1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GB) is the most common and aggressive type of highly malignant primary brain tumor that primarily occurs in adults. By cell origin it is currently classified as astrocytomas (grades I–IV), oligodendrogliomas, or wild-type glioblastomas [

1]. GB exhibits substantial heterogeneity at the cytopathological, transcriptomic, and genomic levels. Its aggressive nature is attributed to uncontrolled cellular proliferation, resistance to programmed cell death (apoptosis), heightened angiogenesis, progressive infiltration into the surrounding healthy brain tissue, and genomic instability.

Neurosurgery is one of the critical steps in GB therapy, its subtotal resection is highly important. Accurate delineating the true tumor boundaries is challenging due to GB diffusely infiltrative nature. Moreover, the extent of brain involvement as visualized through contrast enhancement merely represents a macroscopic view and does not reveal the complete magnitude of tumor invasion [

2]. To enhance patient survival rates and minimize tumor recurrence, it is imperative to meticulously excise all malignant cells dispersed within healthy tissue, distant from the primary tumor focus, during surgical interventions.

A method of intraoperative visualization has been proposed to accurately determine the localization of tumor cells, which can provide real-time visualization of neoplasms using specific or non-specific fluorescent dyes and a surgical fluorescent microscope. One of the most commonly used substances that can passively accumulate in tumor tissue is indocyanine green (760-820 nm), which has been utilized in neurosurgery since 2003 for intraoperative assessment of aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, and cortical perfusion [

3]. Despite its wide application and proven effectiveness, drugs that passively accumulate in tissues have significant drawbacks [

4], such as:

1) The non-specific cellular uptake of the drug can result in areas of tissue with increased metabolism (e.g., inflammatory foci, edema zones) emitting fluorescence similar to that of tumor tissue.

2) Due to the angiogenesis and vascularization of solid tumors, which lead to the proliferation and entanglement of blood vessels, the access of the drug to cancer cells may be hindered, resulting in them remaining unstained.

To overcome the aforementioned issues, non-specific fluorophores should be conjugated with tumor-specific ligands such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers [

4,

5].

Analysis of scientific literature and products undergoing preclinical and clinical trials has revealed a wide array of agents for intraoperative tumor visualization based on infrared (IR) fluorophores conjugated with monoclonal antibodies. One such agent is Cetuximab-IRDye800CW (NCT02855086), which combines the IR dye IRDye800CW, FDA-recommended, with an antibody against human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

EGFR/ErbB-1/HER1 is a transmembrane protein belonging to the ErbB receptor family, increased expression of which is observed in various types of cancers such as glioblastoma, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [

6]. Cetuximab-800CW has been tested on nine HNSCC patients (NCT01987375) and is currently in phase I/II clinical trials for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, malignant gliomas, and HNSCC (NCT02736578, NCT02855086, NCT03134846). Another IR fluorophore, BLZ-100, based on a chlorotoxin peptide specific to annexin A2, is in the early stages of clinical trials [

7].

The key advantage of monoclonal antibodies is their high specificity towards target cells, minimizing damage to healthy cells and resulting in fewer side effects compared to traditional pharmaceutical drugs. However, antibodies also have some drawbacks [

8]. For instance, the crystallizable fragment of antibodies can interact with Fc receptors expressed on the surface of various cell types, increasing their cross-reactivity and promoting retention in the bloodstream. Other limitations are associated with the complexity of production, as therapeutic antibodies require large-scale mammalian cell culture and subsequent stringent purification under good manufacturing practices. Furthermore, monoclonal antibodies developed in animals need to be specially prepared for administration into the human body in clinical settings. In addition, antibodies have a short shelf life and although they can be chemically modified, site-specific modifications are extremely difficult [

9,

10].

These constraints have led to the development of molecular constructs that are characterized by ease of production, chemical synthesis, and modification. Aptamers, small (5-30 kDa) single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules, carry a nucleotide-based code in their primary sequence, allowing for easy synthesis and modification. They fold into unique three-dimensional structures, exhibiting high affinity for targets and can be used for inhibiting or activating specific proteins. Aptamers are often referred to as "synthetic antibodies", but in many aspects, they surpass antibodies in the following aspects [

11]:

1) Synthesis costs of aptamers are 1000 times lower than obtaining antibodies;

2) Aptamers are easily synthesized and modified;

3) Aptamers are low immunogenic and low toxic;

4) Small size allows better tissue penetration and clearance from the body.

Aptamers offer a promising alternative to antibodies, with advantages in terms of synthesis, modification, immunogenicity, and toxicity, making them a valuable tool for various applications in biotechnology and medicine. Currently, specific near-infrared dyes based on antibodies and peptides are emerging for intraoperative diagnosis of glioblastoma. However, as of today, there is still no aptamer-based agent available worldwide for intraoperative visualization of glioblastoma.

The study demonstrates the potential use of Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L aptamers, as well as an analog (indocyanine green spectral equivalent) Cyanin 7.5 (Cy 7.5) fluorophore, for postoperative tissue and animal model imaging. Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L aptamers were obtained by improving the tertiary structure of the published Gli-233 and Gli-55 aptamers targeting alpha-tubulin and GFAB proteins [

5]. It was shown that the generated aptamers exhibit higher affinity compared to the previous ones. Model experiments were conducted using Cy 7.5-labeled aptamers on postoperative tissues and animal models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Molecular modeling

Secondary structures of the aptamers were predicted using the mFold [

12] program taking into account such experimental parameters as folding temperature and the presence of ions in the solution. Tertiary structures of the aptamers were modeled with SimRNA [

13] and VMD programs [

14,

15]. Molecular dynamic simulations of 200 ns were carried out using the GROMACS 2019.8 package [

16]. The Amber14sb force field [

17] and the TIP3P model [

18] for water were used for simulations. The aptamer was solvated in a periodic cubic box of water. The negative charge of the aptamers was neutralized with Na

+ ions. Additional Na

+ and Cl

– ions were placed to the system to reach the concentration 0.15 M. MD simulations were performed with the NPT (at constant number of particles N, pressure P, and temperature T) ensemble at 310 K and 1 atmosphere (atm) using the velocity-rescaling thermostat [

19] and at 1 bar pressure using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat [

20].The clustering analysis of the obtained trajectories was performed using the quality threshold algorithm implemented in VMD program [

21].

