Submitted:

17 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

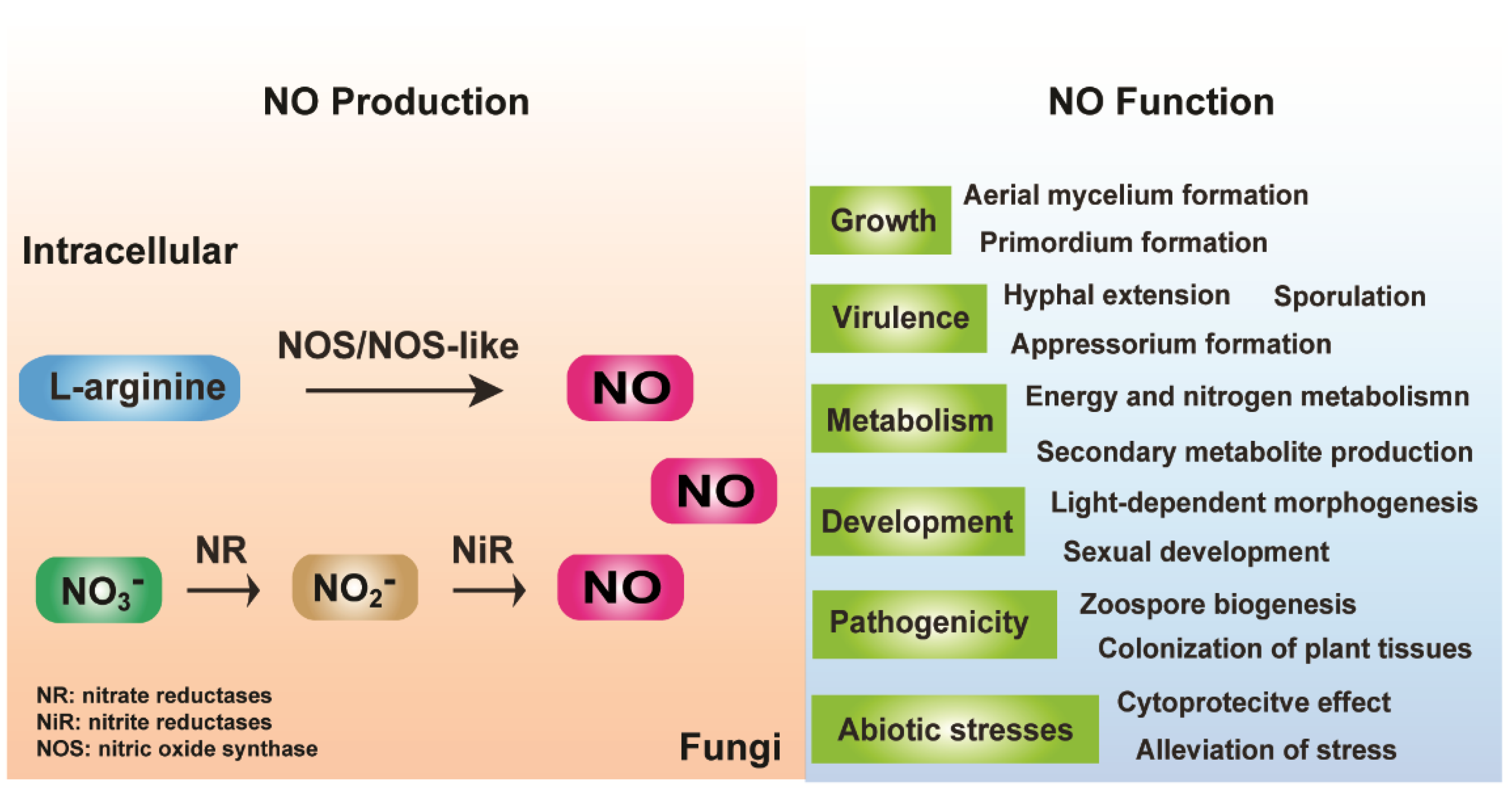

2. Fungal Endogenous NO Production

2.1. Arginine-Dependent NO Formation

2.2. Nitrite (NO2-)-Dependent NO Formation

3. Function of Endogenous NO and NO Signaling in Fungi

3.1. Growth and Development Regulation

3.2. Response to Stressors

3.3. Metabolism Regulation

3.4. Virulence and Pathogenicity

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lamattina, L.; Garcia-Mata, C.; Graziano, M.; Pagnussat, G. Nitric oxide: the versatility of an extensive signal molecule. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2003, 54, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cánovas, D.; Marcos, J.F.; Marcos, A.T.; Strauss, J. Nitric oxide in fungi: is there NO light at the end of the tunnel? Curr Genet 2016, 62, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ali, S.; Al Azzawi, T.N.I.; Yun, B.W. Nitric oxide acts as a key signaling molecule in plant development under stressful conditions. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredt, D.S. Endogenous nitric oxide synthesis: biological functions and pathophysiology. Free Radic Res 1999, 31, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Dempsey, S.K.; Daneva, Z.; Azam, M.; Li, N.; Li, P.L.; Ritter, J.K. Role of nitric oxide in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esplugues, J.V. NO as a signalling molecule in the nervous system. Br J Pharmacol 2002, 135, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.; Munari, F.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, R.; Scolaro, T.; Castegna, A. The metabolic signature of macrophage responses. Front immunol 2019, 10, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y. The regulatory role of nitric oxide in proinflammatory cytokine expression during the induction and resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 2010, 88, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S.J.; Desikan, R.; Hancock, J.T. Nitric oxide signalling in plants. New Phytol 2003, 159, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palavan-Unsal, N.; Arisan, D. Nitric oxide signalling in plants. Bot Rev 2009, 75, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.T. Nitric oxide signaling in plants. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arc, E.; Galland, M.; Godin, B.; Cueff, G.; Rajjou, L. Nitric oxide implication in the control of seed dormancy and germination. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Aragunde, N.; Graziano, M.; Lamattina, L. Nitric oxide plays a central role in determining lateral root development in tomato. Planta 2004, 218, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, M.C.; Graziano, M.; Polacco, J.C.; Lamattina, L. Nitric oxide functions as a positive regulator of root hair development. Plant Signal Behav 2006, 1, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayatri, G.; Agurla, S.; Raghavendra, A.S. Nitric oxide in guard cells as an important secondary messenger during stomatal closure. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astier, J.; Gross, I.; Durner, J. Nitric oxide production in plants: an update. J Exp Bot 2018, 69, 3401–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamizo-Ampudia, A.; Sanz-Luque, E.; Llamas, A.; Galvan, A.; Fernandez, E. Nitrate reductase regulates plant nitric oxide homeostasis. Trends Plant Sci 2017, 22, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, B.R.; Sudhamsu, J.; Patel, B.A. Bacterial nitric oxide synthases. Annu Rev Biochem 2010, 79, 445–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Liu, L.L.; Wang, W.W.; Gao, H.C. Nitric oxide, nitric oxide formers and their physiological impacts in bacteria. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.E.; Lancaster, K.M. Heme P460: A (cross) link to nitric oxide. Acc Chem Res 2020, 53, 2925–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, R.K. Flavohaemoglobin: the pre-eminent nitric oxide-detoxifying machine of microorganisms. F1000Res 2020, 9, F1000 Faculty Rev-7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, B.R.; Arvai, A.S.; Ghosh, D.K.; Wu, C.; Getzoff, E.D.; Stuehr, D.J.; Tainer, J.A. Structure of nitric oxide synthase oxygenase dimer with pterin and substrate. Science 1998, 279, 2121–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, S.; Aulak, K.S.; Stuehr, D.J. Direct evidence for nitric oxide production by a nitric-oxide synthase-like protein from Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 16167–16171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kers, J.A.; Wach, M.J.; Krasnoff, S.B.; Widom, J.; Cameron, K.D.; Bukhalid, R.A.; Gibson, D.M.; Crane, B.R.; Loria, R. Nitration