2.1. Slip Bonds

There are different types of bonds: one type is the ideal bond [

42,

43] being insensitive against tensile forces. It has been suggested to play a role in enabling the receptor-ligand pair to withstand tensile force, but it has not yet been reported in experiments.

Usually bonds weaken under the action of mechanical load. Such chemical bonds, whose dissociation rate grows with increasing external force, are called slip bonds. The name was coined by Bell in 1978 for biological adhesive bonds [

44]. An example are B cells which apply forces to segregate and rupture clusters, and individual antibody-antigen interactions which exhibit a slip-bond character [

45]. Thus they show lifetime reduction under force. Unbinding forces of single antibody-antigen complexes correlate with their thermal dissociation rates. The same TS must be crossed in spontaneous and in forced unbinding. The unbinding path under load cannot be too different from the one at zero force.

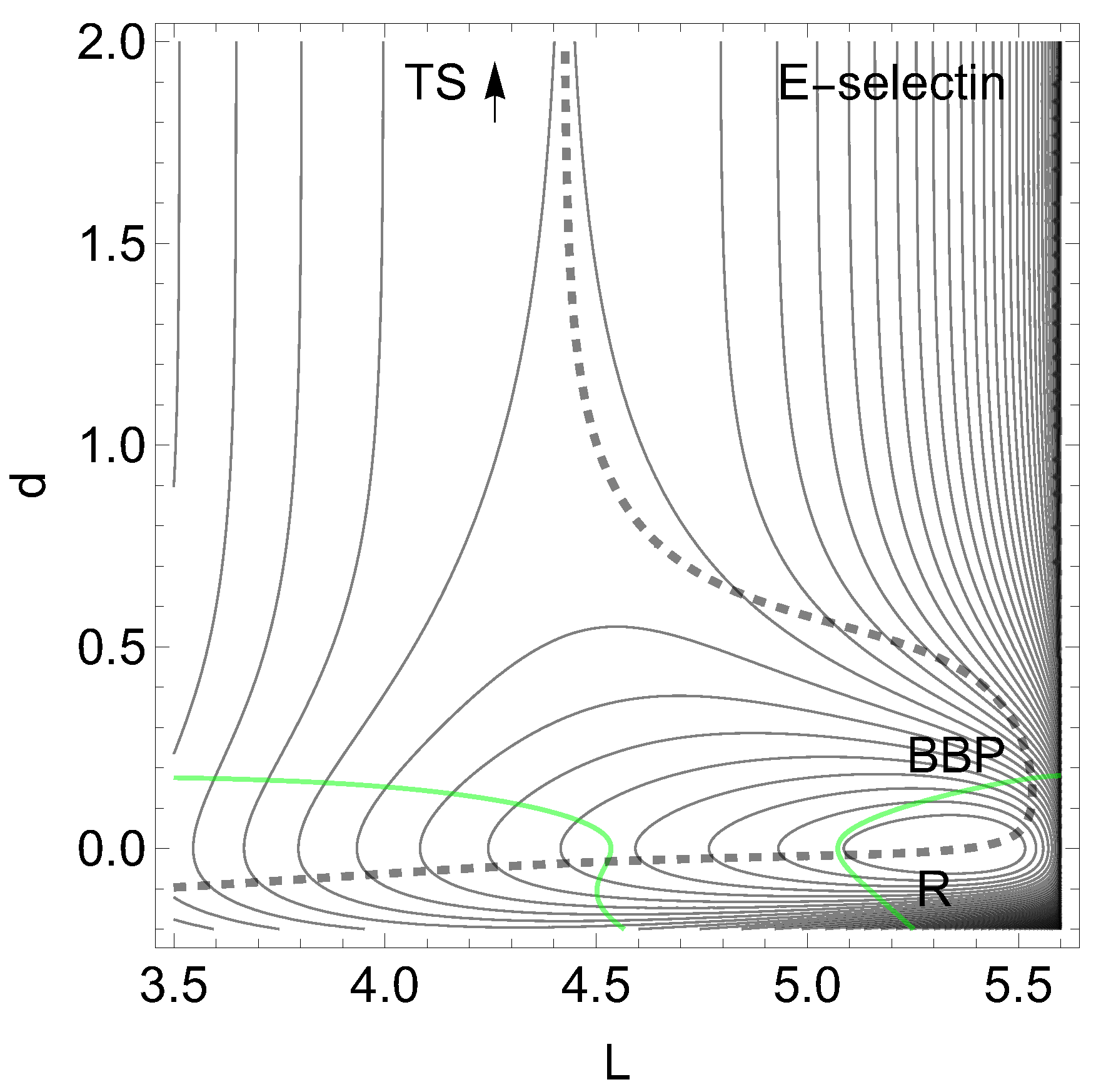

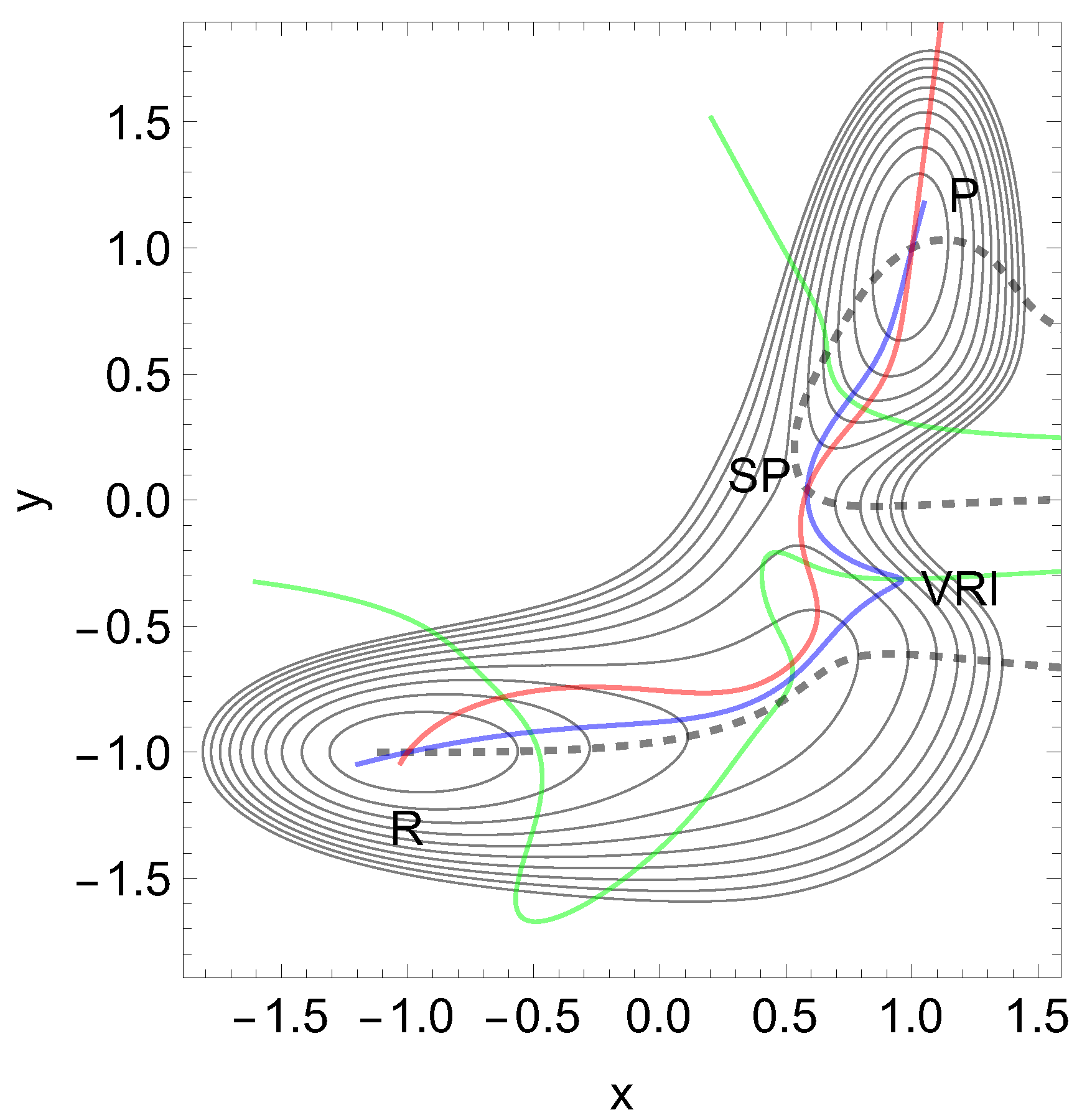

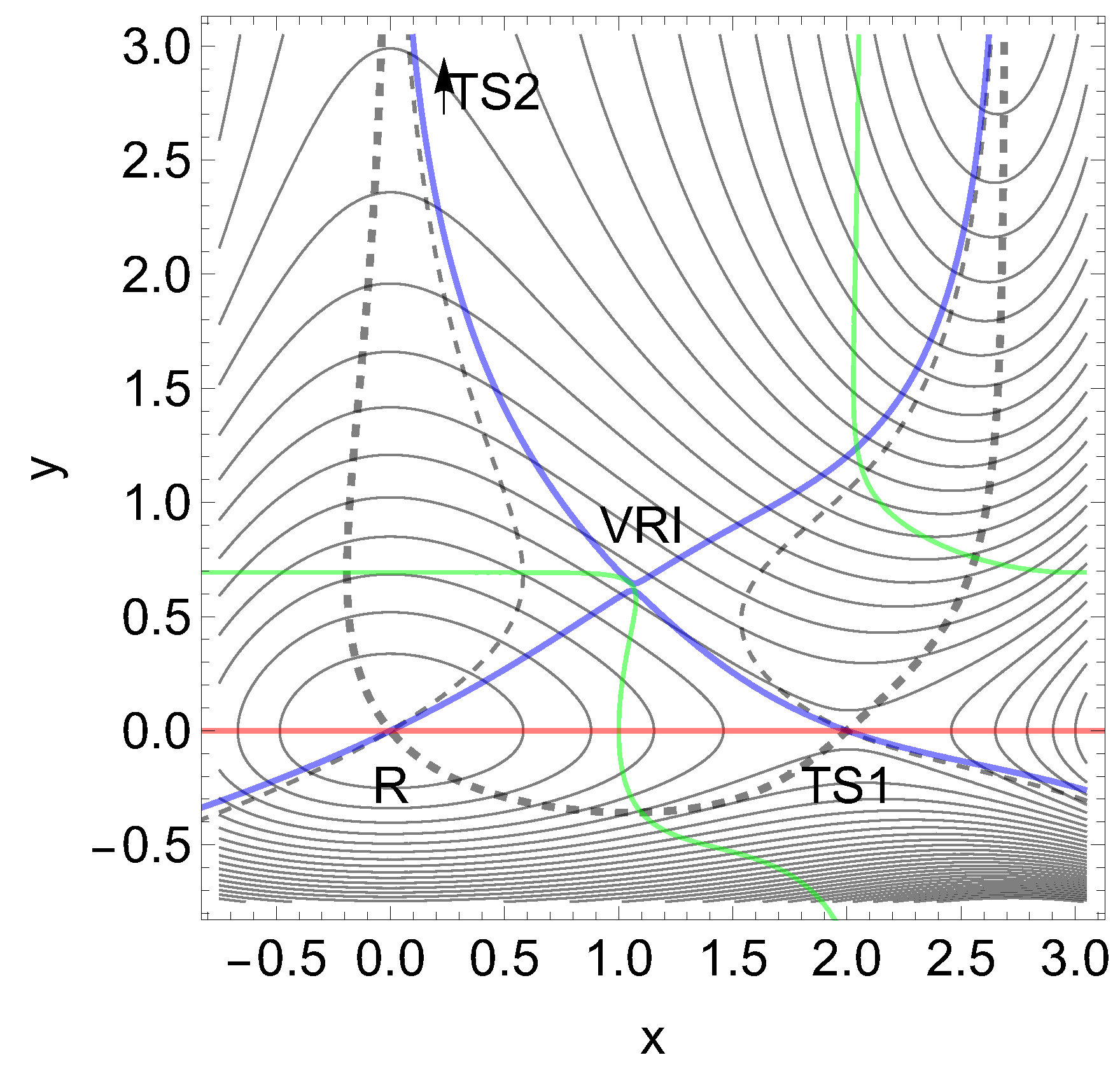

Let us assume the simplified 2-dimensional landscape,

, of a molecular system [

5] constituted for the receptor of endothelial selectin (E-selectin) and the ligand sLe

x [

46] linked by a non-covalent bond. It is a challenge to select special coordinates when dealing with protein-ligand interactions. We find a high dimensionality and a great flexibility. Here [

5] one uses two length coordinates,

in nm, to describe the movement of the ligand.

L is the protein extension, but

d is the distance to the ligand. Forces are given in pN. The bound state corresponds to a minimum of the PES named reactant,

R, in

Figure 1. (All drawings and calculations are done with Mathematica 13.3.1.0 for platform Linux x86 (64-bit).) The TS is the final level of a Morse ascent at large

d and

nm.

The application of Eqs.(

3) and (

4) for a tensile mechanical force,

, along the dashed NT, decreases the height of the barrier if