2.2. Patient-derived tumor samples

The research we conducted obtained ethical approval from the Local Committee on Ethics in Krasnoyarsk Inter-District Ambulance Hospital named after N.S. Karpovich, Krasnoyarsk, Russia (Approval #20/11/2016). To collect tumor tissues, we selected patients with glioma who had previously undergone complete curative resection of their disease at Krasnoyarsk Inter-District Ambulance Hospital named after N.S. Karpovich. Prior to obtaining the specimens, written informed consent was obtained from all patients, ensuring their commitment to participate in the study. The solid tumors were handled with utmost care, maintaining aseptic conditions, and immediately placed in ice-cold colorless DMEM medium supplemented with 1000 U mL-1 penicillin G and 1000 mg L-1 streptomycin. The samples were then transported on ice to the laboratory within 2-4 hours after resection to ensure their viability and optimal condition for subsequent analysis.

2.3. Cell isolation and culturing

Primary cultures of human brain tumor or breast cancer were obtained from postoperative material. The tumor tissues after surgical resections were placed in a sterile 15 ml Falcon tube with 5 ml of cold Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 10% antibiotic-antimycotic.

In a laminar flow hood, the excess Hank's solution was removed from the tube containing the glial tumor by dispenser. The tissues were washed three times with 5 ml of cold DPBS to remove blood cells, and transferred to a Petri dish filled with 1-2 ml of cold DPBS. Necrotic tissues and blood clots were removed using forceps and a scalpel blade. The remaining tissues were minced into 1mm3 pieces and placed in culture flasks with a nutrient medium for spheroid formation (for glial cells only) or minced into a suspension and filtered through a 70-micron cell strainer into a sterile 15 ml centrifuge tube, followed by twice washing by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes with DPBS.

The resulting pellet suspended in 2 ml DPBS, was layered on Lymphocytes Separation Media (3 ml) and centrifuged 10 min at 2000 rpm. Thereafter a “cloud” of cells at the border of Lymphocytes Separation Media and DPBS was collected and transferred to a sterile tube with DPBS followed by centrifugation for 5 min 2000 rpm. The pellet was transferred to a culture flask or with nutrient medium. Cultivation was maintained in a 5% atmosphere of CO2 and 37⁰С.

To remove cells, the culture was washed with DPBS without Ca2+, Mg2+, then poured by 3-5 ml of fresh DPBS solution and hold for 2-3 minutes. The cells were removed with a jet of solution using a dispenser. To separate the attached cells, 2-4 ml of Versen's solution was poured into the flasks and incubated for 5-15 minutes. Next cell suspension was centrifuged for 3 minutes at 2500 rpm and washed with DPBS containing Ca2+, Mg2+.

2.4. Flow cytometric aptamer affinity analysis

The affinity of aptamers was measured by flow cytometry using an FC-500 Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., USA). The data were analyzed with help of Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter Inc., USA). Briefly, cultured glioma or breast cancer cells were incubated with yeast RNA (1 ng µL-1) in 300 µL of DPBS for 30 minutes at room temperature in a shaker to reduce nonspecific binding. Thereafter the samples incubated with 20 nM of FAM-labeled aptamers or FAM-ssDNA library or FAM-AG40 as a control for 30 minutes at room temperature in a shaker.

2.5. Staining of postoperative glioblastoma tissues

Staining of postoperative glioblastoma tissues was performed using Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L Cy 7.5-labeled aptamers.

At first, the glioma tissues were obtained from surgical resection washed with a phosphate buffer and treated by aptamers. Thereafter the tissues were incubated for 5 minutes and analyzed using a fluorescent operative microscope, Zeiss Kinevo 900 (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The data analyzed by ZEN 2011 (Carl Zeiss).

2.6. Orthotopic xenotransplantation of human glial tumors

This study was conducted in strict accordance with the National Institute of Health Guidelines’ recommendations for the care and use of laboratory animals. The protocol was approved by the Local Committee on the Ethics of Experiments on Animals of the Krasnoyarsk State Medical University (number #95/2020 from January 29, 2020). All operations were performed under anesthesia, and every effort was made to minimize the animals’ sufferings.

2.6.1. Mice model

Laboratory female ICR mice, weighing 20-25g were maintained in sterile individually-ventilated cages. Mice were immunosuppressed using cyclosporine (20 mg/kg subcutaneously), cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg subcutaneously) and ketoconazole (10 mg/kg orally) 7 days before and 2 days after transplantation [

22].

Under the inhalation anesthesia mice hair were removed with hair removal cream, the skin was dissected in a sterile condition, and the cranial window was made using electro trypan. The formation of human astrocytoma model carried out by intracranial injection of primary patient-derived cell cultures. One 1 mm neurosphere and 106 tumor stroma cells in 6 µL of the hydrogel medium (GrowDex/DMEM, 1:1) were placed into a Hamilton syringe between 2 µL of hydrogel medium (GrowDex/DMEM, 2:1). Tumor cells were inoculated into the mice brain through the 2 mm cranial window, the puncture was covered with 5 µL of hydrogel medium (GrowDex/DMEM, 2:1) and the skin incision was sutured.

2.6.2. Rabbit model

The work was performed on 4 male rabbits (silver breed), weighing 1800-2000 g, with a health certificate. Rabbits were immunosuppressed with cyclosporine (20 mg/kg intramuscularly), cyclophosphamide (20 mg/kg intramuscularly), and ketoconazole (5 mg/kg orally with water) every second day for 21 days before and 2 days after tumor transplantation. Anesthesia in rabbits was carried out with a single intravenous injection of Zoletil-100® solution (manufactured by Virbac, France) at the rate of 0.05 ml per 1 kg of body weight of the experimental animal in combination with the drug Xylavet (manufactured in Hungary) at the rate of 0.15 ml per 1 kg of weight body of an experimental animal. Intravenous administration of drugs in rabbits was carried out after catheterization of the veins on the dorsal surface of the ear with a 24G catheter (mainly the large ear vein was used for catheterization). After reaching the stage of surgical anesthesia, hair was removed from the rabbits using shaving cream, the skin was dissected in the area of the sagittal cross (or temporal line), which must be confirmed with doctors under sterile conditions, and 2 cranial windows with a diameter of 3 mm were made using an electrotripan. The formation of a human astrocytoma model was carried out by stereotactic transplantation into the right and left hemispheres of the brain of primary cell cultures of a patient with a glial brain tumor (2×106 cells and 5 neurospheres in 40 μl of GrowDex/DMEM medium (1:1)) using a syringe Hamilton with a volume of 40 µl into each cranial window with a diameter of 3 mm. The injection site was covered with skin and sutures were placed. To avoid the development of a bacterial infection, the animals were intravenously administered the antibacterial drug “Tylosin 50” (manufactured by Nita-Pharm, Russia) within three days after surgery.

