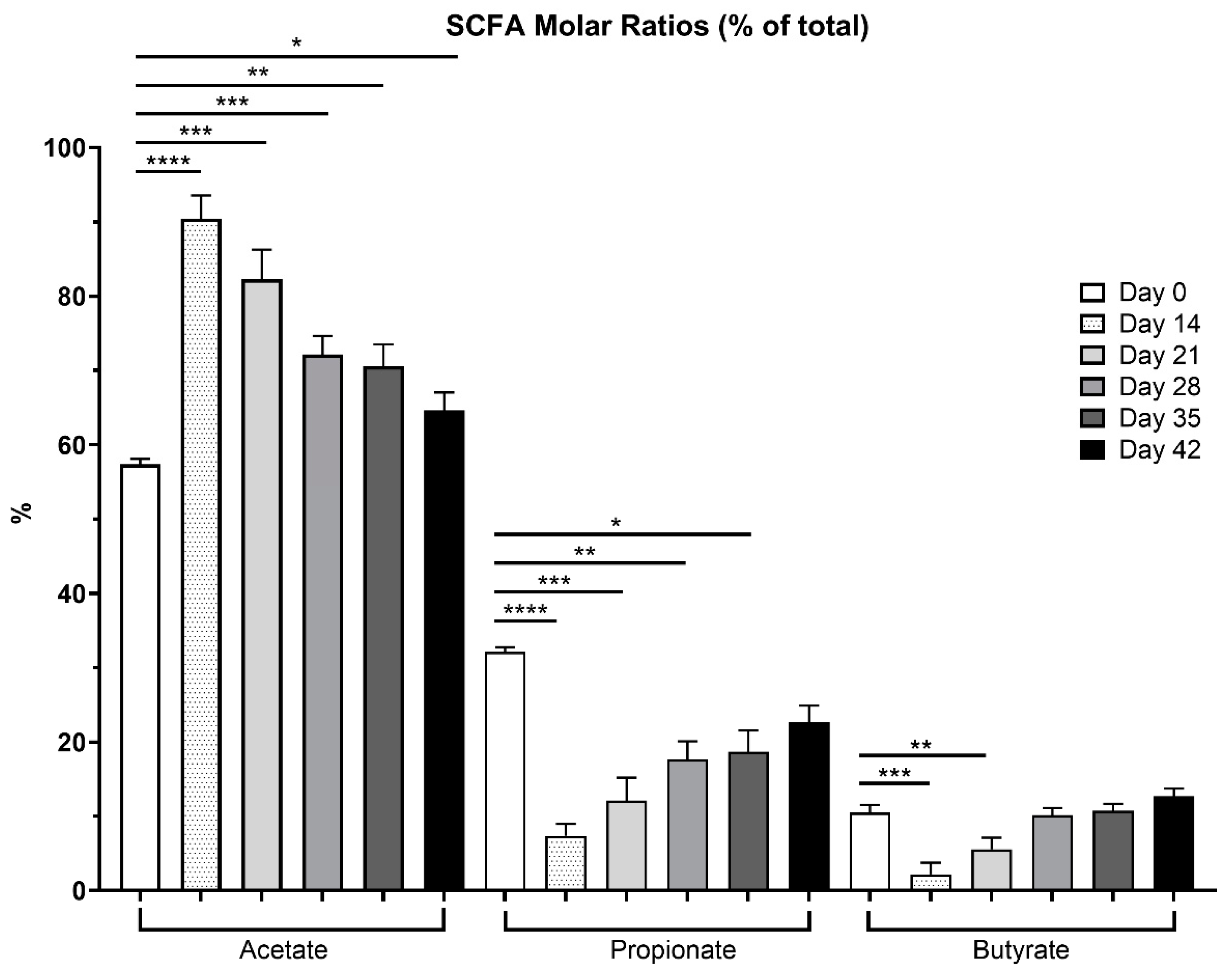

45]. However, luminal pH was not measured in the present study. Total SCFA concentrations tended to be reduced, and propionate and butyrate concentrations were reduced with metronidazole, demonstrating an impairment in the fermentation pattern, consistent with a previous

in vitro fermentation study evaluating fiber fermentation patterns in dogs treated with metronidazole [

46]. When evaluated as ratios, there were higher concentrations of acetate (90.4%) compared to propionate (7.4%) and butyrate (2.2%), immediately following metronidazole. Only with time did these ratios improve as fermentation capability was restored with microbial recovery (i.e.,

Faecalibacterium,

Blautia, Bacteroides), ending with 64.5% (acetate), 22.6% (propionate), and 12.7% (butyrate) ratios. As a potential treatment plan in cases of CE, dietary intervention by inclusion of functional ingredients, such as dietary fiber, may aid in microbial recovery and restoration of SCFA production.

