Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Marbofloxacin with or Without NAC

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity of Marbofloxacin with or Without NAC

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Drugs and Reagents

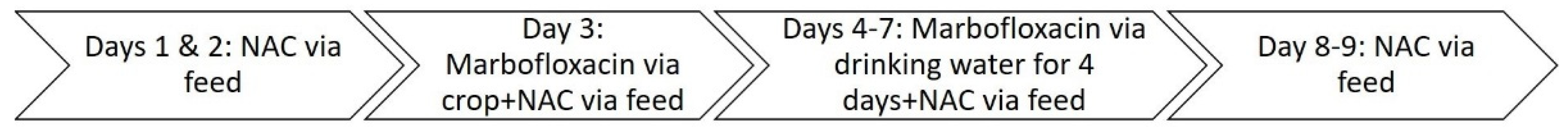

Animals and Experimental Design

Determination of Marbofloxacin Concentrations by LC-MS/MS Analysis

Protein Binding

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Determination of MIC and MBC Values

Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAC | N-acetyl-L-cysteine |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

References

- Martinez M., McDermott P., Walker R. Pharmacology of the fluoroquinolones: a perspective for the use in domestic animals. Vet J. 2006, 172, 10-28. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.D., Vaghela, S.H., Tukra, S., Patel, A.R., Patel, H.B., Sarvaiya, V.N., Mody, S. K. (). Dosage derivation of marbofloxacin in broiler chickens based on pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic integration. Indian J. Vet. Sci. & Biotechnol., 2023, 19, 7-11. [CrossRef]

- Atef M., Atta A. H., Darwish A. S., Mohamed H. Pharmacokinetics aspects and tissue residues of marbofloxacin in healthy and Mycoplasma gallisepticum-infected chickens. Wulfenia, 2017, 24, 80-107.

- Urzúa Pizarro N.F., Errecalde C.A., Prieto G.F., Lüders C.F., Tonini M.P., Picco E.J. Pharmacokinetic behavior of marbofloxacin in plasma from chickens at different seasons. Mac Vet Rev, 2017, 40, 143-147. [CrossRef]

- Vaghela S.H., Singh R.D., Tukra S., Patel A.R., Patel H.B., Sarvaiya V.N., Mody S.K. Disposition kinetic behaviour of marbofloxacin in broiler chickens. Pharm Innov J, 2022, 11, 2223-2226.

- Haritova A.M., Rusenova N.V., Parvanov P.R., Lashev L.D., Fink-Gremmels J. Integration of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic indices of marbofloxacin in turkeys. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2006, 50, 3779-3785. [CrossRef]

- Lashev L.D., Dimitrova D.J., Milanova A., Moutafchieva R.G. Pharmacokinetics of enrofloxacin and marbofloxacin in Japanese quails and common pheasants. Br Poult Sci, 2015, 56, 255-261. [CrossRef]

- Abo-EL-Sooud K., Swielim G.A., EL-Gammal S.M., Ramsis M.N. Comparative Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of marbofloxacin in geese (Anser Anser domesticus) after two sites of intramuscular administrations. J vet Pharmacol Therap, 2020, 43, 313-318. [CrossRef]

- Sartini I., Łebkowska-Wieruszewska B., Lisowski A., Poapolathep A., Owen H., Giorgi M. Concentrations in plasma and selected tissues of marbofloxacin after oral and intravenous administration in Bilgorajska geese (Anser anser domesticus). N Zeal Vet J, 2020, 68, 31-37. [CrossRef]

- OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health), 2019. OIE list of antimicrobial agents of veterinary importance. https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Our_scientific_ex pertise/docs/pdf/AMR/A_OIE_List_antimicrobials_July2019.pdf. Last assessed March 5, 2025.

- Soh H.Y., Tan P.X.Y., Ng T.T.M., Chng H.T., Xie S. A critical review of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety data of antibiotics in avian species. Antibiotics, 2022, 11, 741. [CrossRef]

- Roth N., Käsbohrer A., Mayrhofer S., Zitz U., Hofacre C., Domig K.J. The application of antibiotics in broiler production and the resulting antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli: A global overview. Poult Sci, 2019, 98, 1791–1804. [CrossRef]

- Prandi I., Bellato A., Nebbia P., Stella M.C., Ala U., von Degerfeld M.M., Quaranta G., Robino P. Antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli in wild birds hospitalised in a wildlife rescue centre. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis, 2023, 93, 101945. [CrossRef]

- Shaheen R., El-Abasy M., El-Sharkawy H., Ismail M.M. Prevalence, molecular characterization, and antimicrobial resistance among Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from Egyptian broiler chicken flocks with omphalitis. Open Vet J, 2024, 14, 284–291. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency, 2020. Committee for Medicinal Products for Veterinary use (CVMP). EMA/CVMP/CHMP/682198/2017. Categorisation of Antibiotics in the European Union. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/categorisation-antibiotics-european-union-answer-request-european-commission-updating-scientific-advice-impact-public-health-and-animal-health-use-antibiotics-animals_en.pdf. Last assessed March 6, 2025.