2.7. In vivo fluorescence visualization of IR-Glint in mice

To determine the optimal strategy for administering the IR-Glint, we used healthy mice and mice with human orthotopically transplanted glioblastoma.

IR-Glint was administered to healthy mice, healthy mice with trepanation hole of the skull, and mice with transplanted glioblastoma by intravenous injection or surface application. IR fluorescence of in mice was evaluated using Fluor i In Vivo imaging system (South Korea) under inhalation anesthesia.

2.8. FGS modeling

Glioblastoma staining in mice was performed by two ways: intravenous injection or direct staining by spraying of 5µM mixed Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L with Cy 7.5 label. In the first case, 200 µL of aptamers were injected into a tail vein 30 minutes before brain removal. In the second case 200 µL of aptamers powered on mouse brain under anesthesia and incubated for 3 minutes.

Mice organs were put in 10% formalin and then analyzed with the help of an operative microscope Zeiss Kinevo 900 (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Intraoperative staining of the glioma in rabbits was performed using pooled Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L labeled with Cy7.5 (IR-Glint) at a concentration of 5 μM. Anesthesia was induced using zoletil and xylazine. After the surgery and staining, an excess amount of zoletil was administered to the animal and the brain was removed. The tissues were fixed in 10% neutral formalin and then analyzed using the surgical fluorescence microscope Zeiss Kinevo 900 (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

2.9. Toxicity testing of aptamers in mice

To determine toxicity, changes in cholesterol, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, total protein, and alpha-amylase evaluated.

Hepatotoxicity assessment was carried out in healthy male and female mice injected with 200 ml of 5 μM IR-Glint into tail veins.

One week after the injection blood harvested and submitted to a clinical laboratory for the analysis.

2.10. In vivo visualization of human glioblastoma xenotransplantation in a rabbit using PET/CT

Tumor location in rabbits monitored using PET/CT. Rabbits were injected into an ear vein with 11C methionine 40 minutes before visualization. The animals were immobilized using a single intravenous injection of Zoletil-100® solution (manufactured by Virbac, France) at the rate of 0.05 ml per 1 kg of body weight of the experimental animal in combination with the drug Xylavet (manufactured in Hungary) at the rate of 0.15 ml per 1 kg of weight body of an experimental animal. PET/CT scanning performed using Discovery PET/CT 600 scanner (General Electric, USA). Data were analyzed using PET VV software at an AW Volume Share 5 workstation and Hounsfield densitometry scale.

2.11. Histological and confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis of tissues

Human postoperative tissues were incubated with 1 ng mL-1 yeast RNA for 30 minutes on a shaker. Thereafter it was washed by two times and incubated with 50nM FAM-labeled Gli-233nt or Gli-55_3L for 30 minutes on a shaker and fixed at 10% buffered formalin solution. The volume of a fixative was 10 times greater than the size of the immersed tissue. The samples subjected to a standard histological treatment based on isopropyl alcohol with further paraffin impregnation. Sections made from paraffin blocks were applied to positively charged adhesive glasses. One part of sections left for confocal microscopy analysis without additional staining; the next one stained with hematoxylin and eosin dyes to confirm tissue morphology.

Histological tissue sections of mice and rabbit brain were fixed in formalin solution stained with hematoxylin and eosin dyes to confirm tissue morphology.

A Nexcope NIB900 (Ningbo Yongxin Optics Co., Ltd., China) and LSM 780 NLO Confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) were used for confocal imaging; images were processed with ZEN2 software.

2.12. Statistical Analyses

Blood serum biochemical parameters were compared using ANOVA. A two-tailed t test was used to compare group means. Bonferroni correction was applied to p values. The differences were considered significant at a level of significance of p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Modification of Gli-233 and Gli-35 aptamers

Previously we reported Gli-233 and Gli-55 aptamers [

5] that selectively bind glial tumos. The secondary and tertiary structure of of this aptamers have been obtained using the combination of Small Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) and molecular modeling. Gli-233 has a “hairpin” shape with rather big single stranded loop maintained by five base pairs. Taking into account the size of the loop and helix parts, four nucleotides at the 5’ end was considered as non-essential for both biding and structure maintaining functions. Moreover, the more nucleotides, the more options of aptamer folding. In order to avoid the formation of other undesirable structures of the Gli-233, two modified options of the aptamer were proposed. Single stranded part at the 5’ end was removed. To enhance the stability of the aptamer structure in the solution, one base pair was added. Thus, two aptamers Gli-233nt and Gli-233-2 were modeled. The secondary and the tertiary structures of the aptamers are presented in

Figure 1 B, C.

Aptamer Gli-55 consists of 60 nucleotides (

Figure 1 D). Thus, there is a need to reduce a number of nucleotides of this aptamer considering a cost of the synthesis and a future possibility of using this aptamer as a part of a new bi- or multivalent aptamer. In the case of Gli-55, a decrease in the number of nucleotides leads to formation a secondary structure which consists of three stemloops (

Figure 1 E). As nucleotides are removed from the 5’ end, two stemloops at 3’ end remain unchanged. Therefore, two truncated options of Gli-55 with three (Gli-55_3L) and two stemloops (Gli-55_3L) were modeled (

Figure 1 E, F).

For all new aptamers molecular dynamic simulations were carried out to imitate in vitro environment: solvent, temperature, and presence of the ions. Tertiary structures of the aptamers obtained as a result of clustering analysis of 200 ns MD trajectories represents structure of the aptamers in the solution and are shown in

Figure 1.