F increases from zero to some value. It needs here a very large force up to

pN. But it continuously decreases the barrier, and at least the TS and the former minimum,

R, coalesce at the BBP, the crossing of the NT and the right

line. As a result, the life time of the slip bond decreases when it is stressed by the tensile force [

47,

48]. When the external force is applied then the effective PES,

, describes the evolution of the bound state to the unbound state, and is given by Eq. (

1). Note that the dashed NT has a turning point (TP) at

. This does not disturb the slip character, see also an extreme case in ref. [

6]. However, it is in a contradiction to a statement that catch bond character holds behind so-called

points [

5,

14]. Concluding this example we have to state that the putative model surface for E-selectin with ligand sLe

x [

5] is not appropriated to the slip-catch-slip behavior of this molecular complex.

Slip bonds depict directions where the corresponding NT to

leads more or less directly from a minimum to a transition state. In

Figure 1, seen from

R, we can assume that here all directions to above are good directions. Note that the NT describes the pathways of the stationary points under the external force. Here only two stationary points emerge, the minimum,

R, and the

of the dissociation.

2.2. Catch Bonds

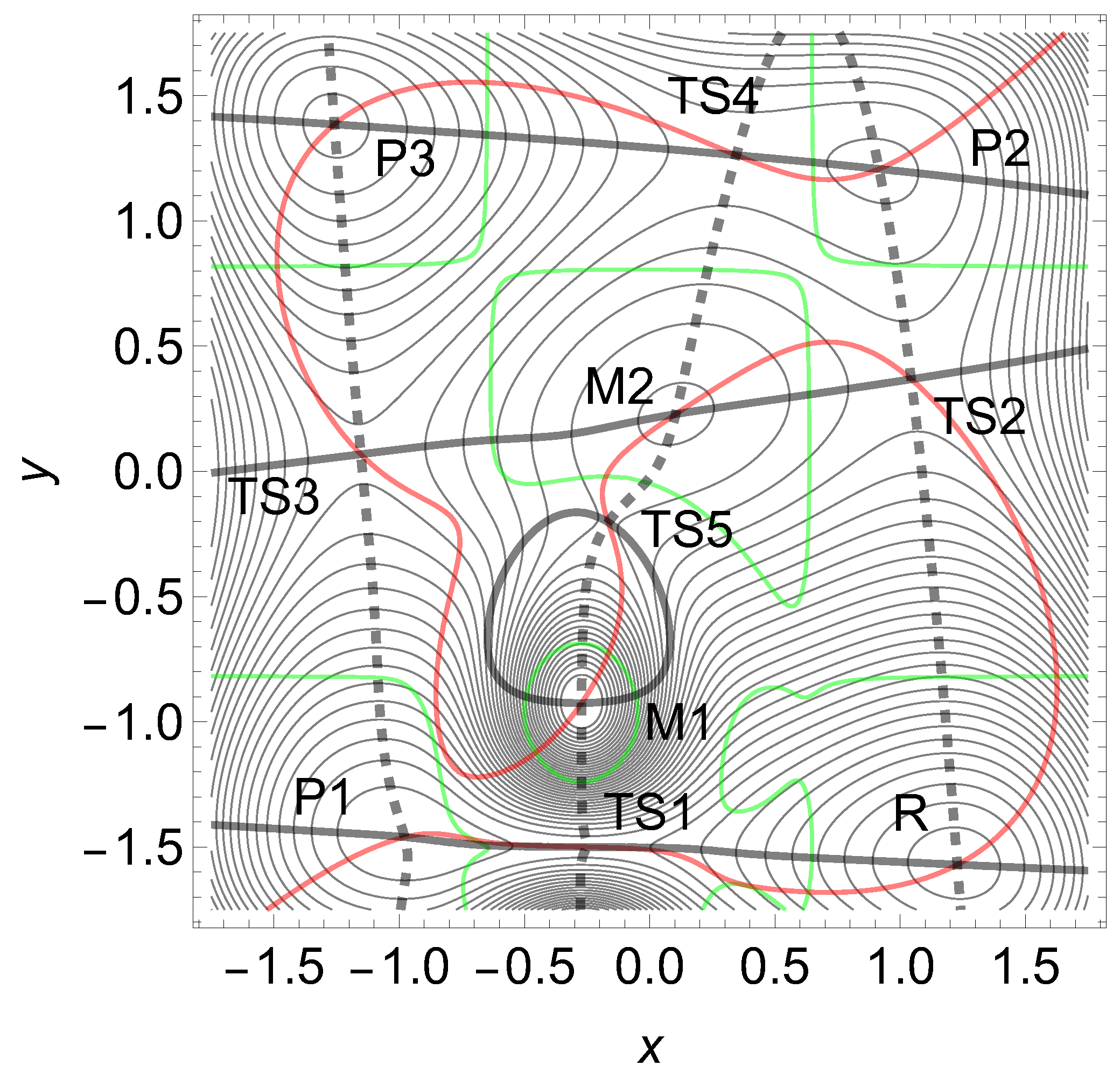

Seen from the TS the slip direction is the natural direction of the SP valley, compare the TS on the red

line in

Figure 2. Of course, one can deviate to both sides up to a certain degree, and one still goes downhill the reaction valley. It would still hold the slip bond character. However, if the external excitation direction becomes more or less orthogonal to the col then one goes uphill. Such a case was then named catch bond direction if the barrier increases under the external force.

Note that for an N-dimensional PES we have a one-dimensional valley path over the SP1, the slip direction, however, we have directions orthogonally uphill into the PES mountains.