- de Mesquita Souza Saraiva M., Lim K., do Monte D.F.M., Givisiez P.E.N., Alves L.B.R., de Freitas Neto O.C., Gebreyes W.A. (). Antimicrobial resistance in the globalized food chain: A One Health perspective applied to the poultry industry. Braz J Microbiol, 2022, 53, 465-486. DOI: 10.1007/s42770-021-00635-8.

- Worthington R.J., Melander C. Combination approaches to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria. Trends in biotechnology. 2013, 31, 177-184. [CrossRef]

- Pinto R.M., Soares F.A., Reis S., Nunes C., Van Dijck P. Innovative strategies toward the disassembly of the EPS matrix in bacterial biofilms. Front Microbiol, 2020, 11, 952. [CrossRef]

- Shariati A., Kashi M., Chegini Z., Hosseini S.M. Antibiotics-free compounds for managing carbapenem-resistant bacteria; a narrative review. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 17, 15:1467086. [CrossRef]

- Yi D., Hou Y., Tan L., Liao M., Xie J., Wang L., Ding B., Yang Y., Gong J. N-acetylcysteine improves the growth performance and intestinal function in the heat-stressed broilers. Anim Feed Sci Tech, 2016, 220, 83-92. [CrossRef]

- Mishra B., Jha R. Oxidative stress in the poultry gut: Potential challenges and interventions. Front Vet Sci, 2019, 6, 60. https:// doi. org/ 10. 3389/ fvets. 2019. 00060.

- Allam A., Abdeen A., Devkota H.P., Ibrahim S.S., Youssef G., Soliman A., Abdel-Daim M.M., Alzahrani K.J., Shoghy K., Ibrahim S.F., Aboubakr M. (). N-acetylcysteine alleviated the deltamethrin-induced oxidative cascade and apoptosis in liver and kidney tissues. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022, 19, 638. [CrossRef]

- Wang L., Xu Y., Zhao X., Zhu X., He X., Sun A., Zhuang G. Antagonistic effects of N-acetylcysteine on lead-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress in chicken embryo fibroblast cells. Heliyon, 2023, e21847. [CrossRef]

- Blasi F., Page C., Rossolini G.M., Pallecchi L., Matera M.G., Rogliani P., Cazzola M. The effect of N-acetylcysteine on biofilms: Implications for the treatment of respiratory tract infections. Respir Med, 2016, 117, 190-197. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rosado A.I., Valencia E.Y., Rodríguez-Rojas A., Costas C., Galhardo R.S., Rodríguez-Beltrán J., Blázquez J. N-acetylcysteine blocks SOS induction and mutagenesis produced by fluoroquinolones in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2019, 74, 2188-2196. [CrossRef]

- Hamed S., Emara M., Tohidifar P., Rao C.V. N-Acetyl cysteine exhibits antimicrobial and anti-virulence activity against Salmonella enterica. PLoS One, 2025, 20, e0313508. [CrossRef]

- Goswami M., Jawali N. N-acetylcysteine-mediated modulation of bacterial antibiotic susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2010, 54, 3529–3530. [CrossRef]

- Landini G., Di Maggio T., Sergio F., Docquier J.D., Rossolini G.M. Pallecchi L. Effect of high N-acetylcysteine concentrations on antibiotic activity against a large collection of respiratory pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2016, 60, 7513-7517. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis M., Mascellino M.T., Miele M.C., Al Ismail D., Colone M., Stringaro A., Vullo V., Venditti M., Mastroianni C. M., Oliva A. High Activity of N-Acetylcysteine in Combination with Beta-Lactams against Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics, 2022, 11, 225. [CrossRef]

- Petkova T., Rusenova N., Danova S., Milanova A. Effect of N-Acetyl-L-cysteine on Activity of Doxycycline against Biofilm-Forming Bacterial Strains. Antibiotics. 2023, 12, 1187. [CrossRef]

- Valdivia A.G., Martinez A., Damian F.J., Quezada T., Ortiz R., Martinez C., Llamas J., Rodríguez M.L., Yamamoto L., Jaramillo F., Loarca-Piña M.G., Reyes, J.L. Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine to reduce the effects of aflatoxin B1 intoxication in broiler chickens. Poult Sci, 2001, 80(6), 727-734. [CrossRef]

- Patel A.R., Patel H.B., Sarvaiya V.N., Singh R.D., Patel H.A., Vaghela S.H., Tukra S., Mody S.K. Pharmacokinetic profile of marbofloxacin following oral administration in broiler chickens. Pharm Innov, 2022, 11, 22-25.

- Patel H.B., Patel U.D., Modi C.M., Bhadarka, D.H. Pharmacokinetics of Marbofloxacin Following Single and Repeated Dose Intravenous Administration in Broiler Chickens. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci, 2018, 7, 2344-2351. [CrossRef]

- Patel H.B., Patel U.D., Modi C.M., Ahmed S., Solanki, S. L. Pharmacokinetic profiles of marbofloxacin following single and repeated oral administration in broiler chickens. Annals of Phytomedicine, 2018, 7, 174-179. DOI: 10.21276/ap.2018.7.2.26.