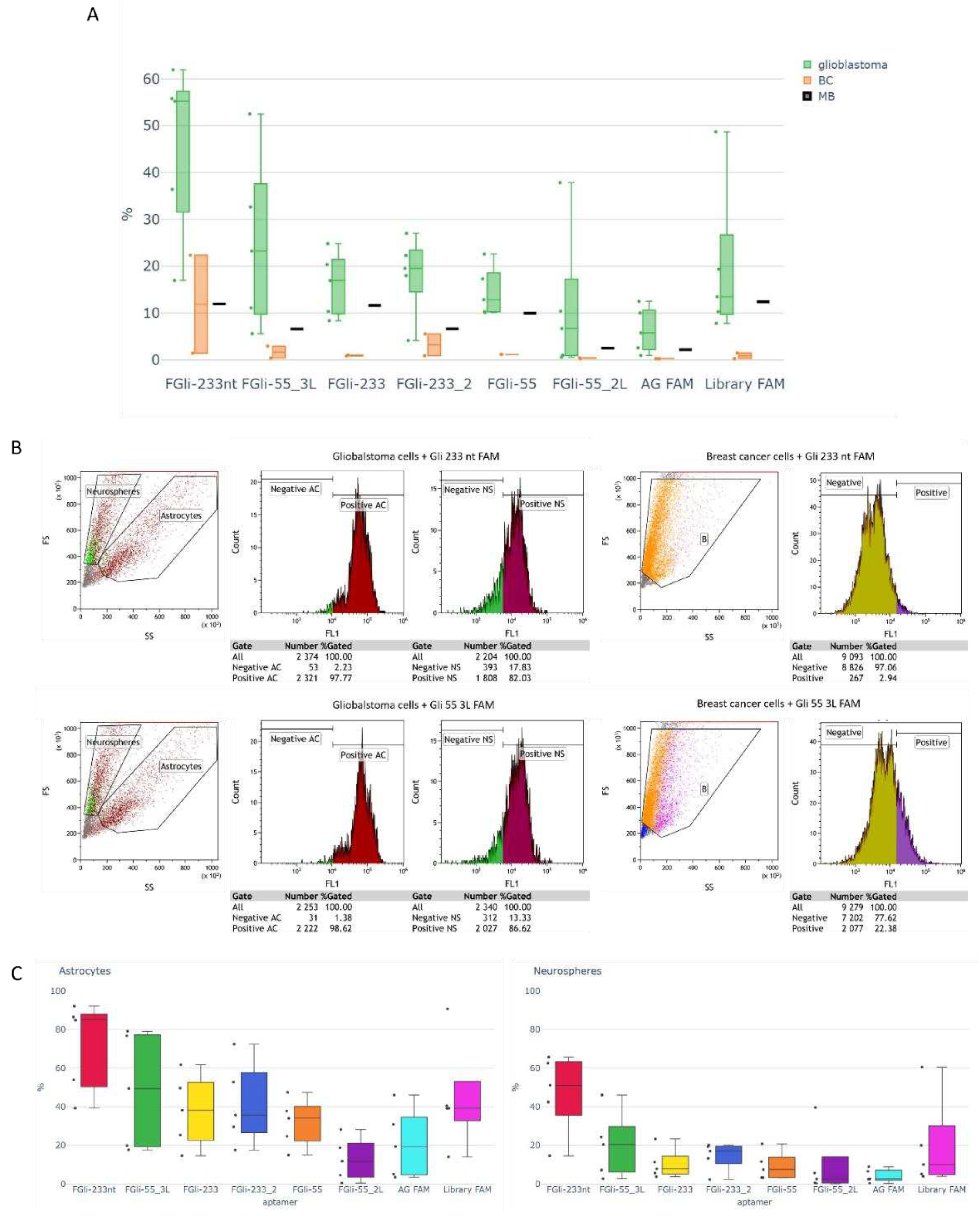

3.2. Flow cytometric aptamer affinity analysis

The binding of Gli-233, Gli-233nt, Gli-233_2, Gli-55, Gli-55_3L, and Gli-55_2L aptamers was evaluated using flow cytometry. Cultures derived from glioblastoma tissues, breast cancer, and cells isolated from the brain of a healthy mouse were used for verification. As shown in the figure, glioblastoma cells obtained from the cultures consisted of two types: astrocytes and neurospheres, which are clusters of neural stem cells that are larger in size. In all cases, the aptamers exhibited better binding to astrocytes than to neurospheres, although binding to neurospheres was also observed.

In breast cancer cells, as well as in cells isolated from the brain of a healthy mouse, the scattering diagram showed a uniform distribution.

Figure 2A illustrates the flow cytometry analysis of Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L aptamers as an example.

Figure 2B represents the corresponding histograms obtained for Gli-233 and Gli-55 aptamers, along with their modified versions. The obtained data shows that Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L aptamers exhibited a higher binding percentage to glioblastoma cells, as well as a lower binding percentage to breast cancer cells and cells isolated from the brain of a healthy mouse, compared to the other aptamers. As a result, Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L aptamers were selected for further experiments and the development of a Cy 7.5-based spray for intraoperative staining.

3.3. Evaluation of aptamer binding ex vivo

In comparison with histological hematoxylin and eosin analysis, it has been demonstrated that the designed aptamers bind specifically to glial tumors in tissue samples isolated from glioblastoma multiforme during surgical resection. FAM-labeled Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L, at a concentration of 50 nM, were pooled together (FAM-Glint) and used to stain the tissues

ex vivo. Histological analysis demonstrated that FAM-Glint indeed stained glial tumors (

Figure 3A, B), compared to the FAM-non-specific oligonucleotide, which did not stain (

Figure 3C) the brain tumor tissues. The aptamers specifically bind to glial tumor cells, as shown by the distinct staining pattern of the glioblastoma multiform region (

Figure 3A), as well as the sarcomatoid region of the glial tumor (

Figure 3B) can be clearly observed. Overall, these results demonstrate the specific binding capabilities of the aptamers to glial tumor cells in glioblastoma tissues, as confirmed by both FAM-Glint staining and H&E analysis. This concentration was sufficient for confocal microscopy. However, for

ex vivo and

in vivo tissue staining, the concentration needs to be adjusted.

The optimal concentration of the IR-Glint for fluorescent-guided surgery was evaluated on-site using a fluorescent surgical microscope.

Figure S1A shows IR-Glint at 0 µM (

Figure S1A1), 1 µM (

Figure S1A2), and 2 µM (

Figure S1A3) in a tube, which was diluted in DPBS. As seen in the images, both concentrations are visible under the IR fluorescent module of the surgical microscope. To determine the optimal concentration for specific visual guidance during tumor surgery, freshly resected glioblastoma tissues were stained with individual aptamers Cy7.5 labeled Gli-233nt and Gli-55 (

Figure S1B) or IR-Glint at various concentrations (

Figure 4). The optimal concentration of IR-Glint was found to be 5 µM.

3.4. FGS modeling at mice

The main goal of the FGS modeling experiment was to choose a strategy for administering the IR-Glint: intravenous injection or surface application. Surface application allows for a reduction in drug dose usage and potential toxic effects on the patient, as well as a decreased risk of oligonucleotide degradation in the blood due to nucleases. Intravenous administration allows for the staining of the entire tumor site just before surgery, which can assist the surgeon. However, there is a risk that the drug may not cross the blood-brain barrier.

To determine the optimal strategy for administering the IR-Glint, we used healthy mice and mice with human orthotopically transplanted glioblastoma.