of a peptide phytotoxin by bacterial nitric oxide synthase. Nature 2004, 429, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Poulos, T.L. Structure-function studies on nitric oxide synthases. J Inorg Biochem 2005, 99, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, S.; Ito, S.; Yajima, S.; Sasaki, Y. Nitric oxide signaling for aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2). Appl Environ Microbiol 2022, 88, e0122222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Lim, J.; Xu, J.Y.; Yu, J.H.; Zheng, W.F. Nitric oxide as a developmental and metabolic signal in filamentous fungi. Mol Microbiol 2020, 113, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippovich, S.Y.; Bachurina, G.P. Nitric oxide in fungal metabolism (Review). Appl Biochem Microbiol 2021, 57, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Schlaeppi, K.; Banerjee, S.; Kuramae, E.E.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nature Comm 2019, 10, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, J.C.; Willig, M.R. 5 - Fungal biodiversity patterns. In Biodiversity of Fungi; Mueller, G.M., Bills, G.F., Foster, M.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, 2004; pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, J.L.; Moali, C.; Tenu, J.P. Nitric oxide biosynthesis, nitric oxide synthase inhibitors and arginase competition for L-arginine utilization. Cell Mol Life Sci 1999, 55, 1015–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanadia, R.N.; Kuo, W.N.; Mcnabb, M.; Botchway, A. Constitutive nitric oxide synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Mol Biol Int 1998, 45, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.K.; Jeong, C.S.; Choi, H.S. Identification of nitric oxide synthase in Flammulina velutipes. Mycologia 2000, 92, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.; Hecker, R.; Rockel, P.; Ninnemann, H. Role of nitric oxide synthase in the light-induced development of sporangiophores in Phycomyces blakesleeanus. Plant Physiol 2001, 126, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, B.; Buttner, S.; Ohlmeier, S.; Silva, A.; Mesquita, A.; Sampaio-Marques, B.; Osório, N.S.; Kollau, A.; Mayer, B.; Leão, C.; et al. NO-mediated apoptosis in yeast. J Cell Sci 2007, 120, 3279–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.L.; Linares, E.; Augusto, O.; Gomes, S.L. Evidence of a Ca2+-NO-cGMP signaling pathway controlling zoospore biogenesis in the aquatic fungus Blastocladiella emersonii. Fungal Genet Biol 2009, 46, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Fu, Y.P.; Jiang, D.H.; Xie, J.T.; Cheng, J.S.; Li, G.Q.; Hamid, M.I.; Yi, X.H. Cyclic GMP as a second messenger in the nitric oxide-mediated conidiation of the mycoparasite Coniothyrium minitans. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010, 76, 2830–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xi, Q.; Xu, Q.; He, M.; Ding, J.; Dai, Y.; Keller, N.P.; Zheng, W. Correlation of nitric oxide produced by an inducible nitric oxide synthase-like protein with enhanced expression of the phenylpropanoid pathway in Inonotus obliquus cocultured with Phellinus morii. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2015, 99, 4361–4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Huang, M.; Lv, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zheng, X.; Ma, Y.; Chen, C.; Tang, H. Inhibition of Trichophyton rubrum by 420-nm intense pulsed light: In vitro activity and the role of nitric oxide in fungal death. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippovich, S.Y.; Onufriev, M.V.; Peregud, D.I.; Bachurina, G.P.; Kritsky, M.S. Nitric-oxide synthase activity in the photomorphogenesis of Neurospora crassa. Appl Biochem Microbiol 2020, 56, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, R.; Zhu, D. L-Arginine enhanced perylenequinone production in the endophytic fungus Shiraia sp. Slf14(w) via NO signaling pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 106, 2619–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Bi, S.; Meng, J.; Liu, T.; Li, P.; Yu, C.; Peng, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhanced rice proline metabolism under low temperature with nitric oxide involvement. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 962460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninnemann, H.; Maier, J. Indications for the occurrence of nitric oxide synthases in fungi and plants and the involvement in photoconidiation of Neurospora crassa. Photochem Photobiol 1996, 64, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Higgins, V.J. Nitric oxide has a regulatory effect in the germination of conidia of Colletotrichum coccodes. Fungal Genet Biol 2005, 42, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Y.; Fu, Y.P.; Jiang, D.H.; Li, G.Q.; Yi, X.H.; Peng, Y.L. L-arginine is essential for conidiation in the filamentous fungus Coniothyrium minitans. Fungal Genet Biol 2007, 44, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prats, E.; Carver, T.L.; Mur, L.A. Pathogen-derived nitric oxide influences formation of the appressorium infection structure in the phytopathogenic fungus Blumeria graminis. Res Microbiol 2008, 159, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Miao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, S.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, H. Nitric oxide mediates the fungal-elicitor-enhanced biosynthesis of antioxidant polyphenols in submerged cultures of Inonotus obliquus. Microbiology (Reading) 2009, 155, 3440–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Huang, C.; Chen, Q.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, J. Nitric oxide alleviates heat stress-induced oxidative damage in Pleurotus eryngii var. tuoliensis. Fungal Genet Biol 2012, 49, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, S.K.; Ghosh, S. Nitric oxide production by necrotrophic pathogen Macrophomina phaseolina and the host plant in charcoal rot disease of jute: complexity of the interplay between necrotroph-host plant interactions. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e107348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, A.T.; Ramos, M.S.; Marcos, J.F.; Carmona, L.; Strauss, J.; Cánovas, D. Nitric oxide synthesis by nitrate reductase is regulated during development in Aspergillus. Mol Microbiol 2016, 99, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Yue, S.; Gao, T.; Zhu, J.; Ren, A.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M. Nitrate reductase-dependent nitric oxide plays a key role on MeJA-induced ganoderic acid biosynthesis in Ganoderma lucidum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 10737–10753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hosni, K.; Shahzad, R.; Khan, A.L.; Imran, Q.M.; Al Harrasi, A.; Al Rawahi, A.; Asaf, S.; Kang, S.M.; Yun, B.W.; Lee, I.J. Preussia sp. BSL-10 producing nitric oxide, gibberellins, and indole acetic acid and improving rice plant growth. J Plant Interact 2018, 13, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, P.R.; Woo, D.K.; Ball, K.; Wojcik, J.; Liu, L.; Poyton, R.O. Oxygen-regulated isoforms of cytochrome c oxidase have differential effects on its nitric oxide production and on hypoxic signaling. PNAS 2008, 105, 8203–8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Lin, W.; Chen, Y.; Gao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, D. Heat stress enhanced perylenequinones biosynthesis of Shiraia sp. Slf14(w) through nitric oxide formation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 107, 3745–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, R.I.; Nasuno, R.; Takagi, H. Nitric oxide signaling in yeast. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016, 100, 9483–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Cano, A.; Marcos, A.T.; Strauss, J.; Canovas, D. Evidence for an arginine-dependent route for the synthesis of NO in the model filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Environ Microbiol 2021, 23, 6924–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.W.; Fushinobu, S.; Zhou, S.M.; Wakagi, T.; Shoun, H. The possible involvement of copper-containing nitrite reductase (NirK) and flavohemoglobin in denitrification by the fungus Cylindrocarpon tonkinense. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2010, 74, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoun, H.; Fushinobu, S.; Jiang, L.; Kim, S.-W.; Wakagi, T. Fungal denitrification and nitric oxide reductase cytochrome P450nor. Phil Trans R Soc B 2012, 367, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldossari, N.; Ishii, S. Fungal denitrification revisited - Recent advancements and future opportunities. Soil Biol Biochem 2021, 157, 108250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Shoun, H. The copper-containing dissimilatory nitrite reductase involved in the denitrifying system of the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 4146–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozkina, E.V.; Kurakov, A.V. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction in fungi under conditions of hypoxia and anoxia: a review. Appl Biochem Microbiol 2007, 43, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinko, T.; Berger, H.; Lee, W.; Gallmetzer, A.; Pirker, K.; Pachlinger, R.; Buchner, I.; Reichenauer, T.; Guldener, U.; Strauss, J. Transcriptome analysis of nitrate assimilation in Aspergillus nidulans reveals connections to nitric oxide metabolism. Mol Microbiol 2010, 78, 720–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horchani, F.; Prévot, M.; Boscari, A.; Evangelisti, E.; Meilhoc, E.; Bruand, C.; Raymond, P.; Boncompagni, E.; Aschi-Smiti, S.; Puppo, A.; et al. Both plant and bacterial nitrate reductases contribute to nitric oxide production in Medicago truncatula nitrogen-fixing nodules. Plant Physiol 2011, 155, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada-Jimenez, M.; Llamas, A.; Galvan, A.; Fernandez, E. Role of nitrate reductase in NO production in photosynthetic eukaryotes. Plants (Basel) 2019, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulbir, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Das, S.; Devi, T.; Goswami, M.; Yenuganti, M.; Bhardwaj, P.; Ghosh, S.; Sahoo, S.C.; Kumar, P. Oxygen atom transfer promoted nitrate to nitric oxide transformation: a step-wise reduction of nitrate → nitrite → nitric oxide. Chem Sci 2021, 12, 10605–10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samalova, M.; Johnson, J.; Illes, M.; Kelly, S.; Fricker, M.; Gurr, S. Nitric oxide generated by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae drives plant infection. New Phytol 2013, 197, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Takaya, N. Denitrification by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum involves NADH-nitrate reductase. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2008, 72, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planchet, E.; Kaiser, W.M. Nitric oxide production in plants: facts and fictions. Plant Signal Behav 2006, 1, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethke, P.C.; Badger, M.R.; Jones, R.L. Apoplastic synthesis of nitric oxide by plant tissues. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Nonenzymatic nitric oxide production in humans. Nitric Oxide 1998, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, B.; Barugahare, A.A.; Lo, T.L.; Huang, C.; Schittenhelm, R.B.; Powell, D.R.; Beilharz, T.H.; Traven, A. A metabolic checkpoint for the yeast-to-hyphae developmental switch regulated by endogenous nitric oxide signaling. Cell Rep 2018, 25, 2244–2258.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedelska, T.; Luhova, L.; Petrivalsky, M. Nitric oxide signalling in plant interactions with pathogenic fungi and oomycetes. J Exp Bot 2021, 72, 848–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Huang, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M. Nitric oxide negatively regulates the rapid formation of Pleurotus ostreatus primordia by inhibiting the mitochondrial aco gene. J Fungi 2022, 8, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, A.T.; Ramos, M.S.; Schinko, T.; Strauss, J.; Cánovas, D. Nitric oxide homeostasis is required for light-dependent regulation of conidiation in Aspergillus. Fungal Genet Biol 2020, 137, 103337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengkit, A.; Jeon, S.S.; Son, S.J.; Shin, J.H.; Baik, K.Y.; Choi, E.H.; Park, G. Identification and functional analysis of endogenous nitric oxide in a filamentous fungus. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, N.N.; Veerana, M.; Ketya, W.; Sun, H.N.; Park, G. RNA-seq-based transcriptome analysis of nitric oxide scavenging response in Neurospora crassa. J Fungi 2023, 9, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.Q.; Liao, B.Y.; Zong, Y.W.; Shi, Y.Y.; Liao, M.; Wang, J.N.; Zhou, X.D.; Cheng, L.; et al. Extracellular vesicles of Candida albicans regulate its own growth through the l-arginine/nitric oxide pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 107, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golderer, G.; Werner, E.R.; Leitner, S.; Gröbner, P.; Werner-Felmayer, G. Nitric oxide synthase is induced in sporulation of Physarum polycephalum. Genes Dev 2001, 15, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Gao, Z.; Wang, C.; Huang, L.; Kang, Z.; Zhang, H. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species coordinately regulate the germination of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici urediniospores. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oiki, S.; Nasuno, R.; Urayama, S.-I.; Takagi, H.; Hagiwara, D. Intracellular production of reactive oxygen species and a DAF-FM-related compound in Aspergillus fumigatus in response to antifungal agent exposure. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 13516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.L.; Wu, C.G.; Ren, A.; Hu, Y.R.; Wang, S.L.; Han, X.F.; Shi, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, M.W. Putrescine regulates nitric oxide accumulation in Ganoderma lucidum partly by influencing cellular glutamine levels under heat stress. Microbiol Res 2020, 239, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchinina, E.A.; Nikitina, V.E. Role of the NO synthase system in response to abiotic stress factors for Basidiomycetes Lentinula edodes and Grifola frondosa. Mikrobiologiia 2016, 85, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Chen, Q.; Zou, Y.J.; Zhao, M.R.; Zhang, J.X. Nitric oxide is involved in the regulation of trehalose accumulation under heat stress in Pleurotus eryngii var. tuoliensis. Biotechnol Lett 2012, 34, 1915–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrovic, T.; Palhano, F.L.; Barja-Fidalgo, C.; DeFreitas, M.; Orlando, M.T.; Fernandes, P.M. Role of nitric oxide in the response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells to heat shock and high hydrostatic pressure. FEMS Yeast Res 2003, 3, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, P.R.; David, P.S.; McClure, T.; Crook, Z.; Poyton, R.O. Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase produces nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions: Implications for oxygen sensing and hypoxic signaling in eukaryotes. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidya, S.; Cary, J.W.; Grayburn, W.S.; Calvo, A.M. Role of nitric oxide and flavohemoglobin homolog genes in Aspergillus nidulans sexual development and mycotoxin production. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77, 5524–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.N.; Ketya, W.; Park, G. Intracellular nitric oxide and cAMP are involved in cellulolytic enzyme production in Neurospora crassa. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.P.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.J.; Wang, J.W.; Zheng, L.P. Nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide signaling in extractive Shiraia fermentation by Triton X-100 for hypocrellin A production. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.J.; Li, X.P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.W. Nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside-induced transcriptional changes and hypocrellin biosynthesis of Shiraia sp. S9. Microb Cell Factories 2021, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrion-Gomez, J.L.; Benito, E.P. Flux of nitric oxide between the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea and the host plant. Mol Plant Pathol 2011, 12, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Baarlen, P.; Staats, M.; Van Kan, J.A.L. Induction of programmed cell death in lily by the fungal pathogen Botrytis elliptica. Mol Plant Pathol 2004, 5, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.; Liang, S.; Ning, G.; Xu, N.; Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Lin, F. MoARG1, MoARG5,6 and MoARG7 involved in arginine biosynthesis are essential for growth, conidiogenesis, sexual reproduction, and pathogenicity in Magnaporthe oryzae. Microbiol Res 2015, 180, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.F.; Lu, D.H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Fu, R.T. Transcriptional profiling provides new insights into the role of nitric oxide in enhancing Ganoderma oregonense resistance to heat stress. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Huang, W.; Xiong, C.; Zhao, J. Transcriptome analysis reveals the role of nitric oxide in Pleurotus eryngii responses to Cd2+ stress. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, K.T.; Shinyashiki, M.; Switzer, C.H.; Valentine, J.S.; Gralla, E.B.; Thiele, D.J.; Fukuto, J.M. Effects of nitric oxide on the copper-responsive transcription factor Ace1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: cytotoxic and cytoprotective actions of nitric oxide. Arch Biochem Biophys 2000, 377, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, S.; Demain, A.L. Bioactive products from fungi. Food Bioactives 2017, 2017 Jan 11, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.F.; Zhang, M.M.; Zhao, Y.X.; Wang, Y.; Miao, K.J.; Wei, Z.W. Accumulation of antioxidant phenolic constituents in submerged cultures of Inonotus obliquus. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.Y.; Chai, R.Y.; Qiu, H.P.; Jiang, H.; Mao, X.Q.; Wang, Y.L.; Liu, F.Q.; Sun, G.C. An S-(hydroxymethyl) glutathione dehydrogenase is involved in conidiation and full virulence in the rice blast fungus. Plos One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fungus | Mechanism for NO Synthesis | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus nidulans | NO2- dependent: nitrate reductase activity | [51] |