An early work [

1] describes the occurrence of states in which adhesion cannot be reversed by application of tension. Such states occur only if the adhesion molecules have certain constitutive properties thus having catch-bond character. Often catch bond behavior is connected to sheer forces in proteins [

49]. Another example is dynein’s interaction with micro tubules which behaves like a catch bond [

50]. The dependence on the force direction to modulate the multistep process of translation is reported in refs. [

51,

52]. The calculated forces alter the transition state barrier of the peptidyl transfer reaction catalyzed by the ribosome for two alanine residues in the peptidyl transfer center as a function of the direction of the force applied to the P-site residue. In a current discussion [

53] vinculin is a load-bearing linker protein that exhibits directional catch bonding due to interactions between the tail domain and the filamentous F-actin, see also refs. [

54,

55]. There is a large amount of reports to catch bonds, see for example [

2,

3,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66].

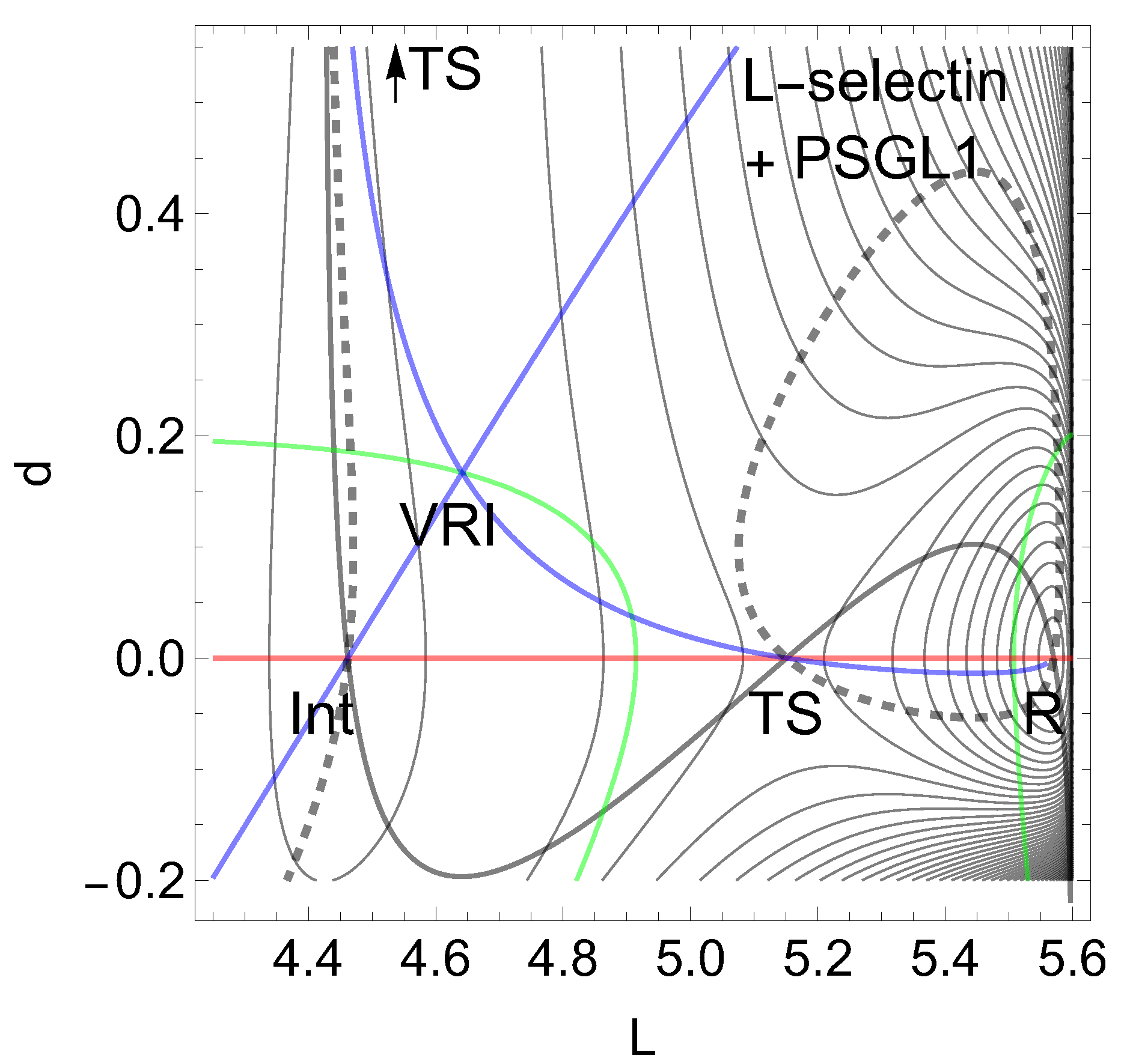

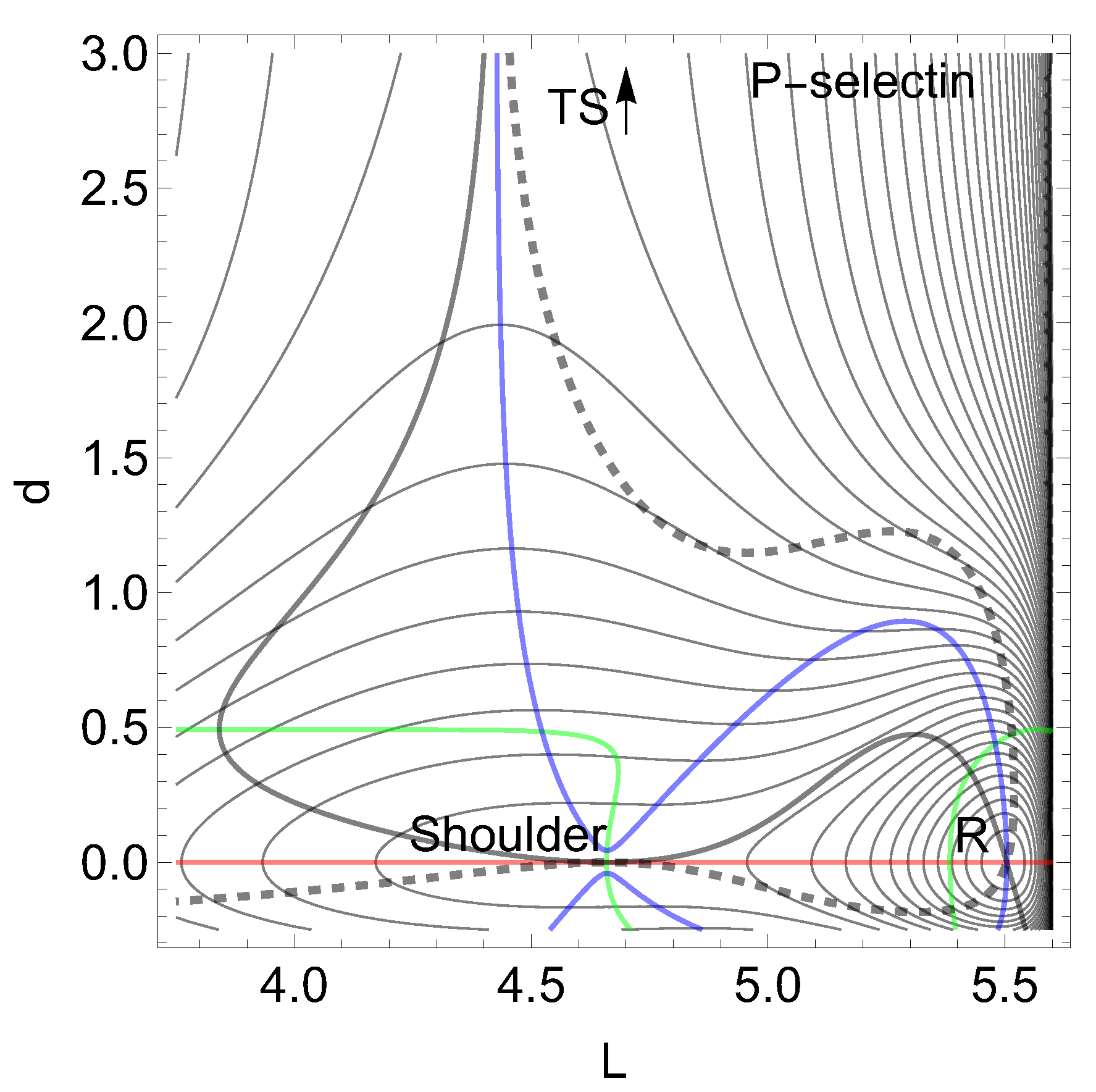

A) Molecular example

First we report a current example of a catch bond behavior in leucocyte selectin (L-selectin), see

Figure 2. For the chemical details see ref. [

3,

5,

67,

68], as well as for the representation of the molecule. The formula of the 2D model PES is given in the appendix by Eq. (

7). There are used two length coordinates,

in nm to describe the movement of a ligand.

L is the protein extension, but

d is the distance to the ligand. Forces are given in pN.