The time of aptamers circulatin in blood was evaluated on healthy mice with intravenous injection and subcutaneous injection (

Figure S2) near the trepanation hole of the skull (

Figure S3).

IR fluorescence of IR-Glint in mice was evaluated using the Fluor i In Vivo imaging system (South Korea). Prior to injection, the mice did not show any background IR fluorescence (

Figure S2A). Five minutes after the tail vein injection, the bodies of the mice also did not emit enough fluorescence (

Figure S2B). However, after 40 minutes, IR-Glint distributed all around the body (

Figure S2C). Ninety minutes after injection, the dye became visible in the abdominal cavity (

Figure S2D), and it can be seen that IR-Glint accumulates in the liver, gallbladder, kidneys, and intestines (

Figure S2F). After 24 hours, residual fluorescence was visualized only in the tail in case a vein bursts during the injection (

Figure S2E).

Intracranially applied IR-Glint is visualized in the head at the site of inoculation for at least 90 minutes (

Figure S3 A-C). It is also metabolized in the liver and spleen, filtered through the kidneys, and excreted through the intestines. After 2 hours, it can still be seen in the brain at the site of application (

Figure S3 D).

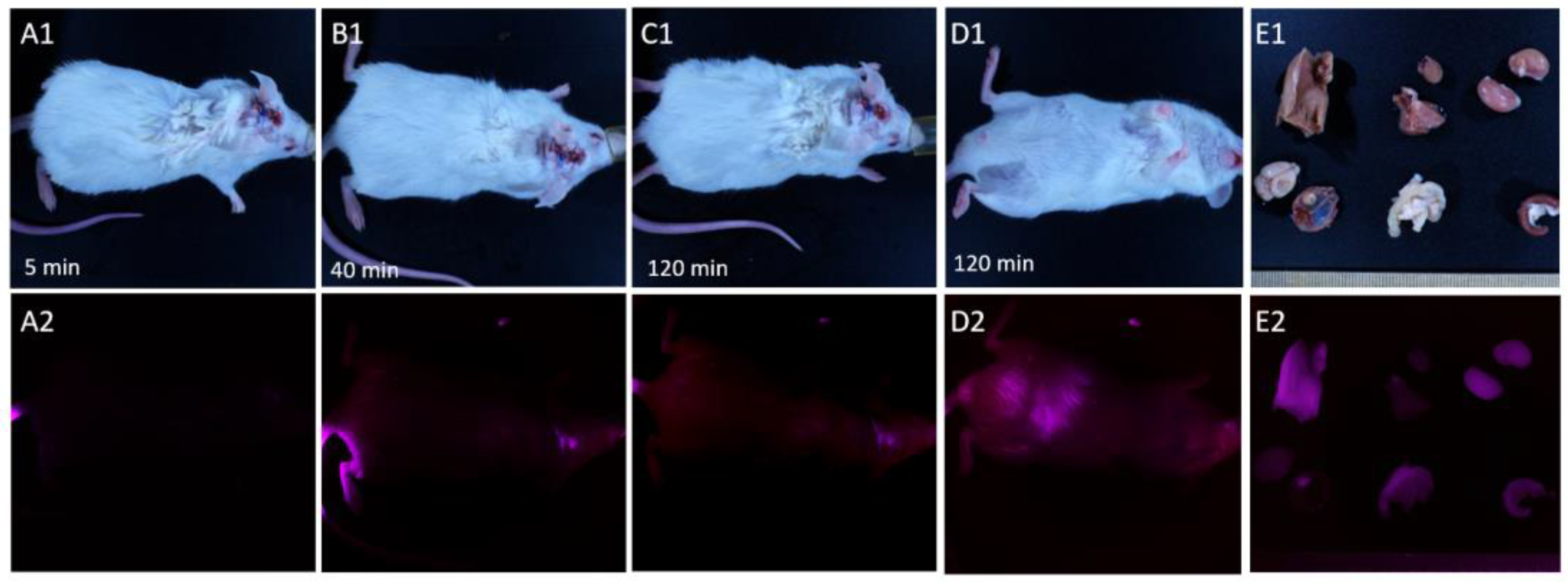

Mice with orthotopically xenotransplanted gliomas exhibited a similar distribution of this drug when administered intravenously (

Figure 5). Forty minutes after injection, IR-Glint could be visualized in the infrared spectra in the brain at the location where the tumor was transplanted. After 90 minutes, the tumor remained visible and became visible in the abdominal cavity (

Figure 5D2). It could be observed that IR-Glint accumulated in the liver, gallbladder, kidneys, and intestines (

Figure 5E2).

Figure 5.

Distribution of IR-Glint in mice after tail vein injection registered at Brightfield (1), IR fluorescence (2). Mice 5 minutes (A), 40 minutes (B), 90 minutes (C, D). Accumulation of IR-Glint in organs (E): 1 – brain, 2 – tumor inside the skull, 3 – kidneys, 4 – spleen, 5 – intestines, 6 – liver, 7 – lungs, and 8 – heart.

Figure 5.

Distribution of IR-Glint in mice after tail vein injection registered at Brightfield (1), IR fluorescence (2). Mice 5 minutes (A), 40 minutes (B), 90 minutes (C, D). Accumulation of IR-Glint in organs (E): 1 – brain, 2 – tumor inside the skull, 3 – kidneys, 4 – spleen, 5 – intestines, 6 – liver, 7 – lungs, and 8 – heart.

Figure 6.

Distribution of IR-Glint in mice after intracranial injection (subtutaneously on the place of trepanetion hole) registered at Brightfield (1), IR fluorescence (F). Mice 40 minutes (A) and 90 minutes (C). Accumulation of IR-Glint in brain (C) and dissected brain (D) and comparing with other organs (D): 1 – brain, 2 – tumor inside the skull, 3 – kidneys, 4 – spleen, 5 – intestines, 6 – liver, 7 – lungs, 8 – heart, and 9 – stomach.

Figure 6.

Distribution of IR-Glint in mice after intracranial injection (subtutaneously on the place of trepanetion hole) registered at Brightfield (1), IR fluorescence (F). Mice 40 minutes (A) and 90 minutes (C). Accumulation of IR-Glint in brain (C) and dissected brain (D) and comparing with other organs (D): 1 – brain, 2 – tumor inside the skull, 3 – kidneys, 4 – spleen, 5 – intestines, 6 – liver, 7 – lungs, 8 – heart, and 9 – stomach.