- Yang F., Yang Y.R., Wang L., Huang X.H., Qiao G., Zeng Z.L. Estimating marbofloxacin withdrawal time in broiler chickens using a population physiologically based pharmacokinetics model. J Vet Pharmacol Ther, 2014, 37, 579-588. [CrossRef]

- Toutain P.L., Bousquet-mélou A. Plasma terminal half-life. J Vet Pharmacol Ther, 2004, 27, 427-439. [CrossRef]

- Kłosińska-Szmurło E., Pluciński F.A., Grudzień M., Betlejewska-Kielak K., Biernacka J., Mazurek A. (). Experimental and theoretical studies on the molecular properties of ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, pefloxacin, sparfloxacin, and gatifloxacin in determining bioavailability. J Biol Phys, 2014, 40, 335-345. [CrossRef]

- Li X., Kim J., Wu J., Ahamed A. I., Wang Y., Martins-Green M. N-Acetyl-cysteine and Mechanisms Involved in Resolution of Chronic Wound Biofilm. J Diabetes Res, 2020, 9589507. [CrossRef]

- Patel A., Patel H.B., Sarvaiya V.N., Singh, R.D., Patel H.A., Vaghela S., Tukra S., Mody S. K. Pharmacokinetics of marbofloxacin following oral administration in lactic acid pretreated broiler chickens. Asian J Dairy Food Res, 2023, DR-2046, 1-6. DOI: 10.18805/ajdfr.DR-2046.

- Roydeva A., Beleva G., Gadzhakov D., Milanova A. Pharmacokinetics of N-acetyl-l-cysteine in chickens. J Vet Pharmacol Ther, 2024, 47, 403-415. [CrossRef]

- Aslam S., Trautner B.W., Ramanathan V., Darouiche R.O. (). Combination of tigecycline and N-acetylcysteine reduces biofilm-embedded bacteria on vascular catheters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2007, 51, 1556-1558. [CrossRef]

- Attili A., Cerquetella M., Pampurini F., Laus F., Spaterna A., Cuteri V. Association between enrofloxacin and N-acetylcysteine in recurrent bronchopneumopathies in dogs caused by biofilm producer bacteria. J Anim Vet Adv, 2012, 11, 462-469. [CrossRef]

- Sun J.-L., Liu C., Song Y. Screening 36 veterinary drugs in animal origin food by LC/MS/MS combined with modified QuEChERS method. 2012, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/applications/5991-0013EN.pdf. Last accessed March 06, 2025.

- Barre J., Chamouard J.M., Houin, G., Tillement J.P. Equilibrium dialysis, ultrafiltration, and ultracentrifugation compared for determining the plasma-protein-binding characteristics of valproic acid. Clin Chem, 1985, 31, 60–64.

| Parameters (unit) |

Marbofloxacin | Marbofloxacin + N-acetylcystein | |||

| i.v. | p.o. into the crop | p.o. into the crop | p.o. multiple administration | ||

| λ (1/h) | 0.174 (0.159-0.199) | 0.17 (0.114-0.252) | 0.213 (0.111-0.316)* | 0.084 (0.046-0.179)*,▲,■ | |

| t1/2el (h) | 3.98 (3.48-4.35) | 3.99 (2.75-6.10) | 3.13 (2.20-6.22) | 8.26 (3.87-15.02)*,▲,■ | |

| Tmax (h) | - | 1.99 (1.0-6.0) | 1.97 (1.0-8.0) | - | |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | - | 3.10 (1.95-5.01) | 2.0 (1.03-2.82)▲ | - | |

| Cavg (μg/mL) | - | - | - | 0.41 (0.26-0.81) | |

| AUC0-∞ (μg×h/mL) | 33.02 (24.54-42.96) | 23.99 (19.47-31.02)* | 12.22 (8.35-15.62)*,▲ | - | |

| AUC0-τ (μg×h/mL) | - | - | - | 9.09 (6.0-17.95) | |

| AUCextrap (%) | 0.67 (0.23-2.19) | 0.59 (0.16-2.26) | 3.85 (0.65-18.68) | - | |

| CL(mL/h/kg) | 151.45 (116.4-203.76) | - | - | - | |

| Vss (L/kg) | 0.753 (0.624-0.955) | - | - | - | |

| Vz (L/kg) | 0.872 (0.662-1.118) | - | - | - | |

| MRT (h) | 4.98 (3.25-6.12) | 6.67 (5.50-7.83)* | 5.49 (3.91-9.33) | - | |

| MAT (h) | - | 1.53 (0.68-3.07) | 0.44 (0.05-3.44)▲ | - | |

| F (%) | - | 72.66 (50.84-106.47) | 37.0 (19.45-63.65)▲ | ||

| Bacterial strain |

Marbofloxacin (μg/mL) |

MIC of marbofloxacin + N-acetyl-L-cysteine (μg/mL) |

||||||

| MIC | MBC | NAC 20 μg/ml |

NAC 6 μg/ml |

NAC 4 μg/ml |

NAC 2 μg/ml |

NAC 1 μg/ml |

||

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 | 0.0039 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).