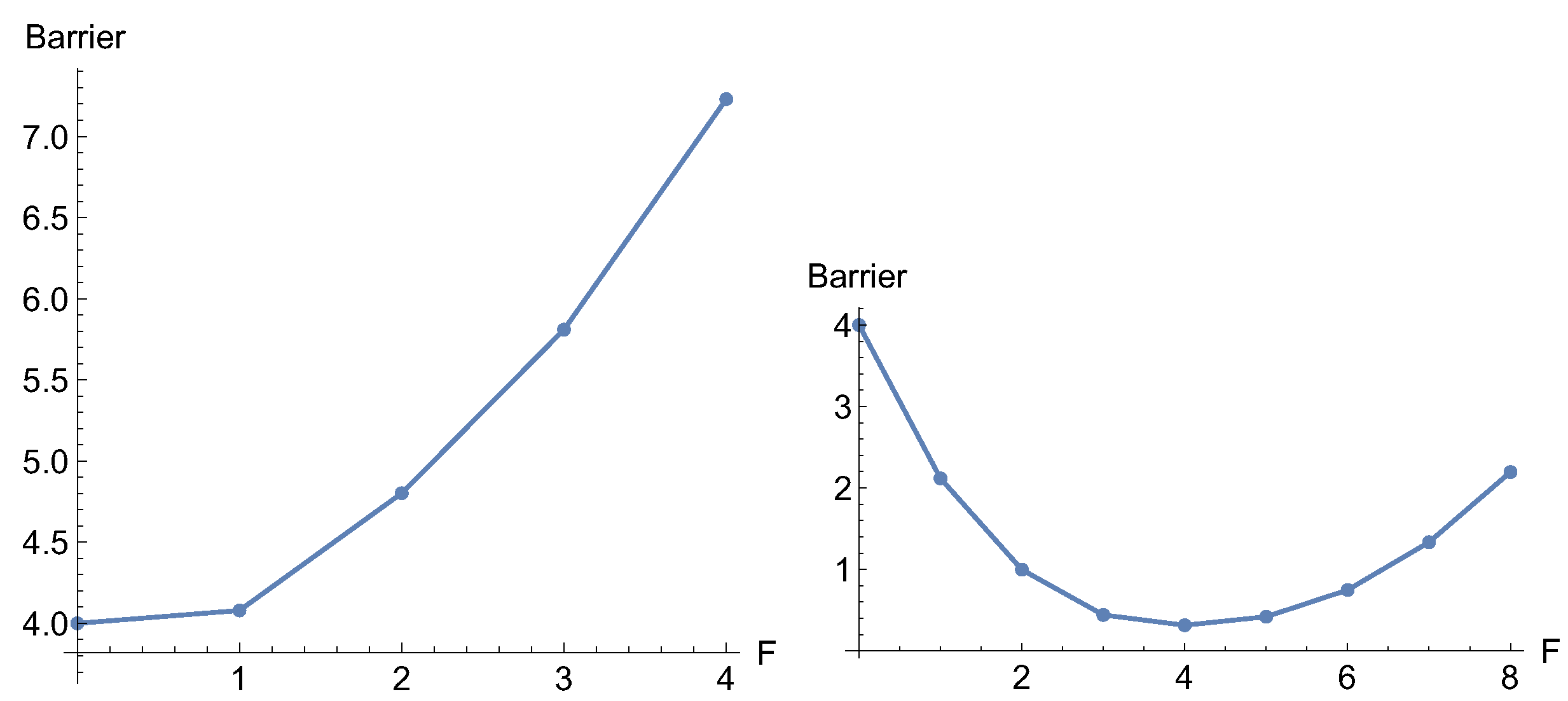

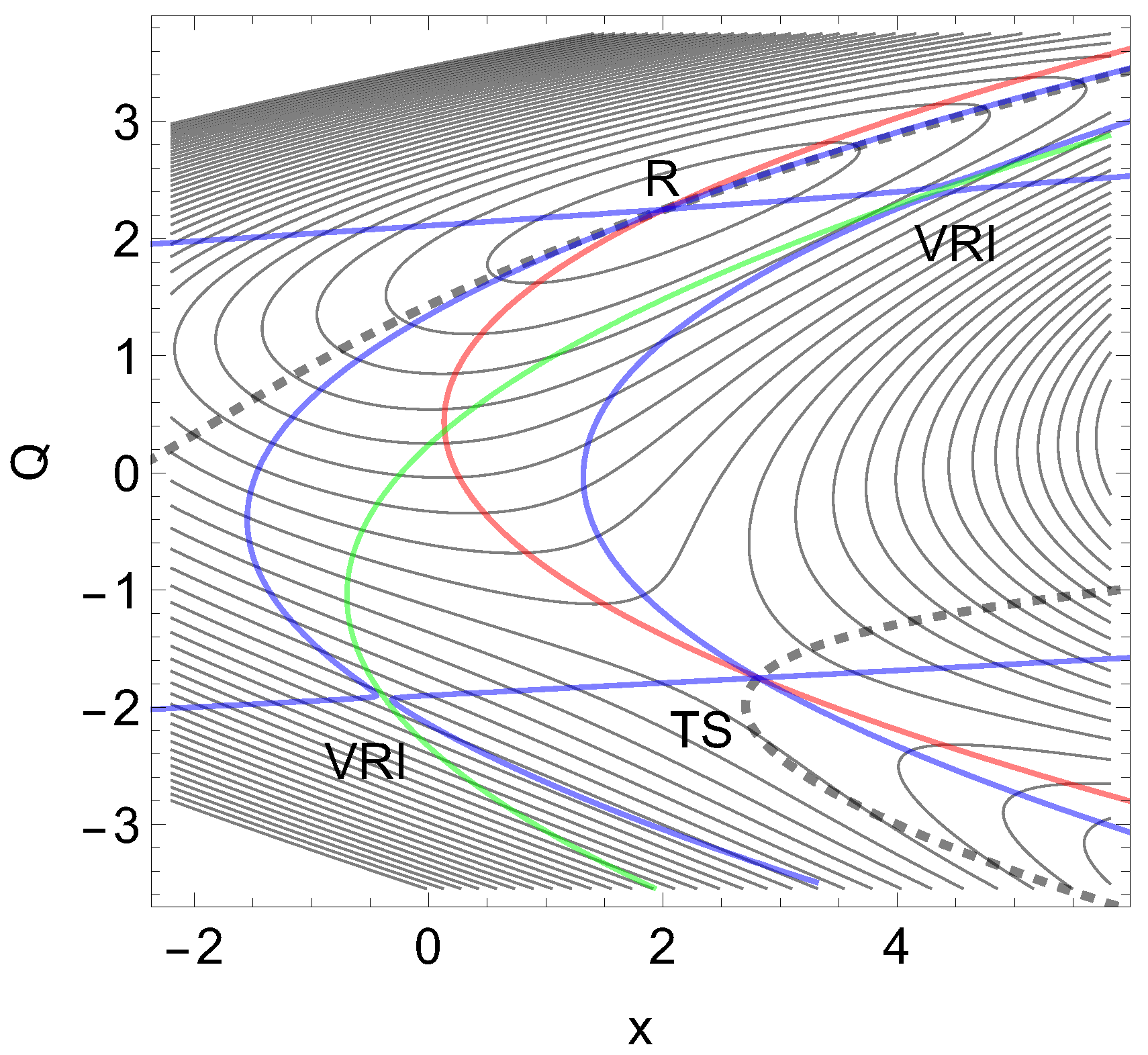

On the L-axis we have two minima and one TS. This axis is also an NT to direction (-1, 0) drawn in red. It is a slip direction. The right minimum, R at (5.58, 0), is the global minimum but the left one at (4.48, 0) is a flat intermediate. Along increasing d on the line with we have a dissociation channel of the ligand. Thin lines of the figure are level lines with steps of 5.2 pN. The green lines are the lines of the PES.