The experiments described in this study were conducted using a mice in vivo imaging system to evaluate the potential application of the same technique for visualization under a surgical microscope. We simulated the fluorescence-guided surgery procedure directly applying IR-Glint to the exposed brain, followed by two subsequent brain rinses after a 2-minute interval. After a 30-minute period following the manipulation, the mice were sacrificed, the brains and organs were fixed with formalin and futher examined using a surgical microscope equipped with an infrared module.

The mouse brain with ortotopicaly xenotransplanted glioblastoma, tumor inside the skull and organs did not show any background IR fluorescence without IR-Glint administration (

Figure S4).

Figure 7 presents brains and organs of mice subjected to the FGS modeling with surface applied aptamers (

Figure 7 A) and intravenous injection (

Figure 7 B). As seen in the figures, surface application of the drug is sufficient for the visualization under the surgical microscope with IR module. It allowed for the visualization of tumor sites (A2) with good contrasting. Additionally, in cross-section, it can be observed that the IR-Glint penetrated 3-4 mm into the brain within 3 minutes. It also metabolised in liver (

Figure 7 C2).

3.5. Toxicity testing of aptamers in mice.

The acute toxicity of IR-Glint was assessed by monitoring changes in various blood biochemical parameters, including total protein level, cholesterol level, bilirubin level, alanine aminotransferase activity, alkaline phosphatase activity, and alpha-amylase activity. These specific parameters were chosen as they provide insights into the functionality of crucial organs such as the pancreas, kidneys, and liver.

The total protein level serves as an indicator of protein metabolism within the body, reflecting the overall health of the liver and kidneys. By measuring cholesterol level, we can gain information about lipid metabolism and assess potential effects on cardiovascular health. Bilirubin, a bile pigment produced during the breakdown of heme-containing proteins like hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cytochrome, is useful in determining the extent of red blood cell destruction and impaired bilirubin excretion, such as in cases of hemolytic jaundice (

Figure S5).

Moreover, the activity of alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and alpha-amylase were monitored. Alanine aminotransferase is an enzyme primarily found in the liver, and changes in its activity may indicate liver damage or dysfunction. Alkaline phosphatase is an enzyme produced by the liver, bones, and other tissues, and its altered activity can signify liver or bone-related disorders. Alpha-amylase, on the other hand, is a digestive enzyme mainly secreted by the pancreas and salivary glands, with smaller amounts present in other tissues. Changes in alpha-amylase activity can provide insights into poisoning, pancreatic and salivary gland issues, as well as renal insufficiency. By evaluating these blood biochemical parameters, we can assess the potential toxicity of IR-Glint and its impact on various vital organs and metabolic processes (

Figure S5).

Alanine aminotransferase is a cytosolic enzyme found in hepatocytes, and an increase in its activity indicates liver cell damage. Alkaline phosphatase is an enzyme present in almost all tissues of the body, with predominant localization in the liver, bones, and placenta. Total alkaline phosphatase activity increases when liver tissue, bone, or kidney damage occurs. Cholesterol is an important metabolite synthesized in the liver and is involved in the production of hormones, bile acids, and vitamin D. It also plays a role in regulating cell membrane permeability. The concentration of cholesterol reflects the liver's condition and impacts a wide range of metabolic pathways (

Figure S5). Studies have demonstrated that all investigated blood serum biochemical parameters in mice, both in the control and experimental groups, were within the normal range (

Figure S5) [

21,

22].

Therefore, it has been shown that IR-Glint does not exert acute toxic effects on the mouse organism and can simplify the tumor resection procedure for the surgeon.

3.6. In vivo visualization of human glioblastoma xenotransplantation and FGS modeling in a rabbit.

The study aimed to verify the potential use of tissue-specific aptamers labeled with an infrared dye as an intraoperative dye in a model of human glioma developed in rabbits. For this purpose, the rabbits were first subjected to drug-induced immunosuppression and then primary cultures of human glioma were transplanted into their brains through intracranial windows (

Figure 8 A1, A2).

To monitor the development of orthotopically xenotransplanted human glioma in the rabbits' brains, PET/CT imaging with

11C-methionine was used (

Figure 8 A3). The accumulation of

11C-methionine was observed in the area of the trepanation openings in the rabbit brain, specifically at both sites of the transplanted glioma (

Figure 8 A3).

Furthermore, the brain tissue, unaffected by glioblastoma, and the region of the brain with the growing tumor were stained with IR-Glint and fixed in formalin for analysis using a surgical fluorescent microscope (

Figure 8 B). The analysis revealed infrared fluorescence of the rabbit glioblastoma under the surgical fluorescent microscope. On the other hand, the unstained brain tissue and healthy brain tissue stained with IR-Glint did not emit fluorescence in this wavelength range (

Figure 8 D). However, the brain tissue with glioma stained with aptamers exhibited stable fluorescence in the infrared region of the spectrum.

To confirm the presence of glial tumor formation in the rabbit's brains and on the skulls, H&E staining was performed and the results were validated (

Figure 8 C).

Overall, these findings confirm the potential utility of tissue-specific aptamers labeled with an infrared dye as an intraoperative dye for detecting and visualizing human glioma in a rabbit model. This technique could have significant implications for improving surgical precision and tumor removal in glioma patients.

4. Discussion

Infrared-labeled DNA aptamers, which are molecular recognition elements, were used to visualize glial brain tumors in mice and rabbit models. These aptamers were previously selected by the cell-SELEX procedure to bind specifically to glial tumor tissue, making them highly sensitive and specific. To increase aptamer sensitivity and reduce costs, the aptamers were optimized and truncated using molecular dynamics and quantum chemical modeling.

Here we propose a strategy for fluorescence-guided surgery with the infrared-labeled aptamer pool, IR-Glint. This formulation is a good alternative for the specific visualization of malignant brain tissues, which makes the surgeon more confident during tumor resection. The infrared-labeled aptamer IR-Glint has several advantages that make it attractive to neurosurgeons. The high specificity of IR-Glint to glial tumor tissues and the absence of background fluorescence allows for a high-contrast and bright image, distinguishing tumor tissue from the healthy brain. The infrared label can be visible under tissue thickness up to a centimeter. The surface application of IR-Glint is very convenient, less toxic for the organism, and allows for a significant reduction in dosage.

However, this strategy has several limitations, such as the need to wash the operative field after sparing IR-Glint. Mice model experiments have demonstrated that even during surface application, the Cy7.5 labeled aptamers are absorbed into the blood and disperse throughout the body, concentrating in the liver, kidneys, intestines, and spleen. Preclinical animal studies have demonstrated the absence of toxic effects; however, only clinical trials can convincingly prove the safety and benefits of using IR-Glint for fluorescent-guided surgery.