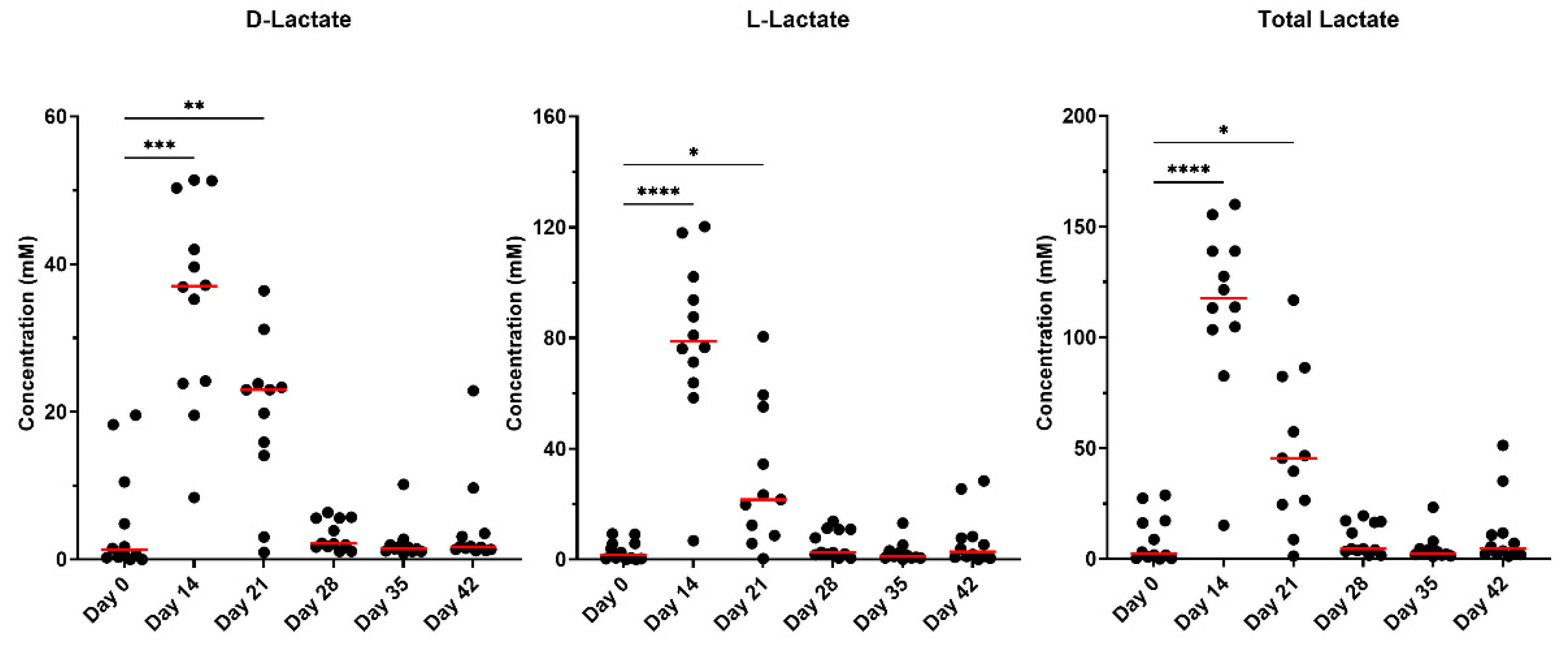

While the major byproducts of carbohydrate fermentation (i.e., SCFA) were measured, lactate is another byproduct produced by anaerobic bacteria but is produced in lower levels in comparison. In cases of over-production or rapid fermentation, lactate can lower the pH and sustain the growth of other lactic acid bacteria (i.e.,

Bifidobacterium), as previously mentioned [

18,

27]. Some species of bacteria are able to metabolize lactate and can be present as one of two isomers (L-lactate or D-lactate). The D-isomer is considered to be a neurotoxin in high and sustained concentrations if it enters into systemic circulation [

47]. Concentrations in the present study were not sustained beyond day 21 but strong correlations were associated with D-lactate and

Bifidobacterium abundances.

E. coli and

Streptococcus are associated with overgrowth in dysbiosis, and known to increase after antibiotic treatment [

14,

22,

48]. Furthermore,

E. coli is known as a potentially pro-inflammatory pathobiont. Interestingly,

Streptococcus in the present study demonstrated the opposite effect and decreased after metronidazole administration, but recovered after metronidazole was ceased. While it was not explored in the present study, this result was not anticipated.

Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and

Peptacetobacter (Clostridium) genera are among the many commensal bacteria with the ability to deconjugate BA via a bile salt hydrolase enzyme as the first step to allow for further secondary BA production and therefore, are paramount in microbial metabolism [

49,

50,

51]. Data previously reported in mammals after using broad-spectrum antibiotics (metronidazole, vancomycin) demonstrated an increase in conjugated BA, likely attributed to the reduction of the commensal bacteria with hydrolase activity [

52]. In the present study, the majority of the secondary BA were present in unconjugated forms in the serum samples following metronidazole and remained consistent for the study duration. The 7α-dehydroxylation process converts primary BA CA and CDCA into their secondary BA forms DCA and LCA, respectively.