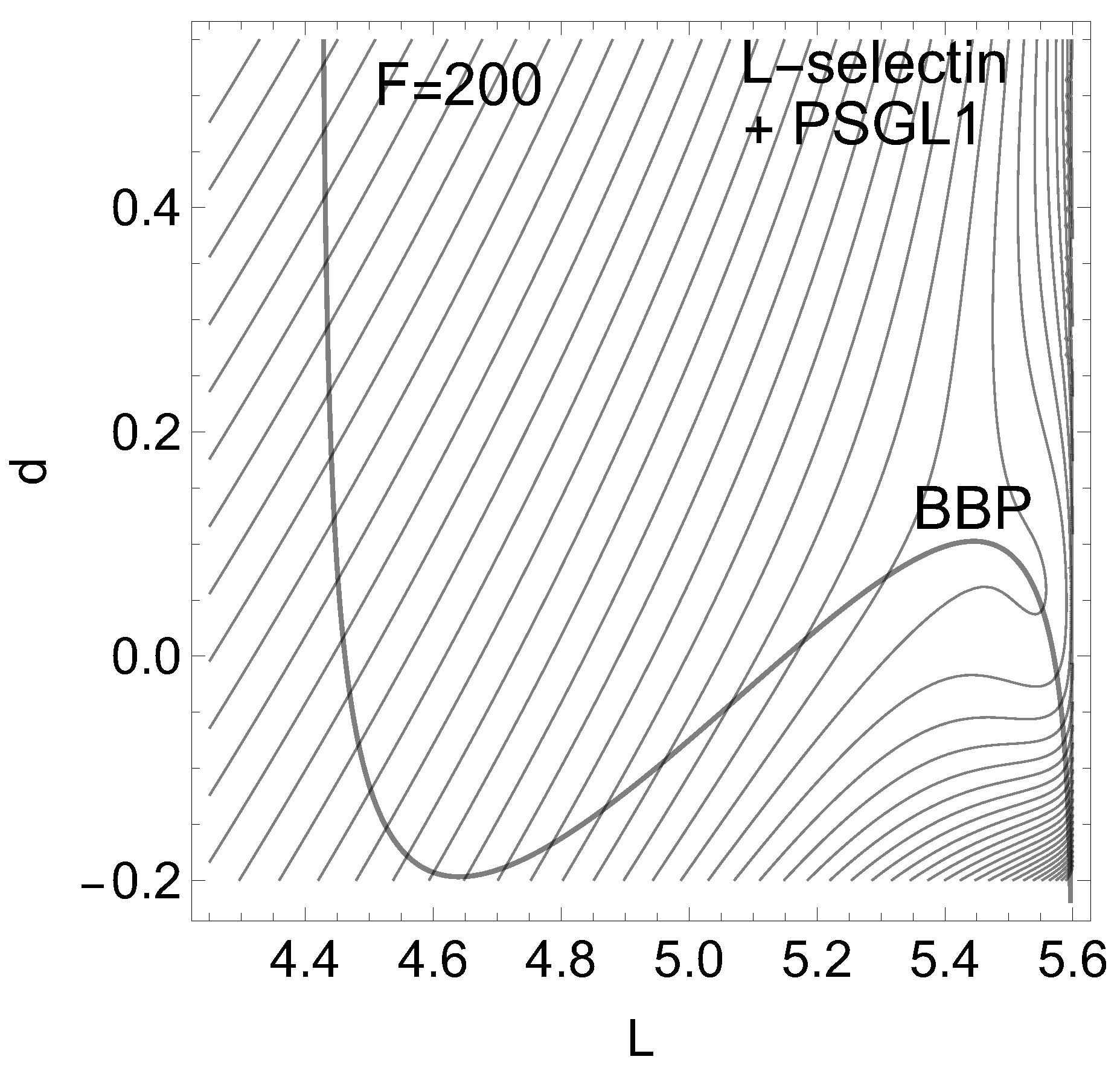

Of interest also is the gray-black NT to direction (-1,1) from

R over

through

to dissociation. It should be the usual direction of the process of interest: globally,

L decreases, but

d increases along (-1,1), if the ligand moves away. It has slip bond character because along this NT, under increasing force,

F, the barrier decreases. Along the NT, under force, the minimum,

R, and the TS move towards each other, and this causes a decrease of the barrier. If one exites the system up to

pN then minimum

R and TS coalesce at a barrier breking point (BBP), see

Figure 3. It is the crossing of the NT and the green line in

Figure 2.

On the PES of

Figure 2, through a VRI point at (4.65, 0.17) is calculated a singular NT which is drawn in blue. The VRI point marks the border between the two (orthogonal) valleys to

R, or to the dissociation TS, and the singular NT separates the two thickly dashed branches of the NT of special interest here. It goes to an orthogonal direction, (1, 1), a pulling of the molecule along both coordinates. The NT to this direction is shown by black dashes. The pulling along

L seems to be counterproductive for the process. Seen from

R, the pulling points into a dead valley at the right hand side of the figure. The right closed branch of the dashed NT connects only

R and the

. Its upper arc is disrupted from the left branch through

by the blue, the singular NT. This NT acts as a separatrix [

5].

It is a central condition of the catch bond behavior: The main exit to the dissociation, and the NT of interest through the minimum, R, are divided by a singular NT.

If one excites the molecule along direction (1, 1) then one moves the stationary points

R and

along the upper arc of the dashed NT. Here we find catch bond behavior, see

Table 1 in the appendix. Why? The minimum bowl is deep, thus has strong curvatures. Its eigenvalues in

L- and

d-directions are

but the eigenvalues at the

are

. Thus any movement along the given excitation for

F up to

pN will move more the TS than the minimum. That is why the second part of Eq. (2) does play here the main part. The change of

is only 1/5 of the change of the barrier. For higher

F values, however, the arc over

and

R closes, and we go back to slip behavior, to a decreasing height of the barrier. And at the end, if

F is so large that the BBP on the green line is reached from both sides then the molecule finally slides to dissociation, compare

Figure 3. We guess that the 2D example of

Figure 2 will be a main pattern for catch bonds. It is already anticipated by a schematic picture by

Figure 2 B in ref. [

3].

Of course, by drawing a comparison of the catch bond NT, the thickly dashed upper arc to direction (1, 1), its slip bond counter part below to direction (-1, -1), and another usual slip bond NT to orthogonal direction (-1, 1), the gray-black one, this shows that one has an ’asymmetry’ for the catch bond [

69]. This needs no further reasoning. One cannot expect that the catch bond property holds for any direction of the external force. Thus, it does not exist ’the catch bond’, but a bond can have ’catch bond character’.

In the following we discuss further different scenarios for the force-induced change of the TS of simple two-dimensional (2D) PES, especially for an inversion of the relations between the curvatures in minimum and TS, in comparison to the former example. This approach was proposed by Suzuki and Dudko [

4].

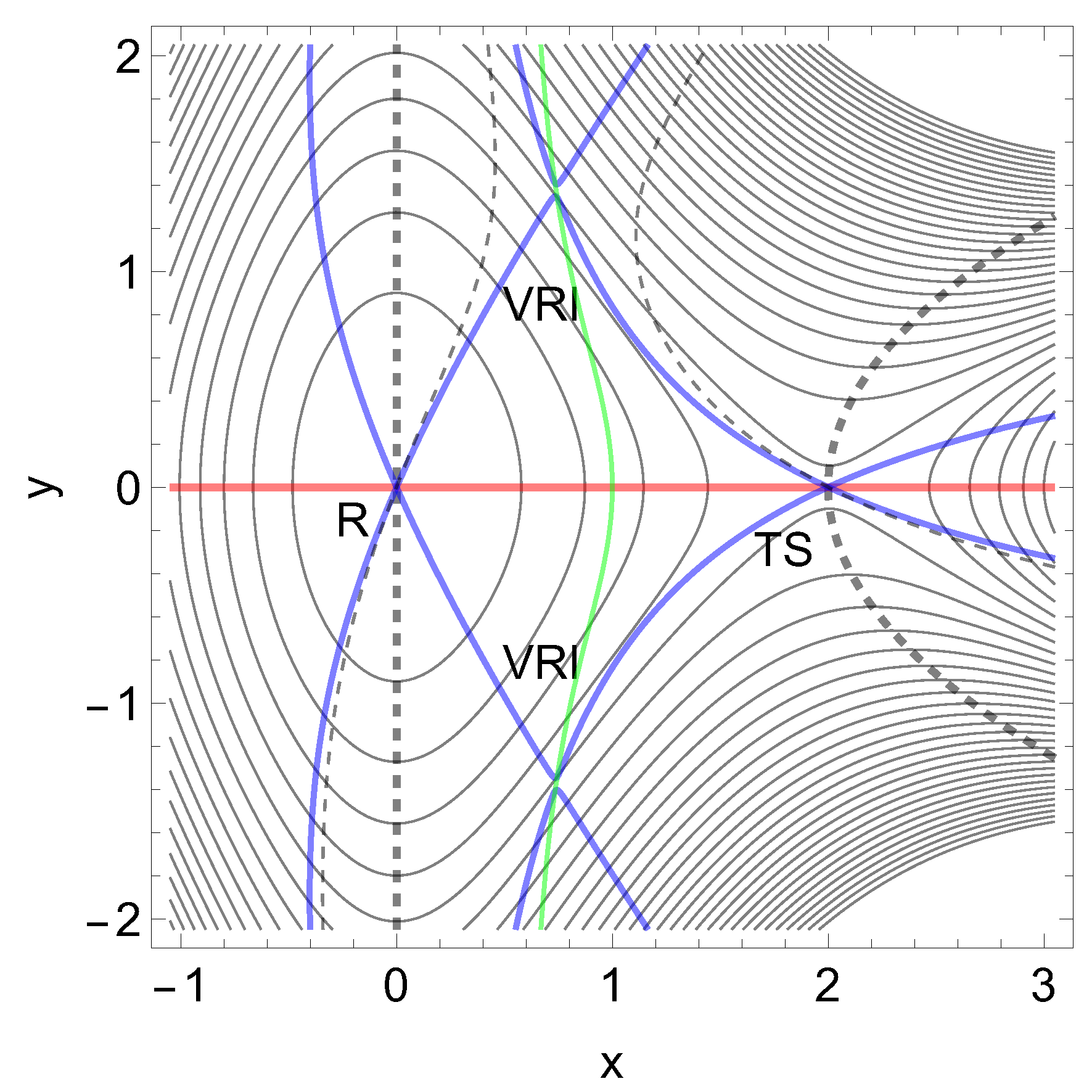

B) Linear reaction valley

A very simple abstract model PES with one minimum and one TS on a linear reaction channel is obtained by Eq.(

8) given in the appendix, see

Figure 4. On the right hand side we have a dissociation exit. We have in

Figure 4 the level lines (thin black), and some NTs. The red one is a typical case of a slip bond depicted by an NT to

x-direction. The application of a tensile mechanical force,

, in the direction of the red NT to direction

decreases the height of the barrier if

F increases from zero to some value implying an increase of the dissociation rate. At the same time it also decreases the coordinate

x of the TS. As a result, the life time of the slip bond decreases when it is stressed by a tensile force [

47,

48].