Another challenge in using aptamers is that they are quickly eliminated from the bloodstream due to the action of nucleases and their small size, leading to their filtration by the kidneys. Additionally, it is not completely understood how aptamers will interact with their targets in complex, multicellular environments in humans. Animal models have demonstrated that fluorescently labeled aptamers could locate their targets in vivo and visualize individual tumor cells. It should be noted that infrared labels may have side effects. Additional research and clinical trials are required to confirm the safety and effectiveness of this approach.

5. Conclusions

Our results confirm the potential use of IR-Glint, for infrared intraoperative visualization of glioblastoma. Brain application of the aptamer-based formulation allows for noticeable visualization of the tumor, which can significantly facilitate the surgeon's task during the brain tumor resection. Surface application reduces the dosage of the formulation and minimizes possible negative toxic effects on the patient. Nevertheless, overall, the results of this study confirm the potential of aptamers with infrared labels for intraoperative visualization of glioblastoma, opening up new prospects in the field of neurosurgery and improving the outcomes of surgical treatment for this tumor disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S.M., M.V.B., A.A.N., A.S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.Z., I.A.Shch., P.V.A., A.A.K.; writing—review and editing A.S.K., T.N.Z., F.N.T.; methodology, G.S.Z., K.A.L., D.V.V., N.G.Ch., V.I.B., A.V.K., P.G.Shn., P.A.Sh.; performing experiments, visualization, data curation, G.S.Z., I.A.Shch., P.V.A., A.A.K., V.A.S, A.K.G., I.I.V., D.S.G., N.A.L., E.D.N., O.S.K., A.S.K., Y.E.G., V.D.F., K.V.B., A.K.K., I.N.L., V.A.Kh., E.V.S., D.A.K., A.A.M., N.A.T., A.A.K.; supervision medical part A.A.N., R.A.Z., P.A.Sh. N.G.Ch.; supervision biological experiments, G.S.Z., A.S.K.; supervision molecular modeling F.N.T., project administration V.S.M., A.S.K.; all authors provided intellectual input, and edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Molecular modeling, drug formulation, mice and tissue experiments were funded by Skolkovo grant no. MG 30/22, starting from 5.12.2022 (V.S M.). The development of the glioma tumor model on immunosuppressed rabbits and mice was supported by the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation project 123031000006-4 (A.S.K.). Fluorescence imaging on mice was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation project FWES-2022-0005. (A.S.K.). PET/CT visualization was funded by the Federal Medical Biological Agency, project 122041800132-2. (Ch.N.G.).

Acknowledgments

Technical and instrumental support was provided by the Krasnoyarsk Inter-District Ambulance Hospital, named after N.S. Karpovich, the Shared Core Facilities of Molecular and Cell Technologies and Central Scientific-Research Laboratory at Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, the Krasnoyarsk Regional Center for Collective Use at the Federal Research Center "KSC SB RAS," and the Federal Siberian Research Clinical Center of the Federal Medical Biological Agency. Tomsk Regional Core Shared Research Facilities Center of the National Research Tomsk State University provided an access to LSM 780 NLO Confocal microscope. The Center was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, grant no. 075-15-2021-693 (no. 13.RFC.21.0012). The authors express their gratitude to JCSS Joint Super Computer Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences for providing supercomputers for computer simulations. The authors extend their appreciation to Technoinfo company for the generous provision of the “Fluor i In Vivo” used for animal in vivo fluorescence imaging.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mahajan, S.; Suri, V.; Sahu, S.; Sharma, M.C.; Sarkar, C. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System 5th Edition (WHO CNS5): What’s New? Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2022, 65, S5–S13.

- Zhuravleva, M. A.; Shershever, A. S.; Bencion D. L. Ct perfusion Imaging in Dynamic Observation of Brain Gliomas Complex and Combined Treatment Results. Radiation diagnosis and therapy 2012, 2, 58-64.

- Teng, C.W.; Huang, V.; Arguelles, G.R.; Zhou, C.; Cho, S.S.; Harmsen, S.; Lee, J.Y.K. Applications of Indocyanine Green in Brain Tumor Surgery: Review of Clinical Evidence and Emerging Technologies. Neurosurgical Focus 2021, 50, E4. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, F.; Song, W.; Han, D.; Wen, W.; Qin, W. Quicker, Deeper and Stronger Imaging: A Review of Tumor-Targeted, near-Infrared Fluorescent Dyes for Fluorescence Guided Surgery in the Preclinical and Clinical Stages. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2020, 152, 123–143. [CrossRef]

- Kichkailo, A.S.; Narodov, A.A.; Komarova, M.A.; Zamay, T.N.; Zamay, G.S.; Kolovskaya, O.S.; Erakhtin, E.E.; Glazyrin, Y.E.; Veprintsev, D.V.; Moryachkov, R.V.; et al. Development of DNA Aptamers for Visualization of Glial Brain Tumors and Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 267–288. [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, J.M.; Sánchez-Gómez, P.; Vaz Salgado, M.Á.; Gargini, R.; Balañá, C. Dacomitinib: An Investigational Drug for the Treatment of Glioblastoma. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 2018, 27, 823–829. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Miller, D.M.; Lowe, M.; Rowe, C.; Wood, D.; Soyer, H.P.; Byrnes-Blake, K.; Parrish-Novak, J.; Ishak, L.; Olson, J.M.; et al. A First-in-Human Study of BLZ-100 (Tozuleristide) Demonstrates Tolerability and Safety in Skin Cancer Patients. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 2021, 23, 100830. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.J.; Oliveira, C.; Granja, P.L.; Sarmento, B. Monoclonal Antibodies: Technologies for Early Discovery and Engineering. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2018, 38, 394–408. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, J.; Khawli, L.A.; Hornick, J.L.; Epstein, A.L. Improving Monoclonal Antibody Pharmacokinetics via Chemical Modification. Q J Nucl Med 1998, 42, 242–249.