| Blastocladiella emersonii | NOS dependent: enzyme activity | [37] |

| Blumeria graminis | NOS dependent: enzyme inhibition | [47] |

| Colletotrichum coccodes | NOS dependent: enzyme inhibition | [45] |

| Coniothyrium minitans | NOS dependent: enzyme activity / inhibition | [38,46] |

| Cryphonectria parasitica | NOS dependent: enzyme inhibition | [46] |

| Flammulina velutipes | NOS dependent: protein isolation and enzyme activity | [34] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | NO2- dependent: nitrate reductase activity | [52] |

| Inonotus obliquus | NOS dependent: enzyme inhibition | [48] |

| Inonotus obliquus cocultured with Phellinus morii | NOS dependent: gene identification and enzyme activity / inhibition | [39] |

| Macrophomina phaseolina | NOS dependent: gene identification and enzyme inhibition | [50] |

| Neurospora crassa | NOS dependent: enzyme inhibition | [44] |

| NOS dependent: enzyme activity | [41] | |

| Phycomyces blakesleeanus | NOS dependent: enzyme activity/inhibition | [35] |

| Pleurotus eryngii var. tuoliensis | NOS dependent: enzyme inhibition | [49] |

| Preussia sp. BSL-10 | Expression of NOS, nitrate reductase, and nitrite reductase | [53] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | NOS dependent: enzyme activity | [36] |

| NOS dependent: protein isolation and enzyme activity/inhibition | [33] | |

| NO2- dependent: mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase and nitrite reductase under hypoxia condition |