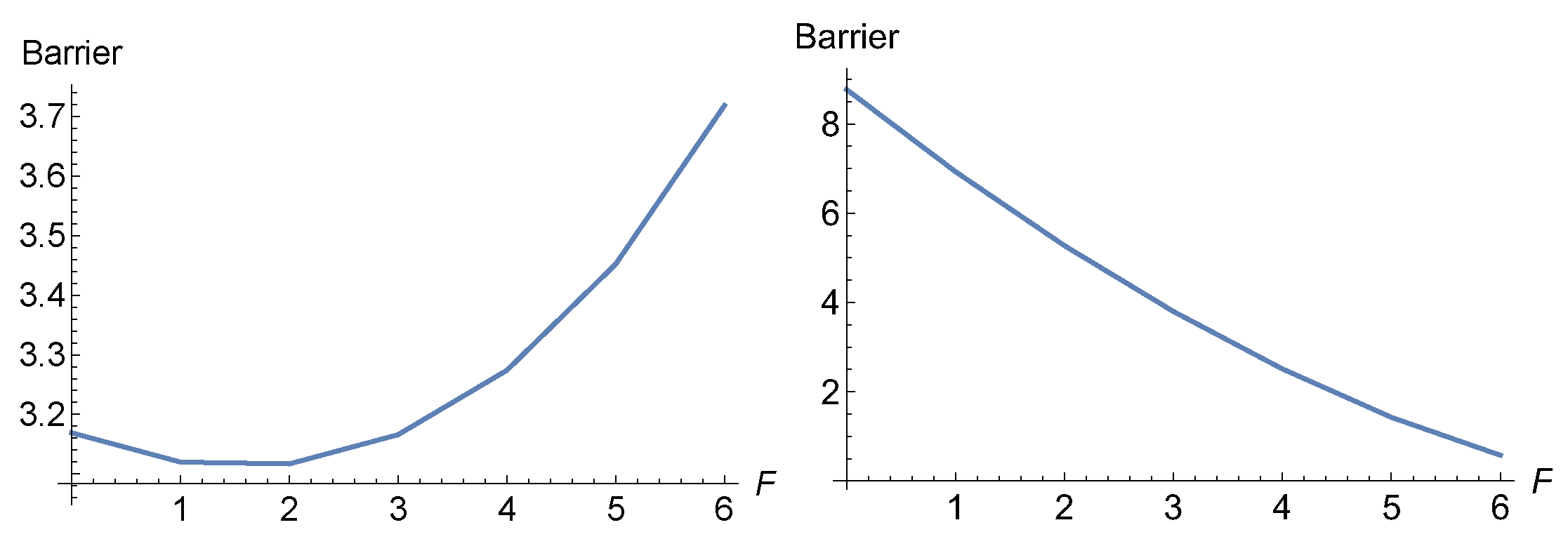

If one uses an excitation in pure

y-direction, (0, 1), then one obtains two branches of the bold dashed NT. Some values for the force

F in this direction are given in

Table 2. A typical increase of the barrier with force takes place at the left hand panel of

Figure 5.

A second condition for an increase of the barrier is here that the curvature at the TS across the reaction channel is larger than the curvature in the reactant into the same direction. The eigenvalue in y-direction in the minimum, R, is 2 but in the TS it is 10.

Again the first condition is that the NT is indeed more or less orthogonal to the reaction valley, to go outside the blue separatrix. It is secured here because additionally the dashed NT is ruptured into two branches; one goes through the minimum but the other one goes through the TS. The border cases are the singular NTs (blue curves) through the VRI points. They depict excitation directions (±1.315, 1), and they form the separatrix. There are two such NTs in our example. Inside the region of these singular NTs between the VRIs are only directions for excitations with slip bond character, like the trivial red NT. The situation changes for the other side of the singular NTs, for the dashed NTs. They are disrupted by the VRI points.

However, if the excitation direction of an NT is too near to the valley direction, though the NT is above the VRI points, then also a slip behavior can be observed; at least for low

F values, see

Figure 5 at the right hand side. The used thinly dashed NT depicts an excitation direction (0.75, 0.64). Additionally here acts the shortening of

x for the thin dashed NT, and the extension of

x for the thick dashed NT, if we leave the TS. This is again the action of the right part of Eq. (2).

One important observation, however, concerns both dashed NTs: they are divided into two branches and go uphill to infinity on the abstract PES. Therefore the moving minimum and the moving TS can never coalesce under the excitation force. It means that they can never end in the usual finale of a slip bond that the barrier disappears. Belyaev and Fedotova [

3] name this an ideal catch bond, in contrast to the realistic catch-slip bond of real molecules.

We have to notice that though the dashed NTs show (from the beginning, or later) an increase in barrier height, they do not show the true character of the realistic catch-slip bond. The possible increase of the barrier in a one-valley model was already reported by Suzuki and Dudko in 2010 [

4]. (We did not understand this in our 2016 paper [

6] where we treated only a slip NT.) However that the possible catch bond NTs in this one-valley model will not come back to a final decrease of the barrier, this means a disturbing insight. It later leads us to the next

Section 3, the two-valley model.

C) Curvilinear reaction valley

This example,

Figure 6, is quite similar to the linear case above. We treat a nonlinear case of the dissociation valley, with a PES model proposed by Suzuki and Dudko [

4], see Eq. (

9) in the Appendix. Coordinates are

. (We have adapted some parameters.) The reactant

R is separated from the unbound state by an SP

1, an SP of index one, located on top of the PES barrier depicted by TS. The long flat minimum valley ends at both sides by dead valleys, but the dissociation exit comes over a side valley, see

Figure 6. The situation is similar to the global minimum of the Müller-Brown surface [

70,

71].

Shown in

Figure 6 are also two (blue) singular NTs which cross two VRI points. They are again the border lines for NTs with slip bond character. All the directions between the two singular NTs are allowed for slip bonds, where the more central NTs, which are like a steepest descent from TS, are of course the better ones. Such `good’ slip NTs do not have a turning point (TP) on their energy profile [

7,

14], however, a TP does not disturb the slip character in the region between the VRI points, see an extreme case in ref. [

6]. This remark contradicts the treatment [

14] where the border for slip bonds is the NT with the first TP.

In

Figure 6 a candidate for a catch bond NT is shown by the black, dashed NT. Its direction is

f=

. It is divided by the singular NTs into two branches. One branch leads from R along the minimum valley in the upper parts of the Figure, but the other part crosses the TS and connects the right ridge with the exit valley to the lower right corner. These branches of this NT describe the movement of the two stationary points, minimum and TS, on the corresponding effective PES if the external force F

f is applied. One branch describes the movement of the minimum, but the other branch describes the movement of the TS. The external force now increases the difference of the energy between minimum and SP

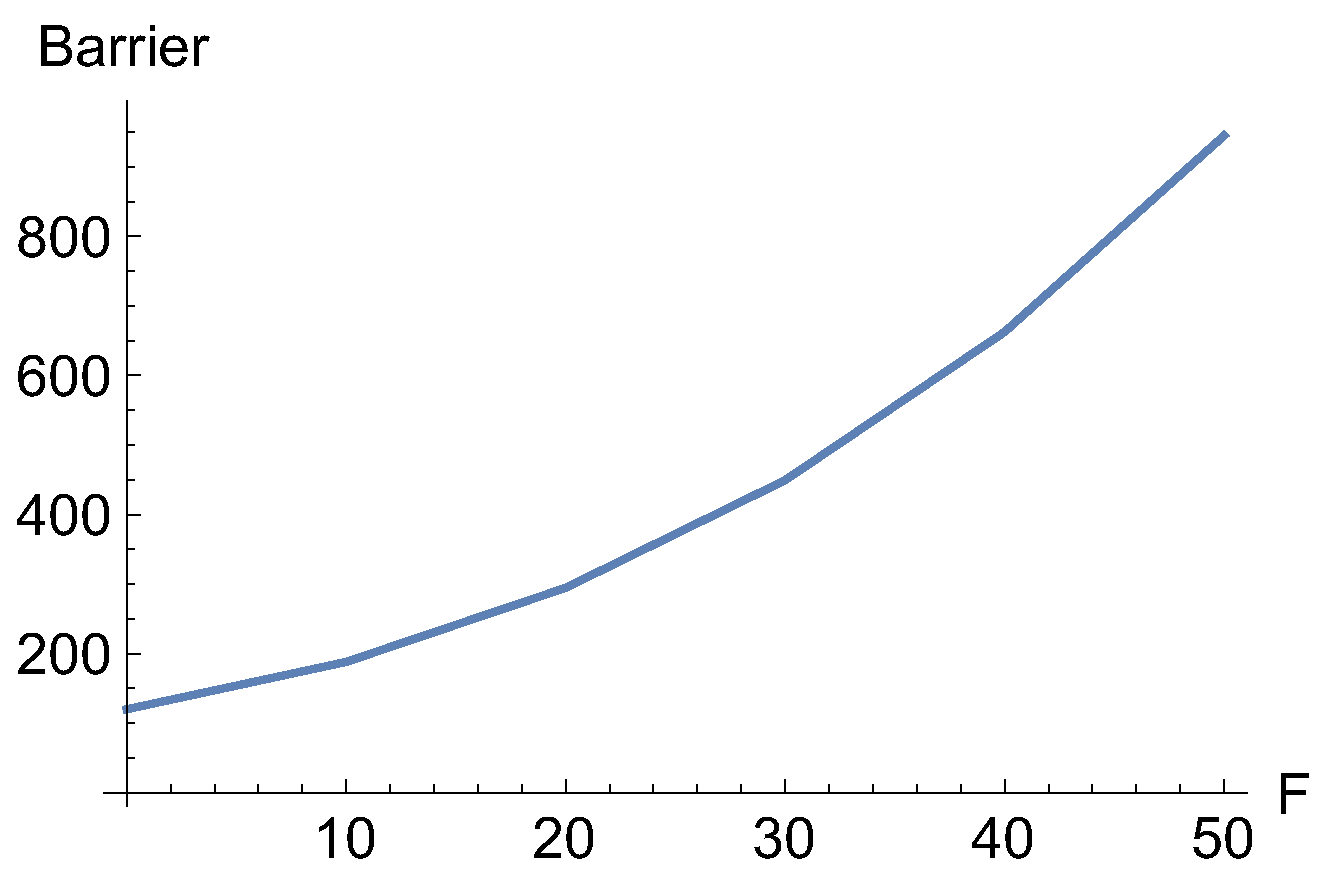

1. The reaction rate will decrease. In this example the effect is dramatic, see

Figure 7.