- Constantinou, A.; Chen, C.; Deonarain, M.P. Modulating the Pharmacokinetics of Therapeutic Antibodies. Biotechnol Lett 2010, 32, 609–622. [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Castanares, M.; Mukherjee, A.; Lupold, S.E. Nucleic Acid Aptamers: Clinical Applications and Promising New Horizons. CMC 2011, 18, 4206–4214. [CrossRef]

- Zuker, M. Mfold Web Server for Nucleic Acid Folding and Hybridization Prediction. Nucleic Acids Research 2003, 31, 3406–3415. [CrossRef]

- Boniecki, M.J.; Lach, G.; Dawson, W.K.; Tomala, K.; Lukasz, P.; Soltysinski, T.; Rother, K.M.; Bujnicki, J.M. SimRNA: A Coarse-Grained Method for RNA Folding Simulations and 3D Structure Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, e63–e63. [CrossRef]

- Jeddi, I.; Saiz, L. Three-Dimensional Modeling of Single Stranded DNA Hairpins for Aptamer-Based Biosensors. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 1178. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. Ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from Ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1983, 79, 926–935. [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical Sampling through Velocity Rescaling. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2007, 126, 014101. [CrossRef]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic Transitions in Single Crystals: A New Molecular Dynamics Method. Journal of Applied Physics 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [CrossRef]

- Heyer, L.J.; Kruglyak, S.; Yooseph, S. Exploring Expression Data: Identification and Analysis of Coexpressed Genes. Genome Res. 1999, 9, 1106–1115. [CrossRef]

- Jivrajani, M.; Shaikh, M.V.; Shrivastava, N.; Nivsarkar, M. An Improved and Versatile Immunosuppression Protocol for the Development of Tumor Xenograft in Mice. Anticancer Res 2014, 34, 7177–7183.

- Miroshnikov, M.V.; Makarova, M.N. Variability of Blood Biochemical Parameters and Establishment of Reference Intervals in Preclinical Studies. Laboratory animals for scientific research 2021, 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Krasnikova, E.S.; Karmeeva, Y.S.; Aledo, M.M.; Krasnikov, A.V.; Kalganov, S.A. Hemato-Biochemical Status of Laboratory Mice with a GM Corn Based Diet. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 315, 042005. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Secondary and tertiary structure of Gli-233 (A), Gli-233nt (B), Gli- 233_ 2 (C), Gli-55 (D), Gli-55_3L (E), and Gli -55_2L (F) aptamers.

Figure 1.

Secondary and tertiary structure of Gli-233 (A), Gli-233nt (B), Gli- 233_ 2 (C), Gli-55 (D), Gli-55_3L (E), and Gli -55_2L (F) aptamers.

Figure 2.

Binding analysis of aptamers Gli-233 and Gli-55 and its modified versions of sequences. (A) Histogram of aptamers binding with glioblastoma and breast cancer (BC) cultured cells and cells isolated from healthy mouse brain (MB). (B) Flow cytometry data of glioblastoma and breast cancer cells incubated with FAM-labeled Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L. (C) Histogram of aptamers binding with astrocytes and neurospheres in glioblastoma cultures. Experiments were performed in triplicates.

Figure 2.

Binding analysis of aptamers Gli-233 and Gli-55 and its modified versions of sequences. (A) Histogram of aptamers binding with glioblastoma and breast cancer (BC) cultured cells and cells isolated from healthy mouse brain (MB). (B) Flow cytometry data of glioblastoma and breast cancer cells incubated with FAM-labeled Gli-233nt and Gli-55_3L. (C) Histogram of aptamers binding with astrocytes and neurospheres in glioblastoma cultures. Experiments were performed in triplicates.

Figure 3.

Specific staining of glial tumor cells in surgically resected glioblastoma tissues. In panels, A1 and B1, FAM-Glint was used to stain glioblastoma multiform multiform tissues (A) and sarcomatoid region (B). Panel C shows the staining obtained with a non-specific oligonucleotide (C1), which does not bind to glial tumors. Adjacent sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were used for comparison in panels A2, B2 and C2.

Figure 3.

Specific staining of glial tumor cells in surgically resected glioblastoma tissues. In panels, A1 and B1, FAM-Glint was used to stain glioblastoma multiform multiform tissues (A) and sarcomatoid region (B). Panel C shows the staining obtained with a non-specific oligonucleotide (C1), which does not bind to glial tumors. Adjacent sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were used for comparison in panels A2, B2 and C2.

Figure 4.

Glial tumor tissues were incubated with a pool of IR-Glint aptamers at concentrations of 0 µM (A), 1 µM (B), 2 µM (C), 3 µM (D), 5 µM (E), and 8 µM (F), using the IR module of the Zeiss Kinevo 900 surgical microscope. The tissues were placed in 3 cm Peri dishes.

Figure 4.

Glial tumor tissues were incubated with a pool of IR-Glint aptamers at concentrations of 0 µM (A), 1 µM (B), 2 µM (C), 3 µM (D), 5 µM (E), and 8 µM (F), using the IR module of the Zeiss Kinevo 900 surgical microscope. The tissues were placed in 3 cm Peri dishes.

Figure 7.

Light (A1, B1, C1) and IR fluorescent (A2) microscopy of mice brain (A, arrow 2), a tumor on the skull (A, arrow 1), brain crosssection (B), and organs (C) with orthotopically xenotransplanted glioblastoma after the surface intracranial application of IR-Glint. H&E staining confirmed glial tumor formation in mice brains (A1.1-A1.4) and inside the skull (B1.1, B1.2).

Figure 7.

Light (A1, B1, C1) and IR fluorescent (A2) microscopy of mice brain (A, arrow 2), a tumor on the skull (A, arrow 1), brain crosssection (B), and organs (C) with orthotopically xenotransplanted glioblastoma after the surface intracranial application of IR-Glint. H&E staining confirmed glial tumor formation in mice brains (A1.1-A1.4) and inside the skull (B1.1, B1.2).

Figure 8.

Justification of the applicability of IR-Glint for the fluorescence-guided surgery of glial tumor demonstrated on orthotopically xenotransplanted glioblastoma on rabbit’s brain. PET/CT imaging with 11C-methionine. Primary glial tumor culture (A1) transplanted into rabbits brains through intracranial windows (A2). Light (B1) and IR fluorescent (B2-B3) microscopy of rabbit’s glial tumors after the surface intracranial application of IR-Glint. H&E staining confirmed glial tumor formation in rabbits brains (C2, C2).

Figure 8.

Justification of the applicability of IR-Glint for the fluorescence-guided surgery of glial tumor demonstrated on orthotopically xenotransplanted glioblastoma on rabbit’s brain. PET/CT imaging with 11C-methionine. Primary glial tumor culture (A1) transplanted into rabbits brains through intracranial windows (A2). Light (B1) and IR fluorescent (B2-B3) microscopy of rabbit’s glial tumors after the surface intracranial application of IR-Glint. H&E staining confirmed glial tumor formation in rabbits brains (C2, C2).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).