[54] | |

| Shiraia sp. Slf14 | NOS dependent: gene identification | [55] |

| NOS dependent: enzyme activity and gene expression NO2- dependent: nitrate reductase activity |

[42] | |

| Trichophyton rubrum | NOS dependent: enzyme activity | [40] |

| Function | Fungus | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth and development | Aspergillus nidulans | Reduced conidiation and induced the formation of cleistothecia | [51] |

| The light regulation of conidiation | [75] | ||

| Blastocladiella emersonii | Controlling zoospore biogenesis | [37] | |

| Candida albicans | Growth promotion and pathogenesis by extracellular vesicles | [78] | |

| Colletotrichum coccodes | Regulation of spore germination | [45] | |

| Coniothyrium minitans | The nitric oxide-mediated conidiation | [38,46] | |

| Neurospora crassa | The light induced conidiation and carotenogenesis | [41,44] | |

| Regulate mycelial development and conidia formation. | [76] | ||

| Impacting the growth and development of hyphae (vegetative growth) | [77] | ||

| Phycomyces blakesleeanus | The light-induced development of sporangiophores | [35] | |

| Physarum polycephalum | Sporulation | [79] | |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Primordia formation | [74] | |

| Puccinia striiformis f.sp. tritici | Induce spore germination | [80] | |

| Response to stresses | Aspergillus fumigatus | Effects of antifungal agent (farnesol) on germination | [81] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | Heat stress -induced ganoderic acids levels | [82] | |

| Lentinula edodes and Grifola frondosa | Tolerance to superoptimal pH and in nitrogen-limitation | [83] | |

| Pleurotus eryngii var. tuoliensis | Heat stress-induced oxidative damage | [49] | |

| Heat stress-induced trehalose accumulation | [84] | ||

| Rhizophagus irregularis | Enhanced host plant tolerance to low temperature stress by regulating proline accumulation in plant | [43] | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Cytoprotective effect from heat-shock or high hydrostatic pressure | [85] | |

| Hypoxia signaling | [54,86] | ||

| H2O2-induced apoptosis | [36] | ||

| Shiraia sp. Slf14(w) | Heat stress enhanced perylenequinones biosynthesis | [55] | |

| Trichophyton rubrum | Reduction in fungal viability by 420-nm intense pulsed light | [40] | |

| Metabolism | Aspergillus nidulans | Mycotoxin production | [87] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | Methyl jasmonate -induced ganoderic acid biosynthesis | [52] | |

| Inonotus obliquus | Biosynthesis of antioxidant polyphenols / Accumulation of antioxidant phenolic constituents | [48] | |

|

Inonotus obliquus and Phellinus morii |

Increase in level of styrylpyrone polyphenols in fungal interspecific interaction | [39] | |

| Neurospora crassa | Cellulolytic enzyme production | [88] | |

| The pentose and glucuronate interconversion, fructose and mannose metabolism, galactose metabolism, amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism and tyrosine metabolism | [77] | ||

| Preussia sp. BSL-10 | Improve rice plant growth and related gene expression | [53] | |

| Shiraia sp. S9 | Hypocrellin A production | [89,90] | |

| Shiraia sp. Slf14(w) | Production of secondary metabolite perylenequinone | [42,55] | |

| Virulence and pathogenicity | Aspergillus nidulans | Mycotoxin production | [87] |

| Blumeria graminis | Influences formation of the appressorium infection structure | [47] | |

| Botrytis cinerea | Saprophytic growth and plant infection | [91] | |

| Botrytis elliptica | Induction of programmed cell death in lily | [92] | |

| Magnaporthe oryzae | Drives plant infection (delays germling development and reduces disease lesion numbers) | [67] | |

| Conidial germination and appressorium formation (infectious morphogenesis) | [93] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).