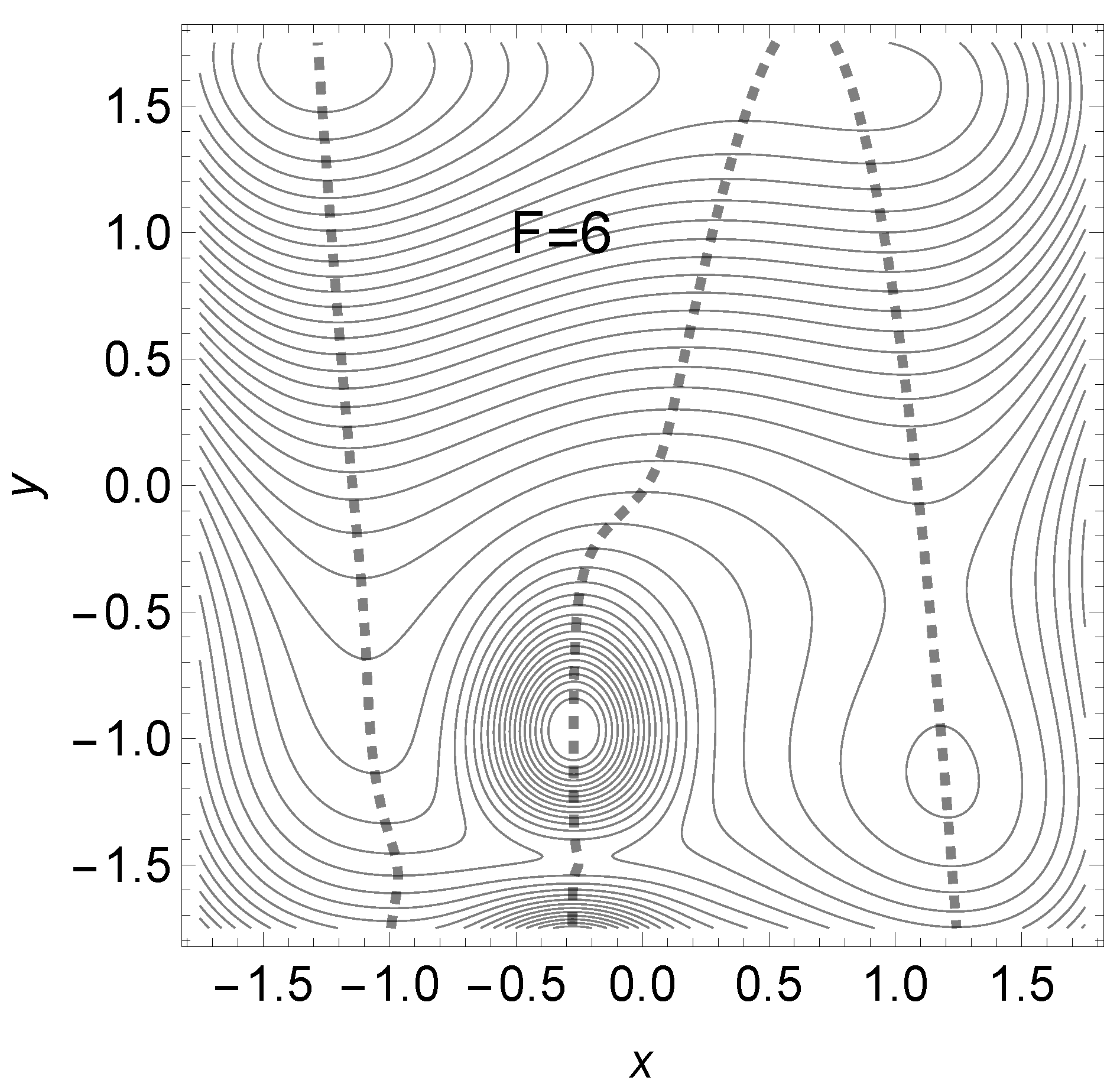

Although we have a dramatic increase of the barrier height of the example of

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 we cannot say that it shows true realistic catch bond character, because it does not turn back after a certain amount of force,

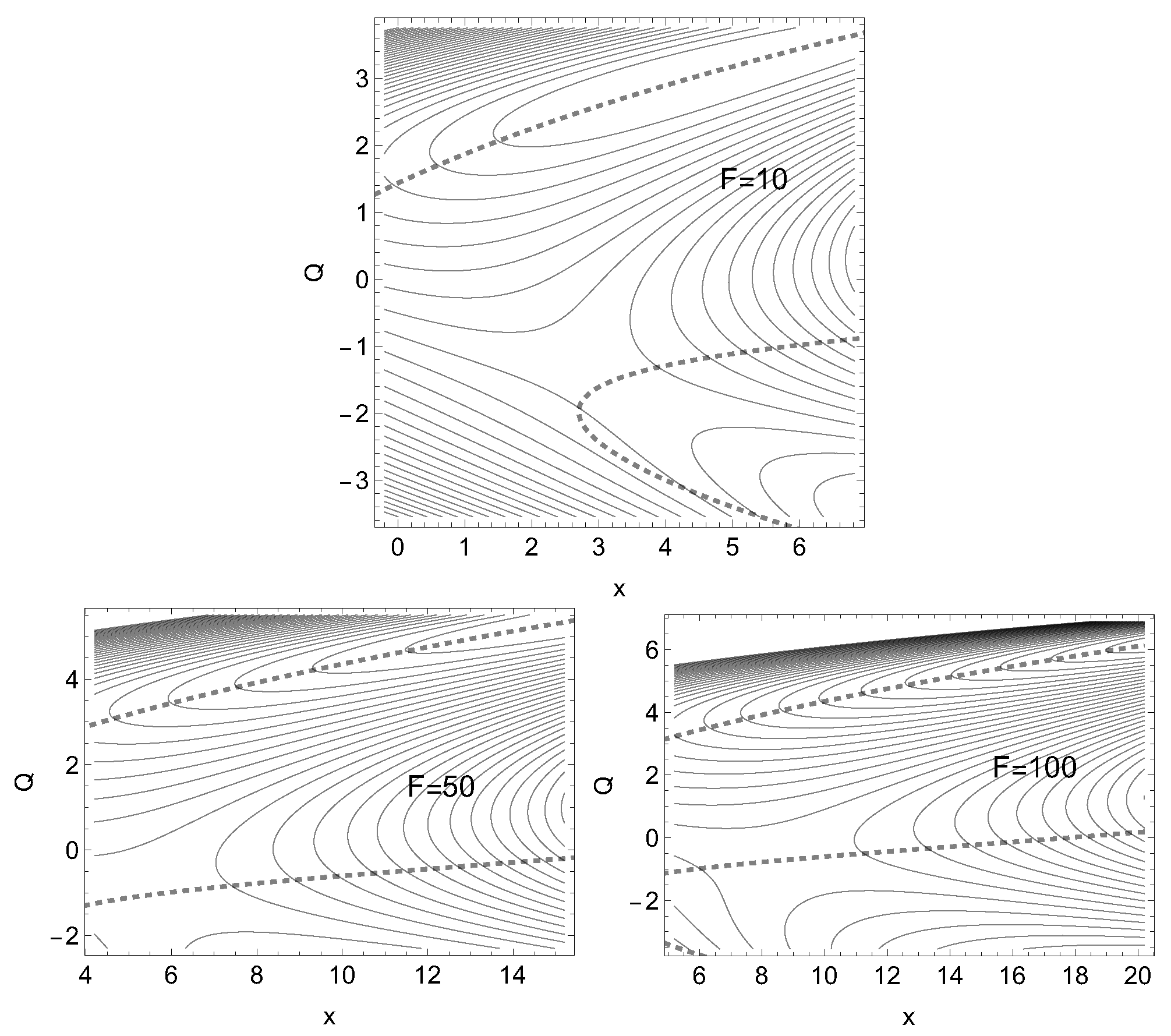

F. The two branches of the dashed NT never cross. They cannot allow the minimum and the TS to coalesce. It seems that the character of a one-valley minimum with one exit to dissociate, is too little to allow a true catch bond behavior. Different cases of the effective PES are shown in

Figure 8.