P. hiranonis is the main species capable of performing this transformation in dogs and cats via 7α-dehydroxylation enzymes produced by the

bai gene [

26]. This species was largely absent in several cats during recovery and only achieved normal abundances in 16% (2/12) of cats by the end of the recovery period. Despite all cats falling within the established reference interval at day 0, this taxa failed to recover in the majority of cats. The abundance of secondary BA was significantly reduced with metronidazole, further demonstrating the vital role of

P. hiranonis in BA biotransformation.

In this study, only two cats had normal

P. hiranonis and BA conversion at the end of the recovery period. Highlighted in

Supplementary Figure S19, Cat 1 (green) appeared to be fully resistant to metronidazole administration as this individual retained

P. hiranonis and normal BA conversions for the entire study period, and Cat 2 (red) showed recovery after three weeks at day 35. Serum BA in Cat 1 also were the highest compared to others immediately following metronidazole. All remaining cats were unable to recover to initial measures, demonstrating persistent effects of metronidazole. Additionally, Cat 1 had the lowest concentrations of lactate for all time points, except at baseline, and remained largely unaffected compared to others, as the DI remained normal, indicating less severe shifts in the overall microbiome composition. This could suggest that individual strains of

P. hiranonis may be resistant to metronidazole effects.

Initially studied in humans, intestinal dysbiosis in patients with chronic kidney disease was associated with increased production of uremic toxins and was recently reported to be similar in cats [

29,

53]. PS was not reported to be different but increased IS was observed in cats with advancing kidney disease and muscle atrophy [

29,

53]. In the present study, both uremic toxins were reduced with metronidazole; however, only PS was immediately influenced by metronidazole and IS reductions were not observed until day 21 and day 42. While the animals used in this study were clinically healthy, the impairment of uremic toxin production demonstrates that metronidazole has more systemic effects beyond microbial alterations than typically reported.

There are a couple of limitations to address in the present study. First, the animals used were clinically healthy and had no reported history of antibiotics. While it is beneficial to understand the effects of metronidazole in healthy animals, patterns observed in clinically diseased animals may be different, thereby limiting the application of this data to chronic disease and microbial alterations. Second, the time allotted for monitoring may have been too short to observe a complete recovery of parameters, including DI, P. hiranonis, and BA metabolism. By the end of the study, these measures had not fully recovered and longer duration studies are needed to ascertain how much time is needed to achieve recovery without medical intervention (i.e., fecal microbial transplants). Future studies addressing these limitations would likely provide additional insight into further recommendations regarding metronidazole administration.

Figure 1.

Fecal scores, DM percentages, and pH of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians. Ideal fecal scores are considered to be between 2.5 and 3.0.

Figure 1.

Fecal scores, DM percentages, and pH of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians. Ideal fecal scores are considered to be between 2.5 and 3.0.

Figure 2.

Fecal SCFA concentrations of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.

Figure 2.

Fecal SCFA concentrations of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.

Figure 3.

Overall SCFA percentages presented in fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). Ratios drastically varied across time points, with samples collected immediately after metronidazole having the highest acetate proportions (day 14), propionate was greatest prior to antibiotics, whereas butyrate proportions were highest at the end of the study.

Figure 3.

Overall SCFA percentages presented in fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). Ratios drastically varied across time points, with samples collected immediately after metronidazole having the highest acetate proportions (day 14), propionate was greatest prior to antibiotics, whereas butyrate proportions were highest at the end of the study.

Figure 4.

Fecal lactate concentrations of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.

Figure 4.

Fecal lactate concentrations of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.

Figure 5.

Fecal BA concentrations (unconjugated and conjugated forms) of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.

Figure 5.

Fecal BA concentrations (unconjugated and conjugated forms) of fresh fecal samples collected from healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.

Figure 6.

Dysbiosis index and fecal microbiota abundances of healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared with day 0, with red lines representing medians. Reference intervals for cats are highlighted in grey. A dysbiosis index score less than zero (grey area) is considered healthy and “normal,” whereas a score >1 (pink) denotes extreme dysbiosis. A dysbiosis index from zero to one (yellow) is indicative of a mild to moderate shift in the overall diversity.

Figure 6.

Dysbiosis index and fecal microbiota abundances of healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared with day 0, with red lines representing medians. Reference intervals for cats are highlighted in grey. A dysbiosis index score less than zero (grey area) is considered healthy and “normal,” whereas a score >1 (pink) denotes extreme dysbiosis. A dysbiosis index from zero to one (yellow) is indicative of a mild to moderate shift in the overall diversity.

Figure 7.

Serum indoxyl sulfate (IS) and p-cresol sulfate (PCS) concentrations of healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.

Figure 7.

Serum indoxyl sulfate (IS) and p-cresol sulfate (PCS) concentrations of healthy adult cats before metronidazole (day 0), after metronidazole administration (day 14), and during recovery (day 15-42). The mean of each time point was compared to day 0, with red lines representing medians.