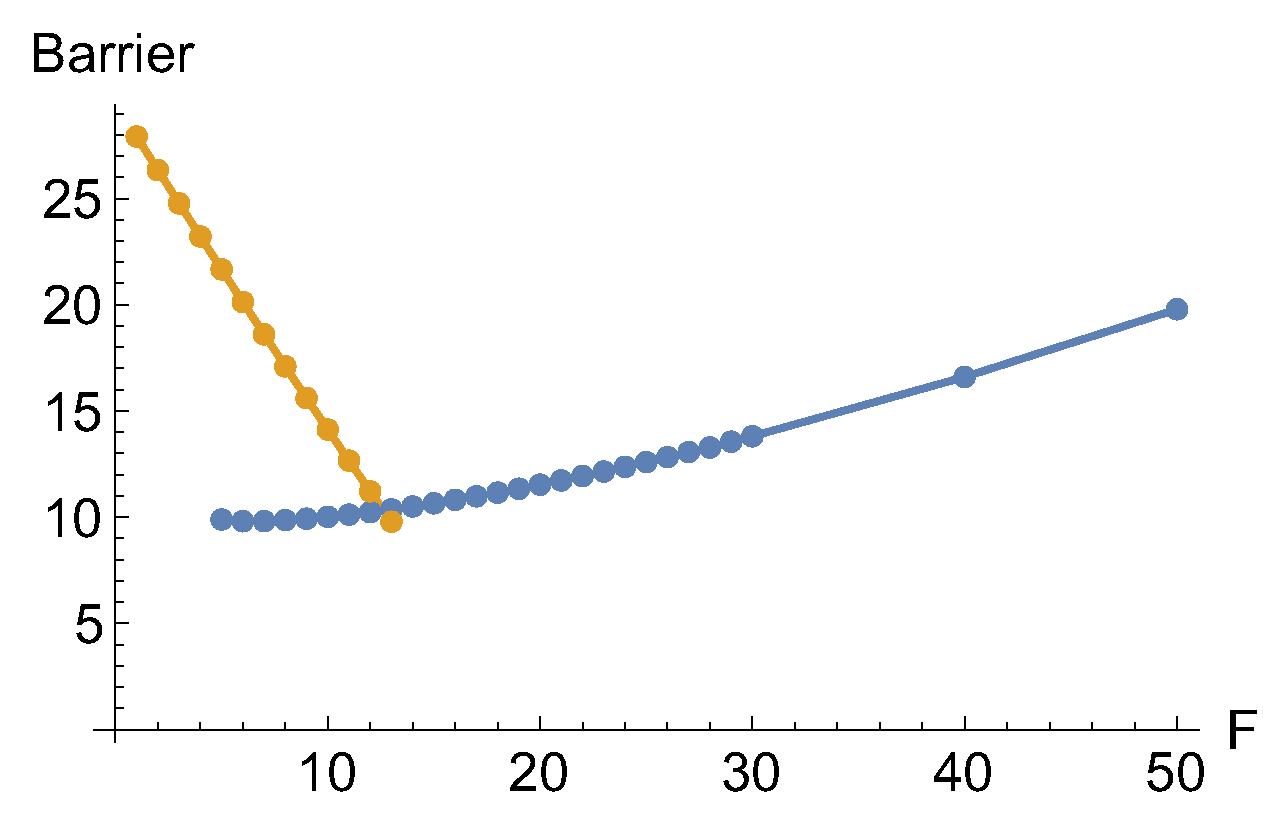

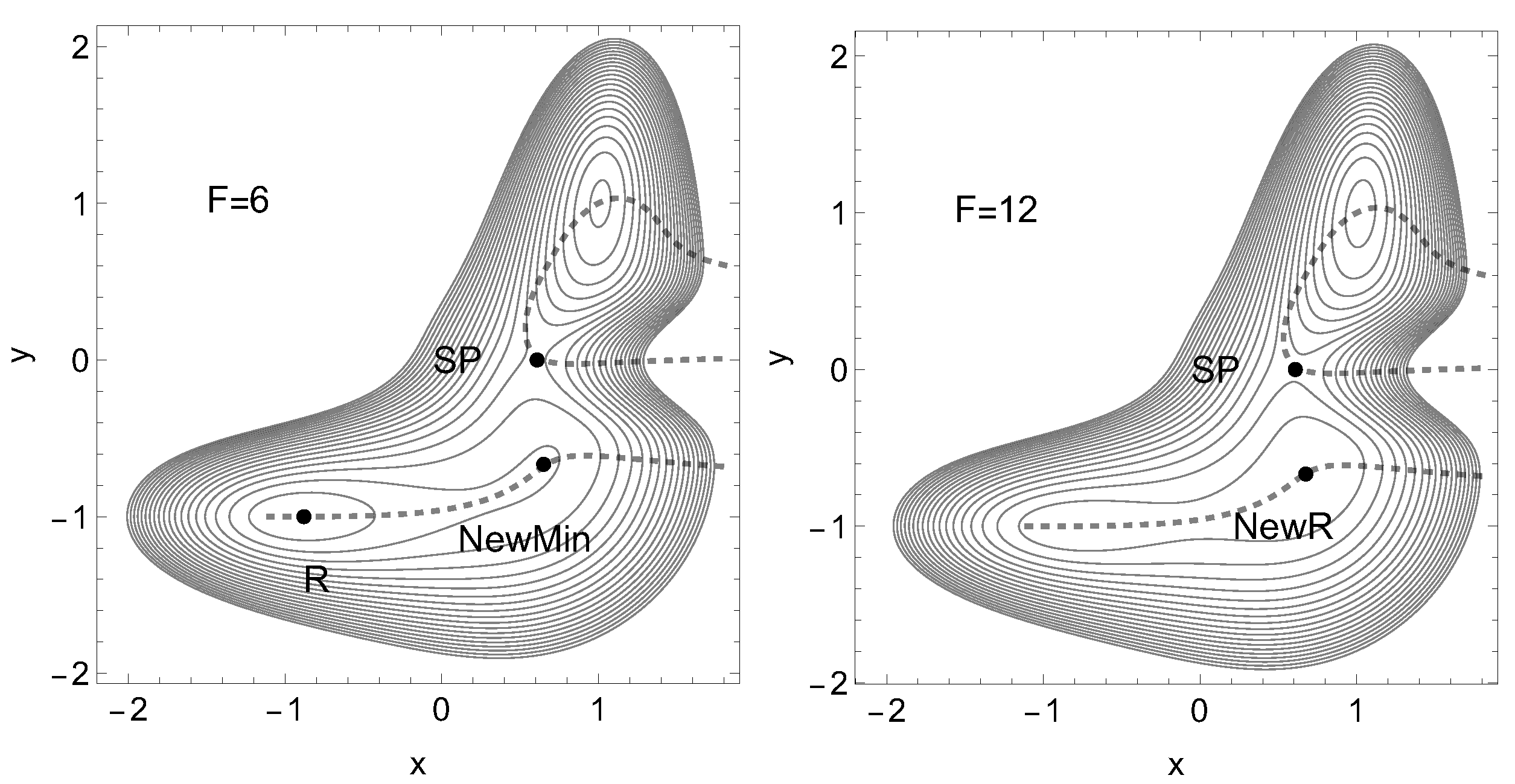

D) Curvilinear reaction valley with an emerging shoulder

We use a PES,

Figure 9, along Eq.(

10). Now we find a reactant, R, an SP, and a product minimum, P. The key for our treatment is again the narrowness of the col. The red curve is again an NT leading from the reactant, R, over the SP to the product, P. Its direction is

. The blue NT is a singular NT through the VRI point, with the direction

, and the black dashed NT is a putative catch bond NT. The force for this NT is assumed in

x-direction. The green curve is the line of points with condition

for the Hessian matrix. It crosses the reaction valley from the minimum to the TS three times. This property will lead to an interesting behavior of the PES under external force in

x-direction: in the long, gently rising valley of the reactant, R, emerges under

units of force a further minimum. It replaces the former shoulder, before the TS. So to say, a population of states of the former global minimum splits into a bimodal population for some time, as it is reported in ref. [

72].

At the beginning of such a force we get a slip bond behavior between the reactant and the TS. But at F=12 units the new minimum becomes the global one, and its relation to the TS now turns to catch bond behavior. The corresponding stationary points of the effective surfaces are given in

Table 4.

In

Figure 10 we report the barrier height between the two minima and the TS under different forces, F. The dark yellow line concerns the original minimum, but the blue curve of points shows the difference to the new one.

In

Figure 11 we report the two effective PES under different forces, F. The emergence of the new minimum is to detect.

A condition for the catch bond character was that the corresponding curvatures in NT direction are both positive, but the one at the TS should be larger than that one of the minimum. Here we have the eigenvalues of the Hessian in the minimum by (80, 402) and at the TS by (307, -157). In a contrary case the difference of both energies will decrease and the catch bond character does not appear.

In all three cases B) to D) of different mathematical test PES we obtain a desirable increase of the barrier under a corresponding external force. However, it happens along disrupted NTs (the dashed ones) which go up to infinity on the simple PES, so that a final decrease of the barrier can never take place. These NTs cannot be correct models for the observed behavior in Mechano-Bio-Chemistry namely the final catch-to-slip behavior of the reported experiments [

73].

E) Platelet selectin

The proposed 2D surface [

5] for platelet selectin (P-selectin) [

46,

68,

74,

75] has in the

F=0-case already a flat shoulder, see

Figure 12. It is the former Int-minimum of the L-selectin case of

Figure 2. However, there is now no additional

minimum to

R, and there is only one main valley from

R to dissociation, like in the case of E-selectin in Fugure 1. The situation is characterized by a disappearance of the VRI points on the PES. The (blue) quasi-singular NT to direction (0, 1) does not cross the

axis at the shoulder. The dashed NT leads from

R to the TS of the dissociation, and it depicts like in the E-selectin case a pure slip bond. Because from the beginning for any small

F-value, the shoulder disappears. This PES model cannot represent catch bond behavior.

Summary of subsection 2.2

In this subsection we studied different models:

The case A) of L-selectin,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, allows a true catch bond property. The next cases B) to D) show the catch bond behavior, however, they do not come back finally to the chemical slip behavior. So they can be seen for abstract models where for real molecules the border properties have still to be changed. The case E) reports a putative catch bond from the literature which is, however, only a slip bond.